User login

Top pregnancy apps for your patients

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

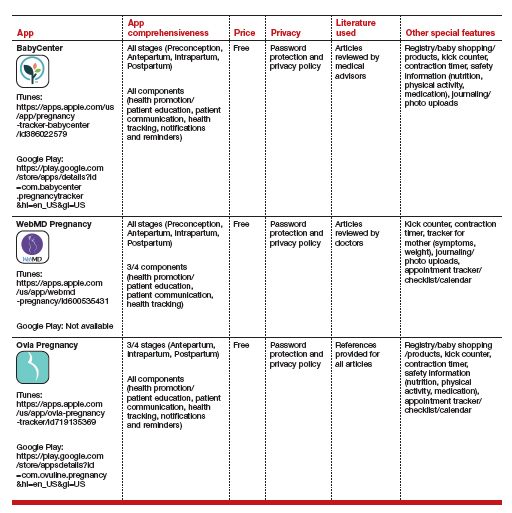

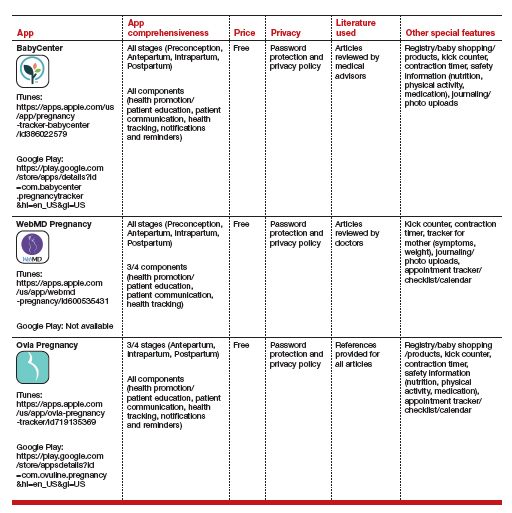

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

Pregnancy apps are more popular as patients use the internet to seek information about pregnancy and childbirth.1 Research has shown that over 50% of pregnant patients download apps focused on pregnancy, with an average of 3 being tried.2 This is especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, when patients seek information but may want to minimize clinical exposures. Other research has shown that women primarily use apps to monitor fetal development and to obtain information on nutrition and antenatal care.3

We identified apps and rated their contents and features.4 To identify the apps, we performed a Google search to mimic what a patient may do. We scored the identified apps based on what has been shown to make apps successful, as well as desired functions of the most commonly used apps. The quality of the applications was relatively varied, with many of the apps (60%) not having comprehensive information for every stage of pregnancy and no app attaining a perfect score. However, the top 3 apps had near perfect scores of 15/16 and 14/16, missing points only for having advertisements and requiring an internet connection.

The table details these top 3 recommended pregnancy apps, along with a detailed shortened version of the APPLICATIONS scoring system, APPLI (App comprehensiveness, Price, Platform, Literature Used, Other special features). We hope this column will help you feel comfortable in helping patients use pregnancy apps, should they ask for recommendations.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

1. Romano AM. A changing landscape: implications of pregnant women’s internet use for childbirth educators. J Perinat Educ. 2007;16:18-24. doi: 10.1624/105812407X244903.

2. Jayaseelan R, Pichandy C, Rushandramani D. Usage of smartphone apps by women on their maternal life. J Mass Communicat Journalism. 2015;29:05:158-164. doi: 10.4172/2165-7912.1000267.

3. Wang N, Deng Z, Wen LM, et al. Understanding the use of smartphone apps for health information among pregnant Chinese women: mixed methods study. JMIR mHealth uHealth. 2019;18:7:e12631. doi: 10.2196/12631.

4. Frid G, Bogaert K, Chen KT. Mobile health apps for pregnant women: systematic search, evaluation, and analysis of features. J Med Internet Res. 2021;18:23:e25667. doi: 10.2196/25667.

Models stratify hysterectomy risk with benign conditions

New models can help predict whether women having a hysterectomy for benign conditions are likely to have major complications, according to researchers.

The models, which use routinely collected data, are meant to aid surgeons in counseling women before surgery and help guide shared decision-making. The tools may lead to referrals for centers with greater surgical experience or may result in seeking nonsurgical treatment options, the researchers indicate.

The tools are not applicable to patients having hysterectomy for malignant disease.

Findings of the study, led by Krupa Madhvani, MD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, are published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Calculators complement surgeons’ intuition

“Our aim was to generate prediction models that can be used in conjunction with a surgeon’s intuition to enhance preoperative patient counseling and match the advances made in the technical aspects of surgery,” the authors write.

“Internal–external cross-validation and external validation showed moderate discrimination,” they note.

The study included 68,599 patients who had laparoscopic hysterectomies and 125,971 patients who had an abdominal hysterectomy, all English National Health System patients between 2011 and 2018.

Among their findings were that major complications occurred in 4.4% of laparoscopic and 4.9% of abdominal hysterectomies. Major complications in this study included ureteric, gastrointestinal, and vascular injury and wound complications.

Adhesions biggest predictors of complications

Adhesions were most predictive of complications – with double the odds – in both models (laparoscopic: odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.73-2.13; abdominal: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 2.27-2.66). That finding was consistent with previous literature.

“Adhesions should be suspected if there is a previous history of laparotomy, cesarean section, pelvic infection, or endometriosis, and can be reliably diagnosed preoperatively using ultrasonography,” the authors write. “As the global rate of cesarean sections continues to rise, this will undoubtedly remain a key determinant of major complications.”

Other factors that best predicted complications included adenomyosis in the laparoscopic model, and Asian ethnicity and diabetes in the abdominal model. Diabetes was not a predictive factor for complications in laparoscopic hysterectomy as it was in a previous study.

Obesity was not a significant predictor of major complications for either form of hysterectomy.

Factors protective against major complications included younger age and diagnosed menstrual disorders or benign adnexal mass (both models) and diagnosis of fibroids in the abdominal model.

Models miss surgeon experience

Jon Ivar Einarsson MD, PhD, MPH, founder of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s good to have these models to estimate risk as “there’s possibly a tendency to underestimate the risk by the surgeon.”

However, he told this publication that, though these models are based on a very large data set, the models are missing some key variables – often a problem with database studies – that are more indicative of complications. The most important factor missing, he said, is surgeon experience.

“We’ve shown in our publications that there’s a correlation between that and the risk of complications,“ Dr. Einarsson said.

Among other variables missing, he noted, are some that the authors list when acknowledging the limitations: severity of endometriosis and severity of adhesions.

He said his team wouldn’t use such models because they rely on their own data for gauging risk. He encourages other surgeons to track their own data and outcomes as well.

“I think the external validity here is nonexistent because we’re dealing with a different patient population in a different country with different surgeons [who] have various degrees of expertise,” Dr. Einarsson said.

“But if surgeons have not collected their own data, then this could be useful,” he said.

Links to online calculators

The online calculator can be found at www.evidencio.com (laparoscopic, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2551; abdominal, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2552).

The large, national multi-institutional database helps with generalizability of findings, the authors write. Additionally, patients had a unique identifier number so if patients were admitted to a different hospital after surgery, they were not lost to follow-up.

Limitations, in addition to those mentioned, include gaps in detailed clinical information, such as exact body mass index, and location, type, and size of leiomyoma, the authors write.

“Further research should focus on improving the discriminatory ability of these tools by including factors other than patient characteristics, including surgeon volume, as this has been shown to reduce complications,” they write.

Dr. Madhvani has received article-processing fees from Elly Charity (East London International Women’s Health Charity). No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Einarsson reports no relevant financial relationships. The acquisition of the data was funded by the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy. They were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. Coauthor Khalid Khan, MD is a distinguished investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Government of Spain.

New models can help predict whether women having a hysterectomy for benign conditions are likely to have major complications, according to researchers.

The models, which use routinely collected data, are meant to aid surgeons in counseling women before surgery and help guide shared decision-making. The tools may lead to referrals for centers with greater surgical experience or may result in seeking nonsurgical treatment options, the researchers indicate.

The tools are not applicable to patients having hysterectomy for malignant disease.

Findings of the study, led by Krupa Madhvani, MD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, are published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Calculators complement surgeons’ intuition

“Our aim was to generate prediction models that can be used in conjunction with a surgeon’s intuition to enhance preoperative patient counseling and match the advances made in the technical aspects of surgery,” the authors write.

“Internal–external cross-validation and external validation showed moderate discrimination,” they note.

