User login

Hydroxychloroquine prevents congenital heart block recurrence in anti-Ro pregnancies

ATLANTA – Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 400 mg/day starting by pregnancy week 10 reduces recurrence of congenital heart block in infants born to women with anti-Ro antibodies, according to an open-label, prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Among antibody-positive women who had a previous pregnancy complicated by congenital heart block (CHB), the regimen reduced recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy from the expected historical rate of 18% to 7.4%, a more than 50% drop. “Given the potential benefit of hydroxychloroquine” (HCQ) and its relative safety during pregnancy, “testing all pregnancies for anti-Ro antibodies, regardless of maternal health, should be considered,” concluded investigators led by rheumatologist Peter Izmirly, MD, associate professor of medicine at New York (N.Y.) University.

About 40% of women with systemic lupus erythematosus and nearly 100% of women with Sjögren’s syndrome, as well as about 1% of women in the general population, have anti-Ro antibodies. They can be present in completely asymptomatic women, which is why the authors called for general screening. Indeed, half of the women in the trial had no or only mild, undifferentiated rheumatic symptoms. Often, “women who carry anti-Ro antibodies have no idea they have them” until they have a child with CHB and are tested, Dr. Izmirly said.

The antibodies cross the placenta and interfere with the normal development of the AV node; about 18% of infants die and most of the rest require lifelong pacing. The risk of CHB in antibody-positive women is about 2%, but once a child is born with the condition, the risk climbs to about 18% in subsequent pregnancies.

Years ago, Dr. Izmirly and his colleagues had a hunch that HCQ might help because it disrupts the toll-like receptor signaling involved in the disease process. A database review he led added weight to the idea, finding that among 257 anti-Ro positive pregnancies, the rate of CHB was 7.5% among the 40 women who happened to take HCQ, versus 21.2% among the 217 who did not. “We wanted to see if we could replicate that prospectively,” he said.

The Preventive Approach to Congenital Heart Block with Hydroxychloroquine (PATCH) trial enrolled 54 antibody positive women with a previous CHB pregnancy. They were started on 400 mg/day HCQ by gestation week 10.

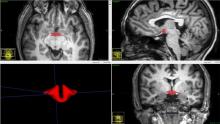

There were four cases of second- or third-degree CHB among the women (7.4%, P = 0.02), all detected by fetal echocardiogram around week 20.

Nine of the women were treated with IVIG and/or dexamethasone for lupus flares or fetal heart issues other than advanced block, which confounded the results. To analyze the effect in a purely HCQ cohort, the team recruited an additional nine women not treated with any other medication during pregnancy, one of whose fetus developed third-degree heart block.

In total, 5 of 63 pregnancies (7.9%) resulted in advanced block. Among the 54 women exposed only to HCQ, the rate of second- or third-degree block was again 7.4% (4 of 54, P = .02). HCQ compliance, assessed by maternal blood levels above 200 ng/mL at least once, was 98%, and cord blood confirmed fetal exposure to HCQ.

Once detected, CHB was treated with dexamethasone or IVIG. One case progressed to cardiomyopathy, and the pregnancy was terminated. Another child required pacing after birth. Other children reverted to normal sinus rhythm but had intermittent second-degree block at age 2.

Overall, “the safety in this study was excellent,” said rheumatologist and senior investigator Jill Buyon, MD, director of the division of rheumatology at New York University.

The complications – nine births before 37 weeks, one infant small for gestational age – were not unexpected in a rheumatic population. “We were very nervous about Plaquenil cardiomyopathy” in the pregnancy that was terminated, but there was no evidence of it on histology.

The children will have ocular optical coherence tomography at age 5 to check for retinal toxicity; the 12 who have been tested so far show no obvious signs. Dr. Izmirly said he doesn’t expect to see any problems. “We are just being super cautious.”

The audience had questions about why the trial didn’t have a placebo arm. He explained that CHB is a rare event – one in 15,000 pregnancies – and it took 8 years just to adequately power the single-arm study; recruiting more than 100 additional women for a placebo-controlled trial wasn’t practical.

Also, “there was no way” women were going to be randomized to placebo when HCQ seemed so promising; 35% of the enrollees had already lost a child to CHB. “Everyone wanted the drug,” Dr. Izmirly said.

The majority of women were white, and about half met criteria for lupus and/or Sjögren’s. Anti-Ro levels remained above 1,000 EU throughout pregnancy. Women were excluded if they were taking high-dose prednisone or any dose of fluorinated corticosteroids at baseline.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Izmirly P et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 1761.

ATLANTA – Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 400 mg/day starting by pregnancy week 10 reduces recurrence of congenital heart block in infants born to women with anti-Ro antibodies, according to an open-label, prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Among antibody-positive women who had a previous pregnancy complicated by congenital heart block (CHB), the regimen reduced recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy from the expected historical rate of 18% to 7.4%, a more than 50% drop. “Given the potential benefit of hydroxychloroquine” (HCQ) and its relative safety during pregnancy, “testing all pregnancies for anti-Ro antibodies, regardless of maternal health, should be considered,” concluded investigators led by rheumatologist Peter Izmirly, MD, associate professor of medicine at New York (N.Y.) University.

About 40% of women with systemic lupus erythematosus and nearly 100% of women with Sjögren’s syndrome, as well as about 1% of women in the general population, have anti-Ro antibodies. They can be present in completely asymptomatic women, which is why the authors called for general screening. Indeed, half of the women in the trial had no or only mild, undifferentiated rheumatic symptoms. Often, “women who carry anti-Ro antibodies have no idea they have them” until they have a child with CHB and are tested, Dr. Izmirly said.

The antibodies cross the placenta and interfere with the normal development of the AV node; about 18% of infants die and most of the rest require lifelong pacing. The risk of CHB in antibody-positive women is about 2%, but once a child is born with the condition, the risk climbs to about 18% in subsequent pregnancies.

Years ago, Dr. Izmirly and his colleagues had a hunch that HCQ might help because it disrupts the toll-like receptor signaling involved in the disease process. A database review he led added weight to the idea, finding that among 257 anti-Ro positive pregnancies, the rate of CHB was 7.5% among the 40 women who happened to take HCQ, versus 21.2% among the 217 who did not. “We wanted to see if we could replicate that prospectively,” he said.

The Preventive Approach to Congenital Heart Block with Hydroxychloroquine (PATCH) trial enrolled 54 antibody positive women with a previous CHB pregnancy. They were started on 400 mg/day HCQ by gestation week 10.

There were four cases of second- or third-degree CHB among the women (7.4%, P = 0.02), all detected by fetal echocardiogram around week 20.

Nine of the women were treated with IVIG and/or dexamethasone for lupus flares or fetal heart issues other than advanced block, which confounded the results. To analyze the effect in a purely HCQ cohort, the team recruited an additional nine women not treated with any other medication during pregnancy, one of whose fetus developed third-degree heart block.

In total, 5 of 63 pregnancies (7.9%) resulted in advanced block. Among the 54 women exposed only to HCQ, the rate of second- or third-degree block was again 7.4% (4 of 54, P = .02). HCQ compliance, assessed by maternal blood levels above 200 ng/mL at least once, was 98%, and cord blood confirmed fetal exposure to HCQ.

Once detected, CHB was treated with dexamethasone or IVIG. One case progressed to cardiomyopathy, and the pregnancy was terminated. Another child required pacing after birth. Other children reverted to normal sinus rhythm but had intermittent second-degree block at age 2.

Overall, “the safety in this study was excellent,” said rheumatologist and senior investigator Jill Buyon, MD, director of the division of rheumatology at New York University.

The complications – nine births before 37 weeks, one infant small for gestational age – were not unexpected in a rheumatic population. “We were very nervous about Plaquenil cardiomyopathy” in the pregnancy that was terminated, but there was no evidence of it on histology.

