User login

New evaluation and management of CPT codes for telemedicine in 2025

. The AMA says the new codes are designed to bring the coding system up to date with the changing landscape of health care and reflect the realities of modern medical practice.

The 17 new CPT codes will encompass a variety of telemedicine services. While the official language of the codes has not been released yet, codes for telemedicine visits using a real-time audio-visual platform could be organized similarly to existing office/outpatient E/M visits (99202-99205, 99212-99215). As part of these revisions, the current telephone E/M codes (99441-99443) will be deleted and replaced with new codes for audio-only E/M.

Implementation of so many codes will require health care providers and systems to adapt their documentation and coding practices. Typically, the exact language and code numbers for new and revised codes are not released to the public until fall of the preceding year, leaving only a few months for practices to educate their physicians and coding staff and prepare their internal systems for implementation starting Jan. 1, 2025. However, given the significant education and systems changes that will be necessary to prepare for so many new codes, we will advocate that the AMA release this information in early 2024.

Additionally, the reimbursement for telemedicine services may not ultimately be the same as for in-person E/M office visits. The AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) provides recommendations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for consideration in developing Relative Value Units (RVUs) for new procedures, including the telemedicine codes. The RUC’s recommendations for the telemedicine codes are not yet publicly available. However, it is important to note that regardless of the RUC recommendations, CMS makes all final decisions about Medicare payment. CMS could decide to set the payments for the telemedicine codes at parity with in-person office E/M visits or less than, more than, or some combination at the individual code level.

If payments for telemedicine visits are set at parity with or higher than office E/M visits, practices can focus primarily on physician and staff education and system implementation of the new codes. However, if telemedicine visit payments are less than in-person E/M office visits, it would have significant implications for practices, providers, and patients. Providers might be discouraged from offering virtual care, leading to a disparity in the availability of telehealth services, with patients in some areas or with certain conditions having limited access. Additionally, not all patients have access to a smartphone or stable internet. Research has shown increased use of audio-only visits among marginalized groups including African Americans, non-English speakers, older patients, those with public insurance as opposed to private insurance and patients living in rural communities and communities with low broadband access. For these patients, audio-only is a lifeline that allows them to access needed care.

Hughes HK, Hasselfeld BW, Greene JA. Health Care Access on the Line - Audio-Only Visits and Digitally Inclusive Care. N Engl J Med. 2022 Nov 17;387(20):1823-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2118292. Epub 2022 Nov 12. PMID: 36373819.

Chen J, Li KY, Andino J, Hill CE, Ng S, Steppe E, Ellimoottil C. Predictors of Audio-Only Versus Video Telehealth Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Apr;37(5):1138-1144. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07172-y. Epub 2021 Nov 17. PMID: 34791589; PMCID: PMC8597874.

If payment for audio-only is significantly less than in-person office E/M payments, practices may not offer this option furthering health care inequities.

Beyond the extensive preparation needed and the financial implications, there could be impacts to coverage policies. Currently, telemedicine coverage is triggered by reporting the appropriate office E/M level visit with telemedicine modifier 95. If the new telemedicine codes are no longer tied to the in-person codes, laws requiring payers to provide coverage and parity may need to be adjusted accordingly or they could become less effective. If coverage parity is not maintained, that may lead to changes in practice that could also worsen access and health disparities. Some insurers have already started rolling back coverages. Recently, Aetna decided to stop covering telemedicine visits as of Dec. 1, 2023.

Other insurers may follow suit.

As practices prepare for 2024, tracking insurance coverage policies for telemedicine, staying alert for information from the AMA about the new telemedicine CPT codes, and monitoring the proposed payments for telemedicine that CMS will release in late June to early July in the 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule will be important. Participation in advocacy efforts will be critical once the full details are released by the AMA and CMS about the new telemedicine codes and their proposed values. The AGA is monitoring this issue and will continue to fight to reduce burden to physicians and practices, which includes fighting for payment parity with in-person office E/M visits and maintaining coverage benefits for patients.

The authors have reported no conflicts of interest.

. The AMA says the new codes are designed to bring the coding system up to date with the changing landscape of health care and reflect the realities of modern medical practice.

The 17 new CPT codes will encompass a variety of telemedicine services. While the official language of the codes has not been released yet, codes for telemedicine visits using a real-time audio-visual platform could be organized similarly to existing office/outpatient E/M visits (99202-99205, 99212-99215). As part of these revisions, the current telephone E/M codes (99441-99443) will be deleted and replaced with new codes for audio-only E/M.

Implementation of so many codes will require health care providers and systems to adapt their documentation and coding practices. Typically, the exact language and code numbers for new and revised codes are not released to the public until fall of the preceding year, leaving only a few months for practices to educate their physicians and coding staff and prepare their internal systems for implementation starting Jan. 1, 2025. However, given the significant education and systems changes that will be necessary to prepare for so many new codes, we will advocate that the AMA release this information in early 2024.

Additionally, the reimbursement for telemedicine services may not ultimately be the same as for in-person E/M office visits. The AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) provides recommendations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for consideration in developing Relative Value Units (RVUs) for new procedures, including the telemedicine codes. The RUC’s recommendations for the telemedicine codes are not yet publicly available. However, it is important to note that regardless of the RUC recommendations, CMS makes all final decisions about Medicare payment. CMS could decide to set the payments for the telemedicine codes at parity with in-person office E/M visits or less than, more than, or some combination at the individual code level.

If payments for telemedicine visits are set at parity with or higher than office E/M visits, practices can focus primarily on physician and staff education and system implementation of the new codes. However, if telemedicine visit payments are less than in-person E/M office visits, it would have significant implications for practices, providers, and patients. Providers might be discouraged from offering virtual care, leading to a disparity in the availability of telehealth services, with patients in some areas or with certain conditions having limited access. Additionally, not all patients have access to a smartphone or stable internet. Research has shown increased use of audio-only visits among marginalized groups including African Americans, non-English speakers, older patients, those with public insurance as opposed to private insurance and patients living in rural communities and communities with low broadband access. For these patients, audio-only is a lifeline that allows them to access needed care.

