User login

Flu shots and persuasion

Compliant patients are all alike; every noncompliant patient is obstinate in his or her own way. Because of this, persuading patients to make good choices is rarely easy and never universal.

At Kaiser Permanente, we have begun in earnest providing flu shots. Every department participates (even dermatology) with a goal of vaccinating every eligible patient. Most patients want their shot. When patients decline, it’s game on. A rare few decline for justifiable reasons such as an allergy. Most say “no” for flawed reasons: “I never get the flu,” “The shot always gives me the flu,” and “I don’t believe in vaccines,” are common ones.

Fortunately, we can help them. Here are techniques I learned while working on my MBA that I’ve found useful in persuading patients to make better choices:

- The “everyone is doing it” technique. At KP, we’ve put up boards with the iconic goal thermometer showing how many flu shots we need to reach our objective. When patients see we’ve given over 1,000 shots in dermatology in just 2 weeks, this technique helps convince them. Patients prefer to be like others rather than to stand out, particularly when there is uncertainty.

- The “this is who you are technique.” Patients hate to be seen as inconsistent. In fact, we are all more likely to make a choice seen as consistent with who we are rather than change our mind, even if doing so is a better choice. Highlight how they have previously shown good decision making and healthy behaviors and point out how getting vaccinated is consonant with who they are. For example: “Being a vegan, you are clearly someone who takes care of her health. Getting the vaccine is similar to choosing to eat plants. It’s what healthy people like you do.”

- The “well, that’s not like you” technique. Here, you point out how their choice is inconsistent with their previous choices. You might say, “Why would you get the hepatitis A vaccine last week and not the flu shot today?” Like the previous technique, this creates cognitive dissonance. You might soften the approach by saying, “You might have thought this,” or “I’m sure you didn’t realize.”

- The emotional decision approach. Making the risk seem real and imminent can combat future discounting. One example might be: “We have had several people hospitalized and one death from the flu in San Diego already.” Use stories and descriptive language to make the risk salient.

- The use your authority approach. The long coat does matter. A more modern version of the paternalistic physician is referred to as “asymmetric” or “light paternalism,” and we should recognize that it might be used to save a life. One example is: “I advise you to get the flu shot because I care about you, and I’m worried you might end up in the hospital or worse if you don’t get it.” There’s a reason why tobacco companies once used doctors in white coats to sell cigarettes – we can be quite persuasive.

“A great deal of literature has been distributed, casting discredit upon the value of vaccination ... I do not see how any one ... who is familiar with the history of the subject, and who has any capacity left for clear judgment, can doubt its value.” – William Osler

Dr. Benabio is director of health care transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Compliant patients are all alike; every noncompliant patient is obstinate in his or her own way. Because of this, persuading patients to make good choices is rarely easy and never universal.

At Kaiser Permanente, we have begun in earnest providing flu shots. Every department participates (even dermatology) with a goal of vaccinating every eligible patient. Most patients want their shot. When patients decline, it’s game on. A rare few decline for justifiable reasons such as an allergy. Most say “no” for flawed reasons: “I never get the flu,” “The shot always gives me the flu,” and “I don’t believe in vaccines,” are common ones.

Fortunately, we can help them. Here are techniques I learned while working on my MBA that I’ve found useful in persuading patients to make better choices:

- The “everyone is doing it” technique. At KP, we’ve put up boards with the iconic goal thermometer showing how many flu shots we need to reach our objective. When patients see we’ve given over 1,000 shots in dermatology in just 2 weeks, this technique helps convince them. Patients prefer to be like others rather than to stand out, particularly when there is uncertainty.

- The “this is who you are technique.” Patients hate to be seen as inconsistent. In fact, we are all more likely to make a choice seen as consistent with who we are rather than change our mind, even if doing so is a better choice. Highlight how they have previously shown good decision making and healthy behaviors and point out how getting vaccinated is consonant with who they are. For example: “Being a vegan, you are clearly someone who takes care of her health. Getting the vaccine is similar to choosing to eat plants. It’s what healthy people like you do.”

- The “well, that’s not like you” technique. Here, you point out how their choice is inconsistent with their previous choices. You might say, “Why would you get the hepatitis A vaccine last week and not the flu shot today?” Like the previous technique, this creates cognitive dissonance. You might soften the approach by saying, “You might have thought this,” or “I’m sure you didn’t realize.”

- The emotional decision approach. Making the risk seem real and imminent can combat future discounting. One example might be: “We have had several people hospitalized and one death from the flu in San Diego already.” Use stories and descriptive language to make the risk salient.

- The use your authority approach. The long coat does matter. A more modern version of the paternalistic physician is referred to as “asymmetric” or “light paternalism,” and we should recognize that it might be used to save a life. One example is: “I advise you to get the flu shot because I care about you, and I’m worried you might end up in the hospital or worse if you don’t get it.” There’s a reason why tobacco companies once used doctors in white coats to sell cigarettes – we can be quite persuasive.

“A great deal of literature has been distributed, casting discredit upon the value of vaccination ... I do not see how any one ... who is familiar with the history of the subject, and who has any capacity left for clear judgment, can doubt its value.” – William Osler

Dr. Benabio is director of health care transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

Compliant patients are all alike; every noncompliant patient is obstinate in his or her own way. Because of this, persuading patients to make good choices is rarely easy and never universal.

At Kaiser Permanente, we have begun in earnest providing flu shots. Every department participates (even dermatology) with a goal of vaccinating every eligible patient. Most patients want their shot. When patients decline, it’s game on. A rare few decline for justifiable reasons such as an allergy. Most say “no” for flawed reasons: “I never get the flu,” “The shot always gives me the flu,” and “I don’t believe in vaccines,” are common ones.

Fortunately, we can help them. Here are techniques I learned while working on my MBA that I’ve found useful in persuading patients to make better choices:

- The “everyone is doing it” technique. At KP, we’ve put up boards with the iconic goal thermometer showing how many flu shots we need to reach our objective. When patients see we’ve given over 1,000 shots in dermatology in just 2 weeks, this technique helps convince them. Patients prefer to be like others rather than to stand out, particularly when there is uncertainty.

- The “this is who you are technique.” Patients hate to be seen as inconsistent. In fact, we are all more likely to make a choice seen as consistent with who we are rather than change our mind, even if doing so is a better choice. Highlight how they have previously shown good decision making and healthy behaviors and point out how getting vaccinated is consonant with who they are. For example: “Being a vegan, you are clearly someone who takes care of her health. Getting the vaccine is similar to choosing to eat plants. It’s what healthy people like you do.”

- The “well, that’s not like you” technique. Here, you point out how their choice is inconsistent with their previous choices. You might say, “Why would you get the hepatitis A vaccine last week and not the flu shot today?” Like the previous technique, this creates cognitive dissonance. You might soften the approach by saying, “You might have thought this,” or “I’m sure you didn’t realize.”

- The emotional decision approach. Making the risk seem real and imminent can combat future discounting. One example might be: “We have had several people hospitalized and one death from the flu in San Diego already.” Use stories and descriptive language to make the risk salient.

- The use your authority approach. The long coat does matter. A more modern version of the paternalistic physician is referred to as “asymmetric” or “light paternalism,” and we should recognize that it might be used to save a life. One example is: “I advise you to get the flu shot because I care about you, and I’m worried you might end up in the hospital or worse if you don’t get it.” There’s a reason why tobacco companies once used doctors in white coats to sell cigarettes – we can be quite persuasive.

“A great deal of literature has been distributed, casting discredit upon the value of vaccination ... I do not see how any one ... who is familiar with the history of the subject, and who has any capacity left for clear judgment, can doubt its value.” – William Osler

Dr. Benabio is director of health care transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@frontlinemedcom.com.

