User login

Clinical Psychiatry News is the online destination and multimedia properties of Clinica Psychiatry News, the independent news publication for psychiatrists. Since 1971, Clinical Psychiatry News has been the leading source of news and commentary about clinical developments in psychiatry as well as health care policy and regulations that affect the physician's practice.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

ketamine

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

suicide

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-cpn')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Six healthy lifestyle habits linked to slowed memory decline

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

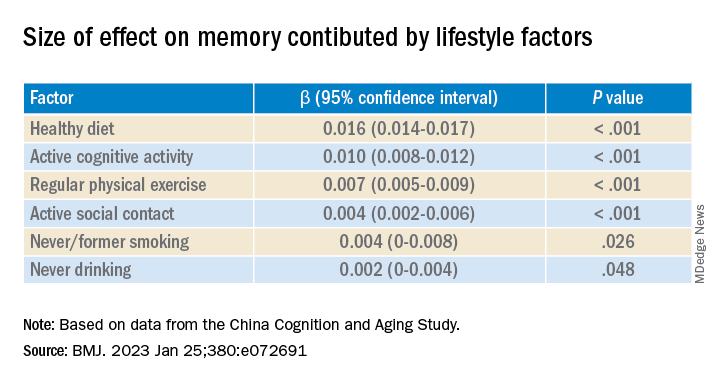

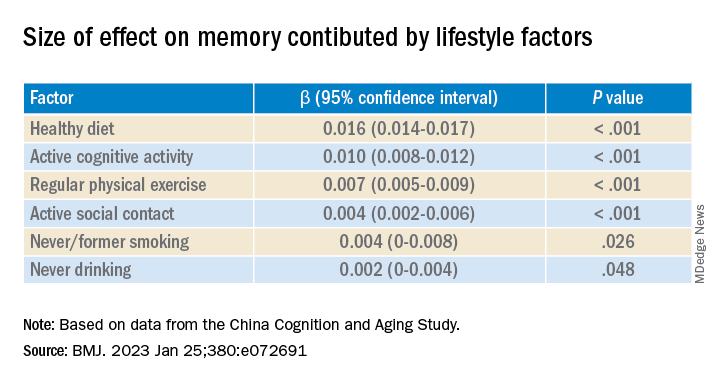

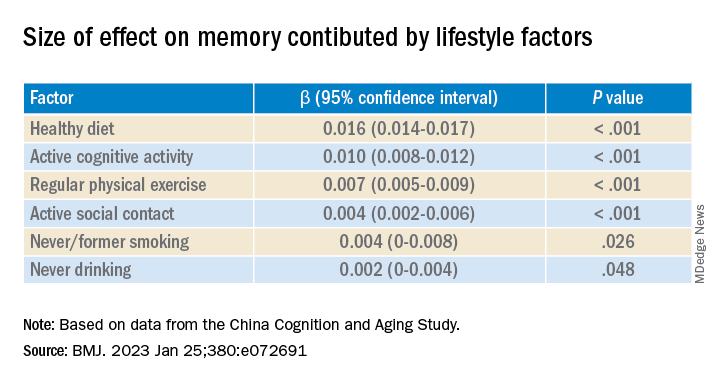

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

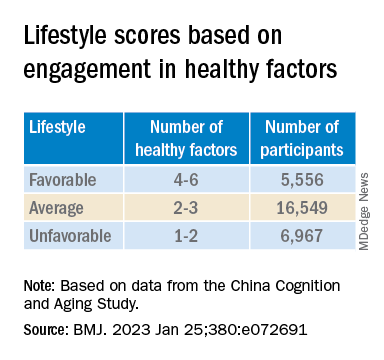

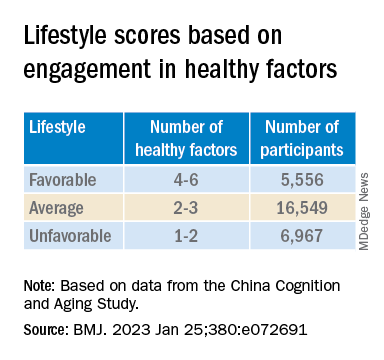

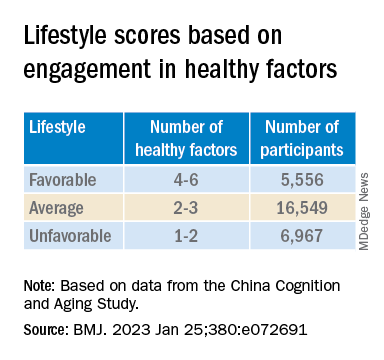

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Investigators found that a healthy diet, cognitive activity, regular physical exercise, not smoking, and abstaining from alcohol were significantly linked to slowed cognitive decline irrespective of APOE4 status.

After adjusting for health and socioeconomic factors, investigators found that each individual healthy behavior was associated with a slower-than-average decline in memory over a decade. A healthy diet emerged as the strongest deterrent, followed by cognitive activity and physical exercise.

“A healthy lifestyle is associated with slower memory decline, even in the presence of the APOE4 allele,” study investigators led by Jianping Jia, MD, PhD, of the Innovation Center for Neurological Disorders and the department of neurology, Xuan Wu Hospital, Capital Medical University, Beijing, write.

“This study might offer important information to protect older adults against memory decline,” they add.

