User login

FDA approves omadacycline for pneumonia and skin infections

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

The, for treating community-acquired bacterial pneumonia (CABP) and acute bacterial skin and skin structure infections (ABSSSI) in adults, the manufacturer, Paratek, announced in a press release.

The company expects that omadacycline will be available in the first quarter of 2019. Administered once-daily in either oral or IV formulations, the antibiotic was effective and well tolerated across multiple trials, which altogether included almost 2,000 patients, according to Paratek. As part of the approval, the company has agreed to conduct postmarketing studies, specifically, more studies in CABP and in pediatric populations. “To reduce the development of drug-resistant bacteria and maintain the effectiveness of Nuzyra and other antibacterial drugs, Nuzyra should be used only to treat or prevent infections that are proven or strongly suspected to be caused by susceptible bacteria,” according to a statement in the indications section of the prescribing information.

Omadacycline is contraindicated for patients with a known hypersensitivity to the drug or any members of the tetracycline class of antibacterial drugs; hypersensitivity reactions have been observed, so use should be discontinued if one is suspected. Use of this drug during later stages of pregnancy can lead to irreversible discoloration of the infant’s teeth and inhibition of bone growth; it should also not be used during breastfeeding.

Because omadacycline is structurally similar to tetracycline class drugs, some adverse reactions to those drugs may be seen with this one, such as photosensitivity, pseudotumor cerebri, and antianabolic action. Adverse reactions known to have an association with omadacycline include nausea, vomiting, hypertension, insomnia, diarrhea, constipation, and increases of alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, and/or gamma-glutamyl transferase.

Drug interactions may occur with anticoagulants, so dosage of those drugs may need to be reduced while treating with omadacycline. Antacids also are believed to have a drug interaction – specifically, impairing absorption of omadacycline

Treating IBD in medical home reduces costs

DALLAS – In the midst of the ever-increasing costs of patient care for chronic disease, one model for care of a specific, complex condition is the medical home, according to a presentation at the American Gastroenterological Association’s Partners in Value meeting.

The medical home concept came out of pediatrics and primary care, where patients’ health care needs could vary greatly over several years but benefited from coordinated care, Miguel Regueiro, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine and chair of the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic, told attendees at the meeting.

The medical home is ideal for a disease such as inflammatory bowel disease because it brings together the different care providers essential for such a complex condition and allows for the kind of coordinated, holistic care that’s uncommon in America’s typically fragmented health care system.

The two key components of a specialist medical home are a population of patients whose principal care requires a specialist and a health plan partnership around a chronic disease. The major attributes of a medical home, he explained, are accessibility; comprehensive, coordinated care; compassionate, culturally sensitive, patient-and family-centered care; and team-based delivery.

After initially building an IBD medical home in Pittsburgh, Dr. Regueiro brought the concept to Cleveland Clinic and shared with attendees how he did it and the challenges and benefits it involved.

He advises starting with a small team and expanding as demands or needs dictate. He began with a GI specialist, a psychiatrist, a dietitian, a social worker, a nurse, and three in-house schedulers. The patient ratio was 500 patients per nurse and 1,000 patients per gastroenterologist, psychiatrist and dietitian.

Dr. Regueiro explained the patient flow through the medical home, starting with a preclinic referral and patient questionnaire. The actual visit moves from intake and triage to the actual exam to a comprehensive care plan involving all relevant providers, plus any necessary referrals to any outside services, such as surgery or pain management. The work continues, however, after the patient leaves the clinic, with follow-up calls and telemedicine follow-up, including psychosocial telemedicine.

The decision to include in-house schedulers is among the most important, though it may admittedly be one of the more difficult for those trying to build a medical home from the ground up.

“I think that central scheduling is the worst thing that’s ever happened to medicine,” Dr. Regueiro told attendees. It’s too depersonalized to serve patients well, he said. His center’s embedded schedulers begin the clinical experience from a patient’s first phone call. They ask patients their top three problems and the top three things they want from their visit.

“If we don’t ask our patients what they want, the focus becomes physician-centered instead of patient-centered,” Dr. Regueiro said, sharing anecdotes of patients who came in with problems, expectations, and requests that differed, sometimes dramatically, from what he anticipated. Many of these needs were psychosocial, and the medical home model is ideally suited to address them in tandem with physical medical care.

“I firmly believe that the secret sauce of all our medical homes is the psychosocial care of patients by understanding the interactions between biological and environmental factors in the mind-body illness interface,” he said.

The center also uses provider team huddles before meeting a patient at intake and then afterward for follow-up. Part of team communication involves identifying patients as “red,” “yellow,” or “green” based on the magnitude of their needs and care utilization.

“There are a lot of green-zone patients: They see you once a year and really don’t need the intensive care” his clinic can provide, he said. “We did as much as we could to keep the patient at home, in their community, at school, more than anything else,” Dr. Regueiro said. “It’s not just about their quality of life and disease but about the impact on their work-life balance.”

One way the clinic addressed those needs was by involving patient stakeholders to find out early on – as they were setting up the center – what the patient experience was and what needed to improve. As they learned about logistical issues that frustrated the patient experience, such as lost medical records, central scheduling, or inadequate parking, they could work to identify solutions – thereby also addressing patients’ psychosocial needs.

But Dr. Regueiro was upfront about the substantial investment and challenges involved in setting up an IBD medical home. He would not have been able to meet his relative-value unit targets in this model, so those were cut in half. When an audience member asked how the clinic successfully worked with a variety of commercial insurers given the billing challenges, Dr. Regueiro said he didn’t have a good answer, though several large insurers have approached him with interest in the model.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen, but the appetite seems to be there,” he said. “I do think the insurers are interested because of the cost [savings] part of this.”

Those cost savings showed up in the long-term outcomes. At the Pittsburgh center, total emergency department visits dropped by nearly half (47%) from the year before the medical home total care model was implemented to the year after, from 508 total ED visits among the patient population to 264 visits. Hospitalizations similarly declined by a third (36%), from 208 to 134.

Part of the reason for that decline, as Dr. Regueiro showed in a case study example, was halting the repetitive testing and interventions in the ED that did not actually address – or even find out – the patient’s needs, particularly when those needs were psychosocial. And many psychosocial needs could even be met outside the clinic: 35% of all behavioral visits were telemedicine.

Still, payment models remain a challenge for creating medical homes. Other challenges include preventing team burnout, which can also deter interest in this model in the first place, and the longitudinal coordination of care with the medical neighborhood.

Despite his caveats, Dr. Regueiro’s presentation made a strong impression on attendees.

Mark Tsuchiyose, MD, a gastroenterologist with inSite Digestive Health Care in Daly City, Calif., found the presentation “fantastic” and said using medical homes for chronic GI care is “unquestionably the right thing to do.” But the problem, again, is reimbursement and a payer model that works with a medical home, he said. Dr. Regueiro needed to reduce his relative-value unit targets and was able to get funding for the care team, including in-house schedulers, Dr. Tsuchiyose noted, and that’s simply not feasible for most providers in most areas right now.

Sanjay Sandhir, MD, of Dayton (Ohio) Gastroenterology, said he appreciated the discussion of patient engagement apps in the medical home and helping patients with anxiety, depression, stress, and other psychosocial needs. While acknowledging the payer hurdles to such a model, he expressed optimism.

“If we go to the payers, and the payers are willing to understand and can get their head around and accept [this model], and we can give good data, it’s possible,” Dr. Sandhir said. “It’s worked in other cities, but it has to be a paradigm shift in the way people think.”

John Garrett, MD, a gastroenterologist with Mission Health and Asheville (N.C.) Gastroenterology, said he found the talk – and the clinic itself – “truly amazing.”

“It truly requires a multidisciplinary approach to identify the problems your IBD patients have and manage them most effectively,” he said. But the model is also “incredibly labor-intensive,” he added.

