User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Racial morphing: A conundrum in cosmetic dermatology

HONOLULU – In the opinion of Nazanin A. Saedi, MD, social media-induced dissatisfaction with appearance is getting out of hand in the field of cosmetic dermatology, with the emergence of apps to filter and edit images to the patient’s liking.

This, coupled with

“Overexposure of celebrity images and altered faces on social media have led to a trend of overarching brows, sculpted noses, enlarged cheeks, and sharply defined jawlines,” Dr. Saedi, cochair of the laser and aesthetics surgery center at Dermatology Associates of Plymouth Meeting, Pa., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE! “These trends have made people of different ethnicities morph into a similar appearance.”

At the meeting, she showed early career images of celebrities from different ethnic backgrounds, “and they all have unique features that make them look great,” said Dr. Saedi, clinical associate professor of dermatology at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. She then showed images of the same celebrities after they had undergone cosmetic procedures, “and they look so much more similar,” with overarched brows, sculpted noses, enlarged cheeks, and sharply defined jawlines. “Whereas they were all beautiful before individually, now they look very similar,” she said. “This is what we see on social media.”

Referring to the Kardashians as an example of celebrities who have had a lot of aesthetic treatments, look different than they did years ago, and are seen “more and more,” she added, “it’s this repeated overexposure to people on social media, to celebrities, that’s created this different trend of attractiveness.”

This trend also affects patients seeking cosmetic treatments, she noted. Individuals can use an app to alter their appearance, “changing the way they look to create the best version of themselves, they might say, or a filtered version of themselves,” said Dr. Saedi, one of the authors of a commentary on patient perception of beauty on social media published several years ago.

“I tell people, ‘Don’t use filters in your photos. Embrace your beauty.’ I have patients coming in who want to look like the social media photos they’ve curated, maybe larger lips or more definition in their jawline. What they don’t understand is that it takes a long time for that to happen. It’s a process.” In other cases, their desired outcome is not possible due to limits of their individual facial anatomy.

In a study published almost 20 years ago in the journal Perception, Irish researchers manipulated the familiarity of typical and distinctive faces to measure the effect on attractiveness. They found that episodic familiarity affects attractiveness ratings independently of general or structural familiarity.

“So, the more you saw a face, the more familiar that face was to you,” said Dr. Saedi, who was not involved with the study. “Over time, you felt that to be more attractive. I think that’s a lot of what’s going on in the trends that we’re seeing – both in real life and on social media. I do think we need to be more mindful of maintaining features that make an individual unique, while also maintaining their ethnic beauty.”

In an interview at the meeting, Jacqueline D. Watchmaker, MD, a board-certified cosmetic and medical dermatologist who practices in Scottsdale, Ariz., said that she identifies with the notion of racial morphing in her own clinical experience. “Patients come in and specifically ask for chiseled jawlines, high cheekbones, and bigger lips,” Dr. Watchmaker said. “It’s a tricky situation when they ask for [a treatment] you don’t think they need. I prefer a more staged approach to maintain their individuality while giving them a little bit of the aesthetic benefit that they’re looking for.”

Dr. Saedi disclosed ties with AbbVie, Aerolase, Allergan, Alma, Cartessa, Cynosure, Galderma Laboratories, LP, Grand Cosmetics, Revelle Aesthetics, and Revision Skincare. Dr. Watchmaker reported having no financial disclosures.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

HONOLULU – In the opinion of Nazanin A. Saedi, MD, social media-induced dissatisfaction with appearance is getting out of hand in the field of cosmetic dermatology, with the emergence of apps to filter and edit images to the patient’s liking.

This, coupled with

“Overexposure of celebrity images and altered faces on social media have led to a trend of overarching brows, sculpted noses, enlarged cheeks, and sharply defined jawlines,” Dr. Saedi, cochair of the laser and aesthetics surgery center at Dermatology Associates of Plymouth Meeting, Pa., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE! “These trends have made people of different ethnicities morph into a similar appearance.”

At the meeting, she showed early career images of celebrities from different ethnic backgrounds, “and they all have unique features that make them look great,” said Dr. Saedi, clinical associate professor of dermatology at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. She then showed images of the same celebrities after they had undergone cosmetic procedures, “and they look so much more similar,” with overarched brows, sculpted noses, enlarged cheeks, and sharply defined jawlines. “Whereas they were all beautiful before individually, now they look very similar,” she said. “This is what we see on social media.”

Referring to the Kardashians as an example of celebrities who have had a lot of aesthetic treatments, look different than they did years ago, and are seen “more and more,” she added, “it’s this repeated overexposure to people on social media, to celebrities, that’s created this different trend of attractiveness.”

This trend also affects patients seeking cosmetic treatments, she noted. Individuals can use an app to alter their appearance, “changing the way they look to create the best version of themselves, they might say, or a filtered version of themselves,” said Dr. Saedi, one of the authors of a commentary on patient perception of beauty on social media published several years ago.

“I tell people, ‘Don’t use filters in your photos. Embrace your beauty.’ I have patients coming in who want to look like the social media photos they’ve curated, maybe larger lips or more definition in their jawline. What they don’t understand is that it takes a long time for that to happen. It’s a process.” In other cases, their desired outcome is not possible due to limits of their individual facial anatomy.

In a study published almost 20 years ago in the journal Perception, Irish researchers manipulated the familiarity of typical and distinctive faces to measure the effect on attractiveness. They found that episodic familiarity affects attractiveness ratings independently of general or structural familiarity.

“So, the more you saw a face, the more familiar that face was to you,” said Dr. Saedi, who was not involved with the study. “Over time, you felt that to be more attractive. I think that’s a lot of what’s going on in the trends that we’re seeing – both in real life and on social media. I do think we need to be more mindful of maintaining features that make an individual unique, while also maintaining their ethnic beauty.”

In an interview at the meeting, Jacqueline D. Watchmaker, MD, a board-certified cosmetic and medical dermatologist who practices in Scottsdale, Ariz., said that she identifies with the notion of racial morphing in her own clinical experience. “Patients come in and specifically ask for chiseled jawlines, high cheekbones, and bigger lips,” Dr. Watchmaker said. “It’s a tricky situation when they ask for [a treatment] you don’t think they need. I prefer a more staged approach to maintain their individuality while giving them a little bit of the aesthetic benefit that they’re looking for.”

Dr. Saedi disclosed ties with AbbVie, Aerolase, Allergan, Alma, Cartessa, Cynosure, Galderma Laboratories, LP, Grand Cosmetics, Revelle Aesthetics, and Revision Skincare. Dr. Watchmaker reported having no financial disclosures.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

HONOLULU – In the opinion of Nazanin A. Saedi, MD, social media-induced dissatisfaction with appearance is getting out of hand in the field of cosmetic dermatology, with the emergence of apps to filter and edit images to the patient’s liking.

This, coupled with

“Overexposure of celebrity images and altered faces on social media have led to a trend of overarching brows, sculpted noses, enlarged cheeks, and sharply defined jawlines,” Dr. Saedi, cochair of the laser and aesthetics surgery center at Dermatology Associates of Plymouth Meeting, Pa., said at the Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by MedscapeLIVE! “These trends have made people of different ethnicities morph into a similar appearance.”

At the meeting, she showed early career images of celebrities from different ethnic backgrounds, “and they all have unique features that make them look great,” said Dr. Saedi, clinical associate professor of dermatology at Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia. She then showed images of the same celebrities after they had undergone cosmetic procedures, “and they look so much more similar,” with overarched brows, sculpted noses, enlarged cheeks, and sharply defined jawlines. “Whereas they were all beautiful before individually, now they look very similar,” she said. “This is what we see on social media.”

Referring to the Kardashians as an example of celebrities who have had a lot of aesthetic treatments, look different than they did years ago, and are seen “more and more,” she added, “it’s this repeated overexposure to people on social media, to celebrities, that’s created this different trend of attractiveness.”

This trend also affects patients seeking cosmetic treatments, she noted. Individuals can use an app to alter their appearance, “changing the way they look to create the best version of themselves, they might say, or a filtered version of themselves,” said Dr. Saedi, one of the authors of a commentary on patient perception of beauty on social media published several years ago.

“I tell people, ‘Don’t use filters in your photos. Embrace your beauty.’ I have patients coming in who want to look like the social media photos they’ve curated, maybe larger lips or more definition in their jawline. What they don’t understand is that it takes a long time for that to happen. It’s a process.” In other cases, their desired outcome is not possible due to limits of their individual facial anatomy.

In a study published almost 20 years ago in the journal Perception, Irish researchers manipulated the familiarity of typical and distinctive faces to measure the effect on attractiveness. They found that episodic familiarity affects attractiveness ratings independently of general or structural familiarity.

“So, the more you saw a face, the more familiar that face was to you,” said Dr. Saedi, who was not involved with the study. “Over time, you felt that to be more attractive. I think that’s a lot of what’s going on in the trends that we’re seeing – both in real life and on social media. I do think we need to be more mindful of maintaining features that make an individual unique, while also maintaining their ethnic beauty.”

In an interview at the meeting, Jacqueline D. Watchmaker, MD, a board-certified cosmetic and medical dermatologist who practices in Scottsdale, Ariz., said that she identifies with the notion of racial morphing in her own clinical experience. “Patients come in and specifically ask for chiseled jawlines, high cheekbones, and bigger lips,” Dr. Watchmaker said. “It’s a tricky situation when they ask for [a treatment] you don’t think they need. I prefer a more staged approach to maintain their individuality while giving them a little bit of the aesthetic benefit that they’re looking for.”

Dr. Saedi disclosed ties with AbbVie, Aerolase, Allergan, Alma, Cartessa, Cynosure, Galderma Laboratories, LP, Grand Cosmetics, Revelle Aesthetics, and Revision Skincare. Dr. Watchmaker reported having no financial disclosures.

Medscape and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

AT THE MEDSCAPELIVE! HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

White male presents with pruritic, scaly, erythematous patches on his feet and left hand

Two feet–one hand syndrome

This condition, also known as ringworm, is a fungal infection caused by a dermatophyte, and presents as a superficial annular or circular rash with a raised, scaly border.

Symptoms include dryness and itchiness, and the lesions may appear red-pink on lighter skin and gray-brown on darker skin types. Although these infections can arise in a variety of combinations, two feet–one hand syndrome occurs in about 60% of cases. Trichophyton rubrum is the most common agent.

Diagnosis is made by patient history, dermoscopic visualization, and staining of skin scraping with KOH or fungal culture. Dermatophytes prefer moist, warm environments, so this disease is prevalent in tropical conditions and associated with moist public areas such as locker rooms and showers. As a result, tinea pedis is also nicknamed “athlete’s foot” for its common presentation in athletes. The fungus spreads easily through contact and can survive on infected surfaces, so patients often self-inoculate by touching/scratching the affected area then touching another body part. Cautions that should be taken to avoid transmission include not sharing personal care products, washing the area and keeping it dry, and avoiding close, humid environments.

The syndrome is highly associated with onychomycosis, which can be more difficult to treat and often requires oral antifungals. Tinea manuum is commonly misdiagnosed as hand dermatitis or eczema and treated with topical steroids, which will exacerbate or flare the tinea.

Two feet–one hand syndrome can typically be treated with over-the-counter topical antifungal medications such as miconazole or clotrimazole. Topical ketoconazole may be prescribed, and oral terbinafine or itraconazole are used in more severe cases when a larger body surface area is affected or in immunocompromised patients.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University, Davie, Fla.; Kiran C. Patel, Tampa Bay Regional Campus; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Cleveland Clinic. Tinea manuum: Symptoms, causes & treatment. 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24063-tinea-manuum.

Ugalde-Trejo NX et al. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2022 Nov 17. doi: 10.1007/s12281-022-00447-9.

Mizumoto J. Cureus. 2021 Dec 27;13(12):e20758.

Two feet–one hand syndrome

This condition, also known as ringworm, is a fungal infection caused by a dermatophyte, and presents as a superficial annular or circular rash with a raised, scaly border.

Symptoms include dryness and itchiness, and the lesions may appear red-pink on lighter skin and gray-brown on darker skin types. Although these infections can arise in a variety of combinations, two feet–one hand syndrome occurs in about 60% of cases. Trichophyton rubrum is the most common agent.