International parental attitudes of HPV vaccination have similarities, differences

A study comparing parental attitudes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in three countries indicates both low and high HPV knowledge may be associated with lower rates of vaccination, and parents’ country and gender also impact the likelihood of adolescents being immunized, reported Brooke Nickel, of the University of Sydney, and associates.

Of 179 parents with a daughter aged 9-17 years from the United States, United Kingdom, or Australia who took part in an online HPV vaccine opinion survey in 2011, 59% reported that their daughters had received HPV vaccination – 43% in the United States cohort, 63% in the United Kingdom cohort, and 76% in the Australian cohort.

(P less than .001). Parents who had either low knowledge scores or high knowledge scores were less likely to have their daughters vaccinated; U.S. parents and men across all countries also were less likely to vaccinate their daughters.

Among the parents whose daughters did not receive the HPV vaccine, worry about the vaccine’s side effects was significantly more prevalent among the U.S. parents (61%) than among parents in the United Kingdom (36%) or among parents in Australia (15%) (P less than .05). U.S. parents who did not have their daughters get the HPV vaccine also were more likely to agree that getting all three HPV vaccine doses would be a “big hassle” (21%), compared with the United Kingdom cohort (0%) and the Australian cohort (8%) (P less than .05).

Parents from the United States also were significantly more likely to agree that the HPV vaccine was too new so they would want to wait before deciding to get it for their daughters (45%), compared with the parents in the United Kingdom (23%) and those in Australia (8%) (P less than .05).

“This finding was unexpected, given that advertising about HPV contributed to an increased awareness of HPV in the United States at the time of data collection. It is important to note, however, that this survey was conducted in 2011, and therefore attitudes of U.S. parents now may differ,” the researchers wrote.

Nonetheless, parents of unvaccinated daughters with higher knowledge scores overall were more likely to believe that they would want to be on the safe side and vaccinate their daughters at some time (74%) compared with parents who had lower knowledge scores (27%) (P less than .001).

“Parents from the United States with unvaccinated daughters more often believed that getting all three doses of the HPV vaccine would be a significant obstacle, not surprisingly as the HPV vaccine distribution in the United States is predominantly available through physicians’ clinics and medical centers, whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia, free school-based and catch-up programs are offered,” the investigators said.

Read more in Preventive Medicine Reports (2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005).

A study comparing parental attitudes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in three countries indicates both low and high HPV knowledge may be associated with lower rates of vaccination, and parents’ country and gender also impact the likelihood of adolescents being immunized, reported Brooke Nickel, of the University of Sydney, and associates.

Of 179 parents with a daughter aged 9-17 years from the United States, United Kingdom, or Australia who took part in an online HPV vaccine opinion survey in 2011, 59% reported that their daughters had received HPV vaccination – 43% in the United States cohort, 63% in the United Kingdom cohort, and 76% in the Australian cohort.

(P less than .001). Parents who had either low knowledge scores or high knowledge scores were less likely to have their daughters vaccinated; U.S. parents and men across all countries also were less likely to vaccinate their daughters.

Among the parents whose daughters did not receive the HPV vaccine, worry about the vaccine’s side effects was significantly more prevalent among the U.S. parents (61%) than among parents in the United Kingdom (36%) or among parents in Australia (15%) (P less than .05). U.S. parents who did not have their daughters get the HPV vaccine also were more likely to agree that getting all three HPV vaccine doses would be a “big hassle” (21%), compared with the United Kingdom cohort (0%) and the Australian cohort (8%) (P less than .05).

Parents from the United States also were significantly more likely to agree that the HPV vaccine was too new so they would want to wait before deciding to get it for their daughters (45%), compared with the parents in the United Kingdom (23%) and those in Australia (8%) (P less than .05).

“This finding was unexpected, given that advertising about HPV contributed to an increased awareness of HPV in the United States at the time of data collection. It is important to note, however, that this survey was conducted in 2011, and therefore attitudes of U.S. parents now may differ,” the researchers wrote.

Nonetheless, parents of unvaccinated daughters with higher knowledge scores overall were more likely to believe that they would want to be on the safe side and vaccinate their daughters at some time (74%) compared with parents who had lower knowledge scores (27%) (P less than .001).

“Parents from the United States with unvaccinated daughters more often believed that getting all three doses of the HPV vaccine would be a significant obstacle, not surprisingly as the HPV vaccine distribution in the United States is predominantly available through physicians’ clinics and medical centers, whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia, free school-based and catch-up programs are offered,” the investigators said.

Read more in Preventive Medicine Reports (2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005).

A study comparing parental attitudes of the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in three countries indicates both low and high HPV knowledge may be associated with lower rates of vaccination, and parents’ country and gender also impact the likelihood of adolescents being immunized, reported Brooke Nickel, of the University of Sydney, and associates.

Of 179 parents with a daughter aged 9-17 years from the United States, United Kingdom, or Australia who took part in an online HPV vaccine opinion survey in 2011, 59% reported that their daughters had received HPV vaccination – 43% in the United States cohort, 63% in the United Kingdom cohort, and 76% in the Australian cohort.

(P less than .001). Parents who had either low knowledge scores or high knowledge scores were less likely to have their daughters vaccinated; U.S. parents and men across all countries also were less likely to vaccinate their daughters.

Among the parents whose daughters did not receive the HPV vaccine, worry about the vaccine’s side effects was significantly more prevalent among the U.S. parents (61%) than among parents in the United Kingdom (36%) or among parents in Australia (15%) (P less than .05). U.S. parents who did not have their daughters get the HPV vaccine also were more likely to agree that getting all three HPV vaccine doses would be a “big hassle” (21%), compared with the United Kingdom cohort (0%) and the Australian cohort (8%) (P less than .05).

Parents from the United States also were significantly more likely to agree that the HPV vaccine was too new so they would want to wait before deciding to get it for their daughters (45%), compared with the parents in the United Kingdom (23%) and those in Australia (8%) (P less than .05).

“This finding was unexpected, given that advertising about HPV contributed to an increased awareness of HPV in the United States at the time of data collection. It is important to note, however, that this survey was conducted in 2011, and therefore attitudes of U.S. parents now may differ,” the researchers wrote.

Nonetheless, parents of unvaccinated daughters with higher knowledge scores overall were more likely to believe that they would want to be on the safe side and vaccinate their daughters at some time (74%) compared with parents who had lower knowledge scores (27%) (P less than .001).

“Parents from the United States with unvaccinated daughters more often believed that getting all three doses of the HPV vaccine would be a significant obstacle, not surprisingly as the HPV vaccine distribution in the United States is predominantly available through physicians’ clinics and medical centers, whereas in the United Kingdom and Australia, free school-based and catch-up programs are offered,” the investigators said.

Read more in Preventive Medicine Reports (2017 Oct 10. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2017.10.005).

FROM PREVENTIVE MEDICINE REPORTS

Missed opportunities abound to give HPV vaccine to adolescent girls

, in a study of more than 14,000 fully insured teen girls, reported Claudia M. Espinosa, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Louisville (Ky.), and her associates.

In a study of 14,588 girls in a fully insured commercial or Medicaid plan who turned 11 years old between Jan. 1, 2010, and Sept. 31, 2015, it was documented whether or not the girls received an HPV vaccine when they were given another adolescent vaccine – one or more doses of the Tdap vaccine and/or one or more doses of the 4-valent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY vaccine).

Girls who started HPV vaccination were more likely than those who didn’t to receive the MenACWY (86% vs. 64%, respectively; P less than .0001) and Tdap (86% vs. 73%, respectively; P less than .0001) vaccines.

