User login

Rapid action or sustained effect? Methotrexate vs. ciclosporin for pediatric AD

MONTREAL – in the TREAT study, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

The findings are important, since many regulatory bodies require patients to have tried such first-line conventional systemic therapies before moving on to novel therapeutics, explained Carsten Flohr, MD, PhD, research and development lead at St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust London.

“We don’t really have much pediatric trial data; very often the pediatric data that we have is buried in adult trials and when it comes to an adequately powered randomized controlled trial with conventional systemic medication in pediatric patients, we don’t have one – so we’re lacking that gold standard,” said Dr. Flohr, chair in dermatology and population health sciences at King’s College London.

In the TREAT trial, 103 patients with AD (mean age, 10 years) who had not responded to topical treatment, were randomly assigned to oral ciclosporin (4 mg/kg daily) or methotrexate (0.4 mg/kg weekly) for 36 weeks and then followed for another 24 weeks off therapy for the co-primary outcomes of change in objective Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (o-SCORAD) at 12 weeks, as well as time to first significant flare after treatment cessation, defined as returning to baseline o-SCORAD, or restarting a systemic treatment.

Secondary outcomes included disease severity and quality of life (QOL) measures, as well as safety. At baseline, the mean o-SCORAD was 46.81, with mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores of 28.05 and 20.62 respectively. The mean Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) score was 14.96.

Looking at change in eczema severity measured by o-SCORAD at 12 weeks, ciclosporin was superior to methotrexate, with a mean difference in o-SCORAD change of -5.69 (P =.01). For the co-primary endpoint of time to first significant flare during the 24 weeks after treatment cessation, “there was a trend toward more flare activity in the ciclosporin group, although with a hazard ratio of 1.55, this was statistically not significant,” Dr. Flohr said.

On a graph showing mean EASI scores from baseline through the 60-week study period, Dr. Flohr explained how the score first dropped more precipitously in patients treated with ciclosporin compared with those treated with methotrexate, reaching a statistically significant difference between the groups by 12 weeks (–3.13, P = .0145).

However, after that time, while the EASI score among those on methotrexate continued to drop, the ciclosporin score evened out, so that by 20 weeks, methotrexate EASI scores were better, and remained so until the end of treatment and further, out to 60 weeks (mean difference -6.36, P < .001). “The most interesting bit of this graph is [that] the curve is pointing downwards for methotrexate up to the 9-month point, suggesting these people had not reached their full therapeutic potential yet, whereas if you’re on ciclosporin you plateau and there’s not much additional improvement, if at all, and then people [on ciclosporin] start going up in their disease activity off therapy,” he said.

The same pattern was seen with all the other outcome measures, including o-SCORAD and POEM.

Quality of life significantly improved by about 8 points in both treatment groups, with no significant differences between groups, and this improvement was sustained through the 24 weeks following cessation of therapy. However, during this treatment-free phase, patients on methotrexate had fewer parent-reported flares compared with those on ciclosporin (mean 6.19 vs 5.40 flares, P =.0251), although there was no difference between groups in time to first flare.

Describing the treatment safety as “overall reassuring,” Dr. Flohr said there were slightly more nonserious adverse events in the methotrexate arm (407 vs. 369), with nausea occurring more often in this group (43.1% vs. 17.6%).

“I think we were seeing this clinically, but to see it in a clinical trial gives us more confidence in discussing with parents,” said session moderator Melinda Gooderham, MD, assistant professor at Queens University, Kingston, Ont., and medical director at the SKiN Centre for Dermatology in Peterborough.

What she also took away from the study was safety of these treatments. “The discontinuation rate was not different with either drug, so it’s not like ciclosporin works fast but all these people have problems and discontinue,” Dr. Gooderham told this news organization. “That’s also reassuring.”

Asked which treatment she prefers, Dr. Gooderham, a consultant physician at Peterborough Regional Health Centre, picked methotrexate “because of the lasting effect. But there are times when you may need more rapid control ... where I might choose ciclosporin first, but for me it’s maybe 90% methotrexate first, 10% ciclosporin.”

Dr. Flohr and Dr. Gooderham report no relevant financial relationships. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – in the TREAT study, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

The findings are important, since many regulatory bodies require patients to have tried such first-line conventional systemic therapies before moving on to novel therapeutics, explained Carsten Flohr, MD, PhD, research and development lead at St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust London.

“We don’t really have much pediatric trial data; very often the pediatric data that we have is buried in adult trials and when it comes to an adequately powered randomized controlled trial with conventional systemic medication in pediatric patients, we don’t have one – so we’re lacking that gold standard,” said Dr. Flohr, chair in dermatology and population health sciences at King’s College London.

In the TREAT trial, 103 patients with AD (mean age, 10 years) who had not responded to topical treatment, were randomly assigned to oral ciclosporin (4 mg/kg daily) or methotrexate (0.4 mg/kg weekly) for 36 weeks and then followed for another 24 weeks off therapy for the co-primary outcomes of change in objective Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (o-SCORAD) at 12 weeks, as well as time to first significant flare after treatment cessation, defined as returning to baseline o-SCORAD, or restarting a systemic treatment.

Secondary outcomes included disease severity and quality of life (QOL) measures, as well as safety. At baseline, the mean o-SCORAD was 46.81, with mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores of 28.05 and 20.62 respectively. The mean Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) score was 14.96.

Looking at change in eczema severity measured by o-SCORAD at 12 weeks, ciclosporin was superior to methotrexate, with a mean difference in o-SCORAD change of -5.69 (P =.01). For the co-primary endpoint of time to first significant flare during the 24 weeks after treatment cessation, “there was a trend toward more flare activity in the ciclosporin group, although with a hazard ratio of 1.55, this was statistically not significant,” Dr. Flohr said.

On a graph showing mean EASI scores from baseline through the 60-week study period, Dr. Flohr explained how the score first dropped more precipitously in patients treated with ciclosporin compared with those treated with methotrexate, reaching a statistically significant difference between the groups by 12 weeks (–3.13, P = .0145).

However, after that time, while the EASI score among those on methotrexate continued to drop, the ciclosporin score evened out, so that by 20 weeks, methotrexate EASI scores were better, and remained so until the end of treatment and further, out to 60 weeks (mean difference -6.36, P < .001). “The most interesting bit of this graph is [that] the curve is pointing downwards for methotrexate up to the 9-month point, suggesting these people had not reached their full therapeutic potential yet, whereas if you’re on ciclosporin you plateau and there’s not much additional improvement, if at all, and then people [on ciclosporin] start going up in their disease activity off therapy,” he said.

The same pattern was seen with all the other outcome measures, including o-SCORAD and POEM.

Quality of life significantly improved by about 8 points in both treatment groups, with no significant differences between groups, and this improvement was sustained through the 24 weeks following cessation of therapy. However, during this treatment-free phase, patients on methotrexate had fewer parent-reported flares compared with those on ciclosporin (mean 6.19 vs 5.40 flares, P =.0251), although there was no difference between groups in time to first flare.

Describing the treatment safety as “overall reassuring,” Dr. Flohr said there were slightly more nonserious adverse events in the methotrexate arm (407 vs. 369), with nausea occurring more often in this group (43.1% vs. 17.6%).

“I think we were seeing this clinically, but to see it in a clinical trial gives us more confidence in discussing with parents,” said session moderator Melinda Gooderham, MD, assistant professor at Queens University, Kingston, Ont., and medical director at the SKiN Centre for Dermatology in Peterborough.

What she also took away from the study was safety of these treatments. “The discontinuation rate was not different with either drug, so it’s not like ciclosporin works fast but all these people have problems and discontinue,” Dr. Gooderham told this news organization. “That’s also reassuring.”

