User login

Helping families understand internalized racism

Ms. Jones brings her 15-year-old daughter, Angela, to the resident clinic. Angela is becoming increasingly anxious, withdrawn, and difficult to manage. As part of the initial interview, the resident, Dr. Sota, asks about the sociocultural background of the family. Ms. Jones is African American and recently began a relationship with a white man. Her daughter, Angela, is biracial; her biological father is white and has moved out of state with little ongoing contact with Angela and her mother.

At interview, Angela expresses a lot of anger at her mother, her biological father, and her new “stepfather.” Ms. Jones says: “I do not want Angela growing up as an ‘angry black woman.’ ” When asked for an explanation, she stated that she doesn’t want her daughter to be stereotyped, to be perceived as an angry black person. “She needs to fit in with our new life. She has lots of opportunities if only she would take them.”

Dr. Sota recognizes that Angela’s struggle, and perhaps also the struggle of Ms. Jones, has a component of internalized racism. How should Dr. Sota proceed? Dr. Sota puts herself in Angela’s shoes: How does Angela see herself? Angela has light brown skin, and

The term internalized racism (IR) first appeared in the 1980s. IR was compared to the oppression of black people in the 1800s: “The slavery that captures the mind and incarcerates the motivation, perception, aspiration, and identity in a web of anti-self images, generating a personal and collective self destruction, is more cruel than the shackles on the wrists and ankles.”1 According to Susanne Lipsky,2 IR “in African Americans manifests as internalizing stereotypes, mistrusting the self and other Blacks, and narrows one’s view of authentic Black culture.”

IR refers to the internalization and acceptance of the dominant white culture’s actions and beliefs, while rejecting one’s own cultural background. There is a long history of negative cultural representations of African Americans in popular American culture, and IR has a detrimental impact on the emotional well-being of African Americans.3

IR is associated with poorer metabolic health4 and psychological distress, depression and anxiety,5-8 and decreased self-esteem.9 However, protective processes can reduce one’s response to risk and can be developed through the psychotherapeutic relationship.

Interventions at an individual, family, or community levels

Angela: Tell me about yourself: What type of person are you? How do you identify? How do you feel about yourself/your appearance/your language?

Tell me about your friends/family? What interests do you have?

“Tell me more” questions can reveal conflicted feelings, etc., even if Angela does not answer. A good therapist can talk about IR; even if Angela does not bring it up, it is important for the therapist to find language suitable for the age of the patient.

Dr. Sota has some luck with Angela, who nods her head but says little. Dr. Sota then turns to Ms. Jones and asks whether she can answer these questions, too, and rephrases the questions for an adult. Interviewing parents in the presence of their children gives Dr. Sota and Angela an idea of what is permitted to talk about in the family.

A therapist can also note other permissions in the family: How do Angela and her mother use language? Do they claim or reject words and phrases such as “angry black woman” and choose, instead, to use language to “fit in” with the dominant white culture?

Dr. Sota notices that Ms. Jones presents herself as keen to fit in with her new future husband’s life. She wants Angela to do likewise. Dr. Sota notices that Angela vacillates between wanting to claim her black identity and having to navigate what that means in this family (not a good thing) – and wanting to assimilate into white culture. Her peers fall into two separate groups: a set of black friends and a set of white friends. Her mother prefers that she see her white friends, mistrusting her black friends.

Dr. Sota’s supervisor suggests that she introduce IR more forcefully because this seems to be a major course of conflict for Angela and encourage a frank discussion between mother and daughter. Dr. Sota starts the next session in the following way: “I noticed last week that the way you each identify yourselves is quite different. Ms. Jones, you want Angela to ‘fit in’ and perhaps just embrace white culture, whereas Angela, perhaps you vacillate between a white identity and a black identity?”

The following questions can help Dr. Sota elicit IR:

- What information about yourself would you like others to know – about your heritage, country of origin, family, class background, and so on?

- What makes you proud about being a member of this group, and what do you love about other members of this group?

- What has been hard about being a member of this group, and what don’t you like about others in this group?

- What were your early life experiences with people in this group? How were you treated? How did you feel about others in your group when you were young?

At a community level, family workshops support positive cultural identities that strengthen family functioning and reducing behavioral health risks. In a study of 575 urban American Indian (AI) families from diverse tribal backgrounds, the AI families who participated in such a workshop had significant increases in their ethnic identity, improved sense of spirituality, and a more positive cultural identification. The workshops provided culturally adaptive parenting interventions.10

IR is a serious determinant of both physical and mental health. Assessment of IR can be done using rating scales, such as the Nadanolitization Scale11 or the Internalized Racial Oppression Scale.12 IR also can also be assessed using a more formalized interview guide, such as the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI).13 This 16-question interview guide helps behavioral health providers better understand the way service users and their social networks (e.g., families, friends) understand what is happening to them and why, as well as the barriers they experience, such as racism, discrimination, stigma, and financial stressors.

Individuals’ cultures and experiences have a profound impact on their understanding of their symptoms and their engagement in care. The American Psychiatric Association considers it to be part of mental health providers’ duty of care to engage all individuals in culturally relevant conversations about their past experiences and care expectations. More relevant, I submit that you cannot treat someone without having made this inquiry. A cultural assessment improves understanding but also shifts power relationships between providers and patients. The DSM-5 CFI and training guides are widely available and provide additional information for those who want to improve their cultural literacy.

Conclusion

Internalized racism is the component of racism that is the most difficult to discern. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals are uniquely poised to address IR, and any subsequent internal conflict and identity difficulties. Each program, office, and clinic can easily find the resources to do this through the APA. If you would like help providing education, contact me at alisonheru@gmail.com.

