User login

Genomics have changed how researchers view trauma’s immunologic impact

SAN DIEGO – Severely injured patients often experience a massive inflammatory and immunomodulatory response that can lead to multiple organ failure, nosocomial infections, long ICU stays, and poor outcomes. But not all of them do. Some patients recover relatively rapidly, achieve earlier release, and have a faster immunologic recovery trajectory.

The longstanding theory, according to Ronald Maier, MD, a professor of surgery at the University of Washington, is that a trauma-related stimulus leads to an aggressive inflammatory response that can lead to multiple organ failure and death. In patients who recover from this early challenge, the theory goes, a counterregulatory response may overexuberantly down-regulate the inflammatory storm, which leaves the patient vulnerable to infections and poor wound healing. Then a later infection, sepsis, endotoxemia, or some other stimulus may ramp up the inflammatory system again, which leads to a crisis that can trigger mortality well after the initial trauma. Patients who recover from this challenge then return to homeostasis.

It’s a neat theory, but it’s wrong, said Dr. Maier in a talk at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. It has been undercut by genomic technology and high-throughput methods that have provided a new approach to investigating the underlying biology, as well as the ability to test circulating white blood cells to measure a patient’s immune response to traumatic injury.

“If you look at the underlying biology by looking at the genomic response, you can see that it’s not a sequential process. There is simultaneous up-regulation and down-regulation,” said Dr. Maier.

A study of 35 trauma patients using a gene chip found a measurable change in expression of over 17,000 genes; 5,136 genes had at least a twofold change in expression. “Eighty percent of the human genome changes measurably when you are hit by a cement truck,” said Dr. Maier.

To researchers’ surprise, more genes were found to be down-regulated in the immediate aftermath of the injury, and most of those down-regulated genes are involved in adaptive immunity. Up-regulated pathways were included in the innate and proinflammatory response. “The simultaneous down-regulation of the adaptive arm explains why the patients in the ICU with severe injuries are very susceptible to nosocomial infections, poor wound healing, and multiple complications,” said Dr. Maier.

Genomic studies also show down-regulation of genes associated with phagocytosis even out to 45 days. “Sometimes I wonder why every patient doesn’t evolve a nosocomial infection as a consequence of this impact on the immune system. In fact, I think it’s a great testimony to the countermeasures we’ve taken as far as sterility, hand washing – we’ve been able to prevent this dysfunction from being expressed as a nosocomial infection,” said Dr. Maier.

The genomic analysis can also be used to discriminate patients who regain homeostasis relatively quickly after severe trauma. There seems to be an inflection point between patients who resolve by 5 days and those who go on to experience prolonged ICU stays.

Perhaps surprisingly, the researchers found little difference between the two groups in terms of specific genes that were up- or down-regulated. Instead, the “uncomplicated” group saw their altered gene expression patterns return more quickly to baseline levels, whereas “complicated” patients lingered in the dysregulated state. “We’ve been chasing biomarkers for 35 years, and this explains why it’s very difficult. Those who do well return toward normal quickly. Those who have complications stay abnormal,” said Dr. Maier.

Instead, researchers identified a panel of 63 gene probes that can track the overall progress of the “genomic storm,” as he referred to the changes that occur in the wake of trauma. “This panel of 63 genes is the best predictor of the patient’s response to injury – better than injury severity score, better than multiple organ failure scores,” he said.

Dr. Maier is confident that such panels can alter patient management, even outside of trauma. “It may allow us to show which patients are going to have risk of early recurrence because of alterations in their adaptive immunity versus those who aren’t. We’re also going to predict those who are going to have infectious complications. Hopefully we’ll soon have a handle on which patients we need to be most aggressive with, and we can use monitoring to measure our therapeutic impact,” said Dr. Maier.

email address

SOURCE: Add the first author et al., journal citation/abstract number, and hyperlink it here.

SAN DIEGO – Severely injured patients often experience a massive inflammatory and immunomodulatory response that can lead to multiple organ failure, nosocomial infections, long ICU stays, and poor outcomes. But not all of them do. Some patients recover relatively rapidly, achieve earlier release, and have a faster immunologic recovery trajectory.

The longstanding theory, according to Ronald Maier, MD, a professor of surgery at the University of Washington, is that a trauma-related stimulus leads to an aggressive inflammatory response that can lead to multiple organ failure and death. In patients who recover from this early challenge, the theory goes, a counterregulatory response may overexuberantly down-regulate the inflammatory storm, which leaves the patient vulnerable to infections and poor wound healing. Then a later infection, sepsis, endotoxemia, or some other stimulus may ramp up the inflammatory system again, which leads to a crisis that can trigger mortality well after the initial trauma. Patients who recover from this challenge then return to homeostasis.

It’s a neat theory, but it’s wrong, said Dr. Maier in a talk at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. It has been undercut by genomic technology and high-throughput methods that have provided a new approach to investigating the underlying biology, as well as the ability to test circulating white blood cells to measure a patient’s immune response to traumatic injury.

“If you look at the underlying biology by looking at the genomic response, you can see that it’s not a sequential process. There is simultaneous up-regulation and down-regulation,” said Dr. Maier.

A study of 35 trauma patients using a gene chip found a measurable change in expression of over 17,000 genes; 5,136 genes had at least a twofold change in expression. “Eighty percent of the human genome changes measurably when you are hit by a cement truck,” said Dr. Maier.

To researchers’ surprise, more genes were found to be down-regulated in the immediate aftermath of the injury, and most of those down-regulated genes are involved in adaptive immunity. Up-regulated pathways were included in the innate and proinflammatory response. “The simultaneous down-regulation of the adaptive arm explains why the patients in the ICU with severe injuries are very susceptible to nosocomial infections, poor wound healing, and multiple complications,” said Dr. Maier.

Genomic studies also show down-regulation of genes associated with phagocytosis even out to 45 days. “Sometimes I wonder why every patient doesn’t evolve a nosocomial infection as a consequence of this impact on the immune system. In fact, I think it’s a great testimony to the countermeasures we’ve taken as far as sterility, hand washing – we’ve been able to prevent this dysfunction from being expressed as a nosocomial infection,” said Dr. Maier.

The genomic analysis can also be used to discriminate patients who regain homeostasis relatively quickly after severe trauma. There seems to be an inflection point between patients who resolve by 5 days and those who go on to experience prolonged ICU stays.

Perhaps surprisingly, the researchers found little difference between the two groups in terms of specific genes that were up- or down-regulated. Instead, the “uncomplicated” group saw their altered gene expression patterns return more quickly to baseline levels, whereas “complicated” patients lingered in the dysregulated state. “We’ve been chasing biomarkers for 35 years, and this explains why it’s very difficult. Those who do well return toward normal quickly. Those who have complications stay abnormal,” said Dr. Maier.

Instead, researchers identified a panel of 63 gene probes that can track the overall progress of the “genomic storm,” as he referred to the changes that occur in the wake of trauma. “This panel of 63 genes is the best predictor of the patient’s response to injury – better than injury severity score, better than multiple organ failure scores,” he said.

Dr. Maier is confident that such panels can alter patient management, even outside of trauma. “It may allow us to show which patients are going to have risk of early recurrence because of alterations in their adaptive immunity versus those who aren’t. We’re also going to predict those who are going to have infectious complications. Hopefully we’ll soon have a handle on which patients we need to be most aggressive with, and we can use monitoring to measure our therapeutic impact,” said Dr. Maier.

email address

SOURCE: Add the first author et al., journal citation/abstract number, and hyperlink it here.