Asked which treatment she prefers, Dr. Gooderham, a consultant physician at Peterborough Regional Health Centre, picked methotrexate “because of the lasting effect. But there are times when you may need more rapid control ... where I might choose ciclosporin first, but for me it’s maybe 90% methotrexate first, 10% ciclosporin.”

Dr. Flohr and Dr. Gooderham report no relevant financial relationships. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – in the TREAT study, investigators reported at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

The findings are important, since many regulatory bodies require patients to have tried such first-line conventional systemic therapies before moving on to novel therapeutics, explained Carsten Flohr, MD, PhD, research and development lead at St John’s Institute of Dermatology, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust London.

“We don’t really have much pediatric trial data; very often the pediatric data that we have is buried in adult trials and when it comes to an adequately powered randomized controlled trial with conventional systemic medication in pediatric patients, we don’t have one – so we’re lacking that gold standard,” said Dr. Flohr, chair in dermatology and population health sciences at King’s College London.

In the TREAT trial, 103 patients with AD (mean age, 10 years) who had not responded to topical treatment, were randomly assigned to oral ciclosporin (4 mg/kg daily) or methotrexate (0.4 mg/kg weekly) for 36 weeks and then followed for another 24 weeks off therapy for the co-primary outcomes of change in objective Scoring Atopic Dermatitis (o-SCORAD) at 12 weeks, as well as time to first significant flare after treatment cessation, defined as returning to baseline o-SCORAD, or restarting a systemic treatment.

Secondary outcomes included disease severity and quality of life (QOL) measures, as well as safety. At baseline, the mean o-SCORAD was 46.81, with mean Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI) and Patient Oriented Eczema Measure (POEM) scores of 28.05 and 20.62 respectively. The mean Children’s Dermatology Life Quality Index (CDLQI) score was 14.96.

Looking at change in eczema severity measured by o-SCORAD at 12 weeks, ciclosporin was superior to methotrexate, with a mean difference in o-SCORAD change of -5.69 (P =.01). For the co-primary endpoint of time to first significant flare during the 24 weeks after treatment cessation, “there was a trend toward more flare activity in the ciclosporin group, although with a hazard ratio of 1.55, this was statistically not significant,” Dr. Flohr said.

On a graph showing mean EASI scores from baseline through the 60-week study period, Dr. Flohr explained how the score first dropped more precipitously in patients treated with ciclosporin compared with those treated with methotrexate, reaching a statistically significant difference between the groups by 12 weeks (–3.13, P = .0145).

However, after that time, while the EASI score among those on methotrexate continued to drop, the ciclosporin score evened out, so that by 20 weeks, methotrexate EASI scores were better, and remained so until the end of treatment and further, out to 60 weeks (mean difference -6.36, P < .001). “The most interesting bit of this graph is [that] the curve is pointing downwards for methotrexate up to the 9-month point, suggesting these people had not reached their full therapeutic potential yet, whereas if you’re on ciclosporin you plateau and there’s not much additional improvement, if at all, and then people [on ciclosporin] start going up in their disease activity off therapy,” he said.

The same pattern was seen with all the other outcome measures, including o-SCORAD and POEM.

Quality of life significantly improved by about 8 points in both treatment groups, with no significant differences between groups, and this improvement was sustained through the 24 weeks following cessation of therapy. However, during this treatment-free phase, patients on methotrexate had fewer parent-reported flares compared with those on ciclosporin (mean 6.19 vs 5.40 flares, P =.0251), although there was no difference between groups in time to first flare.

Describing the treatment safety as “overall reassuring,” Dr. Flohr said there were slightly more nonserious adverse events in the methotrexate arm (407 vs. 369), with nausea occurring more often in this group (43.1% vs. 17.6%).

“I think we were seeing this clinically, but to see it in a clinical trial gives us more confidence in discussing with parents,” said session moderator Melinda Gooderham, MD, assistant professor at Queens University, Kingston, Ont., and medical director at the SKiN Centre for Dermatology in Peterborough.

What she also took away from the study was safety of these treatments. “The discontinuation rate was not different with either drug, so it’s not like ciclosporin works fast but all these people have problems and discontinue,” Dr. Gooderham told this news organization. “That’s also reassuring.”

Asked which treatment she prefers, Dr. Gooderham, a consultant physician at Peterborough Regional Health Centre, picked methotrexate “because of the lasting effect. But there are times when you may need more rapid control ... where I might choose ciclosporin first, but for me it’s maybe 90% methotrexate first, 10% ciclosporin.”

Dr. Flohr and Dr. Gooderham report no relevant financial relationships. The study was funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ISAD 2022

Access to abortion clinics declines sharply

Estimated travel time to abortion facilities in the United States has increased significantly since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, according to results from an original investigation published online in JAMA.

In the wake of the ruling, many clinics have closed and now 33.3% of females of reproductive age live more than an hour from an abortion facility, more than double the 14.6% who lived that far before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization court ruling, the paper states.

A 2022 study found that when people live 50 miles or more from an abortion facility they “were more likely to still be seeking an abortion on a 4-week follow-up than those who lived closer to an abortion facility,” wrote the authors, led by Benjamin Rader, MPH, from the Computational Epidemiology Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Of 1,134 abortion facilities in the United States, 749 were considered active before the ruling and 671 were considered active in a simulated post-Dobbs period.

More than 15 states have total or partial bans

The researchers accounted for the closure of abortion facilities in states with total bans or 6-week abortion bans, compared with the period before the ruling, “during which all facilities providing abortions in 2021 were considered active.” The authors noted that more than 15 states have such bans.

Researchers found median and mean travel times to abortion facilities were estimated to be 10.9 minutes (interquartile ratio, 4.3-32.4) and 27.8 (standard deviation, 42.0) minutes before the ruling and used a paired sample t test (P < .001) to estimate the increase to a median of 17.0 (IQR, 4.9-124.5) minutes and a mean 100.4 (SD, 161.5) minutes after the ruling.

The numbers “highlight the catastrophe in terms of where we are,” Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, professor, obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, said in an interview.

Behind those numbers, she said, are brick walls for people who can’t take off work to drive that far or can’t leave their responsibilities of care for dependents or don’t have a car or even a driver’s license. It also calculates only land travel (car or public transportation) and doesn’t capture the financial and logistical burdens for some to fly to other states.

Dr. Cansino serves on the board of the Society of Family Planning, which publishes #WeCount, a national reporting effort that attempts to capture the effect of the Dobbs decision on abortion access. In a report published Oct. 28, #WeCount stated the numbers show that since the decision, there were 5,270 fewer abortions in July and 5,400 fewer in August, for a total of 10,670 fewer people in the United States who had abortions in the 2 months.

For Dr. Cansino, the numbers are only one measure of the wider problem.

“If it affects one person, it’s really the spirit of the consequence,” she said. “It’s difficult to wrap your mind around these numbers but the bottom line is that someone other than the person experiencing this health issue is making a decision for them.

“You will see physicians leaving states,” she said, “because their hands are tied in giving care.”

Glimpse of future from Texas example

The experience of abortion restrictions in Texas, described in another original investigation published in JAMA, provides a window into what could happen as access to abortions continues to decrease.

Texas has banned abortions after detectable embryonic cardiac activity since Sept. 1, 2021. Researchers obtained data on 80,107 abortions performed between September 2020 and February 2022.

In the first month following implementation of the Texas law, SB-8, the number of abortions in Texas dropped by 50%, compared with September 2020, and many pregnant Texas residents traveled out of state for abortion care.

But out-of-state abortions didn’t fully offset the overall drop in facility-based abortions.

“This decrease in facility-based abortion care suggests that many Texas residents continued their pregnancies, traveled beyond a neighboring state, or self-managed their abortion,” the authors wrote.

Increased time comes with costs

Sarah W. Prager, MD, professor in obstetrics and gynecology at University of Washington, Seattle, and director of the family planning division, explained that the travel time has to be seen in addition to the time it takes to complete the procedure.