Diagnosis is made by patient history, dermoscopic visualization, and staining of skin scraping with KOH or fungal culture. Dermatophytes prefer moist, warm environments, so this disease is prevalent in tropical conditions and associated with moist public areas such as locker rooms and showers. As a result, tinea pedis is also nicknamed “athlete’s foot” for its common presentation in athletes. The fungus spreads easily through contact and can survive on infected surfaces, so patients often self-inoculate by touching/scratching the affected area then touching another body part. Cautions that should be taken to avoid transmission include not sharing personal care products, washing the area and keeping it dry, and avoiding close, humid environments.

The syndrome is highly associated with onychomycosis, which can be more difficult to treat and often requires oral antifungals. Tinea manuum is commonly misdiagnosed as hand dermatitis or eczema and treated with topical steroids, which will exacerbate or flare the tinea.

Two feet–one hand syndrome can typically be treated with over-the-counter topical antifungal medications such as miconazole or clotrimazole. Topical ketoconazole may be prescribed, and oral terbinafine or itraconazole are used in more severe cases when a larger body surface area is affected or in immunocompromised patients.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University, Davie, Fla.; Kiran C. Patel, Tampa Bay Regional Campus; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Cleveland Clinic. Tinea manuum: Symptoms, causes & treatment. 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24063-tinea-manuum.

Ugalde-Trejo NX et al. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2022 Nov 17. doi: 10.1007/s12281-022-00447-9.

Mizumoto J. Cureus. 2021 Dec 27;13(12):e20758.

Two feet–one hand syndrome

This condition, also known as ringworm, is a fungal infection caused by a dermatophyte, and presents as a superficial annular or circular rash with a raised, scaly border.

Symptoms include dryness and itchiness, and the lesions may appear red-pink on lighter skin and gray-brown on darker skin types. Although these infections can arise in a variety of combinations, two feet–one hand syndrome occurs in about 60% of cases. Trichophyton rubrum is the most common agent.

Diagnosis is made by patient history, dermoscopic visualization, and staining of skin scraping with KOH or fungal culture. Dermatophytes prefer moist, warm environments, so this disease is prevalent in tropical conditions and associated with moist public areas such as locker rooms and showers. As a result, tinea pedis is also nicknamed “athlete’s foot” for its common presentation in athletes. The fungus spreads easily through contact and can survive on infected surfaces, so patients often self-inoculate by touching/scratching the affected area then touching another body part. Cautions that should be taken to avoid transmission include not sharing personal care products, washing the area and keeping it dry, and avoiding close, humid environments.

The syndrome is highly associated with onychomycosis, which can be more difficult to treat and often requires oral antifungals. Tinea manuum is commonly misdiagnosed as hand dermatitis or eczema and treated with topical steroids, which will exacerbate or flare the tinea.

Two feet–one hand syndrome can typically be treated with over-the-counter topical antifungal medications such as miconazole or clotrimazole. Topical ketoconazole may be prescribed, and oral terbinafine or itraconazole are used in more severe cases when a larger body surface area is affected or in immunocompromised patients.

This case and photo were submitted by Lucas Shapiro, BS, Nova Southeastern University, Davie, Fla.; Kiran C. Patel, Tampa Bay Regional Campus; and Dr. Bilu Martin.

Dr. Bilu Martin is a board-certified dermatologist in private practice at Premier Dermatology, MD, in Aventura, Fla. More diagnostic cases are available at mdedge.com/dermatology. To submit a case for possible publication, send an email to dermnews@mdedge.com.

References

Cleveland Clinic. Tinea manuum: Symptoms, causes & treatment. 2022. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/24063-tinea-manuum.

Ugalde-Trejo NX et al. Curr Fungal Infect Rep. 2022 Nov 17. doi: 10.1007/s12281-022-00447-9.

Mizumoto J. Cureus. 2021 Dec 27;13(12):e20758.

Telehealth doctor indicted on health care fraud, opioid distribution charges

Sangita Patel, MD, 50, practiced at Advance Medical Home Physicians in Troy.

According to court documents, between July 2020 and June 2022 Patel was responsible for submitting Medicare claims for improper telehealth visits she didn’t conduct herself.

Dr. Patel, who accepted patients who paid in cash as well as those with Medicare and Medicaid coverage, billed approximately $3.4 million to Medicare between 2018 and 2022, according to court documents. An unusual number of these visits were billed using complex codes, an indication of health care fraud. The investigation also found that on many days, Dr. Patel billed for more than 24 hours of services. During this period, according to the document, 76% of Dr. Patel’s Medicare reimbursements were for telehealth.

Prosecutors say that Dr. Patel prescribed Schedule II controlled substances to more than 90% of the patients in these telehealth visits. She delegated her prescription authority to an unlicensed medical assistant. Through undercover visits and cell site search warrant data, the investigation found that Dr. Patel directed patients to contact, via cell phone, this assistant, who then entered electronic prescriptions into the electronic medical records system. Dr. Patel then signed the prescriptions and sent them to the pharmacies without ever interacting with the patients. Prosecutors also used text messages, obtained by search warrant, between Dr. Patel and her assistant and between the assistant and undercover informers to build their case.

Dr. Patel is also accused of referring patients to other providers, who in turn billed Medicare for claims associated with those patients. Advance Medical received $143,000 from these providers, potentially in violation of anti-kickback laws, according to bank records obtained by subpoena.

If convicted, Dr. Patel could be sentenced to up to 10 years in federal prison.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sangita Patel, MD, 50, practiced at Advance Medical Home Physicians in Troy.

According to court documents, between July 2020 and June 2022 Patel was responsible for submitting Medicare claims for improper telehealth visits she didn’t conduct herself.

Dr. Patel, who accepted patients who paid in cash as well as those with Medicare and Medicaid coverage, billed approximately $3.4 million to Medicare between 2018 and 2022, according to court documents. An unusual number of these visits were billed using complex codes, an indication of health care fraud. The investigation also found that on many days, Dr. Patel billed for more than 24 hours of services. During this period, according to the document, 76% of Dr. Patel’s Medicare reimbursements were for telehealth.

Prosecutors say that Dr. Patel prescribed Schedule II controlled substances to more than 90% of the patients in these telehealth visits. She delegated her prescription authority to an unlicensed medical assistant. Through undercover visits and cell site search warrant data, the investigation found that Dr. Patel directed patients to contact, via cell phone, this assistant, who then entered electronic prescriptions into the electronic medical records system. Dr. Patel then signed the prescriptions and sent them to the pharmacies without ever interacting with the patients. Prosecutors also used text messages, obtained by search warrant, between Dr. Patel and her assistant and between the assistant and undercover informers to build their case.

Dr. Patel is also accused of referring patients to other providers, who in turn billed Medicare for claims associated with those patients. Advance Medical received $143,000 from these providers, potentially in violation of anti-kickback laws, according to bank records obtained by subpoena.

If convicted, Dr. Patel could be sentenced to up to 10 years in federal prison.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Sangita Patel, MD, 50, practiced at Advance Medical Home Physicians in Troy.

According to court documents, between July 2020 and June 2022 Patel was responsible for submitting Medicare claims for improper telehealth visits she didn’t conduct herself.

Dr. Patel, who accepted patients who paid in cash as well as those with Medicare and Medicaid coverage, billed approximately $3.4 million to Medicare between 2018 and 2022, according to court documents. An unusual number of these visits were billed using complex codes, an indication of health care fraud. The investigation also found that on many days, Dr. Patel billed for more than 24 hours of services. During this period, according to the document, 76% of Dr. Patel’s Medicare reimbursements were for telehealth.

Prosecutors say that Dr. Patel prescribed Schedule II controlled substances to more than 90% of the patients in these telehealth visits. She delegated her prescription authority to an unlicensed medical assistant. Through undercover visits and cell site search warrant data, the investigation found that Dr. Patel directed patients to contact, via cell phone, this assistant, who then entered electronic prescriptions into the electronic medical records system. Dr. Patel then signed the prescriptions and sent them to the pharmacies without ever interacting with the patients. Prosecutors also used text messages, obtained by search warrant, between Dr. Patel and her assistant and between the assistant and undercover informers to build their case.

Dr. Patel is also accused of referring patients to other providers, who in turn billed Medicare for claims associated with those patients. Advance Medical received $143,000 from these providers, potentially in violation of anti-kickback laws, according to bank records obtained by subpoena.

If convicted, Dr. Patel could be sentenced to up to 10 years in federal prison.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Biologics show signs of delaying arthritis in psoriasis patients

Patients with psoriasis treated with interleukin-12/23 inhibitors or IL-23 inhibitors were less likely to develop inflammatory arthritis, compared with those treated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, according to findings from a large retrospective study.

While previous retrospective cohort studies have found biologic therapies for psoriasis can reduce the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis when compared with other treatments such as phototherapy and oral nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, this analysis is the first to compare classes of biologics, Shikha Singla, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and colleagues wrote in The Lancet Rheumatology.

In the analysis, researchers used the TriNetX database, which contains deidentified data from electronic medical health records from health care organizations across the United States. The study included adults diagnosed with psoriasis who were newly prescribed a biologic approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriasis. Biologics were defined by drug class: anti-TNF, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-23, and anti–IL-12/23. Any patient with a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis or other inflammatory arthritis prior to receiving a biologic prescription or within 2 weeks of receiving the prescription were excluded.

The researchers identified 15,501 eligible patients diagnosed with psoriasis during Jan. 1, 2014, to June 1, 2022, with an average follow-up time of 2.4 years. The researchers chose to start the study period in 2014 because the first non–anti-TNF drug for psoriatic arthritis was approved by the FDA in 2013 – the anti–IL-12/23 drug ustekinumab. During the study period, 976 patients developed inflammatory arthritis and were diagnosed on average 528 days after their biologic prescription.

In a multivariable analysis, the researchers found that patients prescribed IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab [Tremfya], risankizumab [Skyrizi], tildrakizumab [Ilumya]) were nearly 60% less likely (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.17–0.95) to develop inflammatory arthritis than were patients taking TNF inhibitors (infliximab [Remicade], adalimumab [Humira], etanercept [Enbrel], golimumab [Simponi], certolizumab pegol [Cimzia]). The risk of developing arthritis was 42% lower (aHR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43-0.76) with the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara), but there was no difference in outcomes among patients taking with IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab [Cosentyx], ixekizumab [Taltz], or brodalumab [Siliq]), compared with TNF inhibitors. For the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, all sensitivity analyses did not change this association. For IL-23 inhibitors, the results persisted when excluding patients who developed arthritis within 3 or 6 months after first biologic prescription and when using a higher diagnostic threshold for incident arthritis.

“There is a lot of interest in understanding if treatment of psoriasis will prevent onset of psoriatic arthritis,” said Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, director of the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who was asked to comment on the results.

“To date, the literature is inconclusive with some studies suggesting biologics reduce risk of PsA, whereas others suggest biologic use is associated with an increased risk of PsA,” he said. “The current study is unique in that it compares biologic classes to one another and suggests that IL-12/23 and IL-23 biologics are associated with a reduced risk of PsA compared to psoriasis patients treated with TNF inhibitors and no difference was found between TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors.”

While the study posed an interesting research question, “I wouldn’t use these results to actually change treatment patterns,” Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. She coauthored a commentary on the analysis. Dr. Gelfand also emphasized that this bias may have influenced the results and that these findings “should not impact clinical practice at this time.”

Although the analyses were strong, Dr. Ogdie-Beatty noted, there are inherent biases in this type of observational data that cannot be overcome. For example, if a patient comes into a dermatologist’s office with psoriasis and also has joint pain, the dermatologist may suspect that a patient could also have psoriatic arthritis and would be more likely to choose a drug that will work well for both of these conditions.

“The drugs that are known to work best for psoriatic arthritis are the TNF inhibitors and the IL-17 inhibitors,” she said. So, while the analysis found these medications were associated with higher incidence of PsA, the dermatologist was possibly treating presumptive arthritis and the patient had yet to be referred to a rheumatologist to confirm the diagnosis.

The researchers noted that they attempted to mitigate these issues by requiring that patients have at least 1 year of follow-up before receiving biologic prescription “to capture only the patients with no previous codes for any type of arthritis,” as well as conducting six sensitivity analyses.

