User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

NCCN panel: Defer nonurgent skin cancer care during pandemic

Amid the except when metastatic nodes are threatening vital structures or neoadjuvant therapy is not possible or has already failed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network said in a new document about managing melanoma during the pandemic.

“The NCCN Melanoma Panel does not consider neoadjuvant therapy as a superior option to surgery followed by systemic adjuvant therapy for stage III melanoma, but available data suggest this is a reasonable resource-conserving option during the COVID-19 outbreak,” according to the panel. Surgery should be performed 8-9 weeks after initiation, said the group, an alliance of physicians from 30 U.S. cancer centers.

Echoing pandemic advice from other medical fields, the group’s melanoma recommendations focused on deferring nonurgent care until after the pandemic passes, and in the meantime limiting patient contact with the medical system and preserving hospital resources by, for instance, using telemedicine and opting for treatment regimens that require fewer trips to the clinic.

In a separate document on nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the group said that, with the exception of Merkel cell carcinoma, excisions for NMSC – including basal and squamous cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and rare tumors – should also generally be postponed during the pandemic.

The exception is if there is a risk of metastases within 3 months, but “such estimations of risks ... should be weighed against risks of the patient contracting COVID-19 infection or asymptomatically transmitting COVID-19 to health care workers,” the panel said.

Along the same lines, adjuvant therapy after surgical clearance of localized NMSC “should generally not be undertaken given the multiple visits required,” except for more extensive disease.

For primary cutaneous melanoma , “most time-to-treat studies show no adverse patient outcomes following a 90-day treatment delay, even for thicker [cutaneous melanoma],” the group said, so it recommended delaying wide excisions for melanoma in situ, lesions no thicker than 1 mm (T1) so long as the biopsy removed most of the lesion, and invasive melanomas of any depth if the biopsy had clear margins or only peripheral transection of the in situ component. They said sentinel lymph node biopsy can also be delayed for up to 3 months.

Resections for metastatic stage III-IV disease should also be put on hold unless the patient is symptomatic; systemic treatments should instead be continued. However, “given hospital-intensive resources, the use of talimogene laherparepvec for cutaneous/nodal/in-transit metastasis should be cautiously considered and, if possible, deferred until the COVID-19 crisis abates. A single dose of palliative radiation therapy may be useful for larger/symptomatic metastasis, as appropriate,” the group said.

If resection is still a go, the group noted that adjuvant therapy “has not been shown to improve melanoma-specific survival and should be deferred during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with [a less than] 50% chance of disease relapse.” Dabrafenib/trametinib is the evidence-based choice if adjuvant treatment is opted for, but “alternative BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimens (encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib) may be substituted if drug supply is limited” by the pandemic, the group said.

For stage IV melanoma, “single-agent anti-PD-1 [programmed cell death 1] is recommended over combination ipilimumab/nivolumab at present” because there’s less inflammation and possible exacerbation of COVID-19, less need for steroids to counter adverse events, and less need for follow up to check for toxicities.

The group said evidence supports that 400 mg pembrolizumab administered intravenously every 6 weeks would likely be as effective as 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks and would help keep people out of the hospital.

However, for stage IV melanoma with brain metastasis, there’s a strong rate of response to ipilimumab/nivolumab, so it may still be an option. In that case, “a regimen of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four infusions, with subsequent consideration for nivolumab monotherapy, is associated with lower rates of immune-mediated toxicity,” compared with standard dosing.

Regarding potential drug shortages, the group noted that encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib combinations can be substituted for dabrafenib/trametinib for adjuvant therapy, and single-agent BRAF inhibitors can be used in the event of MEK inhibitor shortages.

In hospice, the group said oral temozolomide is the preferred option for palliative chemotherapy since it would limit resource utilization and contact with the medical system.

Amid the except when metastatic nodes are threatening vital structures or neoadjuvant therapy is not possible or has already failed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network said in a new document about managing melanoma during the pandemic.

“The NCCN Melanoma Panel does not consider neoadjuvant therapy as a superior option to surgery followed by systemic adjuvant therapy for stage III melanoma, but available data suggest this is a reasonable resource-conserving option during the COVID-19 outbreak,” according to the panel. Surgery should be performed 8-9 weeks after initiation, said the group, an alliance of physicians from 30 U.S. cancer centers.

Echoing pandemic advice from other medical fields, the group’s melanoma recommendations focused on deferring nonurgent care until after the pandemic passes, and in the meantime limiting patient contact with the medical system and preserving hospital resources by, for instance, using telemedicine and opting for treatment regimens that require fewer trips to the clinic.

In a separate document on nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the group said that, with the exception of Merkel cell carcinoma, excisions for NMSC – including basal and squamous cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and rare tumors – should also generally be postponed during the pandemic.

The exception is if there is a risk of metastases within 3 months, but “such estimations of risks ... should be weighed against risks of the patient contracting COVID-19 infection or asymptomatically transmitting COVID-19 to health care workers,” the panel said.

Along the same lines, adjuvant therapy after surgical clearance of localized NMSC “should generally not be undertaken given the multiple visits required,” except for more extensive disease.

For primary cutaneous melanoma , “most time-to-treat studies show no adverse patient outcomes following a 90-day treatment delay, even for thicker [cutaneous melanoma],” the group said, so it recommended delaying wide excisions for melanoma in situ, lesions no thicker than 1 mm (T1) so long as the biopsy removed most of the lesion, and invasive melanomas of any depth if the biopsy had clear margins or only peripheral transection of the in situ component. They said sentinel lymph node biopsy can also be delayed for up to 3 months.

Resections for metastatic stage III-IV disease should also be put on hold unless the patient is symptomatic; systemic treatments should instead be continued. However, “given hospital-intensive resources, the use of talimogene laherparepvec for cutaneous/nodal/in-transit metastasis should be cautiously considered and, if possible, deferred until the COVID-19 crisis abates. A single dose of palliative radiation therapy may be useful for larger/symptomatic metastasis, as appropriate,” the group said.

If resection is still a go, the group noted that adjuvant therapy “has not been shown to improve melanoma-specific survival and should be deferred during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with [a less than] 50% chance of disease relapse.” Dabrafenib/trametinib is the evidence-based choice if adjuvant treatment is opted for, but “alternative BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimens (encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib) may be substituted if drug supply is limited” by the pandemic, the group said.

For stage IV melanoma, “single-agent anti-PD-1 [programmed cell death 1] is recommended over combination ipilimumab/nivolumab at present” because there’s less inflammation and possible exacerbation of COVID-19, less need for steroids to counter adverse events, and less need for follow up to check for toxicities.

The group said evidence supports that 400 mg pembrolizumab administered intravenously every 6 weeks would likely be as effective as 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks and would help keep people out of the hospital.

However, for stage IV melanoma with brain metastasis, there’s a strong rate of response to ipilimumab/nivolumab, so it may still be an option. In that case, “a regimen of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four infusions, with subsequent consideration for nivolumab monotherapy, is associated with lower rates of immune-mediated toxicity,” compared with standard dosing.