SAN DIEGO – Severely injured patients often experience a massive inflammatory and immunomodulatory response that can lead to multiple organ failure, nosocomial infections, long ICU stays, and poor outcomes. But not all of them do. Some patients recover relatively rapidly, achieve earlier release, and have a faster immunologic recovery trajectory.

The longstanding theory, according to Ronald Maier, MD, a professor of surgery at the University of Washington, is that a trauma-related stimulus leads to an aggressive inflammatory response that can lead to multiple organ failure and death. In patients who recover from this early challenge, the theory goes, a counterregulatory response may overexuberantly down-regulate the inflammatory storm, which leaves the patient vulnerable to infections and poor wound healing. Then a later infection, sepsis, endotoxemia, or some other stimulus may ramp up the inflammatory system again, which leads to a crisis that can trigger mortality well after the initial trauma. Patients who recover from this challenge then return to homeostasis.

It’s a neat theory, but it’s wrong, said Dr. Maier in a talk at the Critical Care Congress sponsored by the Society of Critical Care Medicine. It has been undercut by genomic technology and high-throughput methods that have provided a new approach to investigating the underlying biology, as well as the ability to test circulating white blood cells to measure a patient’s immune response to traumatic injury.

“If you look at the underlying biology by looking at the genomic response, you can see that it’s not a sequential process. There is simultaneous up-regulation and down-regulation,” said Dr. Maier.

A study of 35 trauma patients using a gene chip found a measurable change in expression of over 17,000 genes; 5,136 genes had at least a twofold change in expression. “Eighty percent of the human genome changes measurably when you are hit by a cement truck,” said Dr. Maier.

To researchers’ surprise, more genes were found to be down-regulated in the immediate aftermath of the injury, and most of those down-regulated genes are involved in adaptive immunity. Up-regulated pathways were included in the innate and proinflammatory response. “The simultaneous down-regulation of the adaptive arm explains why the patients in the ICU with severe injuries are very susceptible to nosocomial infections, poor wound healing, and multiple complications,” said Dr. Maier.

Genomic studies also show down-regulation of genes associated with phagocytosis even out to 45 days. “Sometimes I wonder why every patient doesn’t evolve a nosocomial infection as a consequence of this impact on the immune system. In fact, I think it’s a great testimony to the countermeasures we’ve taken as far as sterility, hand washing – we’ve been able to prevent this dysfunction from being expressed as a nosocomial infection,” said Dr. Maier.

The genomic analysis can also be used to discriminate patients who regain homeostasis relatively quickly after severe trauma. There seems to be an inflection point between patients who resolve by 5 days and those who go on to experience prolonged ICU stays.

Perhaps surprisingly, the researchers found little difference between the two groups in terms of specific genes that were up- or down-regulated. Instead, the “uncomplicated” group saw their altered gene expression patterns return more quickly to baseline levels, whereas “complicated” patients lingered in the dysregulated state. “We’ve been chasing biomarkers for 35 years, and this explains why it’s very difficult. Those who do well return toward normal quickly. Those who have complications stay abnormal,” said Dr. Maier.

Instead, researchers identified a panel of 63 gene probes that can track the overall progress of the “genomic storm,” as he referred to the changes that occur in the wake of trauma. “This panel of 63 genes is the best predictor of the patient’s response to injury – better than injury severity score, better than multiple organ failure scores,” he said.

Dr. Maier is confident that such panels can alter patient management, even outside of trauma. “It may allow us to show which patients are going to have risk of early recurrence because of alterations in their adaptive immunity versus those who aren’t. We’re also going to predict those who are going to have infectious complications. Hopefully we’ll soon have a handle on which patients we need to be most aggressive with, and we can use monitoring to measure our therapeutic impact,” said Dr. Maier.

email address

SOURCE: Add the first author et al., journal citation/abstract number, and hyperlink it here.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM CCC48

31-GEP test predicts likelihood of metastasis for cutaneous melanoma

WASHINGTON – The for accurately predicting recurrence-free survival and distant metastasis-free survival and melanoma-specific survival, according to results presented by Bradley N. Greenhaw, MD, at a late-breaking research session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Greenhaw, a dermatologist affiliated with the North Mississippi Medical Center-Tupelo, and his colleagues pooled together 1,268 patients from the following studies that analyzed results from melanoma patients who had their disease classified with the 31-gene expression profile (31-GEP) test.

- A single-center study, conducted by Dr. Greenhaw and his associates (Greenhaw BN et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001588.

- A multicenter prospective study (J Hematol Oncol. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0520-1.

- A retrospective archival study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.028.

The 31-GEP test stratifies an individual’s likelihood of developing metastasis within 5 years as low and high risk. In the three studies, the test was used to identify tumors with low-risk (class 1A, class 1B), higher-risk (class 2A), and highest-risk (class 2B) melanoma based on tumor gene expression. In these individual studies, class 2B melanoma independently predicted recurrence-free survival (RFS), distant metastasis–free, and melanoma-specific survival.

Dr. Greenhaw and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 1,268 patients with stage I through stage III melanoma from those three studies, using fixed and random effects weighting to account for study differences and heterogeneity, respectively. For class 2B tumors, they found a 2.96 increased risk for recurrent metastases and a 2.88 increased risk for distant metastases. The researchers also found no heterogeneity across the studies.

Melanoma-specific survival was not included in the meta-analysis because one paper did not contain any mortality events in class 1A melanoma patients.

“The meta-analysis demonstrated that the GEP test was able to accurately identify those melanoma patients who were at higher risk of metastasis, and we saw a consistent effect across multiple studies,” Dr. Greenhaw said.

Since publication of the 2019 JAAD paper, there were an additional 211 patients who met inclusion criteria and were included in an additional meta-analysis to determine whether inclusion of these patients affected the results. Dr. Greenhaw and colleagues found a 91.4% recurrence-free survival rate and a 94.1% distant metastasis–free survival rate for class 1A melanomas, compared with 45.7% and 55.5% , respectively, for class 2B tumors.

“You can see a big divergence,” Dr. Greenhaw said at the meeting. “Just by using this one test, it’s able to separate out melanomas that otherwise may be grouped in together under current AJCC [American Joint Committee on Cancer] staging,” he added. “The class 2B designation really did confirm a higher risk for recurrence in distant metastasis.”

The researchers used the SORT method to rate the quality of the data across all three studies. Level 1 evidence under the SORT method represents a systematic review or meta-analysis of good-quality studies and/or a prospective study with good follow-up, while an A-level recommendation represents good, quality evidence. Based on the meta-analysis results, the 31-GEP test meets level 1A evidence under the SORT method, Dr. Greenhaw said.

As a prognostic tool, 31-GEP has the potential to change how dermatologists manage their patients with regard to follow-up and adjuvant therapy. “It is being used not just as this novel test that gives us more information, it’s being used clinically,” said Dr. Greenhaw, who noted he regularly uses the 31-GEP test in his practice.

This is the first time that a meta-analysis has been performed for this test, he noted.

Dr. Greenhaw reports a pending relationship with Castle Biosciences.

SOURCE: Greenhaw BN et al. AAD 19. Session F055, Abstract 11370.