The authors, and Dr. Ogdie-Beatty and Dr. Gelfand agreed that more research is necessary to confirm these findings. A large randomized trial may be “prohibitively expensive,” the authors noted, but pooled analyses from previous clinical trials may help with this issue. “We identified 14 published randomized trials that did head-to-head comparisons of different biologic classes with regard to effect on psoriasis, and these trials collectively contained data on more than 13,000 patients. Pooled analyses of these data could confirm the findings of the present study and would be adequately powered.”

But that approach also has limitations, as psoriatic arthritis was not assessed an outcome in these studies, Dr. Ogdie-Beatty noted. Randomizing patients who are already at a higher risk of developing PsA to different biologics could be one approach to address these questions without needing such a large patient population.

The study was conducted without outside funding or industry involvement. Dr. Singla reported no relevant financial relationships with industry, but several coauthors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies that market biologics for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Dr. Ogdie-Beatty reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, CorEvitas, Gilead, Happify Health, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand reported financial relationships with Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, FIDE, Lilly, Leo, Janssen Biologics, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand is a deputy editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

This article was updated 3/15/23.

Patients with psoriasis treated with interleukin-12/23 inhibitors or IL-23 inhibitors were less likely to develop inflammatory arthritis, compared with those treated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, according to findings from a large retrospective study.

While previous retrospective cohort studies have found biologic therapies for psoriasis can reduce the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis when compared with other treatments such as phototherapy and oral nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, this analysis is the first to compare classes of biologics, Shikha Singla, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and colleagues wrote in The Lancet Rheumatology.

In the analysis, researchers used the TriNetX database, which contains deidentified data from electronic medical health records from health care organizations across the United States. The study included adults diagnosed with psoriasis who were newly prescribed a biologic approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriasis. Biologics were defined by drug class: anti-TNF, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-23, and anti–IL-12/23. Any patient with a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis or other inflammatory arthritis prior to receiving a biologic prescription or within 2 weeks of receiving the prescription were excluded.

The researchers identified 15,501 eligible patients diagnosed with psoriasis during Jan. 1, 2014, to June 1, 2022, with an average follow-up time of 2.4 years. The researchers chose to start the study period in 2014 because the first non–anti-TNF drug for psoriatic arthritis was approved by the FDA in 2013 – the anti–IL-12/23 drug ustekinumab. During the study period, 976 patients developed inflammatory arthritis and were diagnosed on average 528 days after their biologic prescription.

In a multivariable analysis, the researchers found that patients prescribed IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab [Tremfya], risankizumab [Skyrizi], tildrakizumab [Ilumya]) were nearly 60% less likely (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.17–0.95) to develop inflammatory arthritis than were patients taking TNF inhibitors (infliximab [Remicade], adalimumab [Humira], etanercept [Enbrel], golimumab [Simponi], certolizumab pegol [Cimzia]). The risk of developing arthritis was 42% lower (aHR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43-0.76) with the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara), but there was no difference in outcomes among patients taking with IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab [Cosentyx], ixekizumab [Taltz], or brodalumab [Siliq]), compared with TNF inhibitors. For the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, all sensitivity analyses did not change this association. For IL-23 inhibitors, the results persisted when excluding patients who developed arthritis within 3 or 6 months after first biologic prescription and when using a higher diagnostic threshold for incident arthritis.

“There is a lot of interest in understanding if treatment of psoriasis will prevent onset of psoriatic arthritis,” said Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, director of the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who was asked to comment on the results.

“To date, the literature is inconclusive with some studies suggesting biologics reduce risk of PsA, whereas others suggest biologic use is associated with an increased risk of PsA,” he said. “The current study is unique in that it compares biologic classes to one another and suggests that IL-12/23 and IL-23 biologics are associated with a reduced risk of PsA compared to psoriasis patients treated with TNF inhibitors and no difference was found between TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors.”

While the study posed an interesting research question, “I wouldn’t use these results to actually change treatment patterns,” Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. She coauthored a commentary on the analysis. Dr. Gelfand also emphasized that this bias may have influenced the results and that these findings “should not impact clinical practice at this time.”

Although the analyses were strong, Dr. Ogdie-Beatty noted, there are inherent biases in this type of observational data that cannot be overcome. For example, if a patient comes into a dermatologist’s office with psoriasis and also has joint pain, the dermatologist may suspect that a patient could also have psoriatic arthritis and would be more likely to choose a drug that will work well for both of these conditions.

“The drugs that are known to work best for psoriatic arthritis are the TNF inhibitors and the IL-17 inhibitors,” she said. So, while the analysis found these medications were associated with higher incidence of PsA, the dermatologist was possibly treating presumptive arthritis and the patient had yet to be referred to a rheumatologist to confirm the diagnosis.

The researchers noted that they attempted to mitigate these issues by requiring that patients have at least 1 year of follow-up before receiving biologic prescription “to capture only the patients with no previous codes for any type of arthritis,” as well as conducting six sensitivity analyses.

The authors, and Dr. Ogdie-Beatty and Dr. Gelfand agreed that more research is necessary to confirm these findings. A large randomized trial may be “prohibitively expensive,” the authors noted, but pooled analyses from previous clinical trials may help with this issue. “We identified 14 published randomized trials that did head-to-head comparisons of different biologic classes with regard to effect on psoriasis, and these trials collectively contained data on more than 13,000 patients. Pooled analyses of these data could confirm the findings of the present study and would be adequately powered.”

But that approach also has limitations, as psoriatic arthritis was not assessed an outcome in these studies, Dr. Ogdie-Beatty noted. Randomizing patients who are already at a higher risk of developing PsA to different biologics could be one approach to address these questions without needing such a large patient population.

The study was conducted without outside funding or industry involvement. Dr. Singla reported no relevant financial relationships with industry, but several coauthors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies that market biologics for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Dr. Ogdie-Beatty reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, CorEvitas, Gilead, Happify Health, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand reported financial relationships with Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, FIDE, Lilly, Leo, Janssen Biologics, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand is a deputy editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

This article was updated 3/15/23.

Patients with psoriasis treated with interleukin-12/23 inhibitors or IL-23 inhibitors were less likely to develop inflammatory arthritis, compared with those treated with tumor necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitors, according to findings from a large retrospective study.

While previous retrospective cohort studies have found biologic therapies for psoriasis can reduce the risk of developing psoriatic arthritis when compared with other treatments such as phototherapy and oral nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs, this analysis is the first to compare classes of biologics, Shikha Singla, MD, of the Medical College of Wisconsin, Milwaukee, and colleagues wrote in The Lancet Rheumatology.

In the analysis, researchers used the TriNetX database, which contains deidentified data from electronic medical health records from health care organizations across the United States. The study included adults diagnosed with psoriasis who were newly prescribed a biologic approved by the Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of psoriasis. Biologics were defined by drug class: anti-TNF, anti-IL-17, anti-IL-23, and anti–IL-12/23. Any patient with a diagnosis of psoriatic arthritis or other inflammatory arthritis prior to receiving a biologic prescription or within 2 weeks of receiving the prescription were excluded.

The researchers identified 15,501 eligible patients diagnosed with psoriasis during Jan. 1, 2014, to June 1, 2022, with an average follow-up time of 2.4 years. The researchers chose to start the study period in 2014 because the first non–anti-TNF drug for psoriatic arthritis was approved by the FDA in 2013 – the anti–IL-12/23 drug ustekinumab. During the study period, 976 patients developed inflammatory arthritis and were diagnosed on average 528 days after their biologic prescription.

In a multivariable analysis, the researchers found that patients prescribed IL-23 inhibitors (guselkumab [Tremfya], risankizumab [Skyrizi], tildrakizumab [Ilumya]) were nearly 60% less likely (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.41; 95% confidence interval, 0.17–0.95) to develop inflammatory arthritis than were patients taking TNF inhibitors (infliximab [Remicade], adalimumab [Humira], etanercept [Enbrel], golimumab [Simponi], certolizumab pegol [Cimzia]). The risk of developing arthritis was 42% lower (aHR, 0.58; 95% CI, 0.43-0.76) with the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab (Stelara), but there was no difference in outcomes among patients taking with IL-17 inhibitors (secukinumab [Cosentyx], ixekizumab [Taltz], or brodalumab [Siliq]), compared with TNF inhibitors. For the IL-12/23 inhibitor ustekinumab, all sensitivity analyses did not change this association. For IL-23 inhibitors, the results persisted when excluding patients who developed arthritis within 3 or 6 months after first biologic prescription and when using a higher diagnostic threshold for incident arthritis.

“There is a lot of interest in understanding if treatment of psoriasis will prevent onset of psoriatic arthritis,” said Joel M. Gelfand, MD, MSCE, director of the Psoriasis and Phototherapy Treatment Center at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, who was asked to comment on the results.

“To date, the literature is inconclusive with some studies suggesting biologics reduce risk of PsA, whereas others suggest biologic use is associated with an increased risk of PsA,” he said. “The current study is unique in that it compares biologic classes to one another and suggests that IL-12/23 and IL-23 biologics are associated with a reduced risk of PsA compared to psoriasis patients treated with TNF inhibitors and no difference was found between TNF inhibitors and IL-17 inhibitors.”

While the study posed an interesting research question, “I wouldn’t use these results to actually change treatment patterns,” Alexis R. Ogdie-Beatty, MD, an associate professor of medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. She coauthored a commentary on the analysis. Dr. Gelfand also emphasized that this bias may have influenced the results and that these findings “should not impact clinical practice at this time.”

Although the analyses were strong, Dr. Ogdie-Beatty noted, there are inherent biases in this type of observational data that cannot be overcome. For example, if a patient comes into a dermatologist’s office with psoriasis and also has joint pain, the dermatologist may suspect that a patient could also have psoriatic arthritis and would be more likely to choose a drug that will work well for both of these conditions.

“The drugs that are known to work best for psoriatic arthritis are the TNF inhibitors and the IL-17 inhibitors,” she said. So, while the analysis found these medications were associated with higher incidence of PsA, the dermatologist was possibly treating presumptive arthritis and the patient had yet to be referred to a rheumatologist to confirm the diagnosis.

The researchers noted that they attempted to mitigate these issues by requiring that patients have at least 1 year of follow-up before receiving biologic prescription “to capture only the patients with no previous codes for any type of arthritis,” as well as conducting six sensitivity analyses.

The authors, and Dr. Ogdie-Beatty and Dr. Gelfand agreed that more research is necessary to confirm these findings. A large randomized trial may be “prohibitively expensive,” the authors noted, but pooled analyses from previous clinical trials may help with this issue. “We identified 14 published randomized trials that did head-to-head comparisons of different biologic classes with regard to effect on psoriasis, and these trials collectively contained data on more than 13,000 patients. Pooled analyses of these data could confirm the findings of the present study and would be adequately powered.”

But that approach also has limitations, as psoriatic arthritis was not assessed an outcome in these studies, Dr. Ogdie-Beatty noted. Randomizing patients who are already at a higher risk of developing PsA to different biologics could be one approach to address these questions without needing such a large patient population.

The study was conducted without outside funding or industry involvement. Dr. Singla reported no relevant financial relationships with industry, but several coauthors reported financial relationships with pharmaceutical companies that market biologics for psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Dr. Ogdie-Beatty reported financial relationships with AbbVie, Amgen, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celgene, CorEvitas, Gilead, Happify Health, Janssen, Lilly, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand reported financial relationships with Abbvie, Amgen, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, FIDE, Lilly, Leo, Janssen Biologics, Novartis, Pfizer, and UCB. Dr. Gelfand is a deputy editor for the Journal of Investigative Dermatology.

This article was updated 3/15/23.

FROM LANCET RHEUMATOLOGY

We have seen the future of healthy muffins, and its name is Roselle

Get ‘em while they’re hot … for your health

Today on the Eating Channel, it’s a very special episode of “Much Ado About Muffin.”

The muffin. For some of us, it’s a good way to pretend we’re not having dessert for breakfast. A bran muffin can be loaded with calcium and fiber, and our beloved blueberry is full of yummy antioxidants and vitamins. Definitely not dessert.

Well, the muffin denial can stop there because there’s a new flavor on the scene, and research suggests it may actually be healthy. (Disclaimer: Muffin may not be considered healthy in Norway.) This new muffin has a name, Roselle, that comes from the calyx extract used in it, which is found in the Hibiscus sabdariffa plant of the same name.

