User login

Is the keto diet effective for refractory chronic migraine?

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Key clinical point: A 3-month ketogenic diet (KD) resulted in a reduction of painful symptoms of drug refractory chronic migraine.

Major finding: KD significantly reduced the number of migraine days/month from a median of 30 days to 7.5 days (P less than .0001), hours of migraine/day from a median of 24 hours to 5.5 hours (P less than .0016), and pain level at maximum value for 83% of participants that improved for 55% of them (P less than .0024). The median number of drugs taken in a month reduced from 30 to 6 doses.

Study details: This open-label, single-arm clinical trial assessed 38 patients with refractory chronic migraine who adopted a KD for 3 months.

Disclosures: No source of funding was declared. The authors declared no conflicts of interest.

Source: Bongiovanni D et al. Neurol Sci. 2021 Feb 1. doi: 10.1007/s10072-021-05078-5.

Galcanezumab may alleviate severity and symptoms of migraine

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Key clinical point: Galcanezumab reduces the frequency of migraine headache days and may also potentially decrease disabling non-pain symptoms on days when migraine is present in patients with episodic and chronic migraine.

Major finding: Galcanezumab doses of 120 and 240 mg were superior to placebo in reducing the number of monthly migraine days with nausea and/or vomiting in both episodic and chronic migraine studies (all P less than .001). Both doses of galcanezumab were associated with a significant reduction in migraine headache days with photophobia and phonophobia vs. placebo in episodic (P less than .001) and chronic (P less than .001 for galcanezumab 120 mg; P =.001 for galcanezumab 240 mg) migraine studies.

Study details: A post hoc analysis of phase 3 randomized clinical trials EVOLVE-1, EVOLVE-2, and REGAIN that included a total of 2,289 patients with episodic or chronic migraine with or without aura.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Eli Lilly and Company, Indianapolis, IN, USA. K Day, VL Stauffer, V Skljarevski, M Rettiganti, E Pearlman, and SK Aurora reported being current/former full-time employees and/or minor stockholders of Eli Lilly and Company. M Ament reported being a consultant and/or on speaker bureaus for Eli Lilly and Company and others.

Source: Ament M et al. J Headache Pain. 2021 Feb 6. doi: 10.1186/s10194-021-01215-9.

Lasmiditan demonstrates superior pain freedom at 2 hours in at least 2 of 3 migraine attacks

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Key clinical point: Lasmiditan is effective in the treatment of an acute migraine attack and demonstrates consistency of response across multiple migraine attacks

Major finding: Lasmiditan doses of 100 and 200 mg were superior to placebo for pain freedom at 2 hours during the first attack (odds ratio [OR], 3.8 and 4.6, respectively; P less than .001) and in at least 2 of 3 attacks (OR, 3.8 and 7.2, respectively; P less than .001). The incidence of severe adverse events was similar across treatment groups.

Study details: Findings are from CENTURION, a phase 3 study that randomly assigned patients with migraine with/without aura to either of 3 treatment groups for 4 attacks: lasmiditan 200 mg (n=536), lasmiditan 100 mg (n=539), or control (n=538).

Disclosures: The CENTURION study was sponsored by Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors including the lead author were full-time employees and minor stockholders at Eli Lilly and Company. Some authors reported receiving speaker fees and honorariums from different sources.

Source: Ashina M et al. Cephalalgia. 2021 Feb 4. doi: 10.1177/0333102421989232.