References

1. Akbar N. J Black Studies. 1984. doi: 10.11771002193478401400401.

2. Lipsky S. Internalized Racism. Seattle: Rational Island Publishers, 1987.

3. Williams DR and Mohammed SA. Am Behav Sci. 2013 May 8. doi: 10.1177/00027642134873340.

4. DeLilly CR and Flaskerud JH. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012 Nov;33(11):804-11.

5. Molina KM and James D. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016 Jul;19(4):439-61.

6. Szymanski D and Obiri O. Couns Psychologist. 2011;39(3):438-62.

7. Carter RT et al. J Multicul Couns Dev. 2017 Oct 5;45(4):232-59.

8. Mouzon DM and McLean JS. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb;22(1):36-48.

9. Szymanski DM and Gupta A. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):110-18.

10. Kulis SS et al. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1037/cpd000315.

11. Taylor J and Grundy C. “Measuring black internalization of white stereotypes about African Americans: The Nadanolization Scale.” In: Jones RL, ed. Handbook of Tests and Measurements of Black Populations. Hampton, Va.: Cobb & Henry, 1996.

12. Bailey T-K M et al. J Couns Psychol. 2011 Oct;58(4):481-93.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Cultural Formulation Interview. DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, Va. 2013.

Various aspects about the case described above have been changed to protect the clinician’s and patients’ identities. Thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to this article: Suzanne Huberty, MD, and Shiona Heru, JD.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ms. Jones brings her 15-year-old daughter, Angela, to the resident clinic. Angela is becoming increasingly anxious, withdrawn, and difficult to manage. As part of the initial interview, the resident, Dr. Sota, asks about the sociocultural background of the family. Ms. Jones is African American and recently began a relationship with a white man. Her daughter, Angela, is biracial; her biological father is white and has moved out of state with little ongoing contact with Angela and her mother.

At interview, Angela expresses a lot of anger at her mother, her biological father, and her new “stepfather.” Ms. Jones says: “I do not want Angela growing up as an ‘angry black woman.’ ” When asked for an explanation, she stated that she doesn’t want her daughter to be stereotyped, to be perceived as an angry black person. “She needs to fit in with our new life. She has lots of opportunities if only she would take them.”

Dr. Sota recognizes that Angela’s struggle, and perhaps also the struggle of Ms. Jones, has a component of internalized racism. How should Dr. Sota proceed? Dr. Sota puts herself in Angela’s shoes: How does Angela see herself? Angela has light brown skin, and

The term internalized racism (IR) first appeared in the 1980s. IR was compared to the oppression of black people in the 1800s: “The slavery that captures the mind and incarcerates the motivation, perception, aspiration, and identity in a web of anti-self images, generating a personal and collective self destruction, is more cruel than the shackles on the wrists and ankles.”1 According to Susanne Lipsky,2 IR “in African Americans manifests as internalizing stereotypes, mistrusting the self and other Blacks, and narrows one’s view of authentic Black culture.”

IR refers to the internalization and acceptance of the dominant white culture’s actions and beliefs, while rejecting one’s own cultural background. There is a long history of negative cultural representations of African Americans in popular American culture, and IR has a detrimental impact on the emotional well-being of African Americans.3

IR is associated with poorer metabolic health4 and psychological distress, depression and anxiety,5-8 and decreased self-esteem.9 However, protective processes can reduce one’s response to risk and can be developed through the psychotherapeutic relationship.

Interventions at an individual, family, or community levels

Angela: Tell me about yourself: What type of person are you? How do you identify? How do you feel about yourself/your appearance/your language?

Tell me about your friends/family? What interests do you have?

“Tell me more” questions can reveal conflicted feelings, etc., even if Angela does not answer. A good therapist can talk about IR; even if Angela does not bring it up, it is important for the therapist to find language suitable for the age of the patient.

Dr. Sota has some luck with Angela, who nods her head but says little. Dr. Sota then turns to Ms. Jones and asks whether she can answer these questions, too, and rephrases the questions for an adult. Interviewing parents in the presence of their children gives Dr. Sota and Angela an idea of what is permitted to talk about in the family.

A therapist can also note other permissions in the family: How do Angela and her mother use language? Do they claim or reject words and phrases such as “angry black woman” and choose, instead, to use language to “fit in” with the dominant white culture?

Dr. Sota notices that Ms. Jones presents herself as keen to fit in with her new future husband’s life. She wants Angela to do likewise. Dr. Sota notices that Angela vacillates between wanting to claim her black identity and having to navigate what that means in this family (not a good thing) – and wanting to assimilate into white culture. Her peers fall into two separate groups: a set of black friends and a set of white friends. Her mother prefers that she see her white friends, mistrusting her black friends.

Dr. Sota’s supervisor suggests that she introduce IR more forcefully because this seems to be a major course of conflict for Angela and encourage a frank discussion between mother and daughter. Dr. Sota starts the next session in the following way: “I noticed last week that the way you each identify yourselves is quite different. Ms. Jones, you want Angela to ‘fit in’ and perhaps just embrace white culture, whereas Angela, perhaps you vacillate between a white identity and a black identity?”

The following questions can help Dr. Sota elicit IR:

- What information about yourself would you like others to know – about your heritage, country of origin, family, class background, and so on?

- What makes you proud about being a member of this group, and what do you love about other members of this group?

- What has been hard about being a member of this group, and what don’t you like about others in this group?

- What were your early life experiences with people in this group? How were you treated? How did you feel about others in your group when you were young?

At a community level, family workshops support positive cultural identities that strengthen family functioning and reducing behavioral health risks. In a study of 575 urban American Indian (AI) families from diverse tribal backgrounds, the AI families who participated in such a workshop had significant increases in their ethnic identity, improved sense of spirituality, and a more positive cultural identification. The workshops provided culturally adaptive parenting interventions.10

IR is a serious determinant of both physical and mental health. Assessment of IR can be done using rating scales, such as the Nadanolitization Scale11 or the Internalized Racial Oppression Scale.12 IR also can also be assessed using a more formalized interview guide, such as the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI).13 This 16-question interview guide helps behavioral health providers better understand the way service users and their social networks (e.g., families, friends) understand what is happening to them and why, as well as the barriers they experience, such as racism, discrimination, stigma, and financial stressors.

