User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

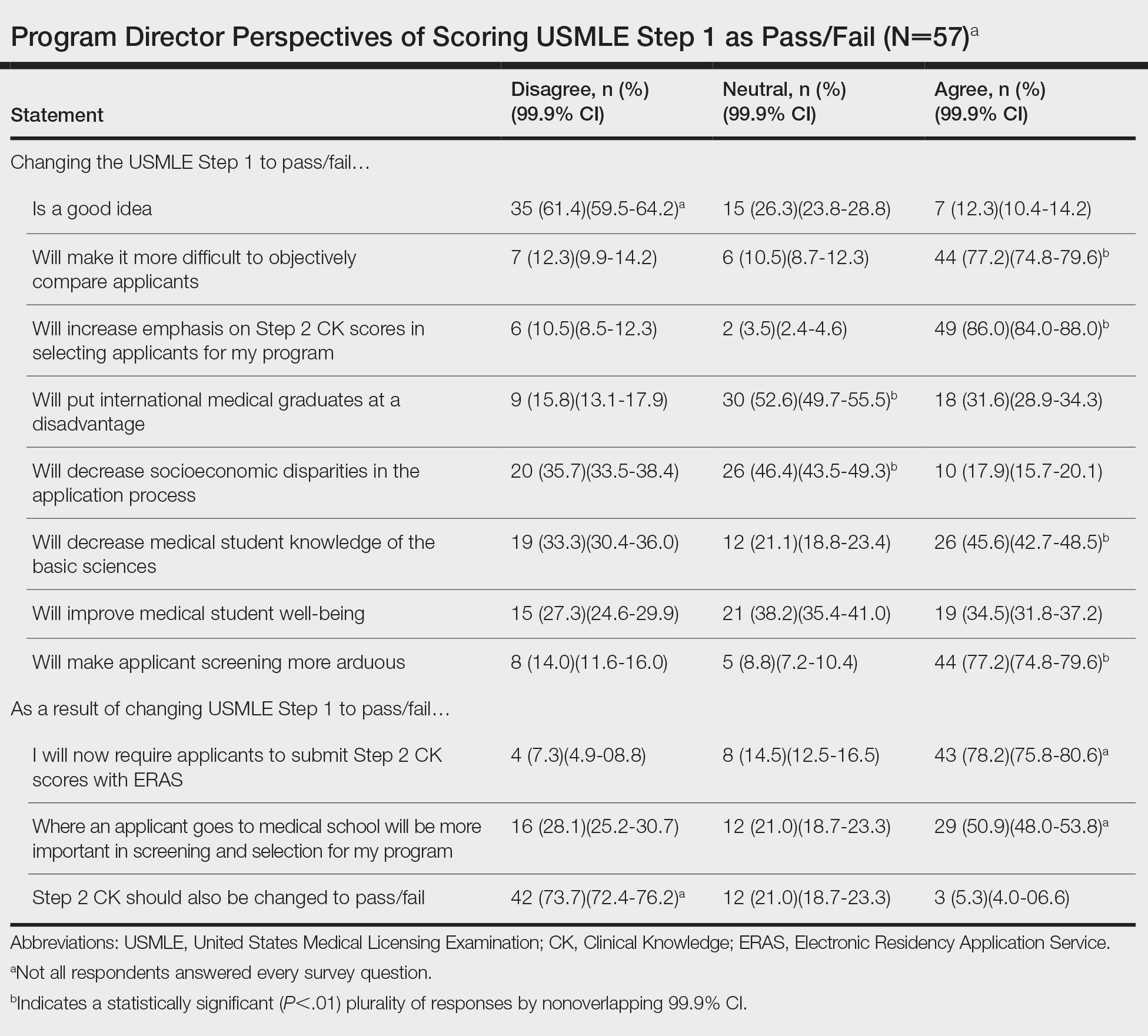

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Nivolumab-Induced Granuloma Annulare

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a benign, cutaneous, granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. Typically, GA presents in young adults as asymptomatic, annular, flesh-colored to pink papules and plaques, commonly on the upper and lower extremities. Histologically, GA is characterized by mucin deposition, palisading or an interstitial granulomatous pattern, and collagen and elastic fiber degeneration.1

Granuloma annulare has been associated with various medications and medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, and HIV.1 More recently, immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been reported to trigger GA.2 We report a case of nivolumab-induced GA in a 54-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with an itchy rash on the upper extremities, face, and chest of 4 months’ duration. The patient noted that the rash started on the hands and progressed to include the arms, face, and chest. She also reported associated mild tenderness. She had a history of stage IV non–small-cell lung carcinoma with metastases to the ribs and adrenal glands. She had been started on biweekly intravenous infusions of the ICI nivolumab by her oncologist approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation after failing a course of conventional chemotherapy. The most recent positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan 1 month prior to presentation showed a stable lung mass with radiologic disappearance of metastases, indicating a favorable response to nivolumab. The patient also had a history of hypothyroidism and depression, which were treated with oral levothyroxine 75 μg once daily and oral sertraline 50 mg once daily, respectively, both for longer than 5 years.