The study was published online in the BMJ.

Preventing memory decline

Memory “continuously declines as people age,” but age-related memory decline is not necessarily a prodrome of dementia and can “merely be senescent forgetfulness,” the investigators note. This can be “reversed or [can] become stable,” instead of progressing to a pathologic state.

Factors affecting memory include aging, APOE4 genotype, chronic diseases, and lifestyle patterns, with lifestyle “receiving increasing attention as a modifiable behavior.”

Nevertheless, few studies have focused on the impact of lifestyle on memory, and those that have are mostly cross-sectional and also “did not consider the interaction between a healthy lifestyle and genetic risk,” the researchers note.

To investigate, the researchers conducted a longitudinal study, known as the China Cognition and Aging Study, that considered genetic risk as well as lifestyle factors.

The study began in 2009 and concluded in 2019. Participants were evaluated and underwent neuropsychological testing in 2012, 2014, 2016, and at the study’s conclusion.

Participants (n = 29,072; mean [SD] age, 72.23 [6.61] years; 48.54% women; 20.43% APOE4 carriers) were required to have normal cognitive function at baseline. Data on those whose condition progressed to mild cognitive impairment (MCI) or dementia during the follow-up period were excluded after their diagnosis.

The Mini–Mental State Examination was used to assess global cognitive function. Memory function was assessed using the World Health Organization/University of California, Los Angeles Auditory Verbal Learning Test.

“Lifestyle” consisted of six modifiable factors: physical exercise (weekly frequency and total time), smoking (current, former, or never-smokers), alcohol consumption (never drank, drank occasionally, low to excess drinking, and heavy drinking), diet (daily intake of 12 food items: fruits, vegetables, fish, meat, dairy products, salt, oil, eggs, cereals, legumes, nuts, tea), cognitive activity (writing, reading, playing cards, mahjong, other games), and social contact (participating in meetings, attending parties, visiting friends/relatives, traveling, chatting online).

Participants’ lifestyles were scored on the basis of the number of healthy factors they engaged in.

Participants were also stratified by APOE genotype into APOE4 carriers and noncarriers.

Demographic and other items of health information, including the presence of medical illness, were used as covariates. The researchers also included the “learning effect of each participant as a covariate, due to repeated cognitive assessments.”

Important for public health

During the 10-year period, 7,164 participants died, and 3,567 stopped participating.

Participants in the favorable and average groups showed slower memory decline per increased year of age (0.007 [0.005-0.009], P < .001; and 0.002 [0 .000-0.003], P = .033 points higher, respectively), compared with those in the unfavorable group.

Healthy diet had the strongest protective effect on memory.

Memory decline occurred faster in APOE4 vesus non-APOE4 carriers (0.002 points/year [95% confidence interval, 0.001-0.003]; P = .007).

But APOE4 carriers with favorable and average lifestyles showed slower memory decline (0.027 [0.023-0.031] and 0.014 [0.010-0.019], respectively), compared with those with unfavorable lifestyles. Similar findings were obtained in non-APOE4 carriers.

Those with favorable or average lifestyle were respectively almost 90% and 30% less likely to develop dementia or MCI, compared with those with an unfavorable lifestyle.

The authors acknowledge the study’s limitations, including its observational design and the potential for measurement errors, owing to self-reporting of lifestyle factors. Additionally, some participants did not return for follow-up evaluations, leading to potential selection bias.

Nevertheless, the findings “might offer important information for public health to protect older [people] against memory decline,” they note – especially since the study “provides evidence that these effects also include individuals with the APOE4 allele.”

‘Important, encouraging’ research

In a comment, Severine Sabia, PhD, a senior researcher at the Université Paris Cité, INSERM Institut National de la Santé et de la Recherche Medicalé, France, called the findings “important and encouraging.”

However, said Dr. Sabia, who was not involved with the study, “there remain important research questions that need to be investigated in order to identify key behaviors: which combination, the cutoff of risk, and when to intervene.”

Future research on prevention “should examine a wider range of possible risk factors” and should also “identify specific exposures associated with the greatest risk, while also considering the risk threshold and age at exposure for each one.”

In an accompanying editorial, Dr. Sabia and co-author Archana Singh-Manoux, PhD, note that the risk of cognitive decline and dementia are probably determined by multiple factors.

They liken it to the “multifactorial risk paradigm introduced by the Framingham study,” which has “led to a substantial reduction in cardiovascular disease.” A similar approach could be used with dementia prevention, they suggest.

The authors received support from the Xuanwu Hospital of Capital Medical University for the submitted work. One of the authors received a grant from the French National Research Agency. The other authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Sabia received grant funding from the French National Research Agency. Dr. Singh-Manoux received grants from the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE BMJ

Even one head injury boosts all-cause mortality risk

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

An analysis of more than 13,000 adult participants in the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study showed a dose-response pattern in which one head injury was linked to a 66% increased risk for all-cause mortality, and two or more head injuries were associated with twice the risk in comparison with no head injuries.

These findings underscore the importance of preventing head injuries and of swift clinical intervention once a head injury occurs, lead author Holly Elser, MD, PhD, department of neurology, Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, told this news organization.

“Clinicians should counsel patients who are at risk for falls about head injuries and ensure patients are promptly evaluated in the hospital setting if they do have a fall – especially with loss of consciousness or other symptoms, such as headache or dizziness,” Dr. Elser added.

