User login

Primary care workforce expanding, but mostly in cities

researchers say.

The finding may provide some reassurance for those who have worried about a shortage of health care workers and whether they will be able to meet the nation’s growing burden of chronic diseases.

“Access to primary care doctors is critical to population health and to reduce health care disparities in this country,” said Donglan Zhang, PhD, an assistant professor of public health at the University of Georgia, Athens.

However, many counties remain underserved, Dr. Zhang said in an interview. The need for primary care in the United States is increasing not only with population growth but because the population is aging.

Dr. Zhang and colleagues published the finding in JAMA Network Open.

Many previous reports have warned of a shortage in primary care providers. To examine recent trends in the primary care workforce, Dr. Zhang and colleagues obtained data on all the primary care clinicians registered with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services from 2009 to 2017.

For the study, the researchers included general practitioners, family physicians and internists without subspecialties, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. They then compared the number of providers with the number of residents in each county as recorded by the US Census, using urban or rural classifications for each county from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration defines a primary care “shortage” as fewer than 1 primary care practitioner per 3,500 people, the researchers focused on this ratio. They found that the number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants was increasing much faster than the number of primary care physicians. This was true especially in rural areas, but the percentage increase for both nurse practitioners and physician assistants was lower in rural areas versus urban.

The researchers also found that there were more primary care physicians per capita in counties with higher household incomes, a higher proportion of Asian residents, and a higher proportion of college graduates.

They didn’t find a significant association between the median household income and per capita number of nurse practitioners.

They found that counties with a higher proportion of Black and Asian residents had a higher number of nurse practitioners per capita. But they found an opposite association between the proportion of Black residents and the number of physician assistants per capita.

The authors hypothesized that health care reform, particularly the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, may explain the recent increase in the primary care workforce. The legislation expanded the number of people with health insurance and provided incentives for primary and preventive care.

Another factor behind the increase in the primary care workforce could be state laws that have expanded the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and primary care providers, she said.

Numbers may overestimate available care

The gap between rural and urban areas could be even wider than this study suggests, Ada D. Stewart, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview. Many nurse practitioners and physician assistants don’t actually practice primary care, but instead assist physicians in other specialties such as orthopedics or general surgery.

“They are part of a team and I don’t want to diminish that at all, but especially when we talk about infant and maternal mortality, family physicians need to be there themselves providing primary care,” she said. “We’re there in hospitals and emergency rooms, and not just taking care of diabetes and hypertension.”

In addition, the primary care workforce may have been reduced since the conclusion of the study period (Dec. 31, 2017) as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic forcing some primary care physicians into retirement, Dr. Stewart said.

Measures that could help reduce the disparity include a more robust system of teaching health centers in rural counties, higher reimbursement for primary care, a lower cost of medical education, and recruiting more people from rural areas to become physicians, Dr. Stewart said.

Telehealth can enhance health care in rural areas, but many people in rural areas lack internet or cellular service, or don’t have access to computers. “We don’t want to create another healthcare disparity,” she said.

And physicians can get to know their patients’ needs better in a face-to-face visit, she said. “Telehealth does have a place, but it does not replace that person-to-person visit.”

This study was funded by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Zhang and Dr. Stewart disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

The finding may provide some reassurance for those who have worried about a shortage of health care workers and whether they will be able to meet the nation’s growing burden of chronic diseases.

“Access to primary care doctors is critical to population health and to reduce health care disparities in this country,” said Donglan Zhang, PhD, an assistant professor of public health at the University of Georgia, Athens.

However, many counties remain underserved, Dr. Zhang said in an interview. The need for primary care in the United States is increasing not only with population growth but because the population is aging.

Dr. Zhang and colleagues published the finding in JAMA Network Open.

Many previous reports have warned of a shortage in primary care providers. To examine recent trends in the primary care workforce, Dr. Zhang and colleagues obtained data on all the primary care clinicians registered with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services from 2009 to 2017.

For the study, the researchers included general practitioners, family physicians and internists without subspecialties, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. They then compared the number of providers with the number of residents in each county as recorded by the US Census, using urban or rural classifications for each county from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration defines a primary care “shortage” as fewer than 1 primary care practitioner per 3,500 people, the researchers focused on this ratio. They found that the number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants was increasing much faster than the number of primary care physicians. This was true especially in rural areas, but the percentage increase for both nurse practitioners and physician assistants was lower in rural areas versus urban.

The researchers also found that there were more primary care physicians per capita in counties with higher household incomes, a higher proportion of Asian residents, and a higher proportion of college graduates.

They didn’t find a significant association between the median household income and per capita number of nurse practitioners.

They found that counties with a higher proportion of Black and Asian residents had a higher number of nurse practitioners per capita. But they found an opposite association between the proportion of Black residents and the number of physician assistants per capita.

The authors hypothesized that health care reform, particularly the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, may explain the recent increase in the primary care workforce. The legislation expanded the number of people with health insurance and provided incentives for primary and preventive care.

Another factor behind the increase in the primary care workforce could be state laws that have expanded the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and primary care providers, she said.

Numbers may overestimate available care

The gap between rural and urban areas could be even wider than this study suggests, Ada D. Stewart, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview. Many nurse practitioners and physician assistants don’t actually practice primary care, but instead assist physicians in other specialties such as orthopedics or general surgery.

“They are part of a team and I don’t want to diminish that at all, but especially when we talk about infant and maternal mortality, family physicians need to be there themselves providing primary care,” she said. “We’re there in hospitals and emergency rooms, and not just taking care of diabetes and hypertension.”

In addition, the primary care workforce may have been reduced since the conclusion of the study period (Dec. 31, 2017) as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic forcing some primary care physicians into retirement, Dr. Stewart said.

Measures that could help reduce the disparity include a more robust system of teaching health centers in rural counties, higher reimbursement for primary care, a lower cost of medical education, and recruiting more people from rural areas to become physicians, Dr. Stewart said.

Telehealth can enhance health care in rural areas, but many people in rural areas lack internet or cellular service, or don’t have access to computers. “We don’t want to create another healthcare disparity,” she said.

And physicians can get to know their patients’ needs better in a face-to-face visit, she said. “Telehealth does have a place, but it does not replace that person-to-person visit.”

This study was funded by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Zhang and Dr. Stewart disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

researchers say.

The finding may provide some reassurance for those who have worried about a shortage of health care workers and whether they will be able to meet the nation’s growing burden of chronic diseases.

“Access to primary care doctors is critical to population health and to reduce health care disparities in this country,” said Donglan Zhang, PhD, an assistant professor of public health at the University of Georgia, Athens.

However, many counties remain underserved, Dr. Zhang said in an interview. The need for primary care in the United States is increasing not only with population growth but because the population is aging.

Dr. Zhang and colleagues published the finding in JAMA Network Open.

Many previous reports have warned of a shortage in primary care providers. To examine recent trends in the primary care workforce, Dr. Zhang and colleagues obtained data on all the primary care clinicians registered with the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services from 2009 to 2017.

For the study, the researchers included general practitioners, family physicians and internists without subspecialties, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. They then compared the number of providers with the number of residents in each county as recorded by the US Census, using urban or rural classifications for each county from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Because the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration defines a primary care “shortage” as fewer than 1 primary care practitioner per 3,500 people, the researchers focused on this ratio. They found that the number of nurse practitioners and physician assistants was increasing much faster than the number of primary care physicians. This was true especially in rural areas, but the percentage increase for both nurse practitioners and physician assistants was lower in rural areas versus urban.

