User login

Itch response faster with abrocitinib in trial comparing JAK inhibitor to dupilumab

, in a multicenter, randomized trial.

In addition, in the study, those on 200-mg and 100-mg daily doses of abrocitinib experienced significantly greater reductions in signs and symptoms of AD at 12 and 16 weeks, than those on placebo, the authors reported.

The findings from the JADE COMPARE trial, published on March 25 in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggest abrocitinib will provide clinicians with another treatment option for patients who don’t get adequate relief from either topical medications or dupilumab. Abrocitinib is associated with a different set of adverse reactions than dupilumab, according to investigators.

In 2017, dupilumab (Dupixent) became the first systemic drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for AD, though systemic steroids and other immunosuppressant drugs are sometimes prescribed. A monoclonal antibody delivered by subcutaneous injection, dupilumab binds to interleukin-4 receptors to block signaling pathways involved in AD; it is now approved for treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD down to age 6 years.

“It is sort of the bar for efficacy and for safety in those patients, because that’s what we have right now,” said one of the JADE Compare investigators and study author, Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology and director of clinical research and contact dermatitis at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. “For any new therapy coming to market, we really do want to understand how it compares to what’s out there.”

Abrocitinib is a small molecule that inhibits JAK1, which is thought to modulate multiple cytokines involved in AD, including interleukin (IL)–4, IL-13, IL-31, IL-22, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Two other JAK1 inhibitors, baricitinib and upadacitinib, are also being investigated as systemic treatments for AD.

In JADE COMPARE, people with moderate to severe AD from 18 countries on four continents, entered a 28-day screening period during which they discontinued treatments. They began using emollients twice a day at least 7 days before being randomly assigned to a treatment group, and continued on topical medication once daily. Topical treatments included low- or medium-potency topical glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors.

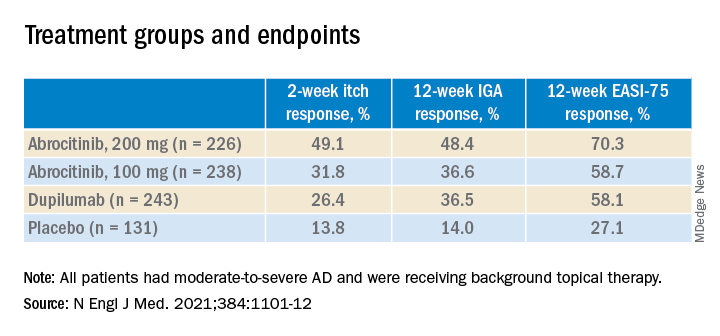

The researchers randomly assigned 838 to trial groups: 226 received 200 mg of abrocitinib orally once a day, 238 received 100 mg of abrocitinib once a day, 243 received a 300-mg dupilumab injection every other week, and 131 received placebo versions of both medications, for 16 weeks. The mean age of the patients overall was about 38 years; about two-thirds were White.

At 2 weeks, half of the patients on 200 mg of abrocitinib and 31.8% of those on the 100-mg dose had an itch response, defined as at least a 4-point improvement from baseline in the 0-10 Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale. This was compared with 26.4% of those on dupilumab and 13.8% of those on placebo.

And at 12 weeks, more of the patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group than in the other groups had an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) response (defined as clear or almost clear) and more had an Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) response (defined as an improvement of at least 75%). (See Table) EASI-75 and IGA responses at week 12 were the primary outcomes of the study.

The differences between both abrocitinib groups and the placebo group were statistically significant by all these measures (P < .001). The difference between the 200-mg abrocitinib and the dupilumab group was only significant for itch at 2 weeks, and the difference in itch response between the 100-mg group and the dupilumab group at 2 weeks was not significant (P < .20).

At 16 weeks, the EASI-75 response (a secondary endpoint) among those on either dose of abrocitinib was not significantly different than among those on dupilumab (71% and 60.3% among those on 200 mg and 100 mg, respectively; and 65.5% among those on dupilumab, compared with 30.6% of those on placebo).

“The patients I have on this medicine [abrocitinib] are very happy,” said one of the study authors, Melinda Gooderham, MsC, MD, an assistant professor at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., an investigator in the trial. “It works very quickly for itch,” she said in an interview.

The study didn’t have sufficient statistical power to fully explore the comparison to dupilumab, and future trials will go deeper into the comparison, she added.

Still, in this trial, abrocitinib demonstrated a clear advantage in the speed and depth of efficacy, Dr. Silverberg noted. “The 100-mg dose of abrocitinib was about as effective as, or maybe slightly less effective than, dupilumab, and the 200-mg dose was more effective than dupilumab.”

The overall incidence of adverse events was higher in the 200-mg abrocitinib arm than in the other groups, but the incidence of serious or severe adverse events, and the incidence of adverse events that resulted in discontinuing the medication, were similar across the trial groups.

However, nausea affected 11.1% of the patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group and 4.2% of those in the 100-mg abrocitinib group. Acne was also reported in these groups (6.6% and 2.9%, among those on 200 mg and 100 mg, respectively, compared with 1.2% of those on dupilumab and none of those on placebo). In a few of those on abrocitinib, herpes zoster flared up. And median platelet counts decreased among the patients taking abrocitinib, although none dropped below 75,000/mm3. Serious infections were reported in two patients on abrocitinib, but resolved.

By contrast, only 2.9% of the patients on dupilumab had nausea. But 6.2% in the dupilumab group had conjunctivitis, compared with 1.3% of patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group and 0.8 in the 100-mg abrocitinib group.

As an oral medication, abrocitinib will appeal to patients who want to avoid injections, and dosing will be easier to adjust, Dr. Silverberg said. On the other hand, he added, dupilumab will have an advantage for patients who don’t want to take a daily medication, or who are concerned about the adverse events associated with abrocitinib, particularly those with blood-clotting disorders.

On the basis of two previous JADE phase 3 trials, Pfizer has submitted a new drug application for abrocitinib for treating moderate to severe AD in patients aged 12 and older to the FDA; a decision is expected in April, according to the company. The company has also applied to market the drug in Europe and the United Kingdom.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Silverberg’s disclosures included serving as a consultant to companies including AbbVie, Pfizer, and Regeneron. Several authors are Pfizer employees; other authors had disclosures related to Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies.

, in a multicenter, randomized trial.

In addition, in the study, those on 200-mg and 100-mg daily doses of abrocitinib experienced significantly greater reductions in signs and symptoms of AD at 12 and 16 weeks, than those on placebo, the authors reported.

The findings from the JADE COMPARE trial, published on March 25 in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggest abrocitinib will provide clinicians with another treatment option for patients who don’t get adequate relief from either topical medications or dupilumab. Abrocitinib is associated with a different set of adverse reactions than dupilumab, according to investigators.

In 2017, dupilumab (Dupixent) became the first systemic drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for AD, though systemic steroids and other immunosuppressant drugs are sometimes prescribed. A monoclonal antibody delivered by subcutaneous injection, dupilumab binds to interleukin-4 receptors to block signaling pathways involved in AD; it is now approved for treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD down to age 6 years.

“It is sort of the bar for efficacy and for safety in those patients, because that’s what we have right now,” said one of the JADE Compare investigators and study author, Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology and director of clinical research and contact dermatitis at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. “For any new therapy coming to market, we really do want to understand how it compares to what’s out there.”

Abrocitinib is a small molecule that inhibits JAK1, which is thought to modulate multiple cytokines involved in AD, including interleukin (IL)–4, IL-13, IL-31, IL-22, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Two other JAK1 inhibitors, baricitinib and upadacitinib, are also being investigated as systemic treatments for AD.

In JADE COMPARE, people with moderate to severe AD from 18 countries on four continents, entered a 28-day screening period during which they discontinued treatments. They began using emollients twice a day at least 7 days before being randomly assigned to a treatment group, and continued on topical medication once daily. Topical treatments included low- or medium-potency topical glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors.

