User login

Overuse of Digital Devices in the Exam Room: A Teaching Opportunity

A 3-year-old presents to my clinic for evaluation of a possible autism spectrum disorder/difference. He has a history of severe emotional dysregulation, as well as reduced social skills and multiple sensory sensitivities. When I enter the exam room he is watching videos on his mom’s phone, and has some difficulty transitioning to play with toys when I encourage him to do so. He is eventually able to cooperate with my testing, though a bit reluctantly, and scores within the low average range for both language and pre-academic skills. His neurologic exam is within normal limits. He utilizes reasonably well-modulated eye contact paired with some typical use of gestures, and his affect is moderately directed and reactive. He displays typical intonation and prosody of speech, though engages in less spontaneous, imaginative, and reciprocal play than would be expected for his age. His mother reports decreased pretend play at home, minimal interest in toys, and difficulty playing cooperatively with other children.

Upon further history, it becomes apparent that the child spends a majority of his time on electronic devices, and has done so since early toddlerhood. Further dialogue suggests that the family became isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not yet re-engaged with the community in a meaningful way. The child has had rare opportunity for social interactions with other children, and minimal access to outdoor play. His most severe meltdowns generally involve transitions away from screens, and his overwhelmed parents often resort to use of additional screens to calm him once he is dysregulated.

At the end of the visit, through shared decision making, we agree that enrolling the child in a high-quality public preschool will help parents make a concerted effort towards a significant reduction in the hours per day in which the child utilizes electronic devices, while also providing him more exposure to peers. We plan for the child to return in 6 months for a re-evaluation around social-emotional skills, given his current limited exposure to peers and limited “unplugged” play-time.

Overutilization of Electronic Devices

As clinicians, we can all see how pervasive the use of electronic devices has become in the lives of the families we care for, as well as in our own lives, and how challenging some aspects of modern parenting have become. The developmental impact of early and excessive use of screens in young children is well documented,1 but as clinicians it can be tricky to help empower parents to find ways to limit screen time. When parents use screens to comfort and amuse their children during a clinic visit, this situation may serve as an excellent opportunity for a meaningful and respectful conversation around skill deficits which can result from overutilization of electronic devices in young children.

One scenario I often encounter during my patient evaluations as a developmental and behavioral pediatrician is children begging their parents for use of their phone throughout their visits with me. Not infrequently, a child is already on a screen when I enter the exam room, even when there has been a minimal wait time, which often leads to some resistance on behalf of the child as I explain to the family that a significant portion of the visit involves my interactions with the child, testing the child, and observing their child at play. I always provide ample amounts of age-appropriate art supplies, puzzles, fidgets, building toys, and imaginative play items to children during their 30 to 90 minute evaluations, but these are often not appealing to children when they have been very recently engaged with an electronic device. At times I also need to ask caretakers themselves to please disengage from their own electronic devices during the visit so that I can involve them in a detailed discussion about their child.

One challenge with the practice of allowing children access to entertainment on their parent’s smartphones in particular, lies in the fact that these devices are almost always present, meaning there is no natural boundary to inhibit access, in contrast to a television set or stationary computer parked in the family living room. Not dissimilar to candy visible in a parent’s purse, a cell phone becomes a constant temptation for children accustomed to utilizing them at home and public venues, and the incessant begging can wear down already stressed parents.

Children can become conditioned to utilize the distraction of screens to avoid feelings of discomfort or stress, and so can be very persistent and emotional when asking for the use of screens in public settings. Out in the community, I very frequently see young children and toddlers quietly staring at their phones and tablets while at restaurants and stores. While I have empathy for exhausted parents desperate for a moment of quiet, if this type of screen use is the rule rather than the exception for a child, there is risk for missed opportunities for the development of self-regulation skills.

Additionally, I have seen very young children present to my clinic with poor posture and neck pain secondary to chronic smartphone use, and young children who are getting minimal exercise or outdoor time due to excessive screen use, leading to concerns around fine and gross motor skills as well.

While allowing a child to stay occupied with or be soothed by a highly interesting digital experience can create a more calm environment for all, if habitual, this use can come at a cost regarding opportunities for the growth of executive functioning skills, general coping skills, general situational awareness, and experiential learning. Reliance on screens to decrease uncomfortable experiences decreases the opportunity for building distress tolerance, patience, and coping skills.

Of course there are times of extreme distress where a lollipop or bit of screen time might be reasonable to help keep a child safe or further avoid emotional trauma, but in general, other methods of soothing can very often be utilized, and in the long run would serve to increase the child’s general adaptive functioning.

A Teachable Moment

When clinicians encounter screens being used by parents to entertain their kids in clinic, it provides a valuable teaching moment around the risks of using screens to keep kids regulated and occupied during life’s less interesting or more anxiety provoking experiences. Having a meaningful conversation about the use of electronic devices with caregivers by clinicians in the exam room can be a delicate dance between providing supportive education while avoiding judgmental tones or verbiage. Normalizing and sympathizing with the difficulty of managing challenging behaviors from children in public spaces can help parents feel less desperate to keep their child quiet at all costs, and thus allow for greater development of coping skills.

Some parents may benefit from learning simple ideas for keeping a child regulated and occupied during times of waiting such as silly songs and dances, verbal games like “I spy,” and clapping routines. For a child with additional sensory or developmental needs, a referral to an occupational therapist to work on emotional regulation by way of specific sensory tools can be helpful. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for kids ages 2 to 7 can also help build some relational activities and skills that can be utilized during trying situations to help keep a child settled and occupied.

If a child has qualified for Developmental Disability Services (DDS), medical providers can also write “prescriptions’ for sensory calming items which are often covered financially by DDS, such as chewies, weighted vests, stuffed animals, and fidgets. Encouraging parents to schedule allowed screen time at home in a very predictable and controlled manner is one method to help limit excessive use, as well as it’s utilization as an emotional regulation tool.

For public outings with children with special needs, and in particular in situations where meltdowns are likely to occur, some families find it helpful to dress their children in clothing or accessories that increase community awareness about their child’s condition (such as an autism awareness t-shirt). This effort can also help deflect unhelpful attention or advice from the public. Some parents choose to carry small cards explaining the child’s developmental differences, which can then be easily handed to unsupportive strangers in community settings during trying moments.

Clinicians can work to utilize even quick visits with families as an opportunity to review the American Academy of Pediatrics screen time recommendations with families, and also direct them to the Family Media Plan creation resources. Parenting in the modern era presents many challenges regarding choices around the use of electronic devices with children, and using the exam room experience as a teaching opportunity may be a helpful way to decrease utilization of screens as emotional regulation tools for children, while also providing general education around healthy use of screens.

Dr. Roth is a developmental and behavioral pediatrician in Eugene, Oregon.

Reference

1. Takahashi I et al. Screen Time at Age 1 Year and Communication and Problem-Solving Developmental Delays at 2 and 4 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Oct 1;177(10):1039-1046. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3057.

A 3-year-old presents to my clinic for evaluation of a possible autism spectrum disorder/difference. He has a history of severe emotional dysregulation, as well as reduced social skills and multiple sensory sensitivities. When I enter the exam room he is watching videos on his mom’s phone, and has some difficulty transitioning to play with toys when I encourage him to do so. He is eventually able to cooperate with my testing, though a bit reluctantly, and scores within the low average range for both language and pre-academic skills. His neurologic exam is within normal limits. He utilizes reasonably well-modulated eye contact paired with some typical use of gestures, and his affect is moderately directed and reactive. He displays typical intonation and prosody of speech, though engages in less spontaneous, imaginative, and reciprocal play than would be expected for his age. His mother reports decreased pretend play at home, minimal interest in toys, and difficulty playing cooperatively with other children.

Upon further history, it becomes apparent that the child spends a majority of his time on electronic devices, and has done so since early toddlerhood. Further dialogue suggests that the family became isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not yet re-engaged with the community in a meaningful way. The child has had rare opportunity for social interactions with other children, and minimal access to outdoor play. His most severe meltdowns generally involve transitions away from screens, and his overwhelmed parents often resort to use of additional screens to calm him once he is dysregulated.