Now, when it comes to new foods, especially ones that are supposed to be healthy, the No. 1 criteria is the same: It has to taste good. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Amity University in India agreed, but they also set out to make it nutritionally valuable and give it a long shelf life without the addition of preservatives.

Sounds like a tall order, but they figured it out.

Not only is it tasty, but the properties of it could rival your morning multivitamin. Hibiscus extract has huge amounts of antioxidants, like phenolics, which are believed to help prevent cell membrane damage. Foods like vegetables, flax seed, and whole grains also have these antioxidants, but why not just have a Roselle muffin instead? You also get a dose of ascorbic acid without the glass of OJ in the morning.

The ascorbic acid, however, is not there just to help you. It also helps to check the researcher’s third box, shelf life. These naturally rosy-colored pastries will stay mold-free for 6 days without refrigeration at room temperature and without added preservatives.

Our guess, though, is they won’t be on the kitchen counter long enough to find out.

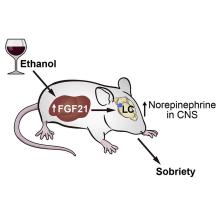

A sobering proposition

If Hollywood is to be believed, there’s no amount of drunkenness that can’t be cured with a cup of coffee or a stern slap in the face. Unfortunately, here in the real world the only thing that can make you less drunk is time. Maybe next time you’ll stop after that seventh Manhattan.

But what if we could beat time? What if there’s an actual sobriety drug out there?

Say hello to fibroblast growth factor 21. Although the liver already does good work filtering out what is essentially poison, it then goes the extra mile and produces fibroblast growth factor 21 (or, as her friends call her, FGF21), a hormone that suppresses the desire to drink, makes you desire water, and protects the liver all at the same time.

Now, FGF21 in its current role is great, but if you’ve ever seen or been a drunk person before, you’ve experienced the lack of interest in listening to reason, especially when it comes from within our own bodies. Who are you to tell us what to do, body? You’re not the boss of us! So a group of scientists decided to push the limits of FGF21. Could it do more than it already does?

First off, they genetically altered a group of mice so that they didn’t produce FGF21 on their own. Then they got them drunk. We’re going to assume they built a scale model of the bar from Cheers and had the mice filter in through the front door as they served their subjects beer out of tiny little glasses.

Once the mice were nice and liquored up, some were given a treatment of FGF21 while others were given a placebo. Lo and behold, the mice given FGF21 recovered about 50% faster than those that received the control treatment. Not exactly instant, but 50% is nothing to sniff at.

Before you bring your FGF21 supplement to the bar, though, this research only applies to mice. We don’t know if it works in people. And make sure you stick to booze. If your choice of intoxication is a bit more exotic, FGF21 isn’t going to do anything for you. Yes, the scientists tried. Yes, those mice are living a very interesting life. And yes, we are jealous of drugged-up lab mice.

Supersize your imagination, shrink your snacks

Have you ever heard of the meal-recall effect? Did you know that, in England, a biscuit is really a cookie? Did you also know that the magazine Bon Appétit is not the same as the peer-reviewed journal Appetite? We do … now.

The meal-recall effect is the subsequent reduction in snacking that comes from remembering a recent meal. It was used to great effect in a recent study conducted at the University of Cambridge, which is in England, where they feed their experimental humans cookies but, for some reason, call them biscuits.

For the first part of the study, the participants were invited to dine at Che Laboratory, where they “were given a microwave ready meal of rice and sauce and a cup of water,” according to a statement from the university. As our Uncle Ernie would say, “Gourmet all the way.”

The test subjects were instructed not to eat anything for 3 hours and “then invited back to the lab to perform imagination tasks.” Those who did come back were randomly divided into five different groups, each with a different task:

- Imagine moving their recent lunch at the lab around a plate.

- Recall eating their recent lunch in detail.

- Imagine that the lunch was twice as big and filling as it really was.

- Look at a photograph of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce and write a description of it before imagining moving the food around a plate.

- Look at a photo of paper clips and rubber bands and imagine moving them around.

Now, at last, we get to the biscuits/cookies, which were the subject of a taste test that “was simply a rouse for covertly assessing snacking,” the investigators explained. As part of that test, participants were told they could eat as many biscuits as they wanted.

When the tables were cleared and the leftovers examined, the group that imagined spaghetti hoops had eaten the most biscuits (75.9 g), followed by the group that imagined paper clips (75.5 g), the moving-their-lunch-around-the-plate group (72.0 g), and the group that relived eating their lunch (70.0 g).

In a victory for the meal-recall effect, the people who imagined their meal being twice as big ate the fewest biscuits (51.1 g). “Your mind can be more powerful than your stomach in dictating how much you eat,” lead author Joanna Szypula, PhD, said in the university statement.

Oh! One more thing. The study appeared in Appetite, which is a peer-reviewed journal, not in Bon Appétit, which is not a peer-reviewed journal. Thanks to the fine folks at both publications for pointing that out to us.

Get ‘em while they’re hot … for your health

Today on the Eating Channel, it’s a very special episode of “Much Ado About Muffin.”

The muffin. For some of us, it’s a good way to pretend we’re not having dessert for breakfast. A bran muffin can be loaded with calcium and fiber, and our beloved blueberry is full of yummy antioxidants and vitamins. Definitely not dessert.

Well, the muffin denial can stop there because there’s a new flavor on the scene, and research suggests it may actually be healthy. (Disclaimer: Muffin may not be considered healthy in Norway.) This new muffin has a name, Roselle, that comes from the calyx extract used in it, which is found in the Hibiscus sabdariffa plant of the same name.

Now, when it comes to new foods, especially ones that are supposed to be healthy, the No. 1 criteria is the same: It has to taste good. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Amity University in India agreed, but they also set out to make it nutritionally valuable and give it a long shelf life without the addition of preservatives.

Sounds like a tall order, but they figured it out.

Not only is it tasty, but the properties of it could rival your morning multivitamin. Hibiscus extract has huge amounts of antioxidants, like phenolics, which are believed to help prevent cell membrane damage. Foods like vegetables, flax seed, and whole grains also have these antioxidants, but why not just have a Roselle muffin instead? You also get a dose of ascorbic acid without the glass of OJ in the morning.

The ascorbic acid, however, is not there just to help you. It also helps to check the researcher’s third box, shelf life. These naturally rosy-colored pastries will stay mold-free for 6 days without refrigeration at room temperature and without added preservatives.

Our guess, though, is they won’t be on the kitchen counter long enough to find out.

A sobering proposition

If Hollywood is to be believed, there’s no amount of drunkenness that can’t be cured with a cup of coffee or a stern slap in the face. Unfortunately, here in the real world the only thing that can make you less drunk is time. Maybe next time you’ll stop after that seventh Manhattan.

But what if we could beat time? What if there’s an actual sobriety drug out there?

Say hello to fibroblast growth factor 21. Although the liver already does good work filtering out what is essentially poison, it then goes the extra mile and produces fibroblast growth factor 21 (or, as her friends call her, FGF21), a hormone that suppresses the desire to drink, makes you desire water, and protects the liver all at the same time.

Now, FGF21 in its current role is great, but if you’ve ever seen or been a drunk person before, you’ve experienced the lack of interest in listening to reason, especially when it comes from within our own bodies. Who are you to tell us what to do, body? You’re not the boss of us! So a group of scientists decided to push the limits of FGF21. Could it do more than it already does?

First off, they genetically altered a group of mice so that they didn’t produce FGF21 on their own. Then they got them drunk. We’re going to assume they built a scale model of the bar from Cheers and had the mice filter in through the front door as they served their subjects beer out of tiny little glasses.

Once the mice were nice and liquored up, some were given a treatment of FGF21 while others were given a placebo. Lo and behold, the mice given FGF21 recovered about 50% faster than those that received the control treatment. Not exactly instant, but 50% is nothing to sniff at.

Before you bring your FGF21 supplement to the bar, though, this research only applies to mice. We don’t know if it works in people. And make sure you stick to booze. If your choice of intoxication is a bit more exotic, FGF21 isn’t going to do anything for you. Yes, the scientists tried. Yes, those mice are living a very interesting life. And yes, we are jealous of drugged-up lab mice.

Supersize your imagination, shrink your snacks

Have you ever heard of the meal-recall effect? Did you know that, in England, a biscuit is really a cookie? Did you also know that the magazine Bon Appétit is not the same as the peer-reviewed journal Appetite? We do … now.

The meal-recall effect is the subsequent reduction in snacking that comes from remembering a recent meal. It was used to great effect in a recent study conducted at the University of Cambridge, which is in England, where they feed their experimental humans cookies but, for some reason, call them biscuits.

For the first part of the study, the participants were invited to dine at Che Laboratory, where they “were given a microwave ready meal of rice and sauce and a cup of water,” according to a statement from the university. As our Uncle Ernie would say, “Gourmet all the way.”

The test subjects were instructed not to eat anything for 3 hours and “then invited back to the lab to perform imagination tasks.” Those who did come back were randomly divided into five different groups, each with a different task:

- Imagine moving their recent lunch at the lab around a plate.

- Recall eating their recent lunch in detail.

- Imagine that the lunch was twice as big and filling as it really was.

- Look at a photograph of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce and write a description of it before imagining moving the food around a plate.

- Look at a photo of paper clips and rubber bands and imagine moving them around.

Now, at last, we get to the biscuits/cookies, which were the subject of a taste test that “was simply a rouse for covertly assessing snacking,” the investigators explained. As part of that test, participants were told they could eat as many biscuits as they wanted.

When the tables were cleared and the leftovers examined, the group that imagined spaghetti hoops had eaten the most biscuits (75.9 g), followed by the group that imagined paper clips (75.5 g), the moving-their-lunch-around-the-plate group (72.0 g), and the group that relived eating their lunch (70.0 g).

In a victory for the meal-recall effect, the people who imagined their meal being twice as big ate the fewest biscuits (51.1 g). “Your mind can be more powerful than your stomach in dictating how much you eat,” lead author Joanna Szypula, PhD, said in the university statement.

Oh! One more thing. The study appeared in Appetite, which is a peer-reviewed journal, not in Bon Appétit, which is not a peer-reviewed journal. Thanks to the fine folks at both publications for pointing that out to us.

Get ‘em while they’re hot … for your health

Today on the Eating Channel, it’s a very special episode of “Much Ado About Muffin.”

The muffin. For some of us, it’s a good way to pretend we’re not having dessert for breakfast. A bran muffin can be loaded with calcium and fiber, and our beloved blueberry is full of yummy antioxidants and vitamins. Definitely not dessert.

Well, the muffin denial can stop there because there’s a new flavor on the scene, and research suggests it may actually be healthy. (Disclaimer: Muffin may not be considered healthy in Norway.) This new muffin has a name, Roselle, that comes from the calyx extract used in it, which is found in the Hibiscus sabdariffa plant of the same name.

Now, when it comes to new foods, especially ones that are supposed to be healthy, the No. 1 criteria is the same: It has to taste good. Researchers at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology and Amity University in India agreed, but they also set out to make it nutritionally valuable and give it a long shelf life without the addition of preservatives.

Sounds like a tall order, but they figured it out.

Not only is it tasty, but the properties of it could rival your morning multivitamin. Hibiscus extract has huge amounts of antioxidants, like phenolics, which are believed to help prevent cell membrane damage. Foods like vegetables, flax seed, and whole grains also have these antioxidants, but why not just have a Roselle muffin instead? You also get a dose of ascorbic acid without the glass of OJ in the morning.

The ascorbic acid, however, is not there just to help you. It also helps to check the researcher’s third box, shelf life. These naturally rosy-colored pastries will stay mold-free for 6 days without refrigeration at room temperature and without added preservatives.

Our guess, though, is they won’t be on the kitchen counter long enough to find out.

A sobering proposition

If Hollywood is to be believed, there’s no amount of drunkenness that can’t be cured with a cup of coffee or a stern slap in the face. Unfortunately, here in the real world the only thing that can make you less drunk is time. Maybe next time you’ll stop after that seventh Manhattan.

But what if we could beat time? What if there’s an actual sobriety drug out there?

Say hello to fibroblast growth factor 21. Although the liver already does good work filtering out what is essentially poison, it then goes the extra mile and produces fibroblast growth factor 21 (or, as her friends call her, FGF21), a hormone that suppresses the desire to drink, makes you desire water, and protects the liver all at the same time.