Hyperkeratotic Nummular Plaques on the Upper Trunk

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

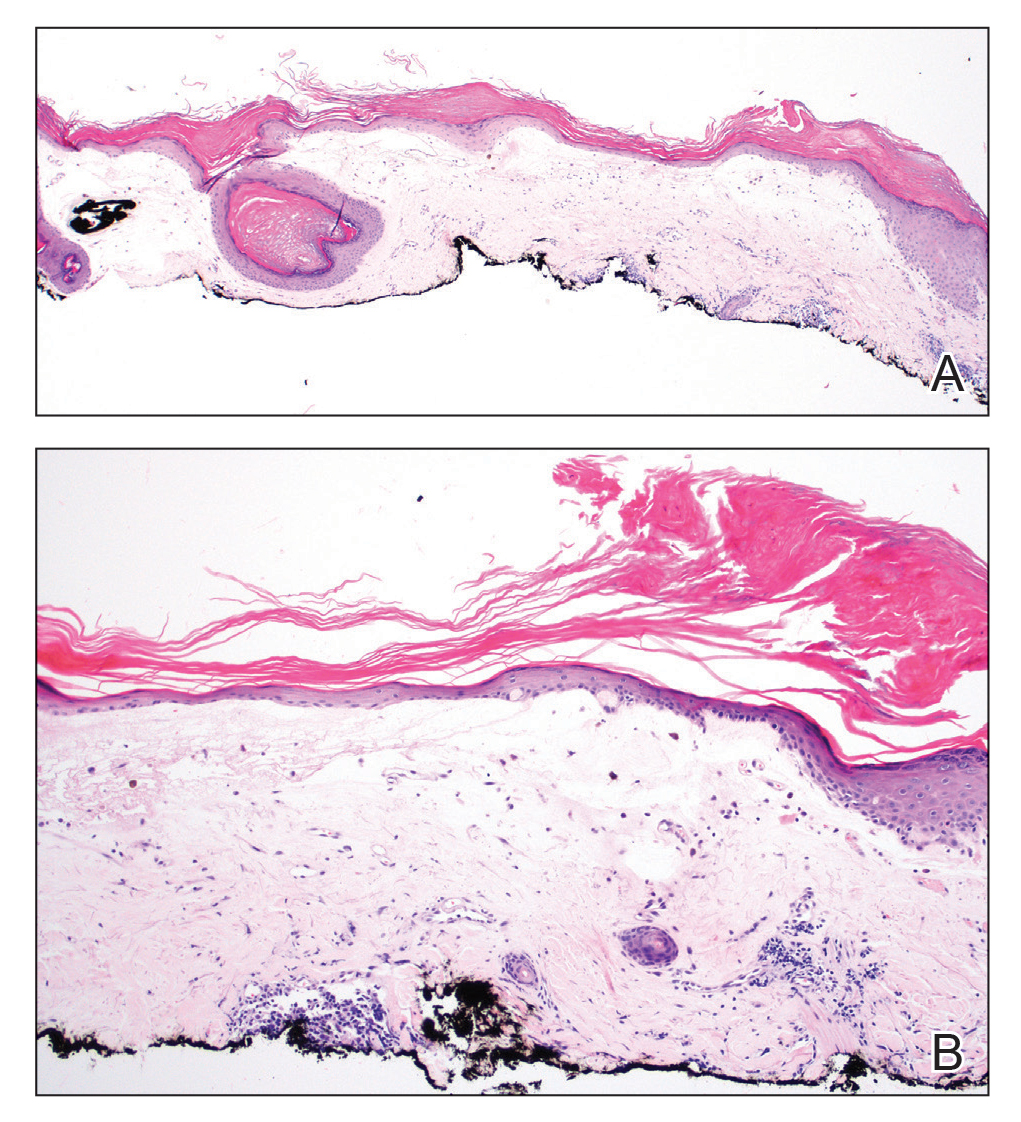

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

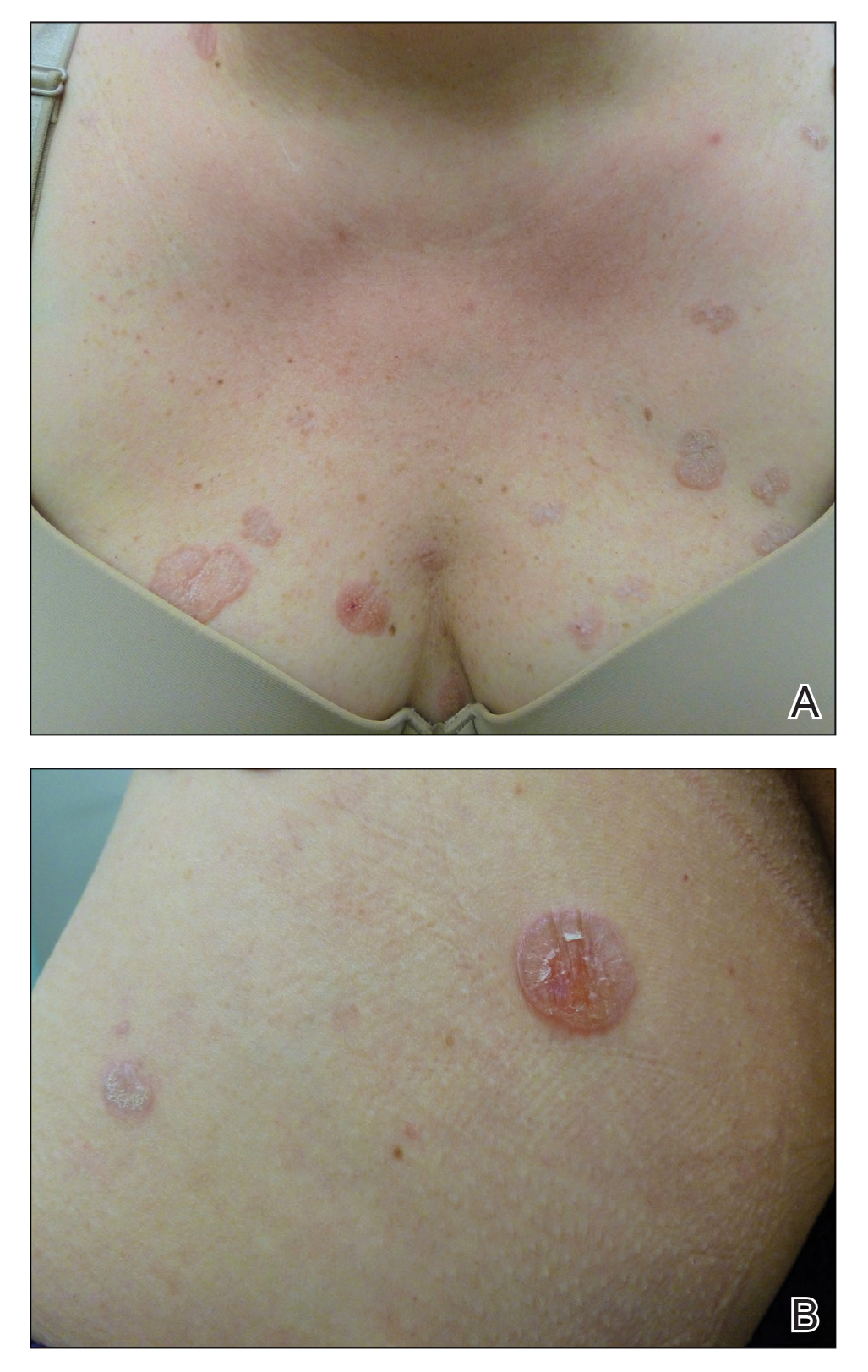

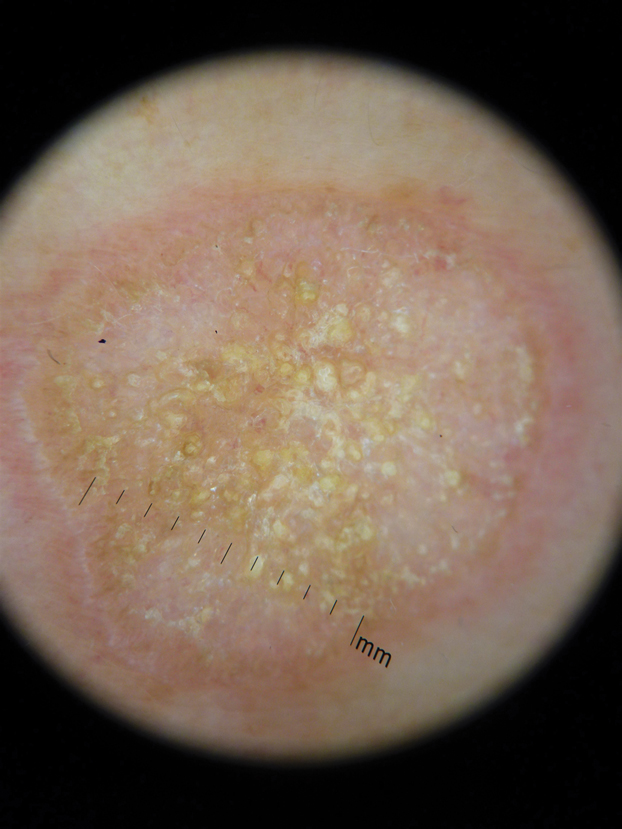

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

The Diagnosis: Extragenital Lichen Sclerosus Et Atrophicus

Histopathologic evaluation revealed hyperkeratosis, follicular plugging, epidermal atrophy, and homogenization of papillary dermal collagen with an underlying lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 1). Direct immunofluorescence of a plaque with a superimposed bulla was negative for deposition of C3, IgG, IgA, IgM, or fibrinogen. Accordingly, clinicopathologic correlation supported a diagnosis of extragenital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus (LSA). Of note, the patient's history of genital irritation was due to genital LSA that preceded the extragenital manifestations.