Hughes HK, Hasselfeld BW, Greene JA. Health Care Access on the Line - Audio-Only Visits and Digitally Inclusive Care. N Engl J Med. 2022 Nov 17;387(20):1823-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2118292. Epub 2022 Nov 12. PMID: 36373819.

Chen J, Li KY, Andino J, Hill CE, Ng S, Steppe E, Ellimoottil C. Predictors of Audio-Only Versus Video Telehealth Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Apr;37(5):1138-1144. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07172-y. Epub 2021 Nov 17. PMID: 34791589; PMCID: PMC8597874.

If payment for audio-only is significantly less than in-person office E/M payments, practices may not offer this option furthering health care inequities.

Beyond the extensive preparation needed and the financial implications, there could be impacts to coverage policies. Currently, telemedicine coverage is triggered by reporting the appropriate office E/M level visit with telemedicine modifier 95. If the new telemedicine codes are no longer tied to the in-person codes, laws requiring payers to provide coverage and parity may need to be adjusted accordingly or they could become less effective. If coverage parity is not maintained, that may lead to changes in practice that could also worsen access and health disparities. Some insurers have already started rolling back coverages. Recently, Aetna decided to stop covering telemedicine visits as of Dec. 1, 2023.

Other insurers may follow suit.

As practices prepare for 2024, tracking insurance coverage policies for telemedicine, staying alert for information from the AMA about the new telemedicine CPT codes, and monitoring the proposed payments for telemedicine that CMS will release in late June to early July in the 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule will be important. Participation in advocacy efforts will be critical once the full details are released by the AMA and CMS about the new telemedicine codes and their proposed values. The AGA is monitoring this issue and will continue to fight to reduce burden to physicians and practices, which includes fighting for payment parity with in-person office E/M visits and maintaining coverage benefits for patients.

The authors have reported no conflicts of interest.

. The AMA says the new codes are designed to bring the coding system up to date with the changing landscape of health care and reflect the realities of modern medical practice.

The 17 new CPT codes will encompass a variety of telemedicine services. While the official language of the codes has not been released yet, codes for telemedicine visits using a real-time audio-visual platform could be organized similarly to existing office/outpatient E/M visits (99202-99205, 99212-99215). As part of these revisions, the current telephone E/M codes (99441-99443) will be deleted and replaced with new codes for audio-only E/M.

Implementation of so many codes will require health care providers and systems to adapt their documentation and coding practices. Typically, the exact language and code numbers for new and revised codes are not released to the public until fall of the preceding year, leaving only a few months for practices to educate their physicians and coding staff and prepare their internal systems for implementation starting Jan. 1, 2025. However, given the significant education and systems changes that will be necessary to prepare for so many new codes, we will advocate that the AMA release this information in early 2024.

Additionally, the reimbursement for telemedicine services may not ultimately be the same as for in-person E/M office visits. The AMA/Specialty Society RVS Update Committee (RUC) provides recommendations to the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) for consideration in developing Relative Value Units (RVUs) for new procedures, including the telemedicine codes. The RUC’s recommendations for the telemedicine codes are not yet publicly available. However, it is important to note that regardless of the RUC recommendations, CMS makes all final decisions about Medicare payment. CMS could decide to set the payments for the telemedicine codes at parity with in-person office E/M visits or less than, more than, or some combination at the individual code level.

If payments for telemedicine visits are set at parity with or higher than office E/M visits, practices can focus primarily on physician and staff education and system implementation of the new codes. However, if telemedicine visit payments are less than in-person E/M office visits, it would have significant implications for practices, providers, and patients. Providers might be discouraged from offering virtual care, leading to a disparity in the availability of telehealth services, with patients in some areas or with certain conditions having limited access. Additionally, not all patients have access to a smartphone or stable internet. Research has shown increased use of audio-only visits among marginalized groups including African Americans, non-English speakers, older patients, those with public insurance as opposed to private insurance and patients living in rural communities and communities with low broadband access. For these patients, audio-only is a lifeline that allows them to access needed care.

Hughes HK, Hasselfeld BW, Greene JA. Health Care Access on the Line - Audio-Only Visits and Digitally Inclusive Care. N Engl J Med. 2022 Nov 17;387(20):1823-1826. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2118292. Epub 2022 Nov 12. PMID: 36373819.

Chen J, Li KY, Andino J, Hill CE, Ng S, Steppe E, Ellimoottil C. Predictors of Audio-Only Versus Video Telehealth Visits During the COVID-19 Pandemic. J Gen Intern Med. 2022 Apr;37(5):1138-1144. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07172-y. Epub 2021 Nov 17. PMID: 34791589; PMCID: PMC8597874.

If payment for audio-only is significantly less than in-person office E/M payments, practices may not offer this option furthering health care inequities.

Beyond the extensive preparation needed and the financial implications, there could be impacts to coverage policies. Currently, telemedicine coverage is triggered by reporting the appropriate office E/M level visit with telemedicine modifier 95. If the new telemedicine codes are no longer tied to the in-person codes, laws requiring payers to provide coverage and parity may need to be adjusted accordingly or they could become less effective. If coverage parity is not maintained, that may lead to changes in practice that could also worsen access and health disparities. Some insurers have already started rolling back coverages. Recently, Aetna decided to stop covering telemedicine visits as of Dec. 1, 2023.

Other insurers may follow suit.

As practices prepare for 2024, tracking insurance coverage policies for telemedicine, staying alert for information from the AMA about the new telemedicine CPT codes, and monitoring the proposed payments for telemedicine that CMS will release in late June to early July in the 2025 Medicare Physician Fee Schedule proposed rule will be important. Participation in advocacy efforts will be critical once the full details are released by the AMA and CMS about the new telemedicine codes and their proposed values. The AGA is monitoring this issue and will continue to fight to reduce burden to physicians and practices, which includes fighting for payment parity with in-person office E/M visits and maintaining coverage benefits for patients.