Depending on state law, an abortion may take more than one visit to a clinic, which may mean adding lodging costs and overnight hours, or taking time off work, or finding childcare.

“A typical time to be at a clinic is upwards of 6 hours,” Dr. Prager explained, including paperwork, counseling, consent, the procedure, and recovery. That time is growing as active clinics overbook with others closing, she noted.

“We already know that 75% of people getting abortions are economically burdened at baseline. Gas is super expensive so the farther they have to drive – if they have their own car – that’s going to be expensive,” she noted.

In Washington, she said, abortion access is centralized in the western part of the state and located primarily between Seattle and Olympia. Though Oregon to the south has some of the nation’s most supportive laws for abortion, the other surrounding states have restrictive laws.

People in Alaska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana all have restrictive access, she noted, so people seeking abortions from those states have long distances to drive to western Washington and Oregon.

“Even for people living in eastern Washington, they are sometimes driving hours to get abortion care,” she said. “We’re really looking at health care that is dictated by geography, not by evidence, medicine, or science.”

The study by Dr. White and colleagues was supported by grants from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation and Collaborative for Gender + Reproductive Equity, as well as a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. One coauthor reported receiving compensation from the University of Texas at Austin for providing data during the conduct of the study, as well as grants from Merck and Gynuity Health Projects and personal fees from Merck and Organon outside the submitted work; another reported being named plaintiff in the case Planned Parenthood of Montana v State of Montana, a lawsuit challenging abortion restrictions in that state. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Cansino and Dr. Prager reported no relevant financial relationships.

Estimated travel time to abortion facilities in the United States has increased significantly since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, according to results from an original investigation published online in JAMA.

In the wake of the ruling, many clinics have closed and now 33.3% of females of reproductive age live more than an hour from an abortion facility, more than double the 14.6% who lived that far before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization court ruling, the paper states.

A 2022 study found that when people live 50 miles or more from an abortion facility they “were more likely to still be seeking an abortion on a 4-week follow-up than those who lived closer to an abortion facility,” wrote the authors, led by Benjamin Rader, MPH, from the Computational Epidemiology Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Of 1,134 abortion facilities in the United States, 749 were considered active before the ruling and 671 were considered active in a simulated post-Dobbs period.

More than 15 states have total or partial bans

The researchers accounted for the closure of abortion facilities in states with total bans or 6-week abortion bans, compared with the period before the ruling, “during which all facilities providing abortions in 2021 were considered active.” The authors noted that more than 15 states have such bans.

Researchers found median and mean travel times to abortion facilities were estimated to be 10.9 minutes (interquartile ratio, 4.3-32.4) and 27.8 (standard deviation, 42.0) minutes before the ruling and used a paired sample t test (P < .001) to estimate the increase to a median of 17.0 (IQR, 4.9-124.5) minutes and a mean 100.4 (SD, 161.5) minutes after the ruling.

The numbers “highlight the catastrophe in terms of where we are,” Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, professor, obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, said in an interview.

Behind those numbers, she said, are brick walls for people who can’t take off work to drive that far or can’t leave their responsibilities of care for dependents or don’t have a car or even a driver’s license. It also calculates only land travel (car or public transportation) and doesn’t capture the financial and logistical burdens for some to fly to other states.

Dr. Cansino serves on the board of the Society of Family Planning, which publishes #WeCount, a national reporting effort that attempts to capture the effect of the Dobbs decision on abortion access. In a report published Oct. 28, #WeCount stated the numbers show that since the decision, there were 5,270 fewer abortions in July and 5,400 fewer in August, for a total of 10,670 fewer people in the United States who had abortions in the 2 months.

For Dr. Cansino, the numbers are only one measure of the wider problem.

“If it affects one person, it’s really the spirit of the consequence,” she said. “It’s difficult to wrap your mind around these numbers but the bottom line is that someone other than the person experiencing this health issue is making a decision for them.

“You will see physicians leaving states,” she said, “because their hands are tied in giving care.”

Glimpse of future from Texas example

The experience of abortion restrictions in Texas, described in another original investigation published in JAMA, provides a window into what could happen as access to abortions continues to decrease.

Texas has banned abortions after detectable embryonic cardiac activity since Sept. 1, 2021. Researchers obtained data on 80,107 abortions performed between September 2020 and February 2022.

In the first month following implementation of the Texas law, SB-8, the number of abortions in Texas dropped by 50%, compared with September 2020, and many pregnant Texas residents traveled out of state for abortion care.

But out-of-state abortions didn’t fully offset the overall drop in facility-based abortions.

“This decrease in facility-based abortion care suggests that many Texas residents continued their pregnancies, traveled beyond a neighboring state, or self-managed their abortion,” the authors wrote.

Increased time comes with costs

Sarah W. Prager, MD, professor in obstetrics and gynecology at University of Washington, Seattle, and director of the family planning division, explained that the travel time has to be seen in addition to the time it takes to complete the procedure.

Depending on state law, an abortion may take more than one visit to a clinic, which may mean adding lodging costs and overnight hours, or taking time off work, or finding childcare.

“A typical time to be at a clinic is upwards of 6 hours,” Dr. Prager explained, including paperwork, counseling, consent, the procedure, and recovery. That time is growing as active clinics overbook with others closing, she noted.

“We already know that 75% of people getting abortions are economically burdened at baseline. Gas is super expensive so the farther they have to drive – if they have their own car – that’s going to be expensive,” she noted.

In Washington, she said, abortion access is centralized in the western part of the state and located primarily between Seattle and Olympia. Though Oregon to the south has some of the nation’s most supportive laws for abortion, the other surrounding states have restrictive laws.

People in Alaska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana all have restrictive access, she noted, so people seeking abortions from those states have long distances to drive to western Washington and Oregon.

“Even for people living in eastern Washington, they are sometimes driving hours to get abortion care,” she said. “We’re really looking at health care that is dictated by geography, not by evidence, medicine, or science.”

The study by Dr. White and colleagues was supported by grants from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation and Collaborative for Gender + Reproductive Equity, as well as a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. One coauthor reported receiving compensation from the University of Texas at Austin for providing data during the conduct of the study, as well as grants from Merck and Gynuity Health Projects and personal fees from Merck and Organon outside the submitted work; another reported being named plaintiff in the case Planned Parenthood of Montana v State of Montana, a lawsuit challenging abortion restrictions in that state. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Cansino and Dr. Prager reported no relevant financial relationships.

Estimated travel time to abortion facilities in the United States has increased significantly since the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade, according to results from an original investigation published online in JAMA.

In the wake of the ruling, many clinics have closed and now 33.3% of females of reproductive age live more than an hour from an abortion facility, more than double the 14.6% who lived that far before the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization court ruling, the paper states.

A 2022 study found that when people live 50 miles or more from an abortion facility they “were more likely to still be seeking an abortion on a 4-week follow-up than those who lived closer to an abortion facility,” wrote the authors, led by Benjamin Rader, MPH, from the Computational Epidemiology Lab at Boston Children’s Hospital.

Of 1,134 abortion facilities in the United States, 749 were considered active before the ruling and 671 were considered active in a simulated post-Dobbs period.

More than 15 states have total or partial bans

The researchers accounted for the closure of abortion facilities in states with total bans or 6-week abortion bans, compared with the period before the ruling, “during which all facilities providing abortions in 2021 were considered active.” The authors noted that more than 15 states have such bans.

Researchers found median and mean travel times to abortion facilities were estimated to be 10.9 minutes (interquartile ratio, 4.3-32.4) and 27.8 (standard deviation, 42.0) minutes before the ruling and used a paired sample t test (P < .001) to estimate the increase to a median of 17.0 (IQR, 4.9-124.5) minutes and a mean 100.4 (SD, 161.5) minutes after the ruling.

