User login

Beginning estrogen soon after menopause slows atherosclerosis progression

PHOENIX – Oral estrogen therapy taken within 6 years after the onset of menopause significantly reduced progression of lipid deposition in the carotid arterial wall, compared with placebo. However, starting oral estrogen 10 years after menopause did not confer a similar benefit.

“The clinical practice of estradiol therapy has been nothing short of a roller coaster ride,” lead study author Roksana Karim, PhD, MBBS, said in an interview at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting sponsored by the American Heart Association. “Clinicians have been sort of conservative in terms of prescribing estradiol therapy. But over the last 2 decades things have changed, and eventually the timing hypothesis evolved based on the final analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative results as well.”

The findings come from a secondary analysis of the Early Versus Late Intervention Trial With Estradiol (ELITE), which examined the effects of oral 17-beta-estradiol (estrogen) on the progression of early atherosclerosis and cognitive decline in healthy postmenopausal women.

In the original trial, 643 healthy postmenopausal women were randomized to receive 1 mg/day of estradiol or a placebo pill either within 6 years after the onset of menopause or more than a decade after menopause (N Engl J Med 2016;374[13]:1221-31). All study participants took estradiol or placebo daily for an average of 5 years. The study’s initial findings showed that the mean carotid intima-media thickness progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo, but only in women who initiated hormone therapy within 6 years of menopause onset.

For the current analysis, researchers led by Dr. Karim looked further into estradiol’s impact on heart health by using echogenicity to analyze lipids in the arterial wall among the ELITE participants. The main outcome of interest was gray-scale median (GSM, unitless), a qualitative measure of atherosclerosis based on echogenicity obtained by high-resolution ultrasonography of the common carotid arterial wall. Whereas higher GSM values result with plaques rich in calcium and fibrous tissue, lower GSM values indicate more lipid deposition.

Dr. Karim, an associate professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and colleagues assessed GSM and serum concentrations of estradiol every 6 months over a median 5-year trial period, and used linear mixed effects regression models to compare the rate of GSM progression between the randomized groups within time-since-menopause strata.

The researchers found that effect of estradiol on the annual rate of GSM progression significantly differed between women in the early and late postmenopause groups (P for interaction = .006). Specifically, the annual GSM progression rate among women in early postmenopause fell by 0.30 per year in women taking estradiol, compared with 1.41 per year in those in the placebo group (P less than .0001), indicating significantly more atherosclerosis in the placebo group. On the other hand, the annual GSM progression rate was not significantly different between the estradiol and placebo groups among the late postmenopausal women (P = .37).

“I think this should comfort clinicians in terms of prescribing estradiol therapy to women who don’t have any contraindications and who are within 6 years of menopause,” Dr. Karim said. “Accumulation of lipids is the key event for atherosclerosis progression.” She and her colleagues also observed that the positive association between mean on-trial serum estradiol levels and GSM progression rate was stronger and significant among early postmenopausal women (P = .008), compared with women in the late postmenopausal group (P = .003). However, this differential association between estradiol level and GSM progression rate was not statistically significant (P for interaction = .33).

“This study is important and raises a critical question: Is there a time period where getting hormone therapy would be most beneficial for the heart?” Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the New York University women’s heart program and senior advisor for women’s health strategy at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. “I think more studies and more analyses are needed, but we haven’t changed the indications for estradiol. We’re not giving estradiol to prevent progression of heart disease. We use estradiol hormone therapy as indicated for women who are having menopausal symptoms.”

Dr. Karim and colleagues plan to conduct a follow-up analysis from the same cohort of ELITE study participants to validate the findings by assessing lipid particles and markers of inflammation.

She reported having no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging.

SOURCE: Karim R et al. Epi/Lifestyle 2020, Abstract MP09.

PHOENIX – Oral estrogen therapy taken within 6 years after the onset of menopause significantly reduced progression of lipid deposition in the carotid arterial wall, compared with placebo. However, starting oral estrogen 10 years after menopause did not confer a similar benefit.

“The clinical practice of estradiol therapy has been nothing short of a roller coaster ride,” lead study author Roksana Karim, PhD, MBBS, said in an interview at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting sponsored by the American Heart Association. “Clinicians have been sort of conservative in terms of prescribing estradiol therapy. But over the last 2 decades things have changed, and eventually the timing hypothesis evolved based on the final analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative results as well.”

The findings come from a secondary analysis of the Early Versus Late Intervention Trial With Estradiol (ELITE), which examined the effects of oral 17-beta-estradiol (estrogen) on the progression of early atherosclerosis and cognitive decline in healthy postmenopausal women.

In the original trial, 643 healthy postmenopausal women were randomized to receive 1 mg/day of estradiol or a placebo pill either within 6 years after the onset of menopause or more than a decade after menopause (N Engl J Med 2016;374[13]:1221-31). All study participants took estradiol or placebo daily for an average of 5 years. The study’s initial findings showed that the mean carotid intima-media thickness progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo, but only in women who initiated hormone therapy within 6 years of menopause onset.

For the current analysis, researchers led by Dr. Karim looked further into estradiol’s impact on heart health by using echogenicity to analyze lipids in the arterial wall among the ELITE participants. The main outcome of interest was gray-scale median (GSM, unitless), a qualitative measure of atherosclerosis based on echogenicity obtained by high-resolution ultrasonography of the common carotid arterial wall. Whereas higher GSM values result with plaques rich in calcium and fibrous tissue, lower GSM values indicate more lipid deposition.

Dr. Karim, an associate professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and colleagues assessed GSM and serum concentrations of estradiol every 6 months over a median 5-year trial period, and used linear mixed effects regression models to compare the rate of GSM progression between the randomized groups within time-since-menopause strata.

The researchers found that effect of estradiol on the annual rate of GSM progression significantly differed between women in the early and late postmenopause groups (P for interaction = .006). Specifically, the annual GSM progression rate among women in early postmenopause fell by 0.30 per year in women taking estradiol, compared with 1.41 per year in those in the placebo group (P less than .0001), indicating significantly more atherosclerosis in the placebo group. On the other hand, the annual GSM progression rate was not significantly different between the estradiol and placebo groups among the late postmenopausal women (P = .37).

“I think this should comfort clinicians in terms of prescribing estradiol therapy to women who don’t have any contraindications and who are within 6 years of menopause,” Dr. Karim said. “Accumulation of lipids is the key event for atherosclerosis progression.” She and her colleagues also observed that the positive association between mean on-trial serum estradiol levels and GSM progression rate was stronger and significant among early postmenopausal women (P = .008), compared with women in the late postmenopausal group (P = .003). However, this differential association between estradiol level and GSM progression rate was not statistically significant (P for interaction = .33).

“This study is important and raises a critical question: Is there a time period where getting hormone therapy would be most beneficial for the heart?” Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the New York University women’s heart program and senior advisor for women’s health strategy at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. “I think more studies and more analyses are needed, but we haven’t changed the indications for estradiol. We’re not giving estradiol to prevent progression of heart disease. We use estradiol hormone therapy as indicated for women who are having menopausal symptoms.”

Dr. Karim and colleagues plan to conduct a follow-up analysis from the same cohort of ELITE study participants to validate the findings by assessing lipid particles and markers of inflammation.

She reported having no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging.

SOURCE: Karim R et al. Epi/Lifestyle 2020, Abstract MP09.

PHOENIX – Oral estrogen therapy taken within 6 years after the onset of menopause significantly reduced progression of lipid deposition in the carotid arterial wall, compared with placebo. However, starting oral estrogen 10 years after menopause did not confer a similar benefit.

“The clinical practice of estradiol therapy has been nothing short of a roller coaster ride,” lead study author Roksana Karim, PhD, MBBS, said in an interview at the Epidemiology and Prevention/Lifestyle and Cardiometabolic Health meeting sponsored by the American Heart Association. “Clinicians have been sort of conservative in terms of prescribing estradiol therapy. But over the last 2 decades things have changed, and eventually the timing hypothesis evolved based on the final analysis of the Women’s Health Initiative results as well.”

The findings come from a secondary analysis of the Early Versus Late Intervention Trial With Estradiol (ELITE), which examined the effects of oral 17-beta-estradiol (estrogen) on the progression of early atherosclerosis and cognitive decline in healthy postmenopausal women.