At the end of the visit, through shared decision making, we agree that enrolling the child in a high-quality public preschool will help parents make a concerted effort towards a significant reduction in the hours per day in which the child utilizes electronic devices, while also providing him more exposure to peers. We plan for the child to return in 6 months for a re-evaluation around social-emotional skills, given his current limited exposure to peers and limited “unplugged” play-time.

Overutilization of Electronic Devices

As clinicians, we can all see how pervasive the use of electronic devices has become in the lives of the families we care for, as well as in our own lives, and how challenging some aspects of modern parenting have become. The developmental impact of early and excessive use of screens in young children is well documented,1 but as clinicians it can be tricky to help empower parents to find ways to limit screen time. When parents use screens to comfort and amuse their children during a clinic visit, this situation may serve as an excellent opportunity for a meaningful and respectful conversation around skill deficits which can result from overutilization of electronic devices in young children.

One scenario I often encounter during my patient evaluations as a developmental and behavioral pediatrician is children begging their parents for use of their phone throughout their visits with me. Not infrequently, a child is already on a screen when I enter the exam room, even when there has been a minimal wait time, which often leads to some resistance on behalf of the child as I explain to the family that a significant portion of the visit involves my interactions with the child, testing the child, and observing their child at play. I always provide ample amounts of age-appropriate art supplies, puzzles, fidgets, building toys, and imaginative play items to children during their 30 to 90 minute evaluations, but these are often not appealing to children when they have been very recently engaged with an electronic device. At times I also need to ask caretakers themselves to please disengage from their own electronic devices during the visit so that I can involve them in a detailed discussion about their child.

One challenge with the practice of allowing children access to entertainment on their parent’s smartphones in particular, lies in the fact that these devices are almost always present, meaning there is no natural boundary to inhibit access, in contrast to a television set or stationary computer parked in the family living room. Not dissimilar to candy visible in a parent’s purse, a cell phone becomes a constant temptation for children accustomed to utilizing them at home and public venues, and the incessant begging can wear down already stressed parents.

Children can become conditioned to utilize the distraction of screens to avoid feelings of discomfort or stress, and so can be very persistent and emotional when asking for the use of screens in public settings. Out in the community, I very frequently see young children and toddlers quietly staring at their phones and tablets while at restaurants and stores. While I have empathy for exhausted parents desperate for a moment of quiet, if this type of screen use is the rule rather than the exception for a child, there is risk for missed opportunities for the development of self-regulation skills.

Additionally, I have seen very young children present to my clinic with poor posture and neck pain secondary to chronic smartphone use, and young children who are getting minimal exercise or outdoor time due to excessive screen use, leading to concerns around fine and gross motor skills as well.

While allowing a child to stay occupied with or be soothed by a highly interesting digital experience can create a more calm environment for all, if habitual, this use can come at a cost regarding opportunities for the growth of executive functioning skills, general coping skills, general situational awareness, and experiential learning. Reliance on screens to decrease uncomfortable experiences decreases the opportunity for building distress tolerance, patience, and coping skills.

Of course there are times of extreme distress where a lollipop or bit of screen time might be reasonable to help keep a child safe or further avoid emotional trauma, but in general, other methods of soothing can very often be utilized, and in the long run would serve to increase the child’s general adaptive functioning.

A Teachable Moment

When clinicians encounter screens being used by parents to entertain their kids in clinic, it provides a valuable teaching moment around the risks of using screens to keep kids regulated and occupied during life’s less interesting or more anxiety provoking experiences. Having a meaningful conversation about the use of electronic devices with caregivers by clinicians in the exam room can be a delicate dance between providing supportive education while avoiding judgmental tones or verbiage. Normalizing and sympathizing with the difficulty of managing challenging behaviors from children in public spaces can help parents feel less desperate to keep their child quiet at all costs, and thus allow for greater development of coping skills.

Some parents may benefit from learning simple ideas for keeping a child regulated and occupied during times of waiting such as silly songs and dances, verbal games like “I spy,” and clapping routines. For a child with additional sensory or developmental needs, a referral to an occupational therapist to work on emotional regulation by way of specific sensory tools can be helpful. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for kids ages 2 to 7 can also help build some relational activities and skills that can be utilized during trying situations to help keep a child settled and occupied.

If a child has qualified for Developmental Disability Services (DDS), medical providers can also write “prescriptions’ for sensory calming items which are often covered financially by DDS, such as chewies, weighted vests, stuffed animals, and fidgets. Encouraging parents to schedule allowed screen time at home in a very predictable and controlled manner is one method to help limit excessive use, as well as it’s utilization as an emotional regulation tool.

For public outings with children with special needs, and in particular in situations where meltdowns are likely to occur, some families find it helpful to dress their children in clothing or accessories that increase community awareness about their child’s condition (such as an autism awareness t-shirt). This effort can also help deflect unhelpful attention or advice from the public. Some parents choose to carry small cards explaining the child’s developmental differences, which can then be easily handed to unsupportive strangers in community settings during trying moments.

Clinicians can work to utilize even quick visits with families as an opportunity to review the American Academy of Pediatrics screen time recommendations with families, and also direct them to the Family Media Plan creation resources. Parenting in the modern era presents many challenges regarding choices around the use of electronic devices with children, and using the exam room experience as a teaching opportunity may be a helpful way to decrease utilization of screens as emotional regulation tools for children, while also providing general education around healthy use of screens.

Dr. Roth is a developmental and behavioral pediatrician in Eugene, Oregon.

Reference

1. Takahashi I et al. Screen Time at Age 1 Year and Communication and Problem-Solving Developmental Delays at 2 and 4 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Oct 1;177(10):1039-1046. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3057.

A 3-year-old presents to my clinic for evaluation of a possible autism spectrum disorder/difference. He has a history of severe emotional dysregulation, as well as reduced social skills and multiple sensory sensitivities. When I enter the exam room he is watching videos on his mom’s phone, and has some difficulty transitioning to play with toys when I encourage him to do so. He is eventually able to cooperate with my testing, though a bit reluctantly, and scores within the low average range for both language and pre-academic skills. His neurologic exam is within normal limits. He utilizes reasonably well-modulated eye contact paired with some typical use of gestures, and his affect is moderately directed and reactive. He displays typical intonation and prosody of speech, though engages in less spontaneous, imaginative, and reciprocal play than would be expected for his age. His mother reports decreased pretend play at home, minimal interest in toys, and difficulty playing cooperatively with other children.

Upon further history, it becomes apparent that the child spends a majority of his time on electronic devices, and has done so since early toddlerhood. Further dialogue suggests that the family became isolated during the COVID-19 pandemic, and has not yet re-engaged with the community in a meaningful way. The child has had rare opportunity for social interactions with other children, and minimal access to outdoor play. His most severe meltdowns generally involve transitions away from screens, and his overwhelmed parents often resort to use of additional screens to calm him once he is dysregulated.

At the end of the visit, through shared decision making, we agree that enrolling the child in a high-quality public preschool will help parents make a concerted effort towards a significant reduction in the hours per day in which the child utilizes electronic devices, while also providing him more exposure to peers. We plan for the child to return in 6 months for a re-evaluation around social-emotional skills, given his current limited exposure to peers and limited “unplugged” play-time.

Overutilization of Electronic Devices

As clinicians, we can all see how pervasive the use of electronic devices has become in the lives of the families we care for, as well as in our own lives, and how challenging some aspects of modern parenting have become. The developmental impact of early and excessive use of screens in young children is well documented,1 but as clinicians it can be tricky to help empower parents to find ways to limit screen time. When parents use screens to comfort and amuse their children during a clinic visit, this situation may serve as an excellent opportunity for a meaningful and respectful conversation around skill deficits which can result from overutilization of electronic devices in young children.

One scenario I often encounter during my patient evaluations as a developmental and behavioral pediatrician is children begging their parents for use of their phone throughout their visits with me. Not infrequently, a child is already on a screen when I enter the exam room, even when there has been a minimal wait time, which often leads to some resistance on behalf of the child as I explain to the family that a significant portion of the visit involves my interactions with the child, testing the child, and observing their child at play. I always provide ample amounts of age-appropriate art supplies, puzzles, fidgets, building toys, and imaginative play items to children during their 30 to 90 minute evaluations, but these are often not appealing to children when they have been very recently engaged with an electronic device. At times I also need to ask caretakers themselves to please disengage from their own electronic devices during the visit so that I can involve them in a detailed discussion about their child.