Regarding potential drug shortages, the group noted that encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib combinations can be substituted for dabrafenib/trametinib for adjuvant therapy, and single-agent BRAF inhibitors can be used in the event of MEK inhibitor shortages.

In hospice, the group said oral temozolomide is the preferred option for palliative chemotherapy since it would limit resource utilization and contact with the medical system.

Amid the except when metastatic nodes are threatening vital structures or neoadjuvant therapy is not possible or has already failed, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network said in a new document about managing melanoma during the pandemic.

“The NCCN Melanoma Panel does not consider neoadjuvant therapy as a superior option to surgery followed by systemic adjuvant therapy for stage III melanoma, but available data suggest this is a reasonable resource-conserving option during the COVID-19 outbreak,” according to the panel. Surgery should be performed 8-9 weeks after initiation, said the group, an alliance of physicians from 30 U.S. cancer centers.

Echoing pandemic advice from other medical fields, the group’s melanoma recommendations focused on deferring nonurgent care until after the pandemic passes, and in the meantime limiting patient contact with the medical system and preserving hospital resources by, for instance, using telemedicine and opting for treatment regimens that require fewer trips to the clinic.

In a separate document on nonmelanoma skin cancer (NMSC), the group said that, with the exception of Merkel cell carcinoma, excisions for NMSC – including basal and squamous cell carcinoma, dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, and rare tumors – should also generally be postponed during the pandemic.

The exception is if there is a risk of metastases within 3 months, but “such estimations of risks ... should be weighed against risks of the patient contracting COVID-19 infection or asymptomatically transmitting COVID-19 to health care workers,” the panel said.

Along the same lines, adjuvant therapy after surgical clearance of localized NMSC “should generally not be undertaken given the multiple visits required,” except for more extensive disease.

For primary cutaneous melanoma , “most time-to-treat studies show no adverse patient outcomes following a 90-day treatment delay, even for thicker [cutaneous melanoma],” the group said, so it recommended delaying wide excisions for melanoma in situ, lesions no thicker than 1 mm (T1) so long as the biopsy removed most of the lesion, and invasive melanomas of any depth if the biopsy had clear margins or only peripheral transection of the in situ component. They said sentinel lymph node biopsy can also be delayed for up to 3 months.

Resections for metastatic stage III-IV disease should also be put on hold unless the patient is symptomatic; systemic treatments should instead be continued. However, “given hospital-intensive resources, the use of talimogene laherparepvec for cutaneous/nodal/in-transit metastasis should be cautiously considered and, if possible, deferred until the COVID-19 crisis abates. A single dose of palliative radiation therapy may be useful for larger/symptomatic metastasis, as appropriate,” the group said.

If resection is still a go, the group noted that adjuvant therapy “has not been shown to improve melanoma-specific survival and should be deferred during the COVID-19 pandemic for patients with [a less than] 50% chance of disease relapse.” Dabrafenib/trametinib is the evidence-based choice if adjuvant treatment is opted for, but “alternative BRAF/MEK inhibitor regimens (encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib) may be substituted if drug supply is limited” by the pandemic, the group said.

For stage IV melanoma, “single-agent anti-PD-1 [programmed cell death 1] is recommended over combination ipilimumab/nivolumab at present” because there’s less inflammation and possible exacerbation of COVID-19, less need for steroids to counter adverse events, and less need for follow up to check for toxicities.

The group said evidence supports that 400 mg pembrolizumab administered intravenously every 6 weeks would likely be as effective as 200 mg intravenously every 3 weeks and would help keep people out of the hospital.

However, for stage IV melanoma with brain metastasis, there’s a strong rate of response to ipilimumab/nivolumab, so it may still be an option. In that case, “a regimen of ipilimumab 1 mg/kg and nivolumab 3 mg/kg every 3 weeks for four infusions, with subsequent consideration for nivolumab monotherapy, is associated with lower rates of immune-mediated toxicity,” compared with standard dosing.

Regarding potential drug shortages, the group noted that encorafenib/binimetinib or vemurafenib/cobimetinib combinations can be substituted for dabrafenib/trametinib for adjuvant therapy, and single-agent BRAF inhibitors can be used in the event of MEK inhibitor shortages.

In hospice, the group said oral temozolomide is the preferred option for palliative chemotherapy since it would limit resource utilization and contact with the medical system.

Nearly 24 tests for the novel coronavirus are available

according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

“Based on what we know about influenza, it’s unlikely that all of these tests are going to perform exactly the same way,” said Angela M. Caliendo, MD, executive vice chair of the department of medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., at a press briefing. Although these tests are good, no test is perfect, she added.

The development and availability of testing has improved over time, but clinical laboratories still face challenges, said Kimberly E. Hanson, MD, associate professor of internal medicine at University of Utah, Salt Lake City. These challenges include shortages of devices for specimen collection, media, test tubes, and reagents. Although the goal is to test all symptomatic patients, these shortages require laboratories to prioritize health care workers and the sickest patients.

Tests are being approved through an abbreviated process

Two types of test, rapid tests and serology tests, are in use. Rapid tests use polymerase chain reactions to detect the virus in a clinical specimen. This type of testing is used to diagnose infection. Serology tests measure antibodies to the virus and are more appropriate for indicating whether a patient has been exposed to the virus.

The declaration of a national emergency enabled the FDA to activate its EUA policy, which allows for quicker approval of tests. Normally, a test must be assessed in the laboratory (such as with a mock specimen or an inactivated virus) and in a clinical study of patients. Under the EUA, clinical assessment is not required for the approval of a test. Consequently, the clinical performance of a test approved under EUA is unknown.

Collecting a specimen of good quality is critical to the quality of the test result, said Dr. Caliendo, the secretary of IDSA’s board of directors. Clinicians and investigators have used nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, and specimens collected from deep within the lung. “We’re still collecting data to determine which is the best specimen type.” As coronavirus testing expands, particularly to drive-through testing sites, “we may be using people who are not as experienced, and so you might not get as high a quality specimen in that situation,” Dr. Caliendo added.

The timing of the test influences the quality of the result, as well, because the amount of virus is lower at the onset of symptoms than it is later. Another factor that affects the quality of the results is the test’s sensitivity.

The time to obtain results varies

The value of having several tests available is that it enables many patients to be tested simultaneously, said Dr. Hanson, a member of IDSA’s board of directors. It also helps to reduce potential problems with the supply of test kits. A test manufacturer, however, may supply parts of the test kit but not the whole kit. This requires the hospital or laboratory to obtain the remaining parts from other suppliers. Furthermore, test manufacturers may need to prioritize areas with high rates of infection or transmission when they ship their tests, which limits testing in other areas.

