User login

Lysosomal acid lipase replacement corrects rare genetic cause of liver failure, atherosclerosis

BOSTON – Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D), a rare genetic cause of marked dyslipidemia that causes early multisystem organ damage, was effectively treated by a human recombinant enzyme to replace deficient lysosomal acid lipase, and the replacement enzyme was well tolerated over a 76-week trial.

LAL-D, when it begins in infancy, is usually fatal within the first year.

When LAL-D occurs later in life, it’s believed to be an “underappreciated cause of fibrosis, cirrhosis, severe dyslipidemia, and early-onset atherosclerosis,” according to Katryn Furuya, MD, and the coauthors of a poster presentation given at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Supplying the human recombinant lysosomal acid lipase, termed sebelipase alfa (SA), to children and adults with LAL-D over a 76-week period resulted in a reduction in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for 98% of participants, normalization of ALT for 51% of participants, and normalization of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels for 65% of patients. Patients on SA also experienced reductions in serum triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and liver fat and total liver volume. “We’re basically replacing what they’re missing,” senior author Barbara Burton, MD, said in an interview.

“The target tissues that we want to get to are the liver, primarily, but also the spleen and the endothelial cells,” said Dr. Burton, professor of gastroenterology at Northwestern University, Chicago. “So the enzyme gets in and then it clears the accumulated fat, and that leads to a reduction in inflammation in the liver, because you don’t have these enlarged lysosomes that are irritating to the cells.”

The effects were seen in LAL-D patients participating in an open-label extension of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of SA. Patients in the placebo arm who began receiving SA “experienced marked and sustained improvements in liver and lipid parameters, mirroring those observed in the SA group during the double-blind period,” wrote Dr. Furuya and her coauthors. Dr. Furuya, currently a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., was a fellow at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., at the time of the study.

The ARISE (Acid Lipase Replacement Investigating Safety and Efficacy) study included patients aged 4 years and older with a confirmed LAL-D diagnosis. They had to have a baseline ALT at least 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and if taking lipid-lowering medications, they had to have been on a stable dose for at least 6 weeks before starting the study, and remain on the stable dose for at least the first 32 weeks of the study.

Patients with a history of hematopoietic or liver transplantation were excluded, as were those with severe liver dysfunction, indicated by a Child-Pugh score falling into class C.

The study began with 66 patients entering a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in which patients received an every-other-week intravenous infusion of SA 1 mg/kg (n = 36), or placebo (n = 30). Median age of participants was 13 years (range, 4-58 years).

After 22 weeks, this was followed by an open-label extension period, during which patients in both arms were unblinded and received SA 1 mg/kg for the duration of the study period; 65/66 patients entered this phase. This means that patients who were initially given SA during the blinded phase of the trial received a total of 76 weeks of SA, while patients who first received placebo before entering the open-label extension did not have their data analyzed until they had been on SA for a total of 78 weeks. The extra 2 weeks accounted for a crossover period for the placebo arm to enter the open-label phase.

The protocol allowed dose increases up to 3 mg/kg if patients’ AST, ALT, LDL-C, or TG levels remained elevated, or if patients under the age of 18 continued to have low weight-for-age z scores. For patients who had problems tolerating SA, the dose could be reduced to 0.35 kg/mg.

Efficacy outcome measures included the proportion of patients who achieved AST and ALT normalization, and those whose ALT values were reduced (but not necessarily normalized). Other measures included changes in LDL-C, HDL-C, non-HDL-C, and TG; reductions in hepatic fat content and total liver volume were also tracked.

After 76 weeks, LDL-C levels were reduced by a mean 27.5%, from 199 to 142 mg/dL, and non-HDL-C dropped by a mean 26.6%, from 230 to 166 mg/dL.

Liver volume and fat content was assessed by multiecho gradient echo magnetic resonance imaging (MEGE-MRI) performed at baseline, at week 20, and at study week 52, representing 52 weeks of SA treatment for the intervention arm and 30 weeks for the placebo arm of the initial trial.

After 52 weeks of SA exposure, the mean hepatic fat reduction was 20.5%, with 88% of patients having reduced liver fat. Of those with 30 weeks of SA exposure, 88% also had reduced liver fat, with a mean fat reduction of 28%.

Liver volume also dropped, by a mean of 13.2% for those with 52 weeks of SA exposure, with 90% of patients experiencing reduced liver volume. Patients with 30 weeks of SA treatment saw a mean 11.2% reduction in liver volume; 96% of this patient group saw some decrease in liver volume.

Safety outcomes included tracking treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), as well as monitoring participants for anti-drug antibodies and for the development of neutralizing antibodies to SA. The safety outcome measures were assessed for patients with longer SA exposure, ranging from 86 to 152 weeks.

There were no patient discontinuations because of TEAEs, and most events were mild or moderate; the only serious adverse event considered related to treatment was an infusion-associated reaction. This patient was able to restart SA therapy after desensitization.

Anti-drug antibodies showed up in 11% of patients (n = 7), and two of these patients had neutralizing antibodies. The safety profile was not different for the group of patients testing positive for anti-drug antibodies, wrote Dr. Furuya and her coauthors.

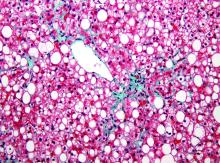

Replacing LAL-D has promise for a population whose disease may go long undetected. “The patients are not obvious. They are difficult to diagnose,” said Dr. Burton. “They look normal, and they feel normal in many cases, until they have life-threatening disease,” such as end-stage liver disease or cardiovascular complications, she said. Even if elevated transaminases are found in routine screening, physicians are much more likely to think of the more-common nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) than LAL-D, said Dr. Burton, noting that an MRI won’t clarify the diagnosis, though a liver biopsy will show microvesicular rather than macrovesicular fat distribution in LAL-D.

When the clinical picture doesn’t fit with NAFLD, though, LAL-D should be in the differential, she said, adding that she suspects the actual incidence of LAL-D may be higher than has been reported in the literature.

Dr. Burton reported receiving research support, consulting fees, and honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals – the study sponsor and manufacturer of sebelipase alfa. Dr. Furuya reported no disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D), a rare genetic cause of marked dyslipidemia that causes early multisystem organ damage, was effectively treated by a human recombinant enzyme to replace deficient lysosomal acid lipase, and the replacement enzyme was well tolerated over a 76-week trial.

LAL-D, when it begins in infancy, is usually fatal within the first year.

When LAL-D occurs later in life, it’s believed to be an “underappreciated cause of fibrosis, cirrhosis, severe dyslipidemia, and early-onset atherosclerosis,” according to Katryn Furuya, MD, and the coauthors of a poster presentation given at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Supplying the human recombinant lysosomal acid lipase, termed sebelipase alfa (SA), to children and adults with LAL-D over a 76-week period resulted in a reduction in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for 98% of participants, normalization of ALT for 51% of participants, and normalization of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels for 65% of patients. Patients on SA also experienced reductions in serum triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and liver fat and total liver volume. “We’re basically replacing what they’re missing,” senior author Barbara Burton, MD, said in an interview.

“The target tissues that we want to get to are the liver, primarily, but also the spleen and the endothelial cells,” said Dr. Burton, professor of gastroenterology at Northwestern University, Chicago. “So the enzyme gets in and then it clears the accumulated fat, and that leads to a reduction in inflammation in the liver, because you don’t have these enlarged lysosomes that are irritating to the cells.”