“A missed opportunity was defined as the absence of an HPV vaccine dose administered during any visit with a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine claim, any well-adolescent visit, or any encounter with a primary care provider, regardless of visit type,” the investigators said.

Of 10,987 visits when a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine dose was given, HPV vaccine was given at the same visit in only 37% of cases. An HPV vaccine was administered at only 26% of 12,621 of well-adolescent visits, and 42% of 14,195 other visits with primary care providers.

“The data also suggest that pediatricians and nonpediatricians alike are missing opportunities to administer the HPV vaccine when other adolescent vaccines are given,” Dr. Espinosa and her associates noted. “Future research should focus on communication strategies that might facilitate the conceptual ‘bundling’ of HPV vaccine with other adolescent vaccines in the provider’s office.”

Read more in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2017 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix067).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

, in a study of more than 14,000 fully insured teen girls, reported Claudia M. Espinosa, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Louisville (Ky.), and her associates.

In a study of 14,588 girls in a fully insured commercial or Medicaid plan who turned 11 years old between Jan. 1, 2010, and Sept. 31, 2015, it was documented whether or not the girls received an HPV vaccine when they were given another adolescent vaccine – one or more doses of the Tdap vaccine and/or one or more doses of the 4-valent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY vaccine).

Girls who started HPV vaccination were more likely than those who didn’t to receive the MenACWY (86% vs. 64%, respectively; P less than .0001) and Tdap (86% vs. 73%, respectively; P less than .0001) vaccines.

“A missed opportunity was defined as the absence of an HPV vaccine dose administered during any visit with a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine claim, any well-adolescent visit, or any encounter with a primary care provider, regardless of visit type,” the investigators said.

Of 10,987 visits when a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine dose was given, HPV vaccine was given at the same visit in only 37% of cases. An HPV vaccine was administered at only 26% of 12,621 of well-adolescent visits, and 42% of 14,195 other visits with primary care providers.

“The data also suggest that pediatricians and nonpediatricians alike are missing opportunities to administer the HPV vaccine when other adolescent vaccines are given,” Dr. Espinosa and her associates noted. “Future research should focus on communication strategies that might facilitate the conceptual ‘bundling’ of HPV vaccine with other adolescent vaccines in the provider’s office.”

Read more in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2017 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix067).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

, in a study of more than 14,000 fully insured teen girls, reported Claudia M. Espinosa, MD, of the division of pediatric infectious diseases, University of Louisville (Ky.), and her associates.

In a study of 14,588 girls in a fully insured commercial or Medicaid plan who turned 11 years old between Jan. 1, 2010, and Sept. 31, 2015, it was documented whether or not the girls received an HPV vaccine when they were given another adolescent vaccine – one or more doses of the Tdap vaccine and/or one or more doses of the 4-valent meningococcal conjugate vaccine (MenACWY vaccine).

Girls who started HPV vaccination were more likely than those who didn’t to receive the MenACWY (86% vs. 64%, respectively; P less than .0001) and Tdap (86% vs. 73%, respectively; P less than .0001) vaccines.

“A missed opportunity was defined as the absence of an HPV vaccine dose administered during any visit with a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine claim, any well-adolescent visit, or any encounter with a primary care provider, regardless of visit type,” the investigators said.

Of 10,987 visits when a Tdap or MenACWY vaccine dose was given, HPV vaccine was given at the same visit in only 37% of cases. An HPV vaccine was administered at only 26% of 12,621 of well-adolescent visits, and 42% of 14,195 other visits with primary care providers.

“The data also suggest that pediatricians and nonpediatricians alike are missing opportunities to administer the HPV vaccine when other adolescent vaccines are given,” Dr. Espinosa and her associates noted. “Future research should focus on communication strategies that might facilitate the conceptual ‘bundling’ of HPV vaccine with other adolescent vaccines in the provider’s office.”

Read more in the Journal of the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Society (2017 Sep 23. doi: 10.1093/jpids/pix067).

cnellist@frontlinemedcom.com

FROM THE JOURNAL OF THE PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES SOCIETY

Nearly 80% of health care personnel stepped up for flu shots

Nearly four out of five health care personnel in the United States received a flu vaccination during the 2016-2017 flu season, but a majority of those working in long-term care settings were not vaccinated, based on data from an Internet survey of more than 2,000 individuals that was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 78.6% of the survey’s respondents said they’d been vaccinated during the 2016-2017 season. Vaccination coverage for health care personnel overall has remained in the 77%-79% range in recent years, but that represents an increase from 64% in 2010-2011.

“As in previous seasons, the highest coverage was among HCP whose workplace had vaccination requirements,” noted Carla L. Black, PhD, of the CDC, and colleagues (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1009-15). The researchers reviewed data collected from an Internet panel survey of 2,438 health care personnel between March 28, 2017, and April 19, 2017.

Physicians boasted the highest vaccination coverage in 2016-2017 (96%), followed by pharmacists (94%), nurses (93%), nurse practitioners and physician assistants (92%), other clinical providers (80%), nonclinical health care providers (74%), and aides and assistants (69%).

Flu vaccination rates were highest among HCPs working in a hospital setting (92%); 94% of survey respondents in hospitals reported either having a vaccination requirement at work or being provided at least 1 day of on-site vaccination.

Vaccination rates were lowest among health care personnel in long-term care settings (68%), where only 26% reported a workplace vaccination requirement. However, vaccination rates in long-term care rose to 90% when employers required vaccination.

The report’s findings were limited by several factors, including the use of a volunteer sample, the reliance on self-reports, and the potential differences between Internet survey results and population-based estimates of flu vaccination.

However, “in the absence of vaccination requirements, the findings in this study support the recommendations found in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, which include active promotion of on-site vaccination at no cost or low cost to increase influenza vaccination coverage among HCPs,” the researchers said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Nearly four out of five health care personnel in the United States received a flu vaccination during the 2016-2017 flu season, but a majority of those working in long-term care settings were not vaccinated, based on data from an Internet survey of more than 2,000 individuals that was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 78.6% of the survey’s respondents said they’d been vaccinated during the 2016-2017 season. Vaccination coverage for health care personnel overall has remained in the 77%-79% range in recent years, but that represents an increase from 64% in 2010-2011.

“As in previous seasons, the highest coverage was among HCP whose workplace had vaccination requirements,” noted Carla L. Black, PhD, of the CDC, and colleagues (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1009-15). The researchers reviewed data collected from an Internet panel survey of 2,438 health care personnel between March 28, 2017, and April 19, 2017.

Physicians boasted the highest vaccination coverage in 2016-2017 (96%), followed by pharmacists (94%), nurses (93%), nurse practitioners and physician assistants (92%), other clinical providers (80%), nonclinical health care providers (74%), and aides and assistants (69%).

Flu vaccination rates were highest among HCPs working in a hospital setting (92%); 94% of survey respondents in hospitals reported either having a vaccination requirement at work or being provided at least 1 day of on-site vaccination.

Vaccination rates were lowest among health care personnel in long-term care settings (68%), where only 26% reported a workplace vaccination requirement. However, vaccination rates in long-term care rose to 90% when employers required vaccination.

The report’s findings were limited by several factors, including the use of a volunteer sample, the reliance on self-reports, and the potential differences between Internet survey results and population-based estimates of flu vaccination.