The findings were published online in JAMA Neurology.

Consistent evidence

There is “pretty consistent evidence” that mortality rates are increased in the short term after head injury, predominantly among hospitalized patients, Dr. Elser noted.

“But there’s less evidence about the long-term mortality implications of head injuries and less evidence from adults living in the community,” she added.

The analysis included 13,037 participants in the ARIC study, an ongoing study involving adults aged 45-65 years who were recruited from four geographically and racially diverse U.S. communities. The mean age at baseline (1987-1989) was 54 years; 57.7% were women; and 27.9% were Black.

Study participants are followed at routine in-person visits and semiannually via telephone.

Data on head injuries came from hospital diagnostic codes and self-reports. These reports included information on the number of injuries and whether the injury required medical care and involved loss of consciousness.

During the 27-year follow-up, 18.4% of the study sample had at least one head injury. Injuries occurred more frequently among women, which may reflect the predominance of women in the study population, said Dr. Elser.

Overall, about 56% of participants died during the study period. The estimated median amount of survival time after head injury was 4.7 years.

The most common causes of death were neoplasm, cardiovascular disease, and neurologic disorders. Regarding specific neurologic causes of death, the researchers found that 62.2% of deaths were due to neurodegenerative disease among individuals with head injury, vs. 51.4% among those without head injury.

This, said Dr. Elser, raises the possibility of reverse causality. “If you have a neurodegenerative disorder like Alzheimer’s disease dementia or Parkinson’s disease that leads to difficulty walking, you may be more likely to fall and have a head injury. The head injury in turn may lead to increased mortality,” she noted.

However, she stressed that the data on cause-specific mortality are exploratory. “Our research motivates future studies that really examine this time-dependent relationship between neurodegenerative disease and head injuries,” Dr. Elser said.

Dose-dependent response

In the unadjusted analysis, the hazard ratio of mortality among individuals with head injury was 2.21 (95% confidence interval, 2.09-2.34) compared with those who did not have head injury.

The association remained significant with adjustment for sociodemographic factors (HR, 1.99; 95% CI, 1.88-2.11) and with additional adjustment for vascular risk factors (HR, 1.92; 95% CI, 1.81-2.03).

The findings also showed a dose-response pattern in the association of head injuries with mortality. Compared with participants who did not have head injury, the HR was 1.66 (95% CI, 1.56-1.77) for those with one head injury and 2.11 (95% CI, 1.89-2.37) for those with two or more head injuries.

“It’s not as though once you’ve had one head injury, you’ve accrued all the damage you possibly can. We see pretty clearly here that recurrent head injury further increased the rate of deaths from all causes,” said Dr. Elser.

Injury severity was determined from hospital diagnostic codes using established algorithms. Results showed that mortality rates were increased with even mild head injury.

Interestingly, the association between head injury and all-cause mortality was weaker among those whose injuries were self-reported. One possibility is that these injuries were less severe, Dr. Elser noted.

“If you have head injury that’s mild enough that you don’t need to go to the hospital, it’s probably going to confer less long-term health risks than one that’s severe enough that you needed to be examined in an acute care setting,” she said.

Results were similar by race and for sex. “Even though there were more women with head injuries, the rate of mortality associated with head injury doesn’t differ from the rate among men,” Dr. Elser reported.

However, the association was stronger among those younger than 54 years at baseline (HR, 2.26) compared with older individuals (HR, 2.0) in the model that adjusted for demographics and lifestyle factors.

This may be explained by the reference group (those without a head injury) – the mortality rate was in general higher for the older participants, said Dr. Elser. It could also be that younger adults are more likely to have severe head injuries from, for example, motor vehicle accidents or violence, she added.

These new findings underscore the importance of public health measures, such as seatbelt laws, to reduce head injuries, the investigators note.

They add that clinicians with patients at risk for head injuries may recommend steps to lessen the risk of falls, such as having access to durable medical equipment, and ensuring driver safety.

Shorter life span

Commenting for this news organization, Frank Conidi, MD, director of the Florida Center for Headache and Sports Neurology in Port St. Lucie and past president of the Florida Society of Neurology, said the large number of participants “adds validity” to the finding that individuals with head injury are likely to have a shorter life span than those who do not suffer head trauma – and that this “was not purely by chance or from other causes.”

However, patients may not have accurately reported head injuries, in which case the rate of injury in the self-report subgroup would not reflect the actual incidence, noted Dr. Conidi, who was not involved with the research.

“In my practice, most patients have little knowledge as to the signs and symptoms of concussion and traumatic brain injury. Most think there needs to be some form of loss of consciousness to have a head injury, which is of course not true,” he said.

Dr. Conidi added that the finding of a higher incidence of death from neurodegenerative disorders supports the generally accepted consensus view that about 30% of patients with traumatic brain injury experience progression of symptoms and are at risk for early dementia.

The ARIC study is supported by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Dr. Elser and Dr. Conidi have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NEUROLOGY

Don’t cross the friends line with patients

All that moving can make it hard to maintain friendships. Factor in the challenges from the pandemic, and a physician’s life can be lonely. So, when a patient invites you for coffee or a game of pickleball, do you accept? For almost one-third of the physicians who responded to the Medscape Physician Friendships: The Joys and Challenges 2022, the answer might be yes.