The children will have ocular optical coherence tomography at age 5 to check for retinal toxicity; the 12 who have been tested so far show no obvious signs. Dr. Izmirly said he doesn’t expect to see any problems. “We are just being super cautious.”

The audience had questions about why the trial didn’t have a placebo arm. He explained that CHB is a rare event – one in 15,000 pregnancies – and it took 8 years just to adequately power the single-arm study; recruiting more than 100 additional women for a placebo-controlled trial wasn’t practical.

Also, “there was no way” women were going to be randomized to placebo when HCQ seemed so promising; 35% of the enrollees had already lost a child to CHB. “Everyone wanted the drug,” Dr. Izmirly said.

The majority of women were white, and about half met criteria for lupus and/or Sjögren’s. Anti-Ro levels remained above 1,000 EU throughout pregnancy. Women were excluded if they were taking high-dose prednisone or any dose of fluorinated corticosteroids at baseline.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Izmirly P et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 1761.

ATLANTA – Hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) 400 mg/day starting by pregnancy week 10 reduces recurrence of congenital heart block in infants born to women with anti-Ro antibodies, according to an open-label, prospective study presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology.

Among antibody-positive women who had a previous pregnancy complicated by congenital heart block (CHB), the regimen reduced recurrence in a subsequent pregnancy from the expected historical rate of 18% to 7.4%, a more than 50% drop. “Given the potential benefit of hydroxychloroquine” (HCQ) and its relative safety during pregnancy, “testing all pregnancies for anti-Ro antibodies, regardless of maternal health, should be considered,” concluded investigators led by rheumatologist Peter Izmirly, MD, associate professor of medicine at New York (N.Y.) University.

About 40% of women with systemic lupus erythematosus and nearly 100% of women with Sjögren’s syndrome, as well as about 1% of women in the general population, have anti-Ro antibodies. They can be present in completely asymptomatic women, which is why the authors called for general screening. Indeed, half of the women in the trial had no or only mild, undifferentiated rheumatic symptoms. Often, “women who carry anti-Ro antibodies have no idea they have them” until they have a child with CHB and are tested, Dr. Izmirly said.

The antibodies cross the placenta and interfere with the normal development of the AV node; about 18% of infants die and most of the rest require lifelong pacing. The risk of CHB in antibody-positive women is about 2%, but once a child is born with the condition, the risk climbs to about 18% in subsequent pregnancies.

Years ago, Dr. Izmirly and his colleagues had a hunch that HCQ might help because it disrupts the toll-like receptor signaling involved in the disease process. A database review he led added weight to the idea, finding that among 257 anti-Ro positive pregnancies, the rate of CHB was 7.5% among the 40 women who happened to take HCQ, versus 21.2% among the 217 who did not. “We wanted to see if we could replicate that prospectively,” he said.

The Preventive Approach to Congenital Heart Block with Hydroxychloroquine (PATCH) trial enrolled 54 antibody positive women with a previous CHB pregnancy. They were started on 400 mg/day HCQ by gestation week 10.

There were four cases of second- or third-degree CHB among the women (7.4%, P = 0.02), all detected by fetal echocardiogram around week 20.

Nine of the women were treated with IVIG and/or dexamethasone for lupus flares or fetal heart issues other than advanced block, which confounded the results. To analyze the effect in a purely HCQ cohort, the team recruited an additional nine women not treated with any other medication during pregnancy, one of whose fetus developed third-degree heart block.

In total, 5 of 63 pregnancies (7.9%) resulted in advanced block. Among the 54 women exposed only to HCQ, the rate of second- or third-degree block was again 7.4% (4 of 54, P = .02). HCQ compliance, assessed by maternal blood levels above 200 ng/mL at least once, was 98%, and cord blood confirmed fetal exposure to HCQ.

Once detected, CHB was treated with dexamethasone or IVIG. One case progressed to cardiomyopathy, and the pregnancy was terminated. Another child required pacing after birth. Other children reverted to normal sinus rhythm but had intermittent second-degree block at age 2.

Overall, “the safety in this study was excellent,” said rheumatologist and senior investigator Jill Buyon, MD, director of the division of rheumatology at New York University.

The complications – nine births before 37 weeks, one infant small for gestational age – were not unexpected in a rheumatic population. “We were very nervous about Plaquenil cardiomyopathy” in the pregnancy that was terminated, but there was no evidence of it on histology.

The children will have ocular optical coherence tomography at age 5 to check for retinal toxicity; the 12 who have been tested so far show no obvious signs. Dr. Izmirly said he doesn’t expect to see any problems. “We are just being super cautious.”

The audience had questions about why the trial didn’t have a placebo arm. He explained that CHB is a rare event – one in 15,000 pregnancies – and it took 8 years just to adequately power the single-arm study; recruiting more than 100 additional women for a placebo-controlled trial wasn’t practical.

Also, “there was no way” women were going to be randomized to placebo when HCQ seemed so promising; 35% of the enrollees had already lost a child to CHB. “Everyone wanted the drug,” Dr. Izmirly said.

The majority of women were white, and about half met criteria for lupus and/or Sjögren’s. Anti-Ro levels remained above 1,000 EU throughout pregnancy. Women were excluded if they were taking high-dose prednisone or any dose of fluorinated corticosteroids at baseline.

The National Institutes of Health funded the work. The investigators had no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Izmirly P et al. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2019;71(suppl 10). Abstract 1761.

REPORTING FROM ACR 2019

Obstetrical care in crisis

For the last 25 years I have had the privilege of caring for a rural community, practicing full-scope family medicine including obstetrics with cesarean sections. I have had a deeply rewarding career, and delivering babies and watching them grow up has been one of the most gratifying parts of my work.

My concern is that, as the number of family physicians who practice maternity care has decreased, the infant and maternal mortality rate in the United States has increased, especially in rural and minority populations. Currently, 5 million women of reproductive age have no access to maternity care.

At the same time 23% of incoming family medicine residents would like to offer maternity care and are trained to do so, but few are able to find a job where this is possible.1 This is unfortunate because family physicians have the training and expertise to provide comprehensive maternity care. Although they have lower rates of cesarean section than ob-gyns, with similar outcomes, family physicians do have surgical skills, including providing cesarean sections, that are often necessary for safe delivery.2,3

In addition, family physicians have the internal medicine and behavioral health background to care for postpartum complications, as well as substance use disorders. Because they also care for children, they see postpartum women when they come in with their children for well-child checks. These visits offer an excellent opportunity to also check on the mother for postpartum depression and other signs of postpartum illness.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data reveal that maternal mortality can be divided into three nearly equal parts: pregnancy, delivery, and post partum. They define delivery as the week of delivery. The 48 hours post delivery accounted for only 12% of overall mortality. This means that even if women travel to metropolitan areas, they are likely to be home when they have fatal complications. The lack of trained and experienced physicians in the communities where women live increases their risks should they have complications. Most maternal fatalities occur when conditions are not recognized in a timely fashion. Some responses require procedural skills such as dilation and curettage (D&C).

As a member of the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, I visited several states to evaluate their rural health systems. We looked at infant mortality by county and found an enormous disparity between counties, largely caused by lack of prenatal services and obstetrical services.

These disparities between counties are getting worse. The United States is losing critical access hospitals at a rapid pace. We have lost 117 critical access hospitals in the last 10 years, with 40 in the last year alone. According to the National Rural Health Association, 4,673 additional facilities – representing more than one-third of rural hospitals in the United States – are vulnerable and could close. The reasons are multiple, but the result has been an erosion of the rural safety net, especially with regard to maternity care.