The study included 68,599 patients who had laparoscopic hysterectomies and 125,971 patients who had an abdominal hysterectomy, all English National Health System patients between 2011 and 2018.

Among their findings were that major complications occurred in 4.4% of laparoscopic and 4.9% of abdominal hysterectomies. Major complications in this study included ureteric, gastrointestinal, and vascular injury and wound complications.

Adhesions biggest predictors of complications

Adhesions were most predictive of complications – with double the odds – in both models (laparoscopic: odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.73-2.13; abdominal: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 2.27-2.66). That finding was consistent with previous literature.

“Adhesions should be suspected if there is a previous history of laparotomy, cesarean section, pelvic infection, or endometriosis, and can be reliably diagnosed preoperatively using ultrasonography,” the authors write. “As the global rate of cesarean sections continues to rise, this will undoubtedly remain a key determinant of major complications.”

Other factors that best predicted complications included adenomyosis in the laparoscopic model, and Asian ethnicity and diabetes in the abdominal model. Diabetes was not a predictive factor for complications in laparoscopic hysterectomy as it was in a previous study.

Obesity was not a significant predictor of major complications for either form of hysterectomy.

Factors protective against major complications included younger age and diagnosed menstrual disorders or benign adnexal mass (both models) and diagnosis of fibroids in the abdominal model.

Models miss surgeon experience

Jon Ivar Einarsson MD, PhD, MPH, founder of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s good to have these models to estimate risk as “there’s possibly a tendency to underestimate the risk by the surgeon.”

However, he told this publication that, though these models are based on a very large data set, the models are missing some key variables – often a problem with database studies – that are more indicative of complications. The most important factor missing, he said, is surgeon experience.

“We’ve shown in our publications that there’s a correlation between that and the risk of complications,“ Dr. Einarsson said.

Among other variables missing, he noted, are some that the authors list when acknowledging the limitations: severity of endometriosis and severity of adhesions.

He said his team wouldn’t use such models because they rely on their own data for gauging risk. He encourages other surgeons to track their own data and outcomes as well.

“I think the external validity here is nonexistent because we’re dealing with a different patient population in a different country with different surgeons [who] have various degrees of expertise,” Dr. Einarsson said.

“But if surgeons have not collected their own data, then this could be useful,” he said.

Links to online calculators

The online calculator can be found at www.evidencio.com (laparoscopic, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2551; abdominal, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2552).

The large, national multi-institutional database helps with generalizability of findings, the authors write. Additionally, patients had a unique identifier number so if patients were admitted to a different hospital after surgery, they were not lost to follow-up.

Limitations, in addition to those mentioned, include gaps in detailed clinical information, such as exact body mass index, and location, type, and size of leiomyoma, the authors write.

“Further research should focus on improving the discriminatory ability of these tools by including factors other than patient characteristics, including surgeon volume, as this has been shown to reduce complications,” they write.

Dr. Madhvani has received article-processing fees from Elly Charity (East London International Women’s Health Charity). No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Einarsson reports no relevant financial relationships. The acquisition of the data was funded by the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy. They were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. Coauthor Khalid Khan, MD is a distinguished investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Government of Spain.

New models can help predict whether women having a hysterectomy for benign conditions are likely to have major complications, according to researchers.

The models, which use routinely collected data, are meant to aid surgeons in counseling women before surgery and help guide shared decision-making. The tools may lead to referrals for centers with greater surgical experience or may result in seeking nonsurgical treatment options, the researchers indicate.

The tools are not applicable to patients having hysterectomy for malignant disease.

Findings of the study, led by Krupa Madhvani, MD, of Barts and the London School of Medicine and Dentistry in London, are published online in the Canadian Medical Association Journal.

Calculators complement surgeons’ intuition

“Our aim was to generate prediction models that can be used in conjunction with a surgeon’s intuition to enhance preoperative patient counseling and match the advances made in the technical aspects of surgery,” the authors write.

“Internal–external cross-validation and external validation showed moderate discrimination,” they note.

The study included 68,599 patients who had laparoscopic hysterectomies and 125,971 patients who had an abdominal hysterectomy, all English National Health System patients between 2011 and 2018.

Among their findings were that major complications occurred in 4.4% of laparoscopic and 4.9% of abdominal hysterectomies. Major complications in this study included ureteric, gastrointestinal, and vascular injury and wound complications.

Adhesions biggest predictors of complications

Adhesions were most predictive of complications – with double the odds – in both models (laparoscopic: odds ratio, 1.92; 95% confidence interval, 1.73-2.13; abdominal: OR, 2.46; 95% CI, 2.27-2.66). That finding was consistent with previous literature.

“Adhesions should be suspected if there is a previous history of laparotomy, cesarean section, pelvic infection, or endometriosis, and can be reliably diagnosed preoperatively using ultrasonography,” the authors write. “As the global rate of cesarean sections continues to rise, this will undoubtedly remain a key determinant of major complications.”

Other factors that best predicted complications included adenomyosis in the laparoscopic model, and Asian ethnicity and diabetes in the abdominal model. Diabetes was not a predictive factor for complications in laparoscopic hysterectomy as it was in a previous study.

Obesity was not a significant predictor of major complications for either form of hysterectomy.

Factors protective against major complications included younger age and diagnosed menstrual disorders or benign adnexal mass (both models) and diagnosis of fibroids in the abdominal model.

Models miss surgeon experience

Jon Ivar Einarsson MD, PhD, MPH, founder of the division of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, said it’s good to have these models to estimate risk as “there’s possibly a tendency to underestimate the risk by the surgeon.”

However, he told this publication that, though these models are based on a very large data set, the models are missing some key variables – often a problem with database studies – that are more indicative of complications. The most important factor missing, he said, is surgeon experience.

“We’ve shown in our publications that there’s a correlation between that and the risk of complications,“ Dr. Einarsson said.

Among other variables missing, he noted, are some that the authors list when acknowledging the limitations: severity of endometriosis and severity of adhesions.

He said his team wouldn’t use such models because they rely on their own data for gauging risk. He encourages other surgeons to track their own data and outcomes as well.

“I think the external validity here is nonexistent because we’re dealing with a different patient population in a different country with different surgeons [who] have various degrees of expertise,” Dr. Einarsson said.

“But if surgeons have not collected their own data, then this could be useful,” he said.

Links to online calculators

The online calculator can be found at www.evidencio.com (laparoscopic, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2551; abdominal, www.evidencio.com/models/show/2552).

The large, national multi-institutional database helps with generalizability of findings, the authors write. Additionally, patients had a unique identifier number so if patients were admitted to a different hospital after surgery, they were not lost to follow-up.

Limitations, in addition to those mentioned, include gaps in detailed clinical information, such as exact body mass index, and location, type, and size of leiomyoma, the authors write.

“Further research should focus on improving the discriminatory ability of these tools by including factors other than patient characteristics, including surgeon volume, as this has been shown to reduce complications,” they write.

Dr. Madhvani has received article-processing fees from Elly Charity (East London International Women’s Health Charity). No other competing interests were declared. Dr. Einarsson reports no relevant financial relationships. The acquisition of the data was funded by the British Society for Gynaecological Endoscopy. They were not involved in the study design, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of the report, or the decision to submit the article for publication. Coauthor Khalid Khan, MD is a distinguished investigator funded by the Beatriz Galindo Program grant given to the University of Granada by the Ministry of Science, Innovation, and Universities of the Government of Spain.

FROM CANADIAN MEDICAL ASSOCIATION JOURNAL

Then and now: Endoscopy

In the second issue of GI & Hepatology News in February 2007, an article reviewed the disruptive forces to colonoscopy including CT colonography and the colon capsule. The article stated that “colonoscopy is still the preferred method, but the emerging technology could catch up in 3-5 years.”

While this prediction did not come to pass, the field of endoscopy has evolved in remarkable ways over the last 15 years. From the development of high-definition endoscopes to the transformation of interventional endoscopy to include “third space” procedures, previously unimaginable techniques have now become commonplace. This transformation has changed the nature and training of our field and, even more importantly, dramatically improved the care of our patients.

Just as notably, the regulatory and practice environment for endoscopy has also changed in the last 15 years, albeit at a slower pace. In January of 2007, as the first issue of GI & Hepatology News came out, Medicare announced that it would cover all screening procedures without a copay but left a loophole that charged patients if their screening colonoscopy became therapeutic. That loophole was finally fixed this year as GI & Hepatology News celebrates its 15-year anniversary.

