User login

Telemedicine in primary care

How to effectively utilize this tool

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

How to effectively utilize this tool

How to effectively utilize this tool

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

By now it is well known that the COVID-19 pandemic has significantly disrupted primary care. Office visits and revenues have precipitously dropped as physicians and patients alike fear in-person visits may increase their risks of contracting the virus. However, telemedicine has emerged as a lifeline of sorts for many practices, enabling them to conduct visits and maintain contact with patients.

Telemedicine is likely to continue to serve as a tool for primary care providers to improve access to convenient, cost-effective, high-quality care after the pandemic. Another benefit of telemedicine is it can help maintain a portion of a practice’s revenue stream for physicians during uncertain times.

Indeed, the nation has seen recent progress toward telemedicine parity, which refers to the concept of reimbursing providers’ telehealth visits at the same rates as similar in-person visits.

A challenge to adopting telemedicine is that it calls for adjusting established workflows for in-person encounters. A practice cannot simply replicate in-person processes to work for telehealth. While both in-person and virtual visits require adherence to HIPAA, for example, how you actually protect patient privacy will call for different measures. Harking back to the early days of EMR implementation, one does not need to like the telemedicine platform or process, but come to terms with the fact that it is a tool that is here to stay to deliver patient care.

Treat your practice like a laboratory

Adoption may vary between practices depending on many factors, including clinicians’ comfort with technology, clinical tolerance and triage rules for nontouch encounters, state regulations, and more. Every provider group should begin experimenting with telemedicine in specific ways that make sense for them.

One physician may practice telemedicine full-time while the rest abstain, or perhaps the practice prefers to offer telemedicine services during specific hours on specific days. Don’t be afraid to start slowly when you’re trying something new – but do get started with telehealth. It will increasingly be a mainstream medium and more patients will come to expect it.

Train the entire team

Many primary care practices do not enjoy the resources of an information technology team, so all team members essentially need to learn the new skill of telemedicine usage, in addition to assisting patients. That can’t happen without staff buy-in, so it is essential that everyone from the office manager to medical assistants have the training they need to make the technology work. Juggling schedules for telehealth and in-office, activating an account through email, starting and joining a telehealth meeting, and preparing a patient for a visit are just a handful of basic tasks your staff should be trained to do to contribute to the successful integration of telehealth.

Educate and encourage patients to use telehealth

While unfamiliarity with technology may represent a roadblock for some patients, others resist telemedicine simply because no one has explained to them why it’s so important and the benefits it can hold for them. Education and communication are critical, including the sometimes painstaking work of slowly walking patients through the process of performing important functions on the telemedicine app. By providing them with some friendly coaching, patients won’t feel lost or abandoned during what for some may be an unfamiliar and frustrating process.

Manage more behavioral health

Different states and health plans incentivize primary practices for integrating behavioral health into their offerings. Rather than dismiss this addition to your own practice as too cumbersome to take on, I would recommend using telehealth to expand behavioral health care services.

If your practice is working toward a team-based, interdisciplinary approach to care delivery, behavioral health is a critical component. While other elements of this “whole person” health care may be better suited for an office visit, the vast majority of behavioral health services can be delivered virtually.

To decide if your patient may benefit from behavioral health care, the primary care provider (PCP) can conduct a screening via telehealth. Once the screening is complete, the PCP can discuss results and refer the patient to a mental health professional – all via telehealth. While patients may be reluctant to receive behavioral health treatment, perhaps because of stigma or inexperience, they may appreciate the telemedicine option as they can remain in the comfort and familiarity of their homes.

Collaborative Care is both an in-person and virtual model that allows PCP practices to offer behavioral health services in a cost effective way by utilizing a psychiatrist as a “consultant” to the practice as opposed to hiring a full-time psychiatrist. All services within the Collaborative Care Model can be offered via telehealth, and all major insurance providers reimburse primary care providers for delivering Collaborative Care.

When PCPs provide behavioral health treatment as an “extension” of the primary care service offerings, the stigma is reduced and more patients are willing to accept the care they need.

Many areas of the country suffer from a lack of access to behavioral health specialists. In rural counties, for example, the nearest therapist may be located over an hour away. By integrating behavioral telehealth services into your practice’s offerings, you can remove geographic and transportation obstacles to care for your patient population.

Doing this can lead to providing more culturally competent care. It’s important that you’re able to offer mental health services to your patients from a professional with a similar ethnic or racial background. Language barriers and cultural differences may limit a provider’s ability to treat a patient, particularly if the patient faces health disparities related to race or ethnicity. If your practice needs to look outside of your community to tap into a more diverse pool of providers to better meet your patients’ needs, telehealth makes it easier to do that.

Adopting telemedicine for consultative patient visits offers primary care a path toward restoring patient volume and hope for a postpandemic future.

Mark Stephan, MD, is chief medical officer at Equality Health, a whole-health delivery system. He practiced family medicine for 19 years, including hospital medicine and obstetrics in rural and urban settings. Dr. Stephan has no conflicts related to the content of this piece.

Chronicles of cancer: A history of mammography, part 1

Technological imperatives

The history of mammography provides a powerful example of the connection between social factors and the rise of a medical technology. It is also an object lesson in the profound difficulties that the medical community faces when trying to evaluate and embrace new discoveries in such a complex area as cancer diagnosis and treatment, especially when tied to issues of sex-based bias and gender identity. Given its profound ties to women’s lives and women’s bodies, mammography holds a unique place in the history of cancer. Part 1 will examine the technological imperatives driving mammography forward, and part 2 will address the social factors that promoted and inhibited the developing technology.

All that glitters

Innovations in technology have contributed so greatly to the progress of medical science in saving and improving patients’ lives that the lure of new technology and the desire to see it succeed and to embrace it has become profound.

In a debate on the adoption of new technologies, Michael Rosen, MD, a surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, pointed out the inherent risks in the life cycle of medical technology: “The stages of surgical innovation have been well described as moving from the generation of a hypothesis with an early promising report to being accepted conclusively as a new standard without formal testing. As the life cycle continues and comparative effectiveness data begin to emerge slowly through appropriately designed trials, the procedure or device is often ultimately abandoned.”1

The history of mammography bears out this grim warning in example after example as an object lesson, revealing not only the difficulties involved in the development of new medical technologies, but also the profound problems involved in validating the effectiveness and appropriateness of a new technology from its inception to the present.

A modern failure?