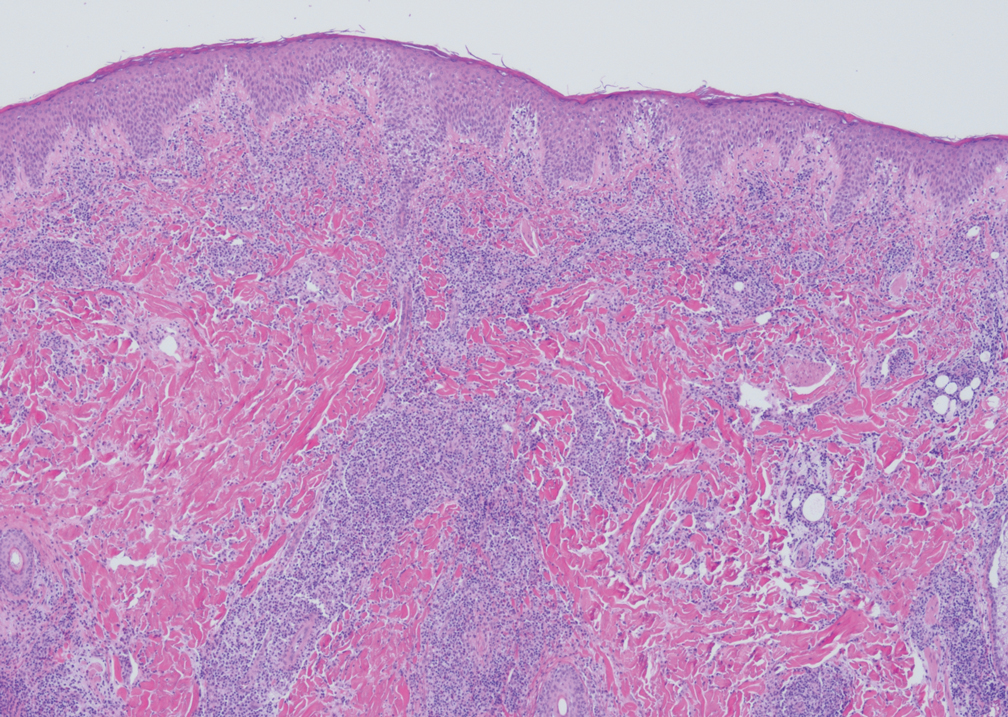

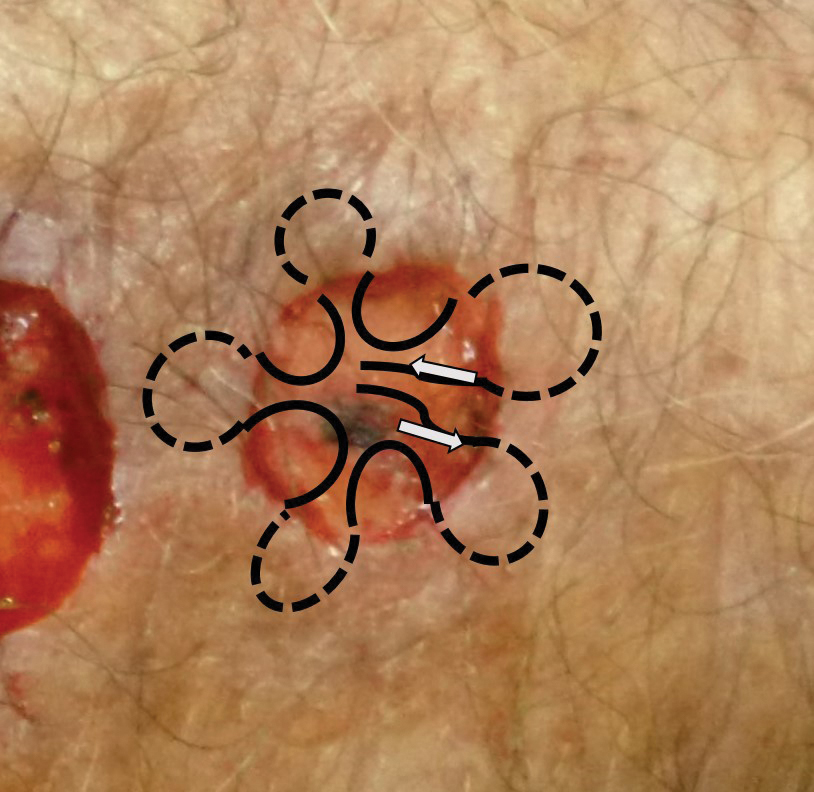

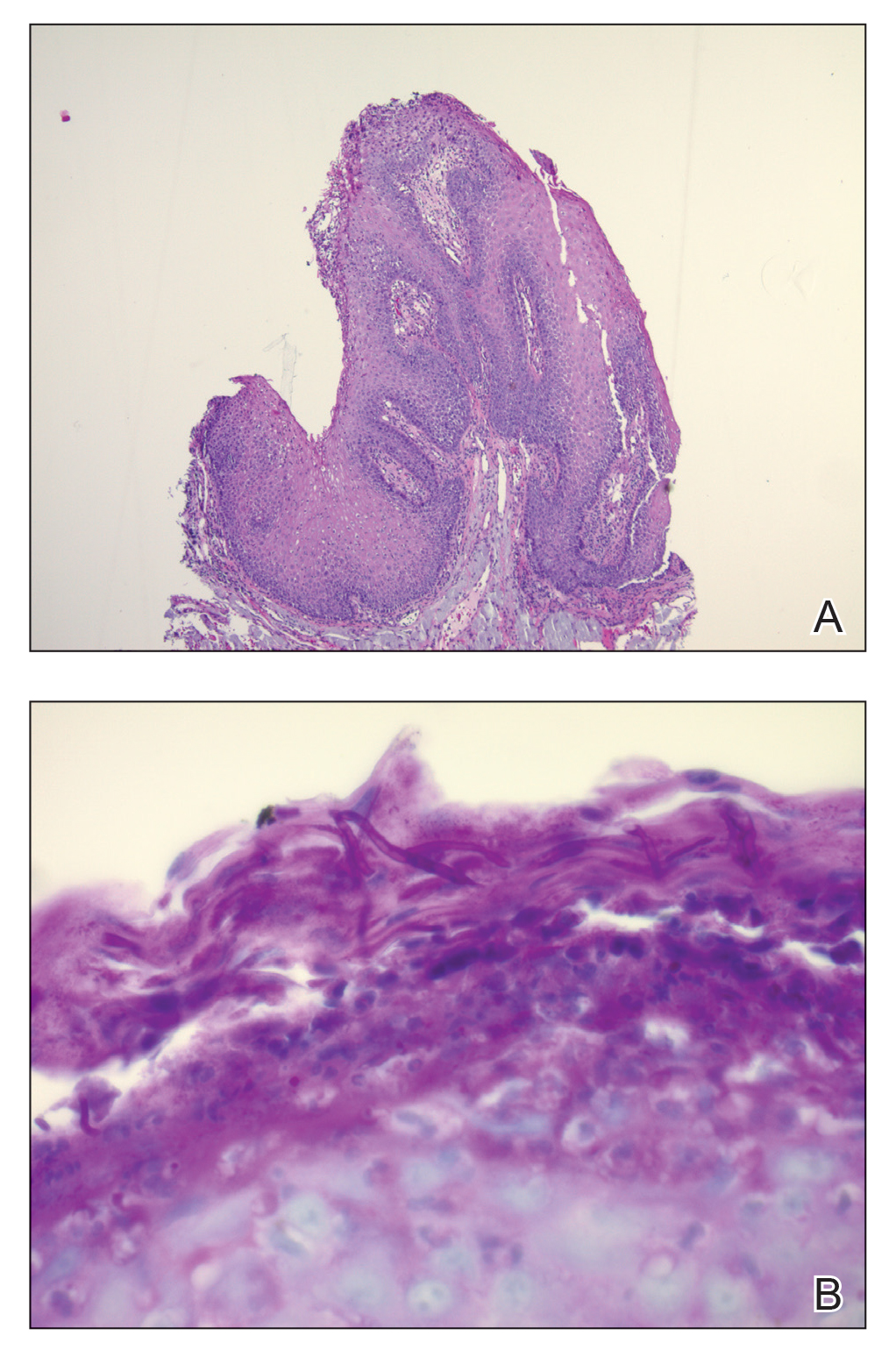

Physical examination revealed annular, erythematous, flat-topped papules, some with surmounting fine scale, coalescing into larger plaques along the dorsal surface of the hands and arms (Figure 1) as well as the forehead and chest. A biopsy of a papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed nodules of histiocytes admixed with Langerhans giant cells within the dermis; mucin was noted centrally within some nodules (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements compared to control. Polarization of the specimen was negative for foreign bodies. The biopsy findings therefore were consistent with a diagnosis of GA.

A 3-month treatment course of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream twice daily failed. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was then initiated at 3 sessions weekly. The eruption of GA improved after 3 months of phototherapy. Subsequently, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Discovery of specific immune checkpoints in tumor-induced immunosuppression revolutionized oncologic therapy. An example is the programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that is expressed on activated immune cells, including T cells and macrophages.3,4 Upon binding to the PD-1 ligand (PD-L1), T-cell proliferation is inhibited, resulting in downregulation of the immune response. As a result, tumor cells have evolved to overexpress PD-L1 to evade immunologic detection.3 Nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 antibody to PD-1, has emerged along with other ICIs as effective treatments for numerous cancers, including melanoma and non–small-cell lung cancer. By disrupting downregulation of T cells, ICIs improve immune-mediated antitumor activity.3

However, the resulting immunologic disturbance by ICIs has been reported to induce various cutaneous and systemic immune-mediated adverse reactions, including granulomatous reactions such as sarcoidosis, GA, and a cutaneous sarcoidlike granulomatous reaction.1,2,5,6 Our patient represents a rare case of nivolumab-induced GA.

Recent evidence suggests that GA might be caused in part by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction that is regulated by a helper T cell subset 1 inflammatory reaction. Through release of cytokines by activated CD4+ T cells, macrophages are recruited, forming the granulomatous pattern and secreting enzymes that can degrade connective tissue. Nivolumab and other ICIs can thus trigger this reaction because their blockade of PD-1 enhances T cell–mediated immune reactions.2 In addition, because macrophages themselves also express PD-1, ICIs can directly enhance macrophage recruitment and proliferation, further increasing the risk of a granulomatous reaction.4

Interestingly, cutaneous adverse reactions to nivolumab have been associated with improved survival in melanoma patients.7 The nature of this association with granulomatous reactions in general and with GA specifically remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Since the approval of the first PD-1 inhibitors, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, in 2014, other ICIs targeting the immune checkpoint pathway have been developed. Newer agents targeting PD-L1 (avelumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab) were recently approved. Additionally, cemiplimab, another PD-1 inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for the treatment of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.8 Indications for all ICIs also have expanded considerably.3 Therefore, the incidence of immune-mediated adverse reactions, including GA, is bound to increase. Physicians should be cognizant of this association to accurately diagnose and effectively treat adverse reactions in patients who are taking ICIs.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.055

- Wu J, Kwong BY, Martires KJ, et al. Granuloma annulare associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2018;32:E124-E126. doi:10.1111/jdv.14617

- Gong J, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Reddi S, et al. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:8. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0316-z

- Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;545:495-499. doi:10.1038/nature22396

- Birnbaum MR, Ma MW, Fleisig S, et al. Nivolumab-related cutaneous sarcoidosis in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:208-211. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.02.015

- Danlos F-X, Pagès C, Baroudjian B, et al. Nivolumab-induced sarcoid-like granulomatous reaction in a patient with advanced melanoma. Chest. 2016;149:E133-E136. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.10.082

- Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, et al. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:886-894. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1136

- Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, et al. PD-1 blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:341-351. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1805131

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a benign, cutaneous, granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. Typically, GA presents in young adults as asymptomatic, annular, flesh-colored to pink papules and plaques, commonly on the upper and lower extremities. Histologically, GA is characterized by mucin deposition, palisading or an interstitial granulomatous pattern, and collagen and elastic fiber degeneration.1

Granuloma annulare has been associated with various medications and medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, and HIV.1 More recently, immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been reported to trigger GA.2 We report a case of nivolumab-induced GA in a 54-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with an itchy rash on the upper extremities, face, and chest of 4 months’ duration. The patient noted that the rash started on the hands and progressed to include the arms, face, and chest. She also reported associated mild tenderness. She had a history of stage IV non–small-cell lung carcinoma with metastases to the ribs and adrenal glands. She had been started on biweekly intravenous infusions of the ICI nivolumab by her oncologist approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation after failing a course of conventional chemotherapy. The most recent positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan 1 month prior to presentation showed a stable lung mass with radiologic disappearance of metastases, indicating a favorable response to nivolumab. The patient also had a history of hypothyroidism and depression, which were treated with oral levothyroxine 75 μg once daily and oral sertraline 50 mg once daily, respectively, both for longer than 5 years.

Physical examination revealed annular, erythematous, flat-topped papules, some with surmounting fine scale, coalescing into larger plaques along the dorsal surface of the hands and arms (Figure 1) as well as the forehead and chest. A biopsy of a papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed nodules of histiocytes admixed with Langerhans giant cells within the dermis; mucin was noted centrally within some nodules (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements compared to control. Polarization of the specimen was negative for foreign bodies. The biopsy findings therefore were consistent with a diagnosis of GA.

A 3-month treatment course of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream twice daily failed. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was then initiated at 3 sessions weekly. The eruption of GA improved after 3 months of phototherapy. Subsequently, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Discovery of specific immune checkpoints in tumor-induced immunosuppression revolutionized oncologic therapy. An example is the programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that is expressed on activated immune cells, including T cells and macrophages.3,4 Upon binding to the PD-1 ligand (PD-L1), T-cell proliferation is inhibited, resulting in downregulation of the immune response. As a result, tumor cells have evolved to overexpress PD-L1 to evade immunologic detection.3 Nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 antibody to PD-1, has emerged along with other ICIs as effective treatments for numerous cancers, including melanoma and non–small-cell lung cancer. By disrupting downregulation of T cells, ICIs improve immune-mediated antitumor activity.3

However, the resulting immunologic disturbance by ICIs has been reported to induce various cutaneous and systemic immune-mediated adverse reactions, including granulomatous reactions such as sarcoidosis, GA, and a cutaneous sarcoidlike granulomatous reaction.1,2,5,6 Our patient represents a rare case of nivolumab-induced GA.

Recent evidence suggests that GA might be caused in part by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction that is regulated by a helper T cell subset 1 inflammatory reaction. Through release of cytokines by activated CD4+ T cells, macrophages are recruited, forming the granulomatous pattern and secreting enzymes that can degrade connective tissue. Nivolumab and other ICIs can thus trigger this reaction because their blockade of PD-1 enhances T cell–mediated immune reactions.2 In addition, because macrophages themselves also express PD-1, ICIs can directly enhance macrophage recruitment and proliferation, further increasing the risk of a granulomatous reaction.4

Interestingly, cutaneous adverse reactions to nivolumab have been associated with improved survival in melanoma patients.7 The nature of this association with granulomatous reactions in general and with GA specifically remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Since the approval of the first PD-1 inhibitors, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, in 2014, other ICIs targeting the immune checkpoint pathway have been developed. Newer agents targeting PD-L1 (avelumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab) were recently approved. Additionally, cemiplimab, another PD-1 inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for the treatment of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.8 Indications for all ICIs also have expanded considerably.3 Therefore, the incidence of immune-mediated adverse reactions, including GA, is bound to increase. Physicians should be cognizant of this association to accurately diagnose and effectively treat adverse reactions in patients who are taking ICIs.

Granuloma annulare (GA) is a benign, cutaneous, granulomatous disease of unclear etiology. Typically, GA presents in young adults as asymptomatic, annular, flesh-colored to pink papules and plaques, commonly on the upper and lower extremities. Histologically, GA is characterized by mucin deposition, palisading or an interstitial granulomatous pattern, and collagen and elastic fiber degeneration.1

Granuloma annulare has been associated with various medications and medical conditions, including diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, thyroid disease, and HIV.1 More recently, immune-checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have been reported to trigger GA.2 We report a case of nivolumab-induced GA in a 54-year-old woman.