The researchers also found that there were more primary care physicians per capita in counties with higher household incomes, a higher proportion of Asian residents, and a higher proportion of college graduates.

They didn’t find a significant association between the median household income and per capita number of nurse practitioners.

They found that counties with a higher proportion of Black and Asian residents had a higher number of nurse practitioners per capita. But they found an opposite association between the proportion of Black residents and the number of physician assistants per capita.

The authors hypothesized that health care reform, particularly the passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, may explain the recent increase in the primary care workforce. The legislation expanded the number of people with health insurance and provided incentives for primary and preventive care.

Another factor behind the increase in the primary care workforce could be state laws that have expanded the scope of practice for nurse practitioners and primary care providers, she said.

Numbers may overestimate available care

The gap between rural and urban areas could be even wider than this study suggests, Ada D. Stewart, MD, president of the American Academy of Family Physicians, said in an interview. Many nurse practitioners and physician assistants don’t actually practice primary care, but instead assist physicians in other specialties such as orthopedics or general surgery.

“They are part of a team and I don’t want to diminish that at all, but especially when we talk about infant and maternal mortality, family physicians need to be there themselves providing primary care,” she said. “We’re there in hospitals and emergency rooms, and not just taking care of diabetes and hypertension.”

In addition, the primary care workforce may have been reduced since the conclusion of the study period (Dec. 31, 2017) as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic forcing some primary care physicians into retirement, Dr. Stewart said.

Measures that could help reduce the disparity include a more robust system of teaching health centers in rural counties, higher reimbursement for primary care, a lower cost of medical education, and recruiting more people from rural areas to become physicians, Dr. Stewart said.

Telehealth can enhance health care in rural areas, but many people in rural areas lack internet or cellular service, or don’t have access to computers. “We don’t want to create another healthcare disparity,” she said.

And physicians can get to know their patients’ needs better in a face-to-face visit, she said. “Telehealth does have a place, but it does not replace that person-to-person visit.”

This study was funded by National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities. Dr. Zhang and Dr. Stewart disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Tocilizumab stumbles as COVID-19 treatment, narrow role possible

Tocilizumab (Actemra/RoActemra) was not found to have any clear role as a treatment for COVID-19 in four new studies.

Three randomized controlled trials showed that the drug either had no benefit or only a modest one, contradicting a large retrospective study that had hinted at a more robust effect.

“This is not a blockbuster,” said David Cennimo, MD, an infectious disease expert at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey. “This is not something that’s going to revolutionize our treatment of COVID-19.”

But some researchers still regard these studies as showing evidence that the drug benefits certain patients with severe inflammation.

The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 includes elevated levels of the cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). In some patients, this response becomes a nonspecific inflammation, a “cytokine storm,” involving edema and inflammatory cell infiltration in the lungs. These cases are among the most severe.

Dexamethasone has proved effective in controlling this inflammation in some patients. Researchers have theorized that a more targeted suppression of IL-6 could be even more effective or work in cases that don’t respond to dexamethasone.

A recombinant monoclonal antibody, tocilizumab blocks IL-6 receptors. It is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with rheumatologic disorders and cytokine release syndrome induced by chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy.

Current National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines recommend against the use of tocilizumab as a treatment for COVID-19, despite earlier observational studies that suggested the drug might help patients with moderate to severe disease. Controlled trials were lacking until now.

The most hopeful results in this batch came from the CORIMUNO-19 platform of open-label, randomized controlled trials of immune modulatory treatments for moderate or severe COVID-19 in France.

Published in JAMA Internal Medicine , the trial recruited patients from nine French hospitals. Patients were eligible if they required at least 3 L/min of oxygen without ventilation or admission to the intensive care unit.

The investigators randomly assigned 64 patients to receive tocilizumab 8 mg/kg body weight intravenously plus usual care and 67 patients to usual care alone. Usual care included antibiotic agents, antiviral agents, corticosteroids, vasopressor support, and anticoagulants.

After 4 days, the investigators scored patients on the World Health Organization 10-point Clinical Progression Scale. Twelve of the patients who received tocilizumab scored higher than 5 vs 19 of the patients in the usual care group, with higher scores indicating clinical deterioration.

After 14 days, 24% of the patients taking tocilizumab required either noninvasive ventilation or mechanical ventilation or had died, vs 36% in the usual care group (median posterior hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 90% credible interval, 0.33 – 1.00).

“We reduced the risk of dying or requiring mechanical ventilation, so for me, the study was positive,” said Olivier Hermine, MD, PhD, a professor of hematology at Paris Descartes University in Paris, France.

However, there was no difference in mortality at 28 days. Hermine hopes to have longer-term outcomes soon, he told Medscape Medical News.

A second randomized controlled trial, also published in JAMA Internal Medicine , provided less hope. In this RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 Study Group trial, conducted at 24 Italian centers, patients were enrolled if their partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ratios were between 200 and 300 mm Hg and if their inflammatory phenotypes were defined by fever and elevated C-reactive protein level.

The investigators randomly assigned 60 patients to receive tocilizumab 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg within 8 hours of randomization, followed by a second dose after 12 hours. They assigned 66 patients to a control group that received supportive care until clinical worsening, at which point patients could receive tocilizumab as a rescue therapy.

Of the patients who received tocilizumab, 28.3% showed clinical worsening within 14 days, compared to 27.0% in the control group (rate ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.59 – 1.86). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of the proportion admitted to intensive care. The researchers stopped the trial prematurely because tocilizumab did not seem to be making a difference.

The BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial was conducted at seven Boston hospitals. The results, which were published in The New England Journal of Medicine, were also discouraging.

In that trial, enrolled patients met two sets of parameters. First, the patients had at least one of the following signs: C-reactive protein level higher than 50 mg/L, ferritin level higher than 500 ng/mL, D-dimer level higher than 1000 ng/mL, or a lactate dehydrogenase level higher than 250 U/L. Second, the patients had to have at least two of the following signs: body temperature >38° C, pulmonary infiltrates, or the need for supplemental oxygen to maintain an oxygen saturation greater than 92%.

The investigators randomly assigned 161 patients to receive intravenous tocilizumab 8 mg/kg up to 800 mg and 81 to receive a placebo.

They didn’t find a statistically significant difference between the groups. The hazard ratio for intubation or death in the tocilizumab group as compared with the placebo group was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.38 – 1.81; P = .64). The hazard ratio for disease worsening was 1.11 (95% CI, 0.59 – 2.10; P = .73). At 14 days, the conditions of 18.0% of the patients who received tocilizumab and 14.9% of the patients who received the placebo worsened.

In contrast to these randomized trials, STOP-COVID, a retrospective analysis of 3924 patients, also published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that the risk for death was lower for patients treated with tocilizumab compared with those not treated with tocilizumab (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.56 – 0.92) over a median follow-up period of 27 days.

Also on the bright side, none of the new studies showed significant adverse reactions to tocilizumab.

More randomized clinical trials are underway. In press releases announcing topline data, Roche reported mostly negative results in its phase 3 COVACTA trial but noted a 44% reduction in the risk for progression to death or ventilation in its phase 3 IMPACTA trial. Roche did not comment on the ethnicity of its COVACTA patients; it said IMPACTA enrolled a majority of Hispanic patients and included large representations of Native American and Black patients.

Results don’t support routine use

Commenting on the new studies, editorialists in both JAMA Internal Medicine and The New England Journal of Medicine concluded that the tocilizumab results were not strong enough to support routine use.

“My take-home point from looking at all of these together is that, even if it does help, it’s most likely in a small subset of the population and/or a small effect,” Cennimo told Medscape Medical News.