The effects were seen in LAL-D patients participating in an open-label extension of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of SA. Patients in the placebo arm who began receiving SA “experienced marked and sustained improvements in liver and lipid parameters, mirroring those observed in the SA group during the double-blind period,” wrote Dr. Furuya and her coauthors. Dr. Furuya, currently a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., was a fellow at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., at the time of the study.

The ARISE (Acid Lipase Replacement Investigating Safety and Efficacy) study included patients aged 4 years and older with a confirmed LAL-D diagnosis. They had to have a baseline ALT at least 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and if taking lipid-lowering medications, they had to have been on a stable dose for at least 6 weeks before starting the study, and remain on the stable dose for at least the first 32 weeks of the study.

Patients with a history of hematopoietic or liver transplantation were excluded, as were those with severe liver dysfunction, indicated by a Child-Pugh score falling into class C.

The study began with 66 patients entering a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in which patients received an every-other-week intravenous infusion of SA 1 mg/kg (n = 36), or placebo (n = 30). Median age of participants was 13 years (range, 4-58 years).

After 22 weeks, this was followed by an open-label extension period, during which patients in both arms were unblinded and received SA 1 mg/kg for the duration of the study period; 65/66 patients entered this phase. This means that patients who were initially given SA during the blinded phase of the trial received a total of 76 weeks of SA, while patients who first received placebo before entering the open-label extension did not have their data analyzed until they had been on SA for a total of 78 weeks. The extra 2 weeks accounted for a crossover period for the placebo arm to enter the open-label phase.

The protocol allowed dose increases up to 3 mg/kg if patients’ AST, ALT, LDL-C, or TG levels remained elevated, or if patients under the age of 18 continued to have low weight-for-age z scores. For patients who had problems tolerating SA, the dose could be reduced to 0.35 kg/mg.

Efficacy outcome measures included the proportion of patients who achieved AST and ALT normalization, and those whose ALT values were reduced (but not necessarily normalized). Other measures included changes in LDL-C, HDL-C, non-HDL-C, and TG; reductions in hepatic fat content and total liver volume were also tracked.

After 76 weeks, LDL-C levels were reduced by a mean 27.5%, from 199 to 142 mg/dL, and non-HDL-C dropped by a mean 26.6%, from 230 to 166 mg/dL.

Liver volume and fat content was assessed by multiecho gradient echo magnetic resonance imaging (MEGE-MRI) performed at baseline, at week 20, and at study week 52, representing 52 weeks of SA treatment for the intervention arm and 30 weeks for the placebo arm of the initial trial.

After 52 weeks of SA exposure, the mean hepatic fat reduction was 20.5%, with 88% of patients having reduced liver fat. Of those with 30 weeks of SA exposure, 88% also had reduced liver fat, with a mean fat reduction of 28%.

Liver volume also dropped, by a mean of 13.2% for those with 52 weeks of SA exposure, with 90% of patients experiencing reduced liver volume. Patients with 30 weeks of SA treatment saw a mean 11.2% reduction in liver volume; 96% of this patient group saw some decrease in liver volume.

Safety outcomes included tracking treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), as well as monitoring participants for anti-drug antibodies and for the development of neutralizing antibodies to SA. The safety outcome measures were assessed for patients with longer SA exposure, ranging from 86 to 152 weeks.

There were no patient discontinuations because of TEAEs, and most events were mild or moderate; the only serious adverse event considered related to treatment was an infusion-associated reaction. This patient was able to restart SA therapy after desensitization.

Anti-drug antibodies showed up in 11% of patients (n = 7), and two of these patients had neutralizing antibodies. The safety profile was not different for the group of patients testing positive for anti-drug antibodies, wrote Dr. Furuya and her coauthors.

Replacing LAL-D has promise for a population whose disease may go long undetected. “The patients are not obvious. They are difficult to diagnose,” said Dr. Burton. “They look normal, and they feel normal in many cases, until they have life-threatening disease,” such as end-stage liver disease or cardiovascular complications, she said. Even if elevated transaminases are found in routine screening, physicians are much more likely to think of the more-common nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) than LAL-D, said Dr. Burton, noting that an MRI won’t clarify the diagnosis, though a liver biopsy will show microvesicular rather than macrovesicular fat distribution in LAL-D.

When the clinical picture doesn’t fit with NAFLD, though, LAL-D should be in the differential, she said, adding that she suspects the actual incidence of LAL-D may be higher than has been reported in the literature.

Dr. Burton reported receiving research support, consulting fees, and honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals – the study sponsor and manufacturer of sebelipase alfa. Dr. Furuya reported no disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Lysosomal acid lipase deficiency (LAL-D), a rare genetic cause of marked dyslipidemia that causes early multisystem organ damage, was effectively treated by a human recombinant enzyme to replace deficient lysosomal acid lipase, and the replacement enzyme was well tolerated over a 76-week trial.

LAL-D, when it begins in infancy, is usually fatal within the first year.

When LAL-D occurs later in life, it’s believed to be an “underappreciated cause of fibrosis, cirrhosis, severe dyslipidemia, and early-onset atherosclerosis,” according to Katryn Furuya, MD, and the coauthors of a poster presentation given at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

Supplying the human recombinant lysosomal acid lipase, termed sebelipase alfa (SA), to children and adults with LAL-D over a 76-week period resulted in a reduction in alanine aminotransferase (ALT) for 98% of participants, normalization of ALT for 51% of participants, and normalization of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels for 65% of patients. Patients on SA also experienced reductions in serum triglycerides (TG), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C), and liver fat and total liver volume. “We’re basically replacing what they’re missing,” senior author Barbara Burton, MD, said in an interview.

“The target tissues that we want to get to are the liver, primarily, but also the spleen and the endothelial cells,” said Dr. Burton, professor of gastroenterology at Northwestern University, Chicago. “So the enzyme gets in and then it clears the accumulated fat, and that leads to a reduction in inflammation in the liver, because you don’t have these enlarged lysosomes that are irritating to the cells.”

The effects were seen in LAL-D patients participating in an open-label extension of a double-blind placebo-controlled trial of SA. Patients in the placebo arm who began receiving SA “experienced marked and sustained improvements in liver and lipid parameters, mirroring those observed in the SA group during the double-blind period,” wrote Dr. Furuya and her coauthors. Dr. Furuya, currently a pediatric gastroenterologist at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., was a fellow at the Alfred I. duPont Hospital for Children, Wilmington, Del., at the time of the study.

The ARISE (Acid Lipase Replacement Investigating Safety and Efficacy) study included patients aged 4 years and older with a confirmed LAL-D diagnosis. They had to have a baseline ALT at least 1.5 times the upper limit of normal, and if taking lipid-lowering medications, they had to have been on a stable dose for at least 6 weeks before starting the study, and remain on the stable dose for at least the first 32 weeks of the study.

Patients with a history of hematopoietic or liver transplantation were excluded, as were those with severe liver dysfunction, indicated by a Child-Pugh score falling into class C.

The study began with 66 patients entering a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study in which patients received an every-other-week intravenous infusion of SA 1 mg/kg (n = 36), or placebo (n = 30). Median age of participants was 13 years (range, 4-58 years).