In fact, one of the more modern developments in mammography technology – digital imaging – has recently been called into question with regard to its effectiveness in saving lives, even as the technology continues to spread throughout the medical community.

A recent meta-analysis has shown that there is little or no improvement in outcomes of breast cancer screening when using digital analysis and screening mammograms vs. traditional film recording.

The meta-analysis assessed 24 studies with a combined total of 16,583,743 screening examinations (10,968,843 film and 5,614,900 digital). The study found that the difference in cancer detection rate using digital rather than film screening showed an increase of only 0.51 detections per 1,000 screens.

The researchers concluded “that while digital mammography is beneficial for medical facilities due to easier storage and handling of images, these results suggest the transition from film to digital mammography has not resulted in health benefits for screened women.”2

In fact, the researchers added that “This analysis reinforces the need to carefully evaluate effects of future changes in technology, such as tomosynthesis, to ensure new technology leads to improved health outcomes and beyond technical gains.”2

None of the nine main randomized clinical trials that were used to determine the effectiveness of mammography screening from the 1960s to the 1990s used digital or 3-D digital mammography (digital breast tomosynthesis or DBT). The earliest trial used direct-exposure film mammography and the others relied upon screen-film mammography.3 And yet the assumptions of the validity of the new digital technologies were predicated on the generalized acceptance of the validity of screening derived from these studies, and a corollary assumption that any technological improvement in the quality of the image must inherently be an improvement of the overall results of screening.

The failure of new technologies to meet expectations is a sobering corrective to the high hopes of researchers, practitioners, and patient groups alike, and is perhaps destined to contribute more to the parallel history of controversy and distrust concerning the risk/benefits of mammography that has been a media and scientific mainstay.

Too often the history of medical technology has found disappointment at the end of the road for new discoveries. But although the disappointing results of digital screening might be considered a failure in the progress of mammography, it is likely just another pause on the road of this technology, the history of which has been rocky from the start.

The need for a new way of looking

The rationale behind the original and continuing development of mammography is a simple one, common to all cancer screening methods – the belief that the earlier the detection of a cancer, the more likely it is to be treated effectively with the therapeutic regimens at hand. While there is some controversy regarding the cost-benefit ratio of screening, especially when therapies for breast cancer are not perfect and vary widely in expense and availability globally, the driving belief has been that mammography provides an outcomes benefit in allowing early surgical and chemoradiation therapy with a curative intent.

There were two main driving forces behind the early development of mammography. The first was the highly lethal nature of breast cancer, especially when it was caught too late and had spread too far to benefit from the only available option at the time – surgery. The second was the severity of the surgical treatment, the only therapeutic option at the time, and the distressing number of women who faced the radical mastectomy procedure pioneered by physicians William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922) at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Willy Meyer (1858-1932) in New York.

In 1894, in an era when the development of anesthetics and antisepsis made ever more difficult surgical procedures possible without inevitably killing the patient, both men separately published their results of a highly extensive operation that consisted of removal of the breast, chest muscles, and axillary lymph nodes.

As long as there was no presurgical method of determining the extent of a breast cancer’s spread, much less an ability to visually distinguish malignant from benign growths, this “better safe than sorry” approach became the default approach of an increasing number of surgeons, and the drastic solution of radical mastectomy was increasingly applied universally.

But in 1895, with the discovery of x-rays, medical science recognized a nearly miraculous technology for visualizing the inside of the body, and radioactive materials were also routinely used in medical therapies, by both legitimate practitioners and hucksters.

However, in the very early days, the users of x-rays were unaware that large radiation doses could have serious biological effects and had no way of determining radiation field strength and accumulating dosage.

In fact, early calibration of x-ray tubes was based on the amount of skin reddening (erythema) produced when the operator placed a hand directly in the x-ray beam.

It was in this environment that, within only a few decades, the new x-rays, especially with the development of improvements in mammography imaging, were able in many cases to identify smaller, more curable breast cancers. This eventually allowed surgeons to develop and use less extensive operations than the highly disfiguring radical mastectomy that was simultaneously dreaded for its invasiveness and embraced for its life-saving potential.4

Pioneering era

The technological history of mammography was thus driven by the quest for better imaging and reproducibility in order to further the hopes of curative surgical approaches.

In 1913, the German surgeon Albert Salomon (1883-1976) was the first to detect breast cancer using x-rays, but its clinical use was not established, as the images published in his “Beiträge zur pathologie und klinik der mammakarzinome (Contributions to the pathology and clinic of breast cancers)” were photographs of postsurgical breast specimens that illustrated the anatomy and spread of breast cancer tumors but were not adapted to presurgical screening.

After Salomon’s work was published in 1913, there was no new mammography literature published until 1927, when German surgeon Otto Kleinschmidt (1880-1948) published a report describing the world’s first authentic mammography, which he attributed to his mentor, the plastic surgeon Erwin Payr (1871-1946).5

This was followed soon after in 1930 by the work of radiologist Stafford L. Warren (1896-1981), of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who published a paper on the use of standard roentgenograms for the in vivo preoperative assessment of breast malignancies. His technique involved the use of a stereoscopic system with a grid mechanism and intensifying screens to amplify the image. Breast compression was not involved in his mammogram technique. “Dr. Warren claimed to be correct 92% of the time when using this technique to predict malignancy.”5

His study of 119 women with a histopathologic diagnosis (61 benign and 58 malignant) demonstrated the feasibility of the technique for routine use and “created a surge of interest.”6

But the technology of the time proved difficult to use, and the results difficult to reproduce from laboratory to laboratory, and ultimately did not gain wide acceptance. Among Warren’s other claims to fame, he was a participant in the Manhattan Project and was a member of the teams sent to assess radiation damage in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the dropping of the atomic bombs.

And in fact, future developments in mammography and all other x-ray screening techniques included attempts to minimize radiation exposure; such attempts were driven, in part, by the tragic impact of atomic bomb radiation and the medical studies carried out on the survivors.

An image more deadly than the disease

Further improvements in mammography technique occurred through the 1930s and 1940s, including better visualization of the mammary ducts based upon the pioneering studies of Emil Ries, MD, in Chicago, who, along with Nymphus Frederick Hicken, MD (1900-1998), reported on the use of contrast mammography (also known as ductography or galactography). On a side note, Dr. Hicken was responsible for introducing the terms mammogram and mammography in 1937.