Individuals’ cultures and experiences have a profound impact on their understanding of their symptoms and their engagement in care. The American Psychiatric Association considers it to be part of mental health providers’ duty of care to engage all individuals in culturally relevant conversations about their past experiences and care expectations. More relevant, I submit that you cannot treat someone without having made this inquiry. A cultural assessment improves understanding but also shifts power relationships between providers and patients. The DSM-5 CFI and training guides are widely available and provide additional information for those who want to improve their cultural literacy.

Conclusion

Internalized racism is the component of racism that is the most difficult to discern. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals are uniquely poised to address IR, and any subsequent internal conflict and identity difficulties. Each program, office, and clinic can easily find the resources to do this through the APA. If you would like help providing education, contact me at alisonheru@gmail.com.

References

1. Akbar N. J Black Studies. 1984. doi: 10.11771002193478401400401.

2. Lipsky S. Internalized Racism. Seattle: Rational Island Publishers, 1987.

3. Williams DR and Mohammed SA. Am Behav Sci. 2013 May 8. doi: 10.1177/00027642134873340.

4. DeLilly CR and Flaskerud JH. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012 Nov;33(11):804-11.

5. Molina KM and James D. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016 Jul;19(4):439-61.

6. Szymanski D and Obiri O. Couns Psychologist. 2011;39(3):438-62.

7. Carter RT et al. J Multicul Couns Dev. 2017 Oct 5;45(4):232-59.

8. Mouzon DM and McLean JS. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb;22(1):36-48.

9. Szymanski DM and Gupta A. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):110-18.

10. Kulis SS et al. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1037/cpd000315.

11. Taylor J and Grundy C. “Measuring black internalization of white stereotypes about African Americans: The Nadanolization Scale.” In: Jones RL, ed. Handbook of Tests and Measurements of Black Populations. Hampton, Va.: Cobb & Henry, 1996.

12. Bailey T-K M et al. J Couns Psychol. 2011 Oct;58(4):481-93.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Cultural Formulation Interview. DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, Va. 2013.

Various aspects about the case described above have been changed to protect the clinician’s and patients’ identities. Thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to this article: Suzanne Huberty, MD, and Shiona Heru, JD.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Ms. Jones brings her 15-year-old daughter, Angela, to the resident clinic. Angela is becoming increasingly anxious, withdrawn, and difficult to manage. As part of the initial interview, the resident, Dr. Sota, asks about the sociocultural background of the family. Ms. Jones is African American and recently began a relationship with a white man. Her daughter, Angela, is biracial; her biological father is white and has moved out of state with little ongoing contact with Angela and her mother.

At interview, Angela expresses a lot of anger at her mother, her biological father, and her new “stepfather.” Ms. Jones says: “I do not want Angela growing up as an ‘angry black woman.’ ” When asked for an explanation, she stated that she doesn’t want her daughter to be stereotyped, to be perceived as an angry black person. “She needs to fit in with our new life. She has lots of opportunities if only she would take them.”

Dr. Sota recognizes that Angela’s struggle, and perhaps also the struggle of Ms. Jones, has a component of internalized racism. How should Dr. Sota proceed? Dr. Sota puts herself in Angela’s shoes: How does Angela see herself? Angela has light brown skin, and

The term internalized racism (IR) first appeared in the 1980s. IR was compared to the oppression of black people in the 1800s: “The slavery that captures the mind and incarcerates the motivation, perception, aspiration, and identity in a web of anti-self images, generating a personal and collective self destruction, is more cruel than the shackles on the wrists and ankles.”1 According to Susanne Lipsky,2 IR “in African Americans manifests as internalizing stereotypes, mistrusting the self and other Blacks, and narrows one’s view of authentic Black culture.”

IR refers to the internalization and acceptance of the dominant white culture’s actions and beliefs, while rejecting one’s own cultural background. There is a long history of negative cultural representations of African Americans in popular American culture, and IR has a detrimental impact on the emotional well-being of African Americans.3

IR is associated with poorer metabolic health4 and psychological distress, depression and anxiety,5-8 and decreased self-esteem.9 However, protective processes can reduce one’s response to risk and can be developed through the psychotherapeutic relationship.

Interventions at an individual, family, or community levels

Angela: Tell me about yourself: What type of person are you? How do you identify? How do you feel about yourself/your appearance/your language?

Tell me about your friends/family? What interests do you have?

“Tell me more” questions can reveal conflicted feelings, etc., even if Angela does not answer. A good therapist can talk about IR; even if Angela does not bring it up, it is important for the therapist to find language suitable for the age of the patient.

Dr. Sota has some luck with Angela, who nods her head but says little. Dr. Sota then turns to Ms. Jones and asks whether she can answer these questions, too, and rephrases the questions for an adult. Interviewing parents in the presence of their children gives Dr. Sota and Angela an idea of what is permitted to talk about in the family.

A therapist can also note other permissions in the family: How do Angela and her mother use language? Do they claim or reject words and phrases such as “angry black woman” and choose, instead, to use language to “fit in” with the dominant white culture?

Dr. Sota notices that Ms. Jones presents herself as keen to fit in with her new future husband’s life. She wants Angela to do likewise. Dr. Sota notices that Angela vacillates between wanting to claim her black identity and having to navigate what that means in this family (not a good thing) – and wanting to assimilate into white culture. Her peers fall into two separate groups: a set of black friends and a set of white friends. Her mother prefers that she see her white friends, mistrusting her black friends.

Dr. Sota’s supervisor suggests that she introduce IR more forcefully because this seems to be a major course of conflict for Angela and encourage a frank discussion between mother and daughter. Dr. Sota starts the next session in the following way: “I noticed last week that the way you each identify yourselves is quite different. Ms. Jones, you want Angela to ‘fit in’ and perhaps just embrace white culture, whereas Angela, perhaps you vacillate between a white identity and a black identity?”

The following questions can help Dr. Sota elicit IR:

- What information about yourself would you like others to know – about your heritage, country of origin, family, class background, and so on?