The numbers “highlight the catastrophe in terms of where we are,” Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, professor, obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis, said in an interview.

Behind those numbers, she said, are brick walls for people who can’t take off work to drive that far or can’t leave their responsibilities of care for dependents or don’t have a car or even a driver’s license. It also calculates only land travel (car or public transportation) and doesn’t capture the financial and logistical burdens for some to fly to other states.

Dr. Cansino serves on the board of the Society of Family Planning, which publishes #WeCount, a national reporting effort that attempts to capture the effect of the Dobbs decision on abortion access. In a report published Oct. 28, #WeCount stated the numbers show that since the decision, there were 5,270 fewer abortions in July and 5,400 fewer in August, for a total of 10,670 fewer people in the United States who had abortions in the 2 months.

For Dr. Cansino, the numbers are only one measure of the wider problem.

“If it affects one person, it’s really the spirit of the consequence,” she said. “It’s difficult to wrap your mind around these numbers but the bottom line is that someone other than the person experiencing this health issue is making a decision for them.

“You will see physicians leaving states,” she said, “because their hands are tied in giving care.”

Glimpse of future from Texas example

The experience of abortion restrictions in Texas, described in another original investigation published in JAMA, provides a window into what could happen as access to abortions continues to decrease.

Texas has banned abortions after detectable embryonic cardiac activity since Sept. 1, 2021. Researchers obtained data on 80,107 abortions performed between September 2020 and February 2022.

In the first month following implementation of the Texas law, SB-8, the number of abortions in Texas dropped by 50%, compared with September 2020, and many pregnant Texas residents traveled out of state for abortion care.

But out-of-state abortions didn’t fully offset the overall drop in facility-based abortions.

“This decrease in facility-based abortion care suggests that many Texas residents continued their pregnancies, traveled beyond a neighboring state, or self-managed their abortion,” the authors wrote.

Increased time comes with costs

Sarah W. Prager, MD, professor in obstetrics and gynecology at University of Washington, Seattle, and director of the family planning division, explained that the travel time has to be seen in addition to the time it takes to complete the procedure.

Depending on state law, an abortion may take more than one visit to a clinic, which may mean adding lodging costs and overnight hours, or taking time off work, or finding childcare.

“A typical time to be at a clinic is upwards of 6 hours,” Dr. Prager explained, including paperwork, counseling, consent, the procedure, and recovery. That time is growing as active clinics overbook with others closing, she noted.

“We already know that 75% of people getting abortions are economically burdened at baseline. Gas is super expensive so the farther they have to drive – if they have their own car – that’s going to be expensive,” she noted.

In Washington, she said, abortion access is centralized in the western part of the state and located primarily between Seattle and Olympia. Though Oregon to the south has some of the nation’s most supportive laws for abortion, the other surrounding states have restrictive laws.

People in Alaska, Wyoming, Idaho, and Montana all have restrictive access, she noted, so people seeking abortions from those states have long distances to drive to western Washington and Oregon.

“Even for people living in eastern Washington, they are sometimes driving hours to get abortion care,” she said. “We’re really looking at health care that is dictated by geography, not by evidence, medicine, or science.”

The study by Dr. White and colleagues was supported by grants from the Susan Thompson Buffett Foundation and Collaborative for Gender + Reproductive Equity, as well as a center grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development awarded to the Population Research Center at the University of Texas at Austin. One coauthor reported receiving compensation from the University of Texas at Austin for providing data during the conduct of the study, as well as grants from Merck and Gynuity Health Projects and personal fees from Merck and Organon outside the submitted work; another reported being named plaintiff in the case Planned Parenthood of Montana v State of Montana, a lawsuit challenging abortion restrictions in that state. No other disclosures were reported. Dr. Cansino and Dr. Prager reported no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA

Online support tool improves AD self-management

MONTREAL – for up to 1 year, according to two randomized controlled trials presented at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

The intervention, directed either at parents of children with AD or young adults with AD, “is very low cost, evidence based, easily accessible, and free from possible commercial bias,” said investigator Kim Thomas, MD, professor of applied dermatology research and codirector of the Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, faculty of medicine & health sciences, University of Nottingham (England).

The main focus of the intervention, along with general education, is “getting control” of the condition with flare-control creams and “keeping control” with regular emollient use.

Efficacy of the intervention, available free online, was compared with “usual eczema care” in 340 parents of children with AD up to age 12 and 337 young patients with AD aged 13-25. Participants were randomized to the intervention plus usual care or usual care alone. The primary outcome was the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure(POEM) at 24 weeks, with a further measurement at 52 weeks.

In the parent group, about half were women and 83% were White, and the median age of their children was 4 years. About 50% of parents had a university degree, making them “possibly better educated than we might want our target audience for this type of intervention,” Dr. Thomas commented. Most of the children had moderate AD.

In the young patient group, the mean age was 19 years, more than three-quarters were female, 83% were White, and most had moderate AD.

At 24 weeks, both intervention groups had improved POEM scores, compared with controls, with a mean difference of 1.5 points in the parent group (P = .002) and 1.7 points in the young patient group (P = .04). “A small difference, but statistically significant and sustained,” Dr. Thomas said, adding that this difference was sustained up to 52 weeks.

In terms of mechanism of action, a secondary outcome looked at the concept of enablement, “which again, seemed to be improved in the intervention group, which suggests it’s something to do with being able to understand and cope with their disease better,” she said. The tool is targeted to “people who wouldn’t normally get to a dermatologist and certainly wouldn’t get access to group interventions.”

An additional aim of the intervention was “to provide a single, consistent message received from every point of contact that people might engage with ... [from] community doctors, pharmacists, dermatologists, and importantly, eczema charities all signposting [the intervention] and sharing a consistent message.”

While the intervention is free and available to patients anywhere, Dr. Thomas emphasized that it is tailored to the U.K. health care system. “If people would like to get in touch and help work with us to maybe adapt it slightly to make it more suitable for your own health care systems, that’s something we’d be very happy to look at with you.”

Asked for comment, Natalie Cunningham, MD, panel moderator, was lukewarm about the tool. “It can be a supplement, but you can never replace the one-on-one patient–health care provider interaction,” she told this news organization. “That could be provided by a nondermatologist and supplemented by an online component,” said Dr. Cunningham, from the Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children in Halifax, N.S.

“First-line treatment for eczema, no matter what kind of eczema, is topical steroids, and that is something that requires a lot of education – and something you want to do one on one in person because everyone comes to it with a different experience, baggage, or understanding,” she said. “We need to figure out what the barrier is so that you can do the right education.”

In addition, with systemic AD therapies currently approved for children, parents and young patients need to be able to advocate for specialist care to access these medications, she noted.

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Cunningham reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – for up to 1 year, according to two randomized controlled trials presented at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

The intervention, directed either at parents of children with AD or young adults with AD, “is very low cost, evidence based, easily accessible, and free from possible commercial bias,” said investigator Kim Thomas, MD, professor of applied dermatology research and codirector of the Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, faculty of medicine & health sciences, University of Nottingham (England).

The main focus of the intervention, along with general education, is “getting control” of the condition with flare-control creams and “keeping control” with regular emollient use.

Efficacy of the intervention, available free online, was compared with “usual eczema care” in 340 parents of children with AD up to age 12 and 337 young patients with AD aged 13-25. Participants were randomized to the intervention plus usual care or usual care alone. The primary outcome was the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure(POEM) at 24 weeks, with a further measurement at 52 weeks.

In the parent group, about half were women and 83% were White, and the median age of their children was 4 years. About 50% of parents had a university degree, making them “possibly better educated than we might want our target audience for this type of intervention,” Dr. Thomas commented. Most of the children had moderate AD.