WASHINGTON – The for accurately predicting recurrence-free survival and distant metastasis-free survival and melanoma-specific survival, according to results presented by Bradley N. Greenhaw, MD, at a late-breaking research session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Greenhaw, a dermatologist affiliated with the North Mississippi Medical Center-Tupelo, and his colleagues pooled together 1,268 patients from the following studies that analyzed results from melanoma patients who had their disease classified with the 31-gene expression profile (31-GEP) test.

- A single-center study, conducted by Dr. Greenhaw and his associates (Greenhaw BN et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001588.

- A multicenter prospective study (J Hematol Oncol. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0520-1.

- A retrospective archival study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.028.

The 31-GEP test stratifies an individual’s likelihood of developing metastasis within 5 years as low and high risk. In the three studies, the test was used to identify tumors with low-risk (class 1A, class 1B), higher-risk (class 2A), and highest-risk (class 2B) melanoma based on tumor gene expression. In these individual studies, class 2B melanoma independently predicted recurrence-free survival (RFS), distant metastasis–free, and melanoma-specific survival.

Dr. Greenhaw and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 1,268 patients with stage I through stage III melanoma from those three studies, using fixed and random effects weighting to account for study differences and heterogeneity, respectively. For class 2B tumors, they found a 2.96 increased risk for recurrent metastases and a 2.88 increased risk for distant metastases. The researchers also found no heterogeneity across the studies.

Melanoma-specific survival was not included in the meta-analysis because one paper did not contain any mortality events in class 1A melanoma patients.

“The meta-analysis demonstrated that the GEP test was able to accurately identify those melanoma patients who were at higher risk of metastasis, and we saw a consistent effect across multiple studies,” Dr. Greenhaw said.

Since publication of the 2019 JAAD paper, there were an additional 211 patients who met inclusion criteria and were included in an additional meta-analysis to determine whether inclusion of these patients affected the results. Dr. Greenhaw and colleagues found a 91.4% recurrence-free survival rate and a 94.1% distant metastasis–free survival rate for class 1A melanomas, compared with 45.7% and 55.5% , respectively, for class 2B tumors.

“You can see a big divergence,” Dr. Greenhaw said at the meeting. “Just by using this one test, it’s able to separate out melanomas that otherwise may be grouped in together under current AJCC [American Joint Committee on Cancer] staging,” he added. “The class 2B designation really did confirm a higher risk for recurrence in distant metastasis.”

The researchers used the SORT method to rate the quality of the data across all three studies. Level 1 evidence under the SORT method represents a systematic review or meta-analysis of good-quality studies and/or a prospective study with good follow-up, while an A-level recommendation represents good, quality evidence. Based on the meta-analysis results, the 31-GEP test meets level 1A evidence under the SORT method, Dr. Greenhaw said.

As a prognostic tool, 31-GEP has the potential to change how dermatologists manage their patients with regard to follow-up and adjuvant therapy. “It is being used not just as this novel test that gives us more information, it’s being used clinically,” said Dr. Greenhaw, who noted he regularly uses the 31-GEP test in his practice.

This is the first time that a meta-analysis has been performed for this test, he noted.

Dr. Greenhaw reports a pending relationship with Castle Biosciences.

SOURCE: Greenhaw BN et al. AAD 19. Session F055, Abstract 11370.

WASHINGTON – The for accurately predicting recurrence-free survival and distant metastasis-free survival and melanoma-specific survival, according to results presented by Bradley N. Greenhaw, MD, at a late-breaking research session at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

Dr. Greenhaw, a dermatologist affiliated with the North Mississippi Medical Center-Tupelo, and his colleagues pooled together 1,268 patients from the following studies that analyzed results from melanoma patients who had their disease classified with the 31-gene expression profile (31-GEP) test.

- A single-center study, conducted by Dr. Greenhaw and his associates (Greenhaw BN et al. Dermatol Surg. 2018 Dec. doi: 10.1097/DSS.0000000000001588.

- A multicenter prospective study (J Hematol Oncol. 2017 Aug. doi: 10.1186/s13045-017-0520-1.

- A retrospective archival study (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019 Jan. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.07.028.

The 31-GEP test stratifies an individual’s likelihood of developing metastasis within 5 years as low and high risk. In the three studies, the test was used to identify tumors with low-risk (class 1A, class 1B), higher-risk (class 2A), and highest-risk (class 2B) melanoma based on tumor gene expression. In these individual studies, class 2B melanoma independently predicted recurrence-free survival (RFS), distant metastasis–free, and melanoma-specific survival.

Dr. Greenhaw and colleagues performed a meta-analysis of 1,268 patients with stage I through stage III melanoma from those three studies, using fixed and random effects weighting to account for study differences and heterogeneity, respectively. For class 2B tumors, they found a 2.96 increased risk for recurrent metastases and a 2.88 increased risk for distant metastases. The researchers also found no heterogeneity across the studies.

Melanoma-specific survival was not included in the meta-analysis because one paper did not contain any mortality events in class 1A melanoma patients.

“The meta-analysis demonstrated that the GEP test was able to accurately identify those melanoma patients who were at higher risk of metastasis, and we saw a consistent effect across multiple studies,” Dr. Greenhaw said.

Since publication of the 2019 JAAD paper, there were an additional 211 patients who met inclusion criteria and were included in an additional meta-analysis to determine whether inclusion of these patients affected the results. Dr. Greenhaw and colleagues found a 91.4% recurrence-free survival rate and a 94.1% distant metastasis–free survival rate for class 1A melanomas, compared with 45.7% and 55.5% , respectively, for class 2B tumors.

“You can see a big divergence,” Dr. Greenhaw said at the meeting. “Just by using this one test, it’s able to separate out melanomas that otherwise may be grouped in together under current AJCC [American Joint Committee on Cancer] staging,” he added. “The class 2B designation really did confirm a higher risk for recurrence in distant metastasis.”

The researchers used the SORT method to rate the quality of the data across all three studies. Level 1 evidence under the SORT method represents a systematic review or meta-analysis of good-quality studies and/or a prospective study with good follow-up, while an A-level recommendation represents good, quality evidence. Based on the meta-analysis results, the 31-GEP test meets level 1A evidence under the SORT method, Dr. Greenhaw said.

As a prognostic tool, 31-GEP has the potential to change how dermatologists manage their patients with regard to follow-up and adjuvant therapy. “It is being used not just as this novel test that gives us more information, it’s being used clinically,” said Dr. Greenhaw, who noted he regularly uses the 31-GEP test in his practice.

This is the first time that a meta-analysis has been performed for this test, he noted.

Dr. Greenhaw reports a pending relationship with Castle Biosciences.

SOURCE: Greenhaw BN et al. AAD 19. Session F055, Abstract 11370.

REPORTING FROM AAD 19

Belimumab data out to 13 years show continued safety, efficacy

New data from the longest continuous belimumab treatment in a clinical trial of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) indicate similar or lower adverse events each year and maintenance of efficacy for up to 13 years in those who initially respond to and stay on treatment.

First author Daniel J. Wallace, MD, and his colleagues reported in Arthritis & Rheumatology on 298 patients who continued from a phase 2 trial of 476 patients and its extension phase to a continuation study with belimumab (Benlysta) plus standard of care. These patients entered the continuation study having gone from placebo to 10 mg/kg belimumab or continued on 1, 4, or 10 mg/kg belimumab or escalated treatment up to 10 mg/kg. They needed to have an improvement in Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score, compared with baseline, and had no severe flare in the last 30 days of the extension study.