One reason for the lack of a national plan for testing is that the virus has affected different regions at different times, said Dr. Caliendo. Some tests are more difficult to perform than others, and not all laboratories are equally sophisticated, which can limit testing. It is necessary to test not only symptomatic patients who have been hospitalized, but also symptomatic patients in the community, said Dr. Caliendo. “Ideally, we’re going to need to couple acute diagnostics [testing while people are sick] with serologic testing. Serologic testing is going to be important for us to see who has been infected. That will give us an idea of who is left in our community who is at risk for developing infection.”

How quickly test results are available depends on the type of test and where it is administered. Recently established drive-through clinics can provide results in about 30 minutes. Tests performed in hospitals may take between 1 and 6 hours to yield results. “The issue is, do we have reagents that day?” said Dr. Caliendo. “We have to be careful whom we choose to test, and we screen that in the hospital so that we have enough tests to run as we need them.” But many locations have backlogs. “When you have a backlog of testing, you’re going to wait days, unfortunately, to get a result,” said Dr. Caliendo.

Dr. Caliendo and Dr. Hanson did not report disclosures for this briefing.

according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

“Based on what we know about influenza, it’s unlikely that all of these tests are going to perform exactly the same way,” said Angela M. Caliendo, MD, executive vice chair of the department of medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., at a press briefing. Although these tests are good, no test is perfect, she added.

The development and availability of testing has improved over time, but clinical laboratories still face challenges, said Kimberly E. Hanson, MD, associate professor of internal medicine at University of Utah, Salt Lake City. These challenges include shortages of devices for specimen collection, media, test tubes, and reagents. Although the goal is to test all symptomatic patients, these shortages require laboratories to prioritize health care workers and the sickest patients.

Tests are being approved through an abbreviated process

Two types of test, rapid tests and serology tests, are in use. Rapid tests use polymerase chain reactions to detect the virus in a clinical specimen. This type of testing is used to diagnose infection. Serology tests measure antibodies to the virus and are more appropriate for indicating whether a patient has been exposed to the virus.

The declaration of a national emergency enabled the FDA to activate its EUA policy, which allows for quicker approval of tests. Normally, a test must be assessed in the laboratory (such as with a mock specimen or an inactivated virus) and in a clinical study of patients. Under the EUA, clinical assessment is not required for the approval of a test. Consequently, the clinical performance of a test approved under EUA is unknown.

Collecting a specimen of good quality is critical to the quality of the test result, said Dr. Caliendo, the secretary of IDSA’s board of directors. Clinicians and investigators have used nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, and specimens collected from deep within the lung. “We’re still collecting data to determine which is the best specimen type.” As coronavirus testing expands, particularly to drive-through testing sites, “we may be using people who are not as experienced, and so you might not get as high a quality specimen in that situation,” Dr. Caliendo added.

The timing of the test influences the quality of the result, as well, because the amount of virus is lower at the onset of symptoms than it is later. Another factor that affects the quality of the results is the test’s sensitivity.

The time to obtain results varies

The value of having several tests available is that it enables many patients to be tested simultaneously, said Dr. Hanson, a member of IDSA’s board of directors. It also helps to reduce potential problems with the supply of test kits. A test manufacturer, however, may supply parts of the test kit but not the whole kit. This requires the hospital or laboratory to obtain the remaining parts from other suppliers. Furthermore, test manufacturers may need to prioritize areas with high rates of infection or transmission when they ship their tests, which limits testing in other areas.

One reason for the lack of a national plan for testing is that the virus has affected different regions at different times, said Dr. Caliendo. Some tests are more difficult to perform than others, and not all laboratories are equally sophisticated, which can limit testing. It is necessary to test not only symptomatic patients who have been hospitalized, but also symptomatic patients in the community, said Dr. Caliendo. “Ideally, we’re going to need to couple acute diagnostics [testing while people are sick] with serologic testing. Serologic testing is going to be important for us to see who has been infected. That will give us an idea of who is left in our community who is at risk for developing infection.”

How quickly test results are available depends on the type of test and where it is administered. Recently established drive-through clinics can provide results in about 30 minutes. Tests performed in hospitals may take between 1 and 6 hours to yield results. “The issue is, do we have reagents that day?” said Dr. Caliendo. “We have to be careful whom we choose to test, and we screen that in the hospital so that we have enough tests to run as we need them.” But many locations have backlogs. “When you have a backlog of testing, you’re going to wait days, unfortunately, to get a result,” said Dr. Caliendo.

Dr. Caliendo and Dr. Hanson did not report disclosures for this briefing.

according to the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA).

“Based on what we know about influenza, it’s unlikely that all of these tests are going to perform exactly the same way,” said Angela M. Caliendo, MD, executive vice chair of the department of medicine at Brown University in Providence, R.I., at a press briefing. Although these tests are good, no test is perfect, she added.

The development and availability of testing has improved over time, but clinical laboratories still face challenges, said Kimberly E. Hanson, MD, associate professor of internal medicine at University of Utah, Salt Lake City. These challenges include shortages of devices for specimen collection, media, test tubes, and reagents. Although the goal is to test all symptomatic patients, these shortages require laboratories to prioritize health care workers and the sickest patients.

Tests are being approved through an abbreviated process

Two types of test, rapid tests and serology tests, are in use. Rapid tests use polymerase chain reactions to detect the virus in a clinical specimen. This type of testing is used to diagnose infection. Serology tests measure antibodies to the virus and are more appropriate for indicating whether a patient has been exposed to the virus.

The declaration of a national emergency enabled the FDA to activate its EUA policy, which allows for quicker approval of tests. Normally, a test must be assessed in the laboratory (such as with a mock specimen or an inactivated virus) and in a clinical study of patients. Under the EUA, clinical assessment is not required for the approval of a test. Consequently, the clinical performance of a test approved under EUA is unknown.

Collecting a specimen of good quality is critical to the quality of the test result, said Dr. Caliendo, the secretary of IDSA’s board of directors. Clinicians and investigators have used nasopharyngeal swabs, sputum, and specimens collected from deep within the lung. “We’re still collecting data to determine which is the best specimen type.” As coronavirus testing expands, particularly to drive-through testing sites, “we may be using people who are not as experienced, and so you might not get as high a quality specimen in that situation,” Dr. Caliendo added.

The timing of the test influences the quality of the result, as well, because the amount of virus is lower at the onset of symptoms than it is later. Another factor that affects the quality of the results is the test’s sensitivity.

The time to obtain results varies

The value of having several tests available is that it enables many patients to be tested simultaneously, said Dr. Hanson, a member of IDSA’s board of directors. It also helps to reduce potential problems with the supply of test kits. A test manufacturer, however, may supply parts of the test kit but not the whole kit. This requires the hospital or laboratory to obtain the remaining parts from other suppliers. Furthermore, test manufacturers may need to prioritize areas with high rates of infection or transmission when they ship their tests, which limits testing in other areas.

