User login

Work-life balance dwarfs pay in female doctors’ top concerns

who responded to a new Medscape survey, far outpacing concerns about pay.

A psychiatrist who responded to the survey commented, “I’ve been trying to use all my vacation to spend time with my spouse. I’m always apologizing for being late, not being able to go to an event due to my work schedule, and missing out on life with my husband.”

Nearly two thirds (64%) said the balance was their top concern whereas 43% put pay at the top.

Medscape surveyed more than 3,000 women physicians about how they deal with parenthood, work pressures, and relationships in Women Physicians 2020: The Issues They Care About.

Almost all are making personal trade-offs

An overwhelming percentage (94%) said they have had to make personal trade-offs for work obligations.

“Women are more likely to make work compromises to benefit their families,” a cardiologist responded. “I won’t/can’t take a position that would disrupt my husband’s community ties, my children’s schooling, and relationships with family.”

More than one-third of women (36%) said that being a woman had a negative or very negative impact on their compensation. Only 4% said their gender had a positive or very positive impact on pay and 59% said gender had no effect.

The Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020 showed male specialists made 31% more than their female counterparts and male primary care physicians earned 25% more.

Some factors may help explain some of the difference, but others remain unclear.

Poor negotiating skills have long been cited as a reason women get paid less; in this survey 39% said they were unskilled or very unskilled in salary negotiations, compared with 28% who said they were skilled or very skilled in those talks.

Katie Donovan, founder of Equal Pay Negotiations, reports that only 30% of women negotiate pay at all, compared with 46% of men.

Additionally, women tend to gravitate in specialties that don’t pay as well.

They are poorly represented in some of the highest-paying specialties: orthopedics (9%), urology (12%), and cardiology (14%).

“Society’s view of women as caretaker is powerful,” a radiologist commented. “Women feel like they need to choose specialties where they can work part-time or flexible time in order to be the primary caretaker at home.”

Confidence high in leadership abilities

The survey asked women about their confidence in taking a leadership role, and 90% answered that they were confident about taking such a role. However, only half said they had a leadership or supervisory role.

According to the American Medical Association, women make up 3% of healthcare chief medical officers, 6% of department chairs, and 9% of division leaders.

Asked whether women have experienced gender inequity in the workplace, respondents were almost evenly split, but hospital-based physicians at 61% were more likely to report inequity than were 42% of office-based physicians.

A family physician responded, “I have experienced gender inequality more from administrators than from my male colleagues. I think it’s coming from corporate more than from medical professionals.”

In this survey, 3% said their male colleagues were unsupportive of gender equality in the workplace.

The survey responses indicate most women physicians who have children are also conflicted as parents regarding their careers. Almost two-thirds (64%) said they were always or often conflicted with these dueling priorities; only 8% said they sometimes or rarely are.

Those conflicts start even before having children. More than half in this survey (52%) said their career influenced the number of children they have.

A family physician said, “I delayed starting a family because of my career. That affected my fertility and made it hard to complete [in-vitro fertilization].”

Family responsibilities meet stigma

Half of the respondents said women physicians are stigmatized for taking a full maternity leave (6 weeks or longer). An even higher percentage (65%) said women are stigmatized for taking more flexible or fewer hours to accommodate family responsibilities.

A 2019 survey of 844 physician mothers found that physicians who took maternity leave received lower peer evaluation scores, lost potential income, and reported experiencing discrimination. One-quarter of the participants (25.8%) reported experiencing discrimination related to breastfeeding or breast milk pumping upon their return to work.

Burnout at work puts stress on primary relationships, 63% of respondents said, although 24% said it did not strain those relationships. Thirteen percent of women gave the response “not applicable.”

“I try to be present when I’m home, but to be honest, I don’t deal with it very well,” a family physician commented.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

who responded to a new Medscape survey, far outpacing concerns about pay.

A psychiatrist who responded to the survey commented, “I’ve been trying to use all my vacation to spend time with my spouse. I’m always apologizing for being late, not being able to go to an event due to my work schedule, and missing out on life with my husband.”

Nearly two thirds (64%) said the balance was their top concern whereas 43% put pay at the top.

Medscape surveyed more than 3,000 women physicians about how they deal with parenthood, work pressures, and relationships in Women Physicians 2020: The Issues They Care About.

Almost all are making personal trade-offs

An overwhelming percentage (94%) said they have had to make personal trade-offs for work obligations.

“Women are more likely to make work compromises to benefit their families,” a cardiologist responded. “I won’t/can’t take a position that would disrupt my husband’s community ties, my children’s schooling, and relationships with family.”

More than one-third of women (36%) said that being a woman had a negative or very negative impact on their compensation. Only 4% said their gender had a positive or very positive impact on pay and 59% said gender had no effect.

The Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020 showed male specialists made 31% more than their female counterparts and male primary care physicians earned 25% more.

Some factors may help explain some of the difference, but others remain unclear.

Poor negotiating skills have long been cited as a reason women get paid less; in this survey 39% said they were unskilled or very unskilled in salary negotiations, compared with 28% who said they were skilled or very skilled in those talks.

Katie Donovan, founder of Equal Pay Negotiations, reports that only 30% of women negotiate pay at all, compared with 46% of men.

Additionally, women tend to gravitate in specialties that don’t pay as well.

They are poorly represented in some of the highest-paying specialties: orthopedics (9%), urology (12%), and cardiology (14%).

“Society’s view of women as caretaker is powerful,” a radiologist commented. “Women feel like they need to choose specialties where they can work part-time or flexible time in order to be the primary caretaker at home.”

Confidence high in leadership abilities

The survey asked women about their confidence in taking a leadership role, and 90% answered that they were confident about taking such a role. However, only half said they had a leadership or supervisory role.

According to the American Medical Association, women make up 3% of healthcare chief medical officers, 6% of department chairs, and 9% of division leaders.

Asked whether women have experienced gender inequity in the workplace, respondents were almost evenly split, but hospital-based physicians at 61% were more likely to report inequity than were 42% of office-based physicians.

A family physician responded, “I have experienced gender inequality more from administrators than from my male colleagues. I think it’s coming from corporate more than from medical professionals.”

In this survey, 3% said their male colleagues were unsupportive of gender equality in the workplace.

The survey responses indicate most women physicians who have children are also conflicted as parents regarding their careers. Almost two-thirds (64%) said they were always or often conflicted with these dueling priorities; only 8% said they sometimes or rarely are.

Those conflicts start even before having children. More than half in this survey (52%) said their career influenced the number of children they have.

A family physician said, “I delayed starting a family because of my career. That affected my fertility and made it hard to complete [in-vitro fertilization].”

Family responsibilities meet stigma

Half of the respondents said women physicians are stigmatized for taking a full maternity leave (6 weeks or longer). An even higher percentage (65%) said women are stigmatized for taking more flexible or fewer hours to accommodate family responsibilities.

A 2019 survey of 844 physician mothers found that physicians who took maternity leave received lower peer evaluation scores, lost potential income, and reported experiencing discrimination. One-quarter of the participants (25.8%) reported experiencing discrimination related to breastfeeding or breast milk pumping upon their return to work.

Burnout at work puts stress on primary relationships, 63% of respondents said, although 24% said it did not strain those relationships. Thirteen percent of women gave the response “not applicable.”

“I try to be present when I’m home, but to be honest, I don’t deal with it very well,” a family physician commented.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

who responded to a new Medscape survey, far outpacing concerns about pay.

A psychiatrist who responded to the survey commented, “I’ve been trying to use all my vacation to spend time with my spouse. I’m always apologizing for being late, not being able to go to an event due to my work schedule, and missing out on life with my husband.”

Nearly two thirds (64%) said the balance was their top concern whereas 43% put pay at the top.