About 29% said they develop friendships with patients. However, a lot depends on the circumstances. As one physician in the report said: “I have been a pediatrician for 35 years, and my patients have grown up and become productive adults in our small, rural, isolated area. You can’t help but know almost everyone.”

As the daughter of a cardiologist, Nishi Mehta, MD, a radiologist and founder of the largest physician-only Facebook group in the country, grew up with that small-town-everyone-knows-the-doctor model.

“When I was a kid, I’d go to the mall, and my friends and I would play a game: How long before a patient [of my dad’s] comes up to me?” she said. At the time, Dr. Mehta was embarrassed, but now she marvels that her dad knew his patients so well that they would recognize his daughter in crowded suburban mall.

In other instances, a physician may develop a friendly relationship after a patient leaves their care. For example, Leo Nissola, MD, now a full-time researcher and immunotherapy scientist in San Francisco, has stayed in touch with some of the patients he treated while at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Dr. Nissola said it was important to stay connected with the patients he had meaningful relationships with. “It becomes challenging, though, when a former patient asks for medical advice.” At that moment, “you have to be explicitly clear that the relationship has changed.”

A hard line in the sand

The blurring of lines is one reason many doctors refuse to befriend patients, even after they are no longer treating them. The American College of Physicians Ethics Manual advises against treating anyone with whom you have a close relationship, including family and friends.

“Friendships can get in the way of patients being honest with you, which can interfere with medical care,” Dr. Mehta said. “If a patient has a concern related to something they wouldn’t want you to know as friends, it can get awkward. They may elect not to tell you.”

And on the flip side, friendship can provide a view into your private life that you may not welcome in the exam room.

“Let’s say you go out for drinks [with a patient], and you’re up late, but you have surgery the next day,” said Brandi Ring, MD, an ob.gyn. and the associate medical director at the Center for Children and Women in Houston. Now, one of your patients knows you were out until midnight when you had to be in the OR at 5:00 a.m.

Worse still, your relationship could color your decisions about a patient’s care, even unconsciously. It can be hard to maintain objectivity when you have an emotional investment in someone’s well-being.

“We don’t necessarily treat family and friends to the standards of medical care,” said Dr. Ring. “We go above and beyond. We might order more tests and more scans. We don’t always follow the guidelines, especially in critical illness.”

For all these reasons and more, the ACP advises against treating friends.

Put physician before friend

But adhering to those guidelines can lead physicians to make some painful decisions. Cutting yourself off from the possibility of friendship is never easy, and the Medscape report found that physicians tend to have fewer friends than the average American.

“Especially earlier in my practice, when I was a young parent, and I would see a lot of other young parents in the same stage in life, I’d think, ‘In other circumstances, I would be hanging out at the park with this person,’ “ said Kathleen Rowland, MD, a family medicine physician and vice chair of education in the department of family medicine at Rush University, Chicago. “But the hard part is, the doctor-patient relationship always comes first.”

To a certain extent, one’s specialty may determine the feasibility of becoming friends with a patient. While Dr. Mehta has never done so, as a radiologist, she doesn’t usually see patients repeatedly. Likewise, a young gerontologist may have little in common with his octogenarian patients. And an older pediatrician is not in the same life stage as his patients’ sleep-deprived new parents, possibly making them less attractive friends.

However, practicing family medicine is all about long-term physician-patient relationships. Getting to know patients and their families over many years can lead to a certain intimacy. Dr. Rowland said that, while a wonderful part of being a physician is getting that unique trust whereby patients tell you all sorts of things about their lives, she’s never gone down the friendship path.

“There’s the assumption I’ll take care of someone for a long period of time, and their partner and their kids, maybe another generation or two,” Dr. Rowland said. “People really do rely on that relationship to contribute to their health.”

Worse, nowadays, when people may be starved for connection, many patients want to feel emotionally close and cared for by their doctor, so it’d be easy to cross the line. While patients deserve a compassionate, caring doctor, the physician is left to walk the line between those boundaries. Dr. Rowland said, “It’s up to the clinician to say: ‘My role is as a doctor. You deserve caring friends, but I have to order your mammogram and your blood counts. My role is different.’ ”

Friendly but not friends

It can be tricky to navigate the boundary between a cordial, warm relationship with a patient and that patient inviting you to their daughter’s wedding.

“People may mistake being pleasant and friendly for being friends,” said Larry Blosser, MD, chief medical officer at Central Ohio Primary Care, Westerville. In his position, he sometimes hears from patients who have misunderstood their relationship with a doctor in the practice. When that happens, he advises the physician to consider the persona they’re presenting to the patient. If you’re overly friendly, there’s the potential for confusion, but you can’t be aloof and cold, he said.

Maintaining that awareness helps to prevent a patient’s offhand invitation to catch a movie or go on a hike. And verbalizing it to your patients can make your relationship clear from the get-go.

“I tell patients we’re a team. I’m the captain, and they’re my MVP. When the match is over, whatever the results, we’re done,” said Karenne Fru, MD, PhD, a fertility specialist at Oma Fertility Atlanta. Making deep connections is essential to her practice, so Dr. Fru structures her patient interactions carefully. “Infertility is such an isolating experience. While you’re with us, we care about what’s going on in your life, your pets, and your mom’s chemo. We need mutual trust for you to be compliant with the care.”

