User login

Sexual function in transfeminine patients following gender-affirming vaginoplasty

For many patients, sexual function is an important component of a healthy quality of life.1 However, to many transgender individuals, their sexual organs are often a source of gender dysphoria, which can significantly inhibit sexual activity with their partners. Patients who seek gender-affirming surgery not only hope to have these feelings of dysphoria alleviated but also desire improvement in sexual function after surgery. While the medical and psychiatric criteria for patients seeking vaginoplasty procedures are well established by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health,2 there is little guidance surrounding the discourse surgeons should have regarding sexual function pre- and postsurgery.

Setting realistic expectations is one of the major challenges surgeons and patients alike face in preoperative and postoperative encounters. Patients not only are tasked with recovering from a major surgical procedure, but must also now learn their new anatomy, which includes learning how to urinate, maintain proper neovaginal hygiene, and experience sexual pleasure.

Given the permanence of these procedures and the possibility of loss of sexual function, the surgeon must ensure that patients truly comprehend the nature of the procedure and its complications. During the preoperative consultation, the surgeon must inquire about any desire for future fertility, discuss any history of pelvic radiation, epispadias, hypospadias, current erectile dysfunction, libido, comorbid medical conditions (such as diabetes or smoking), current sexual practices, and overall patient goals regarding their surgical outcome.

The vast majority of patients state they will experience a significant decrease in gender dysphoria with the removal of their current natal male genitalia.1 However, some patients have very specific preferences regarding the cosmetic appearance of vulvar structures. Others have more functional concerns about neovaginal depth and the ability to have receptive penetrative intercourse. It is important to note that not all transgender women have male partners. Furthermore, whether patients have male or female partners, some patients do not desire the ability to have penetrative intercourse and/or do not want to undergo the potential complications of a full-depth vaginoplasty. In these patients, offering a “shallow depth” vaginoplasty may be acceptable.

It is useful in the consultation to discuss a patient’s sexual partners and sexual practices in order to best determine the type of procedure that may be appropriate for a patient. In my practice, I emphasize that full-depth vaginoplasties require a lifelong commitment of dilation to maintain patency. Unlike cisgender women, patients must also douche to ensure appropriate vaginal hygiene. Regarding cosmetic preferences patients may have, it is essential to educate patients on the significant variation in the appearance of vulvar structures among both cisgender and transgender women.

During the surgical consultation, I review which structures from their natal genitalia are removed and which structures are utilized to create the neo–vulvar-vaginal anatomy. The testicles and spermatic cord are excised. The dorsal neurovascular bundle of the penile shaft and portion of the dorsal aspect of the glans penis are used to create the neoclitoris. A combination of penile shaft skin and scrotal skin is used to line the neovaginal canal. The erectile tissue of the penile shaft is also resected and the natal urethra is shortened and spatulated to create the urethral plate and urethral meatus. I also remind patients that the prostate remains intact during vaginoplasty procedures. Unless patients undergo the colonic interposition vaginoplasty and in some cases the peritoneal vaginoplasty, the neovaginal canal is not self-lubricating, nor will patients experience ejaculation after surgery. In the presurgical period, I often remind patients that the location of erogenous sensation after surgery will be altered and the method by which they self-stimulate will also be different. It is also essential to document whether patients can achieve satisfactory orgasms presurgically in order to determine adequate sexual function in the postoperative period.

It cannot be emphasized enough that the best predictor of unsatisfactory sexual function after genital gender-affirming surgery is poor sexual function prior to surgery.1,3

Retention of sexual function after gender-affirming genital surgery is common, with studies citing a range of 70%-90% of patients reporting their ability to regularly achieve an orgasm after surgery.1,4 In some cases, patients will report issues with sexual function after surgery despite having no prior history of sexual dysfunction. If patients present with complaints of postsurgical anorgasmia, the provider should rule out insufficient time for wound healing and resolution of surgery-site pain, and determine if there was an intraoperative injury to the neurovascular bundle or significant clitoral necrosis. A thorough genital exam should include a sensory examination of the neoclitoris and the introitus and neovaginal canal for signs of scarring, stenosis, loss of vaginal depth, or high-tone pelvic-floor dysfunction.

Unfortunately, if the neurovascular bundle is injured or if a patient experienced clitoral necrosis, the likelihood of a patient regaining sensation is decreased, although there are currently no studies examining the exact rates. It is also important to reassure patients that wound healing after surgery and relearning sexual function is not linear. I encourage patients to initially self-stimulate without a partner as they learn their new anatomy in order to remove any potential performance anxiety a partner could cause immediately after surgery. Similar to the approach to sexual dysfunction in cisgender patients, referral to a specialist in sexual health and/or pelvic floor physical therapy are useful adjuncts, depending on the findings from the physical exam and patient symptoms.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa.

References

1. Garcia MM. Clin Plastic Surg. 2018;45:437-46.

2. Eli Coleman WB et al. “Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender non-conforming people” 7th version. World Professional Association for Transgender Health: 2012.

3. Garcia MM et al. Transl Androl Urol. 2014;3:156.

4. Ferrando CA, Bowers ML. “Genital gender confirmation surgery for patients assigned male at birth” In: Ferrando CA, ed. “Comprehensive care for the transgender patient” Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020:82-92.

For many patients, sexual function is an important component of a healthy quality of life.1 However, to many transgender individuals, their sexual organs are often a source of gender dysphoria, which can significantly inhibit sexual activity with their partners. Patients who seek gender-affirming surgery not only hope to have these feelings of dysphoria alleviated but also desire improvement in sexual function after surgery. While the medical and psychiatric criteria for patients seeking vaginoplasty procedures are well established by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health,2 there is little guidance surrounding the discourse surgeons should have regarding sexual function pre- and postsurgery.

Setting realistic expectations is one of the major challenges surgeons and patients alike face in preoperative and postoperative encounters. Patients not only are tasked with recovering from a major surgical procedure, but must also now learn their new anatomy, which includes learning how to urinate, maintain proper neovaginal hygiene, and experience sexual pleasure.

Given the permanence of these procedures and the possibility of loss of sexual function, the surgeon must ensure that patients truly comprehend the nature of the procedure and its complications. During the preoperative consultation, the surgeon must inquire about any desire for future fertility, discuss any history of pelvic radiation, epispadias, hypospadias, current erectile dysfunction, libido, comorbid medical conditions (such as diabetes or smoking), current sexual practices, and overall patient goals regarding their surgical outcome.

The vast majority of patients state they will experience a significant decrease in gender dysphoria with the removal of their current natal male genitalia.1 However, some patients have very specific preferences regarding the cosmetic appearance of vulvar structures. Others have more functional concerns about neovaginal depth and the ability to have receptive penetrative intercourse. It is important to note that not all transgender women have male partners. Furthermore, whether patients have male or female partners, some patients do not desire the ability to have penetrative intercourse and/or do not want to undergo the potential complications of a full-depth vaginoplasty. In these patients, offering a “shallow depth” vaginoplasty may be acceptable.

It is useful in the consultation to discuss a patient’s sexual partners and sexual practices in order to best determine the type of procedure that may be appropriate for a patient. In my practice, I emphasize that full-depth vaginoplasties require a lifelong commitment of dilation to maintain patency. Unlike cisgender women, patients must also douche to ensure appropriate vaginal hygiene. Regarding cosmetic preferences patients may have, it is essential to educate patients on the significant variation in the appearance of vulvar structures among both cisgender and transgender women.