If the past 15 years are any indication, endoscopy practice will continue to change at a humbling pace over the next 15 years. I look forward to seeing those changes unfold through the pages of GI & Hepatology News.

Dr. Gellad is associate professor of medicine and associate vice chair of ambulatory services at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. He is also a staff physician with the Durham VA Health Care system. He disclosed ties with Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Higgs Boson Health.

In the second issue of GI & Hepatology News in February 2007, an article reviewed the disruptive forces to colonoscopy including CT colonography and the colon capsule. The article stated that “colonoscopy is still the preferred method, but the emerging technology could catch up in 3-5 years.”

While this prediction did not come to pass, the field of endoscopy has evolved in remarkable ways over the last 15 years. From the development of high-definition endoscopes to the transformation of interventional endoscopy to include “third space” procedures, previously unimaginable techniques have now become commonplace. This transformation has changed the nature and training of our field and, even more importantly, dramatically improved the care of our patients.

Just as notably, the regulatory and practice environment for endoscopy has also changed in the last 15 years, albeit at a slower pace. In January of 2007, as the first issue of GI & Hepatology News came out, Medicare announced that it would cover all screening procedures without a copay but left a loophole that charged patients if their screening colonoscopy became therapeutic. That loophole was finally fixed this year as GI & Hepatology News celebrates its 15-year anniversary.

If the past 15 years are any indication, endoscopy practice will continue to change at a humbling pace over the next 15 years. I look forward to seeing those changes unfold through the pages of GI & Hepatology News.

Dr. Gellad is associate professor of medicine and associate vice chair of ambulatory services at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. He is also a staff physician with the Durham VA Health Care system. He disclosed ties with Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Higgs Boson Health.

In the second issue of GI & Hepatology News in February 2007, an article reviewed the disruptive forces to colonoscopy including CT colonography and the colon capsule. The article stated that “colonoscopy is still the preferred method, but the emerging technology could catch up in 3-5 years.”

While this prediction did not come to pass, the field of endoscopy has evolved in remarkable ways over the last 15 years. From the development of high-definition endoscopes to the transformation of interventional endoscopy to include “third space” procedures, previously unimaginable techniques have now become commonplace. This transformation has changed the nature and training of our field and, even more importantly, dramatically improved the care of our patients.

Just as notably, the regulatory and practice environment for endoscopy has also changed in the last 15 years, albeit at a slower pace. In January of 2007, as the first issue of GI & Hepatology News came out, Medicare announced that it would cover all screening procedures without a copay but left a loophole that charged patients if their screening colonoscopy became therapeutic. That loophole was finally fixed this year as GI & Hepatology News celebrates its 15-year anniversary.

If the past 15 years are any indication, endoscopy practice will continue to change at a humbling pace over the next 15 years. I look forward to seeing those changes unfold through the pages of GI & Hepatology News.

Dr. Gellad is associate professor of medicine and associate vice chair of ambulatory services at Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C. He is also a staff physician with the Durham VA Health Care system. He disclosed ties with Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Higgs Boson Health.

Passing the ‘baton’ with pride

I was honored to be the third Editor-in-Chief of GIHN, from 2016 through 2021. GIHN is the official newspaper of the American Gastroenterological Association and has the widest readership of any AGA publication and is one that readers told us they read cover to cover. As such, each EIC and their Board of Editors must ensure balanced content that holds the interest of a diverse readership. I was privileged to work with a talented editorial board who reviewed articles, attended leadership meetings, and offered terrific suggestions throughout our tenure. I treasured their support and friendship.

Within each of the 60 monthly issues, we sought to highlight science, practice operations, national trends, and opinions and reviews that would be most important to basic scientists, clinical researchers, and academic and community clinicians, primarily from the United States but also from a worldwide readership. I was given a 300-word section to create editorial comments on pertinent topics that were important to gastroenterologists. Having a background in both community and academic practice, I tried to bring a balanced perspective to areas that often seem worlds apart.

The period between 2016 and 2021 also was a time of political upheaval in this country – something we could not ignore. I attempted to write about current events in a balanced way that kept a focus on patients and AGA’s core constituency. Not always an easy task. Sustainability of the Affordable Care Act was very much in question because of judicial and legislative challenges; had the ACA been overturned, our practices would be very different now.

In 2016, the first private equity–backed practice platform was created in south Florida. Little did we know how much that model would change community practice. Then, on Jan. 21, 2020, the first case of COVID 19 was diagnosed in Seattle (although earlier cases likely occurred). By March, many clinics and practices were closing, and we were altering our care delivery infrastructure in ways that would forever change practice. Trying to keep current with ever-changing science and policies was a challenge.

I will always treasure my time as EIC. I was happy (and proud) to pass this baton to Megan A. Adams MD, JD, MSc, my colleague and mentee at the University of Michigan. The partnership between AGA and Frontline Medical Communications has been successful for 15 years and will continue to be so.

Dr. Allen, now retired, was professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is secretary/treasurer for the American Gastroenterological Association, and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

I was honored to be the third Editor-in-Chief of GIHN, from 2016 through 2021. GIHN is the official newspaper of the American Gastroenterological Association and has the widest readership of any AGA publication and is one that readers told us they read cover to cover. As such, each EIC and their Board of Editors must ensure balanced content that holds the interest of a diverse readership. I was privileged to work with a talented editorial board who reviewed articles, attended leadership meetings, and offered terrific suggestions throughout our tenure. I treasured their support and friendship.

Within each of the 60 monthly issues, we sought to highlight science, practice operations, national trends, and opinions and reviews that would be most important to basic scientists, clinical researchers, and academic and community clinicians, primarily from the United States but also from a worldwide readership. I was given a 300-word section to create editorial comments on pertinent topics that were important to gastroenterologists. Having a background in both community and academic practice, I tried to bring a balanced perspective to areas that often seem worlds apart.

The period between 2016 and 2021 also was a time of political upheaval in this country – something we could not ignore. I attempted to write about current events in a balanced way that kept a focus on patients and AGA’s core constituency. Not always an easy task. Sustainability of the Affordable Care Act was very much in question because of judicial and legislative challenges; had the ACA been overturned, our practices would be very different now.

In 2016, the first private equity–backed practice platform was created in south Florida. Little did we know how much that model would change community practice. Then, on Jan. 21, 2020, the first case of COVID 19 was diagnosed in Seattle (although earlier cases likely occurred). By March, many clinics and practices were closing, and we were altering our care delivery infrastructure in ways that would forever change practice. Trying to keep current with ever-changing science and policies was a challenge.

I will always treasure my time as EIC. I was happy (and proud) to pass this baton to Megan A. Adams MD, JD, MSc, my colleague and mentee at the University of Michigan. The partnership between AGA and Frontline Medical Communications has been successful for 15 years and will continue to be so.

Dr. Allen, now retired, was professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is secretary/treasurer for the American Gastroenterological Association, and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

I was honored to be the third Editor-in-Chief of GIHN, from 2016 through 2021. GIHN is the official newspaper of the American Gastroenterological Association and has the widest readership of any AGA publication and is one that readers told us they read cover to cover. As such, each EIC and their Board of Editors must ensure balanced content that holds the interest of a diverse readership. I was privileged to work with a talented editorial board who reviewed articles, attended leadership meetings, and offered terrific suggestions throughout our tenure. I treasured their support and friendship.

Within each of the 60 monthly issues, we sought to highlight science, practice operations, national trends, and opinions and reviews that would be most important to basic scientists, clinical researchers, and academic and community clinicians, primarily from the United States but also from a worldwide readership. I was given a 300-word section to create editorial comments on pertinent topics that were important to gastroenterologists. Having a background in both community and academic practice, I tried to bring a balanced perspective to areas that often seem worlds apart.

The period between 2016 and 2021 also was a time of political upheaval in this country – something we could not ignore. I attempted to write about current events in a balanced way that kept a focus on patients and AGA’s core constituency. Not always an easy task. Sustainability of the Affordable Care Act was very much in question because of judicial and legislative challenges; had the ACA been overturned, our practices would be very different now.

In 2016, the first private equity–backed practice platform was created in south Florida. Little did we know how much that model would change community practice. Then, on Jan. 21, 2020, the first case of COVID 19 was diagnosed in Seattle (although earlier cases likely occurred). By March, many clinics and practices were closing, and we were altering our care delivery infrastructure in ways that would forever change practice. Trying to keep current with ever-changing science and policies was a challenge.

