User login

Inflation will be the end of medicine

Inflation is the senility of democracies.

–Sylvia Townsend Warner

Electronic medical records? No, all of these are minor annoyances in the face of the practice killer, inflation.

Physicians live in a closed box where medical reimbursements are fixed, directly or by contract proxy to the government (Medicare) pay rate. Inflation is projected to be between 5% and 10% this year. We cannot increase our rates to increase the salaries of our employees, cover our increased medical disposable costs, and pay more for our state licensures and DEA registrations. No, we must try to find savings in our budget, which we have been squeezing for years.

Currently, medicine is facing a 9.75% cut in Medicare reimbursements, which will reset most private insurance rates, based on a percentage of Medicare. The temporary 3.75% conversion factor (CF) increase for all services is expiring. Also expiring is the 2% sequester from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), signed into law in August 2011. This was originally scheduled to sunset in 2021, but is going to continue to 2030.

A 4% statutory pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) sequester resulting from passage of the American Rescue Plan Act is being imposed. Statutory PAYGO is a policy written into law (it can be changed only through new legislation) that requires deficit neutrality overall in the laws (other than annual appropriations) enacted by Congress and imposes automatic spending reductions at the end of the year if such laws increase the deficit when they are added together.

There is a statutory freeze on Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) updates until 2026, at which time an annual increase of 0.25%, which is lower than inflation, will be enacted. This adds up to a 9.75% cut in Medicare pay until at least 2026. Recall that almost all of your private insurance contracts are tied to Medicare (some more, some less) and that this cut to the physician is doubled if your overhead is fixed at the typical 50% for most practices. This means an almost 20% cut in take-home pay for most physicians.

Now, when considering the most recent inflation number, which projects 5%-10% inflation for this year and at least 2% annually in the future, which compounds yearly (the Fed target), you are looking at catastrophic numbers.

The conversion factor – the pool of money doled out to physicians – has failed to keep pace with inflation – even at 2%-3% a year – and reimbursement is only 50% of what it was when created in 1998, despite small increases by Congress along the way. A recent Wall Street Journal guest editorial claimed that Medicare payments benefited from cost of living adjustments, same as Social Security. I do not agree, hence the 50% pay gap since 1998.

In addition, the costs of running a practice have increased by 37% between 2001 and 2020, 1.7% per year, according to the Medicare Economic Index.

Some of this may include general inflation, but certainly new OSHA rules, electronic medical records, Medicare quality improvement measures, and assorted other costs do not. So based on my own conservative estimate, on top of the 50% decline in the payment pool, physicians’ noninflationary operating costs increased by at least another 10% over the last 20 odd years. This is a 60% decline in reimbursements!

Medicare payments have been under pressure from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) anti-inflationary payment policies for more than 20 years. While physician services represent a very modest portion of the overall growth in health care costs, they are an easy target for cuts when policymakers seek to limit spending. Although we avoided direct cuts to reimbursements caused by the Medicare sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) – which was enacted in 1997 and repealed in 2015 – Medicare provider payments have remained constrained by a budget-neutral financing system.

There used to be ways out of the box. Physicians could go to work for hospitals or have their practices acquired by them, resulting in much better hospital-based reimbursement. This has been eliminated by site-neutral payments, which while instituted by President Trump, are unopposed by President Biden. You could also join larger groups with some loss of autonomy, which could presumably negotiate better rates with private insurers as another way out, but these rates are almost always based on a percentage of Medicare as noted above.

There may be a bit of good news, with price transparency being instituted, which again is unopposed by the Biden administration. At least private practice physicians may be able to show their services are a bargain compared to hospitals.

One could also take the low road, and sell out to private equity, but I suspect these deals will become much less attractive since some of these entities are going broke and all will feel the bite of lower reimbursements.

Physicians and patients should rise up and demand better reimbursements for physicians, or there will be no physicians to see. This is not greed, a bigger house, or a newer car, this is becoming a matter of practice survival. And seniors are not greedy, they have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars into Medicare in taxes for health insurance in retirement.

Physicians and retirees should contact their federal legislators and let them know a 9.75% cut is untenable and ask for Medicare rates to be fixed to the cost of living, just as Social Security is. Before we fund trillions of dollars in new government programs, perhaps we should look to the solvency of the existing ones we have.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Inflation is the senility of democracies.

–Sylvia Townsend Warner

Electronic medical records? No, all of these are minor annoyances in the face of the practice killer, inflation.

Physicians live in a closed box where medical reimbursements are fixed, directly or by contract proxy to the government (Medicare) pay rate. Inflation is projected to be between 5% and 10% this year. We cannot increase our rates to increase the salaries of our employees, cover our increased medical disposable costs, and pay more for our state licensures and DEA registrations. No, we must try to find savings in our budget, which we have been squeezing for years.

Currently, medicine is facing a 9.75% cut in Medicare reimbursements, which will reset most private insurance rates, based on a percentage of Medicare. The temporary 3.75% conversion factor (CF) increase for all services is expiring. Also expiring is the 2% sequester from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), signed into law in August 2011. This was originally scheduled to sunset in 2021, but is going to continue to 2030.

A 4% statutory pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) sequester resulting from passage of the American Rescue Plan Act is being imposed. Statutory PAYGO is a policy written into law (it can be changed only through new legislation) that requires deficit neutrality overall in the laws (other than annual appropriations) enacted by Congress and imposes automatic spending reductions at the end of the year if such laws increase the deficit when they are added together.

There is a statutory freeze on Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) updates until 2026, at which time an annual increase of 0.25%, which is lower than inflation, will be enacted. This adds up to a 9.75% cut in Medicare pay until at least 2026. Recall that almost all of your private insurance contracts are tied to Medicare (some more, some less) and that this cut to the physician is doubled if your overhead is fixed at the typical 50% for most practices. This means an almost 20% cut in take-home pay for most physicians.

Now, when considering the most recent inflation number, which projects 5%-10% inflation for this year and at least 2% annually in the future, which compounds yearly (the Fed target), you are looking at catastrophic numbers.

The conversion factor – the pool of money doled out to physicians – has failed to keep pace with inflation – even at 2%-3% a year – and reimbursement is only 50% of what it was when created in 1998, despite small increases by Congress along the way. A recent Wall Street Journal guest editorial claimed that Medicare payments benefited from cost of living adjustments, same as Social Security. I do not agree, hence the 50% pay gap since 1998.

In addition, the costs of running a practice have increased by 37% between 2001 and 2020, 1.7% per year, according to the Medicare Economic Index.

Some of this may include general inflation, but certainly new OSHA rules, electronic medical records, Medicare quality improvement measures, and assorted other costs do not. So based on my own conservative estimate, on top of the 50% decline in the payment pool, physicians’ noninflationary operating costs increased by at least another 10% over the last 20 odd years. This is a 60% decline in reimbursements!

Medicare payments have been under pressure from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) anti-inflationary payment policies for more than 20 years. While physician services represent a very modest portion of the overall growth in health care costs, they are an easy target for cuts when policymakers seek to limit spending. Although we avoided direct cuts to reimbursements caused by the Medicare sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) – which was enacted in 1997 and repealed in 2015 – Medicare provider payments have remained constrained by a budget-neutral financing system.

There used to be ways out of the box. Physicians could go to work for hospitals or have their practices acquired by them, resulting in much better hospital-based reimbursement. This has been eliminated by site-neutral payments, which while instituted by President Trump, are unopposed by President Biden. You could also join larger groups with some loss of autonomy, which could presumably negotiate better rates with private insurers as another way out, but these rates are almost always based on a percentage of Medicare as noted above.

There may be a bit of good news, with price transparency being instituted, which again is unopposed by the Biden administration. At least private practice physicians may be able to show their services are a bargain compared to hospitals.

One could also take the low road, and sell out to private equity, but I suspect these deals will become much less attractive since some of these entities are going broke and all will feel the bite of lower reimbursements.

Physicians and patients should rise up and demand better reimbursements for physicians, or there will be no physicians to see. This is not greed, a bigger house, or a newer car, this is becoming a matter of practice survival. And seniors are not greedy, they have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars into Medicare in taxes for health insurance in retirement.

Physicians and retirees should contact their federal legislators and let them know a 9.75% cut is untenable and ask for Medicare rates to be fixed to the cost of living, just as Social Security is. Before we fund trillions of dollars in new government programs, perhaps we should look to the solvency of the existing ones we have.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Inflation is the senility of democracies.

–Sylvia Townsend Warner

Electronic medical records? No, all of these are minor annoyances in the face of the practice killer, inflation.

Physicians live in a closed box where medical reimbursements are fixed, directly or by contract proxy to the government (Medicare) pay rate. Inflation is projected to be between 5% and 10% this year. We cannot increase our rates to increase the salaries of our employees, cover our increased medical disposable costs, and pay more for our state licensures and DEA registrations. No, we must try to find savings in our budget, which we have been squeezing for years.

Currently, medicine is facing a 9.75% cut in Medicare reimbursements, which will reset most private insurance rates, based on a percentage of Medicare. The temporary 3.75% conversion factor (CF) increase for all services is expiring. Also expiring is the 2% sequester from the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA), signed into law in August 2011. This was originally scheduled to sunset in 2021, but is going to continue to 2030.

A 4% statutory pay-as-you-go (PAYGO) sequester resulting from passage of the American Rescue Plan Act is being imposed. Statutory PAYGO is a policy written into law (it can be changed only through new legislation) that requires deficit neutrality overall in the laws (other than annual appropriations) enacted by Congress and imposes automatic spending reductions at the end of the year if such laws increase the deficit when they are added together.

There is a statutory freeze on Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) updates until 2026, at which time an annual increase of 0.25%, which is lower than inflation, will be enacted. This adds up to a 9.75% cut in Medicare pay until at least 2026. Recall that almost all of your private insurance contracts are tied to Medicare (some more, some less) and that this cut to the physician is doubled if your overhead is fixed at the typical 50% for most practices. This means an almost 20% cut in take-home pay for most physicians.