At year 5, 70% of patients were still in the study, and this declined to 44% at year 10 and 32% (96 patients) at the end of the study. There were stable or declining rates of the most common adverse events from year 1 to year 11 or later, and serious infections and infestations occurred at a stable rate, from 3.7 per 100 patient-years in year 1 to 6.7 per 100 patients-years through year 11, despite a reduction in immunoglobulin G levels during the study. A total of 15% of patients overall withdrew because of adverse events.

The overall SLE Responder Index response rate rose as the number of participants declined, going from 33% at 1 year and 16 weeks to 76% at 12 years and 32 weeks.

In addition to consistently low flare rates starting at year 5, “those patients remaining had reduced requirements for corticosteroids, and the percentage achieving low disease activity increased. Furthermore, patients continued to have serological improvements. ” Dr. Wallace and his coauthors wrote.

“Patients who remained in the study were likely to be those who responded better or tolerated belimumab better than patients who withdrew; hence, the findings may not be representative of all patients with SLE,” they said.

GlaxoSmithKline and Human Genome Sciences funded the study. Most of the investigators received grants, research support, or consulting fees; held shares in; or were employees of GlaxoSmithKline.

New data from the longest continuous belimumab treatment in a clinical trial of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) indicate similar or lower adverse events each year and maintenance of efficacy for up to 13 years in those who initially respond to and stay on treatment.

First author Daniel J. Wallace, MD, and his colleagues reported in Arthritis & Rheumatology on 298 patients who continued from a phase 2 trial of 476 patients and its extension phase to a continuation study with belimumab (Benlysta) plus standard of care. These patients entered the continuation study having gone from placebo to 10 mg/kg belimumab or continued on 1, 4, or 10 mg/kg belimumab or escalated treatment up to 10 mg/kg. They needed to have an improvement in Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score, compared with baseline, and had no severe flare in the last 30 days of the extension study.

At year 5, 70% of patients were still in the study, and this declined to 44% at year 10 and 32% (96 patients) at the end of the study. There were stable or declining rates of the most common adverse events from year 1 to year 11 or later, and serious infections and infestations occurred at a stable rate, from 3.7 per 100 patient-years in year 1 to 6.7 per 100 patients-years through year 11, despite a reduction in immunoglobulin G levels during the study. A total of 15% of patients overall withdrew because of adverse events.

The overall SLE Responder Index response rate rose as the number of participants declined, going from 33% at 1 year and 16 weeks to 76% at 12 years and 32 weeks.

In addition to consistently low flare rates starting at year 5, “those patients remaining had reduced requirements for corticosteroids, and the percentage achieving low disease activity increased. Furthermore, patients continued to have serological improvements. ” Dr. Wallace and his coauthors wrote.

“Patients who remained in the study were likely to be those who responded better or tolerated belimumab better than patients who withdrew; hence, the findings may not be representative of all patients with SLE,” they said.

GlaxoSmithKline and Human Genome Sciences funded the study. Most of the investigators received grants, research support, or consulting fees; held shares in; or were employees of GlaxoSmithKline.

New data from the longest continuous belimumab treatment in a clinical trial of patients with systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) indicate similar or lower adverse events each year and maintenance of efficacy for up to 13 years in those who initially respond to and stay on treatment.

First author Daniel J. Wallace, MD, and his colleagues reported in Arthritis & Rheumatology on 298 patients who continued from a phase 2 trial of 476 patients and its extension phase to a continuation study with belimumab (Benlysta) plus standard of care. These patients entered the continuation study having gone from placebo to 10 mg/kg belimumab or continued on 1, 4, or 10 mg/kg belimumab or escalated treatment up to 10 mg/kg. They needed to have an improvement in Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) score, compared with baseline, and had no severe flare in the last 30 days of the extension study.

At year 5, 70% of patients were still in the study, and this declined to 44% at year 10 and 32% (96 patients) at the end of the study. There were stable or declining rates of the most common adverse events from year 1 to year 11 or later, and serious infections and infestations occurred at a stable rate, from 3.7 per 100 patient-years in year 1 to 6.7 per 100 patients-years through year 11, despite a reduction in immunoglobulin G levels during the study. A total of 15% of patients overall withdrew because of adverse events.

The overall SLE Responder Index response rate rose as the number of participants declined, going from 33% at 1 year and 16 weeks to 76% at 12 years and 32 weeks.

In addition to consistently low flare rates starting at year 5, “those patients remaining had reduced requirements for corticosteroids, and the percentage achieving low disease activity increased. Furthermore, patients continued to have serological improvements. ” Dr. Wallace and his coauthors wrote.

“Patients who remained in the study were likely to be those who responded better or tolerated belimumab better than patients who withdrew; hence, the findings may not be representative of all patients with SLE,” they said.

GlaxoSmithKline and Human Genome Sciences funded the study. Most of the investigators received grants, research support, or consulting fees; held shares in; or were employees of GlaxoSmithKline.

FROM ARTHRITIS & RHEUMATOLOGY

Viewing childhood autism as a whole body disorder

Intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, immune problems affect subsets of patients.

LAS VEGAS – When parents of children with autism ask their primary physicians about complementary and integrative medical treatments, they often get stonewalled, according to Robert L. Hendren, DO.

“They find [clinicians] usually say, ‘Don’t try that stuff. It doesn’t work,’” Dr. Hendren said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

“Parents then go to two different sets of providers,” he said. One provider “tells them about complementary and integrative medicine, but is likely not a traditional physician who’s treating their autism. It’s somebody who knows about these biomedical interventions but when parents tell them that they’re using traditional interventions ... that person also says, ‘Don’t use that. That’s doesn’t work.’ Then they go see their traditional provider who might be thinking about traditional medications. But they’ve learned that they don’t want to tell them, ‘I’m considering using omega 3s or zinc.’ Regrettably, most times physicians don’t say, ‘Let’s examine that. Let’s look at the literature and see if that’s the right decision for you.’ By shutting a family down saying, ‘I don’t want to hear about that,’ it often leads the family to think: ‘How do I make a decision about this? How do I know what to do?’ ”

Dr. Hendren said clinicians are beginning to embrace the notion that autism is not just a brain disorder, but rather a whole body disorder. For example, he noted that significant subsets of people with autism have intestinal inflammation, digestive enzyme abnormalities, metabolic impairments, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and immunity problems that range from immune deficiency to hypersensitivity to autoimmunity. “,” said Dr. Hendren, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “I hope that by thinking about making the body healthier, we can help kids have the very best outcomes.”

Several biomedical treatments have adequate evidence to use for many patients, he said, including melatonin, probiotics, omega 3s, and possibly vitamin D3, methyl B12, oxytocin, restrictive diets, digestive enzymes, and choline. “There are strong anecdotal reports of gluten-free diet benefits,” said Dr. Hendren, who also directs the UCSF Program for Research on Neurodevelopmental and Translational Outcomes. “Some parents I greatly respect tell me it’s the single most important thing they’ve done in their child’s health, that their GI symptoms have improved, and their overall health has improved.”

In a multisite trial called aViation, researchers are evaluating the effects of an investigational vasopressin antagonist in autistic patients aged 5-17 years. The drug works by blocking a brain receptor of the vasopressin receptor that is associated with control of stress, anxiety, affection, and aggression. “The first trial in adults showed potential benefit,” Dr. Hendren said.

No robust studies exist to suggest that medical marijuana makes a difference for patients with autism, he said, but he has several patients whose parents give their affected child medical marijuana or cannabidiol. “I have a number of families who say it’s really made a big difference for their children and for how they’re doing,” he said.

