User login

Can Lighting Improve Sleep, Mood, and Behavior in Patients With Dementia?

Nonpharmacologic stimulation of the circadian system may benefit people in long-term care facilities.

BALTIMORE—Among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, a lighting intervention may improve sleep, mood, and agitation, according to a study presented at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The intervention “holds considerable promise as a novel, practically applied, nonpharmacologic intervention” for people with dementia who live in long-term care facilities, said Mariana G. Figueiro, PhD, Director of the Lighting Research Center and Professor of Architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York.

People with dementia often have problems related to sleep and daytime irritability. A study in office workers found that exposure to light that stimulates the circadian system early in the day is associated with better sleep and improved behavior and mood. To assess whether a lighting intervention that delivers a circadian stimulus may improve sleep and behavior in patients with dementia in long-term care facilities, Dr. Figueiro and colleagues conducted a crossover, repeated-measures, within-subjects study. The study included 43 subjects (31 female) with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias and Mini-Mental State Examination scores of less than 24.

The intervention consisted of an LED light table and individual room lights that were placed where patients spent most of their waking hours. The lights were turned on when participants woke up and remained on until 6 PM. Participants wore calibrated light meters that monitored their light exposure.

The trial included four weeks with an active circadian stimulus, four weeks with an inactive lighting intervention, and a four-week washout period in between.

In addition, researchers collected subjective measures of sleep disturbances (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]), mood (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia [CSDD]), and agitation (Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Index [CMAI]) at baseline and during the last week of the active and placebo intervention periods.

The active lighting intervention significantly decreased scores for sleep disturbances, depression, and agitation, compared with placebo. During the active intervention, mean PSQI scores decreased from 10.3 to 6.7, CSDD scores decreased from 10.5 to 7.3, and CMAI scores decreased from 42.9 to 37.4.

A six-month study of the lighting intervention is underway. “A logical next step would be to test the short- and long-term effects of the tailored lighting intervention among those living at home,” Dr. Figueiro and colleagues said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Figueiro MG, Steverson B, Heerwagen J, et al. The impact of daytime light exposures on sleep and mood in office workers. Sleep Health. 2017;3(3):204-215.

Nonpharmacologic stimulation of the circadian system may benefit people in long-term care facilities.

Nonpharmacologic stimulation of the circadian system may benefit people in long-term care facilities.

BALTIMORE—Among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, a lighting intervention may improve sleep, mood, and agitation, according to a study presented at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The intervention “holds considerable promise as a novel, practically applied, nonpharmacologic intervention” for people with dementia who live in long-term care facilities, said Mariana G. Figueiro, PhD, Director of the Lighting Research Center and Professor of Architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York.

People with dementia often have problems related to sleep and daytime irritability. A study in office workers found that exposure to light that stimulates the circadian system early in the day is associated with better sleep and improved behavior and mood. To assess whether a lighting intervention that delivers a circadian stimulus may improve sleep and behavior in patients with dementia in long-term care facilities, Dr. Figueiro and colleagues conducted a crossover, repeated-measures, within-subjects study. The study included 43 subjects (31 female) with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias and Mini-Mental State Examination scores of less than 24.

The intervention consisted of an LED light table and individual room lights that were placed where patients spent most of their waking hours. The lights were turned on when participants woke up and remained on until 6 PM. Participants wore calibrated light meters that monitored their light exposure.

The trial included four weeks with an active circadian stimulus, four weeks with an inactive lighting intervention, and a four-week washout period in between.

In addition, researchers collected subjective measures of sleep disturbances (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]), mood (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia [CSDD]), and agitation (Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Index [CMAI]) at baseline and during the last week of the active and placebo intervention periods.

The active lighting intervention significantly decreased scores for sleep disturbances, depression, and agitation, compared with placebo. During the active intervention, mean PSQI scores decreased from 10.3 to 6.7, CSDD scores decreased from 10.5 to 7.3, and CMAI scores decreased from 42.9 to 37.4.

A six-month study of the lighting intervention is underway. “A logical next step would be to test the short- and long-term effects of the tailored lighting intervention among those living at home,” Dr. Figueiro and colleagues said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Figueiro MG, Steverson B, Heerwagen J, et al. The impact of daytime light exposures on sleep and mood in office workers. Sleep Health. 2017;3(3):204-215.