Case Report

A 54-year-old woman presented with an itchy rash on the upper extremities, face, and chest of 4 months’ duration. The patient noted that the rash started on the hands and progressed to include the arms, face, and chest. She also reported associated mild tenderness. She had a history of stage IV non–small-cell lung carcinoma with metastases to the ribs and adrenal glands. She had been started on biweekly intravenous infusions of the ICI nivolumab by her oncologist approximately 1 year prior to the current presentation after failing a course of conventional chemotherapy. The most recent positron emission tomography–computed tomography scan 1 month prior to presentation showed a stable lung mass with radiologic disappearance of metastases, indicating a favorable response to nivolumab. The patient also had a history of hypothyroidism and depression, which were treated with oral levothyroxine 75 μg once daily and oral sertraline 50 mg once daily, respectively, both for longer than 5 years.

Physical examination revealed annular, erythematous, flat-topped papules, some with surmounting fine scale, coalescing into larger plaques along the dorsal surface of the hands and arms (Figure 1) as well as the forehead and chest. A biopsy of a papule on the dorsal aspect of the left hand revealed nodules of histiocytes admixed with Langerhans giant cells within the dermis; mucin was noted centrally within some nodules (Figure 2). Periodic acid–Schiff staining was negative for fungal elements compared to control. Polarization of the specimen was negative for foreign bodies. The biopsy findings therefore were consistent with a diagnosis of GA.

A 3-month treatment course of betamethasone dipropionate 0.05% cream twice daily failed. Narrowband UVB phototherapy was then initiated at 3 sessions weekly. The eruption of GA improved after 3 months of phototherapy. Subsequently, the patient was lost to follow-up.

Comment

Discovery of specific immune checkpoints in tumor-induced immunosuppression revolutionized oncologic therapy. An example is the programmed cell-death protein 1 (PD-1) receptor that is expressed on activated immune cells, including T cells and macrophages.3,4 Upon binding to the PD-1 ligand (PD-L1), T-cell proliferation is inhibited, resulting in downregulation of the immune response. As a result, tumor cells have evolved to overexpress PD-L1 to evade immunologic detection.3 Nivolumab, a fully human IgG4 antibody to PD-1, has emerged along with other ICIs as effective treatments for numerous cancers, including melanoma and non–small-cell lung cancer. By disrupting downregulation of T cells, ICIs improve immune-mediated antitumor activity.3

However, the resulting immunologic disturbance by ICIs has been reported to induce various cutaneous and systemic immune-mediated adverse reactions, including granulomatous reactions such as sarcoidosis, GA, and a cutaneous sarcoidlike granulomatous reaction.1,2,5,6 Our patient represents a rare case of nivolumab-induced GA.

Recent evidence suggests that GA might be caused in part by a cell-mediated hypersensitivity reaction that is regulated by a helper T cell subset 1 inflammatory reaction. Through release of cytokines by activated CD4+ T cells, macrophages are recruited, forming the granulomatous pattern and secreting enzymes that can degrade connective tissue. Nivolumab and other ICIs can thus trigger this reaction because their blockade of PD-1 enhances T cell–mediated immune reactions.2 In addition, because macrophages themselves also express PD-1, ICIs can directly enhance macrophage recruitment and proliferation, further increasing the risk of a granulomatous reaction.4

Interestingly, cutaneous adverse reactions to nivolumab have been associated with improved survival in melanoma patients.7 The nature of this association with granulomatous reactions in general and with GA specifically remains to be determined.

Conclusion

Since the approval of the first PD-1 inhibitors, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, in 2014, other ICIs targeting the immune checkpoint pathway have been developed. Newer agents targeting PD-L1 (avelumab, atezolizumab, and durvalumab) were recently approved. Additionally, cemiplimab, another PD-1 inhibitor, was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2018 for the treatment of advanced cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma.8 Indications for all ICIs also have expanded considerably.3 Therefore, the incidence of immune-mediated adverse reactions, including GA, is bound to increase. Physicians should be cognizant of this association to accurately diagnose and effectively treat adverse reactions in patients who are taking ICIs.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.055

- Wu J, Kwong BY, Martires KJ, et al. Granuloma annulare associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2018;32:E124-E126. doi:10.1111/jdv.14617

- Gong J, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Reddi S, et al. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:8. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0316-z

- Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;545:495-499. doi:10.1038/nature22396

- Birnbaum MR, Ma MW, Fleisig S, et al. Nivolumab-related cutaneous sarcoidosis in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:208-211. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.02.015

- Danlos F-X, Pagès C, Baroudjian B, et al. Nivolumab-induced sarcoid-like granulomatous reaction in a patient with advanced melanoma. Chest. 2016;149:E133-E136. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.10.082

- Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, et al. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:886-894. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1136

- Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, et al. PD-1 blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:341-351. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1805131

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: pathogenesis, disease associations and triggers, and therapeutic options. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:467-479. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2015.03.055

- Wu J, Kwong BY, Martires KJ, et al. Granuloma annulare associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Eur Acad Dermatol. 2018;32:E124-E126. doi:10.1111/jdv.14617

- Gong J, Chehrazi-Raffle A, Reddi S, et al. Development of PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors as a form of cancer immunotherapy: a comprehensive review of registration trials and future considerations. J Immunother Cancer. 2018;6:8. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0316-z

- Gordon SR, Maute RL, Dulken BW, et al. PD-1 expression by tumour-associated macrophages inhibits phagocytosis and tumour immunity. Nature. 2017;545:495-499. doi:10.1038/nature22396

- Birnbaum MR, Ma MW, Fleisig S, et al. Nivolumab-related cutaneous sarcoidosis in a patient with lung adenocarcinoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2017;3:208-211. doi:10.1016/j.jdcr.2017.02.015

- Danlos F-X, Pagès C, Baroudjian B, et al. Nivolumab-induced sarcoid-like granulomatous reaction in a patient with advanced melanoma. Chest. 2016;149:E133-E136. doi:10.1016/j.chest.2015.10.082

- Freeman-Keller M, Kim Y, Cronin H, et al. Nivolumab in resected and unresectable metastatic melanoma: characteristics of immune-related adverse events and association with outcomes. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:886-894. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1136

- Migden MR, Rischin D, Schmults CD, et al. PD-1 blockade with cemiplimab in advanced cutaneous squamous-cell carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:341-351. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1805131

Practice Points

- Immune-related adverse events (irAEs) frequently occur in patients on immunotherapy, with the skin representing the most common site of involvement.

- Although rare, granulomatous reactions such as granuloma annulare increasingly are recognized as potential irAEs.

- Clinicians should be aware of this novel association to accurately diagnose and effectively treat adverse reactions in patients receiving immunotherapy.

Atopic Dermatitis

The Comparison

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-ofpocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016 /j.anai.2019.05.014

- Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016 /j.jid.2018.10.029

- Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

- Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

The Comparison

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-ofpocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

The Comparison

A Pink scaling plaques and erythematous erosions in the antecubital fossae of a 6-year-old White boy.

B Violaceous, hyperpigmented, nummular plaques on the back and extensor surface of the right arm of a 16-month-old Black girl.

C Atopic dermatitis and follicular prominence/accentuation on the neck of a young Black girl.

Epidemiology

People of African descent have the highest atopic dermatitis prevalence and severity.

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones include:

- follicular prominence

- papular morphology

- prurigo nodules

- hyperpigmented, violaceous-brown or gray plaques instead of erythematous plaques

- lichenification

- treatment resistant.1,2

Worth noting

Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation and postinflammatory hypopigmentation may be more distressing to the patient/family than the atopic dermatitis itself.

Health disparity highlight

In the United States, patients with skin of color are more likely to be hospitalized with severe atopic dermatitis, have more substantial out-ofpocket costs, be underinsured, and have an increased number of missed days of work. Limited access to outpatient health care plays a role in exacerbating this health disparity.3,4

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016 /j.anai.2019.05.014

- Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016 /j.jid.2018.10.029

- Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

- Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

- McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. The prevalence and persistence of atopic dermatitis in urban United States children. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:173-178.e1. doi:10.1016 /j.anai.2019.05.014

- Kim Y, Bloomberg M, Rifas-Shiman SL, et al. Racial/ethnic differences in incidence and persistence of childhood atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2019;139:827-834. doi:10.1016 /j.jid.2018.10.029

- Narla S, Hsu DY, Thyssen JP, et al. Predictors of hospitalization, length of stay, and costs of care among adult and pediatric inpatients with atopic dermatitis in the United States. Dermatitis. 2018;29:22-31. doi:10.1097/DER.0000000000000323

- Silverberg JI. Health care utilization, patient costs, and access to care in US adults with eczema. JAMA Dermatol. 2015;151:743-752. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2014.5432

Atrophic Lesions in a Pregnant Woman

The Diagnosis: Degos Disease

The pathophysiology of Degos disease (malignant atrophic papulosis) is unknown.1 Histopathology demonstrates a wedge-shaped area of dermal necrosis with edema and mucin deposition extending from the papillary dermis to the deep reticular dermis. Occluded vessels, thrombosis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates also may be seen, particularly at the dermal subcutaneous junction and at the periphery of the wedge-shaped infarction. The vascular damage that occurs may be the result of vasculitis, coagulopathy, or endothelial cell dysfunction.1