But the NIH recommendation against tocilizumab goes too far, argued Cristina Mussini, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy, who is a coauthor of a cohort study of tocilizumab and served on the CORIMUNO-19 Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

“I really think it’s too early to recommend against it because at least two clinical trials showed protection against mechanical ventilation and death,” she said.

She prescribes tocilizumab for patients who have not been helped by dexamethasone. “It’s just a rescue drug,” she told Medscape Medical News. “It’s not something you use for everybody, but it’s the only weapon we have now when the patient is really going to the intensive care unit.”

The BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial was funded by Genentech/Roche. Genentech/Roche provided the drug for the CORIMUNO and RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 trials. The STOP-COVID study was supported by grants from the NIH and by the Frankel Cardiovascular Center COVID-19: Impact Research Ignitor. Cennimo, Hermine, and Mussini have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tocilizumab (Actemra/RoActemra) was not found to have any clear role as a treatment for COVID-19 in four new studies.

Three randomized controlled trials showed that the drug either had no benefit or only a modest one, contradicting a large retrospective study that had hinted at a more robust effect.

“This is not a blockbuster,” said David Cennimo, MD, an infectious disease expert at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey. “This is not something that’s going to revolutionize our treatment of COVID-19.”

But some researchers still regard these studies as showing evidence that the drug benefits certain patients with severe inflammation.

The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 includes elevated levels of the cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). In some patients, this response becomes a nonspecific inflammation, a “cytokine storm,” involving edema and inflammatory cell infiltration in the lungs. These cases are among the most severe.

Dexamethasone has proved effective in controlling this inflammation in some patients. Researchers have theorized that a more targeted suppression of IL-6 could be even more effective or work in cases that don’t respond to dexamethasone.

A recombinant monoclonal antibody, tocilizumab blocks IL-6 receptors. It is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with rheumatologic disorders and cytokine release syndrome induced by chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy.

Current National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines recommend against the use of tocilizumab as a treatment for COVID-19, despite earlier observational studies that suggested the drug might help patients with moderate to severe disease. Controlled trials were lacking until now.

The most hopeful results in this batch came from the CORIMUNO-19 platform of open-label, randomized controlled trials of immune modulatory treatments for moderate or severe COVID-19 in France.

Published in JAMA Internal Medicine , the trial recruited patients from nine French hospitals. Patients were eligible if they required at least 3 L/min of oxygen without ventilation or admission to the intensive care unit.

The investigators randomly assigned 64 patients to receive tocilizumab 8 mg/kg body weight intravenously plus usual care and 67 patients to usual care alone. Usual care included antibiotic agents, antiviral agents, corticosteroids, vasopressor support, and anticoagulants.

After 4 days, the investigators scored patients on the World Health Organization 10-point Clinical Progression Scale. Twelve of the patients who received tocilizumab scored higher than 5 vs 19 of the patients in the usual care group, with higher scores indicating clinical deterioration.

After 14 days, 24% of the patients taking tocilizumab required either noninvasive ventilation or mechanical ventilation or had died, vs 36% in the usual care group (median posterior hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 90% credible interval, 0.33 – 1.00).

“We reduced the risk of dying or requiring mechanical ventilation, so for me, the study was positive,” said Olivier Hermine, MD, PhD, a professor of hematology at Paris Descartes University in Paris, France.

However, there was no difference in mortality at 28 days. Hermine hopes to have longer-term outcomes soon, he told Medscape Medical News.

A second randomized controlled trial, also published in JAMA Internal Medicine , provided less hope. In this RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 Study Group trial, conducted at 24 Italian centers, patients were enrolled if their partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ratios were between 200 and 300 mm Hg and if their inflammatory phenotypes were defined by fever and elevated C-reactive protein level.

The investigators randomly assigned 60 patients to receive tocilizumab 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg within 8 hours of randomization, followed by a second dose after 12 hours. They assigned 66 patients to a control group that received supportive care until clinical worsening, at which point patients could receive tocilizumab as a rescue therapy.

Of the patients who received tocilizumab, 28.3% showed clinical worsening within 14 days, compared to 27.0% in the control group (rate ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.59 – 1.86). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of the proportion admitted to intensive care. The researchers stopped the trial prematurely because tocilizumab did not seem to be making a difference.

The BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial was conducted at seven Boston hospitals. The results, which were published in The New England Journal of Medicine, were also discouraging.

In that trial, enrolled patients met two sets of parameters. First, the patients had at least one of the following signs: C-reactive protein level higher than 50 mg/L, ferritin level higher than 500 ng/mL, D-dimer level higher than 1000 ng/mL, or a lactate dehydrogenase level higher than 250 U/L. Second, the patients had to have at least two of the following signs: body temperature >38° C, pulmonary infiltrates, or the need for supplemental oxygen to maintain an oxygen saturation greater than 92%.

The investigators randomly assigned 161 patients to receive intravenous tocilizumab 8 mg/kg up to 800 mg and 81 to receive a placebo.

They didn’t find a statistically significant difference between the groups. The hazard ratio for intubation or death in the tocilizumab group as compared with the placebo group was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.38 – 1.81; P = .64). The hazard ratio for disease worsening was 1.11 (95% CI, 0.59 – 2.10; P = .73). At 14 days, the conditions of 18.0% of the patients who received tocilizumab and 14.9% of the patients who received the placebo worsened.

In contrast to these randomized trials, STOP-COVID, a retrospective analysis of 3924 patients, also published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that the risk for death was lower for patients treated with tocilizumab compared with those not treated with tocilizumab (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.56 – 0.92) over a median follow-up period of 27 days.

Also on the bright side, none of the new studies showed significant adverse reactions to tocilizumab.

More randomized clinical trials are underway. In press releases announcing topline data, Roche reported mostly negative results in its phase 3 COVACTA trial but noted a 44% reduction in the risk for progression to death or ventilation in its phase 3 IMPACTA trial. Roche did not comment on the ethnicity of its COVACTA patients; it said IMPACTA enrolled a majority of Hispanic patients and included large representations of Native American and Black patients.

Results don’t support routine use

Commenting on the new studies, editorialists in both JAMA Internal Medicine and The New England Journal of Medicine concluded that the tocilizumab results were not strong enough to support routine use.

“My take-home point from looking at all of these together is that, even if it does help, it’s most likely in a small subset of the population and/or a small effect,” Cennimo told Medscape Medical News.

But the NIH recommendation against tocilizumab goes too far, argued Cristina Mussini, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy, who is a coauthor of a cohort study of tocilizumab and served on the CORIMUNO-19 Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

“I really think it’s too early to recommend against it because at least two clinical trials showed protection against mechanical ventilation and death,” she said.

She prescribes tocilizumab for patients who have not been helped by dexamethasone. “It’s just a rescue drug,” she told Medscape Medical News. “It’s not something you use for everybody, but it’s the only weapon we have now when the patient is really going to the intensive care unit.”

The BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial was funded by Genentech/Roche. Genentech/Roche provided the drug for the CORIMUNO and RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 trials. The STOP-COVID study was supported by grants from the NIH and by the Frankel Cardiovascular Center COVID-19: Impact Research Ignitor. Cennimo, Hermine, and Mussini have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tocilizumab (Actemra/RoActemra) was not found to have any clear role as a treatment for COVID-19 in four new studies.

Three randomized controlled trials showed that the drug either had no benefit or only a modest one, contradicting a large retrospective study that had hinted at a more robust effect.