Now, when considering the most recent inflation number, which projects 5%-10% inflation for this year and at least 2% annually in the future, which compounds yearly (the Fed target), you are looking at catastrophic numbers.

The conversion factor – the pool of money doled out to physicians – has failed to keep pace with inflation – even at 2%-3% a year – and reimbursement is only 50% of what it was when created in 1998, despite small increases by Congress along the way. A recent Wall Street Journal guest editorial claimed that Medicare payments benefited from cost of living adjustments, same as Social Security. I do not agree, hence the 50% pay gap since 1998.

In addition, the costs of running a practice have increased by 37% between 2001 and 2020, 1.7% per year, according to the Medicare Economic Index.

Some of this may include general inflation, but certainly new OSHA rules, electronic medical records, Medicare quality improvement measures, and assorted other costs do not. So based on my own conservative estimate, on top of the 50% decline in the payment pool, physicians’ noninflationary operating costs increased by at least another 10% over the last 20 odd years. This is a 60% decline in reimbursements!

Medicare payments have been under pressure from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) anti-inflationary payment policies for more than 20 years. While physician services represent a very modest portion of the overall growth in health care costs, they are an easy target for cuts when policymakers seek to limit spending. Although we avoided direct cuts to reimbursements caused by the Medicare sustainable growth rate formula (SGR) – which was enacted in 1997 and repealed in 2015 – Medicare provider payments have remained constrained by a budget-neutral financing system.

There used to be ways out of the box. Physicians could go to work for hospitals or have their practices acquired by them, resulting in much better hospital-based reimbursement. This has been eliminated by site-neutral payments, which while instituted by President Trump, are unopposed by President Biden. You could also join larger groups with some loss of autonomy, which could presumably negotiate better rates with private insurers as another way out, but these rates are almost always based on a percentage of Medicare as noted above.

There may be a bit of good news, with price transparency being instituted, which again is unopposed by the Biden administration. At least private practice physicians may be able to show their services are a bargain compared to hospitals.

One could also take the low road, and sell out to private equity, but I suspect these deals will become much less attractive since some of these entities are going broke and all will feel the bite of lower reimbursements.

Physicians and patients should rise up and demand better reimbursements for physicians, or there will be no physicians to see. This is not greed, a bigger house, or a newer car, this is becoming a matter of practice survival. And seniors are not greedy, they have paid hundreds of thousands of dollars into Medicare in taxes for health insurance in retirement.

Physicians and retirees should contact their federal legislators and let them know a 9.75% cut is untenable and ask for Medicare rates to be fixed to the cost of living, just as Social Security is. Before we fund trillions of dollars in new government programs, perhaps we should look to the solvency of the existing ones we have.

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Connecticut chapter of ACC at center of Twitter dustup

Tweets from a black female medical student about the perils of being on call after lengthy hospital shifts was met with a stinging rebuke from the Twitter account of the Connecticut chapter of the American College of Cardiology – prompting an apology and some high-octane exchanges on medical Twitter.

In a series of Tweets, “queen of anonymous medicine” @QueenMD202X describes one friend “working 87 hours this week and 13 days straight” and a second, a third-year medical student working a 15-hour surgical shift. “That is cruel,” she writes, “15-hour shift? For what?????”

In response to a Tweet suggesting that being on call can be a valuable experience for students to know what they’re facing once they get to residency, @QueenMD202X pointed out the 15-hour shifts aren’t just a one-off.

In a now-deleted Tweet that nevertheless appears in several additional tweets as a screenshot, @ConnecticutACC replied: “You might be in the wrong field. You sound very angry probably unsuitable for patient care when your mental state is as you describe it. Emotions are contagious.”

The response from the medical and broader Twitter community was swift, with several tweets calling the chapter’s reply insensitive and racist.

In another Tweet, @BrittGratreak responded by stating: “I think institutions need to be more transparent how they basically weigh the costs & benefits of writing a memorial statement for students who die by suicide rather than investing in changing the toxic culture of medical education to prevent deaths & producing harmed physicians.”

Within hours, Connecticut-ACC issued an apology from their now-deleted account and questioned the origins of the Tweet. “We sincerely apologize for the earlier post as the views do not represent the values or beliefs of the Chapter or broader ACC. We are working to ID its origins. Burnout & well-being are critical issues [that] ACC/CCACC is working to address on behalf of members at all career stages.”

Speaking to this news organization, Connecticut-ACC president and governor Craig McPherson, MD, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the chapter believes its account was hacked.

“We provide limited password access to our Twitter account, and we assume, since we’ve contacted most of the individuals who had access to the current password and all of the them deny any knowledge, the account got hacked … it’s just one of those unfortunate aspects of social media,” he said.

The password was quickly changed after the chapter learned of the Tweet on Wednesday and the account has since been closed, at Dr. McPherson’s request.

“We don’t condone that kind of language, that kind of remark. It’s highly inappropriate, and I certainly agree with anyone that voiced that opinion in the Twitterstorm that followed,” he said. “But as I said at the outset, I have no control over what people say on social media once it’s out there. All we can do is apologize for the fact our Twitter feed was used as a vehicle for those comments, which we consider inappropriate.”

Asked whether he considered the remarks racist, Dr. McPherson replied: “That’s not for me to judge.”

ACC president Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, however, weighed in this afternoon with a Tweet citing the need to address clinician well-being and an inclusive workplace.

Some on Twitter recalled their own long hours as a medical student or defended the need to inculcate students in the long hours they’ll face as physicians. Others observed that neither ACC nor its Connecticut chapter addressed the issue of medical student hours in their response. Although fellow and resident hours are regulated, Dr. McPherson pointed out that it’s up to each individual medical school to set the hours for their students.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tweets from a black female medical student about the perils of being on call after lengthy hospital shifts was met with a stinging rebuke from the Twitter account of the Connecticut chapter of the American College of Cardiology – prompting an apology and some high-octane exchanges on medical Twitter.

In a series of Tweets, “queen of anonymous medicine” @QueenMD202X describes one friend “working 87 hours this week and 13 days straight” and a second, a third-year medical student working a 15-hour surgical shift. “That is cruel,” she writes, “15-hour shift? For what?????”

In response to a Tweet suggesting that being on call can be a valuable experience for students to know what they’re facing once they get to residency, @QueenMD202X pointed out the 15-hour shifts aren’t just a one-off.

In a now-deleted Tweet that nevertheless appears in several additional tweets as a screenshot, @ConnecticutACC replied: “You might be in the wrong field. You sound very angry probably unsuitable for patient care when your mental state is as you describe it. Emotions are contagious.”

The response from the medical and broader Twitter community was swift, with several tweets calling the chapter’s reply insensitive and racist.

In another Tweet, @BrittGratreak responded by stating: “I think institutions need to be more transparent how they basically weigh the costs & benefits of writing a memorial statement for students who die by suicide rather than investing in changing the toxic culture of medical education to prevent deaths & producing harmed physicians.”

Within hours, Connecticut-ACC issued an apology from their now-deleted account and questioned the origins of the Tweet. “We sincerely apologize for the earlier post as the views do not represent the values or beliefs of the Chapter or broader ACC. We are working to ID its origins. Burnout & well-being are critical issues [that] ACC/CCACC is working to address on behalf of members at all career stages.”

Speaking to this news organization, Connecticut-ACC president and governor Craig McPherson, MD, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the chapter believes its account was hacked.

“We provide limited password access to our Twitter account, and we assume, since we’ve contacted most of the individuals who had access to the current password and all of the them deny any knowledge, the account got hacked … it’s just one of those unfortunate aspects of social media,” he said.

The password was quickly changed after the chapter learned of the Tweet on Wednesday and the account has since been closed, at Dr. McPherson’s request.

“We don’t condone that kind of language, that kind of remark. It’s highly inappropriate, and I certainly agree with anyone that voiced that opinion in the Twitterstorm that followed,” he said. “But as I said at the outset, I have no control over what people say on social media once it’s out there. All we can do is apologize for the fact our Twitter feed was used as a vehicle for those comments, which we consider inappropriate.”

Asked whether he considered the remarks racist, Dr. McPherson replied: “That’s not for me to judge.”

ACC president Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, however, weighed in this afternoon with a Tweet citing the need to address clinician well-being and an inclusive workplace.

Some on Twitter recalled their own long hours as a medical student or defended the need to inculcate students in the long hours they’ll face as physicians. Others observed that neither ACC nor its Connecticut chapter addressed the issue of medical student hours in their response. Although fellow and resident hours are regulated, Dr. McPherson pointed out that it’s up to each individual medical school to set the hours for their students.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Tweets from a black female medical student about the perils of being on call after lengthy hospital shifts was met with a stinging rebuke from the Twitter account of the Connecticut chapter of the American College of Cardiology – prompting an apology and some high-octane exchanges on medical Twitter.

In a series of Tweets, “queen of anonymous medicine” @QueenMD202X describes one friend “working 87 hours this week and 13 days straight” and a second, a third-year medical student working a 15-hour surgical shift. “That is cruel,” she writes, “15-hour shift? For what?????”

In response to a Tweet suggesting that being on call can be a valuable experience for students to know what they’re facing once they get to residency, @QueenMD202X pointed out the 15-hour shifts aren’t just a one-off.

In a now-deleted Tweet that nevertheless appears in several additional tweets as a screenshot, @ConnecticutACC replied: “You might be in the wrong field. You sound very angry probably unsuitable for patient care when your mental state is as you describe it. Emotions are contagious.”

The response from the medical and broader Twitter community was swift, with several tweets calling the chapter’s reply insensitive and racist.

In another Tweet, @BrittGratreak responded by stating: “I think institutions need to be more transparent how they basically weigh the costs & benefits of writing a memorial statement for students who die by suicide rather than investing in changing the toxic culture of medical education to prevent deaths & producing harmed physicians.”

Within hours, Connecticut-ACC issued an apology from their now-deleted account and questioned the origins of the Tweet. “We sincerely apologize for the earlier post as the views do not represent the values or beliefs of the Chapter or broader ACC. We are working to ID its origins. Burnout & well-being are critical issues [that] ACC/CCACC is working to address on behalf of members at all career stages.”