The authors have reported no conflicts of interest.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and high stroke risk in Black women

I’d like to talk with you about a recent report from the large-scale Black Women’s Health Study, published in the new journal NEJM Evidence.

This study looked at the association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, and the risk for stroke over the next 20 (median, 22) years. Previous studies have linked hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with an increased risk for stroke. However, most of these studies have been done in White women of European ancestry, and evidence in Black women has been very limited, despite a disproportionately high risk of having a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and also of stroke.

– overall, a 66% increased risk, an 80% increased risk with gestational hypertension, and about a 50% increased risk with preeclampsia.

We know that pregnancy itself can lead to some remodeling of the vascular system, but we don’t know whether a direct causal relationship exists between preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and subsequent stroke. Another potential explanation is that these complications of pregnancy serve as a window into a woman’s future cardiometabolic health and a marker of her cardiovascular risk.

Regardless, the clinical implications are the same. First, we would want to prevent these complications of pregnancy whenever possible. Some women will be candidates for the use of aspirin if they are at high risk for preeclampsia, and certainly for monitoring blood pressure very closely during pregnancy. It will also be important to maintain blood pressure control in the postpartum period and during the subsequent years of adulthood to minimize risk for stroke, because hypertension is such a powerful risk factor for stroke.

It will also be tremendously important to intensify lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity and having a heart-healthy diet. These complications of pregnancy have also been linked in other studies to an increased risk for subsequent coronary heart disease events and heart failure.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Manson is professor of medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and chief of the division of preventive medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and past president, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012. She disclosed receiving study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about a recent report from the large-scale Black Women’s Health Study, published in the new journal NEJM Evidence.

This study looked at the association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, and the risk for stroke over the next 20 (median, 22) years. Previous studies have linked hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with an increased risk for stroke. However, most of these studies have been done in White women of European ancestry, and evidence in Black women has been very limited, despite a disproportionately high risk of having a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and also of stroke.

– overall, a 66% increased risk, an 80% increased risk with gestational hypertension, and about a 50% increased risk with preeclampsia.

We know that pregnancy itself can lead to some remodeling of the vascular system, but we don’t know whether a direct causal relationship exists between preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and subsequent stroke. Another potential explanation is that these complications of pregnancy serve as a window into a woman’s future cardiometabolic health and a marker of her cardiovascular risk.

Regardless, the clinical implications are the same. First, we would want to prevent these complications of pregnancy whenever possible. Some women will be candidates for the use of aspirin if they are at high risk for preeclampsia, and certainly for monitoring blood pressure very closely during pregnancy. It will also be important to maintain blood pressure control in the postpartum period and during the subsequent years of adulthood to minimize risk for stroke, because hypertension is such a powerful risk factor for stroke.

It will also be tremendously important to intensify lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity and having a heart-healthy diet. These complications of pregnancy have also been linked in other studies to an increased risk for subsequent coronary heart disease events and heart failure.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Manson is professor of medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and chief of the division of preventive medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and past president, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012. She disclosed receiving study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about a recent report from the large-scale Black Women’s Health Study, published in the new journal NEJM Evidence.

This study looked at the association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, and the risk for stroke over the next 20 (median, 22) years. Previous studies have linked hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with an increased risk for stroke. However, most of these studies have been done in White women of European ancestry, and evidence in Black women has been very limited, despite a disproportionately high risk of having a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and also of stroke.

– overall, a 66% increased risk, an 80% increased risk with gestational hypertension, and about a 50% increased risk with preeclampsia.

We know that pregnancy itself can lead to some remodeling of the vascular system, but we don’t know whether a direct causal relationship exists between preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and subsequent stroke. Another potential explanation is that these complications of pregnancy serve as a window into a woman’s future cardiometabolic health and a marker of her cardiovascular risk.

Regardless, the clinical implications are the same. First, we would want to prevent these complications of pregnancy whenever possible. Some women will be candidates for the use of aspirin if they are at high risk for preeclampsia, and certainly for monitoring blood pressure very closely during pregnancy. It will also be important to maintain blood pressure control in the postpartum period and during the subsequent years of adulthood to minimize risk for stroke, because hypertension is such a powerful risk factor for stroke.

It will also be tremendously important to intensify lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity and having a heart-healthy diet. These complications of pregnancy have also been linked in other studies to an increased risk for subsequent coronary heart disease events and heart failure.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Manson is professor of medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and chief of the division of preventive medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and past president, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012. She disclosed receiving study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Even one night in the ED raises risk for death