During the surgical consultation, I review which structures from their natal genitalia are removed and which structures are utilized to create the neo–vulvar-vaginal anatomy. The testicles and spermatic cord are excised. The dorsal neurovascular bundle of the penile shaft and portion of the dorsal aspect of the glans penis are used to create the neoclitoris. A combination of penile shaft skin and scrotal skin is used to line the neovaginal canal. The erectile tissue of the penile shaft is also resected and the natal urethra is shortened and spatulated to create the urethral plate and urethral meatus. I also remind patients that the prostate remains intact during vaginoplasty procedures. Unless patients undergo the colonic interposition vaginoplasty and in some cases the peritoneal vaginoplasty, the neovaginal canal is not self-lubricating, nor will patients experience ejaculation after surgery. In the presurgical period, I often remind patients that the location of erogenous sensation after surgery will be altered and the method by which they self-stimulate will also be different. It is also essential to document whether patients can achieve satisfactory orgasms presurgically in order to determine adequate sexual function in the postoperative period.

It cannot be emphasized enough that the best predictor of unsatisfactory sexual function after genital gender-affirming surgery is poor sexual function prior to surgery.1,3

Retention of sexual function after gender-affirming genital surgery is common, with studies citing a range of 70%-90% of patients reporting their ability to regularly achieve an orgasm after surgery.1,4 In some cases, patients will report issues with sexual function after surgery despite having no prior history of sexual dysfunction. If patients present with complaints of postsurgical anorgasmia, the provider should rule out insufficient time for wound healing and resolution of surgery-site pain, and determine if there was an intraoperative injury to the neurovascular bundle or significant clitoral necrosis. A thorough genital exam should include a sensory examination of the neoclitoris and the introitus and neovaginal canal for signs of scarring, stenosis, loss of vaginal depth, or high-tone pelvic-floor dysfunction.

Unfortunately, if the neurovascular bundle is injured or if a patient experienced clitoral necrosis, the likelihood of a patient regaining sensation is decreased, although there are currently no studies examining the exact rates. It is also important to reassure patients that wound healing after surgery and relearning sexual function is not linear. I encourage patients to initially self-stimulate without a partner as they learn their new anatomy in order to remove any potential performance anxiety a partner could cause immediately after surgery. Similar to the approach to sexual dysfunction in cisgender patients, referral to a specialist in sexual health and/or pelvic floor physical therapy are useful adjuncts, depending on the findings from the physical exam and patient symptoms.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa.

References

1. Garcia MM. Clin Plastic Surg. 2018;45:437-46.

2. Eli Coleman WB et al. “Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender non-conforming people” 7th version. World Professional Association for Transgender Health: 2012.

3. Garcia MM et al. Transl Androl Urol. 2014;3:156.

4. Ferrando CA, Bowers ML. “Genital gender confirmation surgery for patients assigned male at birth” In: Ferrando CA, ed. “Comprehensive care for the transgender patient” Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020:82-92.

For many patients, sexual function is an important component of a healthy quality of life.1 However, to many transgender individuals, their sexual organs are often a source of gender dysphoria, which can significantly inhibit sexual activity with their partners. Patients who seek gender-affirming surgery not only hope to have these feelings of dysphoria alleviated but also desire improvement in sexual function after surgery. While the medical and psychiatric criteria for patients seeking vaginoplasty procedures are well established by the World Professional Association for Transgender Health,2 there is little guidance surrounding the discourse surgeons should have regarding sexual function pre- and postsurgery.

Setting realistic expectations is one of the major challenges surgeons and patients alike face in preoperative and postoperative encounters. Patients not only are tasked with recovering from a major surgical procedure, but must also now learn their new anatomy, which includes learning how to urinate, maintain proper neovaginal hygiene, and experience sexual pleasure.

Given the permanence of these procedures and the possibility of loss of sexual function, the surgeon must ensure that patients truly comprehend the nature of the procedure and its complications. During the preoperative consultation, the surgeon must inquire about any desire for future fertility, discuss any history of pelvic radiation, epispadias, hypospadias, current erectile dysfunction, libido, comorbid medical conditions (such as diabetes or smoking), current sexual practices, and overall patient goals regarding their surgical outcome.

The vast majority of patients state they will experience a significant decrease in gender dysphoria with the removal of their current natal male genitalia.1 However, some patients have very specific preferences regarding the cosmetic appearance of vulvar structures. Others have more functional concerns about neovaginal depth and the ability to have receptive penetrative intercourse. It is important to note that not all transgender women have male partners. Furthermore, whether patients have male or female partners, some patients do not desire the ability to have penetrative intercourse and/or do not want to undergo the potential complications of a full-depth vaginoplasty. In these patients, offering a “shallow depth” vaginoplasty may be acceptable.

It is useful in the consultation to discuss a patient’s sexual partners and sexual practices in order to best determine the type of procedure that may be appropriate for a patient. In my practice, I emphasize that full-depth vaginoplasties require a lifelong commitment of dilation to maintain patency. Unlike cisgender women, patients must also douche to ensure appropriate vaginal hygiene. Regarding cosmetic preferences patients may have, it is essential to educate patients on the significant variation in the appearance of vulvar structures among both cisgender and transgender women.

During the surgical consultation, I review which structures from their natal genitalia are removed and which structures are utilized to create the neo–vulvar-vaginal anatomy. The testicles and spermatic cord are excised. The dorsal neurovascular bundle of the penile shaft and portion of the dorsal aspect of the glans penis are used to create the neoclitoris. A combination of penile shaft skin and scrotal skin is used to line the neovaginal canal. The erectile tissue of the penile shaft is also resected and the natal urethra is shortened and spatulated to create the urethral plate and urethral meatus. I also remind patients that the prostate remains intact during vaginoplasty procedures. Unless patients undergo the colonic interposition vaginoplasty and in some cases the peritoneal vaginoplasty, the neovaginal canal is not self-lubricating, nor will patients experience ejaculation after surgery. In the presurgical period, I often remind patients that the location of erogenous sensation after surgery will be altered and the method by which they self-stimulate will also be different. It is also essential to document whether patients can achieve satisfactory orgasms presurgically in order to determine adequate sexual function in the postoperative period.

It cannot be emphasized enough that the best predictor of unsatisfactory sexual function after genital gender-affirming surgery is poor sexual function prior to surgery.1,3

Retention of sexual function after gender-affirming genital surgery is common, with studies citing a range of 70%-90% of patients reporting their ability to regularly achieve an orgasm after surgery.1,4 In some cases, patients will report issues with sexual function after surgery despite having no prior history of sexual dysfunction. If patients present with complaints of postsurgical anorgasmia, the provider should rule out insufficient time for wound healing and resolution of surgery-site pain, and determine if there was an intraoperative injury to the neurovascular bundle or significant clitoral necrosis. A thorough genital exam should include a sensory examination of the neoclitoris and the introitus and neovaginal canal for signs of scarring, stenosis, loss of vaginal depth, or high-tone pelvic-floor dysfunction.

Unfortunately, if the neurovascular bundle is injured or if a patient experienced clitoral necrosis, the likelihood of a patient regaining sensation is decreased, although there are currently no studies examining the exact rates. It is also important to reassure patients that wound healing after surgery and relearning sexual function is not linear. I encourage patients to initially self-stimulate without a partner as they learn their new anatomy in order to remove any potential performance anxiety a partner could cause immediately after surgery. Similar to the approach to sexual dysfunction in cisgender patients, referral to a specialist in sexual health and/or pelvic floor physical therapy are useful adjuncts, depending on the findings from the physical exam and patient symptoms.

Dr. Brandt is an ob.gyn. and fellowship-trained gender-affirming surgeon in West Reading, Pa.

References

1. Garcia MM. Clin Plastic Surg. 2018;45:437-46.

2. Eli Coleman WB et al. “Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender non-conforming people” 7th version. World Professional Association for Transgender Health: 2012.