In the young patient group, the mean age was 19 years, more than three-quarters were female, 83% were White, and most had moderate AD.

At 24 weeks, both intervention groups had improved POEM scores, compared with controls, with a mean difference of 1.5 points in the parent group (P = .002) and 1.7 points in the young patient group (P = .04). “A small difference, but statistically significant and sustained,” Dr. Thomas said, adding that this difference was sustained up to 52 weeks.

In terms of mechanism of action, a secondary outcome looked at the concept of enablement, “which again, seemed to be improved in the intervention group, which suggests it’s something to do with being able to understand and cope with their disease better,” she said. The tool is targeted to “people who wouldn’t normally get to a dermatologist and certainly wouldn’t get access to group interventions.”

An additional aim of the intervention was “to provide a single, consistent message received from every point of contact that people might engage with ... [from] community doctors, pharmacists, dermatologists, and importantly, eczema charities all signposting [the intervention] and sharing a consistent message.”

While the intervention is free and available to patients anywhere, Dr. Thomas emphasized that it is tailored to the U.K. health care system. “If people would like to get in touch and help work with us to maybe adapt it slightly to make it more suitable for your own health care systems, that’s something we’d be very happy to look at with you.”

Asked for comment, Natalie Cunningham, MD, panel moderator, was lukewarm about the tool. “It can be a supplement, but you can never replace the one-on-one patient–health care provider interaction,” she told this news organization. “That could be provided by a nondermatologist and supplemented by an online component,” said Dr. Cunningham, from the Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children in Halifax, N.S.

“First-line treatment for eczema, no matter what kind of eczema, is topical steroids, and that is something that requires a lot of education – and something you want to do one on one in person because everyone comes to it with a different experience, baggage, or understanding,” she said. “We need to figure out what the barrier is so that you can do the right education.”

In addition, with systemic AD therapies currently approved for children, parents and young patients need to be able to advocate for specialist care to access these medications, she noted.

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Cunningham reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

MONTREAL – for up to 1 year, according to two randomized controlled trials presented at the annual meeting of the International Society of Atopic Dermatitis.

The intervention, directed either at parents of children with AD or young adults with AD, “is very low cost, evidence based, easily accessible, and free from possible commercial bias,” said investigator Kim Thomas, MD, professor of applied dermatology research and codirector of the Centre of Evidence Based Dermatology, faculty of medicine & health sciences, University of Nottingham (England).

The main focus of the intervention, along with general education, is “getting control” of the condition with flare-control creams and “keeping control” with regular emollient use.

Efficacy of the intervention, available free online, was compared with “usual eczema care” in 340 parents of children with AD up to age 12 and 337 young patients with AD aged 13-25. Participants were randomized to the intervention plus usual care or usual care alone. The primary outcome was the Patient-Oriented Eczema Measure(POEM) at 24 weeks, with a further measurement at 52 weeks.

In the parent group, about half were women and 83% were White, and the median age of their children was 4 years. About 50% of parents had a university degree, making them “possibly better educated than we might want our target audience for this type of intervention,” Dr. Thomas commented. Most of the children had moderate AD.

In the young patient group, the mean age was 19 years, more than three-quarters were female, 83% were White, and most had moderate AD.

At 24 weeks, both intervention groups had improved POEM scores, compared with controls, with a mean difference of 1.5 points in the parent group (P = .002) and 1.7 points in the young patient group (P = .04). “A small difference, but statistically significant and sustained,” Dr. Thomas said, adding that this difference was sustained up to 52 weeks.

In terms of mechanism of action, a secondary outcome looked at the concept of enablement, “which again, seemed to be improved in the intervention group, which suggests it’s something to do with being able to understand and cope with their disease better,” she said. The tool is targeted to “people who wouldn’t normally get to a dermatologist and certainly wouldn’t get access to group interventions.”

An additional aim of the intervention was “to provide a single, consistent message received from every point of contact that people might engage with ... [from] community doctors, pharmacists, dermatologists, and importantly, eczema charities all signposting [the intervention] and sharing a consistent message.”

While the intervention is free and available to patients anywhere, Dr. Thomas emphasized that it is tailored to the U.K. health care system. “If people would like to get in touch and help work with us to maybe adapt it slightly to make it more suitable for your own health care systems, that’s something we’d be very happy to look at with you.”

Asked for comment, Natalie Cunningham, MD, panel moderator, was lukewarm about the tool. “It can be a supplement, but you can never replace the one-on-one patient–health care provider interaction,” she told this news organization. “That could be provided by a nondermatologist and supplemented by an online component,” said Dr. Cunningham, from the Izaak Walton Killam Hospital for Children in Halifax, N.S.

“First-line treatment for eczema, no matter what kind of eczema, is topical steroids, and that is something that requires a lot of education – and something you want to do one on one in person because everyone comes to it with a different experience, baggage, or understanding,” she said. “We need to figure out what the barrier is so that you can do the right education.”

In addition, with systemic AD therapies currently approved for children, parents and young patients need to be able to advocate for specialist care to access these medications, she noted.

Dr. Thomas and Dr. Cunningham reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

AT ISAD 2022

AHA 2022 to recapture in-person vibe but preserve global reach

That a bustling medical conference can have global reach as it unfolds is one of the COVID pandemic’s many lessons for science. Hybrid meetings such as the American Heart Association scientific sessions, getting underway Nov. 5 in Chicago and cyberspace, are one of its legacies.

The conference is set to recapture the magic of the in-person Scientific Sessions last experienced in Philadelphia in 2019. But planners are mindful of a special responsibility to younger clinicians and scientists who entered the field knowing only the virtual format and who may not know “what it’s like in a room when major science is presented or to present posters and have people come by for conversations,” Manesh R. Patel, MD, chair of the AHA 2022 Scientific Sessions program committee, told this news organization.

Still, the pandemic has underlined the value of live streaming for the great many who can’t attend in person, Dr. Patel said. At AHA 2022, virtual access doesn’t mean only late breaking and featured presentations; more than 70 full sessions will be streamed from Friday through Monday.

Overall, the conference has more than 800 sessions on the schedule, about a third are panels or invited lectures and two-thirds are original reports on the latest research. At the core of the research offerings, 78 studies and analyses are slated across 18 Late-Breaking Science (LBS) and Featured Science (FS) sessions from Saturday through Monday. At least 30 presentations and abstracts will enter the peer-reviewed literature right away with their simultaneous online publication, Dr. Patel said.

More a meet-and-greet than a presentation, the Puppy Snuggles Booth will make a return appearance in Chicago after earning rave reviews at the 2019 Sessions in Philadelphia. All are invited to take a breather from their schedules to pet, cuddle, and play with a passel of pups, all in need of homes and available for adoption. The experience’s favorable effect on blood pressure is almost guaranteed.

LBS and FS highlights

“It’s an amazing year for Late Breaking Science and Featured Science at the Scientific Sessions,” Dr. Patel said of the presentations selected for special attention after a rigorous review process. “We have science that is as broad and as deep as we’ve seen in years.”

Saturday’s two LBS sessions kick off the series with studies looking at agents long available in heart failure and hypertension but lacking solid supporting evidence, “pretty large randomized trials that are, we think, going to affect clinical practice as soon as they are presented,” Dr. Patel said.

They include TRANSFORM-HF, a comparison of the loop diuretics furosemide and torsemide in patients hospitalized with heart failure. And the Diuretic Comparison Project (DCP), with more than 13,000 patients with hypertension assigned to the diuretics chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide, “is going to immediately impact how people think about blood pressure management,” Dr. Patel said.

Other highlights in the hypertension arena include the CRHCP trial, the MB-BP study, the Rich Life Project, and the polypill efficacy and safety trial QUARTET-USA, all in Sunday’s LBS-4; and the FRESH, PRECISION, and BrigHTN trials, all in LBS-9 on Monday.