Medscape surveyed more than 3,000 women physicians about how they deal with parenthood, work pressures, and relationships in Women Physicians 2020: The Issues They Care About.

Almost all are making personal trade-offs

An overwhelming percentage (94%) said they have had to make personal trade-offs for work obligations.

“Women are more likely to make work compromises to benefit their families,” a cardiologist responded. “I won’t/can’t take a position that would disrupt my husband’s community ties, my children’s schooling, and relationships with family.”

More than one-third of women (36%) said that being a woman had a negative or very negative impact on their compensation. Only 4% said their gender had a positive or very positive impact on pay and 59% said gender had no effect.

The Medscape Physician Compensation Report 2020 showed male specialists made 31% more than their female counterparts and male primary care physicians earned 25% more.

Some factors may help explain some of the difference, but others remain unclear.

Poor negotiating skills have long been cited as a reason women get paid less; in this survey 39% said they were unskilled or very unskilled in salary negotiations, compared with 28% who said they were skilled or very skilled in those talks.

Katie Donovan, founder of Equal Pay Negotiations, reports that only 30% of women negotiate pay at all, compared with 46% of men.

Additionally, women tend to gravitate in specialties that don’t pay as well.

They are poorly represented in some of the highest-paying specialties: orthopedics (9%), urology (12%), and cardiology (14%).

“Society’s view of women as caretaker is powerful,” a radiologist commented. “Women feel like they need to choose specialties where they can work part-time or flexible time in order to be the primary caretaker at home.”

Confidence high in leadership abilities

The survey asked women about their confidence in taking a leadership role, and 90% answered that they were confident about taking such a role. However, only half said they had a leadership or supervisory role.

According to the American Medical Association, women make up 3% of healthcare chief medical officers, 6% of department chairs, and 9% of division leaders.

Asked whether women have experienced gender inequity in the workplace, respondents were almost evenly split, but hospital-based physicians at 61% were more likely to report inequity than were 42% of office-based physicians.

A family physician responded, “I have experienced gender inequality more from administrators than from my male colleagues. I think it’s coming from corporate more than from medical professionals.”

In this survey, 3% said their male colleagues were unsupportive of gender equality in the workplace.

The survey responses indicate most women physicians who have children are also conflicted as parents regarding their careers. Almost two-thirds (64%) said they were always or often conflicted with these dueling priorities; only 8% said they sometimes or rarely are.

Those conflicts start even before having children. More than half in this survey (52%) said their career influenced the number of children they have.

A family physician said, “I delayed starting a family because of my career. That affected my fertility and made it hard to complete [in-vitro fertilization].”

Family responsibilities meet stigma

Half of the respondents said women physicians are stigmatized for taking a full maternity leave (6 weeks or longer). An even higher percentage (65%) said women are stigmatized for taking more flexible or fewer hours to accommodate family responsibilities.

A 2019 survey of 844 physician mothers found that physicians who took maternity leave received lower peer evaluation scores, lost potential income, and reported experiencing discrimination. One-quarter of the participants (25.8%) reported experiencing discrimination related to breastfeeding or breast milk pumping upon their return to work.

Burnout at work puts stress on primary relationships, 63% of respondents said, although 24% said it did not strain those relationships. Thirteen percent of women gave the response “not applicable.”

“I try to be present when I’m home, but to be honest, I don’t deal with it very well,” a family physician commented.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Ex-nursing assistant pleads guilty in West Virginia insulin deaths

A former nursing assistant and Army veteran pleaded guilty to federal murder charges this week in connection with the 2017-2018 deaths of seven patients in a West Virginia veteran’s hospital, according to news reports.

Prosecutors said in court documents filed on July 13 that Reta Mays, 46, injected lethal doses of insulin into seven veterans at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center (VAMC) in rural Clarksburg, W.Va.

Their blood glucose levels plummeted, and each died shortly after their injections, according to the Tennessean.

An eighth patient, a 92-year-old man whom Mays is accused of assaulting with an insulin injection, initially survived after staff were able to stabilize him but died 2 weeks later at a nursing home, NPR reports.

According to NPR, US Attorney Jarod Douglas told the court Tuesday that the medical investigator could not determine whether the insulin contributed to the man’s death but that it was Mays’ intention to kill him.

“No one watched while she injected them with lethal doses of insulin during an 11-month killing rampage,” the Washington Post reported.

No motive offered

The Post article said no motive has been established, but after a 2-year investigation into a pattern of suspicious deaths that took the hospital almost a year to detect, Mays, who had denied any wrongdoing in multiple interviews with investigators, told a federal judge she preyed on some of the country›s most vulnerable service members.

An attorney for Mays, Brian Kornbrath, contacted by Medscape Medical News, said: “The defense team decided that we would have no public comment at this time.”

According to court documents from the Northern District of West Virginia, Mays was charged with seven counts of second-degree murder and one count of assault with intent to commit murder in connection with the patient who died later.

Mays was hired at the VAMC in Clarksburg in June 2015. She worked from 7:30 PM to 8:00 AM in the medical surgical unit, court documents say.

According to the documents, “VAMC Clarksburg did not require a nursing assistant to have a certification or licensure for initial appointment or as a condition of continuing employment.”

The documents indicate that in June 2018, a hospitalist employed by VAMC Clarksburg reported concern about several deaths from unexplained hypoglycemic events in the same ward and noted that many of the affected patients did not have diabetes.

By that time, according to the Tennessean, “at least eight patients had died under suspicious circumstances. Several had been embalmed and buried, destroying potential evidence. One veteran had been cremated.”

An internal investigation began, followed by a criminal investigation, and in July 2018, Mays was removed from patient care.

Mays fired in 2019 because of lies on resume; claims suffers from PTSD

The Post reports that Mays was fired from the hospital in 2019, 7 months after she was banned from patient care, «after it was discovered she had lied about her qualifications on her resume.»

Court documents indicate that her duties included acting as a sitter for patients, checking vital signs, intake and output, and testing blood glucose levels, but she was not qualified to administer medications, including insulin.

Similarities in the deaths were evident, the Post reported. Citing sources familiar with the case, the report said, “elderly patients in private rooms were injected in their abdomen and limbs with insulin the hospital had not ordered.”

The Post reported that Mays sobbed by the end of the hearing on Tuesday.

The article notes that Mays has three sons and served in the Army National Guard from November 2000 to April 2001 and again from February 2003 to May 2004, when she was deployed to Iraq and Kuwait. She told the judge she was taking medication for posttraumatic stress disorder.

By pleading guilty, she waived her right to have the case presented to a grand jury. A sentencing hearing has not been scheduled, the Post reports.

NPR notes that prosecutors have requested that Mays serve seven consecutive life sentences and an additional 20 years in prison.

“Our hearts go out to those affected by these tragic deaths”

A spokesman for VAMC Clarksburg said in a statement to Medscape Medical News: “Our hearts go out to those affected by these tragic deaths. Clarksburg VA Medical Center discovered these allegations and reported them to VA›s independent inspector general more than 2 years ago. Clarksburg VA Medical Center also fired the individual at the center of the allegations.

“We’re glad the Department of Justice stepped in to push this investigation across the finish line and hopeful our court system will deliver the justice Clarksburg-area Veterans and families deserve.”

According to the Tennessean, Michael Missal, inspector general for the Department of Veteran Affairs, said the agency is investigating the hospital’s practices, “including medication management and communications among staffers.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A former nursing assistant and Army veteran pleaded guilty to federal murder charges this week in connection with the 2017-2018 deaths of seven patients in a West Virginia veteran’s hospital, according to news reports.

Prosecutors said in court documents filed on July 13 that Reta Mays, 46, injected lethal doses of insulin into seven veterans at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center (VAMC) in rural Clarksburg, W.Va.