In the original trial, 643 healthy postmenopausal women were randomized to receive 1 mg/day of estradiol or a placebo pill either within 6 years after the onset of menopause or more than a decade after menopause (N Engl J Med 2016;374[13]:1221-31). All study participants took estradiol or placebo daily for an average of 5 years. The study’s initial findings showed that the mean carotid intima-media thickness progression rate was decreased by 0.0034 mm per year with estradiol, compared with placebo, but only in women who initiated hormone therapy within 6 years of menopause onset.

For the current analysis, researchers led by Dr. Karim looked further into estradiol’s impact on heart health by using echogenicity to analyze lipids in the arterial wall among the ELITE participants. The main outcome of interest was gray-scale median (GSM, unitless), a qualitative measure of atherosclerosis based on echogenicity obtained by high-resolution ultrasonography of the common carotid arterial wall. Whereas higher GSM values result with plaques rich in calcium and fibrous tissue, lower GSM values indicate more lipid deposition.

Dr. Karim, an associate professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and colleagues assessed GSM and serum concentrations of estradiol every 6 months over a median 5-year trial period, and used linear mixed effects regression models to compare the rate of GSM progression between the randomized groups within time-since-menopause strata.

The researchers found that effect of estradiol on the annual rate of GSM progression significantly differed between women in the early and late postmenopause groups (P for interaction = .006). Specifically, the annual GSM progression rate among women in early postmenopause fell by 0.30 per year in women taking estradiol, compared with 1.41 per year in those in the placebo group (P less than .0001), indicating significantly more atherosclerosis in the placebo group. On the other hand, the annual GSM progression rate was not significantly different between the estradiol and placebo groups among the late postmenopausal women (P = .37).

“I think this should comfort clinicians in terms of prescribing estradiol therapy to women who don’t have any contraindications and who are within 6 years of menopause,” Dr. Karim said. “Accumulation of lipids is the key event for atherosclerosis progression.” She and her colleagues also observed that the positive association between mean on-trial serum estradiol levels and GSM progression rate was stronger and significant among early postmenopausal women (P = .008), compared with women in the late postmenopausal group (P = .003). However, this differential association between estradiol level and GSM progression rate was not statistically significant (P for interaction = .33).

“This study is important and raises a critical question: Is there a time period where getting hormone therapy would be most beneficial for the heart?” Nieca Goldberg, MD, medical director of the New York University women’s heart program and senior advisor for women’s health strategy at NYU Langone Health, said in an interview. “I think more studies and more analyses are needed, but we haven’t changed the indications for estradiol. We’re not giving estradiol to prevent progression of heart disease. We use estradiol hormone therapy as indicated for women who are having menopausal symptoms.”

Dr. Karim and colleagues plan to conduct a follow-up analysis from the same cohort of ELITE study participants to validate the findings by assessing lipid particles and markers of inflammation.

She reported having no financial disclosures. The study was funded by the National Institute on Aging.

SOURCE: Karim R et al. Epi/Lifestyle 2020, Abstract MP09.

REPORTING FROM EPI/LIFESTYLE 2020

Family history of MI may increase CVD mortality after bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy

Family history of premature MI (FHPMI) in women with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) modifies the increased mortality associated with heart disease and cardiovascular disease in those women, according to an analysis published in Menopause.

Duke Appiah, PhD, of the department of public health at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, and colleagues drew data for 4,066 postmenopausal women aged 40 years and older from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (1988-1994). Women were excluded if they had partial or unilateral oophorectomy; unknown or missing age at menopause; or prevalent MI, stroke, or heart failure, which left a sample of 2,763 women for the analysis.

Women with BSO were considered postmenopausal if they had not experienced a menstrual period within the previous 12 months. Women were asked whether any blood relatives, and especially any first-degree relatives, had a heart attack before age 50 years, which was considered premature MI. The average age at baseline was 62 years. Of those 2,763 women, 610 women had BSO, 338 had FHPMI, and 95 had both, which yields weighted proportions of 24%, 15%, and 5%, respectively.

When compared with having neither factor, presence of any FHPMI was modestly associated with increased risk of mortality from heart disease (HD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and all causes in the multivariable adjusted analysis, and having undergone BSO was not significantly associated with any of those on its own. However, the combination of those two factors yielded much higher multivariable adjusted hazard ratios – HD mortality, 2.88; CVD mortality, 2.05; and all-cause mortality, 1.58.

These multivariable adjusted HRs were even more dramatic with first-degree FHPMI and BSO: 3.51 for HD mortality, 2.55 for CVD mortality, and 1.63 for all-cause mortality.

In the women who had the combination of FHPMI and BSO, the elevated risks of HD, CVD, and all-cause mortality “were stronger in women who underwent BSO before the age of 45 years than among those who had this procedure at or after the age of 45 years,” reported Dr. Appiah and colleagues. A significantly elevated risk of HD, CVD, or all-cause mortality was not evident in women with BSO alone “regardless of age at surgery.”

“This study provides additional evidence that removal of the ovaries before the natural age of menopause is associated with multiple adverse long-term health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and early mortality and should be strongly discouraged in women who are not at increased genetic risk for ovarian cancer,” Stephanie Faubion, MD, medical director of North American of Menopause Science, commented in a press release. She was not involved in the study.

Limitations of the study include how FHPMI was self-reported; however, the investigators suggested that, given findings of other research regarding reporting family history (Genet Epidemiol. 1999;17:141-50), the true rate may actually have been underreported. The investigators cited the large, population-based sample size as one of the study’s strengths, suggesting it helps make the findings generalizable.

The investigators disclosed no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Appiah D et al. Menopause. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001522.

Family history of premature MI (FHPMI) in women with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) modifies the increased mortality associated with heart disease and cardiovascular disease in those women, according to an analysis published in Menopause.

Duke Appiah, PhD, of the department of public health at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, and colleagues drew data for 4,066 postmenopausal women aged 40 years and older from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (1988-1994). Women were excluded if they had partial or unilateral oophorectomy; unknown or missing age at menopause; or prevalent MI, stroke, or heart failure, which left a sample of 2,763 women for the analysis.

Women with BSO were considered postmenopausal if they had not experienced a menstrual period within the previous 12 months. Women were asked whether any blood relatives, and especially any first-degree relatives, had a heart attack before age 50 years, which was considered premature MI. The average age at baseline was 62 years. Of those 2,763 women, 610 women had BSO, 338 had FHPMI, and 95 had both, which yields weighted proportions of 24%, 15%, and 5%, respectively.

When compared with having neither factor, presence of any FHPMI was modestly associated with increased risk of mortality from heart disease (HD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and all causes in the multivariable adjusted analysis, and having undergone BSO was not significantly associated with any of those on its own. However, the combination of those two factors yielded much higher multivariable adjusted hazard ratios – HD mortality, 2.88; CVD mortality, 2.05; and all-cause mortality, 1.58.

These multivariable adjusted HRs were even more dramatic with first-degree FHPMI and BSO: 3.51 for HD mortality, 2.55 for CVD mortality, and 1.63 for all-cause mortality.

In the women who had the combination of FHPMI and BSO, the elevated risks of HD, CVD, and all-cause mortality “were stronger in women who underwent BSO before the age of 45 years than among those who had this procedure at or after the age of 45 years,” reported Dr. Appiah and colleagues. A significantly elevated risk of HD, CVD, or all-cause mortality was not evident in women with BSO alone “regardless of age at surgery.”

“This study provides additional evidence that removal of the ovaries before the natural age of menopause is associated with multiple adverse long-term health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and early mortality and should be strongly discouraged in women who are not at increased genetic risk for ovarian cancer,” Stephanie Faubion, MD, medical director of North American of Menopause Science, commented in a press release. She was not involved in the study.

Limitations of the study include how FHPMI was self-reported; however, the investigators suggested that, given findings of other research regarding reporting family history (Genet Epidemiol. 1999;17:141-50), the true rate may actually have been underreported. The investigators cited the large, population-based sample size as one of the study’s strengths, suggesting it helps make the findings generalizable.

The investigators disclosed no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Appiah D et al. Menopause. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001522.