BALTIMORE—Among patients with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, a lighting intervention may improve sleep, mood, and agitation, according to a study presented at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The intervention “holds considerable promise as a novel, practically applied, nonpharmacologic intervention” for people with dementia who live in long-term care facilities, said Mariana G. Figueiro, PhD, Director of the Lighting Research Center and Professor of Architecture at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, New York.

People with dementia often have problems related to sleep and daytime irritability. A study in office workers found that exposure to light that stimulates the circadian system early in the day is associated with better sleep and improved behavior and mood. To assess whether a lighting intervention that delivers a circadian stimulus may improve sleep and behavior in patients with dementia in long-term care facilities, Dr. Figueiro and colleagues conducted a crossover, repeated-measures, within-subjects study. The study included 43 subjects (31 female) with Alzheimer’s disease or related dementias and Mini-Mental State Examination scores of less than 24.

The intervention consisted of an LED light table and individual room lights that were placed where patients spent most of their waking hours. The lights were turned on when participants woke up and remained on until 6 PM. Participants wore calibrated light meters that monitored their light exposure.

The trial included four weeks with an active circadian stimulus, four weeks with an inactive lighting intervention, and a four-week washout period in between.

In addition, researchers collected subjective measures of sleep disturbances (Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index [PSQI]), mood (Cornell Scale for Depression in Dementia [CSDD]), and agitation (Cohen-Mansfield Agitation Index [CMAI]) at baseline and during the last week of the active and placebo intervention periods.

The active lighting intervention significantly decreased scores for sleep disturbances, depression, and agitation, compared with placebo. During the active intervention, mean PSQI scores decreased from 10.3 to 6.7, CSDD scores decreased from 10.5 to 7.3, and CMAI scores decreased from 42.9 to 37.4.

A six-month study of the lighting intervention is underway. “A logical next step would be to test the short- and long-term effects of the tailored lighting intervention among those living at home,” Dr. Figueiro and colleagues said.

—Jake Remaly

Suggested Reading

Figueiro MG, Steverson B, Heerwagen J, et al. The impact of daytime light exposures on sleep and mood in office workers. Sleep Health. 2017;3(3):204-215.

Huntington’s Disease Symptoms Vary by Age of Onset

Earlier age of onset may be associated with higher severity of behavioral symptoms.

MIAMI—The greater the age of Huntington’s disease onset, the lower the likelihood that the patient’s major symptom type at disease presentation will be behavioral or cognitive, according to research presented at the Second Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress. Increasing age at onset also is associated with a higher likelihood that motor symptoms will be the major symptom type at disease presentation.

Examining Enroll-HD Data

A patient may have subtle changes in movement, thinking, or behavior as early as 20 years before the onset of Huntington’s disease. Allison Daley, a clinical research specialist at Ohio State University in Columbus, and colleagues noted anecdotally that the severity of behavioral symptoms was decreased in older patients with newly diagnosed Huntington’s disease, compared with younger patients. The group set out to investigate the relationship between behavioral symptoms and age at onset of clinical symptoms in Huntington’s disease.

Ms. Daley and colleagues examined data for 8,714 participants registered in the Enroll-HD database as of 2016. They established three categories of patients based on age of onset. Early-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset at an age younger than 30. Earlier adult-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset between ages 30 and 59. Later adult-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset at an age above 59. Ms. Daley’s group examined the frequency and severity of behavioral symptoms at disease presentation in all three groups. They used the Clinical Characteristics form and the Problem Behaviors Assessment form to evaluate symptom presence and severity.

Motor Symptoms More Common in Late-Onset Disease

Of the entire sample, 4,469 participants had manifest Huntington’s disease. Motor symptoms were present in 42% of participants with early-onset Huntington’s disease, 50% of participants with earlier adult-onset Huntington’s disease, and 67% of participants with later adult-onset Huntington’s disease. Cognitive symptoms were recorded in 9% of the early-onset group, 10% of the earlier adult-onset group, and 4% of the later adult-onset group. Behavioral symptoms were observed in 26% of the early-onset group, 19% of the earlier adult-onset group, and 11% of the later adult-onset group.