I will always treasure my time as EIC. I was happy (and proud) to pass this baton to Megan A. Adams MD, JD, MSc, my colleague and mentee at the University of Michigan. The partnership between AGA and Frontline Medical Communications has been successful for 15 years and will continue to be so.

Dr. Allen, now retired, was professor of medicine at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. He is secretary/treasurer for the American Gastroenterological Association, and declares no relevant conflicts of interest.

Commentary: Biomarkers and Chemotherapy in Gastric Cancer, October 2022

Immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy are part of standard treatment for patients with advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. However, not all patients benefit from immunotherapy addition. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression has emerged as a useful, yet imperfect, biomarker for identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from the addition of immunotherapy. There is a need to better identify patients with higher chances of responding to these therapies, as well as a need to augment the activity that we are seeing with current approaches. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) has been previously identified as a predictive biomarker of response to immunotherapy. It is not widely used in clinical practice when treating patients with upper gastrointestinal cancers though, and it has not been extensively evaluated in this disease.

The study by Lee and colleagues evaluated the association between TMB and pembrolizumab response in patients treated in the phase 3 KEYNOTE-62 study. This was a prespecified exploratory analysis, which included 306 of 763 patients, based on TMB data availability. Although there was association between high TMB (cut-off defined as 10 mut/Mb), the benefit from pembrolizumab was most pronounced in patients with microsatellite-unstable tumors. When the analysis was limited to microsatellite-stable tumors with high TMB, the signal was attenuated and was only detected when immunotherapy was combined with chemotherapy.

Ultimately, although TMB is a predictive biomarker of response to immunotherapy, it is unlikely to significantly alter our approach to treatment of upper gastrointestinal cancers, especially when PD-L1 testing and microsatellite testing are more readily available and do not require more time- and resource-consuming next-generation sequencing when selecting first-line treatments.

Perioperative chemotherapy plays a critical role in the management of patients with early-stage gastric cancer. In the United States, perioperative FLOT (5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel) chemotherapy is the standard approach to this disease, with four cycles administered before and four cycles administered after resection.

In Korea, adjuvant chemotherapy is typically used, with 1 year of S-1 chemotherapy or 6 months of CAPOX (capecitabine/oxaliplatin) chemotherapy used most frequently. Kim and colleagues analyzed whether a shorter duration of chemotherapy (either S-1 or CAPOX) had similar outcomes. In a retrospective analysis of 20,552 patients, which included 13,614 patients who received S-1 and 6938 patients who received CAPOX, overall survival was worse in those patients who received a shorter duration of adjuvant treatment. Although this study is not directly applicable to how we approach treatment of early-stage gastric cancer in the United States, it does suggest that any modification in the duration of perioperative chemotherapy should be evaluated in prospective clinical trials, similarly to recent investigations regarding the duration on adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy are part of standard treatment for patients with advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. However, not all patients benefit from immunotherapy addition. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression has emerged as a useful, yet imperfect, biomarker for identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from the addition of immunotherapy. There is a need to better identify patients with higher chances of responding to these therapies, as well as a need to augment the activity that we are seeing with current approaches. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) has been previously identified as a predictive biomarker of response to immunotherapy. It is not widely used in clinical practice when treating patients with upper gastrointestinal cancers though, and it has not been extensively evaluated in this disease.

The study by Lee and colleagues evaluated the association between TMB and pembrolizumab response in patients treated in the phase 3 KEYNOTE-62 study. This was a prespecified exploratory analysis, which included 306 of 763 patients, based on TMB data availability. Although there was association between high TMB (cut-off defined as 10 mut/Mb), the benefit from pembrolizumab was most pronounced in patients with microsatellite-unstable tumors. When the analysis was limited to microsatellite-stable tumors with high TMB, the signal was attenuated and was only detected when immunotherapy was combined with chemotherapy.

Ultimately, although TMB is a predictive biomarker of response to immunotherapy, it is unlikely to significantly alter our approach to treatment of upper gastrointestinal cancers, especially when PD-L1 testing and microsatellite testing are more readily available and do not require more time- and resource-consuming next-generation sequencing when selecting first-line treatments.

Perioperative chemotherapy plays a critical role in the management of patients with early-stage gastric cancer. In the United States, perioperative FLOT (5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel) chemotherapy is the standard approach to this disease, with four cycles administered before and four cycles administered after resection.

In Korea, adjuvant chemotherapy is typically used, with 1 year of S-1 chemotherapy or 6 months of CAPOX (capecitabine/oxaliplatin) chemotherapy used most frequently. Kim and colleagues analyzed whether a shorter duration of chemotherapy (either S-1 or CAPOX) had similar outcomes. In a retrospective analysis of 20,552 patients, which included 13,614 patients who received S-1 and 6938 patients who received CAPOX, overall survival was worse in those patients who received a shorter duration of adjuvant treatment. Although this study is not directly applicable to how we approach treatment of early-stage gastric cancer in the United States, it does suggest that any modification in the duration of perioperative chemotherapy should be evaluated in prospective clinical trials, similarly to recent investigations regarding the duration on adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors in combination with chemotherapy are part of standard treatment for patients with advanced gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. However, not all patients benefit from immunotherapy addition. Programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression has emerged as a useful, yet imperfect, biomarker for identifying patients who are most likely to benefit from the addition of immunotherapy. There is a need to better identify patients with higher chances of responding to these therapies, as well as a need to augment the activity that we are seeing with current approaches. Tumor mutational burden (TMB) has been previously identified as a predictive biomarker of response to immunotherapy. It is not widely used in clinical practice when treating patients with upper gastrointestinal cancers though, and it has not been extensively evaluated in this disease.

The study by Lee and colleagues evaluated the association between TMB and pembrolizumab response in patients treated in the phase 3 KEYNOTE-62 study. This was a prespecified exploratory analysis, which included 306 of 763 patients, based on TMB data availability. Although there was association between high TMB (cut-off defined as 10 mut/Mb), the benefit from pembrolizumab was most pronounced in patients with microsatellite-unstable tumors. When the analysis was limited to microsatellite-stable tumors with high TMB, the signal was attenuated and was only detected when immunotherapy was combined with chemotherapy.

Ultimately, although TMB is a predictive biomarker of response to immunotherapy, it is unlikely to significantly alter our approach to treatment of upper gastrointestinal cancers, especially when PD-L1 testing and microsatellite testing are more readily available and do not require more time- and resource-consuming next-generation sequencing when selecting first-line treatments.

Perioperative chemotherapy plays a critical role in the management of patients with early-stage gastric cancer. In the United States, perioperative FLOT (5-fluorouracil, oxaliplatin, and docetaxel) chemotherapy is the standard approach to this disease, with four cycles administered before and four cycles administered after resection.

In Korea, adjuvant chemotherapy is typically used, with 1 year of S-1 chemotherapy or 6 months of CAPOX (capecitabine/oxaliplatin) chemotherapy used most frequently. Kim and colleagues analyzed whether a shorter duration of chemotherapy (either S-1 or CAPOX) had similar outcomes. In a retrospective analysis of 20,552 patients, which included 13,614 patients who received S-1 and 6938 patients who received CAPOX, overall survival was worse in those patients who received a shorter duration of adjuvant treatment. Although this study is not directly applicable to how we approach treatment of early-stage gastric cancer in the United States, it does suggest that any modification in the duration of perioperative chemotherapy should be evaluated in prospective clinical trials, similarly to recent investigations regarding the duration on adjuvant chemotherapy in colon cancer.

Drug combo holds promise of better AML outcomes

Adding venetoclax (Venclexta) to a gilteritinib (Xospata) regimen appeared to improve outcomes in refractory/relapsed FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a new industry-funded phase 1b study reported.

“.

Outcomes in AML are poor. As the study notes, most patients relapse and face a median overall survival of 4-7 months even with standard chemotherapy. Gilteritinib, a selective oral FLT3 inhibitor, is Food and Drug Administration–approved for the 30% of relapsed/refractory patients with AML who have FLT3 mutations.

“The general sentiment is that, although some patients have great benefit from gilteritinib monotherapy, there is room to improve the quality, frequency, and duration of responses with combinations,” said hematologist Andrew Brunner, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, in an interview. He was not involved with the study research.

For the new open-label, dose-escalation/dose-expansion study, led by hematologist Naval Daver, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, researchers enrolled 61 patients (56 with FLT3 mutations) from 2018 to 2020. The median age was 63 years (range 21-85).