Their blood glucose levels plummeted, and each died shortly after their injections, according to the Tennessean.

An eighth patient, a 92-year-old man whom Mays is accused of assaulting with an insulin injection, initially survived after staff were able to stabilize him but died 2 weeks later at a nursing home, NPR reports.

According to NPR, US Attorney Jarod Douglas told the court Tuesday that the medical investigator could not determine whether the insulin contributed to the man’s death but that it was Mays’ intention to kill him.

“No one watched while she injected them with lethal doses of insulin during an 11-month killing rampage,” the Washington Post reported.

No motive offered

The Post article said no motive has been established, but after a 2-year investigation into a pattern of suspicious deaths that took the hospital almost a year to detect, Mays, who had denied any wrongdoing in multiple interviews with investigators, told a federal judge she preyed on some of the country›s most vulnerable service members.

An attorney for Mays, Brian Kornbrath, contacted by Medscape Medical News, said: “The defense team decided that we would have no public comment at this time.”

According to court documents from the Northern District of West Virginia, Mays was charged with seven counts of second-degree murder and one count of assault with intent to commit murder in connection with the patient who died later.

Mays was hired at the VAMC in Clarksburg in June 2015. She worked from 7:30 PM to 8:00 AM in the medical surgical unit, court documents say.

According to the documents, “VAMC Clarksburg did not require a nursing assistant to have a certification or licensure for initial appointment or as a condition of continuing employment.”

The documents indicate that in June 2018, a hospitalist employed by VAMC Clarksburg reported concern about several deaths from unexplained hypoglycemic events in the same ward and noted that many of the affected patients did not have diabetes.

By that time, according to the Tennessean, “at least eight patients had died under suspicious circumstances. Several had been embalmed and buried, destroying potential evidence. One veteran had been cremated.”

An internal investigation began, followed by a criminal investigation, and in July 2018, Mays was removed from patient care.

Mays fired in 2019 because of lies on resume; claims suffers from PTSD

The Post reports that Mays was fired from the hospital in 2019, 7 months after she was banned from patient care, «after it was discovered she had lied about her qualifications on her resume.»

Court documents indicate that her duties included acting as a sitter for patients, checking vital signs, intake and output, and testing blood glucose levels, but she was not qualified to administer medications, including insulin.

Similarities in the deaths were evident, the Post reported. Citing sources familiar with the case, the report said, “elderly patients in private rooms were injected in their abdomen and limbs with insulin the hospital had not ordered.”

The Post reported that Mays sobbed by the end of the hearing on Tuesday.

The article notes that Mays has three sons and served in the Army National Guard from November 2000 to April 2001 and again from February 2003 to May 2004, when she was deployed to Iraq and Kuwait. She told the judge she was taking medication for posttraumatic stress disorder.

By pleading guilty, she waived her right to have the case presented to a grand jury. A sentencing hearing has not been scheduled, the Post reports.

NPR notes that prosecutors have requested that Mays serve seven consecutive life sentences and an additional 20 years in prison.

“Our hearts go out to those affected by these tragic deaths”

A spokesman for VAMC Clarksburg said in a statement to Medscape Medical News: “Our hearts go out to those affected by these tragic deaths. Clarksburg VA Medical Center discovered these allegations and reported them to VA›s independent inspector general more than 2 years ago. Clarksburg VA Medical Center also fired the individual at the center of the allegations.

“We’re glad the Department of Justice stepped in to push this investigation across the finish line and hopeful our court system will deliver the justice Clarksburg-area Veterans and families deserve.”

According to the Tennessean, Michael Missal, inspector general for the Department of Veteran Affairs, said the agency is investigating the hospital’s practices, “including medication management and communications among staffers.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A former nursing assistant and Army veteran pleaded guilty to federal murder charges this week in connection with the 2017-2018 deaths of seven patients in a West Virginia veteran’s hospital, according to news reports.

Prosecutors said in court documents filed on July 13 that Reta Mays, 46, injected lethal doses of insulin into seven veterans at the Louis A. Johnson VA Medical Center (VAMC) in rural Clarksburg, W.Va.

Their blood glucose levels plummeted, and each died shortly after their injections, according to the Tennessean.

An eighth patient, a 92-year-old man whom Mays is accused of assaulting with an insulin injection, initially survived after staff were able to stabilize him but died 2 weeks later at a nursing home, NPR reports.

According to NPR, US Attorney Jarod Douglas told the court Tuesday that the medical investigator could not determine whether the insulin contributed to the man’s death but that it was Mays’ intention to kill him.

“No one watched while she injected them with lethal doses of insulin during an 11-month killing rampage,” the Washington Post reported.

No motive offered

The Post article said no motive has been established, but after a 2-year investigation into a pattern of suspicious deaths that took the hospital almost a year to detect, Mays, who had denied any wrongdoing in multiple interviews with investigators, told a federal judge she preyed on some of the country›s most vulnerable service members.

An attorney for Mays, Brian Kornbrath, contacted by Medscape Medical News, said: “The defense team decided that we would have no public comment at this time.”

According to court documents from the Northern District of West Virginia, Mays was charged with seven counts of second-degree murder and one count of assault with intent to commit murder in connection with the patient who died later.

Mays was hired at the VAMC in Clarksburg in June 2015. She worked from 7:30 PM to 8:00 AM in the medical surgical unit, court documents say.

According to the documents, “VAMC Clarksburg did not require a nursing assistant to have a certification or licensure for initial appointment or as a condition of continuing employment.”

The documents indicate that in June 2018, a hospitalist employed by VAMC Clarksburg reported concern about several deaths from unexplained hypoglycemic events in the same ward and noted that many of the affected patients did not have diabetes.

By that time, according to the Tennessean, “at least eight patients had died under suspicious circumstances. Several had been embalmed and buried, destroying potential evidence. One veteran had been cremated.”

An internal investigation began, followed by a criminal investigation, and in July 2018, Mays was removed from patient care.

Mays fired in 2019 because of lies on resume; claims suffers from PTSD

The Post reports that Mays was fired from the hospital in 2019, 7 months after she was banned from patient care, «after it was discovered she had lied about her qualifications on her resume.»

Court documents indicate that her duties included acting as a sitter for patients, checking vital signs, intake and output, and testing blood glucose levels, but she was not qualified to administer medications, including insulin.

Similarities in the deaths were evident, the Post reported. Citing sources familiar with the case, the report said, “elderly patients in private rooms were injected in their abdomen and limbs with insulin the hospital had not ordered.”

The Post reported that Mays sobbed by the end of the hearing on Tuesday.

The article notes that Mays has three sons and served in the Army National Guard from November 2000 to April 2001 and again from February 2003 to May 2004, when she was deployed to Iraq and Kuwait. She told the judge she was taking medication for posttraumatic stress disorder.

By pleading guilty, she waived her right to have the case presented to a grand jury. A sentencing hearing has not been scheduled, the Post reports.

NPR notes that prosecutors have requested that Mays serve seven consecutive life sentences and an additional 20 years in prison.

“Our hearts go out to those affected by these tragic deaths”

A spokesman for VAMC Clarksburg said in a statement to Medscape Medical News: “Our hearts go out to those affected by these tragic deaths. Clarksburg VA Medical Center discovered these allegations and reported them to VA›s independent inspector general more than 2 years ago. Clarksburg VA Medical Center also fired the individual at the center of the allegations.

“We’re glad the Department of Justice stepped in to push this investigation across the finish line and hopeful our court system will deliver the justice Clarksburg-area Veterans and families deserve.”

According to the Tennessean, Michael Missal, inspector general for the Department of Veteran Affairs, said the agency is investigating the hospital’s practices, “including medication management and communications among staffers.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Residents, fellows will get minimum 6 weeks leave for caregiving

the American Board of Medical Specialties has announced.