Family history of premature MI (FHPMI) in women with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) modifies the increased mortality associated with heart disease and cardiovascular disease in those women, according to an analysis published in Menopause.

Duke Appiah, PhD, of the department of public health at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, Lubbock, and colleagues drew data for 4,066 postmenopausal women aged 40 years and older from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (1988-1994). Women were excluded if they had partial or unilateral oophorectomy; unknown or missing age at menopause; or prevalent MI, stroke, or heart failure, which left a sample of 2,763 women for the analysis.

Women with BSO were considered postmenopausal if they had not experienced a menstrual period within the previous 12 months. Women were asked whether any blood relatives, and especially any first-degree relatives, had a heart attack before age 50 years, which was considered premature MI. The average age at baseline was 62 years. Of those 2,763 women, 610 women had BSO, 338 had FHPMI, and 95 had both, which yields weighted proportions of 24%, 15%, and 5%, respectively.

When compared with having neither factor, presence of any FHPMI was modestly associated with increased risk of mortality from heart disease (HD), cardiovascular disease (CVD), and all causes in the multivariable adjusted analysis, and having undergone BSO was not significantly associated with any of those on its own. However, the combination of those two factors yielded much higher multivariable adjusted hazard ratios – HD mortality, 2.88; CVD mortality, 2.05; and all-cause mortality, 1.58.

These multivariable adjusted HRs were even more dramatic with first-degree FHPMI and BSO: 3.51 for HD mortality, 2.55 for CVD mortality, and 1.63 for all-cause mortality.

In the women who had the combination of FHPMI and BSO, the elevated risks of HD, CVD, and all-cause mortality “were stronger in women who underwent BSO before the age of 45 years than among those who had this procedure at or after the age of 45 years,” reported Dr. Appiah and colleagues. A significantly elevated risk of HD, CVD, or all-cause mortality was not evident in women with BSO alone “regardless of age at surgery.”

“This study provides additional evidence that removal of the ovaries before the natural age of menopause is associated with multiple adverse long-term health outcomes, including cardiovascular disease and early mortality and should be strongly discouraged in women who are not at increased genetic risk for ovarian cancer,” Stephanie Faubion, MD, medical director of North American of Menopause Science, commented in a press release. She was not involved in the study.

Limitations of the study include how FHPMI was self-reported; however, the investigators suggested that, given findings of other research regarding reporting family history (Genet Epidemiol. 1999;17:141-50), the true rate may actually have been underreported. The investigators cited the large, population-based sample size as one of the study’s strengths, suggesting it helps make the findings generalizable.

The investigators disclosed no external funding or conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Appiah D et al. Menopause. 2020 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GME.0000000000001522.

FROM MENOPAUSE

In a public health crisis, obstetric collaboration is mission-critical

With the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) monopolizing the news cycle, fear and misinformation are at an all-time high. Public health officials and physicians are accelerating education outreach to the public to address misinformation, and identify and care for patients who may have been exposed to the virus.

In times of public health crises, pregnant women have unique and pressing concerns about their personal health and the health of their unborn children. While not often mentioned in major news coverage, obstetricians play a critical role during health crises because of their uniquely personal role with patients during all stages of pregnancy, providing this vulnerable population with the most up-to-date information and following the latest guidelines for recommended care.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 is breaking unfamiliar new ground. We know that pregnant women are at higher risk for viral infection – annually, influenza is a grim reminder that pregnant women are more immunocompromised than the general public – but we do not yet have data to confirm or refute that pregnant women have a higher susceptibility to COVID-19 than the rest of the adult population. We also do not know enough about COVID-19 transmission, including whether the virus can cross the transplacental barrier to affect a fetus, or whether it can be transmitted through breast milk.

As private practice community obstetricians work to protect their patients during this public health crisis, Ob hospitalists can play an important role in supporting them in the provision of patient care.

First, Ob hospitalists are highly-trained specialists who can help ensure that pregnant patients who seek care at the hospital – either with viral symptoms or with separate pregnancy-related concerns – are protected during triage until the treating community obstetrician can take the reins.

When a pregnant woman presents at a hospital, in most cases she will bypass the ED and instead be sent directly to the labor and delivery (L&D) unit. During a viral outbreak, there are two major concerns with this approach. For one thing, it means an immunocompromised woman is being sent through the hospital to get to L&D, and along the path, is exposed to every airborne pathogen in the facility (and, if she is already infected, exposes others along the way). In addition, in hospitals without an Ob hospitalist on site, the patient generally is not immediately triaged by a physician, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner upon arrival because those clinicians are not consistently on site in L&D.

In times of viral pandemics, new approaches are warranted. For hospitals with contracted L&D management with hospitalists, hospitalists work closely with department heads to implement protocols loosely based on the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) model established by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Just as the ESI algorithm guides clinical stratification of patients, in times of reported viral outbreaks, L&D should consider triage of all pregnant women at higher levels of acuity, regardless of presentation status. In particular, if they show clinical symptoms, they should be masked, accompanied to the L&D unit by protected personnel, separated from other patients in areas of forced proximity such as hallways and elevators, and triaged in a secure single-patient room with a closed door (ideally at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas).

If the patient has traveled to an area of outbreak, reports exposure to travelers who have visited high-risk areas, has had contact with individuals who tested positive for COVID-19, or exhibits any clinical symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, dry cough, fatigue, etc.), her care management should adhere to standing hospital emergency protocols. Following consultation with the assigned community obstetrician, the Ob hospitalist and hospital staff should contact their local/state health departments immediately for all cases of patients who show symptoms to determine if the patient meets requirements for a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19. The state/local health department will work with clinicians to collect, store, and ship clinical specimens appropriately. Very ill patients may need to be treated in an intensive care setting where respiratory status can be closely monitored.

At Ob Hospitalist Group, our body of evidence from our large national footprint has informed the development of standard sets of protocols for delivery complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage, as well as a cesarean section reduction toolkit to combat medically unnecessary cesarean sections. OB hospitalists therefore can assist with refining COVID-19 protocols specifically for the L&D setting, using evidence-based data to tailor protocols to address public health emergencies as they evolve.

The second way that Ob hospitalists can support their colleagues is by covering L&D 24/7 so that community obstetricians can focus on other pressing medical needs. From our experience with other outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza, we anticipate that obstetricians in private practice likely will have their hands full juggling a regular patient load, fielding calls from concerned patients, and caring for infected or ill patients who are being treated in an outpatient setting. Adding to that plate the need to rush to the hospital to clinically assess a patient for COVID-19 or for a delivery only compounds stress and exhaustion. At Ob Hospitalist Group, our hospitalist programs provide coverage and support to community obstetricians until they can arrive at the hospital or when the woman has no assigned obstetrician, reducing the pressure on community obstetricians to rush through their schedules.

Diagnostic and pharmaceutical companies are collaborating with public health officials to expedite diagnostic testing staff, hospital treatment capacity, vaccines, and even early therapies that may help to minimize severity. But right now, as clinicians work to protect their vulnerable patients, a close collaboration between community obstetricians and Ob hospitalists will help to keep patients and health care personnel safe and healthy – a goal that should apply not only to public health crises, but to the provision of maternal care every day.

Dr. Simon is chief medical officer at Ob Hospitalist Group (OBHG), is a board-certified ob.gyn., and former head of the department of obstetrics and gynecology for a U.S. hospital. He has no relevant conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

With the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) monopolizing the news cycle, fear and misinformation are at an all-time high. Public health officials and physicians are accelerating education outreach to the public to address misinformation, and identify and care for patients who may have been exposed to the virus.

In times of public health crises, pregnant women have unique and pressing concerns about their personal health and the health of their unborn children. While not often mentioned in major news coverage, obstetricians play a critical role during health crises because of their uniquely personal role with patients during all stages of pregnancy, providing this vulnerable population with the most up-to-date information and following the latest guidelines for recommended care.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 is breaking unfamiliar new ground. We know that pregnant women are at higher risk for viral infection – annually, influenza is a grim reminder that pregnant women are more immunocompromised than the general public – but we do not yet have data to confirm or refute that pregnant women have a higher susceptibility to COVID-19 than the rest of the adult population. We also do not know enough about COVID-19 transmission, including whether the virus can cross the transplacental barrier to affect a fetus, or whether it can be transmitted through breast milk.