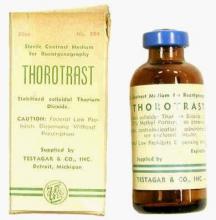

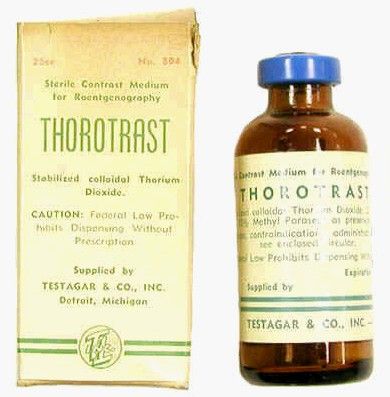

Problems with ductography, which involved the injection of a radiographically opaque contrast agent into the nipple, occurred when the early contrast agents, such as oil-based lipiodol, proved to be toxic and capable of causing abscesses.7This advance led to the development of other agents, and among the most popular at the time was one that would prove deadly to many.

Thorotrast, first used in 1928, was widely embraced because of its lack of immediately noticeable side effects and the high-quality contrast it provided. Thorotrast was a suspension of radioactive thorium dioxide particles, which gained popularity for use as a radiological imaging agent from the 1930s to 1950s throughout the world, being used in an estimated 2-10 million radiographic exams, primarily for neurosurgery.

In the 1920s and 1930s, world governments had begun to recognize the dangers of radiation exposure, especially among workers, but thorotrast was a unique case because, unbeknownst to most practitioners at the time, thorium dioxide was retained in the body for the lifetime of the patient, with 70% deposited in the liver, 20% in the spleen, and the remaining in the bony medulla and in the peripheral lymph nodes.

Nineteen years after the first use of thorotrast, the first case of a human malignant tumor attributed to its exposure was reported. “Besides the liver neoplasm cases, aplastic anemia, leukemia and an impressive incidence of chromosome aberrations were registered in exposed individuals.”8

Despite its widespread adoption elsewhere, especially in Japan, the use of thorotrast never became popular in the United States, in part because in 1932 and 1937, warnings were issued by the American Medical Association to restrict its use.9

There was a shift to the use of iodinated hydrophilic molecules as contrast agents for conventional x-ray, computed tomography, and fluoroscopy procedures.9 However, it was discovered that these agents, too, have their own risks and dangerous side effects. They can cause severe adverse effects, including allergies, cardiovascular diseases, and nephrotoxicity in some patients.

Slow adoption and limited results

Between 1930 and 1950, Dr. Warren, Jacob Gershon-Cohen, MD (1899-1971) of Philadelphia, and radiologist Raul Leborgne of Uruguay “spread the gospel of mammography as an adjunct to physical examination for the diagnosis of breast cancer.”4 The latter also developed the breast compression technique to produce better quality images and lower the radiation exposure needed, and described the differences that could be visualized between benign and malign microcalcifications.

But despite the introduction of improvements such as double-emulsion film and breast compression to produce higher-quality images, “mammographic films often remained dark and hazy. Moreover, the new techniques, while improving the images, were not easily reproduced by other investigators and clinicians,” and therefore were still not widely adopted.4

Little noticeable effect of mammography

Although the technology existed and had its popularizers, mammography had little impact on an epidemiological level.

There was no major change in the mean maximum breast cancer tumor diameter and node positivity rate detected over the 20 years from 1929 to 1948.10 However, starting in the late 1940s, the American Cancer Society began public education campaigns and early detection education, and thereafter, there was a 3% decline in mean maximum diameter of tumor size seen every 10 years until 1968.

“We have interpreted this as the effect of public education and professional education about early detection through television, print media, and professional publications that began in 1947 because no other event was known to occur that would affect cancer detection beginning in the late 1940s.”10

However, the early detection methods at the time were self-examination and clinical examination for lumps, with mammography remaining a relatively limited tool until its general acceptance broadened a few decades later.

Robert Egan, “Father of Mammography,” et al.

The broad acceptance of mammography as a screening tool and its impacts on a broad population level resulted in large part from the work of Robert L. Egan, MD (1921-2001) in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Dr. Egan’s work was inspired in 1956 by a presentation by a visiting fellow, Jean Pierre Batiani, who brought a mammogram clearly showing a breast cancer from his institution, the Curie Foundation in Paris. The image had been made using very low kilowattage, high tube currents, and fine-grain film.

Dr. Egan, then a resident in radiology, was given the task by the head of his department of reproducing the results.

In 1959, Dr. Egan, then at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, published a combined technique that used a high-milliamperage–low-voltage technique, a fine-grain intensifying screen, and single-emulsion films for mammography, thereby decreasing the radiation exposure significantly from previous x-ray techniques and improving the visualization and reproducibility of screening.

By 1960, Dr. Egan reported on 1,000 mammography cases at MD Anderson, demonstrating the ability of proper screening to detect unsuspected cancers and to limit mastectomies on benign masses. Of 245 breast cancers ultimately confirmed by biopsy, 238 were discovered by mammography, 19 of which were in women whose physical examinations had revealed no breast pathology. One of the cancers was only 8 mm in diameter when sectioned at biopsy.

Dr. Egan’s findings prompted an investigation by the Cancer Control Program (CCP) of the U.S. Public Health Service and led to a study jointly conducted by the National Cancer Institute and MD Anderson Hospital and the CCP, which involved 24 institutions and 1,500 patients.

“The results showed a 21% false-negative rate and a 79% true-positive rate for screening studies using Egan’s technique. This was a milestone for women’s imaging in the United States. Screening mammography was off to a tentative start.”5

“Egan was the man who developed a smooth-riding automobile compared to a Model T. He put mammography on the map and made it an intelligible, reproducible study. In short, he was the father of modern mammography,” according to his professor, mentor, and fellow mammography pioneer Gerald Dodd, MD (Emory School of Medicine website biography).

In 1964 Dr. Egan published his definitive book, “Mammography,” and in 1965 he hosted a 30-minute audiovisual presentation describing in detail his technique.11

The use of mammography was further powered by improved methods of preoperative needle localization, pioneered by Richard H. Gold, MD, in 1963 at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, which eased obtaining a tissue diagnosis for any suspicious lesions detected in the mammogram. Dr. Gold performed needle localization of nonpalpable, mammographically visible lesions before biopsy, which allowed surgical resection of a smaller volume of breast tissue than was possible before.

Throughout the era, there were also incremental improvements in mammography machines and an increase in the number of commercial manufacturers.