However, “in the absence of vaccination requirements, the findings in this study support the recommendations found in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, which include active promotion of on-site vaccination at no cost or low cost to increase influenza vaccination coverage among HCPs,” the researchers said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Nearly four out of five health care personnel in the United States received a flu vaccination during the 2016-2017 flu season, but a majority of those working in long-term care settings were not vaccinated, based on data from an Internet survey of more than 2,000 individuals that was conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

A total of 78.6% of the survey’s respondents said they’d been vaccinated during the 2016-2017 season. Vaccination coverage for health care personnel overall has remained in the 77%-79% range in recent years, but that represents an increase from 64% in 2010-2011.

“As in previous seasons, the highest coverage was among HCP whose workplace had vaccination requirements,” noted Carla L. Black, PhD, of the CDC, and colleagues (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1009-15). The researchers reviewed data collected from an Internet panel survey of 2,438 health care personnel between March 28, 2017, and April 19, 2017.

Physicians boasted the highest vaccination coverage in 2016-2017 (96%), followed by pharmacists (94%), nurses (93%), nurse practitioners and physician assistants (92%), other clinical providers (80%), nonclinical health care providers (74%), and aides and assistants (69%).

Flu vaccination rates were highest among HCPs working in a hospital setting (92%); 94% of survey respondents in hospitals reported either having a vaccination requirement at work or being provided at least 1 day of on-site vaccination.

Vaccination rates were lowest among health care personnel in long-term care settings (68%), where only 26% reported a workplace vaccination requirement. However, vaccination rates in long-term care rose to 90% when employers required vaccination.

The report’s findings were limited by several factors, including the use of a volunteer sample, the reliance on self-reports, and the potential differences between Internet survey results and population-based estimates of flu vaccination.

However, “in the absence of vaccination requirements, the findings in this study support the recommendations found in the Guide to Community Preventive Services, which include active promotion of on-site vaccination at no cost or low cost to increase influenza vaccination coverage among HCPs,” the researchers said.

The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

FROM MMWR

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Overall flu vaccination coverage among U.S. health care personnel was 78.6% in the 2016-2017 season

Data source: The data come from an Internet survey of 2,438 health care personnel.

Disclosures: The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose.

Tdap during pregnancy, or before, offers infants pertussis protection

during the early months of life, according to Tami H. Skoff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

In an analysis of 240 infants younger than 2 months with pertussis cough onset between 2011 and 2015 and 535 control infants, 57% of case mothers and 67% of control mothers had at least one valid Tdap dose; 13% of vaccinated case mothers and 14% of vaccinated control mothers had more than one valid dose of Tdap reported.

Of Tdap doses received during pregnancy in 22 cases and 117 controls, 77% were received during the third trimester, most during the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ recommended 27-36 weeks of gestation. Of the Tdap doses received before pregnancy in mothers of 24 cases and 67 controls, 25% of the case mothers and 67% of the control mothers received Tdap 2 or fewer years before pregnancy.

The effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy was 78%, and effectiveness during the first or second trimester was 64%. Effectiveness of Tdap given 2 or fewer years before pregnancy was 83%. This study was not powered to determine a difference if the vaccine was administered in the ACIP-recommended time period during the third trimester.

A reported 49% of U.S. pregnant women received Tdap during the 2015-2016 flu season, an increase of 22% from the 2013-2014 season, according to a CDC Internet panel survey.

“While maternal immunization during pregnancy will help bridge the gap until next-generation pertussis vaccines are licensed and available for use, this highly effective strategy will likely remain an integral component of pertussis prevention and control, even in the setting of new vaccines,” the investigators said.

Read more in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix724).

during the early months of life, according to Tami H. Skoff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

In an analysis of 240 infants younger than 2 months with pertussis cough onset between 2011 and 2015 and 535 control infants, 57% of case mothers and 67% of control mothers had at least one valid Tdap dose; 13% of vaccinated case mothers and 14% of vaccinated control mothers had more than one valid dose of Tdap reported.

Of Tdap doses received during pregnancy in 22 cases and 117 controls, 77% were received during the third trimester, most during the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ recommended 27-36 weeks of gestation. Of the Tdap doses received before pregnancy in mothers of 24 cases and 67 controls, 25% of the case mothers and 67% of the control mothers received Tdap 2 or fewer years before pregnancy.

The effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy was 78%, and effectiveness during the first or second trimester was 64%. Effectiveness of Tdap given 2 or fewer years before pregnancy was 83%. This study was not powered to determine a difference if the vaccine was administered in the ACIP-recommended time period during the third trimester.

A reported 49% of U.S. pregnant women received Tdap during the 2015-2016 flu season, an increase of 22% from the 2013-2014 season, according to a CDC Internet panel survey.

“While maternal immunization during pregnancy will help bridge the gap until next-generation pertussis vaccines are licensed and available for use, this highly effective strategy will likely remain an integral component of pertussis prevention and control, even in the setting of new vaccines,” the investigators said.

Read more in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix724).

during the early months of life, according to Tami H. Skoff of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates.

In an analysis of 240 infants younger than 2 months with pertussis cough onset between 2011 and 2015 and 535 control infants, 57% of case mothers and 67% of control mothers had at least one valid Tdap dose; 13% of vaccinated case mothers and 14% of vaccinated control mothers had more than one valid dose of Tdap reported.

Of Tdap doses received during pregnancy in 22 cases and 117 controls, 77% were received during the third trimester, most during the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices’ recommended 27-36 weeks of gestation. Of the Tdap doses received before pregnancy in mothers of 24 cases and 67 controls, 25% of the case mothers and 67% of the control mothers received Tdap 2 or fewer years before pregnancy.

The effectiveness of Tdap vaccination during the third trimester of pregnancy was 78%, and effectiveness during the first or second trimester was 64%. Effectiveness of Tdap given 2 or fewer years before pregnancy was 83%. This study was not powered to determine a difference if the vaccine was administered in the ACIP-recommended time period during the third trimester.

A reported 49% of U.S. pregnant women received Tdap during the 2015-2016 flu season, an increase of 22% from the 2013-2014 season, according to a CDC Internet panel survey.

“While maternal immunization during pregnancy will help bridge the gap until next-generation pertussis vaccines are licensed and available for use, this highly effective strategy will likely remain an integral component of pertussis prevention and control, even in the setting of new vaccines,” the investigators said.

Read more in Clinical Infectious Diseases (2017 Sep 28. doi: 10.1093/cid/cix724).

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASES

U.S. measles incidence since 2001 is low but increasing

, especially in the very young.

So, the importance of maintaining high vaccine coverage remains essential, concluded the authors of an analysis of confirmed U.S. measles cases, because endemic measles was eliminated nationwide in 2000.

Incidence of measles was highest in infants aged 6-11 months, followed by toddlers aged 12-15 months. Measles rates fell with age, starting at 16 months, Nakia S. Clemmons and her associates of the division of viral diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said in a research letter in JAMA (2017 Oct 3;318[13]:1279-81).

Higher incidence per million population occurred over time, from 0.28 in 2001 to 0.56 in 2015. Imported cases decreased from 47% in 2001 to 15% in 2015. Vaccinated patients decreased from 30% of U.S. measles cases in 2001 to 20% in 2015.

“The concurrent increase in incidence and declines in the proportion of imported and vaccinated cases (signifying relative increases in U.S.-acquired and unvaccinated cases) may suggest increased susceptibility and transmission after introductions in certain subpopulations,” the investigators said.

“The declining incidence with age, the high proportion of unvaccinated cases, and the decline in the proportion of vaccinated cases despite rate increases suggest that failure to vaccinate, rather than failure of vaccine performance, may be the main driver of measles transmission, emphasizing the importance of maintaining high vaccine coverage,” they added.

, especially in the very young.

So, the importance of maintaining high vaccine coverage remains essential, concluded the authors of an analysis of confirmed U.S. measles cases, because endemic measles was eliminated nationwide in 2000.