In Marin County, Calif., the Oak Hill School serves a heterogeneous population of children, adolescents, and young adults, all of whom have autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or other neurologically based disorders of relating and communicating. Students receive special education instruction and customized on-site clinical programs that might include speech/language pathology, occupational therapy, and group and individual psychotherapy. Some of the students have received recent functional behavior analyses from Dr. Hendren and his colleagues, with school staff implementing positive behavior intervention programs.

The researchers also are using metabolomics as a biomarker of outcome. “We’re using metabolomics from the urine, where we can look at these processes in different clusters and see whether our interventions make a difference or not,” said Dr. Hendren, who is a past president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “We did one trial with sulforaphane, which is a concentrated broccoli sprout extract that helps with oxidative stress. It was initially developed to treat oxidative stress in cancer,” he said. Upcoming trials in this cohort include the use of folinic acid and CM-AT, a pancreatic digestive enzyme intended to increase levels of chymotrypsin.

“I think of autism as being a disorder where you have this person and there’s a veil of autism that comes over the top of them,” he said. “That veil is not the kid, although the kid becomes more and more expressed through that. If we can do something to lift that veil, we can do more and more to pull that child out.”

Dr. Hendren disclosed that he has received grants from Curemark, Roche, Shire, and Sunovion. He is a member of the advisory boards for Curemark, BioMarin, Janssen, and Axial Biotherapeutics.

Intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, immune problems affect subsets of patients.

Intestinal inflammation, oxidative stress, immune problems affect subsets of patients.

LAS VEGAS – When parents of children with autism ask their primary physicians about complementary and integrative medical treatments, they often get stonewalled, according to Robert L. Hendren, DO.

“They find [clinicians] usually say, ‘Don’t try that stuff. It doesn’t work,’” Dr. Hendren said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

“Parents then go to two different sets of providers,” he said. One provider “tells them about complementary and integrative medicine, but is likely not a traditional physician who’s treating their autism. It’s somebody who knows about these biomedical interventions but when parents tell them that they’re using traditional interventions ... that person also says, ‘Don’t use that. That’s doesn’t work.’ Then they go see their traditional provider who might be thinking about traditional medications. But they’ve learned that they don’t want to tell them, ‘I’m considering using omega 3s or zinc.’ Regrettably, most times physicians don’t say, ‘Let’s examine that. Let’s look at the literature and see if that’s the right decision for you.’ By shutting a family down saying, ‘I don’t want to hear about that,’ it often leads the family to think: ‘How do I make a decision about this? How do I know what to do?’ ”

Dr. Hendren said clinicians are beginning to embrace the notion that autism is not just a brain disorder, but rather a whole body disorder. For example, he noted that significant subsets of people with autism have intestinal inflammation, digestive enzyme abnormalities, metabolic impairments, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and immunity problems that range from immune deficiency to hypersensitivity to autoimmunity. “,” said Dr. Hendren, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “I hope that by thinking about making the body healthier, we can help kids have the very best outcomes.”

Several biomedical treatments have adequate evidence to use for many patients, he said, including melatonin, probiotics, omega 3s, and possibly vitamin D3, methyl B12, oxytocin, restrictive diets, digestive enzymes, and choline. “There are strong anecdotal reports of gluten-free diet benefits,” said Dr. Hendren, who also directs the UCSF Program for Research on Neurodevelopmental and Translational Outcomes. “Some parents I greatly respect tell me it’s the single most important thing they’ve done in their child’s health, that their GI symptoms have improved, and their overall health has improved.”

In a multisite trial called aViation, researchers are evaluating the effects of an investigational vasopressin antagonist in autistic patients aged 5-17 years. The drug works by blocking a brain receptor of the vasopressin receptor that is associated with control of stress, anxiety, affection, and aggression. “The first trial in adults showed potential benefit,” Dr. Hendren said.

No robust studies exist to suggest that medical marijuana makes a difference for patients with autism, he said, but he has several patients whose parents give their affected child medical marijuana or cannabidiol. “I have a number of families who say it’s really made a big difference for their children and for how they’re doing,” he said.

In Marin County, Calif., the Oak Hill School serves a heterogeneous population of children, adolescents, and young adults, all of whom have autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or other neurologically based disorders of relating and communicating. Students receive special education instruction and customized on-site clinical programs that might include speech/language pathology, occupational therapy, and group and individual psychotherapy. Some of the students have received recent functional behavior analyses from Dr. Hendren and his colleagues, with school staff implementing positive behavior intervention programs.

The researchers also are using metabolomics as a biomarker of outcome. “We’re using metabolomics from the urine, where we can look at these processes in different clusters and see whether our interventions make a difference or not,” said Dr. Hendren, who is a past president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “We did one trial with sulforaphane, which is a concentrated broccoli sprout extract that helps with oxidative stress. It was initially developed to treat oxidative stress in cancer,” he said. Upcoming trials in this cohort include the use of folinic acid and CM-AT, a pancreatic digestive enzyme intended to increase levels of chymotrypsin.

“I think of autism as being a disorder where you have this person and there’s a veil of autism that comes over the top of them,” he said. “That veil is not the kid, although the kid becomes more and more expressed through that. If we can do something to lift that veil, we can do more and more to pull that child out.”

Dr. Hendren disclosed that he has received grants from Curemark, Roche, Shire, and Sunovion. He is a member of the advisory boards for Curemark, BioMarin, Janssen, and Axial Biotherapeutics.

LAS VEGAS – When parents of children with autism ask their primary physicians about complementary and integrative medical treatments, they often get stonewalled, according to Robert L. Hendren, DO.

“They find [clinicians] usually say, ‘Don’t try that stuff. It doesn’t work,’” Dr. Hendren said at an annual psychopharmacology update held by the Nevada Psychiatric Association.

“Parents then go to two different sets of providers,” he said. One provider “tells them about complementary and integrative medicine, but is likely not a traditional physician who’s treating their autism. It’s somebody who knows about these biomedical interventions but when parents tell them that they’re using traditional interventions ... that person also says, ‘Don’t use that. That’s doesn’t work.’ Then they go see their traditional provider who might be thinking about traditional medications. But they’ve learned that they don’t want to tell them, ‘I’m considering using omega 3s or zinc.’ Regrettably, most times physicians don’t say, ‘Let’s examine that. Let’s look at the literature and see if that’s the right decision for you.’ By shutting a family down saying, ‘I don’t want to hear about that,’ it often leads the family to think: ‘How do I make a decision about this? How do I know what to do?’ ”

Dr. Hendren said clinicians are beginning to embrace the notion that autism is not just a brain disorder, but rather a whole body disorder. For example, he noted that significant subsets of people with autism have intestinal inflammation, digestive enzyme abnormalities, metabolic impairments, oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, and immunity problems that range from immune deficiency to hypersensitivity to autoimmunity. “,” said Dr. Hendren, professor of child and adolescent psychiatry at the University of California, San Francisco. “I hope that by thinking about making the body healthier, we can help kids have the very best outcomes.”

Several biomedical treatments have adequate evidence to use for many patients, he said, including melatonin, probiotics, omega 3s, and possibly vitamin D3, methyl B12, oxytocin, restrictive diets, digestive enzymes, and choline. “There are strong anecdotal reports of gluten-free diet benefits,” said Dr. Hendren, who also directs the UCSF Program for Research on Neurodevelopmental and Translational Outcomes. “Some parents I greatly respect tell me it’s the single most important thing they’ve done in their child’s health, that their GI symptoms have improved, and their overall health has improved.”

