User login

Study confirms link between PAP apnea treatment and dementia onset

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treatment with positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy was associated with a lower odds of incident Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia in a large retrospective cohort study of Medicare patients with the sleep disorder.

The study builds on research linking OSA to poor cognitive outcomes and dementia syndromes. With use of a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries (more than 2.7 million) and their claims data, investigators identified approximately 53,000 who had an OSA diagnosis prior to 2011.

Of these Medicare beneficiaries, 78% with OSA were identified as “PAP-treated” based on having at least one durable medical equipment claim for PAP equipment. And of those treated, 74% were identified as “PAP adherent” based on having more than two PAP equipment claims separated by at least a month, said Galit Levi Dunietz, PhD, MPH, at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Dr. Dunietz and her coinvestigators used logistic regression to examine the associations between PAP treatment and PAP treatment adherence, and incident ICD-9 diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia not otherwise specified (DNOS) over the period 2011-2013.

After adjustments for potential confounders (age, sex, race, stroke, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and depression), OSA treatment was associated with a significantly lower odds of a diagnosis of AD (odds ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval 0.69-0.89) or DNOS (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55-0.85), as well as nonsignificantly lower odds of MCI diagnosis (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66-1.02).

“People who are treated for OSA have a 22% reduced odds of being diagnosed with AD and a 31% reduced odds of getting DNOS,” said Dr. Dunietz, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in an interview after the meeting. “The 18% reduced odds of mild cognitive disorder is not really significant because the upper bound is 1.02, but we consider it approaching significance.”

Adherence to treatment was significantly associated with lower odds of AD, but not with significantly lower odds of DNOS or MCI, she said. OSA was confirmed by ICD-9 diagnosis codes plus the presence of relevant polysomnography current procedural terminology code.

All told, the findings “suggest that PAP therapy for OSA may lower short-term risk for dementia in older persons,” Dr. Dunietz and her co-nvestigators said in their poster presentation. “If a causal pathway exists between OSA and dementia, treatment of OSA may offer new opportunities to improve cognitive outcomes in older adults with OSA.”

Andrew W. Varga, MD, of the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Mount Sinai Integrative Sleep Center, both in New York, said that cognitive impairment is now a recognized clinical consequence of OSA and that OSA treatment could be a target for the prevention of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease in particular.

“I absolutely bring it up with patients in their 60s and 70s. I’m honest – I say, there seems to be more and more evidence for links between apnea and Alzheimer’s in particular. I tell them we don’t know 100% whether PAP reverses any of this, but it stands to reason that it does,” said Dr. Varga, who was asked to comment on the study and related research.

An analysis published several years ago in Neurology from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort found that patients with self-reported sleep apnea had a younger age of MCI or AD onset (about 10 years) and that patients who used continuous positive airway pressure had a delayed age of onset. “Those who had a subjective diagnosis of sleep apnea and who also reported using CPAP as treatment seemed to go in the opposite direction,” said Dr. Varga, a coauthor of that study. “They had an onset of AD that looked just like people who had no sleep apnea.”

While this study was limited by sleep apnea being self-reported – and by the lack of severity data – the newly reported study may be limited by the use of ICD codes and the fact that OSA is often entered into patient’s chart before diagnosis is confirmed through a sleep study, Dr. Varga said.

“The field is mature enough that we should be thinking of doing honest and rigorous clinical trials for sleep apnea with cognitive outcomes being a main measure of interest,” he said. “The issue we’re struggling with in the field is that such a trial would not be short.”

There are several theories for the link between OSA and cognitive impairment, he said, including disruptions in sleep architecture leading to increased production of amyloid and tau and/or decreased “clearance” of extracellular amyloid, neuronal sensitivity to hypoxia, and cardiovascular comorbidities.

Dr. Dunietz’s study was supported by The American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no disclosures. Dr. Varga said he has no relevant disclosures.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treatment with positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy was associated with a lower odds of incident Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia in a large retrospective cohort study of Medicare patients with the sleep disorder.

The study builds on research linking OSA to poor cognitive outcomes and dementia syndromes. With use of a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries (more than 2.7 million) and their claims data, investigators identified approximately 53,000 who had an OSA diagnosis prior to 2011.

Of these Medicare beneficiaries, 78% with OSA were identified as “PAP-treated” based on having at least one durable medical equipment claim for PAP equipment. And of those treated, 74% were identified as “PAP adherent” based on having more than two PAP equipment claims separated by at least a month, said Galit Levi Dunietz, PhD, MPH, at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Dr. Dunietz and her coinvestigators used logistic regression to examine the associations between PAP treatment and PAP treatment adherence, and incident ICD-9 diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia not otherwise specified (DNOS) over the period 2011-2013.

After adjustments for potential confounders (age, sex, race, stroke, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and depression), OSA treatment was associated with a significantly lower odds of a diagnosis of AD (odds ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval 0.69-0.89) or DNOS (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55-0.85), as well as nonsignificantly lower odds of MCI diagnosis (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66-1.02).

“People who are treated for OSA have a 22% reduced odds of being diagnosed with AD and a 31% reduced odds of getting DNOS,” said Dr. Dunietz, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in an interview after the meeting. “The 18% reduced odds of mild cognitive disorder is not really significant because the upper bound is 1.02, but we consider it approaching significance.”

Adherence to treatment was significantly associated with lower odds of AD, but not with significantly lower odds of DNOS or MCI, she said. OSA was confirmed by ICD-9 diagnosis codes plus the presence of relevant polysomnography current procedural terminology code.

All told, the findings “suggest that PAP therapy for OSA may lower short-term risk for dementia in older persons,” Dr. Dunietz and her co-nvestigators said in their poster presentation. “If a causal pathway exists between OSA and dementia, treatment of OSA may offer new opportunities to improve cognitive outcomes in older adults with OSA.”

Andrew W. Varga, MD, of the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Mount Sinai Integrative Sleep Center, both in New York, said that cognitive impairment is now a recognized clinical consequence of OSA and that OSA treatment could be a target for the prevention of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease in particular.

“I absolutely bring it up with patients in their 60s and 70s. I’m honest – I say, there seems to be more and more evidence for links between apnea and Alzheimer’s in particular. I tell them we don’t know 100% whether PAP reverses any of this, but it stands to reason that it does,” said Dr. Varga, who was asked to comment on the study and related research.

An analysis published several years ago in Neurology from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort found that patients with self-reported sleep apnea had a younger age of MCI or AD onset (about 10 years) and that patients who used continuous positive airway pressure had a delayed age of onset. “Those who had a subjective diagnosis of sleep apnea and who also reported using CPAP as treatment seemed to go in the opposite direction,” said Dr. Varga, a coauthor of that study. “They had an onset of AD that looked just like people who had no sleep apnea.”

While this study was limited by sleep apnea being self-reported – and by the lack of severity data – the newly reported study may be limited by the use of ICD codes and the fact that OSA is often entered into patient’s chart before diagnosis is confirmed through a sleep study, Dr. Varga said.