3. Garcia MM et al. Transl Androl Urol. 2014;3:156.

4. Ferrando CA, Bowers ML. “Genital gender confirmation surgery for patients assigned male at birth” In: Ferrando CA, ed. “Comprehensive care for the transgender patient” Philadelphia: Elsevier, 2020:82-92.

Exercise limitations in COPD – not everyone needs more inhalers

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined by airway obstruction and alveolar damage caused by exposure to noxious air particles. The physiologic results include varying degrees of gas-exchange abnormality and mechanical respiratory limitation, often in the form of dynamic hyperinflation. There’s a third major contributor, though – skeletal muscle deconditioning. Only one of these abnormalities responds to inhalers.

When your patients with COPD report dyspnea or exercise intolerance, what do you do? Do you attempt to determine its character to pinpoint its origin? Do you quiz them about their baseline activity levels to quantify their conditioning? I bet you get right to the point and order a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET). That way you’ll be able to tease out all the contributors. Nah. Most likely you add an inhaler before continuing to rush through your COPD quality metrics: Vaccines? Check. Lung cancer screening? Check. Smoking cessation? Check.

The physiology of dyspnea and exercise limitation in COPD has been extensively studied. Work-of-breathing, dynamic hyperinflation, and gas-exchange inefficiencies interact with each other in complex ways to produce symptoms. The presence of deconditioning simply magnifies the existing abnormalities within the respiratory system by creating more strain at lower work rates. Acute exacerbations (AECOPD) and oral corticosteroids further aggravate skeletal muscle dysfunction.

The Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD) Report directs clinicians to use inhalers to manage dyspnea. If they’re already on one inhaler, they get another. This continues until they’re stabilized on a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA), long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS). The GOLD report also advises pulmonary rehabilitation for any patient with grade B through D disease. Unfortunately, the pulmonary rehabilitation recommendation is buried in the text and doesn’t appear within the popularized pharmacologic algorithms in the report’s figures.

The data for adding inhalers on top of each other to reduce AECOPD and improve overall quality of life (QOL) are good. However, although GOLD tells us to keep adding inhalers for the dyspneic patient with COPD, the authors acknowledge that this hasn’t been systematically tested. The difference? A statement doesn’t require the same formal, rigorous scientific analysis known as the GRADE approach. Using this kind of analysis, a recent clinical practice guideline by the American Thoracic Society found no benefit in dyspnea or respiratory QOL with step-up from inhaler monotherapy.

Inhalers won’t do anything for gas-exchange inefficiencies and deconditioning, at least not directly. A recent CPET study from the CanCOLD network found ventilatory inefficiency in 23% of GOLD 1 and 26% of GOLD 2-4 COPD patients. The numbers were higher for those who reported dyspnea. Skeletal muscle dysfunction rates are equally high.

Thus, dyspnea and exercise intolerance are major determinants of QOL in COPD, but inhalers will only get you so far. At a minimum, make sure you get an activity/exercise history from your patients with COPD. For those who are sedentary, provide an exercise prescription (really, it’s not that hard to do). If dyspnea persists despite LABA or LAMA monotherapy, clarify the complaint before doubling down. Finally, try to get the patient into a good pulmonary rehabilitation program. They’ll thank you afterwards.

Dr. Holley is Associate Professor, department of medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and Program Director, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medical Fellowship, department of medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, both in Bethesda, Md. He reported receiving research grants from Fisher-Paykel and receiving income from the American College of Chest Physicians.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined by airway obstruction and alveolar damage caused by exposure to noxious air particles. The physiologic results include varying degrees of gas-exchange abnormality and mechanical respiratory limitation, often in the form of dynamic hyperinflation. There’s a third major contributor, though – skeletal muscle deconditioning. Only one of these abnormalities responds to inhalers.

When your patients with COPD report dyspnea or exercise intolerance, what do you do? Do you attempt to determine its character to pinpoint its origin? Do you quiz them about their baseline activity levels to quantify their conditioning? I bet you get right to the point and order a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET). That way you’ll be able to tease out all the contributors. Nah. Most likely you add an inhaler before continuing to rush through your COPD quality metrics: Vaccines? Check. Lung cancer screening? Check. Smoking cessation? Check.

The physiology of dyspnea and exercise limitation in COPD has been extensively studied. Work-of-breathing, dynamic hyperinflation, and gas-exchange inefficiencies interact with each other in complex ways to produce symptoms. The presence of deconditioning simply magnifies the existing abnormalities within the respiratory system by creating more strain at lower work rates. Acute exacerbations (AECOPD) and oral corticosteroids further aggravate skeletal muscle dysfunction.

The Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD) Report directs clinicians to use inhalers to manage dyspnea. If they’re already on one inhaler, they get another. This continues until they’re stabilized on a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA), long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS). The GOLD report also advises pulmonary rehabilitation for any patient with grade B through D disease. Unfortunately, the pulmonary rehabilitation recommendation is buried in the text and doesn’t appear within the popularized pharmacologic algorithms in the report’s figures.

The data for adding inhalers on top of each other to reduce AECOPD and improve overall quality of life (QOL) are good. However, although GOLD tells us to keep adding inhalers for the dyspneic patient with COPD, the authors acknowledge that this hasn’t been systematically tested. The difference? A statement doesn’t require the same formal, rigorous scientific analysis known as the GRADE approach. Using this kind of analysis, a recent clinical practice guideline by the American Thoracic Society found no benefit in dyspnea or respiratory QOL with step-up from inhaler monotherapy.

Inhalers won’t do anything for gas-exchange inefficiencies and deconditioning, at least not directly. A recent CPET study from the CanCOLD network found ventilatory inefficiency in 23% of GOLD 1 and 26% of GOLD 2-4 COPD patients. The numbers were higher for those who reported dyspnea. Skeletal muscle dysfunction rates are equally high.

Thus, dyspnea and exercise intolerance are major determinants of QOL in COPD, but inhalers will only get you so far. At a minimum, make sure you get an activity/exercise history from your patients with COPD. For those who are sedentary, provide an exercise prescription (really, it’s not that hard to do). If dyspnea persists despite LABA or LAMA monotherapy, clarify the complaint before doubling down. Finally, try to get the patient into a good pulmonary rehabilitation program. They’ll thank you afterwards.

Dr. Holley is Associate Professor, department of medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and Program Director, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medical Fellowship, department of medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, both in Bethesda, Md. He reported receiving research grants from Fisher-Paykel and receiving income from the American College of Chest Physicians.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is defined by airway obstruction and alveolar damage caused by exposure to noxious air particles. The physiologic results include varying degrees of gas-exchange abnormality and mechanical respiratory limitation, often in the form of dynamic hyperinflation. There’s a third major contributor, though – skeletal muscle deconditioning. Only one of these abnormalities responds to inhalers.

When your patients with COPD report dyspnea or exercise intolerance, what do you do? Do you attempt to determine its character to pinpoint its origin? Do you quiz them about their baseline activity levels to quantify their conditioning? I bet you get right to the point and order a cardiopulmonary exercise test (CPET). That way you’ll be able to tease out all the contributors. Nah. Most likely you add an inhaler before continuing to rush through your COPD quality metrics: Vaccines? Check. Lung cancer screening? Check. Smoking cessation? Check.

The physiology of dyspnea and exercise limitation in COPD has been extensively studied. Work-of-breathing, dynamic hyperinflation, and gas-exchange inefficiencies interact with each other in complex ways to produce symptoms. The presence of deconditioning simply magnifies the existing abnormalities within the respiratory system by creating more strain at lower work rates. Acute exacerbations (AECOPD) and oral corticosteroids further aggravate skeletal muscle dysfunction.