The “ABMS Policy on Parental, Caregiver and Family Leave” announced July 13 was developed after a report from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Council of Review Committee Residents in June 2019.

Richard E. Hawkins, MD, ABMS President and CEO, said in a statement that “the growing shifts in viewpoints regarding work-life balance and parental roles had a great influence in the creation of this policy, which fosters an environment that supports our trainees’ ability to care not only for patients, but also for themselves and their families.”

Specifically, the time can be taken for birth and care of a newborn, adopting a child, or becoming a foster parent; care of a child, spouse, or parent with a serious health condition; or the trainee’s own serious health condition. The policy applies to member boards with training programs of at least 2 years.

Boards must communicate when a leave will require an official extension to avoid disruptions to a physician’s career trajectory, a delay in starting a fellowship, or moving into a salaried position.

Work/life balance was by far the biggest challenge reported in the Medscape Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019.

Several member boards had already implemented policies that offered more flexibility without unduly delaying board certification; now ABMS is extending that to all boards.

ABMS says member boards may limit the maximum time away in a single year or level of training and directed member boards to “make reasonable testing accommodations” – for example, by allowing candidates to take an exam provided the candidate completes all training requirements by a certain date.

Kristy Rialon, MD, an author of the ACGME report and assistant professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine and the Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, noted the significance of the change in a news release.

“By virtue of their ages, residents and fellows – male and female – often find themselves having and raising children, as well as serving as family members’ caregivers,” Dr. Rialon said. “By adopting more realistic and compassionate approaches, the ABMS member boards will significantly improve the quality of life for residents and fellows. This also will support our female physicians, helping to narrow the gender gap in their career advancement by allowing for greater leave flexibility.”

A Medscape survey published July 15 said work-life balance was the No. 1 concern of female physicians, far outpacing pay.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

the American Board of Medical Specialties has announced.

The “ABMS Policy on Parental, Caregiver and Family Leave” announced July 13 was developed after a report from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Council of Review Committee Residents in June 2019.

Richard E. Hawkins, MD, ABMS President and CEO, said in a statement that “the growing shifts in viewpoints regarding work-life balance and parental roles had a great influence in the creation of this policy, which fosters an environment that supports our trainees’ ability to care not only for patients, but also for themselves and their families.”

Specifically, the time can be taken for birth and care of a newborn, adopting a child, or becoming a foster parent; care of a child, spouse, or parent with a serious health condition; or the trainee’s own serious health condition. The policy applies to member boards with training programs of at least 2 years.

Boards must communicate when a leave will require an official extension to avoid disruptions to a physician’s career trajectory, a delay in starting a fellowship, or moving into a salaried position.

Work/life balance was by far the biggest challenge reported in the Medscape Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019.

Several member boards had already implemented policies that offered more flexibility without unduly delaying board certification; now ABMS is extending that to all boards.

ABMS says member boards may limit the maximum time away in a single year or level of training and directed member boards to “make reasonable testing accommodations” – for example, by allowing candidates to take an exam provided the candidate completes all training requirements by a certain date.

Kristy Rialon, MD, an author of the ACGME report and assistant professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine and the Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, noted the significance of the change in a news release.

“By virtue of their ages, residents and fellows – male and female – often find themselves having and raising children, as well as serving as family members’ caregivers,” Dr. Rialon said. “By adopting more realistic and compassionate approaches, the ABMS member boards will significantly improve the quality of life for residents and fellows. This also will support our female physicians, helping to narrow the gender gap in their career advancement by allowing for greater leave flexibility.”

A Medscape survey published July 15 said work-life balance was the No. 1 concern of female physicians, far outpacing pay.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

the American Board of Medical Specialties has announced.

The “ABMS Policy on Parental, Caregiver and Family Leave” announced July 13 was developed after a report from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s Council of Review Committee Residents in June 2019.

Richard E. Hawkins, MD, ABMS President and CEO, said in a statement that “the growing shifts in viewpoints regarding work-life balance and parental roles had a great influence in the creation of this policy, which fosters an environment that supports our trainees’ ability to care not only for patients, but also for themselves and their families.”

Specifically, the time can be taken for birth and care of a newborn, adopting a child, or becoming a foster parent; care of a child, spouse, or parent with a serious health condition; or the trainee’s own serious health condition. The policy applies to member boards with training programs of at least 2 years.

Boards must communicate when a leave will require an official extension to avoid disruptions to a physician’s career trajectory, a delay in starting a fellowship, or moving into a salaried position.

Work/life balance was by far the biggest challenge reported in the Medscape Residents Lifestyle & Happiness Report 2019.

Several member boards had already implemented policies that offered more flexibility without unduly delaying board certification; now ABMS is extending that to all boards.

ABMS says member boards may limit the maximum time away in a single year or level of training and directed member boards to “make reasonable testing accommodations” – for example, by allowing candidates to take an exam provided the candidate completes all training requirements by a certain date.

Kristy Rialon, MD, an author of the ACGME report and assistant professor of surgery at Baylor College of Medicine and the Texas Children’s Hospital, both in Houston, noted the significance of the change in a news release.

“By virtue of their ages, residents and fellows – male and female – often find themselves having and raising children, as well as serving as family members’ caregivers,” Dr. Rialon said. “By adopting more realistic and compassionate approaches, the ABMS member boards will significantly improve the quality of life for residents and fellows. This also will support our female physicians, helping to narrow the gender gap in their career advancement by allowing for greater leave flexibility.”

A Medscape survey published July 15 said work-life balance was the No. 1 concern of female physicians, far outpacing pay.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Intubation boxes may do more harm than good in COVID-19 risk

Clear aerosol boxes designed to keep COVID-19 patients’ airborne droplets from infecting health care workers during intubation may actually increase providers’ exposure to the virus, a small study suggests.

Joanna P. Simpson, MbChB, an intensivist in the department of anaesthesia and perioperative medicine at Eastern Health in Melbourne, and colleagues tested five models of barriers used for protection while intubating simulated “patients” with COVID-19 and compared the interventions with a control of having no protection. They published their findings online in Anaesthesia.

Coauthor Peter Chan, MBBS, also an intensivist at Eastern Health, said in an interview that the virus essentially concentrates inside the box and because the box has holes on the sides to allow providers’ arms in, the gaps “act as nozzles, so when a patient coughs, it creates a sudden wave of air that pushes all these particles out the path of least resistance” and into the face of the intubator.

Their institution stopped using any such aerosol-containment devices during intubation until safety can be proven.

Many forms for boxes

The boxes take different forms and are made by various designers and manufacturers around the world, including in the United States, but they generally cover the head and upper body of patients and allow providers to reach through holes to intubate.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 1 issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for “protective barrier enclosures ... to prevent [health care provider] exposure to pathogenic biological airborne particulates by providing an extra layer of barrier protection in addition to personal protective equipment [PPE].”

Others refer to them as “intubation boxes.” A search of GoFundMe campaigns showed hundreds of campaigns for intubation boxes.

Dr. Simpson and colleagues used an in-situ simulation model to evaluate laryngoscopist exposure to airborne particles sized 0.3-5.0 mcm using five aerosol containment devices (aerosol box, sealed box with suction, sealed box without suction, vertical drapes, and horizontal drapes) compared with no aerosol containment device.

Nebulized saline was used in an aerosol-generating model for 300 seconds, at which point the devices were removed to gauge particle spread for another 60 seconds.

Compared with no device use, the sealed intubation box with suction resulted in a decreased exposure for particle sizes of 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.5 mcm – but not 5.0 mcm – over all time periods (P = .003 for all time periods, which ranged from 30 to 360 seconds).

Conversely, the aerosol box, compared with no device use, showed an increase in 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mcm airborne-particle exposure at 300 seconds (P = .002, 0.008, and .002, respectively). Compared with no device use, neither horizontal nor vertical drapes showed any difference in any particle size exposure at any time.