“The field is mature enough that we should be thinking of doing honest and rigorous clinical trials for sleep apnea with cognitive outcomes being a main measure of interest,” he said. “The issue we’re struggling with in the field is that such a trial would not be short.”

There are several theories for the link between OSA and cognitive impairment, he said, including disruptions in sleep architecture leading to increased production of amyloid and tau and/or decreased “clearance” of extracellular amyloid, neuronal sensitivity to hypoxia, and cardiovascular comorbidities.

Dr. Dunietz’s study was supported by The American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no disclosures. Dr. Varga said he has no relevant disclosures.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) treatment with positive airway pressure (PAP) therapy was associated with a lower odds of incident Alzheimer’s disease and other dementia in a large retrospective cohort study of Medicare patients with the sleep disorder.

The study builds on research linking OSA to poor cognitive outcomes and dementia syndromes. With use of a 5% random sample of Medicare beneficiaries (more than 2.7 million) and their claims data, investigators identified approximately 53,000 who had an OSA diagnosis prior to 2011.

Of these Medicare beneficiaries, 78% with OSA were identified as “PAP-treated” based on having at least one durable medical equipment claim for PAP equipment. And of those treated, 74% were identified as “PAP adherent” based on having more than two PAP equipment claims separated by at least a month, said Galit Levi Dunietz, PhD, MPH, at the virtual annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

Dr. Dunietz and her coinvestigators used logistic regression to examine the associations between PAP treatment and PAP treatment adherence, and incident ICD-9 diagnoses of Alzheimer’s disease (AD), mild cognitive impairment (MCI), and dementia not otherwise specified (DNOS) over the period 2011-2013.

After adjustments for potential confounders (age, sex, race, stroke, hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and depression), OSA treatment was associated with a significantly lower odds of a diagnosis of AD (odds ratio, 0.78; 95% confidence interval 0.69-0.89) or DNOS (OR, 0.69; 95% CI, 0.55-0.85), as well as nonsignificantly lower odds of MCI diagnosis (OR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.66-1.02).

“People who are treated for OSA have a 22% reduced odds of being diagnosed with AD and a 31% reduced odds of getting DNOS,” said Dr. Dunietz, from the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor, in an interview after the meeting. “The 18% reduced odds of mild cognitive disorder is not really significant because the upper bound is 1.02, but we consider it approaching significance.”

Adherence to treatment was significantly associated with lower odds of AD, but not with significantly lower odds of DNOS or MCI, she said. OSA was confirmed by ICD-9 diagnosis codes plus the presence of relevant polysomnography current procedural terminology code.

All told, the findings “suggest that PAP therapy for OSA may lower short-term risk for dementia in older persons,” Dr. Dunietz and her co-nvestigators said in their poster presentation. “If a causal pathway exists between OSA and dementia, treatment of OSA may offer new opportunities to improve cognitive outcomes in older adults with OSA.”

Andrew W. Varga, MD, of the division of pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai and the Mount Sinai Integrative Sleep Center, both in New York, said that cognitive impairment is now a recognized clinical consequence of OSA and that OSA treatment could be a target for the prevention of cognitive impairment and Alzheimer’s disease in particular.

“I absolutely bring it up with patients in their 60s and 70s. I’m honest – I say, there seems to be more and more evidence for links between apnea and Alzheimer’s in particular. I tell them we don’t know 100% whether PAP reverses any of this, but it stands to reason that it does,” said Dr. Varga, who was asked to comment on the study and related research.

An analysis published several years ago in Neurology from the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative cohort found that patients with self-reported sleep apnea had a younger age of MCI or AD onset (about 10 years) and that patients who used continuous positive airway pressure had a delayed age of onset. “Those who had a subjective diagnosis of sleep apnea and who also reported using CPAP as treatment seemed to go in the opposite direction,” said Dr. Varga, a coauthor of that study. “They had an onset of AD that looked just like people who had no sleep apnea.”

While this study was limited by sleep apnea being self-reported – and by the lack of severity data – the newly reported study may be limited by the use of ICD codes and the fact that OSA is often entered into patient’s chart before diagnosis is confirmed through a sleep study, Dr. Varga said.

“The field is mature enough that we should be thinking of doing honest and rigorous clinical trials for sleep apnea with cognitive outcomes being a main measure of interest,” he said. “The issue we’re struggling with in the field is that such a trial would not be short.”

There are several theories for the link between OSA and cognitive impairment, he said, including disruptions in sleep architecture leading to increased production of amyloid and tau and/or decreased “clearance” of extracellular amyloid, neuronal sensitivity to hypoxia, and cardiovascular comorbidities.

Dr. Dunietz’s study was supported by The American Academy of Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no disclosures. Dr. Varga said he has no relevant disclosures.

FROM SLEEP 2020

More dairy lowers risk of falls, fractures in frail elderly

Consuming more milk, cheese, or yogurt might be a simple, low-cost way to boost bone health and prevent some falls and fractures in older people living in long-term care facilities, according to a new randomized study from Australia.

“Supplementation using dairy foods is likely to be an effective, safe, widely available, and low cost means of curtailing the public health burden of fractures,” said Sandra Iuliano, PhD, from the University of Melbourne, who presented the findings during the virtual American Society of Bone and Mineral Research 2020 annual meeting.

The researchers randomized 60 old-age institutions to provide residents with their usual menus or a diet with more milk, cheese, or yogurt for 2 years.

The residents with the altered menus increased their dairy consumption from 2 servings/day to 3.5 servings/day, which was reflected in a greater intake of calcium and protein, along with fewer falls, total fractures, and hip fractures than in the control group.

“This is the first randomized trial to show a benefit of dairy food intake on risk of fractures,” Walter Willett, MD, DrPH, professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

The results are “not surprising” because supplements of calcium plus vitamin D have reduced the risk of fractures in a similar population of older residents living in special living facilities, said Dr. Willett, coauthor of a recent review article, “Milk and Health,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It is important for everyone to have adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D,” he said. However, “it isn’t clear whether it is better to ensure this clinically by supplements, overall healthy diet, or extra dairy intake,” he added, noting that consuming the amount of dairy given in this Australian study is not environmentally sustainable.

Clifford Rosen, MD, professor of medicine, Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview that the Australian researchers studied the impact of increased dietary calcium and protein, not the impact of vitamin D via supplements.

“This is progress toward getting interventions to our most needy residents to prevent fractures – probably the most compelling data that we have had in a number of years,” he noted.

The current study shows “it’s not [the] vitamin D,” because the residents had initial low calcium levels but normal vitamin D levels. “For too long we’ve been stuck on the idea that it is [increasing] vitamin D in the elderly that causes a reduction in fractures,” said Dr. Rosen. “The data are not very supportive of it, but people continue to think that’s the most important element.”

On the other hand, the current study raises certain questions. “What we don’t know is, is it the calcium, or is it the protein, or the combination, that had an impact?”

Would upping dairy decrease falls?