“I think few of us could mobilize a team as large, effective, and well-funded as his, but I think we can all take pieces of that and do it on a much more economical level, and still get good results,” he said, pointing specifically to incorporating depression screenings and other psychosocial elements into care. “I think most important would be to identify whether significant psychosocial issues are present and be ready to treat those.”

Dr. Regueiro has consulted for Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB, and has received research grants from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda. Dr. Tsuchiyose, Dr. Sandhir, and Dr. Garrett had no disclosures.

Gastroenterology has released a special collection of IBD articles, which gathers the best IBD research published over the past 2 years. View it at https://www.gastrojournal.org/content/inflammatory_bowel_disease.

DALLAS – In the midst of the ever-increasing costs of patient care for chronic disease, one model for care of a specific, complex condition is the medical home, according to a presentation at the American Gastroenterological Association’s Partners in Value meeting.

The medical home concept came out of pediatrics and primary care, where patients’ health care needs could vary greatly over several years but benefited from coordinated care, Miguel Regueiro, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine and chair of the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic, told attendees at the meeting.

The medical home is ideal for a disease such as inflammatory bowel disease because it brings together the different care providers essential for such a complex condition and allows for the kind of coordinated, holistic care that’s uncommon in America’s typically fragmented health care system.

The two key components of a specialist medical home are a population of patients whose principal care requires a specialist and a health plan partnership around a chronic disease. The major attributes of a medical home, he explained, are accessibility; comprehensive, coordinated care; compassionate, culturally sensitive, patient-and family-centered care; and team-based delivery.

After initially building an IBD medical home in Pittsburgh, Dr. Regueiro brought the concept to Cleveland Clinic and shared with attendees how he did it and the challenges and benefits it involved.

He advises starting with a small team and expanding as demands or needs dictate. He began with a GI specialist, a psychiatrist, a dietitian, a social worker, a nurse, and three in-house schedulers. The patient ratio was 500 patients per nurse and 1,000 patients per gastroenterologist, psychiatrist and dietitian.

Dr. Regueiro explained the patient flow through the medical home, starting with a preclinic referral and patient questionnaire. The actual visit moves from intake and triage to the actual exam to a comprehensive care plan involving all relevant providers, plus any necessary referrals to any outside services, such as surgery or pain management. The work continues, however, after the patient leaves the clinic, with follow-up calls and telemedicine follow-up, including psychosocial telemedicine.

The decision to include in-house schedulers is among the most important, though it may admittedly be one of the more difficult for those trying to build a medical home from the ground up.

“I think that central scheduling is the worst thing that’s ever happened to medicine,” Dr. Regueiro told attendees. It’s too depersonalized to serve patients well, he said. His center’s embedded schedulers begin the clinical experience from a patient’s first phone call. They ask patients their top three problems and the top three things they want from their visit.

“If we don’t ask our patients what they want, the focus becomes physician-centered instead of patient-centered,” Dr. Regueiro said, sharing anecdotes of patients who came in with problems, expectations, and requests that differed, sometimes dramatically, from what he anticipated. Many of these needs were psychosocial, and the medical home model is ideally suited to address them in tandem with physical medical care.

“I firmly believe that the secret sauce of all our medical homes is the psychosocial care of patients by understanding the interactions between biological and environmental factors in the mind-body illness interface,” he said.

The center also uses provider team huddles before meeting a patient at intake and then afterward for follow-up. Part of team communication involves identifying patients as “red,” “yellow,” or “green” based on the magnitude of their needs and care utilization.

“There are a lot of green-zone patients: They see you once a year and really don’t need the intensive care” his clinic can provide, he said. “We did as much as we could to keep the patient at home, in their community, at school, more than anything else,” Dr. Regueiro said. “It’s not just about their quality of life and disease but about the impact on their work-life balance.”

One way the clinic addressed those needs was by involving patient stakeholders to find out early on – as they were setting up the center – what the patient experience was and what needed to improve. As they learned about logistical issues that frustrated the patient experience, such as lost medical records, central scheduling, or inadequate parking, they could work to identify solutions – thereby also addressing patients’ psychosocial needs.

But Dr. Regueiro was upfront about the substantial investment and challenges involved in setting up an IBD medical home. He would not have been able to meet his relative-value unit targets in this model, so those were cut in half. When an audience member asked how the clinic successfully worked with a variety of commercial insurers given the billing challenges, Dr. Regueiro said he didn’t have a good answer, though several large insurers have approached him with interest in the model.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen, but the appetite seems to be there,” he said. “I do think the insurers are interested because of the cost [savings] part of this.”

Those cost savings showed up in the long-term outcomes. At the Pittsburgh center, total emergency department visits dropped by nearly half (47%) from the year before the medical home total care model was implemented to the year after, from 508 total ED visits among the patient population to 264 visits. Hospitalizations similarly declined by a third (36%), from 208 to 134.

Part of the reason for that decline, as Dr. Regueiro showed in a case study example, was halting the repetitive testing and interventions in the ED that did not actually address – or even find out – the patient’s needs, particularly when those needs were psychosocial. And many psychosocial needs could even be met outside the clinic: 35% of all behavioral visits were telemedicine.

Still, payment models remain a challenge for creating medical homes. Other challenges include preventing team burnout, which can also deter interest in this model in the first place, and the longitudinal coordination of care with the medical neighborhood.

Despite his caveats, Dr. Regueiro’s presentation made a strong impression on attendees.

Mark Tsuchiyose, MD, a gastroenterologist with inSite Digestive Health Care in Daly City, Calif., found the presentation “fantastic” and said using medical homes for chronic GI care is “unquestionably the right thing to do.” But the problem, again, is reimbursement and a payer model that works with a medical home, he said. Dr. Regueiro needed to reduce his relative-value unit targets and was able to get funding for the care team, including in-house schedulers, Dr. Tsuchiyose noted, and that’s simply not feasible for most providers in most areas right now.

Sanjay Sandhir, MD, of Dayton (Ohio) Gastroenterology, said he appreciated the discussion of patient engagement apps in the medical home and helping patients with anxiety, depression, stress, and other psychosocial needs. While acknowledging the payer hurdles to such a model, he expressed optimism.

“If we go to the payers, and the payers are willing to understand and can get their head around and accept [this model], and we can give good data, it’s possible,” Dr. Sandhir said. “It’s worked in other cities, but it has to be a paradigm shift in the way people think.”

John Garrett, MD, a gastroenterologist with Mission Health and Asheville (N.C.) Gastroenterology, said he found the talk – and the clinic itself – “truly amazing.”

“It truly requires a multidisciplinary approach to identify the problems your IBD patients have and manage them most effectively,” he said. But the model is also “incredibly labor-intensive,” he added.

“I think few of us could mobilize a team as large, effective, and well-funded as his, but I think we can all take pieces of that and do it on a much more economical level, and still get good results,” he said, pointing specifically to incorporating depression screenings and other psychosocial elements into care. “I think most important would be to identify whether significant psychosocial issues are present and be ready to treat those.”

Dr. Regueiro has consulted for Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB, and has received research grants from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda. Dr. Tsuchiyose, Dr. Sandhir, and Dr. Garrett had no disclosures.

Gastroenterology has released a special collection of IBD articles, which gathers the best IBD research published over the past 2 years. View it at https://www.gastrojournal.org/content/inflammatory_bowel_disease.

DALLAS – In the midst of the ever-increasing costs of patient care for chronic disease, one model for care of a specific, complex condition is the medical home, according to a presentation at the American Gastroenterological Association’s Partners in Value meeting.

The medical home concept came out of pediatrics and primary care, where patients’ health care needs could vary greatly over several years but benefited from coordinated care, Miguel Regueiro, MD, AGAF, professor of medicine and chair of the department of gastroenterology, hepatology, and nutrition at the Cleveland Clinic, told attendees at the meeting.

The medical home is ideal for a disease such as inflammatory bowel disease because it brings together the different care providers essential for such a complex condition and allows for the kind of coordinated, holistic care that’s uncommon in America’s typically fragmented health care system.