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

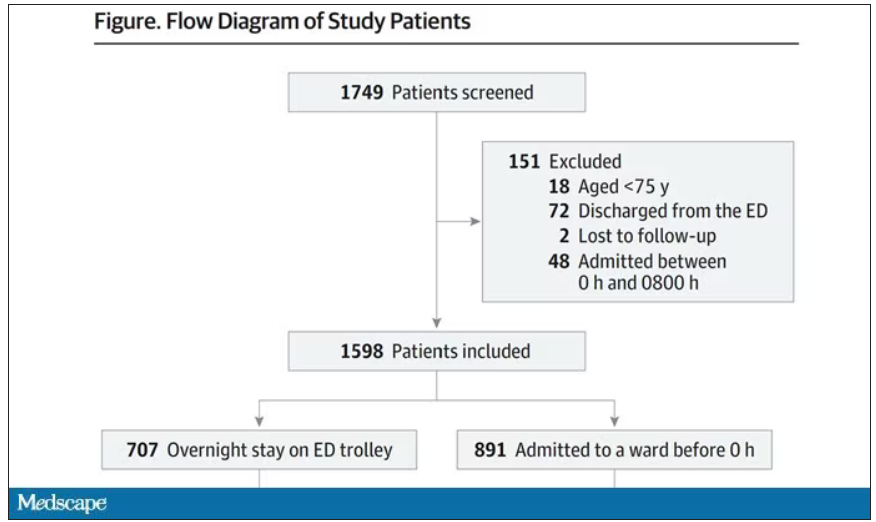

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

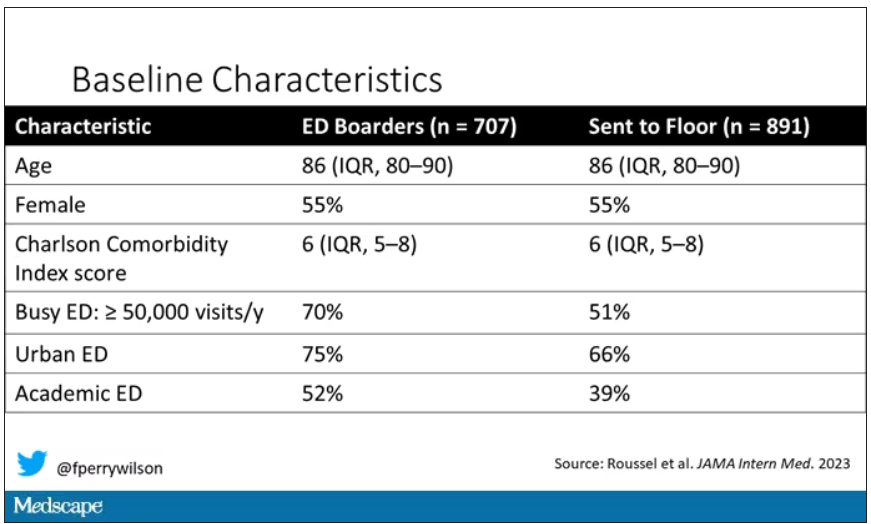

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The placebo effect

As I noted in my last column, I recently had a generic cold.

One of the more irritating aspects is that I usually get a cough that lasts a few weeks afterwards, and, like most people, I try to do something about it. So I load up on various over-the-counter remedies.

I have no idea if they work, or if I’m shelling out for a placebo. I’m not alone in buying these, or they wouldn’t be on the market, or making money, at all.

But the placebo effect is pretty strong. Phenylephrine has been around since 1938. It’s sold on its own and is an ingredient in almost every anti-cough/cold combination medication out there (NyQuil, DayQuil, Robitussin Multi-Symptom, and their many generic store brands). Millions of people use it every year.

Yet, after sifting through piles of accumulated data, the Food and Drug Administration announced earlier this year that phenylephrine ... doesn’t do anything. Zip. Zero. Nada. When compared with a placebo in controlled trials, you couldn’t tell the difference between them. So now the use of it is being questioned. CVS has started pulling it off their shelves, and I suspect other pharmacies will follow.

But back to my cough. A time-honored tradition in American childhood is having to cram down Robitussin and gagging from its nasty taste (the cherry and orange flavoring don’t make a difference, it tastes terrible no matter what you do). So that gets ingrained into us, and to this day I, and most adults, reach for a bottle of dextromethorphan when they have a cough.

But the evidence for that is spotty, too. Several studies have shown equivocal, if any, evidence to suggest it helps with coughs, though others have shown some. Nothing really amazing though.

But we still buy it by the gallon when we’re sick, because we want something, anything, that will make us better. Even if we’re doing so more from hope than conviction.

There’s also the old standby of cough drops, which have been used for more than 3,000 years. Ingredients vary, but menthol is probably the most common one. I go through those, too. I keep a bag in my desk at work. In medical school, during cold season, it was in my backpack. I remember sitting in the Creighton library to study, quietly sucking on a lozenge to keep my cough from disturbing other students.

But even then, the evidence is iffy as to whether they do anything. In fact, one interesting (though small) study in 2018 suggested they may actually prolong coughs.

The fact is that we are all susceptible to the placebo effect, regardless of how much we know about illness and medication. Maybe these things work, maybe they don’t, but it’s a valid question. How often do we let wishful thinking beat objective data?

Probably more often than we want to admit.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

As I noted in my last column, I recently had a generic cold.

One of the more irritating aspects is that I usually get a cough that lasts a few weeks afterwards, and, like most people, I try to do something about it. So I load up on various over-the-counter remedies.

I have no idea if they work, or if I’m shelling out for a placebo. I’m not alone in buying these, or they wouldn’t be on the market, or making money, at all.

But the placebo effect is pretty strong. Phenylephrine has been around since 1938. It’s sold on its own and is an ingredient in almost every anti-cough/cold combination medication out there (NyQuil, DayQuil, Robitussin Multi-Symptom, and their many generic store brands). Millions of people use it every year.

Yet, after sifting through piles of accumulated data, the Food and Drug Administration announced earlier this year that phenylephrine ... doesn’t do anything. Zip. Zero. Nada. When compared with a placebo in controlled trials, you couldn’t tell the difference between them. So now the use of it is being questioned. CVS has started pulling it off their shelves, and I suspect other pharmacies will follow.

But back to my cough. A time-honored tradition in American childhood is having to cram down Robitussin and gagging from its nasty taste (the cherry and orange flavoring don’t make a difference, it tastes terrible no matter what you do). So that gets ingrained into us, and to this day I, and most adults, reach for a bottle of dextromethorphan when they have a cough.

But the evidence for that is spotty, too. Several studies have shown equivocal, if any, evidence to suggest it helps with coughs, though others have shown some. Nothing really amazing though.

But we still buy it by the gallon when we’re sick, because we want something, anything, that will make us better. Even if we’re doing so more from hope than conviction.

There’s also the old standby of cough drops, which have been used for more than 3,000 years. Ingredients vary, but menthol is probably the most common one. I go through those, too. I keep a bag in my desk at work. In medical school, during cold season, it was in my backpack. I remember sitting in the Creighton library to study, quietly sucking on a lozenge to keep my cough from disturbing other students.

But even then, the evidence is iffy as to whether they do anything. In fact, one interesting (though small) study in 2018 suggested they may actually prolong coughs.

The fact is that we are all susceptible to the placebo effect, regardless of how much we know about illness and medication. Maybe these things work, maybe they don’t, but it’s a valid question. How often do we let wishful thinking beat objective data?