One challenge with the practice of allowing children access to entertainment on their parent’s smartphones in particular, lies in the fact that these devices are almost always present, meaning there is no natural boundary to inhibit access, in contrast to a television set or stationary computer parked in the family living room. Not dissimilar to candy visible in a parent’s purse, a cell phone becomes a constant temptation for children accustomed to utilizing them at home and public venues, and the incessant begging can wear down already stressed parents.

Children can become conditioned to utilize the distraction of screens to avoid feelings of discomfort or stress, and so can be very persistent and emotional when asking for the use of screens in public settings. Out in the community, I very frequently see young children and toddlers quietly staring at their phones and tablets while at restaurants and stores. While I have empathy for exhausted parents desperate for a moment of quiet, if this type of screen use is the rule rather than the exception for a child, there is risk for missed opportunities for the development of self-regulation skills.

Additionally, I have seen very young children present to my clinic with poor posture and neck pain secondary to chronic smartphone use, and young children who are getting minimal exercise or outdoor time due to excessive screen use, leading to concerns around fine and gross motor skills as well.

While allowing a child to stay occupied with or be soothed by a highly interesting digital experience can create a more calm environment for all, if habitual, this use can come at a cost regarding opportunities for the growth of executive functioning skills, general coping skills, general situational awareness, and experiential learning. Reliance on screens to decrease uncomfortable experiences decreases the opportunity for building distress tolerance, patience, and coping skills.

Of course there are times of extreme distress where a lollipop or bit of screen time might be reasonable to help keep a child safe or further avoid emotional trauma, but in general, other methods of soothing can very often be utilized, and in the long run would serve to increase the child’s general adaptive functioning.

A Teachable Moment

When clinicians encounter screens being used by parents to entertain their kids in clinic, it provides a valuable teaching moment around the risks of using screens to keep kids regulated and occupied during life’s less interesting or more anxiety provoking experiences. Having a meaningful conversation about the use of electronic devices with caregivers by clinicians in the exam room can be a delicate dance between providing supportive education while avoiding judgmental tones or verbiage. Normalizing and sympathizing with the difficulty of managing challenging behaviors from children in public spaces can help parents feel less desperate to keep their child quiet at all costs, and thus allow for greater development of coping skills.

Some parents may benefit from learning simple ideas for keeping a child regulated and occupied during times of waiting such as silly songs and dances, verbal games like “I spy,” and clapping routines. For a child with additional sensory or developmental needs, a referral to an occupational therapist to work on emotional regulation by way of specific sensory tools can be helpful. Parent-Child Interaction Therapy for kids ages 2 to 7 can also help build some relational activities and skills that can be utilized during trying situations to help keep a child settled and occupied.

If a child has qualified for Developmental Disability Services (DDS), medical providers can also write “prescriptions’ for sensory calming items which are often covered financially by DDS, such as chewies, weighted vests, stuffed animals, and fidgets. Encouraging parents to schedule allowed screen time at home in a very predictable and controlled manner is one method to help limit excessive use, as well as it’s utilization as an emotional regulation tool.

For public outings with children with special needs, and in particular in situations where meltdowns are likely to occur, some families find it helpful to dress their children in clothing or accessories that increase community awareness about their child’s condition (such as an autism awareness t-shirt). This effort can also help deflect unhelpful attention or advice from the public. Some parents choose to carry small cards explaining the child’s developmental differences, which can then be easily handed to unsupportive strangers in community settings during trying moments.

Clinicians can work to utilize even quick visits with families as an opportunity to review the American Academy of Pediatrics screen time recommendations with families, and also direct them to the Family Media Plan creation resources. Parenting in the modern era presents many challenges regarding choices around the use of electronic devices with children, and using the exam room experience as a teaching opportunity may be a helpful way to decrease utilization of screens as emotional regulation tools for children, while also providing general education around healthy use of screens.

Dr. Roth is a developmental and behavioral pediatrician in Eugene, Oregon.

Reference

1. Takahashi I et al. Screen Time at Age 1 Year and Communication and Problem-Solving Developmental Delays at 2 and 4 years. JAMA Pediatr. 2023 Oct 1;177(10):1039-1046. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2023.3057.

The New Cancer Stats Might Look Like a Death Sentence. They Aren’t.

Cancer is becoming more common in younger generations. Data show that people under 50 are experiencing higher rates of cancer than any generation before them. As a genetic counselor, I hoped these upward trends in early-onset malignancies would slow with a better understanding of risk factors and prevention strategies. Unfortunately, the opposite is happening. Recent findings from the American Cancer Society reveal that the incidence of at least 17 of 34 cancer types is rising among GenX and Millennials.

These statistics are alarming. I appreciate how easy it is for patients to get lost in the headlines about cancer, which may shape how they approach their healthcare. Each year, millions of Americans miss critical cancer screenings, with many citing fear of a positive test result as a leading reason. Others believe, despite the statistics, that cancer is not something they need to worry about until they are older. And then, of course, getting screened is not as easy as it should be.

In my work, I meet with people from both younger and older generations who have either faced cancer themselves or witnessed a loved one experience the disease. One of the most common sentiments I hear from these patients is the desire to catch cancer earlier. My answer is always this: The first and most important step everyone can take is understanding their risk.

For some, knowing they are at increased risk for cancer means starting screenings earlier — sometimes as early as age 25 — or getting screened with a more sensitive test.

This proactive approach is the right one. It also significantly reduces the burden of total and cancer-specific healthcare costs. While screening may carry some potential risks, clinicians can minimize these risks by adhering to evidence-based guidelines, such as those from the American Cancer Society, and ensuring there is appropriate discussion of treatment options when a diagnosis is made.

Normalizing Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening

A detailed cancer risk assessment and education about signs and symptoms should be part of every preventive care visit, regardless of someone’s age. Further, that cancer risk assessment should lead to clear recommendations and support for taking the next steps.

This is where care advocacy and patient navigation come in. Care advocacy can improve outcomes at every stage of the cancer journey, from increasing screening rates to improving quality of life for survivors. I’ve seen first-hand how care advocates help patients overcome hurdles like long wait times for appointments they need, making both screening and diagnostic care easier to access.

Now, with the finalization of a new rule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, providers can bill for oncology navigation services that occur under their supervision. This formal recognition of care navigation affirms the value of these services not just clinically but financially as well. It will be through methods like care navigation, targeted outreach, and engaging educational resources — built into and covered by health plans — that patients will feel more in control over their health and have tools to help minimize the effects of cancer on the rest of their lives.

These services benefit healthcare providers as well. Care navigation supports clinical care teams, from primary care providers to oncologists, by ensuring patients are seen before their cancer progresses to a more advanced stage. And even if patients follow screening recommendations for the rest of their lives and never get a positive result, they’ve still gained something invaluable: peace of mind, knowing they’ve taken an active role in their health.

Fighting Fear With Routine

Treating cancer as a normal part of young people’s healthcare means helping them envision the disease as a condition that can be treated, much like a diagnosis of diabetes or high cholesterol. This mindset shift means quickly following up on a concerning symptom or screening result and reducing the time to start treatment if needed. And with treatment options and success rates for some cancers being better than ever, survivorship support must be built into every treatment plan from the start. Before treatment begins, healthcare providers should make time to talk about sometimes-overlooked key topics, such as reproductive options for people whose fertility may be affected by their cancer treatment, about plans for returning to work during or after treatment, and finding the right mental health support.

Where we can’t prevent cancer, both primary care providers and oncologists can work together to help patients receive the right diagnosis and treatment as quickly as possible. Knowing insurance coverage has a direct effect on how early cancer is caught, for example, younger people need support in understanding and accessing benefits and resources that may be available through their existing healthcare channels, like some employer-sponsored health plans. Even if getting treated for cancer is inevitable for some, taking immediate action to get screened when it’s appropriate is the best thing we can do to lessen the impact of these rising cancer incidences across the country. At the end of the day, being afraid of cancer doesn’t decrease the chances of getting sick or dying from it. Proactive screening and early detection do.