“This is not a blockbuster,” said David Cennimo, MD, an infectious disease expert at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, Newark, New Jersey. “This is not something that’s going to revolutionize our treatment of COVID-19.”

But some researchers still regard these studies as showing evidence that the drug benefits certain patients with severe inflammation.

The immune response to SARS-CoV-2 includes elevated levels of the cytokine interleukin-6 (IL-6). In some patients, this response becomes a nonspecific inflammation, a “cytokine storm,” involving edema and inflammatory cell infiltration in the lungs. These cases are among the most severe.

Dexamethasone has proved effective in controlling this inflammation in some patients. Researchers have theorized that a more targeted suppression of IL-6 could be even more effective or work in cases that don’t respond to dexamethasone.

A recombinant monoclonal antibody, tocilizumab blocks IL-6 receptors. It is approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for use in patients with rheumatologic disorders and cytokine release syndrome induced by chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy.

Current National Institutes of Health (NIH) guidelines recommend against the use of tocilizumab as a treatment for COVID-19, despite earlier observational studies that suggested the drug might help patients with moderate to severe disease. Controlled trials were lacking until now.

The most hopeful results in this batch came from the CORIMUNO-19 platform of open-label, randomized controlled trials of immune modulatory treatments for moderate or severe COVID-19 in France.

Published in JAMA Internal Medicine , the trial recruited patients from nine French hospitals. Patients were eligible if they required at least 3 L/min of oxygen without ventilation or admission to the intensive care unit.

The investigators randomly assigned 64 patients to receive tocilizumab 8 mg/kg body weight intravenously plus usual care and 67 patients to usual care alone. Usual care included antibiotic agents, antiviral agents, corticosteroids, vasopressor support, and anticoagulants.

After 4 days, the investigators scored patients on the World Health Organization 10-point Clinical Progression Scale. Twelve of the patients who received tocilizumab scored higher than 5 vs 19 of the patients in the usual care group, with higher scores indicating clinical deterioration.

After 14 days, 24% of the patients taking tocilizumab required either noninvasive ventilation or mechanical ventilation or had died, vs 36% in the usual care group (median posterior hazard ratio [HR], 0.58; 90% credible interval, 0.33 – 1.00).

“We reduced the risk of dying or requiring mechanical ventilation, so for me, the study was positive,” said Olivier Hermine, MD, PhD, a professor of hematology at Paris Descartes University in Paris, France.

However, there was no difference in mortality at 28 days. Hermine hopes to have longer-term outcomes soon, he told Medscape Medical News.

A second randomized controlled trial, also published in JAMA Internal Medicine , provided less hope. In this RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 Study Group trial, conducted at 24 Italian centers, patients were enrolled if their partial pressure of arterial oxygen to fraction of inspired oxygen (PaO2/FiO2) ratios were between 200 and 300 mm Hg and if their inflammatory phenotypes were defined by fever and elevated C-reactive protein level.

The investigators randomly assigned 60 patients to receive tocilizumab 8 mg/kg up to a maximum of 800 mg within 8 hours of randomization, followed by a second dose after 12 hours. They assigned 66 patients to a control group that received supportive care until clinical worsening, at which point patients could receive tocilizumab as a rescue therapy.

Of the patients who received tocilizumab, 28.3% showed clinical worsening within 14 days, compared to 27.0% in the control group (rate ratio, 1.05; 95% CI, 0.59 – 1.86). There was no significant difference between the groups in terms of the proportion admitted to intensive care. The researchers stopped the trial prematurely because tocilizumab did not seem to be making a difference.

The BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial was conducted at seven Boston hospitals. The results, which were published in The New England Journal of Medicine, were also discouraging.

In that trial, enrolled patients met two sets of parameters. First, the patients had at least one of the following signs: C-reactive protein level higher than 50 mg/L, ferritin level higher than 500 ng/mL, D-dimer level higher than 1000 ng/mL, or a lactate dehydrogenase level higher than 250 U/L. Second, the patients had to have at least two of the following signs: body temperature >38° C, pulmonary infiltrates, or the need for supplemental oxygen to maintain an oxygen saturation greater than 92%.

The investigators randomly assigned 161 patients to receive intravenous tocilizumab 8 mg/kg up to 800 mg and 81 to receive a placebo.

They didn’t find a statistically significant difference between the groups. The hazard ratio for intubation or death in the tocilizumab group as compared with the placebo group was 0.83 (95% CI, 0.38 – 1.81; P = .64). The hazard ratio for disease worsening was 1.11 (95% CI, 0.59 – 2.10; P = .73). At 14 days, the conditions of 18.0% of the patients who received tocilizumab and 14.9% of the patients who received the placebo worsened.

In contrast to these randomized trials, STOP-COVID, a retrospective analysis of 3924 patients, also published in JAMA Internal Medicine, found that the risk for death was lower for patients treated with tocilizumab compared with those not treated with tocilizumab (HR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.56 – 0.92) over a median follow-up period of 27 days.

Also on the bright side, none of the new studies showed significant adverse reactions to tocilizumab.

More randomized clinical trials are underway. In press releases announcing topline data, Roche reported mostly negative results in its phase 3 COVACTA trial but noted a 44% reduction in the risk for progression to death or ventilation in its phase 3 IMPACTA trial. Roche did not comment on the ethnicity of its COVACTA patients; it said IMPACTA enrolled a majority of Hispanic patients and included large representations of Native American and Black patients.

Results don’t support routine use

Commenting on the new studies, editorialists in both JAMA Internal Medicine and The New England Journal of Medicine concluded that the tocilizumab results were not strong enough to support routine use.

“My take-home point from looking at all of these together is that, even if it does help, it’s most likely in a small subset of the population and/or a small effect,” Cennimo told Medscape Medical News.

But the NIH recommendation against tocilizumab goes too far, argued Cristina Mussini, MD, a professor of infectious diseases at the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia in Italy, who is a coauthor of a cohort study of tocilizumab and served on the CORIMUNO-19 Data Safety and Monitoring Board.

“I really think it’s too early to recommend against it because at least two clinical trials showed protection against mechanical ventilation and death,” she said.

She prescribes tocilizumab for patients who have not been helped by dexamethasone. “It’s just a rescue drug,” she told Medscape Medical News. “It’s not something you use for everybody, but it’s the only weapon we have now when the patient is really going to the intensive care unit.”

The BACC Bay Tocilizumab Trial was funded by Genentech/Roche. Genentech/Roche provided the drug for the CORIMUNO and RCT-TCZ-COVID-19 trials. The STOP-COVID study was supported by grants from the NIH and by the Frankel Cardiovascular Center COVID-19: Impact Research Ignitor. Cennimo, Hermine, and Mussini have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

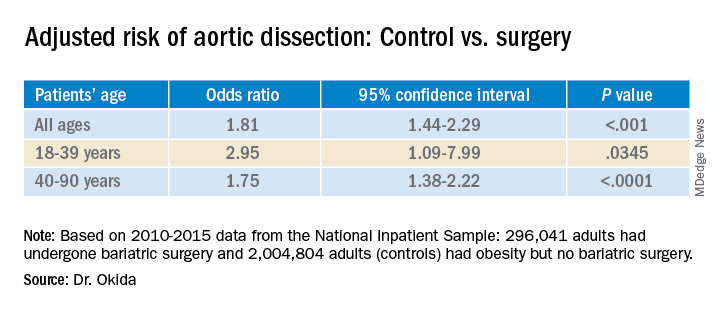

Bariatric surgery tied to lower aortic dissection risk

The finding is the latest in a series of benefits researchers have linked to the surgery, not all of which appear to directly result from weight loss.