Probably more often than we want to admit.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

As I noted in my last column, I recently had a generic cold.

One of the more irritating aspects is that I usually get a cough that lasts a few weeks afterwards, and, like most people, I try to do something about it. So I load up on various over-the-counter remedies.

I have no idea if they work, or if I’m shelling out for a placebo. I’m not alone in buying these, or they wouldn’t be on the market, or making money, at all.

But the placebo effect is pretty strong. Phenylephrine has been around since 1938. It’s sold on its own and is an ingredient in almost every anti-cough/cold combination medication out there (NyQuil, DayQuil, Robitussin Multi-Symptom, and their many generic store brands). Millions of people use it every year.

Yet, after sifting through piles of accumulated data, the Food and Drug Administration announced earlier this year that phenylephrine ... doesn’t do anything. Zip. Zero. Nada. When compared with a placebo in controlled trials, you couldn’t tell the difference between them. So now the use of it is being questioned. CVS has started pulling it off their shelves, and I suspect other pharmacies will follow.

But back to my cough. A time-honored tradition in American childhood is having to cram down Robitussin and gagging from its nasty taste (the cherry and orange flavoring don’t make a difference, it tastes terrible no matter what you do). So that gets ingrained into us, and to this day I, and most adults, reach for a bottle of dextromethorphan when they have a cough.

But the evidence for that is spotty, too. Several studies have shown equivocal, if any, evidence to suggest it helps with coughs, though others have shown some. Nothing really amazing though.

But we still buy it by the gallon when we’re sick, because we want something, anything, that will make us better. Even if we’re doing so more from hope than conviction.

There’s also the old standby of cough drops, which have been used for more than 3,000 years. Ingredients vary, but menthol is probably the most common one. I go through those, too. I keep a bag in my desk at work. In medical school, during cold season, it was in my backpack. I remember sitting in the Creighton library to study, quietly sucking on a lozenge to keep my cough from disturbing other students.

But even then, the evidence is iffy as to whether they do anything. In fact, one interesting (though small) study in 2018 suggested they may actually prolong coughs.

The fact is that we are all susceptible to the placebo effect, regardless of how much we know about illness and medication. Maybe these things work, maybe they don’t, but it’s a valid question. How often do we let wishful thinking beat objective data?

Probably more often than we want to admit.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Knowing when enough is enough

“On which side of the bed did you get up this morning?” Obviously, your inquisitor assumes that to avoid clumsily crawling over your sleeping partner you always get up on the side with the table stacked with unread books.

You know as well as I do that you have just received a totally undisguised comment on your recent behavior that has been several shades less than cheery. You may have already sensed your own grumpiness. Do you have an explanation? Did the commute leave you with a case of unresolved road rage? Did you wake up feeling unrested? How often does that happen? Do you think you are getting enough sleep?

A few weeks ago I wrote a Letters From Maine column in which I shared a study suggesting that the regularity of an individual’s sleep pattern may, in many cases, be more important than his or her total number of hours slept. In that same column I wrote that sleep scientists don’t as yet have a good definition of sleep irregularity, nor can they give us any more than a broad range for the total number of hours a person needs to maintain wellness.

How do you determine whether you are getting enough sleep? Do you keep a chart of how many times you were asked which side of the bed you got up on in a week? Or is it how you feel in the morning? Is it when you instantly doze off any time you sit down in a quiet place?

Although many adults are clueless (or in denial) that they are sleep deprived, generally if you ask them and take a brief history they will tell you. On the other hand, determining when a child, particularly one who is preverbal, is sleep deprived is a bit more difficult. Asking the patient isn’t going to give you the answer. You must rely on parental observations. And, to some extent, this can be difficult because parents are, by definition, learning on the job. They may not realize the symptoms and behaviors they are seeing in their child are the result of sleep deficiency.

Over the last half century of observing children, I have developed a very low threshold for diagnosing sleep deprivation. Basically, any child who is cranky and not obviously sick is overtired until proven otherwise. For example, colic does not appear on my frequently used, or in fact ever used, list of diagnoses. Colicky is an adjective that I may use to describe some episodic pain or behavior, but colic as a working diagnosis? Never.

When presented with a child who has already been diagnosed with “colic” by its aunt or the lady next door, this is when the astute pediatrician must be at his or her best. If a thorough history, including sleep pattern, yields no obvious evidence of illness, the next step should be some sleep coaching. However, this is where the “until proven otherwise” thing becomes important, because not providing close follow-up and continuing to keep an open mind for the less likely coexisting conditions can be dangerous and certainly not in the patient’s best interest.

For the older child crankiness, temper tantrums, mood disorders and signs and symptoms often (some might say too often) associated with attention-deficit disorder should trigger an immediate investigation of sleep habits and appropriate advice. Less well-known conditions associated with sleep deprivation are migraine and nocturnal leg pains, often mislabeled as growing pains.

The physicians planning on using sleep as a therapeutic modality is going to quickly run into several challenges. First is convincing the parents, the patient, and the family that the condition is to a greater or lesser degree the result of sleep deprivation. Because sleep is still underappreciated as a component of wellness, this is often not an easy sell.

Second, everyone must accept that altering sleep patterns regardless of age is often not easy and will not be achieved in 1 night or 2. Keeping up the drumbeat of encouragement with close follow-up is critical. Parents must be continually reminded that sleep is being used as a medicine and the dose is not measured in hours. The improvement in symptoms will tell us when enough is enough.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

“On which side of the bed did you get up this morning?” Obviously, your inquisitor assumes that to avoid clumsily crawling over your sleeping partner you always get up on the side with the table stacked with unread books.

You know as well as I do that you have just received a totally undisguised comment on your recent behavior that has been several shades less than cheery. You may have already sensed your own grumpiness. Do you have an explanation? Did the commute leave you with a case of unresolved road rage? Did you wake up feeling unrested? How often does that happen? Do you think you are getting enough sleep?