Speaking to this news organization, Connecticut-ACC president and governor Craig McPherson, MD, Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said the chapter believes its account was hacked.

“We provide limited password access to our Twitter account, and we assume, since we’ve contacted most of the individuals who had access to the current password and all of the them deny any knowledge, the account got hacked … it’s just one of those unfortunate aspects of social media,” he said.

The password was quickly changed after the chapter learned of the Tweet on Wednesday and the account has since been closed, at Dr. McPherson’s request.

“We don’t condone that kind of language, that kind of remark. It’s highly inappropriate, and I certainly agree with anyone that voiced that opinion in the Twitterstorm that followed,” he said. “But as I said at the outset, I have no control over what people say on social media once it’s out there. All we can do is apologize for the fact our Twitter feed was used as a vehicle for those comments, which we consider inappropriate.”

Asked whether he considered the remarks racist, Dr. McPherson replied: “That’s not for me to judge.”

ACC president Dipti Itchhaporia, MD, however, weighed in this afternoon with a Tweet citing the need to address clinician well-being and an inclusive workplace.

Some on Twitter recalled their own long hours as a medical student or defended the need to inculcate students in the long hours they’ll face as physicians. Others observed that neither ACC nor its Connecticut chapter addressed the issue of medical student hours in their response. Although fellow and resident hours are regulated, Dr. McPherson pointed out that it’s up to each individual medical school to set the hours for their students.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Doctor wins restraining order against CVS after prescription ban

In an Aug. 11 decision, District Court Judge William Bertelsman ordered CVS to stop refusing prescriptions written by Kendall E. Hansen, MD. Judge Bertelsman ruled that Dr. Hansen is likely to succeed in his claim that CVS barred his prescriptions without evidence that he violated any law or professional protocol. The restraining order will remain in place while Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit against CVS Pharmacy proceeds.

Ronald W. Chapman II, an attorney representing Dr. Hansen, said the order is groundbreaking and that, to his knowledge, it’s the first time a federal court has overturned a pharmacy’s decision to block a prescriber.

“We believe that CVS’ decision was based solely on algorithms they use to analyze prescriber practices and not an any individual review of patient records,” Mr. Chapman said. “In fact, we invited CVS to come out to Dr. Hansen’s practice and look at how he was treating patients and ensure things were compliant, but they refused. Instead, they had a phone call with him then cut his patients off.”

Michael DeAngelis, a spokesman for CVS, said the court’s order illustrates the proverbial rock and hard place that pharmacies are placed between in the country’s fight against the misuse of prescription opioids.

“It is alleged in many lawsuits that pharmacies fill too many opioid prescriptions and should operate programs that use data to block prescriptions written by some doctors,” Mr. DeAngelis told this news organization. “And yet other lawsuits, including this one, argue that we should not operate programs that may block prescriptions. Such contradictions are grossly unfair to the pharmacy profession.”

Mr. DeAngelis declined to comment about Dr. Hansen’s claims or specify what led CVS to refuse his prescriptions.

Dr. Hansen declined to comment for this story through his attorney.

Dr. Hansen is no stranger to the spotlight. The Northern Kentucky pain doctor made headlines in 2012 when two of his horses, Fast and Accurate, and Hansen, ran in the Kentucky Derby. In February 2019, he drew media attention when his practice, Interventional Pain Specialists in Crestview Hills, Ky., was raided by federal agents. Dr. Hansen owns and operates the facility, which serves patients in Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.

The search yielded no findings, and no charges were filed, according to Mr. Chapman. Scott Hardcorn, director of the Northern Kentucky Drug Strike Force, confirmed that his agency assisted in the operation but said he was unaware of the outcome and that his officers generated no reports from the investigation. A spokesperson for the Drug Enforcement Administration would not comment about the investigation and directed a reporter for this news organization to the DEA website where enforcement actions are listed. No records or actions against Dr. Hansen can be found.

The CVS complaint stems from actions taken by the pharmacy against Dr. Hansen earlier this year. In June, a pharmacy representative allegedly contacted Dr. Hansen by phone and asked him questions about his practice and his prescribing practices, according to his lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky. During the call, the representative did not inform Dr. Hansen that any of his prescriptions were in question or were suspected of being medically unnecessary, the complaint alleges.

On July 28, 2021, CVS sent Dr. Hansen a letter announcing that its pharmacies would no longer be honoring his prescriptions. The letter, entered as an exhibit in the lawsuit, states that CVS contacted Dr. Hansen twice in 2021 about his prescribing practices, once in May and again in June.

“Despite our attempts to resolve the concerns with your controlled substance prescribing patterns, these concerns persist,” Kahra Lutkiewicz, director of CVS’ retail pharmacy professional practice, wrote in the letter. “Thus, we are writing to inform you that effective Aug. 5, 2021, CVS/pharmacy stores will no longer be able to fill prescriptions that you write for controlled substances. We take our compliance obligations very seriously, and after careful consideration, find it necessary to take this action.”

The letter does not explain the details behind CVS’ concerns.

Dr. Hansen sued CVS on Aug. 4 for tortious interference with a business relationship and defamation, among other claims. His complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen and his patients will suffer irreparable injury if the prescription decision stands. More than 250 of Dr. Hansen’s patients use CVS pharmacies for their prescriptions, and some are locked into using the pharmacy because of insurance contracts, Mr. Chapman said.

“There really is nowhere else for these patients to go,” Mr. Chapman said. “They would have to go to a new doctor and establish a new relationship, and obviously that has devastating consequences when we’re talking about people who need their medication.”

CVS has not yet issued a written response to the lawsuit. In his order, Judge Bertelsman stated that a preliminary conference was held in which all parties were represented and stated their positions to the judge.

“Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims that defendant has interfered with plaintiffs’ relationships with their patients by refusing to fill prescriptions written by plaintiffs, and defendant has done so without evidence that plaintiffs have violated any law or professional protocol related to such prescriptions,” Judge Bertelsman wrote. “The balance of the hardships between the parties weighs in favor of issuing a temporary restraining order inasmuch as defendant’s actions pose a threat to plaintiffs’ professional reputation and livelihood and ... because plaintiffs’ patients’ medical care is implicated by defendant’s actions, the public interest weighs in favor of issuance of the temporary restraining order.”

Dr. Hansen is currently embroiled in several other legal battles as both a plaintiff and a defendant.

In 2019, a patient sued him for negligence and fraud for allegedly performing medically unnecessary and excessive injection therapy. The suit claims the patient was required to undergo injection therapy on a continuing basis in order to receive her narcotic pain medication, according to the lawsuit filed in Kenton Circuit Court. The complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen made false representations to the patient and to her insurers that the injections were necessary for the treatment of the patient’s chronic pain.

The federal government is not involved in the case.

The negligence lawsuit is in the discovery stage, and attorneys plan to collect Dr. Hansen’s deposition soon, said Eric Deters, a spokesman for Deters Law, a law firm based in Independence, Ky., that is representing the patient.

“The crux is that he performs unnecessary pain procedures and forces you to get an unnecessary procedure before giving you your medication,” Mr. Deters said.

However, Dr. Hansen’s and Mr. Deters’ history together includes a recent riff, according to an August 2021 lawsuit filed by Dr. Hansen against the law firm. Dr. Hansen was a former medical expert in cases for Deters and Associates, but the relationship turned sour when attorneys believed Dr. Hansen was retained as an expert in a case against their clients, according to Dr. Hansen’s suit. Dr. Hansen claims that as retribution, Deters and Associates issued a medical malpractice lawsuit against him in 2020, even though attorneys allegedly knew the statute of limitations had run out. A trial court dismissed the 2020 lawsuit against Dr. Hansen as being untimely filed. Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit alleges wrongful use of civil proceedings and requests compensatory, punitive damages and court costs from the law firm.

The law firm has faced trouble in the past. In August 2021, the Ohio Supreme Court ordered that Mr. Deters pay a $6,500 fine for engaging in the unauthorized practice of law. Mr. Deters’ Kentucky law license has been suspended since 2013 for ethics infractions, according to court records. He retired from law in 2014 and now acts as a spokesperson and office manager for the law firm. The fine resulted from legal advice given by Mr. Deters to two clients at the law firm, according to the Ohio Supreme Court decision.

As for the CVS lawsuit, an upcoming hearing will determine whether the federal court issues a permanent injunction against CVS’s actions. CVS officials have not said whether they will fight the temporary restraining order or the withdrawal of their prescription ban against Dr. Hansen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In an Aug. 11 decision, District Court Judge William Bertelsman ordered CVS to stop refusing prescriptions written by Kendall E. Hansen, MD. Judge Bertelsman ruled that Dr. Hansen is likely to succeed in his claim that CVS barred his prescriptions without evidence that he violated any law or professional protocol. The restraining order will remain in place while Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit against CVS Pharmacy proceeds.

Ronald W. Chapman II, an attorney representing Dr. Hansen, said the order is groundbreaking and that, to his knowledge, it’s the first time a federal court has overturned a pharmacy’s decision to block a prescriber.

“We believe that CVS’ decision was based solely on algorithms they use to analyze prescriber practices and not an any individual review of patient records,” Mr. Chapman said. “In fact, we invited CVS to come out to Dr. Hansen’s practice and look at how he was treating patients and ensure things were compliant, but they refused. Instead, they had a phone call with him then cut his patients off.”

Michael DeAngelis, a spokesman for CVS, said the court’s order illustrates the proverbial rock and hard place that pharmacies are placed between in the country’s fight against the misuse of prescription opioids.

“It is alleged in many lawsuits that pharmacies fill too many opioid prescriptions and should operate programs that use data to block prescriptions written by some doctors,” Mr. DeAngelis told this news organization. “And yet other lawsuits, including this one, argue that we should not operate programs that may block prescriptions. Such contradictions are grossly unfair to the pharmacy profession.”

Mr. DeAngelis declined to comment about Dr. Hansen’s claims or specify what led CVS to refuse his prescriptions.

Dr. Hansen declined to comment for this story through his attorney.