The two key components of a specialist medical home are a population of patients whose principal care requires a specialist and a health plan partnership around a chronic disease. The major attributes of a medical home, he explained, are accessibility; comprehensive, coordinated care; compassionate, culturally sensitive, patient-and family-centered care; and team-based delivery.

After initially building an IBD medical home in Pittsburgh, Dr. Regueiro brought the concept to Cleveland Clinic and shared with attendees how he did it and the challenges and benefits it involved.

He advises starting with a small team and expanding as demands or needs dictate. He began with a GI specialist, a psychiatrist, a dietitian, a social worker, a nurse, and three in-house schedulers. The patient ratio was 500 patients per nurse and 1,000 patients per gastroenterologist, psychiatrist and dietitian.

Dr. Regueiro explained the patient flow through the medical home, starting with a preclinic referral and patient questionnaire. The actual visit moves from intake and triage to the actual exam to a comprehensive care plan involving all relevant providers, plus any necessary referrals to any outside services, such as surgery or pain management. The work continues, however, after the patient leaves the clinic, with follow-up calls and telemedicine follow-up, including psychosocial telemedicine.

The decision to include in-house schedulers is among the most important, though it may admittedly be one of the more difficult for those trying to build a medical home from the ground up.

“I think that central scheduling is the worst thing that’s ever happened to medicine,” Dr. Regueiro told attendees. It’s too depersonalized to serve patients well, he said. His center’s embedded schedulers begin the clinical experience from a patient’s first phone call. They ask patients their top three problems and the top three things they want from their visit.

“If we don’t ask our patients what they want, the focus becomes physician-centered instead of patient-centered,” Dr. Regueiro said, sharing anecdotes of patients who came in with problems, expectations, and requests that differed, sometimes dramatically, from what he anticipated. Many of these needs were psychosocial, and the medical home model is ideally suited to address them in tandem with physical medical care.

“I firmly believe that the secret sauce of all our medical homes is the psychosocial care of patients by understanding the interactions between biological and environmental factors in the mind-body illness interface,” he said.

The center also uses provider team huddles before meeting a patient at intake and then afterward for follow-up. Part of team communication involves identifying patients as “red,” “yellow,” or “green” based on the magnitude of their needs and care utilization.

“There are a lot of green-zone patients: They see you once a year and really don’t need the intensive care” his clinic can provide, he said. “We did as much as we could to keep the patient at home, in their community, at school, more than anything else,” Dr. Regueiro said. “It’s not just about their quality of life and disease but about the impact on their work-life balance.”

One way the clinic addressed those needs was by involving patient stakeholders to find out early on – as they were setting up the center – what the patient experience was and what needed to improve. As they learned about logistical issues that frustrated the patient experience, such as lost medical records, central scheduling, or inadequate parking, they could work to identify solutions – thereby also addressing patients’ psychosocial needs.

But Dr. Regueiro was upfront about the substantial investment and challenges involved in setting up an IBD medical home. He would not have been able to meet his relative-value unit targets in this model, so those were cut in half. When an audience member asked how the clinic successfully worked with a variety of commercial insurers given the billing challenges, Dr. Regueiro said he didn’t have a good answer, though several large insurers have approached him with interest in the model.

“I don’t know what’s going to happen, but the appetite seems to be there,” he said. “I do think the insurers are interested because of the cost [savings] part of this.”

Those cost savings showed up in the long-term outcomes. At the Pittsburgh center, total emergency department visits dropped by nearly half (47%) from the year before the medical home total care model was implemented to the year after, from 508 total ED visits among the patient population to 264 visits. Hospitalizations similarly declined by a third (36%), from 208 to 134.

Part of the reason for that decline, as Dr. Regueiro showed in a case study example, was halting the repetitive testing and interventions in the ED that did not actually address – or even find out – the patient’s needs, particularly when those needs were psychosocial. And many psychosocial needs could even be met outside the clinic: 35% of all behavioral visits were telemedicine.

Still, payment models remain a challenge for creating medical homes. Other challenges include preventing team burnout, which can also deter interest in this model in the first place, and the longitudinal coordination of care with the medical neighborhood.

Despite his caveats, Dr. Regueiro’s presentation made a strong impression on attendees.

Mark Tsuchiyose, MD, a gastroenterologist with inSite Digestive Health Care in Daly City, Calif., found the presentation “fantastic” and said using medical homes for chronic GI care is “unquestionably the right thing to do.” But the problem, again, is reimbursement and a payer model that works with a medical home, he said. Dr. Regueiro needed to reduce his relative-value unit targets and was able to get funding for the care team, including in-house schedulers, Dr. Tsuchiyose noted, and that’s simply not feasible for most providers in most areas right now.

Sanjay Sandhir, MD, of Dayton (Ohio) Gastroenterology, said he appreciated the discussion of patient engagement apps in the medical home and helping patients with anxiety, depression, stress, and other psychosocial needs. While acknowledging the payer hurdles to such a model, he expressed optimism.

“If we go to the payers, and the payers are willing to understand and can get their head around and accept [this model], and we can give good data, it’s possible,” Dr. Sandhir said. “It’s worked in other cities, but it has to be a paradigm shift in the way people think.”

John Garrett, MD, a gastroenterologist with Mission Health and Asheville (N.C.) Gastroenterology, said he found the talk – and the clinic itself – “truly amazing.”

“It truly requires a multidisciplinary approach to identify the problems your IBD patients have and manage them most effectively,” he said. But the model is also “incredibly labor-intensive,” he added.

“I think few of us could mobilize a team as large, effective, and well-funded as his, but I think we can all take pieces of that and do it on a much more economical level, and still get good results,” he said, pointing specifically to incorporating depression screenings and other psychosocial elements into care. “I think most important would be to identify whether significant psychosocial issues are present and be ready to treat those.”

Dr. Regueiro has consulted for Abbvie, Allergan, Amgen, Celgene, Janssen, Pfizer, Takeda, and UCB, and has received research grants from Abbvie, Janssen, and Takeda. Dr. Tsuchiyose, Dr. Sandhir, and Dr. Garrett had no disclosures.

Gastroenterology has released a special collection of IBD articles, which gathers the best IBD research published over the past 2 years. View it at https://www.gastrojournal.org/content/inflammatory_bowel_disease.

REPORTING FROM 2018 AGA PARTNERS IN VALUE

Shelved GLP-1 agonist reduced cardiovascular risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus

BERLIN – Albiglutide, a glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist, added on top of the standard of care reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with established cardiovascular disease by a significant 22% versus placebo in the HARMONY Outcomes trial, according to results reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The trial’s findings, which were published simultaneously in the Lancet, have added “further support that evidence-based GLP-1 receptor agonists should be part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce the risk for cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes as recommended by recent cardiology and diabetes guidelines,” said study investigator Lawrence Leiter, MD.

Albiglutide was approved for the treatment of T2DM by the European Medicines Agency as Eperzan and by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States as Tanzeum in 2014. Last year, however, its manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline, announced that it would cease further research and development, manufacturing, and sales activity for albiglutide. Nevertheless, the company remained committed to completing the HARMONY Outcomes trial, begun in 2015.

In a press release issued by GSK on Oct. 2, 2018, the same day as the trial’s findings were revealed, John Lepore, MD, the senior vice president of GSK’s R&D pipeline said, “HARMONY Outcomes was an important study for us to complete to generate new data and insights about the role of the GLP-1 receptor agonist class in the management of patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Lepore added, “GSK continued to invest in this study… and we continue to explore opportunities to divest this medicine to a company with the right expertise and resources to realize its full potential for patients.”

During his summing up of the HARMONY Outcomes data, Dr. Leiter of the University of Toronto observed that all components of the composite primary endpoint – which included MI, cardiovascular death, and stroke – were “directionally consistent with overall benefit.” However, it was the 25% reduction in MI that drove the overall benefit seen.