A few weeks ago I wrote a Letters From Maine column in which I shared a study suggesting that the regularity of an individual’s sleep pattern may, in many cases, be more important than his or her total number of hours slept. In that same column I wrote that sleep scientists don’t as yet have a good definition of sleep irregularity, nor can they give us any more than a broad range for the total number of hours a person needs to maintain wellness.

How do you determine whether you are getting enough sleep? Do you keep a chart of how many times you were asked which side of the bed you got up on in a week? Or is it how you feel in the morning? Is it when you instantly doze off any time you sit down in a quiet place?

Although many adults are clueless (or in denial) that they are sleep deprived, generally if you ask them and take a brief history they will tell you. On the other hand, determining when a child, particularly one who is preverbal, is sleep deprived is a bit more difficult. Asking the patient isn’t going to give you the answer. You must rely on parental observations. And, to some extent, this can be difficult because parents are, by definition, learning on the job. They may not realize the symptoms and behaviors they are seeing in their child are the result of sleep deficiency.

Over the last half century of observing children, I have developed a very low threshold for diagnosing sleep deprivation. Basically, any child who is cranky and not obviously sick is overtired until proven otherwise. For example, colic does not appear on my frequently used, or in fact ever used, list of diagnoses. Colicky is an adjective that I may use to describe some episodic pain or behavior, but colic as a working diagnosis? Never.

When presented with a child who has already been diagnosed with “colic” by its aunt or the lady next door, this is when the astute pediatrician must be at his or her best. If a thorough history, including sleep pattern, yields no obvious evidence of illness, the next step should be some sleep coaching. However, this is where the “until proven otherwise” thing becomes important, because not providing close follow-up and continuing to keep an open mind for the less likely coexisting conditions can be dangerous and certainly not in the patient’s best interest.

For the older child crankiness, temper tantrums, mood disorders and signs and symptoms often (some might say too often) associated with attention-deficit disorder should trigger an immediate investigation of sleep habits and appropriate advice. Less well-known conditions associated with sleep deprivation are migraine and nocturnal leg pains, often mislabeled as growing pains.

The physicians planning on using sleep as a therapeutic modality is going to quickly run into several challenges. First is convincing the parents, the patient, and the family that the condition is to a greater or lesser degree the result of sleep deprivation. Because sleep is still underappreciated as a component of wellness, this is often not an easy sell.

Second, everyone must accept that altering sleep patterns regardless of age is often not easy and will not be achieved in 1 night or 2. Keeping up the drumbeat of encouragement with close follow-up is critical. Parents must be continually reminded that sleep is being used as a medicine and the dose is not measured in hours. The improvement in symptoms will tell us when enough is enough.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

“On which side of the bed did you get up this morning?” Obviously, your inquisitor assumes that to avoid clumsily crawling over your sleeping partner you always get up on the side with the table stacked with unread books.

You know as well as I do that you have just received a totally undisguised comment on your recent behavior that has been several shades less than cheery. You may have already sensed your own grumpiness. Do you have an explanation? Did the commute leave you with a case of unresolved road rage? Did you wake up feeling unrested? How often does that happen? Do you think you are getting enough sleep?

A few weeks ago I wrote a Letters From Maine column in which I shared a study suggesting that the regularity of an individual’s sleep pattern may, in many cases, be more important than his or her total number of hours slept. In that same column I wrote that sleep scientists don’t as yet have a good definition of sleep irregularity, nor can they give us any more than a broad range for the total number of hours a person needs to maintain wellness.

How do you determine whether you are getting enough sleep? Do you keep a chart of how many times you were asked which side of the bed you got up on in a week? Or is it how you feel in the morning? Is it when you instantly doze off any time you sit down in a quiet place?

Although many adults are clueless (or in denial) that they are sleep deprived, generally if you ask them and take a brief history they will tell you. On the other hand, determining when a child, particularly one who is preverbal, is sleep deprived is a bit more difficult. Asking the patient isn’t going to give you the answer. You must rely on parental observations. And, to some extent, this can be difficult because parents are, by definition, learning on the job. They may not realize the symptoms and behaviors they are seeing in their child are the result of sleep deficiency.

Over the last half century of observing children, I have developed a very low threshold for diagnosing sleep deprivation. Basically, any child who is cranky and not obviously sick is overtired until proven otherwise. For example, colic does not appear on my frequently used, or in fact ever used, list of diagnoses. Colicky is an adjective that I may use to describe some episodic pain or behavior, but colic as a working diagnosis? Never.

When presented with a child who has already been diagnosed with “colic” by its aunt or the lady next door, this is when the astute pediatrician must be at his or her best. If a thorough history, including sleep pattern, yields no obvious evidence of illness, the next step should be some sleep coaching. However, this is where the “until proven otherwise” thing becomes important, because not providing close follow-up and continuing to keep an open mind for the less likely coexisting conditions can be dangerous and certainly not in the patient’s best interest.

For the older child crankiness, temper tantrums, mood disorders and signs and symptoms often (some might say too often) associated with attention-deficit disorder should trigger an immediate investigation of sleep habits and appropriate advice. Less well-known conditions associated with sleep deprivation are migraine and nocturnal leg pains, often mislabeled as growing pains.

The physicians planning on using sleep as a therapeutic modality is going to quickly run into several challenges. First is convincing the parents, the patient, and the family that the condition is to a greater or lesser degree the result of sleep deprivation. Because sleep is still underappreciated as a component of wellness, this is often not an easy sell.

Second, everyone must accept that altering sleep patterns regardless of age is often not easy and will not be achieved in 1 night or 2. Keeping up the drumbeat of encouragement with close follow-up is critical. Parents must be continually reminded that sleep is being used as a medicine and the dose is not measured in hours. The improvement in symptoms will tell us when enough is enough.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “How to Say No to Your Toddler.” Other than a Littman stethoscope he accepted as a first-year medical student in 1966, Dr. Wilkoff reports having nothing to disclose. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

525,600 minutes ... how does one measure a year as President?

For the first time since CHEST 2011, when I was the Scientific Program Committee Vice Chair, I was able to return to beautiful Hawaiʻi as the organization’s President, which was such a big coincidence that it felt almost like fate.