After 22 weeks, this was followed by an open-label extension period, during which patients in both arms were unblinded and received SA 1 mg/kg for the duration of the study period; 65/66 patients entered this phase. This means that patients who were initially given SA during the blinded phase of the trial received a total of 76 weeks of SA, while patients who first received placebo before entering the open-label extension did not have their data analyzed until they had been on SA for a total of 78 weeks. The extra 2 weeks accounted for a crossover period for the placebo arm to enter the open-label phase.

The protocol allowed dose increases up to 3 mg/kg if patients’ AST, ALT, LDL-C, or TG levels remained elevated, or if patients under the age of 18 continued to have low weight-for-age z scores. For patients who had problems tolerating SA, the dose could be reduced to 0.35 kg/mg.

Efficacy outcome measures included the proportion of patients who achieved AST and ALT normalization, and those whose ALT values were reduced (but not necessarily normalized). Other measures included changes in LDL-C, HDL-C, non-HDL-C, and TG; reductions in hepatic fat content and total liver volume were also tracked.

After 76 weeks, LDL-C levels were reduced by a mean 27.5%, from 199 to 142 mg/dL, and non-HDL-C dropped by a mean 26.6%, from 230 to 166 mg/dL.

Liver volume and fat content was assessed by multiecho gradient echo magnetic resonance imaging (MEGE-MRI) performed at baseline, at week 20, and at study week 52, representing 52 weeks of SA treatment for the intervention arm and 30 weeks for the placebo arm of the initial trial.

After 52 weeks of SA exposure, the mean hepatic fat reduction was 20.5%, with 88% of patients having reduced liver fat. Of those with 30 weeks of SA exposure, 88% also had reduced liver fat, with a mean fat reduction of 28%.

Liver volume also dropped, by a mean of 13.2% for those with 52 weeks of SA exposure, with 90% of patients experiencing reduced liver volume. Patients with 30 weeks of SA treatment saw a mean 11.2% reduction in liver volume; 96% of this patient group saw some decrease in liver volume.

Safety outcomes included tracking treatment-emergent adverse events (TEAEs), as well as monitoring participants for anti-drug antibodies and for the development of neutralizing antibodies to SA. The safety outcome measures were assessed for patients with longer SA exposure, ranging from 86 to 152 weeks.

There were no patient discontinuations because of TEAEs, and most events were mild or moderate; the only serious adverse event considered related to treatment was an infusion-associated reaction. This patient was able to restart SA therapy after desensitization.

Anti-drug antibodies showed up in 11% of patients (n = 7), and two of these patients had neutralizing antibodies. The safety profile was not different for the group of patients testing positive for anti-drug antibodies, wrote Dr. Furuya and her coauthors.

Replacing LAL-D has promise for a population whose disease may go long undetected. “The patients are not obvious. They are difficult to diagnose,” said Dr. Burton. “They look normal, and they feel normal in many cases, until they have life-threatening disease,” such as end-stage liver disease or cardiovascular complications, she said. Even if elevated transaminases are found in routine screening, physicians are much more likely to think of the more-common nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) than LAL-D, said Dr. Burton, noting that an MRI won’t clarify the diagnosis, though a liver biopsy will show microvesicular rather than macrovesicular fat distribution in LAL-D.

When the clinical picture doesn’t fit with NAFLD, though, LAL-D should be in the differential, she said, adding that she suspects the actual incidence of LAL-D may be higher than has been reported in the literature.

Dr. Burton reported receiving research support, consulting fees, and honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals – the study sponsor and manufacturer of sebelipase alfa. Dr. Furuya reported no disclosures.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Of patients with LAL-D who received sebelipase alfa (recombinant LAL), 51% experienced normalization of ALT, and 65% had normalization of AST.

Data source: Open-label extension of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of 66 patients with LAL-D.

Disclosures: Dr. Burton reported receiving research support, consulting fees, and honoraria from Alexion Pharmaceuticals – the study sponsor and manufacturer of sebelipase alfa. Dr. Furuya reported no disclosures.

VIDEO: NAFLD costing U.S. $290 billion annually

BOSTON – A sophisticated mathematical analysis shows that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is costing the United States over $290 billion annually. A similar economic burden was seen in several Western European countries as well.

The study, which incorporated available data about current cases of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), looked at both medical and nonmedical costs, as the disease’s economic and social impact extends far beyond medical bills.

“It impacts patients’ quality of life, their work productivity; there’s a significant fatigue associated with that. In addition to this, there is an economic burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,” said the study’s lead author, Zobair Younossi, MD, in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Younossi, executive director of the Center for Liver Diseases at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va., and his coinvestigators constructed a Markov chain to model costs associated with NAFLD. This mathematical technique allows the probability of the occurrence of an event to influence the model’s prediction of the probability of later events, a useful technique when trying to model real-world, dynamic conditions.

They used the Markov chain technique to model the transition of patients along the path of NAFLD progression. States included in the model were nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), NASH with fibrosis, compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, transplant, posttransplant, and death. The probabilities of progressing through these states were built from a meta-analysis and systematic literature review conducted by the authors, which they then adjusted by incorporating real-world data.

According to the model, annual direct medical costs are projected at $103 billion, or $1,613 for each of the 64 million NAFLD patients in the United States. The four European Union countries included in the model were Germany, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. In aggregate, these countries are projected to have about 52 million people with NAFLD, for an annual cost of 35 billion euros. The estimated annual direct cost per patient varies by country, ranging from 354 euros to 1,163 euros.

When societal costs are incorporated, the numbers leap higher: to $292.19 billion in the United States, and over 200 billion euros in the four European countries studied.

In recent work, Dr. Younossi and his colleagues have reached an estimate that about a quarter of the world’s population has NAFLD. He said he was surprised to learn that the highest prevalences were in some areas of South America and the Middle East, with rapid increases in Asia as well.

However, the etiology of NAFLD helps explain these increases. “It’s really a phenotype. A number of different pathways lead to this disease; the most common is the one that is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance,” said Dr. Younossi.

The subset of NAFLD patients who have NASH also risks progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. According to Dr. Younossi’s examination of the UNOS transplant database, NASH is the second leading cause of liver transplantation in the United States, and one of the top three causes of death from liver disease.

These sobering data make the need for medical treatment for NASH an urgent priority, said Dr. Younossi. Currently, lifestyle modification such as weight loss is the only known treatment for NAFLD and NASH, “which is not easy to do,” he noted.

Several candidate drugs are in the pipeline currently. Also, said Dr. Younossi, NASH can be diagnosed only by liver biopsy currently, a risky and expensive procedure. The search is on for accurate and reliable imaging and serum biomarkers for NASH, so physicians can understand who’s most at risk for progression to more serious liver disease.

“The analysis quantifies the enormity of the clinical and economic burden of NAFLD, which will likely increase as incidence of NAFLD continues to rise with the increasing obesity and diabetes rates,” wrote Dr. Younossi and his coauthors.

Dr. Younossi reported having financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – A sophisticated mathematical analysis shows that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is costing the United States over $290 billion annually. A similar economic burden was seen in several Western European countries as well.

The study, which incorporated available data about current cases of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), looked at both medical and nonmedical costs, as the disease’s economic and social impact extends far beyond medical bills.

“It impacts patients’ quality of life, their work productivity; there’s a significant fatigue associated with that. In addition to this, there is an economic burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,” said the study’s lead author, Zobair Younossi, MD, in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Younossi, executive director of the Center for Liver Diseases at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va., and his coinvestigators constructed a Markov chain to model costs associated with NAFLD. This mathematical technique allows the probability of the occurrence of an event to influence the model’s prediction of the probability of later events, a useful technique when trying to model real-world, dynamic conditions.