Older adults living in institutions have a high risk of falls and fractures, including hip fractures, and “malnutrition is common,” said Dr. Iuliano during her presentation.

Prior studies have reported that such residents have a daily dietary calcium intake of 635 mg (half the recommended 1,300 mg), a protein intake of 0.8 g/kg body weight (less than the recommended 1 g/kg body weight), and a dairy intake of 1.5 servings (about a third of the recommended amount), she said.

The group hypothesized that upping dairy intake of elderly residents living in long-term care institutions would reduce the risk of fractures. They performed a 2-year cluster-randomized trial in 60 facilities in Melbourne and surrounding areas.

Half gave their 3,301 residents menus with a higher dairy content, and the other half gave their 3,894 residents (controls) the usual menus.

The residents in both groups had similar characteristics: they were a mean age of 87 years and 68% were women. A subgroup had blood tests and bone morphology studies at baseline and 1 year.

Researchers verified nutrient intake by analyzing the menus and doing plate waste analysis for a subgroup, and they determined the number of falls and fractures from incident and hospital x-ray reports, respectively.

One-third fewer fractures in the higher-dairy group

At the study start, residents in both groups had similar vitamin D levels (72 nmol/L) and bone morphology. They were consuming two servings of dairy food and drink a day, where a serving was 250 mL of milk (including lactose-free milk) or 200 g of yogurt or 40 g of cheese.

Their initial daily calcium intake was 650 mg, which stayed the same in the control group, but increased to >1100 mg in the intervention group.

Their initial daily protein intake was around 59 g, which remained the same in the control group, but increased to about 72 grams (1.1 g/kg body weight) in the intervention group.

At 2 years, the 1.5 servings/day increase in dairy intake in the control versus intervention group was associated with an 11% reduction in falls (62% vs. 57%), a 33% reduction in fractures (5.2% vs. 3.7%), a 46% reduction in hip fractures (2.4% vs. 1.3%), and no difference in mortality (28% in both groups).

The intervention was also associated with a slowing in bone loss and an increase in insulinlike growth factor–1.

Four dairy servings a day “is high”

Dr. Willett said that “it is reasonable for seniors to take one or two servings of dairy per day, but four servings per day, as in this study, is probably not necessary.”

Moreover, “dairy production has a major impact on greenhouse gas emissions, and even two servings per day would not be environmentally sustainable if everyone were to consume this amount,” he observed.

“Because the world is facing an existential threat from climate change, general advice to consume high amounts of dairy products would be irresponsible as we can get all essential nutrients from other sources,” he added. “That said, modest amounts of dairy foods, such as one to two servings per day could be reasonable. There is some suggestive evidence that dairy in the form of yogurt may have particular benefits.”

The study was funded by Melbourne University and various dietary councils. Dr. Iuliano reported receiving lecture fees from Abbott. Dr. Rosen and Dr. Willett reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Consuming more milk, cheese, or yogurt might be a simple, low-cost way to boost bone health and prevent some falls and fractures in older people living in long-term care facilities, according to a new randomized study from Australia.

“Supplementation using dairy foods is likely to be an effective, safe, widely available, and low cost means of curtailing the public health burden of fractures,” said Sandra Iuliano, PhD, from the University of Melbourne, who presented the findings during the virtual American Society of Bone and Mineral Research 2020 annual meeting.

The researchers randomized 60 old-age institutions to provide residents with their usual menus or a diet with more milk, cheese, or yogurt for 2 years.

The residents with the altered menus increased their dairy consumption from 2 servings/day to 3.5 servings/day, which was reflected in a greater intake of calcium and protein, along with fewer falls, total fractures, and hip fractures than in the control group.

“This is the first randomized trial to show a benefit of dairy food intake on risk of fractures,” Walter Willett, MD, DrPH, professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

The results are “not surprising” because supplements of calcium plus vitamin D have reduced the risk of fractures in a similar population of older residents living in special living facilities, said Dr. Willett, coauthor of a recent review article, “Milk and Health,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It is important for everyone to have adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D,” he said. However, “it isn’t clear whether it is better to ensure this clinically by supplements, overall healthy diet, or extra dairy intake,” he added, noting that consuming the amount of dairy given in this Australian study is not environmentally sustainable.

Clifford Rosen, MD, professor of medicine, Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview that the Australian researchers studied the impact of increased dietary calcium and protein, not the impact of vitamin D via supplements.

“This is progress toward getting interventions to our most needy residents to prevent fractures – probably the most compelling data that we have had in a number of years,” he noted.

The current study shows “it’s not [the] vitamin D,” because the residents had initial low calcium levels but normal vitamin D levels. “For too long we’ve been stuck on the idea that it is [increasing] vitamin D in the elderly that causes a reduction in fractures,” said Dr. Rosen. “The data are not very supportive of it, but people continue to think that’s the most important element.”

On the other hand, the current study raises certain questions. “What we don’t know is, is it the calcium, or is it the protein, or the combination, that had an impact?”

Would upping dairy decrease falls?

Older adults living in institutions have a high risk of falls and fractures, including hip fractures, and “malnutrition is common,” said Dr. Iuliano during her presentation.

Prior studies have reported that such residents have a daily dietary calcium intake of 635 mg (half the recommended 1,300 mg), a protein intake of 0.8 g/kg body weight (less than the recommended 1 g/kg body weight), and a dairy intake of 1.5 servings (about a third of the recommended amount), she said.

The group hypothesized that upping dairy intake of elderly residents living in long-term care institutions would reduce the risk of fractures. They performed a 2-year cluster-randomized trial in 60 facilities in Melbourne and surrounding areas.

Half gave their 3,301 residents menus with a higher dairy content, and the other half gave their 3,894 residents (controls) the usual menus.

The residents in both groups had similar characteristics: they were a mean age of 87 years and 68% were women. A subgroup had blood tests and bone morphology studies at baseline and 1 year.

Researchers verified nutrient intake by analyzing the menus and doing plate waste analysis for a subgroup, and they determined the number of falls and fractures from incident and hospital x-ray reports, respectively.

One-third fewer fractures in the higher-dairy group

At the study start, residents in both groups had similar vitamin D levels (72 nmol/L) and bone morphology. They were consuming two servings of dairy food and drink a day, where a serving was 250 mL of milk (including lactose-free milk) or 200 g of yogurt or 40 g of cheese.

Their initial daily calcium intake was 650 mg, which stayed the same in the control group, but increased to >1100 mg in the intervention group.

Their initial daily protein intake was around 59 g, which remained the same in the control group, but increased to about 72 grams (1.1 g/kg body weight) in the intervention group.

At 2 years, the 1.5 servings/day increase in dairy intake in the control versus intervention group was associated with an 11% reduction in falls (62% vs. 57%), a 33% reduction in fractures (5.2% vs. 3.7%), a 46% reduction in hip fractures (2.4% vs. 1.3%), and no difference in mortality (28% in both groups).