- What makes you proud about being a member of this group, and what do you love about other members of this group?

- What has been hard about being a member of this group, and what don’t you like about others in this group?

- What were your early life experiences with people in this group? How were you treated? How did you feel about others in your group when you were young?

At a community level, family workshops support positive cultural identities that strengthen family functioning and reducing behavioral health risks. In a study of 575 urban American Indian (AI) families from diverse tribal backgrounds, the AI families who participated in such a workshop had significant increases in their ethnic identity, improved sense of spirituality, and a more positive cultural identification. The workshops provided culturally adaptive parenting interventions.10

IR is a serious determinant of both physical and mental health. Assessment of IR can be done using rating scales, such as the Nadanolitization Scale11 or the Internalized Racial Oppression Scale.12 IR also can also be assessed using a more formalized interview guide, such as the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI).13 This 16-question interview guide helps behavioral health providers better understand the way service users and their social networks (e.g., families, friends) understand what is happening to them and why, as well as the barriers they experience, such as racism, discrimination, stigma, and financial stressors.

Individuals’ cultures and experiences have a profound impact on their understanding of their symptoms and their engagement in care. The American Psychiatric Association considers it to be part of mental health providers’ duty of care to engage all individuals in culturally relevant conversations about their past experiences and care expectations. More relevant, I submit that you cannot treat someone without having made this inquiry. A cultural assessment improves understanding but also shifts power relationships between providers and patients. The DSM-5 CFI and training guides are widely available and provide additional information for those who want to improve their cultural literacy.

Conclusion

Internalized racism is the component of racism that is the most difficult to discern. Psychiatrists and mental health professionals are uniquely poised to address IR, and any subsequent internal conflict and identity difficulties. Each program, office, and clinic can easily find the resources to do this through the APA. If you would like help providing education, contact me at alisonheru@gmail.com.

References

1. Akbar N. J Black Studies. 1984. doi: 10.11771002193478401400401.

2. Lipsky S. Internalized Racism. Seattle: Rational Island Publishers, 1987.

3. Williams DR and Mohammed SA. Am Behav Sci. 2013 May 8. doi: 10.1177/00027642134873340.

4. DeLilly CR and Flaskerud JH. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2012 Nov;33(11):804-11.

5. Molina KM and James D. Group Process Intergroup Relat. 2016 Jul;19(4):439-61.

6. Szymanski D and Obiri O. Couns Psychologist. 2011;39(3):438-62.

7. Carter RT et al. J Multicul Couns Dev. 2017 Oct 5;45(4):232-59.

8. Mouzon DM and McLean JS. Ethn Health. 2017 Feb;22(1):36-48.

9. Szymanski DM and Gupta A. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):110-18.

10. Kulis SS et al. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychol. 2019. doi: 10.1037/cpd000315.

11. Taylor J and Grundy C. “Measuring black internalization of white stereotypes about African Americans: The Nadanolization Scale.” In: Jones RL, ed. Handbook of Tests and Measurements of Black Populations. Hampton, Va.: Cobb & Henry, 1996.

12. Bailey T-K M et al. J Couns Psychol. 2011 Oct;58(4):481-93.

13. American Psychiatric Association. Cultural Formulation Interview. DSM-5. American Psychiatric Association Publishing: Arlington, Va. 2013.

Various aspects about the case described above have been changed to protect the clinician’s and patients’ identities. Thanks to the following individuals for their contributions to this article: Suzanne Huberty, MD, and Shiona Heru, JD.

Dr. Heru is professor of psychiatry at the University of Colorado at Denver, Aurora. She is editor of “Working With Families in Medical Settings: A Multidisciplinary Guide for Psychiatrists and Other Health Professionals” (Routledge, 2013). She has no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Calculations of an academic hospitalist

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

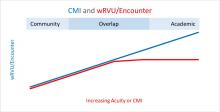

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

The term “academic hospitalist” has come to mean more than a mere affiliation to an academic medical center (AMC). Academic hospitalists perform various clinical roles like staffing house staff teams, covering nonteaching services, critical care services, procedure teams, night services, medical consultation, and comanagement services.

Over the last decade, academic hospitalists have successfully managed many nonclinical roles in areas like research, medical unit leadership, faculty development, faculty affairs, quality, safety, informatics, utilization review, clinical documentation, throughput, group management, hospital administration, and educational leadership. The role of an academic hospital is as clear as a chocolate martini these days. Here we present some recent trends in academic hospital medicine.

Compensation

From SHM’s State of Hospital Medicine report (SoHM)2014 to 2018 data, the median compensation for U.S. academic hospitalists has risen by an average of 5.15% every year, although increases vary by rank.1 From 2016 to 2018, clinical instructors saw the most significant growth, 11.23% per year, suggesting a need to remain competitive for junior hospitalists. Compensation also varies by geographic area, with the Southern region reporting the highest compensation. Over the last decade, academic hospitalists received, on average, a 28%-35% lower salary, compared with community hospitalists.

Patient population and census

Lower patient encounters and compensation of the academic hospitalists poses the chicken or the egg dilemma. In the 2018 SoHM report, academic hospitalists had an average of 17% fewer encounters. Of note, AMC patients tend to have higher complexity, as measured by the Case Mix Index (CMI – the average diagnosis-related group weight of a hospital).2 A higher CMI is a surrogate marker for the diagnostic diversity, clinical complexity, and resource needs of the patient population in the hospital.

Productivity and financial metrics

The financial bottom line is a critical aspect, and as a report in the Journal of Hospital Medicine described, all health care executives look at business metrics while making decisions.3 Below are some significant academic and community comparisons from SoHM 2018.

- Collections, encounters, and wRVUs (work relative value units) were highly correlated. All of them were lower for academic hospitalists, corroborating the fact that they see a smaller number of patients. Clinical full-time equivalents (cFTE) is a vernacular of how much of the faculty time is devoted to clinical activities. The academic data from SoHM achieves the same target, as it is standardized to 100% billable clinical activity, so the fact that many academic hospitalists do not work a full-time clinical schedule is not a factor in their lower production.