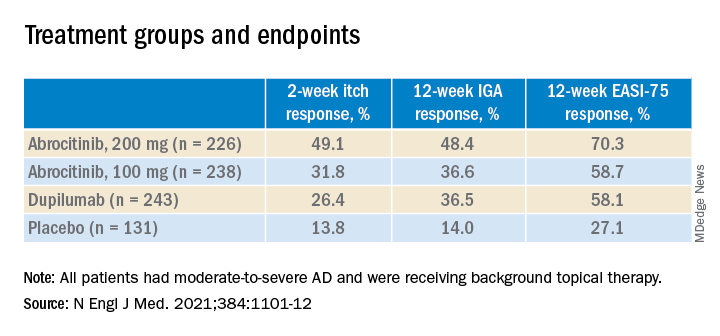

The researchers randomly assigned 838 to trial groups: 226 received 200 mg of abrocitinib orally once a day, 238 received 100 mg of abrocitinib once a day, 243 received a 300-mg dupilumab injection every other week, and 131 received placebo versions of both medications, for 16 weeks. The mean age of the patients overall was about 38 years; about two-thirds were White.

At 2 weeks, half of the patients on 200 mg of abrocitinib and 31.8% of those on the 100-mg dose had an itch response, defined as at least a 4-point improvement from baseline in the 0-10 Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale. This was compared with 26.4% of those on dupilumab and 13.8% of those on placebo.

And at 12 weeks, more of the patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group than in the other groups had an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) response (defined as clear or almost clear) and more had an Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) response (defined as an improvement of at least 75%). (See Table) EASI-75 and IGA responses at week 12 were the primary outcomes of the study.

The differences between both abrocitinib groups and the placebo group were statistically significant by all these measures (P < .001). The difference between the 200-mg abrocitinib and the dupilumab group was only significant for itch at 2 weeks, and the difference in itch response between the 100-mg group and the dupilumab group at 2 weeks was not significant (P < .20).

At 16 weeks, the EASI-75 response (a secondary endpoint) among those on either dose of abrocitinib was not significantly different than among those on dupilumab (71% and 60.3% among those on 200 mg and 100 mg, respectively; and 65.5% among those on dupilumab, compared with 30.6% of those on placebo).

“The patients I have on this medicine [abrocitinib] are very happy,” said one of the study authors, Melinda Gooderham, MsC, MD, an assistant professor at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., an investigator in the trial. “It works very quickly for itch,” she said in an interview.

The study didn’t have sufficient statistical power to fully explore the comparison to dupilumab, and future trials will go deeper into the comparison, she added.

Still, in this trial, abrocitinib demonstrated a clear advantage in the speed and depth of efficacy, Dr. Silverberg noted. “The 100-mg dose of abrocitinib was about as effective as, or maybe slightly less effective than, dupilumab, and the 200-mg dose was more effective than dupilumab.”

The overall incidence of adverse events was higher in the 200-mg abrocitinib arm than in the other groups, but the incidence of serious or severe adverse events, and the incidence of adverse events that resulted in discontinuing the medication, were similar across the trial groups.

However, nausea affected 11.1% of the patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group and 4.2% of those in the 100-mg abrocitinib group. Acne was also reported in these groups (6.6% and 2.9%, among those on 200 mg and 100 mg, respectively, compared with 1.2% of those on dupilumab and none of those on placebo). In a few of those on abrocitinib, herpes zoster flared up. And median platelet counts decreased among the patients taking abrocitinib, although none dropped below 75,000/mm3. Serious infections were reported in two patients on abrocitinib, but resolved.

By contrast, only 2.9% of the patients on dupilumab had nausea. But 6.2% in the dupilumab group had conjunctivitis, compared with 1.3% of patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group and 0.8 in the 100-mg abrocitinib group.

As an oral medication, abrocitinib will appeal to patients who want to avoid injections, and dosing will be easier to adjust, Dr. Silverberg said. On the other hand, he added, dupilumab will have an advantage for patients who don’t want to take a daily medication, or who are concerned about the adverse events associated with abrocitinib, particularly those with blood-clotting disorders.

On the basis of two previous JADE phase 3 trials, Pfizer has submitted a new drug application for abrocitinib for treating moderate to severe AD in patients aged 12 and older to the FDA; a decision is expected in April, according to the company. The company has also applied to market the drug in Europe and the United Kingdom.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Silverberg’s disclosures included serving as a consultant to companies including AbbVie, Pfizer, and Regeneron. Several authors are Pfizer employees; other authors had disclosures related to Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies.

, in a multicenter, randomized trial.

In addition, in the study, those on 200-mg and 100-mg daily doses of abrocitinib experienced significantly greater reductions in signs and symptoms of AD at 12 and 16 weeks, than those on placebo, the authors reported.

The findings from the JADE COMPARE trial, published on March 25 in the New England Journal of Medicine, suggest abrocitinib will provide clinicians with another treatment option for patients who don’t get adequate relief from either topical medications or dupilumab. Abrocitinib is associated with a different set of adverse reactions than dupilumab, according to investigators.

In 2017, dupilumab (Dupixent) became the first systemic drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration specifically for AD, though systemic steroids and other immunosuppressant drugs are sometimes prescribed. A monoclonal antibody delivered by subcutaneous injection, dupilumab binds to interleukin-4 receptors to block signaling pathways involved in AD; it is now approved for treatment of patients with moderate to severe AD down to age 6 years.

“It is sort of the bar for efficacy and for safety in those patients, because that’s what we have right now,” said one of the JADE Compare investigators and study author, Jonathan I. Silverberg, MD, PhD, MPH, associate professor of dermatology and director of clinical research and contact dermatitis at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview. “For any new therapy coming to market, we really do want to understand how it compares to what’s out there.”

Abrocitinib is a small molecule that inhibits JAK1, which is thought to modulate multiple cytokines involved in AD, including interleukin (IL)–4, IL-13, IL-31, IL-22, and thymic stromal lymphopoietin. Two other JAK1 inhibitors, baricitinib and upadacitinib, are also being investigated as systemic treatments for AD.

In JADE COMPARE, people with moderate to severe AD from 18 countries on four continents, entered a 28-day screening period during which they discontinued treatments. They began using emollients twice a day at least 7 days before being randomly assigned to a treatment group, and continued on topical medication once daily. Topical treatments included low- or medium-potency topical glucocorticoids, calcineurin inhibitors, and phosphodiesterase-4 inhibitors.

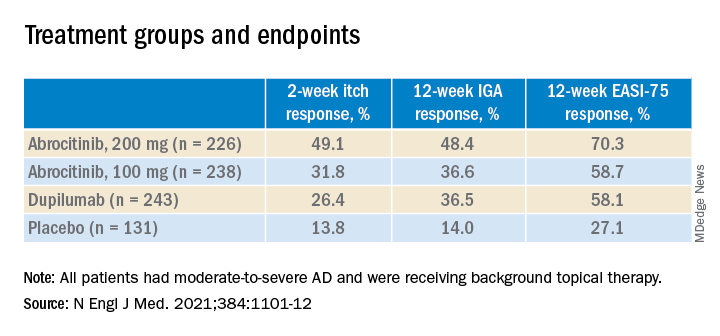

The researchers randomly assigned 838 to trial groups: 226 received 200 mg of abrocitinib orally once a day, 238 received 100 mg of abrocitinib once a day, 243 received a 300-mg dupilumab injection every other week, and 131 received placebo versions of both medications, for 16 weeks. The mean age of the patients overall was about 38 years; about two-thirds were White.

At 2 weeks, half of the patients on 200 mg of abrocitinib and 31.8% of those on the 100-mg dose had an itch response, defined as at least a 4-point improvement from baseline in the 0-10 Peak Pruritus Numerical Rating Scale. This was compared with 26.4% of those on dupilumab and 13.8% of those on placebo.

And at 12 weeks, more of the patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group than in the other groups had an Investigator’s Global Assessment (IGA) response (defined as clear or almost clear) and more had an Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI-75) response (defined as an improvement of at least 75%). (See Table) EASI-75 and IGA responses at week 12 were the primary outcomes of the study.