Dr. Hansen is no stranger to the spotlight. The Northern Kentucky pain doctor made headlines in 2012 when two of his horses, Fast and Accurate, and Hansen, ran in the Kentucky Derby. In February 2019, he drew media attention when his practice, Interventional Pain Specialists in Crestview Hills, Ky., was raided by federal agents. Dr. Hansen owns and operates the facility, which serves patients in Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.

The search yielded no findings, and no charges were filed, according to Mr. Chapman. Scott Hardcorn, director of the Northern Kentucky Drug Strike Force, confirmed that his agency assisted in the operation but said he was unaware of the outcome and that his officers generated no reports from the investigation. A spokesperson for the Drug Enforcement Administration would not comment about the investigation and directed a reporter for this news organization to the DEA website where enforcement actions are listed. No records or actions against Dr. Hansen can be found.

The CVS complaint stems from actions taken by the pharmacy against Dr. Hansen earlier this year. In June, a pharmacy representative allegedly contacted Dr. Hansen by phone and asked him questions about his practice and his prescribing practices, according to his lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky. During the call, the representative did not inform Dr. Hansen that any of his prescriptions were in question or were suspected of being medically unnecessary, the complaint alleges.

On July 28, 2021, CVS sent Dr. Hansen a letter announcing that its pharmacies would no longer be honoring his prescriptions. The letter, entered as an exhibit in the lawsuit, states that CVS contacted Dr. Hansen twice in 2021 about his prescribing practices, once in May and again in June.

“Despite our attempts to resolve the concerns with your controlled substance prescribing patterns, these concerns persist,” Kahra Lutkiewicz, director of CVS’ retail pharmacy professional practice, wrote in the letter. “Thus, we are writing to inform you that effective Aug. 5, 2021, CVS/pharmacy stores will no longer be able to fill prescriptions that you write for controlled substances. We take our compliance obligations very seriously, and after careful consideration, find it necessary to take this action.”

The letter does not explain the details behind CVS’ concerns.

Dr. Hansen sued CVS on Aug. 4 for tortious interference with a business relationship and defamation, among other claims. His complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen and his patients will suffer irreparable injury if the prescription decision stands. More than 250 of Dr. Hansen’s patients use CVS pharmacies for their prescriptions, and some are locked into using the pharmacy because of insurance contracts, Mr. Chapman said.

“There really is nowhere else for these patients to go,” Mr. Chapman said. “They would have to go to a new doctor and establish a new relationship, and obviously that has devastating consequences when we’re talking about people who need their medication.”

CVS has not yet issued a written response to the lawsuit. In his order, Judge Bertelsman stated that a preliminary conference was held in which all parties were represented and stated their positions to the judge.

“Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims that defendant has interfered with plaintiffs’ relationships with their patients by refusing to fill prescriptions written by plaintiffs, and defendant has done so without evidence that plaintiffs have violated any law or professional protocol related to such prescriptions,” Judge Bertelsman wrote. “The balance of the hardships between the parties weighs in favor of issuing a temporary restraining order inasmuch as defendant’s actions pose a threat to plaintiffs’ professional reputation and livelihood and ... because plaintiffs’ patients’ medical care is implicated by defendant’s actions, the public interest weighs in favor of issuance of the temporary restraining order.”

Dr. Hansen is currently embroiled in several other legal battles as both a plaintiff and a defendant.

In 2019, a patient sued him for negligence and fraud for allegedly performing medically unnecessary and excessive injection therapy. The suit claims the patient was required to undergo injection therapy on a continuing basis in order to receive her narcotic pain medication, according to the lawsuit filed in Kenton Circuit Court. The complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen made false representations to the patient and to her insurers that the injections were necessary for the treatment of the patient’s chronic pain.

The federal government is not involved in the case.

The negligence lawsuit is in the discovery stage, and attorneys plan to collect Dr. Hansen’s deposition soon, said Eric Deters, a spokesman for Deters Law, a law firm based in Independence, Ky., that is representing the patient.

“The crux is that he performs unnecessary pain procedures and forces you to get an unnecessary procedure before giving you your medication,” Mr. Deters said.

However, Dr. Hansen’s and Mr. Deters’ history together includes a recent riff, according to an August 2021 lawsuit filed by Dr. Hansen against the law firm. Dr. Hansen was a former medical expert in cases for Deters and Associates, but the relationship turned sour when attorneys believed Dr. Hansen was retained as an expert in a case against their clients, according to Dr. Hansen’s suit. Dr. Hansen claims that as retribution, Deters and Associates issued a medical malpractice lawsuit against him in 2020, even though attorneys allegedly knew the statute of limitations had run out. A trial court dismissed the 2020 lawsuit against Dr. Hansen as being untimely filed. Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit alleges wrongful use of civil proceedings and requests compensatory, punitive damages and court costs from the law firm.

The law firm has faced trouble in the past. In August 2021, the Ohio Supreme Court ordered that Mr. Deters pay a $6,500 fine for engaging in the unauthorized practice of law. Mr. Deters’ Kentucky law license has been suspended since 2013 for ethics infractions, according to court records. He retired from law in 2014 and now acts as a spokesperson and office manager for the law firm. The fine resulted from legal advice given by Mr. Deters to two clients at the law firm, according to the Ohio Supreme Court decision.

As for the CVS lawsuit, an upcoming hearing will determine whether the federal court issues a permanent injunction against CVS’s actions. CVS officials have not said whether they will fight the temporary restraining order or the withdrawal of their prescription ban against Dr. Hansen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In an Aug. 11 decision, District Court Judge William Bertelsman ordered CVS to stop refusing prescriptions written by Kendall E. Hansen, MD. Judge Bertelsman ruled that Dr. Hansen is likely to succeed in his claim that CVS barred his prescriptions without evidence that he violated any law or professional protocol. The restraining order will remain in place while Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit against CVS Pharmacy proceeds.

Ronald W. Chapman II, an attorney representing Dr. Hansen, said the order is groundbreaking and that, to his knowledge, it’s the first time a federal court has overturned a pharmacy’s decision to block a prescriber.

“We believe that CVS’ decision was based solely on algorithms they use to analyze prescriber practices and not an any individual review of patient records,” Mr. Chapman said. “In fact, we invited CVS to come out to Dr. Hansen’s practice and look at how he was treating patients and ensure things were compliant, but they refused. Instead, they had a phone call with him then cut his patients off.”

Michael DeAngelis, a spokesman for CVS, said the court’s order illustrates the proverbial rock and hard place that pharmacies are placed between in the country’s fight against the misuse of prescription opioids.

“It is alleged in many lawsuits that pharmacies fill too many opioid prescriptions and should operate programs that use data to block prescriptions written by some doctors,” Mr. DeAngelis told this news organization. “And yet other lawsuits, including this one, argue that we should not operate programs that may block prescriptions. Such contradictions are grossly unfair to the pharmacy profession.”

Mr. DeAngelis declined to comment about Dr. Hansen’s claims or specify what led CVS to refuse his prescriptions.

Dr. Hansen declined to comment for this story through his attorney.

Dr. Hansen is no stranger to the spotlight. The Northern Kentucky pain doctor made headlines in 2012 when two of his horses, Fast and Accurate, and Hansen, ran in the Kentucky Derby. In February 2019, he drew media attention when his practice, Interventional Pain Specialists in Crestview Hills, Ky., was raided by federal agents. Dr. Hansen owns and operates the facility, which serves patients in Kentucky, Ohio, and Indiana.

The search yielded no findings, and no charges were filed, according to Mr. Chapman. Scott Hardcorn, director of the Northern Kentucky Drug Strike Force, confirmed that his agency assisted in the operation but said he was unaware of the outcome and that his officers generated no reports from the investigation. A spokesperson for the Drug Enforcement Administration would not comment about the investigation and directed a reporter for this news organization to the DEA website where enforcement actions are listed. No records or actions against Dr. Hansen can be found.

The CVS complaint stems from actions taken by the pharmacy against Dr. Hansen earlier this year. In June, a pharmacy representative allegedly contacted Dr. Hansen by phone and asked him questions about his practice and his prescribing practices, according to his lawsuit filed in U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Kentucky. During the call, the representative did not inform Dr. Hansen that any of his prescriptions were in question or were suspected of being medically unnecessary, the complaint alleges.

On July 28, 2021, CVS sent Dr. Hansen a letter announcing that its pharmacies would no longer be honoring his prescriptions. The letter, entered as an exhibit in the lawsuit, states that CVS contacted Dr. Hansen twice in 2021 about his prescribing practices, once in May and again in June.

“Despite our attempts to resolve the concerns with your controlled substance prescribing patterns, these concerns persist,” Kahra Lutkiewicz, director of CVS’ retail pharmacy professional practice, wrote in the letter. “Thus, we are writing to inform you that effective Aug. 5, 2021, CVS/pharmacy stores will no longer be able to fill prescriptions that you write for controlled substances. We take our compliance obligations very seriously, and after careful consideration, find it necessary to take this action.”

The letter does not explain the details behind CVS’ concerns.

Dr. Hansen sued CVS on Aug. 4 for tortious interference with a business relationship and defamation, among other claims. His complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen and his patients will suffer irreparable injury if the prescription decision stands. More than 250 of Dr. Hansen’s patients use CVS pharmacies for their prescriptions, and some are locked into using the pharmacy because of insurance contracts, Mr. Chapman said.

“There really is nowhere else for these patients to go,” Mr. Chapman said. “They would have to go to a new doctor and establish a new relationship, and obviously that has devastating consequences when we’re talking about people who need their medication.”

CVS has not yet issued a written response to the lawsuit. In his order, Judge Bertelsman stated that a preliminary conference was held in which all parties were represented and stated their positions to the judge.

“Plaintiffs are likely to succeed on the merits of their claims that defendant has interfered with plaintiffs’ relationships with their patients by refusing to fill prescriptions written by plaintiffs, and defendant has done so without evidence that plaintiffs have violated any law or professional protocol related to such prescriptions,” Judge Bertelsman wrote. “The balance of the hardships between the parties weighs in favor of issuing a temporary restraining order inasmuch as defendant’s actions pose a threat to plaintiffs’ professional reputation and livelihood and ... because plaintiffs’ patients’ medical care is implicated by defendant’s actions, the public interest weighs in favor of issuance of the temporary restraining order.”