The researchers used seven volunteers who took turns acting as the patient or the intubator. As each of the seven volunteers did all six trials (the five interventions plus no intervention), the study generated 42 sets of results.

More evidence passive boxes are ineffective

Plastic surgeon Dave Turer, MD, MS, who is also an electrical and biomedical engineer, and some emergency physician colleagues had doubts about these boxes early on and wrote about the need for thorough testing.

He told this news organization, “I find it kind of infuriating that if you search for ‘intubation box’ there are all these companies making claims that are totally unsubstantiated.”

A desperate need to stop the virus is leading to unacceptable practices, he said.

His team at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pennsylvania tested commercially available boxes using white vapor to simulate patients› exhaled breath and found the vapor billowed into the surrounding environment.

He said Simpson and colleagues had similar findings: The boxes didn’t contain the patients’ breaths and may even increase the stream heading toward intubators.

Dr. Turer said his team has designed a different kind of box, without armholes for the intubators, and with active airflow and filtering and have submitted their design and research to the FDA for an EUA.

The FDA’s current EUA is for boxes “that are no different from a face shield or a splash shield,” Dr. Turer said, adding that “they specifically state that they are not designed or intended to contain aerosol.”

He said while this study is a good start, his team’s findings will help demonstrate why the common passive boxes should not be used.

One of the most prevalent designs, he pointed out, was one by Taiwanese anesthesiologist Hsien Yung Lai that was widely circulated in March.

David W. Kaczka, MD, PhD, associate professor of anesthesia, biomedical engineering, and radiology at University of Iowa in Iowa City, is one of the researchers who modified that design and made prototypes. He said in an interview he thinks the study conclusion by Simpson et al is “not as dismal as the authors are making it out to be.”

He pointed to the relative success of the sealed box with suction. His team’s adapted model added a suction port to generate a negative pressure field around the patient.

The biggest critique he had of the study, Dr. Kaczka said, was a lack of a true control group.

“They tested all their conditions with nebulized saline,” he pointed out. “I think a more appropriately designed study would have also looked at a group where no saline was being nebulized and see what the particle counts were afterwards. It’s not clear how the device would distinguish between a particle coming from a saline nebulizer vs. coming from a simulated patient vs. coming from the laryngoscopist.”

He also noted that what comes out of a patient is not going to be saline and will have different density and viscosity.

That said, the study by Dr. Simpson and colleagues highlights the need to take a hard look at these boxes with more research, he said, adding, “I think there’s some hope there.”

He noted that a letter to the editor by Boston researchers, published online April 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine, describes how they used fluorescent dye forced from a balloon to simulate a patient’s cough to see whether an aerosol box protected intubators.

That letter concludes, “We suggest that our ad hoc barrier enclosure provided a modicum of additional protection and could be considered to be an adjunct to standard PPE.”

The Anaesthesia findings come as a second global wave becomes more likely as does awareness of the potential of airborne droplets to spread the virus.

Scientists from 32 countries warned the World Health Organization that the spread of COVID-19 through airborne droplets may have been severely underestimated.

On Wednesday, the World Health Organization formally acknowledged evidence regarding potential spread of the virus through these droplets and on Thursday issued an updated brief.

Intellectual property surrounding the device invented by Dr. Turer’s team is owned by UPMC. Dr. Chan and Dr. Kaczka have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clear aerosol boxes designed to keep COVID-19 patients’ airborne droplets from infecting health care workers during intubation may actually increase providers’ exposure to the virus, a small study suggests.

Joanna P. Simpson, MbChB, an intensivist in the department of anaesthesia and perioperative medicine at Eastern Health in Melbourne, and colleagues tested five models of barriers used for protection while intubating simulated “patients” with COVID-19 and compared the interventions with a control of having no protection. They published their findings online in Anaesthesia.

Coauthor Peter Chan, MBBS, also an intensivist at Eastern Health, said in an interview that the virus essentially concentrates inside the box and because the box has holes on the sides to allow providers’ arms in, the gaps “act as nozzles, so when a patient coughs, it creates a sudden wave of air that pushes all these particles out the path of least resistance” and into the face of the intubator.

Their institution stopped using any such aerosol-containment devices during intubation until safety can be proven.

Many forms for boxes

The boxes take different forms and are made by various designers and manufacturers around the world, including in the United States, but they generally cover the head and upper body of patients and allow providers to reach through holes to intubate.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 1 issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for “protective barrier enclosures ... to prevent [health care provider] exposure to pathogenic biological airborne particulates by providing an extra layer of barrier protection in addition to personal protective equipment [PPE].”

Others refer to them as “intubation boxes.” A search of GoFundMe campaigns showed hundreds of campaigns for intubation boxes.

Dr. Simpson and colleagues used an in-situ simulation model to evaluate laryngoscopist exposure to airborne particles sized 0.3-5.0 mcm using five aerosol containment devices (aerosol box, sealed box with suction, sealed box without suction, vertical drapes, and horizontal drapes) compared with no aerosol containment device.

Nebulized saline was used in an aerosol-generating model for 300 seconds, at which point the devices were removed to gauge particle spread for another 60 seconds.

Compared with no device use, the sealed intubation box with suction resulted in a decreased exposure for particle sizes of 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.5 mcm – but not 5.0 mcm – over all time periods (P = .003 for all time periods, which ranged from 30 to 360 seconds).

Conversely, the aerosol box, compared with no device use, showed an increase in 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mcm airborne-particle exposure at 300 seconds (P = .002, 0.008, and .002, respectively). Compared with no device use, neither horizontal nor vertical drapes showed any difference in any particle size exposure at any time.

The researchers used seven volunteers who took turns acting as the patient or the intubator. As each of the seven volunteers did all six trials (the five interventions plus no intervention), the study generated 42 sets of results.

More evidence passive boxes are ineffective

Plastic surgeon Dave Turer, MD, MS, who is also an electrical and biomedical engineer, and some emergency physician colleagues had doubts about these boxes early on and wrote about the need for thorough testing.

He told this news organization, “I find it kind of infuriating that if you search for ‘intubation box’ there are all these companies making claims that are totally unsubstantiated.”

A desperate need to stop the virus is leading to unacceptable practices, he said.

His team at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pennsylvania tested commercially available boxes using white vapor to simulate patients› exhaled breath and found the vapor billowed into the surrounding environment.

He said Simpson and colleagues had similar findings: The boxes didn’t contain the patients’ breaths and may even increase the stream heading toward intubators.

Dr. Turer said his team has designed a different kind of box, without armholes for the intubators, and with active airflow and filtering and have submitted their design and research to the FDA for an EUA.

The FDA’s current EUA is for boxes “that are no different from a face shield or a splash shield,” Dr. Turer said, adding that “they specifically state that they are not designed or intended to contain aerosol.”

He said while this study is a good start, his team’s findings will help demonstrate why the common passive boxes should not be used.

One of the most prevalent designs, he pointed out, was one by Taiwanese anesthesiologist Hsien Yung Lai that was widely circulated in March.

David W. Kaczka, MD, PhD, associate professor of anesthesia, biomedical engineering, and radiology at University of Iowa in Iowa City, is one of the researchers who modified that design and made prototypes. He said in an interview he thinks the study conclusion by Simpson et al is “not as dismal as the authors are making it out to be.”

He pointed to the relative success of the sealed box with suction. His team’s adapted model added a suction port to generate a negative pressure field around the patient.

The biggest critique he had of the study, Dr. Kaczka said, was a lack of a true control group.

“They tested all their conditions with nebulized saline,” he pointed out. “I think a more appropriately designed study would have also looked at a group where no saline was being nebulized and see what the particle counts were afterwards. It’s not clear how the device would distinguish between a particle coming from a saline nebulizer vs. coming from a simulated patient vs. coming from the laryngoscopist.”