However, that approach won’t work when you see patients regularly, as with family practice or specialties that see the same patients repeatedly throughout the year. In those circumstances, the match is never over but one in which the onus is on the physician to establish a friendly yet professional rapport without letting your self-interest, loneliness, or lack of friends interfere.

“It’s been a very difficult couple of years for a lot of us. Depending on what kind of clinical work we do, some of us took care of healthy people that got very sick or passed away,” Dr. Rowland said. “Having the chance to reconnect with people and reestablish some of that closeness, both physical and emotional, is going to be good for us.”

Just continue conveying warm, trusting compassion for your patients without blurring the friend lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All that moving can make it hard to maintain friendships. Factor in the challenges from the pandemic, and a physician’s life can be lonely. So, when a patient invites you for coffee or a game of pickleball, do you accept? For almost one-third of the physicians who responded to the Medscape Physician Friendships: The Joys and Challenges 2022, the answer might be yes.

About 29% said they develop friendships with patients. However, a lot depends on the circumstances. As one physician in the report said: “I have been a pediatrician for 35 years, and my patients have grown up and become productive adults in our small, rural, isolated area. You can’t help but know almost everyone.”

As the daughter of a cardiologist, Nishi Mehta, MD, a radiologist and founder of the largest physician-only Facebook group in the country, grew up with that small-town-everyone-knows-the-doctor model.

“When I was a kid, I’d go to the mall, and my friends and I would play a game: How long before a patient [of my dad’s] comes up to me?” she said. At the time, Dr. Mehta was embarrassed, but now she marvels that her dad knew his patients so well that they would recognize his daughter in crowded suburban mall.

In other instances, a physician may develop a friendly relationship after a patient leaves their care. For example, Leo Nissola, MD, now a full-time researcher and immunotherapy scientist in San Francisco, has stayed in touch with some of the patients he treated while at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Dr. Nissola said it was important to stay connected with the patients he had meaningful relationships with. “It becomes challenging, though, when a former patient asks for medical advice.” At that moment, “you have to be explicitly clear that the relationship has changed.”

A hard line in the sand

The blurring of lines is one reason many doctors refuse to befriend patients, even after they are no longer treating them. The American College of Physicians Ethics Manual advises against treating anyone with whom you have a close relationship, including family and friends.

“Friendships can get in the way of patients being honest with you, which can interfere with medical care,” Dr. Mehta said. “If a patient has a concern related to something they wouldn’t want you to know as friends, it can get awkward. They may elect not to tell you.”

And on the flip side, friendship can provide a view into your private life that you may not welcome in the exam room.

“Let’s say you go out for drinks [with a patient], and you’re up late, but you have surgery the next day,” said Brandi Ring, MD, an ob.gyn. and the associate medical director at the Center for Children and Women in Houston. Now, one of your patients knows you were out until midnight when you had to be in the OR at 5:00 a.m.

Worse still, your relationship could color your decisions about a patient’s care, even unconsciously. It can be hard to maintain objectivity when you have an emotional investment in someone’s well-being.

“We don’t necessarily treat family and friends to the standards of medical care,” said Dr. Ring. “We go above and beyond. We might order more tests and more scans. We don’t always follow the guidelines, especially in critical illness.”

For all these reasons and more, the ACP advises against treating friends.

Put physician before friend

But adhering to those guidelines can lead physicians to make some painful decisions. Cutting yourself off from the possibility of friendship is never easy, and the Medscape report found that physicians tend to have fewer friends than the average American.

“Especially earlier in my practice, when I was a young parent, and I would see a lot of other young parents in the same stage in life, I’d think, ‘In other circumstances, I would be hanging out at the park with this person,’ “ said Kathleen Rowland, MD, a family medicine physician and vice chair of education in the department of family medicine at Rush University, Chicago. “But the hard part is, the doctor-patient relationship always comes first.”

To a certain extent, one’s specialty may determine the feasibility of becoming friends with a patient. While Dr. Mehta has never done so, as a radiologist, she doesn’t usually see patients repeatedly. Likewise, a young gerontologist may have little in common with his octogenarian patients. And an older pediatrician is not in the same life stage as his patients’ sleep-deprived new parents, possibly making them less attractive friends.

However, practicing family medicine is all about long-term physician-patient relationships. Getting to know patients and their families over many years can lead to a certain intimacy. Dr. Rowland said that, while a wonderful part of being a physician is getting that unique trust whereby patients tell you all sorts of things about their lives, she’s never gone down the friendship path.

“There’s the assumption I’ll take care of someone for a long period of time, and their partner and their kids, maybe another generation or two,” Dr. Rowland said. “People really do rely on that relationship to contribute to their health.”

Worse, nowadays, when people may be starved for connection, many patients want to feel emotionally close and cared for by their doctor, so it’d be easy to cross the line. While patients deserve a compassionate, caring doctor, the physician is left to walk the line between those boundaries. Dr. Rowland said, “It’s up to the clinician to say: ‘My role is as a doctor. You deserve caring friends, but I have to order your mammogram and your blood counts. My role is different.’ ”

Friendly but not friends

It can be tricky to navigate the boundary between a cordial, warm relationship with a patient and that patient inviting you to their daughter’s wedding.