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is an inflammatory dermatosis that typically presents as atrophic white papules of the anogenital area that coalesce into pruritic plaques; the exact etiology remains to be elucidated, yet various circulating autoantibodies have been identified, suggesting a role for autoimmunity.1,2 Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus is more common in women than in men, with a bimodal peak in the age of onset affecting postmenopausal and prepubertal populations.1 In women, affected areas include the labia minora and majora, clitoris, perineum, and perianal skin; LSA spares the mucosal surfaces of the vagina and cervix.2 In men, uncircumscribed genital skin more commonly is affected. Involvement is localized to the foreskin and glans with occasional urethral involvement.2

In contrast, extragenital LSA tends to present as asymptomatic papules and plaques that develop atrophy with time, involving the back, shoulders, neck, chest, thighs, axillae, and flexural wrists2,3; an erythematous rim often is present,4 and hyperkeratosis with follicular plugging may be prominent.5 Our patient's case emphasizes the predilection of plaques for the chest and intermammary skin (Figure 2A). Approximately 15% of LSA cases have extragenital involvement, and extragenital-limited disease accounts for roughly 5% of cases.6,7 Unlike genital LSA, extragenital disease has not been associated with an increased risk for squamous cell carcinoma.1 Bullae formation within plaques of genital or extragenital LSA has been reported3,8 and is exemplified in our patient (Figure 2B). Intralesional bullae formation likely is due to a combination of internal and external factors, mainly the inability to withstand shear forces due to an atrophic epidermis with basal vacuolar injury overlying an edematous papillary dermis with altered collagen.8 Dermatoscopic findings may aid in recognizing extragenital LSA9,10; our patient's plaques demonstrated the characteristic findings of comedolike openings, structureless white areas, and pink borders (Figure 3).

The clinical differential diagnosis for well-demarcated, pink, scaly plaques is broad. Nummular eczema usually presents as coin-shaped eczematous plaques on the dorsal aspects of the hands or lower extremities, and histology shows epidermal spongiosis.11 Nummular eczema may be considered due to the striking round morphology of various plaques, yet our patient's presentation was better served by a consideration of several papulosquamous disorders.

Lichen planus (LP) presents as intensely pruritic, violaceous, polygonal, flat-topped papules with overlying reticular white lines, or Wickham striae, that favor the flexural wrists, lower back, and lower extremities. Lichen planus also may have oral and genital mucosal involvement. Similar to LSA, LP is more common in women and preferentially affects the postmenopausal population.12 Additionally, hypertrophic LP may obscure Wickham striae and mimic extragenital LSA; distinguishing features of hypertrophic LP are intense pruritus and a predilection for the shins. Histology is defined by orthohyperkeratosis, hypergranulosis, sawtooth acanthosis, and vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with Civatte bodies or dyskeratotic basal keratinocytes overlying a characteristic bandlike infiltrate of lymphocytes.12

Lichen simplex chronicus (LSC) is characterized by intense pruritus and presents as hyperkeratotic plaques with a predilection for accessible regions such as the posterior neck and extremities.13 The striking annular demarcation of this case makes LSC unlikely. Comparable to LSA and LP, LSC also may present with both genital and extragenital findings. Histology of LSC is characterized by irregular acanthosis or thickening of the epidermis with vertical streaking of collagen and vascular bundles of the papillary dermis.13

Subacute cutaneous lupus erythematosus (SCLE) is important to consider for a new papulosquamous eruption with a predilection for the sun-exposed skin of a middle-aged woman. The presence of papules on the volar wrist and history of genital irritation, however, make this entity less likely. Similar to LSA, histologic examination of SCLE reveals epidermal atrophy, basal layer degeneration, and papillary dermal edema with lymphocytic inflammation. However, SCLE lacks the band of inflammation underlying pale homogenized papillary dermal collagen, the most distinguishing feature of LSA; instead, SCLE shows superficial and deep perivascular and periadnexal lymphocytes and mucin in the dermis.14

Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus may be chronic and progressive in nature or cycle through remissions and relapses.2 Treatment is not curative, and management is directed to alleviating symptoms and preventing the progression of disease. First-line management of extragenital LSA is potent topical steroids.1 Adjuvant topical calcineurin inhibitors may be used as steroid-sparing agents.2 Phototherapy is a second-line therapy and even narrowband UVB phototherapy has demonstrated efficacy in managing extragenital LSA.15,16 Our patient was started on mometasone ointment and calcipotriene cream with slight improvement after a 6-month trial. Ongoing management is focused on optimizing application of topical therapies.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

- Powell JJ, Wojnarowska F. Lichen sclerosus. Lancet. 1999;353:1777-1783.

- Fistarol SK, Itin PH. Diagnosis and treatment of lichen sclerosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2013;14:27-47.

- Meffert JJ, Davis BM, Grimwood RE. Lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995;32:393-416.

- Surkan M, Hull P. A case of lichen sclerosus et atrophicus with distinct erythematous borders. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015;19:600-603.

- Kimura A, Kambe N, Satoh T, et al. Follicular keratosis and bullous formation are typical signs of extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Dermatol. 2011;38:834-836.

- Meyrick Thomas RH, Ridley CM, McGibbon DH, et al. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and autoimmunity: a study of 350 women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;118:41-46.

- Wallace HJ. Lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. Trans St Johns Hosp Dermatol Soc. 1971;57:9-30.

- Hallel-Halevy D, Grunwald MH, Yerushalmi J, et al. Bullous lichen sclerosus et atrophicus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998;39:500-501.

- Garrido-Ríos AA, Álvarez-Garrido H, Sanz-Muñoz C, et al. Dermoscopy of extragenital lichen sclerosus. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:1468.

- Larre Borges A, Tiodorovic-Zivkovic D, Lallas A, et al. Clinical, dermoscopic and histopathologic features of genital and extragenital lichen sclerosus. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:1433-1439.

- Rudikoff D. Differential diagnosis of round or discoid lesions. Clin Dermatol. 2011;29:489-497.

- Boyd AS, Neldner KH. Lichen planus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:593-619.

- Shaffer B, Beerman H. Lichen simplex chronicus and its variants: a discussion of certain psychodynamic mechanisms and clinical and histopathologic correlations. AMA Arch Derm Syphilol. 1951;64:340-351.

- Walling HW, Sontheimer RD. Cutaneous lupus erythematosus. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10:365-381.

- Sauder MB, Linzon-Smith J, Beecker J. Extragenital bullous lichen sclerosus. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:981-984.

- Colbert RL, Chiang MP, Carlin CS, et al. Progressive extragenital lichen sclerosus successfully treated with narrowband UV-B phototherapy. Arch Dermatol. 2007;143:19-20.

A 48-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis presented with papules and plaques on the upper trunk, proximal extremities, and volar wrists. Clear fluid–filled bullae occasionally developed within the plaques and subsequently ruptured and healed. Aside from intermittent lesion tenderness and irritation with the formation and rupture of the bullae, the patient’s plaques were asymptomatic, and she specifically denied pruritus. A review of systems revealed a history of genital irritation evaluated by a gynecologist; nystatin–triamcinolone cream 0.1% applied as needed provided relief. The patient denied any recent flares or any new or changing oral mucosa findings or symptoms, preceding medications, or family history of similar lesions. Physical examination revealed well-demarcated, round, pink plaques with keratotic scale scattered across the upper trunk and central chest. The bilateral volar wrists were surfaced by well-circumscribed, thin, pink to violaceous, hyperkeratotic papules.

Genetic testing for breast and ovarian cancer: What has changed and what still needs to change?