He also noted that what comes out of a patient is not going to be saline and will have different density and viscosity.

That said, the study by Dr. Simpson and colleagues highlights the need to take a hard look at these boxes with more research, he said, adding, “I think there’s some hope there.”

He noted that a letter to the editor by Boston researchers, published online April 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine, describes how they used fluorescent dye forced from a balloon to simulate a patient’s cough to see whether an aerosol box protected intubators.

That letter concludes, “We suggest that our ad hoc barrier enclosure provided a modicum of additional protection and could be considered to be an adjunct to standard PPE.”

The Anaesthesia findings come as a second global wave becomes more likely as does awareness of the potential of airborne droplets to spread the virus.

Scientists from 32 countries warned the World Health Organization that the spread of COVID-19 through airborne droplets may have been severely underestimated.

On Wednesday, the World Health Organization formally acknowledged evidence regarding potential spread of the virus through these droplets and on Thursday issued an updated brief.

Intellectual property surrounding the device invented by Dr. Turer’s team is owned by UPMC. Dr. Chan and Dr. Kaczka have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Clear aerosol boxes designed to keep COVID-19 patients’ airborne droplets from infecting health care workers during intubation may actually increase providers’ exposure to the virus, a small study suggests.

Joanna P. Simpson, MbChB, an intensivist in the department of anaesthesia and perioperative medicine at Eastern Health in Melbourne, and colleagues tested five models of barriers used for protection while intubating simulated “patients” with COVID-19 and compared the interventions with a control of having no protection. They published their findings online in Anaesthesia.

Coauthor Peter Chan, MBBS, also an intensivist at Eastern Health, said in an interview that the virus essentially concentrates inside the box and because the box has holes on the sides to allow providers’ arms in, the gaps “act as nozzles, so when a patient coughs, it creates a sudden wave of air that pushes all these particles out the path of least resistance” and into the face of the intubator.

Their institution stopped using any such aerosol-containment devices during intubation until safety can be proven.

Many forms for boxes

The boxes take different forms and are made by various designers and manufacturers around the world, including in the United States, but they generally cover the head and upper body of patients and allow providers to reach through holes to intubate.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration on May 1 issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for “protective barrier enclosures ... to prevent [health care provider] exposure to pathogenic biological airborne particulates by providing an extra layer of barrier protection in addition to personal protective equipment [PPE].”

Others refer to them as “intubation boxes.” A search of GoFundMe campaigns showed hundreds of campaigns for intubation boxes.

Dr. Simpson and colleagues used an in-situ simulation model to evaluate laryngoscopist exposure to airborne particles sized 0.3-5.0 mcm using five aerosol containment devices (aerosol box, sealed box with suction, sealed box without suction, vertical drapes, and horizontal drapes) compared with no aerosol containment device.

Nebulized saline was used in an aerosol-generating model for 300 seconds, at which point the devices were removed to gauge particle spread for another 60 seconds.

Compared with no device use, the sealed intubation box with suction resulted in a decreased exposure for particle sizes of 0.3, 0.5, 1.0, and 2.5 mcm – but not 5.0 mcm – over all time periods (P = .003 for all time periods, which ranged from 30 to 360 seconds).

Conversely, the aerosol box, compared with no device use, showed an increase in 1.0, 2.5, and 5.0 mcm airborne-particle exposure at 300 seconds (P = .002, 0.008, and .002, respectively). Compared with no device use, neither horizontal nor vertical drapes showed any difference in any particle size exposure at any time.

The researchers used seven volunteers who took turns acting as the patient or the intubator. As each of the seven volunteers did all six trials (the five interventions plus no intervention), the study generated 42 sets of results.

More evidence passive boxes are ineffective

Plastic surgeon Dave Turer, MD, MS, who is also an electrical and biomedical engineer, and some emergency physician colleagues had doubts about these boxes early on and wrote about the need for thorough testing.

He told this news organization, “I find it kind of infuriating that if you search for ‘intubation box’ there are all these companies making claims that are totally unsubstantiated.”

A desperate need to stop the virus is leading to unacceptable practices, he said.

His team at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center in Pennsylvania tested commercially available boxes using white vapor to simulate patients› exhaled breath and found the vapor billowed into the surrounding environment.

He said Simpson and colleagues had similar findings: The boxes didn’t contain the patients’ breaths and may even increase the stream heading toward intubators.

Dr. Turer said his team has designed a different kind of box, without armholes for the intubators, and with active airflow and filtering and have submitted their design and research to the FDA for an EUA.

The FDA’s current EUA is for boxes “that are no different from a face shield or a splash shield,” Dr. Turer said, adding that “they specifically state that they are not designed or intended to contain aerosol.”

He said while this study is a good start, his team’s findings will help demonstrate why the common passive boxes should not be used.

One of the most prevalent designs, he pointed out, was one by Taiwanese anesthesiologist Hsien Yung Lai that was widely circulated in March.

David W. Kaczka, MD, PhD, associate professor of anesthesia, biomedical engineering, and radiology at University of Iowa in Iowa City, is one of the researchers who modified that design and made prototypes. He said in an interview he thinks the study conclusion by Simpson et al is “not as dismal as the authors are making it out to be.”

He pointed to the relative success of the sealed box with suction. His team’s adapted model added a suction port to generate a negative pressure field around the patient.

The biggest critique he had of the study, Dr. Kaczka said, was a lack of a true control group.

“They tested all their conditions with nebulized saline,” he pointed out. “I think a more appropriately designed study would have also looked at a group where no saline was being nebulized and see what the particle counts were afterwards. It’s not clear how the device would distinguish between a particle coming from a saline nebulizer vs. coming from a simulated patient vs. coming from the laryngoscopist.”

He also noted that what comes out of a patient is not going to be saline and will have different density and viscosity.

That said, the study by Dr. Simpson and colleagues highlights the need to take a hard look at these boxes with more research, he said, adding, “I think there’s some hope there.”

He noted that a letter to the editor by Boston researchers, published online April 3 in the New England Journal of Medicine, describes how they used fluorescent dye forced from a balloon to simulate a patient’s cough to see whether an aerosol box protected intubators.

That letter concludes, “We suggest that our ad hoc barrier enclosure provided a modicum of additional protection and could be considered to be an adjunct to standard PPE.”

The Anaesthesia findings come as a second global wave becomes more likely as does awareness of the potential of airborne droplets to spread the virus.

Scientists from 32 countries warned the World Health Organization that the spread of COVID-19 through airborne droplets may have been severely underestimated.

On Wednesday, the World Health Organization formally acknowledged evidence regarding potential spread of the virus through these droplets and on Thursday issued an updated brief.

Intellectual property surrounding the device invented by Dr. Turer’s team is owned by UPMC. Dr. Chan and Dr. Kaczka have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Primary care practices may lose about $68k per physician this year

Primary care practices stand to lose almost $68,000 per full-time physician this year as COVID-19 causes care delays and cancellations, researchers estimate. And while some outpatient care has started to rebound to near baseline appointment levels, other ambulatory specialties remain dramatically down from prepandemic rates.

For primary care practices, Sanjay Basu, MD, and colleagues calculated the losses at $67,774 in gross revenue per physician (interquartile range, $80,577-$54,990), with a national toll of $15.1 billion this year.

That’s without a potential second wave of COVID-19, noted Dr. Basu, director of research and population health at Collective Health in San Francisco, and colleagues.

When they added a theoretical stay-at-home order for November and December, the estimated loss climbed to $85,666 in gross revenue per full-time physician, with a loss of $19.1 billion nationally. The findings were published online in Health Affairs.