Now, FGF21 in its current role is great, but if you’ve ever seen or been a drunk person before, you’ve experienced the lack of interest in listening to reason, especially when it comes from within our own bodies. Who are you to tell us what to do, body? You’re not the boss of us! So a group of scientists decided to push the limits of FGF21. Could it do more than it already does?

First off, they genetically altered a group of mice so that they didn’t produce FGF21 on their own. Then they got them drunk. We’re going to assume they built a scale model of the bar from Cheers and had the mice filter in through the front door as they served their subjects beer out of tiny little glasses.

Once the mice were nice and liquored up, some were given a treatment of FGF21 while others were given a placebo. Lo and behold, the mice given FGF21 recovered about 50% faster than those that received the control treatment. Not exactly instant, but 50% is nothing to sniff at.

Before you bring your FGF21 supplement to the bar, though, this research only applies to mice. We don’t know if it works in people. And make sure you stick to booze. If your choice of intoxication is a bit more exotic, FGF21 isn’t going to do anything for you. Yes, the scientists tried. Yes, those mice are living a very interesting life. And yes, we are jealous of drugged-up lab mice.

Supersize your imagination, shrink your snacks

Have you ever heard of the meal-recall effect? Did you know that, in England, a biscuit is really a cookie? Did you also know that the magazine Bon Appétit is not the same as the peer-reviewed journal Appetite? We do … now.

The meal-recall effect is the subsequent reduction in snacking that comes from remembering a recent meal. It was used to great effect in a recent study conducted at the University of Cambridge, which is in England, where they feed their experimental humans cookies but, for some reason, call them biscuits.

For the first part of the study, the participants were invited to dine at Che Laboratory, where they “were given a microwave ready meal of rice and sauce and a cup of water,” according to a statement from the university. As our Uncle Ernie would say, “Gourmet all the way.”

The test subjects were instructed not to eat anything for 3 hours and “then invited back to the lab to perform imagination tasks.” Those who did come back were randomly divided into five different groups, each with a different task:

- Imagine moving their recent lunch at the lab around a plate.

- Recall eating their recent lunch in detail.

- Imagine that the lunch was twice as big and filling as it really was.

- Look at a photograph of spaghetti hoops in tomato sauce and write a description of it before imagining moving the food around a plate.

- Look at a photo of paper clips and rubber bands and imagine moving them around.

Now, at last, we get to the biscuits/cookies, which were the subject of a taste test that “was simply a rouse for covertly assessing snacking,” the investigators explained. As part of that test, participants were told they could eat as many biscuits as they wanted.

When the tables were cleared and the leftovers examined, the group that imagined spaghetti hoops had eaten the most biscuits (75.9 g), followed by the group that imagined paper clips (75.5 g), the moving-their-lunch-around-the-plate group (72.0 g), and the group that relived eating their lunch (70.0 g).

In a victory for the meal-recall effect, the people who imagined their meal being twice as big ate the fewest biscuits (51.1 g). “Your mind can be more powerful than your stomach in dictating how much you eat,” lead author Joanna Szypula, PhD, said in the university statement.

Oh! One more thing. The study appeared in Appetite, which is a peer-reviewed journal, not in Bon Appétit, which is not a peer-reviewed journal. Thanks to the fine folks at both publications for pointing that out to us.

Protuberant, Pink, Irritated Growth on the Buttocks

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

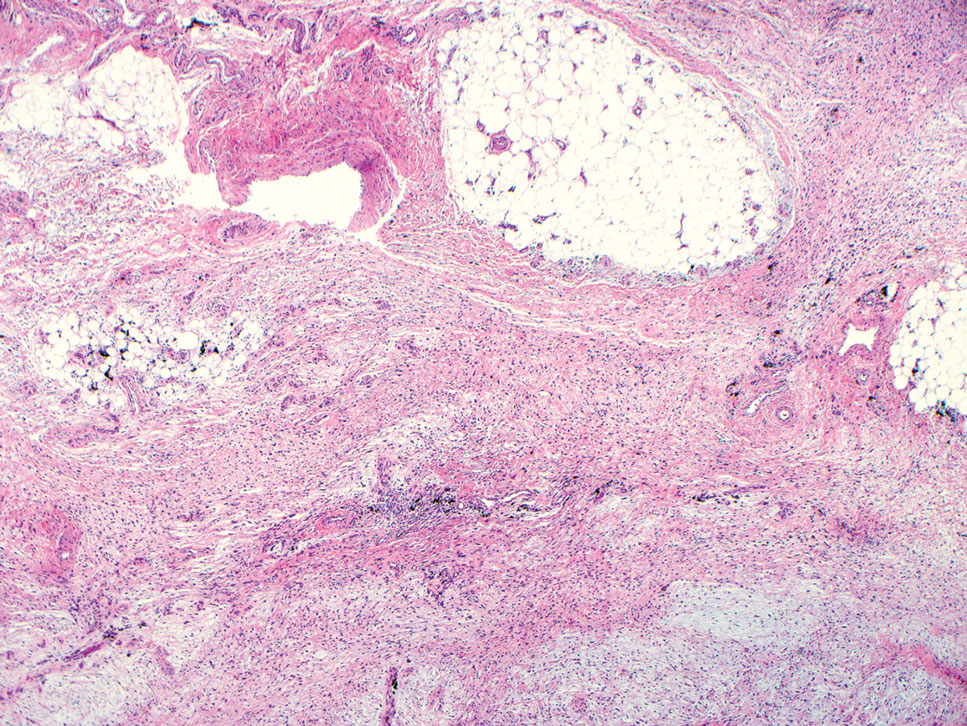

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3

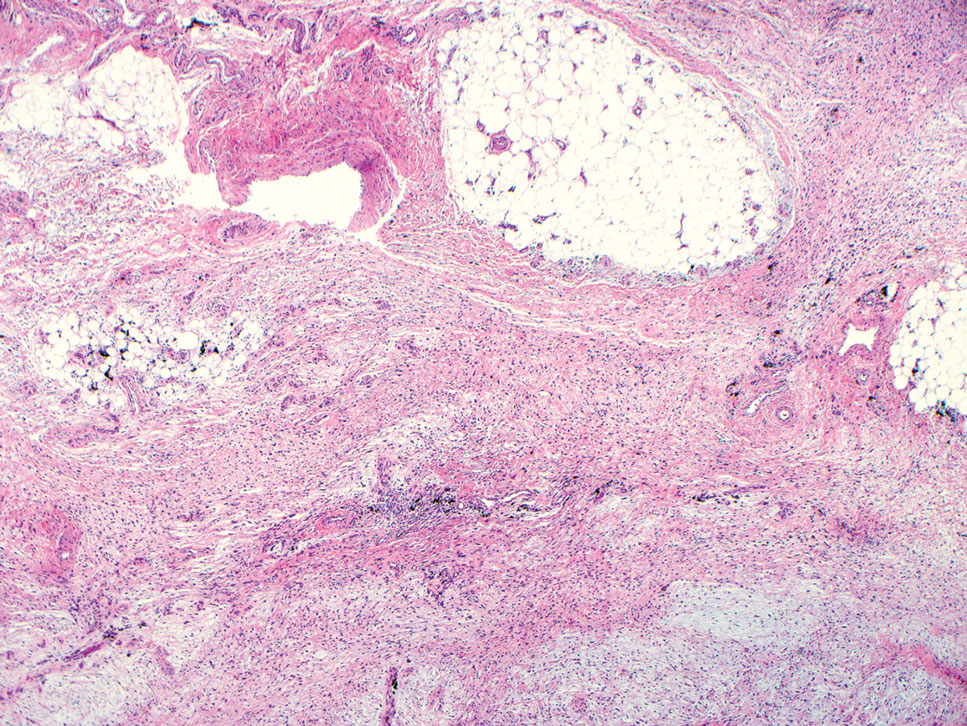

Common histologic mimics of superficial angiomyxoma include aggressive angiomyxoma and angiomyofibroblastoma.4 It is thought that these 3 distinct tumor entities may arise from a common pluripotent cell of origin located near connective tissue vasculature, which may contribute to the similarities observed between them.5 For example, aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas also demonstrate a similar myxoid background and vascular proliferation that can closely mimic superficial angiomyxomas clinically. However, the vessels of superficial angiomyxomas tend to be long and thin walled, while aggressive angiomyxomas are characterized by large and thick-walled vessels and angiomyofibroblastomas by abundant smaller vessels. Additionally, unlike superficial angiomyxomas, both aggressive angiomyxomas and angiomyofibroblastomas typically occur in the genital tract of young to middle-aged women.6

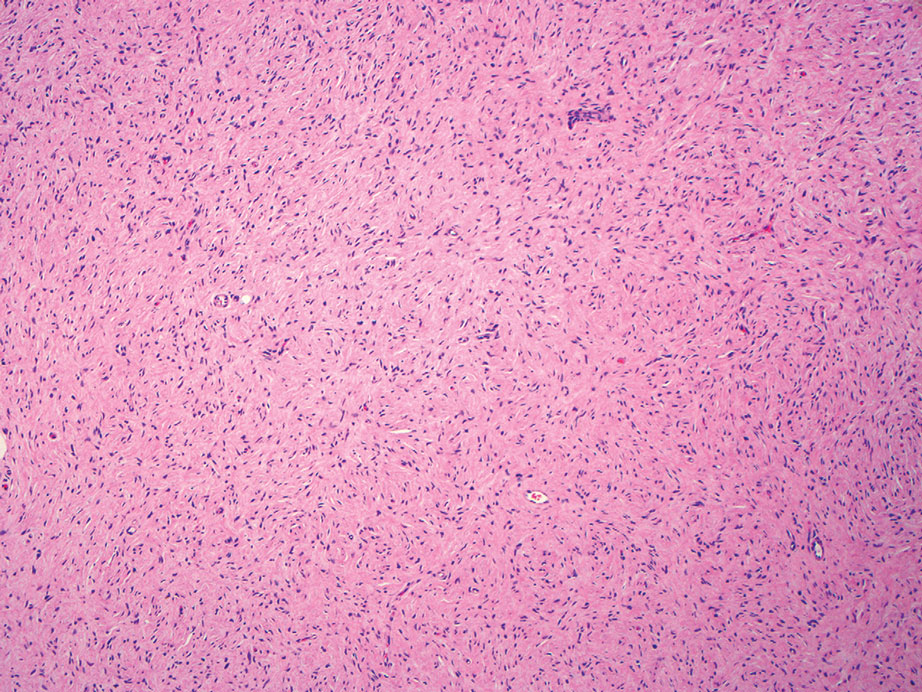

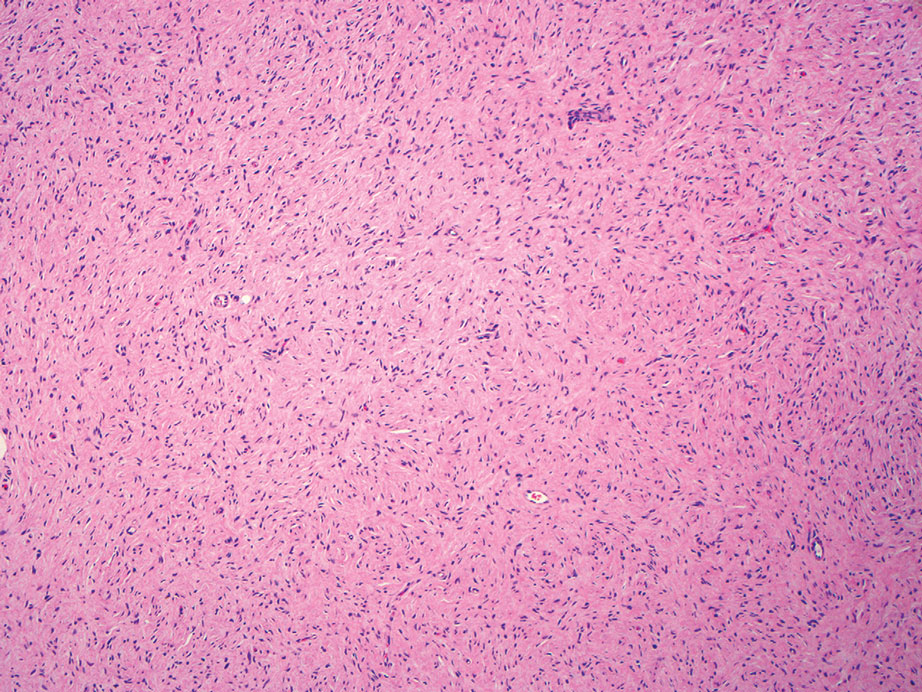

Histopathologic examination is imperative for differentiating between superficial angiomyxoma and more aggressive histologic mimics. Superficial angiomyxomas typically consist of a rich myxoid stroma, thin-walled or arborizing blood vessels, and spindled to stellate fibroblastlike cells (quiz image 2).3 Although not prominent in our case, superficial angiomyxomas also frequently present with stromal neutrophils and epithelial components, including keratinous cysts, basaloid buds, and strands of squamous epithelium.7 Minimal cellular atypia, mitotic activity, and nuclear pleomorphism often are seen, with IHC negative for desmin, estrogen receptor, and progesterone receptor; positive for CD34 and smooth muscle actin; and variable for S-100 and muscle-specific actin. Although IHC has limited utility in the diagnosis of superficial angiomyxomas, it may be useful to rule out other differential diagnoses.2,3 Superficial angiomyxomas usually show fibroblastic stromal cells, proteoglycan matrix, and collagen fibers on electron microscopy.8 Importantly, histopathologic examination of aggressive angiomyxoma will comparatively present with more invasive, infiltrative, and less well-circumscribed tumors.9 Other differential diagnoses on histology may include neurofibroma, focal cutaneous mucinosis, spindle cell lipoma, and myxofibrosarcoma. Additional considerations include fibroepithelial polyp, nevus lipomatosis, angiomyxolipoma, and anetoderma.