Investigators found racial and ethnic disparities in genetic testing as well as “persistent underuse” of testing in patients with ovarian cancer.

The team also discovered that most pathogenic variant (PV) results were in 20 genes associated with breast and/or ovarian cancer, and testing other genes largely revealed variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

Allison W. Kurian, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues recounted these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Because of improvements in sequencing technology, competition among commercial purveyors, and declining cost, genetic testing has been increasingly available to clinicians for patient management and cancer prevention (JAMA. 2015 Sep 8;314[10]:997-8). Although germline testing can guide therapy for several solid tumors, there is little research about how often and how well it is used in practice.

For their study, Dr. Kurian and colleagues used a SEER Genetic Testing Linkage Demonstration Project in a population-based assessment of testing for cancer risk. The investigators analyzed 7-year trends in testing among all women diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer in Georgia or California from 2013 to 2017, reviewing testing patterns and result interpretation from 2012 to 2019.

Before analyzing the data, the investigators made the following hypotheses:

- Multigene panels (MGP) would entirely replace testing for BRCA1/2 only.

- Testing underutilization in patients with ovarian cancer would improve over time.

- More patients would be tested at lower levels of pretest risk for PVs.

- Sociodemographic differences in testing trends would not be observed.

- Detection of PVs and VUS would increase.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of VUS would diminish.

Study conduct

The investigators examined genetic tests performed from 2012 through the beginning of 2019 at major commercial laboratories and linked that information with data in the SEER registries in Georgia and California on all breast and ovarian cancer patients diagnosed between 2013 and 2017. There were few criteria for exclusion.

Genetic testing results were categorized as identifying a PV or likely PV, VUS, or benign or likely benign mutation by American College of Medical Genetics criteria. When a patient had genetic testing on more than one occasion, the most recent test was used.

If a PV was identified, the types of PVs were grouped according to the level of evidence that supported pathogenicity into the following categories:

- BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

- PVs in other genes designated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network as associated with breast or ovarian cancer (e.g., ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PALB2, MS2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, and TP53).

- PVs in other actionable genes (e.g., APC, BMPR1A, MEN1, MUTYH, NF2, RB1, RET, SDHAF2, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SMAD4, TSC1, TSC2, and VHL).

- Any other tested genes.

The investigators also tabulated instances in which genetic testing identified a VUS in any gene but no PV. If a VUS was identified originally and was reclassified more recently into the “PV/likely PV” or “benign/likely benign” categories, only the resolved categorization was recorded.

The authors evaluated clinical and sociodemographic correlates of testing trends for breast and ovarian cancer, assessing the relationship between race, age, and geographic site in receipt of any test or type of test.

Among laboratories, the investigators examined trends in the number of genes tested, associations with sociodemographic factors, categories of test results, and whether trends differed by race or ethnicity.

Findings, by hypothesis

Hypothesis #1: MGP will entirely replace testing for BRCA1/2 only.

About 25% of tested patients with breast cancer diagnosed in early 2013 received MGP, compared with more than 80% of those diagnosed in late 2017.

The trend for ovarian cancer was similar. About 40% of patients diagnosed in early 2013 received MGP, compared with more than 90% diagnosed in late 2017. These trends were similar in California and Georgia.

From 2012 to 2019, there was a consistent upward trend in gene number for patients with breast cancer (mean, 19) or ovarian cancer (mean, 21), from approximately 10 genes to 35 genes.

Hypothesis #2: Underutilization of testing in patients with ovarian cancer will improve.

Among the 187,535 patients with breast cancer and the 14,689 patients with ovarian cancer diagnosed in Georgia or California from 2013 through 2017, on average, testing rates increased 2% per year.

In all, 25.2% of breast cancer patients and 34.3% of ovarian cancer patients had genetic testing on one (87.3%) or more (12.7%) occasions.

Prior research suggested that, in 2013 and 2014, 31% of women with ovarian cancer had genetic testing (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Aug 1;4[8]:1066-72/ J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 20;37[15]:1305-15).

The investigators therefore concluded that underutilization of genetic testing in ovarian cancer did not improve substantially during the 7-year interval analyzed.

Hypothesis #3: More patients will be tested at lower levels of pretest risk.

These data were more difficult to abstract from the SEER database, but older patients were more likely to be tested in later years.

In patients older than 60 years of age (who accounted for more than 50% of both cancer cohorts), testing rates increased from 11.1% to 14.9% for breast cancer and 25.3% to 31.4% for ovarian cancer. By contrast, patients younger than 45 years of age were less than 15% of the sample and had lower testing rates over time.

There were no substantial changes in testing rates by other clinical variables. Therefore, in concert with the age-related testing trends, it is likely that women were tested for genetic mutations at increasingly lower levels of pretest risk.

Hypothesis #4: Sociodemographic differences in testing trends will not be observed.

Among patients with breast cancer, approximately 31% of those who had genetic testing were uninsured, 31% had Medicaid, and 26% had private insurance, Medicare, or other insurance.

For patients with ovarian cancer, approximately 28% were uninsured, 27% had Medicaid, and 39% had private insurance, Medicare, or other insurance.

The authors had previously found that less testing was associated with Black race, greater poverty, and less insurance coverage (J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 20;37[15]:1305-15). However, they noted no changes in testing rates by sociodemographic variables over time.

Hypothesis #5: Detection of both PVs and VUS will increase.

The proportion of tested breast cancer patients with PVs in BRCA1/2 decreased from 7.5% to 5.0% (P < .001), whereas PV yield for the two other clinically salient categories (breast or ovarian and other actionable genes) increased.

The proportion of PVs in any breast or ovarian gene increased from 1.3% to 4.6%, and the proportion in any other actionable gene increased from 0.3% to 1.3%.

For breast cancer patients, VUS-only rates increased from 8.5% in early 2013 to 22.4% in late 2017.

For ovarian cancer patients, the yield of PVs in BRCA1/2 decreased from 15.7% to 12.4% (P < .001), whereas the PV yield for breast or ovarian genes increased from 3.9% to 4.3%, and the yield for other actionable genes increased from 0.3% to 2.0%.

In ovarian cancer patients, the PV or VUS-only result rate increased from 30.8% in early 2013 to 43.0% in late 2017, entirely due to the increase in VUS-only rates. VUS were identified in 8.1% of patients diagnosed in early 2013 and increased to 28.3% in patients diagnosed in late 2017.

Hypothesis #6: Racial or ethnic disparities in rates of VUS will diminish.

Among patients with breast cancer, racial or ethnic differences in PV rates were small and did not change over time. For patients with ovarian cancer, PV rates across racial or ethnic groups diminished over time.

However, for both breast and ovarian cancer patients, there were large differences in VUS-only rates by race and ethnicity that persisted during the interval studied.

In 2017, for patients with breast cancer, VUS-only rates were substantially higher in Asian (42.4%), Black (36.6%), and Hispanic (27.7%) patients than in non-Hispanic White patients (24.5%, P < .001).