With an average duration of follow-up of just 1.6 years, it was no wonder perhaps that no effect on a long-term outcome such as cardiovascular death was seen, Dr. Leiter suggested. Insufficient trial length was a fact picked up by the independent commentator for the trial David Matthews, MD, professor of diabetic medicine at the University of Oxford (England).

“HARMONY recruited patients who were extremely near the edge of a cliff,” Dr. Matthews observed, noting that, if a trial was to be completed in such a short span of time, a very-high-risk population needed to be recruited.

Indeed, 100% of the study population in the trial had cardiovascular disease; specifically, 70% had coronary artery disease, 47% had a prior MI, 43% had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, and 25% had peripheral arterial disease. In addition, 86% had hypertension, 20% had heart failure, and 18% had experienced a stroke. Furthermore, the average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) at baseline was 8.7%.

When you are thinking about trial design, you want to recruit patients who are near the edge so that you see lots of events, but not too near such that treatment makes no difference and not too far from the edge or the trial will go on and on, Dr. Matthews observed.

With regards to the primary composite endpoint, he noted that no adjustment of the significance level was needed to test the superiority of albiglutide over placebo. The hazard ratio was 0.78, with a P value of less than .0001 for noninferiority and P = .0006 for superiority, and event rates per 100 patient-years were 4.57 for albiglutide and 5.87 for placebo.

The mean change in HbA1c over time was greater with albiglutide than with placebo, with a between-group difference of –0.63% at 8 months and –0.52% at 16 months. These data suggest that albiglutide seems to have weaker effects than semaglutide, Dr. Matthews noted.

“The odd thing about albiglutide was the weight didn’t change,” Dr. Matthews observed when discussing some of the secondary endpoints. The difference in body weight between albiglutide and placebo was –0.66 kg at 8 months and –0.83 kg at 16 months.

If the results on body mass index with another GLP-1 agonist, semaglutide, were considered, effects on body weight in the HARMONY Outcomes trial were negligible, Dr. Matthews added. This point was something Twitter users also commented on.

“The weight loss is really modest with albiglutide in HARMONY”, said Abd Tahrani, MD, an National Institute for Health Research clinician scientist at the University of Birmingham (U.K.) and an honorary consultant endocrinologist the Heart of England National Health Service Foundation Trust in Birmingham.

Syed Gilani, MD, a general practitioner and champion for Diabetes UK, as well as being a clinical research fellow in diabetes and senior lecturer at the University of Wolverhampton (England), agreed and tweeted: “Is there a hint of GLP-1 class effect?”

While another U.K. diabetes consultant, Partha Kar, MD, a diabetes consultant and endocrinologist at Queen Alexandria Hospital, Portsmouth, England, tweeted: “Game-changer or confirmatory of class effect with better options available?”

The lack of a weight effect could be an advantage of course, Dr. Matthews observed; differences in the GLP-1 agonists could be matched to patients’ needs, with those you do not want to lose weight being given albiglutide.

In an editorial also published in the Lancet (2018 Oct 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[18]32348-1), Marion Mafham and David Preiss, PhD, who are both from the University of Oxford, observed that “given the clear cardiovascular benefit observed with albiglutide … GlaxoSmithKline should reconsider making it available to patients.”

Ms. Mafham and Dr. Preiss also noted in their comments that, while there has been inconsistency among GLP-1 trials, the HARMONY Outcomes data now add to the evidence of a cardiovascular benefit as seen in the SUSTAIN-6 trial with semaglutide and in the LEADER trial with liraglutide.

“International guidelines should reflect the increasing weight of evidence that supports the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease,” the editorialists wrote.

The study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Leiter was an investigator in the study and disclosed receiving research funding and honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis, as well as honoraria from Servier. Dr. Lepore is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Matthews disclosed acting as an advisory board member for and receiving consulting fees or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Janssen, and Servier. Ms. Mafham has no competing interests. Dr. Preiss is an investigator in a trial funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

SOURCE: Hernandez AF et al. Lancet. 2018 Oct 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32261-X.

BERLIN – Albiglutide, a glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist, added on top of the standard of care reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with established cardiovascular disease by a significant 22% versus placebo in the HARMONY Outcomes trial, according to results reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The trial’s findings, which were published simultaneously in the Lancet, have added “further support that evidence-based GLP-1 receptor agonists should be part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce the risk for cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes as recommended by recent cardiology and diabetes guidelines,” said study investigator Lawrence Leiter, MD.

Albiglutide was approved for the treatment of T2DM by the European Medicines Agency as Eperzan and by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States as Tanzeum in 2014. Last year, however, its manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline, announced that it would cease further research and development, manufacturing, and sales activity for albiglutide. Nevertheless, the company remained committed to completing the HARMONY Outcomes trial, begun in 2015.

In a press release issued by GSK on Oct. 2, 2018, the same day as the trial’s findings were revealed, John Lepore, MD, the senior vice president of GSK’s R&D pipeline said, “HARMONY Outcomes was an important study for us to complete to generate new data and insights about the role of the GLP-1 receptor agonist class in the management of patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Lepore added, “GSK continued to invest in this study… and we continue to explore opportunities to divest this medicine to a company with the right expertise and resources to realize its full potential for patients.”

During his summing up of the HARMONY Outcomes data, Dr. Leiter of the University of Toronto observed that all components of the composite primary endpoint – which included MI, cardiovascular death, and stroke – were “directionally consistent with overall benefit.” However, it was the 25% reduction in MI that drove the overall benefit seen.

With an average duration of follow-up of just 1.6 years, it was no wonder perhaps that no effect on a long-term outcome such as cardiovascular death was seen, Dr. Leiter suggested. Insufficient trial length was a fact picked up by the independent commentator for the trial David Matthews, MD, professor of diabetic medicine at the University of Oxford (England).

“HARMONY recruited patients who were extremely near the edge of a cliff,” Dr. Matthews observed, noting that, if a trial was to be completed in such a short span of time, a very-high-risk population needed to be recruited.

Indeed, 100% of the study population in the trial had cardiovascular disease; specifically, 70% had coronary artery disease, 47% had a prior MI, 43% had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, and 25% had peripheral arterial disease. In addition, 86% had hypertension, 20% had heart failure, and 18% had experienced a stroke. Furthermore, the average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) at baseline was 8.7%.

When you are thinking about trial design, you want to recruit patients who are near the edge so that you see lots of events, but not too near such that treatment makes no difference and not too far from the edge or the trial will go on and on, Dr. Matthews observed.

With regards to the primary composite endpoint, he noted that no adjustment of the significance level was needed to test the superiority of albiglutide over placebo. The hazard ratio was 0.78, with a P value of less than .0001 for noninferiority and P = .0006 for superiority, and event rates per 100 patient-years were 4.57 for albiglutide and 5.87 for placebo.

The mean change in HbA1c over time was greater with albiglutide than with placebo, with a between-group difference of –0.63% at 8 months and –0.52% at 16 months. These data suggest that albiglutide seems to have weaker effects than semaglutide, Dr. Matthews noted.

“The odd thing about albiglutide was the weight didn’t change,” Dr. Matthews observed when discussing some of the secondary endpoints. The difference in body weight between albiglutide and placebo was –0.66 kg at 8 months and –0.83 kg at 16 months.

If the results on body mass index with another GLP-1 agonist, semaglutide, were considered, effects on body weight in the HARMONY Outcomes trial were negligible, Dr. Matthews added. This point was something Twitter users also commented on.

“The weight loss is really modest with albiglutide in HARMONY”, said Abd Tahrani, MD, an National Institute for Health Research clinician scientist at the University of Birmingham (U.K.) and an honorary consultant endocrinologist the Heart of England National Health Service Foundation Trust in Birmingham.

Syed Gilani, MD, a general practitioner and champion for Diabetes UK, as well as being a clinical research fellow in diabetes and senior lecturer at the University of Wolverhampton (England), agreed and tweeted: “Is there a hint of GLP-1 class effect?”