As private practice community obstetricians work to protect their patients during this public health crisis, Ob hospitalists can play an important role in supporting them in the provision of patient care.

First, Ob hospitalists are highly-trained specialists who can help ensure that pregnant patients who seek care at the hospital – either with viral symptoms or with separate pregnancy-related concerns – are protected during triage until the treating community obstetrician can take the reins.

When a pregnant woman presents at a hospital, in most cases she will bypass the ED and instead be sent directly to the labor and delivery (L&D) unit. During a viral outbreak, there are two major concerns with this approach. For one thing, it means an immunocompromised woman is being sent through the hospital to get to L&D, and along the path, is exposed to every airborne pathogen in the facility (and, if she is already infected, exposes others along the way). In addition, in hospitals without an Ob hospitalist on site, the patient generally is not immediately triaged by a physician, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner upon arrival because those clinicians are not consistently on site in L&D.

In times of viral pandemics, new approaches are warranted. For hospitals with contracted L&D management with hospitalists, hospitalists work closely with department heads to implement protocols loosely based on the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) model established by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Just as the ESI algorithm guides clinical stratification of patients, in times of reported viral outbreaks, L&D should consider triage of all pregnant women at higher levels of acuity, regardless of presentation status. In particular, if they show clinical symptoms, they should be masked, accompanied to the L&D unit by protected personnel, separated from other patients in areas of forced proximity such as hallways and elevators, and triaged in a secure single-patient room with a closed door (ideally at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas).

If the patient has traveled to an area of outbreak, reports exposure to travelers who have visited high-risk areas, has had contact with individuals who tested positive for COVID-19, or exhibits any clinical symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, dry cough, fatigue, etc.), her care management should adhere to standing hospital emergency protocols. Following consultation with the assigned community obstetrician, the Ob hospitalist and hospital staff should contact their local/state health departments immediately for all cases of patients who show symptoms to determine if the patient meets requirements for a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19. The state/local health department will work with clinicians to collect, store, and ship clinical specimens appropriately. Very ill patients may need to be treated in an intensive care setting where respiratory status can be closely monitored.

At Ob Hospitalist Group, our body of evidence from our large national footprint has informed the development of standard sets of protocols for delivery complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage, as well as a cesarean section reduction toolkit to combat medically unnecessary cesarean sections. OB hospitalists therefore can assist with refining COVID-19 protocols specifically for the L&D setting, using evidence-based data to tailor protocols to address public health emergencies as they evolve.

The second way that Ob hospitalists can support their colleagues is by covering L&D 24/7 so that community obstetricians can focus on other pressing medical needs. From our experience with other outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza, we anticipate that obstetricians in private practice likely will have their hands full juggling a regular patient load, fielding calls from concerned patients, and caring for infected or ill patients who are being treated in an outpatient setting. Adding to that plate the need to rush to the hospital to clinically assess a patient for COVID-19 or for a delivery only compounds stress and exhaustion. At Ob Hospitalist Group, our hospitalist programs provide coverage and support to community obstetricians until they can arrive at the hospital or when the woman has no assigned obstetrician, reducing the pressure on community obstetricians to rush through their schedules.

Diagnostic and pharmaceutical companies are collaborating with public health officials to expedite diagnostic testing staff, hospital treatment capacity, vaccines, and even early therapies that may help to minimize severity. But right now, as clinicians work to protect their vulnerable patients, a close collaboration between community obstetricians and Ob hospitalists will help to keep patients and health care personnel safe and healthy – a goal that should apply not only to public health crises, but to the provision of maternal care every day.

Dr. Simon is chief medical officer at Ob Hospitalist Group (OBHG), is a board-certified ob.gyn., and former head of the department of obstetrics and gynecology for a U.S. hospital. He has no relevant conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

With the novel coronavirus (COVID-19) monopolizing the news cycle, fear and misinformation are at an all-time high. Public health officials and physicians are accelerating education outreach to the public to address misinformation, and identify and care for patients who may have been exposed to the virus.

In times of public health crises, pregnant women have unique and pressing concerns about their personal health and the health of their unborn children. While not often mentioned in major news coverage, obstetricians play a critical role during health crises because of their uniquely personal role with patients during all stages of pregnancy, providing this vulnerable population with the most up-to-date information and following the latest guidelines for recommended care.

Unfortunately, COVID-19 is breaking unfamiliar new ground. We know that pregnant women are at higher risk for viral infection – annually, influenza is a grim reminder that pregnant women are more immunocompromised than the general public – but we do not yet have data to confirm or refute that pregnant women have a higher susceptibility to COVID-19 than the rest of the adult population. We also do not know enough about COVID-19 transmission, including whether the virus can cross the transplacental barrier to affect a fetus, or whether it can be transmitted through breast milk.

As private practice community obstetricians work to protect their patients during this public health crisis, Ob hospitalists can play an important role in supporting them in the provision of patient care.

First, Ob hospitalists are highly-trained specialists who can help ensure that pregnant patients who seek care at the hospital – either with viral symptoms or with separate pregnancy-related concerns – are protected during triage until the treating community obstetrician can take the reins.

When a pregnant woman presents at a hospital, in most cases she will bypass the ED and instead be sent directly to the labor and delivery (L&D) unit. During a viral outbreak, there are two major concerns with this approach. For one thing, it means an immunocompromised woman is being sent through the hospital to get to L&D, and along the path, is exposed to every airborne pathogen in the facility (and, if she is already infected, exposes others along the way). In addition, in hospitals without an Ob hospitalist on site, the patient generally is not immediately triaged by a physician, physician’s assistant, or nurse practitioner upon arrival because those clinicians are not consistently on site in L&D.

In times of viral pandemics, new approaches are warranted. For hospitals with contracted L&D management with hospitalists, hospitalists work closely with department heads to implement protocols loosely based on the Emergency Severity Index (ESI) model established by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Just as the ESI algorithm guides clinical stratification of patients, in times of reported viral outbreaks, L&D should consider triage of all pregnant women at higher levels of acuity, regardless of presentation status. In particular, if they show clinical symptoms, they should be masked, accompanied to the L&D unit by protected personnel, separated from other patients in areas of forced proximity such as hallways and elevators, and triaged in a secure single-patient room with a closed door (ideally at negative pressure relative to the surrounding areas).

If the patient has traveled to an area of outbreak, reports exposure to travelers who have visited high-risk areas, has had contact with individuals who tested positive for COVID-19, or exhibits any clinical symptoms of COVID-19 (fever, dry cough, fatigue, etc.), her care management should adhere to standing hospital emergency protocols. Following consultation with the assigned community obstetrician, the Ob hospitalist and hospital staff should contact their local/state health departments immediately for all cases of patients who show symptoms to determine if the patient meets requirements for a person under investigation (PUI) for COVID-19. The state/local health department will work with clinicians to collect, store, and ship clinical specimens appropriately. Very ill patients may need to be treated in an intensive care setting where respiratory status can be closely monitored.

At Ob Hospitalist Group, our body of evidence from our large national footprint has informed the development of standard sets of protocols for delivery complications such as preeclampsia and postpartum hemorrhage, as well as a cesarean section reduction toolkit to combat medically unnecessary cesarean sections. OB hospitalists therefore can assist with refining COVID-19 protocols specifically for the L&D setting, using evidence-based data to tailor protocols to address public health emergencies as they evolve.

The second way that Ob hospitalists can support their colleagues is by covering L&D 24/7 so that community obstetricians can focus on other pressing medical needs. From our experience with other outbreaks such as severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and influenza, we anticipate that obstetricians in private practice likely will have their hands full juggling a regular patient load, fielding calls from concerned patients, and caring for infected or ill patients who are being treated in an outpatient setting. Adding to that plate the need to rush to the hospital to clinically assess a patient for COVID-19 or for a delivery only compounds stress and exhaustion. At Ob Hospitalist Group, our hospitalist programs provide coverage and support to community obstetricians until they can arrive at the hospital or when the woman has no assigned obstetrician, reducing the pressure on community obstetricians to rush through their schedules.