Brockman, Genetic Counselor, Color Health, Buffalo, New York, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer is becoming more common in younger generations. Data show that people under 50 are experiencing higher rates of cancer than any generation before them. As a genetic counselor, I hoped these upward trends in early-onset malignancies would slow with a better understanding of risk factors and prevention strategies. Unfortunately, the opposite is happening. Recent findings from the American Cancer Society reveal that the incidence of at least 17 of 34 cancer types is rising among GenX and Millennials.

These statistics are alarming. I appreciate how easy it is for patients to get lost in the headlines about cancer, which may shape how they approach their healthcare. Each year, millions of Americans miss critical cancer screenings, with many citing fear of a positive test result as a leading reason. Others believe, despite the statistics, that cancer is not something they need to worry about until they are older. And then, of course, getting screened is not as easy as it should be.

In my work, I meet with people from both younger and older generations who have either faced cancer themselves or witnessed a loved one experience the disease. One of the most common sentiments I hear from these patients is the desire to catch cancer earlier. My answer is always this: The first and most important step everyone can take is understanding their risk.

For some, knowing they are at increased risk for cancer means starting screenings earlier — sometimes as early as age 25 — or getting screened with a more sensitive test.

This proactive approach is the right one. It also significantly reduces the burden of total and cancer-specific healthcare costs. While screening may carry some potential risks, clinicians can minimize these risks by adhering to evidence-based guidelines, such as those from the American Cancer Society, and ensuring there is appropriate discussion of treatment options when a diagnosis is made.

Normalizing Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening

A detailed cancer risk assessment and education about signs and symptoms should be part of every preventive care visit, regardless of someone’s age. Further, that cancer risk assessment should lead to clear recommendations and support for taking the next steps.

This is where care advocacy and patient navigation come in. Care advocacy can improve outcomes at every stage of the cancer journey, from increasing screening rates to improving quality of life for survivors. I’ve seen first-hand how care advocates help patients overcome hurdles like long wait times for appointments they need, making both screening and diagnostic care easier to access.

Now, with the finalization of a new rule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, providers can bill for oncology navigation services that occur under their supervision. This formal recognition of care navigation affirms the value of these services not just clinically but financially as well. It will be through methods like care navigation, targeted outreach, and engaging educational resources — built into and covered by health plans — that patients will feel more in control over their health and have tools to help minimize the effects of cancer on the rest of their lives.

These services benefit healthcare providers as well. Care navigation supports clinical care teams, from primary care providers to oncologists, by ensuring patients are seen before their cancer progresses to a more advanced stage. And even if patients follow screening recommendations for the rest of their lives and never get a positive result, they’ve still gained something invaluable: peace of mind, knowing they’ve taken an active role in their health.

Fighting Fear With Routine

Treating cancer as a normal part of young people’s healthcare means helping them envision the disease as a condition that can be treated, much like a diagnosis of diabetes or high cholesterol. This mindset shift means quickly following up on a concerning symptom or screening result and reducing the time to start treatment if needed. And with treatment options and success rates for some cancers being better than ever, survivorship support must be built into every treatment plan from the start. Before treatment begins, healthcare providers should make time to talk about sometimes-overlooked key topics, such as reproductive options for people whose fertility may be affected by their cancer treatment, about plans for returning to work during or after treatment, and finding the right mental health support.

Where we can’t prevent cancer, both primary care providers and oncologists can work together to help patients receive the right diagnosis and treatment as quickly as possible. Knowing insurance coverage has a direct effect on how early cancer is caught, for example, younger people need support in understanding and accessing benefits and resources that may be available through their existing healthcare channels, like some employer-sponsored health plans. Even if getting treated for cancer is inevitable for some, taking immediate action to get screened when it’s appropriate is the best thing we can do to lessen the impact of these rising cancer incidences across the country. At the end of the day, being afraid of cancer doesn’t decrease the chances of getting sick or dying from it. Proactive screening and early detection do.

Brockman, Genetic Counselor, Color Health, Buffalo, New York, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Cancer is becoming more common in younger generations. Data show that people under 50 are experiencing higher rates of cancer than any generation before them. As a genetic counselor, I hoped these upward trends in early-onset malignancies would slow with a better understanding of risk factors and prevention strategies. Unfortunately, the opposite is happening. Recent findings from the American Cancer Society reveal that the incidence of at least 17 of 34 cancer types is rising among GenX and Millennials.

These statistics are alarming. I appreciate how easy it is for patients to get lost in the headlines about cancer, which may shape how they approach their healthcare. Each year, millions of Americans miss critical cancer screenings, with many citing fear of a positive test result as a leading reason. Others believe, despite the statistics, that cancer is not something they need to worry about until they are older. And then, of course, getting screened is not as easy as it should be.

In my work, I meet with people from both younger and older generations who have either faced cancer themselves or witnessed a loved one experience the disease. One of the most common sentiments I hear from these patients is the desire to catch cancer earlier. My answer is always this: The first and most important step everyone can take is understanding their risk.

For some, knowing they are at increased risk for cancer means starting screenings earlier — sometimes as early as age 25 — or getting screened with a more sensitive test.

This proactive approach is the right one. It also significantly reduces the burden of total and cancer-specific healthcare costs. While screening may carry some potential risks, clinicians can minimize these risks by adhering to evidence-based guidelines, such as those from the American Cancer Society, and ensuring there is appropriate discussion of treatment options when a diagnosis is made.

Normalizing Cancer Risk Assessment and Screening

A detailed cancer risk assessment and education about signs and symptoms should be part of every preventive care visit, regardless of someone’s age. Further, that cancer risk assessment should lead to clear recommendations and support for taking the next steps.

This is where care advocacy and patient navigation come in. Care advocacy can improve outcomes at every stage of the cancer journey, from increasing screening rates to improving quality of life for survivors. I’ve seen first-hand how care advocates help patients overcome hurdles like long wait times for appointments they need, making both screening and diagnostic care easier to access.

Now, with the finalization of a new rule from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, providers can bill for oncology navigation services that occur under their supervision. This formal recognition of care navigation affirms the value of these services not just clinically but financially as well. It will be through methods like care navigation, targeted outreach, and engaging educational resources — built into and covered by health plans — that patients will feel more in control over their health and have tools to help minimize the effects of cancer on the rest of their lives.

These services benefit healthcare providers as well. Care navigation supports clinical care teams, from primary care providers to oncologists, by ensuring patients are seen before their cancer progresses to a more advanced stage. And even if patients follow screening recommendations for the rest of their lives and never get a positive result, they’ve still gained something invaluable: peace of mind, knowing they’ve taken an active role in their health.

Fighting Fear With Routine

Treating cancer as a normal part of young people’s healthcare means helping them envision the disease as a condition that can be treated, much like a diagnosis of diabetes or high cholesterol. This mindset shift means quickly following up on a concerning symptom or screening result and reducing the time to start treatment if needed. And with treatment options and success rates for some cancers being better than ever, survivorship support must be built into every treatment plan from the start. Before treatment begins, healthcare providers should make time to talk about sometimes-overlooked key topics, such as reproductive options for people whose fertility may be affected by their cancer treatment, about plans for returning to work during or after treatment, and finding the right mental health support.

Where we can’t prevent cancer, both primary care providers and oncologists can work together to help patients receive the right diagnosis and treatment as quickly as possible. Knowing insurance coverage has a direct effect on how early cancer is caught, for example, younger people need support in understanding and accessing benefits and resources that may be available through their existing healthcare channels, like some employer-sponsored health plans. Even if getting treated for cancer is inevitable for some, taking immediate action to get screened when it’s appropriate is the best thing we can do to lessen the impact of these rising cancer incidences across the country. At the end of the day, being afraid of cancer doesn’t decrease the chances of getting sick or dying from it. Proactive screening and early detection do.