Xeroradiography, an imaging technique adapted from xerographic photocopying, was seen as a major improvement over direct film imaging, and the technology became popular throughout the 1970s based on the research of John N. Wolfe, MD (1923-1993), who worked closely with the Xerox Corporation to improve the breast imaging process.6 However, this technology had all the same problems associated with running an office copying machine, including paper jams and toner issues, and the worst aspect was the high dose of radiation required. For this reason, it would quickly be superseded by the use of screen-film mammography, which eventually completely replaced the use of both xeromammography and direct-exposure film mammography.

The march of mammography

A series of nine randomized clinical trials (RCTs) between the 1960s and 1990s formed the foundation of the clinical use of mammography. These studies enrolled more than 600,000 women in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Sweden. The nine main RCTs of breast cancer screening were the Health Insurance Plan of Greater New York (HIP) trial, the Edinburgh trial, the Canadian National Breast Screening Study, the Canadian National Breast Screening Study 2, the United Kingdom Age trial, the Stockholm trial, the Malmö Mammographic Screening Trial, the Gothenburg trial, and the Swedish Two-County Study.3

These trials incorporated improvements in the technology as it developed, as seen in the fact that the earliest, the HIP trial, used direct-exposure film mammography and the other trials used screen-film mammography.3

Meta-analyses of the major nine screening trials indicated that reduced breast cancer mortality with screening was dependent on age. In particular, the results for women aged 40-49 years and 50-59 years showed only borderline statistical significance, and they varied depending on how cases were accrued in individual trials. “Assuming that differences actually exist, the absolute breast cancer mortality reduction per 10,000 women screened for 10 years ranged from 3 for age 39-49 years; 5-8 for age 50-59 years; and 12-21 for age 60-69 years.”3 In addition the estimates for women aged 70-74 years were limited by low numbers of events in trials that had smaller numbers of women in this age group.

However, at the time, the studies had a profound influence on increasing the popularity and spread of mammography.

As mammographies became more common, standardization became an important issue and a Mammography Accreditation Program began in 1987. Originally a voluntary program, it became mandatory with the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992, which required all U.S. mammography facilities to become accredited and certified.

In 1986, the American College of Radiology proposed its Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) initiative to enable standardized reporting of mammography; the first report was released in 1993.

BI-RADS is now on its fifth edition and has addressed the use of mammography, breast ultrasonography, and breast magnetic resonance imaging, developing standardized auditing approaches for all three techniques of breast cancer imaging.6

The digital era and beyond

With the dawn of the 21st century, the era of digital breast cancer screening began.

The screen-film mammography (SFM) technique employed throughout the 1980s and 1990s had significant advantages over earlier x-ray films for producing more vivid images of dense breast tissues. The next technology, digital mammography, was introduced in the late 20th century, and the first system was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2000.

One of the key benefits touted for digital mammograms is the fact that the radiologist can manipulate the contrast of the images, which allows for masses to be identified that might otherwise not be visible on standard film.

However, the recent meta-analysis discussed in the introduction calls such benefits into question, and a new controversy is likely to ensue on the question of the effectiveness of digital mammography on overall clinical outcomes.

But the technology continues to evolve.

“There has been a continuous and substantial technical development from SFM to full-field digital mammography and very recently also the introduction of digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT). This technical evolution calls for new evidence regarding the performance of screening using new mammography technologies, and the evidence needed to translate new technologies into screening practice,” according to an updated assessment by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.12

DBT was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011. The technology involves the creation of a series of images, which are assembled into a 3-D–like image of breast slices. Traditional digital mammography creates a 2-D image of a flattened breast, and the radiologist must peer through the layers to find abnormalities. DBT uses a computer algorithm to reconstruct multiple low-dose digital images of the breast that can be displayed individually or in cinematic mode.13

Early trials showed a significant benefit of DBT in detecting new and smaller breast cancers, compared with standard digital mammography.

In women in their 40s, DBT found 1.7 more cancers than digital mammography for every 1,000 exams of women with normal breast tissue. In addition, 16.3% of women in this age group who were screened using digital mammography received callbacks, versus 11.7% of those screened using DBT. For younger women with dense breasts, the advantage of DBT was even greater, with 2.27 more cancers found for every 1,000 women screened. Whether such results will lead to clinically improved outcomes remains a question. “It can still miss cancers. Also, like traditional mammography, DBT might not reduce deaths from tumors that are very aggressive and fast-growing. And some women will still be called back unnecessarily for false-positive results.”14

But such technological advances further the hopes of researchers and patients alike.

Conclusion

Medical technology is driven both by advances in science and by the demands of patients and physicians for improved outcomes. The history of mammography, for example, is tied to the scientific advancements in x-ray technology, which allowed physicians for the first time to peer inside a living body without a scalpel at hand. But mammography was also an outgrowth of the profound need of the surgeon to identify cancerous masses in the breast at an early-enough stage to attempt a cure, while simultaneously minimizing the radical nature of the surgery required.

And while seeing is believing, the need to see and verify what was seen in order to make life-and-death decisions drove the demand for improvements in the technology of mammography throughout most of the 20th century and beyond.

The tortuous path from the early and continuing snafus with contrast agents to the apparent failure of the promise of digital technology serves as a continuing reminder of the hopes and perils that developing medical technologies present. It will be interesting to see if further refinements to mammography, such as DBT, will enhance the technology enough to have a major impact on countless women’s lives, or if new developments in magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound make traditional mammography a relic of the past.

Part 2 of this history will present the social dynamics intimately involved with the rise and promulgation of mammography and how social need and public fears and controversies affected its development and spread as much, if not more, than technological innovation.

This article could only touch upon the myriad of details and technologies involved in the history of mammography, and I urge interested readers to check out the relevant references for far more in-depth and fascinating stories from its complex and controversial past.

References

1. Felix EL, Rosen M, Earle D. “Curbing Our Enthusiasm for Surgical Innovation: Is It a Good Thing or Bad Thing?” The Great Debates, General Surgery News, 2018 Oct 17

2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa080.

3. Nelson H et al. Screening for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review to Update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Evidence Synthesis No. 124. (Rockville, Md.: U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016 Jan, pp. 29-49)4. Lerner, BH. “To See Today With the Eyes of Tomorrow: A History of Screening Mammography,” background paper for Patlak M et al., Mammography and Beyond: Developing Technologies for the Early Detection of Breast Cancer (Washington: National Academies Press, 2001).