The Global Strategy for the Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (GOLD) Report directs clinicians to use inhalers to manage dyspnea. If they’re already on one inhaler, they get another. This continues until they’re stabilized on a long-acting beta-agonist (LABA), long-acting muscarinic antagonist (LAMA), and an inhaled corticosteroid (ICS). The GOLD report also advises pulmonary rehabilitation for any patient with grade B through D disease. Unfortunately, the pulmonary rehabilitation recommendation is buried in the text and doesn’t appear within the popularized pharmacologic algorithms in the report’s figures.

The data for adding inhalers on top of each other to reduce AECOPD and improve overall quality of life (QOL) are good. However, although GOLD tells us to keep adding inhalers for the dyspneic patient with COPD, the authors acknowledge that this hasn’t been systematically tested. The difference? A statement doesn’t require the same formal, rigorous scientific analysis known as the GRADE approach. Using this kind of analysis, a recent clinical practice guideline by the American Thoracic Society found no benefit in dyspnea or respiratory QOL with step-up from inhaler monotherapy.

Inhalers won’t do anything for gas-exchange inefficiencies and deconditioning, at least not directly. A recent CPET study from the CanCOLD network found ventilatory inefficiency in 23% of GOLD 1 and 26% of GOLD 2-4 COPD patients. The numbers were higher for those who reported dyspnea. Skeletal muscle dysfunction rates are equally high.

Thus, dyspnea and exercise intolerance are major determinants of QOL in COPD, but inhalers will only get you so far. At a minimum, make sure you get an activity/exercise history from your patients with COPD. For those who are sedentary, provide an exercise prescription (really, it’s not that hard to do). If dyspnea persists despite LABA or LAMA monotherapy, clarify the complaint before doubling down. Finally, try to get the patient into a good pulmonary rehabilitation program. They’ll thank you afterwards.

Dr. Holley is Associate Professor, department of medicine, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences and Program Director, Pulmonary and Critical Care Medical Fellowship, department of medicine, Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, both in Bethesda, Md. He reported receiving research grants from Fisher-Paykel and receiving income from the American College of Chest Physicians.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

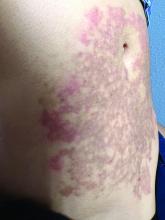

A White female presented with pruritic, reticulated, erythematous plaques on the abdomen

It is characterized by pruritic, erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and vesicles that appear in a reticular pattern, most commonly on the trunk. The lesions are typically followed by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

Although PP has been described in people of all races, ages, and sexes, it is predominantly observed in Japan, often in female young adults. Triggers may include a ketogenic diet, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy. Friction and contact allergic reactions to chrome or nickel have been proposed as exogenous trigger factors. Individual cases of Sjögren’s syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infections, and adult Still syndrome have also been associated with recurrent eruptions.

The diagnosis of PP is made both clinically and by biopsy. The histological features vary according to the stage of the disease. In early-stage disease, superficial and perivascular infiltration of neutrophils are prominent. Later stages are characterized by spongiosis and necrotic keratinocytes.

The first-line therapy for prurigo pigmentosa is oral minocycline. However, for some patients, doxycycline, macrolide antibiotics, or dapsone may be indicated. Adding carbohydrates to a keto diet may be helpful. In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed an interface dermatitis with eosinophils and neutrophils, consistent with prurigo pigmentosa. The cause of her PP remains idiopathic. She was treated with 100 mg doxycycline twice a day, which resulted in a resolution of active lesions. The patient did have postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California, and Mina Zulal, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Hamburg, Germany. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Beutler et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):533-43.

2. Kim et al. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):891-7.

3. Mufti et al. JAAD Int. 2021 Apr 10;3:79-87.

It is characterized by pruritic, erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and vesicles that appear in a reticular pattern, most commonly on the trunk. The lesions are typically followed by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

Although PP has been described in people of all races, ages, and sexes, it is predominantly observed in Japan, often in female young adults. Triggers may include a ketogenic diet, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy. Friction and contact allergic reactions to chrome or nickel have been proposed as exogenous trigger factors. Individual cases of Sjögren’s syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infections, and adult Still syndrome have also been associated with recurrent eruptions.

The diagnosis of PP is made both clinically and by biopsy. The histological features vary according to the stage of the disease. In early-stage disease, superficial and perivascular infiltration of neutrophils are prominent. Later stages are characterized by spongiosis and necrotic keratinocytes.

The first-line therapy for prurigo pigmentosa is oral minocycline. However, for some patients, doxycycline, macrolide antibiotics, or dapsone may be indicated. Adding carbohydrates to a keto diet may be helpful. In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed an interface dermatitis with eosinophils and neutrophils, consistent with prurigo pigmentosa. The cause of her PP remains idiopathic. She was treated with 100 mg doxycycline twice a day, which resulted in a resolution of active lesions. The patient did have postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California, and Mina Zulal, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Hamburg, Germany. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Beutler et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):533-43.

2. Kim et al. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):891-7.

3. Mufti et al. JAAD Int. 2021 Apr 10;3:79-87.

It is characterized by pruritic, erythematous papules, papulovesicles, and vesicles that appear in a reticular pattern, most commonly on the trunk. The lesions are typically followed by postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (PIH).

Although PP has been described in people of all races, ages, and sexes, it is predominantly observed in Japan, often in female young adults. Triggers may include a ketogenic diet, diabetes mellitus, and pregnancy. Friction and contact allergic reactions to chrome or nickel have been proposed as exogenous trigger factors. Individual cases of Sjögren’s syndrome, Helicobacter pylori infections, and adult Still syndrome have also been associated with recurrent eruptions.

The diagnosis of PP is made both clinically and by biopsy. The histological features vary according to the stage of the disease. In early-stage disease, superficial and perivascular infiltration of neutrophils are prominent. Later stages are characterized by spongiosis and necrotic keratinocytes.

The first-line therapy for prurigo pigmentosa is oral minocycline. However, for some patients, doxycycline, macrolide antibiotics, or dapsone may be indicated. Adding carbohydrates to a keto diet may be helpful. In this patient, a punch biopsy was performed, which revealed an interface dermatitis with eosinophils and neutrophils, consistent with prurigo pigmentosa. The cause of her PP remains idiopathic. She was treated with 100 mg doxycycline twice a day, which resulted in a resolution of active lesions. The patient did have postinflammatory hyperpigmentation.

This case and photo were submitted by Brooke Resh Sateesh, MD, of San Diego Family Dermatology, San Diego, California, and Mina Zulal, University Medical Center Hamburg-Eppendorf (UKE), Hamburg, Germany. Dr. Bilu Martin edited the column.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Beutler et al. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2015 Dec;16(6):533-43.

2. Kim et al. J Dermatol. 2012 Nov;39(11):891-7.

3. Mufti et al. JAAD Int. 2021 Apr 10;3:79-87.

‘Stop pretending’ there’s a magic formula to weight loss

Is there a diet or weight-loss program out there that doesn’t work for those who stick with it during its first 12 weeks?

Truly, the world’s most backwards, upside-down, anti-science, nonsensical diets work over the short haul, fueled by the fact that short-term suffering for weight loss is a skill set that humanity has assiduously cultivated for at least the past 100 years. We’re really good at it!

It’s the keeping the weight off, though, that’s the hitch. Which leads me to the question, why are medical journals, even preeminent nonpredatory ones, publishing 12-week weight-loss program studies as if they have value? And does anyone truly imagine that after over 100 years of trying, there’ll be a short-term diet or program that’ll have the durable, reproducible results that no other short-term diet or program ever has?