Other heart failure trials joining TRANSFORM-HF in the line-up include IRONMAN, which revisited IV iron therapy in iron-deficient patients, in LBS-2 on Saturday and, in FS-4 on Monday, BETA3LVH and STRONG-HF, the latter a timely randomized test of pre- and post-discharge biomarker-driven uptitration of guideline-directed heart failure meds.

STRONG-HF was halted early, the trial’s nonprofit sponsor announced only weeks ago, after patients following the intensive uptitration strategy versus usual care showed a reduced risk of death or heart failure readmission; few other details were given.

Several sessions will be devoted to a rare breed of randomized trial, one that tests the efficacy of traditional herbal meds or nonprescription supplements against proven medications. “These are going to get a lot of people’s interest, one can imagine, because they are on common questions that patients bring to the clinic every day,” Dr. Patel said.

Such studies include CTS-AMI, which explored the traditional Chinese herbal medicine tongxinluo in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, in LBS-3 on Sunday, and SPORT in Sunday’s LBS-5, a small randomized comparison of low-dose rosuvastatin, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, an omega-3 fish-oil supplement, a plant sterol, red yeast rice, and placebo for any effects on LDL-C levels.

Other novel approaches to dyslipidemia management are to be covered in RESPECT-EPA and OCEAN(a)-DOSE, both in LBS-5 on Sunday, and all five presentations in Monday’s FS-9, including ARCHES-2, SHASTA-2, FOURIER-OLE, and ORION-3.

The interplay of antiplatelets and coronary interventions will be explored in presentations called OPTION, in LBS-6 on Sunday, and HOST-EXAM and TWILIGHT, in FS-6 on Monday.

Coronary and peripheral-vascular interventions are center stage in reports on RAPCO in LBS-3 and BRIGHT-4 in LBS-6, both on Sunday, and BEST-CLI in LBS-7 and the After-80 Study in FS-6, both on Monday.

Several Monday reports will cover comorbidities and complications associated with COVID-19, including PREVENT-HD in LBS-7, and PANAMO, FERMIN, COVID-NET, and a secondary analysis of the DELIVER trial in FS-5.

Rebroadcasts for the Pacific Rim

The sessions will also feature several evening rebroadcasts of earlier LBS sessions that meeting planners scored highly for scientific merit and potential clinical impact but also for their “regional pull,” primarily for our colleagues in Asia, Dr. Patel said.

The first two LBS sessions presented live during the day in Chicago will be rebroadcast that evening as, for example, Sunday morning and afternoon fare in Tokyo and Singapore. And LBS-5 live Sunday afternoon will rebroadcast that night as a Monday mid-morning session in, say, Hong Kong or Seoul.

This year’s AHA meeting spans the range of cardiovascular care, from precision therapies, such as gene editing or specific drugs, to broad strategies that consider, for example, social determinants of health, Dr. Patel said. “I think people, when they leave the Scientific Sessions, will feel very engaged in the larger conversation about how you impact very common conditions globally.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

That a bustling medical conference can have global reach as it unfolds is one of the COVID pandemic’s many lessons for science. Hybrid meetings such as the American Heart Association scientific sessions, getting underway Nov. 5 in Chicago and cyberspace, are one of its legacies.

The conference is set to recapture the magic of the in-person Scientific Sessions last experienced in Philadelphia in 2019. But planners are mindful of a special responsibility to younger clinicians and scientists who entered the field knowing only the virtual format and who may not know “what it’s like in a room when major science is presented or to present posters and have people come by for conversations,” Manesh R. Patel, MD, chair of the AHA 2022 Scientific Sessions program committee, told this news organization.

Still, the pandemic has underlined the value of live streaming for the great many who can’t attend in person, Dr. Patel said. At AHA 2022, virtual access doesn’t mean only late breaking and featured presentations; more than 70 full sessions will be streamed from Friday through Monday.

Overall, the conference has more than 800 sessions on the schedule, about a third are panels or invited lectures and two-thirds are original reports on the latest research. At the core of the research offerings, 78 studies and analyses are slated across 18 Late-Breaking Science (LBS) and Featured Science (FS) sessions from Saturday through Monday. At least 30 presentations and abstracts will enter the peer-reviewed literature right away with their simultaneous online publication, Dr. Patel said.

More a meet-and-greet than a presentation, the Puppy Snuggles Booth will make a return appearance in Chicago after earning rave reviews at the 2019 Sessions in Philadelphia. All are invited to take a breather from their schedules to pet, cuddle, and play with a passel of pups, all in need of homes and available for adoption. The experience’s favorable effect on blood pressure is almost guaranteed.

LBS and FS highlights

“It’s an amazing year for Late Breaking Science and Featured Science at the Scientific Sessions,” Dr. Patel said of the presentations selected for special attention after a rigorous review process. “We have science that is as broad and as deep as we’ve seen in years.”

Saturday’s two LBS sessions kick off the series with studies looking at agents long available in heart failure and hypertension but lacking solid supporting evidence, “pretty large randomized trials that are, we think, going to affect clinical practice as soon as they are presented,” Dr. Patel said.

They include TRANSFORM-HF, a comparison of the loop diuretics furosemide and torsemide in patients hospitalized with heart failure. And the Diuretic Comparison Project (DCP), with more than 13,000 patients with hypertension assigned to the diuretics chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide, “is going to immediately impact how people think about blood pressure management,” Dr. Patel said.

Other highlights in the hypertension arena include the CRHCP trial, the MB-BP study, the Rich Life Project, and the polypill efficacy and safety trial QUARTET-USA, all in Sunday’s LBS-4; and the FRESH, PRECISION, and BrigHTN trials, all in LBS-9 on Monday.

Other heart failure trials joining TRANSFORM-HF in the line-up include IRONMAN, which revisited IV iron therapy in iron-deficient patients, in LBS-2 on Saturday and, in FS-4 on Monday, BETA3LVH and STRONG-HF, the latter a timely randomized test of pre- and post-discharge biomarker-driven uptitration of guideline-directed heart failure meds.

STRONG-HF was halted early, the trial’s nonprofit sponsor announced only weeks ago, after patients following the intensive uptitration strategy versus usual care showed a reduced risk of death or heart failure readmission; few other details were given.

Several sessions will be devoted to a rare breed of randomized trial, one that tests the efficacy of traditional herbal meds or nonprescription supplements against proven medications. “These are going to get a lot of people’s interest, one can imagine, because they are on common questions that patients bring to the clinic every day,” Dr. Patel said.

Such studies include CTS-AMI, which explored the traditional Chinese herbal medicine tongxinluo in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, in LBS-3 on Sunday, and SPORT in Sunday’s LBS-5, a small randomized comparison of low-dose rosuvastatin, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, an omega-3 fish-oil supplement, a plant sterol, red yeast rice, and placebo for any effects on LDL-C levels.

Other novel approaches to dyslipidemia management are to be covered in RESPECT-EPA and OCEAN(a)-DOSE, both in LBS-5 on Sunday, and all five presentations in Monday’s FS-9, including ARCHES-2, SHASTA-2, FOURIER-OLE, and ORION-3.

The interplay of antiplatelets and coronary interventions will be explored in presentations called OPTION, in LBS-6 on Sunday, and HOST-EXAM and TWILIGHT, in FS-6 on Monday.

Coronary and peripheral-vascular interventions are center stage in reports on RAPCO in LBS-3 and BRIGHT-4 in LBS-6, both on Sunday, and BEST-CLI in LBS-7 and the After-80 Study in FS-6, both on Monday.

Several Monday reports will cover comorbidities and complications associated with COVID-19, including PREVENT-HD in LBS-7, and PANAMO, FERMIN, COVID-NET, and a secondary analysis of the DELIVER trial in FS-5.