The intervention was also associated with a slowing in bone loss and an increase in insulinlike growth factor–1.

Four dairy servings a day “is high”

Dr. Willett said that “it is reasonable for seniors to take one or two servings of dairy per day, but four servings per day, as in this study, is probably not necessary.”

Moreover, “dairy production has a major impact on greenhouse gas emissions, and even two servings per day would not be environmentally sustainable if everyone were to consume this amount,” he observed.

“Because the world is facing an existential threat from climate change, general advice to consume high amounts of dairy products would be irresponsible as we can get all essential nutrients from other sources,” he added. “That said, modest amounts of dairy foods, such as one to two servings per day could be reasonable. There is some suggestive evidence that dairy in the form of yogurt may have particular benefits.”

The study was funded by Melbourne University and various dietary councils. Dr. Iuliano reported receiving lecture fees from Abbott. Dr. Rosen and Dr. Willett reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Consuming more milk, cheese, or yogurt might be a simple, low-cost way to boost bone health and prevent some falls and fractures in older people living in long-term care facilities, according to a new randomized study from Australia.

“Supplementation using dairy foods is likely to be an effective, safe, widely available, and low cost means of curtailing the public health burden of fractures,” said Sandra Iuliano, PhD, from the University of Melbourne, who presented the findings during the virtual American Society of Bone and Mineral Research 2020 annual meeting.

The researchers randomized 60 old-age institutions to provide residents with their usual menus or a diet with more milk, cheese, or yogurt for 2 years.

The residents with the altered menus increased their dairy consumption from 2 servings/day to 3.5 servings/day, which was reflected in a greater intake of calcium and protein, along with fewer falls, total fractures, and hip fractures than in the control group.

“This is the first randomized trial to show a benefit of dairy food intake on risk of fractures,” Walter Willett, MD, DrPH, professor of nutrition and epidemiology at the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, said in an interview.

The results are “not surprising” because supplements of calcium plus vitamin D have reduced the risk of fractures in a similar population of older residents living in special living facilities, said Dr. Willett, coauthor of a recent review article, “Milk and Health,” published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“It is important for everyone to have adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D,” he said. However, “it isn’t clear whether it is better to ensure this clinically by supplements, overall healthy diet, or extra dairy intake,” he added, noting that consuming the amount of dairy given in this Australian study is not environmentally sustainable.

Clifford Rosen, MD, professor of medicine, Tufts University, Boston, said in an interview that the Australian researchers studied the impact of increased dietary calcium and protein, not the impact of vitamin D via supplements.

“This is progress toward getting interventions to our most needy residents to prevent fractures – probably the most compelling data that we have had in a number of years,” he noted.

The current study shows “it’s not [the] vitamin D,” because the residents had initial low calcium levels but normal vitamin D levels. “For too long we’ve been stuck on the idea that it is [increasing] vitamin D in the elderly that causes a reduction in fractures,” said Dr. Rosen. “The data are not very supportive of it, but people continue to think that’s the most important element.”

On the other hand, the current study raises certain questions. “What we don’t know is, is it the calcium, or is it the protein, or the combination, that had an impact?”

Would upping dairy decrease falls?

Older adults living in institutions have a high risk of falls and fractures, including hip fractures, and “malnutrition is common,” said Dr. Iuliano during her presentation.

Prior studies have reported that such residents have a daily dietary calcium intake of 635 mg (half the recommended 1,300 mg), a protein intake of 0.8 g/kg body weight (less than the recommended 1 g/kg body weight), and a dairy intake of 1.5 servings (about a third of the recommended amount), she said.

The group hypothesized that upping dairy intake of elderly residents living in long-term care institutions would reduce the risk of fractures. They performed a 2-year cluster-randomized trial in 60 facilities in Melbourne and surrounding areas.

Half gave their 3,301 residents menus with a higher dairy content, and the other half gave their 3,894 residents (controls) the usual menus.

The residents in both groups had similar characteristics: they were a mean age of 87 years and 68% were women. A subgroup had blood tests and bone morphology studies at baseline and 1 year.

Researchers verified nutrient intake by analyzing the menus and doing plate waste analysis for a subgroup, and they determined the number of falls and fractures from incident and hospital x-ray reports, respectively.

One-third fewer fractures in the higher-dairy group

At the study start, residents in both groups had similar vitamin D levels (72 nmol/L) and bone morphology. They were consuming two servings of dairy food and drink a day, where a serving was 250 mL of milk (including lactose-free milk) or 200 g of yogurt or 40 g of cheese.

Their initial daily calcium intake was 650 mg, which stayed the same in the control group, but increased to >1100 mg in the intervention group.

Their initial daily protein intake was around 59 g, which remained the same in the control group, but increased to about 72 grams (1.1 g/kg body weight) in the intervention group.

At 2 years, the 1.5 servings/day increase in dairy intake in the control versus intervention group was associated with an 11% reduction in falls (62% vs. 57%), a 33% reduction in fractures (5.2% vs. 3.7%), a 46% reduction in hip fractures (2.4% vs. 1.3%), and no difference in mortality (28% in both groups).

The intervention was also associated with a slowing in bone loss and an increase in insulinlike growth factor–1.

Four dairy servings a day “is high”

Dr. Willett said that “it is reasonable for seniors to take one or two servings of dairy per day, but four servings per day, as in this study, is probably not necessary.”

Moreover, “dairy production has a major impact on greenhouse gas emissions, and even two servings per day would not be environmentally sustainable if everyone were to consume this amount,” he observed.

“Because the world is facing an existential threat from climate change, general advice to consume high amounts of dairy products would be irresponsible as we can get all essential nutrients from other sources,” he added. “That said, modest amounts of dairy foods, such as one to two servings per day could be reasonable. There is some suggestive evidence that dairy in the form of yogurt may have particular benefits.”

The study was funded by Melbourne University and various dietary councils. Dr. Iuliano reported receiving lecture fees from Abbott. Dr. Rosen and Dr. Willett reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM ASBMR 2020

VA Looks to Increase Real-World Impact of Clinical Research

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is embracing clinical trials with a focus on oncology, and patients will benefit from new priorities and programs, VA officials reported at the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) virtual meeting. “The whole model is one that is far more proactive,” said Carolyn Clancy, MD, Under Secretary for Health for Discovery, Education, and Affiliate Networks.

According to Clancy, the department’s top research priority is to increase veteran access to high-quality clinical trials. “Priority number 2 is increasing the real-world impact of VA research,” she said. “Our commitment to veterans and the taxpayers is to reverse and shorten the [research-to-implementation] timeline. And the third priority is to put VA data to work for veterans, not just through people who work in VA and Veterans Health Administration, but through other researchers who can have access to them.”