While another U.K. diabetes consultant, Partha Kar, MD, a diabetes consultant and endocrinologist at Queen Alexandria Hospital, Portsmouth, England, tweeted: “Game-changer or confirmatory of class effect with better options available?”

The lack of a weight effect could be an advantage of course, Dr. Matthews observed; differences in the GLP-1 agonists could be matched to patients’ needs, with those you do not want to lose weight being given albiglutide.

In an editorial also published in the Lancet (2018 Oct 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[18]32348-1), Marion Mafham and David Preiss, PhD, who are both from the University of Oxford, observed that “given the clear cardiovascular benefit observed with albiglutide … GlaxoSmithKline should reconsider making it available to patients.”

Ms. Mafham and Dr. Preiss also noted in their comments that, while there has been inconsistency among GLP-1 trials, the HARMONY Outcomes data now add to the evidence of a cardiovascular benefit as seen in the SUSTAIN-6 trial with semaglutide and in the LEADER trial with liraglutide.

“International guidelines should reflect the increasing weight of evidence that supports the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease,” the editorialists wrote.

The study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Leiter was an investigator in the study and disclosed receiving research funding and honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis, as well as honoraria from Servier. Dr. Lepore is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Matthews disclosed acting as an advisory board member for and receiving consulting fees or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Janssen, and Servier. Ms. Mafham has no competing interests. Dr. Preiss is an investigator in a trial funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

SOURCE: Hernandez AF et al. Lancet. 2018 Oct 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32261-X.

BERLIN – Albiglutide, a glucagonlike peptide–1 (GLP-1) agonist, added on top of the standard of care reduced the incidence of major cardiovascular events (MACE) in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) with established cardiovascular disease by a significant 22% versus placebo in the HARMONY Outcomes trial, according to results reported at the annual meeting of the European Association for the Study of Diabetes.

The trial’s findings, which were published simultaneously in the Lancet, have added “further support that evidence-based GLP-1 receptor agonists should be part of a comprehensive strategy to reduce the risk for cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes as recommended by recent cardiology and diabetes guidelines,” said study investigator Lawrence Leiter, MD.

Albiglutide was approved for the treatment of T2DM by the European Medicines Agency as Eperzan and by the Food and Drug Administration in the United States as Tanzeum in 2014. Last year, however, its manufacturer, GlaxoSmithKline, announced that it would cease further research and development, manufacturing, and sales activity for albiglutide. Nevertheless, the company remained committed to completing the HARMONY Outcomes trial, begun in 2015.

In a press release issued by GSK on Oct. 2, 2018, the same day as the trial’s findings were revealed, John Lepore, MD, the senior vice president of GSK’s R&D pipeline said, “HARMONY Outcomes was an important study for us to complete to generate new data and insights about the role of the GLP-1 receptor agonist class in the management of patients with diabetes and cardiovascular disease.”

Dr. Lepore added, “GSK continued to invest in this study… and we continue to explore opportunities to divest this medicine to a company with the right expertise and resources to realize its full potential for patients.”

During his summing up of the HARMONY Outcomes data, Dr. Leiter of the University of Toronto observed that all components of the composite primary endpoint – which included MI, cardiovascular death, and stroke – were “directionally consistent with overall benefit.” However, it was the 25% reduction in MI that drove the overall benefit seen.

With an average duration of follow-up of just 1.6 years, it was no wonder perhaps that no effect on a long-term outcome such as cardiovascular death was seen, Dr. Leiter suggested. Insufficient trial length was a fact picked up by the independent commentator for the trial David Matthews, MD, professor of diabetic medicine at the University of Oxford (England).

“HARMONY recruited patients who were extremely near the edge of a cliff,” Dr. Matthews observed, noting that, if a trial was to be completed in such a short span of time, a very-high-risk population needed to be recruited.

Indeed, 100% of the study population in the trial had cardiovascular disease; specifically, 70% had coronary artery disease, 47% had a prior MI, 43% had undergone percutaneous coronary intervention, and 25% had peripheral arterial disease. In addition, 86% had hypertension, 20% had heart failure, and 18% had experienced a stroke. Furthermore, the average hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) at baseline was 8.7%.

When you are thinking about trial design, you want to recruit patients who are near the edge so that you see lots of events, but not too near such that treatment makes no difference and not too far from the edge or the trial will go on and on, Dr. Matthews observed.

With regards to the primary composite endpoint, he noted that no adjustment of the significance level was needed to test the superiority of albiglutide over placebo. The hazard ratio was 0.78, with a P value of less than .0001 for noninferiority and P = .0006 for superiority, and event rates per 100 patient-years were 4.57 for albiglutide and 5.87 for placebo.

The mean change in HbA1c over time was greater with albiglutide than with placebo, with a between-group difference of –0.63% at 8 months and –0.52% at 16 months. These data suggest that albiglutide seems to have weaker effects than semaglutide, Dr. Matthews noted.

“The odd thing about albiglutide was the weight didn’t change,” Dr. Matthews observed when discussing some of the secondary endpoints. The difference in body weight between albiglutide and placebo was –0.66 kg at 8 months and –0.83 kg at 16 months.

If the results on body mass index with another GLP-1 agonist, semaglutide, were considered, effects on body weight in the HARMONY Outcomes trial were negligible, Dr. Matthews added. This point was something Twitter users also commented on.

“The weight loss is really modest with albiglutide in HARMONY”, said Abd Tahrani, MD, an National Institute for Health Research clinician scientist at the University of Birmingham (U.K.) and an honorary consultant endocrinologist the Heart of England National Health Service Foundation Trust in Birmingham.

Syed Gilani, MD, a general practitioner and champion for Diabetes UK, as well as being a clinical research fellow in diabetes and senior lecturer at the University of Wolverhampton (England), agreed and tweeted: “Is there a hint of GLP-1 class effect?”

While another U.K. diabetes consultant, Partha Kar, MD, a diabetes consultant and endocrinologist at Queen Alexandria Hospital, Portsmouth, England, tweeted: “Game-changer or confirmatory of class effect with better options available?”

The lack of a weight effect could be an advantage of course, Dr. Matthews observed; differences in the GLP-1 agonists could be matched to patients’ needs, with those you do not want to lose weight being given albiglutide.

In an editorial also published in the Lancet (2018 Oct 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736[18]32348-1), Marion Mafham and David Preiss, PhD, who are both from the University of Oxford, observed that “given the clear cardiovascular benefit observed with albiglutide … GlaxoSmithKline should reconsider making it available to patients.”

Ms. Mafham and Dr. Preiss also noted in their comments that, while there has been inconsistency among GLP-1 trials, the HARMONY Outcomes data now add to the evidence of a cardiovascular benefit as seen in the SUSTAIN-6 trial with semaglutide and in the LEADER trial with liraglutide.

“International guidelines should reflect the increasing weight of evidence that supports the use of GLP-1 receptor agonists in patients with type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease,” the editorialists wrote.

The study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Leiter was an investigator in the study and disclosed receiving research funding and honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis, as well as honoraria from Servier. Dr. Lepore is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Matthews disclosed acting as an advisory board member for and receiving consulting fees or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Janssen, and Servier. Ms. Mafham has no competing interests. Dr. Preiss is an investigator in a trial funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

SOURCE: Hernandez AF et al. Lancet. 2018 Oct 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32261-X.

REPORTING FROM EASD 2018

Key clinical point: The overall reduction was led by a reduction in the rate of MI.

Major finding: Albiglutide reduced the risk of major cardiovascular events by 22%, compared with placebo, in patients with T2DM and cardiovascular disease.