Take this study published by Obesity: “Pragmatic implementation of a fully automated online obesity treatment in primary care.” It details a 12-week online, automated, weight-loss program that led completers to lose the roughly 5% of weight that many diets and programs see lost over their first 12 weeks. By its description, aside from its automated provision, the program sounds like pretty much the same boilerplate weight management advice and recommendations that haven’t been shown to lead large numbers of people to sustain long-term weight loss.

Participants were provided with weekly lessons which no doubt in some manner told them that high-calorie foods had high numbers of calories and should be minimized, along with other weight-loss secrets. Users were to upload weekly self-monitored weight, energy intake, and exercise minutes and were told to use a food diary. Their goal was losing 10% of their body weight by consuming 1,200-1,500 calories per day if they weighed less than 250 pounds (113 kg) and 1,500-1,800 calories if they weighed more than 250 pounds, while also telling them to aim for 200 minutes per week of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

What was found was wholly unsurprising. Perhaps speaking to the tremendous and wide-ranging degrees of privilege that are required to prioritize intentional behavior change in the name of health, 79% of those who were given a prescription for the program either didn’t start it or stopped it before the end of the first week.

Of those who actually started the program and completed more than 1 week, despite having been selected as appropriate and interested participants by their physicians, only 20% watched all of the automated programs’ video lessons while only 32% actually bothered to submit all 12 weeks of weight data. Of course, the authors found that those who watched the greatest number of videos and submitted the most self-reported weights lost more weight and ascribed that loss to the program. What the authors did not entertain was the possibility that those who weren’t losing weight, or who were gaining, might simply be less inclined to continue with a program that wasn’t leading them to their desired outcomes or to want to submit their lack of loss or gains.

Short-term weight-loss studies help no one and when, as in this case, the outcomes aren’t even mediocre, and the completion and engagement rates are terrible, the study is still presented as significant and important. This bolsters the harmful stereotype that weight management is achievable by way of simple messages and generic goals. It suggests that it’s individuals who fail programs by not trying hard enough and that those who do, or who want it the most, will succeed. It may also lead patients and clinicians to second-guess the use of antiobesity medications, the current generation of which lead to far greater weight loss and reproducibility than any behavioral program or diet ever has.

The good news here at least is that the small percentage of participants who made it through this program’s 12 weeks are being randomly assigned to differing 9-month maintenance programs which at least will then lead to a 1-year analysis on the completers.

Why this study was published now, rather than pushed until the 1-year data were available, speaks to the pervasiveness of the toxic weight-biased notion that simple education will overcome the physiology forged over millions of years of extreme dietary insecurity.

Our food environment is a veritable floodplain of hyperpalatable foods, and social determinants of health make intentional behavior change in the name of health an unattainable luxury for a huge swath of the population.

Dr. Freedhoff is an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute. He reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Bariatric Medical Institute and Constant Health and receiving research grants from Novo Nordisk. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is there a diet or weight-loss program out there that doesn’t work for those who stick with it during its first 12 weeks?

Truly, the world’s most backwards, upside-down, anti-science, nonsensical diets work over the short haul, fueled by the fact that short-term suffering for weight loss is a skill set that humanity has assiduously cultivated for at least the past 100 years. We’re really good at it!

It’s the keeping the weight off, though, that’s the hitch. Which leads me to the question, why are medical journals, even preeminent nonpredatory ones, publishing 12-week weight-loss program studies as if they have value? And does anyone truly imagine that after over 100 years of trying, there’ll be a short-term diet or program that’ll have the durable, reproducible results that no other short-term diet or program ever has?

Take this study published by Obesity: “Pragmatic implementation of a fully automated online obesity treatment in primary care.” It details a 12-week online, automated, weight-loss program that led completers to lose the roughly 5% of weight that many diets and programs see lost over their first 12 weeks. By its description, aside from its automated provision, the program sounds like pretty much the same boilerplate weight management advice and recommendations that haven’t been shown to lead large numbers of people to sustain long-term weight loss.

Participants were provided with weekly lessons which no doubt in some manner told them that high-calorie foods had high numbers of calories and should be minimized, along with other weight-loss secrets. Users were to upload weekly self-monitored weight, energy intake, and exercise minutes and were told to use a food diary. Their goal was losing 10% of their body weight by consuming 1,200-1,500 calories per day if they weighed less than 250 pounds (113 kg) and 1,500-1,800 calories if they weighed more than 250 pounds, while also telling them to aim for 200 minutes per week of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

What was found was wholly unsurprising. Perhaps speaking to the tremendous and wide-ranging degrees of privilege that are required to prioritize intentional behavior change in the name of health, 79% of those who were given a prescription for the program either didn’t start it or stopped it before the end of the first week.

Of those who actually started the program and completed more than 1 week, despite having been selected as appropriate and interested participants by their physicians, only 20% watched all of the automated programs’ video lessons while only 32% actually bothered to submit all 12 weeks of weight data. Of course, the authors found that those who watched the greatest number of videos and submitted the most self-reported weights lost more weight and ascribed that loss to the program. What the authors did not entertain was the possibility that those who weren’t losing weight, or who were gaining, might simply be less inclined to continue with a program that wasn’t leading them to their desired outcomes or to want to submit their lack of loss or gains.

Short-term weight-loss studies help no one and when, as in this case, the outcomes aren’t even mediocre, and the completion and engagement rates are terrible, the study is still presented as significant and important. This bolsters the harmful stereotype that weight management is achievable by way of simple messages and generic goals. It suggests that it’s individuals who fail programs by not trying hard enough and that those who do, or who want it the most, will succeed. It may also lead patients and clinicians to second-guess the use of antiobesity medications, the current generation of which lead to far greater weight loss and reproducibility than any behavioral program or diet ever has.

The good news here at least is that the small percentage of participants who made it through this program’s 12 weeks are being randomly assigned to differing 9-month maintenance programs which at least will then lead to a 1-year analysis on the completers.

Why this study was published now, rather than pushed until the 1-year data were available, speaks to the pervasiveness of the toxic weight-biased notion that simple education will overcome the physiology forged over millions of years of extreme dietary insecurity.

Our food environment is a veritable floodplain of hyperpalatable foods, and social determinants of health make intentional behavior change in the name of health an unattainable luxury for a huge swath of the population.

Dr. Freedhoff is an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute. He reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Bariatric Medical Institute and Constant Health and receiving research grants from Novo Nordisk. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is there a diet or weight-loss program out there that doesn’t work for those who stick with it during its first 12 weeks?

Truly, the world’s most backwards, upside-down, anti-science, nonsensical diets work over the short haul, fueled by the fact that short-term suffering for weight loss is a skill set that humanity has assiduously cultivated for at least the past 100 years. We’re really good at it!

It’s the keeping the weight off, though, that’s the hitch. Which leads me to the question, why are medical journals, even preeminent nonpredatory ones, publishing 12-week weight-loss program studies as if they have value? And does anyone truly imagine that after over 100 years of trying, there’ll be a short-term diet or program that’ll have the durable, reproducible results that no other short-term diet or program ever has?

Take this study published by Obesity: “Pragmatic implementation of a fully automated online obesity treatment in primary care.” It details a 12-week online, automated, weight-loss program that led completers to lose the roughly 5% of weight that many diets and programs see lost over their first 12 weeks. By its description, aside from its automated provision, the program sounds like pretty much the same boilerplate weight management advice and recommendations that haven’t been shown to lead large numbers of people to sustain long-term weight loss.

Participants were provided with weekly lessons which no doubt in some manner told them that high-calorie foods had high numbers of calories and should be minimized, along with other weight-loss secrets. Users were to upload weekly self-monitored weight, energy intake, and exercise minutes and were told to use a food diary. Their goal was losing 10% of their body weight by consuming 1,200-1,500 calories per day if they weighed less than 250 pounds (113 kg) and 1,500-1,800 calories if they weighed more than 250 pounds, while also telling them to aim for 200 minutes per week of moderate- to vigorous-intensity physical activity.