Similar trends were noted for patients with ovarian cancer. VUS-only rates were substantially higher in Asian (47.8%), Black (46.0%), and Hispanic (36.8%) patients than in non-Hispanic White patients (24.6%, P < .001).

Multivariable logistic regressions were performed separately for tested patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer, and the results showed no significant interaction between race or ethnicity and date. Therefore, there was no significant change in racial or ethnic differences in VUS-only results across the study period.

Where these findings leave clinicians in 2021

Among the patients studied, there was:

- Marked expansion in the number of genes sequenced.

- A likely modest trend toward testing patients with lower pretest risk of a PV.

- No sociodemographic differences in testing trends.

- A small increase in PV rates and a substantial increase in VUS-only rates.

- Near-complete replacement of selective testing by MGP.

For patients with breast cancer, the proportion of all PVs that were in BRCA1/2 fell substantially. Adoption of MGP testing doubled the probability of detecting a PV in other tested genes. Most of the increase was in genes with an established breast or ovarian cancer association, with fewer PVs found in other actionable genes and very few PVs in other tested genes.

Contrary to their hypothesis, the authors observed a sustained undertesting of patients with ovarian cancer. Only 34.3% performed versus nearly 100% recommended, with little change since 2014.

This finding is surprising – and tremendously disappointing – since the prevalence of BRCA1/2 PVs is higher in ovarian cancer than in other cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Nov;147[2]:375-380), and germline-targeted therapy with PARP inhibitors has been approved for use since 2014.

Furthermore, insurance carriers provide coverage for genetic testing in most patients with carcinoma of the ovary, fallopian tube, and/or peritoneum.

Action plans: Less could be more

During the period analyzed, the increase in VUS-only results dramatically outpaced the increase in PVs.

Since there is a substantially larger volume of clinical genetic testing in non-Hispanic White patients with breast or ovarian cancer, the spectrum of normal variation is less well-defined in other racial or ethnic groups.

The study showed a widening of the “racial-ethnic VUS gap,” with Black and Asian patients having nearly twofold more VUS, although they were not tested for more genes than non-Hispanic White patients.

This is problematic on several levels. Identification of a VUS is challenging for communicating results to and recommending cascade testing for family members.

There is worrisome information regarding overtreatment or counseling of VUS patients about their results. For example, the PROMPT registry showed that 10%-15% of women with PV/VUS in genes not associated with a high risk of ovarian cancer underwent oophorectomy without a clear indication for the procedure.

Although population-based testing might augment the available data on the spectrum of normal variation in racial and ethnic minorities, it would likely exacerbate the proliferation of VUS over PVs.

It is essential to accelerate ongoing approaches to VUS reclassification.

In addition, the authors suggest that it may be time to reverse the trend in increasing the number of genes tested in MGPs. Their rationale is that, in Georgia and California, most PVs among patients with breast and ovarian cancer were identified in 20 genes (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PMS2, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, and TP53).

If the Georgia and California data are representative of a more generalized pattern, a panel of 20 breast cancer– and/or ovarian cancer–associated genes may be ideal for maximizing the yield of clinically relevant PVs and minimizing VUS results for all patients.

Finally, defining the patient, clinician, and health care system factors that impede widespread genetic testing for ovarian cancer patients must be prioritized. As the authors suggest, quality improvement efforts should focus on getting a lot closer to testing rates of 100% for patients with ovarian cancer and building the database that will help sort VUS in minority patients into their proper context of pathogenicity, rather than adding more genes per test.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Ambry Genetics, Color Genomics, GeneDx/BioReference, InVitae, Genentech, Genomic Health, Roche/Genentech, Oncoquest, Tesaro, and Karyopharm Therapeutics.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Investigators found racial and ethnic disparities in genetic testing as well as “persistent underuse” of testing in patients with ovarian cancer.

The team also discovered that most pathogenic variant (PV) results were in 20 genes associated with breast and/or ovarian cancer, and testing other genes largely revealed variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

Allison W. Kurian, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues recounted these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Because of improvements in sequencing technology, competition among commercial purveyors, and declining cost, genetic testing has been increasingly available to clinicians for patient management and cancer prevention (JAMA. 2015 Sep 8;314[10]:997-8). Although germline testing can guide therapy for several solid tumors, there is little research about how often and how well it is used in practice.

For their study, Dr. Kurian and colleagues used a SEER Genetic Testing Linkage Demonstration Project in a population-based assessment of testing for cancer risk. The investigators analyzed 7-year trends in testing among all women diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer in Georgia or California from 2013 to 2017, reviewing testing patterns and result interpretation from 2012 to 2019.

Before analyzing the data, the investigators made the following hypotheses:

- Multigene panels (MGP) would entirely replace testing for BRCA1/2 only.

- Testing underutilization in patients with ovarian cancer would improve over time.

- More patients would be tested at lower levels of pretest risk for PVs.

- Sociodemographic differences in testing trends would not be observed.

- Detection of PVs and VUS would increase.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of VUS would diminish.

Study conduct

The investigators examined genetic tests performed from 2012 through the beginning of 2019 at major commercial laboratories and linked that information with data in the SEER registries in Georgia and California on all breast and ovarian cancer patients diagnosed between 2013 and 2017. There were few criteria for exclusion.

Genetic testing results were categorized as identifying a PV or likely PV, VUS, or benign or likely benign mutation by American College of Medical Genetics criteria. When a patient had genetic testing on more than one occasion, the most recent test was used.

If a PV was identified, the types of PVs were grouped according to the level of evidence that supported pathogenicity into the following categories:

- BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

- PVs in other genes designated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network as associated with breast or ovarian cancer (e.g., ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PALB2, MS2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, and TP53).

- PVs in other actionable genes (e.g., APC, BMPR1A, MEN1, MUTYH, NF2, RB1, RET, SDHAF2, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SMAD4, TSC1, TSC2, and VHL).

- Any other tested genes.

The investigators also tabulated instances in which genetic testing identified a VUS in any gene but no PV. If a VUS was identified originally and was reclassified more recently into the “PV/likely PV” or “benign/likely benign” categories, only the resolved categorization was recorded.

The authors evaluated clinical and sociodemographic correlates of testing trends for breast and ovarian cancer, assessing the relationship between race, age, and geographic site in receipt of any test or type of test.

Among laboratories, the investigators examined trends in the number of genes tested, associations with sociodemographic factors, categories of test results, and whether trends differed by race or ethnicity.

Findings, by hypothesis

Hypothesis #1: MGP will entirely replace testing for BRCA1/2 only.

About 25% of tested patients with breast cancer diagnosed in early 2013 received MGP, compared with more than 80% of those diagnosed in late 2017.

The trend for ovarian cancer was similar. About 40% of patients diagnosed in early 2013 received MGP, compared with more than 90% diagnosed in late 2017. These trends were similar in California and Georgia.