Meanwhile, clinical losses from canceled outpatient care are piling up as well, according to a study by Ateev Mehrotra, MD, associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues, which calculated the clinical losses in outpatient care.

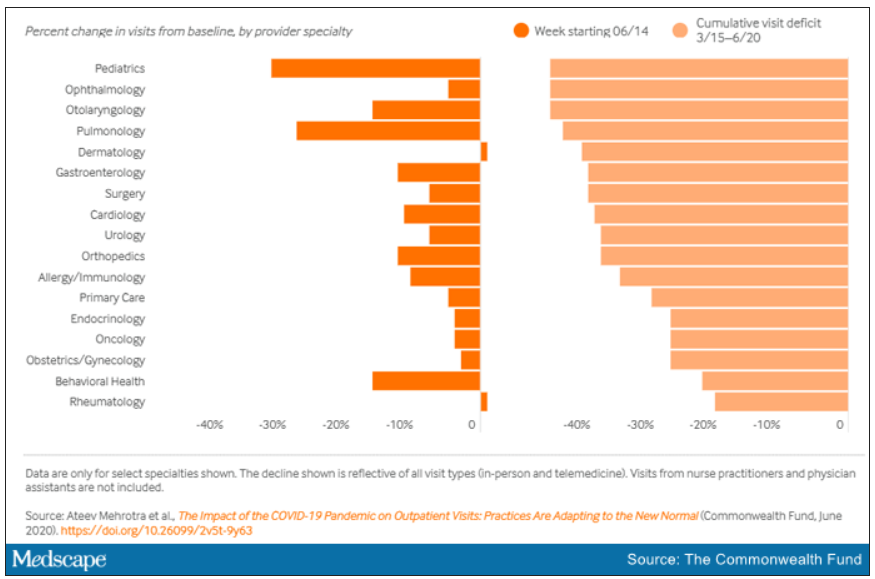

“The ‘cumulative deficit’ in visits over the last 3 months (March 15 to June 20) is nearly 40%,” the authors wrote. They reported their findings in an article published online June 25 by the Commonwealth Fund.

When examined by specialty, Dr. Mehrotra and colleagues found that appointment rebound rates have been uneven. Whereas dermatology and rheumatology visits have already recovered, a couple of specialties have cumulative deficits that are particularly concerning. For example, pediatric visits were down by 47% in the 3 months since March 15 and pulmonology visits were down 45% in that time.

Much depends on the future of telehealth

Closing the financial and care gaps will depend largely on changing payment models for outpatient care and assuring adequate and enduring reimbursement for telehealth, according to experts.

COVID-19 has put a spotlight on the fragility of a fee-for-service system that depends on in-person visits for stability, Daniel Horn, MD, director of population health and quality at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview.

Several things need to happen to change the outlook for outpatient care, he said.

A need mentioned in both studies is that the COVID-19 waivers that make it possible for telehealth visits to be reimbursed like other visits must continue after the pandemic. Those assurances are critical as practices decide whether to invest in telemedicine.

If U.S. practices revert as of Oct. 1, 2020, to the pre–COVID-19 payment system for telehealth, national losses for the year would be more than double the current estimates.

“Given the number of active primary care physicians (n = 223,125), we estimated that the cost would be $38.7 billion (IQR, $31.1 billion-$48.3 billion) at a national level to neutralize the gross revenue losses caused by COVID-19 among primary care practices, without subjecting staff to furloughs,” Dr. Basu and colleagues wrote.

In addition to stabilizing telehealth payment models, another need to improve the outlook for outpatient care is more effective communication that in-person care is safe again in regions with protocols in place, Dr. Horn said.

However, the most important change, Dr. Horn said, is a switch to prospective lump-sum payments – payments made in advance to physicians to treat each patient in the way they and the patient deem best with the most appropriate appointment type – whether by in-person visit, phone call, text reminders, or video session.

Prospective payments would take multipayer coalitions working in conjunction with leadership on the federal level from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Dr. Horn said. Commercial payers and states (through Medicaid funds) should already have that money available with the cancellations of nonessential procedures, he said.

“We expect ongoing turbulent times, so having a prospective payment could unleash the capacity for primary care practices to be creative in the way they care for their patients,” Dr. Horn said.

Visit trends still down

Calculations by Dr. Basu, who is also on the faculty at Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care, and colleagues were partially informed by Dr. Mehrotra’s data on how many visits have been lost because of COVID-19.

Dr. Mehrotra said a clear message in their study is that “visit trends are not back to baseline.”

They found that the number of visits to ambulatory practices had dropped nearly 60% by early April. Since then, numbers have rebounded substantially. As of the week of June 14, overall visits, compared with baseline were down 11%. But the drops varied widely across specialties.

Dr. Mehrotra said he found particularly disturbing the drop in pediatric visits and the sharp contrast between those rates and the higher number of visits for adults. While visits for patients aged 75 and older had climbed back to just 3% below baseline, the drop seen among kids aged 3-5 years remains 43% below baseline.

“Even kids 0-2 years old are still down 30% from baseline,” he pointed out.

It’s possible that kids are getting care from other sources or perhaps are not sick as often because they are not in school. However, he added, “I do think there’s a concern that some kids are not getting the care they need for chronic illnesses such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, asthma, eczema, and psoriasis, and vaccination rates have fallen.”

Telemedicine rates dropping

Telemedicine was “supposed to have its shining moment,” Dr. Mehrotra said, but trends show it cannot make up the gaps of in-person care. His team’s data show a decline in telemedicine as a percentage of all visits from a high of 13.8% in mid-April to 7.4% the week of June 14.

He attributes that partially to physicians’ mixed success in getting reimbursed. “While Medicare has done a good job reimbursing, commercial payers and Medicaid plans have been mixed in their coverage.”

Some physicians who don’t get reimbursed or receive delayed or reduced payments are going back to in-person visits, Dr. Mehrotra said.

He said it’s important to remember that, before the pandemic, “telemedicine was making up 0.1% of all visits. Even if now it declines (from the April high of 13.8%) to 5% or 3%, that’s still a 30-fold increase within the course of a couple of months.”

Prospective payments would help expand the possibilities for telemedicine, he said, and could include apps and wearables and texts in addition to or instead of traditional video sessions.

Dr. Mehrotra said change won’t come fast enough for some and many practices won’t survive. “People are worried about their livelihood. This is nothing we’ve ever – at least in my career as a physician – had to focus on. Now we’re really having practices ask whether they can financially sustain themselves.”

For many, he said, the damage will be long term. “That cumulative deficit in visits – I’m not sure if it’s ever coming back. If you’re a primary care practice, you can only work so hard.”

Dr. Basu reported receiving a salary for clinical duties from HealthRIGHT360, a Federally Qualified Health Center, and Collective Health, a care management organization. Dr. Horn and Dr. Mehrotra reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally on Medscape.com.

Primary care practices stand to lose almost $68,000 per full-time physician this year as COVID-19 causes care delays and cancellations, researchers estimate. And while some outpatient care has started to rebound to near baseline appointment levels, other ambulatory specialties remain dramatically down from prepandemic rates.

For primary care practices, Sanjay Basu, MD, and colleagues calculated the losses at $67,774 in gross revenue per physician (interquartile range, $80,577-$54,990), with a national toll of $15.1 billion this year.

That’s without a potential second wave of COVID-19, noted Dr. Basu, director of research and population health at Collective Health in San Francisco, and colleagues.

When they added a theoretical stay-at-home order for November and December, the estimated loss climbed to $85,666 in gross revenue per full-time physician, with a loss of $19.1 billion nationally. The findings were published online in Health Affairs.

Meanwhile, clinical losses from canceled outpatient care are piling up as well, according to a study by Ateev Mehrotra, MD, associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues, which calculated the clinical losses in outpatient care.