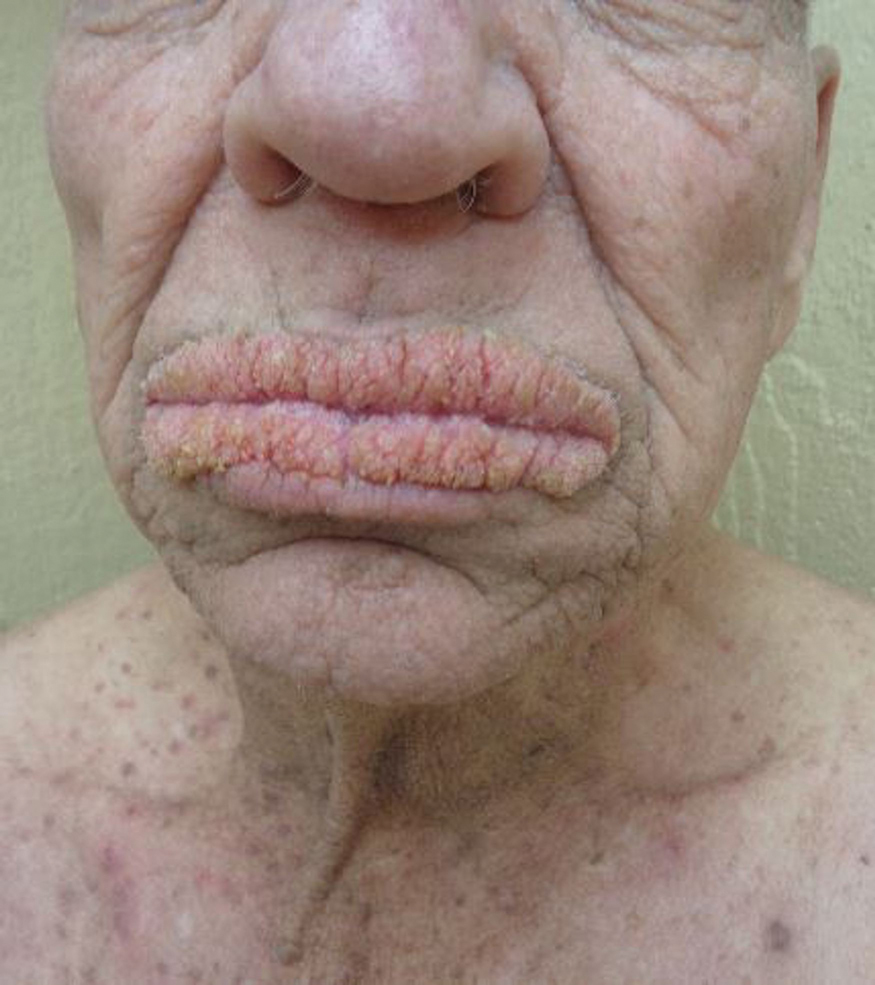

Patients typically present with small, round, erythematous papules that eventually develop atrophic porcelain white centers and telangiectatic rims. These lesions most commonly occur on the trunk and arms. In the benign form of atrophic papulosis, only the skin is involved; however, systemic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system can occur, resulting in bowel perforation and stroke, respectively.1 Although there is no definitive treatment of Degos disease, successful therapy with aspirin or dipyridamole has been reported.1 Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds C5, and treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog, are emerging treatment options.2,3 The differential diagnosis of Degos disease may include granuloma annulare, guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus, livedoid vasculopathy, and lymphomatoid papulosis.

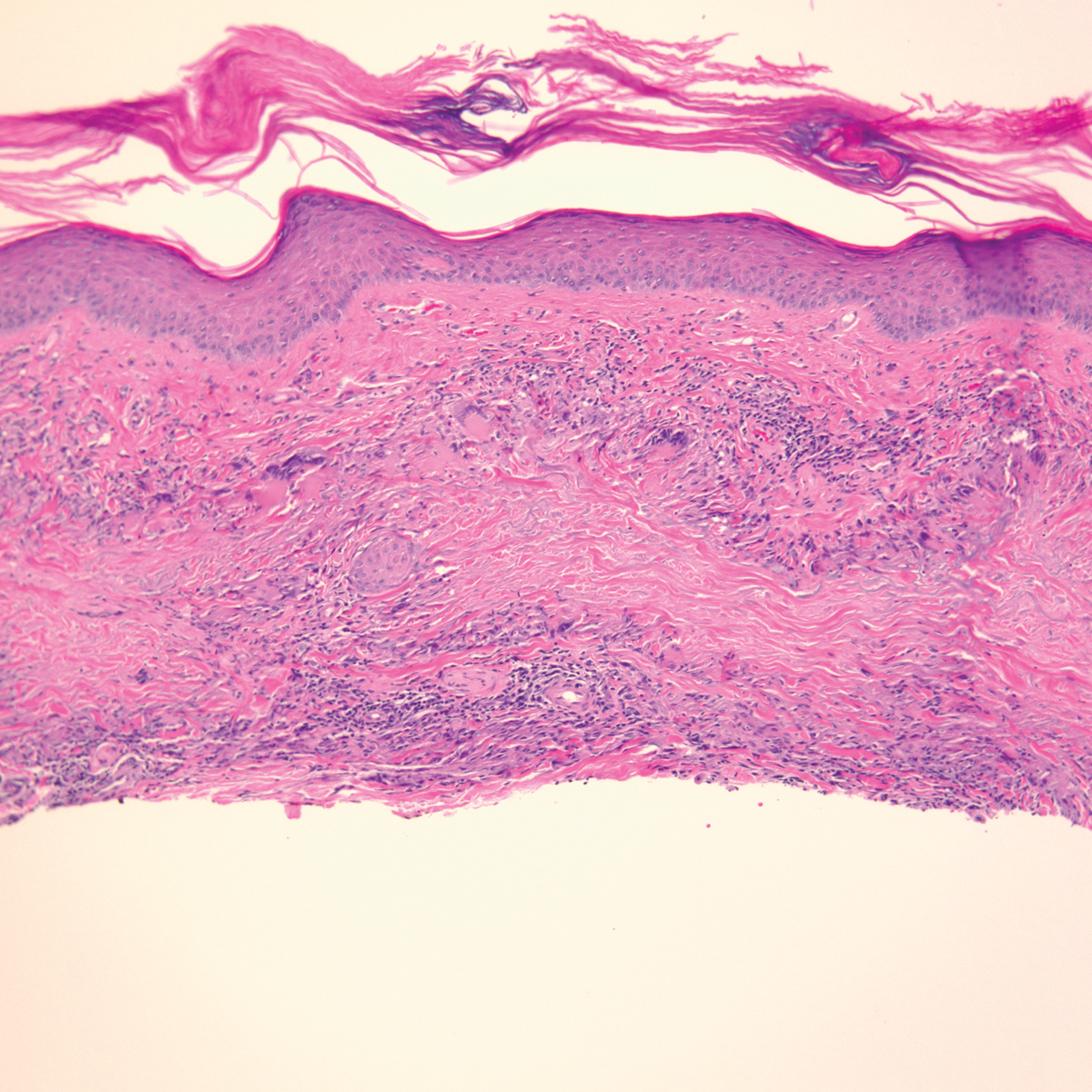

Granuloma annulare may clinically mimic the erythematous papules seen in early Degos disease, and histopathology can be used to distinguish between these two disease processes. Localized granuloma annulare is the most common variant and clinically presents as pink papules and plaques in an annular configuration.4 Histopathology demonstrates an unremarkable epidermis; however, the dermis contains degenerated collagen surrounded by palisading histiocytes as well as lymphocytes. Similar to Degos disease, increased mucin is seen within these areas of degeneration, but occluded vessels and thrombosis typically are not seen (Figure 1).4,5

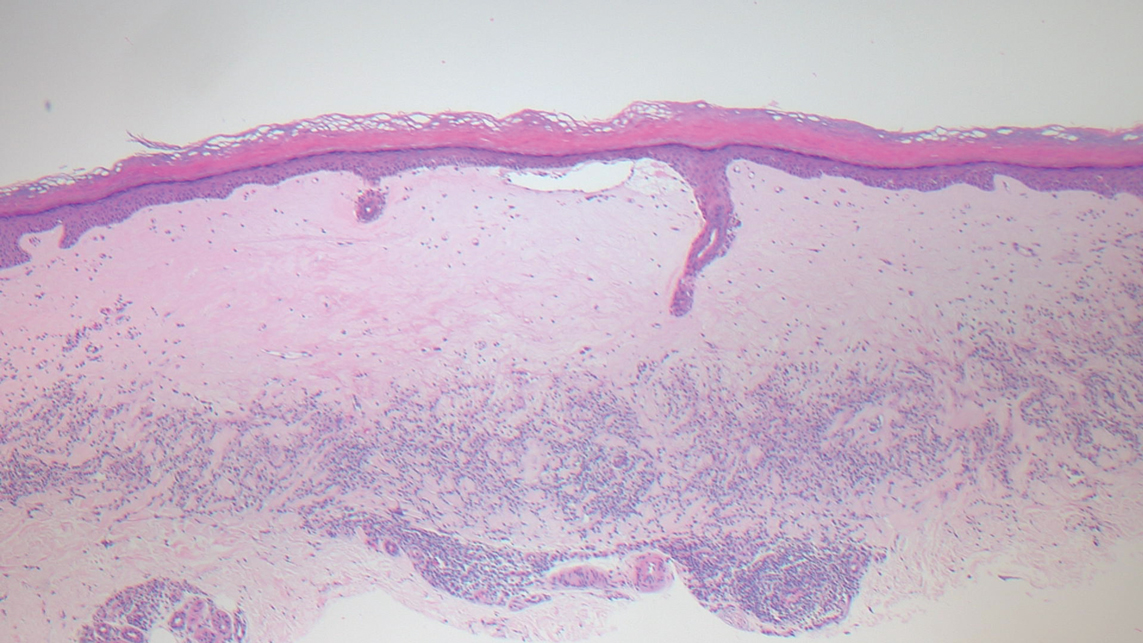

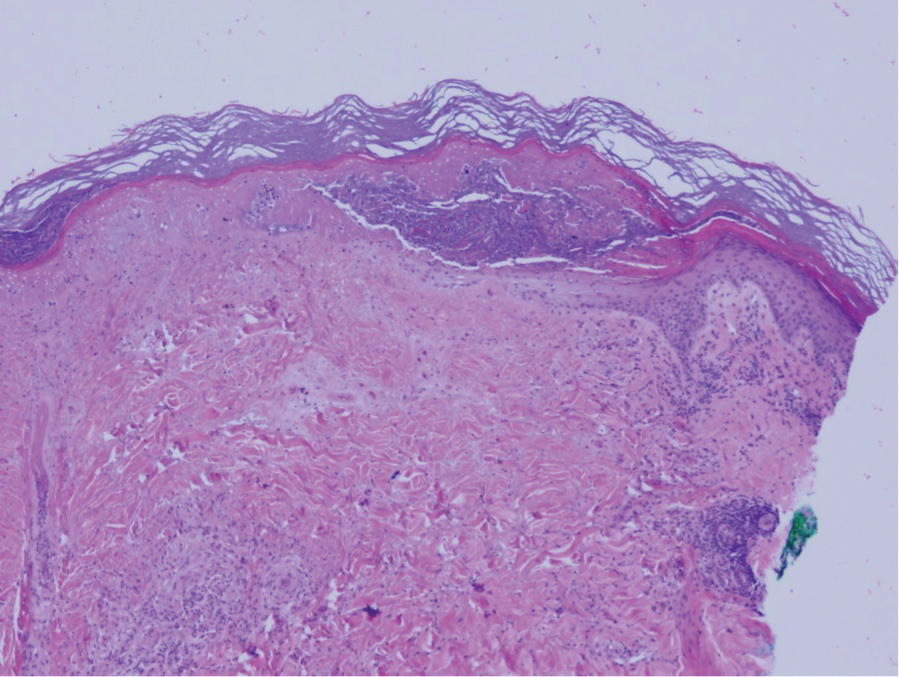

Guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus initially presents as polygonal, bluish white papules that coalesce into plaques.6 Over time, these lesions become more atrophic and may mimic Degos disease but appear differently on histopathology. Histopathology of lichen sclerosus classically demonstrates atrophy of the epidermis with loss of the rete ridges and vacuolar surface changes. Homogenization of the superficial/papillary dermis with an underlying bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate also is seen (Figure 2).6