Brockman, Genetic Counselor, Color Health, Buffalo, New York, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Heard of ApoB Testing? New Guidelines

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

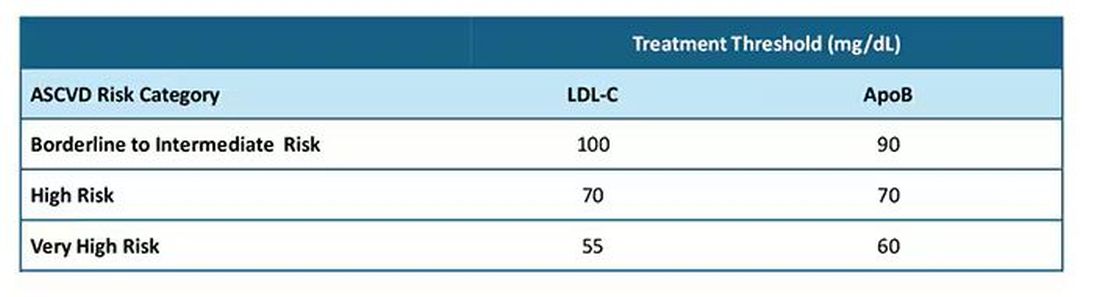

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

I've been hearing a lot about apolipoprotein B (apoB) lately. It keeps popping up, but I've not been sure where it fits in or what I should do about it. The new Expert Clinical Consensus from the National Lipid Association now finally gives us clear guidance.

ApoB is the main protein that is found on all atherogenic lipoproteins. It is found on low-density lipoprotein (LDL) but also on other atherogenic lipoprotein particles. Because it is a part of all atherogenic particles, it predicts cardiovascular (CV) risk more accurately than does LDL cholesterol (LDL-C).

ApoB and LDL-C tend to run together, but not always. While they are correlated fairly well on a population level, for a given individual they can diverge; and when they do, apoB is the better predictor of future CV outcomes. This divergence occurs frequently, and it can occur even more frequently after treatment with statins. When LDL decreases to reach the LDL threshold for treatment, but apoB remains elevated, there is the potential for misclassification of CV risk and essentially the risk for undertreatment of someone whose CV risk is actually higher than it appears to be if we only look at their LDL-C. The consensus statement says, "Where there is discordance between apoB and LDL-C, risk follows apoB."

This understanding leads to the places where measurement of apoB may be helpful:

In patients with borderline atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk in whom a shared decision about statin therapy is being determined and the patient prefers not to start a statin, apoB can be useful for further risk stratification. If apoB suggests low risk, then statin therapy could be withheld, and if apoB is high, that would favor starting statin therapy. Certain common conditions, such as obesity and insulin resistance, can lead to smaller cholesterol-depleted LDL particles that result in lower LDL-C, but elevated apoB levels in this circumstance may drive the decision to treat with a statin.

In patients already treated with statins, but a decision must be made about whether treatment intensification is warranted. If the LDL-C is to goal and apoB is above threshold, treatment intensification may be considered. In patients who are not yet to goal, based on an elevated apoB, the first step is intensification of statin therapy. After that, intensification would be the same as has already been addressed in my review of the 2022 ACC Expert Consensus Decision Pathway on the Role of Nonstatin Therapies for LDL-Cholesterol Lowering.

After clarifying the importance of apoB in providing additional discrimination of CV risk, the consensus statement clarifies the treatment thresholds, or goals for treatment, for apoB that correlate with established LDL-C thresholds, as shown in this table:

Let me be really clear: The consensus statement does not say that we need to measure apoB in all patients or that such measurement is the standard of care. It is not. It says, and I'll quote, "At present, the use of apoB to assess the effectiveness of lipid-lowering therapies remains a matter of clinical judgment." This guideline is helpful in pointing out the patients most likely to benefit from this additional measurement, including those with hypertriglyceridemia, diabetes, visceral adiposity, insulin resistance/metabolic syndrome, low HDL-C, or very low LDL-C levels.

In summary, measurement of apoB can be helpful for further risk stratification in patients with borderline or intermediate LDL-C levels, and for deciding whether further intensification of lipid-lowering therapy may be warranted when the LDL threshold has been reached.

Lipid management is something that we do every day in the office. This is new information, or at least clarifying information, for most of us. Hopefully it is helpful. I'm interested in your thoughts on this topic, including whether and how you plan to use apoB measurements.

Dr. Skolnik, Professor, Department of Family Medicine, Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia; Associate Director, Department of Family Medicine, Abington Jefferson Health, Abington, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with AstraZeneca, Teva, Eli Lilly, Boehringer Ingelheim, Sanofi, Sanofi Pasteur, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and Bayer.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mechanism of Action

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

MOA — Mechanism of action — gets bandied about a lot.

Drug reps love it. Saying your product is a “first-in-class MOA” sounds great as they hand you a glossy brochure. It also features prominently in print ads, usually with pics of smiling people.

It’s a good thing to know, too, both medically and in a cool-science-geeky way. We want to understand what we’re prescribing will do to patients. We want to explain it to them, too.

It certainly helps to know that what we’re doing when treating a disorder using rational polypharmacy.

But at the same time we face the realization that it may not mean as much as we think it should. I don’t have to go back very far in my career to find Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that worked, but we didn’t have a clear reason why. I mean, we had a vague idea on a scientific basis, but we’re still guessing.

This didn’t stop us from using them, which is nothing new. The ancients had learned certain plants reduced pain and fever long before they understood what aspirin (and its MOA) was.

At the same time we’re now using drugs, such as the anti-amyloid treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, that should be more effective than one would think. Pulling the damaged molecules out of the brain should, on paper, make a dramatic difference ... but it doesn’t. I’m not saying they don’t have some benefit, but certainly not as much as you’d think. Of course, that’s based on our understanding of the disease mechanism being correct. We find there’s a lot more going on than we know.

Like so much in science (and this aspect of medicine is a science) the answers often lead to more questions.

Observation takes the lead over understanding in most things. Our ancestors knew what fire was, and how to use it, without any idea of what rapid exothermic oxidation was. (Admittedly, I have a degree in chemistry and can’t explain it myself anymore.)

The glossy ads and scientific data about MOA doesn’t mean much in my world if they don’t work. My patients would say the same.

Clinical medicine, after all, is both an art and a science.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Arizona.

What Should You Do When a Patient Asks for a PSA Test?

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Many patients ask us to request a prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. According to the Brazilian Ministry of Health, prostate cancer is the second most common type of cancer in the male population in all regions of our country. It is the second-leading cause of cancer death in the male population, reaffirming its epidemiologic importance in Brazil. On the other hand, a Ministry of Health technical paper recommends against population-based screening for prostate cancer. So, what should we do?

First, it is important to distinguish early diagnosis from screening. Early diagnosis is the identification of cancer in early stages in people with signs and symptoms. Screening is characterized by the systematic application of exams — digital rectal exam and PSA test — in asymptomatic people, with the aim of identifying cancer in an early stage.

A recent European epidemiologic study reinforced this thesis and helps guide us.

The study included men aged 35-84 years from 26 European countries. Data on cancer incidence and mortality were collected between 1980 and 2017. The data suggested overdiagnosis of prostate cancer, which varied over time and among populations. The findings supported previous recommendations that any implementation of prostate cancer screening should be carefully designed, with an emphasis on minimizing the harms of overdiagnosis.

The clinical evolution of prostate cancer is still not well understood. Increasing age is associated with increased mortality. Many men with less aggressive disease tend to die with cancer rather than die of cancer. However, it is not always possible at the time of diagnosis to determine which tumors will be aggressive and which will grow slowly.

On the other hand, with screening, many of these indolent cancers are unnecessarily detected, generating excessive exams and treatments with negative repercussions (eg, pain, bleeding, infections, stress, and urinary and sexual dysfunction).

So, how should we as clinicians proceed regarding screening?

We should request the PSA test and emphasize the importance of digital rectal exam by a urologist for those at high risk for prostatic neoplasia (ie, those with family history) or those with urinary symptoms that may be associated with prostate cancer.

In general, we should draw attention to the possible risks and benefits of testing and adopt a shared decision-making approach with asymptomatic men or those at low risk who wish to have the screening exam. But achieving a shared decision is not a simple task.

I always have a thorough conversation with patients, but I confess that I request the exam in most cases.

Dr. Wajngarten is a professor of cardiology, Faculty of Medicine, at the University of São Paulo in Brazil. Dr. Wajngarten reported no conflicts of interest.

This story was translated from the Medscape Portuguese edition using several editorial tools, including AI, as part of the process. Human editors reviewed this content before publication. A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Maternal Immunization to Prevent Serious Respiratory Illness

Editor’s Note: Sadly, this is the last column in the Master Class Obstetrics series. This award-winning column has been part of Ob.Gyn. News for 20 years. The deep discussion of cutting-edge topics in obstetrics by specialists and researchers will be missed as will the leadership and curation of topics by Dr. E. Albert Reece.