5. Grady I, Hansen P. Chapter 28: Mammography in “Kuerer’s Breast Surgical Oncology”(New York: McGaw-Hill Medical, 2010)

6. Radiology. 2014 Nov;273(2 Suppl):S23-44.

7. Bassett LW, Kim CH. (2003) Chapter 1: Ductography in Dershaw DD (eds) “Imaging-Guided Interventional Breast Techniques” (New York: Springer, 2003, pp. 1-30).

8. Cuperschmid EM, Ribeiro de Campos TP. 2009 International Nuclear Atlantic Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Sept 27–Oct 2, 2009

9. Bioscience Microflora. 2000;19(2):107-16.

10. Cady B. New era in breast cancer. Impact of screening on disease presentation. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1997 Apr;6(2):195-202.

11. Egan R. “Mammography Technique.” Audiovisual presentation. (Washington: U.S. Public Health Service, 1965).

12. Zackrisson S, Houssami N. Chapter 13: Evolution of Mammography Screening: From Film Screen to Digital Breast Tomosynthesis in “Breast Cancer Screening: An Examination of Scientific Evidence” (Cambridge, Mass.: Academic Press, 2016, pp. 323-46).13. Melnikow J et al. Screening for breast cancer with digital breast tomosynthesis. Evidence Synthesis No. 125 (Rockville, Md.: U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016 Jan).

14. Newer breast screening technology may spot more cancers. Harvard Women’s Health Watch online, June 2019.

Mark Lesney is the editor of Hematology News and the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has worked as a writer/editor for the American Chemical Society, and has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

Technological imperatives

Technological imperatives

The history of mammography provides a powerful example of the connection between social factors and the rise of a medical technology. It is also an object lesson in the profound difficulties that the medical community faces when trying to evaluate and embrace new discoveries in such a complex area as cancer diagnosis and treatment, especially when tied to issues of sex-based bias and gender identity. Given its profound ties to women’s lives and women’s bodies, mammography holds a unique place in the history of cancer. Part 1 will examine the technological imperatives driving mammography forward, and part 2 will address the social factors that promoted and inhibited the developing technology.

All that glitters

Innovations in technology have contributed so greatly to the progress of medical science in saving and improving patients’ lives that the lure of new technology and the desire to see it succeed and to embrace it has become profound.

In a debate on the adoption of new technologies, Michael Rosen, MD, a surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, pointed out the inherent risks in the life cycle of medical technology: “The stages of surgical innovation have been well described as moving from the generation of a hypothesis with an early promising report to being accepted conclusively as a new standard without formal testing. As the life cycle continues and comparative effectiveness data begin to emerge slowly through appropriately designed trials, the procedure or device is often ultimately abandoned.”1

The history of mammography bears out this grim warning in example after example as an object lesson, revealing not only the difficulties involved in the development of new medical technologies, but also the profound problems involved in validating the effectiveness and appropriateness of a new technology from its inception to the present.

A modern failure?

In fact, one of the more modern developments in mammography technology – digital imaging – has recently been called into question with regard to its effectiveness in saving lives, even as the technology continues to spread throughout the medical community.

A recent meta-analysis has shown that there is little or no improvement in outcomes of breast cancer screening when using digital analysis and screening mammograms vs. traditional film recording.

The meta-analysis assessed 24 studies with a combined total of 16,583,743 screening examinations (10,968,843 film and 5,614,900 digital). The study found that the difference in cancer detection rate using digital rather than film screening showed an increase of only 0.51 detections per 1,000 screens.

The researchers concluded “that while digital mammography is beneficial for medical facilities due to easier storage and handling of images, these results suggest the transition from film to digital mammography has not resulted in health benefits for screened women.”2

In fact, the researchers added that “This analysis reinforces the need to carefully evaluate effects of future changes in technology, such as tomosynthesis, to ensure new technology leads to improved health outcomes and beyond technical gains.”2

None of the nine main randomized clinical trials that were used to determine the effectiveness of mammography screening from the 1960s to the 1990s used digital or 3-D digital mammography (digital breast tomosynthesis or DBT). The earliest trial used direct-exposure film mammography and the others relied upon screen-film mammography.3 And yet the assumptions of the validity of the new digital technologies were predicated on the generalized acceptance of the validity of screening derived from these studies, and a corollary assumption that any technological improvement in the quality of the image must inherently be an improvement of the overall results of screening.

The failure of new technologies to meet expectations is a sobering corrective to the high hopes of researchers, practitioners, and patient groups alike, and is perhaps destined to contribute more to the parallel history of controversy and distrust concerning the risk/benefits of mammography that has been a media and scientific mainstay.

Too often the history of medical technology has found disappointment at the end of the road for new discoveries. But although the disappointing results of digital screening might be considered a failure in the progress of mammography, it is likely just another pause on the road of this technology, the history of which has been rocky from the start.

The need for a new way of looking

The rationale behind the original and continuing development of mammography is a simple one, common to all cancer screening methods – the belief that the earlier the detection of a cancer, the more likely it is to be treated effectively with the therapeutic regimens at hand. While there is some controversy regarding the cost-benefit ratio of screening, especially when therapies for breast cancer are not perfect and vary widely in expense and availability globally, the driving belief has been that mammography provides an outcomes benefit in allowing early surgical and chemoradiation therapy with a curative intent.

There were two main driving forces behind the early development of mammography. The first was the highly lethal nature of breast cancer, especially when it was caught too late and had spread too far to benefit from the only available option at the time – surgery. The second was the severity of the surgical treatment, the only therapeutic option at the time, and the distressing number of women who faced the radical mastectomy procedure pioneered by physicians William Stewart Halsted (1852-1922) at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and Willy Meyer (1858-1932) in New York.

In 1894, in an era when the development of anesthetics and antisepsis made ever more difficult surgical procedures possible without inevitably killing the patient, both men separately published their results of a highly extensive operation that consisted of removal of the breast, chest muscles, and axillary lymph nodes.

As long as there was no presurgical method of determining the extent of a breast cancer’s spread, much less an ability to visually distinguish malignant from benign growths, this “better safe than sorry” approach became the default approach of an increasing number of surgeons, and the drastic solution of radical mastectomy was increasingly applied universally.

But in 1895, with the discovery of x-rays, medical science recognized a nearly miraculous technology for visualizing the inside of the body, and radioactive materials were also routinely used in medical therapies, by both legitimate practitioners and hucksters.