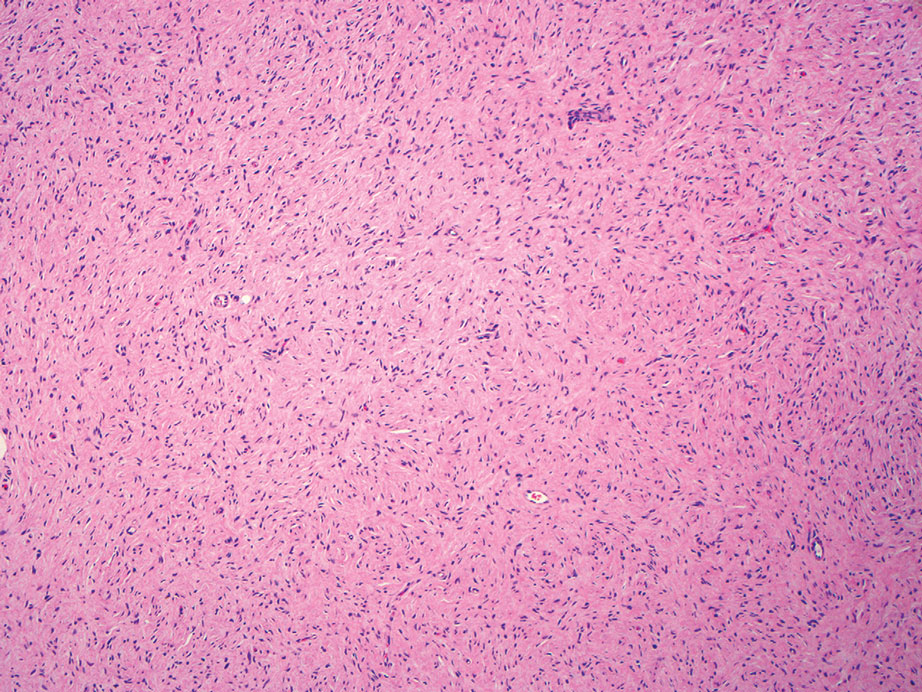

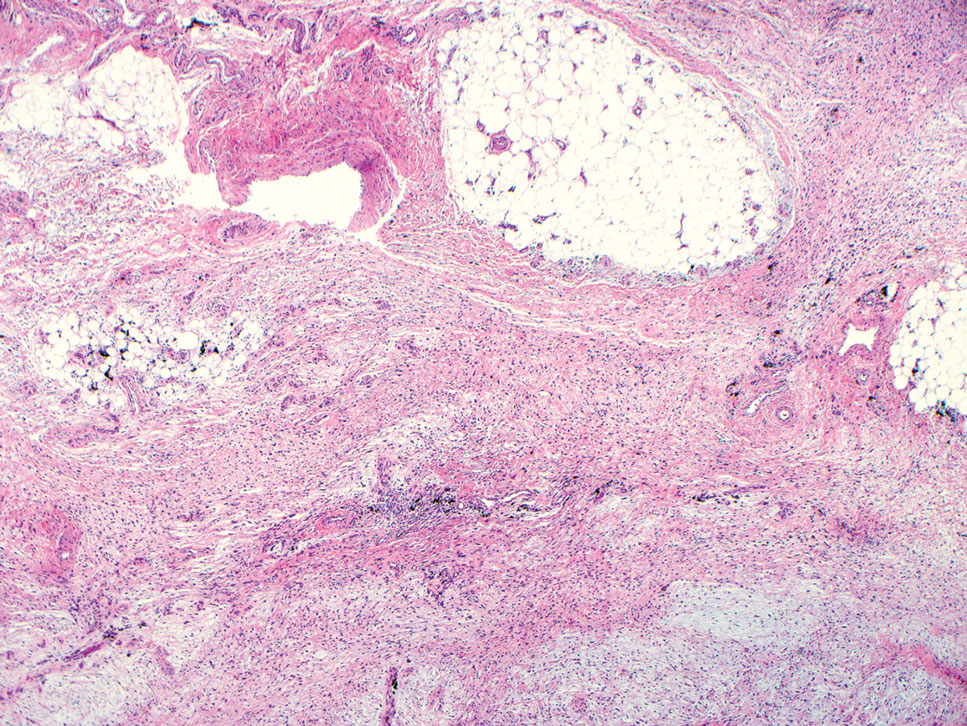

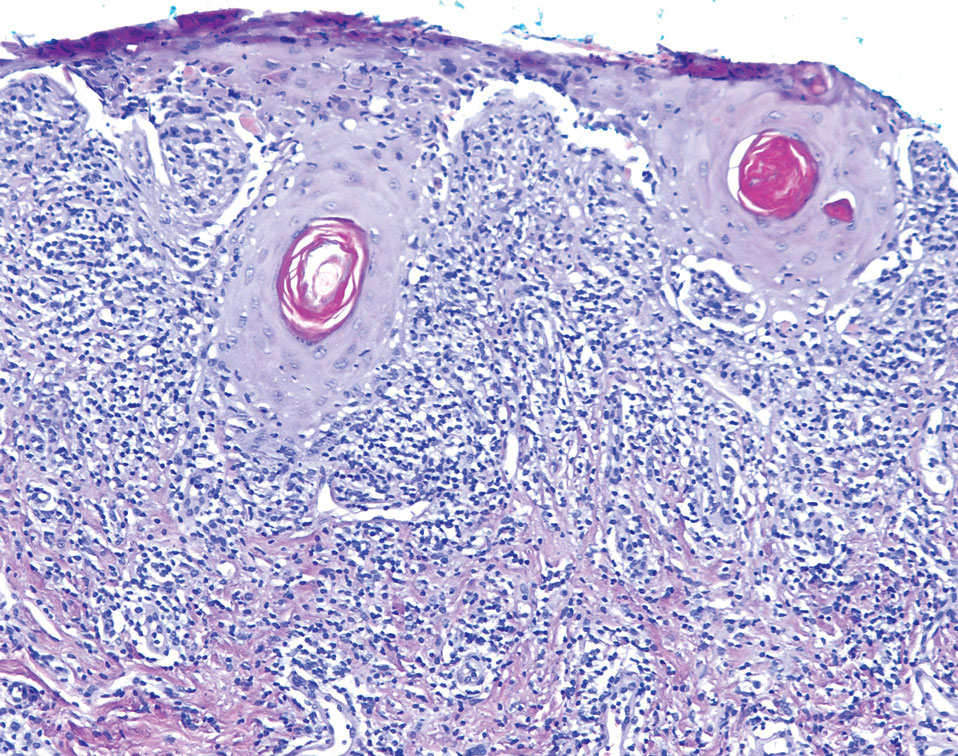

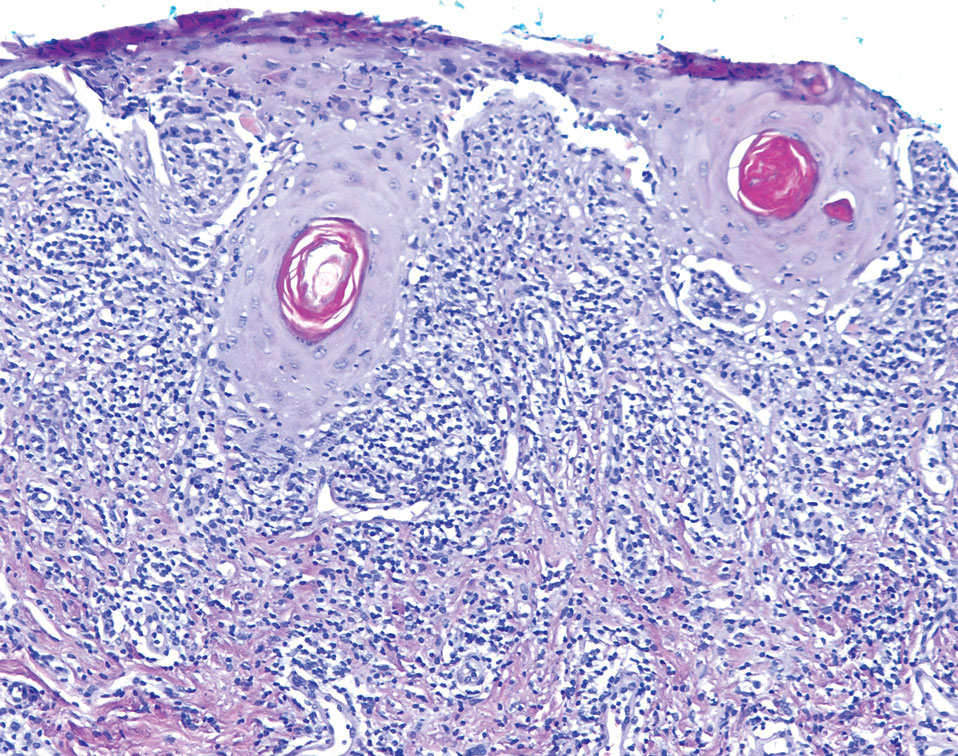

An important differential diagnosis in the evaluation of superficial angiomyxoma is neurofibroma, a benign peripheral nerve sheath tumor that presents as a smooth, flesh-colored, and painless papule or nodule commonly associated with the buttonhole sign. Histopathology of neurofibroma features elongated spindle cells with comma-shaped or buckled wavy nuclei and variably sized collagen bundles described as “shredded carrots” (Figure 1).10 Occasional mast cells also can be seen. Immunohistochemistry targeting elements of peripheral nerve sheaths may assist in the diagnosis of neurofibromas, including positive S-100 and SOX10 in Schwann cells, epithelial membrane antigen in perineural cells, and fingerprint positivity for CD34 in fibroblasts.10