“The ‘cumulative deficit’ in visits over the last 3 months (March 15 to June 20) is nearly 40%,” the authors wrote. They reported their findings in an article published online June 25 by the Commonwealth Fund.

When examined by specialty, Dr. Mehrotra and colleagues found that appointment rebound rates have been uneven. Whereas dermatology and rheumatology visits have already recovered, a couple of specialties have cumulative deficits that are particularly concerning. For example, pediatric visits were down by 47% in the 3 months since March 15 and pulmonology visits were down 45% in that time.

Much depends on the future of telehealth

Closing the financial and care gaps will depend largely on changing payment models for outpatient care and assuring adequate and enduring reimbursement for telehealth, according to experts.

COVID-19 has put a spotlight on the fragility of a fee-for-service system that depends on in-person visits for stability, Daniel Horn, MD, director of population health and quality at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview.

Several things need to happen to change the outlook for outpatient care, he said.

A need mentioned in both studies is that the COVID-19 waivers that make it possible for telehealth visits to be reimbursed like other visits must continue after the pandemic. Those assurances are critical as practices decide whether to invest in telemedicine.

If U.S. practices revert as of Oct. 1, 2020, to the pre–COVID-19 payment system for telehealth, national losses for the year would be more than double the current estimates.

“Given the number of active primary care physicians (n = 223,125), we estimated that the cost would be $38.7 billion (IQR, $31.1 billion-$48.3 billion) at a national level to neutralize the gross revenue losses caused by COVID-19 among primary care practices, without subjecting staff to furloughs,” Dr. Basu and colleagues wrote.

In addition to stabilizing telehealth payment models, another need to improve the outlook for outpatient care is more effective communication that in-person care is safe again in regions with protocols in place, Dr. Horn said.

However, the most important change, Dr. Horn said, is a switch to prospective lump-sum payments – payments made in advance to physicians to treat each patient in the way they and the patient deem best with the most appropriate appointment type – whether by in-person visit, phone call, text reminders, or video session.

Prospective payments would take multipayer coalitions working in conjunction with leadership on the federal level from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, Dr. Horn said. Commercial payers and states (through Medicaid funds) should already have that money available with the cancellations of nonessential procedures, he said.

“We expect ongoing turbulent times, so having a prospective payment could unleash the capacity for primary care practices to be creative in the way they care for their patients,” Dr. Horn said.

Visit trends still down

Calculations by Dr. Basu, who is also on the faculty at Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care, and colleagues were partially informed by Dr. Mehrotra’s data on how many visits have been lost because of COVID-19.

Dr. Mehrotra said a clear message in their study is that “visit trends are not back to baseline.”

They found that the number of visits to ambulatory practices had dropped nearly 60% by early April. Since then, numbers have rebounded substantially. As of the week of June 14, overall visits, compared with baseline were down 11%. But the drops varied widely across specialties.

Dr. Mehrotra said he found particularly disturbing the drop in pediatric visits and the sharp contrast between those rates and the higher number of visits for adults. While visits for patients aged 75 and older had climbed back to just 3% below baseline, the drop seen among kids aged 3-5 years remains 43% below baseline.

“Even kids 0-2 years old are still down 30% from baseline,” he pointed out.

It’s possible that kids are getting care from other sources or perhaps are not sick as often because they are not in school. However, he added, “I do think there’s a concern that some kids are not getting the care they need for chronic illnesses such as attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, asthma, eczema, and psoriasis, and vaccination rates have fallen.”

Telemedicine rates dropping

Telemedicine was “supposed to have its shining moment,” Dr. Mehrotra said, but trends show it cannot make up the gaps of in-person care. His team’s data show a decline in telemedicine as a percentage of all visits from a high of 13.8% in mid-April to 7.4% the week of June 14.

He attributes that partially to physicians’ mixed success in getting reimbursed. “While Medicare has done a good job reimbursing, commercial payers and Medicaid plans have been mixed in their coverage.”

Some physicians who don’t get reimbursed or receive delayed or reduced payments are going back to in-person visits, Dr. Mehrotra said.

He said it’s important to remember that, before the pandemic, “telemedicine was making up 0.1% of all visits. Even if now it declines (from the April high of 13.8%) to 5% or 3%, that’s still a 30-fold increase within the course of a couple of months.”

Prospective payments would help expand the possibilities for telemedicine, he said, and could include apps and wearables and texts in addition to or instead of traditional video sessions.

Dr. Mehrotra said change won’t come fast enough for some and many practices won’t survive. “People are worried about their livelihood. This is nothing we’ve ever – at least in my career as a physician – had to focus on. Now we’re really having practices ask whether they can financially sustain themselves.”

For many, he said, the damage will be long term. “That cumulative deficit in visits – I’m not sure if it’s ever coming back. If you’re a primary care practice, you can only work so hard.”

Dr. Basu reported receiving a salary for clinical duties from HealthRIGHT360, a Federally Qualified Health Center, and Collective Health, a care management organization. Dr. Horn and Dr. Mehrotra reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally on Medscape.com.

Primary care practices stand to lose almost $68,000 per full-time physician this year as COVID-19 causes care delays and cancellations, researchers estimate. And while some outpatient care has started to rebound to near baseline appointment levels, other ambulatory specialties remain dramatically down from prepandemic rates.

For primary care practices, Sanjay Basu, MD, and colleagues calculated the losses at $67,774 in gross revenue per physician (interquartile range, $80,577-$54,990), with a national toll of $15.1 billion this year.

That’s without a potential second wave of COVID-19, noted Dr. Basu, director of research and population health at Collective Health in San Francisco, and colleagues.

When they added a theoretical stay-at-home order for November and December, the estimated loss climbed to $85,666 in gross revenue per full-time physician, with a loss of $19.1 billion nationally. The findings were published online in Health Affairs.

Meanwhile, clinical losses from canceled outpatient care are piling up as well, according to a study by Ateev Mehrotra, MD, associate professor of health care policy and medicine at Harvard Medical School in Boston, and colleagues, which calculated the clinical losses in outpatient care.

“The ‘cumulative deficit’ in visits over the last 3 months (March 15 to June 20) is nearly 40%,” the authors wrote. They reported their findings in an article published online June 25 by the Commonwealth Fund.

When examined by specialty, Dr. Mehrotra and colleagues found that appointment rebound rates have been uneven. Whereas dermatology and rheumatology visits have already recovered, a couple of specialties have cumulative deficits that are particularly concerning. For example, pediatric visits were down by 47% in the 3 months since March 15 and pulmonology visits were down 45% in that time.

Much depends on the future of telehealth

Closing the financial and care gaps will depend largely on changing payment models for outpatient care and assuring adequate and enduring reimbursement for telehealth, according to experts.

COVID-19 has put a spotlight on the fragility of a fee-for-service system that depends on in-person visits for stability, Daniel Horn, MD, director of population health and quality at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in an interview.

Several things need to happen to change the outlook for outpatient care, he said.

A need mentioned in both studies is that the COVID-19 waivers that make it possible for telehealth visits to be reimbursed like other visits must continue after the pandemic. Those assurances are critical as practices decide whether to invest in telemedicine.

If U.S. practices revert as of Oct. 1, 2020, to the pre–COVID-19 payment system for telehealth, national losses for the year would be more than double the current estimates.

“Given the number of active primary care physicians (n = 223,125), we estimated that the cost would be $38.7 billion (IQR, $31.1 billion-$48.3 billion) at a national level to neutralize the gross revenue losses caused by COVID-19 among primary care practices, without subjecting staff to furloughs,” Dr. Basu and colleagues wrote.

In addition to stabilizing telehealth payment models, another need to improve the outlook for outpatient care is more effective communication that in-person care is safe again in regions with protocols in place, Dr. Horn said.