Dr. Hansen is currently embroiled in several other legal battles as both a plaintiff and a defendant.

In 2019, a patient sued him for negligence and fraud for allegedly performing medically unnecessary and excessive injection therapy. The suit claims the patient was required to undergo injection therapy on a continuing basis in order to receive her narcotic pain medication, according to the lawsuit filed in Kenton Circuit Court. The complaint alleges that Dr. Hansen made false representations to the patient and to her insurers that the injections were necessary for the treatment of the patient’s chronic pain.

The federal government is not involved in the case.

The negligence lawsuit is in the discovery stage, and attorneys plan to collect Dr. Hansen’s deposition soon, said Eric Deters, a spokesman for Deters Law, a law firm based in Independence, Ky., that is representing the patient.

“The crux is that he performs unnecessary pain procedures and forces you to get an unnecessary procedure before giving you your medication,” Mr. Deters said.

However, Dr. Hansen’s and Mr. Deters’ history together includes a recent riff, according to an August 2021 lawsuit filed by Dr. Hansen against the law firm. Dr. Hansen was a former medical expert in cases for Deters and Associates, but the relationship turned sour when attorneys believed Dr. Hansen was retained as an expert in a case against their clients, according to Dr. Hansen’s suit. Dr. Hansen claims that as retribution, Deters and Associates issued a medical malpractice lawsuit against him in 2020, even though attorneys allegedly knew the statute of limitations had run out. A trial court dismissed the 2020 lawsuit against Dr. Hansen as being untimely filed. Dr. Hansen’s lawsuit alleges wrongful use of civil proceedings and requests compensatory, punitive damages and court costs from the law firm.

The law firm has faced trouble in the past. In August 2021, the Ohio Supreme Court ordered that Mr. Deters pay a $6,500 fine for engaging in the unauthorized practice of law. Mr. Deters’ Kentucky law license has been suspended since 2013 for ethics infractions, according to court records. He retired from law in 2014 and now acts as a spokesperson and office manager for the law firm. The fine resulted from legal advice given by Mr. Deters to two clients at the law firm, according to the Ohio Supreme Court decision.

As for the CVS lawsuit, an upcoming hearing will determine whether the federal court issues a permanent injunction against CVS’s actions. CVS officials have not said whether they will fight the temporary restraining order or the withdrawal of their prescription ban against Dr. Hansen.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mediterranean diet slows progression of atherosclerosis in CHD

For patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), following a Mediterranean diet is more effective in reducing progression of atherosclerosis than following a low-fat diet, according to new data from the CORDIOPREV randomized, controlled trial.

“The current study is, to our knowledge, the first to establish an effective dietary strategy for secondary cardiovascular prevention, reinforcing the fact that the Mediterranean diet rich in extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) could prevent the progression of atherosclerosis,” the study team said.

The data also show that patients with a higher atherosclerotic burden might benefit the most from the Mediterranean diet.

The study was published online Aug. 10, 2021, in Stroke.

Mediterranean or low fat?

“It is well established that lifestyle and dietary habits powerfully affect cardiovascular risk,” study investigator Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, PhD, with Reina Sofia University Hospital/University of Cordoba (Spain), told this news organization.

“The effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in reducing cardiovascular risk has been seen in primary prevention. However, currently there is no consensus about a recommended dietary model for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease,” she said.

The Coronary Diet Intervention With Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention (CORDIOPREV) study is an ongoing prospective study comparing the effects of two healthy diets for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 1002 patients.

The comparative effect of the diets in reducing CVD risk, assessed by quantification of intima-media thickness of the common carotid arteries (IMT-CC), is a key secondary endpoint of the study.

During the study, half of the patients follow a Mediterranean diet rich in EVOO, fruit and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and nuts. The other half follow a diet low in fat and rich in complex carbohydrates.

A total of 939 participants (459 in the low-fat diet group and 480 in the Mediterranean diet group) completed IMT-CC evaluation at baseline, and 809 (377 and 432, respectively) completed the IMT-CC evaluation at 5 years; 731 (335 and 396, respectively) did so at 7 years.

The Mediterranean diet significantly decreased IMT-CC both after 5 years (–0.027; P < .001) and after 7 years (–0.031 mm; P < .001), relative to baseline. In contrast, the low-fat diet did not exert any change on IMT-CC after 5 or 7 years, the researchers report.

The higher the IMT-CC at baseline, the greater the reduction in this parameter.

The Mediterranean diet also produced a greater decrease in IMT-CC and carotid plaque maximum height, compared with the low-fat diet throughout follow-up.

There were no between-group differences in carotid plaque numbers during follow-up.

“Our findings, in addition to reinforcing the clinical benefits of the Mediterranean diet, provide a beneficial dietary strategy as a clinical and therapeutic tool that could reduce the high cardiovascular recurrence in the context of secondary prevention,” Dr. Yubero-Serrano said in an interview.

Earlier data from CORDIOPREV showed that, after 1 year of eating a Mediterranean diet, compared with the low-fat diet, endothelial function was improved among patients with CHD, even those with type 2 diabetes, which was associated with a better balance of vascular homeostasis.

The Mediterranean diet may also modulate the lipid profile, particularly by increasing HDL cholesterol levels. The anti-inflammatory capacity of the Mediterranean diet could be another factor that contributes to reducing the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers say.

Important study

Reached for comment, Alan Rozanski, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said: “We know very well that lifestyle factors, diet, and exercise in particular are extremely important in promoting health, vitality, and decreasing risk for chronic diseases, including heart attack and stroke.

“But a lot of the studies depend on epidemiological work. Until now, we haven’t had important prospective studies evaluating different kinds of dietary approaches and how they affect carotid intimal thickening assessments that we can do by ultrasound. So having this kind of imaging study which shows that diet can halt progression of atherosclerosis is important,” said Dr. Rozanski.

“Changing one’s diet is extremely important and potentially beneficial in many ways, and being able to say to a patient with atherosclerosis that we have data that shows you can halt the progression of the disease can be extraordinarily encouraging to many patients,” he noted.

“When people have disease, they very often gravitate toward drugs, but continuing to emphasize lifestyle changes in these people is extremely important,” he added.

The CORDIOPREV study was supported by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero. Dr. Yubero-Serrano and Dr. Rozanski disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), following a Mediterranean diet is more effective in reducing progression of atherosclerosis than following a low-fat diet, according to new data from the CORDIOPREV randomized, controlled trial.

“The current study is, to our knowledge, the first to establish an effective dietary strategy for secondary cardiovascular prevention, reinforcing the fact that the Mediterranean diet rich in extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) could prevent the progression of atherosclerosis,” the study team said.

The data also show that patients with a higher atherosclerotic burden might benefit the most from the Mediterranean diet.

The study was published online Aug. 10, 2021, in Stroke.

Mediterranean or low fat?

“It is well established that lifestyle and dietary habits powerfully affect cardiovascular risk,” study investigator Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, PhD, with Reina Sofia University Hospital/University of Cordoba (Spain), told this news organization.

“The effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in reducing cardiovascular risk has been seen in primary prevention. However, currently there is no consensus about a recommended dietary model for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease,” she said.

The Coronary Diet Intervention With Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention (CORDIOPREV) study is an ongoing prospective study comparing the effects of two healthy diets for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 1002 patients.

The comparative effect of the diets in reducing CVD risk, assessed by quantification of intima-media thickness of the common carotid arteries (IMT-CC), is a key secondary endpoint of the study.

During the study, half of the patients follow a Mediterranean diet rich in EVOO, fruit and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and nuts. The other half follow a diet low in fat and rich in complex carbohydrates.

A total of 939 participants (459 in the low-fat diet group and 480 in the Mediterranean diet group) completed IMT-CC evaluation at baseline, and 809 (377 and 432, respectively) completed the IMT-CC evaluation at 5 years; 731 (335 and 396, respectively) did so at 7 years.

The Mediterranean diet significantly decreased IMT-CC both after 5 years (–0.027; P < .001) and after 7 years (–0.031 mm; P < .001), relative to baseline. In contrast, the low-fat diet did not exert any change on IMT-CC after 5 or 7 years, the researchers report.

The higher the IMT-CC at baseline, the greater the reduction in this parameter.

The Mediterranean diet also produced a greater decrease in IMT-CC and carotid plaque maximum height, compared with the low-fat diet throughout follow-up.

There were no between-group differences in carotid plaque numbers during follow-up.

“Our findings, in addition to reinforcing the clinical benefits of the Mediterranean diet, provide a beneficial dietary strategy as a clinical and therapeutic tool that could reduce the high cardiovascular recurrence in the context of secondary prevention,” Dr. Yubero-Serrano said in an interview.

Earlier data from CORDIOPREV showed that, after 1 year of eating a Mediterranean diet, compared with the low-fat diet, endothelial function was improved among patients with CHD, even those with type 2 diabetes, which was associated with a better balance of vascular homeostasis.

The Mediterranean diet may also modulate the lipid profile, particularly by increasing HDL cholesterol levels. The anti-inflammatory capacity of the Mediterranean diet could be another factor that contributes to reducing the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers say.

Important study

Reached for comment, Alan Rozanski, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said: “We know very well that lifestyle factors, diet, and exercise in particular are extremely important in promoting health, vitality, and decreasing risk for chronic diseases, including heart attack and stroke.

“But a lot of the studies depend on epidemiological work. Until now, we haven’t had important prospective studies evaluating different kinds of dietary approaches and how they affect carotid intimal thickening assessments that we can do by ultrasound. So having this kind of imaging study which shows that diet can halt progression of atherosclerosis is important,” said Dr. Rozanski.

“Changing one’s diet is extremely important and potentially beneficial in many ways, and being able to say to a patient with atherosclerosis that we have data that shows you can halt the progression of the disease can be extraordinarily encouraging to many patients,” he noted.

“When people have disease, they very often gravitate toward drugs, but continuing to emphasize lifestyle changes in these people is extremely important,” he added.