They used the Markov chain technique to model the transition of patients along the path of NAFLD progression. States included in the model were nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), NASH with fibrosis, compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, transplant, posttransplant, and death. The probabilities of progressing through these states were built from a meta-analysis and systematic literature review conducted by the authors, which they then adjusted by incorporating real-world data.

According to the model, annual direct medical costs are projected at $103 billion, or $1,613 for each of the 64 million NAFLD patients in the United States. The four European Union countries included in the model were Germany, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. In aggregate, these countries are projected to have about 52 million people with NAFLD, for an annual cost of 35 billion euros. The estimated annual direct cost per patient varies by country, ranging from 354 euros to 1,163 euros.

When societal costs are incorporated, the numbers leap higher: to $292.19 billion in the United States, and over 200 billion euros in the four European countries studied.

In recent work, Dr. Younossi and his colleagues have reached an estimate that about a quarter of the world’s population has NAFLD. He said he was surprised to learn that the highest prevalences were in some areas of South America and the Middle East, with rapid increases in Asia as well.

However, the etiology of NAFLD helps explain these increases. “It’s really a phenotype. A number of different pathways lead to this disease; the most common is the one that is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance,” said Dr. Younossi.

The subset of NAFLD patients who have NASH also risks progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. According to Dr. Younossi’s examination of the UNOS transplant database, NASH is the second leading cause of liver transplantation in the United States, and one of the top three causes of death from liver disease.

These sobering data make the need for medical treatment for NASH an urgent priority, said Dr. Younossi. Currently, lifestyle modification such as weight loss is the only known treatment for NAFLD and NASH, “which is not easy to do,” he noted.

Several candidate drugs are in the pipeline currently. Also, said Dr. Younossi, NASH can be diagnosed only by liver biopsy currently, a risky and expensive procedure. The search is on for accurate and reliable imaging and serum biomarkers for NASH, so physicians can understand who’s most at risk for progression to more serious liver disease.

“The analysis quantifies the enormity of the clinical and economic burden of NAFLD, which will likely increase as incidence of NAFLD continues to rise with the increasing obesity and diabetes rates,” wrote Dr. Younossi and his coauthors.

Dr. Younossi reported having financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – A sophisticated mathematical analysis shows that nonalcoholic fatty liver disease is costing the United States over $290 billion annually. A similar economic burden was seen in several Western European countries as well.

The study, which incorporated available data about current cases of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), looked at both medical and nonmedical costs, as the disease’s economic and social impact extends far beyond medical bills.

“It impacts patients’ quality of life, their work productivity; there’s a significant fatigue associated with that. In addition to this, there is an economic burden of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease,” said the study’s lead author, Zobair Younossi, MD, in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Dr. Younossi, executive director of the Center for Liver Diseases at Inova Fairfax Hospital, Falls Church, Va., and his coinvestigators constructed a Markov chain to model costs associated with NAFLD. This mathematical technique allows the probability of the occurrence of an event to influence the model’s prediction of the probability of later events, a useful technique when trying to model real-world, dynamic conditions.

They used the Markov chain technique to model the transition of patients along the path of NAFLD progression. States included in the model were nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), NASH with fibrosis, compensated and decompensated cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, transplant, posttransplant, and death. The probabilities of progressing through these states were built from a meta-analysis and systematic literature review conducted by the authors, which they then adjusted by incorporating real-world data.

According to the model, annual direct medical costs are projected at $103 billion, or $1,613 for each of the 64 million NAFLD patients in the United States. The four European Union countries included in the model were Germany, France, Italy, and the United Kingdom. In aggregate, these countries are projected to have about 52 million people with NAFLD, for an annual cost of 35 billion euros. The estimated annual direct cost per patient varies by country, ranging from 354 euros to 1,163 euros.

When societal costs are incorporated, the numbers leap higher: to $292.19 billion in the United States, and over 200 billion euros in the four European countries studied.

In recent work, Dr. Younossi and his colleagues have reached an estimate that about a quarter of the world’s population has NAFLD. He said he was surprised to learn that the highest prevalences were in some areas of South America and the Middle East, with rapid increases in Asia as well.

However, the etiology of NAFLD helps explain these increases. “It’s really a phenotype. A number of different pathways lead to this disease; the most common is the one that is associated with obesity, type 2 diabetes, and insulin resistance,” said Dr. Younossi.

The subset of NAFLD patients who have NASH also risks progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma. According to Dr. Younossi’s examination of the UNOS transplant database, NASH is the second leading cause of liver transplantation in the United States, and one of the top three causes of death from liver disease.

These sobering data make the need for medical treatment for NASH an urgent priority, said Dr. Younossi. Currently, lifestyle modification such as weight loss is the only known treatment for NAFLD and NASH, “which is not easy to do,” he noted.

Several candidate drugs are in the pipeline currently. Also, said Dr. Younossi, NASH can be diagnosed only by liver biopsy currently, a risky and expensive procedure. The search is on for accurate and reliable imaging and serum biomarkers for NASH, so physicians can understand who’s most at risk for progression to more serious liver disease.

“The analysis quantifies the enormity of the clinical and economic burden of NAFLD, which will likely increase as incidence of NAFLD continues to rise with the increasing obesity and diabetes rates,” wrote Dr. Younossi and his coauthors.

Dr. Younossi reported having financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Annual direct medical costs alone are $1,613 for each of the estimated 64 million U.S. NAFLD patients.

Data source: Markov-chain modeling of NAFLD prevalence and morbidity in the United States and four European countries.

Disclosures: Dr. Younossi reported financial relationships with several pharmaceutical companies.

The Liver Meeting 2016 debrief – key abstracts

BOSTON – Amid a plethora of quality research, several abstracts stood out at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Arun J. Sanyal, MD, said during the final debrief.

He focused first on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which has lacked rigorous studies of disease evolution. Consequently, “current therapeutic development is based on small retrospective data sets with heterogenous populations,” Dr. Sanyal said. Therefore, he and his associates correlated serial biopsies with clinical data (abstract 37). The results confirmed the waxing and waning nature of NAFLD and linked regressing or progressive fibrosis to several factors, including NAFLD Disease Activity score (NAS). NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are “not two different diseases, it’s the same disease,” Dr. Sanyal said. “Establishing disease activity as a driver of disease progression is highly relevant for development of noninvasive biomarkers, and also gives us a foundation for the development of clinical trials in this space.”

Several studies of NASH biomarkers yielded notable results at the meeting. In the largest study to date of circulating microRNAs as markers of NASH, (LB2) the miRNAs 34a, 122a, and 200a distinguished patients with and without NAS scores of at least 4 and at least stage 2 fibrosis with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) between 0.59 and 0.80. “MicroRNAs appear promising, but likely need to be combined with additional biomarkers,” Dr. Sanyal said.

He also noted a study (abstract 40) in which metabolomics of liquid biopsies comprehensively evaluated NAFLD, including fibrosis stage, with AUROCs up to 0.95. Metabolomics “holds promise as a diagnostic tool that can be operationalized for point-of-care testing,” he said.