Introduction: The Need for Increased Vigilance About Maternal Immunization

Viruses are becoming increasingly prevalent in our world and the consequences of viral infections are implicated in a growing number of disease states. It is well established that certain cancers are caused by viruses and it is increasingly evident that viral infections can trigger the development of chronic illness. In pregnant women, viruses such as cytomegalovirus can cause infection in utero and lead to long-term impairments for the baby.

Likewise, it appears that the virulence of viruses is increasing, whether it be the respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) in children or the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronaviruses in adults. Clearly, our environment is changing, with increases in population growth and urbanization, for instance, and an intensification of climate change and its effects. Viruses are part of this changing background.

Vaccines are our most powerful tool to protect people of all ages against viral threats, and fortunately, we benefit from increasing expertise in vaccinology. Since 1974, the University of Maryland School of Medicine has a Center for Vaccine Development and Global Health that has conducted research on vaccines to defend against the Zika virus, H1N1, Ebola, and SARS-CoV-2.

We’re not alone. Other vaccinology centers across the country — as well as the National Institutes of Health at the national level, through its National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases — are doing research and developing vaccines to combat viral diseases.

In this column, we are focused on viral diseases in pregnancy and the role that vaccines can play in preventing serious respiratory illness in mothers and their newborns. I have invited Laura E. Riley, MD, the Given Foundation Professor and Chair of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Weill Cornell Medicine, to address the importance of maternal immunization and how we can best counsel our patients and improve immunization rates.

As Dr. Riley explains, we are in a new era, and it behooves us all to be more vigilant about recommending vaccines, combating misperceptions, addressing patients’ knowledge gaps, and administering vaccines whenever possible.

Dr. Reece is the former Dean of Medicine & University Executive VP, and The Distinguished University and Endowed Professor & Director of the Center for Advanced Research Training and Innovation (CARTI) at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, as well as senior scientist at the Center for Birth Defects Research.

The alarming decline in maternal immunization rates that occurred in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic means that, now more than ever, we must fully embrace our responsibility to recommend immunizations in pregnancy and to communicate what is known about their efficacy and safety. Data show that vaccination rates drop when we do not offer vaccines in our offices, so whenever possible, we should administer them as well.