Incidence of measles was highest in infants aged 6-11 months, followed by toddlers aged 12-15 months. Measles rates fell with age, starting at 16 months, Nakia S. Clemmons and her associates of the division of viral diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said in a research letter in JAMA (2017 Oct 3;318[13]:1279-81).

Higher incidence per million population occurred over time, from 0.28 in 2001 to 0.56 in 2015. Imported cases decreased from 47% in 2001 to 15% in 2015. Vaccinated patients decreased from 30% of U.S. measles cases in 2001 to 20% in 2015.

“The concurrent increase in incidence and declines in the proportion of imported and vaccinated cases (signifying relative increases in U.S.-acquired and unvaccinated cases) may suggest increased susceptibility and transmission after introductions in certain subpopulations,” the investigators said.

“The declining incidence with age, the high proportion of unvaccinated cases, and the decline in the proportion of vaccinated cases despite rate increases suggest that failure to vaccinate, rather than failure of vaccine performance, may be the main driver of measles transmission, emphasizing the importance of maintaining high vaccine coverage,” they added.

, especially in the very young.

So, the importance of maintaining high vaccine coverage remains essential, concluded the authors of an analysis of confirmed U.S. measles cases, because endemic measles was eliminated nationwide in 2000.

Incidence of measles was highest in infants aged 6-11 months, followed by toddlers aged 12-15 months. Measles rates fell with age, starting at 16 months, Nakia S. Clemmons and her associates of the division of viral diseases at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, said in a research letter in JAMA (2017 Oct 3;318[13]:1279-81).

Higher incidence per million population occurred over time, from 0.28 in 2001 to 0.56 in 2015. Imported cases decreased from 47% in 2001 to 15% in 2015. Vaccinated patients decreased from 30% of U.S. measles cases in 2001 to 20% in 2015.

“The concurrent increase in incidence and declines in the proportion of imported and vaccinated cases (signifying relative increases in U.S.-acquired and unvaccinated cases) may suggest increased susceptibility and transmission after introductions in certain subpopulations,” the investigators said.

“The declining incidence with age, the high proportion of unvaccinated cases, and the decline in the proportion of vaccinated cases despite rate increases suggest that failure to vaccinate, rather than failure of vaccine performance, may be the main driver of measles transmission, emphasizing the importance of maintaining high vaccine coverage,” they added.

FROM JAMA

Not recommending LAIV didn’t reduce flu vaccination in Oregon children

Oregon researchers studying the effect of not recommending intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) in favor of injected influenza vaccines (IIV) for the 2016-2017 flu season found that the change in recommendation had a minimal impact on overall flu vaccination rates, but that patients who had been given injected flu vaccine previously were slightly more likely to return for it the following season.

Steve G. Robison, MPH, of the Immunization Program of the Oregon Health Authority in Salem, led the study to monitor the effects of the new recommendation in Oregon, where he and his coauthors noted that there is “a substantial vaccine-hesitant population” (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0516).

They considered data from the state’s immunization registry, simply counting seasonal immunization rates from 2012 to 2017. As a second assessment, they compared children who had previously received LAIV between Aug. 1 and Dec. 31, 2015, and children who received IIV during the same period, to see which cohort was more likely to return for flu vaccination the following season.

“Overall, 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season,” they reported. Those rates showed that the cohort with past injected vaccine was only 1.05 times more likely to return than the cohort with past nasal spray vaccine (95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.06). The investigators also concluded that overall rates have undergone “minimal changes” in the past 5 years, and the effect of the committee’s recommendation additionally was considered to be minimal.

Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon statefor immunization surveillance.

Oregon researchers studying the effect of not recommending intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) in favor of injected influenza vaccines (IIV) for the 2016-2017 flu season found that the change in recommendation had a minimal impact on overall flu vaccination rates, but that patients who had been given injected flu vaccine previously were slightly more likely to return for it the following season.

Steve G. Robison, MPH, of the Immunization Program of the Oregon Health Authority in Salem, led the study to monitor the effects of the new recommendation in Oregon, where he and his coauthors noted that there is “a substantial vaccine-hesitant population” (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0516).

They considered data from the state’s immunization registry, simply counting seasonal immunization rates from 2012 to 2017. As a second assessment, they compared children who had previously received LAIV between Aug. 1 and Dec. 31, 2015, and children who received IIV during the same period, to see which cohort was more likely to return for flu vaccination the following season.

“Overall, 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season,” they reported. Those rates showed that the cohort with past injected vaccine was only 1.05 times more likely to return than the cohort with past nasal spray vaccine (95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.06). The investigators also concluded that overall rates have undergone “minimal changes” in the past 5 years, and the effect of the committee’s recommendation additionally was considered to be minimal.

Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon statefor immunization surveillance.

Oregon researchers studying the effect of not recommending intranasal live attenuated influenza vaccines (LAIV) in favor of injected influenza vaccines (IIV) for the 2016-2017 flu season found that the change in recommendation had a minimal impact on overall flu vaccination rates, but that patients who had been given injected flu vaccine previously were slightly more likely to return for it the following season.

Steve G. Robison, MPH, of the Immunization Program of the Oregon Health Authority in Salem, led the study to monitor the effects of the new recommendation in Oregon, where he and his coauthors noted that there is “a substantial vaccine-hesitant population” (Pediatrics. 2017 Oct 6. doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0516).

They considered data from the state’s immunization registry, simply counting seasonal immunization rates from 2012 to 2017. As a second assessment, they compared children who had previously received LAIV between Aug. 1 and Dec. 31, 2015, and children who received IIV during the same period, to see which cohort was more likely to return for flu vaccination the following season.

“Overall, 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season,” they reported. Those rates showed that the cohort with past injected vaccine was only 1.05 times more likely to return than the cohort with past nasal spray vaccine (95% confidence interval, 1.04-1.06). The investigators also concluded that overall rates have undergone “minimal changes” in the past 5 years, and the effect of the committee’s recommendation additionally was considered to be minimal.

Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon statefor immunization surveillance.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: 53.1% of children in the study with previous LAIV and 56.4% with a previous IIV returned for an IIV during the 2016-2017 season.

Data source: Data from Oregon’s immunization registry.

Disclosures: Mr. Robison and his associates said they had no relevant financial disclosures. The study was funded in part by the CDC’s grants to Oregon state for immunization surveillance.

Increase in Kids Who Are Getting the HPV Vaccine

The HPV vaccine has led to “dramatic declines” in HPV infections, according to the CDC. Since the first HPV vaccine was introduced 10 years ago, the percentage of infections that cause cancers and genital warts has dropped by 71% among teenage girls and 61% among young women. According to the annual National Immunization Survey-Teen report, 60% of teens aged 13 to 17 years received ≥ 1 doses of HPV vaccine in 2016, up 4 percentage points from 2015.

More boys are getting the vaccine, too. About 56% of boys received their first dose (although that is still less than the 65% seen in girls)—representing a 6% increase from 2015; rates for girls remained stable.

As encouraging as those numbers are, there is more work to do, the CDC says. Although most adolescents have received the first dose, only 43% are up-to-date on all the recommended doses. The CDC recommends that 11- to 12-year-olds get 2 doses of HPV vaccine at least 6 months apart. The CDC updated its HPV vaccine recommendations in 2016 when new evidence showed that 2 doses of the vaccine provided levels of protection similar to those seen for 3 doses in older adolescents and young adults.

Parents can get the vaccine for their child during any doctor’s visit, but the CDC recommends that adolescents get the HPV vaccine during the same visit that they get whooping cough and meningitis vaccine.