The CORDIOPREV study was supported by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero. Dr. Yubero-Serrano and Dr. Rozanski disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

For patients with coronary heart disease (CHD), following a Mediterranean diet is more effective in reducing progression of atherosclerosis than following a low-fat diet, according to new data from the CORDIOPREV randomized, controlled trial.

“The current study is, to our knowledge, the first to establish an effective dietary strategy for secondary cardiovascular prevention, reinforcing the fact that the Mediterranean diet rich in extra virgin olive oil (EVOO) could prevent the progression of atherosclerosis,” the study team said.

The data also show that patients with a higher atherosclerotic burden might benefit the most from the Mediterranean diet.

The study was published online Aug. 10, 2021, in Stroke.

Mediterranean or low fat?

“It is well established that lifestyle and dietary habits powerfully affect cardiovascular risk,” study investigator Elena M. Yubero-Serrano, PhD, with Reina Sofia University Hospital/University of Cordoba (Spain), told this news organization.

“The effectiveness of the Mediterranean diet in reducing cardiovascular risk has been seen in primary prevention. However, currently there is no consensus about a recommended dietary model for the secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease,” she said.

The Coronary Diet Intervention With Olive Oil and Cardiovascular Prevention (CORDIOPREV) study is an ongoing prospective study comparing the effects of two healthy diets for secondary prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) in 1002 patients.

The comparative effect of the diets in reducing CVD risk, assessed by quantification of intima-media thickness of the common carotid arteries (IMT-CC), is a key secondary endpoint of the study.

During the study, half of the patients follow a Mediterranean diet rich in EVOO, fruit and vegetables, whole grains, fish, and nuts. The other half follow a diet low in fat and rich in complex carbohydrates.

A total of 939 participants (459 in the low-fat diet group and 480 in the Mediterranean diet group) completed IMT-CC evaluation at baseline, and 809 (377 and 432, respectively) completed the IMT-CC evaluation at 5 years; 731 (335 and 396, respectively) did so at 7 years.

The Mediterranean diet significantly decreased IMT-CC both after 5 years (–0.027; P < .001) and after 7 years (–0.031 mm; P < .001), relative to baseline. In contrast, the low-fat diet did not exert any change on IMT-CC after 5 or 7 years, the researchers report.

The higher the IMT-CC at baseline, the greater the reduction in this parameter.

The Mediterranean diet also produced a greater decrease in IMT-CC and carotid plaque maximum height, compared with the low-fat diet throughout follow-up.

There were no between-group differences in carotid plaque numbers during follow-up.

“Our findings, in addition to reinforcing the clinical benefits of the Mediterranean diet, provide a beneficial dietary strategy as a clinical and therapeutic tool that could reduce the high cardiovascular recurrence in the context of secondary prevention,” Dr. Yubero-Serrano said in an interview.

Earlier data from CORDIOPREV showed that, after 1 year of eating a Mediterranean diet, compared with the low-fat diet, endothelial function was improved among patients with CHD, even those with type 2 diabetes, which was associated with a better balance of vascular homeostasis.

The Mediterranean diet may also modulate the lipid profile, particularly by increasing HDL cholesterol levels. The anti-inflammatory capacity of the Mediterranean diet could be another factor that contributes to reducing the progression of atherosclerosis, the researchers say.

Important study

Reached for comment, Alan Rozanski, MD, professor of medicine, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and cardiologist at Mount Sinai Morningside, New York, said: “We know very well that lifestyle factors, diet, and exercise in particular are extremely important in promoting health, vitality, and decreasing risk for chronic diseases, including heart attack and stroke.

“But a lot of the studies depend on epidemiological work. Until now, we haven’t had important prospective studies evaluating different kinds of dietary approaches and how they affect carotid intimal thickening assessments that we can do by ultrasound. So having this kind of imaging study which shows that diet can halt progression of atherosclerosis is important,” said Dr. Rozanski.

“Changing one’s diet is extremely important and potentially beneficial in many ways, and being able to say to a patient with atherosclerosis that we have data that shows you can halt the progression of the disease can be extraordinarily encouraging to many patients,” he noted.

“When people have disease, they very often gravitate toward drugs, but continuing to emphasize lifestyle changes in these people is extremely important,” he added.

The CORDIOPREV study was supported by the Fundación Patrimonio Comunal Olivarero. Dr. Yubero-Serrano and Dr. Rozanski disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Cutaneous Chaetomium globosum Infection in a Vedolizumab-Treated Patient

To the Editor:

Broader availability and utilization of novel biologic treatments has heralded the emergence of unusual infections, including skin and soft tissue infections. These unusual infections may not be seen in clinical trials due to their overall rare incidence. In modern society, exposure to unusual pathogens can occur in locations far from their natural habitat.1 Tissue culture remains the gold standard, as histopathology and smears may not identify the organisms. Tissue culture of these less-common pathogens is challenging and may require multiple samples and specialized laboratory evaluations.2 In some cases, a skin biopsy with histopathologic examination is an efficient means to confirm or exclude a dermatologic manifestation of an inflammatory disease. This information can quickly change the course of treatment, especially for those on immunosuppressive medications.3 We report a case of unusual cutaneous infection with Chaetomium globosum in a patient concomitantly treated with vedolizumab, a gut-specific integrin inhibitor, alongside traditional immunosuppressive therapy.