When it comes to NAFLD, hepatologists “often struggle with what to tell our patients about alcohol,” Dr. Sanyal said. To help clarify the issue, abstract 31 compared NAFLD patients who did or did not report habitually consuming up to two drinks a day in formal prospective questionnaires. After adjustment for baseline histology, abstainers and modest drinkers did not differ on any measure of histologic change, except that abstainers had a greater decrease in steatosis on follow-up biopsy. These findings negate several retrospective studies by suggesting that alcohol consumption does not positively affect the trajectory of NAFLD, Dr. Sanyal concluded.

Many new compounds for treating NASH are in early development, he noted. Among those further along the pipeline, the immunomodulator and CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor cenicriviroc (CVC) missed its primary endpoint (improved NAS and no worsening of fibrosis) but was associated with significantly improved fibrosis without worsening of NASH in the phase 2b CENTAUR study (LB1).

“We also saw highly promising evidence for the effects of ASK1 [apoptosis signal regulating kinase] inhibition on hepatic fibrosis and disease activity in NASH,” Dr. Sanyal added. In a randomized phase II trial (LB3), the ASK1 inhibitor GS-4997 was associated with significant improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH when given in combination with simtuzumab, and also improved liver stiffness and magnetic resonance imaging–estimated proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF). “These very promising and exciting results need confirmation in more advanced, placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Sanyal said.

Studies of alcohol use disorders of the liver confirmed that prednisolone has marginal benefits, that the benefits of steroids in general are offset by sepsis, and that pentoxifylline produced no mortality benefit, Dr. Sanyal noted. In studies of primary biliary cirrhosis, the farnesoid-X receptor agonist obeticholic acid (OCA), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016, was associated with significantly improved AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) and liver stiffness measures by transient elastography at doses of 10 mg or titrated from 5 mg to 10 mg, with or without ursodeoxycholic acid (abstract 209). In another study, patients with PBC who received norUDCA, a side chain–shortened version of UDCA, experienced decreases in serum ALP levels that were dose dependent and differed significantly from trends in the placebo group (abstract 210).

In another study, the investigational ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor GSK2330672 was associated with significant reductions in itch, compared with placebo, and with lower serum bile acids among pruritic PBC patients (abstract 205). Treatment was associated with diarrhea, but it was usually mild and transient.

Dr. Sanyal concluded by reviewing several studies of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. In a prospective randomized controlled trial (abstract 247), lactulose with albumin significantly outperformed lactulose monotherapy for reversing hepatic encephalopathy, reducing hospital stays, and preventing mortality, especially sepsis-related death.

In another multicenter, 24-week, phase IV open-label study (abstract 248), 25% of patients experienced breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy when treated with rifaximin monotherapy, compared with only 14% of patients who received both rifaximin and lactulose.

Finally, in a phase II trial (abstract 2064), rifaximin immediate-release (40 mg) significantly outperformed placebo in terms of cirrhosis-related mortality, hospitalizations for cirrhosis, and breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy. The takeaways? “Use albumin with lactulose for acute hepatic encephalopathy,” Dr. Sanyal said. “Rifaximin with lactulose is better than rifaximin alone for secondary prophylaxis, and rifaximin immediate-release may decrease the need for hospitalization and the first bout of hepatic encephalopathy.”

The Liver Meeting next convenes October 20-24, 2017, in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Sanyal disclosed ties to Genfit, NewCo, Akarna, Elsevier, UptoDate, Novartis, Pfizer, Lilly, Astra Zeneca, and a number of other companies.

BOSTON – Amid a plethora of quality research, several abstracts stood out at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Arun J. Sanyal, MD, said during the final debrief.

He focused first on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which has lacked rigorous studies of disease evolution. Consequently, “current therapeutic development is based on small retrospective data sets with heterogenous populations,” Dr. Sanyal said. Therefore, he and his associates correlated serial biopsies with clinical data (abstract 37). The results confirmed the waxing and waning nature of NAFLD and linked regressing or progressive fibrosis to several factors, including NAFLD Disease Activity score (NAS). NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are “not two different diseases, it’s the same disease,” Dr. Sanyal said. “Establishing disease activity as a driver of disease progression is highly relevant for development of noninvasive biomarkers, and also gives us a foundation for the development of clinical trials in this space.”

Several studies of NASH biomarkers yielded notable results at the meeting. In the largest study to date of circulating microRNAs as markers of NASH, (LB2) the miRNAs 34a, 122a, and 200a distinguished patients with and without NAS scores of at least 4 and at least stage 2 fibrosis with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) between 0.59 and 0.80. “MicroRNAs appear promising, but likely need to be combined with additional biomarkers,” Dr. Sanyal said.

He also noted a study (abstract 40) in which metabolomics of liquid biopsies comprehensively evaluated NAFLD, including fibrosis stage, with AUROCs up to 0.95. Metabolomics “holds promise as a diagnostic tool that can be operationalized for point-of-care testing,” he said.

When it comes to NAFLD, hepatologists “often struggle with what to tell our patients about alcohol,” Dr. Sanyal said. To help clarify the issue, abstract 31 compared NAFLD patients who did or did not report habitually consuming up to two drinks a day in formal prospective questionnaires. After adjustment for baseline histology, abstainers and modest drinkers did not differ on any measure of histologic change, except that abstainers had a greater decrease in steatosis on follow-up biopsy. These findings negate several retrospective studies by suggesting that alcohol consumption does not positively affect the trajectory of NAFLD, Dr. Sanyal concluded.

Many new compounds for treating NASH are in early development, he noted. Among those further along the pipeline, the immunomodulator and CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor cenicriviroc (CVC) missed its primary endpoint (improved NAS and no worsening of fibrosis) but was associated with significantly improved fibrosis without worsening of NASH in the phase 2b CENTAUR study (LB1).

“We also saw highly promising evidence for the effects of ASK1 [apoptosis signal regulating kinase] inhibition on hepatic fibrosis and disease activity in NASH,” Dr. Sanyal added. In a randomized phase II trial (LB3), the ASK1 inhibitor GS-4997 was associated with significant improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH when given in combination with simtuzumab, and also improved liver stiffness and magnetic resonance imaging–estimated proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF). “These very promising and exciting results need confirmation in more advanced, placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Sanyal said.

Studies of alcohol use disorders of the liver confirmed that prednisolone has marginal benefits, that the benefits of steroids in general are offset by sepsis, and that pentoxifylline produced no mortality benefit, Dr. Sanyal noted. In studies of primary biliary cirrhosis, the farnesoid-X receptor agonist obeticholic acid (OCA), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016, was associated with significantly improved AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) and liver stiffness measures by transient elastography at doses of 10 mg or titrated from 5 mg to 10 mg, with or without ursodeoxycholic acid (abstract 209). In another study, patients with PBC who received norUDCA, a side chain–shortened version of UDCA, experienced decreases in serum ALP levels that were dose dependent and differed significantly from trends in the placebo group (abstract 210).

In another study, the investigational ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor GSK2330672 was associated with significant reductions in itch, compared with placebo, and with lower serum bile acids among pruritic PBC patients (abstract 205). Treatment was associated with diarrhea, but it was usually mild and transient.

Dr. Sanyal concluded by reviewing several studies of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. In a prospective randomized controlled trial (abstract 247), lactulose with albumin significantly outperformed lactulose monotherapy for reversing hepatic encephalopathy, reducing hospital stays, and preventing mortality, especially sepsis-related death.