Study details: HARMONY Outcomes, a postapproval, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of once-weekly, subcutaneous albiglutide (30-50 mg) versus matched placebo in 9,463 randomized patients.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Leiter was an investigator in the study and disclosed receiving research funding and honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly, Janssen, Merck, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi Aventis, as well as honoraria from Servier. Dr. Lepore is an employee of GlaxoSmithKline. Dr. Matthews disclosed acting as an advisory board member for and receiving consulting fees or honoraria from GlaxoSmithKline, Novo Nordisk, Novartis, Eli Lilly, Sanofi Aventis, Janssen, and Servier. Dr. Mafham has no competing interests. Dr. Preiss is an investigator in a trial funded by Boehringer Ingelheim.

Source: Hernandez AF et al. Lancet. 2018 Oct 2. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32261-X.

Stridor in the Pediatric Patient

The distinct features of the pediatric airway make respiratory failure an important concern independent of the underlying cause.

Cases

Case 1

It’s a busy shift on an unusually chilly and rainy July night. Emergency medical services (EMS) brings in a 9-month-old boy who woke up with a “squeaking” noise. His parents reported that he has had a fever, cough, rhinorrhea, and difficulty breathing for the past 2 days; however, they did not hear the noisy breathing until the night of presentation. When the patient is examined, it is noted that he has inspiratory stridor at rest, moderate subcostal retractions, and an occasional deep cough. Upper airway transmitted noises were present, but otherwise the patient had clear lungs.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 85/55 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 163 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 55 breaths/min; and temperature (T), 101.8°F. Oxygen saturation was 90% on room air. The patient’s mother wants to know how the respiratory distress will be fixed and is inquiring if they will have to stay in the hospital overnight.

Case 2

As work begins on the child described above, EMS brings in a 3-year-old girl who appears to be in moderate-severe respiratory distress. Her parents report that she started to drool earlier in the day followed by coughing and occasional gagging. Her parents relay that they thought the symptoms were because of post-nasal drip due to her cold, but the respiratory distress seems to be getting worse, and she now has very noisy breathing and is reluctant to lay down. Upon examination, both inspiratory and expiratory stridor is heard, and it is noted that moderate subcostal retractions are present when the patient is supine.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: BP, 89/58 mm Hg; HR, 144 beats/min; RR, 52 breaths/min; and T, 99.5°F. Oxygen saturation was 88% on room air. The nursing staff asked what to do next and why the 2 stridor cases are being managed so differently.

Stridor

Stridor is a high-pitched, harsh sound heard during respiration, predominantly during inspiration, as a result of turbulent air passage.1-3 Stridor is not a diagnosis in itself, but rather a sign of underlying acute or chronic etiology, which needs to be classified based on elicited history and examination.1,4 While the etiology of obstruction may be infectious, congenital, mechanical, or traumatic, the distinct features of the pediatric airway make respiratory failure an important concern independent of the underlying cause.

Anatomy

There are several anatomical differences unique to the pediatric airway that make children, especially infants under 1 year of age, more susceptible to airway obstruction.5,6The pediatric larynx is more anterior and superior and less fibrous than adults, thereby more compliant.6,7 The pediatric epiglottis is longer, omega-shaped, and softer, and the tongue is larger in comparison to the size of the oral cavity, resulting in obstructed airflow.6,7 Children also have a larger and more prominent occiput, causing mechanical obstruction by flexion of the neck when supine.6 While the cricoid cartilage was previously believed to be the narrowest portion of the airway, more recent measurement techniques have challenged this and shown that the glottic and subglottic areas may be narrower in children.7,8

Worsening obstruction resulting in a decreased airway radius leads to increased turbulence to air flow, which is explained by Poiseuille’s law.1,2,7 The resistance to airflow becomes inversely related to the fourth power of the radius, so even a small change in an already narrow pediatric airway can make a huge difference.5 In practice, this means 1 mm of mucosal edema will decrease the cross-sectional area of the airway by 75% and increase the resistance of airflow by a magnitude of 16 to 32 times depending on the level of turbulence.7The airway can be divided into extrathoracic and intrathoracic regions, separated by the vocal cords.13 Inspiratory stridor is typically due to extrathoracic obstruction and expiratory stridor is due to intrathoracic obstruction below the level of the cords. Biphasic stridor, however, may indicate a fixed obstruction at the level of the cords.2,3,5,9

Acute Differentials

The pediatric patient is at high risk for respiratory decompensation when the upper airway is acutely compromised. The history, physical examination, and phases of stridor can help determine the underlying diagnosis and definitive treatment plan.

Acute Croup

Acute croup (laryngotracheitis) is a clinical diagnosis based on acute onset of barky cough and inspiratory stridor.1 It is usually secondary to an infection, most commonly viral (parainfluenza virus), resulting in edema and increased secretions of the subglottic mucosa.7 The onset is typically preceded by upper respiratory illness (URI) symptoms, and is often worse at night or after waking from a nap.1 The peak incidence is between ages 6 months to 3 years. While croup is a clinical diagnosis, an anteroposterior X-ray will often show a steeple sign.7,10

Spasmodic Croup

Spasmodic croup is an atypical presentation usually seen in children 8 years or older without a preceding URI. Patients will wake up overnight with a harsh brass-like cough, stridor, and hoarse voice. The etiology is unclear, but often these patients have a history of atopy and respond in part to treatment with antihistamines.

Foreign Body Aspiration

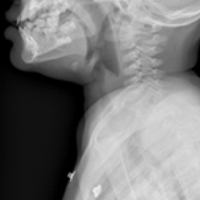

All that is acutely stridulous is not croup. Stridor from foreign body aspiration is sudden in onset and children do not always present with a history suggestive of foreign body aspiration. Diagnosis requires a high index of suspicion because the event is often unwitnessed and typical patients are pre-verbal. The physical examination may reveal diminished air entry along with stridor. Diagnosis is made by obtaining an X-ray (lateral neck [Figure 1], lateral decubitus, or inspiratory/expiratory chest X-ray) or by bronchoscopy which is both diagnostic and therapeutic.7,10 Remember to always think of foreign body aspiration in children with acute stridor who have neither fever nor antecedent URI symptoms.

Bacterial Tracheitis

Bacterial tracheitis should be suspected in toxic appearing children who present with respiratory distress and stridor but who have a poor response to nebulized epinephrine. It is typically seen in toddlers and school-aged children, and like a viral tracheitis, presentation can be preceded by either URI or fever.10 Stridor is caused by subglottic edema and mucopurulent secretions in the airway.7,10 Infection is most commonly by S. aureus but initial antibiotic choice should be broad spectrum, and include a third-generation cephalosporin or beta-lactamase resistant penicillin.