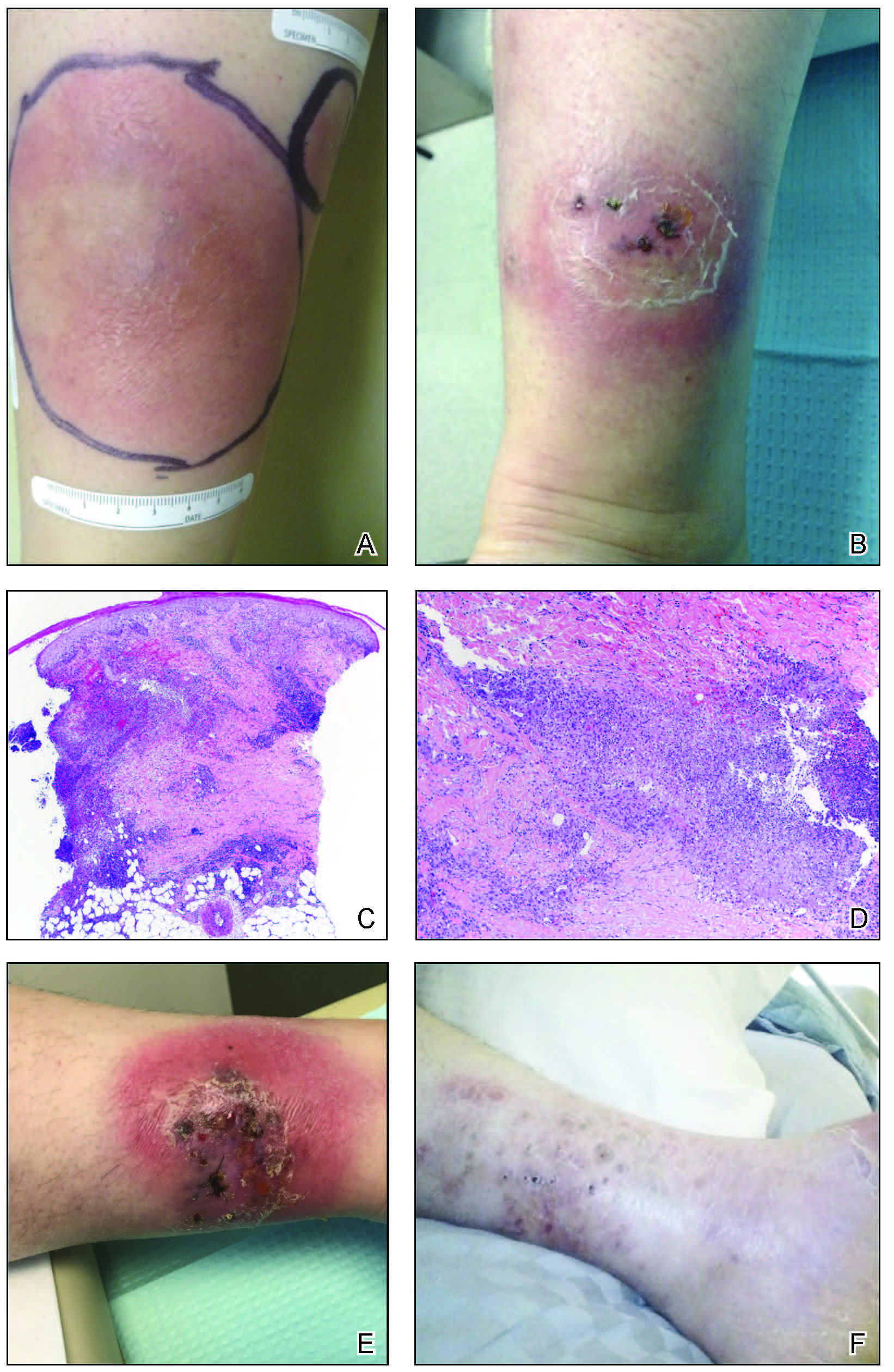

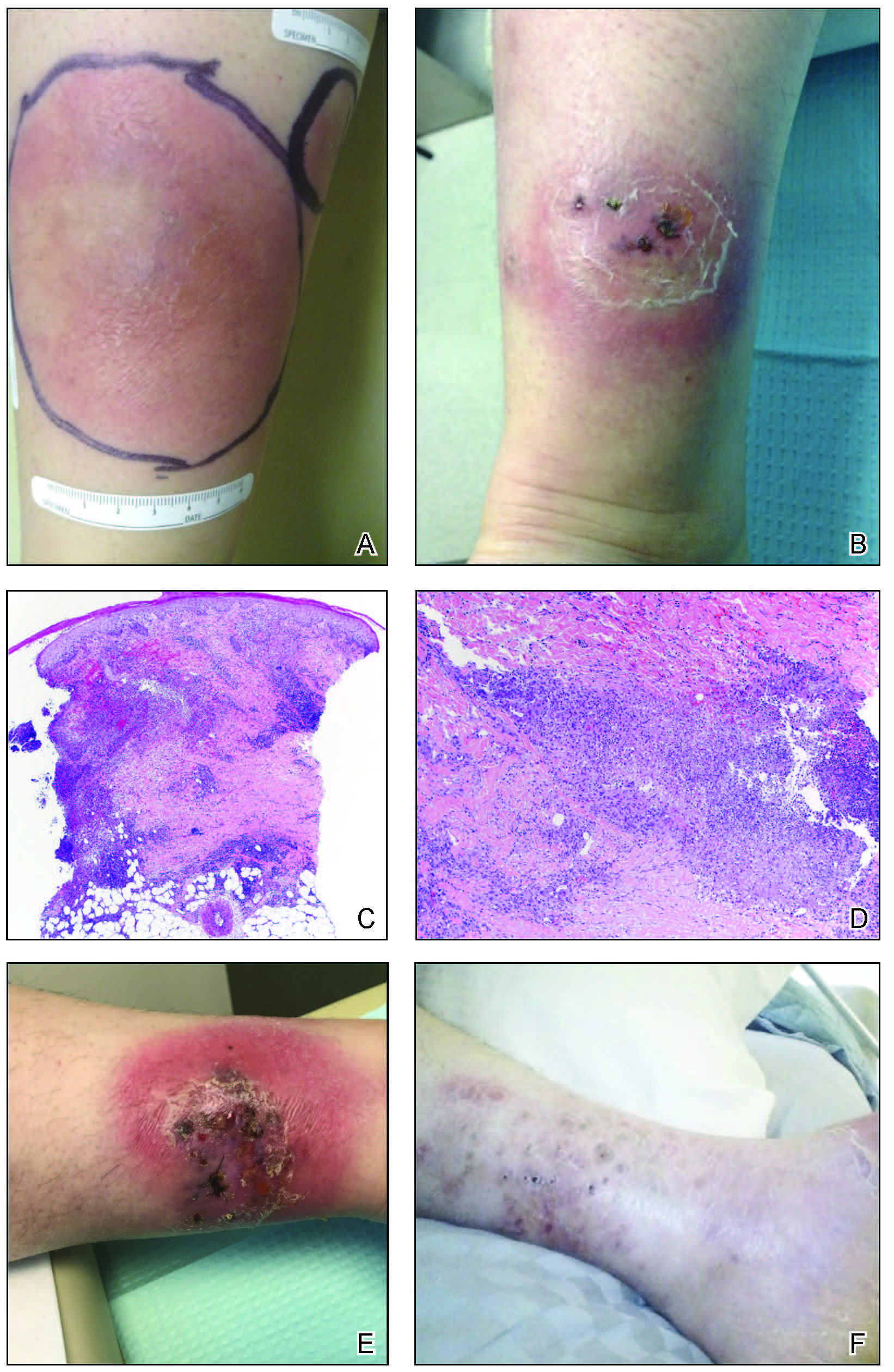

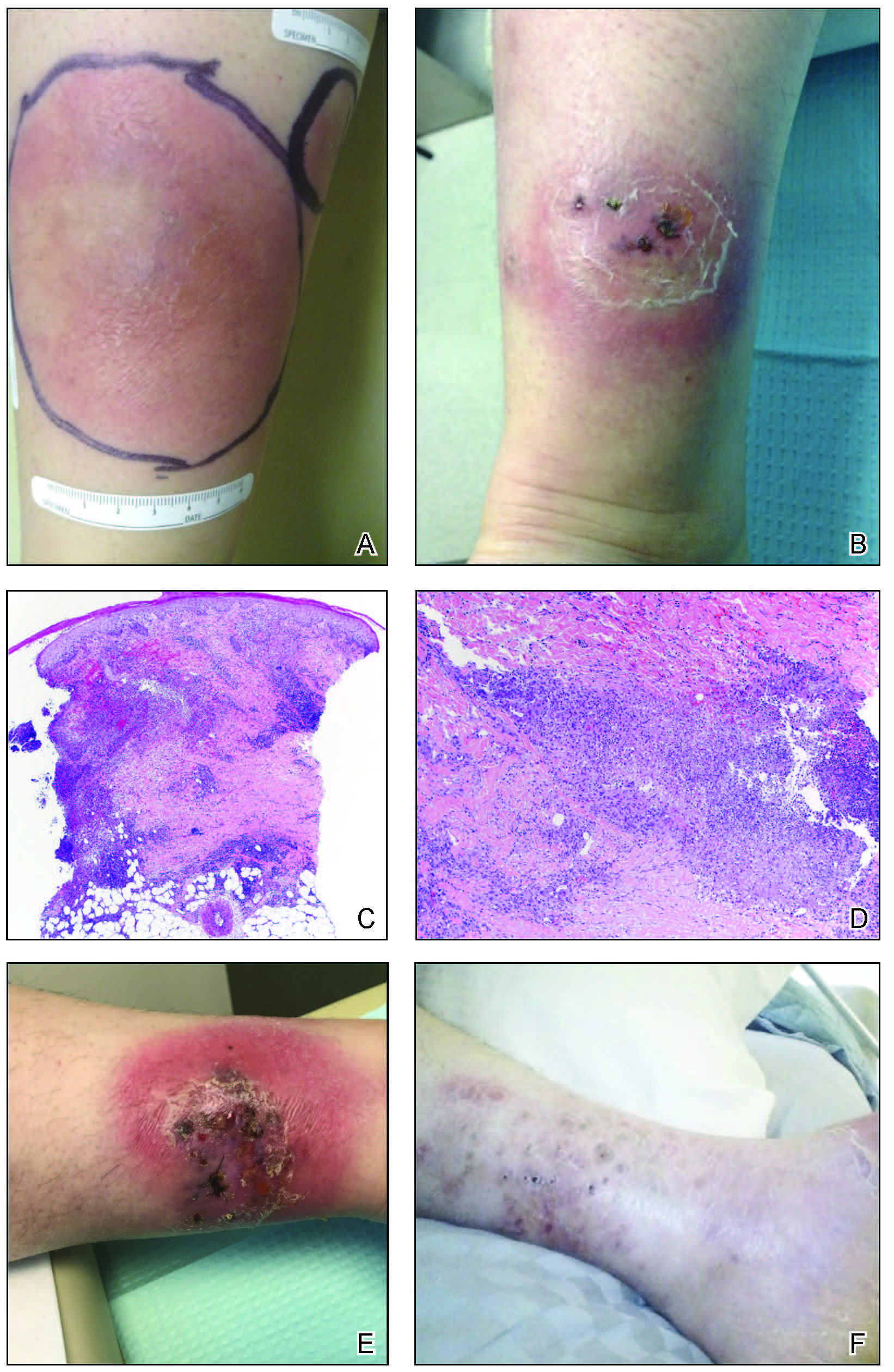

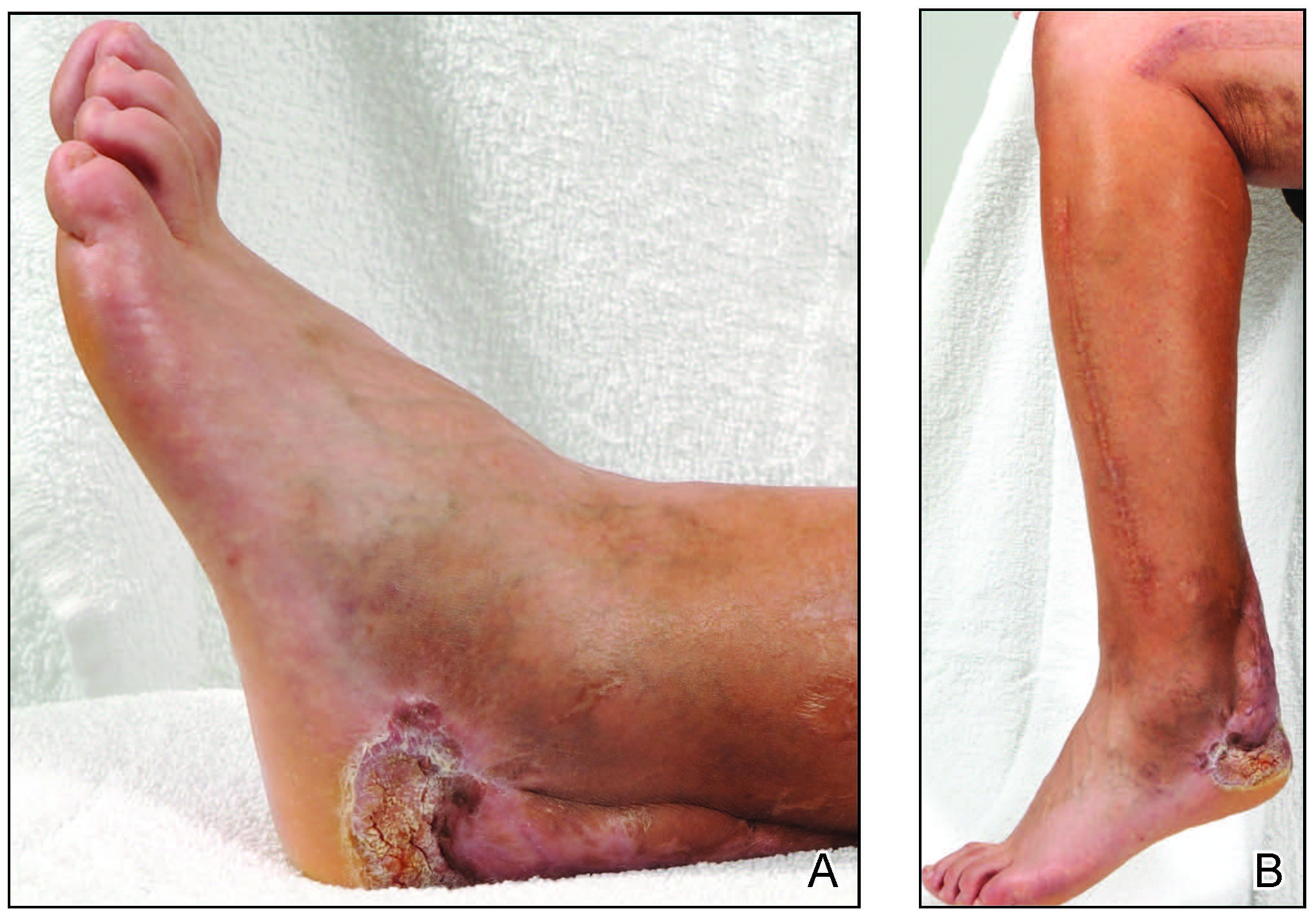

A 33-year-old woman with Crohn disease on vedolizumab and mercaptopurine was referred to the dermatology clinic with firm, tender, erythematous lesions on the legs of 1 month’s duration (Figure, A). She had a history of inflammatory bowel disease with perianal fistula, sacroiliitis, uveitis, guttate psoriasis, and erythema nodosum. She denied recent medication changes, foreign travel, swimming in freshwater or a hot tub, chills, fever, malaise, night sweats, and weight loss. Physical examination revealed several tender, indurated, erythematous plaques across the legs, ranging in size from 4 to 12 cm. The plaques had central hyperpigmentation, atrophy, and scant scale without ulceration, drainage, or pustules. The largest plaque demonstrated a well-defined area of central fluctuance. Prednisone (60 mg) with taper was initiated for presumed recurrence of erythema nodosum with close follow-up.

Five weeks later, most indurated plaques healed, leaving depressed scars; however, at 10 mg of prednisone she developed 2 additional nodules on the shin that, unlike earlier plaques, developed a central pustule and drained. The prednisone dose was increased to control the new areas and tapered thereafter to 20 mg daily. Despite the overall improvement, 2 plaques remained on the left side of the shin. Initially, erythema nodosum recurrence was considered, given the setting of inflammatory bowel disease and recent more classic presentation4; however, the disease progression and lack of response to standard treatment suggested an alternate pathology. Further history revealed that the patient had a pedicure 3 weeks prior to initial symptom onset. A swab was sent for routine bacterial culture at an outside clinic; no infectious agents were identified.

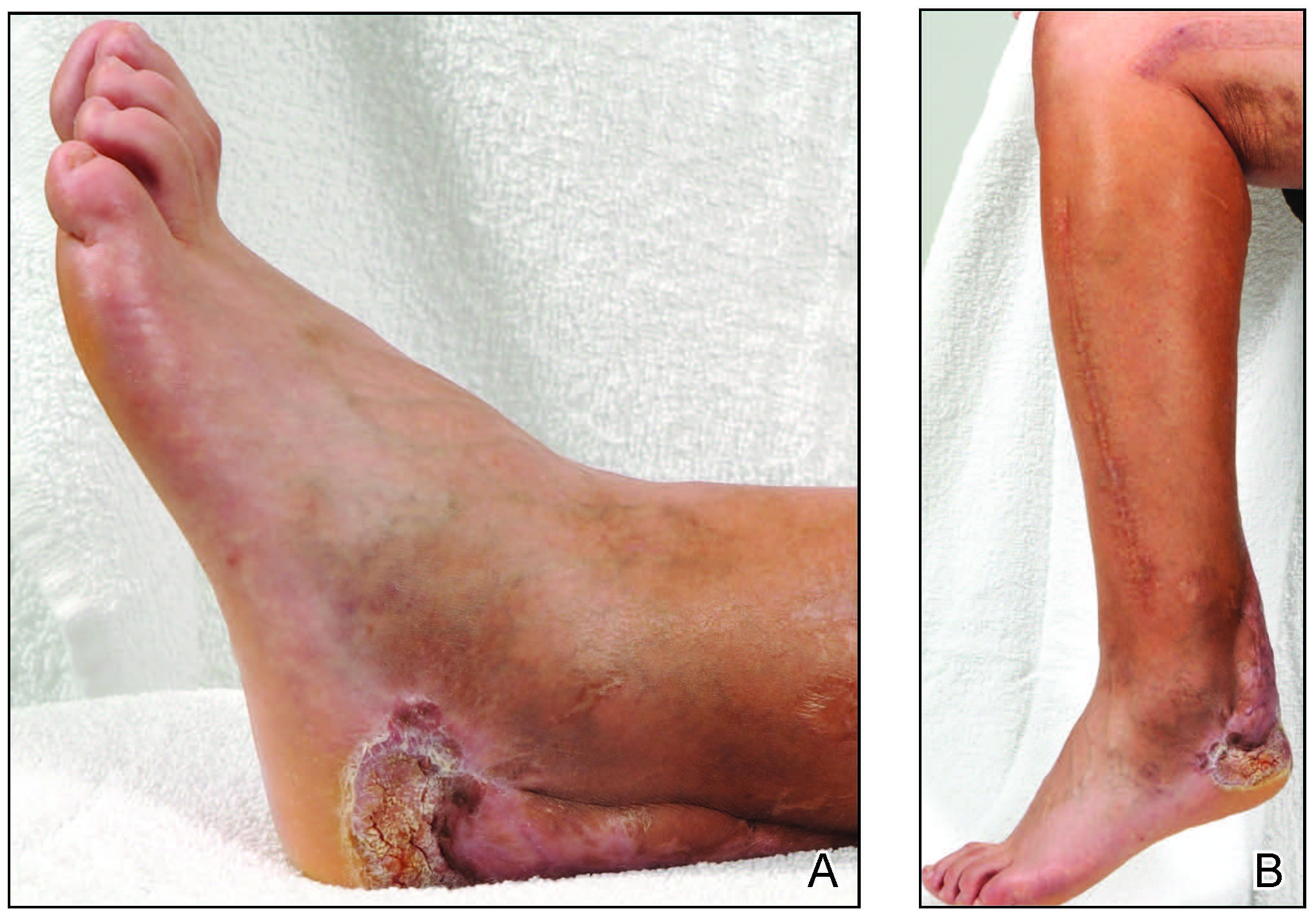

Three weeks later, the patient's condition had worsened again with increased edema, pain with standing, and more drainage (Figure, B). She did not report fevers or joint swelling. A punch biopsy was performed for tissue culture and histopathologic evaluation, which revealed granulomatous and suppurative inflammation and excluded erythema nodosum. Special stains for organisms were negative (Figure, C and D). Two weeks later, tissue culture began growing an unspecified mold. Mercaptopurine and prednisone were immediately discontinued. The patient remained on vedolizumab, started itraconazole (200 mg), and was referred to an infectious disease (ID) specialist. The sample was eventually identified as C globosum (Figure, E) at a specialized facility (University of Texas, San Antonio). Despite several weeks of itraconazole therapy, the patient developed edema surrounding the knee. Upon evaluation by orthopedics, the patient was diagnosed with reactive arthritis in the left knee and ankle. The knee fluid was drained, and cultures were negative. At recommendation of the ID physician, the itraconazole dosage was doubled given the limited clinical response. After several weeks at the increased dosage, she began to experience slow improvement (Figure, F). Because Chaetomium species infections are rare and have limited response to many antifungal agents,5 no standard treatment protocol was available. Initial recommendations for treatment were for 1 year, based on the experience and expertise of the ID physician. Treatment with itraconazole was continued for 10 months, at which point the patient chose to discontinue therapy prior to her follow-up appointments. The patient had no evidence of infection recurrence 2 months after discontinuing therapy.