In another multicenter, 24-week, phase IV open-label study (abstract 248), 25% of patients experienced breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy when treated with rifaximin monotherapy, compared with only 14% of patients who received both rifaximin and lactulose.

Finally, in a phase II trial (abstract 2064), rifaximin immediate-release (40 mg) significantly outperformed placebo in terms of cirrhosis-related mortality, hospitalizations for cirrhosis, and breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy. The takeaways? “Use albumin with lactulose for acute hepatic encephalopathy,” Dr. Sanyal said. “Rifaximin with lactulose is better than rifaximin alone for secondary prophylaxis, and rifaximin immediate-release may decrease the need for hospitalization and the first bout of hepatic encephalopathy.”

The Liver Meeting next convenes October 20-24, 2017, in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Sanyal disclosed ties to Genfit, NewCo, Akarna, Elsevier, UptoDate, Novartis, Pfizer, Lilly, Astra Zeneca, and a number of other companies.

BOSTON – Amid a plethora of quality research, several abstracts stood out at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, Arun J. Sanyal, MD, said during the final debrief.

He focused first on nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), which has lacked rigorous studies of disease evolution. Consequently, “current therapeutic development is based on small retrospective data sets with heterogenous populations,” Dr. Sanyal said. Therefore, he and his associates correlated serial biopsies with clinical data (abstract 37). The results confirmed the waxing and waning nature of NAFLD and linked regressing or progressive fibrosis to several factors, including NAFLD Disease Activity score (NAS). NAFLD and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are “not two different diseases, it’s the same disease,” Dr. Sanyal said. “Establishing disease activity as a driver of disease progression is highly relevant for development of noninvasive biomarkers, and also gives us a foundation for the development of clinical trials in this space.”

Several studies of NASH biomarkers yielded notable results at the meeting. In the largest study to date of circulating microRNAs as markers of NASH, (LB2) the miRNAs 34a, 122a, and 200a distinguished patients with and without NAS scores of at least 4 and at least stage 2 fibrosis with areas under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUROC) between 0.59 and 0.80. “MicroRNAs appear promising, but likely need to be combined with additional biomarkers,” Dr. Sanyal said.

He also noted a study (abstract 40) in which metabolomics of liquid biopsies comprehensively evaluated NAFLD, including fibrosis stage, with AUROCs up to 0.95. Metabolomics “holds promise as a diagnostic tool that can be operationalized for point-of-care testing,” he said.

When it comes to NAFLD, hepatologists “often struggle with what to tell our patients about alcohol,” Dr. Sanyal said. To help clarify the issue, abstract 31 compared NAFLD patients who did or did not report habitually consuming up to two drinks a day in formal prospective questionnaires. After adjustment for baseline histology, abstainers and modest drinkers did not differ on any measure of histologic change, except that abstainers had a greater decrease in steatosis on follow-up biopsy. These findings negate several retrospective studies by suggesting that alcohol consumption does not positively affect the trajectory of NAFLD, Dr. Sanyal concluded.

Many new compounds for treating NASH are in early development, he noted. Among those further along the pipeline, the immunomodulator and CCR2/CCR5 inhibitor cenicriviroc (CVC) missed its primary endpoint (improved NAS and no worsening of fibrosis) but was associated with significantly improved fibrosis without worsening of NASH in the phase 2b CENTAUR study (LB1).

“We also saw highly promising evidence for the effects of ASK1 [apoptosis signal regulating kinase] inhibition on hepatic fibrosis and disease activity in NASH,” Dr. Sanyal added. In a randomized phase II trial (LB3), the ASK1 inhibitor GS-4997 was associated with significant improvement in fibrosis without worsening of NASH when given in combination with simtuzumab, and also improved liver stiffness and magnetic resonance imaging–estimated proton density fat fraction (MRI-PDFF). “These very promising and exciting results need confirmation in more advanced, placebo-controlled trials,” Dr. Sanyal said.

Studies of alcohol use disorders of the liver confirmed that prednisolone has marginal benefits, that the benefits of steroids in general are offset by sepsis, and that pentoxifylline produced no mortality benefit, Dr. Sanyal noted. In studies of primary biliary cirrhosis, the farnesoid-X receptor agonist obeticholic acid (OCA), which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2016, was associated with significantly improved AST to Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) and liver stiffness measures by transient elastography at doses of 10 mg or titrated from 5 mg to 10 mg, with or without ursodeoxycholic acid (abstract 209). In another study, patients with PBC who received norUDCA, a side chain–shortened version of UDCA, experienced decreases in serum ALP levels that were dose dependent and differed significantly from trends in the placebo group (abstract 210).

In another study, the investigational ileal bile acid transporter inhibitor GSK2330672 was associated with significant reductions in itch, compared with placebo, and with lower serum bile acids among pruritic PBC patients (abstract 205). Treatment was associated with diarrhea, but it was usually mild and transient.

Dr. Sanyal concluded by reviewing several studies of cirrhosis and hepatic encephalopathy. In a prospective randomized controlled trial (abstract 247), lactulose with albumin significantly outperformed lactulose monotherapy for reversing hepatic encephalopathy, reducing hospital stays, and preventing mortality, especially sepsis-related death.

In another multicenter, 24-week, phase IV open-label study (abstract 248), 25% of patients experienced breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy when treated with rifaximin monotherapy, compared with only 14% of patients who received both rifaximin and lactulose.

Finally, in a phase II trial (abstract 2064), rifaximin immediate-release (40 mg) significantly outperformed placebo in terms of cirrhosis-related mortality, hospitalizations for cirrhosis, and breakthrough hepatic encephalopathy. The takeaways? “Use albumin with lactulose for acute hepatic encephalopathy,” Dr. Sanyal said. “Rifaximin with lactulose is better than rifaximin alone for secondary prophylaxis, and rifaximin immediate-release may decrease the need for hospitalization and the first bout of hepatic encephalopathy.”

The Liver Meeting next convenes October 20-24, 2017, in Washington, D.C.

Dr. Sanyal disclosed ties to Genfit, NewCo, Akarna, Elsevier, UptoDate, Novartis, Pfizer, Lilly, Astra Zeneca, and a number of other companies.

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2016

VIDEO: Hepato-adrenal syndrome is an under-recognized source of ICU morbidity

BOSTON – Patients with serious liver disease who also had hepato-adrenal syndrome had significantly longer hospital stays; these patients had significantly longer ICU courses as well.

According to a recent study of this under-recognized syndrome, patients with cirrhosis, acute liver failure, or acute liver injury who also had clinically significant adrenocortical dysfunction had longer hospital stays when compared to patients without hepato-adrenal syndrome (HAS).

Presenting the study findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, Christina Lindenmeyer, MD, and her associates noted that the longer stays for HAS patients with serious liver disease held true even after adjustment for gender, blood glucose levels, and Child-Pugh score (median 29 days, HAS; 17 days, non-HAS; P = .001).

Further, the patients with HAS were more likely to have a prolonged ICU stay, after multivariable analysis adjusted for a variety of factors including the need for mechanical ventilation, age, bilirubin level, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and severity of encephalopathy (13.5 vs. 4.9 days; P = .002).

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Patients with cirrhosis commonly have hypotension, and I think it’s underrecognized that the elevated levels of endotoxin and the low levels of lipoprotein circulating in patients with cirrhosis can lead to adrenocortical dysfunction,” Dr. Lindenmeyer said in a video interview.