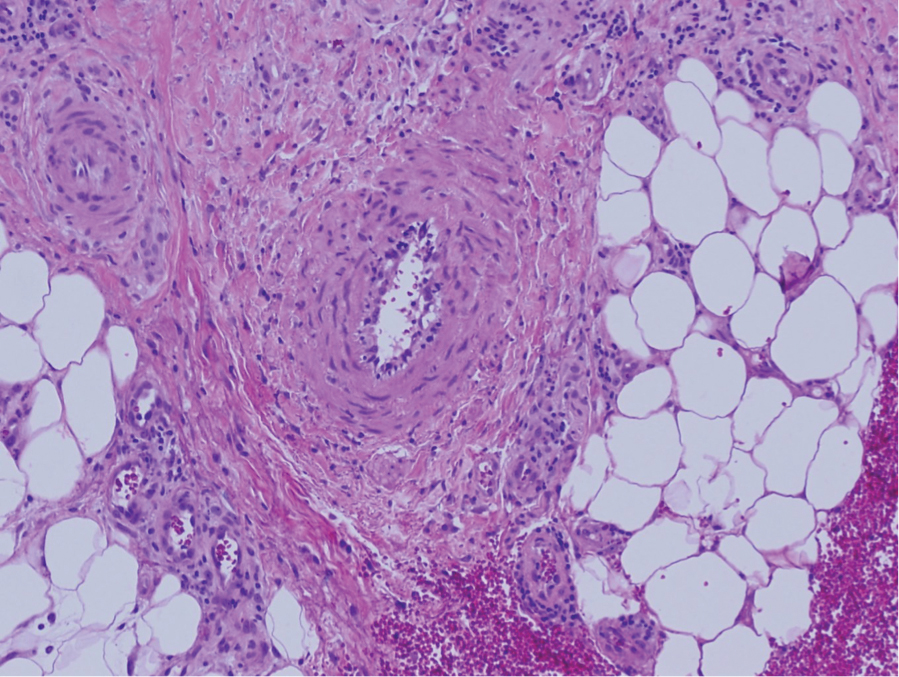

Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by chronic recurrent ulceration of the legs secondary to thrombosis and subsequent ischemia. In the initial phase of this disease, livedo reticularis is seen followed by the development of ulcerations. As these ulcerations heal, they leave behind porcelain white scars referred to as atrophie blanche.7 The areas of scarring in livedoid vasculopathy are broad and angulated, differentiating them from the small, round, porcelain white macules in end-stage Degos disease. Histopathology demonstrates thrombosis and fibrin occlusion of the upper and mid dermal vessels. Very minimal perivascular infiltrate typically is seen, but when it is present, the infiltrate mostly is lymphocytic. Hyalinization of the vessel walls also is seen, particularly in the atrophie blanche stage (Figure 3).7

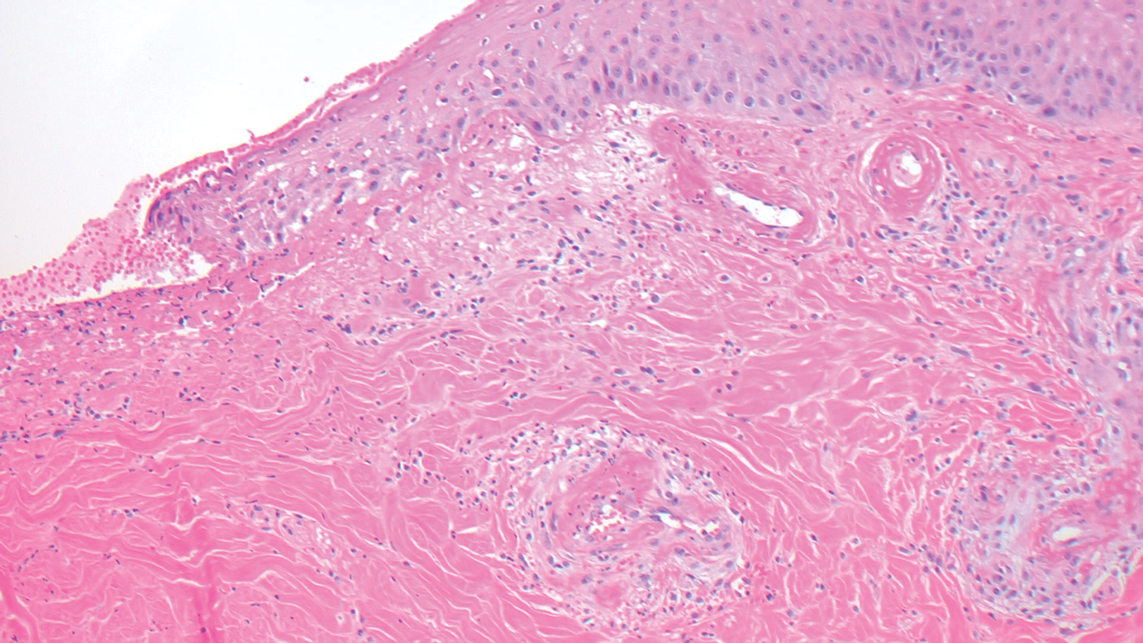

Lymphomatoid papulosis classically presents with pruritic red papules that often spontaneously involute. After resolution of the primary lesions, atrophic varioliform scars may be left behind that can resemble Degos disease.8 Classically, there are 5 histopathologic subtypes: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A is the most common type of lymphomatoid papulosis, and histopathology demonstrates a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that consists of cells arranged in small clusters. Numerous medium- to large-sized atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm are seen, and mitotic figures are common (Figure 4).8

Our case was particularly interesting because the patient was 2 to 3 weeks pregnant. Degos disease in pregnancy appears to be quite exceptional. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Degos disease and pregnancy revealed only 4 other cases reported in the literature.9-12 With the exception of a single case that was complicated by severe abdominal pain requiring labor induction, the other reported cases resulted in uncomplicated pregnancies.9-12 Conversely, our patient's pregnancy was complicated by gestational hypertension and fetal hydrops requiring a preterm cesarean delivery. Furthermore, the infant had multiple complications, which were attributed to both placental insufficiency and a coagulopathic state.

Our patient also was found to have a heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation on workup. A PubMed search using the terms factor V Leiden mutation and Degos disease revealed 2 other cases of factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos disease.13,14 The importance of factor V Leiden mutations in patients with Degos disease currently is unclear.

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)--a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277.

- Magro CM, Wang X, Garrett-Bakelman F, et al. The effects of eculizumab on the pathology of malignant atrophic papulosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:185.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Tronnier M, Mitteldorf C. Histologic features of granulomatous skin diseases. part 1: non-infectious granulomatous disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:211-216.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478‐488.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73.

- Moulin G, Barrut D, Franc MP, et al. Familial Degos' atrophic papulosis (mother-daughter). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:149-155.

- Bogenrieder T, Kuske M, Landthaler M, et al. Benign Degos' disease developing during pregnancy and followed for 10 years. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:284-287.

- Sharma S, Brennan B, Naden R, et al. A case of Degos disease in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9:167-168.

- Zhao Q, Zhang S, Dong A. An unusual case of abdominal pain. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:E1-E2.

- Darwich E, Guilabert A, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Dermoscopic description of a patient with thrombocythemia and factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos' disease. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:604-606.

- Hohwy T, Jensen MG, Tøttrup A, et al. A fatal case of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos' disease) in a man with factor V Leiden mutation and lupus anticoagulant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:245-247.

The Diagnosis: Degos Disease

The pathophysiology of Degos disease (malignant atrophic papulosis) is unknown.1 Histopathology demonstrates a wedge-shaped area of dermal necrosis with edema and mucin deposition extending from the papillary dermis to the deep reticular dermis. Occluded vessels, thrombosis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates also may be seen, particularly at the dermal subcutaneous junction and at the periphery of the wedge-shaped infarction. The vascular damage that occurs may be the result of vasculitis, coagulopathy, or endothelial cell dysfunction.1

Patients typically present with small, round, erythematous papules that eventually develop atrophic porcelain white centers and telangiectatic rims. These lesions most commonly occur on the trunk and arms. In the benign form of atrophic papulosis, only the skin is involved; however, systemic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system can occur, resulting in bowel perforation and stroke, respectively.1 Although there is no definitive treatment of Degos disease, successful therapy with aspirin or dipyridamole has been reported.1 Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds C5, and treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog, are emerging treatment options.2,3 The differential diagnosis of Degos disease may include granuloma annulare, guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus, livedoid vasculopathy, and lymphomatoid papulosis.

Granuloma annulare may clinically mimic the erythematous papules seen in early Degos disease, and histopathology can be used to distinguish between these two disease processes. Localized granuloma annulare is the most common variant and clinically presents as pink papules and plaques in an annular configuration.4 Histopathology demonstrates an unremarkable epidermis; however, the dermis contains degenerated collagen surrounded by palisading histiocytes as well as lymphocytes. Similar to Degos disease, increased mucin is seen within these areas of degeneration, but occluded vessels and thrombosis typically are not seen (Figure 1).4,5

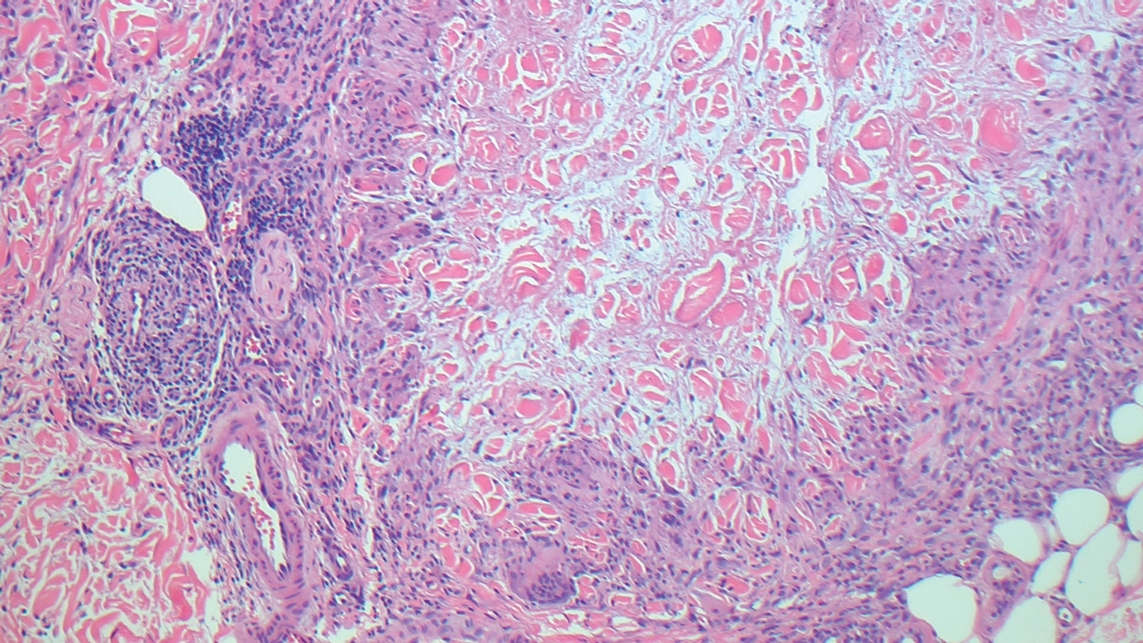

Guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus initially presents as polygonal, bluish white papules that coalesce into plaques.6 Over time, these lesions become more atrophic and may mimic Degos disease but appear differently on histopathology. Histopathology of lichen sclerosus classically demonstrates atrophy of the epidermis with loss of the rete ridges and vacuolar surface changes. Homogenization of the superficial/papillary dermis with an underlying bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate also is seen (Figure 2).6

Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by chronic recurrent ulceration of the legs secondary to thrombosis and subsequent ischemia. In the initial phase of this disease, livedo reticularis is seen followed by the development of ulcerations. As these ulcerations heal, they leave behind porcelain white scars referred to as atrophie blanche.7 The areas of scarring in livedoid vasculopathy are broad and angulated, differentiating them from the small, round, porcelain white macules in end-stage Degos disease. Histopathology demonstrates thrombosis and fibrin occlusion of the upper and mid dermal vessels. Very minimal perivascular infiltrate typically is seen, but when it is present, the infiltrate mostly is lymphocytic. Hyalinization of the vessel walls also is seen, particularly in the atrophie blanche stage (Figure 3).7

Lymphomatoid papulosis classically presents with pruritic red papules that often spontaneously involute. After resolution of the primary lesions, atrophic varioliform scars may be left behind that can resemble Degos disease.8 Classically, there are 5 histopathologic subtypes: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A is the most common type of lymphomatoid papulosis, and histopathology demonstrates a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that consists of cells arranged in small clusters. Numerous medium- to large-sized atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm are seen, and mitotic figures are common (Figure 4).8

Our case was particularly interesting because the patient was 2 to 3 weeks pregnant. Degos disease in pregnancy appears to be quite exceptional. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Degos disease and pregnancy revealed only 4 other cases reported in the literature.9-12 With the exception of a single case that was complicated by severe abdominal pain requiring labor induction, the other reported cases resulted in uncomplicated pregnancies.9-12 Conversely, our patient's pregnancy was complicated by gestational hypertension and fetal hydrops requiring a preterm cesarean delivery. Furthermore, the infant had multiple complications, which were attributed to both placental insufficiency and a coagulopathic state.

Our patient also was found to have a heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation on workup. A PubMed search using the terms factor V Leiden mutation and Degos disease revealed 2 other cases of factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos disease.13,14 The importance of factor V Leiden mutations in patients with Degos disease currently is unclear.

The Diagnosis: Degos Disease

The pathophysiology of Degos disease (malignant atrophic papulosis) is unknown.1 Histopathology demonstrates a wedge-shaped area of dermal necrosis with edema and mucin deposition extending from the papillary dermis to the deep reticular dermis. Occluded vessels, thrombosis, and perivascular lymphocytic infiltrates also may be seen, particularly at the dermal subcutaneous junction and at the periphery of the wedge-shaped infarction. The vascular damage that occurs may be the result of vasculitis, coagulopathy, or endothelial cell dysfunction.1

Patients typically present with small, round, erythematous papules that eventually develop atrophic porcelain white centers and telangiectatic rims. These lesions most commonly occur on the trunk and arms. In the benign form of atrophic papulosis, only the skin is involved; however, systemic involvement of the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system can occur, resulting in bowel perforation and stroke, respectively.1 Although there is no definitive treatment of Degos disease, successful therapy with aspirin or dipyridamole has been reported.1 Eculizumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds C5, and treprostinil, a prostacyclin analog, are emerging treatment options.2,3 The differential diagnosis of Degos disease may include granuloma annulare, guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus, livedoid vasculopathy, and lymphomatoid papulosis.

Granuloma annulare may clinically mimic the erythematous papules seen in early Degos disease, and histopathology can be used to distinguish between these two disease processes. Localized granuloma annulare is the most common variant and clinically presents as pink papules and plaques in an annular configuration.4 Histopathology demonstrates an unremarkable epidermis; however, the dermis contains degenerated collagen surrounded by palisading histiocytes as well as lymphocytes. Similar to Degos disease, increased mucin is seen within these areas of degeneration, but occluded vessels and thrombosis typically are not seen (Figure 1).4,5

Guttate extragenital lichen sclerosus initially presents as polygonal, bluish white papules that coalesce into plaques.6 Over time, these lesions become more atrophic and may mimic Degos disease but appear differently on histopathology. Histopathology of lichen sclerosus classically demonstrates atrophy of the epidermis with loss of the rete ridges and vacuolar surface changes. Homogenization of the superficial/papillary dermis with an underlying bandlike lymphocytic infiltrate also is seen (Figure 2).6

Livedoid vasculopathy is characterized by chronic recurrent ulceration of the legs secondary to thrombosis and subsequent ischemia. In the initial phase of this disease, livedo reticularis is seen followed by the development of ulcerations. As these ulcerations heal, they leave behind porcelain white scars referred to as atrophie blanche.7 The areas of scarring in livedoid vasculopathy are broad and angulated, differentiating them from the small, round, porcelain white macules in end-stage Degos disease. Histopathology demonstrates thrombosis and fibrin occlusion of the upper and mid dermal vessels. Very minimal perivascular infiltrate typically is seen, but when it is present, the infiltrate mostly is lymphocytic. Hyalinization of the vessel walls also is seen, particularly in the atrophie blanche stage (Figure 3).7

Lymphomatoid papulosis classically presents with pruritic red papules that often spontaneously involute. After resolution of the primary lesions, atrophic varioliform scars may be left behind that can resemble Degos disease.8 Classically, there are 5 histopathologic subtypes: A, B, C, D, and E. Type A is the most common type of lymphomatoid papulosis, and histopathology demonstrates a dermal lymphocytic infiltrate that consists of cells arranged in small clusters. Numerous medium- to large-sized atypical lymphocytes with prominent nucleoli and abundant cytoplasm are seen, and mitotic figures are common (Figure 4).8

Our case was particularly interesting because the patient was 2 to 3 weeks pregnant. Degos disease in pregnancy appears to be quite exceptional. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms Degos disease and pregnancy revealed only 4 other cases reported in the literature.9-12 With the exception of a single case that was complicated by severe abdominal pain requiring labor induction, the other reported cases resulted in uncomplicated pregnancies.9-12 Conversely, our patient's pregnancy was complicated by gestational hypertension and fetal hydrops requiring a preterm cesarean delivery. Furthermore, the infant had multiple complications, which were attributed to both placental insufficiency and a coagulopathic state.

Our patient also was found to have a heterozygous factor V Leiden mutation on workup. A PubMed search using the terms factor V Leiden mutation and Degos disease revealed 2 other cases of factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos disease.13,14 The importance of factor V Leiden mutations in patients with Degos disease currently is unclear.

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)--a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277.

- Magro CM, Wang X, Garrett-Bakelman F, et al. The effects of eculizumab on the pathology of malignant atrophic papulosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:185.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Tronnier M, Mitteldorf C. Histologic features of granulomatous skin diseases. part 1: non-infectious granulomatous disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:211-216.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478‐488.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73.

- Moulin G, Barrut D, Franc MP, et al. Familial Degos' atrophic papulosis (mother-daughter). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:149-155.

- Bogenrieder T, Kuske M, Landthaler M, et al. Benign Degos' disease developing during pregnancy and followed for 10 years. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:284-287.

- Sharma S, Brennan B, Naden R, et al. A case of Degos disease in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9:167-168.

- Zhao Q, Zhang S, Dong A. An unusual case of abdominal pain. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:E1-E2.

- Darwich E, Guilabert A, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Dermoscopic description of a patient with thrombocythemia and factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos' disease. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:604-606.

- Hohwy T, Jensen MG, Tøttrup A, et al. A fatal case of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos' disease) in a man with factor V Leiden mutation and lupus anticoagulant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:245-247.

- Theodoridis A, Makrantonaki E, Zouboulis CC. Malignant atrophic papulosis (Köhlmeier-Degos disease)--a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:10.

- Oliver B, Boehm M, Rosing DR, et al. Diffuse atrophic papules and plaques, intermittent abdominal pain, paresthesias, and cardiac abnormalities in a 55-year-old woman. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:1274-1277.

- Magro CM, Wang X, Garrett-Bakelman F, et al. The effects of eculizumab on the pathology of malignant atrophic papulosis. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2013;8:185.

- Piette EW, Rosenbach M. Granuloma annulare: clinical and histologic variants, epidemiology, and genetics. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:457-465.

- Tronnier M, Mitteldorf C. Histologic features of granulomatous skin diseases. part 1: non-infectious granulomatous disorders. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2015;13:211-216.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus: an update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Vasudevan B, Neema S, Verma R. Livedoid vasculopathy: a review of pathogenesis and principles of management. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2016;82:478‐488.

- Martinez-Cabriales SA, Walsh S, Sade S, et al. Lymphomatoid papulosis: an update and review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2020;34:59-73.

- Moulin G, Barrut D, Franc MP, et al. Familial Degos' atrophic papulosis (mother-daughter). Ann Dermatol Venereol. 1984;111:149-155.

- Bogenrieder T, Kuske M, Landthaler M, et al. Benign Degos' disease developing during pregnancy and followed for 10 years. Acta Derm Venereol. 2002;82:284-287.

- Sharma S, Brennan B, Naden R, et al. A case of Degos disease in pregnancy. Obstet Med. 2016;9:167-168.

- Zhao Q, Zhang S, Dong A. An unusual case of abdominal pain. Gastroenterology. 2018;154:E1-E2.

- Darwich E, Guilabert A, Mascaró JM Jr, et al. Dermoscopic description of a patient with thrombocythemia and factor V Leiden mutation-associated Degos' disease. Int J Dermatol. 2011;50:604-606.

- Hohwy T, Jensen MG, Tøttrup A, et al. A fatal case of malignant atrophic papulosis (Degos' disease) in a man with factor V Leiden mutation and lupus anticoagulant. Acta Derm Venereol. 2006;86:245-247.