Rebroadcasts for the Pacific Rim

The sessions will also feature several evening rebroadcasts of earlier LBS sessions that meeting planners scored highly for scientific merit and potential clinical impact but also for their “regional pull,” primarily for our colleagues in Asia, Dr. Patel said.

The first two LBS sessions presented live during the day in Chicago will be rebroadcast that evening as, for example, Sunday morning and afternoon fare in Tokyo and Singapore. And LBS-5 live Sunday afternoon will rebroadcast that night as a Monday mid-morning session in, say, Hong Kong or Seoul.

This year’s AHA meeting spans the range of cardiovascular care, from precision therapies, such as gene editing or specific drugs, to broad strategies that consider, for example, social determinants of health, Dr. Patel said. “I think people, when they leave the Scientific Sessions, will feel very engaged in the larger conversation about how you impact very common conditions globally.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

That a bustling medical conference can have global reach as it unfolds is one of the COVID pandemic’s many lessons for science. Hybrid meetings such as the American Heart Association scientific sessions, getting underway Nov. 5 in Chicago and cyberspace, are one of its legacies.

The conference is set to recapture the magic of the in-person Scientific Sessions last experienced in Philadelphia in 2019. But planners are mindful of a special responsibility to younger clinicians and scientists who entered the field knowing only the virtual format and who may not know “what it’s like in a room when major science is presented or to present posters and have people come by for conversations,” Manesh R. Patel, MD, chair of the AHA 2022 Scientific Sessions program committee, told this news organization.

Still, the pandemic has underlined the value of live streaming for the great many who can’t attend in person, Dr. Patel said. At AHA 2022, virtual access doesn’t mean only late breaking and featured presentations; more than 70 full sessions will be streamed from Friday through Monday.

Overall, the conference has more than 800 sessions on the schedule, about a third are panels or invited lectures and two-thirds are original reports on the latest research. At the core of the research offerings, 78 studies and analyses are slated across 18 Late-Breaking Science (LBS) and Featured Science (FS) sessions from Saturday through Monday. At least 30 presentations and abstracts will enter the peer-reviewed literature right away with their simultaneous online publication, Dr. Patel said.

More a meet-and-greet than a presentation, the Puppy Snuggles Booth will make a return appearance in Chicago after earning rave reviews at the 2019 Sessions in Philadelphia. All are invited to take a breather from their schedules to pet, cuddle, and play with a passel of pups, all in need of homes and available for adoption. The experience’s favorable effect on blood pressure is almost guaranteed.

LBS and FS highlights

“It’s an amazing year for Late Breaking Science and Featured Science at the Scientific Sessions,” Dr. Patel said of the presentations selected for special attention after a rigorous review process. “We have science that is as broad and as deep as we’ve seen in years.”

Saturday’s two LBS sessions kick off the series with studies looking at agents long available in heart failure and hypertension but lacking solid supporting evidence, “pretty large randomized trials that are, we think, going to affect clinical practice as soon as they are presented,” Dr. Patel said.

They include TRANSFORM-HF, a comparison of the loop diuretics furosemide and torsemide in patients hospitalized with heart failure. And the Diuretic Comparison Project (DCP), with more than 13,000 patients with hypertension assigned to the diuretics chlorthalidone or hydrochlorothiazide, “is going to immediately impact how people think about blood pressure management,” Dr. Patel said.

Other highlights in the hypertension arena include the CRHCP trial, the MB-BP study, the Rich Life Project, and the polypill efficacy and safety trial QUARTET-USA, all in Sunday’s LBS-4; and the FRESH, PRECISION, and BrigHTN trials, all in LBS-9 on Monday.

Other heart failure trials joining TRANSFORM-HF in the line-up include IRONMAN, which revisited IV iron therapy in iron-deficient patients, in LBS-2 on Saturday and, in FS-4 on Monday, BETA3LVH and STRONG-HF, the latter a timely randomized test of pre- and post-discharge biomarker-driven uptitration of guideline-directed heart failure meds.

STRONG-HF was halted early, the trial’s nonprofit sponsor announced only weeks ago, after patients following the intensive uptitration strategy versus usual care showed a reduced risk of death or heart failure readmission; few other details were given.

Several sessions will be devoted to a rare breed of randomized trial, one that tests the efficacy of traditional herbal meds or nonprescription supplements against proven medications. “These are going to get a lot of people’s interest, one can imagine, because they are on common questions that patients bring to the clinic every day,” Dr. Patel said.

Such studies include CTS-AMI, which explored the traditional Chinese herbal medicine tongxinluo in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction, in LBS-3 on Sunday, and SPORT in Sunday’s LBS-5, a small randomized comparison of low-dose rosuvastatin, cinnamon, garlic, turmeric, an omega-3 fish-oil supplement, a plant sterol, red yeast rice, and placebo for any effects on LDL-C levels.

Other novel approaches to dyslipidemia management are to be covered in RESPECT-EPA and OCEAN(a)-DOSE, both in LBS-5 on Sunday, and all five presentations in Monday’s FS-9, including ARCHES-2, SHASTA-2, FOURIER-OLE, and ORION-3.

The interplay of antiplatelets and coronary interventions will be explored in presentations called OPTION, in LBS-6 on Sunday, and HOST-EXAM and TWILIGHT, in FS-6 on Monday.

Coronary and peripheral-vascular interventions are center stage in reports on RAPCO in LBS-3 and BRIGHT-4 in LBS-6, both on Sunday, and BEST-CLI in LBS-7 and the After-80 Study in FS-6, both on Monday.

Several Monday reports will cover comorbidities and complications associated with COVID-19, including PREVENT-HD in LBS-7, and PANAMO, FERMIN, COVID-NET, and a secondary analysis of the DELIVER trial in FS-5.

Rebroadcasts for the Pacific Rim

The sessions will also feature several evening rebroadcasts of earlier LBS sessions that meeting planners scored highly for scientific merit and potential clinical impact but also for their “regional pull,” primarily for our colleagues in Asia, Dr. Patel said.

The first two LBS sessions presented live during the day in Chicago will be rebroadcast that evening as, for example, Sunday morning and afternoon fare in Tokyo and Singapore. And LBS-5 live Sunday afternoon will rebroadcast that night as a Monday mid-morning session in, say, Hong Kong or Seoul.

This year’s AHA meeting spans the range of cardiovascular care, from precision therapies, such as gene editing or specific drugs, to broad strategies that consider, for example, social determinants of health, Dr. Patel said. “I think people, when they leave the Scientific Sessions, will feel very engaged in the larger conversation about how you impact very common conditions globally.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

European research team to study drug resistance in psychiatry

Having secured 11 million euros in funding from the European Union’s Horizon Health program, an international team of pharmacology, pharmacogenetics, and psychiatry experts has set to work in hopes of helping patients with severe mental illnesses.

On this team is a group of researchers from the University of Cagliari in Sardinia, Italy. They are part of a network of international experts from 26 universities, research centers, and European associations, all of whom have vast experience in the fields of psychiatry, pharmacology, genetics, and statistics. Coordinating the project is Bernhard T. Baune, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of Münster, Germany.

The problem of drug resistance is of great relevance to psychiatrists. About one-third of patients do not respond to pharmacologic therapies; as a result, their illness becomes more and more severe. This development has a major impact on these patients’ quality of life. In addition, health care and social services face a rise in the costs associated with managing the illnesses.

The research team from the University of Cagliari has two members from the department of biomedical sciences – Alessio Squassina, PhD, head of the pharmacogenetics laboratory, and Claudia Pisanu, MD, PhD – and two translational clinical researchers from the department of medical sciences and public health – Bernardo Carpiniello, MD, head of the psychiatry division, and Mirko Manchia, MD, PhD. They will be in charge of recruiting and collecting biological material from one set of patients with mental illnesses, collecting DNA and performing genetic screenings for all of the patients recruited by the network’s members in the various European countries, and conducting and coordinating clinical trials in which the pharmacologic therapies will be guided based on the molecular results.