To meet these goals, VA is engaging in multiple research programs and collaborations. Rachel B. Ramoni, DMD, ScD, the VA chief research and development officer, highlighted a number of the projects in a separate AVAHO meeting presentation, including:

- The National Cancer Institute and VA Interagency Group to Accelerate Trials Enrollment (NAVIGATE), an interagency collaboration between the VA and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). This program established a network of sites to help enrolled veterans take part in NCI-supported clinical trials. “It really got up and running in 2018, and I’m proud to say that over 250 veterans have been enrolled, and enrollment exceeds that at non-NAVIGATE sites,” Ramoni reported. “Clearly, the additional support that these sites are getting is really helping to achieve the outcome of getting more veterans access to these trials.” However, she said, some areas of the nation aren’t yet covered by the program.

- The Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP), established through a partnership with the Prostate Cancer Foundation. The foundation provided a $50 million investment. “This program ensures that veterans, no matter where they are, get best-in-class prostate cancer care,” Ramoni explained. “The initial focus was ensuring that men get sequencing if they have metastatic prostate cancer, and that they get access to clinical trials. The really distinguishing factor about POPCaP is that it has built a vibrant community of clinicians, researchers and program offices. The whole is much greater than the sum of its parts.” More POPCaP hubs are in development, she said.

- PATCH (Prostate Cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice), a program funded by the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. “The whole purpose of PATCH is to create this network of sites to systematically go through different clinical trials that are biomarker-driven,” Ramoni said. “One of the great things about PATCH is that it’s leveraging the genetics databases to help proactively identify men who might qualify for these trials and to find them wherever they might be across the system so they have access to these trials.” She also praised the program’s commitment to collaboration and mentorship. “If you’re new to putting together clinical trials concepts or to submitting merit proposals to VA for funding, PATCH is a great place to get into a community that’s supportive and wants to help you succeed.”

- The VA Phenomics Library. This library, based at the Boston VA Medical Center, focuses on improving the analysis of “messy” electronic health record data, Ramoni noted. “There are automated algorithms that go through and help you clean up that data to make sense of it,” she said. “The problem is that it’s really been an every-person-for-himself-or-herself system. Each researcher who needed these phenotypes was creating his or her own.” The Phenomics Library will promote sharing “so there’s not going to be as much wasted time duplicating effort,” she said. “By the end of fiscal year 2021, we will have over 1,000 curated phenotypes in there. We hope that will be a great resource for the oncology community as well as many other communities.”

- Access to Clinical Trials (ACT) for Veterans. “This program, which began a couple of years ago, has really succeeded,” Ramoni said. “We were focusing on decreasing the time it takes to start up multi-site industry trials. When we got started with ACT, it was taking over 200 days to get started. And now, just a couple years later, we are well under 100 days, which is within industry standards.” Also, she said, the VA established a Partnered Research Program office, “which serves to interact with our industry partners and really guide them through the VA system, which can be complex if you’re approaching it for the first time.”

In a separate presentation, Krissa Caroff, MS, CPC, program manager of the Partnered Research Program, said it had quickened the process of implementing clinical trials by tackling roadblocks such as the need for multiple master agreements to be signed. Central coordination has been key, she said, “and we are working closely to ensure that we when have a multisite trial, all the VA sites are utilizing the same single IRB [institutional review board]. We’ve also identified the critical information that we need to collect from industry in order for us to evaluate a trial.”

What’s next? “We really are going to be focusing on oncology trials,” Ramoni insisted. “This is a high priority for us.” She added: “Please share your feedback and experiences with us. And also please communicate amongst your colleagues within your organization to explain how we’re standardizing things within VA.”

The speakers reported no relevant disclosures.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is embracing clinical trials with a focus on oncology, and patients will benefit from new priorities and programs, VA officials reported at the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) virtual meeting. “The whole model is one that is far more proactive,” said Carolyn Clancy, MD, Under Secretary for Health for Discovery, Education, and Affiliate Networks.

According to Clancy, the department’s top research priority is to increase veteran access to high-quality clinical trials. “Priority number 2 is increasing the real-world impact of VA research,” she said. “Our commitment to veterans and the taxpayers is to reverse and shorten the [research-to-implementation] timeline. And the third priority is to put VA data to work for veterans, not just through people who work in VA and Veterans Health Administration, but through other researchers who can have access to them.”

To meet these goals, VA is engaging in multiple research programs and collaborations. Rachel B. Ramoni, DMD, ScD, the VA chief research and development officer, highlighted a number of the projects in a separate AVAHO meeting presentation, including:

- The National Cancer Institute and VA Interagency Group to Accelerate Trials Enrollment (NAVIGATE), an interagency collaboration between the VA and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). This program established a network of sites to help enrolled veterans take part in NCI-supported clinical trials. “It really got up and running in 2018, and I’m proud to say that over 250 veterans have been enrolled, and enrollment exceeds that at non-NAVIGATE sites,” Ramoni reported. “Clearly, the additional support that these sites are getting is really helping to achieve the outcome of getting more veterans access to these trials.” However, she said, some areas of the nation aren’t yet covered by the program.

- The Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP), established through a partnership with the Prostate Cancer Foundation. The foundation provided a $50 million investment. “This program ensures that veterans, no matter where they are, get best-in-class prostate cancer care,” Ramoni explained. “The initial focus was ensuring that men get sequencing if they have metastatic prostate cancer, and that they get access to clinical trials. The really distinguishing factor about POPCaP is that it has built a vibrant community of clinicians, researchers and program offices. The whole is much greater than the sum of its parts.” More POPCaP hubs are in development, she said.

- PATCH (Prostate Cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice), a program funded by the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. “The whole purpose of PATCH is to create this network of sites to systematically go through different clinical trials that are biomarker-driven,” Ramoni said. “One of the great things about PATCH is that it’s leveraging the genetics databases to help proactively identify men who might qualify for these trials and to find them wherever they might be across the system so they have access to these trials.” She also praised the program’s commitment to collaboration and mentorship. “If you’re new to putting together clinical trials concepts or to submitting merit proposals to VA for funding, PATCH is a great place to get into a community that’s supportive and wants to help you succeed.”

- The VA Phenomics Library. This library, based at the Boston VA Medical Center, focuses on improving the analysis of “messy” electronic health record data, Ramoni noted. “There are automated algorithms that go through and help you clean up that data to make sense of it,” she said. “The problem is that it’s really been an every-person-for-himself-or-herself system. Each researcher who needed these phenotypes was creating his or her own.” The Phenomics Library will promote sharing “so there’s not going to be as much wasted time duplicating effort,” she said. “By the end of fiscal year 2021, we will have over 1,000 curated phenotypes in there. We hope that will be a great resource for the oncology community as well as many other communities.”

- Access to Clinical Trials (ACT) for Veterans. “This program, which began a couple of years ago, has really succeeded,” Ramoni said. “We were focusing on decreasing the time it takes to start up multi-site industry trials. When we got started with ACT, it was taking over 200 days to get started. And now, just a couple years later, we are well under 100 days, which is within industry standards.” Also, she said, the VA established a Partnered Research Program office, “which serves to interact with our industry partners and really guide them through the VA system, which can be complex if you’re approaching it for the first time.”