A 36-year-old pregnant woman presented with painful erythematous papules on the palms and fingers of 2 months’ duration. Similar lesions developed on the thighs and feet several weeks later. Two tender macules with central areas of porcelain white scarring rimmed by telangiectases on the right foot also were present. A punch biopsy of these lesions demonstrated a wedge-shaped area of ischemic necrosis associated with dermal mucin without associated necrobiosis. Fibrin thrombi were seen within several small dermal vessels and were associated with a perivascular lymphocytic infiltrate. Endotheliitis was observed within a deep dermal vessel. Laboratory workup including syphilis IgG, antinuclear antibodies, extractable nuclear antigen antibodies, anti–double-stranded DNA, antistreptolysin O antibodies, Russell viper venom time, cryoglobulin, hepatitis screening, perinuclear antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies (ANCA), and cytoplasmic ANCA was unremarkable. Hypercoagulable studies including prothrombin gene mutation, factor V Leiden, plasminogen, proteins C and S, antithrombin III, homocysteine, and antiphospholipid IgM and IgG antibodies were notable only for heterozygosity for factor V Leiden.

Reporting Biopsy Margin Status for Cutaneous Basal Cell Carcinoma: To Do or Not to Do

To the Editor:

In an interesting analysis, Brady and Hossler1 (Cutis. 2020;106:315-317) highlighted the limitations of histopathologic biopsy margin evaluation for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Taking into consideration the high prevalence of BCC and its medical and economic impact on the health care system, the issue raised by the authors is an important one. They proposed that pathologists may omit reporting margins or clarify the limitations in their reports. It is a valid suggestion; however, in practice, margin evaluation is not always a simple process and is influenced by a number of factors.

The subject of optimum margins for BCC has been debated over decades now; however, ambiguity and lack of definitive guidelines on certain aspects still remain, leading to a lack of standardization and variability in reporting, which opens potential for error. In anatomical pathology, the biopsies for malignancies are interpreted to confirm diagnosis and perform risk assessment, with evaluation of margins generally reserved for subsequent definitive resections. Typically, margins are not required by clinicians or reported by pathologists in common endoscopic (eg, stomach, colon) or needle core (eg, prostate, breast) biopsies. Skin holds a rather unique position in which margin evaluation is not just limited to excisions. With the exception of samples generated from electrodesiccation and curettage, it is common practice by some laboratories to report margins on most specimens of cutaneous malignancies.

In simple terms, when margins are labeled negative there should be no residual disease, and when they are deemed positive there should be disease still persisting in the patient. Margin evaluation for BCC on biopsies falls short on both fronts. In one analysis, 24% (34/143) of shave biopsies reported with negative margins displayed residual BCC in ensuing re-excisions (negative predictive value: 76%).2 Standard bread-loafing, en-face margins and inking for orientation utilized to provide a thorough margin evaluation of excisions cannot be optimally achieved on small skin biopsies. Microscopic sections for analysis are 2-dimensional representations of 3-dimensional structures. Slides prepared can miss deeply embedded outermost margins, positioned parallel to the plane of sectioning, thereby creating blind spots where margins cannot be precisely assessed and generating an inherent limitation in evaluation. Exhaustive deeper levels done routinely can address this issue to a certain degree; however, it can be an impractical solution with cost implications and delay in turnaround time.

Conversely, it also is common to encounter absence of residual BCC in re-excisions in which the original biopsy margins were labeled positive. In one analysis, 49% of BCC patients (n=100) with positive biopsy margins did not display residual neoplasm on following re-excisions.3 Localized biopsy site immune response as a cause of postbiopsy regression of residual tumor has been hypothesized to produce this phenomenon. Moreover, initial biopsies may eliminate the majority of the tumor with only minimal disease persisting. Re-excisions submitted in toto allow for a systematic examination; however, areas in between sections still remain where minute residual tumor may hide. Searching for such occult foci generally is not aggressively pursued via deeper levels unless the margins of re-excision are in question.

Superficial-type BCC (or superficial multifocal BCC) is a major factor in precluding precise biopsy margin evaluation. In a study where initial biopsies reported with negative margins displayed residual BCC in subsequent re-excisions, 91% (31/34) of residual BCCs were of superficial variety.2 Clinically, superficial BCC frequently has indistinct borders with subtle subclinical peripheral progression. It has a tendency to expand radially, with the clinical appearance deceptively smaller than its true extent. In a plane of histopathologic section, superficial BCC may exhibit skip zones within the epidermis. Even though the margin may seem uninvolved on the slide, a noncontiguous focus may still emerge beyond the “negative” margin. Because superficial pattern is not unusual as one of the components of mixed histology (composite) BCC, this issue is not just limited to tumors specifically designated as superficial type.4

The intent of a procedure is important to recognize. If a biopsy is done with the intention of diagnosis only, the pathologic assessment can be limited to tumor identification and core data elements, with margin evaluation reserved for excisions done with therapeutic intent. However, the intent is not always clear, which adds to ambiguity on when to report margins. It is not uncommon to find saucerization shaves or large punch biopsies for BCC carried out with a therapeutic intent. The status of margin is desired in such samples; however, the intent is not always clearly communicated on requisitions. To avoid any gaps in communication, some pathologists may err on the side of caution and start routinely reporting margins on biopsies.

Taking into account the inaccuracy of margin assessment in biopsies, an argument for omitting margin reporting is plausible. Although dermatologists are the major contributors of skin samples, pathology laboratories cater to a broader clientele. Other physicians from different surgical and medical specialities also perform skin biopsies, and catering to a variety of specialities adds another layer of complexity. A dermatologist may appreciate the debate regarding reliability of margins; however, a physician from another speciality who is not as familiar with the diseases of the integument may lack proper understanding. Omitting margin reporting may lead to misinterpretations or false assumptions, such as, “The margins must be uninvolved, otherwise the pathologist would have said something.” This also can generate additional phone or email inquiries and second review requests. Rather than completely omitting them, another strategy can be to report margins in more quantitative terms. One reporting approach is to have 3 categories of involved, uninvolved, and uninvolved but close for margins less than 1 mm. The cases in the third category may require greater scrutiny by deeper levels or an added caveat in the comment addressing the limitation. If the status of margins is not reported due to a certain reason, a short comment can be added to explain the reason.

In sum, clinicians should recognize that “margin negative” on skin biopsy does not always equate to “completely excised.” Margin status on biopsies is a data item that essentially provides a probability of margin clearance. Completely omitting the margin status on all biopsies may not be the most prudent approach; however, improved guidelines and modifications to enhance the reporting are definitely required.

References

- Brady MC, Hossler EW. Reliability of biopsy margin status for basal cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Cutis. 2020;106:315-317.

- Willardson HB, Lombardo J, Raines M, et al. Predictive value of basal cell carcinoma biopsies with negative margins: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:42-46.

- Yuan Y, Duff ML, Sammons DL, et al. Retrospective chart review of skin cancer presence in the wide excisions. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:52-56.

- Cohen PR, Schulze KE, Nelson BR. Basal cell carcinoma with mixed histology: a possible pathogenesis for recurrent skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:542-551.

Continue to: Author's Response...

Authors’ Response

We appreciate the thorough and thoughtful comments in the Letter to the Editor. We agree with the author’s assertion that negative margins on skin specimens does not equate to “completely excised” and that the intent of the clinician is not always clear, even when the pathologist has ready access to the clinician’s notes, as was the case for the majority of specimens included in our study.

There is already variability in how pathologists report margins, including the specific verbiage used, at least for melanocytic lesions.1 The choice of whether or not to report margins and the meaning of those margins is complex due to the uncertainty inherent in margin assessment. Quantifying this uncertainty was the main reason for our study. Ultimately, the pathologist’s decision on whether and how to report margins should be focused on improving patient outcomes. There are benefits and drawbacks to all approaches, and our goal is to provide more information for clinicians and pathologists so that they may better care for their patients. Understanding the limitations of margins on submitted skin specimens—whether margins are reported or not—can only serve to guide improve clinical decision-making.

We also agree that the breadth of specialties of submitting clinicians make reporting of margins difficult, and there is likely similar breadth in their understanding of the nuances of margin assessment and reports. The solution to this problem is adequate education regarding the limitations of a pathology report, and specifically what is meant when margins are (or are not) reported on skin specimens. How to best educate the myriad clinicians who submit biopsies is, of course, the ultimate challenge.

We hope that our study adds information to this ongoing debate regarding margin status reporting, and we appreciate the discussion points raised by the author.

Eric Hossler, MD; Mary Brady, MD

From the Department of Dermatology, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Reference

- Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF, Stewart E, et al. Evaluation of surgical margins in melanocytic lesions: a survey among 152 dermatopathologists.J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:293-299.

To the Editor:

In an interesting analysis, Brady and Hossler1 (Cutis. 2020;106:315-317) highlighted the limitations of histopathologic biopsy margin evaluation for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Taking into consideration the high prevalence of BCC and its medical and economic impact on the health care system, the issue raised by the authors is an important one. They proposed that pathologists may omit reporting margins or clarify the limitations in their reports. It is a valid suggestion; however, in practice, margin evaluation is not always a simple process and is influenced by a number of factors.

The subject of optimum margins for BCC has been debated over decades now; however, ambiguity and lack of definitive guidelines on certain aspects still remain, leading to a lack of standardization and variability in reporting, which opens potential for error. In anatomical pathology, the biopsies for malignancies are interpreted to confirm diagnosis and perform risk assessment, with evaluation of margins generally reserved for subsequent definitive resections. Typically, margins are not required by clinicians or reported by pathologists in common endoscopic (eg, stomach, colon) or needle core (eg, prostate, breast) biopsies. Skin holds a rather unique position in which margin evaluation is not just limited to excisions. With the exception of samples generated from electrodesiccation and curettage, it is common practice by some laboratories to report margins on most specimens of cutaneous malignancies.

In simple terms, when margins are labeled negative there should be no residual disease, and when they are deemed positive there should be disease still persisting in the patient. Margin evaluation for BCC on biopsies falls short on both fronts. In one analysis, 24% (34/143) of shave biopsies reported with negative margins displayed residual BCC in ensuing re-excisions (negative predictive value: 76%).2 Standard bread-loafing, en-face margins and inking for orientation utilized to provide a thorough margin evaluation of excisions cannot be optimally achieved on small skin biopsies. Microscopic sections for analysis are 2-dimensional representations of 3-dimensional structures. Slides prepared can miss deeply embedded outermost margins, positioned parallel to the plane of sectioning, thereby creating blind spots where margins cannot be precisely assessed and generating an inherent limitation in evaluation. Exhaustive deeper levels done routinely can address this issue to a certain degree; however, it can be an impractical solution with cost implications and delay in turnaround time.