From 2012 to 2019, there was a consistent upward trend in gene number for patients with breast cancer (mean, 19) or ovarian cancer (mean, 21), from approximately 10 genes to 35 genes.

Hypothesis #2: Underutilization of testing in patients with ovarian cancer will improve.

Among the 187,535 patients with breast cancer and the 14,689 patients with ovarian cancer diagnosed in Georgia or California from 2013 through 2017, on average, testing rates increased 2% per year.

In all, 25.2% of breast cancer patients and 34.3% of ovarian cancer patients had genetic testing on one (87.3%) or more (12.7%) occasions.

Prior research suggested that, in 2013 and 2014, 31% of women with ovarian cancer had genetic testing (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Aug 1;4[8]:1066-72/ J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 20;37[15]:1305-15).

The investigators therefore concluded that underutilization of genetic testing in ovarian cancer did not improve substantially during the 7-year interval analyzed.

Hypothesis #3: More patients will be tested at lower levels of pretest risk.

These data were more difficult to abstract from the SEER database, but older patients were more likely to be tested in later years.

In patients older than 60 years of age (who accounted for more than 50% of both cancer cohorts), testing rates increased from 11.1% to 14.9% for breast cancer and 25.3% to 31.4% for ovarian cancer. By contrast, patients younger than 45 years of age were less than 15% of the sample and had lower testing rates over time.

There were no substantial changes in testing rates by other clinical variables. Therefore, in concert with the age-related testing trends, it is likely that women were tested for genetic mutations at increasingly lower levels of pretest risk.

Hypothesis #4: Sociodemographic differences in testing trends will not be observed.

Among patients with breast cancer, approximately 31% of those who had genetic testing were uninsured, 31% had Medicaid, and 26% had private insurance, Medicare, or other insurance.

For patients with ovarian cancer, approximately 28% were uninsured, 27% had Medicaid, and 39% had private insurance, Medicare, or other insurance.

The authors had previously found that less testing was associated with Black race, greater poverty, and less insurance coverage (J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 20;37[15]:1305-15). However, they noted no changes in testing rates by sociodemographic variables over time.

Hypothesis #5: Detection of both PVs and VUS will increase.

The proportion of tested breast cancer patients with PVs in BRCA1/2 decreased from 7.5% to 5.0% (P < .001), whereas PV yield for the two other clinically salient categories (breast or ovarian and other actionable genes) increased.

The proportion of PVs in any breast or ovarian gene increased from 1.3% to 4.6%, and the proportion in any other actionable gene increased from 0.3% to 1.3%.

For breast cancer patients, VUS-only rates increased from 8.5% in early 2013 to 22.4% in late 2017.

For ovarian cancer patients, the yield of PVs in BRCA1/2 decreased from 15.7% to 12.4% (P < .001), whereas the PV yield for breast or ovarian genes increased from 3.9% to 4.3%, and the yield for other actionable genes increased from 0.3% to 2.0%.

In ovarian cancer patients, the PV or VUS-only result rate increased from 30.8% in early 2013 to 43.0% in late 2017, entirely due to the increase in VUS-only rates. VUS were identified in 8.1% of patients diagnosed in early 2013 and increased to 28.3% in patients diagnosed in late 2017.

Hypothesis #6: Racial or ethnic disparities in rates of VUS will diminish.

Among patients with breast cancer, racial or ethnic differences in PV rates were small and did not change over time. For patients with ovarian cancer, PV rates across racial or ethnic groups diminished over time.

However, for both breast and ovarian cancer patients, there were large differences in VUS-only rates by race and ethnicity that persisted during the interval studied.

In 2017, for patients with breast cancer, VUS-only rates were substantially higher in Asian (42.4%), Black (36.6%), and Hispanic (27.7%) patients than in non-Hispanic White patients (24.5%, P < .001).

Similar trends were noted for patients with ovarian cancer. VUS-only rates were substantially higher in Asian (47.8%), Black (46.0%), and Hispanic (36.8%) patients than in non-Hispanic White patients (24.6%, P < .001).

Multivariable logistic regressions were performed separately for tested patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer, and the results showed no significant interaction between race or ethnicity and date. Therefore, there was no significant change in racial or ethnic differences in VUS-only results across the study period.

Where these findings leave clinicians in 2021

Among the patients studied, there was:

- Marked expansion in the number of genes sequenced.

- A likely modest trend toward testing patients with lower pretest risk of a PV.

- No sociodemographic differences in testing trends.

- A small increase in PV rates and a substantial increase in VUS-only rates.

- Near-complete replacement of selective testing by MGP.

For patients with breast cancer, the proportion of all PVs that were in BRCA1/2 fell substantially. Adoption of MGP testing doubled the probability of detecting a PV in other tested genes. Most of the increase was in genes with an established breast or ovarian cancer association, with fewer PVs found in other actionable genes and very few PVs in other tested genes.

Contrary to their hypothesis, the authors observed a sustained undertesting of patients with ovarian cancer. Only 34.3% performed versus nearly 100% recommended, with little change since 2014.

This finding is surprising – and tremendously disappointing – since the prevalence of BRCA1/2 PVs is higher in ovarian cancer than in other cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Nov;147[2]:375-380), and germline-targeted therapy with PARP inhibitors has been approved for use since 2014.

Furthermore, insurance carriers provide coverage for genetic testing in most patients with carcinoma of the ovary, fallopian tube, and/or peritoneum.

Action plans: Less could be more

During the period analyzed, the increase in VUS-only results dramatically outpaced the increase in PVs.

Since there is a substantially larger volume of clinical genetic testing in non-Hispanic White patients with breast or ovarian cancer, the spectrum of normal variation is less well-defined in other racial or ethnic groups.

The study showed a widening of the “racial-ethnic VUS gap,” with Black and Asian patients having nearly twofold more VUS, although they were not tested for more genes than non-Hispanic White patients.

This is problematic on several levels. Identification of a VUS is challenging for communicating results to and recommending cascade testing for family members.

There is worrisome information regarding overtreatment or counseling of VUS patients about their results. For example, the PROMPT registry showed that 10%-15% of women with PV/VUS in genes not associated with a high risk of ovarian cancer underwent oophorectomy without a clear indication for the procedure.

Although population-based testing might augment the available data on the spectrum of normal variation in racial and ethnic minorities, it would likely exacerbate the proliferation of VUS over PVs.

It is essential to accelerate ongoing approaches to VUS reclassification.

In addition, the authors suggest that it may be time to reverse the trend in increasing the number of genes tested in MGPs. Their rationale is that, in Georgia and California, most PVs among patients with breast and ovarian cancer were identified in 20 genes (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PMS2, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, and TP53).

If the Georgia and California data are representative of a more generalized pattern, a panel of 20 breast cancer– and/or ovarian cancer–associated genes may be ideal for maximizing the yield of clinically relevant PVs and minimizing VUS results for all patients.