The HPV vaccine has led to “dramatic declines” in HPV infections, according to the CDC. Since the first HPV vaccine was introduced 10 years ago, the percentage of infections that cause cancers and genital warts has dropped by 71% among teenage girls and 61% among young women. According to the annual National Immunization Survey-Teen report, 60% of teens aged 13 to 17 years received ≥ 1 doses of HPV vaccine in 2016, up 4 percentage points from 2015.

More boys are getting the vaccine, too. About 56% of boys received their first dose (although that is still less than the 65% seen in girls)—representing a 6% increase from 2015; rates for girls remained stable.

As encouraging as those numbers are, there is more work to do, the CDC says. Although most adolescents have received the first dose, only 43% are up-to-date on all the recommended doses. The CDC recommends that 11- to 12-year-olds get 2 doses of HPV vaccine at least 6 months apart. The CDC updated its HPV vaccine recommendations in 2016 when new evidence showed that 2 doses of the vaccine provided levels of protection similar to those seen for 3 doses in older adolescents and young adults.

Parents can get the vaccine for their child during any doctor’s visit, but the CDC recommends that adolescents get the HPV vaccine during the same visit that they get whooping cough and meningitis vaccine.

The HPV vaccine has led to “dramatic declines” in HPV infections, according to the CDC. Since the first HPV vaccine was introduced 10 years ago, the percentage of infections that cause cancers and genital warts has dropped by 71% among teenage girls and 61% among young women. According to the annual National Immunization Survey-Teen report, 60% of teens aged 13 to 17 years received ≥ 1 doses of HPV vaccine in 2016, up 4 percentage points from 2015.

More boys are getting the vaccine, too. About 56% of boys received their first dose (although that is still less than the 65% seen in girls)—representing a 6% increase from 2015; rates for girls remained stable.

As encouraging as those numbers are, there is more work to do, the CDC says. Although most adolescents have received the first dose, only 43% are up-to-date on all the recommended doses. The CDC recommends that 11- to 12-year-olds get 2 doses of HPV vaccine at least 6 months apart. The CDC updated its HPV vaccine recommendations in 2016 when new evidence showed that 2 doses of the vaccine provided levels of protection similar to those seen for 3 doses in older adolescents and young adults.

Parents can get the vaccine for their child during any doctor’s visit, but the CDC recommends that adolescents get the HPV vaccine during the same visit that they get whooping cough and meningitis vaccine.

Current pneumococcal vaccines knock out many serotypes, but others take their place

The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7 (PCV7) and 13 (PCV13) has significantly reduced pneumococcal colonization of the serotypes targeted by the vaccines, but serotypes not covered by these vaccines have picked up the slack, according to an analysis of more than 6,000 young Massachusetts children tested at well child or acute care visits over 15 years.

In the past 15 years, use of pneumococcal vaccines in the United States has led to dramatic declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in young children, reductions in pneumonia hospitalizations, and herd protection in older adults against disease that otherwise would be caused by the vaccinated serotypes, studies have found. But not all serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae are covered by the vaccines.

The data used in the Massachusetts study included results from nasopharyngeal swabs taken from 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age in various Massachusetts communities during six respiratory illness seasons during 2000-2001, 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, and 2013-2014. The highest rate of pneumococcal colonization was in 2011 at 32%, and the lowest was in 2004 at 23%, Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, of the Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, both in Boston, and her associates reported (Pediatrics. 2017;140[3]:e20170001).

In 2001, PCV7 serotypes were the most common, but after the rapid introduction of the vaccine, infection rates for those serotypes quickly declined, nearly disappearing by 2007. Serotype 19A became the most common serotype in 2004, but after the introduction of PCV13 in 2010, it and other serotypes targeted by PCV13 also began to decline. In 2014, the most common serotypes were 15B/C, 35B, 23B, 11A, and 23A.

Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for about a third of observed Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizations in 2001, but by 2014 they accounted for nearly all colonizations. In addition, the overall rate of infection did not decrease over the study period. While a reduction was seen from 2011 to 2014, it remains to be seen whether this drop is transient.

“Replacement with nonincluded serotypes remains a risk with vaccines that do not cover the full range of serotype diversity. As new selective pressures are applied, such as the introduction of a vaccine into a community, the void may be filled by nontargeted serotypes,” as was observed after PCV7, Dr. Lee and her fellow researchers noted.

Nonsusceptibility to erythromycin was most common in 2014, with 35% of pneumococcal isolates displaying either moderate susceptibility or resistance. Nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (12%), clindamycin (9%), and penicillin (6%) was significantly less common, and no isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance.

“First-line penicillins continue to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic across all age groups among young children in Massachusetts, which may result in the continued success of 19A associated with penicillin resistance,” the researchers said.

Risk factors associated with colonization by either PCV13 serotypes or non-PCV13 serotypes include younger age, more hours of child care exposure, and having a respiratory tract infection on the day of sampling. The presence of a smoker in the house and recent usage of antibiotics was associated with colonization by PCV13 serotypes but not by non-PCV13 serotypes.

“As newer pneumococcal vaccines are developed, there will continue to be a need for monitoring both the intended and unintended consequences of altering the nasopharyngeal niche through immunization,” Dr. Lee and her associates concluded.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

“The hope that IPD and antibiotic resistance would disappear after widespread use of PCV vaccines has yet to be realized,” Douglas S. Swanson, MD, and Christopher J. Harrison, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140[5]:e20172034).

While some invasive pneumococcal diseases, such as occult bacteremia and meningitis, have been significantly reduced due to PCV7 and PCV13, “one concern is whether some replacement serotypes could have invasive disease potential. For example, post-PCV7, there was increased severity of IPD from non-PCV7 serogroup organisms among children in the Intermountain West of the United States,” the authors noted. Newly dominant strains, such as post-PCV13 serotype 35B, could cause increased IPD in vulnerable populations, becoming the equivalent of a post-PCV7 serotype 19A.

While addressing emerging serotypes in additional PCVs is possible, reformulating the vaccine and obtaining Food and Drug Administration approval would take time and resources, with no clear guarantee of ultimate success, making “this strategy seem like playing a game of whack-a-mole. To overcome the phenomenon of serotype replacement, vaccine strategies need to expand beyond serotype specificity by identifying antigens common to all Streptococcus pneumoniae, regardless of serotype,” Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison said.

“Shifts back to less penicillin resistance may soon preclude the need for high dose amoxicillin for acute otitis media, and the near absence of occult Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia may drastically reduce empirical ceftriaxone for fever without a focus. To assist providers in ongoing vigilance for the now less frequent IPD, algorithms based on new epidemiologic data are in development and should decrease the number of ‘sepsis work-ups’ performed,” they said.

On-time PCV13 vaccination would help address the risk factor of young age, and judicious antibiotic use could further reduce antibiotic resistance. Social engineering approaches, although difficult, also might help. These approaches include continued parent education to restrict secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization, as well as having young children spend fewer hours in day care in order to reduce two other risk factors – pathogen exposure and frequency of viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison are with the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Both reported conducting pneumococcal research supported by funding from Pfizer.

“The hope that IPD and antibiotic resistance would disappear after widespread use of PCV vaccines has yet to be realized,” Douglas S. Swanson, MD, and Christopher J. Harrison, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140[5]:e20172034).

While some invasive pneumococcal diseases, such as occult bacteremia and meningitis, have been significantly reduced due to PCV7 and PCV13, “one concern is whether some replacement serotypes could have invasive disease potential. For example, post-PCV7, there was increased severity of IPD from non-PCV7 serogroup organisms among children in the Intermountain West of the United States,” the authors noted. Newly dominant strains, such as post-PCV13 serotype 35B, could cause increased IPD in vulnerable populations, becoming the equivalent of a post-PCV7 serotype 19A.