During my time on stage at the CHEST 2023 Opening Session, I reflected on the last (at the time) 9 months and shared how truly humbled I have been to lead such a group of leaders and doers. I’m continually amazed at the energy of our members and our staff. In my 25 years as a member, I thought I knew all that CHEST did, but there is so much more happening than any one person realizes. From creating and implementing patient care initiatives to drafting and endorsing statements advocating for better access to health care, there is a tremendous amount accomplished by this organization every year.

One notable accomplishment of this particular year is that not only was CHEST 2023 our largest meeting ever, but I’m proud to share that we also had more medical students, residents, and fellows than any other year, with over 2,000 attendees in-training.

This is a great reflection of the work we’ve been doing to expand the CHEST community – both to physicians earlier in their careers and also to the whole care team. We are putting a dedicated focus toward welcoming and creating a sense of belonging for every clinician. The first step toward this inclusion is the creation of the new CHEST interest groups – Respiratory Care, which is dedicated to the field, and Women in Chest Medicine, which is a more inclusive evolution of the previous Women & Pulmonary group.

This year, we also established CHEST organizational values. The result of a tremendous effort from an advisory committee, CHEST leaders, members, and staff, these values – Community, Inclusivity, Innovation, Advocacy, and Integrity – are reflective of the CHEST organization and will guide decisions for years to come.

They also serve to elevate the work we are doing in social responsibility and health equity, within both of which we’ve made great strides. CHEST philanthropy evolved from what was known as the CHEST Foundation, with a new strategic focus, and we continue working to create opportunities to expand diversity within health care, including the new CHEST mentor/mentee sponsorship fellowship in partnership with the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors.

Though I could go on for eternity describing all we did at CHEST this year, the reality is that at the end of the next month, as we ring in the new year, I will cede the presidency to the incredibly accomplished and capable Jack Buckley, MD, MPH, FCCP, who will take the reins of our great organization.

For now, in my parting words to you, I encourage everyone to stay in touch. I am always reachable by email and would love to hear your thoughts on CHEST – reflections on this past year, ideas about where we’re going, and suggestions for what we’re missing. The role of the President (and, to some extent, the Immediate Past President) is to be a steward of the needs of the CHEST members, and it’s been a true honor being your 2023 CHEST President.

For the first time since CHEST 2011, when I was the Scientific Program Committee Vice Chair, I was able to return to beautiful Hawaiʻi as the organization’s President, which was such a big coincidence that it felt almost like fate.

During my time on stage at the CHEST 2023 Opening Session, I reflected on the last (at the time) 9 months and shared how truly humbled I have been to lead such a group of leaders and doers. I’m continually amazed at the energy of our members and our staff. In my 25 years as a member, I thought I knew all that CHEST did, but there is so much more happening than any one person realizes. From creating and implementing patient care initiatives to drafting and endorsing statements advocating for better access to health care, there is a tremendous amount accomplished by this organization every year.

One notable accomplishment of this particular year is that not only was CHEST 2023 our largest meeting ever, but I’m proud to share that we also had more medical students, residents, and fellows than any other year, with over 2,000 attendees in-training.

This is a great reflection of the work we’ve been doing to expand the CHEST community – both to physicians earlier in their careers and also to the whole care team. We are putting a dedicated focus toward welcoming and creating a sense of belonging for every clinician. The first step toward this inclusion is the creation of the new CHEST interest groups – Respiratory Care, which is dedicated to the field, and Women in Chest Medicine, which is a more inclusive evolution of the previous Women & Pulmonary group.

This year, we also established CHEST organizational values. The result of a tremendous effort from an advisory committee, CHEST leaders, members, and staff, these values – Community, Inclusivity, Innovation, Advocacy, and Integrity – are reflective of the CHEST organization and will guide decisions for years to come.

They also serve to elevate the work we are doing in social responsibility and health equity, within both of which we’ve made great strides. CHEST philanthropy evolved from what was known as the CHEST Foundation, with a new strategic focus, and we continue working to create opportunities to expand diversity within health care, including the new CHEST mentor/mentee sponsorship fellowship in partnership with the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors.

Though I could go on for eternity describing all we did at CHEST this year, the reality is that at the end of the next month, as we ring in the new year, I will cede the presidency to the incredibly accomplished and capable Jack Buckley, MD, MPH, FCCP, who will take the reins of our great organization.

For now, in my parting words to you, I encourage everyone to stay in touch. I am always reachable by email and would love to hear your thoughts on CHEST – reflections on this past year, ideas about where we’re going, and suggestions for what we’re missing. The role of the President (and, to some extent, the Immediate Past President) is to be a steward of the needs of the CHEST members, and it’s been a true honor being your 2023 CHEST President.

For the first time since CHEST 2011, when I was the Scientific Program Committee Vice Chair, I was able to return to beautiful Hawaiʻi as the organization’s President, which was such a big coincidence that it felt almost like fate.

During my time on stage at the CHEST 2023 Opening Session, I reflected on the last (at the time) 9 months and shared how truly humbled I have been to lead such a group of leaders and doers. I’m continually amazed at the energy of our members and our staff. In my 25 years as a member, I thought I knew all that CHEST did, but there is so much more happening than any one person realizes. From creating and implementing patient care initiatives to drafting and endorsing statements advocating for better access to health care, there is a tremendous amount accomplished by this organization every year.

One notable accomplishment of this particular year is that not only was CHEST 2023 our largest meeting ever, but I’m proud to share that we also had more medical students, residents, and fellows than any other year, with over 2,000 attendees in-training.

This is a great reflection of the work we’ve been doing to expand the CHEST community – both to physicians earlier in their careers and also to the whole care team. We are putting a dedicated focus toward welcoming and creating a sense of belonging for every clinician. The first step toward this inclusion is the creation of the new CHEST interest groups – Respiratory Care, which is dedicated to the field, and Women in Chest Medicine, which is a more inclusive evolution of the previous Women & Pulmonary group.