A one-year increase in age at onset was associated with a 5.5% decrease in the odds of severe behavioral symptom of any type. In addition, a one-year increase in age at onset was associated with a 9.4% decrease in the odds of severe disorientation, an 8.8% decrease in the odds of severe delusions, a 6.8% decrease in the odds of severe obsessive–compulsive behavior, and a 5.8% decrease in the odds of severe apathy.

At baseline, 56% of participants had apathy, 55% had anxiety, 54% had irritability, 51% had depression, 44% had perseverative thinking, and 29% had anger or aggression.

“Specific behavioral symptoms, particularly disorientation, delusions, and obsessive–compulsive behaviors, may tend to manifest more severely in individuals with earlier age at onset. Earlier age at onset may be associated with higher severity of behavioral symptoms overall,” said Ms. Daley. “Further research exploring biologic mechanisms and environmental factors that interact with CAG repeat size to affect symptom presentation in Huntington’s disease at different ages at onset may help identify additional therapeutic strategies and individualized treatment approaches for Huntington’s disease.”

—Erik Greb

Earlier age of onset may be associated with higher severity of behavioral symptoms.

Earlier age of onset may be associated with higher severity of behavioral symptoms.

MIAMI—The greater the age of Huntington’s disease onset, the lower the likelihood that the patient’s major symptom type at disease presentation will be behavioral or cognitive, according to research presented at the Second Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress. Increasing age at onset also is associated with a higher likelihood that motor symptoms will be the major symptom type at disease presentation.

Examining Enroll-HD Data

A patient may have subtle changes in movement, thinking, or behavior as early as 20 years before the onset of Huntington’s disease. Allison Daley, a clinical research specialist at Ohio State University in Columbus, and colleagues noted anecdotally that the severity of behavioral symptoms was decreased in older patients with newly diagnosed Huntington’s disease, compared with younger patients. The group set out to investigate the relationship between behavioral symptoms and age at onset of clinical symptoms in Huntington’s disease.

Ms. Daley and colleagues examined data for 8,714 participants registered in the Enroll-HD database as of 2016. They established three categories of patients based on age of onset. Early-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset at an age younger than 30. Earlier adult-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset between ages 30 and 59. Later adult-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset at an age above 59. Ms. Daley’s group examined the frequency and severity of behavioral symptoms at disease presentation in all three groups. They used the Clinical Characteristics form and the Problem Behaviors Assessment form to evaluate symptom presence and severity.

Motor Symptoms More Common in Late-Onset Disease

Of the entire sample, 4,469 participants had manifest Huntington’s disease. Motor symptoms were present in 42% of participants with early-onset Huntington’s disease, 50% of participants with earlier adult-onset Huntington’s disease, and 67% of participants with later adult-onset Huntington’s disease. Cognitive symptoms were recorded in 9% of the early-onset group, 10% of the earlier adult-onset group, and 4% of the later adult-onset group. Behavioral symptoms were observed in 26% of the early-onset group, 19% of the earlier adult-onset group, and 11% of the later adult-onset group.

A one-year increase in age at onset was associated with a 5.5% decrease in the odds of severe behavioral symptom of any type. In addition, a one-year increase in age at onset was associated with a 9.4% decrease in the odds of severe disorientation, an 8.8% decrease in the odds of severe delusions, a 6.8% decrease in the odds of severe obsessive–compulsive behavior, and a 5.8% decrease in the odds of severe apathy.

At baseline, 56% of participants had apathy, 55% had anxiety, 54% had irritability, 51% had depression, 44% had perseverative thinking, and 29% had anger or aggression.

“Specific behavioral symptoms, particularly disorientation, delusions, and obsessive–compulsive behaviors, may tend to manifest more severely in individuals with earlier age at onset. Earlier age at onset may be associated with higher severity of behavioral symptoms overall,” said Ms. Daley. “Further research exploring biologic mechanisms and environmental factors that interact with CAG repeat size to affect symptom presentation in Huntington’s disease at different ages at onset may help identify additional therapeutic strategies and individualized treatment approaches for Huntington’s disease.”

—Erik Greb

MIAMI—The greater the age of Huntington’s disease onset, the lower the likelihood that the patient’s major symptom type at disease presentation will be behavioral or cognitive, according to research presented at the Second Pan American Parkinson’s Disease and Movement Disorders Congress. Increasing age at onset also is associated with a higher likelihood that motor symptoms will be the major symptom type at disease presentation.