One reason for the lack of a national plan for testing is that the virus has affected different regions at different times, said Dr. Caliendo. Some tests are more difficult to perform than others, and not all laboratories are equally sophisticated, which can limit testing. It is necessary to test not only symptomatic patients who have been hospitalized, but also symptomatic patients in the community, said Dr. Caliendo. “Ideally, we’re going to need to couple acute diagnostics [testing while people are sick] with serologic testing. Serologic testing is going to be important for us to see who has been infected. That will give us an idea of who is left in our community who is at risk for developing infection.”

How quickly test results are available depends on the type of test and where it is administered. Recently established drive-through clinics can provide results in about 30 minutes. Tests performed in hospitals may take between 1 and 6 hours to yield results. “The issue is, do we have reagents that day?” said Dr. Caliendo. “We have to be careful whom we choose to test, and we screen that in the hospital so that we have enough tests to run as we need them.” But many locations have backlogs. “When you have a backlog of testing, you’re going to wait days, unfortunately, to get a result,” said Dr. Caliendo.

Dr. Caliendo and Dr. Hanson did not report disclosures for this briefing.

U.S. hospitals facing severe challenges from COVID-19, HHS report says

Hospitals across the country encountered severe challenges as the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic swept over them, and they anticipated much worse to come, according to a new report from the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

From March 23 to 27, the OIG interviewed 323 hospitals of several types in 46 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The report it pulled together from these interviews is intended to help HHS manage the crisis, rather than to review its response to the pandemic, the OIG said.

The most significant hospital challenges, the report states, were testing and caring for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 and protecting staff members. In addition, the hospitals faced challenges in maintaining or expanding their capacities to treat COVID-19 patients and ensuring the adequacy of basic supplies.

The critical shortages of ventilators, personal protective equipment (PPE), and test kits in hospitals have been widely reported by the media. But the OIG report also focused on some areas that have received less press attention.

To begin with, the shortage of tests has not only slowed the national response to the pandemic, but has had a major impact on inpatient care, according to the report’s authors. The limited number of test kits means that only symptomatic staff members and patients can be tested; in some hospitals, there aren’t even enough tests for that, and some facilities subdivided the test kits they had, the report states.

Moreover, the test results often took 7 days or more to come back from commercial or government labs, the report states. In the meantime, symptomatic patients were presumed to have the coronavirus. While awaiting the results, they had to stay in the hospital, using beds and requiring staff who could otherwise have been assigned to other patients.

The doctors and nurse who cared for these presumptive COVID-19 patients also had to take time suiting up in PPE before seeing them; much of that scarce PPE was wasted on those who were later found not to have the illness.

As one administrator explained to OIG, “Sitting with 60 patients with presumed positives in our hospital isn’t healthy for anybody.”

Delayed test results also reduced hospitals’ ability to provide care by sidelining clinicians who reported COVID-19 symptoms. In one hospital, 20% to 25% of staff were determined to be presumptively positive for COVID-19. As a result of their tests not being analyzed promptly, these doctors and nurses were prevented from providing clinical services for longer than necessary.

Supply Shortages

The report also described some factors contributing to mask shortages. Because of the fear factor, for example, all staff members in one hospital were wearing masks, instead of just those in designated areas. An administrator said the hospital was using 2,000 masks a day, 10 times the number before the COVID-19 crisis.

Another hospital received 2,300 N95 masks from a state reserve, but they were unusable because the elastic bands had dry-rotted.

Meanwhile, some vendors were profiteering. Masks that used to cost 50 cents now sold for $6 each, one administrator said.

To combat the supply chain disruptions, some facilities were buying PPE from nontraditional sources such as online retailers, home supply stores, paint stores, autobody supply shops, and beauty salons. Other hospitals were using non–medical-grade PPE such as construction masks and handmade masks and gowns.

Other hospitals reported they were conserving and reusing PPE to stretch their supplies. In some cases, they had even changed policies to reduce the extent and frequency of patient interactions with clinicians so the latter would have to change their gear less often.

Shortages of other critical supplies and materials were also reported. Hospitals were running out of supplies that supported patient rooms, such as IV poles, medical gas, linens, toilet paper, and food.

Hospitals across the country were also expecting or experiencing a shortage of ventilators, although none said any patients had been denied access to them. Some institutions were adapting anesthesia machines and single-use emergency transport ventilators.

Also concerning to hospitals was the shortage of intensive-care specialists and nurses to operate the ventilators and care for critically ill patients. Some facilities were training anesthesiologists, hospitalists, and other nonintensivists on how to use the lifesaving equipment.

Meanwhile, patients with COVID-19 symptoms were continuing to show up in droves at emergency departments. Hospitals were concerned about potential shortages of ICU beds, negative-pressure rooms, and isolation units. Given limited bed availability, some administrators said, it was getting hard to separate COVID-19 from non–COVID-19 patients.

What Hospitals Want

As the COVID-19 crisis continues to mount, many hospitals are facing financial emergencies as well, the report noted.

“Hospitals described increasing costs and decreasing revenues as a threat to their financial viability. Hospitals reported that ceasing elective procedures and other services decreased revenues at the same time that their costs have increased as they prepare for a potential surge of patients. Many hospitals reported that their cash reserves were quickly depleting, which could disrupt ongoing hospital operations,” the authors write.

This report was conducted a few days before the passage of the CURES Act, which earmarked $100 billion for hospitals on the frontline of the crisis. As a recent analysis of financial hospital data revealed, however, even with the 20% bump in Medicare payments for COVID-19 care that this cash infusion represents, many hospitals will face a cash-flow crunch within 60 to 90 days, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Besides higher Medicare payments, the OIG report said, hospitals wanted the government to drop the 14-day waiting period for reimbursement and to offer them loans and grants.

Hospitals also want federal and state governments to relax regulations on professional licensing of, and business relationships with, doctors and other clinicians. They’d like the government to:

- Let them reassign licensed professionals within their hospitals and across healthcare networks

- Provide flexibility with respect to licensed professionals practicing across state lines

- Provide relief from regulations that may restrict using contracted staff or physicians based on business relationships

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospitals across the country encountered severe challenges as the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic swept over them, and they anticipated much worse to come, according to a new report from the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

From March 23 to 27, the OIG interviewed 323 hospitals of several types in 46 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The report it pulled together from these interviews is intended to help HHS manage the crisis, rather than to review its response to the pandemic, the OIG said.

The most significant hospital challenges, the report states, were testing and caring for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 and protecting staff members. In addition, the hospitals faced challenges in maintaining or expanding their capacities to treat COVID-19 patients and ensuring the adequacy of basic supplies.

The critical shortages of ventilators, personal protective equipment (PPE), and test kits in hospitals have been widely reported by the media. But the OIG report also focused on some areas that have received less press attention.

To begin with, the shortage of tests has not only slowed the national response to the pandemic, but has had a major impact on inpatient care, according to the report’s authors. The limited number of test kits means that only symptomatic staff members and patients can be tested; in some hospitals, there aren’t even enough tests for that, and some facilities subdivided the test kits they had, the report states.