Diagnostic and pharmaceutical companies are collaborating with public health officials to expedite diagnostic testing staff, hospital treatment capacity, vaccines, and even early therapies that may help to minimize severity. But right now, as clinicians work to protect their vulnerable patients, a close collaboration between community obstetricians and Ob hospitalists will help to keep patients and health care personnel safe and healthy – a goal that should apply not only to public health crises, but to the provision of maternal care every day.

Dr. Simon is chief medical officer at Ob Hospitalist Group (OBHG), is a board-certified ob.gyn., and former head of the department of obstetrics and gynecology for a U.S. hospital. He has no relevant conflicts of interest or financial disclosures. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

Mammography does not reduce breast cancer deaths in women 75 and older

While more than half of women aged 75 years and older receive annual mammograms, they do not see a reduced risk of death from breast cancer, compared with women who have stopped regular screening, according to a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The lack of benefit is not because older women’s cancer risk is low; a third of breast cancer deaths occur in women diagnosed at or after age 70 years, according to study author Xabier García-Albéniz, MD, PhD, of Harvard University in Boston, and colleagues.

The lack of benefit is not because mammography is less effective in women older than 75 years; indeed, it becomes a better diagnostic tool as women age, said Otis Brawley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, the author of an editorial related to the study. Rather, the lack of benefit is because breast cancer treatment in older women is less successful, he clarified.

Study details

Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues looked at data from 1,058,013 women enrolled in Medicare across the United States during 2000-2008. All subjects were aged 70-84 years and had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, at least one recent mammogram, and no history of breast cancer.

There are little randomized trial data available on mammography and breast cancer deaths for women in their early 70s and none for women older than 75 years. To compensate for this, the researchers aimed to emulate a prospective trial by looking at deaths over an 8-year period for women aged 70 and older who either continued annual screening or stopped it. The investigators conducted separate analyses for women aged 70-74 years and those 75-84 years of age.

Diagnoses of breast cancer were, not surprisingly, higher in the continued-screening group, but this did not translate to serious reductions in death.

In the continued-screening group, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer was 5.5% in women aged 70-74 and 5.8% in women aged 75-84 years. Among women who stopped screening, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer was 3.9% in both age groups.

Among women aged 70-74 years, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death was slightly reduced with continued screening: 2.7 deaths per 1,000 women, compared with 3.7 deaths per 1,000 women for those who stopped screening. The risk difference was –1.0 deaths per 1,000 women, and the hazard ratio was 0.78.

Among women aged 75-84 years, there was no difference in estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death. Women treated under a continued screening protocol had 3.8 deaths per 1,000, while the stop-screening group had 3.7 deaths per 1,000. The risk difference was 0.07 deaths per 1,000 women, and the hazard ratio was 1.00.

Interpreting the results

In the editorial accompanying this study, Dr. Brawley praised its design as “especially useful in breast cancer screening,” as “prospective randomized studies of mammography are not feasible and are perhaps no longer ethical in older women … because mammography is so widely accepted.”

In an interview, Dr. Brawley stressed that the findings do not argue for denying women aged 75 years and older mammography screening. Decisions about screening require a value judgment tailored to each individual patient’s perceived risks and benefits, he said.

In the absence of randomized trial evidence, “the jury will always be out” on the benefits of regular mammography for women 75 and older, Dr. Brawley said. “A clinical trial or a modeling study always tells you about an average person who doesn’t exist,” he added. “I predict that, in the future, we will have more parameters to tell us, ‘this is a person who’s 80 years old who is likely to benefit from screening; this is a person who is 75 years old who is unlikely to benefit.’ ”

And focusing too much on screening, he said, can divert attention from a key driver of breast cancer mortality in older women: inadequate treatment.

In the United States, Dr. Brawley said, “There’s a lot of emphasis on screening but fewer people writing about the fact that nearly 40% of American women get less than optimal treatment once they’re diagnosed.”

Dr. Brawley cited a 2013 modeling study showing that improvements in delivering current treatments would save more women even if screening rates remained unaltered (Cancer. 2013 Jul 15;119[14]:2541-8).

Among women in their 70s and 80s, Dr. Brawley said, some of the barriers to effective breast cancer care aren’t related to treatment efficacy but to travel and other logistical issues that can become more pronounced with age. “Unfortunately, there’s very little research on why, for women in their 70s and 80s, the treatments don’t work as well as they work in women 20 years younger,” he said.

Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues’ study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported financial ties to industry. Dr. Brawley discloses no conflicts of interest related to his editorial.

SOURCE: García-Albéniz X et al. Ann Intern Med 2020. doi: 10.7326/M18-1199.

While more than half of women aged 75 years and older receive annual mammograms, they do not see a reduced risk of death from breast cancer, compared with women who have stopped regular screening, according to a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The lack of benefit is not because older women’s cancer risk is low; a third of breast cancer deaths occur in women diagnosed at or after age 70 years, according to study author Xabier García-Albéniz, MD, PhD, of Harvard University in Boston, and colleagues.

The lack of benefit is not because mammography is less effective in women older than 75 years; indeed, it becomes a better diagnostic tool as women age, said Otis Brawley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, the author of an editorial related to the study. Rather, the lack of benefit is because breast cancer treatment in older women is less successful, he clarified.

Study details

Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues looked at data from 1,058,013 women enrolled in Medicare across the United States during 2000-2008. All subjects were aged 70-84 years and had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, at least one recent mammogram, and no history of breast cancer.

There are little randomized trial data available on mammography and breast cancer deaths for women in their early 70s and none for women older than 75 years. To compensate for this, the researchers aimed to emulate a prospective trial by looking at deaths over an 8-year period for women aged 70 and older who either continued annual screening or stopped it. The investigators conducted separate analyses for women aged 70-74 years and those 75-84 years of age.

Diagnoses of breast cancer were, not surprisingly, higher in the continued-screening group, but this did not translate to serious reductions in death.

In the continued-screening group, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer was 5.5% in women aged 70-74 and 5.8% in women aged 75-84 years. Among women who stopped screening, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer was 3.9% in both age groups.

Among women aged 70-74 years, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death was slightly reduced with continued screening: 2.7 deaths per 1,000 women, compared with 3.7 deaths per 1,000 women for those who stopped screening. The risk difference was –1.0 deaths per 1,000 women, and the hazard ratio was 0.78.

Among women aged 75-84 years, there was no difference in estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death. Women treated under a continued screening protocol had 3.8 deaths per 1,000, while the stop-screening group had 3.7 deaths per 1,000. The risk difference was 0.07 deaths per 1,000 women, and the hazard ratio was 1.00.

Interpreting the results

In the editorial accompanying this study, Dr. Brawley praised its design as “especially useful in breast cancer screening,” as “prospective randomized studies of mammography are not feasible and are perhaps no longer ethical in older women … because mammography is so widely accepted.”

In an interview, Dr. Brawley stressed that the findings do not argue for denying women aged 75 years and older mammography screening. Decisions about screening require a value judgment tailored to each individual patient’s perceived risks and benefits, he said.

In the absence of randomized trial evidence, “the jury will always be out” on the benefits of regular mammography for women 75 and older, Dr. Brawley said. “A clinical trial or a modeling study always tells you about an average person who doesn’t exist,” he added. “I predict that, in the future, we will have more parameters to tell us, ‘this is a person who’s 80 years old who is likely to benefit from screening; this is a person who is 75 years old who is unlikely to benefit.’ ”

And focusing too much on screening, he said, can divert attention from a key driver of breast cancer mortality in older women: inadequate treatment.

In the United States, Dr. Brawley said, “There’s a lot of emphasis on screening but fewer people writing about the fact that nearly 40% of American women get less than optimal treatment once they’re diagnosed.”

Dr. Brawley cited a 2013 modeling study showing that improvements in delivering current treatments would save more women even if screening rates remained unaltered (Cancer. 2013 Jul 15;119[14]:2541-8).

Among women in their 70s and 80s, Dr. Brawley said, some of the barriers to effective breast cancer care aren’t related to treatment efficacy but to travel and other logistical issues that can become more pronounced with age. “Unfortunately, there’s very little research on why, for women in their 70s and 80s, the treatments don’t work as well as they work in women 20 years younger,” he said.

Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues’ study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported financial ties to industry. Dr. Brawley discloses no conflicts of interest related to his editorial.

SOURCE: García-Albéniz X et al. Ann Intern Med 2020. doi: 10.7326/M18-1199.