The differences between both abrocitinib groups and the placebo group were statistically significant by all these measures (P < .001). The difference between the 200-mg abrocitinib and the dupilumab group was only significant for itch at 2 weeks, and the difference in itch response between the 100-mg group and the dupilumab group at 2 weeks was not significant (P < .20).

At 16 weeks, the EASI-75 response (a secondary endpoint) among those on either dose of abrocitinib was not significantly different than among those on dupilumab (71% and 60.3% among those on 200 mg and 100 mg, respectively; and 65.5% among those on dupilumab, compared with 30.6% of those on placebo).

“The patients I have on this medicine [abrocitinib] are very happy,” said one of the study authors, Melinda Gooderham, MsC, MD, an assistant professor at Queen’s University, Kingston, Ont., an investigator in the trial. “It works very quickly for itch,” she said in an interview.

The study didn’t have sufficient statistical power to fully explore the comparison to dupilumab, and future trials will go deeper into the comparison, she added.

Still, in this trial, abrocitinib demonstrated a clear advantage in the speed and depth of efficacy, Dr. Silverberg noted. “The 100-mg dose of abrocitinib was about as effective as, or maybe slightly less effective than, dupilumab, and the 200-mg dose was more effective than dupilumab.”

The overall incidence of adverse events was higher in the 200-mg abrocitinib arm than in the other groups, but the incidence of serious or severe adverse events, and the incidence of adverse events that resulted in discontinuing the medication, were similar across the trial groups.

However, nausea affected 11.1% of the patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group and 4.2% of those in the 100-mg abrocitinib group. Acne was also reported in these groups (6.6% and 2.9%, among those on 200 mg and 100 mg, respectively, compared with 1.2% of those on dupilumab and none of those on placebo). In a few of those on abrocitinib, herpes zoster flared up. And median platelet counts decreased among the patients taking abrocitinib, although none dropped below 75,000/mm3. Serious infections were reported in two patients on abrocitinib, but resolved.

By contrast, only 2.9% of the patients on dupilumab had nausea. But 6.2% in the dupilumab group had conjunctivitis, compared with 1.3% of patients in the 200-mg abrocitinib group and 0.8 in the 100-mg abrocitinib group.

As an oral medication, abrocitinib will appeal to patients who want to avoid injections, and dosing will be easier to adjust, Dr. Silverberg said. On the other hand, he added, dupilumab will have an advantage for patients who don’t want to take a daily medication, or who are concerned about the adverse events associated with abrocitinib, particularly those with blood-clotting disorders.

On the basis of two previous JADE phase 3 trials, Pfizer has submitted a new drug application for abrocitinib for treating moderate to severe AD in patients aged 12 and older to the FDA; a decision is expected in April, according to the company. The company has also applied to market the drug in Europe and the United Kingdom.

The study was funded by Pfizer. Dr. Silverberg’s disclosures included serving as a consultant to companies including AbbVie, Pfizer, and Regeneron. Several authors are Pfizer employees; other authors had disclosures related to Pfizer and other pharmaceutical companies.

‘Reassuring’ data on COVID-19 vaccines in pregnancy

Pregnant women can safely get vaccinated with the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines for COVID-19, surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest.

More than 30,000 women who received these vaccines have reported pregnancies through the CDC’s V-Safe voluntary reporting system, and their rates of complications are not significantly different from those of unvaccinated pregnant women, said Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA, deputy director of the CDC Immunization Safety Office.

“Overall, the data are reassuring with respect to vaccine safety in pregnant women,” he told this news organization.

Dr. Shimabukuro presented the data during a March 1 meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, a group of health experts selected by the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

The CDC has included pregnancy along with other underlying conditions that qualify people to be offered vaccines in the third priority tier (Phase 1c).

“There is evidence that pregnant women who get COVID-19 are at increased risk of severe illness and complications from severe illness,” Dr. Shimabukuro explained. “And there is also evidence that pregnant persons who get COVID-19 may be at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends that “COVID-19 vaccines should not be withheld from pregnant individuals.”

By contrast, the World Health Organization recommends the vaccines only for those pregnant women who are “at high risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (for example, health workers) or who have comorbidities which add to their risk of severe disease.”

Not enough information was available from the pivotal trials of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to assess risk in pregnant women, according to these manufacturers. Pfizer has announced a follow-up trial of its vaccine in healthy pregnant women.

Analyzing surveillance data

To better assess whether the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines cause problems in pregnancy or childbirth, Dr. Shimabukuro and colleagues analyzed data from V-Safe and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS).

The CDC encourages providers to inform people they vaccinate about the V-Safe program. Participants can voluntarily enter their data through a website, and may receive follow-up text messages and phone calls from the CDC asking for additional information at various times after vaccination. It is not a systematic survey, and the sample is not necessarily representative of everyone who gets the vaccine, Dr. Shimabukuro noted.

At the time of the study, V-Safe recorded 55,220,364 reports from people who received at least one dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine through Feb. 16. These included 30,494 pregnancies, of which 16,039 were in women who received the Pfizer vaccine and 14,455 in women who received the Moderna vaccine.

Analyzing data collected through Jan. 13, 2021, the researchers found that both local and systemic reactions were similar between pregnant and nonpregnant women aged 16-54 years.

Most women reported pain, and some reported swelling, redness, and itching at the injection site. Of systemic reactions, fatigue was the most common, followed by headache, myalgia, chills, nausea, and fever. The systemic reactions were more common with the second Pfizer dose; fatigue affected a majority of both pregnant and nonpregnant women. Data on the second Moderna dose were not available.

The CDC enrolled 1,815 pregnant women for additional follow-up, among whom there were 275 completed pregnancies and 232 live births.

Rates of outcomes “of interest” were no higher among these women than in the general population.

In contrast to V-Safe, data from VAERS, comanaged by the CDC and U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are from spontaneous reports of adverse events. The sources for those reports are varied. “That could be the health care provider,” Dr. Shimabukuro said. “That could be the patient themselves. It could be a caregiver for children.”

Just 154 VAERS reports through Feb. 16 concerned pregnant women, and of these, only 42 (27%) were for pregnancy-specific conditions, with the other 73% representing the types of adverse events reported for the general population of vaccinated people, such as headache and fatigue.

Of the 42 pregnancy-related events, there were 29 spontaneous abortions or miscarriages, with the remainder divided among 10 other pregnancy and neonatal conditions.

“When we looked at those outcomes and we compared the reporting rates, based on known background rates of these conditions, we did not see anything unexpected or concerning with respect to pregnancy or neonatal-specific conditions,” Dr. Shimabukuro said about the VAERS data.

The CDC did not collect data on fertility. “We’ve done a lot of work with other vaccines,” said Dr. Shimabukuro. “And just from a biological basis, we don’t have any evidence that vaccination, just in general, causes fertility problems.”

Also, Dr. Shimabukuro noted that the COVID-19 vaccine made by Janssen/Johnson & Johnson did not receive emergency authorization from the FDA in time to be included in the current report, but is being tracked for future reports.

Vaccination could benefit infants

In addition to the new safety data, experts continue to remind clinicians and the public that vaccination during pregnancy could benefit offspring. The unborn babies of pregnant women who receive the COVID-19 vaccine could be protected from the virus for the first several months of their lives, said White House COVID-19 czar Anthony Fauci, MD, at a briefing on March 10.

“We’ve seen this with many other vaccines,” Dr. Fauci said. “That’s a very good way you can get protection for the mother during pregnancy and also a transfer of protection for the infant, which will last a few months following the birth.”

Dr. Fauci also noted that the same vaccine platform used in Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine was successfully used for Ebola in pregnant women in Africa.

Dr. Shimabukuro has reported no relevant financial relationships.

Lindsay Kalter contributed to the reporting for this story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pregnant women can safely get vaccinated with the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines for COVID-19, surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest.