Moreover, the test results often took 7 days or more to come back from commercial or government labs, the report states. In the meantime, symptomatic patients were presumed to have the coronavirus. While awaiting the results, they had to stay in the hospital, using beds and requiring staff who could otherwise have been assigned to other patients.

The doctors and nurse who cared for these presumptive COVID-19 patients also had to take time suiting up in PPE before seeing them; much of that scarce PPE was wasted on those who were later found not to have the illness.

As one administrator explained to OIG, “Sitting with 60 patients with presumed positives in our hospital isn’t healthy for anybody.”

Delayed test results also reduced hospitals’ ability to provide care by sidelining clinicians who reported COVID-19 symptoms. In one hospital, 20% to 25% of staff were determined to be presumptively positive for COVID-19. As a result of their tests not being analyzed promptly, these doctors and nurses were prevented from providing clinical services for longer than necessary.

Supply Shortages

The report also described some factors contributing to mask shortages. Because of the fear factor, for example, all staff members in one hospital were wearing masks, instead of just those in designated areas. An administrator said the hospital was using 2,000 masks a day, 10 times the number before the COVID-19 crisis.

Another hospital received 2,300 N95 masks from a state reserve, but they were unusable because the elastic bands had dry-rotted.

Meanwhile, some vendors were profiteering. Masks that used to cost 50 cents now sold for $6 each, one administrator said.

To combat the supply chain disruptions, some facilities were buying PPE from nontraditional sources such as online retailers, home supply stores, paint stores, autobody supply shops, and beauty salons. Other hospitals were using non–medical-grade PPE such as construction masks and handmade masks and gowns.

Other hospitals reported they were conserving and reusing PPE to stretch their supplies. In some cases, they had even changed policies to reduce the extent and frequency of patient interactions with clinicians so the latter would have to change their gear less often.

Shortages of other critical supplies and materials were also reported. Hospitals were running out of supplies that supported patient rooms, such as IV poles, medical gas, linens, toilet paper, and food.

Hospitals across the country were also expecting or experiencing a shortage of ventilators, although none said any patients had been denied access to them. Some institutions were adapting anesthesia machines and single-use emergency transport ventilators.

Also concerning to hospitals was the shortage of intensive-care specialists and nurses to operate the ventilators and care for critically ill patients. Some facilities were training anesthesiologists, hospitalists, and other nonintensivists on how to use the lifesaving equipment.

Meanwhile, patients with COVID-19 symptoms were continuing to show up in droves at emergency departments. Hospitals were concerned about potential shortages of ICU beds, negative-pressure rooms, and isolation units. Given limited bed availability, some administrators said, it was getting hard to separate COVID-19 from non–COVID-19 patients.

What Hospitals Want

As the COVID-19 crisis continues to mount, many hospitals are facing financial emergencies as well, the report noted.

“Hospitals described increasing costs and decreasing revenues as a threat to their financial viability. Hospitals reported that ceasing elective procedures and other services decreased revenues at the same time that their costs have increased as they prepare for a potential surge of patients. Many hospitals reported that their cash reserves were quickly depleting, which could disrupt ongoing hospital operations,” the authors write.

This report was conducted a few days before the passage of the CURES Act, which earmarked $100 billion for hospitals on the frontline of the crisis. As a recent analysis of financial hospital data revealed, however, even with the 20% bump in Medicare payments for COVID-19 care that this cash infusion represents, many hospitals will face a cash-flow crunch within 60 to 90 days, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Besides higher Medicare payments, the OIG report said, hospitals wanted the government to drop the 14-day waiting period for reimbursement and to offer them loans and grants.

Hospitals also want federal and state governments to relax regulations on professional licensing of, and business relationships with, doctors and other clinicians. They’d like the government to:

- Let them reassign licensed professionals within their hospitals and across healthcare networks

- Provide flexibility with respect to licensed professionals practicing across state lines

- Provide relief from regulations that may restrict using contracted staff or physicians based on business relationships

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospitals across the country encountered severe challenges as the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic swept over them, and they anticipated much worse to come, according to a new report from the Office of Inspector General of the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS).

From March 23 to 27, the OIG interviewed 323 hospitals of several types in 46 states, the District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico. The report it pulled together from these interviews is intended to help HHS manage the crisis, rather than to review its response to the pandemic, the OIG said.

The most significant hospital challenges, the report states, were testing and caring for patients with known or suspected COVID-19 and protecting staff members. In addition, the hospitals faced challenges in maintaining or expanding their capacities to treat COVID-19 patients and ensuring the adequacy of basic supplies.

The critical shortages of ventilators, personal protective equipment (PPE), and test kits in hospitals have been widely reported by the media. But the OIG report also focused on some areas that have received less press attention.

To begin with, the shortage of tests has not only slowed the national response to the pandemic, but has had a major impact on inpatient care, according to the report’s authors. The limited number of test kits means that only symptomatic staff members and patients can be tested; in some hospitals, there aren’t even enough tests for that, and some facilities subdivided the test kits they had, the report states.

Moreover, the test results often took 7 days or more to come back from commercial or government labs, the report states. In the meantime, symptomatic patients were presumed to have the coronavirus. While awaiting the results, they had to stay in the hospital, using beds and requiring staff who could otherwise have been assigned to other patients.

The doctors and nurse who cared for these presumptive COVID-19 patients also had to take time suiting up in PPE before seeing them; much of that scarce PPE was wasted on those who were later found not to have the illness.

As one administrator explained to OIG, “Sitting with 60 patients with presumed positives in our hospital isn’t healthy for anybody.”

Delayed test results also reduced hospitals’ ability to provide care by sidelining clinicians who reported COVID-19 symptoms. In one hospital, 20% to 25% of staff were determined to be presumptively positive for COVID-19. As a result of their tests not being analyzed promptly, these doctors and nurses were prevented from providing clinical services for longer than necessary.

Supply Shortages

The report also described some factors contributing to mask shortages. Because of the fear factor, for example, all staff members in one hospital were wearing masks, instead of just those in designated areas. An administrator said the hospital was using 2,000 masks a day, 10 times the number before the COVID-19 crisis.

Another hospital received 2,300 N95 masks from a state reserve, but they were unusable because the elastic bands had dry-rotted.

Meanwhile, some vendors were profiteering. Masks that used to cost 50 cents now sold for $6 each, one administrator said.

To combat the supply chain disruptions, some facilities were buying PPE from nontraditional sources such as online retailers, home supply stores, paint stores, autobody supply shops, and beauty salons. Other hospitals were using non–medical-grade PPE such as construction masks and handmade masks and gowns.

Other hospitals reported they were conserving and reusing PPE to stretch their supplies. In some cases, they had even changed policies to reduce the extent and frequency of patient interactions with clinicians so the latter would have to change their gear less often.

Shortages of other critical supplies and materials were also reported. Hospitals were running out of supplies that supported patient rooms, such as IV poles, medical gas, linens, toilet paper, and food.