These hospital closures force women to travel farther distances for maternity care, including cesarean sections, and this contributes to increased maternal and infant mortality.5 In a study from Canada, the complication rates increased substantially as distances increased. Women are more likely to have premature deliveries, deliver on the side of the road, or end up in inappropriate facilities.

The distance from delivery is directly related to outcomes. A study from the early 1990s showed that women did better if they received maternity care from local hospitals and physicians.6 From a family medicine perspective, this makes sense because traveling to a metropolitan area means isolation from family and social networks. Stress increases because pregnant women also are often the primary caregiver of other children and the primary wage earner of the family. Although we are unsure what impact stress has on pregnancy, we do know it does have an effect on greater risk of prematurity and poor outcomes.

Obstetricians provide excellent care, but they are not a panacea. Only half of U.S. counties have adequate ob.gyn. coverage. Moreover, in many of those counties, the ob.gyns. subspecialize in gynecologic surgery and infertility, but don’t provide obstetrical care. Another challenge: ob.gyns. cannot survive financially in smaller communities; our policies must include incentives to recruit and retain them in underserved areas.

Certified nurse midwives also provide excellent care and are an invaluable member of the patient-care team, but again, they cannot be the only solution. Obstetrical emergencies do occur, and mothers need a physician trained in providing on-site medical or surgical care. They also need a hospital with adequate staff to care for emergencies.

In communities large enough to support a multispecialty group, certified medical technicians, family physicians, and ob.gyns. would ideally work alongside each other. In small communities four family physicians can provide a high level of maternity care including surgical deliveries, while supporting themselves with caring for children and elders in clinics, hospitals, and EDs.

It is unconscionable that a country as wealthy as ours would accept rates of maternal and infant mortality that rival and are often worse than developing countries. Although the reasons are many, there is no excuse. Family physicians are an essential part of reversing this trend. We need policies that enable family physicians to help resolve the shortage of maternity care for underserved communities, to address the maternal and infant mortality rate, and to provide maternity care that is part of family medicine’s full scope of practice.

Dr. Cullen is board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a practicing family physician in Valdez, Alaska.

References

1. Am Board Fam Med. 2017 Jul-Aug;30(4):405-6.

2. CMAJ. 2015 Oct 27;187:1125-32.

3. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013 Jul-Aug;26(4):366-72.

4. NRHA Save Rural Hospitals Action Center. www.ruralhealthweb.org/advocate/save-rural-hospitals.

5. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Jun 10;11:147.

6. Am J Public Health. 1990 Jul;80(7):814-8.

For the last 25 years I have had the privilege of caring for a rural community, practicing full-scope family medicine including obstetrics with cesarean sections. I have had a deeply rewarding career, and delivering babies and watching them grow up has been one of the most gratifying parts of my work.

My concern is that, as the number of family physicians who practice maternity care has decreased, the infant and maternal mortality rate in the United States has increased, especially in rural and minority populations. Currently, 5 million women of reproductive age have no access to maternity care.

At the same time 23% of incoming family medicine residents would like to offer maternity care and are trained to do so, but few are able to find a job where this is possible.1 This is unfortunate because family physicians have the training and expertise to provide comprehensive maternity care. Although they have lower rates of cesarean section than ob-gyns, with similar outcomes, family physicians do have surgical skills, including providing cesarean sections, that are often necessary for safe delivery.2,3

In addition, family physicians have the internal medicine and behavioral health background to care for postpartum complications, as well as substance use disorders. Because they also care for children, they see postpartum women when they come in with their children for well-child checks. These visits offer an excellent opportunity to also check on the mother for postpartum depression and other signs of postpartum illness.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data reveal that maternal mortality can be divided into three nearly equal parts: pregnancy, delivery, and post partum. They define delivery as the week of delivery. The 48 hours post delivery accounted for only 12% of overall mortality. This means that even if women travel to metropolitan areas, they are likely to be home when they have fatal complications. The lack of trained and experienced physicians in the communities where women live increases their risks should they have complications. Most maternal fatalities occur when conditions are not recognized in a timely fashion. Some responses require procedural skills such as dilation and curettage (D&C).

As a member of the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, I visited several states to evaluate their rural health systems. We looked at infant mortality by county and found an enormous disparity between counties, largely caused by lack of prenatal services and obstetrical services.

These disparities between counties are getting worse. The United States is losing critical access hospitals at a rapid pace. We have lost 117 critical access hospitals in the last 10 years, with 40 in the last year alone. According to the National Rural Health Association, 4,673 additional facilities – representing more than one-third of rural hospitals in the United States – are vulnerable and could close. The reasons are multiple, but the result has been an erosion of the rural safety net, especially with regard to maternity care.

These hospital closures force women to travel farther distances for maternity care, including cesarean sections, and this contributes to increased maternal and infant mortality.5 In a study from Canada, the complication rates increased substantially as distances increased. Women are more likely to have premature deliveries, deliver on the side of the road, or end up in inappropriate facilities.

The distance from delivery is directly related to outcomes. A study from the early 1990s showed that women did better if they received maternity care from local hospitals and physicians.6 From a family medicine perspective, this makes sense because traveling to a metropolitan area means isolation from family and social networks. Stress increases because pregnant women also are often the primary caregiver of other children and the primary wage earner of the family. Although we are unsure what impact stress has on pregnancy, we do know it does have an effect on greater risk of prematurity and poor outcomes.

Obstetricians provide excellent care, but they are not a panacea. Only half of U.S. counties have adequate ob.gyn. coverage. Moreover, in many of those counties, the ob.gyns. subspecialize in gynecologic surgery and infertility, but don’t provide obstetrical care. Another challenge: ob.gyns. cannot survive financially in smaller communities; our policies must include incentives to recruit and retain them in underserved areas.

Certified nurse midwives also provide excellent care and are an invaluable member of the patient-care team, but again, they cannot be the only solution. Obstetrical emergencies do occur, and mothers need a physician trained in providing on-site medical or surgical care. They also need a hospital with adequate staff to care for emergencies.

In communities large enough to support a multispecialty group, certified medical technicians, family physicians, and ob.gyns. would ideally work alongside each other. In small communities four family physicians can provide a high level of maternity care including surgical deliveries, while supporting themselves with caring for children and elders in clinics, hospitals, and EDs.

It is unconscionable that a country as wealthy as ours would accept rates of maternal and infant mortality that rival and are often worse than developing countries. Although the reasons are many, there is no excuse. Family physicians are an essential part of reversing this trend. We need policies that enable family physicians to help resolve the shortage of maternity care for underserved communities, to address the maternal and infant mortality rate, and to provide maternity care that is part of family medicine’s full scope of practice.

Dr. Cullen is board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a practicing family physician in Valdez, Alaska.

References

1. Am Board Fam Med. 2017 Jul-Aug;30(4):405-6.

2. CMAJ. 2015 Oct 27;187:1125-32.

3. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013 Jul-Aug;26(4):366-72.

4. NRHA Save Rural Hospitals Action Center. www.ruralhealthweb.org/advocate/save-rural-hospitals.

5. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Jun 10;11:147.

6. Am J Public Health. 1990 Jul;80(7):814-8.

For the last 25 years I have had the privilege of caring for a rural community, practicing full-scope family medicine including obstetrics with cesarean sections. I have had a deeply rewarding career, and delivering babies and watching them grow up has been one of the most gratifying parts of my work.

My concern is that, as the number of family physicians who practice maternity care has decreased, the infant and maternal mortality rate in the United States has increased, especially in rural and minority populations. Currently, 5 million women of reproductive age have no access to maternity care.