“People may mistake being pleasant and friendly for being friends,” said Larry Blosser, MD, chief medical officer at Central Ohio Primary Care, Westerville. In his position, he sometimes hears from patients who have misunderstood their relationship with a doctor in the practice. When that happens, he advises the physician to consider the persona they’re presenting to the patient. If you’re overly friendly, there’s the potential for confusion, but you can’t be aloof and cold, he said.

Maintaining that awareness helps to prevent a patient’s offhand invitation to catch a movie or go on a hike. And verbalizing it to your patients can make your relationship clear from the get-go.

“I tell patients we’re a team. I’m the captain, and they’re my MVP. When the match is over, whatever the results, we’re done,” said Karenne Fru, MD, PhD, a fertility specialist at Oma Fertility Atlanta. Making deep connections is essential to her practice, so Dr. Fru structures her patient interactions carefully. “Infertility is such an isolating experience. While you’re with us, we care about what’s going on in your life, your pets, and your mom’s chemo. We need mutual trust for you to be compliant with the care.”

However, that approach won’t work when you see patients regularly, as with family practice or specialties that see the same patients repeatedly throughout the year. In those circumstances, the match is never over but one in which the onus is on the physician to establish a friendly yet professional rapport without letting your self-interest, loneliness, or lack of friends interfere.

“It’s been a very difficult couple of years for a lot of us. Depending on what kind of clinical work we do, some of us took care of healthy people that got very sick or passed away,” Dr. Rowland said. “Having the chance to reconnect with people and reestablish some of that closeness, both physical and emotional, is going to be good for us.”

Just continue conveying warm, trusting compassion for your patients without blurring the friend lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

All that moving can make it hard to maintain friendships. Factor in the challenges from the pandemic, and a physician’s life can be lonely. So, when a patient invites you for coffee or a game of pickleball, do you accept? For almost one-third of the physicians who responded to the Medscape Physician Friendships: The Joys and Challenges 2022, the answer might be yes.

About 29% said they develop friendships with patients. However, a lot depends on the circumstances. As one physician in the report said: “I have been a pediatrician for 35 years, and my patients have grown up and become productive adults in our small, rural, isolated area. You can’t help but know almost everyone.”

As the daughter of a cardiologist, Nishi Mehta, MD, a radiologist and founder of the largest physician-only Facebook group in the country, grew up with that small-town-everyone-knows-the-doctor model.

“When I was a kid, I’d go to the mall, and my friends and I would play a game: How long before a patient [of my dad’s] comes up to me?” she said. At the time, Dr. Mehta was embarrassed, but now she marvels that her dad knew his patients so well that they would recognize his daughter in crowded suburban mall.

In other instances, a physician may develop a friendly relationship after a patient leaves their care. For example, Leo Nissola, MD, now a full-time researcher and immunotherapy scientist in San Francisco, has stayed in touch with some of the patients he treated while at the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston.

Dr. Nissola said it was important to stay connected with the patients he had meaningful relationships with. “It becomes challenging, though, when a former patient asks for medical advice.” At that moment, “you have to be explicitly clear that the relationship has changed.”

A hard line in the sand

The blurring of lines is one reason many doctors refuse to befriend patients, even after they are no longer treating them. The American College of Physicians Ethics Manual advises against treating anyone with whom you have a close relationship, including family and friends.

“Friendships can get in the way of patients being honest with you, which can interfere with medical care,” Dr. Mehta said. “If a patient has a concern related to something they wouldn’t want you to know as friends, it can get awkward. They may elect not to tell you.”

And on the flip side, friendship can provide a view into your private life that you may not welcome in the exam room.

“Let’s say you go out for drinks [with a patient], and you’re up late, but you have surgery the next day,” said Brandi Ring, MD, an ob.gyn. and the associate medical director at the Center for Children and Women in Houston. Now, one of your patients knows you were out until midnight when you had to be in the OR at 5:00 a.m.

Worse still, your relationship could color your decisions about a patient’s care, even unconsciously. It can be hard to maintain objectivity when you have an emotional investment in someone’s well-being.

“We don’t necessarily treat family and friends to the standards of medical care,” said Dr. Ring. “We go above and beyond. We might order more tests and more scans. We don’t always follow the guidelines, especially in critical illness.”

For all these reasons and more, the ACP advises against treating friends.

Put physician before friend

But adhering to those guidelines can lead physicians to make some painful decisions. Cutting yourself off from the possibility of friendship is never easy, and the Medscape report found that physicians tend to have fewer friends than the average American.

“Especially earlier in my practice, when I was a young parent, and I would see a lot of other young parents in the same stage in life, I’d think, ‘In other circumstances, I would be hanging out at the park with this person,’ “ said Kathleen Rowland, MD, a family medicine physician and vice chair of education in the department of family medicine at Rush University, Chicago. “But the hard part is, the doctor-patient relationship always comes first.”

To a certain extent, one’s specialty may determine the feasibility of becoming friends with a patient. While Dr. Mehta has never done so, as a radiologist, she doesn’t usually see patients repeatedly. Likewise, a young gerontologist may have little in common with his octogenarian patients. And an older pediatrician is not in the same life stage as his patients’ sleep-deprived new parents, possibly making them less attractive friends.

However, practicing family medicine is all about long-term physician-patient relationships. Getting to know patients and their families over many years can lead to a certain intimacy. Dr. Rowland said that, while a wonderful part of being a physician is getting that unique trust whereby patients tell you all sorts of things about their lives, she’s never gone down the friendship path.