Hospitals across the country were also expecting or experiencing a shortage of ventilators, although none said any patients had been denied access to them. Some institutions were adapting anesthesia machines and single-use emergency transport ventilators.

Also concerning to hospitals was the shortage of intensive-care specialists and nurses to operate the ventilators and care for critically ill patients. Some facilities were training anesthesiologists, hospitalists, and other nonintensivists on how to use the lifesaving equipment.

Meanwhile, patients with COVID-19 symptoms were continuing to show up in droves at emergency departments. Hospitals were concerned about potential shortages of ICU beds, negative-pressure rooms, and isolation units. Given limited bed availability, some administrators said, it was getting hard to separate COVID-19 from non–COVID-19 patients.

What Hospitals Want

As the COVID-19 crisis continues to mount, many hospitals are facing financial emergencies as well, the report noted.

“Hospitals described increasing costs and decreasing revenues as a threat to their financial viability. Hospitals reported that ceasing elective procedures and other services decreased revenues at the same time that their costs have increased as they prepare for a potential surge of patients. Many hospitals reported that their cash reserves were quickly depleting, which could disrupt ongoing hospital operations,” the authors write.

This report was conducted a few days before the passage of the CURES Act, which earmarked $100 billion for hospitals on the frontline of the crisis. As a recent analysis of financial hospital data revealed, however, even with the 20% bump in Medicare payments for COVID-19 care that this cash infusion represents, many hospitals will face a cash-flow crunch within 60 to 90 days, as reported by Medscape Medical News.

Besides higher Medicare payments, the OIG report said, hospitals wanted the government to drop the 14-day waiting period for reimbursement and to offer them loans and grants.

Hospitals also want federal and state governments to relax regulations on professional licensing of, and business relationships with, doctors and other clinicians. They’d like the government to:

- Let them reassign licensed professionals within their hospitals and across healthcare networks

- Provide flexibility with respect to licensed professionals practicing across state lines

- Provide relief from regulations that may restrict using contracted staff or physicians based on business relationships

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

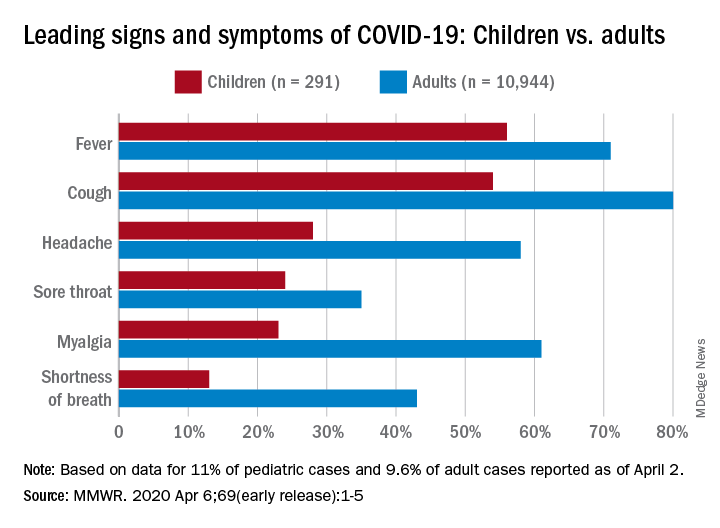

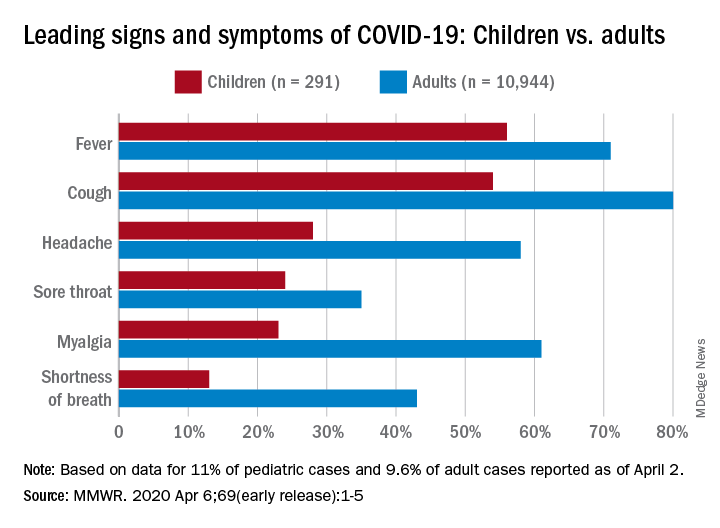

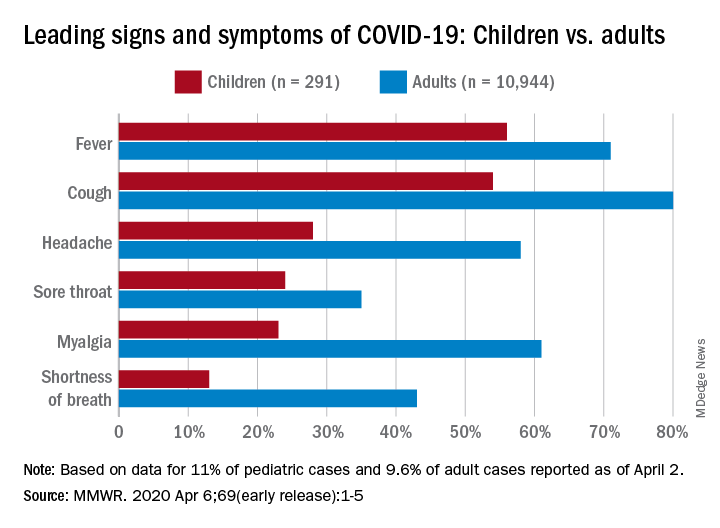

Many children with COVID-19 don’t have cough or fever

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

according to the Centers for Disease and Prevention Control.

Among pediatric patients younger than 18 years in the United States, 73% had at least one of the trio of symptoms, compared with 93% of adults aged 18-64, noted Lucy A. McNamara, PhD, and the CDC’s COVID-19 response team, based on a preliminary analysis of the 149,082 cases reported as of April 2.

By a small margin, fever – present in 58% of pediatric patients – was the most common sign or symptom of COVID-19, compared with cough at 54% and shortness of breath in 13%. In adults, cough (81%) was seen most often, followed by fever (71%) and shortness of breath (43%), the investigators reported in the MMWR.

In both children and adults, headache and myalgia were more common than shortness of breath, as was sore throat in children, the team added.

“These findings are largely consistent with a report on pediatric COVID-19 patients aged <16 years in China, which found that only 41.5% of pediatric patients had fever [and] 48.5% had cough,” they wrote.

The CDC analysis of pediatric patients was limited by its small sample size, with data on signs and symptoms available for only 11% (291) of the 2,572 children known to have COVID-19 as of April 2. The adult population included 10,944 individuals, who represented 9.6% of the 113,985 U.S. patients aged 18-65, the response team said.