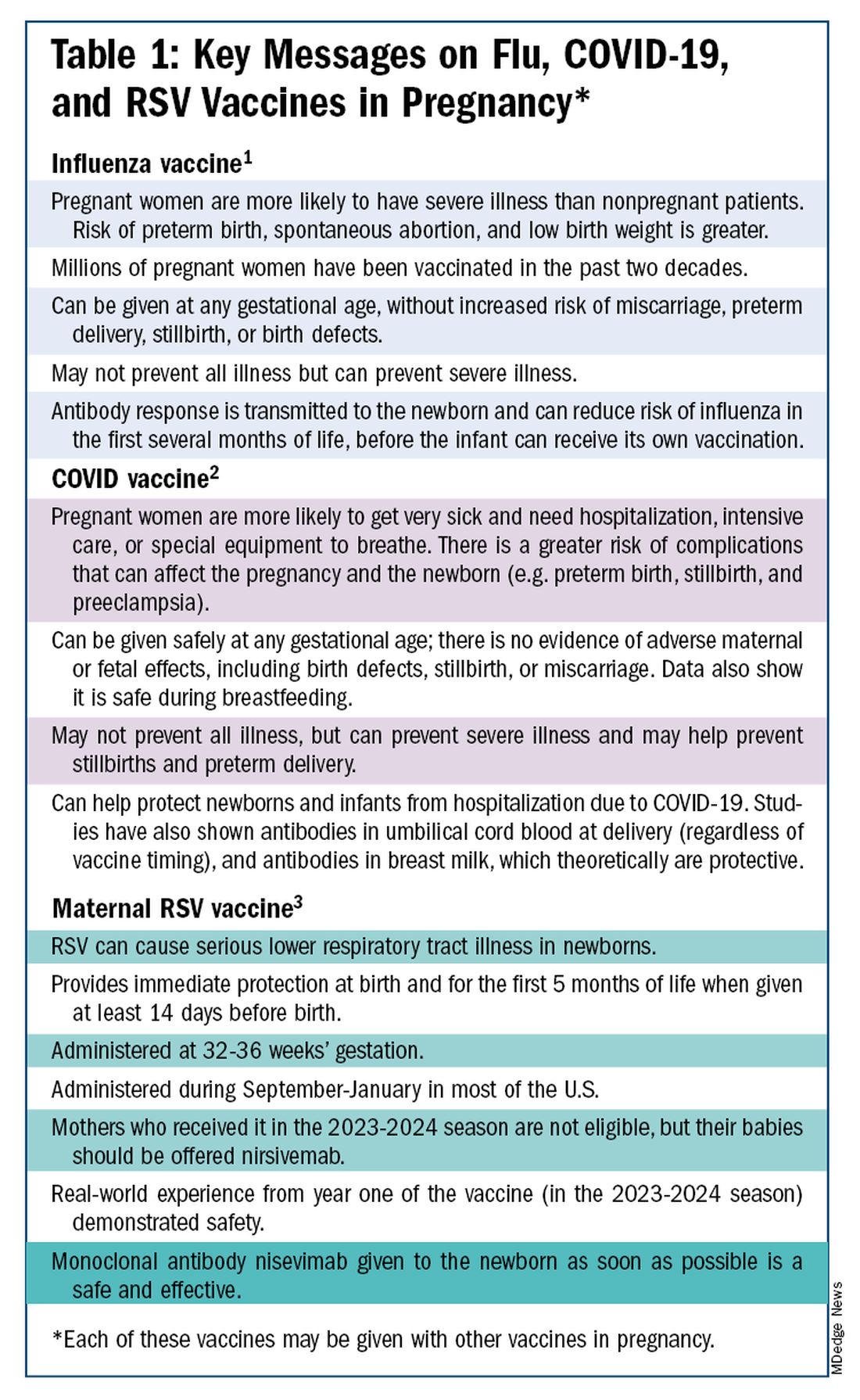

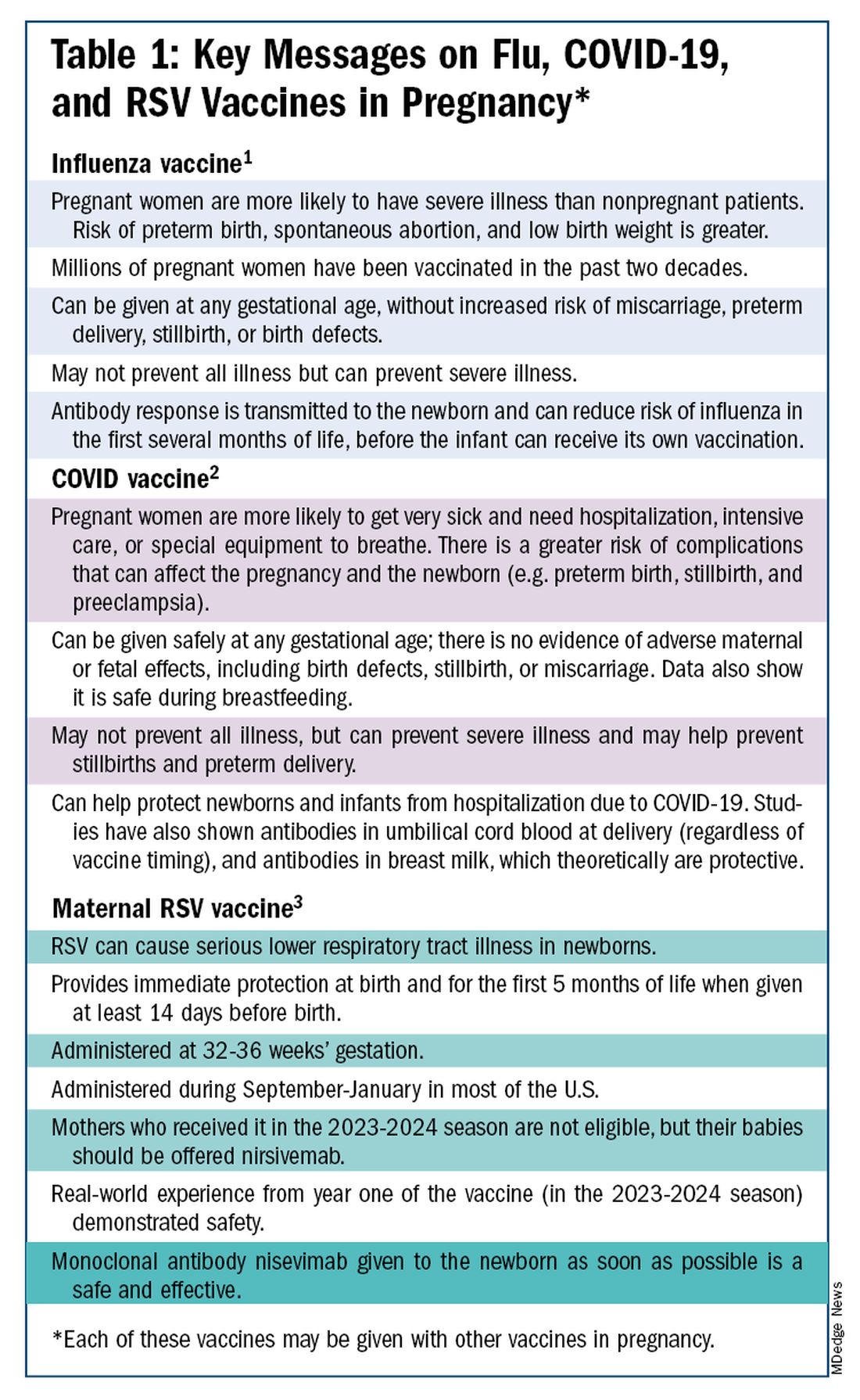

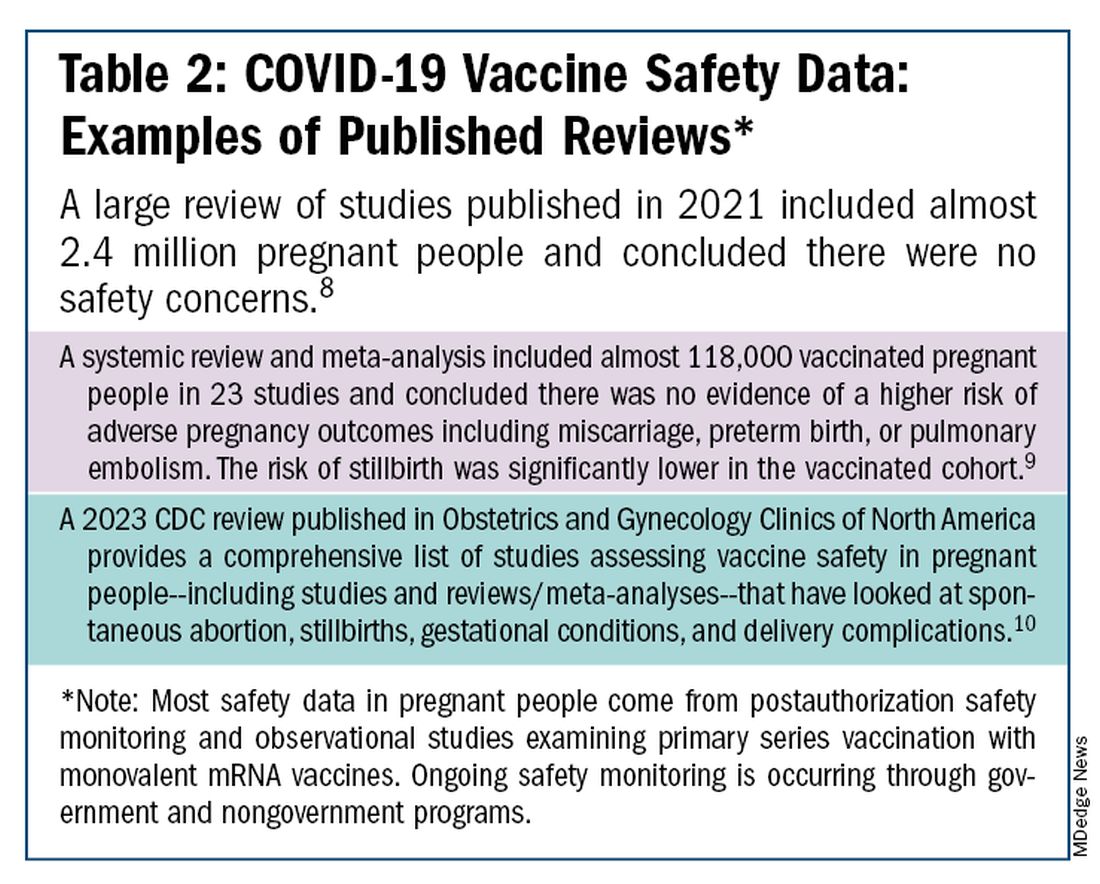

The ob.gyn. is the patient’s most trusted person in pregnancy. When patients decline or express hesitancy about vaccines, it is incumbent upon us to ask why. Oftentimes, we can identify areas in which patients lack knowledge or have misperceptions and we can successfully educate the patient or change their perspective or misunderstanding concerning the importance of vaccination for themselves and their babies. (See Table 1.) We can also successfully address concerns about safety.