While more than half of women aged 75 years and older receive annual mammograms, they do not see a reduced risk of death from breast cancer, compared with women who have stopped regular screening, according to a study published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

The lack of benefit is not because older women’s cancer risk is low; a third of breast cancer deaths occur in women diagnosed at or after age 70 years, according to study author Xabier García-Albéniz, MD, PhD, of Harvard University in Boston, and colleagues.

The lack of benefit is not because mammography is less effective in women older than 75 years; indeed, it becomes a better diagnostic tool as women age, said Otis Brawley, MD, of Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, the author of an editorial related to the study. Rather, the lack of benefit is because breast cancer treatment in older women is less successful, he clarified.

Study details

Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues looked at data from 1,058,013 women enrolled in Medicare across the United States during 2000-2008. All subjects were aged 70-84 years and had a life expectancy of at least 10 years, at least one recent mammogram, and no history of breast cancer.

There are little randomized trial data available on mammography and breast cancer deaths for women in their early 70s and none for women older than 75 years. To compensate for this, the researchers aimed to emulate a prospective trial by looking at deaths over an 8-year period for women aged 70 and older who either continued annual screening or stopped it. The investigators conducted separate analyses for women aged 70-74 years and those 75-84 years of age.

Diagnoses of breast cancer were, not surprisingly, higher in the continued-screening group, but this did not translate to serious reductions in death.

In the continued-screening group, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer was 5.5% in women aged 70-74 and 5.8% in women aged 75-84 years. Among women who stopped screening, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer was 3.9% in both age groups.

Among women aged 70-74 years, the estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death was slightly reduced with continued screening: 2.7 deaths per 1,000 women, compared with 3.7 deaths per 1,000 women for those who stopped screening. The risk difference was –1.0 deaths per 1,000 women, and the hazard ratio was 0.78.

Among women aged 75-84 years, there was no difference in estimated 8-year risk for breast cancer death. Women treated under a continued screening protocol had 3.8 deaths per 1,000, while the stop-screening group had 3.7 deaths per 1,000. The risk difference was 0.07 deaths per 1,000 women, and the hazard ratio was 1.00.

Interpreting the results

In the editorial accompanying this study, Dr. Brawley praised its design as “especially useful in breast cancer screening,” as “prospective randomized studies of mammography are not feasible and are perhaps no longer ethical in older women … because mammography is so widely accepted.”

In an interview, Dr. Brawley stressed that the findings do not argue for denying women aged 75 years and older mammography screening. Decisions about screening require a value judgment tailored to each individual patient’s perceived risks and benefits, he said.

In the absence of randomized trial evidence, “the jury will always be out” on the benefits of regular mammography for women 75 and older, Dr. Brawley said. “A clinical trial or a modeling study always tells you about an average person who doesn’t exist,” he added. “I predict that, in the future, we will have more parameters to tell us, ‘this is a person who’s 80 years old who is likely to benefit from screening; this is a person who is 75 years old who is unlikely to benefit.’ ”

And focusing too much on screening, he said, can divert attention from a key driver of breast cancer mortality in older women: inadequate treatment.

In the United States, Dr. Brawley said, “There’s a lot of emphasis on screening but fewer people writing about the fact that nearly 40% of American women get less than optimal treatment once they’re diagnosed.”

Dr. Brawley cited a 2013 modeling study showing that improvements in delivering current treatments would save more women even if screening rates remained unaltered (Cancer. 2013 Jul 15;119[14]:2541-8).

Among women in their 70s and 80s, Dr. Brawley said, some of the barriers to effective breast cancer care aren’t related to treatment efficacy but to travel and other logistical issues that can become more pronounced with age. “Unfortunately, there’s very little research on why, for women in their 70s and 80s, the treatments don’t work as well as they work in women 20 years younger,” he said.

Dr. García-Albéniz and colleagues’ study was funded by the National Institutes of Health. One coauthor reported financial ties to industry. Dr. Brawley discloses no conflicts of interest related to his editorial.

SOURCE: García-Albéniz X et al. Ann Intern Med 2020. doi: 10.7326/M18-1199.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

ERAS protocol for cesarean delivery reduces opioid usage

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for cesarean delivery decreased postoperative opioid usage by 62% in one health care organization, researchers reported at the Pregnancy Meeting. The protocol incorporates a stepwise approach to pain control with no scheduled postoperative opioids.

Abington Jefferson Health, which includes two hospitals in Pennsylvania, implemented an ERAS pathway for all cesarean deliveries in October 2018. Kathryn Ruymann, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Dr. Ruymann is an obstetrics and gynecology resident at Abington Jefferson Health.

Prior to the ERAS protocol, 99%-100% of patients took an opioid during the postoperative period. “With ERAS, 26% of patients never took an opioid during the postop period,” Dr. Ruymann and her associates reported. “Pain scores decreased with ERAS for postoperative days 1-3 and remained unchanged on day 4.”

One in 300 opioid-naive patients who receives opioids after cesarean delivery becomes a persistent user, one study has shown (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep; 215(3):353.e1-18). “ERAS pathways integrate evidence-based interventions before, during, and after surgery to optimize outcomes, specifically to decrease postoperative opioid use,” the researchers said.

While other surgical fields have adopted ERAS pathways, more research is needed in obstetrics, said Dr. Ruymann. More than 4,500 women deliver at Abington Jefferson Health each year, and about a third undergo cesarean deliveries.

The organization’s ERAS pathway incorporates preoperative education, fasting guidelines, and intraoperative analgesia, nausea prophylaxis, and antimicrobial therapy. Under the new protocol, postoperative analgesia includes scheduled administration of nonopioid medications, including celecoxib and acetaminophen. In addition, patients may take 5-10 mg of oxycodone orally every 4 hours as needed, and hydromorphone 0.4 mg IV as needed may be used for refractory pain. In addition, patients should resume eating as soon as tolerated and be out of bed within 4 hours after surgery, according to the protocol. Postoperative management of pruritus and instructions on how to wean off opioids at home are among the other elements of the enhanced recovery plan.

To examine postoperative opioid usage before and after implementation of the ERAS pathway, the investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of 316 women who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months before the start of the ERAS pathway and 267 who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months after. The researchers used an application developed in Qlik Sense, a data analytics platform, to calculate opioid usage.

Mean postoperative opioid use decreased by 62%. The reduction in opioid use remained 8 months after starting the ERAS pathway.

“An ERAS pathway for [cesarean delivery] decreases postoperative opioid usage by integrating a multimodal stepwise approach to pain control and recovery,” the researchers said. “Standardized order sets and departmentwide education were crucial in the success of ERAS. Additional research is needed to evaluate the impact of unique components of ERAS in order to optimize this pathway.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ruymann K et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S212, Abstract 315.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for cesarean delivery decreased postoperative opioid usage by 62% in one health care organization, researchers reported at the Pregnancy Meeting. The protocol incorporates a stepwise approach to pain control with no scheduled postoperative opioids.

Abington Jefferson Health, which includes two hospitals in Pennsylvania, implemented an ERAS pathway for all cesarean deliveries in October 2018. Kathryn Ruymann, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Dr. Ruymann is an obstetrics and gynecology resident at Abington Jefferson Health.

Prior to the ERAS protocol, 99%-100% of patients took an opioid during the postoperative period. “With ERAS, 26% of patients never took an opioid during the postop period,” Dr. Ruymann and her associates reported. “Pain scores decreased with ERAS for postoperative days 1-3 and remained unchanged on day 4.”

One in 300 opioid-naive patients who receives opioids after cesarean delivery becomes a persistent user, one study has shown (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep; 215(3):353.e1-18). “ERAS pathways integrate evidence-based interventions before, during, and after surgery to optimize outcomes, specifically to decrease postoperative opioid use,” the researchers said.

While other surgical fields have adopted ERAS pathways, more research is needed in obstetrics, said Dr. Ruymann. More than 4,500 women deliver at Abington Jefferson Health each year, and about a third undergo cesarean deliveries.