More than 30,000 women who received these vaccines have reported pregnancies through the CDC’s V-Safe voluntary reporting system, and their rates of complications are not significantly different from those of unvaccinated pregnant women, said Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA, deputy director of the CDC Immunization Safety Office.

“Overall, the data are reassuring with respect to vaccine safety in pregnant women,” he told this news organization.

Dr. Shimabukuro presented the data during a March 1 meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, a group of health experts selected by the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

The CDC has included pregnancy along with other underlying conditions that qualify people to be offered vaccines in the third priority tier (Phase 1c).

“There is evidence that pregnant women who get COVID-19 are at increased risk of severe illness and complications from severe illness,” Dr. Shimabukuro explained. “And there is also evidence that pregnant persons who get COVID-19 may be at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends that “COVID-19 vaccines should not be withheld from pregnant individuals.”

By contrast, the World Health Organization recommends the vaccines only for those pregnant women who are “at high risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (for example, health workers) or who have comorbidities which add to their risk of severe disease.”

Not enough information was available from the pivotal trials of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to assess risk in pregnant women, according to these manufacturers. Pfizer has announced a follow-up trial of its vaccine in healthy pregnant women.

Analyzing surveillance data

To better assess whether the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines cause problems in pregnancy or childbirth, Dr. Shimabukuro and colleagues analyzed data from V-Safe and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS).

The CDC encourages providers to inform people they vaccinate about the V-Safe program. Participants can voluntarily enter their data through a website, and may receive follow-up text messages and phone calls from the CDC asking for additional information at various times after vaccination. It is not a systematic survey, and the sample is not necessarily representative of everyone who gets the vaccine, Dr. Shimabukuro noted.

At the time of the study, V-Safe recorded 55,220,364 reports from people who received at least one dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine through Feb. 16. These included 30,494 pregnancies, of which 16,039 were in women who received the Pfizer vaccine and 14,455 in women who received the Moderna vaccine.

Analyzing data collected through Jan. 13, 2021, the researchers found that both local and systemic reactions were similar between pregnant and nonpregnant women aged 16-54 years.

Most women reported pain, and some reported swelling, redness, and itching at the injection site. Of systemic reactions, fatigue was the most common, followed by headache, myalgia, chills, nausea, and fever. The systemic reactions were more common with the second Pfizer dose; fatigue affected a majority of both pregnant and nonpregnant women. Data on the second Moderna dose were not available.

The CDC enrolled 1,815 pregnant women for additional follow-up, among whom there were 275 completed pregnancies and 232 live births.

Rates of outcomes “of interest” were no higher among these women than in the general population.

In contrast to V-Safe, data from VAERS, comanaged by the CDC and U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are from spontaneous reports of adverse events. The sources for those reports are varied. “That could be the health care provider,” Dr. Shimabukuro said. “That could be the patient themselves. It could be a caregiver for children.”

Just 154 VAERS reports through Feb. 16 concerned pregnant women, and of these, only 42 (27%) were for pregnancy-specific conditions, with the other 73% representing the types of adverse events reported for the general population of vaccinated people, such as headache and fatigue.

Of the 42 pregnancy-related events, there were 29 spontaneous abortions or miscarriages, with the remainder divided among 10 other pregnancy and neonatal conditions.

“When we looked at those outcomes and we compared the reporting rates, based on known background rates of these conditions, we did not see anything unexpected or concerning with respect to pregnancy or neonatal-specific conditions,” Dr. Shimabukuro said about the VAERS data.

The CDC did not collect data on fertility. “We’ve done a lot of work with other vaccines,” said Dr. Shimabukuro. “And just from a biological basis, we don’t have any evidence that vaccination, just in general, causes fertility problems.”

Also, Dr. Shimabukuro noted that the COVID-19 vaccine made by Janssen/Johnson & Johnson did not receive emergency authorization from the FDA in time to be included in the current report, but is being tracked for future reports.

Vaccination could benefit infants

In addition to the new safety data, experts continue to remind clinicians and the public that vaccination during pregnancy could benefit offspring. The unborn babies of pregnant women who receive the COVID-19 vaccine could be protected from the virus for the first several months of their lives, said White House COVID-19 czar Anthony Fauci, MD, at a briefing on March 10.

“We’ve seen this with many other vaccines,” Dr. Fauci said. “That’s a very good way you can get protection for the mother during pregnancy and also a transfer of protection for the infant, which will last a few months following the birth.”

Dr. Fauci also noted that the same vaccine platform used in Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine was successfully used for Ebola in pregnant women in Africa.

Dr. Shimabukuro has reported no relevant financial relationships.

Lindsay Kalter contributed to the reporting for this story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pregnant women can safely get vaccinated with the Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna vaccines for COVID-19, surveillance data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention suggest.

More than 30,000 women who received these vaccines have reported pregnancies through the CDC’s V-Safe voluntary reporting system, and their rates of complications are not significantly different from those of unvaccinated pregnant women, said Tom Shimabukuro, MD, MPH, MBA, deputy director of the CDC Immunization Safety Office.

“Overall, the data are reassuring with respect to vaccine safety in pregnant women,” he told this news organization.

Dr. Shimabukuro presented the data during a March 1 meeting of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, a group of health experts selected by the Secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

The CDC has included pregnancy along with other underlying conditions that qualify people to be offered vaccines in the third priority tier (Phase 1c).

“There is evidence that pregnant women who get COVID-19 are at increased risk of severe illness and complications from severe illness,” Dr. Shimabukuro explained. “And there is also evidence that pregnant persons who get COVID-19 may be at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes.”

The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology recommends that “COVID-19 vaccines should not be withheld from pregnant individuals.”

By contrast, the World Health Organization recommends the vaccines only for those pregnant women who are “at high risk of exposure to SARS-CoV-2 (for example, health workers) or who have comorbidities which add to their risk of severe disease.”

Not enough information was available from the pivotal trials of the Moderna and Pfizer vaccines to assess risk in pregnant women, according to these manufacturers. Pfizer has announced a follow-up trial of its vaccine in healthy pregnant women.

Analyzing surveillance data

To better assess whether the Pfizer or Moderna vaccines cause problems in pregnancy or childbirth, Dr. Shimabukuro and colleagues analyzed data from V-Safe and the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS).

The CDC encourages providers to inform people they vaccinate about the V-Safe program. Participants can voluntarily enter their data through a website, and may receive follow-up text messages and phone calls from the CDC asking for additional information at various times after vaccination. It is not a systematic survey, and the sample is not necessarily representative of everyone who gets the vaccine, Dr. Shimabukuro noted.

At the time of the study, V-Safe recorded 55,220,364 reports from people who received at least one dose of the Pfizer or Moderna vaccine through Feb. 16. These included 30,494 pregnancies, of which 16,039 were in women who received the Pfizer vaccine and 14,455 in women who received the Moderna vaccine.

Analyzing data collected through Jan. 13, 2021, the researchers found that both local and systemic reactions were similar between pregnant and nonpregnant women aged 16-54 years.

Most women reported pain, and some reported swelling, redness, and itching at the injection site. Of systemic reactions, fatigue was the most common, followed by headache, myalgia, chills, nausea, and fever. The systemic reactions were more common with the second Pfizer dose; fatigue affected a majority of both pregnant and nonpregnant women. Data on the second Moderna dose were not available.

The CDC enrolled 1,815 pregnant women for additional follow-up, among whom there were 275 completed pregnancies and 232 live births.

Rates of outcomes “of interest” were no higher among these women than in the general population.

In contrast to V-Safe, data from VAERS, comanaged by the CDC and U.S. Food and Drug Administration, are from spontaneous reports of adverse events. The sources for those reports are varied. “That could be the health care provider,” Dr. Shimabukuro said. “That could be the patient themselves. It could be a caregiver for children.”

Just 154 VAERS reports through Feb. 16 concerned pregnant women, and of these, only 42 (27%) were for pregnancy-specific conditions, with the other 73% representing the types of adverse events reported for the general population of vaccinated people, such as headache and fatigue.