In a multisite trial called aViation, researchers are evaluating the effects of an investigational vasopressin antagonist in autistic patients aged 5-17 years. The drug works by blocking a brain receptor of the vasopressin receptor that is associated with control of stress, anxiety, affection, and aggression. “The first trial in adults showed potential benefit,” Dr. Hendren said.

No robust studies exist to suggest that medical marijuana makes a difference for patients with autism, he said, but he has several patients whose parents give their affected child medical marijuana or cannabidiol. “I have a number of families who say it’s really made a big difference for their children and for how they’re doing,” he said.

In Marin County, Calif., the Oak Hill School serves a heterogeneous population of children, adolescents, and young adults, all of whom have autism spectrum disorder (ASD) or other neurologically based disorders of relating and communicating. Students receive special education instruction and customized on-site clinical programs that might include speech/language pathology, occupational therapy, and group and individual psychotherapy. Some of the students have received recent functional behavior analyses from Dr. Hendren and his colleagues, with school staff implementing positive behavior intervention programs.

The researchers also are using metabolomics as a biomarker of outcome. “We’re using metabolomics from the urine, where we can look at these processes in different clusters and see whether our interventions make a difference or not,” said Dr. Hendren, who is a past president of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. “We did one trial with sulforaphane, which is a concentrated broccoli sprout extract that helps with oxidative stress. It was initially developed to treat oxidative stress in cancer,” he said. Upcoming trials in this cohort include the use of folinic acid and CM-AT, a pancreatic digestive enzyme intended to increase levels of chymotrypsin.

“I think of autism as being a disorder where you have this person and there’s a veil of autism that comes over the top of them,” he said. “That veil is not the kid, although the kid becomes more and more expressed through that. If we can do something to lift that veil, we can do more and more to pull that child out.”

Dr. Hendren disclosed that he has received grants from Curemark, Roche, Shire, and Sunovion. He is a member of the advisory boards for Curemark, BioMarin, Janssen, and Axial Biotherapeutics.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM NPA 2019

Supplements and food-related therapy do not prevent depression in overweight adults

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Though links between mental and physical health disorders have been established, this study from Bot et al. reinforces the murkiness of a nascent field like nutritional psychiatry, according to Michael Berk, MD, PhD, and Felice N. Jacka, PhD, of Deakin University in Victoria, Australia.

“Prevention of major depressive disorder is difficult to study,” they wrote, which makes a trial like this so important. However, its findings also emphasize the ambiguous nature of oft-touted remedies, specifically the “liberal and mostly non–evidence-based use of nutrient supplement combinations for psychiatric disorders.”

This study raises as many questions as it answers. Only 71% of those in the food-related behavioral activation therapy group attended more than 8 of the 21 offered sessions, and there is no way to prove how many followed the dietary restrictions. Those who did attend at least of 8 the sessions “showed a significant reduction in risk of depression,” however, which supports other trials that have associated dietary adherence and symptom improvement.

Diet is not a sole treatment for depression. However, the authors acknowledged that it is likely a piece of the complex puzzle that nutritional psychiatry wishes to solve. “These recent findings,” they wrote, “highlight that an integrated care package incorporating first-line psychological and pharmacological treatments, along with evidence-based lifestyle interventions addressing ... diet quality, may have a more robust effect on this burdensome disorder.”

These comments are adapted from an accompanying editorial (JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0273 ). Both coauthors reported conflicts of interest, including receiving grants, consulting fees, and research support from numerous boards, pharmaceutical companies, and foundations.

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

Multinutrient supplements and food-related therapy, together or separately, do not reduce major depressive disorder (MDD) episodes, according to a clinical trial of overweight adults with subsyndromal depressive symptoms.

“These findings do not support the use of these interventions for prevention of major depressive disorder in this population,” wrote lead author Mariska Bot, PhD, of Amsterdam University Medical Center, and her coauthors. The study was published in JAMA.

For this randomized clinical trial, Dr. Bot and her colleagues recruited 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries. All had at least mild depressive symptoms – determined through Patient Health Questionnaire–9 scores of 5 or higher – but no MDD episode in the last 6 months. The patients were allocated into four groups: placebo without therapy (n = 257), placebo with therapy (n = 256), supplements without therapy (n = 256), and supplements with therapy (n = 256). The supplements included 1,412 mg of omega-3 fatty acids, 30 mcg of selenium, 400 mcg of folic acid, and 20 mcg of vitamin D3 plus 100 mg of calcium. The therapy sessions were focused on food-related behavioral activation and emphasized a Mediterranean-style diet.

Only 779 (76%) of the patients completed the trial. Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode during 12-month follow-up, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy. Three of the four groups had 24 patients hospitalized, and the supplements-only group saw 26 patients hospitalized.

“This study showed that multinutrient supplements containing omega-3 [polyunsaturated fatty acids], vitamin D, folic acid, and selenium neither reduced depressive symptoms, anxiety symptoms nor improved health utility measures,” Dr. Bot and her coauthors wrote. “In fact, they appeared to result in slightly poorer depressive and anxiety symptoms scores compared with placebo.”

, roughly a quarter of patients lost to follow-up, and the likelihood that patients in the placebo group might have realized that they were not taking a multivitamin. In addition, participants were not selected based on deficiencies in the nutrients provided, making it possible that “deficient individuals will be more likely to benefit from supplementation.”

The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

SOURCE: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: A combination of multinutrient supplements and food-related behavioral activation therapy did not reduce episodes of major depressive disorder in overweight adults.

Major finding: Of the 105 participants who developed an MDD episode, 25 (9.7%) were receiving placebo alone, 26 (10.2%) were receiving placebo with therapy, 32 (12.5%) were receiving supplements alone, and 22 (8.6%) were receiving supplements with therapy.

Study details: A 2 x 2 factorial randomized clinical trial of 1,025 overweight adults from four European countries with elevated depressive symptoms and no major depressive disorder episode in the past 6 months.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the European Union FP7 MooDFOOD Project Multi-country Collaborative Project on the Role of Diet, Food-related Behavior, and Obesity in the Prevention of Depression. Dr. Bot reported no disclosures. Her coauthors reported receiving funding from numerous pharmaceutical companies, the European Union, and Guilford Press.

Source: Bot M et al. JAMA. 2019 Mar 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0556.

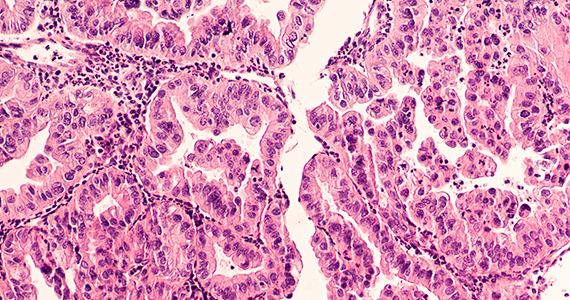

2019 Update on gynecologic cancer

Of the major developments in 2018 that changed practice in gynecologic oncology, we highlight 3 here.

First, a trial on the use of hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy (HIPEC) for patients with ovarian cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy demonstrated an overall survival benefit of 12 months for patients treated with HIPEC. Second, a trial on polyadenosine diphosphate-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors as maintenance therapy after adjuvant chemotherapy showed that women with a BRCA mutation had a progression-free survival benefit of nearly 3 years. Third, the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer trial revealed a significant decrease in survival in women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy compared with those who had the traditional open approach. In addition, a retrospective study that analyzed information from large cancer databases showed that national survival rates decreased for patients with cervical cancer as the use of laparoscopic radical hysterectomy rose.