However, in the very early days, the users of x-rays were unaware that large radiation doses could have serious biological effects and had no way of determining radiation field strength and accumulating dosage.

In fact, early calibration of x-ray tubes was based on the amount of skin reddening (erythema) produced when the operator placed a hand directly in the x-ray beam.

It was in this environment that, within only a few decades, the new x-rays, especially with the development of improvements in mammography imaging, were able in many cases to identify smaller, more curable breast cancers. This eventually allowed surgeons to develop and use less extensive operations than the highly disfiguring radical mastectomy that was simultaneously dreaded for its invasiveness and embraced for its life-saving potential.4

Pioneering era

The technological history of mammography was thus driven by the quest for better imaging and reproducibility in order to further the hopes of curative surgical approaches.

In 1913, the German surgeon Albert Salomon (1883-1976) was the first to detect breast cancer using x-rays, but its clinical use was not established, as the images published in his “Beiträge zur pathologie und klinik der mammakarzinome (Contributions to the pathology and clinic of breast cancers)” were photographs of postsurgical breast specimens that illustrated the anatomy and spread of breast cancer tumors but were not adapted to presurgical screening.

After Salomon’s work was published in 1913, there was no new mammography literature published until 1927, when German surgeon Otto Kleinschmidt (1880-1948) published a report describing the world’s first authentic mammography, which he attributed to his mentor, the plastic surgeon Erwin Payr (1871-1946).5

This was followed soon after in 1930 by the work of radiologist Stafford L. Warren (1896-1981), of the University of Rochester (N.Y.), who published a paper on the use of standard roentgenograms for the in vivo preoperative assessment of breast malignancies. His technique involved the use of a stereoscopic system with a grid mechanism and intensifying screens to amplify the image. Breast compression was not involved in his mammogram technique. “Dr. Warren claimed to be correct 92% of the time when using this technique to predict malignancy.”5

His study of 119 women with a histopathologic diagnosis (61 benign and 58 malignant) demonstrated the feasibility of the technique for routine use and “created a surge of interest.”6

But the technology of the time proved difficult to use, and the results difficult to reproduce from laboratory to laboratory, and ultimately did not gain wide acceptance. Among Warren’s other claims to fame, he was a participant in the Manhattan Project and was a member of the teams sent to assess radiation damage in Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the dropping of the atomic bombs.

And in fact, future developments in mammography and all other x-ray screening techniques included attempts to minimize radiation exposure; such attempts were driven, in part, by the tragic impact of atomic bomb radiation and the medical studies carried out on the survivors.

An image more deadly than the disease

Further improvements in mammography technique occurred through the 1930s and 1940s, including better visualization of the mammary ducts based upon the pioneering studies of Emil Ries, MD, in Chicago, who, along with Nymphus Frederick Hicken, MD (1900-1998), reported on the use of contrast mammography (also known as ductography or galactography). On a side note, Dr. Hicken was responsible for introducing the terms mammogram and mammography in 1937.

Problems with ductography, which involved the injection of a radiographically opaque contrast agent into the nipple, occurred when the early contrast agents, such as oil-based lipiodol, proved to be toxic and capable of causing abscesses.7This advance led to the development of other agents, and among the most popular at the time was one that would prove deadly to many.

Thorotrast, first used in 1928, was widely embraced because of its lack of immediately noticeable side effects and the high-quality contrast it provided. Thorotrast was a suspension of radioactive thorium dioxide particles, which gained popularity for use as a radiological imaging agent from the 1930s to 1950s throughout the world, being used in an estimated 2-10 million radiographic exams, primarily for neurosurgery.

In the 1920s and 1930s, world governments had begun to recognize the dangers of radiation exposure, especially among workers, but thorotrast was a unique case because, unbeknownst to most practitioners at the time, thorium dioxide was retained in the body for the lifetime of the patient, with 70% deposited in the liver, 20% in the spleen, and the remaining in the bony medulla and in the peripheral lymph nodes.

Nineteen years after the first use of thorotrast, the first case of a human malignant tumor attributed to its exposure was reported. “Besides the liver neoplasm cases, aplastic anemia, leukemia and an impressive incidence of chromosome aberrations were registered in exposed individuals.”8

Despite its widespread adoption elsewhere, especially in Japan, the use of thorotrast never became popular in the United States, in part because in 1932 and 1937, warnings were issued by the American Medical Association to restrict its use.9

There was a shift to the use of iodinated hydrophilic molecules as contrast agents for conventional x-ray, computed tomography, and fluoroscopy procedures.9 However, it was discovered that these agents, too, have their own risks and dangerous side effects. They can cause severe adverse effects, including allergies, cardiovascular diseases, and nephrotoxicity in some patients.

Slow adoption and limited results

Between 1930 and 1950, Dr. Warren, Jacob Gershon-Cohen, MD (1899-1971) of Philadelphia, and radiologist Raul Leborgne of Uruguay “spread the gospel of mammography as an adjunct to physical examination for the diagnosis of breast cancer.”4 The latter also developed the breast compression technique to produce better quality images and lower the radiation exposure needed, and described the differences that could be visualized between benign and malign microcalcifications.

But despite the introduction of improvements such as double-emulsion film and breast compression to produce higher-quality images, “mammographic films often remained dark and hazy. Moreover, the new techniques, while improving the images, were not easily reproduced by other investigators and clinicians,” and therefore were still not widely adopted.4

Little noticeable effect of mammography

Although the technology existed and had its popularizers, mammography had little impact on an epidemiological level.

There was no major change in the mean maximum breast cancer tumor diameter and node positivity rate detected over the 20 years from 1929 to 1948.10 However, starting in the late 1940s, the American Cancer Society began public education campaigns and early detection education, and thereafter, there was a 3% decline in mean maximum diameter of tumor size seen every 10 years until 1968.

“We have interpreted this as the effect of public education and professional education about early detection through television, print media, and professional publications that began in 1947 because no other event was known to occur that would affect cancer detection beginning in the late 1940s.”10

However, the early detection methods at the time were self-examination and clinical examination for lumps, with mammography remaining a relatively limited tool until its general acceptance broadened a few decades later.

Robert Egan, “Father of Mammography,” et al.

The broad acceptance of mammography as a screening tool and its impacts on a broad population level resulted in large part from the work of Robert L. Egan, MD (1921-2001) in the late 1950s and 1960s.