What was found was wholly unsurprising. Perhaps speaking to the tremendous and wide-ranging degrees of privilege that are required to prioritize intentional behavior change in the name of health, 79% of those who were given a prescription for the program either didn’t start it or stopped it before the end of the first week.

Of those who actually started the program and completed more than 1 week, despite having been selected as appropriate and interested participants by their physicians, only 20% watched all of the automated programs’ video lessons while only 32% actually bothered to submit all 12 weeks of weight data. Of course, the authors found that those who watched the greatest number of videos and submitted the most self-reported weights lost more weight and ascribed that loss to the program. What the authors did not entertain was the possibility that those who weren’t losing weight, or who were gaining, might simply be less inclined to continue with a program that wasn’t leading them to their desired outcomes or to want to submit their lack of loss or gains.

Short-term weight-loss studies help no one and when, as in this case, the outcomes aren’t even mediocre, and the completion and engagement rates are terrible, the study is still presented as significant and important. This bolsters the harmful stereotype that weight management is achievable by way of simple messages and generic goals. It suggests that it’s individuals who fail programs by not trying hard enough and that those who do, or who want it the most, will succeed. It may also lead patients and clinicians to second-guess the use of antiobesity medications, the current generation of which lead to far greater weight loss and reproducibility than any behavioral program or diet ever has.

The good news here at least is that the small percentage of participants who made it through this program’s 12 weeks are being randomly assigned to differing 9-month maintenance programs which at least will then lead to a 1-year analysis on the completers.

Why this study was published now, rather than pushed until the 1-year data were available, speaks to the pervasiveness of the toxic weight-biased notion that simple education will overcome the physiology forged over millions of years of extreme dietary insecurity.

Our food environment is a veritable floodplain of hyperpalatable foods, and social determinants of health make intentional behavior change in the name of health an unattainable luxury for a huge swath of the population.

Dr. Freedhoff is an associate professor of family medicine at the University of Ottawa and medical director of the Bariatric Medical Institute. He reported serving as a director, officer, partner, employee, adviser, consultant, or trustee for Bariatric Medical Institute and Constant Health and receiving research grants from Novo Nordisk. A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Understanding the relationship between life satisfaction and cognitive decline

Every day, we depend on our working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed abilities to optimize productivity, interpersonal interactions, and psychological wellbeing. These cognitive functioning indices relate closely with academic and work performance, managing emotions, physical fitness, and a sense of fulfillment in personal and work relationships. They are linked intimately to complex cognitive skills (van Dijk et al., 2020). It is thus imperative to identify modifiable predictors of cognitive functioning in the brain to protect against aging-related cognitive decline and maximize the quality of life.

A decline in life satisfaction can worsen cognitive functioning over long periods via lifestyle factors (e.g., suboptimal diet and nutrition, lack of exercise) (Ratigan et al., 2016). Inadequate engagement in these health-enhancing pursuits could build up inflammation in EF-linked brain areas, thus negatively impacting cognitive functioning in adulthood (Grant et al., 2009). Possible pathways include long-term wear and tear of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and brain regions linked to executive functioning (Zainal and Newman, 2022a). These processes may deteriorate working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed across time.

Similarly, it is plausible that a reduction in cognitive functioning may lead to a long-term decrease in life satisfaction. Working memory, processing speed, spatial cognition, and related capacities are essential to meaningful activities and feelings of gratification in personal and professional relationships and other spheres of health throughout life (Baumeister et al., 2007). These cognitive functioning markers safeguard against reduced life satisfaction by facilitating effective problem-solving, and choices (Swanson and Fung, 2016). For example, stronger working memory, processing speed, and related domains coincided with better tolerance for stress and trading off immediate rewards for long-term values and life goals (Hofmann et al., 2012). Therefore, reduction in cognitive functioning abilities could precede a future decline in life satisfaction.

Nonetheless, the literature on this topic has several limitations. Most of the studies have been cross-sectional (i.e., across a single time-point) and thus do not permit inferences between cause and effect (e.g., Toh et al., 2020). Also, most studies used statistical methods that did not differentiate between between-person (trait-like individual differences) and within-person (state-like) relations. Distinguishing within- and between-person relations is necessary because they may vary in magnitude and direction. The preceding theories emphasize change-to-future change relations within persons rather than between persons (Wright and Woods, 2020).

Clinical implications

Our recent work (Zainal and Newman, 2022b) added to the literature by using an advanced statistical method to determine the relations between change in life satisfaction and future change in cognitive functioning domains within persons. The choice of an advanced statistical technique minimizes biases due to the passage of time and assessment unreliability. It also adjusts for between-person effects (Klopack and Wickrama, 2020). Improving understanding of the within-person factors leading to the deterioration of cognitive functioning and life satisfaction is crucial given the rising rates of psychiatric and neurocognitive illnesses (Cui et al., 2020). Identifying these changeable risk factors can optimize prevention, early detection, and treatment approaches.

Specifically, we analyzed the publicly available Swedish Adoption/Twin Study of Aging (SATSA) dataset (Petkus et al., 2017). Their dataset comprised 520 middle- to older-aged twin adults without dementia. Participants provided data across 23 years with five time points. Each time lag ranged from 3 to 11 years. The analyses demonstrated that greater decreases in life satisfaction predicted larger future declines in processing speed, verbal working memory, and spatial cognition. Moreover, declines in verbal working memory and processing speed predicted a reduction in life satisfaction. However, change in spatial awareness did not predict change in life satisfaction.

Our study offers multiple theoretical perspectives. Scar theories propose that decreased life satisfaction and related mental health problems can compromise working memory, processing speed, and spatial cognition in the long term. This scarring process occurs through the buildup of allostatic load, such as increased biomarkers of chronic stress (e.g., cortisol) and inflammation (e.g., interleukin-6, C-reactive protein) (Fancourt and Steptoe, 2020; Zainal and Newman, 2021a). Also, findings suggest the importance of executive functioning domains to attain desired milestones and aspirations to enhance a sense of fulfillment (Baddeley, 2013; Toh and Yang, 2020). Reductions in these cognitive functioning capacities could, over time, adversely affect the ability to engage in daily living activities and manage negative moods.

Limitations of our study include the lack of a multiple-assessment approach to measuring diverse cognitive functioning domains. Also, the absence of cognitive self-reports is a shortcoming since perceived cognitive difficulties might not align with performance on cognitive tests. Relatedly, future studies should administer cognitive tests that parallel and transfer to everyday tasks. However, our study’s strengths include the robust findings across different intervals between study waves, advanced statistics, and the large sample size.

If future studies replicate a similar pattern of results, the clinical applications of this study merit attention. Mindfulness-based interventions can promote working memory, sustained awareness, and spatial cognition or protect against cognitive decline (Jha et al., 2019; Zainal and Newman, 2021b). Further, clinical science can profit from exploring cognitive-behavioral therapies to improve adults’ cognitive function or life satisfaction (Sok et al., 2021).

Dr. Zainal recently accepted a 2-year postdoctoral research associate position at Harvard Medical School, Boston, starting in summer 2022. She received her Ph.D. from Pennsylvania State University, University Park, and completed a predoctoral clinical fellowship at the HMS-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital – Cognitive Behavioral Scientist Track. Her research interests focus on how executive functioning, social cognition, and cognitive-behavioral strategies link to the etiology, maintenance, and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. Dr. Newman is a professor of psychology and psychiatry, and the director of the Center for the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression, at Pennsylvania State University. She has conducted basic and applied research on anxiety disorders and depression and has published over 200 papers on these topics.