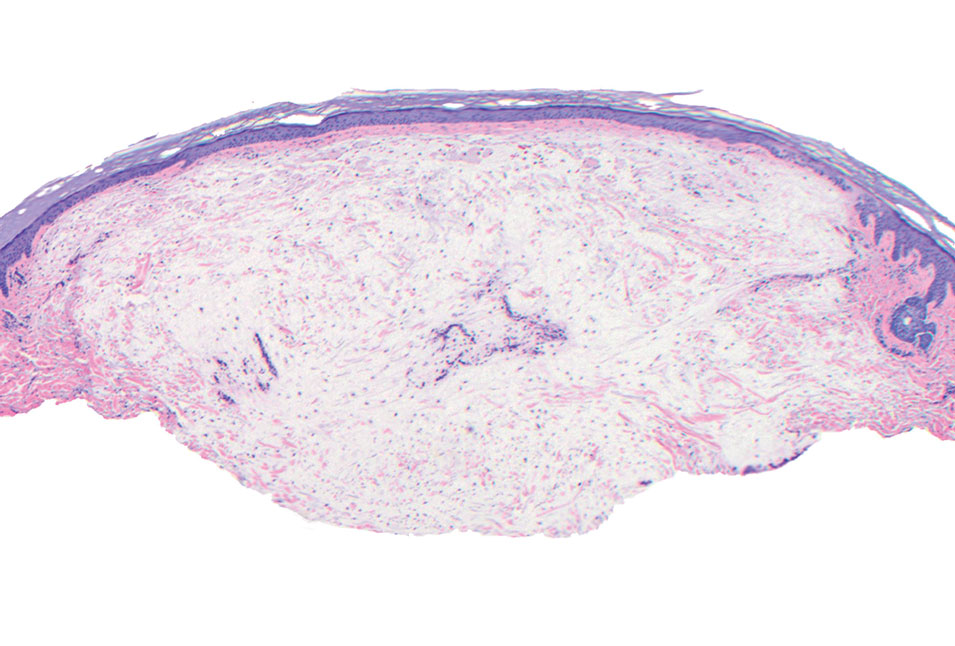

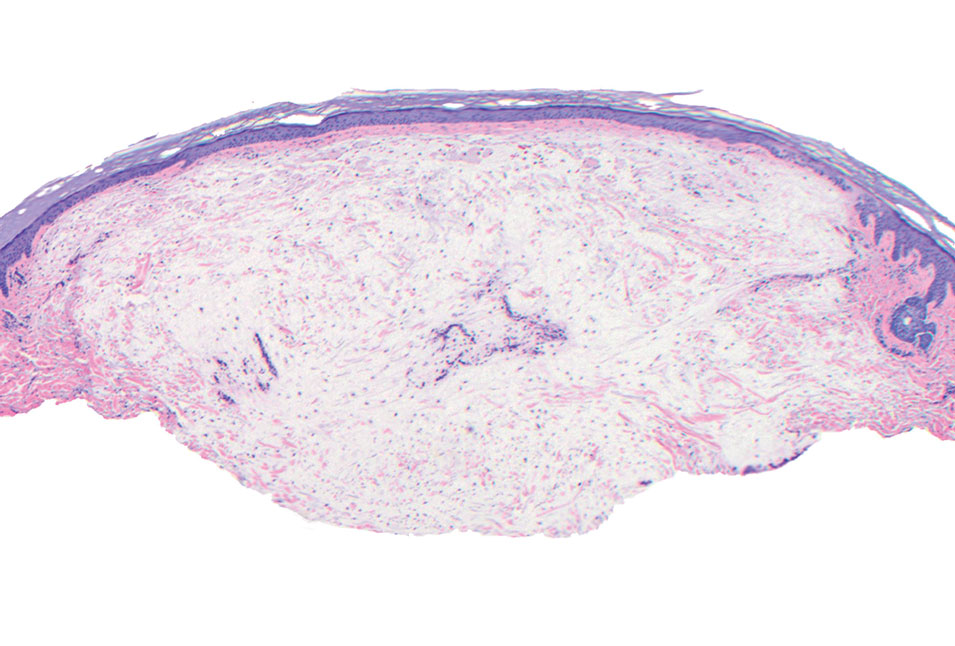

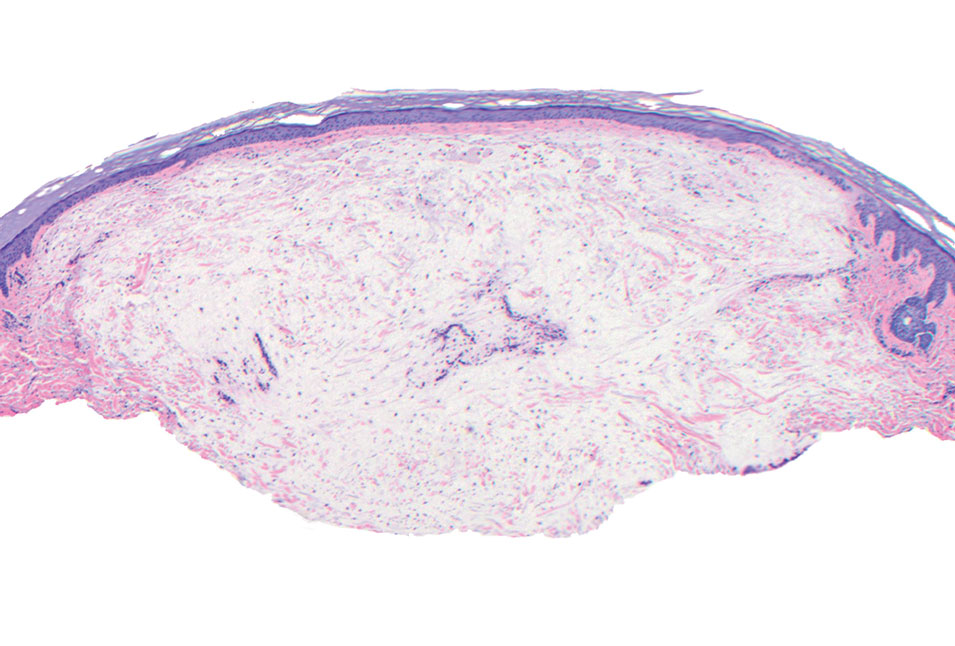

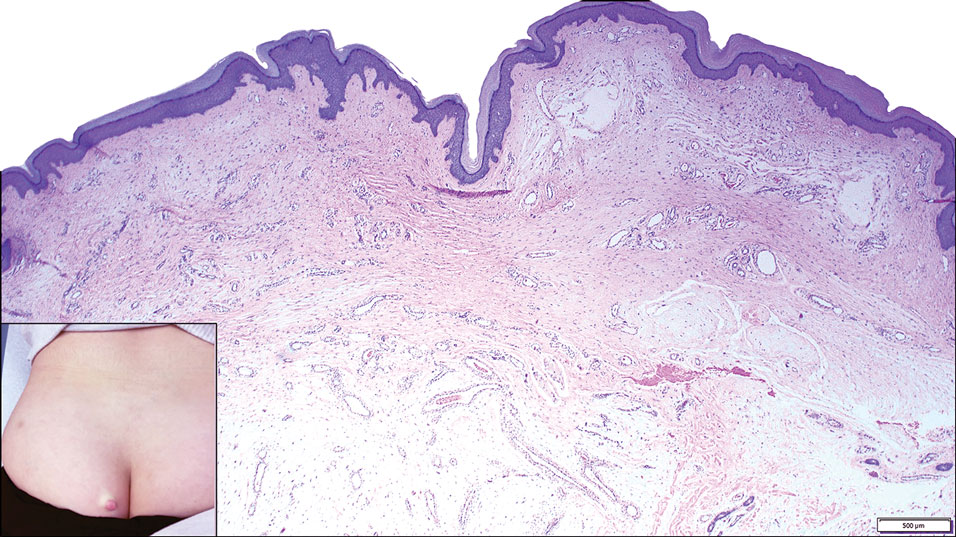

Cutaneous mucinoses encompass a diverse group of connective tissue disorders characterized by accumulation of mucin in the skin. Solitary focal cutaneous mucinoses (FCMs) are individual isolated lesions of mucin deposits that are unassociated with systemic conditions.11 Conversely, multiple FCMs presenting with multiple cutaneous lesions also have been described in association with systemic diseases such as scleroderma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and thyroid disease.12 Solitary FCM typically presents as an asymptomatic, flesh-colored papule or nodule on the extremities. It often arises in mid to late adulthood with a slightly increased frequency among males.12 Histopathology of solitary FCM commonly demonstrates a dome-shaped pool of basophilic mucin in the upper dermis sparing involvement of the underlying subcutaneous tissue (Figure 2).13 Notably, FCM often lacks the vascularity as well as stromal neutrophils and epithelial elements that are seen in superficial angiomyxomas. Although hematoxylin and eosin stains can be sufficient for diagnosis of solitary FCM, additional stains for mucin such as Alcian blue, colloidal iron, or toluidine blue also may be considered to support the diagnosis.12