Of the 42 pregnancy-related events, there were 29 spontaneous abortions or miscarriages, with the remainder divided among 10 other pregnancy and neonatal conditions.

“When we looked at those outcomes and we compared the reporting rates, based on known background rates of these conditions, we did not see anything unexpected or concerning with respect to pregnancy or neonatal-specific conditions,” Dr. Shimabukuro said about the VAERS data.

The CDC did not collect data on fertility. “We’ve done a lot of work with other vaccines,” said Dr. Shimabukuro. “And just from a biological basis, we don’t have any evidence that vaccination, just in general, causes fertility problems.”

Also, Dr. Shimabukuro noted that the COVID-19 vaccine made by Janssen/Johnson & Johnson did not receive emergency authorization from the FDA in time to be included in the current report, but is being tracked for future reports.

Vaccination could benefit infants

In addition to the new safety data, experts continue to remind clinicians and the public that vaccination during pregnancy could benefit offspring. The unborn babies of pregnant women who receive the COVID-19 vaccine could be protected from the virus for the first several months of their lives, said White House COVID-19 czar Anthony Fauci, MD, at a briefing on March 10.

“We’ve seen this with many other vaccines,” Dr. Fauci said. “That’s a very good way you can get protection for the mother during pregnancy and also a transfer of protection for the infant, which will last a few months following the birth.”

Dr. Fauci also noted that the same vaccine platform used in Johnson & Johnson’s COVID-19 vaccine was successfully used for Ebola in pregnant women in Africa.

Dr. Shimabukuro has reported no relevant financial relationships.

Lindsay Kalter contributed to the reporting for this story.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AI detects ugly-duckling skin lesions for melanoma follow-up

.

The system could use photographs of large areas of patients’ bodies taken with ordinary cameras in primary care or by the patients themselves to screen for early-stage melanoma, said Luis R. Soenksen, PhD, a postdoctoral associate and venture builder at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass.

“We believe we’re providing technology for that to happen at a massive scale, which is what is needed to reduce mortality rates,” he said in an interview.

He and his colleagues published their findings in Science Translational Medicine.

Diagnosing skin lesions has already proved one of the most promising medical applications of AI. In a 2017 paper, researchers reported that a deep neural network had classified skin lesions more accurately than did dermatologists. But so far, most such programs depend on experts to preselect the lesions worthy of analysis. And they use images from dermoscopy or single-lesion near-field photography.

Dr. Soenksen and colleagues wanted a system that could use a variety of cameras such as those in smartphones under a variety of conditions to assess lesions over wide areas of anatomy.

So they programmed their convolutional neural network to simultaneously use two approaches for screening lesions. Like the earlier systems, theirs looks for characteristics of individual lesions, such as asymmetry, border unevenness, color distribution, diameter, and evolution (ABCDE.) But it also looks for lesion saliency, a comparison of the lesions on the skin of one individual to identify the “ugly ducklings” that stand out from the rest.

They trained the system using 20,388 wide-field images from 133 patients at the Hospital Gregorio Marañón in Madrid, as well as publicly available images. The images were taken with a variety of consumer-grade cameras, about half of them nondermoscopy, and included backgrounds, skin edges, bare skin sections, nonsuspicious pigmented lesions, and suspicious pigmented lesions. The lesions in the images were visually classified by a consensus of three board-certified dermatologists.

Once they trained the system, the researchers tested it on another 6,796 images from the same patients, using the dermatologists’ classification as the gold standard. The system distinguished the suspicious lesions with 90.3% sensitivity (true positive), 89.9% specificity (true negative), and 86.56% accuracy.

Dr. Soenksen said he could envision photos acquired for screening in three scenarios. First, people could photograph themselves, or someone else at their homes could photograph them. These photos could even include whole nude bodies.

Second, clinicians could photograph patients’ body parts during medical visits for other purposes. “It makes sense to do these evaluations in the point of care where a referral can actually happen, like the primary care office,” said Dr. Soenksen.

Third, photos could be taken at places where people show up in bathing suits.

In each scenario, the system would then tell patients whether any lesions needed evaluation by a dermatologist.

To ensure privacy, Dr. Soenksen envisions using devices that do not transmit all the data to the cloud but instead do at least some of the calculations on their own. High-end smartphones have sufficient computing capacity for that, he said.

In their next phase of this work, the researchers would like to test the system on more skin of color cases and in more varied conditions, said Dr. Soenksen. And they would like to put it through randomized clinical trials, potentially using biopsies to validate the results.

That’s a key step, said Veronica Rotemberg, MD, PhD, director of the dermatology imaging informatics program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“Usually when we think about melanoma, we think of histology as the gold standard, or specific subtypes of melanoma as a gold standard,” she said in an interview.

The technology also raises the question of excessive screening, she said. “Identifying the ugly duckling could be extremely important in finding more melanoma,” she said. “But in a patient who doesn’t have melanoma, it could lead to a lot of unnecessary biopsies.”

The sheer number of referrals generated by such a system could overwhelm the dermatologists assigned to follow up on them, she added.

Still, Dr. Rotemberg said, the study is “a good proof of concept.” Ugly duckling analysis is a very active area of AI research with thousands of teams of researchers worldwide working on systems similar to this one, she added. “I’m so excited for the authors.”

Neither Dr. Soenksen nor Dr. Rotemberg disclosed any relevant financial interests.

.

The system could use photographs of large areas of patients’ bodies taken with ordinary cameras in primary care or by the patients themselves to screen for early-stage melanoma, said Luis R. Soenksen, PhD, a postdoctoral associate and venture builder at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass.

“We believe we’re providing technology for that to happen at a massive scale, which is what is needed to reduce mortality rates,” he said in an interview.

He and his colleagues published their findings in Science Translational Medicine.

Diagnosing skin lesions has already proved one of the most promising medical applications of AI. In a 2017 paper, researchers reported that a deep neural network had classified skin lesions more accurately than did dermatologists. But so far, most such programs depend on experts to preselect the lesions worthy of analysis. And they use images from dermoscopy or single-lesion near-field photography.

Dr. Soenksen and colleagues wanted a system that could use a variety of cameras such as those in smartphones under a variety of conditions to assess lesions over wide areas of anatomy.

So they programmed their convolutional neural network to simultaneously use two approaches for screening lesions. Like the earlier systems, theirs looks for characteristics of individual lesions, such as asymmetry, border unevenness, color distribution, diameter, and evolution (ABCDE.) But it also looks for lesion saliency, a comparison of the lesions on the skin of one individual to identify the “ugly ducklings” that stand out from the rest.

They trained the system using 20,388 wide-field images from 133 patients at the Hospital Gregorio Marañón in Madrid, as well as publicly available images. The images were taken with a variety of consumer-grade cameras, about half of them nondermoscopy, and included backgrounds, skin edges, bare skin sections, nonsuspicious pigmented lesions, and suspicious pigmented lesions. The lesions in the images were visually classified by a consensus of three board-certified dermatologists.

Once they trained the system, the researchers tested it on another 6,796 images from the same patients, using the dermatologists’ classification as the gold standard. The system distinguished the suspicious lesions with 90.3% sensitivity (true positive), 89.9% specificity (true negative), and 86.56% accuracy.

Dr. Soenksen said he could envision photos acquired for screening in three scenarios. First, people could photograph themselves, or someone else at their homes could photograph them. These photos could even include whole nude bodies.

Second, clinicians could photograph patients’ body parts during medical visits for other purposes. “It makes sense to do these evaluations in the point of care where a referral can actually happen, like the primary care office,” said Dr. Soenksen.

Third, photos could be taken at places where people show up in bathing suits.

In each scenario, the system would then tell patients whether any lesions needed evaluation by a dermatologist.

To ensure privacy, Dr. Soenksen envisions using devices that do not transmit all the data to the cloud but instead do at least some of the calculations on their own. High-end smartphones have sufficient computing capacity for that, he said.