“It has an incredible impact on hyperlipidemia and hypertension,” said Luis Felipe Okida, MD, from Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “Those are the main risk factors for aortic dissection.”

He presented the finding at the virtual American Congress of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020. The study was also published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Although uncommon, acute aortic dissection proves fatal to half the people it strikes if patients do not receive treatment within 72 hours, Dr. Okida said in an interview.

To learn whether there is an association between bariatric surgery and risk for aortic dissection, Dr. Okida and colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2010 to 2015. The NIS comprises about 20% of hospital inpatient admissions in the United States.

Among the patients in the sample, 296,041 adults had undergone bariatric surgery, and 2,004,804 adults had obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2) but had never undergone bariatric surgery. This latter group represented the control group.

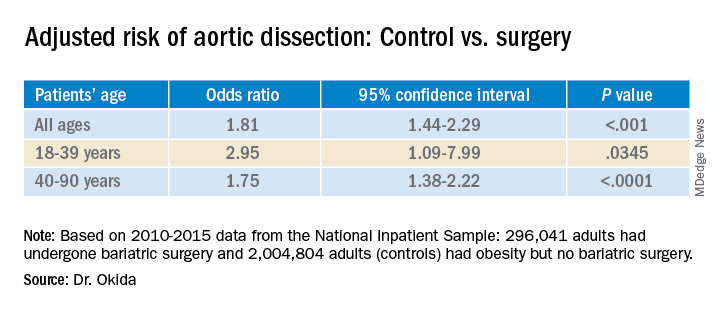

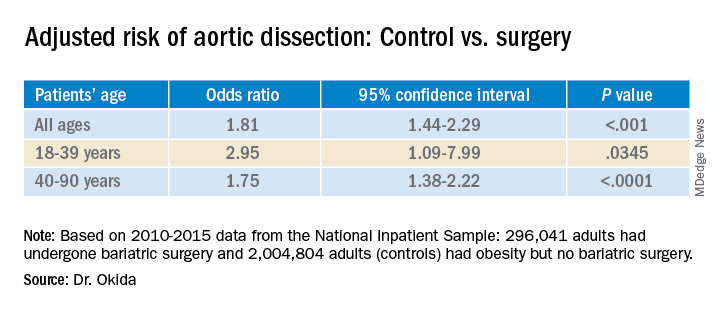

Among the control group, 1,411 patients (.070%) experienced aortic dissection; among the bariatric surgery group, 94 patients (0.032%) experienced aortic dissection. This was a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

The groups differed significantly in many ways. The mean age of the patients in the control group was 54.4 years, which was a mean of 2.5 years older than the bariatric surgery group. Additionally, the control group included a higher percentage of women and a lower percentage of White persons.

Those in the control group were also more likely to have a history of tobacco use, hypertension (64.2% vs. 48.9% in the surgery group), hyperlipidemia (32.7% vs. 18.3%), diabetes, aortic aneurysm (20.6% vs. 12.0%), and bicuspid aortic valves but were less likely to have Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

A multivariate analysis showed that gender, age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome were associated with an increased risk for aortic dissection. Diabetes was associated with a lower risk. All of these findings had previously been reported in the literature, Dr. Okida said, but the reasons for the negative association with diabetes is not well understood.

The association between the surgery and aortic dissection applied to younger patients as well as older ones.

“In elderly patients, the main risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension, and in younger patients, below 40 years old, the main risk factors are diseases of the collagen and diseases of the aorta,” said Dr. Okida during his presentation. “But these younger patients still have a high prevalence of hypertension, and that’s why bariatric surgery is beneficial.”

Although the finding regarding risk for aortic dissection supports the value of bariatric surgery, it does not in itself provide justification for undergoing the procedure. “It’s not even one of the comorbidities that insurance companies would recognize as key in approving this procedure,” said senior author Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, also from the Cleveland Clinic Florida.

“I don’t think a physician would ever recommend this procedure specifically to avoid aortic dissection,” he said in an interview. “It’s sort of an extended benefit.”

The study raises interesting questions about the effects of the surgery, said Shanu Kothari, MD, president-elect of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“We’ve known for a long time that patients with chronic obesity who undergo weight-loss surgery live longer than those who don’t,” he said in an interview. “They have less cardiovascular disease and cancer. Is this one more reason that they live longer?”

Bariatric surgery produces benefits for people with diabetes the day after the surgery, long before patients lose weight as a result of the procedure, Dr. Kothari said.

The effects on metabolism are complex, he added. Besides caloric restriction, they include changes in bile salt absorption and the gut microbiome, which in turn can affect hormones and inflammation.

A key question is how long after the surgery the risk for aortic dissection starts to decline, said Dr. Kothari.

The study could not answer such questions, and Dr. Okida could not find any previous studies that explored the association. He also couldn’t find any study that examined whether weight loss by other means might also reduce the risk for aortic dissection.

Dr. Okida, Dr. Lo Menzo, and Dr. Kothari disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The finding is the latest in a series of benefits researchers have linked to the surgery, not all of which appear to directly result from weight loss.

“It has an incredible impact on hyperlipidemia and hypertension,” said Luis Felipe Okida, MD, from Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “Those are the main risk factors for aortic dissection.”

He presented the finding at the virtual American Congress of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020. The study was also published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Although uncommon, acute aortic dissection proves fatal to half the people it strikes if patients do not receive treatment within 72 hours, Dr. Okida said in an interview.

To learn whether there is an association between bariatric surgery and risk for aortic dissection, Dr. Okida and colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2010 to 2015. The NIS comprises about 20% of hospital inpatient admissions in the United States.

Among the patients in the sample, 296,041 adults had undergone bariatric surgery, and 2,004,804 adults had obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2) but had never undergone bariatric surgery. This latter group represented the control group.

Among the control group, 1,411 patients (.070%) experienced aortic dissection; among the bariatric surgery group, 94 patients (0.032%) experienced aortic dissection. This was a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

The groups differed significantly in many ways. The mean age of the patients in the control group was 54.4 years, which was a mean of 2.5 years older than the bariatric surgery group. Additionally, the control group included a higher percentage of women and a lower percentage of White persons.

Those in the control group were also more likely to have a history of tobacco use, hypertension (64.2% vs. 48.9% in the surgery group), hyperlipidemia (32.7% vs. 18.3%), diabetes, aortic aneurysm (20.6% vs. 12.0%), and bicuspid aortic valves but were less likely to have Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

A multivariate analysis showed that gender, age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome were associated with an increased risk for aortic dissection. Diabetes was associated with a lower risk. All of these findings had previously been reported in the literature, Dr. Okida said, but the reasons for the negative association with diabetes is not well understood.

The association between the surgery and aortic dissection applied to younger patients as well as older ones.

“In elderly patients, the main risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension, and in younger patients, below 40 years old, the main risk factors are diseases of the collagen and diseases of the aorta,” said Dr. Okida during his presentation. “But these younger patients still have a high prevalence of hypertension, and that’s why bariatric surgery is beneficial.”

Although the finding regarding risk for aortic dissection supports the value of bariatric surgery, it does not in itself provide justification for undergoing the procedure. “It’s not even one of the comorbidities that insurance companies would recognize as key in approving this procedure,” said senior author Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, also from the Cleveland Clinic Florida.

“I don’t think a physician would ever recommend this procedure specifically to avoid aortic dissection,” he said in an interview. “It’s sort of an extended benefit.”