The organization’s ERAS pathway incorporates preoperative education, fasting guidelines, and intraoperative analgesia, nausea prophylaxis, and antimicrobial therapy. Under the new protocol, postoperative analgesia includes scheduled administration of nonopioid medications, including celecoxib and acetaminophen. In addition, patients may take 5-10 mg of oxycodone orally every 4 hours as needed, and hydromorphone 0.4 mg IV as needed may be used for refractory pain. In addition, patients should resume eating as soon as tolerated and be out of bed within 4 hours after surgery, according to the protocol. Postoperative management of pruritus and instructions on how to wean off opioids at home are among the other elements of the enhanced recovery plan.

To examine postoperative opioid usage before and after implementation of the ERAS pathway, the investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of 316 women who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months before the start of the ERAS pathway and 267 who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months after. The researchers used an application developed in Qlik Sense, a data analytics platform, to calculate opioid usage.

Mean postoperative opioid use decreased by 62%. The reduction in opioid use remained 8 months after starting the ERAS pathway.

“An ERAS pathway for [cesarean delivery] decreases postoperative opioid usage by integrating a multimodal stepwise approach to pain control and recovery,” the researchers said. “Standardized order sets and departmentwide education were crucial in the success of ERAS. Additional research is needed to evaluate the impact of unique components of ERAS in order to optimize this pathway.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ruymann K et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S212, Abstract 315.

GRAPEVINE, TEX. – An enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) pathway for cesarean delivery decreased postoperative opioid usage by 62% in one health care organization, researchers reported at the Pregnancy Meeting. The protocol incorporates a stepwise approach to pain control with no scheduled postoperative opioids.

Abington Jefferson Health, which includes two hospitals in Pennsylvania, implemented an ERAS pathway for all cesarean deliveries in October 2018. Kathryn Ruymann, MD, said at the meeting sponsored by the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Dr. Ruymann is an obstetrics and gynecology resident at Abington Jefferson Health.

Prior to the ERAS protocol, 99%-100% of patients took an opioid during the postoperative period. “With ERAS, 26% of patients never took an opioid during the postop period,” Dr. Ruymann and her associates reported. “Pain scores decreased with ERAS for postoperative days 1-3 and remained unchanged on day 4.”

One in 300 opioid-naive patients who receives opioids after cesarean delivery becomes a persistent user, one study has shown (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Sep; 215(3):353.e1-18). “ERAS pathways integrate evidence-based interventions before, during, and after surgery to optimize outcomes, specifically to decrease postoperative opioid use,” the researchers said.

While other surgical fields have adopted ERAS pathways, more research is needed in obstetrics, said Dr. Ruymann. More than 4,500 women deliver at Abington Jefferson Health each year, and about a third undergo cesarean deliveries.

The organization’s ERAS pathway incorporates preoperative education, fasting guidelines, and intraoperative analgesia, nausea prophylaxis, and antimicrobial therapy. Under the new protocol, postoperative analgesia includes scheduled administration of nonopioid medications, including celecoxib and acetaminophen. In addition, patients may take 5-10 mg of oxycodone orally every 4 hours as needed, and hydromorphone 0.4 mg IV as needed may be used for refractory pain. In addition, patients should resume eating as soon as tolerated and be out of bed within 4 hours after surgery, according to the protocol. Postoperative management of pruritus and instructions on how to wean off opioids at home are among the other elements of the enhanced recovery plan.

To examine postoperative opioid usage before and after implementation of the ERAS pathway, the investigators conducted a retrospective cohort study of 316 women who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months before the start of the ERAS pathway and 267 who underwent cesarean delivery 3 months after. The researchers used an application developed in Qlik Sense, a data analytics platform, to calculate opioid usage.

Mean postoperative opioid use decreased by 62%. The reduction in opioid use remained 8 months after starting the ERAS pathway.

“An ERAS pathway for [cesarean delivery] decreases postoperative opioid usage by integrating a multimodal stepwise approach to pain control and recovery,” the researchers said. “Standardized order sets and departmentwide education were crucial in the success of ERAS. Additional research is needed to evaluate the impact of unique components of ERAS in order to optimize this pathway.”

The researchers had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Ruymann K et al. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 Jan;222(1):S212, Abstract 315.

REPORTING FROM THE PREGNANCY MEETING

Refining your approach to hypothyroidism treatment

CASE

A 38-year-old woman presents for a routine physical. Other than urgent care visits for 1 episode of influenza and 2 upper respiratory illnesses, she has not seen a physician for a physical in 5 years. She denies any significant medical history. She takes naproxen occasionally for chronic right knee pain. She does not use tobacco or alcohol. Recently, she has started using a meal replacement shake at lunchtime for weight management. She performs aerobic exercise 30 to 40 minutes per day, 5 days per week. Her family history is significant for type 2 diabetes mellitus, arthritis, heart disease, and hyperlipidemia on her mother’s side. She is single, is not currently sexually active, works as a pharmacy technician, and has no children. A high-risk human papillomavirus test was normal 4 years ago.

A review of systems is notable for a 20-pound weight gain over the past year, worsening heartburn over the past 2 weeks, and chronic knee pain, which is greater in the right knee than the left. She denies weakness, fatigue, nausea, diarrhea, constipation, or abdominal pain. Vital signs reveal a blood pressure of 146/88 mm Hg, a heart rate of 63 bpm, a temperature of 98°F (36.7°C), a respiratory rate of 16, a height of 5’7’’ (1.7 m), a weight of 217 lbs (98.4 kg), and a peripheral capillary oxygen saturation (SpO2) of 99% on room air. The physical exam reveals a body mass index (BMI) of 34, warm dry skin, and coarse brittle hair.

Lab results reveal a thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 11.17 mIU/L (reference range, 0.45-4.5 mIU/L) and a free thyroxine (T4) of 0.58 ng/dL (reference range, 0.8-2.8 ng/dL). A basic metabolic panel and hemoglobin A1C level are normal.

What would you recommend?

In the United States, the prevalence of overt hypothyroidism (defined as a TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L and a low free T4) among people ≥ 12 years of age was estimated at 0.3% based on National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999-2002.1 Subclinical hypothyroidism (TSH level > 4.5 mIU/L but < 10 mIU/L and a normal T4 level) is even more common, with an estimated prevalence of 3.4%.1 Hypothyroidism is more common in females and occurs more frequently in Caucasian Americans and Mexican Americans than in African Americans.1

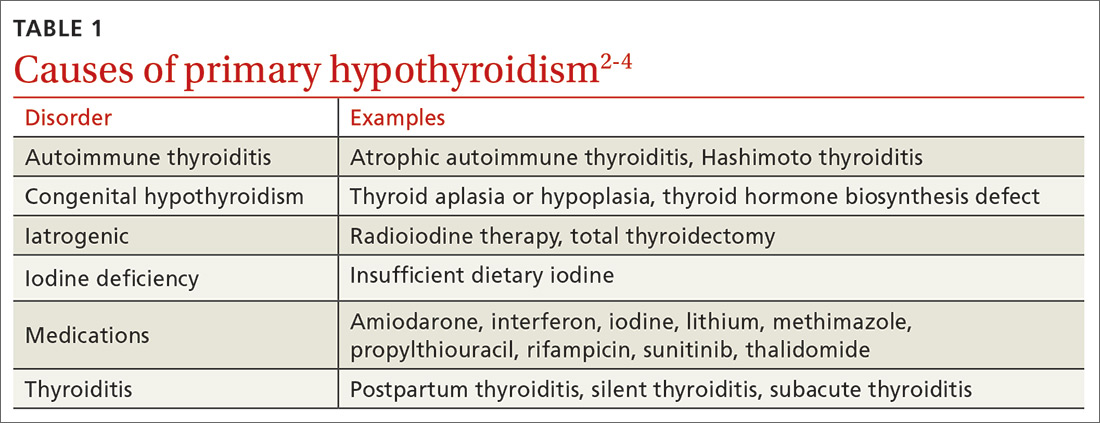

The most common etiologies of hypothyroidism include autoimmune thyroiditis (eg, Hashimoto thyroiditis, atrophic autoimmune thyroiditis) and iatrogenic causes (eg, after radioactive iodine ablation or thyroidectomy) (TABLE 1).2-4