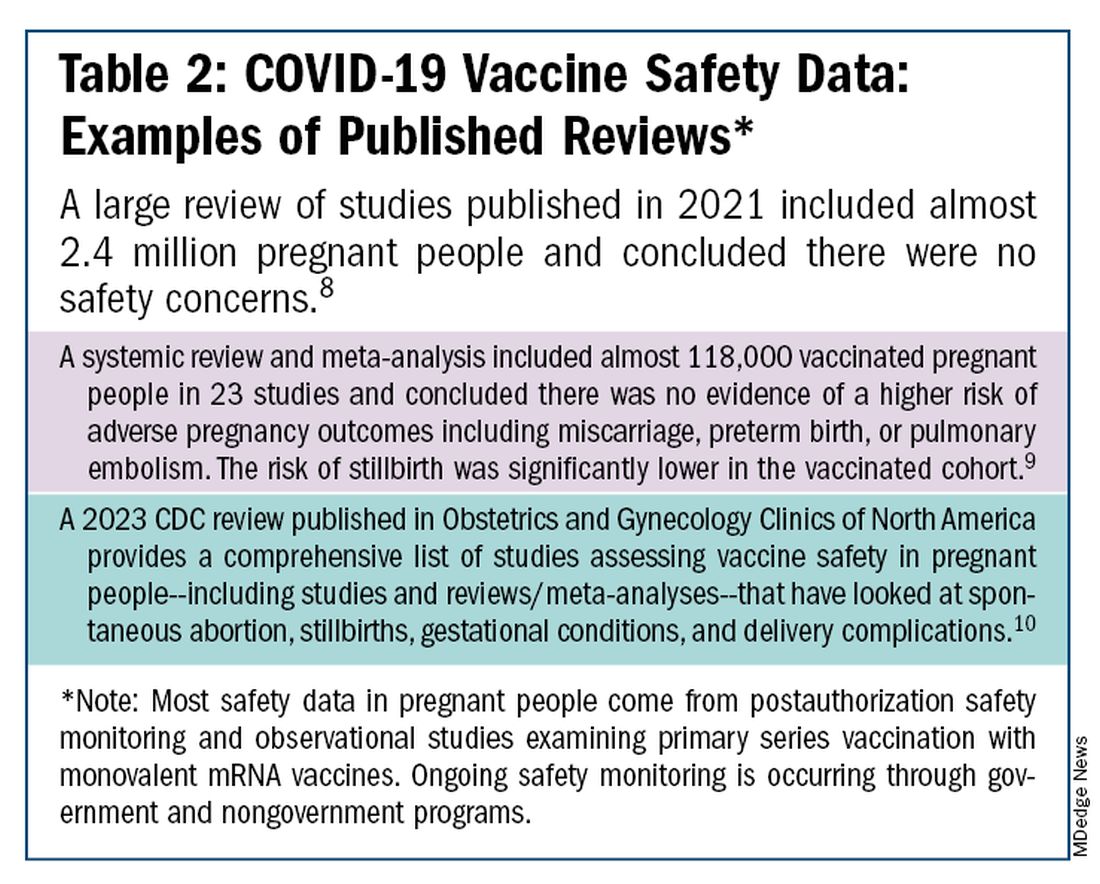

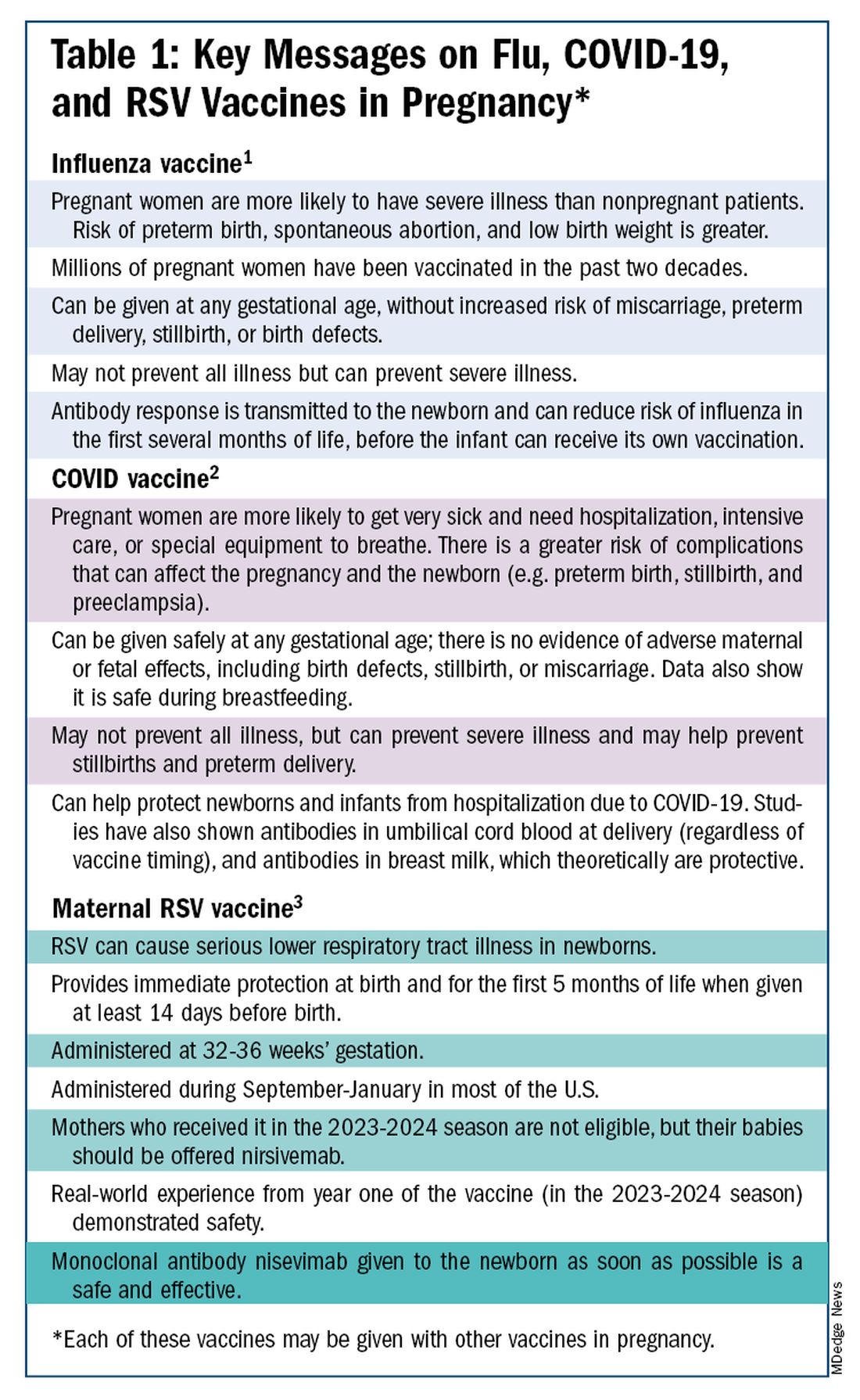

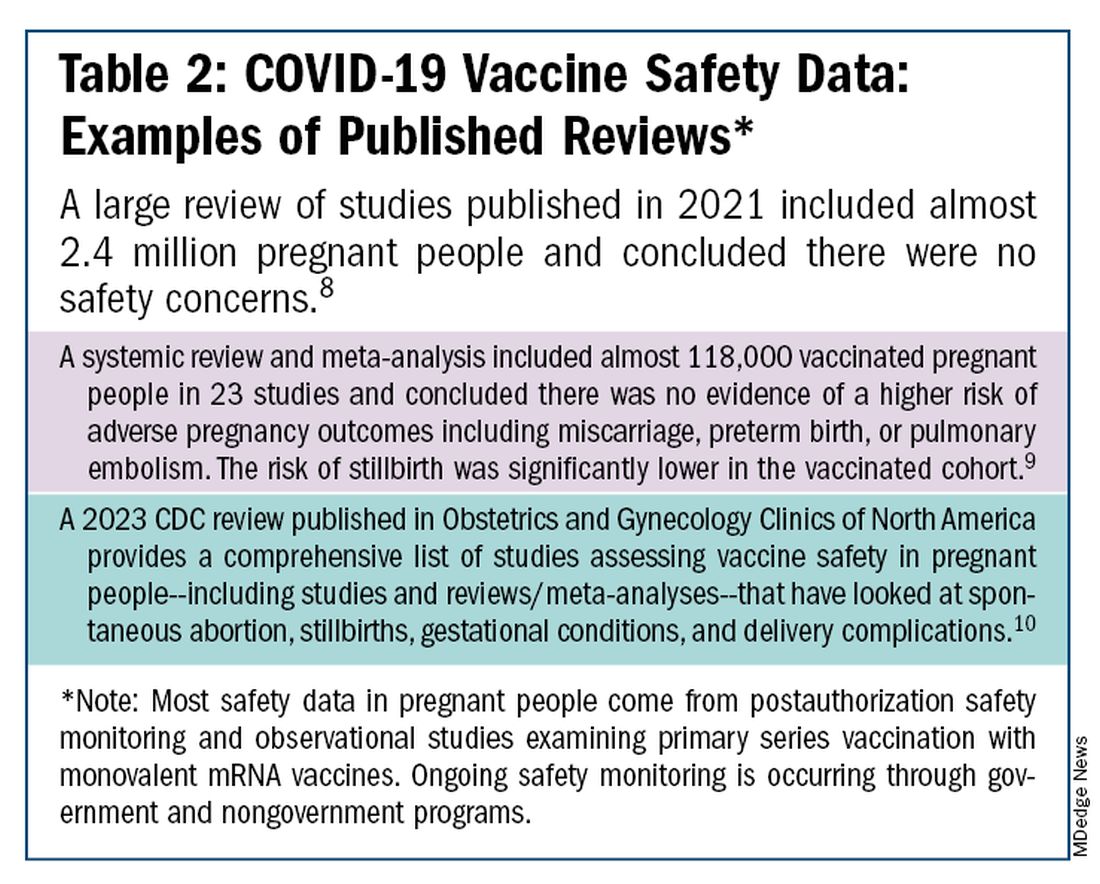

The safety of COVID-19 vaccinations in pregnancy is now backed by several years of data from multiple studies showing no increase in birth defects, preterm delivery, miscarriage, or stillbirth.

Data also show that pregnant patients are more likely than patients who are not pregnant to need hospitalization and intensive care when infected with SARS-CoV-2 and are at risk of having complications that can affect pregnancy and the newborn, including preterm birth and stillbirth. Vaccination has been shown to reduce the risk of severe illness and the risk of such adverse obstetrical outcomes, in addition to providing protection for the infant early on.

Similarly, influenza has long been more likely to be severe in pregnant patients, with an increased risk of poor obstetrical outcomes. Vaccines similarly provide “two for one protection,” protecting both mother and baby, and are, of course, backed by many years of safety and efficacy data.