“As the number of COVID-19 cases continues to increase in many parts of the United States, it will be important to adapt COVID-19 surveillance strategies to maintain collection of critical case information without overburdening jurisdiction health departments,” they said.

SOURCE: McNamara LA et al. MMWR 2020 Apr 6;69(early release):1-5.

FROM MMWR

AAP issues guidance on managing infants born to mothers with COVID-19

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

“Pediatric cases of COVID-19 are so far reported as less severe than disease occurring among older individuals,” Karen M. Puopolo, MD, PhD, a neonatologist and chief of the section on newborn pediatrics at Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, and coauthors wrote in the 18-page document, which was released on April 2, 2020, along with an abbreviated “Frequently Asked Questions” summary. However, one study of children with COVID-19 in China found that 12% of confirmed cases occurred among 731 infants aged less than 1 year; 24% of those 86 infants “suffered severe or critical illness” (Pediatrics. 2020 March. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-0702). There were no deaths reported among these infants. Other case reports have documented COVID-19 in children aged as young as 2 days.

The document, which was assembled by members of the AAP Committee on Fetus and Newborn, Section on Neonatal Perinatal Medicine, and Committee on Infectious Diseases, pointed out that “considerable uncertainty” exists about the possibility for vertical transmission of SARS-CoV-2 from infected pregnant women to their newborns. “Evidence-based guidelines for managing antenatal, intrapartum, and neonatal care around COVID-19 would require an understanding of whether the virus can be transmitted transplacentally; a determination of which maternal body fluids may be infectious; and data of adequate statistical power that describe which maternal, intrapartum, and neonatal factors influence perinatal transmission,” according to the document. “In the midst of the pandemic these data do not exist, with only limited information currently available to address these issues.”

Based on the best available evidence, the guidance authors recommend that clinicians temporarily separate newborns from affected mothers to minimize the risk of postnatal infant infection from maternal respiratory secretions. “Newborns should be bathed as soon as reasonably possible after birth to remove virus potentially present on skin surfaces,” they wrote. “Clinical staff should use airborne, droplet, and contact precautions until newborn virologic status is known to be negative by SARS-CoV-2 [polymerase chain reaction] testing.”

While SARS-CoV-2 has not been detected in breast milk to date, the authors noted that mothers with COVID-19 can express breast milk to be fed to their infants by uninfected caregivers until specific maternal criteria are met. In addition, infants born to mothers with COVID-19 should be tested for SARS-CoV-2 at 24 hours and, if still in the birth facility, at 48 hours after birth. Centers with limited resources for testing may make individual risk/benefit decisions regarding testing.

For infants infected with SARS-CoV-2 but have no symptoms of the disease, they “may be discharged home on a case-by-case basis with appropriate precautions and plans for frequent outpatient follow-up contacts (either by phone, telemedicine, or in office) through 14 days after birth,” according to the document.

If both infant and mother are discharged from the hospital and the mother still has COVID-19 symptoms, she should maintain at least 6 feet of distance from the baby; if she is in closer proximity she should use a mask and hand hygiene. The mother can stop such precautions until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, and it is at least 7 days since her symptoms first occurred.

In cases where infants require ongoing neonatal intensive care, mothers infected with COVID-19 should not visit their newborn until she is afebrile without the use of antipyretics for at least 72 hours, her respiratory symptoms are improved, and she has negative results of a molecular assay for detection of SARS-CoV-2 from at least two consecutive nasopharyngeal swab specimens collected at least 24 hours apart.

Practicing solo and feeling grateful – despite COVID-19

I know that the world has gone upside down. It’s a nightmare, and people are filled with fear, and death is everywhere. In my little bubble of a world, however, I’ve been doing well.

I can’t lose my job, because I am my job. I’m a solo practitioner and have been for more than a decade. The restrictions to stay at home have not affected me, because I have a home office. Besides, I’m an introvert and see myself as a bit of a recluse, so the social distancing hasn’t been stressful. Conducting appointments by phone rather than face to face hasn’t undermined my work, since I can do everything that I do in my office over the phone. But I do it now in sweats and at my desk in my bedroom more often than not. I am prepared for a decrease in income as people lose their jobs, but that hasn’t happened yet. There are still people out there who are very motivated to come off their medications holistically. No rest for the wicked, as the saying goes.

On an emotional level, I feel calm because I’m not attached to material things, though I like them when they’re here. My children and friends have remained healthy, so I am grateful for that. I feel grounded in my belief that life goes on one way or another, and I trust in God to direct me wherever I need to go. Socially, I’ve been forced to be less lazy and cook more at home. As a result: less salt, MSG, and greasy food. I’ve spent a lot less on restaurants this past month and am eating less since I have to eat whatever I cook.

Can a person be more pandemic proof? I was joking with a friend about how pandemic-friendly my lifestyle is: spiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and socially. Oh, did I forget to mention the year supply of supplements in my office closet? They were for my patients, but those whole food green and red powders may come in handy, just in case.

So, that is how things are going for me. Please don’t hate me for not freaking out. When I read the news, I feel very sad for people who are suffering. I get angry at the politicians who can’t get their egos out of the way. But, I look at the sunshine outside my window, and I feel grateful that, at least in my case, I am not adding to the burden of suffering in the world. Not yet, anyway. I will keep trying to do the little bit that I do to help others for as long as I can.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

I know that the world has gone upside down. It’s a nightmare, and people are filled with fear, and death is everywhere. In my little bubble of a world, however, I’ve been doing well.

I can’t lose my job, because I am my job. I’m a solo practitioner and have been for more than a decade. The restrictions to stay at home have not affected me, because I have a home office. Besides, I’m an introvert and see myself as a bit of a recluse, so the social distancing hasn’t been stressful. Conducting appointments by phone rather than face to face hasn’t undermined my work, since I can do everything that I do in my office over the phone. But I do it now in sweats and at my desk in my bedroom more often than not. I am prepared for a decrease in income as people lose their jobs, but that hasn’t happened yet. There are still people out there who are very motivated to come off their medications holistically. No rest for the wicked, as the saying goes.

On an emotional level, I feel calm because I’m not attached to material things, though I like them when they’re here. My children and friends have remained healthy, so I am grateful for that. I feel grounded in my belief that life goes on one way or another, and I trust in God to direct me wherever I need to go. Socially, I’ve been forced to be less lazy and cook more at home. As a result: less salt, MSG, and greasy food. I’ve spent a lot less on restaurants this past month and am eating less since I have to eat whatever I cook.

Can a person be more pandemic proof? I was joking with a friend about how pandemic-friendly my lifestyle is: spiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and socially. Oh, did I forget to mention the year supply of supplements in my office closet? They were for my patients, but those whole food green and red powders may come in handy, just in case.