Epiglottitis

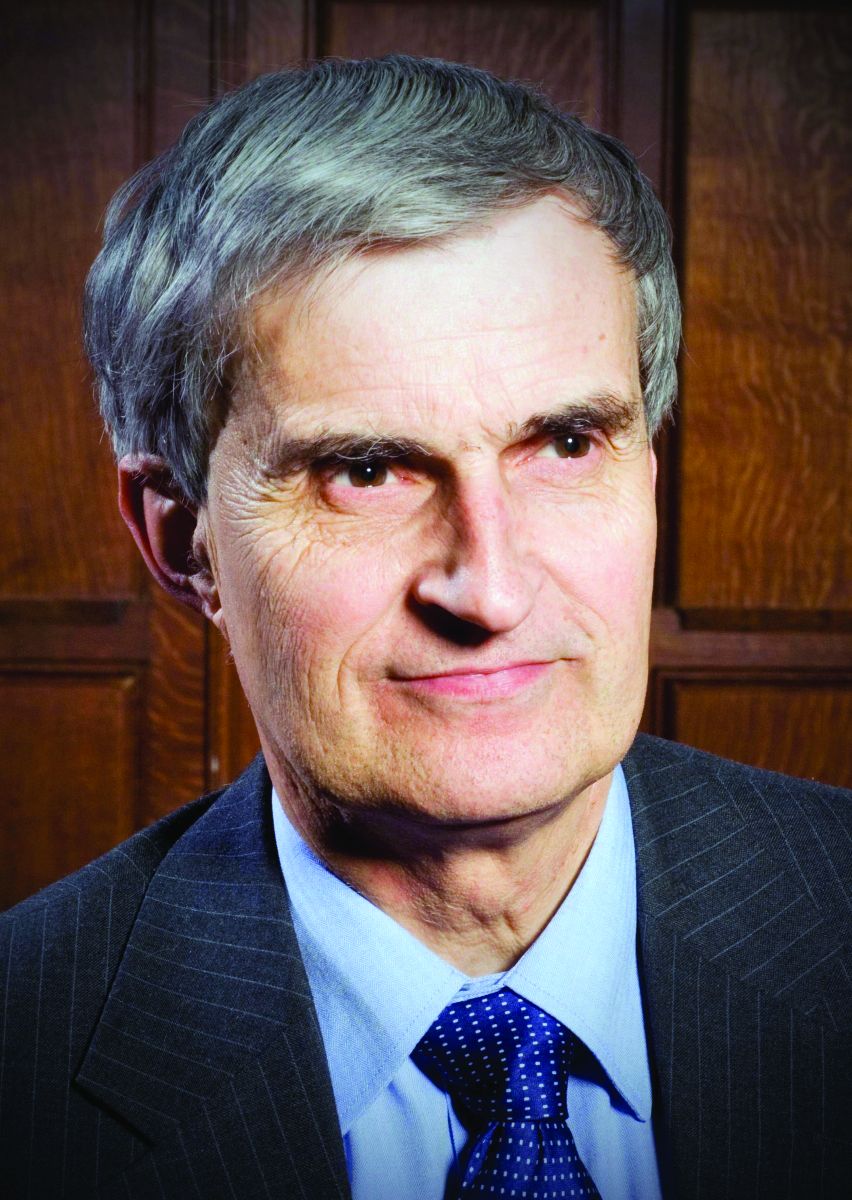

Epiglottitis is edema of the epiglottis, most commonly secondary to bacterial infection. The epidemiology of epiglottitis has changed dramatically since widespread immunization for H. influenza with a significantly decreased incidence and change in the average age of presentation to 14.6 years (previously 5.6 years).7 The clinical course begins with sore throat, dysphonia, refusal to eat and progressive difficulty handling secretions with eventual drooling, stridor, tripoding, and toxic appearance. Epiglottitis can be differentiated from croup and bacterial tracheitis because presentation typically lacks a cough.7,10,11 Diagnosis is made either by direct visualization of the epiglottis or a lateral neck X-ray showing a ‘thumb print’ sign (Figure 2).12 Emergency department treatment is similar to the management of the child with a partial foreign body occlusion and focuses on maintaining the airway and minimizing anything that agitates the patient. Intravenous (IV) antibiotic coverage is similar to bacterial tracheitis (third-generation cephalosporin or a beta-lactamase resistant penicillin).

Retropharyngeal Abscess

The most common chief complaint of retropharyngeal abscess (RPA) is neck pain (38%) with fever. As such, it can clinically be mistaken for meningitis on initial presentation. Retropharyngeal abscess will present rarely with either stridor or associated respiratory distress, and it can also mimic croup on initial presentation. Physical examination findings which differentiate this entity include limited or painful neck extension (45%), torticollis (36.5%), and to a lesser extent limitation of neck flexion (12.5%).13 The median age at diagnosis is 36 months with 75% of patients less than 5 years. Typical presentation is insidious with fever and URI symptoms preceding onset. Diagnosis can be made with a lateral neck X-ray showing widening of the prevertebral space (Figure 3), but the gold standard diagnostic study is a computed tomography with contrast.14 Management is IV antibiotics covering aerobic and anaerobic bacteria (eg, ampicillin-sulbactam) ± surgical intervention.

Caustic Ingestion

Caustic ingestion is most commonly accidental and seen in children aged 12 months to 2 years. However, with recent fads, such as the “Tide Pod challenge” teenagers are also at risk. Airway compromise and stridor are secondary to mucosal injury and edema. Oral injury is not always a useful marker for significant distal injury. A complete evaluation of the upper airway and digestive tract within 48 hours after known/suspected caustic ingestion is recommended to assess full extent of damage.15

Chronic Differentials

Laryngomalacia

Laryngomalacia is a congenital weakness of laryngeal tissues, and it is the most common cause of both chronic stridor and neonatal stridor. It is characterized by progressive worsening of symptoms with crying/feeding and supine positioning. Diagnosis is made by bronchoscopy and management is conservative unless there are life threatening apneic or cyanotic events.7

Rings/Slings

There are many anatomic structures with the potential to cause extrinsic airway compression which present with stridor. This type of stridor is often biphasic. Examples include innominate artery compression, double aortic arch, aberrant subclavian artery, and pulmonary artery sling.7

Stridor presenting in children with a history of prematurity or prolonged intubation should raise concern for subglottic and tracheal stenosis.16

Evaluation

Regardless of the etiology of stridor, efforts should be made to keep the patient calm (ie, allow the parent to keep holding a young child, limit any examination not absolutely necessary). Much of the examination can be completed from a distance without disturbing the child.17 Observation of the inspiratory:expiratory (I:E) ratio can localize the level of airway obstruction. For example, an I:E ratio weighted toward a longer inspiration indicates an extrathoracic airway obstruction. Whereas an I:E with a prolonged expiratory phase is consistent with intrathoracic obstruction (eg, terminal bronchial obstruction).17

Another way to localize the level of obstruction is to look for changes in the voice; patients who present with a change in their voice have a subglottic partial obstruction such as croup. However, patients with a muffled voice or drooling have a supraglottic obstruction such as epiglottitis or RPA.17

Management

Management of stridor focuses on reducing airway obstruction, which is usually secondary to edema in the acute setting.

Viral Laryngotracheitis

Oral steroids are the mainstay of treatment. Research has shown dexamethasone is preferred over prednisolone.18-20 Steroids are not only useful in moderate to severe laryngotracheitis but also have a therapeutic role in children with mild laryngotracheitis.18 In hospital settings the parenteral formulation of dexamethasone can be safely given orally with good effect. There is no therapeutic advantage in acute laryngotracheitis to giving dexamethasone via either the IV or intramuscular route vs oral.21 In the outpatient setting, decadron tablets can be crushed and mixed in with a young child’s favorite soft food (eg, mashed potatoes or apple sauce). The authors recommend this strategy in lieu of prescribing dexamethasone suspension as its dilute concentration (1 mg/10 ml) results in a need for a child to receive a relatively large volume of a distasteful liquid. There is a wide therapeutic range of dexamethasone with studies documenting efficacy for laryngotracheitis in doses ranging from 0.15 mg/kg to 0.6 mg/kg. To date there are no large studies which demonstrate routine therapeutic utility of subsequent doses of dexamethasone. Nebulized budesonide (2.5 mg) can be given if oral steroids are not tolerated, however it is significantly more expensive.

Racemic epinephrine is the agent of choice for rapid onset of action in children who demonstrate stridor at rest. It causes vasoconstriction in the laryngeal mucosa, promotes bronchial smooth muscle relaxation, and thinning of bronchial secretions. It offers short-term relief of symptoms until steroids start to work. There is no rebound effect or worsening of symptoms once the epinephrine wears off, but children who receive this drug should be observed in the ED for a period of time (2-3 hours is standard of care in many hospitals) for return of symptoms.10,22 Patients who are persistently symptomatic 4 hours after administration of steroids or who require repeat doses of racemic epinephrine should be admitted for observation.10There are no contraindications to adjuvant treatments, such as antipyretics and non-sedating analgesics. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for anatomic airway anomalies that may need further evaluation/direct visualization in pediatric patients who present with repeated episodes of croup.10

Case Conclusions

Case 1

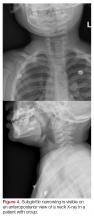

The 9-month-old boy with stridor was noted to have increased stridor while fussy, but even at rest some inspiratory stridor was present. A barky cough was noted in the examination room. The patient was placed on a monitor and a nebulized racemic epinephrine treatment was started. A single dose of oral dexamethasone was given shortly after presentation to the ED. Since the patient had inspiratory stridor at rest with associated tachypnea and hypoxia on initial presentation, a neck X-ray was obtained (Figure 4). Subglottic narrowing was identified on the imaging, but both the epiglottis and the prevertebral space were normal in appearance and no foreign bodies were visualized. The inspiratory stridor at rest, tachypnea, and mild hypoxia all improved after treatment, the patient was observed for 2 hours in the ED without recurrence of respiratory distress and was able to be discharged home with a diagnosis of acute croup.