In the expanding landscape of targeted biologic therapies for chronic inflammatory disease, physicians of various specialties are increasingly encountering unanticipated cutaneous eruptions and infections. Chaetomium is a dematiaceous mold found primarily in soil, water, decaying plants, paper, or dung. Based on its habitat, populations at risk for infection with Chaetomium species include farmers (plant and animal husbandry), children who play on the ground, and people with inadequate foot protection.1,2Chaetomium globosum has been identified in indoor environments, such as moldy rugs and mattresses. In one report, it was cultured from the environmental air in a bone marrow transplant patient’s room after the patient presented with delayed infection.6 Although human infection is uncommon, clinical isolation of Chaetomium species has occurred mainly in superficial samples from the skin, hair, nails, eyes, and respiratory tract.1 It been reported as a causative agent of onychomycosis in several immunocompetent patients7,8 but rarely is a cause of deep-skin infection. Chaetomium is thought to cause superficial infections, as it uses extracellular keratinases1 to degrade protective keratin structures, such as human nails. Infections in the brain, blood, and lymph nodes also have been noted but are quite rare. Deep skin infections present as painful papules and nodules to nonhealing ulcers that develop into inflammatory granulomas on the extremities.3 Local edema and yellow-brown crust often is present and fevers have been reported. Hyphae may be identified in skin biopsy.8 We posit that our patient may have been exposed to Chaetomium during her pedicure, as recirculating baths in nail salons have been a reported site of other infectious organisms, such as atypical mycobacteria.9

Vedolizumab is a humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody used in the treatment of ulcerative colitis and Crohn disease. It targets the α4β7 integrin, a specific modulator of gut-trafficking lymphocytes. In vedolizumab’s clinical trial for Crohn disease, there was no increased incidence of life-threatening, severe infection.10,11 Often, new biologic treatments are used with known immunosuppressive medications. Mercaptopurine and prednisone are implicated in infections; however, recovery from the immune suppression usually is seen at 1 month after discontinuation.12 Our patient continued to worsen for several weeks and required increased dosing of itraconazole, despite stopping both prednisone and mercaptopurine. It opens the question as to whether vedolizumab played a role in the recalcitrant disease.

This case illustrates the importance of a high index of suspicion for unusual infections in the setting of biologic therapy. An infectious etiology of a cutaneous eruption in an immunosuppressed patient should always be included in the differential diagnosis and actively pursued early on; tissue culture may shorten the treatment course and decrease severity of the disease. Although a direct link between the mechanism of action of vedolizumab and cutaneous infection is not clear, given the rare incidence of this infection, a report of such a case is important to the practicing clinician.