In this Update, we summarize the major findings of these trials, provide background on treatment strategies, and discuss how our practice as cancer specialists has changed in light of these studies' findings.

HIPEC improves overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer—by a lot

Van Driel WJ, Koole SN, Sikorska K, et al. Hyperthermic intraperitoneal chemotherapy in ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:230-240.

In the United States, women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer typically are treated with primary cytoreductive (debulking) surgery followed by platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy. The goal of cytoreductive surgery is the resection of all grossly visible tumor. While associated with favorable oncologic outcomes, cytoreductive surgery also is accompanied by significant morbidity, and surgery is not always feasible.

Neoadjuvant chemotherapy (NACT) has emerged as an alternative treatment strategy to primary cytoreductive surgery. Women treated with NACT typically undergo 3 to 4 cycles of platinum- and taxane-based chemotherapy, receive interval cytoreduction, and then are treated with an additional 3 to 4 cycles of chemotherapy postoperatively. Several large, randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that survival is similar for women with advanced-stage ovarian cancer treated with either primary cytoreduction or NACT.1,2 Importantly, perioperative morbidity is substantially lower with NACT and the rate of complete tumor resection is improved. Use of NACT for ovarian cancer has increased substantially in recent years.3

Rationale for intraperitoneal chemotherapy

Intraperitoneal (IP) chemotherapy has long been utilized in the treatment of ovarian cancer.4 Given that the abdomen is the most common site of metastatic spread for ovarian cancer, there is a strong rationale for direct infusion of chemotherapy into the abdominal cavity. Several early trials showed that adjuvant IP chemotherapy improves survival compared with intravenous chemotherapy alone.5,6 Yet complete adoption of IP chemotherapy has been limited by evidence of moderately increased toxicities, such as pain, infections, and bowel obstructions, as well as IP catheter complications.5,7

Heated IP chemotherapy for recurrent ovarian cancer

More recently, interest has focused on HIPEC. In this approach, chemotherapy is heated to 42°C and administered into the abdominal cavity immediately after cytoreductive surgery; a temperature of 40°C to 41°C is maintained for total perfusion over a 90-minute period. The increased temperature induces apoptosis and protein degeneration, leading to greater penetration by the chemotherapy along peritoneal surfaces.8

For ovarian cancer, HIPEC has been explored in a number of small studies, predominately for women with recurrent disease.9 These studies demonstrated that HIPEC increased toxicities with gastrointestinal and renal complications but improved overall and disease-free survival.

HIPEC for primary treatment

Van Driel and colleagues explored the safety and efficacy of HIPEC for the primary treatment of ovarian cancer.10 In their multicenter trial, the authors sought to determine if there was a survival benefit with HIPEC in patients with stage III ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer treated with NACT. Eligible participants initially were treated with 3 cycles of chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel. Two-hundred forty-five patients who had a response or stable disease were then randomly assigned to undergo either interval cytoreductive surgery alone or surgery with HIPEC using cisplatin. Both groups received 3 additional cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel after surgery.

Results. Treatment with HIPEC was associated with a 3.5-month improvement in recurrence-free survival compared with surgery alone (14.2 vs 10.7 months) and a 12-month improvement in overall survival (45.7 vs 33.9 months). After a median follow-up of 4.7 years, 62% of patients in the surgery group and 50% of the patients in the HIPEC group had died.

Adverse events. Rates of grade 3 and 4 adverse events were similar for both treatment arms (25% in the surgery group vs 27% in the HIPEC plus surgery group), and there was no significant difference in hospital length of stay (8 vs 10 days, which included a mandatory 1-night stay in the intensive care unit for HIPEC-treated patients).

For carefully selected women with advanced ovarian cancer treated with neoadjuvant chemotherapy, HIPEC at the time of interval cytoreductive surgery may improve survival by a year.

Continue to: PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer...

PARP inhibitors extend survival in ovarian cancer, especially for women with a BRCA mutation

Moore K, Colombo N, Scambia G, et al. Maintenance olaparib in patients with newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2495-2505.

Ovarian cancer is the deadliest malignancy affecting women in the United States. While patients are likely to respond to their initial chemotherapy and surgery, there is a significant risk for cancer recurrence, from which the high mortality rates arise.

Maintenance therapy has considerable potential for preventing recurrences. Based on the results of a large Gynecologic Oncology Group study,11 in 2017 the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved bevacizumab for use in combination with and following standard carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for women with advanced ovarian cancer. In the trial, maintenance therapy with 10 months of bevacizumab improved progression-free survival by 4 months; however, it did not improve overall survival, and adverse events included bowel perforations and hypertension.11 Alternative targets for maintenance therapy to prevent or minimize the risk of recurrence in women with ovarian cancer have been actively investigated.

PARP inhibitors work by damaging cancer cell DNA

PARP is a key enzyme that repairs DNA damage within cells. Drugs that inhibit PARP trap this enzyme at the site of single-strand breaks, disrupting single-strand repair and inducing double-strand breaks. Since the homologous recombination pathway used to repair double-strand DNA breaks does not function in BRCA-mutated tissues, PARP inhibitors ultimately induce targeted DNA damage and apoptosis in both germline and somatic BRCA mutation carriers.12

In the United States, 3 PARP inhibitors (olaparib, niraparib, and rucaparib) are FDA approved as maintenance therapy for use in women with recurrent ovarian cancer that had responded completely or partially to platinum-based chemotherapy, regardless of BRCA status. PARP inhibitors also have been approved for treatment of advanced ovarian cancer in BRCA mutation carriers who have received 3 or more lines of platinum-based chemotherapy. Because of their efficacy in the treatment of recurrent ovarian cancer, there is great interest in using PARP inhibitors earlier in the disease course.

Olaparib is effective in women with BRCA mutations

In an international, randomized, double-blind, phase 3 trial, Moore and colleagues sought to determine the efficacy of the PARP inhibitor olaparib administered as maintenance therapy in women with germline or somatic BRCA mutations.13 Women were eligible if they had BRCA1 or BRCA2 mutations with newly diagnosed advanced (stage III or IV) ovarian, fallopian tube, or peritoneal cancer and a complete or partial response to platinum-based chemotherapy after cytoreduction.

Women were randomly assigned in a 2:1 ratio, with 260 participants receiving twice daily olaparib and 131 receiving placebo.

Results. After 41 months of follow-up, the disease-free survival rate was 60% in the olaparib group, compared with 27% in the placebo arm. Progression-free survival was 36 months longer in the olaparib maintenance group than in the placebo group.

Adverse events. While 21% of women treated with olaparib experienced serious adverse events (compared with 12% in the placebo group), most were related to anemia. Acute myeloid leukemia occurred in 3 (1%) of the 260 patients receiving olaparib.

For women with deleterious BRCA1 and/or BRCA2 mutations, administering PARP inhibitors as a maintenance therapy following primary treatment with the standard platinum-based chemotherapy improves progression-free survival by at least 3 years.

Continue to: Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Is MIS radical hysterectomy (vs open) for cervical cancer safe?

Ramirez PT, Frumovitz M, Pareja R, et al. Minimally invasive versus abdominal radical hysterectomy for cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1895-1904.