At the same time 23% of incoming family medicine residents would like to offer maternity care and are trained to do so, but few are able to find a job where this is possible.1 This is unfortunate because family physicians have the training and expertise to provide comprehensive maternity care. Although they have lower rates of cesarean section than ob-gyns, with similar outcomes, family physicians do have surgical skills, including providing cesarean sections, that are often necessary for safe delivery.2,3

In addition, family physicians have the internal medicine and behavioral health background to care for postpartum complications, as well as substance use disorders. Because they also care for children, they see postpartum women when they come in with their children for well-child checks. These visits offer an excellent opportunity to also check on the mother for postpartum depression and other signs of postpartum illness.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data reveal that maternal mortality can be divided into three nearly equal parts: pregnancy, delivery, and post partum. They define delivery as the week of delivery. The 48 hours post delivery accounted for only 12% of overall mortality. This means that even if women travel to metropolitan areas, they are likely to be home when they have fatal complications. The lack of trained and experienced physicians in the communities where women live increases their risks should they have complications. Most maternal fatalities occur when conditions are not recognized in a timely fashion. Some responses require procedural skills such as dilation and curettage (D&C).

As a member of the National Advisory Committee on Rural Health and Human Services, I visited several states to evaluate their rural health systems. We looked at infant mortality by county and found an enormous disparity between counties, largely caused by lack of prenatal services and obstetrical services.

These disparities between counties are getting worse. The United States is losing critical access hospitals at a rapid pace. We have lost 117 critical access hospitals in the last 10 years, with 40 in the last year alone. According to the National Rural Health Association, 4,673 additional facilities – representing more than one-third of rural hospitals in the United States – are vulnerable and could close. The reasons are multiple, but the result has been an erosion of the rural safety net, especially with regard to maternity care.

These hospital closures force women to travel farther distances for maternity care, including cesarean sections, and this contributes to increased maternal and infant mortality.5 In a study from Canada, the complication rates increased substantially as distances increased. Women are more likely to have premature deliveries, deliver on the side of the road, or end up in inappropriate facilities.

The distance from delivery is directly related to outcomes. A study from the early 1990s showed that women did better if they received maternity care from local hospitals and physicians.6 From a family medicine perspective, this makes sense because traveling to a metropolitan area means isolation from family and social networks. Stress increases because pregnant women also are often the primary caregiver of other children and the primary wage earner of the family. Although we are unsure what impact stress has on pregnancy, we do know it does have an effect on greater risk of prematurity and poor outcomes.

Obstetricians provide excellent care, but they are not a panacea. Only half of U.S. counties have adequate ob.gyn. coverage. Moreover, in many of those counties, the ob.gyns. subspecialize in gynecologic surgery and infertility, but don’t provide obstetrical care. Another challenge: ob.gyns. cannot survive financially in smaller communities; our policies must include incentives to recruit and retain them in underserved areas.

Certified nurse midwives also provide excellent care and are an invaluable member of the patient-care team, but again, they cannot be the only solution. Obstetrical emergencies do occur, and mothers need a physician trained in providing on-site medical or surgical care. They also need a hospital with adequate staff to care for emergencies.

In communities large enough to support a multispecialty group, certified medical technicians, family physicians, and ob.gyns. would ideally work alongside each other. In small communities four family physicians can provide a high level of maternity care including surgical deliveries, while supporting themselves with caring for children and elders in clinics, hospitals, and EDs.

It is unconscionable that a country as wealthy as ours would accept rates of maternal and infant mortality that rival and are often worse than developing countries. Although the reasons are many, there is no excuse. Family physicians are an essential part of reversing this trend. We need policies that enable family physicians to help resolve the shortage of maternity care for underserved communities, to address the maternal and infant mortality rate, and to provide maternity care that is part of family medicine’s full scope of practice.

Dr. Cullen is board chair of the American Academy of Family Physicians and a practicing family physician in Valdez, Alaska.

References

1. Am Board Fam Med. 2017 Jul-Aug;30(4):405-6.

2. CMAJ. 2015 Oct 27;187:1125-32.

3. J Am Board Fam Med. 2013 Jul-Aug;26(4):366-72.

4. NRHA Save Rural Hospitals Action Center. www.ruralhealthweb.org/advocate/save-rural-hospitals.

5. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011 Jun 10;11:147.

6. Am J Public Health. 1990 Jul;80(7):814-8.

Asthma exacerbation in pregnancy impacts mothers, infants

Women with asthma who suffer asthma exacerbation while pregnant are at increased risk for complications during pregnancy and delivery, and their infants are at increased risk for respiratory problems, according to data from a longitudinal study of 58,524 women with asthma.

“Asthma exacerbation during pregnancy has been found to be associated with adverse perinatal and pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight, small for gestational age, preterm delivery, congenital malformation, preeclampsia, and perinatal mortality,” but previous studies have been small and limited to comparisons of asthmatic and nonasthmatic women, wrote Kawsari Abdullah, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of asthma exacerbation on maternal and fetal outcomes, the researchers analyzed data from the Ontario Asthma Surveillance Information System to identify women with asthma who had at least one pregnancy resulting in a live or still birth between 2006 and 2012.

Overall, significantly more women with exacerbated asthma had preeclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension, compared with asthmatic women who had no exacerbations, at 5% vs. 4% and 7% vs. 5%, respectively (P less than .001), according to the study published in the European Respiratory Journal.

Adverse perinatal outcomes were significantly more likely among babies of mothers with exacerbated asthma, compared with those who had no exacerbations, including low birth weight (7% vs. 5%), small for gestational age (3% vs. 2%), preterm birth (8% vs. 7%), and congenital malformation (6% vs. 5%). All P values were less than .001, except for small for gestational age, which was P = .008.

In addition, significantly more babies of asthmatic women with exacerbated asthma during pregnancy had respiratory problems including asthma and pneumonia, compared with those of asthmatic women who had no exacerbations during pregnancy, at 38% vs. 31% and 24% vs. 22% (P less than .001 for both). The researchers found no significant interactions between maternal age and smoking and asthma exacerbations.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of a validated algorithm for asthma exacerbation, which the researchers defined as five or more visits to a general practice clinician for asthma during pregnancy. Other limitations included the lack of categorizing asthma exacerbation by severity, and the inability to include the potential effects of asthma medication on maternal and fetal outcomes, Dr. Abdullah and colleagues noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and ability to follow babies from birth until 5 years of age, they said.

“Targeting women with asthma during pregnancy and ensuring appropriate asthma management and postpartum follow-up may help to reduce the risk of pregnancy complications, adverse perinatal outcomes, and early childhood respiratory disorders,” they concluded.

This study is important because asthma is a common, potentially serious medical condition that complicates approximately 4%-8% of pregnancies, and one in three women with asthma experience an exacerbation during pregnancy, Iris Krishna, MD, a specialist in maternal/fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“This study is unique in that it uses population-level data to assess the association between an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes,” Dr. Krishna said. “After adjusting for confounders, and consistent with previous studies, study findings suggest an increased risk for women with asthma who have an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy for preeclampsia [odds ratio, 1.3; P less than .001], pregnancy-induced hypertension [OR, 1.17; P less than .05], low-birth-weight infant [OR, 1.14; P less than .05], preterm birth [OR, 1.14; P less than .05], and congenital malformations [OR, 1.21; P less than .001].”

Dr. Krishna also noted the impact on early childhood outcomes. “In this study, children born to women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy had a 23% higher risk of developing asthma before 5 years of age, which is consistent with previous studies. [The] investigators also reported a 12% higher risk of having pneumonia during the first 5 years of life for children born to women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy.”

“Previous studies have suggested children born to mothers with uncontrolled asthma have an increased risk for respiratory infections, but this study is the first to report an association with pneumonia,” she said. This increased risk for childhood respiratory disorders warrants further study.

Consequently, “Women with asthma during pregnancy should have appropriate management to ensure good control to optimize pregnancy outcome,” Dr. Krishna emphasized. “Women who experience asthma exacerbations in pregnancy are at increased risk for preeclampsia, [pregnancy-induced hypertension], low birth weight, and preterm delivery and may require closer monitoring.”