The single-center study enrolled ICU patients with cirrhosis, acute liver injury, and/or acute liver failure who had random cortisol or adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH) stimulation test results. From 2008 to 2014, the tertiary care center saw 69 patients meeting these criteria; 32 patients (46%) had HAS. The mean age was 57.4 years, and 63.8% of enrolled patients were male. There were no significant differences in these demographics between the groups. Serum bicarbonate was higher in patients with HAS (21.4 vs. 17.5 mEq/L; P = .020); other blood chemistries, mean arterial pressures, and the MELD and Child-Pugh scores did not differ significantly between groups.

Dr. Lindenmeyer, a fellow in the Cleveland Clinic’s department of gastroenterology and hepatology, said that the accepted definition of HAS is a random cortisol level of less than 15 mcg/dL in “patients who were highly stressed in the ICU, typically with respiratory failure or hypotension,” she said. For non-ICU patients, the random cortisol level should be less than 20 mcg/dL. An alternative criterion is a post-ACTH stimulation test cortisol level of less than 20 mcg/dL.

Though there was no statistically significant difference between in-hospital mortality for those patients meeting HAS criteria, the trend was actually for those patients to have lower in-hospital mortality (44% vs. 51%; P = .53). This was true even after correction for MELD scores and serum potassium levels. Dr. Lindenmeyer said these results were “a little surprising,” and noted that the study didn’t examine 90-day or 1-year mortality. “That would be something interesting to look at,” she said.

“Early recognition and treatment of HAS may improve judicious allocation of critical care and hospital resources,” wrote Dr. Lindenmeyer and her colleagues.

Dr. Lindenmeyer reported no conflicts of interest, and there were no outside sources of funding reported.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Patients with serious liver disease who also had hepato-adrenal syndrome had significantly longer hospital stays; these patients had significantly longer ICU courses as well.

According to a recent study of this under-recognized syndrome, patients with cirrhosis, acute liver failure, or acute liver injury who also had clinically significant adrenocortical dysfunction had longer hospital stays when compared to patients without hepato-adrenal syndrome (HAS).

Presenting the study findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, Christina Lindenmeyer, MD, and her associates noted that the longer stays for HAS patients with serious liver disease held true even after adjustment for gender, blood glucose levels, and Child-Pugh score (median 29 days, HAS; 17 days, non-HAS; P = .001).

Further, the patients with HAS were more likely to have a prolonged ICU stay, after multivariable analysis adjusted for a variety of factors including the need for mechanical ventilation, age, bilirubin level, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and severity of encephalopathy (13.5 vs. 4.9 days; P = .002).

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Patients with cirrhosis commonly have hypotension, and I think it’s underrecognized that the elevated levels of endotoxin and the low levels of lipoprotein circulating in patients with cirrhosis can lead to adrenocortical dysfunction,” Dr. Lindenmeyer said in a video interview.

The single-center study enrolled ICU patients with cirrhosis, acute liver injury, and/or acute liver failure who had random cortisol or adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH) stimulation test results. From 2008 to 2014, the tertiary care center saw 69 patients meeting these criteria; 32 patients (46%) had HAS. The mean age was 57.4 years, and 63.8% of enrolled patients were male. There were no significant differences in these demographics between the groups. Serum bicarbonate was higher in patients with HAS (21.4 vs. 17.5 mEq/L; P = .020); other blood chemistries, mean arterial pressures, and the MELD and Child-Pugh scores did not differ significantly between groups.

Dr. Lindenmeyer, a fellow in the Cleveland Clinic’s department of gastroenterology and hepatology, said that the accepted definition of HAS is a random cortisol level of less than 15 mcg/dL in “patients who were highly stressed in the ICU, typically with respiratory failure or hypotension,” she said. For non-ICU patients, the random cortisol level should be less than 20 mcg/dL. An alternative criterion is a post-ACTH stimulation test cortisol level of less than 20 mcg/dL.

Though there was no statistically significant difference between in-hospital mortality for those patients meeting HAS criteria, the trend was actually for those patients to have lower in-hospital mortality (44% vs. 51%; P = .53). This was true even after correction for MELD scores and serum potassium levels. Dr. Lindenmeyer said these results were “a little surprising,” and noted that the study didn’t examine 90-day or 1-year mortality. “That would be something interesting to look at,” she said.

“Early recognition and treatment of HAS may improve judicious allocation of critical care and hospital resources,” wrote Dr. Lindenmeyer and her colleagues.

Dr. Lindenmeyer reported no conflicts of interest, and there were no outside sources of funding reported.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

BOSTON – Patients with serious liver disease who also had hepato-adrenal syndrome had significantly longer hospital stays; these patients had significantly longer ICU courses as well.

According to a recent study of this under-recognized syndrome, patients with cirrhosis, acute liver failure, or acute liver injury who also had clinically significant adrenocortical dysfunction had longer hospital stays when compared to patients without hepato-adrenal syndrome (HAS).

Presenting the study findings at a poster session at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Disease, Christina Lindenmeyer, MD, and her associates noted that the longer stays for HAS patients with serious liver disease held true even after adjustment for gender, blood glucose levels, and Child-Pugh score (median 29 days, HAS; 17 days, non-HAS; P = .001).

Further, the patients with HAS were more likely to have a prolonged ICU stay, after multivariable analysis adjusted for a variety of factors including the need for mechanical ventilation, age, bilirubin level, Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) score, and severity of encephalopathy (13.5 vs. 4.9 days; P = .002).

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

“Patients with cirrhosis commonly have hypotension, and I think it’s underrecognized that the elevated levels of endotoxin and the low levels of lipoprotein circulating in patients with cirrhosis can lead to adrenocortical dysfunction,” Dr. Lindenmeyer said in a video interview.

The single-center study enrolled ICU patients with cirrhosis, acute liver injury, and/or acute liver failure who had random cortisol or adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone (ACTH) stimulation test results. From 2008 to 2014, the tertiary care center saw 69 patients meeting these criteria; 32 patients (46%) had HAS. The mean age was 57.4 years, and 63.8% of enrolled patients were male. There were no significant differences in these demographics between the groups. Serum bicarbonate was higher in patients with HAS (21.4 vs. 17.5 mEq/L; P = .020); other blood chemistries, mean arterial pressures, and the MELD and Child-Pugh scores did not differ significantly between groups.

Dr. Lindenmeyer, a fellow in the Cleveland Clinic’s department of gastroenterology and hepatology, said that the accepted definition of HAS is a random cortisol level of less than 15 mcg/dL in “patients who were highly stressed in the ICU, typically with respiratory failure or hypotension,” she said. For non-ICU patients, the random cortisol level should be less than 20 mcg/dL. An alternative criterion is a post-ACTH stimulation test cortisol level of less than 20 mcg/dL.

Though there was no statistically significant difference between in-hospital mortality for those patients meeting HAS criteria, the trend was actually for those patients to have lower in-hospital mortality (44% vs. 51%; P = .53). This was true even after correction for MELD scores and serum potassium levels. Dr. Lindenmeyer said these results were “a little surprising,” and noted that the study didn’t examine 90-day or 1-year mortality. “That would be something interesting to look at,” she said.

“Early recognition and treatment of HAS may improve judicious allocation of critical care and hospital resources,” wrote Dr. Lindenmeyer and her colleagues.