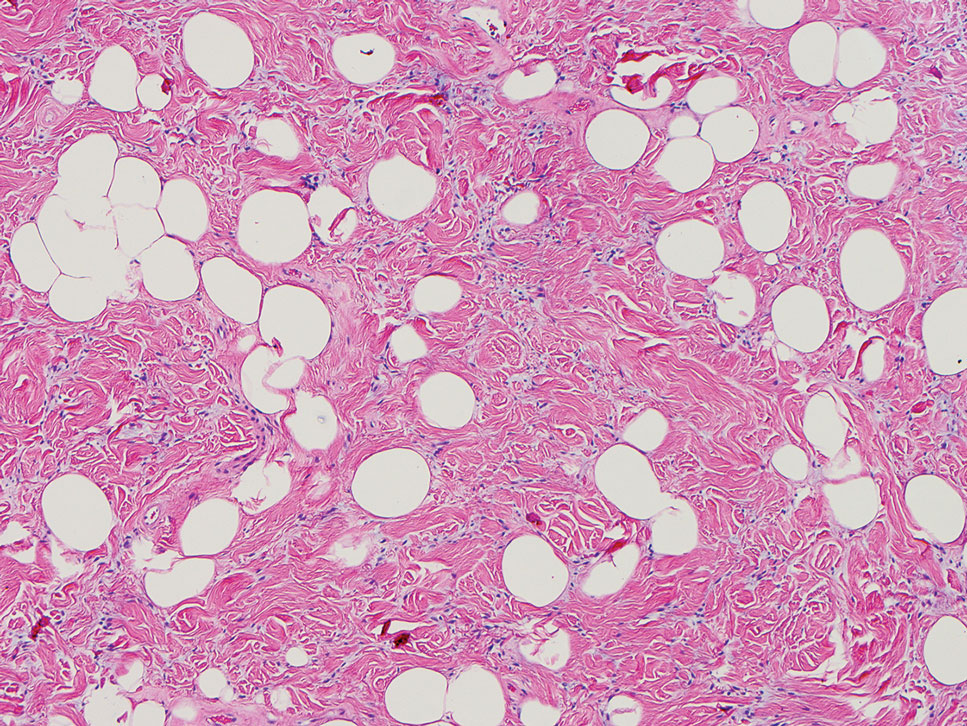

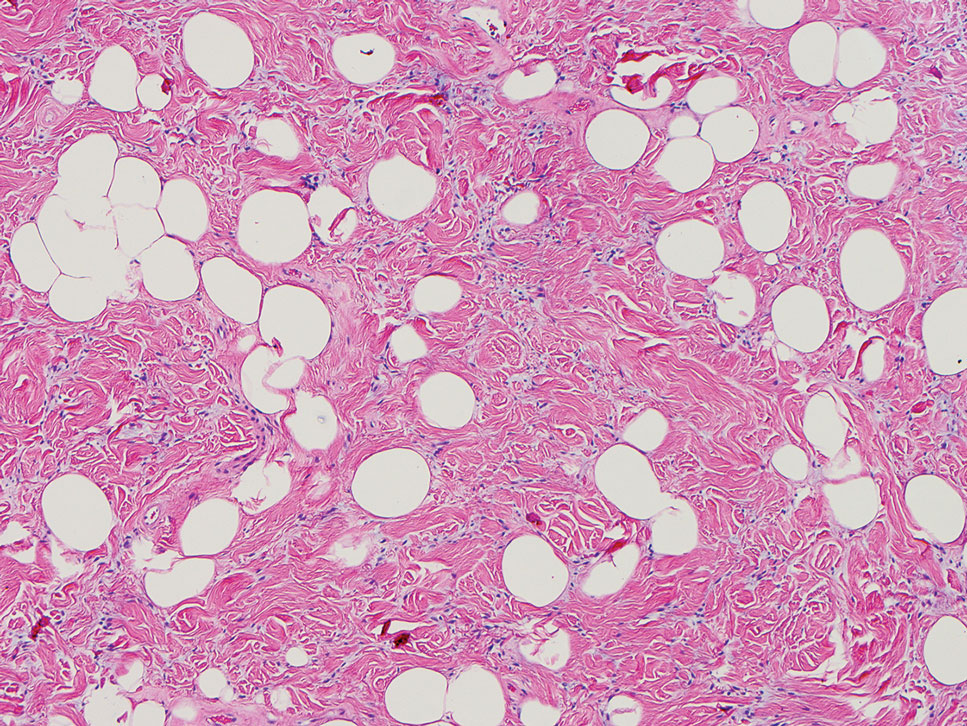

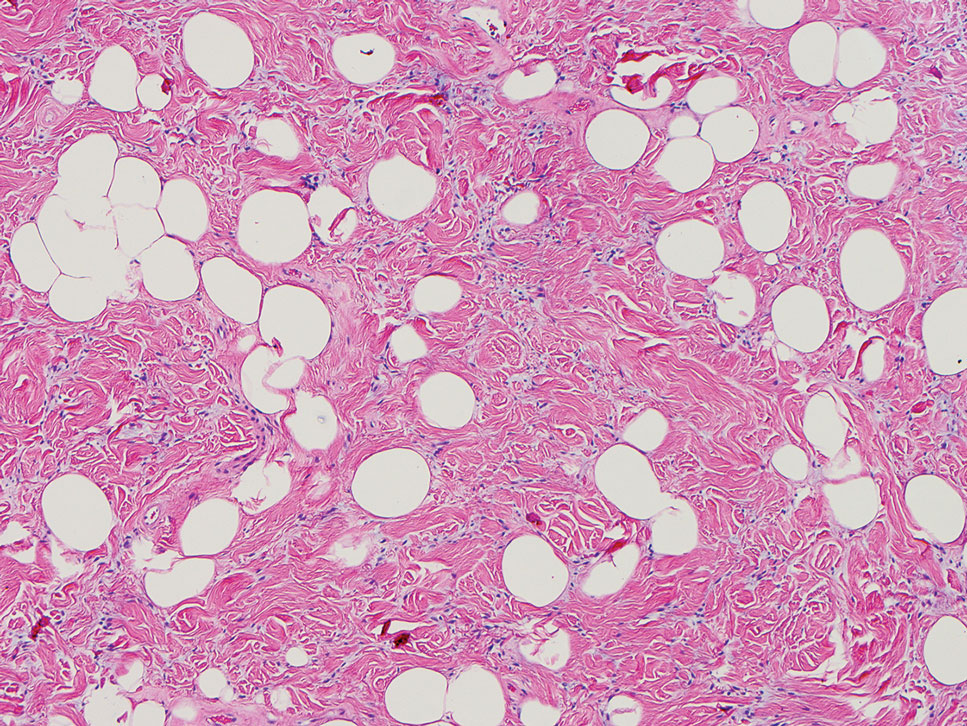

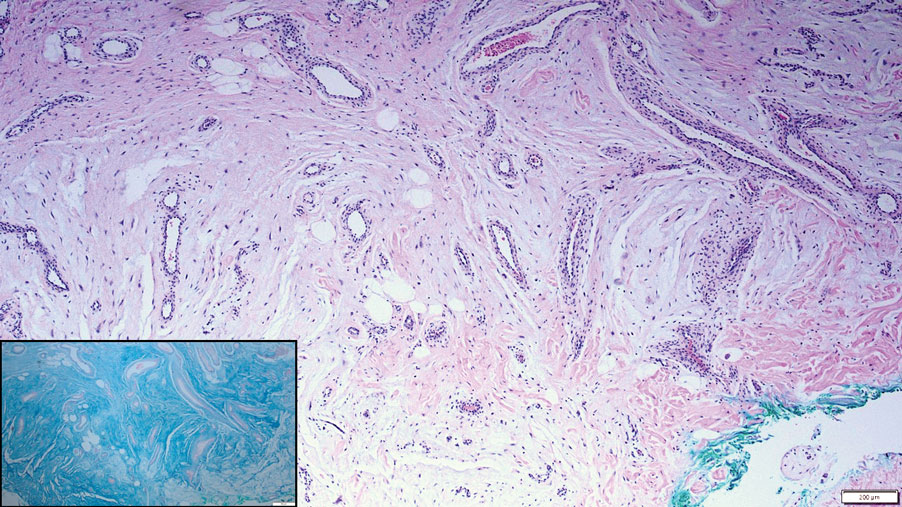

Spindle cell lipomas (SCLs) are rare, benign, subcutaneous, adipocytic tumors that arise on the upper back, posterior neck, or shoulders of middle-aged or elderly adult males.14 The clinical presentation often is an asymptomatic, well-circumscribed, mobile subcutaneous mass that is firmer than a common lipoma. Histologically, SCLs are characterized by mature adipocytes, spindle cells, and wire or ropelike collagen fibers in a myxoid background (Figure 3). The spindle cells usually are bland with a notable bipolar shape and blunted ends. Infiltrative growth patterns or mitotic figures are uncommon. Diagnosis can be supported by IHC, as SCLs stain diffusely positive for CD34 with loss of the retinoblastoma protein.7

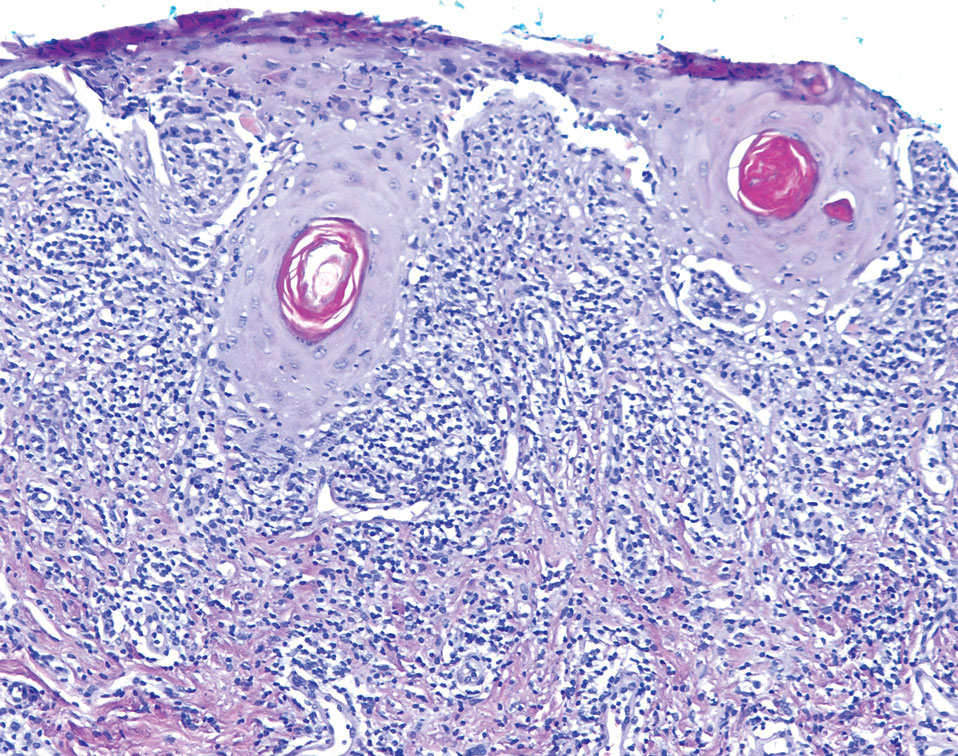

Another important differential diagnosis to consider is myxofibrosarcoma, a rare and malignant myxoid cutaneous tumor. Clinically, it presents asymptomatically as an indolent, slow-growing nodule on the limbs and limb girdles.7 Histopathologic features demonstrate a multilobular tumor composed of a mixture of hypocellular and hypercellular regions with incomplete fibrous septae (Figure 4). The presence of curvilinear vasculature is characteristic. Multinucleated giant cells and cellular atypia with nuclear pleomorphism also can be seen. Although IHC findings generally are not specific, they can be used to rule out other potential diagnoses. Myxofibrosarcomas stain positive for vimentin and occasionally smooth muscle actin, muscle-specific actin, and CD34.7

Superficial angiomyxomas are benign; however, excision is recommended to distinguish between mimics. Local recurrence after excision is common in 30% to 40% of patients.15 Mohs micrographic surgery has been considered, especially if the following are present: tumor characteristics (eg, poorly circumscribed), location (eg, head and neck or other cosmetically or functionally sensitive areas), and likelihood of recurrence (high for superficial angiomyxomas). 16 This case otherwise highlights a rare example of superficial angiomyxomas involving the buttocks.

- Allen PW, Dymock RB, MacCormac LB. Superficial angiomyxomas with and without epithelial components. report of 30 tumors in 28 patients. Am J Surg Pathol. 1988;12:519-530. doi:10.1097 /00000478-198807000-00003

- Sharma A, Khaitan N, Ko JS, et al. A clinicopathologic analysis of 54 cases of cutaneous myxoma. Hum Pathol. 2021:S0046-8177(21) 00201-X. doi:10.1016/j.humpath.2021.12.003

- Hafeez F, Krakowski AC, Lian CG, et al. Sporadic superficial angiomyxomas demonstrate loss of PRKAR1A expression [published online March 17, 2022]. Histopathology. 2022;80:1001-1003. doi:10.1111/his.14568

- Mehrotra K, Bhandari M, Khullar G, et al. Large superficial angiomyxoma of the vulva: report of two cases with varied clinical presentation. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2021;12:605-607. doi:10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_489_20

- Alameda F, Munné A, Baró T, et al. Vulvar angiomyxoma, aggressive angiomyxoma, and angiomyofibroblastoma: an immunohistochemical and ultrastructural study. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2006;30:193-205. doi:10.1080/01913120500520911

- Haroon S, Irshad L, Zia S, et al. Aggressive angiomyxoma, angiomyofibroblastoma, and cellular angiofibroma of the lower female genital tract: related entities with different outcomes. Cureus. 2022;14:E29250. doi:10.7759/cureus.29250

- Zou Y, Billings SD. Myxoid cutaneous tumors: a review. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:903-918. doi:10.1111/cup.12749

- Allen PW. Myxoma is not a single entity: a review of the concept of myxoma. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2000;4:99-123. doi:10.1016 /s1092-9134(00)90019-4

- Lee C-C, Chen Y-L, Liau J-Y, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma on the vulva of an adolescent. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2014;53:104-106. doi:10.1016/j.tjog.2013.08.001

- Magro G, Amico P, Vecchio GM, et al. Multinucleated floret-like giant cells in sporadic and NF1-associated neurofibromas: a clinicopathologic study of 94 cases. Virchows Arch. 2010;456:71-76. doi:10.1007/s00428-009-0859-y

- Kuo KL, Lee LY, Kuo TT. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis: a clinicopathological study of 11 cases of soft fibroma-like cutaneous mucinous lesions. J Dermatol. 2017;44:335-338. doi:10.1111/1346-8138.13523

- Gutierrez N, Erickson C, Calame A, et al. Solitary cutaneous focal mucinosis. Cureus. 2021;13:E18618. doi:10.7759/cureus.18618

- Biondo G, Sola S, Pastorino C, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic, and histologic aspects of two cases of cutaneous focal mucinosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2019;94:334-336. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20198381

- Chen S, Huang H, He S, et al. Spindle cell lipoma: clinicopathologic characterization of 40 cases. Int J Clin Exp Pathol. 2019;12:2613-2621.

- Bembem K, Jaiswal A, Singh M, et al. Cyto-histo correlation of a very rare tumor: superficial angiomyxoma. J Cytol. 2017;34:230-232. doi:10.4103/0970-9371.216119

- Aberdein G, Veitch D, Perrett C. Mohs micrographic surgery for the treatment of superficial angiomyxoma. Dermatol Surg. 2016;42: 1014-1016. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000000782

The Diagnosis: Superficial Angiomyxoma

Superficial angiomyxoma is a rare, benign, cutaneous tumor of a myxoid matrix and blood vessels that was first described in association with Carney complex.1 Tumors may be solitary or multiple. A recent review of cases in the literature revealed a roughly equal distribution of superficial angiomyxomas in males and females occurring most frequently on the head and neck, extremities, and trunk or back. The peak incidence is between the fourth and fifth decades of life.2 Superficial angiomyxomas can occur sporadically or in association with Carney complex, an autosomal-dominant condition with germline inactivating mutations in protein kinase A, PRKAR1A. Interestingly, sporadic cases of superficial angiomyxoma also have shown loss of PRKAR1A expression on immunohistochemistry (IHC).3