The study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. The researchers and Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Abdullah K et al. Eur Respir J. 2019 Nov 26. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01335-2019.

Women with asthma who suffer asthma exacerbation while pregnant are at increased risk for complications during pregnancy and delivery, and their infants are at increased risk for respiratory problems, according to data from a longitudinal study of 58,524 women with asthma.

“Asthma exacerbation during pregnancy has been found to be associated with adverse perinatal and pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight, small for gestational age, preterm delivery, congenital malformation, preeclampsia, and perinatal mortality,” but previous studies have been small and limited to comparisons of asthmatic and nonasthmatic women, wrote Kawsari Abdullah, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of asthma exacerbation on maternal and fetal outcomes, the researchers analyzed data from the Ontario Asthma Surveillance Information System to identify women with asthma who had at least one pregnancy resulting in a live or still birth between 2006 and 2012.

Overall, significantly more women with exacerbated asthma had preeclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension, compared with asthmatic women who had no exacerbations, at 5% vs. 4% and 7% vs. 5%, respectively (P less than .001), according to the study published in the European Respiratory Journal.

Adverse perinatal outcomes were significantly more likely among babies of mothers with exacerbated asthma, compared with those who had no exacerbations, including low birth weight (7% vs. 5%), small for gestational age (3% vs. 2%), preterm birth (8% vs. 7%), and congenital malformation (6% vs. 5%). All P values were less than .001, except for small for gestational age, which was P = .008.

In addition, significantly more babies of asthmatic women with exacerbated asthma during pregnancy had respiratory problems including asthma and pneumonia, compared with those of asthmatic women who had no exacerbations during pregnancy, at 38% vs. 31% and 24% vs. 22% (P less than .001 for both). The researchers found no significant interactions between maternal age and smoking and asthma exacerbations.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of a validated algorithm for asthma exacerbation, which the researchers defined as five or more visits to a general practice clinician for asthma during pregnancy. Other limitations included the lack of categorizing asthma exacerbation by severity, and the inability to include the potential effects of asthma medication on maternal and fetal outcomes, Dr. Abdullah and colleagues noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and ability to follow babies from birth until 5 years of age, they said.

“Targeting women with asthma during pregnancy and ensuring appropriate asthma management and postpartum follow-up may help to reduce the risk of pregnancy complications, adverse perinatal outcomes, and early childhood respiratory disorders,” they concluded.

This study is important because asthma is a common, potentially serious medical condition that complicates approximately 4%-8% of pregnancies, and one in three women with asthma experience an exacerbation during pregnancy, Iris Krishna, MD, a specialist in maternal/fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“This study is unique in that it uses population-level data to assess the association between an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes,” Dr. Krishna said. “After adjusting for confounders, and consistent with previous studies, study findings suggest an increased risk for women with asthma who have an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy for preeclampsia [odds ratio, 1.3; P less than .001], pregnancy-induced hypertension [OR, 1.17; P less than .05], low-birth-weight infant [OR, 1.14; P less than .05], preterm birth [OR, 1.14; P less than .05], and congenital malformations [OR, 1.21; P less than .001].”

Dr. Krishna also noted the impact on early childhood outcomes. “In this study, children born to women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy had a 23% higher risk of developing asthma before 5 years of age, which is consistent with previous studies. [The] investigators also reported a 12% higher risk of having pneumonia during the first 5 years of life for children born to women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy.”

“Previous studies have suggested children born to mothers with uncontrolled asthma have an increased risk for respiratory infections, but this study is the first to report an association with pneumonia,” she said. This increased risk for childhood respiratory disorders warrants further study.

Consequently, “Women with asthma during pregnancy should have appropriate management to ensure good control to optimize pregnancy outcome,” Dr. Krishna emphasized. “Women who experience asthma exacerbations in pregnancy are at increased risk for preeclampsia, [pregnancy-induced hypertension], low birth weight, and preterm delivery and may require closer monitoring.”

The study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. The researchers and Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Abdullah K et al. Eur Respir J. 2019 Nov 26. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01335-2019.

Women with asthma who suffer asthma exacerbation while pregnant are at increased risk for complications during pregnancy and delivery, and their infants are at increased risk for respiratory problems, according to data from a longitudinal study of 58,524 women with asthma.

“Asthma exacerbation during pregnancy has been found to be associated with adverse perinatal and pregnancy outcomes such as low birth weight, small for gestational age, preterm delivery, congenital malformation, preeclampsia, and perinatal mortality,” but previous studies have been small and limited to comparisons of asthmatic and nonasthmatic women, wrote Kawsari Abdullah, PhD, of Children’s Hospital of Eastern Ontario, Ottawa, and colleagues.

To determine the impact of asthma exacerbation on maternal and fetal outcomes, the researchers analyzed data from the Ontario Asthma Surveillance Information System to identify women with asthma who had at least one pregnancy resulting in a live or still birth between 2006 and 2012.

Overall, significantly more women with exacerbated asthma had preeclampsia or pregnancy-induced hypertension, compared with asthmatic women who had no exacerbations, at 5% vs. 4% and 7% vs. 5%, respectively (P less than .001), according to the study published in the European Respiratory Journal.

Adverse perinatal outcomes were significantly more likely among babies of mothers with exacerbated asthma, compared with those who had no exacerbations, including low birth weight (7% vs. 5%), small for gestational age (3% vs. 2%), preterm birth (8% vs. 7%), and congenital malformation (6% vs. 5%). All P values were less than .001, except for small for gestational age, which was P = .008.

In addition, significantly more babies of asthmatic women with exacerbated asthma during pregnancy had respiratory problems including asthma and pneumonia, compared with those of asthmatic women who had no exacerbations during pregnancy, at 38% vs. 31% and 24% vs. 22% (P less than .001 for both). The researchers found no significant interactions between maternal age and smoking and asthma exacerbations.

The findings were limited by several factors, including the lack of a validated algorithm for asthma exacerbation, which the researchers defined as five or more visits to a general practice clinician for asthma during pregnancy. Other limitations included the lack of categorizing asthma exacerbation by severity, and the inability to include the potential effects of asthma medication on maternal and fetal outcomes, Dr. Abdullah and colleagues noted.

However, the results were strengthened by the large sample size and ability to follow babies from birth until 5 years of age, they said.

“Targeting women with asthma during pregnancy and ensuring appropriate asthma management and postpartum follow-up may help to reduce the risk of pregnancy complications, adverse perinatal outcomes, and early childhood respiratory disorders,” they concluded.

This study is important because asthma is a common, potentially serious medical condition that complicates approximately 4%-8% of pregnancies, and one in three women with asthma experience an exacerbation during pregnancy, Iris Krishna, MD, a specialist in maternal/fetal medicine at Emory University, Atlanta, said in an interview.

“This study is unique in that it uses population-level data to assess the association between an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy and adverse perinatal outcomes,” Dr. Krishna said. “After adjusting for confounders, and consistent with previous studies, study findings suggest an increased risk for women with asthma who have an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy for preeclampsia [odds ratio, 1.3; P less than .001], pregnancy-induced hypertension [OR, 1.17; P less than .05], low-birth-weight infant [OR, 1.14; P less than .05], preterm birth [OR, 1.14; P less than .05], and congenital malformations [OR, 1.21; P less than .001].”

Dr. Krishna also noted the impact on early childhood outcomes. “In this study, children born to women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy had a 23% higher risk of developing asthma before 5 years of age, which is consistent with previous studies. [The] investigators also reported a 12% higher risk of having pneumonia during the first 5 years of life for children born to women who had an asthma exacerbation during pregnancy.”