Sources

Baddeley A. Working memory and emotion: Ruminations on a theory of depression. Rev Gen Psychol. 2013;17(1):20-7. doi: 10.1037/a0030029.

Baumeister RF et al. “Self-regulation and the executive function: The self as controlling agent,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, 2nd ed. (pp. 516-39). The Guilford Press: New York, 2007.

Cui L et al. Prevalence of alzheimer’s disease and parkinson’s disease in China: An updated systematical analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 Dec 21;12:603854. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.603854.

Fancourt D and Steptoe A. The longitudinal relationship between changes in wellbeing and inflammatory markers: Are associations independent of depression? Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Jan;83:146-52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.10.004.

Grant N et al. The relationship between life satisfaction and health behavior: A cross-cultural analysis of young adults. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16(3):259-68. doi: 10.1007/s12529-009-9032-x.

Hofmann W et al. Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012 Mar;16(3):174-80. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.006.

Jha AP et al. Bolstering cognitive resilience via train-the-trainer delivery of mindfulness training in applied high-demand settings. Mindfulness. 2019;11(3):683-97. doi: 10.1007/s12671-019-01284-7.

Klopack ET and Wickrama K. Modeling latent change score analysis and extensions in Mplus: A practical guide for researchers. Struct Equ Modeling. 2020;27(1):97-110. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2018.1562929.

Petkus AJ et al. Temporal dynamics of cognitive performance and anxiety across older adulthood. Psychol Aging. 2017 May;32(3):278-92. doi: 10.1037/pag0000164.

Ratigan A et al. Sex differences in the association of physical function and cognitive function with life satisfaction in older age: The Rancho Bernardo Study. Maturitas. 2016 Jul;89:29-35. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.04.007.

Sok S et al. Effects of cognitive/exercise dual-task program on the cognitive function, health status, depression, and life satisfaction of the elderly living in the community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 24;18(15):7848. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157848.

Swanson HL and Fung W. Working memory components and problem-solving accuracy: Are there multiple pathways? J Educ Psychol. 2016;108(8):1153-77. doi: 10.1037/edu0000116.

Toh WX and Yang H. Executive function moderates the effect of reappraisal on life satisfaction: A latent variable analysis. Emotion. 2020;22(3):554-71. doi: 10.1037/emo0000907.

Toh WX et al. Executive function and subjective wellbeing in middle and late adulthood. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 Jun 2;75(6):e69-e77. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz006.

van Dijk DM, et al. Cognitive functioning, sleep quality, and work performance in non-clinical burnout: The role of working memory. PLoS One. 2020 Apr 23;15(4):e0231906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231906.

Wright AGC and Woods WC. Personalized models of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2020 May 7;16:49-74. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-102419-125032.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2021a). Depression and worry symptoms predict future executive functioning impairment via inflammation. Psychol Med. 2021 Mar 3;1-11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000398.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2021b). Mindfulness enhances cognitive functioning: A meta-analysis of 111 randomized controlled trials. PsyArXiv Preprints. 2021 May 11. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/vzxw7.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2022a). Inflammation mediates depression and generalized anxiety symptoms predicting executive function impairment after 18 years. J Affect Disord. 2022 Jan 1;296:465-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.077.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2022b). Life satisfaction prevents decline in working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed: Latent change score analyses across 23 years. Eur Psychiatry. 2022 Apr 19;65(1):1-55. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.19.

Every day, we depend on our working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed abilities to optimize productivity, interpersonal interactions, and psychological wellbeing. These cognitive functioning indices relate closely with academic and work performance, managing emotions, physical fitness, and a sense of fulfillment in personal and work relationships. They are linked intimately to complex cognitive skills (van Dijk et al., 2020). It is thus imperative to identify modifiable predictors of cognitive functioning in the brain to protect against aging-related cognitive decline and maximize the quality of life.

A decline in life satisfaction can worsen cognitive functioning over long periods via lifestyle factors (e.g., suboptimal diet and nutrition, lack of exercise) (Ratigan et al., 2016). Inadequate engagement in these health-enhancing pursuits could build up inflammation in EF-linked brain areas, thus negatively impacting cognitive functioning in adulthood (Grant et al., 2009). Possible pathways include long-term wear and tear of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and brain regions linked to executive functioning (Zainal and Newman, 2022a). These processes may deteriorate working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed across time.

Similarly, it is plausible that a reduction in cognitive functioning may lead to a long-term decrease in life satisfaction. Working memory, processing speed, spatial cognition, and related capacities are essential to meaningful activities and feelings of gratification in personal and professional relationships and other spheres of health throughout life (Baumeister et al., 2007). These cognitive functioning markers safeguard against reduced life satisfaction by facilitating effective problem-solving, and choices (Swanson and Fung, 2016). For example, stronger working memory, processing speed, and related domains coincided with better tolerance for stress and trading off immediate rewards for long-term values and life goals (Hofmann et al., 2012). Therefore, reduction in cognitive functioning abilities could precede a future decline in life satisfaction.

Nonetheless, the literature on this topic has several limitations. Most of the studies have been cross-sectional (i.e., across a single time-point) and thus do not permit inferences between cause and effect (e.g., Toh et al., 2020). Also, most studies used statistical methods that did not differentiate between between-person (trait-like individual differences) and within-person (state-like) relations. Distinguishing within- and between-person relations is necessary because they may vary in magnitude and direction. The preceding theories emphasize change-to-future change relations within persons rather than between persons (Wright and Woods, 2020).

Clinical implications

Our recent work (Zainal and Newman, 2022b) added to the literature by using an advanced statistical method to determine the relations between change in life satisfaction and future change in cognitive functioning domains within persons. The choice of an advanced statistical technique minimizes biases due to the passage of time and assessment unreliability. It also adjusts for between-person effects (Klopack and Wickrama, 2020). Improving understanding of the within-person factors leading to the deterioration of cognitive functioning and life satisfaction is crucial given the rising rates of psychiatric and neurocognitive illnesses (Cui et al., 2020). Identifying these changeable risk factors can optimize prevention, early detection, and treatment approaches.

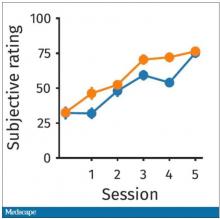

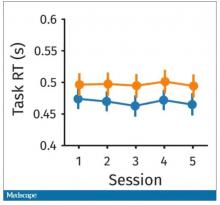

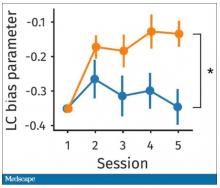

Specifically, we analyzed the publicly available Swedish Adoption/Twin Study of Aging (SATSA) dataset (Petkus et al., 2017). Their dataset comprised 520 middle- to older-aged twin adults without dementia. Participants provided data across 23 years with five time points. Each time lag ranged from 3 to 11 years. The analyses demonstrated that greater decreases in life satisfaction predicted larger future declines in processing speed, verbal working memory, and spatial cognition. Moreover, declines in verbal working memory and processing speed predicted a reduction in life satisfaction. However, change in spatial awareness did not predict change in life satisfaction.

Our study offers multiple theoretical perspectives. Scar theories propose that decreased life satisfaction and related mental health problems can compromise working memory, processing speed, and spatial cognition in the long term. This scarring process occurs through the buildup of allostatic load, such as increased biomarkers of chronic stress (e.g., cortisol) and inflammation (e.g., interleukin-6, C-reactive protein) (Fancourt and Steptoe, 2020; Zainal and Newman, 2021a). Also, findings suggest the importance of executive functioning domains to attain desired milestones and aspirations to enhance a sense of fulfillment (Baddeley, 2013; Toh and Yang, 2020). Reductions in these cognitive functioning capacities could, over time, adversely affect the ability to engage in daily living activities and manage negative moods.