Examining Enroll-HD Data

A patient may have subtle changes in movement, thinking, or behavior as early as 20 years before the onset of Huntington’s disease. Allison Daley, a clinical research specialist at Ohio State University in Columbus, and colleagues noted anecdotally that the severity of behavioral symptoms was decreased in older patients with newly diagnosed Huntington’s disease, compared with younger patients. The group set out to investigate the relationship between behavioral symptoms and age at onset of clinical symptoms in Huntington’s disease.

Ms. Daley and colleagues examined data for 8,714 participants registered in the Enroll-HD database as of 2016. They established three categories of patients based on age of onset. Early-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset at an age younger than 30. Earlier adult-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset between ages 30 and 59. Later adult-onset Huntington’s disease was defined as onset at an age above 59. Ms. Daley’s group examined the frequency and severity of behavioral symptoms at disease presentation in all three groups. They used the Clinical Characteristics form and the Problem Behaviors Assessment form to evaluate symptom presence and severity.

Motor Symptoms More Common in Late-Onset Disease

Of the entire sample, 4,469 participants had manifest Huntington’s disease. Motor symptoms were present in 42% of participants with early-onset Huntington’s disease, 50% of participants with earlier adult-onset Huntington’s disease, and 67% of participants with later adult-onset Huntington’s disease. Cognitive symptoms were recorded in 9% of the early-onset group, 10% of the earlier adult-onset group, and 4% of the later adult-onset group. Behavioral symptoms were observed in 26% of the early-onset group, 19% of the earlier adult-onset group, and 11% of the later adult-onset group.

A one-year increase in age at onset was associated with a 5.5% decrease in the odds of severe behavioral symptom of any type. In addition, a one-year increase in age at onset was associated with a 9.4% decrease in the odds of severe disorientation, an 8.8% decrease in the odds of severe delusions, a 6.8% decrease in the odds of severe obsessive–compulsive behavior, and a 5.8% decrease in the odds of severe apathy.

At baseline, 56% of participants had apathy, 55% had anxiety, 54% had irritability, 51% had depression, 44% had perseverative thinking, and 29% had anger or aggression.

“Specific behavioral symptoms, particularly disorientation, delusions, and obsessive–compulsive behaviors, may tend to manifest more severely in individuals with earlier age at onset. Earlier age at onset may be associated with higher severity of behavioral symptoms overall,” said Ms. Daley. “Further research exploring biologic mechanisms and environmental factors that interact with CAG repeat size to affect symptom presentation in Huntington’s disease at different ages at onset may help identify additional therapeutic strategies and individualized treatment approaches for Huntington’s disease.”