In their next phase of this work, the researchers would like to test the system on more skin of color cases and in more varied conditions, said Dr. Soenksen. And they would like to put it through randomized clinical trials, potentially using biopsies to validate the results.

That’s a key step, said Veronica Rotemberg, MD, PhD, director of the dermatology imaging informatics program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“Usually when we think about melanoma, we think of histology as the gold standard, or specific subtypes of melanoma as a gold standard,” she said in an interview.

The technology also raises the question of excessive screening, she said. “Identifying the ugly duckling could be extremely important in finding more melanoma,” she said. “But in a patient who doesn’t have melanoma, it could lead to a lot of unnecessary biopsies.”

The sheer number of referrals generated by such a system could overwhelm the dermatologists assigned to follow up on them, she added.

Still, Dr. Rotemberg said, the study is “a good proof of concept.” Ugly duckling analysis is a very active area of AI research with thousands of teams of researchers worldwide working on systems similar to this one, she added. “I’m so excited for the authors.”

Neither Dr. Soenksen nor Dr. Rotemberg disclosed any relevant financial interests.

.

The system could use photographs of large areas of patients’ bodies taken with ordinary cameras in primary care or by the patients themselves to screen for early-stage melanoma, said Luis R. Soenksen, PhD, a postdoctoral associate and venture builder at Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, Mass.

“We believe we’re providing technology for that to happen at a massive scale, which is what is needed to reduce mortality rates,” he said in an interview.

He and his colleagues published their findings in Science Translational Medicine.

Diagnosing skin lesions has already proved one of the most promising medical applications of AI. In a 2017 paper, researchers reported that a deep neural network had classified skin lesions more accurately than did dermatologists. But so far, most such programs depend on experts to preselect the lesions worthy of analysis. And they use images from dermoscopy or single-lesion near-field photography.

Dr. Soenksen and colleagues wanted a system that could use a variety of cameras such as those in smartphones under a variety of conditions to assess lesions over wide areas of anatomy.

So they programmed their convolutional neural network to simultaneously use two approaches for screening lesions. Like the earlier systems, theirs looks for characteristics of individual lesions, such as asymmetry, border unevenness, color distribution, diameter, and evolution (ABCDE.) But it also looks for lesion saliency, a comparison of the lesions on the skin of one individual to identify the “ugly ducklings” that stand out from the rest.

They trained the system using 20,388 wide-field images from 133 patients at the Hospital Gregorio Marañón in Madrid, as well as publicly available images. The images were taken with a variety of consumer-grade cameras, about half of them nondermoscopy, and included backgrounds, skin edges, bare skin sections, nonsuspicious pigmented lesions, and suspicious pigmented lesions. The lesions in the images were visually classified by a consensus of three board-certified dermatologists.

Once they trained the system, the researchers tested it on another 6,796 images from the same patients, using the dermatologists’ classification as the gold standard. The system distinguished the suspicious lesions with 90.3% sensitivity (true positive), 89.9% specificity (true negative), and 86.56% accuracy.

Dr. Soenksen said he could envision photos acquired for screening in three scenarios. First, people could photograph themselves, or someone else at their homes could photograph them. These photos could even include whole nude bodies.

Second, clinicians could photograph patients’ body parts during medical visits for other purposes. “It makes sense to do these evaluations in the point of care where a referral can actually happen, like the primary care office,” said Dr. Soenksen.

Third, photos could be taken at places where people show up in bathing suits.

In each scenario, the system would then tell patients whether any lesions needed evaluation by a dermatologist.

To ensure privacy, Dr. Soenksen envisions using devices that do not transmit all the data to the cloud but instead do at least some of the calculations on their own. High-end smartphones have sufficient computing capacity for that, he said.

In their next phase of this work, the researchers would like to test the system on more skin of color cases and in more varied conditions, said Dr. Soenksen. And they would like to put it through randomized clinical trials, potentially using biopsies to validate the results.

That’s a key step, said Veronica Rotemberg, MD, PhD, director of the dermatology imaging informatics program at Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, New York.

“Usually when we think about melanoma, we think of histology as the gold standard, or specific subtypes of melanoma as a gold standard,” she said in an interview.

The technology also raises the question of excessive screening, she said. “Identifying the ugly duckling could be extremely important in finding more melanoma,” she said. “But in a patient who doesn’t have melanoma, it could lead to a lot of unnecessary biopsies.”

The sheer number of referrals generated by such a system could overwhelm the dermatologists assigned to follow up on them, she added.

Still, Dr. Rotemberg said, the study is “a good proof of concept.” Ugly duckling analysis is a very active area of AI research with thousands of teams of researchers worldwide working on systems similar to this one, she added. “I’m so excited for the authors.”

Neither Dr. Soenksen nor Dr. Rotemberg disclosed any relevant financial interests.

COVID-19 vaccination recommended for rheumatology patients

People with rheumatic diseases should get vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 as soon as possible, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends.

“It may be that people with rheumatic diseases are at increased risk of developing COVID or serious COVID-related complications,” Jonathan Hausmann, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an ACR podcast. “So the need to prevent COVID-19 is incredibly important in this group of patients.”

The guidelines recommend a delay in vaccination only in rare circumstances, such as for patients with very severe illness or who have recently been administered rituximab, Jeffrey R. Curtis, MD, MPH, lead author of the guidelines, said in the podcast.

“Our members have been inundated with questions and concerns from their patients on whether they should receive the vaccine,” ACR President David Karp, MD, PhD, said in a press release.

So the ACR convened a panel of nine rheumatologists, two infectious disease specialists, and two public health experts. Over the course of 8 weeks, the task force reviewed the literature and agreed on recommendations. The organization posted a summary of the guidelines on its website after its board of directors approved it Feb. 8. The paper is pending journal peer review.

Some risks are real

The task force confined its research to the COVID-19 vaccines being offered by Pfizer and Moderna because they are currently the only ones approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It found no reason to distinguish between the two vaccines in its recommendations.

Because little research has directly addressed the question concerning COVID-19 vaccination for patients with rheumatic diseases, the task force extrapolated from data on other vaccinations in people with rheumatic disease and on the COVID-19 vaccinations in other populations.

It analyzed reports that other types of vaccination, such as for influenza, triggered flares of rheumatic conditions. “It is really individual case reports or small cohorts where there may be a somewhat higher incidence of flare, but it’s usually not very large in its magnitude nor duration,” said Dr. Curtis of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The task force also considered the possibility that vaccinations could lead to a new autoimmune disorder, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome or Bell palsy. The risk is real, the task force decided, but not significant enough to influence their recommendations.

Likewise, in immunocompromised people, vaccinations with live virus, such as those for shingles, might trigger the infection the vaccination is meant to prevent. But this can’t happen with the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines because they contain messenger RNA instead of live viruses, Dr. Curtis said.

Although it might be optimal to administer the vaccines when rheumatic diseases are quiescent, the urgency of getting vaccinated overrides that consideration, Dr. Curtis said. “By and large, there was a general consensus to not want to delay vaccination until somebody was stable and doing great, because you don’t know how long that’s going to be,” he said.

How well does it work?

One unanswered question is whether the COVID-19 vaccines work as well for patients with rheumatic diseases. The task force was reassured by data showing efficacy across a range of subgroups, including some with immunosenescence, Dr. Curtis said. “But until we have data in rheumatology patients, we’re just not going to know,” he said.

The guidelines specify that some drug regimens be modified when patients are vaccinated.

For patients taking rituximab, vaccination should be delayed, but only for those who are able to maintain safe social distancing to reduce the risk for COVID-19 exposure, Dr. Curtis said. “If somebody has just gotten rituximab recently, it might be more ideal to complete the vaccine series about 2-4 weeks before the next rituximab dose,” he said. “So if you are giving that therapy, say, at 6-month intervals, if you could vaccinate them at around month 5 from the most recent rituximab cycle, that might be more ideal.”

The guidance calls for withholding JAK inhibitors for a week after each vaccine dose is administered.