“There’s the assumption I’ll take care of someone for a long period of time, and their partner and their kids, maybe another generation or two,” Dr. Rowland said. “People really do rely on that relationship to contribute to their health.”

Worse, nowadays, when people may be starved for connection, many patients want to feel emotionally close and cared for by their doctor, so it’d be easy to cross the line. While patients deserve a compassionate, caring doctor, the physician is left to walk the line between those boundaries. Dr. Rowland said, “It’s up to the clinician to say: ‘My role is as a doctor. You deserve caring friends, but I have to order your mammogram and your blood counts. My role is different.’ ”

Friendly but not friends

It can be tricky to navigate the boundary between a cordial, warm relationship with a patient and that patient inviting you to their daughter’s wedding.

“People may mistake being pleasant and friendly for being friends,” said Larry Blosser, MD, chief medical officer at Central Ohio Primary Care, Westerville. In his position, he sometimes hears from patients who have misunderstood their relationship with a doctor in the practice. When that happens, he advises the physician to consider the persona they’re presenting to the patient. If you’re overly friendly, there’s the potential for confusion, but you can’t be aloof and cold, he said.

Maintaining that awareness helps to prevent a patient’s offhand invitation to catch a movie or go on a hike. And verbalizing it to your patients can make your relationship clear from the get-go.

“I tell patients we’re a team. I’m the captain, and they’re my MVP. When the match is over, whatever the results, we’re done,” said Karenne Fru, MD, PhD, a fertility specialist at Oma Fertility Atlanta. Making deep connections is essential to her practice, so Dr. Fru structures her patient interactions carefully. “Infertility is such an isolating experience. While you’re with us, we care about what’s going on in your life, your pets, and your mom’s chemo. We need mutual trust for you to be compliant with the care.”

However, that approach won’t work when you see patients regularly, as with family practice or specialties that see the same patients repeatedly throughout the year. In those circumstances, the match is never over but one in which the onus is on the physician to establish a friendly yet professional rapport without letting your self-interest, loneliness, or lack of friends interfere.

“It’s been a very difficult couple of years for a lot of us. Depending on what kind of clinical work we do, some of us took care of healthy people that got very sick or passed away,” Dr. Rowland said. “Having the chance to reconnect with people and reestablish some of that closeness, both physical and emotional, is going to be good for us.”

Just continue conveying warm, trusting compassion for your patients without blurring the friend lines.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatricians, specialists largely agree on ASD diagnoses

General pediatricians and a multidisciplinary team of specialists agreed most of the time on which children should be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), data from a new study suggest.

But when it came to ruling out ASD, the agreement rate was much lower.

The study by Melanie Penner, MSc, MD, with the Autism Research Centre at Bloorview Research Institute, Toronto, and colleagues found that 89% of the time when a physician determined a child had ASD, the multidisciplinary team agreed. But when a pediatrician thought a child did not have ASD, the multidisciplinary team agreed only 60% of the time. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Multidisciplinary team model can’t keep up with demand

The findings are important as many guidelines recommend multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) for all ASD diagnostic assessment. However, the resources for this model can’t meet the demand of children needing a diagnosis and can lead to long waits for ASD therapies.

In Canada, the researchers note, the average wait time from referral to receipt of ASD diagnosis has been reported as 7 months and “has likely lengthened since the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Jennifer Gerdts, PhD, an attending psychologist at the Seattle Children’s Autism Center, said in an interview that the wait there for diagnosis in children older than 4 is “multiple years,” a length of time that’s common across the United States. Meanwhile, in many states families can’t access services without a diagnosis.

Expanding capacity with diagnoses by general pediatricians may improve access, but the diagnostic accuracy is critical.

Dr. Gerdts, who was not part of the study, said this research is “hugely important in the work that is under way to build community capacity for diagnostic evaluation.”

She said this study shows that not all diagnoses need the resources of a multiple-disciplinary team and that “pediatricians can do it, too, and they can do it pretty accurately.” Dr. Gerdts evaluates children for autism and helps train pediatricians to make diagnoses.

Pediatricians, specialist team completed blinded assessments

The 17 pediatricians in the study and the specialist team independently completed blinded assessment and each recorded a decision on whether the child had ASD. The prospective diagnostic study was conducted in a specialist assessment center in Toronto and in general pediatrician practices in Ontario from June 2016 to March 2020.

Children were younger than 5.5 years, did not have an ASD diagnosis and were referred because there was a development concern. The pediatricians referred 106 children (75% boys; average age, 3.5 years). More than half (57%) of the participating children were from minority racial and ethnic groups.

The children were randomly assigned to two groups: One included children who had their MDT visits before their pediatrician assessment and the other group included those who had their MDT visits after their pediatrician assessment.

The MDT diagnosed more than two-thirds of the children (68%) with ASD.

Sensitivity and specificity of the pediatrician assessments, compared with that of the specialist team, were 0.75 (95% confidence interval, 0.67-0.83) and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.62-0.91), respectively.

A look at pediatricians’ accuracy

Pediatricians reported the decisions they would have made had the child not been in the study.

- In 69% of the true-positive cases, pediatricians would have given an ASD diagnosis.

- In 44% of true-negative cases, they would have told the family the child did not have autism; in 30% of those case, they would give alternative diagnoses (most commonly ADHD and language delay).