Case 2

The 3-year-old girl was noted to be in significant positional respiratory distress, so the physician asked her parents to keep her calm in her position of comfort. She was calmly and quickly placed on a monitor with age-appropriate distraction techniques in place and advanced airway equipment at the bedside. A portable chest X-ray was obtained and revealed a coin was partially obstructing the trachea. Care was taken in the ED to avoid all interventions such as IV access that might upset the child so as not to inadvertently convert this partial airway obstruction to a complete obstruction. The otolaryngology team was called urgently, and the patient was transported to the operating room for foreign body removal in a controlled environment.

1. Bjornson CL, Johnson DW. Croup. Lancet. 2008;371(9609):329-339. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60170-1.

2. Escobar ML, Needleman J. Stridor. Pediatr Rev. 2015;36(3):135-137. doi:10.1542/pir.36-3-135.

3. Pfleger A, Eber E. Assessment and causes of stridor. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2016;18:64-72. doi:10.1016/j.prrv.2015.10.003.

4. Boudewyns A, Claes J, Van de Heyning P. Clinical practice: an approach to stridor in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(2):135-141. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-1044-7.

5. Kelley PB, Simon JE. Racemic epinephrine use in croup and disposition. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10(3):181-183.

6. Mandal A, Kabra SK, Lodha R. Upper airway obstruction in children. Indian J Pediatr. 2015;82(8):737-744.

7. Marchese A, Langhan ML. Management of airway obstruction and stridor in pediatric patients. Pediatr Emerg Med Pract. 2017;14(11):1-24.

8. Wani TM, Bissonnette B, Rafiq Malik M, et al. Age-based analysis of pediatric upper airway dimensions using computed tomography imaging. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016;51(3):267-271. doi:10.1002/ppul.23232.

9. Donaldson D, Poleski D, Knipple E, et al. Intramuscular versus oral dexamethasone for the treatment of moderate-to-severe croup: a randomized, double-blind trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(1):16-21.

10. Boudewyns A, Claes J, Van de Heyning P. Clinical practice: an approach to stridor in infants and children. Eur J Pediatr. 2010;169(2):135-141. doi:10.1007/s00431-009-1044-7.

11. Tibballs J, Watson T. Symptoms and signs differentiating croup and epiglottitis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2011;47(3):77-82. doi:10.1111/j.1440-1754.2010.01892.x.

12. Sobol SE, Zapata S. Epiglottitis and croup. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2008;41(3):551-566. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2008.01.012.

13. Craig FW, Schunk JE. Retropharyngeal abscess in children: clinical presentation, utility of imaging, and current management. Pediatrics. 2003;111(6 Pt 1):1394-1398.

14. Roberson DW. Pediatric retropharyngeal abscesses. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2004;5(1):37-40.

15. Riffat F, Cheng A. Pediatric caustic ingestion: 50 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22(1):89-94. doi:10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00867.x.

16. Daniel SJ. The upper airway: congenital malformations. Paediatr Respir Revi. 2006;7 Suppl 1:S260-S263.

17. Arutyunyan H, Spangler M. Pediatric upper airway obstruction. Peds RAP Web site. https://www.hippoed.com/peds/rap/episode/pedsrapfebruary/pediatricupper. Published February 2018. Accessed August 31, 2018.

18. Bjornson CL, Klassen TP, Williamson J, et al; Pediatric Emergency Research Canada Network. A randomized trial of a single dose of oral dexamethasone for mild croup. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1306-1313.

19. Fifoot AA, Ting JY. Comparison between single-dose oral prednisolone and oral dexamethasone in the treatment of croup: a randomized, double-blinded clinical trial. Emerg Med Australas. 2007;19(1):51-58.

20. Sparrow A, Geelhoed G. Prednisolone versus dexamethasone in croup: a randomised equivalence trial. Arch Dis Child. 2005;91(7):580-583.

21. Donaldson D, Poleski D, Knipple E, et al. Intramuscular versus oral dexamethasone for the treatment of moderate-to-severe croup: a randomized, double-blind trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(1):16-21.

22. Kelley PB, Simon JE. Racemic epinephrine use in croup and disposition. Am J Emerg Med. 1992;10(3):181-183.

23. Yamamoto LG. Test your skill in reading pediatric lateral necks. University of Hawaii Web site. https://www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pemxray/v2c20.html. Accessed September 13, 2018.

The distinct features of the pediatric airway make respiratory failure an important concern independent of the underlying cause.

The distinct features of the pediatric airway make respiratory failure an important concern independent of the underlying cause.

Cases

Case 1

It’s a busy shift on an unusually chilly and rainy July night. Emergency medical services (EMS) brings in a 9-month-old boy who woke up with a “squeaking” noise. His parents reported that he has had a fever, cough, rhinorrhea, and difficulty breathing for the past 2 days; however, they did not hear the noisy breathing until the night of presentation. When the patient is examined, it is noted that he has inspiratory stridor at rest, moderate subcostal retractions, and an occasional deep cough. Upper airway transmitted noises were present, but otherwise the patient had clear lungs.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: blood pressure (BP), 85/55 mm Hg; heart rate (HR), 163 beats/min; respiratory rate (RR), 55 breaths/min; and temperature (T), 101.8°F. Oxygen saturation was 90% on room air. The patient’s mother wants to know how the respiratory distress will be fixed and is inquiring if they will have to stay in the hospital overnight.

Case 2

As work begins on the child described above, EMS brings in a 3-year-old girl who appears to be in moderate-severe respiratory distress. Her parents report that she started to drool earlier in the day followed by coughing and occasional gagging. Her parents relay that they thought the symptoms were because of post-nasal drip due to her cold, but the respiratory distress seems to be getting worse, and she now has very noisy breathing and is reluctant to lay down. Upon examination, both inspiratory and expiratory stridor is heard, and it is noted that moderate subcostal retractions are present when the patient is supine.

The patient’s vital signs at presentation were: BP, 89/58 mm Hg; HR, 144 beats/min; RR, 52 breaths/min; and T, 99.5°F. Oxygen saturation was 88% on room air. The nursing staff asked what to do next and why the 2 stridor cases are being managed so differently.

Stridor

Stridor is a high-pitched, harsh sound heard during respiration, predominantly during inspiration, as a result of turbulent air passage.1-3 Stridor is not a diagnosis in itself, but rather a sign of underlying acute or chronic etiology, which needs to be classified based on elicited history and examination.1,4 While the etiology of obstruction may be infectious, congenital, mechanical, or traumatic, the distinct features of the pediatric airway make respiratory failure an important concern independent of the underlying cause.

Anatomy

There are several anatomical differences unique to the pediatric airway that make children, especially infants under 1 year of age, more susceptible to airway obstruction.5,6The pediatric larynx is more anterior and superior and less fibrous than adults, thereby more compliant.6,7 The pediatric epiglottis is longer, omega-shaped, and softer, and the tongue is larger in comparison to the size of the oral cavity, resulting in obstructed airflow.6,7 Children also have a larger and more prominent occiput, causing mechanical obstruction by flexion of the neck when supine.6 While the cricoid cartilage was previously believed to be the narrowest portion of the airway, more recent measurement techniques have challenged this and shown that the glottic and subglottic areas may be narrower in children.7,8