“Previous studies have suggested children born to mothers with uncontrolled asthma have an increased risk for respiratory infections, but this study is the first to report an association with pneumonia,” she said. This increased risk for childhood respiratory disorders warrants further study.

Consequently, “Women with asthma during pregnancy should have appropriate management to ensure good control to optimize pregnancy outcome,” Dr. Krishna emphasized. “Women who experience asthma exacerbations in pregnancy are at increased risk for preeclampsia, [pregnancy-induced hypertension], low birth weight, and preterm delivery and may require closer monitoring.”

The study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences. The researchers and Dr. Krishna had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Abdullah K et al. Eur Respir J. 2019 Nov 26. doi: 10.1183/13993003.01335-2019.

FROM THE EUROPEAN RESPIRATORY JOURNAL

Do women with diabetes need more CVD risk reduction than men?

BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA – Whether cardiovascular disease risk reduction efforts should be more aggressive in women than men with diabetes depends on how you interpret the data.

Two experts came to different conclusions on this question during a heated, but jovial, debate last week here at the International Diabetes Federation 2019 Congress.

Endocrinologist David Simmons, MB, BChir, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, Australia, argued that diabetes erases the well-described life expectancy advantage of 4-7 years that women experience over men in the general population.

He also highlighted the fact that the heightened risk is of particular concern in both younger women and those with prior gestational diabetes.

But Timothy Davis, BMedSc, MB, BS, DPhil, an endocrinologist and general physician at Fremantle (Australia) Hospital, countered that the data only show the diabetes-attributable excess cardiovascular risk is higher in women than men, but that the absolute risk is actually greater in men.

Moreover, he argued, at least in type 1 diabetes, there is no evidence that more aggressive cardiovascular risk factor management improves outcomes.

Yes: Diabetes eliminates female CVD protection

Dr. Simmons began by pointing out that, although on average women die at an older age than men, it has been known for over 40 years that this “female protection” is lost in insulin-treated women, particularly as a result of their increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

In a 2015 meta-analysis of 26 studies, women with type 1 diabetes were found to have about a 37% greater risk of all-cause mortality, compared with men with the condition when mortality is contrasted with that of the general population, and twice the risk of both fatal and nonfatal vascular events.

The risk appeared to be greater in women who were younger at the time of diabetes diagnosis. “This is a really important point – the time we would want to intervene,” Dr. Simmons said.

In another meta-analysis of 30 studies including 2,307,694 individuals with type 2 diabetes and 252,491 deaths, the pooled women-to-men ratio of the standardized mortality ratio for all-cause mortality was 1.14.

In those with versus without type 2 diabetes, the pooled standardized mortality ratio in women was 2.30 and in men was 1.94, both significant, compared with those without diabetes.

And in a 2006 meta-analysis of 22 studies involving individuals with type 2 diabetes, the pooled data showed a 46% excess relative risk using standardized mortality ratios in women versus men for fatal coronary artery disease.

Meanwhile, in a 2018 meta-analysis of 68 studies involving nearly 1 million adults examining differences in occlusive vascular disease, after controlling for major vascular risk factors, diabetes roughly doubled the risk for occlusive vascular mortality in men (relative risk, 2.10), but tripled it in women (3.00).

Women with diabetes aged 35-59 years had the highest relative risk for death over follow-up across all age and sex groups: They had 5.5 times the excess risk, compared with those without diabetes, while the excess risk for men of that age was 2.3-fold.

“So very clearly, it’s these young women who are most at risk, “emphasized Dr. Simmons, who is an investigator for Novo Nordisk and a speaker for Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

Are disparities because of differences in cvd risk factor management?

The question has arisen whether the female/male differences might be because of differences in cardiovascular risk factor management, Simmons noted.

A 2015 American Heart Association statement laid out the evidence for lower prescribing of statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors in women, compared with men, Dr. Simmons said.

And some studies suggest medication adherence is lower in women than men.

In terms of medications, fenofibrate appears to produce better outcomes in women than men, but there is no evidence of gender differences in the effects of statins, ACE inhibitors, or aspirin, Simmons said.

He also outlined the results of a 2008 study of 78,254 patients with acute myocardial infarction from 420 U.S. hospitals in 2001-2006.

Women were older, had more comorbidities, less often presented with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), and had a higher rate of unadjusted in-hospital death (8.2% vs. 5.7%; P less than .0001) than men. Of the participants, 33% of women had diabetes, compared with 28% of men.

The in-hospital mortality difference disappeared after multivariable adjustment, but women with STEMI still had higher adjusted mortality rates than men.

“The underuse of evidence-based treatments and delayed reperfusion in women represent potential opportunities for reducing sex disparities in care and outcome after acute myocardial infarction,” the authors concluded.

“It’s very clear amongst our cardiology colleagues that something needs to be done and that we need more aggressive cardiological risk reduction in women,” Dr. Simmons said.

“The AHA has already decided this. It’s already a policy. So why are we having this debate?” he wondered.

He also pointed out that women with prior gestational diabetes are an exceptionally high–risk group, with a twofold excess risk for cardiovascular disease within the first 10 years post partum.

“We need to do something about this particularly high-risk group, independent of debates about gender,” Dr. Simmons emphasized. “Clearly, women with diabetes warrant more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes, especially at those younger ages,” he concluded.

No: Confusion about relative risk within each sex and absolute risk

Dr. Davis began his counterargument by stating that estimation of absolute vascular risk is an established part of strategies to prevent cardiovascular disease, including in diabetes.

And that risk, he stressed, is actually higher in men.

“Male sex is a consistent adverse risk factor in cardiovascular disease event prediction equations in type 2 diabetes. Identifying absolute risk is important,” he said, noting risk calculators include male sex, such as the risk engine derived from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Trial.

And in the Australian population-based Fremantle study, of which Dr. Davis is an author, the absolute 5-year incidence rates for all outcomes – including myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, lower extremity amputation, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality – were consistently higher in men versus women in the first phase, which began in the 1990s and included 1,426 individuals with diabetes (91% had type 2 diabetes).

In the ongoing second phase, which began in 2008 with 1,732 participants, overall rates of those outcomes are lower and the discrepancy between men and women has narrowed, Dr. Davis noted.

Overall, the Fremantle study data “suggest that women with type 2 diabetes do not need more aggressive cardiovascular reduction than men with type 2 diabetes because they are not at increased absolute vascular risk,” he stressed.

And in a “sensitivity analysis” of two areas in Finland, the authors concluded that the stronger effect of type 2 diabetes on the risk of congenital heart disease (CHD) in women, compared with men was in part explained by a heavier risk factor burden and a greater effect of blood pressure and atherogenic dyslipidemia in women with diabetes, he explained.

The Finnish authors wrote, “In terms of absolute risk of CHD death or a major CHD event, diabetes almost completely abolished the female protection from CHD.”

But, Dr. Davis emphasized, rates were not higher in females.

So then, “why is there the view that women with type 2 diabetes need more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes?

“It probably comes back to confusion based on absolute risk versus a comparison of relative risk within each sex,” he asserted.

ADA Standards of Medical Care 2019 don’t mention gender

Lastly, in a meta-analysis published just in July this year involving more than 5 million participants, compared with men with diabetes, women with diabetes had a 58% and 13% greater risk of CHD and all-cause mortality, respectively.

“This points to an urgent need to develop sex- and gender-specific risk assessment strategies and therapeutic interventions that target diabetes management in the context of CHD prevention,” the authors concluded.

But, Dr. Davis noted, “It is not absolute vascular risk. It’s a relative risk compared across the two genders. In the paper, there is no mention of absolute vascular risk.

“Greater CVD mortality in women with and without diabetes, versus men, doesn’t mean there’s also an absolute vascular increase in women versus men with diabetes,” he said.