The study raises interesting questions about the effects of the surgery, said Shanu Kothari, MD, president-elect of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“We’ve known for a long time that patients with chronic obesity who undergo weight-loss surgery live longer than those who don’t,” he said in an interview. “They have less cardiovascular disease and cancer. Is this one more reason that they live longer?”

Bariatric surgery produces benefits for people with diabetes the day after the surgery, long before patients lose weight as a result of the procedure, Dr. Kothari said.

The effects on metabolism are complex, he added. Besides caloric restriction, they include changes in bile salt absorption and the gut microbiome, which in turn can affect hormones and inflammation.

A key question is how long after the surgery the risk for aortic dissection starts to decline, said Dr. Kothari.

The study could not answer such questions, and Dr. Okida could not find any previous studies that explored the association. He also couldn’t find any study that examined whether weight loss by other means might also reduce the risk for aortic dissection.

Dr. Okida, Dr. Lo Menzo, and Dr. Kothari disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The finding is the latest in a series of benefits researchers have linked to the surgery, not all of which appear to directly result from weight loss.

“It has an incredible impact on hyperlipidemia and hypertension,” said Luis Felipe Okida, MD, from Cleveland Clinic Florida, Weston. “Those are the main risk factors for aortic dissection.”

He presented the finding at the virtual American Congress of Surgeons Clinical Congress 2020. The study was also published online in the Journal of the American College of Surgeons.

Although uncommon, acute aortic dissection proves fatal to half the people it strikes if patients do not receive treatment within 72 hours, Dr. Okida said in an interview.

To learn whether there is an association between bariatric surgery and risk for aortic dissection, Dr. Okida and colleagues analyzed data from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database from 2010 to 2015. The NIS comprises about 20% of hospital inpatient admissions in the United States.

Among the patients in the sample, 296,041 adults had undergone bariatric surgery, and 2,004,804 adults had obesity (body mass index ≥35 kg/m2) but had never undergone bariatric surgery. This latter group represented the control group.

Among the control group, 1,411 patients (.070%) experienced aortic dissection; among the bariatric surgery group, 94 patients (0.032%) experienced aortic dissection. This was a statistically significant difference (P < .0001).

The groups differed significantly in many ways. The mean age of the patients in the control group was 54.4 years, which was a mean of 2.5 years older than the bariatric surgery group. Additionally, the control group included a higher percentage of women and a lower percentage of White persons.

Those in the control group were also more likely to have a history of tobacco use, hypertension (64.2% vs. 48.9% in the surgery group), hyperlipidemia (32.7% vs. 18.3%), diabetes, aortic aneurysm (20.6% vs. 12.0%), and bicuspid aortic valves but were less likely to have Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome.

A multivariate analysis showed that gender, age, history of tobacco use, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and Marfan/Ehlers-Danlos syndrome were associated with an increased risk for aortic dissection. Diabetes was associated with a lower risk. All of these findings had previously been reported in the literature, Dr. Okida said, but the reasons for the negative association with diabetes is not well understood.

The association between the surgery and aortic dissection applied to younger patients as well as older ones.

“In elderly patients, the main risk factor for aortic dissection is hypertension, and in younger patients, below 40 years old, the main risk factors are diseases of the collagen and diseases of the aorta,” said Dr. Okida during his presentation. “But these younger patients still have a high prevalence of hypertension, and that’s why bariatric surgery is beneficial.”

Although the finding regarding risk for aortic dissection supports the value of bariatric surgery, it does not in itself provide justification for undergoing the procedure. “It’s not even one of the comorbidities that insurance companies would recognize as key in approving this procedure,” said senior author Emanuele Lo Menzo, MD, PhD, also from the Cleveland Clinic Florida.

“I don’t think a physician would ever recommend this procedure specifically to avoid aortic dissection,” he said in an interview. “It’s sort of an extended benefit.”

The study raises interesting questions about the effects of the surgery, said Shanu Kothari, MD, president-elect of the American Society for Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery.

“We’ve known for a long time that patients with chronic obesity who undergo weight-loss surgery live longer than those who don’t,” he said in an interview. “They have less cardiovascular disease and cancer. Is this one more reason that they live longer?”

Bariatric surgery produces benefits for people with diabetes the day after the surgery, long before patients lose weight as a result of the procedure, Dr. Kothari said.

The effects on metabolism are complex, he added. Besides caloric restriction, they include changes in bile salt absorption and the gut microbiome, which in turn can affect hormones and inflammation.

A key question is how long after the surgery the risk for aortic dissection starts to decline, said Dr. Kothari.

The study could not answer such questions, and Dr. Okida could not find any previous studies that explored the association. He also couldn’t find any study that examined whether weight loss by other means might also reduce the risk for aortic dissection.

Dr. Okida, Dr. Lo Menzo, and Dr. Kothari disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Fourteen-day sports hiatus recommended for children after COVID-19

Children should not return to sports for 14 days after exposure to COVID-19, and those with moderate symptoms should undergo an electrocardiogram before returning, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

said Susannah Briskin, MD, a pediatric sports medicine specialist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

“There has been emerging evidence about cases of myocarditis occurring in athletes, including athletes who are asymptomatic with COVID-19,” she said in an interview.

The update aligns the AAP recommendations with those from the American College of Cardiologists, she added.

Recent imaging studies have turned up signs of myocarditis in athletes recovering from mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 and have prompted calls for clearer guidelines about imaging studies and return to play.

Viral myocarditis poses a risk to athletes because it can lead to potentially fatal arrhythmias, Dr. Briskin said.

Although children benefit from participating in sports, these activities also put them at risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to others, the guidance noted.

To balance the risks and benefits, the academy proposed guidelines that vary depending on the severity of the presentation.

In the first category are patients with a severe presentation (hypotension, arrhythmias, need for intubation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, kidney or cardiac failure) or with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Clinicians should treat these patients as though they have myocarditis. Patients should be restricted from engaging in sports and other exercise for 3-6 months, the guidance stated.

The primary care physician and “appropriate pediatric medical subspecialist, preferably in consultation with a pediatric cardiologist,” should clear them before they return to activities. In examining patients for return to play, clinicians should focus on cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope, the guidance said.

In another category are patients with cardiac symptoms, those with concerning findings on examination, and those with moderate symptoms of COVID-19, including prolonged fever. These patients should undergo an ECG and possibly be referred to a pediatric cardiologist, the guidelines said. These symptoms must be absent for at least 14 days before these patients can return to sports, and the athletes should obtain clearance from their primary care physicians before they resume.

In a third category are patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who have had close contact with someone who was infected but who have not themselves experienced symptoms. These athletes should refrain from sports for at least 14 days, the guidelines said.

Children who don’t fall into any of these categories should not be tested for the virus or antibodies to it before participation in sports, the academy said.

The guidelines don’t vary depending on the sport. But the academy has issued separate guidance for parents and guardians to help them evaluate the risk for COVID-19 transmission by sport.

Athletes participating in “sports that have greater amount of contact time or proximity to people would be at higher risk for contracting COVID-19,” Dr. Briskin said. “But I think that’s all fairly common sense, given the recommendations for non–sport-related activity just in terms of social distancing and masking.”

The new guidance called on sports organizers to minimize contact by, for example, modifying drills and conditioning. It recommended that athletes wear masks except during vigorous exercise or when participating in water sports, as well as in other circumstances in which the mask could become a safety hazard.

They also recommended using handwashing stations or hand sanitizer, avoiding contact with shared surfaces, and avoiding small rooms and areas with poor ventilation.