Melamed A, Margul DJ, Chen L, et al. Survival after minimally invasive radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1905-1914.

For various procedures, minimally invasive surgery (MIS) is associated with decreased blood loss, shorter postoperative stay, and decreased postoperative complications and readmission rates. In oncology, MIS has demonstrated equivalent outcomes compared with open procedures for colorectal and endometrial cancers.14,15

Increasing use of MIS in cervical cancer

For patients with cervical cancer, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy has more favorable perioperative outcomes, less morbidity, and decreased costs than open radical hysterectomy.16-20 However, many of the studies used to justify these benefits were small, lacked adequate follow-up, and were not adequately powered to detect a true survival difference. Some trials compared contemporary MIS enrollees to historical open surgery controls, who may have had more advanced-stage disease and may have been treated with different adjuvant chemoradiation.

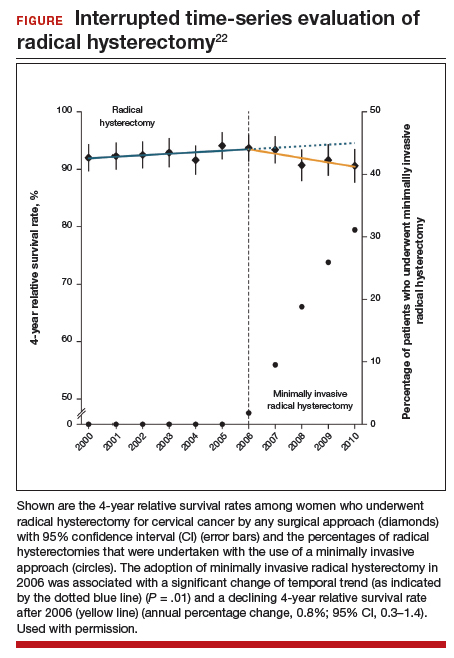

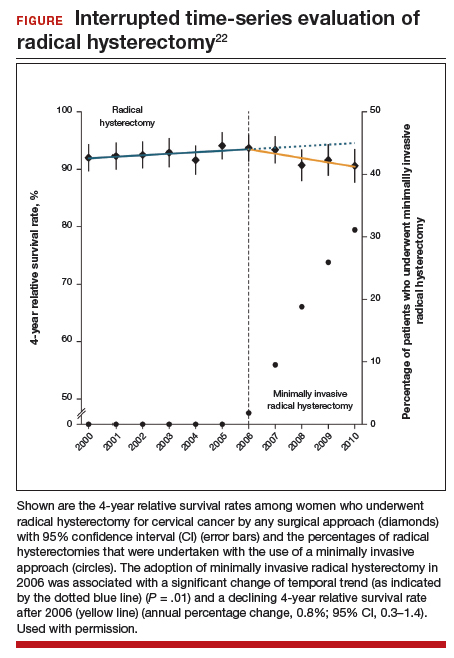

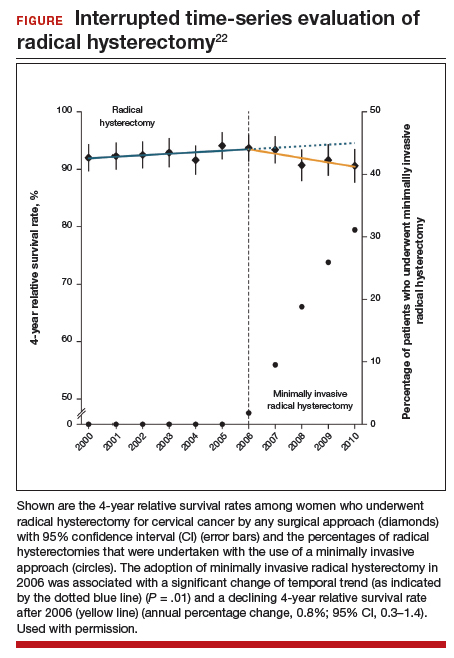

Despite these major limitations, minimally invasive radical hysterectomy became an acceptable—and often preferable—alternative to open radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. This acceptance was written into National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines,21 and minimally invasive radical hysterectomy rapidly gained popularity, increasing from 1.8% in 2006 to 31% in 2010.22

Randomized trial revealed surprising findings

Ramirez and colleagues recently published the results of the Laparoscopic Approach to Cervical Cancer (LACC) trial, a randomized controlled trial that compared open with minimally invasive radical hysterectomy in women with stage IA1-IB1 cervical cancer.23 The study was designed as a noninferiority trial in which researchers set a threshold of -7.2% for how much worse the survival of MIS patients could be compared with open surgery before MIS could be declared an inferior treatment. A total of 631 patients were enrolled at 33 centers worldwide. After an interim analysis demonstrated a safety signal in the MIS radical hysterectomy cohort, the study was closed before completion of enrollment.

Overall, 91% of patients randomly assigned to treatment had stage IB1 tumors. At the time of analysis, nearly 60% of enrollees had survival data at 4.5 years to provide adequate power for full analysis.

Results. Disease-free survival (the time from randomization to recurrence or death from cervical cancer) was 86.0% in the MIS group and 96.5% in the open hysterectomy group. At 4.5 years, 27 MIS patients had recurrent disease, compared with 7 patients who underwent abdominal radical hysterectomy. There were 14 cancer-related deaths in the MIS group, compared with 2 in the open group.

Three-year disease-free survival was 91.2% in the MIS group versus 97.1% in the abdominal radical hysterectomy group (hazard ratio, 3.74; 95% confidence interval, 1.63-8.58) The overall 3-year survival was 93.8% in the MIS group, compared with 99.0% in the open group.23

Retrospective cohort study had similar results

Concurrent with publication of the LACC trial results, Melamed and colleagues published an observational study on the safety of MIS radical hysterectomy for early-stage cervical cancer.22 They used data from the National Cancer Database to examine 2,461 women with stage IA2-IB1 cervical cancer who underwent radical hysterectomy from 2010 to 2013. Approximately half of the women (49.8%) underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy.

Results. After a median follow-up of 45 months, the 4-year mortality rate was 9.1% among women who underwent MIS radical hysterectomy, compared with 5.3% for those who had an abdominal radical hysterectomy.

Using the complimentary Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registry dataset, the authors examined population-level trends in use of MIS radical hysterectomy and survival. From 2000 to 2006, when MIS radical hysterectomy was rarely utilized, 4-year survival for cervical cancer was relatively stable. After adoption of MIS radical hysterectomy in 2006, 4-year relative survival declined by 0.8% annually for cervical cancer (FIGURE).22

Both a randomized controlled trial and a large observational study demonstrated decreased survival for women with early-stage cervical cancer who underwent minimally invasive radical hysterectomy. Use of minimally invasive radical hysterectomy should be used with caution in women with early-stage cervical cancer.

- Vergote I, Trope CG, Amant F, et al; European Organization for Research and Treatment of Cancer–Gynaecological Cancer Group; NCIC Clinical Trials Group. Neoadjuvant chemotherapy or primary surgery in stage IIIC or IV ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:943-953.

- Kehoe S, Hook J, Nankivell M, et al. Primary chemotherapy versus primary surgery for newly diagnosed advanced ovarian cancer (CHORUS): an open-label, randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2015;386:249-257.

- Melamed A, Hinchcliff EM, Clemmer JT, et al. Trends in the use of neoadjuvant chemotherapy for advanced ovarian cancer in the United States. Gynecol Oncol. 2016;143:236-240.