Moreover, Dr. Davis pointed out that in an editorial accompanying the 2015 meta-analysis in type 1 diabetes, Simmons had actually stated that absolute mortality rates are highest in men.

“I don’t know what happened to his epidemiology knowledge in the last 4 years but it seems to have gone backwards,” he joked to his debate opponent.

And, Dr. Davis asserted, even if there were a higher risk in women with type 1 diabetes, there is no evidence that cardiovascular risk reduction measures affect endpoints in that patient population. Only about 8% of people with diabetes in statin trials had type 1 diabetes.

Indeed, he noted, in the American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2019, the treatment goals for individual cardiovascular risk factors do not mention gender.

What’s more, Dr. David said, there is evidence that women are significantly less likely than men to take prescribed statins and are more likely to have an eating disorder and underdose insulin, “suggesting significant issues with compliance. ... So, trying to get more intensive risk reduction in women may be a challenge.”

“Women with diabetes do not need more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes, irrespective of type,” he concluded.

A version of this story originally appeared on medscape.com.

BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA – Whether cardiovascular disease risk reduction efforts should be more aggressive in women than men with diabetes depends on how you interpret the data.

Two experts came to different conclusions on this question during a heated, but jovial, debate last week here at the International Diabetes Federation 2019 Congress.

Endocrinologist David Simmons, MB, BChir, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, Australia, argued that diabetes erases the well-described life expectancy advantage of 4-7 years that women experience over men in the general population.

He also highlighted the fact that the heightened risk is of particular concern in both younger women and those with prior gestational diabetes.

But Timothy Davis, BMedSc, MB, BS, DPhil, an endocrinologist and general physician at Fremantle (Australia) Hospital, countered that the data only show the diabetes-attributable excess cardiovascular risk is higher in women than men, but that the absolute risk is actually greater in men.

Moreover, he argued, at least in type 1 diabetes, there is no evidence that more aggressive cardiovascular risk factor management improves outcomes.

Yes: Diabetes eliminates female CVD protection

Dr. Simmons began by pointing out that, although on average women die at an older age than men, it has been known for over 40 years that this “female protection” is lost in insulin-treated women, particularly as a result of their increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

In a 2015 meta-analysis of 26 studies, women with type 1 diabetes were found to have about a 37% greater risk of all-cause mortality, compared with men with the condition when mortality is contrasted with that of the general population, and twice the risk of both fatal and nonfatal vascular events.

The risk appeared to be greater in women who were younger at the time of diabetes diagnosis. “This is a really important point – the time we would want to intervene,” Dr. Simmons said.

In another meta-analysis of 30 studies including 2,307,694 individuals with type 2 diabetes and 252,491 deaths, the pooled women-to-men ratio of the standardized mortality ratio for all-cause mortality was 1.14.

In those with versus without type 2 diabetes, the pooled standardized mortality ratio in women was 2.30 and in men was 1.94, both significant, compared with those without diabetes.

And in a 2006 meta-analysis of 22 studies involving individuals with type 2 diabetes, the pooled data showed a 46% excess relative risk using standardized mortality ratios in women versus men for fatal coronary artery disease.

Meanwhile, in a 2018 meta-analysis of 68 studies involving nearly 1 million adults examining differences in occlusive vascular disease, after controlling for major vascular risk factors, diabetes roughly doubled the risk for occlusive vascular mortality in men (relative risk, 2.10), but tripled it in women (3.00).

Women with diabetes aged 35-59 years had the highest relative risk for death over follow-up across all age and sex groups: They had 5.5 times the excess risk, compared with those without diabetes, while the excess risk for men of that age was 2.3-fold.

“So very clearly, it’s these young women who are most at risk, “emphasized Dr. Simmons, who is an investigator for Novo Nordisk and a speaker for Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

Are disparities because of differences in cvd risk factor management?

The question has arisen whether the female/male differences might be because of differences in cardiovascular risk factor management, Simmons noted.

A 2015 American Heart Association statement laid out the evidence for lower prescribing of statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors in women, compared with men, Dr. Simmons said.

And some studies suggest medication adherence is lower in women than men.

In terms of medications, fenofibrate appears to produce better outcomes in women than men, but there is no evidence of gender differences in the effects of statins, ACE inhibitors, or aspirin, Simmons said.

He also outlined the results of a 2008 study of 78,254 patients with acute myocardial infarction from 420 U.S. hospitals in 2001-2006.

Women were older, had more comorbidities, less often presented with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), and had a higher rate of unadjusted in-hospital death (8.2% vs. 5.7%; P less than .0001) than men. Of the participants, 33% of women had diabetes, compared with 28% of men.

The in-hospital mortality difference disappeared after multivariable adjustment, but women with STEMI still had higher adjusted mortality rates than men.

“The underuse of evidence-based treatments and delayed reperfusion in women represent potential opportunities for reducing sex disparities in care and outcome after acute myocardial infarction,” the authors concluded.

“It’s very clear amongst our cardiology colleagues that something needs to be done and that we need more aggressive cardiological risk reduction in women,” Dr. Simmons said.

“The AHA has already decided this. It’s already a policy. So why are we having this debate?” he wondered.

He also pointed out that women with prior gestational diabetes are an exceptionally high–risk group, with a twofold excess risk for cardiovascular disease within the first 10 years post partum.

“We need to do something about this particularly high-risk group, independent of debates about gender,” Dr. Simmons emphasized. “Clearly, women with diabetes warrant more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes, especially at those younger ages,” he concluded.

No: Confusion about relative risk within each sex and absolute risk

Dr. Davis began his counterargument by stating that estimation of absolute vascular risk is an established part of strategies to prevent cardiovascular disease, including in diabetes.

And that risk, he stressed, is actually higher in men.

“Male sex is a consistent adverse risk factor in cardiovascular disease event prediction equations in type 2 diabetes. Identifying absolute risk is important,” he said, noting risk calculators include male sex, such as the risk engine derived from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Trial.

And in the Australian population-based Fremantle study, of which Dr. Davis is an author, the absolute 5-year incidence rates for all outcomes – including myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, lower extremity amputation, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality – were consistently higher in men versus women in the first phase, which began in the 1990s and included 1,426 individuals with diabetes (91% had type 2 diabetes).

In the ongoing second phase, which began in 2008 with 1,732 participants, overall rates of those outcomes are lower and the discrepancy between men and women has narrowed, Dr. Davis noted.

Overall, the Fremantle study data “suggest that women with type 2 diabetes do not need more aggressive cardiovascular reduction than men with type 2 diabetes because they are not at increased absolute vascular risk,” he stressed.

And in a “sensitivity analysis” of two areas in Finland, the authors concluded that the stronger effect of type 2 diabetes on the risk of congenital heart disease (CHD) in women, compared with men was in part explained by a heavier risk factor burden and a greater effect of blood pressure and atherogenic dyslipidemia in women with diabetes, he explained.

The Finnish authors wrote, “In terms of absolute risk of CHD death or a major CHD event, diabetes almost completely abolished the female protection from CHD.”

But, Dr. Davis emphasized, rates were not higher in females.

So then, “why is there the view that women with type 2 diabetes need more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes?

“It probably comes back to confusion based on absolute risk versus a comparison of relative risk within each sex,” he asserted.

ADA Standards of Medical Care 2019 don’t mention gender

Lastly, in a meta-analysis published just in July this year involving more than 5 million participants, compared with men with diabetes, women with diabetes had a 58% and 13% greater risk of CHD and all-cause mortality, respectively.

“This points to an urgent need to develop sex- and gender-specific risk assessment strategies and therapeutic interventions that target diabetes management in the context of CHD prevention,” the authors concluded.

But, Dr. Davis noted, “It is not absolute vascular risk. It’s a relative risk compared across the two genders. In the paper, there is no mention of absolute vascular risk.