Limitations of our study include the lack of a multiple-assessment approach to measuring diverse cognitive functioning domains. Also, the absence of cognitive self-reports is a shortcoming since perceived cognitive difficulties might not align with performance on cognitive tests. Relatedly, future studies should administer cognitive tests that parallel and transfer to everyday tasks. However, our study’s strengths include the robust findings across different intervals between study waves, advanced statistics, and the large sample size.

If future studies replicate a similar pattern of results, the clinical applications of this study merit attention. Mindfulness-based interventions can promote working memory, sustained awareness, and spatial cognition or protect against cognitive decline (Jha et al., 2019; Zainal and Newman, 2021b). Further, clinical science can profit from exploring cognitive-behavioral therapies to improve adults’ cognitive function or life satisfaction (Sok et al., 2021).

Dr. Zainal recently accepted a 2-year postdoctoral research associate position at Harvard Medical School, Boston, starting in summer 2022. She received her Ph.D. from Pennsylvania State University, University Park, and completed a predoctoral clinical fellowship at the HMS-affiliated Massachusetts General Hospital – Cognitive Behavioral Scientist Track. Her research interests focus on how executive functioning, social cognition, and cognitive-behavioral strategies link to the etiology, maintenance, and treatment of anxiety and depressive disorders. Dr. Newman is a professor of psychology and psychiatry, and the director of the Center for the Treatment of Anxiety and Depression, at Pennsylvania State University. She has conducted basic and applied research on anxiety disorders and depression and has published over 200 papers on these topics.

Sources

Baddeley A. Working memory and emotion: Ruminations on a theory of depression. Rev Gen Psychol. 2013;17(1):20-7. doi: 10.1037/a0030029.

Baumeister RF et al. “Self-regulation and the executive function: The self as controlling agent,” in Social Psychology: Handbook of Basic Principles, 2nd ed. (pp. 516-39). The Guilford Press: New York, 2007.

Cui L et al. Prevalence of alzheimer’s disease and parkinson’s disease in China: An updated systematical analysis. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 Dec 21;12:603854. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2020.603854.

Fancourt D and Steptoe A. The longitudinal relationship between changes in wellbeing and inflammatory markers: Are associations independent of depression? Brain Behav Immun. 2020 Jan;83:146-52. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2019.10.004.

Grant N et al. The relationship between life satisfaction and health behavior: A cross-cultural analysis of young adults. Int J Behav Med. 2009;16(3):259-68. doi: 10.1007/s12529-009-9032-x.

Hofmann W et al. Executive functions and self-regulation. Trends Cogn Sci. 2012 Mar;16(3):174-80. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.01.006.

Jha AP et al. Bolstering cognitive resilience via train-the-trainer delivery of mindfulness training in applied high-demand settings. Mindfulness. 2019;11(3):683-97. doi: 10.1007/s12671-019-01284-7.

Klopack ET and Wickrama K. Modeling latent change score analysis and extensions in Mplus: A practical guide for researchers. Struct Equ Modeling. 2020;27(1):97-110. doi: 10.1080/10705511.2018.1562929.

Petkus AJ et al. Temporal dynamics of cognitive performance and anxiety across older adulthood. Psychol Aging. 2017 May;32(3):278-92. doi: 10.1037/pag0000164.

Ratigan A et al. Sex differences in the association of physical function and cognitive function with life satisfaction in older age: The Rancho Bernardo Study. Maturitas. 2016 Jul;89:29-35. doi: 10.1016/j.maturitas.2016.04.007.

Sok S et al. Effects of cognitive/exercise dual-task program on the cognitive function, health status, depression, and life satisfaction of the elderly living in the community. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021 Jul 24;18(15):7848. doi: 10.3390/ijerph18157848.

Swanson HL and Fung W. Working memory components and problem-solving accuracy: Are there multiple pathways? J Educ Psychol. 2016;108(8):1153-77. doi: 10.1037/edu0000116.

Toh WX and Yang H. Executive function moderates the effect of reappraisal on life satisfaction: A latent variable analysis. Emotion. 2020;22(3):554-71. doi: 10.1037/emo0000907.

Toh WX et al. Executive function and subjective wellbeing in middle and late adulthood. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2020 Jun 2;75(6):e69-e77. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbz006.

van Dijk DM, et al. Cognitive functioning, sleep quality, and work performance in non-clinical burnout: The role of working memory. PLoS One. 2020 Apr 23;15(4):e0231906. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0231906.

Wright AGC and Woods WC. Personalized models of psychopathology. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2020 May 7;16:49-74. doi: 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-102419-125032.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2021a). Depression and worry symptoms predict future executive functioning impairment via inflammation. Psychol Med. 2021 Mar 3;1-11. doi: 10.1017/S0033291721000398.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2021b). Mindfulness enhances cognitive functioning: A meta-analysis of 111 randomized controlled trials. PsyArXiv Preprints. 2021 May 11. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/vzxw7.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2022a). Inflammation mediates depression and generalized anxiety symptoms predicting executive function impairment after 18 years. J Affect Disord. 2022 Jan 1;296:465-75. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2021.08.077.

Zainal NH and Newman MG. (2022b). Life satisfaction prevents decline in working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed: Latent change score analyses across 23 years. Eur Psychiatry. 2022 Apr 19;65(1):1-55. doi: 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2022.19.

Every day, we depend on our working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed abilities to optimize productivity, interpersonal interactions, and psychological wellbeing. These cognitive functioning indices relate closely with academic and work performance, managing emotions, physical fitness, and a sense of fulfillment in personal and work relationships. They are linked intimately to complex cognitive skills (van Dijk et al., 2020). It is thus imperative to identify modifiable predictors of cognitive functioning in the brain to protect against aging-related cognitive decline and maximize the quality of life.

A decline in life satisfaction can worsen cognitive functioning over long periods via lifestyle factors (e.g., suboptimal diet and nutrition, lack of exercise) (Ratigan et al., 2016). Inadequate engagement in these health-enhancing pursuits could build up inflammation in EF-linked brain areas, thus negatively impacting cognitive functioning in adulthood (Grant et al., 2009). Possible pathways include long-term wear and tear of the hypothalamic-pituitary axis and brain regions linked to executive functioning (Zainal and Newman, 2022a). These processes may deteriorate working memory, spatial cognition, and processing speed across time.

Similarly, it is plausible that a reduction in cognitive functioning may lead to a long-term decrease in life satisfaction. Working memory, processing speed, spatial cognition, and related capacities are essential to meaningful activities and feelings of gratification in personal and professional relationships and other spheres of health throughout life (Baumeister et al., 2007). These cognitive functioning markers safeguard against reduced life satisfaction by facilitating effective problem-solving, and choices (Swanson and Fung, 2016). For example, stronger working memory, processing speed, and related domains coincided with better tolerance for stress and trading off immediate rewards for long-term values and life goals (Hofmann et al., 2012). Therefore, reduction in cognitive functioning abilities could precede a future decline in life satisfaction.

Nonetheless, the literature on this topic has several limitations. Most of the studies have been cross-sectional (i.e., across a single time-point) and thus do not permit inferences between cause and effect (e.g., Toh et al., 2020). Also, most studies used statistical methods that did not differentiate between between-person (trait-like individual differences) and within-person (state-like) relations. Distinguishing within- and between-person relations is necessary because they may vary in magnitude and direction. The preceding theories emphasize change-to-future change relations within persons rather than between persons (Wright and Woods, 2020).

Clinical implications