- The pediatrician would have diagnosed ASD in only one of the seven false-positive cases and would refer those patients to a subspecialist 71% of the time.

- In false-negative cases, the pediatrician would incorrectly tell the family the child does not have autism 44% of the time.

Regarding the false-negative cases, the authors wrote, “more caution is needed for pediatricians when definitively ruling out ASD, which might result in diagnostic delays.”

Confidence is key

Physician confidence was also correlated with accuracy.

The authors wrote: “Among true-positive cases (MDT and pediatrician agree the child has ASD), the pediatrician was certain or very certain 80% of the time (43 cases) and the MDT was certain or very certain 96% of the time (52 cases). As such, if pediatricians conferred ASD diagnoses when feeling certain or very certain, they would make 46 correct diagnoses and 2 incorrect diagnoses.”

The high accuracy of diagnosis when physicians are confident suggests “listening to that sense of certainty is important,” Dr. Gerdts said. Conversely, these numbers show when a physician is uncertain about diagnosing ASD, they should listen to that instinct, too, and refer.

The results of the study support having general pediatricians diagnose and move forward with their patients when the signs of ASD are more definitive, saving the less-certain cases for the more resource-intensive teams to diagnose. Many states are moving toward that “tiered” system, Dr. Gerdts said.

“For many, and in fact most children, general pediatricians are pretty accurate when making an autism diagnosis,” she said.

“Let’s get [general pediatricians] confident in recognizing when this is outside their skill and ability level,” she said. “If you’re not sure, it is better to refer them on than to misdiagnose them.”

The important missing piece she said is how to support them “so they don’t feel pressure to make that call,” Dr. Gerdts said.

This project was funded by a grant from the Bloorview Research Institute, a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and a grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health. Three coauthors consult for and receive grants from several pharmaceutical companies and other organizations. Dr. Gerdts declared no relevant financial relationships.

General pediatricians and a multidisciplinary team of specialists agreed most of the time on which children should be diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD), data from a new study suggest.

But when it came to ruling out ASD, the agreement rate was much lower.

The study by Melanie Penner, MSc, MD, with the Autism Research Centre at Bloorview Research Institute, Toronto, and colleagues found that 89% of the time when a physician determined a child had ASD, the multidisciplinary team agreed. But when a pediatrician thought a child did not have ASD, the multidisciplinary team agreed only 60% of the time. The study was published in JAMA Network Open.

Multidisciplinary team model can’t keep up with demand

The findings are important as many guidelines recommend multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) for all ASD diagnostic assessment. However, the resources for this model can’t meet the demand of children needing a diagnosis and can lead to long waits for ASD therapies.

In Canada, the researchers note, the average wait time from referral to receipt of ASD diagnosis has been reported as 7 months and “has likely lengthened since the COVID-19 pandemic.”

Jennifer Gerdts, PhD, an attending psychologist at the Seattle Children’s Autism Center, said in an interview that the wait there for diagnosis in children older than 4 is “multiple years,” a length of time that’s common across the United States. Meanwhile, in many states families can’t access services without a diagnosis.

Expanding capacity with diagnoses by general pediatricians may improve access, but the diagnostic accuracy is critical.

Dr. Gerdts, who was not part of the study, said this research is “hugely important in the work that is under way to build community capacity for diagnostic evaluation.”

She said this study shows that not all diagnoses need the resources of a multiple-disciplinary team and that “pediatricians can do it, too, and they can do it pretty accurately.” Dr. Gerdts evaluates children for autism and helps train pediatricians to make diagnoses.

Pediatricians, specialist team completed blinded assessments

The 17 pediatricians in the study and the specialist team independently completed blinded assessment and each recorded a decision on whether the child had ASD. The prospective diagnostic study was conducted in a specialist assessment center in Toronto and in general pediatrician practices in Ontario from June 2016 to March 2020.

Children were younger than 5.5 years, did not have an ASD diagnosis and were referred because there was a development concern. The pediatricians referred 106 children (75% boys; average age, 3.5 years). More than half (57%) of the participating children were from minority racial and ethnic groups.

The children were randomly assigned to two groups: One included children who had their MDT visits before their pediatrician assessment and the other group included those who had their MDT visits after their pediatrician assessment.

The MDT diagnosed more than two-thirds of the children (68%) with ASD.

Sensitivity and specificity of the pediatrician assessments, compared with that of the specialist team, were 0.75 (95% confidence interval, 0.67-0.83) and 0.79 (95% CI, 0.62-0.91), respectively.

A look at pediatricians’ accuracy

Pediatricians reported the decisions they would have made had the child not been in the study.

- In 69% of the true-positive cases, pediatricians would have given an ASD diagnosis.

- In 44% of true-negative cases, they would have told the family the child did not have autism; in 30% of those case, they would give alternative diagnoses (most commonly ADHD and language delay).

- The pediatrician would have diagnosed ASD in only one of the seven false-positive cases and would refer those patients to a subspecialist 71% of the time.

- In false-negative cases, the pediatrician would incorrectly tell the family the child does not have autism 44% of the time.

Regarding the false-negative cases, the authors wrote, “more caution is needed for pediatricians when definitively ruling out ASD, which might result in diagnostic delays.”

Confidence is key

Physician confidence was also correlated with accuracy.