In a separate presentation, Krissa Caroff, MS, CPC, program manager of the Partnered Research Program, said it had quickened the process of implementing clinical trials by tackling roadblocks such as the need for multiple master agreements to be signed. Central coordination has been key, she said, “and we are working closely to ensure that we when have a multisite trial, all the VA sites are utilizing the same single IRB [institutional review board]. We’ve also identified the critical information that we need to collect from industry in order for us to evaluate a trial.”

What’s next? “We really are going to be focusing on oncology trials,” Ramoni insisted. “This is a high priority for us.” She added: “Please share your feedback and experiences with us. And also please communicate amongst your colleagues within your organization to explain how we’re standardizing things within VA.”

The speakers reported no relevant disclosures.

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) is embracing clinical trials with a focus on oncology, and patients will benefit from new priorities and programs, VA officials reported at the Association of VA Hematology/Oncology (AVAHO) virtual meeting. “The whole model is one that is far more proactive,” said Carolyn Clancy, MD, Under Secretary for Health for Discovery, Education, and Affiliate Networks.

According to Clancy, the department’s top research priority is to increase veteran access to high-quality clinical trials. “Priority number 2 is increasing the real-world impact of VA research,” she said. “Our commitment to veterans and the taxpayers is to reverse and shorten the [research-to-implementation] timeline. And the third priority is to put VA data to work for veterans, not just through people who work in VA and Veterans Health Administration, but through other researchers who can have access to them.”

To meet these goals, VA is engaging in multiple research programs and collaborations. Rachel B. Ramoni, DMD, ScD, the VA chief research and development officer, highlighted a number of the projects in a separate AVAHO meeting presentation, including:

- The National Cancer Institute and VA Interagency Group to Accelerate Trials Enrollment (NAVIGATE), an interagency collaboration between the VA and the National Cancer Institute (NCI). This program established a network of sites to help enrolled veterans take part in NCI-supported clinical trials. “It really got up and running in 2018, and I’m proud to say that over 250 veterans have been enrolled, and enrollment exceeds that at non-NAVIGATE sites,” Ramoni reported. “Clearly, the additional support that these sites are getting is really helping to achieve the outcome of getting more veterans access to these trials.” However, she said, some areas of the nation aren’t yet covered by the program.

- The Precision Oncology Program for Cancer of the Prostate (POPCaP), established through a partnership with the Prostate Cancer Foundation. The foundation provided a $50 million investment. “This program ensures that veterans, no matter where they are, get best-in-class prostate cancer care,” Ramoni explained. “The initial focus was ensuring that men get sequencing if they have metastatic prostate cancer, and that they get access to clinical trials. The really distinguishing factor about POPCaP is that it has built a vibrant community of clinicians, researchers and program offices. The whole is much greater than the sum of its parts.” More POPCaP hubs are in development, she said.

- PATCH (Prostate Cancer Analysis for Therapy Choice), a program funded by the VA and the Prostate Cancer Foundation. “The whole purpose of PATCH is to create this network of sites to systematically go through different clinical trials that are biomarker-driven,” Ramoni said. “One of the great things about PATCH is that it’s leveraging the genetics databases to help proactively identify men who might qualify for these trials and to find them wherever they might be across the system so they have access to these trials.” She also praised the program’s commitment to collaboration and mentorship. “If you’re new to putting together clinical trials concepts or to submitting merit proposals to VA for funding, PATCH is a great place to get into a community that’s supportive and wants to help you succeed.”

- The VA Phenomics Library. This library, based at the Boston VA Medical Center, focuses on improving the analysis of “messy” electronic health record data, Ramoni noted. “There are automated algorithms that go through and help you clean up that data to make sense of it,” she said. “The problem is that it’s really been an every-person-for-himself-or-herself system. Each researcher who needed these phenotypes was creating his or her own.” The Phenomics Library will promote sharing “so there’s not going to be as much wasted time duplicating effort,” she said. “By the end of fiscal year 2021, we will have over 1,000 curated phenotypes in there. We hope that will be a great resource for the oncology community as well as many other communities.”

- Access to Clinical Trials (ACT) for Veterans. “This program, which began a couple of years ago, has really succeeded,” Ramoni said. “We were focusing on decreasing the time it takes to start up multi-site industry trials. When we got started with ACT, it was taking over 200 days to get started. And now, just a couple years later, we are well under 100 days, which is within industry standards.” Also, she said, the VA established a Partnered Research Program office, “which serves to interact with our industry partners and really guide them through the VA system, which can be complex if you’re approaching it for the first time.”

In a separate presentation, Krissa Caroff, MS, CPC, program manager of the Partnered Research Program, said it had quickened the process of implementing clinical trials by tackling roadblocks such as the need for multiple master agreements to be signed. Central coordination has been key, she said, “and we are working closely to ensure that we when have a multisite trial, all the VA sites are utilizing the same single IRB [institutional review board]. We’ve also identified the critical information that we need to collect from industry in order for us to evaluate a trial.”

What’s next? “We really are going to be focusing on oncology trials,” Ramoni insisted. “This is a high priority for us.” She added: “Please share your feedback and experiences with us. And also please communicate amongst your colleagues within your organization to explain how we’re standardizing things within VA.”

The speakers reported no relevant disclosures.

Researchers examine learning curve for gender-affirming vaginoplasty

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

research suggests. For one surgeon, certain adverse events, including the need for revision surgery, were less likely after 50 cases.

“As surgical programs evolve, the important question becomes: At what case threshold are cases performed safely, efficiently, and with favorable outcomes?” said Cecile A. Ferrando, MD, MPH, program director of the female pelvic medicine and reconstructive surgery fellowship at Cleveland Clinic and director of the transgender surgery and medicine program in the Cleveland Clinic’s Center for LGBT Care.

The answer could guide training for future surgeons, Dr. Ferrando said at the virtual annual scientific meeting of the Society of Gynecologic Surgeons. Future studies should include patient-centered outcomes and data from multiple centers, other doctors said.

Transgender women who opt to surgically transition may undergo vaginoplasty. Although many reports describe surgical techniques, “there is a paucity of evidence-based data as well as few reports on outcomes,” Dr. Ferrando noted.

To describe perioperative adverse events related to vaginoplasty performed for gender affirmation and determine a minimum number of cases needed to reduce their likelihood, Dr. Ferrando performed a retrospective study of 76 patients. The patients underwent surgery between December 2015 and March 2019 and had 6-month postoperative outcomes available. Dr. Ferrando performed the procedures.

Dr. Ferrando evaluated outcomes after increments of 10 cases. After 50 cases, the median surgical time decreased to approximately 180 minutes, which an informal survey of surgeons suggested was efficient, and the rates of adverse events were similar to those in other studies. Dr. Ferrando compared outcomes from the first 50 cases with outcomes from the 26 cases that followed.

Overall, the patients had a mean age of 41 years. The first 50 patients were older on average (44 years vs. 35 years). About 83% underwent full-depth vaginoplasty. The incidence of intraoperative and immediate postoperative events was low and did not differ between the two groups. Rates of delayed postoperative events – those occurring 30 or more days after surgery – did significantly differ between the two groups, however.