While addressing emerging serotypes in additional PCVs is possible, reformulating the vaccine and obtaining Food and Drug Administration approval would take time and resources, with no clear guarantee of ultimate success, making “this strategy seem like playing a game of whack-a-mole. To overcome the phenomenon of serotype replacement, vaccine strategies need to expand beyond serotype specificity by identifying antigens common to all Streptococcus pneumoniae, regardless of serotype,” Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison said.

“Shifts back to less penicillin resistance may soon preclude the need for high dose amoxicillin for acute otitis media, and the near absence of occult Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia may drastically reduce empirical ceftriaxone for fever without a focus. To assist providers in ongoing vigilance for the now less frequent IPD, algorithms based on new epidemiologic data are in development and should decrease the number of ‘sepsis work-ups’ performed,” they said.

On-time PCV13 vaccination would help address the risk factor of young age, and judicious antibiotic use could further reduce antibiotic resistance. Social engineering approaches, although difficult, also might help. These approaches include continued parent education to restrict secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization, as well as having young children spend fewer hours in day care in order to reduce two other risk factors – pathogen exposure and frequency of viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison are with the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Both reported conducting pneumococcal research supported by funding from Pfizer.

“The hope that IPD and antibiotic resistance would disappear after widespread use of PCV vaccines has yet to be realized,” Douglas S. Swanson, MD, and Christopher J. Harrison, MD, wrote in an accompanying editorial (Pediatrics. 2017;140[5]:e20172034).

While some invasive pneumococcal diseases, such as occult bacteremia and meningitis, have been significantly reduced due to PCV7 and PCV13, “one concern is whether some replacement serotypes could have invasive disease potential. For example, post-PCV7, there was increased severity of IPD from non-PCV7 serogroup organisms among children in the Intermountain West of the United States,” the authors noted. Newly dominant strains, such as post-PCV13 serotype 35B, could cause increased IPD in vulnerable populations, becoming the equivalent of a post-PCV7 serotype 19A.

While addressing emerging serotypes in additional PCVs is possible, reformulating the vaccine and obtaining Food and Drug Administration approval would take time and resources, with no clear guarantee of ultimate success, making “this strategy seem like playing a game of whack-a-mole. To overcome the phenomenon of serotype replacement, vaccine strategies need to expand beyond serotype specificity by identifying antigens common to all Streptococcus pneumoniae, regardless of serotype,” Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison said.

“Shifts back to less penicillin resistance may soon preclude the need for high dose amoxicillin for acute otitis media, and the near absence of occult Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteremia may drastically reduce empirical ceftriaxone for fever without a focus. To assist providers in ongoing vigilance for the now less frequent IPD, algorithms based on new epidemiologic data are in development and should decrease the number of ‘sepsis work-ups’ performed,” they said.

On-time PCV13 vaccination would help address the risk factor of young age, and judicious antibiotic use could further reduce antibiotic resistance. Social engineering approaches, although difficult, also might help. These approaches include continued parent education to restrict secondhand smoke exposure and the risk of S. pneumoniae nasopharyngeal colonization, as well as having young children spend fewer hours in day care in order to reduce two other risk factors – pathogen exposure and frequency of viral upper respiratory tract infections.

Dr. Swanson and Dr. Harrison are with the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Mercy Kansas City, University of Missouri-Kansas City. Both reported conducting pneumococcal research supported by funding from Pfizer.

The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7 (PCV7) and 13 (PCV13) has significantly reduced pneumococcal colonization of the serotypes targeted by the vaccines, but serotypes not covered by these vaccines have picked up the slack, according to an analysis of more than 6,000 young Massachusetts children tested at well child or acute care visits over 15 years.

In the past 15 years, use of pneumococcal vaccines in the United States has led to dramatic declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in young children, reductions in pneumonia hospitalizations, and herd protection in older adults against disease that otherwise would be caused by the vaccinated serotypes, studies have found. But not all serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae are covered by the vaccines.

The data used in the Massachusetts study included results from nasopharyngeal swabs taken from 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age in various Massachusetts communities during six respiratory illness seasons during 2000-2001, 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, and 2013-2014. The highest rate of pneumococcal colonization was in 2011 at 32%, and the lowest was in 2004 at 23%, Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, of the Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, both in Boston, and her associates reported (Pediatrics. 2017;140[3]:e20170001).

In 2001, PCV7 serotypes were the most common, but after the rapid introduction of the vaccine, infection rates for those serotypes quickly declined, nearly disappearing by 2007. Serotype 19A became the most common serotype in 2004, but after the introduction of PCV13 in 2010, it and other serotypes targeted by PCV13 also began to decline. In 2014, the most common serotypes were 15B/C, 35B, 23B, 11A, and 23A.

Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for about a third of observed Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizations in 2001, but by 2014 they accounted for nearly all colonizations. In addition, the overall rate of infection did not decrease over the study period. While a reduction was seen from 2011 to 2014, it remains to be seen whether this drop is transient.

“Replacement with nonincluded serotypes remains a risk with vaccines that do not cover the full range of serotype diversity. As new selective pressures are applied, such as the introduction of a vaccine into a community, the void may be filled by nontargeted serotypes,” as was observed after PCV7, Dr. Lee and her fellow researchers noted.

Nonsusceptibility to erythromycin was most common in 2014, with 35% of pneumococcal isolates displaying either moderate susceptibility or resistance. Nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (12%), clindamycin (9%), and penicillin (6%) was significantly less common, and no isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance.

“First-line penicillins continue to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic across all age groups among young children in Massachusetts, which may result in the continued success of 19A associated with penicillin resistance,” the researchers said.

Risk factors associated with colonization by either PCV13 serotypes or non-PCV13 serotypes include younger age, more hours of child care exposure, and having a respiratory tract infection on the day of sampling. The presence of a smoker in the house and recent usage of antibiotics was associated with colonization by PCV13 serotypes but not by non-PCV13 serotypes.

“As newer pneumococcal vaccines are developed, there will continue to be a need for monitoring both the intended and unintended consequences of altering the nasopharyngeal niche through immunization,” Dr. Lee and her associates concluded.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

The introduction of pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7 (PCV7) and 13 (PCV13) has significantly reduced pneumococcal colonization of the serotypes targeted by the vaccines, but serotypes not covered by these vaccines have picked up the slack, according to an analysis of more than 6,000 young Massachusetts children tested at well child or acute care visits over 15 years.

In the past 15 years, use of pneumococcal vaccines in the United States has led to dramatic declines in invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) in young children, reductions in pneumonia hospitalizations, and herd protection in older adults against disease that otherwise would be caused by the vaccinated serotypes, studies have found. But not all serotypes of Streptococcus pneumoniae are covered by the vaccines.

The data used in the Massachusetts study included results from nasopharyngeal swabs taken from 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age in various Massachusetts communities during six respiratory illness seasons during 2000-2001, 2003-2004, 2006-2007, 2008-2009, 2010-2011, and 2013-2014. The highest rate of pneumococcal colonization was in 2011 at 32%, and the lowest was in 2004 at 23%, Grace M. Lee, MD, MPH, of the Harvard Medical School and Harvard Pilgrim Health Care Institute, both in Boston, and her associates reported (Pediatrics. 2017;140[3]:e20170001).

In 2001, PCV7 serotypes were the most common, but after the rapid introduction of the vaccine, infection rates for those serotypes quickly declined, nearly disappearing by 2007. Serotype 19A became the most common serotype in 2004, but after the introduction of PCV13 in 2010, it and other serotypes targeted by PCV13 also began to decline. In 2014, the most common serotypes were 15B/C, 35B, 23B, 11A, and 23A.