Dr. Lindenmeyer reported no conflicts of interest, and there were no outside sources of funding reported.

koakes@frontlinemedcom.com

On Twitter @karioakes

AT THE LIVER MEETING 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients with HAS had a longer length of hospital stay (median 29 days, HAS; 17 days, non-HAS; P = .001)

Data source: Single-center study of 69 consecutively enrolled ICU patients with serious liver disease and random cortisol or adrenocorticotropin-releasing hormone results.

Disclosures: The study investigators reported no disclosures, and no external sources of funding.

HCV patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma can achieve SVR

BOSTON – Among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), rates of sustained viral response (SVR) to direct-acting regimens for hepatitis C virus were 79% for genotype 1, 69% for genotype 2, and 47% for genotype 3 infections, reported George N. Ioannou, MD.

“These rates are lower than in patients who do not have hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC], but are still remarkably high,” Dr. Ioannou said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “Antiviral therapy should be considered in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, ideally after adequate locoregional treatments.”

The study included Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting anti-HCV regimens. When patients did not have HCC, SVR rates were 93% for genotype 1 infection, 87% for genotype 2 (GT2), and 76% for GT3. Among the 624 (3.6%) patients with a history of HCC, 142 underwent antiviral treatment after transplantation and 482 received other types of cancer therapy.

Why HCC is associated with lower SVR in HCV patients remains unclear, Dr. Ioannou noted. Age does not seem to explain the effect, and neither does sex, race, or ethnicity; cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis; renal disease; diabetes; HCV viral load; genotype or subgenotype; HCV regimen; or treatment experience, he said.

Dr. Ioannou noted several study limitations. Nine percent of patients lacked data on SVR, and the imputation to correct for this lowered SVR rates by about 1%-2%. The dataset also did not include information on HCC tumor size or number, and the researchers have not yet examined how antiviral therapy affects the likelihood of de novo HCC, recurrent HCC, or progression of cirrhosis and liver dysfunction.

The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study. Dr. Ioannou had no disclosures.

BOSTON – Among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), rates of sustained viral response (SVR) to direct-acting regimens for hepatitis C virus were 79% for genotype 1, 69% for genotype 2, and 47% for genotype 3 infections, reported George N. Ioannou, MD.

“These rates are lower than in patients who do not have hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC], but are still remarkably high,” Dr. Ioannou said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “Antiviral therapy should be considered in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, ideally after adequate locoregional treatments.”

The study included Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting anti-HCV regimens. When patients did not have HCC, SVR rates were 93% for genotype 1 infection, 87% for genotype 2 (GT2), and 76% for GT3. Among the 624 (3.6%) patients with a history of HCC, 142 underwent antiviral treatment after transplantation and 482 received other types of cancer therapy.

Why HCC is associated with lower SVR in HCV patients remains unclear, Dr. Ioannou noted. Age does not seem to explain the effect, and neither does sex, race, or ethnicity; cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis; renal disease; diabetes; HCV viral load; genotype or subgenotype; HCV regimen; or treatment experience, he said.

Dr. Ioannou noted several study limitations. Nine percent of patients lacked data on SVR, and the imputation to correct for this lowered SVR rates by about 1%-2%. The dataset also did not include information on HCC tumor size or number, and the researchers have not yet examined how antiviral therapy affects the likelihood of de novo HCC, recurrent HCC, or progression of cirrhosis and liver dysfunction.

The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study. Dr. Ioannou had no disclosures.

BOSTON – Among patients with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), rates of sustained viral response (SVR) to direct-acting regimens for hepatitis C virus were 79% for genotype 1, 69% for genotype 2, and 47% for genotype 3 infections, reported George N. Ioannou, MD.

“These rates are lower than in patients who do not have hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC], but are still remarkably high,” Dr. Ioannou said during an oral presentation at the annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. “Antiviral therapy should be considered in patients with early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma, ideally after adequate locoregional treatments.”

The study included Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting anti-HCV regimens. When patients did not have HCC, SVR rates were 93% for genotype 1 infection, 87% for genotype 2 (GT2), and 76% for GT3. Among the 624 (3.6%) patients with a history of HCC, 142 underwent antiviral treatment after transplantation and 482 received other types of cancer therapy.

Why HCC is associated with lower SVR in HCV patients remains unclear, Dr. Ioannou noted. Age does not seem to explain the effect, and neither does sex, race, or ethnicity; cirrhosis or decompensated cirrhosis; renal disease; diabetes; HCV viral load; genotype or subgenotype; HCV regimen; or treatment experience, he said.

Dr. Ioannou noted several study limitations. Nine percent of patients lacked data on SVR, and the imputation to correct for this lowered SVR rates by about 1%-2%. The dataset also did not include information on HCC tumor size or number, and the researchers have not yet examined how antiviral therapy affects the likelihood of de novo HCC, recurrent HCC, or progression of cirrhosis and liver dysfunction.

The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study. Dr. Ioannou had no disclosures.

AT THE LIVER MEETING

Key clinical point: Consider direct-acting antiviral therapy in HCV-infected patients with early-stage HCC.

Major finding: Rates of sustained viral response were 79% in HCC patients with GT1 HCV infection, 69% in GT2 patients, and 47% in GT3 patients.

Data source: An analysis of Veterans Affairs Health Care System data on 17,487 recipients of direct-acting antiviral regimens, including 624 patients with HCC.

Disclosures: The Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development sponsored the study.

Early TIPS effective in high-risk cirrhosis patients, but still underutilized

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

BOSTON – High-risk cirrhosis patients treated early with a transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) showed increased survival rates and reduced rates of adverse events, according to a study.

The data were presented at the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases by Virginia Hernandez-Gea, MD, a hepatologist at the Hospital Clinic in Barcelona.

In each study arm, three-quarters were men in their mid-50s. Cirrhosis in the non-TIPS group was alcohol-related in 57.4% of the cohort, compared with 71.2% of the group given early TIPS; roughly half of each group mentioned alcohol use in the past 3 months.

Also similar were Model for End-stage Liver Disease (MELD) scores: an average of 15.5 in the non-TIPS group, compared with 15 on average in the TIPS group. Nearly three-quarters of the TIPS group had a Child-Pugh C score, compared with 64% in the non-TIPS group. A Child-Pugh score with active bleeding was recorded in 28.8% of the TIPS group, compared with 36% in the non-TIPS group.

The transplant-free survival rate at 1 year in the standard care group was 61%, compared with 76% in the early TIPS group (P = .0175). The failure and bleeding rate at 1 year was significantly higher in the standard care group: 91%, compared with 68% in the early TIPS group (P = .004). Failure and bleeding rates in the Child-Pugh B and C groups across the study were similar.

Ascites at 1 year was seen in 88% of the standard care group, compared with in 64% of the study group. Rates of hepatic encephalopathy were similar in those with Child-Pugh B with active bleeding, and Child-Pugh C across both groups: 22% in the standard care group vs. 25% in the early TIPS group.

That there was no associated significant risk of hepatic encephalopathy in persons with acute variceal bleeding who were given early TIPS “strongly suggests that early TIPS should be included in clinical practice,” Dr. Hernandez-Gea said, noting that only 10% of the 34 sites in the study had used early TIPS. “We don’t really know why centers are not using this, since it is very difficult to find treatments that extend survival rates in this population.”

AT THE LIVER MEETING

Key clinical point:

Major finding: At 1 year post procedure, early TIPS was associated with better rates of survival and lower rates of adverse events, compared with those who did not receive early TIPS.