“The process of figuring out whether someone has drug resistance is complex,” explained Dr. Squassina. “It may require very long periods of treatment and observation which, in the end, severely impact the patient’s chances of seeing a significant improvement in their symptoms and of being able to reintegrate themselves into society in the shortest possible time frame.” The goal of the Psych-STRATA project is to come up with a predictive algorithm – consisting of molecular markers and clinical data – that, before a specific antidepressant is even given, will be able to identify the patients who have a greater probability of responding and those who have a greater probability of not responding. Psych-STRATA’s findings could have a meaningful positive effect on the lives of patients with mental illnesses, as they would provide psychiatrists with guidance for managing pharmacologic therapies more precisely and in a way that is based on patients’ biological characteristics. This, in turn, would increase the efficacy of drugs, lower the risks of adverse effects, and significantly contribute to achieving quick remission of symptoms.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

Having secured 11 million euros in funding from the European Union’s Horizon Health program, an international team of pharmacology, pharmacogenetics, and psychiatry experts has set to work in hopes of helping patients with severe mental illnesses.

On this team is a group of researchers from the University of Cagliari in Sardinia, Italy. They are part of a network of international experts from 26 universities, research centers, and European associations, all of whom have vast experience in the fields of psychiatry, pharmacology, genetics, and statistics. Coordinating the project is Bernhard T. Baune, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of Münster, Germany.

The problem of drug resistance is of great relevance to psychiatrists. About one-third of patients do not respond to pharmacologic therapies; as a result, their illness becomes more and more severe. This development has a major impact on these patients’ quality of life. In addition, health care and social services face a rise in the costs associated with managing the illnesses.

The research team from the University of Cagliari has two members from the department of biomedical sciences – Alessio Squassina, PhD, head of the pharmacogenetics laboratory, and Claudia Pisanu, MD, PhD – and two translational clinical researchers from the department of medical sciences and public health – Bernardo Carpiniello, MD, head of the psychiatry division, and Mirko Manchia, MD, PhD. They will be in charge of recruiting and collecting biological material from one set of patients with mental illnesses, collecting DNA and performing genetic screenings for all of the patients recruited by the network’s members in the various European countries, and conducting and coordinating clinical trials in which the pharmacologic therapies will be guided based on the molecular results.

“The process of figuring out whether someone has drug resistance is complex,” explained Dr. Squassina. “It may require very long periods of treatment and observation which, in the end, severely impact the patient’s chances of seeing a significant improvement in their symptoms and of being able to reintegrate themselves into society in the shortest possible time frame.” The goal of the Psych-STRATA project is to come up with a predictive algorithm – consisting of molecular markers and clinical data – that, before a specific antidepressant is even given, will be able to identify the patients who have a greater probability of responding and those who have a greater probability of not responding. Psych-STRATA’s findings could have a meaningful positive effect on the lives of patients with mental illnesses, as they would provide psychiatrists with guidance for managing pharmacologic therapies more precisely and in a way that is based on patients’ biological characteristics. This, in turn, would increase the efficacy of drugs, lower the risks of adverse effects, and significantly contribute to achieving quick remission of symptoms.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

Having secured 11 million euros in funding from the European Union’s Horizon Health program, an international team of pharmacology, pharmacogenetics, and psychiatry experts has set to work in hopes of helping patients with severe mental illnesses.

On this team is a group of researchers from the University of Cagliari in Sardinia, Italy. They are part of a network of international experts from 26 universities, research centers, and European associations, all of whom have vast experience in the fields of psychiatry, pharmacology, genetics, and statistics. Coordinating the project is Bernhard T. Baune, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry at the University of Münster, Germany.

The problem of drug resistance is of great relevance to psychiatrists. About one-third of patients do not respond to pharmacologic therapies; as a result, their illness becomes more and more severe. This development has a major impact on these patients’ quality of life. In addition, health care and social services face a rise in the costs associated with managing the illnesses.

The research team from the University of Cagliari has two members from the department of biomedical sciences – Alessio Squassina, PhD, head of the pharmacogenetics laboratory, and Claudia Pisanu, MD, PhD – and two translational clinical researchers from the department of medical sciences and public health – Bernardo Carpiniello, MD, head of the psychiatry division, and Mirko Manchia, MD, PhD. They will be in charge of recruiting and collecting biological material from one set of patients with mental illnesses, collecting DNA and performing genetic screenings for all of the patients recruited by the network’s members in the various European countries, and conducting and coordinating clinical trials in which the pharmacologic therapies will be guided based on the molecular results.

“The process of figuring out whether someone has drug resistance is complex,” explained Dr. Squassina. “It may require very long periods of treatment and observation which, in the end, severely impact the patient’s chances of seeing a significant improvement in their symptoms and of being able to reintegrate themselves into society in the shortest possible time frame.” The goal of the Psych-STRATA project is to come up with a predictive algorithm – consisting of molecular markers and clinical data – that, before a specific antidepressant is even given, will be able to identify the patients who have a greater probability of responding and those who have a greater probability of not responding. Psych-STRATA’s findings could have a meaningful positive effect on the lives of patients with mental illnesses, as they would provide psychiatrists with guidance for managing pharmacologic therapies more precisely and in a way that is based on patients’ biological characteristics. This, in turn, would increase the efficacy of drugs, lower the risks of adverse effects, and significantly contribute to achieving quick remission of symptoms.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com. This article was translated from Univadis Italy.

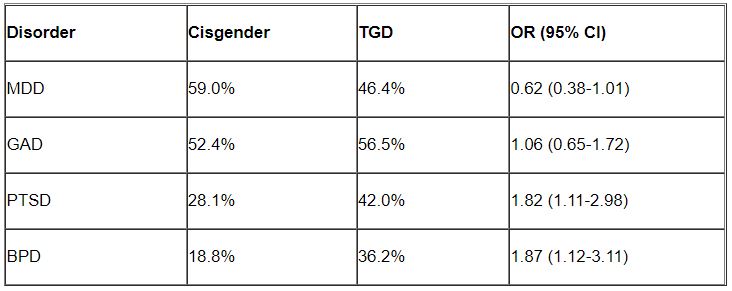

Higher rates of PTSD, BPD in transgender vs. cisgender psych patients

Although mood disorders, depression, and anxiety were the most common diagnoses in both TGD and cisgender patients, “when we compared the diagnostic profiles [of TGD patients] to those of cisgender patients, we found an increased prevalence of PTSD and BPD,” study investigator Mark Zimmerman, MD, professor of psychiatry and human behavior, Brown University, Providence, R.I., told this news organization.

“What we concluded is that psychiatric programs that wish to treat TGD patients should either have or should develop expertise in treating PTSD and BPD, not just mood and anxiety disorders,” Dr. Zimmerman said.

The study was published online September 26 in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Piecemeal literature’

TGD individuals “experience high rates of various forms of psychopathology in general and when compared with cisgender persons,” the investigators note.

They point out that most empirical evidence has relied upon the use of brief, unstructured psychodiagnostic assessment measures and assessment of a “limited constellation of psychiatric symptoms domains,” resulting in a “piecemeal literature wherein each piece of research documents elevations in one – or a few – diagnostic domains.”

Studies pointing to broader psychosocial health variables have often relied upon self-reported measures. In addition, in studies that utilized a structured interview approach, none “used a formal interview procedure to assess psychiatric diagnoses” and most focused only on a “limited number of psychiatric conditions based on self-reports of past diagnosis.”

The goal of the current study was to use semistructured interviews administered by professionals to compare the diagnostic profiles of a samples of TGD and cisgender patients who presented for treatment at a single naturalistic, clinically acute setting – a partial hospital program.