It calls for holding SQ abatacept 1 week prior and 1 week after the first COVID-19 vaccine dose, with no interruption after the second dose.

For abatacept IV, clinicians should “time vaccine administration so that the first vaccination will occur 4 weeks after abatacept infusion (i.e., the entire dosing interval), and postpone the subsequent abatacept infusion by 1 week (i.e., a 5-week gap in total).” It recommends no medication adjustment for the second vaccine dose.

For cyclophosphamide, the guidance recommends timing administration to occur about a week after each vaccine dose, when feasible.

None of this advice should supersede clinical judgment, Dr. Curtis said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with rheumatic diseases should get vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 as soon as possible, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends.

“It may be that people with rheumatic diseases are at increased risk of developing COVID or serious COVID-related complications,” Jonathan Hausmann, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an ACR podcast. “So the need to prevent COVID-19 is incredibly important in this group of patients.”

The guidelines recommend a delay in vaccination only in rare circumstances, such as for patients with very severe illness or who have recently been administered rituximab, Jeffrey R. Curtis, MD, MPH, lead author of the guidelines, said in the podcast.

“Our members have been inundated with questions and concerns from their patients on whether they should receive the vaccine,” ACR President David Karp, MD, PhD, said in a press release.

So the ACR convened a panel of nine rheumatologists, two infectious disease specialists, and two public health experts. Over the course of 8 weeks, the task force reviewed the literature and agreed on recommendations. The organization posted a summary of the guidelines on its website after its board of directors approved it Feb. 8. The paper is pending journal peer review.

Some risks are real

The task force confined its research to the COVID-19 vaccines being offered by Pfizer and Moderna because they are currently the only ones approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It found no reason to distinguish between the two vaccines in its recommendations.

Because little research has directly addressed the question concerning COVID-19 vaccination for patients with rheumatic diseases, the task force extrapolated from data on other vaccinations in people with rheumatic disease and on the COVID-19 vaccinations in other populations.

It analyzed reports that other types of vaccination, such as for influenza, triggered flares of rheumatic conditions. “It is really individual case reports or small cohorts where there may be a somewhat higher incidence of flare, but it’s usually not very large in its magnitude nor duration,” said Dr. Curtis of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The task force also considered the possibility that vaccinations could lead to a new autoimmune disorder, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome or Bell palsy. The risk is real, the task force decided, but not significant enough to influence their recommendations.

Likewise, in immunocompromised people, vaccinations with live virus, such as those for shingles, might trigger the infection the vaccination is meant to prevent. But this can’t happen with the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines because they contain messenger RNA instead of live viruses, Dr. Curtis said.

Although it might be optimal to administer the vaccines when rheumatic diseases are quiescent, the urgency of getting vaccinated overrides that consideration, Dr. Curtis said. “By and large, there was a general consensus to not want to delay vaccination until somebody was stable and doing great, because you don’t know how long that’s going to be,” he said.

How well does it work?

One unanswered question is whether the COVID-19 vaccines work as well for patients with rheumatic diseases. The task force was reassured by data showing efficacy across a range of subgroups, including some with immunosenescence, Dr. Curtis said. “But until we have data in rheumatology patients, we’re just not going to know,” he said.

The guidelines specify that some drug regimens be modified when patients are vaccinated.

For patients taking rituximab, vaccination should be delayed, but only for those who are able to maintain safe social distancing to reduce the risk for COVID-19 exposure, Dr. Curtis said. “If somebody has just gotten rituximab recently, it might be more ideal to complete the vaccine series about 2-4 weeks before the next rituximab dose,” he said. “So if you are giving that therapy, say, at 6-month intervals, if you could vaccinate them at around month 5 from the most recent rituximab cycle, that might be more ideal.”

The guidance calls for withholding JAK inhibitors for a week after each vaccine dose is administered.

It calls for holding SQ abatacept 1 week prior and 1 week after the first COVID-19 vaccine dose, with no interruption after the second dose.

For abatacept IV, clinicians should “time vaccine administration so that the first vaccination will occur 4 weeks after abatacept infusion (i.e., the entire dosing interval), and postpone the subsequent abatacept infusion by 1 week (i.e., a 5-week gap in total).” It recommends no medication adjustment for the second vaccine dose.

For cyclophosphamide, the guidance recommends timing administration to occur about a week after each vaccine dose, when feasible.

None of this advice should supersede clinical judgment, Dr. Curtis said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

People with rheumatic diseases should get vaccinated against SARS-CoV-2 as soon as possible, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) recommends.

“It may be that people with rheumatic diseases are at increased risk of developing COVID or serious COVID-related complications,” Jonathan Hausmann, MD, assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, said in an ACR podcast. “So the need to prevent COVID-19 is incredibly important in this group of patients.”

The guidelines recommend a delay in vaccination only in rare circumstances, such as for patients with very severe illness or who have recently been administered rituximab, Jeffrey R. Curtis, MD, MPH, lead author of the guidelines, said in the podcast.

“Our members have been inundated with questions and concerns from their patients on whether they should receive the vaccine,” ACR President David Karp, MD, PhD, said in a press release.

So the ACR convened a panel of nine rheumatologists, two infectious disease specialists, and two public health experts. Over the course of 8 weeks, the task force reviewed the literature and agreed on recommendations. The organization posted a summary of the guidelines on its website after its board of directors approved it Feb. 8. The paper is pending journal peer review.

Some risks are real

The task force confined its research to the COVID-19 vaccines being offered by Pfizer and Moderna because they are currently the only ones approved by the Food and Drug Administration. It found no reason to distinguish between the two vaccines in its recommendations.

Because little research has directly addressed the question concerning COVID-19 vaccination for patients with rheumatic diseases, the task force extrapolated from data on other vaccinations in people with rheumatic disease and on the COVID-19 vaccinations in other populations.

It analyzed reports that other types of vaccination, such as for influenza, triggered flares of rheumatic conditions. “It is really individual case reports or small cohorts where there may be a somewhat higher incidence of flare, but it’s usually not very large in its magnitude nor duration,” said Dr. Curtis of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

The task force also considered the possibility that vaccinations could lead to a new autoimmune disorder, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome or Bell palsy. The risk is real, the task force decided, but not significant enough to influence their recommendations.

Likewise, in immunocompromised people, vaccinations with live virus, such as those for shingles, might trigger the infection the vaccination is meant to prevent. But this can’t happen with the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines because they contain messenger RNA instead of live viruses, Dr. Curtis said.

Although it might be optimal to administer the vaccines when rheumatic diseases are quiescent, the urgency of getting vaccinated overrides that consideration, Dr. Curtis said. “By and large, there was a general consensus to not want to delay vaccination until somebody was stable and doing great, because you don’t know how long that’s going to be,” he said.

How well does it work?

One unanswered question is whether the COVID-19 vaccines work as well for patients with rheumatic diseases. The task force was reassured by data showing efficacy across a range of subgroups, including some with immunosenescence, Dr. Curtis said. “But until we have data in rheumatology patients, we’re just not going to know,” he said.

The guidelines specify that some drug regimens be modified when patients are vaccinated.

For patients taking rituximab, vaccination should be delayed, but only for those who are able to maintain safe social distancing to reduce the risk for COVID-19 exposure, Dr. Curtis said. “If somebody has just gotten rituximab recently, it might be more ideal to complete the vaccine series about 2-4 weeks before the next rituximab dose,” he said. “So if you are giving that therapy, say, at 6-month intervals, if you could vaccinate them at around month 5 from the most recent rituximab cycle, that might be more ideal.”

The guidance calls for withholding JAK inhibitors for a week after each vaccine dose is administered.

It calls for holding SQ abatacept 1 week prior and 1 week after the first COVID-19 vaccine dose, with no interruption after the second dose.

For abatacept IV, clinicians should “time vaccine administration so that the first vaccination will occur 4 weeks after abatacept infusion (i.e., the entire dosing interval), and postpone the subsequent abatacept infusion by 1 week (i.e., a 5-week gap in total).” It recommends no medication adjustment for the second vaccine dose.