The subjects were assigned to get a recommended phase 2 dose of 400 mg venetoclax once daily and 120 mg gilteritinib once daily.

Over a median follow-up of 17.5 months, the median remission time was 4.9 months (95% confidence interval, 3.4-6.6), and the patients with FLT3 mutations survived a median of 10 months.

“The combination of venetoclax and gilteritinib was tolerable at standard doses of each drug, generated remarkably high response rates, and markedly reduced FLT3-internal tandem duplications mutation burden. … Early mortality was similar to gilteritinib monotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Eighty percent of patients experienced cytopenias, and “adverse events prompted venetoclax and gilteritinib dose interruptions in 51% and 48%, respectively.”

About 60% of patients who went on to receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were alive at the end of follow-up, “suggesting that VenGilt [the combo treatment] could be an effective bridge to transplant in young/fit patients with relapsed FLT3mut AML,” the researchers wrote.

All patients withdrew from the study by November 2021 for several reasons such as death (n=42), adverse events (n=10), and disease progression (29); some had multiple reasons.

Dr. Brunner said the study is “an important step toward evaluating a new potential regimen.”

The remission duration, FLT3 molecular response, and median overall survival “seem quite encouraging for a severe disease like AML in relapse,” he said. However, he added that the drug combo “would need to be evaluated in a randomized and, ideally, placebo-controlled setting to know if this is a significant improvement.”

He also highlighted the high number of severe cyptopenias with associated complications such as death. “Whether this is acceptable depends on the patient and circumstances,” he said. “But it does suggest that this regimen would potentially be for more robust patients, particularly since the group that did best were those who went to transplant later.”

Pending more research, Dr. Brunner said, “I am not sure I would use [the combination treatment] over gilteritinib monotherapy, for instance. But there may be settings where no other options are available, and this could be considered, particularly if a transplant option is a next step.”

The study was funded by AbbVie, Genentech, and Astellas. The study authors report multiple disclosures; some are employed by Astellas, AbbVie, and Genentech/Roche.

Dr. Bronner reports running clinical trials, advisory board service and/or consultation for Acceleron, Agios, Abbvie, BMS/Celgene, Keros Therapeutics, Novartis, Takeda, GSK, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Gilead.

Adding venetoclax (Venclexta) to a gilteritinib (Xospata) regimen appeared to improve outcomes in refractory/relapsed FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a new industry-funded phase 1b study reported.

“.

Outcomes in AML are poor. As the study notes, most patients relapse and face a median overall survival of 4-7 months even with standard chemotherapy. Gilteritinib, a selective oral FLT3 inhibitor, is Food and Drug Administration–approved for the 30% of relapsed/refractory patients with AML who have FLT3 mutations.

“The general sentiment is that, although some patients have great benefit from gilteritinib monotherapy, there is room to improve the quality, frequency, and duration of responses with combinations,” said hematologist Andrew Brunner, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, in an interview. He was not involved with the study research.

For the new open-label, dose-escalation/dose-expansion study, led by hematologist Naval Daver, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, researchers enrolled 61 patients (56 with FLT3 mutations) from 2018 to 2020. The median age was 63 years (range 21-85).

The subjects were assigned to get a recommended phase 2 dose of 400 mg venetoclax once daily and 120 mg gilteritinib once daily.

Over a median follow-up of 17.5 months, the median remission time was 4.9 months (95% confidence interval, 3.4-6.6), and the patients with FLT3 mutations survived a median of 10 months.

“The combination of venetoclax and gilteritinib was tolerable at standard doses of each drug, generated remarkably high response rates, and markedly reduced FLT3-internal tandem duplications mutation burden. … Early mortality was similar to gilteritinib monotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Eighty percent of patients experienced cytopenias, and “adverse events prompted venetoclax and gilteritinib dose interruptions in 51% and 48%, respectively.”

About 60% of patients who went on to receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were alive at the end of follow-up, “suggesting that VenGilt [the combo treatment] could be an effective bridge to transplant in young/fit patients with relapsed FLT3mut AML,” the researchers wrote.

All patients withdrew from the study by November 2021 for several reasons such as death (n=42), adverse events (n=10), and disease progression (29); some had multiple reasons.

Dr. Brunner said the study is “an important step toward evaluating a new potential regimen.”

The remission duration, FLT3 molecular response, and median overall survival “seem quite encouraging for a severe disease like AML in relapse,” he said. However, he added that the drug combo “would need to be evaluated in a randomized and, ideally, placebo-controlled setting to know if this is a significant improvement.”

He also highlighted the high number of severe cyptopenias with associated complications such as death. “Whether this is acceptable depends on the patient and circumstances,” he said. “But it does suggest that this regimen would potentially be for more robust patients, particularly since the group that did best were those who went to transplant later.”

Pending more research, Dr. Brunner said, “I am not sure I would use [the combination treatment] over gilteritinib monotherapy, for instance. But there may be settings where no other options are available, and this could be considered, particularly if a transplant option is a next step.”

The study was funded by AbbVie, Genentech, and Astellas. The study authors report multiple disclosures; some are employed by Astellas, AbbVie, and Genentech/Roche.

Dr. Bronner reports running clinical trials, advisory board service and/or consultation for Acceleron, Agios, Abbvie, BMS/Celgene, Keros Therapeutics, Novartis, Takeda, GSK, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Gilead.

Adding venetoclax (Venclexta) to a gilteritinib (Xospata) regimen appeared to improve outcomes in refractory/relapsed FLT3-mutated acute myeloid leukemia (AML), a new industry-funded phase 1b study reported.

“.

Outcomes in AML are poor. As the study notes, most patients relapse and face a median overall survival of 4-7 months even with standard chemotherapy. Gilteritinib, a selective oral FLT3 inhibitor, is Food and Drug Administration–approved for the 30% of relapsed/refractory patients with AML who have FLT3 mutations.

“The general sentiment is that, although some patients have great benefit from gilteritinib monotherapy, there is room to improve the quality, frequency, and duration of responses with combinations,” said hematologist Andrew Brunner, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, in an interview. He was not involved with the study research.

For the new open-label, dose-escalation/dose-expansion study, led by hematologist Naval Daver, MD, of the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, researchers enrolled 61 patients (56 with FLT3 mutations) from 2018 to 2020. The median age was 63 years (range 21-85).

The subjects were assigned to get a recommended phase 2 dose of 400 mg venetoclax once daily and 120 mg gilteritinib once daily.

Over a median follow-up of 17.5 months, the median remission time was 4.9 months (95% confidence interval, 3.4-6.6), and the patients with FLT3 mutations survived a median of 10 months.

“The combination of venetoclax and gilteritinib was tolerable at standard doses of each drug, generated remarkably high response rates, and markedly reduced FLT3-internal tandem duplications mutation burden. … Early mortality was similar to gilteritinib monotherapy,” the authors wrote.

Eighty percent of patients experienced cytopenias, and “adverse events prompted venetoclax and gilteritinib dose interruptions in 51% and 48%, respectively.”

About 60% of patients who went on to receive allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were alive at the end of follow-up, “suggesting that VenGilt [the combo treatment] could be an effective bridge to transplant in young/fit patients with relapsed FLT3mut AML,” the researchers wrote.

All patients withdrew from the study by November 2021 for several reasons such as death (n=42), adverse events (n=10), and disease progression (29); some had multiple reasons.

Dr. Brunner said the study is “an important step toward evaluating a new potential regimen.”

The remission duration, FLT3 molecular response, and median overall survival “seem quite encouraging for a severe disease like AML in relapse,” he said. However, he added that the drug combo “would need to be evaluated in a randomized and, ideally, placebo-controlled setting to know if this is a significant improvement.”

He also highlighted the high number of severe cyptopenias with associated complications such as death. “Whether this is acceptable depends on the patient and circumstances,” he said. “But it does suggest that this regimen would potentially be for more robust patients, particularly since the group that did best were those who went to transplant later.”

Pending more research, Dr. Brunner said, “I am not sure I would use [the combination treatment] over gilteritinib monotherapy, for instance. But there may be settings where no other options are available, and this could be considered, particularly if a transplant option is a next step.”

The study was funded by AbbVie, Genentech, and Astellas. The study authors report multiple disclosures; some are employed by Astellas, AbbVie, and Genentech/Roche.

Dr. Bronner reports running clinical trials, advisory board service and/or consultation for Acceleron, Agios, Abbvie, BMS/Celgene, Keros Therapeutics, Novartis, Takeda, GSK, AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Gilead.

FROM JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

What's your diagnosis?