After 50 cases, there was a lower incidence of urinary stream abnormalities (7.7% vs. 16.3%), introital stenosis (3.9% vs. 12%), and revision surgery (that is, elective, cosmetic, or functional revision within 6 months; 19.2% vs. 44%), compared with the first 50 cases.

The study did not include patient-centered outcomes and the results may have limited generalizability, Dr. Ferrando noted. “The incidence of serious adverse events related to vaginoplasty is low while minor events are common,” she said. “A 50-case minimum may be an adequate case number target for postgraduate trainees learning how to do this surgery.”

“I learned that the incidence of serious complications, like injuries during the surgery, or serious events immediately after surgery was quite low, which was reassuring,” Dr. Ferrando said in a later interview. “The cosmetic result and detail that is involved with the surgery – something that is very important to patients – that skill set takes time and experience to refine.”

Subsequent studies should include patient-centered outcomes, which may help surgeons understand potential “sources of consternation for patients,” such as persistent corporal tissue, poor aesthetics, vaginal stenosis, urinary meatus location, and clitoral hooding, Joseph J. Pariser, MD, commented in an interview. Dr. Pariser, a urologist who specializes in gender care at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, in 2019 reviewed safety outcomes from published case series.

“In my own practice, precise placement of the urethra, familiarity with landmarks during canal dissection, and rapidity of working through steps of the surgery have all dramatically improved as our experience at University of Minnesota performing primary vaginoplasty has grown,” Dr. Pariser said.

Optimal case thresholds may vary depending on a surgeon’s background, Rachel M. Whynott, MD, a reproductive endocrinology and infertility fellow at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, said in an interview. At the University of Kansas in Kansas City, a multidisciplinary team that includes a gynecologist, a reconstructive urologist, and a plastic surgeon performs the procedure.

Dr. Whynott and colleagues recently published a retrospective study that evaluated surgical aptitude over time in a male-to-female penoscrotal vaginoplasty program . Their analysis of 43 cases identified a learning curve that was reflected in overall time in the operating room and time to neoclitoral sensation.

Investigators are “trying to add to the growing body of literature about this procedure and how we can best go about improving outcomes for our patients and improving this surgery,” Dr. Whynott said. A study that includes data from multiple centers would be useful, she added.

Dr. Ferrando disclosed authorship royalties from UpToDate. Dr. Pariser and Dr. Whynott had no relevant financial disclosures.

SOURCE: Ferrando C. SGS 2020, Abstract 09.

FROM SGS 2020

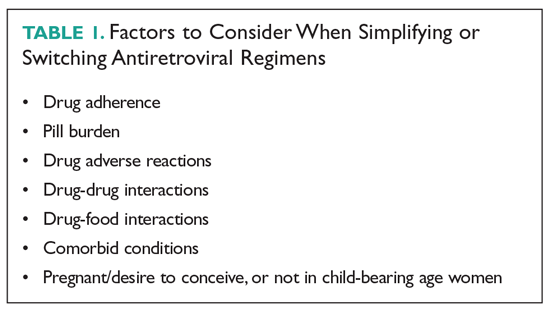

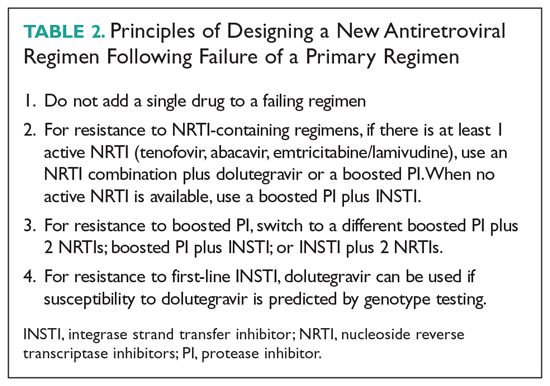

Simplifying or Switching Antiretroviral Therapy in Treatment-Experienced Adults Living With HIV

A 57-year-old man living with HIV has been followed at a local infectious disease clinic for more than 15 years. He acquired HIV disease through heterosexual contact. He lives alone and works at a convenience store; he has not been sexually active for the past 5 years. He smokes 10 cigarettes a day, but does not drink alcohol or use illicit drugs. He had been on coformulated emtricitabine/tenofovir disoproxil fumarate (TDF) and coformulated lopinavir/ritonavir, which he had taken conscientiously, since May 2008, without noticing any adverse reactions from this regimen. His HIV viral load had been undetectable, and his CD4 count had hovered between 600 and 700 cells/µL. Although he was on atorvastatin for dyslipidemia, his fasting lipid profile, performed in 2018, revealed a total cholesterol level of 200 mg/dL;triglyceride, 247 mg/dL; high-density lipoprotein (HDL), 43 mg/dL; and low-density lipoprotein (LDL), 132 mg/dL. In April 2019, his HIV regimen was switched to bictegravir/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (TAF). Blood tests performed in December 2019 revealed undetectable HIV viral load; an increased CD4 count to 849 cell/µL; total cholesterol, 140 mg/dL; triglyceride, 115 mg/dL; HDL, 60 mg/dL; and LDL, 90 mg/dL.

SIMPLIFYING ART

Virologically Suppressed Patients Without Drug-Resistant Virus

Treatment adherence is of paramount importance to ensure treatment success. Patients with a viral load that is undetectable or nearly undetectable without drug resistance could be taking ART regimens consisting of more than 1 pill and/or that require more than once-daily dosing. Decreasing pill burden or dosing frequency can help to improve adherence to treatment. In addition, older-generation ART agents are usually more toxic and less potent than newer-generation agents, so another important objective of switching older drugs to newer drugs is to decrease adverse reactions and improve virologic suppression. Selection of an ART regimen should be guided by the results of resistance testing (genotyping and phenotyping tests) and previous treatment history. After switching a patient’s ART regimen, plasma HIV viral load and CD4 count should be closely monitored.2 The following 3-drug, single-tablet, once-daily ART regimens can be used in patients who are virologically stable (ordered chronologically by FDA approval dates).