- Charges had a smaller gap likely because of sicker patients in AMCs. The higher acuity difference can also explain 12% higher wRVU/encounter for academic hospitalists.

- The wRVU/encounter ratio can indicate a few patterns: high acuity of patients in AMCs, higher levels of evaluation and management documentation, or both. As the encounters and charges have the same percentage differences, we would place our bets on the former.

- Compensation per encounter and compensation per wRVU showed that academic hospitalists do get a slight advantage.

CMI and wRVUs

Although the SoHM does not capture information on patient acuity or CMI, we speculate that the relationship between CMI and wRVUs may be more or less linear at lower levels of acuity. However, once level III E/M billing is achieved (assuming there is no critical care provided), wRVUs/encounter plateau, even as acuity continues to increase. This plateau effect may be seen more often in high-acuity AMC settings than in community hospitals.

So, in our opinion, compensation models based solely on wRVU production would not do justice for hospitalists in AMC settings since these models would fail to capture the extra work involved with very-high-acuity patients. SoHM 2018 shows the financial support per wRVU for AMC is $45.81, and for the community is $41.28, an 11% difference. We think the higher financial support per wRVU for academic practices may be related to the lost wRVU potential of caring for very-high-acuity patients.

Conclusion

In an academic setting, hospitalists are reforming the field of hospital medicine and defining the ways we could deliver care. They are the pillars of collaboration, education, research, innovation, quality, and safety. It would be increasingly crucial for academic hospitalist leaders to use comparative metrics from SoHM to advocate for their group. The bottom line can be explained by the title of the qualitative study in JHM referenced above: “Collaboration, not calculation.”3

Dr. Chadha is division chief for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare, Lexington. He actively leads efforts of recruiting, scheduling, practice analysis, and operation of the group. He is a first-time member of the practice analysis committee. Ms. Dede is division administrator for the division of hospital medicine at the University of Kentucky Healthcare. She prepares and manages budgets, liaisons with the downstream revenue teams, and contributes to the building of academic compensation models. She is serving in the practice administrators committee for the second year and is currently vice chair of the Executive Council for the Practice Administrators special interest group.

References

1. State of Hospital Medicine Report. https://www.hospitalmedicine.org/practice-management/shms-state-of-hospital-medicine/

2. Deloitte Center for Health Solutions. Academic Medical Centers: Joining forces with community providers for broad benefits and positive outcomes. 2015. https://www2.deloitte.com/us/en/pages/life-sciences-and-health-care/articles/academic-medical-centers-consolidation.html

3. White AA et al. Collaboration, not calculation: A qualitative study of how hospital executives value hospital medicine groups. J Hosp Med. 2019;14(10):662‐7.

As a black psychiatrist, she is ‘exhausted’ and ‘furious’

I didn’t have any doctors in my family. The only doctor I knew was my pediatrician. At 6 years old – and this gives you a glimpse into my personality – I told my parents I did not think he was a good doctor. I said, “When I grow up to be a doctor, I’m going to be a better doctor than him.” Fast forward to 7th grade, when I saw an orthopedic surgeon for my scoliosis. He was phenomenal. He listened. He explained to me all of the science and medicine and his rationale for decisions. I thought, “That is the kind of doctor I want to be.”

I went to medical school at Penn and didn’t think psychiatry was a medical specialty. I thought it was just Freud and laying on couches. I thought, “Where’s the science, where’s the physiology, where’s the genetics?” I was headed toward surgery.

Then, I rotated with an incredible psychiatrist. I saw behavior was biological, chemical, electrical, and physiological. I realize, looking back, that I had an interest because there is mental illness in my family. And there is so much stigma against psychiatric illnesses and addiction. It’s shocking how badly our patients get treated in the general medicine construct. So, I thought, “This field has science, the human body, activism, and marginalized patients? This is for me!”

I went to Howard University, which was the most freeing time of my life. There was no code-switching, no working hard to be a “presentable” Black person. When I started interviewing for medical schools, I was told by someone I interviewed with at one school that I should straighten my hair if I wanted to get accepted. I marked that school off my list. I decided right then that I would rather not go to medical school than straighten my hair to get into medical school. I went to Penn; they accepted me without my hair straight.

Penn Med was majorly White. There were six of us who were Black in a class of about 150 people. There was this feeling like “we let you in” even though every single one of us who was there was clearly at the top of the game to have been able to get there. I loved Penn Med. My class was amazing. I became the first Black president of medical student government there and I won a lot of awards.

When I was finishing up, my dean at the time, who was a White woman, said, “I’m so proud of you. You came in a piece of coal and look how we shined you up. “What do you say? I have a smart mouth, so I said, “I was already shiny when I got here.” She said, “See, that’s part of your problem, you don’t know how to take a compliment.” That was 2002, and I still remember every word of that conversation.

I was on the psychiatry unit rounding as a medical student and introduced myself to a patient. He said, “What’s your name?” And I thought, here it comes. I said, “Nzinga Ajabu,” my name at the time. He said “Nzinga? You probably have a spear in your closet.” When I tell these stories to White people, they’re always shocked. When I tell these stories to Black people, they say, “Yeah, that sounds about right.”

You can talk to Black medical students, Black interns, Black residents. When patients say something racist to you, nobody speaks up for you, nobody. It should be the attending that professionally approaches the patient and says something, anything. But they just laugh uncomfortably, they let it pass, they pretend they didn’t hear it. Meanwhile, you are fuming, and injured, and have to maintain your professionalism. It happens all the time. When people say, “Oh, you don’t look like a doctor,” I know what that means, but someone else may not even notice it’s an insult. When they do notice an insult, they don’t have the language or the courage to address it. And it’s not always a patient leveling racial insults. It very often is the attending, the fellow, the resident, or another medical student.