This year, we also established CHEST organizational values. The result of a tremendous effort from an advisory committee, CHEST leaders, members, and staff, these values – Community, Inclusivity, Innovation, Advocacy, and Integrity – are reflective of the CHEST organization and will guide decisions for years to come.

They also serve to elevate the work we are doing in social responsibility and health equity, within both of which we’ve made great strides. CHEST philanthropy evolved from what was known as the CHEST Foundation, with a new strategic focus, and we continue working to create opportunities to expand diversity within health care, including the new CHEST mentor/mentee sponsorship fellowship in partnership with the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors.

Though I could go on for eternity describing all we did at CHEST this year, the reality is that at the end of the next month, as we ring in the new year, I will cede the presidency to the incredibly accomplished and capable Jack Buckley, MD, MPH, FCCP, who will take the reins of our great organization.

For now, in my parting words to you, I encourage everyone to stay in touch. I am always reachable by email and would love to hear your thoughts on CHEST – reflections on this past year, ideas about where we’re going, and suggestions for what we’re missing. The role of the President (and, to some extent, the Immediate Past President) is to be a steward of the needs of the CHEST members, and it’s been a true honor being your 2023 CHEST President.

New pharmacological interventions for residual excessive daytime sleepiness in OSA

Residual excessive daytime sleepiness (REDS) is defined as the urge to sleep during the day despite an intention to remain alert after optimal treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). This is a distressing outcome with an estimated prevalence of 9% to 22% among patients with OSA (Pépin JL, et al. Eur Respir J. 2009;33[5]:1062). The pathophysiology of the condition is complex, and experimental studies conducted on animal models have demonstrated that chronic sleep fragmentation and chronic intermittent hypoxia can result in detrimental effects on wake-promoting neurons. Additionally, there is evidence of heightened oxidative stress and alterations in melatonin secretion, with the severity and duration of the disease playing a significant role in the manifestation of these effects (Javaheri S, et al. Chest. 2020;158[2]:776). It is considered a diagnosis of exclusion, with the assessment being mostly subjective. Prior to diagnosing REDS, it is crucial to optimize positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy and nocturnal ventilation, ensure sufficient adherence to sleep hygiene practices, and exclude the presence of other sleep disorders. The Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score is widely utilized as a primary clinical tool in the assessment of sleepiness. To enhance the precision of this score, it is advantageous to take input from both family members and friends. Additional objective assessments that could be considered include the utilization of the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT) or the Maintenance of Wakefulness Test (MWT).

Off-label use of traditional central nervous system stimulants, like amphetamine or methylphenidate, in these patients is almost extinct. The potential for abuse and negative consequences outweighs the potential benefits. FDA-approved medications for treatment of REDS in OSA include modafinil, armodafinil, and solriamfetol in the United States.

Historically, modafinil and armodafinil are the first-line and most commonly used wake-promoting agents. Both agents bind to the dopamine transporter and inhibit dopamine reuptake. They have demonstrated efficacy in reducing EDS and improving wakefulness in patients with OSA treated with CPAP. A meta-analysis of 10 randomized, placebo-controlled trials of modafinil and armodafinil found that they were better than placebo by 2.2 points on the ESS score and 3 minutes on the MWT (Maintenance of Wakefulness Test) (Chapman JL, et al. Eur Respir J. 2016;47[5]:1420). Both drugs have common adverse effects of headache, nausea, nervousness, insomnia, dizziness, rhinitis, and diarrhea. Drug interaction with CYP3A4/5 substrates and oral contraceptives is a concern with these medications. In 2010, the European Medicines Agency restricted the use of modafinil only to patients with narcolepsy, considering its cardiovascular and neuropsychiatric risks (European Medicines Agency website; press release, July 22, 2010).

Solriamfetol is the newest medication being utilized for EDS in OSA and is approved in both the United States and Europe for this indication. It is a dopamine and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor with a simultaneous effect on both transporters. It has been effective in improving wakefulness and reducing sleepiness in patients with residual OSA. In the landmark trial TONES 3, dose-dependent (37.5, 75, 150, and 300 mg/day) effects were observed, with improvements in ESS scores of –1.9 to –4.7 points and sleep latency in MWT by 4.5 to 12.8 minutes (Schweitzer PK, et al. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199[11]:1421). The current recommended dosing for REDS in OSA is to start with the lowest dose of 37.5 mg/day and increase to the maximum dose of 150 mg/day by titrating up every 3 days if needed. A recent meta-analysis showed an indirect treatment comparison between efficacy and safety among the medications solriamfetol, modafinil, and armodafinil (Ronnebaum S, et al. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021;17[12]:2543). Six parallel-arm, placebo-controlled, randomized, controlled trials were looked at. The ESS score, MWT20 sleep latency, and CGI-C (Clinical Global Impression of Change) all got better in comparison to the placebo. Relative to the comparators and placebo at 12 weeks, solriamfetol at 150 mg and 300 mg had the highest degree of improvement in all the outcomes studied. Common adverse effects of solriamfetol include headache, nausea, decreased appetite, insomnia, dry mouth, anxiety, and minimal increase in blood pressure and heart rate. The adverse effects in terms of blood pressure and heart rate change have a dose-dependent relationship, and serial vitals monitoring is recommended for patients every 6 months to a year. This medication is contraindicated in patients receiving concomitant monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) or within 14 days following discontinuation of an MAOI because of the risk of hypertensive reactions. Solriamfetol is renally excreted, so dose adjustment is needed in patients with moderate to severe renal impairment. It is not recommended for use in end-stage renal disease (eGFR <15 mL/min/1.73 m2) (SUNOSI. Full prescribing information. Axsome; revised 06/2023. https://www.sunosihcp.com/assets/files/sunosi.en.uspi.pdf. Accessed: Sept 24, 2023). Solriamfetol demonstrates a comparatively shorter half-life when compared with traditional pharmaceuticals like modafinil and armodafinil, implying the possibility of a decreased duration of its effects. The effect in question may exhibit interpersonal diversity in its impact on quality of life when applied in a therapeutic setting.