—Erik Greb

Tetrad Bodies in Skin

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

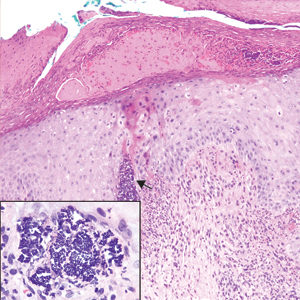

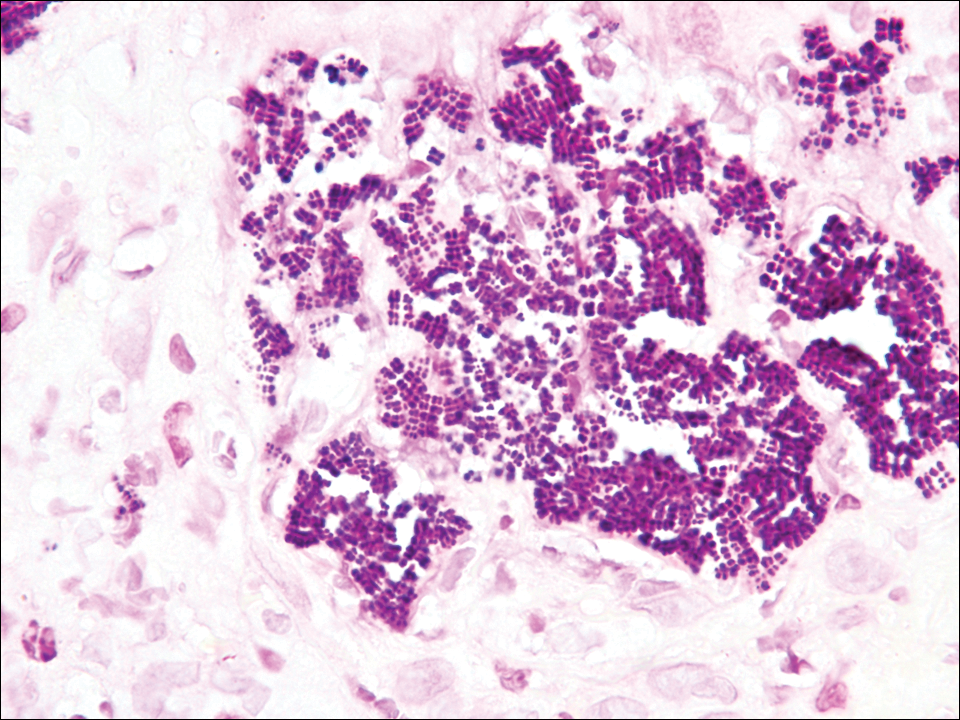

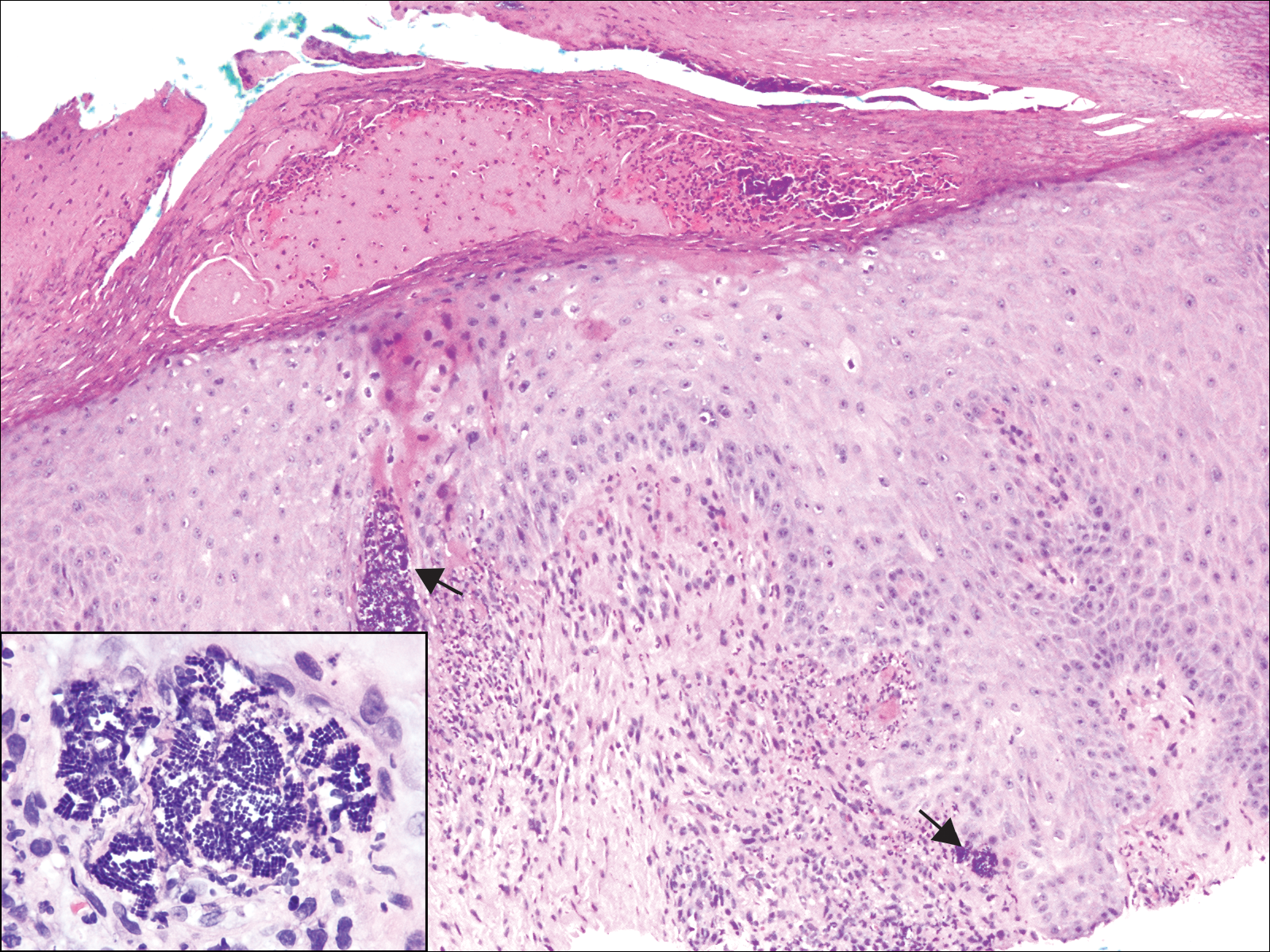

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