Non-PCV13 serotypes accounted for about a third of observed Streptococcus pneumoniae colonizations in 2001, but by 2014 they accounted for nearly all colonizations. In addition, the overall rate of infection did not decrease over the study period. While a reduction was seen from 2011 to 2014, it remains to be seen whether this drop is transient.

“Replacement with nonincluded serotypes remains a risk with vaccines that do not cover the full range of serotype diversity. As new selective pressures are applied, such as the introduction of a vaccine into a community, the void may be filled by nontargeted serotypes,” as was observed after PCV7, Dr. Lee and her fellow researchers noted.

Nonsusceptibility to erythromycin was most common in 2014, with 35% of pneumococcal isolates displaying either moderate susceptibility or resistance. Nonsusceptibility to ceftriaxone (12%), clindamycin (9%), and penicillin (6%) was significantly less common, and no isolates were found to have vancomycin resistance.

“First-line penicillins continue to be the most frequently prescribed antibiotic across all age groups among young children in Massachusetts, which may result in the continued success of 19A associated with penicillin resistance,” the researchers said.

Risk factors associated with colonization by either PCV13 serotypes or non-PCV13 serotypes include younger age, more hours of child care exposure, and having a respiratory tract infection on the day of sampling. The presence of a smoker in the house and recent usage of antibiotics was associated with colonization by PCV13 serotypes but not by non-PCV13 serotypes.

“As newer pneumococcal vaccines are developed, there will continue to be a need for monitoring both the intended and unintended consequences of altering the nasopharyngeal niche through immunization,” Dr. Lee and her associates concluded.

This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Serotype 19A became the most dominant serotype in 2004 but was significantly reduced by 2014 and replaced largely by serotypes 15B/C and 35B.

Data source: An analysis of pneumococcal serotypes in 6,537 children younger than 7 years of age who had well-child or acute care visits during six surveillance periods from 2000 to 2014.

Disclosures: This work was funded by a National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and the National Institutes of Health. Marc Lipsitch, PhD; William P. Hanage, PhD; Ken Kleinman; Stephen I. Pelton, MD; and Susan S. Huang, MD, MPH, reported various conflicts of interest. Dr. Lee and the remaining investigators indicated that they had no potential conflicts of interest.

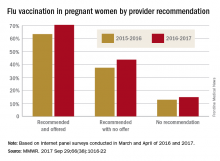

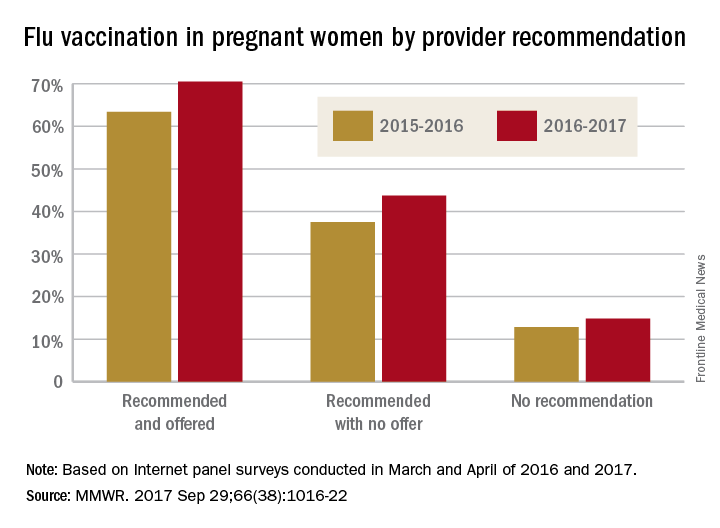

Just over half of pregnant women got flu vaccine in 2016-2017

Influenza vaccination among pregnant women during the 2016-2017 flu season was slightly higher than during the 2015-2016 season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overall coverage for 2016-2017 was 53.6% among pregnant women, compared with 49.9% in 2015-2016, continuing the overall rise seen over the last several flu seasons. Among pregnant women who received a recommendation from a health care provider and were offered vaccination, coverage was 70.5% in 2016-2017, while coverage was 43.7% among women who received a recommendation but no offer and 14.8% among those who did not receive a recommendation, the CDC reported (MMWR. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1016-22).

Among other subgroups, coverage by age for the 2016-2017 flu season was 41.7% for those aged 18-24 years, 58.4% for those aged 25-34 years, and 58.5% for those 35-49 years old. There also was considerable variation by race/ethnicity, with coverage at 61.2% for Hispanics, 55.4% for whites, 42.3% for blacks, and 51.7% for others. Coverage for the subgroups corresponded with the rates at which vaccination was recommended: Younger women were less likely than older women to receive a recommendation, and Hispanic and white women more likely to receive recommendations than did blacks and other races/ethnicities, the CDC said.

The 2017 data include 1,893 responses to an Internet panel survey conducted from March 28 to April 7, 2017. The analysis of the 2016 panel survey, which was conducted from March 29 to April 7, 2016, included responses from 1,692 women.

Influenza vaccination among pregnant women during the 2016-2017 flu season was slightly higher than during the 2015-2016 season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overall coverage for 2016-2017 was 53.6% among pregnant women, compared with 49.9% in 2015-2016, continuing the overall rise seen over the last several flu seasons. Among pregnant women who received a recommendation from a health care provider and were offered vaccination, coverage was 70.5% in 2016-2017, while coverage was 43.7% among women who received a recommendation but no offer and 14.8% among those who did not receive a recommendation, the CDC reported (MMWR. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1016-22).

Among other subgroups, coverage by age for the 2016-2017 flu season was 41.7% for those aged 18-24 years, 58.4% for those aged 25-34 years, and 58.5% for those 35-49 years old. There also was considerable variation by race/ethnicity, with coverage at 61.2% for Hispanics, 55.4% for whites, 42.3% for blacks, and 51.7% for others. Coverage for the subgroups corresponded with the rates at which vaccination was recommended: Younger women were less likely than older women to receive a recommendation, and Hispanic and white women more likely to receive recommendations than did blacks and other races/ethnicities, the CDC said.

The 2017 data include 1,893 responses to an Internet panel survey conducted from March 28 to April 7, 2017. The analysis of the 2016 panel survey, which was conducted from March 29 to April 7, 2016, included responses from 1,692 women.

Influenza vaccination among pregnant women during the 2016-2017 flu season was slightly higher than during the 2015-2016 season, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Overall coverage for 2016-2017 was 53.6% among pregnant women, compared with 49.9% in 2015-2016, continuing the overall rise seen over the last several flu seasons. Among pregnant women who received a recommendation from a health care provider and were offered vaccination, coverage was 70.5% in 2016-2017, while coverage was 43.7% among women who received a recommendation but no offer and 14.8% among those who did not receive a recommendation, the CDC reported (MMWR. 2017 Sep 29;66[38]:1016-22).

Among other subgroups, coverage by age for the 2016-2017 flu season was 41.7% for those aged 18-24 years, 58.4% for those aged 25-34 years, and 58.5% for those 35-49 years old. There also was considerable variation by race/ethnicity, with coverage at 61.2% for Hispanics, 55.4% for whites, 42.3% for blacks, and 51.7% for others. Coverage for the subgroups corresponded with the rates at which vaccination was recommended: Younger women were less likely than older women to receive a recommendation, and Hispanic and white women more likely to receive recommendations than did blacks and other races/ethnicities, the CDC said.

The 2017 data include 1,893 responses to an Internet panel survey conducted from March 28 to April 7, 2017. The analysis of the 2016 panel survey, which was conducted from March 29 to April 7, 2016, included responses from 1,692 women.

FROM MMWR