Dr. Briskin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children should not return to sports for 14 days after exposure to COVID-19, and those with moderate symptoms should undergo an electrocardiogram before returning, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

said Susannah Briskin, MD, a pediatric sports medicine specialist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

“There has been emerging evidence about cases of myocarditis occurring in athletes, including athletes who are asymptomatic with COVID-19,” she said in an interview.

The update aligns the AAP recommendations with those from the American College of Cardiologists, she added.

Recent imaging studies have turned up signs of myocarditis in athletes recovering from mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 and have prompted calls for clearer guidelines about imaging studies and return to play.

Viral myocarditis poses a risk to athletes because it can lead to potentially fatal arrhythmias, Dr. Briskin said.

Although children benefit from participating in sports, these activities also put them at risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to others, the guidance noted.

To balance the risks and benefits, the academy proposed guidelines that vary depending on the severity of the presentation.

In the first category are patients with a severe presentation (hypotension, arrhythmias, need for intubation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, kidney or cardiac failure) or with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Clinicians should treat these patients as though they have myocarditis. Patients should be restricted from engaging in sports and other exercise for 3-6 months, the guidance stated.

The primary care physician and “appropriate pediatric medical subspecialist, preferably in consultation with a pediatric cardiologist,” should clear them before they return to activities. In examining patients for return to play, clinicians should focus on cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope, the guidance said.

In another category are patients with cardiac symptoms, those with concerning findings on examination, and those with moderate symptoms of COVID-19, including prolonged fever. These patients should undergo an ECG and possibly be referred to a pediatric cardiologist, the guidelines said. These symptoms must be absent for at least 14 days before these patients can return to sports, and the athletes should obtain clearance from their primary care physicians before they resume.

In a third category are patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who have had close contact with someone who was infected but who have not themselves experienced symptoms. These athletes should refrain from sports for at least 14 days, the guidelines said.

Children who don’t fall into any of these categories should not be tested for the virus or antibodies to it before participation in sports, the academy said.

The guidelines don’t vary depending on the sport. But the academy has issued separate guidance for parents and guardians to help them evaluate the risk for COVID-19 transmission by sport.

Athletes participating in “sports that have greater amount of contact time or proximity to people would be at higher risk for contracting COVID-19,” Dr. Briskin said. “But I think that’s all fairly common sense, given the recommendations for non–sport-related activity just in terms of social distancing and masking.”

The new guidance called on sports organizers to minimize contact by, for example, modifying drills and conditioning. It recommended that athletes wear masks except during vigorous exercise or when participating in water sports, as well as in other circumstances in which the mask could become a safety hazard.

They also recommended using handwashing stations or hand sanitizer, avoiding contact with shared surfaces, and avoiding small rooms and areas with poor ventilation.

Dr. Briskin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Children should not return to sports for 14 days after exposure to COVID-19, and those with moderate symptoms should undergo an electrocardiogram before returning, according to the American Academy of Pediatrics.

said Susannah Briskin, MD, a pediatric sports medicine specialist at Rainbow Babies and Children’s Hospital in Cleveland.

“There has been emerging evidence about cases of myocarditis occurring in athletes, including athletes who are asymptomatic with COVID-19,” she said in an interview.

The update aligns the AAP recommendations with those from the American College of Cardiologists, she added.

Recent imaging studies have turned up signs of myocarditis in athletes recovering from mild or asymptomatic cases of COVID-19 and have prompted calls for clearer guidelines about imaging studies and return to play.

Viral myocarditis poses a risk to athletes because it can lead to potentially fatal arrhythmias, Dr. Briskin said.

Although children benefit from participating in sports, these activities also put them at risk of contracting COVID-19 and spreading it to others, the guidance noted.

To balance the risks and benefits, the academy proposed guidelines that vary depending on the severity of the presentation.

In the first category are patients with a severe presentation (hypotension, arrhythmias, need for intubation or extracorporeal membrane oxygenation support, kidney or cardiac failure) or with multisystem inflammatory syndrome. Clinicians should treat these patients as though they have myocarditis. Patients should be restricted from engaging in sports and other exercise for 3-6 months, the guidance stated.

The primary care physician and “appropriate pediatric medical subspecialist, preferably in consultation with a pediatric cardiologist,” should clear them before they return to activities. In examining patients for return to play, clinicians should focus on cardiac symptoms, including chest pain, shortness of breath, fatigue, palpitations, or syncope, the guidance said.

In another category are patients with cardiac symptoms, those with concerning findings on examination, and those with moderate symptoms of COVID-19, including prolonged fever. These patients should undergo an ECG and possibly be referred to a pediatric cardiologist, the guidelines said. These symptoms must be absent for at least 14 days before these patients can return to sports, and the athletes should obtain clearance from their primary care physicians before they resume.

In a third category are patients who have been infected with SARS-CoV-2 or who have had close contact with someone who was infected but who have not themselves experienced symptoms. These athletes should refrain from sports for at least 14 days, the guidelines said.

Children who don’t fall into any of these categories should not be tested for the virus or antibodies to it before participation in sports, the academy said.

The guidelines don’t vary depending on the sport. But the academy has issued separate guidance for parents and guardians to help them evaluate the risk for COVID-19 transmission by sport.

Athletes participating in “sports that have greater amount of contact time or proximity to people would be at higher risk for contracting COVID-19,” Dr. Briskin said. “But I think that’s all fairly common sense, given the recommendations for non–sport-related activity just in terms of social distancing and masking.”

The new guidance called on sports organizers to minimize contact by, for example, modifying drills and conditioning. It recommended that athletes wear masks except during vigorous exercise or when participating in water sports, as well as in other circumstances in which the mask could become a safety hazard.

They also recommended using handwashing stations or hand sanitizer, avoiding contact with shared surfaces, and avoiding small rooms and areas with poor ventilation.

Dr. Briskin disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Real-world safety, efficacy found for fecal transplants

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) appears safe and effective as a treatment for most Clostridioides difficile infections as it is currently being administered, researchers say.

“We actually didn’t see any infections that were definitely transmissible via fecal transplant,” Colleen Kelly, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I., said in an interview.

The findings, published online Oct. 1 in the journal Gastroenterology, come from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) NIH-funded FMT National Registry and could allay concerns about a treatment that has yet to gain full approval by the Food and Drug Administration, despite successful clinical trials.

C. diff infections are common and increasing in the United States, often can’t be cured with conventional treatments such as antibiotics, and can be deadly.

Transplanting fecal matter from a donor to the patient appears to work by restoring beneficial microorganisms to the patient’s gut. The procedure is also under investigation for a wide range of other ailments, from irritable bowel syndrome to mood disorders.

But much remains unknown. Researchers have counted a thousand bacterial species along with viruses, bacteriophages, archaea, and fungi in the human gut that interact in complex ways, not all of them beneficial.

The FDA has not enforced regulations that would prohibit the procedure, but in March, it warned about infections with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Shiga toxin–producing E. coli following fecal transplants.

As a result of these reports, and the theoretical risk of spreading SARS-CoV-2, OpenBiome, the largest stool bank in the United States, has suspended shipments except for emergency orders, and asked clinicians to quarantine any of its products they already have on hand.

In the meantime, long-term effects of the treatment have not been well documented. And clinical trials have excluded patients who might benefit, such as those who have been immunocompromised or have inflammatory bowel disease.

National registry follows patients outside clinical trials

To better understand how patients fare outside these trials, AGA and other organizations developed a national registry, funded by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The current report summarizes results on 259 patients enrolled between Dec. 5, 2017, and Sept. 2, 2019 at 20 sites.