Finally, defining the patient, clinician, and health care system factors that impede widespread genetic testing for ovarian cancer patients must be prioritized. As the authors suggest, quality improvement efforts should focus on getting a lot closer to testing rates of 100% for patients with ovarian cancer and building the database that will help sort VUS in minority patients into their proper context of pathogenicity, rather than adding more genes per test.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Ambry Genetics, Color Genomics, GeneDx/BioReference, InVitae, Genentech, Genomic Health, Roche/Genentech, Oncoquest, Tesaro, and Karyopharm Therapeutics.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

Investigators found racial and ethnic disparities in genetic testing as well as “persistent underuse” of testing in patients with ovarian cancer.

The team also discovered that most pathogenic variant (PV) results were in 20 genes associated with breast and/or ovarian cancer, and testing other genes largely revealed variants of uncertain significance (VUS).

Allison W. Kurian, MD, of Stanford (Calif.) University, and colleagues recounted these findings in the Journal of Clinical Oncology.

Because of improvements in sequencing technology, competition among commercial purveyors, and declining cost, genetic testing has been increasingly available to clinicians for patient management and cancer prevention (JAMA. 2015 Sep 8;314[10]:997-8). Although germline testing can guide therapy for several solid tumors, there is little research about how often and how well it is used in practice.

For their study, Dr. Kurian and colleagues used a SEER Genetic Testing Linkage Demonstration Project in a population-based assessment of testing for cancer risk. The investigators analyzed 7-year trends in testing among all women diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer in Georgia or California from 2013 to 2017, reviewing testing patterns and result interpretation from 2012 to 2019.

Before analyzing the data, the investigators made the following hypotheses:

- Multigene panels (MGP) would entirely replace testing for BRCA1/2 only.

- Testing underutilization in patients with ovarian cancer would improve over time.

- More patients would be tested at lower levels of pretest risk for PVs.

- Sociodemographic differences in testing trends would not be observed.

- Detection of PVs and VUS would increase.

- Racial and ethnic disparities in rates of VUS would diminish.

Study conduct

The investigators examined genetic tests performed from 2012 through the beginning of 2019 at major commercial laboratories and linked that information with data in the SEER registries in Georgia and California on all breast and ovarian cancer patients diagnosed between 2013 and 2017. There were few criteria for exclusion.

Genetic testing results were categorized as identifying a PV or likely PV, VUS, or benign or likely benign mutation by American College of Medical Genetics criteria. When a patient had genetic testing on more than one occasion, the most recent test was used.

If a PV was identified, the types of PVs were grouped according to the level of evidence that supported pathogenicity into the following categories:

- BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations.

- PVs in other genes designated by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network as associated with breast or ovarian cancer (e.g., ATM, BARD1, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PALB2, MS2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, and TP53).

- PVs in other actionable genes (e.g., APC, BMPR1A, MEN1, MUTYH, NF2, RB1, RET, SDHAF2, SDHB, SDHC, SDHD, SMAD4, TSC1, TSC2, and VHL).

- Any other tested genes.

The investigators also tabulated instances in which genetic testing identified a VUS in any gene but no PV. If a VUS was identified originally and was reclassified more recently into the “PV/likely PV” or “benign/likely benign” categories, only the resolved categorization was recorded.

The authors evaluated clinical and sociodemographic correlates of testing trends for breast and ovarian cancer, assessing the relationship between race, age, and geographic site in receipt of any test or type of test.

Among laboratories, the investigators examined trends in the number of genes tested, associations with sociodemographic factors, categories of test results, and whether trends differed by race or ethnicity.

Findings, by hypothesis

Hypothesis #1: MGP will entirely replace testing for BRCA1/2 only.

About 25% of tested patients with breast cancer diagnosed in early 2013 received MGP, compared with more than 80% of those diagnosed in late 2017.

The trend for ovarian cancer was similar. About 40% of patients diagnosed in early 2013 received MGP, compared with more than 90% diagnosed in late 2017. These trends were similar in California and Georgia.

From 2012 to 2019, there was a consistent upward trend in gene number for patients with breast cancer (mean, 19) or ovarian cancer (mean, 21), from approximately 10 genes to 35 genes.

Hypothesis #2: Underutilization of testing in patients with ovarian cancer will improve.

Among the 187,535 patients with breast cancer and the 14,689 patients with ovarian cancer diagnosed in Georgia or California from 2013 through 2017, on average, testing rates increased 2% per year.

In all, 25.2% of breast cancer patients and 34.3% of ovarian cancer patients had genetic testing on one (87.3%) or more (12.7%) occasions.

Prior research suggested that, in 2013 and 2014, 31% of women with ovarian cancer had genetic testing (JAMA Oncol. 2018 Aug 1;4[8]:1066-72/ J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 20;37[15]:1305-15).

The investigators therefore concluded that underutilization of genetic testing in ovarian cancer did not improve substantially during the 7-year interval analyzed.

Hypothesis #3: More patients will be tested at lower levels of pretest risk.

These data were more difficult to abstract from the SEER database, but older patients were more likely to be tested in later years.

In patients older than 60 years of age (who accounted for more than 50% of both cancer cohorts), testing rates increased from 11.1% to 14.9% for breast cancer and 25.3% to 31.4% for ovarian cancer. By contrast, patients younger than 45 years of age were less than 15% of the sample and had lower testing rates over time.

There were no substantial changes in testing rates by other clinical variables. Therefore, in concert with the age-related testing trends, it is likely that women were tested for genetic mutations at increasingly lower levels of pretest risk.

Hypothesis #4: Sociodemographic differences in testing trends will not be observed.

Among patients with breast cancer, approximately 31% of those who had genetic testing were uninsured, 31% had Medicaid, and 26% had private insurance, Medicare, or other insurance.

For patients with ovarian cancer, approximately 28% were uninsured, 27% had Medicaid, and 39% had private insurance, Medicare, or other insurance.

The authors had previously found that less testing was associated with Black race, greater poverty, and less insurance coverage (J Clin Oncol. 2019 May 20;37[15]:1305-15). However, they noted no changes in testing rates by sociodemographic variables over time.

Hypothesis #5: Detection of both PVs and VUS will increase.

The proportion of tested breast cancer patients with PVs in BRCA1/2 decreased from 7.5% to 5.0% (P < .001), whereas PV yield for the two other clinically salient categories (breast or ovarian and other actionable genes) increased.

The proportion of PVs in any breast or ovarian gene increased from 1.3% to 4.6%, and the proportion in any other actionable gene increased from 0.3% to 1.3%.

For breast cancer patients, VUS-only rates increased from 8.5% in early 2013 to 22.4% in late 2017.

For ovarian cancer patients, the yield of PVs in BRCA1/2 decreased from 15.7% to 12.4% (P < .001), whereas the PV yield for breast or ovarian genes increased from 3.9% to 4.3%, and the yield for other actionable genes increased from 0.3% to 2.0%.

In ovarian cancer patients, the PV or VUS-only result rate increased from 30.8% in early 2013 to 43.0% in late 2017, entirely due to the increase in VUS-only rates. VUS were identified in 8.1% of patients diagnosed in early 2013 and increased to 28.3% in patients diagnosed in late 2017.