So, that is how things are going for me. Please don’t hate me for not freaking out. When I read the news, I feel very sad for people who are suffering. I get angry at the politicians who can’t get their egos out of the way. But, I look at the sunshine outside my window, and I feel grateful that, at least in my case, I am not adding to the burden of suffering in the world. Not yet, anyway. I will keep trying to do the little bit that I do to help others for as long as I can.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

I know that the world has gone upside down. It’s a nightmare, and people are filled with fear, and death is everywhere. In my little bubble of a world, however, I’ve been doing well.

I can’t lose my job, because I am my job. I’m a solo practitioner and have been for more than a decade. The restrictions to stay at home have not affected me, because I have a home office. Besides, I’m an introvert and see myself as a bit of a recluse, so the social distancing hasn’t been stressful. Conducting appointments by phone rather than face to face hasn’t undermined my work, since I can do everything that I do in my office over the phone. But I do it now in sweats and at my desk in my bedroom more often than not. I am prepared for a decrease in income as people lose their jobs, but that hasn’t happened yet. There are still people out there who are very motivated to come off their medications holistically. No rest for the wicked, as the saying goes.

On an emotional level, I feel calm because I’m not attached to material things, though I like them when they’re here. My children and friends have remained healthy, so I am grateful for that. I feel grounded in my belief that life goes on one way or another, and I trust in God to direct me wherever I need to go. Socially, I’ve been forced to be less lazy and cook more at home. As a result: less salt, MSG, and greasy food. I’ve spent a lot less on restaurants this past month and am eating less since I have to eat whatever I cook.

Can a person be more pandemic proof? I was joking with a friend about how pandemic-friendly my lifestyle is: spiritually, mentally, emotionally, physically, and socially. Oh, did I forget to mention the year supply of supplements in my office closet? They were for my patients, but those whole food green and red powders may come in handy, just in case.

So, that is how things are going for me. Please don’t hate me for not freaking out. When I read the news, I feel very sad for people who are suffering. I get angry at the politicians who can’t get their egos out of the way. But, I look at the sunshine outside my window, and I feel grateful that, at least in my case, I am not adding to the burden of suffering in the world. Not yet, anyway. I will keep trying to do the little bit that I do to help others for as long as I can.

Dr. Lee specializes in integrative and holistic psychiatry and has a private practice in Gaithersburg, Md. She has no disclosures.

Which of the changes that coronavirus has forced upon us will remain?

Eventually this strange Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end and life will return to normal.

But obviously it won’t be the same, and like everyone else I wonder what will be different.

Telemedicine is one obvious change in my world, though I don’t know how much yet (granted, no one else does, either). I’m seeing a handful of people that way, limited to established patients, where we’re discussing chronic issues or reviewing recent test results.

If I have to see a new patient or an established one with an urgent issue, I’m still willing to meet them at my office (wearing masks and washing hands frequently). In neurology, a lot still depends on a decent exam. It’s pretty hard to check reflexes, sensory modalities, and muscle tone over the phone. If you think a malpractice attorney is going to give you a pass because you missed something by not examining a patient because of coronavirus ... think again.

I’m not sure how the whole telemedicine thing will play out after the dust settles, at least not at my little practice. I’m currently seeing patients by FaceTime and Skype, neither of which is considered HIPAA compliant. The requirement has been waived during the crisis to make sure people can still see doctors, but I don’t see it lasting beyond that. Privacy will always be a central concern in medicine.

When they declare the pandemic over and say I can’t use FaceTime or Skype anymore, that will likely end my use of such. While there are HIPAA-compliant telemedicine services out there, in a small practice I don’t have the time or money to invest in them.

I also wonder how outcomes will change. I suspect the research-minded will be analyzing 2019 vs. 2020 data for years to come, trying to see if a sudden increase in telemedicine led to better or worse clinical outcomes. I’ll be curious to see what they find and how it breaks down by disease and specialty.

How will work change? Right now my staff of three (including me) are all working separately from home, handling phone calls as if it were another office day. In today’s era that’s easy to set up, and we’re used to the drill from when I’m out of town.

Maybe in the future, on lighter days, I’ll do this more often, and have my staff work from home (on typically busy days I’ll still need them to check patients in and out, fax things, file charts, and do all the other things they do to keep the practice running). The marked decrease in air pollution is certainly noticeable and good for all. When the year is over I’d like to see how non-coronavirus respiratory issues changed between 2019 and 2020.

Other businesses will be looking at that, too, with an increase in telecommuting. Why pay for a large office space when a lot can be done over the Internet? It saves rent, gas, and driving time. How it will affect us, as a socially-dependent species, I have no idea.

It’s the same with grocery delivery. While most of us will likely continue to shop at stores, many will stay with the ease of delivery services after this. It may cost more, but it certainly saves time.

There will be social changes, although how long they’ll last is anyone’s guess. Grocery baggers, stockers, and delivery staff, often seen as lower-level occupations, are now considered part of critical infrastructure in keeping people supplied with food and other necessities, as well as preventing fights from breaking out in the toilet paper and hand-sanitizer aisles.

I’d like to think that, in a country divided, the need to work together will help bring people of different opinions together again, but from the way things look I don’t see that happening, which is sad because viruses don’t discriminate, so we shouldn’t either in fighting them.

Like with other challenges that we face, big and little, I can only hope that we’ll learn something from this and have a better world after it’s over. Only time will tell.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

Eventually this strange Twilight Zone world of coronavirus will end and life will return to normal.

But obviously it won’t be the same, and like everyone else I wonder what will be different.

Telemedicine is one obvious change in my world, though I don’t know how much yet (granted, no one else does, either). I’m seeing a handful of people that way, limited to established patients, where we’re discussing chronic issues or reviewing recent test results.

If I have to see a new patient or an established one with an urgent issue, I’m still willing to meet them at my office (wearing masks and washing hands frequently). In neurology, a lot still depends on a decent exam. It’s pretty hard to check reflexes, sensory modalities, and muscle tone over the phone. If you think a malpractice attorney is going to give you a pass because you missed something by not examining a patient because of coronavirus ... think again.

I’m not sure how the whole telemedicine thing will play out after the dust settles, at least not at my little practice. I’m currently seeing patients by FaceTime and Skype, neither of which is considered HIPAA compliant. The requirement has been waived during the crisis to make sure people can still see doctors, but I don’t see it lasting beyond that. Privacy will always be a central concern in medicine.

When they declare the pandemic over and say I can’t use FaceTime or Skype anymore, that will likely end my use of such. While there are HIPAA-compliant telemedicine services out there, in a small practice I don’t have the time or money to invest in them.

I also wonder how outcomes will change. I suspect the research-minded will be analyzing 2019 vs. 2020 data for years to come, trying to see if a sudden increase in telemedicine led to better or worse clinical outcomes. I’ll be curious to see what they find and how it breaks down by disease and specialty.

How will work change? Right now my staff of three (including me) are all working separately from home, handling phone calls as if it were another office day. In today’s era that’s easy to set up, and we’re used to the drill from when I’m out of town.