Whipple's disease

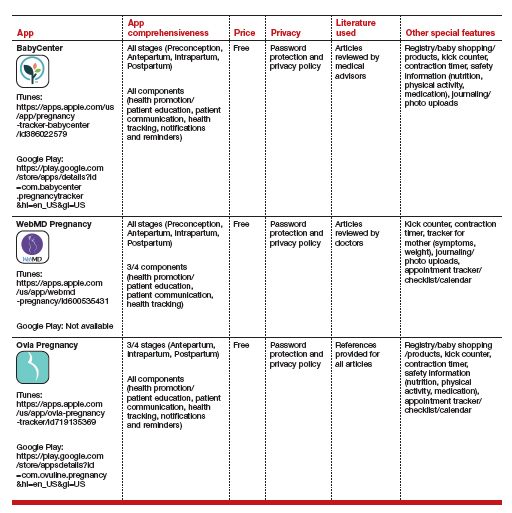

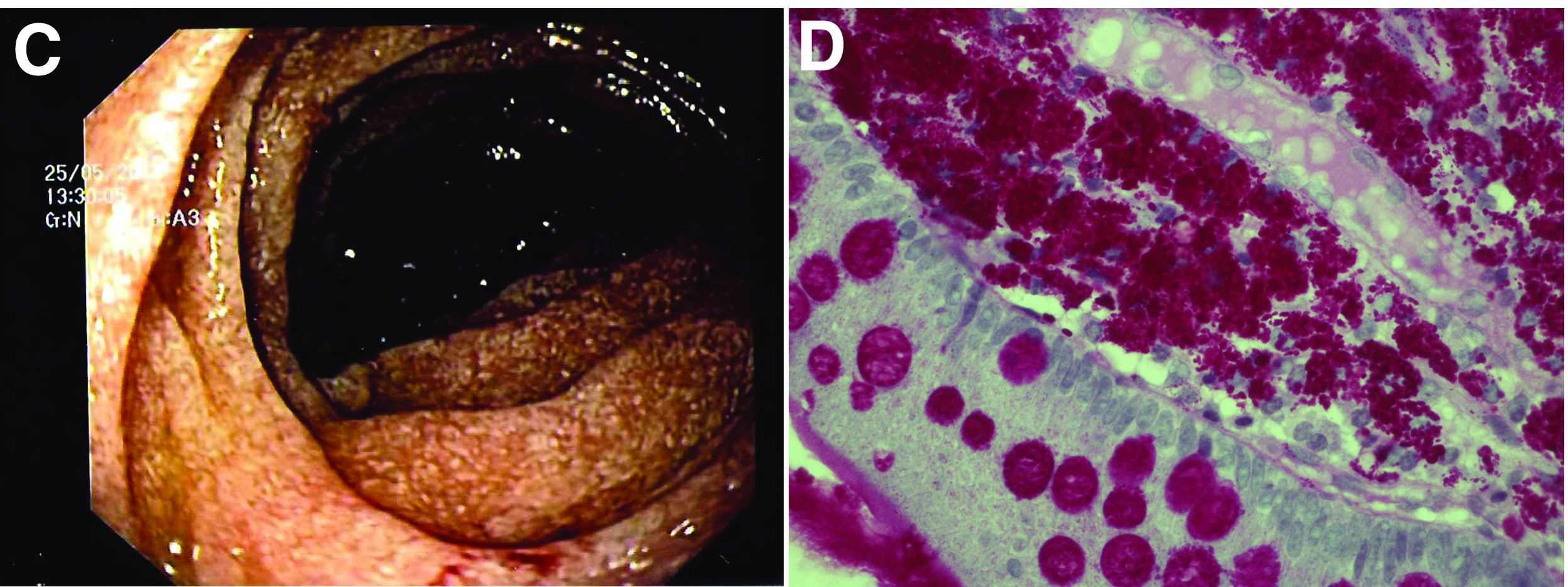

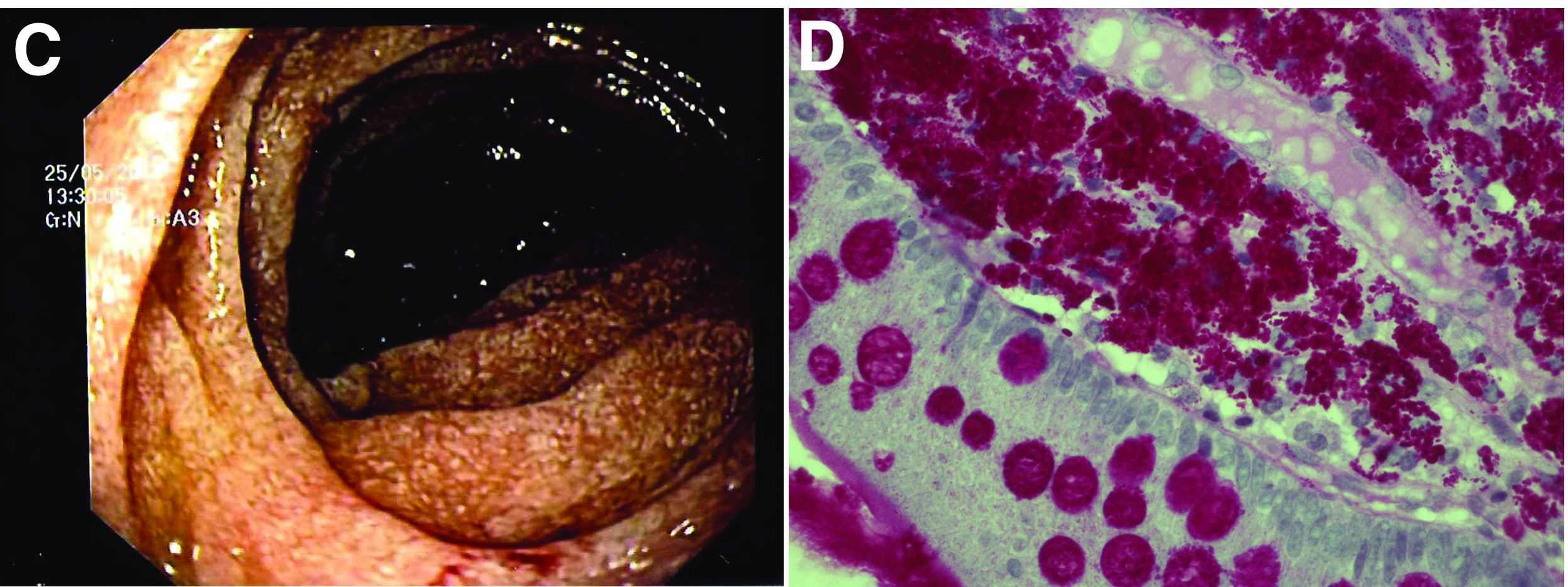

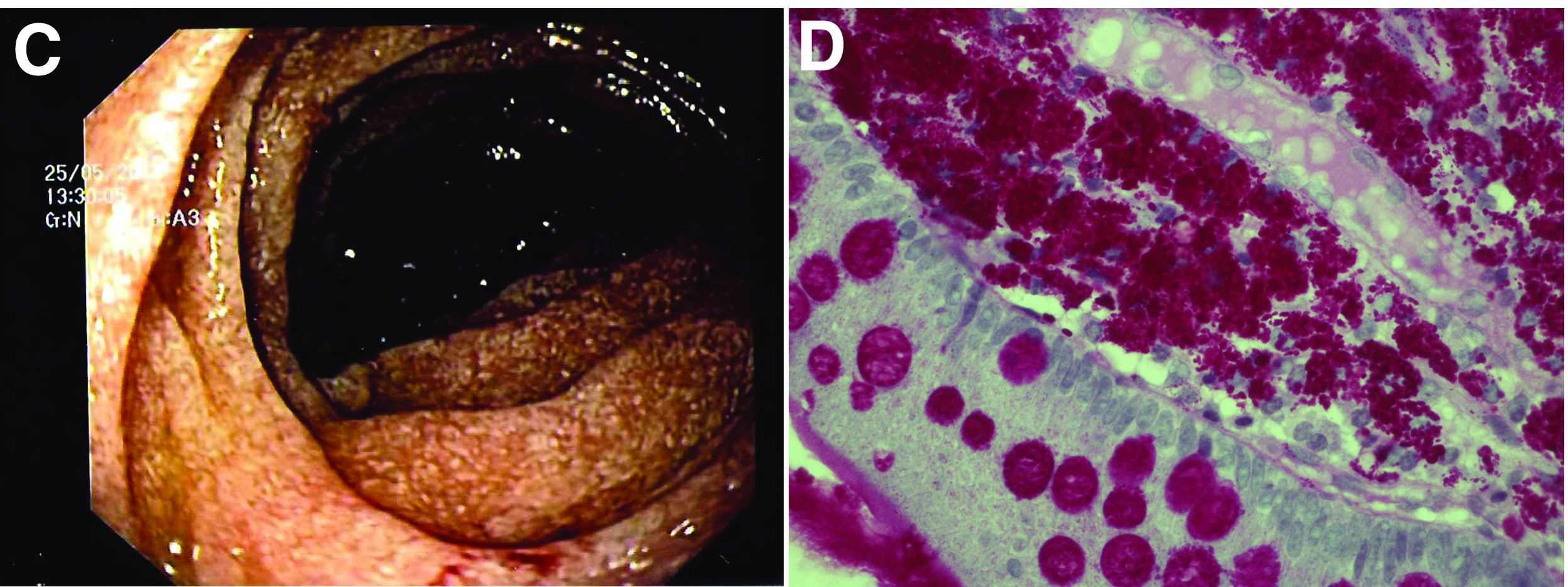

The ultrasound features were highly suggestive of malabsorption, a hypothesis that was supported by the laboratory findings. Celiac disease, one of the most common causes of malabsorption, was excluded by serology tests. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was therefore repeated: The mucosa of the distal first part and second part of the duodenum appeared completely covered with tiny white spots (Figure C). Histologic examination revealed that the mucosal architecture of the villi was altered by the presence of infiltrates of macrophages with wide cytoplasm filled with round periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive inclusions, associated to aggregates of neutrophils attacking the epithelium (Figure D). These histologic findings are consistent with Whipple's disease.

Whipple's disease is a chronic infectious disease caused by a gram-positive ubiquitous bacterium named Tropheryma whipplei. In predisposed subjects with an insufficient T-helper response, for example, those undergoing treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors as in our patient, T. whipplei is able to survive and replicate inside the macrophages of the intestinal mucosa and to spread to other organs.1 Whipple's disease can thus manifest as a multisystemic disease or as a single-organ disease with extraintestinal involvement (e.g., central nervous system, eyes, heart, or lung). The classic form is characterized by weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and signs of malabsorption, typically preceded by a history of arthralgia. The arthralgia is often misdiagnosed as a form of rheumatoid arthritis and therefore treated with immunosuppressant therapy, which favors the onset of the classic intestinal symptoms.

In the literature, few case reports describe the ultrasound findings in patients with Whipple's disease. The most frequent sonographic features include small-bowel dilatation with wall thickening, the presence of peri-intestinal fluid effusion and mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.2,3

The final diagnosis relies on intestinal biopsy and the histologic finding of foamy macrophages containing large amounts of diastase-resistant PAS-positive particles in the lamina propria of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or gastric antral region.

The diagnosis, particularly in cases of extraintestinal involvement, can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction positivity for T. whipplei in the examined tissue.

Therapy consists of the administration of ceftriaxone (2 g IV once daily) for 2 weeks followed by oral therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 1 year.

References

1. Schneider T et al. Whipple's disease: New aspects of pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:179-90.

2. Brindicci D et al. Ultrasonic findings in Whipple's disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:286-8.

3. Neye H et al. Der Morbus Whipple's Disease - A rare intestinal disease and its sonographic characteristics. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(04):314-5.

Whipple's disease

The ultrasound features were highly suggestive of malabsorption, a hypothesis that was supported by the laboratory findings. Celiac disease, one of the most common causes of malabsorption, was excluded by serology tests. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was therefore repeated: The mucosa of the distal first part and second part of the duodenum appeared completely covered with tiny white spots (Figure C). Histologic examination revealed that the mucosal architecture of the villi was altered by the presence of infiltrates of macrophages with wide cytoplasm filled with round periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive inclusions, associated to aggregates of neutrophils attacking the epithelium (Figure D). These histologic findings are consistent with Whipple's disease.

Whipple's disease is a chronic infectious disease caused by a gram-positive ubiquitous bacterium named Tropheryma whipplei. In predisposed subjects with an insufficient T-helper response, for example, those undergoing treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors as in our patient, T. whipplei is able to survive and replicate inside the macrophages of the intestinal mucosa and to spread to other organs.1 Whipple's disease can thus manifest as a multisystemic disease or as a single-organ disease with extraintestinal involvement (e.g., central nervous system, eyes, heart, or lung). The classic form is characterized by weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and signs of malabsorption, typically preceded by a history of arthralgia. The arthralgia is often misdiagnosed as a form of rheumatoid arthritis and therefore treated with immunosuppressant therapy, which favors the onset of the classic intestinal symptoms.