Hypothesis #6: Racial or ethnic disparities in rates of VUS will diminish.

Among patients with breast cancer, racial or ethnic differences in PV rates were small and did not change over time. For patients with ovarian cancer, PV rates across racial or ethnic groups diminished over time.

However, for both breast and ovarian cancer patients, there were large differences in VUS-only rates by race and ethnicity that persisted during the interval studied.

In 2017, for patients with breast cancer, VUS-only rates were substantially higher in Asian (42.4%), Black (36.6%), and Hispanic (27.7%) patients than in non-Hispanic White patients (24.5%, P < .001).

Similar trends were noted for patients with ovarian cancer. VUS-only rates were substantially higher in Asian (47.8%), Black (46.0%), and Hispanic (36.8%) patients than in non-Hispanic White patients (24.6%, P < .001).

Multivariable logistic regressions were performed separately for tested patients with breast cancer and ovarian cancer, and the results showed no significant interaction between race or ethnicity and date. Therefore, there was no significant change in racial or ethnic differences in VUS-only results across the study period.

Where these findings leave clinicians in 2021

Among the patients studied, there was:

- Marked expansion in the number of genes sequenced.

- A likely modest trend toward testing patients with lower pretest risk of a PV.

- No sociodemographic differences in testing trends.

- A small increase in PV rates and a substantial increase in VUS-only rates.

- Near-complete replacement of selective testing by MGP.

For patients with breast cancer, the proportion of all PVs that were in BRCA1/2 fell substantially. Adoption of MGP testing doubled the probability of detecting a PV in other tested genes. Most of the increase was in genes with an established breast or ovarian cancer association, with fewer PVs found in other actionable genes and very few PVs in other tested genes.

Contrary to their hypothesis, the authors observed a sustained undertesting of patients with ovarian cancer. Only 34.3% performed versus nearly 100% recommended, with little change since 2014.

This finding is surprising – and tremendously disappointing – since the prevalence of BRCA1/2 PVs is higher in ovarian cancer than in other cancers (Gynecol Oncol. 2017 Nov;147[2]:375-380), and germline-targeted therapy with PARP inhibitors has been approved for use since 2014.

Furthermore, insurance carriers provide coverage for genetic testing in most patients with carcinoma of the ovary, fallopian tube, and/or peritoneum.

Action plans: Less could be more

During the period analyzed, the increase in VUS-only results dramatically outpaced the increase in PVs.

Since there is a substantially larger volume of clinical genetic testing in non-Hispanic White patients with breast or ovarian cancer, the spectrum of normal variation is less well-defined in other racial or ethnic groups.

The study showed a widening of the “racial-ethnic VUS gap,” with Black and Asian patients having nearly twofold more VUS, although they were not tested for more genes than non-Hispanic White patients.

This is problematic on several levels. Identification of a VUS is challenging for communicating results to and recommending cascade testing for family members.

There is worrisome information regarding overtreatment or counseling of VUS patients about their results. For example, the PROMPT registry showed that 10%-15% of women with PV/VUS in genes not associated with a high risk of ovarian cancer underwent oophorectomy without a clear indication for the procedure.

Although population-based testing might augment the available data on the spectrum of normal variation in racial and ethnic minorities, it would likely exacerbate the proliferation of VUS over PVs.

It is essential to accelerate ongoing approaches to VUS reclassification.

In addition, the authors suggest that it may be time to reverse the trend in increasing the number of genes tested in MGPs. Their rationale is that, in Georgia and California, most PVs among patients with breast and ovarian cancer were identified in 20 genes (ATM, BARD1, BRCA1, BRCA2, BRIP1, CDH1, CHEK2, EPCAM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, NBN, NF1, PMS2, PALB2, PTEN, RAD51C, RAD51D, STK11, and TP53).

If the Georgia and California data are representative of a more generalized pattern, a panel of 20 breast cancer– and/or ovarian cancer–associated genes may be ideal for maximizing the yield of clinically relevant PVs and minimizing VUS results for all patients.

Finally, defining the patient, clinician, and health care system factors that impede widespread genetic testing for ovarian cancer patients must be prioritized. As the authors suggest, quality improvement efforts should focus on getting a lot closer to testing rates of 100% for patients with ovarian cancer and building the database that will help sort VUS in minority patients into their proper context of pathogenicity, rather than adding more genes per test.

This research was supported by the National Cancer Institute, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, and the California Department of Public Health. The authors disclosed relationships with Myriad Genetics, Ambry Genetics, Color Genomics, GeneDx/BioReference, InVitae, Genentech, Genomic Health, Roche/Genentech, Oncoquest, Tesaro, and Karyopharm Therapeutics.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers, as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL ONCOLOGY

Anti-CD20s linked to higher COVID-19 severity in MS

Like other people, a biostatistician told neurologists. With the exception of anti-CD20s, registries also suggest that disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) don’t cause higher degrees of severity.

“It’s good news since it’s important for patients to stay on these treatments,” said Amber Salter, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor at Washington University, St. Louis, in a follow-up interview following her presentation at the meeting held by the Americas Committee for Treatment and Research in Multiple Sclerosis.

Dr. Salter reported on the findings of several MS/COVID-19 registries from around the world, including the COViMS Registry, which is supported by the Consortium of MS Centers, the MS Society of Canada, and the National MS Society. It tracks patients who developed COVID-19 while also having MS, neuromyelitis optica, or MOG antibody disease.

The registry began collecting data in April 2020 and is ongoing. As of Jan. 29, 2021, 2,059 patients had been tracked; 85% of cases were confirmed by laboratory tests. Nearly all patients (97%) were from the United States, with about 21% from New York state. Nearly 76% were female, the average age was 48. About 70% were non-Hispanic White, 18% were African American; 83% had relapsing remitting MS, and 17% had progressive MS.

“We found that 11.5% of MS patients were reported being hospitalized, while 4.2% were admitted to the ICU or ventilated and 3% had died,” Dr. Salter said. Not surprisingly, the death rate was highest (21%) in patients aged 75 years or older, compared with 11% of those aged 65-74 years. Those with more severe cases – those who were nonambulatory – had a death rate of 18%, compared with 0.6% of those who were fully ambulatory and 4% of those who walked with assistance.

“A lot of the risks [for COVID-19 severity] we see in the general population are risks in the MS population,” Dr. Salter said.

Dr. Salter also summarized the results of other international registries. After adjustment, a registry in Italy linked the anti-CD20 drugs ocrelizumab or rituximab (odds ratio, 2.37, P = .015) and recent use of methylprednisolone (OR, 5.2; P = .001) to more severe courses of COVID-19, compared with other DMTs. And a global data-sharing project linked anti-CD20s to more severe outcomes, compared with other DMTs (hospitalization, adjusted prevalence ratio, 1.49; ICU admission, aPR, 2.55; and ventilation, aPR, 3.05).