Dr. Egan’s work was inspired in 1956 by a presentation by a visiting fellow, Jean Pierre Batiani, who brought a mammogram clearly showing a breast cancer from his institution, the Curie Foundation in Paris. The image had been made using very low kilowattage, high tube currents, and fine-grain film.

Dr. Egan, then a resident in radiology, was given the task by the head of his department of reproducing the results.

In 1959, Dr. Egan, then at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, published a combined technique that used a high-milliamperage–low-voltage technique, a fine-grain intensifying screen, and single-emulsion films for mammography, thereby decreasing the radiation exposure significantly from previous x-ray techniques and improving the visualization and reproducibility of screening.

By 1960, Dr. Egan reported on 1,000 mammography cases at MD Anderson, demonstrating the ability of proper screening to detect unsuspected cancers and to limit mastectomies on benign masses. Of 245 breast cancers ultimately confirmed by biopsy, 238 were discovered by mammography, 19 of which were in women whose physical examinations had revealed no breast pathology. One of the cancers was only 8 mm in diameter when sectioned at biopsy.

Dr. Egan’s findings prompted an investigation by the Cancer Control Program (CCP) of the U.S. Public Health Service and led to a study jointly conducted by the National Cancer Institute and MD Anderson Hospital and the CCP, which involved 24 institutions and 1,500 patients.

“The results showed a 21% false-negative rate and a 79% true-positive rate for screening studies using Egan’s technique. This was a milestone for women’s imaging in the United States. Screening mammography was off to a tentative start.”5

“Egan was the man who developed a smooth-riding automobile compared to a Model T. He put mammography on the map and made it an intelligible, reproducible study. In short, he was the father of modern mammography,” according to his professor, mentor, and fellow mammography pioneer Gerald Dodd, MD (Emory School of Medicine website biography).

In 1964 Dr. Egan published his definitive book, “Mammography,” and in 1965 he hosted a 30-minute audiovisual presentation describing in detail his technique.11

The use of mammography was further powered by improved methods of preoperative needle localization, pioneered by Richard H. Gold, MD, in 1963 at Jefferson Medical College, Philadelphia, which eased obtaining a tissue diagnosis for any suspicious lesions detected in the mammogram. Dr. Gold performed needle localization of nonpalpable, mammographically visible lesions before biopsy, which allowed surgical resection of a smaller volume of breast tissue than was possible before.

Throughout the era, there were also incremental improvements in mammography machines and an increase in the number of commercial manufacturers.

Xeroradiography, an imaging technique adapted from xerographic photocopying, was seen as a major improvement over direct film imaging, and the technology became popular throughout the 1970s based on the research of John N. Wolfe, MD (1923-1993), who worked closely with the Xerox Corporation to improve the breast imaging process.6 However, this technology had all the same problems associated with running an office copying machine, including paper jams and toner issues, and the worst aspect was the high dose of radiation required. For this reason, it would quickly be superseded by the use of screen-film mammography, which eventually completely replaced the use of both xeromammography and direct-exposure film mammography.

The march of mammography

A series of nine randomized clinical trials (RCTs) between the 1960s and 1990s formed the foundation of the clinical use of mammography. These studies enrolled more than 600,000 women in the United States, Canada, the United Kingdom, and Sweden. The nine main RCTs of breast cancer screening were the Health Insurance Plan of Greater New York (HIP) trial, the Edinburgh trial, the Canadian National Breast Screening Study, the Canadian National Breast Screening Study 2, the United Kingdom Age trial, the Stockholm trial, the Malmö Mammographic Screening Trial, the Gothenburg trial, and the Swedish Two-County Study.3

These trials incorporated improvements in the technology as it developed, as seen in the fact that the earliest, the HIP trial, used direct-exposure film mammography and the other trials used screen-film mammography.3

Meta-analyses of the major nine screening trials indicated that reduced breast cancer mortality with screening was dependent on age. In particular, the results for women aged 40-49 years and 50-59 years showed only borderline statistical significance, and they varied depending on how cases were accrued in individual trials. “Assuming that differences actually exist, the absolute breast cancer mortality reduction per 10,000 women screened for 10 years ranged from 3 for age 39-49 years; 5-8 for age 50-59 years; and 12-21 for age 60-69 years.”3 In addition the estimates for women aged 70-74 years were limited by low numbers of events in trials that had smaller numbers of women in this age group.

However, at the time, the studies had a profound influence on increasing the popularity and spread of mammography.

As mammographies became more common, standardization became an important issue and a Mammography Accreditation Program began in 1987. Originally a voluntary program, it became mandatory with the Mammography Quality Standards Act of 1992, which required all U.S. mammography facilities to become accredited and certified.

In 1986, the American College of Radiology proposed its Breast Imaging Reporting and Data System (BI-RADS) initiative to enable standardized reporting of mammography; the first report was released in 1993.

BI-RADS is now on its fifth edition and has addressed the use of mammography, breast ultrasonography, and breast magnetic resonance imaging, developing standardized auditing approaches for all three techniques of breast cancer imaging.6

The digital era and beyond

With the dawn of the 21st century, the era of digital breast cancer screening began.

The screen-film mammography (SFM) technique employed throughout the 1980s and 1990s had significant advantages over earlier x-ray films for producing more vivid images of dense breast tissues. The next technology, digital mammography, was introduced in the late 20th century, and the first system was approved by the U.S. FDA in 2000.

One of the key benefits touted for digital mammograms is the fact that the radiologist can manipulate the contrast of the images, which allows for masses to be identified that might otherwise not be visible on standard film.

However, the recent meta-analysis discussed in the introduction calls such benefits into question, and a new controversy is likely to ensue on the question of the effectiveness of digital mammography on overall clinical outcomes.

But the technology continues to evolve.

“There has been a continuous and substantial technical development from SFM to full-field digital mammography and very recently also the introduction of digital breast tomosynthesis (DBT). This technical evolution calls for new evidence regarding the performance of screening using new mammography technologies, and the evidence needed to translate new technologies into screening practice,” according to an updated assessment by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.12

DBT was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2011. The technology involves the creation of a series of images, which are assembled into a 3-D–like image of breast slices. Traditional digital mammography creates a 2-D image of a flattened breast, and the radiologist must peer through the layers to find abnormalities. DBT uses a computer algorithm to reconstruct multiple low-dose digital images of the breast that can be displayed individually or in cinematic mode.13

Early trials showed a significant benefit of DBT in detecting new and smaller breast cancers, compared with standard digital mammography.