In the literature, few case reports describe the ultrasound findings in patients with Whipple's disease. The most frequent sonographic features include small-bowel dilatation with wall thickening, the presence of peri-intestinal fluid effusion and mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.2,3

The final diagnosis relies on intestinal biopsy and the histologic finding of foamy macrophages containing large amounts of diastase-resistant PAS-positive particles in the lamina propria of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or gastric antral region.

The diagnosis, particularly in cases of extraintestinal involvement, can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction positivity for T. whipplei in the examined tissue.

Therapy consists of the administration of ceftriaxone (2 g IV once daily) for 2 weeks followed by oral therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 1 year.

References

1. Schneider T et al. Whipple's disease: New aspects of pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:179-90.

2. Brindicci D et al. Ultrasonic findings in Whipple's disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:286-8.

3. Neye H et al. Der Morbus Whipple's Disease - A rare intestinal disease and its sonographic characteristics. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(04):314-5.

Whipple's disease

The ultrasound features were highly suggestive of malabsorption, a hypothesis that was supported by the laboratory findings. Celiac disease, one of the most common causes of malabsorption, was excluded by serology tests. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy was therefore repeated: The mucosa of the distal first part and second part of the duodenum appeared completely covered with tiny white spots (Figure C). Histologic examination revealed that the mucosal architecture of the villi was altered by the presence of infiltrates of macrophages with wide cytoplasm filled with round periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive inclusions, associated to aggregates of neutrophils attacking the epithelium (Figure D). These histologic findings are consistent with Whipple's disease.

Whipple's disease is a chronic infectious disease caused by a gram-positive ubiquitous bacterium named Tropheryma whipplei. In predisposed subjects with an insufficient T-helper response, for example, those undergoing treatment with tumor necrosis factor-alpha inhibitors as in our patient, T. whipplei is able to survive and replicate inside the macrophages of the intestinal mucosa and to spread to other organs.1 Whipple's disease can thus manifest as a multisystemic disease or as a single-organ disease with extraintestinal involvement (e.g., central nervous system, eyes, heart, or lung). The classic form is characterized by weight loss, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and signs of malabsorption, typically preceded by a history of arthralgia. The arthralgia is often misdiagnosed as a form of rheumatoid arthritis and therefore treated with immunosuppressant therapy, which favors the onset of the classic intestinal symptoms.

In the literature, few case reports describe the ultrasound findings in patients with Whipple's disease. The most frequent sonographic features include small-bowel dilatation with wall thickening, the presence of peri-intestinal fluid effusion and mesenteric and retroperitoneal lymphadenopathy.2,3

The final diagnosis relies on intestinal biopsy and the histologic finding of foamy macrophages containing large amounts of diastase-resistant PAS-positive particles in the lamina propria of the duodenum, jejunum, ileum, or gastric antral region.

The diagnosis, particularly in cases of extraintestinal involvement, can be confirmed by polymerase chain reaction positivity for T. whipplei in the examined tissue.

Therapy consists of the administration of ceftriaxone (2 g IV once daily) for 2 weeks followed by oral therapy with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for 1 year.

References

1. Schneider T et al. Whipple's disease: New aspects of pathogenesis and treatment. Lancet Infect Dis. 2008;8:179-90.

2. Brindicci D et al. Ultrasonic findings in Whipple's disease. J Clin Ultrasound. 1984;12:286-8.

3. Neye H et al. Der Morbus Whipple's Disease - A rare intestinal disease and its sonographic characteristics. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(04):314-5.