Efavirenz/Emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla)

Coformulated efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF was the first single-tablet, once-daily, fixed-dose combination approved by the FDA (July 2006). Approval was based on a 48- week clinical trial involving 244 adults with HIV infection that showed that 80% of participants achieved a marked reduction in HIV viral load and a significant increase in CD4 cell count.3 Of the 3 components, efavirenz has unique central nervous system (CNS) adverse effects that could reduce adherence. Patients who were started on this fixed-dose combination commonly reported dizziness, headache, nightmare, insomnia, and impaired concentration.4 However, the CNS side effects resolved within the first 4 weeks of therapy, and less than 5% of patients quit taking the drug. Primate studies showed efavirenz is teratogenic, but studies in pregnant women did not find efavirenz to be more teratogenic than other ART agents.5

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TDF (Complera)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TDF was approved based on data from two 48-week, phase 3, double-blind, randomized controlled trials (ECHO and THRIVE) that evaluated the safety and efficacy of rilpivirine compared to efavirenz among treatment-naive adults with HIV infection.7,8 Rilpivirine is well tolerated and causes fewer CNS symptoms compared to efavirenz. The main caveat for rilpivirine is drug-drug interactions. It should not be coadministered with CYP inducers, such as rifampin, phenytoin, or St. John’s wort, as coadministration can cause subtherapeutic blood levels of rilpivirine. Because increased levels of rilpivirine can prolong QTc on electrocardiogram (ECG), an ECG should be obtained before starting an ART regimen that contains rilpivirine, especially in the presence of CYP 3A4 inhibitors.9

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild)

This coformulation was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled trials, Study 102 and Study 103, in treatment-naive patients with HIV (n = 1408). In Study 102, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF (Atripla).10 In Study 103, participants were randomized to receive either elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF or atazanavir + ritonavir + emtricitabine/TDF. In both studies, the primary endpoint was virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL) at 48 weeks, and elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF was noninferior compared to the other regimens.11

Abacavir/Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Triumeq)

Approval of abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine (Triumeq) in August 2014 was based on SINGLE, a noninferiority trial involving 833 treatment-naive adults that compared dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine (the separate components of Triumeq) to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF. At 96 weeks, more patients in the dolutegravir and abacavir/lamivudine arm achieved an undetectable HIV viral load (80% versus 72%).13

Elvitegravir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Genvoya)

Approval of coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was supported by data from two 48-week phase 3, double-blind studies (Studies 104 and 111) involving 1733 treatment-naive patients that compared the regimen to elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TDF (Stribild). Both studies demonstrated that elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was statistically noninferior, and it was favored in regard to certain renal and bone laboratory parameters.15 Studies comparing TAF and TDF have demonstrated that TAF is less likely to cause loss of bone mineral density and nephrotoxicity compared to TDF.16,17

Emtricitabine/Rilpivirine/TAF (Odefsey)

Coformulated emtricitabine/rilpivirine/TAF was approved based, in part, on positive bioequivalence studies demonstrating that it achieved similar drug levels of emtricitabine and TAF as coformulated elvitegravir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF and similar drug levels of rilpivirine as individually dosed rilpivirine.18 The safety, efficacy, and tolerability of this coformulation is supported by clinical studies of rilpivirine-based therapy and emtricitabine/TAF-based therapy in a range of patients with HIV.18

Bictegravir/Emtricitabine/TAF (Biktarvy)

The coformulation bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF was approved based on 4 phase 3 studies: Studies 1489 and 1490 in treatment-naive adults, and Studies 1844 and 1878 in virologically suppressed adults. In Study 1489, 629 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or coformulated abacavir/dolutegravir/lamivudine. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. In Study 1490, 645 treatment-naive adults were randomized 1:1 to receive coformulated bictegravir/emtricitabine/TAF or dolutegravir + emtricitabine/TAF. At week 48, similar percentages of patients in each arm achieved the primary endpoint of virologic success (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL).19,20

Darunavir/Cobicistat/Emtricitabine/TAF (Symtuza)

Approval of coformulated darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/TAF was based on data from two 48-week, noninferiority, phase 3 studies that assessed the safety and efficacy of the coformulation versus a control regimen (darunavir/cobicistat plus emtricitabine/TDF) in adults with no prior ART history (AMBER) and in virologically suppressed adults (EMERALD). In the randomized, double-blind, multicenter controlled AMBER trial, at week 48, 91.4% of patients in the study group and 88.4% in the control group achieved viral suppression (HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL), and virologic failure rates were low in both groups (HIV-1 RNA ≥ 50 copies/mL; 4.4% versus 3.3%, respectively).21

Doravirine/Lamivudine/TDF (Delstrigo)

Coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF was approved based on data from 2 randomized, double-blind, controlled phase 3 trials, DRIVE-AHEAD and DRIVE-FORWARD. The former trial compared coformulated doravirine/lamivudine/TDF with efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF in 728 treatment-naive patients. At 48 weeks, 84.3% in the doravirine/lamivudine/TDF arm and 80.8% in the efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF arm met the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL. Thus, doravirine/lamivudine/TDF showed sustained viral suppression and noninferiority compared to efavirenz/emtricitabine/TDF.23 The DRIVE-FORWARD trial investigated doravirine compared with ritonavir-boosted darunavir, each in combination with 2 NRTIs (TDF with emtricitabine or abacavir with lamivudine). At week 48, 84% of patients in the doravirine arm and 80% in the ritonavir-boosted darunavir arm achieved the primary endpoint of HIV-1 RNA < 50 copies/mL.24

Two-Drug, Single-Tablet, Once-Daily Regimens

Experts have long recommended that optimal treatment of HIV must consist of 3 active drugs, with trials both in the United States and Europe demonstrating decreased morbidity and mortality with 3-drug therapy.25,26 However, newer, more potent 2-drug therapy is giving more choices to people living with HIV. The single-tablet, 2-drug regimens currently available are dolutegravir/rilpivirine and dolutegravir/lamivudine. There are theoretical benefits of 2-drug therapy, such as minimizing long-term toxicities, avoidance of some drug-drug interactions, and preservation of drugs for future treatment options. At this time, a 2-drug simplification regimen can be a viable option for selected virologically stable populations.

Dolutegravir/Rilpivirine (Juluca)

Dolutegravir/rilpivirine has been shown to be noninferior to standard therapy at 48-weeks, although it is associated with a higher discontinuation rate because of side effects.27 This option can be particularly useful in patients who have contraindications to NRTIs or renal dysfunction, but it has been studied only in patients without resistance who are already virologically suppressed. Ongoing studies are looking at 2-versus 3-drug therapies for HIV treatment-experienced patients. Most of these use PIs as a backbone because of their potency and high barrier to resistance. The advent of second-generation integrase inhibitors offers additional options.

Dolutegravir/Lamivudine (Dovato)

The GEMINI-1 and GEMINI-2 trials demonstrated that dolutegravir/lamivudine was noninferior to dolutegravir/TDF/emtricitabine.28 Based on these 2 studies, new guidelines have added dolutegravir/lamivudine as a recommended first-line therapy. For now, the recommendation is to use dolutegravir/lamivudine in individuals where NRTIs are contraindicated, and it should not be used in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Additionally, 3 studies have demonstrated the safety and efficacy of switching to dolutegravir/lamivudine.29-31 In the TANGO trial, neither virologic failures nor resistant virus were identified at 48 weeks following the switch.32 Although there are benefits of simplification with this regimen, including lower toxicity, lower costs, and saving other NRTIs in case of resistance, there should be no rush to switch patients to a 2-drug regimen. This is a viable strategy in patients without baseline resistance who have preserved T-cells and do not have hepatitis B.

SWITCHING ART AGENTS IN SELECTED CLINICAL SCENARIOS

Virologic Failure