Conversely, it also is common to encounter absence of residual BCC in re-excisions in which the original biopsy margins were labeled positive. In one analysis, 49% of BCC patients (n=100) with positive biopsy margins did not display residual neoplasm on following re-excisions.3 Localized biopsy site immune response as a cause of postbiopsy regression of residual tumor has been hypothesized to produce this phenomenon. Moreover, initial biopsies may eliminate the majority of the tumor with only minimal disease persisting. Re-excisions submitted in toto allow for a systematic examination; however, areas in between sections still remain where minute residual tumor may hide. Searching for such occult foci generally is not aggressively pursued via deeper levels unless the margins of re-excision are in question.

Superficial-type BCC (or superficial multifocal BCC) is a major factor in precluding precise biopsy margin evaluation. In a study where initial biopsies reported with negative margins displayed residual BCC in subsequent re-excisions, 91% (31/34) of residual BCCs were of superficial variety.2 Clinically, superficial BCC frequently has indistinct borders with subtle subclinical peripheral progression. It has a tendency to expand radially, with the clinical appearance deceptively smaller than its true extent. In a plane of histopathologic section, superficial BCC may exhibit skip zones within the epidermis. Even though the margin may seem uninvolved on the slide, a noncontiguous focus may still emerge beyond the “negative” margin. Because superficial pattern is not unusual as one of the components of mixed histology (composite) BCC, this issue is not just limited to tumors specifically designated as superficial type.4

The intent of a procedure is important to recognize. If a biopsy is done with the intention of diagnosis only, the pathologic assessment can be limited to tumor identification and core data elements, with margin evaluation reserved for excisions done with therapeutic intent. However, the intent is not always clear, which adds to ambiguity on when to report margins. It is not uncommon to find saucerization shaves or large punch biopsies for BCC carried out with a therapeutic intent. The status of margin is desired in such samples; however, the intent is not always clearly communicated on requisitions. To avoid any gaps in communication, some pathologists may err on the side of caution and start routinely reporting margins on biopsies.

Taking into account the inaccuracy of margin assessment in biopsies, an argument for omitting margin reporting is plausible. Although dermatologists are the major contributors of skin samples, pathology laboratories cater to a broader clientele. Other physicians from different surgical and medical specialities also perform skin biopsies, and catering to a variety of specialities adds another layer of complexity. A dermatologist may appreciate the debate regarding reliability of margins; however, a physician from another speciality who is not as familiar with the diseases of the integument may lack proper understanding. Omitting margin reporting may lead to misinterpretations or false assumptions, such as, “The margins must be uninvolved, otherwise the pathologist would have said something.” This also can generate additional phone or email inquiries and second review requests. Rather than completely omitting them, another strategy can be to report margins in more quantitative terms. One reporting approach is to have 3 categories of involved, uninvolved, and uninvolved but close for margins less than 1 mm. The cases in the third category may require greater scrutiny by deeper levels or an added caveat in the comment addressing the limitation. If the status of margins is not reported due to a certain reason, a short comment can be added to explain the reason.

In sum, clinicians should recognize that “margin negative” on skin biopsy does not always equate to “completely excised.” Margin status on biopsies is a data item that essentially provides a probability of margin clearance. Completely omitting the margin status on all biopsies may not be the most prudent approach; however, improved guidelines and modifications to enhance the reporting are definitely required.

References

- Brady MC, Hossler EW. Reliability of biopsy margin status for basal cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Cutis. 2020;106:315-317.

- Willardson HB, Lombardo J, Raines M, et al. Predictive value of basal cell carcinoma biopsies with negative margins: a retrospective cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79:42-46.

- Yuan Y, Duff ML, Sammons DL, et al. Retrospective chart review of skin cancer presence in the wide excisions. World J Clin Cases. 2014;2:52-56.

- Cohen PR, Schulze KE, Nelson BR. Basal cell carcinoma with mixed histology: a possible pathogenesis for recurrent skin cancer. Dermatol Surg. 2006;32:542-551.

Continue to: Author's Response...

Authors’ Response

We appreciate the thorough and thoughtful comments in the Letter to the Editor. We agree with the author’s assertion that negative margins on skin specimens does not equate to “completely excised” and that the intent of the clinician is not always clear, even when the pathologist has ready access to the clinician’s notes, as was the case for the majority of specimens included in our study.

There is already variability in how pathologists report margins, including the specific verbiage used, at least for melanocytic lesions.1 The choice of whether or not to report margins and the meaning of those margins is complex due to the uncertainty inherent in margin assessment. Quantifying this uncertainty was the main reason for our study. Ultimately, the pathologist’s decision on whether and how to report margins should be focused on improving patient outcomes. There are benefits and drawbacks to all approaches, and our goal is to provide more information for clinicians and pathologists so that they may better care for their patients. Understanding the limitations of margins on submitted skin specimens—whether margins are reported or not—can only serve to guide improve clinical decision-making.

We also agree that the breadth of specialties of submitting clinicians make reporting of margins difficult, and there is likely similar breadth in their understanding of the nuances of margin assessment and reports. The solution to this problem is adequate education regarding the limitations of a pathology report, and specifically what is meant when margins are (or are not) reported on skin specimens. How to best educate the myriad clinicians who submit biopsies is, of course, the ultimate challenge.

We hope that our study adds information to this ongoing debate regarding margin status reporting, and we appreciate the discussion points raised by the author.

Eric Hossler, MD; Mary Brady, MD

From the Department of Dermatology, Geisinger Health System, Danville, Pennsylvania.

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Reference

- Sellheyer K, Bergfeld WF, Stewart E, et al. Evaluation of surgical margins in melanocytic lesions: a survey among 152 dermatopathologists.J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:293-299.

To the Editor:

In an interesting analysis, Brady and Hossler1 (Cutis. 2020;106:315-317) highlighted the limitations of histopathologic biopsy margin evaluation for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (BCC). Taking into consideration the high prevalence of BCC and its medical and economic impact on the health care system, the issue raised by the authors is an important one. They proposed that pathologists may omit reporting margins or clarify the limitations in their reports. It is a valid suggestion; however, in practice, margin evaluation is not always a simple process and is influenced by a number of factors.

The subject of optimum margins for BCC has been debated over decades now; however, ambiguity and lack of definitive guidelines on certain aspects still remain, leading to a lack of standardization and variability in reporting, which opens potential for error. In anatomical pathology, the biopsies for malignancies are interpreted to confirm diagnosis and perform risk assessment, with evaluation of margins generally reserved for subsequent definitive resections. Typically, margins are not required by clinicians or reported by pathologists in common endoscopic (eg, stomach, colon) or needle core (eg, prostate, breast) biopsies. Skin holds a rather unique position in which margin evaluation is not just limited to excisions. With the exception of samples generated from electrodesiccation and curettage, it is common practice by some laboratories to report margins on most specimens of cutaneous malignancies.

In simple terms, when margins are labeled negative there should be no residual disease, and when they are deemed positive there should be disease still persisting in the patient. Margin evaluation for BCC on biopsies falls short on both fronts. In one analysis, 24% (34/143) of shave biopsies reported with negative margins displayed residual BCC in ensuing re-excisions (negative predictive value: 76%).2 Standard bread-loafing, en-face margins and inking for orientation utilized to provide a thorough margin evaluation of excisions cannot be optimally achieved on small skin biopsies. Microscopic sections for analysis are 2-dimensional representations of 3-dimensional structures. Slides prepared can miss deeply embedded outermost margins, positioned parallel to the plane of sectioning, thereby creating blind spots where margins cannot be precisely assessed and generating an inherent limitation in evaluation. Exhaustive deeper levels done routinely can address this issue to a certain degree; however, it can be an impractical solution with cost implications and delay in turnaround time.

Conversely, it also is common to encounter absence of residual BCC in re-excisions in which the original biopsy margins were labeled positive. In one analysis, 49% of BCC patients (n=100) with positive biopsy margins did not display residual neoplasm on following re-excisions.3 Localized biopsy site immune response as a cause of postbiopsy regression of residual tumor has been hypothesized to produce this phenomenon. Moreover, initial biopsies may eliminate the majority of the tumor with only minimal disease persisting. Re-excisions submitted in toto allow for a systematic examination; however, areas in between sections still remain where minute residual tumor may hide. Searching for such occult foci generally is not aggressively pursued via deeper levels unless the margins of re-excision are in question.

Superficial-type BCC (or superficial multifocal BCC) is a major factor in precluding precise biopsy margin evaluation. In a study where initial biopsies reported with negative margins displayed residual BCC in subsequent re-excisions, 91% (31/34) of residual BCCs were of superficial variety.2 Clinically, superficial BCC frequently has indistinct borders with subtle subclinical peripheral progression. It has a tendency to expand radially, with the clinical appearance deceptively smaller than its true extent. In a plane of histopathologic section, superficial BCC may exhibit skip zones within the epidermis. Even though the margin may seem uninvolved on the slide, a noncontiguous focus may still emerge beyond the “negative” margin. Because superficial pattern is not unusual as one of the components of mixed histology (composite) BCC, this issue is not just limited to tumors specifically designated as superficial type.4

The intent of a procedure is important to recognize. If a biopsy is done with the intention of diagnosis only, the pathologic assessment can be limited to tumor identification and core data elements, with margin evaluation reserved for excisions done with therapeutic intent. However, the intent is not always clear, which adds to ambiguity on when to report margins. It is not uncommon to find saucerization shaves or large punch biopsies for BCC carried out with a therapeutic intent. The status of margin is desired in such samples; however, the intent is not always clearly communicated on requisitions. To avoid any gaps in communication, some pathologists may err on the side of caution and start routinely reporting margins on biopsies.

Taking into account the inaccuracy of margin assessment in biopsies, an argument for omitting margin reporting is plausible. Although dermatologists are the major contributors of skin samples, pathology laboratories cater to a broader clientele. Other physicians from different surgical and medical specialities also perform skin biopsies, and catering to a variety of specialities adds another layer of complexity. A dermatologist may appreciate the debate regarding reliability of margins; however, a physician from another speciality who is not as familiar with the diseases of the integument may lack proper understanding. Omitting margin reporting may lead to misinterpretations or false assumptions, such as, “The margins must be uninvolved, otherwise the pathologist would have said something.” This also can generate additional phone or email inquiries and second review requests. Rather than completely omitting them, another strategy can be to report margins in more quantitative terms. One reporting approach is to have 3 categories of involved, uninvolved, and uninvolved but close for margins less than 1 mm. The cases in the third category may require greater scrutiny by deeper levels or an added caveat in the comment addressing the limitation. If the status of margins is not reported due to a certain reason, a short comment can be added to explain the reason.