These things happen to me less now because I’m in a position of power. I’d say most insults that come my way now are overwhelmingly unintentional. I call people out on it 95% of the time. The other 5% of the time, I’m either exhausted, or I’m in some power structure where I decide it’s too risky. And those are the days – when I decide it’s too risky for me to speak up – when I come home exhausted. Because there will always be a power dynamic, as long as I’m alive, where you can’t speak up because you’re a Black woman, and that just wears me out.

Ultimately, I opted out of academic medicine because I thought it was too constraining, that I wouldn’t be able to raise my voice and do the activism I needed to do. – I’m able to advocate for people who are marginalized by medicine and, in treating addiction, advocate for people who are marginalized by psychiatry, which is marginalized by medicine.

A bias people have is that when you talk about Black people, they think you are talking about poor people. When we talk about police brutality, or being pulled over by the police, or dying in childbirth, our colleagues don’t think that’s happening to us. They think that’s happening to “those” Black people. Regardless of my socioeconomic status, I still have a higher chance of dying in childbirth or dying from COVID.

COVID had already turned my work up to 100 – we had staff losing loved ones and coming down with fevers themselves. And I had just launched my podcast. Then they killed Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Amy Cooper called the cops on Christian Cooper, and they killed George Floyd. This is how it happens. Bam. Bam. Bam.

The series of killings turned up my work at Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform, but it also turned up my work as a mother. My boys are 13 and 14. I personally can’t watch some of the videos because I see my own sons. I was already tired. Now I’m exhausted, I’m furious and I’m desperate to protect my kids. They have this on their backs already. Both of them have already had to deal with overt racism – they’ve had this burden since they were 5 years old, if not younger. I have to teach them to fight this war. Should that be how it is?

Nzinga Harrison, MD, 43, is a psychiatrist and the cofounder and chief medical officer of Eleanor Health, a network of physician clinics that treats people affected by addiction in North Carolina and New Jersey. She is also a cofounder of Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform. and host of the new podcast In Recovery. Harrison was raised in Indianapolis, went to college at Howard University and received her MD from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 2002. Her mother was an elementary school teacher. Her father, an electrical engineer, was commander of the local Black Panther Militia. Both supported her love of math and science and brought her with them to picket lines and marches.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I didn’t have any doctors in my family. The only doctor I knew was my pediatrician. At 6 years old – and this gives you a glimpse into my personality – I told my parents I did not think he was a good doctor. I said, “When I grow up to be a doctor, I’m going to be a better doctor than him.” Fast forward to 7th grade, when I saw an orthopedic surgeon for my scoliosis. He was phenomenal. He listened. He explained to me all of the science and medicine and his rationale for decisions. I thought, “That is the kind of doctor I want to be.”

I went to medical school at Penn and didn’t think psychiatry was a medical specialty. I thought it was just Freud and laying on couches. I thought, “Where’s the science, where’s the physiology, where’s the genetics?” I was headed toward surgery.

Then, I rotated with an incredible psychiatrist. I saw behavior was biological, chemical, electrical, and physiological. I realize, looking back, that I had an interest because there is mental illness in my family. And there is so much stigma against psychiatric illnesses and addiction. It’s shocking how badly our patients get treated in the general medicine construct. So, I thought, “This field has science, the human body, activism, and marginalized patients? This is for me!”

I went to Howard University, which was the most freeing time of my life. There was no code-switching, no working hard to be a “presentable” Black person. When I started interviewing for medical schools, I was told by someone I interviewed with at one school that I should straighten my hair if I wanted to get accepted. I marked that school off my list. I decided right then that I would rather not go to medical school than straighten my hair to get into medical school. I went to Penn; they accepted me without my hair straight.

Penn Med was majorly White. There were six of us who were Black in a class of about 150 people. There was this feeling like “we let you in” even though every single one of us who was there was clearly at the top of the game to have been able to get there. I loved Penn Med. My class was amazing. I became the first Black president of medical student government there and I won a lot of awards.

When I was finishing up, my dean at the time, who was a White woman, said, “I’m so proud of you. You came in a piece of coal and look how we shined you up. “What do you say? I have a smart mouth, so I said, “I was already shiny when I got here.” She said, “See, that’s part of your problem, you don’t know how to take a compliment.” That was 2002, and I still remember every word of that conversation.

I was on the psychiatry unit rounding as a medical student and introduced myself to a patient. He said, “What’s your name?” And I thought, here it comes. I said, “Nzinga Ajabu,” my name at the time. He said “Nzinga? You probably have a spear in your closet.” When I tell these stories to White people, they’re always shocked. When I tell these stories to Black people, they say, “Yeah, that sounds about right.”

You can talk to Black medical students, Black interns, Black residents. When patients say something racist to you, nobody speaks up for you, nobody. It should be the attending that professionally approaches the patient and says something, anything. But they just laugh uncomfortably, they let it pass, they pretend they didn’t hear it. Meanwhile, you are fuming, and injured, and have to maintain your professionalism. It happens all the time. When people say, “Oh, you don’t look like a doctor,” I know what that means, but someone else may not even notice it’s an insult. When they do notice an insult, they don’t have the language or the courage to address it. And it’s not always a patient leveling racial insults. It very often is the attending, the fellow, the resident, or another medical student.

These things happen to me less now because I’m in a position of power. I’d say most insults that come my way now are overwhelmingly unintentional. I call people out on it 95% of the time. The other 5% of the time, I’m either exhausted, or I’m in some power structure where I decide it’s too risky. And those are the days – when I decide it’s too risky for me to speak up – when I come home exhausted. Because there will always be a power dynamic, as long as I’m alive, where you can’t speak up because you’re a Black woman, and that just wears me out.

Ultimately, I opted out of academic medicine because I thought it was too constraining, that I wouldn’t be able to raise my voice and do the activism I needed to do. – I’m able to advocate for people who are marginalized by medicine and, in treating addiction, advocate for people who are marginalized by psychiatry, which is marginalized by medicine.

A bias people have is that when you talk about Black people, they think you are talking about poor people. When we talk about police brutality, or being pulled over by the police, or dying in childbirth, our colleagues don’t think that’s happening to us. They think that’s happening to “those” Black people. Regardless of my socioeconomic status, I still have a higher chance of dying in childbirth or dying from COVID.