For cyclophosphamide, the guidance recommends timing administration to occur about a week after each vaccine dose, when feasible.

None of this advice should supersede clinical judgment, Dr. Curtis said.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Steroid and immunoglobulin standard of care for MIS-C

The combination of methylprednisolone and intravenous immunoglobulins works better than intravenous immunoglobulins alone for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), researchers say.

“I’m not sure it’s the best treatment because we have not studied every possible treatment,” François Angoulvant, MD, PhD, told this news organization, “but right now, it’s the standard of care.”

Dr. Angoulvant, a professor of pediatrics at University of Paris, and colleagues published a comparison of the two treatments in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

A small percentage of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 develop MIS-C about 2 to 4 weeks later. It is considered a separate disease entity from COVID-19 and is associated with persistent fever, digestive symptoms, rash, bilateral nonpurulent conjunctivitis, mucocutaneous inflammation signs, and frequent cardiovascular involvement. In more than 60% of cases, it leads to hemodynamic failure, with acute cardiac dysfunction.

Because MIS-C resembles Kawasaki disease, clinicians modeled their treatment on that condition and started with immunoglobulins alone, Dr. Angoulvant said.

Based on expert opinion, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom published a consensus statement in Sept. listing immunoglobulins alone as the first-line treatment.

But anecdotal reports have emerged that combining the immunoglobulins with a corticosteroid worked better. To investigate this possibility, Dr. Angoulvant and colleagues analyzed records of MIS-C cases in France, where physicians are required to report all suspected cases of MIS-C to the French National Public Health Agency.

Among the 181 cases they scrutinized, 111 fulfilled the World Health Organization criteria for MIS-C. Of these, the researchers were able to match 64 patients who had received immunoglobulins alone with 32 who had received the combined therapy and could be matched using propensity scores.

The researchers defined treatment failure as persistence of fever for 2 days after the start of therapy or recurrence of fever within a week. By this measure, the combination treatment failed in only 9% of cases while immunoglobulins alone failed in 38% of cases. The difference was statistically significant (P = .008). Most of those for whom these treatments failed received second-line treatments such as steroids or biological agents.

Patients treated with the combination therapy also had a lower risk of secondary acute left ventricular dysfunction (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.66) and a lower risk of needing hemodynamic support (OR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.06-0.76).

Those receiving the combination therapy spent a mean of 4 days in the pediatric intensive care unit compared with 6 days for those receiving immunoglobulins alone. (Difference in days, −2.4; 95% CI, −4.0 to −0.7; P = .005).

There are few drawbacks to the combination approach, Dr. Angoulvant said, as the side effects of corticosteroids are generally not severe and they can be anticipated because this class of medications has been used for many years.

The study raises the question of whether corticosteroids might work as well by themselves, but it could not be answered with this database as no one is using that approach in France, Dr. Angoulvant said. “I hope other teams around the world could bring us the answer.”

In the United States, most physicians appear to already be using the combination therapy, said David Teachey, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The reduction in time in pediatric intensive care and the reduced risk of cardiac dysfunction are important findings, he said.

This retrospective study falls short of the evidence provided by a randomized clinical trial, Dr. Teachey noted. But he acknowledged that few families would agree to participate in such a trial as they would have to take a chance that the sick children would receive a less effective therapy than what they would otherwise get. “It’s hard to [talk] about a therapy reduction,” he told this news organization.

Given that impediment, he agreed with Dr. Angoulvant that the current study and others like it may provide the best data available pointing to a treatment approach for MIS-C.

The study received an unrestricted grant from Pfizer. The French COVID-19 Paediatric Inflammation Consortium received an unrestricted grant from the Square Foundation (Grandir–Fonds de Solidarité pour L’Enfance). Dr. Angoulvant and Dr. Teachey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The combination of methylprednisolone and intravenous immunoglobulins works better than intravenous immunoglobulins alone for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), researchers say.

“I’m not sure it’s the best treatment because we have not studied every possible treatment,” François Angoulvant, MD, PhD, told this news organization, “but right now, it’s the standard of care.”

Dr. Angoulvant, a professor of pediatrics at University of Paris, and colleagues published a comparison of the two treatments in the Journal of the American Medical Association.

A small percentage of children infected with SARS-CoV-2 develop MIS-C about 2 to 4 weeks later. It is considered a separate disease entity from COVID-19 and is associated with persistent fever, digestive symptoms, rash, bilateral nonpurulent conjunctivitis, mucocutaneous inflammation signs, and frequent cardiovascular involvement. In more than 60% of cases, it leads to hemodynamic failure, with acute cardiac dysfunction.

Because MIS-C resembles Kawasaki disease, clinicians modeled their treatment on that condition and started with immunoglobulins alone, Dr. Angoulvant said.

Based on expert opinion, the National Health Service in the United Kingdom published a consensus statement in Sept. listing immunoglobulins alone as the first-line treatment.

But anecdotal reports have emerged that combining the immunoglobulins with a corticosteroid worked better. To investigate this possibility, Dr. Angoulvant and colleagues analyzed records of MIS-C cases in France, where physicians are required to report all suspected cases of MIS-C to the French National Public Health Agency.

Among the 181 cases they scrutinized, 111 fulfilled the World Health Organization criteria for MIS-C. Of these, the researchers were able to match 64 patients who had received immunoglobulins alone with 32 who had received the combined therapy and could be matched using propensity scores.

The researchers defined treatment failure as persistence of fever for 2 days after the start of therapy or recurrence of fever within a week. By this measure, the combination treatment failed in only 9% of cases while immunoglobulins alone failed in 38% of cases. The difference was statistically significant (P = .008). Most of those for whom these treatments failed received second-line treatments such as steroids or biological agents.

Patients treated with the combination therapy also had a lower risk of secondary acute left ventricular dysfunction (odds ratio, 0.20; 95% confidence interval, 0.06-0.66) and a lower risk of needing hemodynamic support (OR, 0.21; 95% CI, 0.06-0.76).

Those receiving the combination therapy spent a mean of 4 days in the pediatric intensive care unit compared with 6 days for those receiving immunoglobulins alone. (Difference in days, −2.4; 95% CI, −4.0 to −0.7; P = .005).

There are few drawbacks to the combination approach, Dr. Angoulvant said, as the side effects of corticosteroids are generally not severe and they can be anticipated because this class of medications has been used for many years.

The study raises the question of whether corticosteroids might work as well by themselves, but it could not be answered with this database as no one is using that approach in France, Dr. Angoulvant said. “I hope other teams around the world could bring us the answer.”

In the United States, most physicians appear to already be using the combination therapy, said David Teachey, MD, an associate professor of pediatrics at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

The reduction in time in pediatric intensive care and the reduced risk of cardiac dysfunction are important findings, he said.

This retrospective study falls short of the evidence provided by a randomized clinical trial, Dr. Teachey noted. But he acknowledged that few families would agree to participate in such a trial as they would have to take a chance that the sick children would receive a less effective therapy than what they would otherwise get. “It’s hard to [talk] about a therapy reduction,” he told this news organization.

Given that impediment, he agreed with Dr. Angoulvant that the current study and others like it may provide the best data available pointing to a treatment approach for MIS-C.

The study received an unrestricted grant from Pfizer. The French COVID-19 Paediatric Inflammation Consortium received an unrestricted grant from the Square Foundation (Grandir–Fonds de Solidarité pour L’Enfance). Dr. Angoulvant and Dr. Teachey have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The combination of methylprednisolone and intravenous immunoglobulins works better than intravenous immunoglobulins alone for multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C), researchers say.

“I’m not sure it’s the best treatment because we have not studied every possible treatment,” François Angoulvant, MD, PhD, told this news organization, “but right now, it’s the standard of care.”

Dr. Angoulvant, a professor of pediatrics at University of Paris, and colleagues published a comparison of the two treatments in the Journal of the American Medical Association.