“Greater CVD mortality in women with and without diabetes, versus men, doesn’t mean there’s also an absolute vascular increase in women versus men with diabetes,” he said.

Moreover, Dr. Davis pointed out that in an editorial accompanying the 2015 meta-analysis in type 1 diabetes, Simmons had actually stated that absolute mortality rates are highest in men.

“I don’t know what happened to his epidemiology knowledge in the last 4 years but it seems to have gone backwards,” he joked to his debate opponent.

And, Dr. Davis asserted, even if there were a higher risk in women with type 1 diabetes, there is no evidence that cardiovascular risk reduction measures affect endpoints in that patient population. Only about 8% of people with diabetes in statin trials had type 1 diabetes.

Indeed, he noted, in the American Diabetes Association Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes – 2019, the treatment goals for individual cardiovascular risk factors do not mention gender.

What’s more, Dr. David said, there is evidence that women are significantly less likely than men to take prescribed statins and are more likely to have an eating disorder and underdose insulin, “suggesting significant issues with compliance. ... So, trying to get more intensive risk reduction in women may be a challenge.”

“Women with diabetes do not need more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes, irrespective of type,” he concluded.

A version of this story originally appeared on medscape.com.

BUSAN, SOUTH KOREA – Whether cardiovascular disease risk reduction efforts should be more aggressive in women than men with diabetes depends on how you interpret the data.

Two experts came to different conclusions on this question during a heated, but jovial, debate last week here at the International Diabetes Federation 2019 Congress.

Endocrinologist David Simmons, MB, BChir, Western Sydney University, Campbelltown, Australia, argued that diabetes erases the well-described life expectancy advantage of 4-7 years that women experience over men in the general population.

He also highlighted the fact that the heightened risk is of particular concern in both younger women and those with prior gestational diabetes.

But Timothy Davis, BMedSc, MB, BS, DPhil, an endocrinologist and general physician at Fremantle (Australia) Hospital, countered that the data only show the diabetes-attributable excess cardiovascular risk is higher in women than men, but that the absolute risk is actually greater in men.

Moreover, he argued, at least in type 1 diabetes, there is no evidence that more aggressive cardiovascular risk factor management improves outcomes.

Yes: Diabetes eliminates female CVD protection

Dr. Simmons began by pointing out that, although on average women die at an older age than men, it has been known for over 40 years that this “female protection” is lost in insulin-treated women, particularly as a result of their increased risk for cardiovascular disease.

In a 2015 meta-analysis of 26 studies, women with type 1 diabetes were found to have about a 37% greater risk of all-cause mortality, compared with men with the condition when mortality is contrasted with that of the general population, and twice the risk of both fatal and nonfatal vascular events.

The risk appeared to be greater in women who were younger at the time of diabetes diagnosis. “This is a really important point – the time we would want to intervene,” Dr. Simmons said.

In another meta-analysis of 30 studies including 2,307,694 individuals with type 2 diabetes and 252,491 deaths, the pooled women-to-men ratio of the standardized mortality ratio for all-cause mortality was 1.14.

In those with versus without type 2 diabetes, the pooled standardized mortality ratio in women was 2.30 and in men was 1.94, both significant, compared with those without diabetes.

And in a 2006 meta-analysis of 22 studies involving individuals with type 2 diabetes, the pooled data showed a 46% excess relative risk using standardized mortality ratios in women versus men for fatal coronary artery disease.

Meanwhile, in a 2018 meta-analysis of 68 studies involving nearly 1 million adults examining differences in occlusive vascular disease, after controlling for major vascular risk factors, diabetes roughly doubled the risk for occlusive vascular mortality in men (relative risk, 2.10), but tripled it in women (3.00).

Women with diabetes aged 35-59 years had the highest relative risk for death over follow-up across all age and sex groups: They had 5.5 times the excess risk, compared with those without diabetes, while the excess risk for men of that age was 2.3-fold.

“So very clearly, it’s these young women who are most at risk, “emphasized Dr. Simmons, who is an investigator for Novo Nordisk and a speaker for Medtronic, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

Are disparities because of differences in cvd risk factor management?

The question has arisen whether the female/male differences might be because of differences in cardiovascular risk factor management, Simmons noted.

A 2015 American Heart Association statement laid out the evidence for lower prescribing of statins, aspirin, beta-blockers, and ACE inhibitors in women, compared with men, Dr. Simmons said.

And some studies suggest medication adherence is lower in women than men.

In terms of medications, fenofibrate appears to produce better outcomes in women than men, but there is no evidence of gender differences in the effects of statins, ACE inhibitors, or aspirin, Simmons said.

He also outlined the results of a 2008 study of 78,254 patients with acute myocardial infarction from 420 U.S. hospitals in 2001-2006.

Women were older, had more comorbidities, less often presented with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), and had a higher rate of unadjusted in-hospital death (8.2% vs. 5.7%; P less than .0001) than men. Of the participants, 33% of women had diabetes, compared with 28% of men.

The in-hospital mortality difference disappeared after multivariable adjustment, but women with STEMI still had higher adjusted mortality rates than men.

“The underuse of evidence-based treatments and delayed reperfusion in women represent potential opportunities for reducing sex disparities in care and outcome after acute myocardial infarction,” the authors concluded.

“It’s very clear amongst our cardiology colleagues that something needs to be done and that we need more aggressive cardiological risk reduction in women,” Dr. Simmons said.

“The AHA has already decided this. It’s already a policy. So why are we having this debate?” he wondered.

He also pointed out that women with prior gestational diabetes are an exceptionally high–risk group, with a twofold excess risk for cardiovascular disease within the first 10 years post partum.

“We need to do something about this particularly high-risk group, independent of debates about gender,” Dr. Simmons emphasized. “Clearly, women with diabetes warrant more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes, especially at those younger ages,” he concluded.

No: Confusion about relative risk within each sex and absolute risk

Dr. Davis began his counterargument by stating that estimation of absolute vascular risk is an established part of strategies to prevent cardiovascular disease, including in diabetes.

And that risk, he stressed, is actually higher in men.

“Male sex is a consistent adverse risk factor in cardiovascular disease event prediction equations in type 2 diabetes. Identifying absolute risk is important,” he said, noting risk calculators include male sex, such as the risk engine derived from the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Trial.

And in the Australian population-based Fremantle study, of which Dr. Davis is an author, the absolute 5-year incidence rates for all outcomes – including myocardial infarction, stroke, heart failure, lower extremity amputation, cardiovascular mortality, and all-cause mortality – were consistently higher in men versus women in the first phase, which began in the 1990s and included 1,426 individuals with diabetes (91% had type 2 diabetes).

In the ongoing second phase, which began in 2008 with 1,732 participants, overall rates of those outcomes are lower and the discrepancy between men and women has narrowed, Dr. Davis noted.

Overall, the Fremantle study data “suggest that women with type 2 diabetes do not need more aggressive cardiovascular reduction than men with type 2 diabetes because they are not at increased absolute vascular risk,” he stressed.

And in a “sensitivity analysis” of two areas in Finland, the authors concluded that the stronger effect of type 2 diabetes on the risk of congenital heart disease (CHD) in women, compared with men was in part explained by a heavier risk factor burden and a greater effect of blood pressure and atherogenic dyslipidemia in women with diabetes, he explained.

The Finnish authors wrote, “In terms of absolute risk of CHD death or a major CHD event, diabetes almost completely abolished the female protection from CHD.”

But, Dr. Davis emphasized, rates were not higher in females.

So then, “why is there the view that women with type 2 diabetes need more aggressive cardiovascular risk reduction than men with diabetes?

“It probably comes back to confusion based on absolute risk versus a comparison of relative risk within each sex,” he asserted.