Initiating thyroid hormone replacement

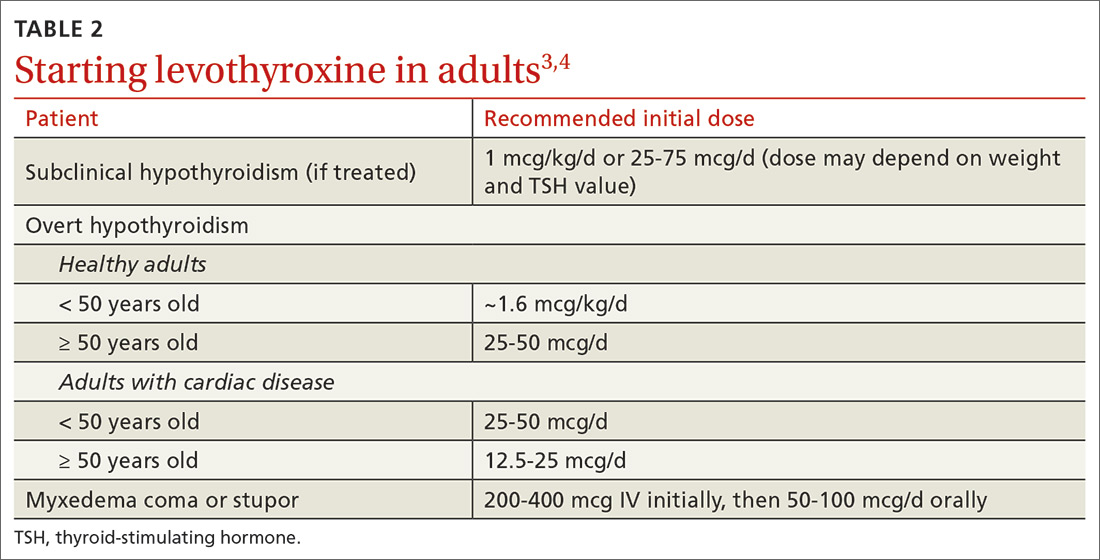

Factors to consider when starting a patient on thyroid hormone replacement include age, weight, symptom severity, TSH level, goal TSH value, adverse effects from thyroid supplements, history of cardiac disease, and, for women of child-bearing age, the desire for pregnancy vs the use of contraceptives. Most adult patients < 50 years with overt hypothyroidism can begin a weight-based dose of levothyroxine: ~1.6 mcg/kg/d (based on ideal body weight).3

Continue to: For adults with cardiac disease...

For adults with cardiac disease, the risk of over-replacement limits initial dosing to 25 to 50 mcg/d for patients < 50 years (12.5-25 mcg/d; ≥ 50 years).3 For adults with subclinical hypothyroidism, it is reasonable to begin therapy at a lower daily dose (eg, 25-75 mcg/d) depending on baseline TSH level, symptoms (the patient may be asymptomatic), and the presence of cardiac disease (TABLE 23,4). Consider treatment in patients with subclinical hypothyroidism particularly when patients have a goiter or dyslipidemia and in women contemplating pregnancy in the near future. Elderly patients may require a dose 20% to 25% lower than younger adults because of decreased body mass.3

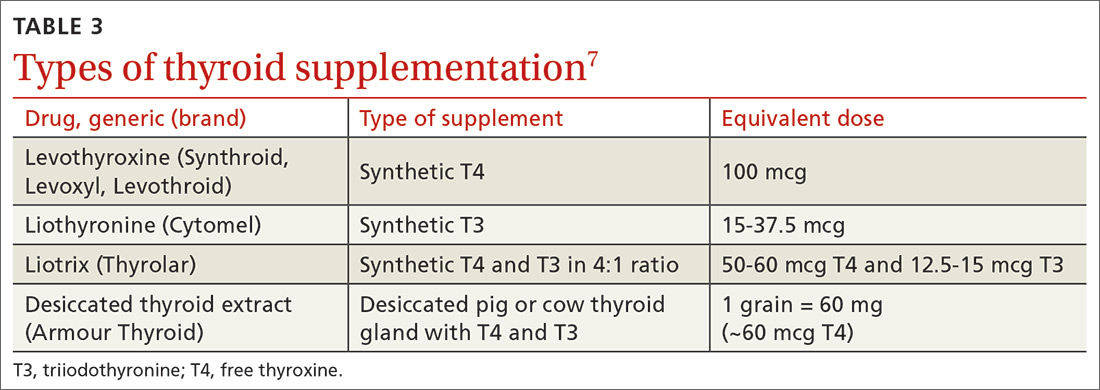

Levothyroxine is considered first-line therapy for hypothyroidism because of its low cost, dose consistency, low risk of allergic reactions, and potential to cause fewer cardiac adverse effects than triiodothyronine (T3) products such as desiccated thyroid extract.5 Although data have not shown an absolute increase in cardiovascular adverse effects, T3 products have a higher T3 vs T4 ratio, giving them a theoretically increased risk.5,6 Desiccated thyroid extract also has been associated with allergic reactions.5

Use of liothyronine alone or in combination with levothyroxine lacks evidence and guideline support.4 Furthermore, it is dosed twice daily, which makes it less convenient, and concerns still exist that there may be an increase in cardiovascular adverse effects.4,6 See TABLE 37 for a summary of available products and their equivalent doses.

Maintaining patients on therapy

The maintenance phase begins once hypothyroidism is diagnosed and treatment is initiated. This phase includes regular monitoring with laboratory studies, office visits, and as-needed adjustments in hormone replacement dosing. The frequency at which all of these occur is variable and based on a number of factors including the patient’s other medical conditions, use of other medications including over-the-counter agents, the patient’s age, weight changes, and pregnancy status.3,4,8 In general, dosage adjustments of 12.5 to 25 mcg can be made at 6- to 8-week intervals based on repeat TSH measurements, patient symptoms, and comorbidities.3

Once a patient is symptomatically stable and laboratory values have normalized, the recommended frequency of laboratory evaluation and office visits is every 12 months, barring significant changes in any of the factors mentioned above. At each visit, physicians should perform medication (including supplements) reconciliation and discuss any health condition updates. Changes to the therapy plan, including frequency or timing of laboratory tests, may be necessary if patients begin taking medications that alter the absorption or function of levothyroxine (eg, steroids).

Continue to: To maximize absorption...

To maximize absorption, providers should review with patients the optimal way to take thyroid hormones. Levothyroxine is approximately 70% to 80% absorbed under ideal conditions, which means taking it in the morning at least 30 to 60 minutes before eating or 3 to 4 hours after the last meal of the day.3,9-13 Of note, TSH levels may increase slightly in patients taking proton pump inhibitors, but this does not usually require a dose increase of thyroid hormone.11 Given that some supplements, particularly iron and calcium, can interfere with absorption, it is recommended to maintain a 3- to 4-hour gap between taking those supplements and taking levothyroxine.12-14 For those patients unable or unwilling to adhere to these recommendations, an increase in levothyroxine dose may be required in order to compensate for the decreased absorption.

Don’t adjust hormone therapy based on clinical presentation alone. While clinical symptoms are important, it is not recommended to adjust hormone therapy based solely on clinical presentation. Common hypothyroid symptoms of dry skin, edema, weight gain, and fatigue may be caused by other medical conditions. While indices including Achilles reflex time and basal metabolic rate have shown some correlation to thyroid dysfunction, there has been limited evidence to show that longitudinal index changes reflect subtle changes in thyroid hormone levels.3

The most recent guidelines from the American Thyroid Association recommend that, “Symptoms should be followed, but considered in the context of serum thyrotropin values, relevant comorbidities, and other potential causes.”3

Special populations/circumstances to keep in mind

Malabsorption conditions. When a higher than expected weight-based dose of levothyroxine is required, physicians should review administration timing, adherence, and comorbid medical conditions that can affect absorption.

Several studies, for example, have demonstrated the impact of Helicobacter pylori gastritis on levothyroxine absorption and subsequent TSH levels.15-17 In one nonrandomized prospective study, patients with H pylori and hypothyroidism who were previously thought to be unresponsive to levothyroxine therapy had a decrease in average TSH level from 30.5 mIU/L to 4.2 mIU/L after H pylori was eradicated.15 Autoimmune atrophic gastritis and celiac disease, both of which are more common in those with other autoimmune diseases, are also associated with the need for higher than expected levothyroxine doses.17,18

Continue to: A history of gastric bypass surgery...