At baseline, 44% of these patients suffered moderate and 36% mild C. diff infections. The duration of the diagnosis ranged from less than 1 week to 9 years, with a median duration of 20 weeks. They ranged from 1 to 15 episodes with a mean of 3.5.

Almost all had received vancomycin, and 62% had at least two courses. About 40% had received metronidazole and 28% had received fidaxomicin.

Almost all participants received stool from an unknown donor, mostly from stool banks, with OpenBiome accounting for 67%. About 85% of the transplants were administered through colonoscopy and 6% by upper endoscopy.

Out of 222 patients who returned for a 1-month follow-up, 90% met the investigators’ definition of cure: resolution of diarrhea without need for further anti–C. diff therapy. About 98% received only one transplant. An intent to treat analysis produced a cure rate of 86%.

Results were good in patients with comorbidities, including 12% who had irritable bowel syndrome, 9% who had ulcerative colitis, and 7% who had Crohn’s disease, Dr. Kelly said. “I hope everybody sees the importance of it. In these patients that are more complicated, who may have underlying comorbidities, who may not have been in the clinical trials, it looks effective in that group, and also incredibly safe.”

She added that the risk of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 is minor. “I think it would be a very, very unlikely way for someone to get a respiratory pathogen.”

Of the 112 participants who were cured at 1 month and returned for follow-up after 6 months, 4 developed recurrent C. diff infection. Eleven patients who were not cured in the first month returned after 6 months. Of these, seven were reported cured at this later follow-up.

Three complications occurred as result of the procedure: one colonoscopic perforation and two episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding.

About 45% of participants reported at least one symptom, with diarrhea not related to C. difficile the most common, followed by abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation.

Eleven patients suffered infections, including two which the investigators thought might be related to the procedure: Bacteroides fragilis in one participant with severe diarrhea, and enteropathogenic E. coli in another with loose stools. Other infections included four urinary tract infections, three cases of pneumonia, one E. coli bacteremia and one tooth infection.

Within a month of the procedure, 27 patients were hospitalized, with 3 of these cases considered possibly related to the procedure.

Findings may not apply to all clinical settings

Vincent B. Young, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pointed out that the findings might not apply to all clinical settings. The participating clinicians were almost all gastroenterologists working in academic centers.

“Most of them are not Joe Doctor at the doctor’s office,” said Dr. Young, who was not involved with the study. Clinicians in other specialties, such as infectious diseases, might be more inclined to administer fecal transplants through capsules rather than colonoscopies.

And he added that the study does not address effects of the transplant that might develop over years. “Some people talk about how changes in the microbiota lead to increased risk for long-term complications, things like cancer or heart disease. You’re not going to see those in 6 months.”

Also, the study didn’t yield any findings on indications other than C. diff. “In no way, shape, or form does it mean you can use it for autism, depression, heart disease, or [irritable bowel syndrome],” he said.

Still, he said, the study “confirms the fact that fecal cell transplantation is an effective treatment for recurrent C. diff infection when administered as they administered it.”

The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases funded the registry. Dr. Kelly reported a relationship with Finch Therapeutics. Dr. Young reports financial relationships with Vedanta Biosciences and Bio-K+.

This story was updated on Oct. 4, 2020.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) appears safe and effective as a treatment for most Clostridioides difficile infections as it is currently being administered, researchers say.

“We actually didn’t see any infections that were definitely transmissible via fecal transplant,” Colleen Kelly, MD, an associate professor of medicine at Brown University, Providence, R.I., said in an interview.

The findings, published online Oct. 1 in the journal Gastroenterology, come from the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA) NIH-funded FMT National Registry and could allay concerns about a treatment that has yet to gain full approval by the Food and Drug Administration, despite successful clinical trials.

C. diff infections are common and increasing in the United States, often can’t be cured with conventional treatments such as antibiotics, and can be deadly.

Transplanting fecal matter from a donor to the patient appears to work by restoring beneficial microorganisms to the patient’s gut. The procedure is also under investigation for a wide range of other ailments, from irritable bowel syndrome to mood disorders.

But much remains unknown. Researchers have counted a thousand bacterial species along with viruses, bacteriophages, archaea, and fungi in the human gut that interact in complex ways, not all of them beneficial.

The FDA has not enforced regulations that would prohibit the procedure, but in March, it warned about infections with enteropathogenic Escherichia coli and Shiga toxin–producing E. coli following fecal transplants.

As a result of these reports, and the theoretical risk of spreading SARS-CoV-2, OpenBiome, the largest stool bank in the United States, has suspended shipments except for emergency orders, and asked clinicians to quarantine any of its products they already have on hand.

In the meantime, long-term effects of the treatment have not been well documented. And clinical trials have excluded patients who might benefit, such as those who have been immunocompromised or have inflammatory bowel disease.

National registry follows patients outside clinical trials

To better understand how patients fare outside these trials, AGA and other organizations developed a national registry, funded by a grant from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The current report summarizes results on 259 patients enrolled between Dec. 5, 2017, and Sept. 2, 2019 at 20 sites.

At baseline, 44% of these patients suffered moderate and 36% mild C. diff infections. The duration of the diagnosis ranged from less than 1 week to 9 years, with a median duration of 20 weeks. They ranged from 1 to 15 episodes with a mean of 3.5.

Almost all had received vancomycin, and 62% had at least two courses. About 40% had received metronidazole and 28% had received fidaxomicin.

Almost all participants received stool from an unknown donor, mostly from stool banks, with OpenBiome accounting for 67%. About 85% of the transplants were administered through colonoscopy and 6% by upper endoscopy.

Out of 222 patients who returned for a 1-month follow-up, 90% met the investigators’ definition of cure: resolution of diarrhea without need for further anti–C. diff therapy. About 98% received only one transplant. An intent to treat analysis produced a cure rate of 86%.

Results were good in patients with comorbidities, including 12% who had irritable bowel syndrome, 9% who had ulcerative colitis, and 7% who had Crohn’s disease, Dr. Kelly said. “I hope everybody sees the importance of it. In these patients that are more complicated, who may have underlying comorbidities, who may not have been in the clinical trials, it looks effective in that group, and also incredibly safe.”

She added that the risk of transmitting SARS-CoV-2 is minor. “I think it would be a very, very unlikely way for someone to get a respiratory pathogen.”

Of the 112 participants who were cured at 1 month and returned for follow-up after 6 months, 4 developed recurrent C. diff infection. Eleven patients who were not cured in the first month returned after 6 months. Of these, seven were reported cured at this later follow-up.

Three complications occurred as result of the procedure: one colonoscopic perforation and two episodes of gastrointestinal bleeding.

About 45% of participants reported at least one symptom, with diarrhea not related to C. difficile the most common, followed by abdominal pain, bloating, and constipation.

Eleven patients suffered infections, including two which the investigators thought might be related to the procedure: Bacteroides fragilis in one participant with severe diarrhea, and enteropathogenic E. coli in another with loose stools. Other infections included four urinary tract infections, three cases of pneumonia, one E. coli bacteremia and one tooth infection.

Within a month of the procedure, 27 patients were hospitalized, with 3 of these cases considered possibly related to the procedure.

Findings may not apply to all clinical settings

Vincent B. Young, MD, PhD, a professor of medicine and infectious diseases at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, pointed out that the findings might not apply to all clinical settings. The participating clinicians were almost all gastroenterologists working in academic centers.

“Most of them are not Joe Doctor at the doctor’s office,” said Dr. Young, who was not involved with the study. Clinicians in other specialties, such as infectious diseases, might be more inclined to administer fecal transplants through capsules rather than colonoscopies.