COVID had already turned my work up to 100 – we had staff losing loved ones and coming down with fevers themselves. And I had just launched my podcast. Then they killed Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Amy Cooper called the cops on Christian Cooper, and they killed George Floyd. This is how it happens. Bam. Bam. Bam.

The series of killings turned up my work at Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform, but it also turned up my work as a mother. My boys are 13 and 14. I personally can’t watch some of the videos because I see my own sons. I was already tired. Now I’m exhausted, I’m furious and I’m desperate to protect my kids. They have this on their backs already. Both of them have already had to deal with overt racism – they’ve had this burden since they were 5 years old, if not younger. I have to teach them to fight this war. Should that be how it is?

Nzinga Harrison, MD, 43, is a psychiatrist and the cofounder and chief medical officer of Eleanor Health, a network of physician clinics that treats people affected by addiction in North Carolina and New Jersey. She is also a cofounder of Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform. and host of the new podcast In Recovery. Harrison was raised in Indianapolis, went to college at Howard University and received her MD from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 2002. Her mother was an elementary school teacher. Her father, an electrical engineer, was commander of the local Black Panther Militia. Both supported her love of math and science and brought her with them to picket lines and marches.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

I didn’t have any doctors in my family. The only doctor I knew was my pediatrician. At 6 years old – and this gives you a glimpse into my personality – I told my parents I did not think he was a good doctor. I said, “When I grow up to be a doctor, I’m going to be a better doctor than him.” Fast forward to 7th grade, when I saw an orthopedic surgeon for my scoliosis. He was phenomenal. He listened. He explained to me all of the science and medicine and his rationale for decisions. I thought, “That is the kind of doctor I want to be.”

I went to medical school at Penn and didn’t think psychiatry was a medical specialty. I thought it was just Freud and laying on couches. I thought, “Where’s the science, where’s the physiology, where’s the genetics?” I was headed toward surgery.

Then, I rotated with an incredible psychiatrist. I saw behavior was biological, chemical, electrical, and physiological. I realize, looking back, that I had an interest because there is mental illness in my family. And there is so much stigma against psychiatric illnesses and addiction. It’s shocking how badly our patients get treated in the general medicine construct. So, I thought, “This field has science, the human body, activism, and marginalized patients? This is for me!”

I went to Howard University, which was the most freeing time of my life. There was no code-switching, no working hard to be a “presentable” Black person. When I started interviewing for medical schools, I was told by someone I interviewed with at one school that I should straighten my hair if I wanted to get accepted. I marked that school off my list. I decided right then that I would rather not go to medical school than straighten my hair to get into medical school. I went to Penn; they accepted me without my hair straight.

Penn Med was majorly White. There were six of us who were Black in a class of about 150 people. There was this feeling like “we let you in” even though every single one of us who was there was clearly at the top of the game to have been able to get there. I loved Penn Med. My class was amazing. I became the first Black president of medical student government there and I won a lot of awards.

When I was finishing up, my dean at the time, who was a White woman, said, “I’m so proud of you. You came in a piece of coal and look how we shined you up. “What do you say? I have a smart mouth, so I said, “I was already shiny when I got here.” She said, “See, that’s part of your problem, you don’t know how to take a compliment.” That was 2002, and I still remember every word of that conversation.

I was on the psychiatry unit rounding as a medical student and introduced myself to a patient. He said, “What’s your name?” And I thought, here it comes. I said, “Nzinga Ajabu,” my name at the time. He said “Nzinga? You probably have a spear in your closet.” When I tell these stories to White people, they’re always shocked. When I tell these stories to Black people, they say, “Yeah, that sounds about right.”

You can talk to Black medical students, Black interns, Black residents. When patients say something racist to you, nobody speaks up for you, nobody. It should be the attending that professionally approaches the patient and says something, anything. But they just laugh uncomfortably, they let it pass, they pretend they didn’t hear it. Meanwhile, you are fuming, and injured, and have to maintain your professionalism. It happens all the time. When people say, “Oh, you don’t look like a doctor,” I know what that means, but someone else may not even notice it’s an insult. When they do notice an insult, they don’t have the language or the courage to address it. And it’s not always a patient leveling racial insults. It very often is the attending, the fellow, the resident, or another medical student.

These things happen to me less now because I’m in a position of power. I’d say most insults that come my way now are overwhelmingly unintentional. I call people out on it 95% of the time. The other 5% of the time, I’m either exhausted, or I’m in some power structure where I decide it’s too risky. And those are the days – when I decide it’s too risky for me to speak up – when I come home exhausted. Because there will always be a power dynamic, as long as I’m alive, where you can’t speak up because you’re a Black woman, and that just wears me out.

Ultimately, I opted out of academic medicine because I thought it was too constraining, that I wouldn’t be able to raise my voice and do the activism I needed to do. – I’m able to advocate for people who are marginalized by medicine and, in treating addiction, advocate for people who are marginalized by psychiatry, which is marginalized by medicine.

A bias people have is that when you talk about Black people, they think you are talking about poor people. When we talk about police brutality, or being pulled over by the police, or dying in childbirth, our colleagues don’t think that’s happening to us. They think that’s happening to “those” Black people. Regardless of my socioeconomic status, I still have a higher chance of dying in childbirth or dying from COVID.

COVID had already turned my work up to 100 – we had staff losing loved ones and coming down with fevers themselves. And I had just launched my podcast. Then they killed Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, Amy Cooper called the cops on Christian Cooper, and they killed George Floyd. This is how it happens. Bam. Bam. Bam.

The series of killings turned up my work at Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform, but it also turned up my work as a mother. My boys are 13 and 14. I personally can’t watch some of the videos because I see my own sons. I was already tired. Now I’m exhausted, I’m furious and I’m desperate to protect my kids. They have this on their backs already. Both of them have already had to deal with overt racism – they’ve had this burden since they were 5 years old, if not younger. I have to teach them to fight this war. Should that be how it is?