67-year-old woman presented with a year-long history of general malaise, low-grade fever, diarrhea, and a 20-kg weight loss. She had a history of hypertension and depressive disorder. In the previous 4 years, she had undergone several rheumatologic examinations for polyarthritis and, having been diagnosed with seronegative rheumatoid arthritis, she had been treated with steroids, methotrexate, and etanercept, with little benefit.

Recent laboratory tests showed: hemoglobin, 8.3 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 70 fL; erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 78; and C-reactive protein, 6.4 mg/dL. To evaluate the microcytic anemia and the diarrhea, endoscopic investigations had been performed a few months earlier. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed villous atrophy at the level of DII; histology was compatible with intramucosal xanthoma. There were no pathologic findings at colonoscopy. The situation had not been further investigated.

At presentation, the physical examination revealed lower-limb edema, skin and mucosal pallor, and a body mass index of 17.4 kg/m2. Laboratory tests showed microcytic anemia (hemoglobin, 10.0 g/dL; mean corpuscular volume, 74 fL), increased acute-phase proteins (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, 59; C-reactive protein, 8.53 mg/dL), and malabsorption (albumin, 2.5 g/dL; multiple electrolytes deficiencies including iron, vitamin A, and vitamin D deficiency).

Abdominal ultrasound examination revealed three small lymph nodes in the periaortic region (maximum diameter, 10 mm), marked mesenteric and ileal wall thickening, mild jejunal wall thickening, an increased number of connivent valves, and a mild amount of peri-intestinal fluid effusion (Figure A, B).

What is the likely diagnosis and the appropriate treatment?

The winding road that leads to optimal temperature management after cardiac arrest

In 2002, two landmark trials found that targeted temperature management (TTM) after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest led to improvements in neurologic outcomes. The larger of the two trials found a reduction in mortality. Such treatment benefits are hard to come by in critical care in general and in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in particular. With the therapeutic overconfidence typical of our profession, my institution embraced TTM quickly and completely soon after these trials were published. Remember, this was “back in the day” when sepsis management included drotrecogin alfa, Cortrosyn stim tests, tight glucose control (90-120 mg/dL), and horrible over-resuscitation via the early goal-directed therapy paradigm.

If you’ve been practicing critical care medicine for more than a few years, you already know where I’m going. Most of the interventions in the preceding paragraph were adopted but discarded before 2010. Hypothermia – temperature management with a goal of 32-36° C – has been struggling to stay relevant ever since the publication of the TTM randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 2013. Then came the HYPERION trial, which brought the 32-36° C target back from the dead (pun definitely intended) in 2019. This is critical care medicine: Today’s life-saving intervention proves harmful tomorrow, but withholding it may constitute malpractice a few months down the road.

So where are we now? Good question. I’ve had seasoned neurointensivists insist that 33° C remains the standard of care and others who’ve endorsed normothermia. So much for finding an answer via my more specialized colleagues.

Let’s go to the guidelines then. Prompted largely by HYPERION, a temperature target of 32-36° C was endorsed in 2020 and 2021. Then came publication of the TTM2 trial, the largest temperature management RCT to date, which found no benefit to targeting 33° C. A network meta-analysis published in 2021 reached a similar conclusion. A recently released update by the same international guideline group now recommends targeting normothermia (< 37.7° C) and avoiding fever, and it specifically says that there is insufficient evidence to support a 32-36° C target. Okay, everyone tracking all that?

Lest I sound overly catty and nihilistic, I see all this in a positive light. Huge credit goes to the critical care medicine academic community for putting together so many RCTs. The scientific reality is that it takes “a lotta” sample size to clarify the effects of an intervention. Throw in the inevitable bevy of confounders (in- vs. out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, resuscitation time, initial rhythm, and so on), and you get a feel for the work required to understand a treatment’s true effects.

Advances in guideline science and the hard, often unpaid work of panels are also important. The guideline panel I’ve been citing came out for aggressive temperature control (32-36° C) a few months before the TTM2 RCT was published. In the past, they updated their recommendations every 5 years, but this time, they were out with a new manuscript that incorporated TTM2 in less than a year. If you’ve been involved at any level with producing guidelines, you can appreciate this achievement. Assuming that aggressive hypothermia is truly harmful, waiting 5 years to incorporate TTM2 could have led to significant morbidity.

I do take issue with you early adopters, though. Given the litany of failed therapies that have shown initial promise, and the well-documented human tendency to underestimate the impact of sample size, your rapid implementation of major interventions is puzzling. One might think you’d learned your lessons after seeing drotrecogin alfa, Cortrosyn stim tests, tight glucose control, early goal-directed therapy, and aggressive TTM come and go. Your recent enthusiasm for vitamin C after publication of a single before-after study suggests that you haven’t.

Aaron B. Holley, MD, is an associate professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University and program director of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md. He has received a research grant from Fisher-Paykel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2002, two landmark trials found that targeted temperature management (TTM) after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest led to improvements in neurologic outcomes. The larger of the two trials found a reduction in mortality. Such treatment benefits are hard to come by in critical care in general and in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in particular. With the therapeutic overconfidence typical of our profession, my institution embraced TTM quickly and completely soon after these trials were published. Remember, this was “back in the day” when sepsis management included drotrecogin alfa, Cortrosyn stim tests, tight glucose control (90-120 mg/dL), and horrible over-resuscitation via the early goal-directed therapy paradigm.

If you’ve been practicing critical care medicine for more than a few years, you already know where I’m going. Most of the interventions in the preceding paragraph were adopted but discarded before 2010. Hypothermia – temperature management with a goal of 32-36° C – has been struggling to stay relevant ever since the publication of the TTM randomized controlled trial (RCT) in 2013. Then came the HYPERION trial, which brought the 32-36° C target back from the dead (pun definitely intended) in 2019. This is critical care medicine: Today’s life-saving intervention proves harmful tomorrow, but withholding it may constitute malpractice a few months down the road.

So where are we now? Good question. I’ve had seasoned neurointensivists insist that 33° C remains the standard of care and others who’ve endorsed normothermia. So much for finding an answer via my more specialized colleagues.

Let’s go to the guidelines then. Prompted largely by HYPERION, a temperature target of 32-36° C was endorsed in 2020 and 2021. Then came publication of the TTM2 trial, the largest temperature management RCT to date, which found no benefit to targeting 33° C. A network meta-analysis published in 2021 reached a similar conclusion. A recently released update by the same international guideline group now recommends targeting normothermia (< 37.7° C) and avoiding fever, and it specifically says that there is insufficient evidence to support a 32-36° C target. Okay, everyone tracking all that?

Lest I sound overly catty and nihilistic, I see all this in a positive light. Huge credit goes to the critical care medicine academic community for putting together so many RCTs. The scientific reality is that it takes “a lotta” sample size to clarify the effects of an intervention. Throw in the inevitable bevy of confounders (in- vs. out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, resuscitation time, initial rhythm, and so on), and you get a feel for the work required to understand a treatment’s true effects.

Advances in guideline science and the hard, often unpaid work of panels are also important. The guideline panel I’ve been citing came out for aggressive temperature control (32-36° C) a few months before the TTM2 RCT was published. In the past, they updated their recommendations every 5 years, but this time, they were out with a new manuscript that incorporated TTM2 in less than a year. If you’ve been involved at any level with producing guidelines, you can appreciate this achievement. Assuming that aggressive hypothermia is truly harmful, waiting 5 years to incorporate TTM2 could have led to significant morbidity.

I do take issue with you early adopters, though. Given the litany of failed therapies that have shown initial promise, and the well-documented human tendency to underestimate the impact of sample size, your rapid implementation of major interventions is puzzling. One might think you’d learned your lessons after seeing drotrecogin alfa, Cortrosyn stim tests, tight glucose control, early goal-directed therapy, and aggressive TTM come and go. Your recent enthusiasm for vitamin C after publication of a single before-after study suggests that you haven’t.

Aaron B. Holley, MD, is an associate professor of medicine at Uniformed Services University and program director of pulmonary and critical care medicine at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center, Bethesda, Md. He has received a research grant from Fisher-Paykel.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In 2002, two landmark trials found that targeted temperature management (TTM) after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest led to improvements in neurologic outcomes. The larger of the two trials found a reduction in mortality. Such treatment benefits are hard to come by in critical care in general and in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in particular. With the therapeutic overconfidence typical of our profession, my institution embraced TTM quickly and completely soon after these trials were published. Remember, this was “back in the day” when sepsis management included drotrecogin alfa, Cortrosyn stim tests, tight glucose control (90-120 mg/dL), and horrible over-resuscitation via the early goal-directed therapy paradigm.