In women in their 40s, DBT found 1.7 more cancers than digital mammography for every 1,000 exams of women with normal breast tissue. In addition, 16.3% of women in this age group who were screened using digital mammography received callbacks, versus 11.7% of those screened using DBT. For younger women with dense breasts, the advantage of DBT was even greater, with 2.27 more cancers found for every 1,000 women screened. Whether such results will lead to clinically improved outcomes remains a question. “It can still miss cancers. Also, like traditional mammography, DBT might not reduce deaths from tumors that are very aggressive and fast-growing. And some women will still be called back unnecessarily for false-positive results.”14

But such technological advances further the hopes of researchers and patients alike.

Conclusion

Medical technology is driven both by advances in science and by the demands of patients and physicians for improved outcomes. The history of mammography, for example, is tied to the scientific advancements in x-ray technology, which allowed physicians for the first time to peer inside a living body without a scalpel at hand. But mammography was also an outgrowth of the profound need of the surgeon to identify cancerous masses in the breast at an early-enough stage to attempt a cure, while simultaneously minimizing the radical nature of the surgery required.

And while seeing is believing, the need to see and verify what was seen in order to make life-and-death decisions drove the demand for improvements in the technology of mammography throughout most of the 20th century and beyond.

The tortuous path from the early and continuing snafus with contrast agents to the apparent failure of the promise of digital technology serves as a continuing reminder of the hopes and perils that developing medical technologies present. It will be interesting to see if further refinements to mammography, such as DBT, will enhance the technology enough to have a major impact on countless women’s lives, or if new developments in magnetic resonance imaging and ultrasound make traditional mammography a relic of the past.

Part 2 of this history will present the social dynamics intimately involved with the rise and promulgation of mammography and how social need and public fears and controversies affected its development and spread as much, if not more, than technological innovation.

This article could only touch upon the myriad of details and technologies involved in the history of mammography, and I urge interested readers to check out the relevant references for far more in-depth and fascinating stories from its complex and controversial past.

References

1. Felix EL, Rosen M, Earle D. “Curbing Our Enthusiasm for Surgical Innovation: Is It a Good Thing or Bad Thing?” The Great Debates, General Surgery News, 2018 Oct 17

2. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Jun 23. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa080.

3. Nelson H et al. Screening for Breast Cancer: A Systematic Review to Update the 2009 U.S. Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation. Evidence Synthesis No. 124. (Rockville, Md.: U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016 Jan, pp. 29-49)4. Lerner, BH. “To See Today With the Eyes of Tomorrow: A History of Screening Mammography,” background paper for Patlak M et al., Mammography and Beyond: Developing Technologies for the Early Detection of Breast Cancer (Washington: National Academies Press, 2001).

5. Grady I, Hansen P. Chapter 28: Mammography in “Kuerer’s Breast Surgical Oncology”(New York: McGaw-Hill Medical, 2010)

6. Radiology. 2014 Nov;273(2 Suppl):S23-44.

7. Bassett LW, Kim CH. (2003) Chapter 1: Ductography in Dershaw DD (eds) “Imaging-Guided Interventional Breast Techniques” (New York: Springer, 2003, pp. 1-30).

8. Cuperschmid EM, Ribeiro de Campos TP. 2009 International Nuclear Atlantic Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Sept 27–Oct 2, 2009

9. Bioscience Microflora. 2000;19(2):107-16.

10. Cady B. New era in breast cancer. Impact of screening on disease presentation. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 1997 Apr;6(2):195-202.

11. Egan R. “Mammography Technique.” Audiovisual presentation. (Washington: U.S. Public Health Service, 1965).

12. Zackrisson S, Houssami N. Chapter 13: Evolution of Mammography Screening: From Film Screen to Digital Breast Tomosynthesis in “Breast Cancer Screening: An Examination of Scientific Evidence” (Cambridge, Mass.: Academic Press, 2016, pp. 323-46).13. Melnikow J et al. Screening for breast cancer with digital breast tomosynthesis. Evidence Synthesis No. 125 (Rockville, Md.: U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, 2016 Jan).

14. Newer breast screening technology may spot more cancers. Harvard Women’s Health Watch online, June 2019.

Mark Lesney is the editor of Hematology News and the managing editor of MDedge.com/IDPractioner. He has a PhD in plant virology and a PhD in the history of science, with a focus on the history of biotechnology and medicine. He has worked as a writer/editor for the American Chemical Society, and has served as an adjunct assistant professor in the department of biochemistry and molecular & cellular biology at Georgetown University, Washington.

The history of mammography provides a powerful example of the connection between social factors and the rise of a medical technology. It is also an object lesson in the profound difficulties that the medical community faces when trying to evaluate and embrace new discoveries in such a complex area as cancer diagnosis and treatment, especially when tied to issues of sex-based bias and gender identity. Given its profound ties to women’s lives and women’s bodies, mammography holds a unique place in the history of cancer. Part 1 will examine the technological imperatives driving mammography forward, and part 2 will address the social factors that promoted and inhibited the developing technology.

All that glitters

Innovations in technology have contributed so greatly to the progress of medical science in saving and improving patients’ lives that the lure of new technology and the desire to see it succeed and to embrace it has become profound.

In a debate on the adoption of new technologies, Michael Rosen, MD, a surgeon at the Cleveland Clinic, Ohio, pointed out the inherent risks in the life cycle of medical technology: “The stages of surgical innovation have been well described as moving from the generation of a hypothesis with an early promising report to being accepted conclusively as a new standard without formal testing. As the life cycle continues and comparative effectiveness data begin to emerge slowly through appropriately designed trials, the procedure or device is often ultimately abandoned.”1

The history of mammography bears out this grim warning in example after example as an object lesson, revealing not only the difficulties involved in the development of new medical technologies, but also the profound problems involved in validating the effectiveness and appropriateness of a new technology from its inception to the present.

A modern failure?

In fact, one of the more modern developments in mammography technology – digital imaging – has recently been called into question with regard to its effectiveness in saving lives, even as the technology continues to spread throughout the medical community.

A recent meta-analysis has shown that there is little or no improvement in outcomes of breast cancer screening when using digital analysis and screening mammograms vs. traditional film recording.

The meta-analysis assessed 24 studies with a combined total of 16,583,743 screening examinations (10,968,843 film and 5,614,900 digital). The study found that the difference in cancer detection rate using digital rather than film screening showed an increase of only 0.51 detections per 1,000 screens.