Nzinga Harrison, MD, 43, is a psychiatrist and the cofounder and chief medical officer of Eleanor Health, a network of physician clinics that treats people affected by addiction in North Carolina and New Jersey. She is also a cofounder of Physicians for Criminal Justice Reform. and host of the new podcast In Recovery. Harrison was raised in Indianapolis, went to college at Howard University and received her MD from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in 2002. Her mother was an elementary school teacher. Her father, an electrical engineer, was commander of the local Black Panther Militia. Both supported her love of math and science and brought her with them to picket lines and marches.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Medication-assisted treatment in corrections: A life-saving intervention

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.

14. Schuman-Olivier Z. et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2010 Jul;39(1):41-50.

15. Crotty K et al. J Addict Med. 2020;14(2)99-112.

Dr. Barnes is chief resident at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services in California. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Lenane is resident* at San Mateo County Behavioral Health and Recovery Services. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships. The opinions shared in this article represent the viewpoints of the authors and are not necessarily representative of the viewpoints or policies of their academic program or employer.

*This article was updated 7/9/2020.

Opioid overdose deaths in the United States have more than tripled in recent years, from 6.1 deaths per 100,000 individuals in 1999 to 20.7 per 100,000 individuals in 2018.1 Although the availability of medication-assisted treatment (MAT) has expanded over the past decade, this lifesaving treatment remains largely inaccessible to some of the most vulnerable members of our communities: opioid users facing reentry after incarceration.

Just as abstinence in the community brings a loss of tolerance to opioids, individuals who are incarcerated lose tolerance as well. Clinicians who treat patients with opioid use disorders (OUD) are accustomed to warning patients about the risk of returning to prior levels of use too quickly. Harm reduction strategies include using slowly, using with friends, and having naloxone on hand to prevent unintended overdose.

The risks of opioid use are magnified for those facing reentry; incarceration contributes to a loss of employment, social supports, and connection to care. Those changes can create an exceptionally stressful reentry period – one that places individuals at an acutely high risk of relapse and overdose. Within the first 2 years of release, an individual with a history of incarceration has a risk of death 3.5 times higher than that of someone in the general population. Within the first 2 weeks, those recently incarcerated are 129 times more likely to overdose on opioids and 12.7 times more likely to die than members of the general population.2

Treatment with MAT dramatically reduces deaths during this crucial period. In England, large national studies have shown a similar 75% decrease in all-cause mortality within the first 4 weeks of release among individuals with OUD.4 In California, the counties with the highest overdose death rates are consistently those with fewer opioid treatment programs, which suggests that access to treatment is necessary to prolong the lives of those suffering from OUD.5 In-custody overdose deaths are quite rare, and access to MAT during incarceration has decreased in-custody deaths by 74%.6

Decreased opioid overdose deaths is not the only outcome of MAT. Pharmacotherapy for OUD also has been shown to increase treatment retention,7 reduce reincarceration,8 prevent communicable infections,9 and decrease use of other illicit substances.10 The provision of MAT also has been shown to be cost effective.11

Despite those benefits, as of 2017, only 30 out of 5,100 jails and prisons in the United States provided treatment with methadone or buprenorphine.12 When individuals on maintenance therapy are incarcerated, most correctional facilities force them to taper and discontinue those medications. This practice can cause distressing withdrawal symptoms and actively increase the risk of death for these individuals.

Concerns related to the provision of MAT, and specifically buprenorphine, in the correctional health setting often are related to diversion. Although safe administration of opioid full and partial agonists is a priority, recent literature has suggested that buprenorphine is not a medication frequently used for euphoric properties. In fact, the literature suggests that individuals using illicit buprenorphine primarily do so to treat withdrawal symptoms and that illicit use diminishes with access to formal treatment.13,14

Another concern is that pharmacotherapy for OUD should not be used without adjunctive psychotherapies and social supports. While dual pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy is ideal, the American Society for Addiction Medicine 2020 National Practice Guidelines for the treatment of OUD state: “a patient’s decision to decline psychosocial treatment or the absence of available psychosocial treatment should not preclude or delay pharmacotherapy, with appropriate medication management.”15 Just as some patients wish to engage in mutual help or psychotherapeutic modalities only, some patients wish to engage only in psychopharmacologic interventions. Declaring one modality of treatment better, or worse, or more worthwhile is not borne out by the literature and often places clinicians’ preferences over the preferences of patients.

Individuals who suffer from substance use disorders are at high risk of incarceration, relapse, and overdose death. These patients also suffer from stigmatization from peers and health care workers alike, making the process of engaging in care incredibly burdensome. Because of the disease of addiction, many of our patients cannot envision a healthy future: a future with the potential for intimate relationships, meaningful community engagement, and a rich inner life. The provision of MAT is lifesaving and improves the chances of a successful reentry – an intuitive first step in a long, but worthwhile, journey.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al; National Center for Health Statistics. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999–2018. NCHS Data Brief, 2020 Jan, No. 356.

2. Binswanger IA et al. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:157-65.

3. Green TC et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(4):405-7.

4. Marsden J et al. Addiction. 2017;112(8):1408-18.

5. Joshi V and Urada D. State Targeted Response to the Opioid Crisis: California Strategic Plan. 2017 Aug 30.

6. Larney S et al. BMJ Open. 2014. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004666.

7. Rich JD et al. Lancet. 2015;386(9991):350-9.

8. Deck D et al. J Addict Dis. 2009. 28(2):89-102.

9. MacArthur GJ et al. BMJ. 2012. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e5945.

10. Tsui J et al. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2019. 109:80-5.

11. Gisev N et al. Addiction. 2015 Dec;110(12):1975-84.

12. National Mental Health and Substance Use Policy Laboratory. “Use of Medication-Assisted Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder in Criminal Justice Settings.” HHS Publication No. PEP19-MATUSECJS. Rockville, Md.: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2019.

13. Bazazi AR et al. J Addict Med. 2011;5(3):175-80.