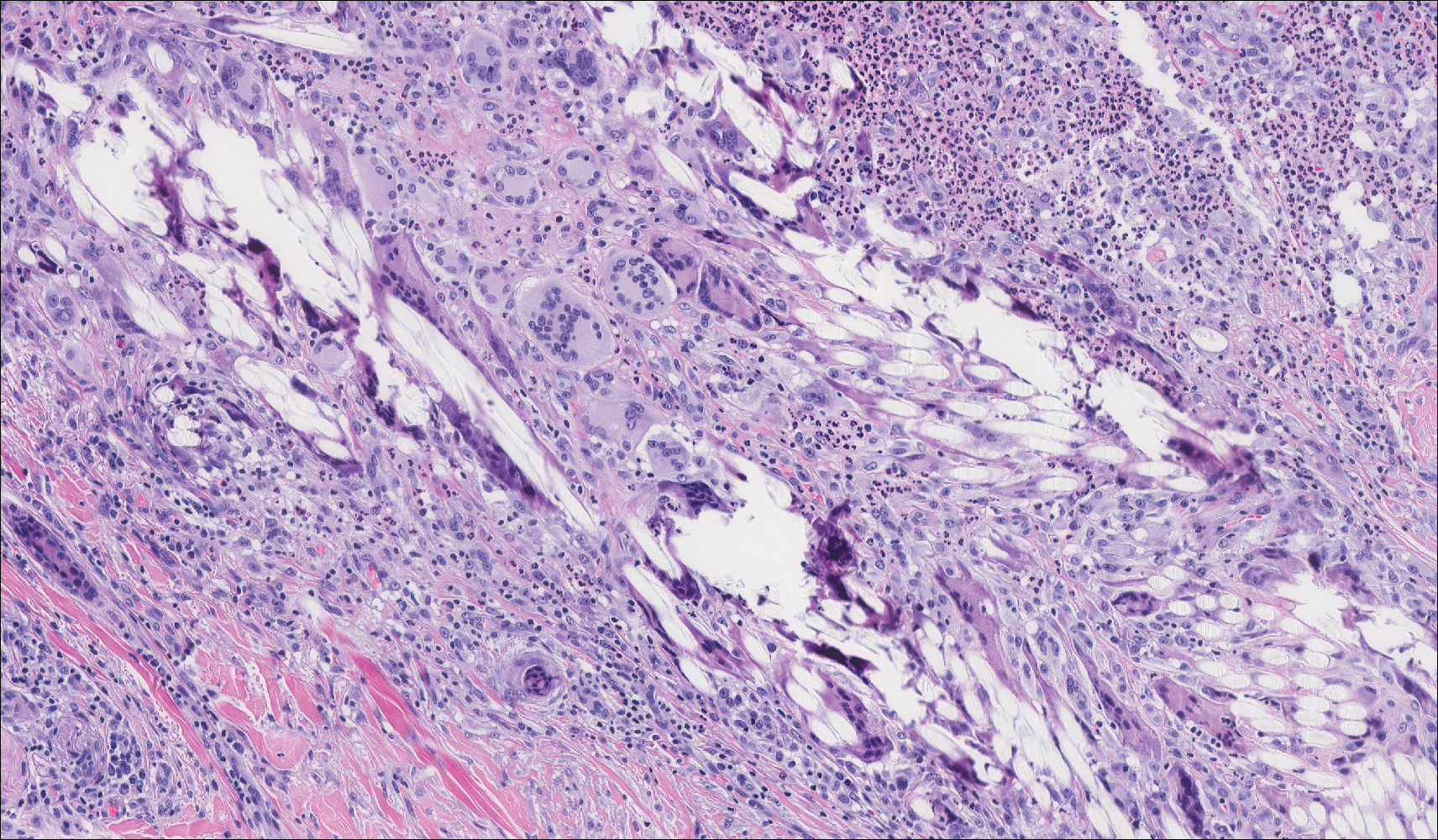

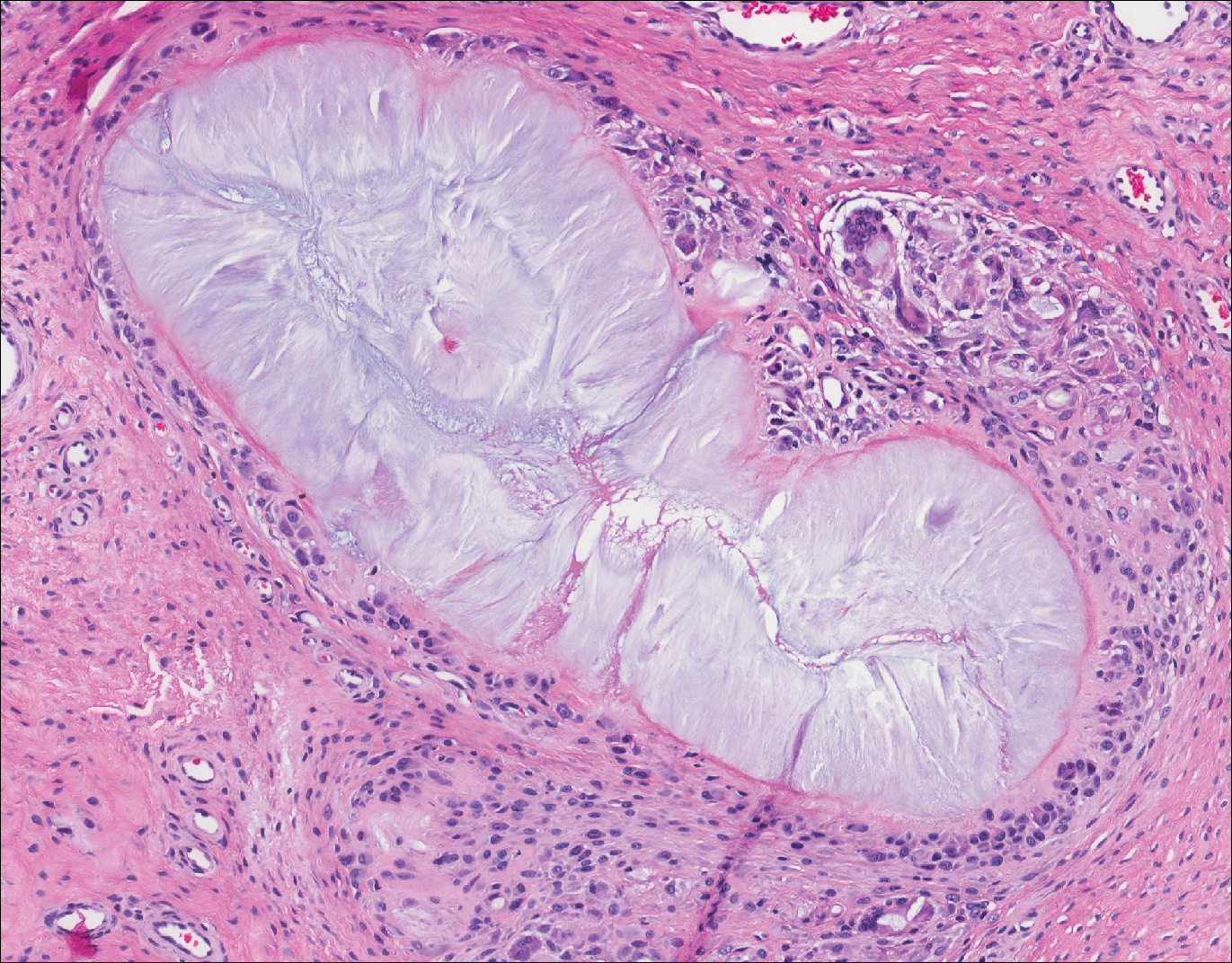

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

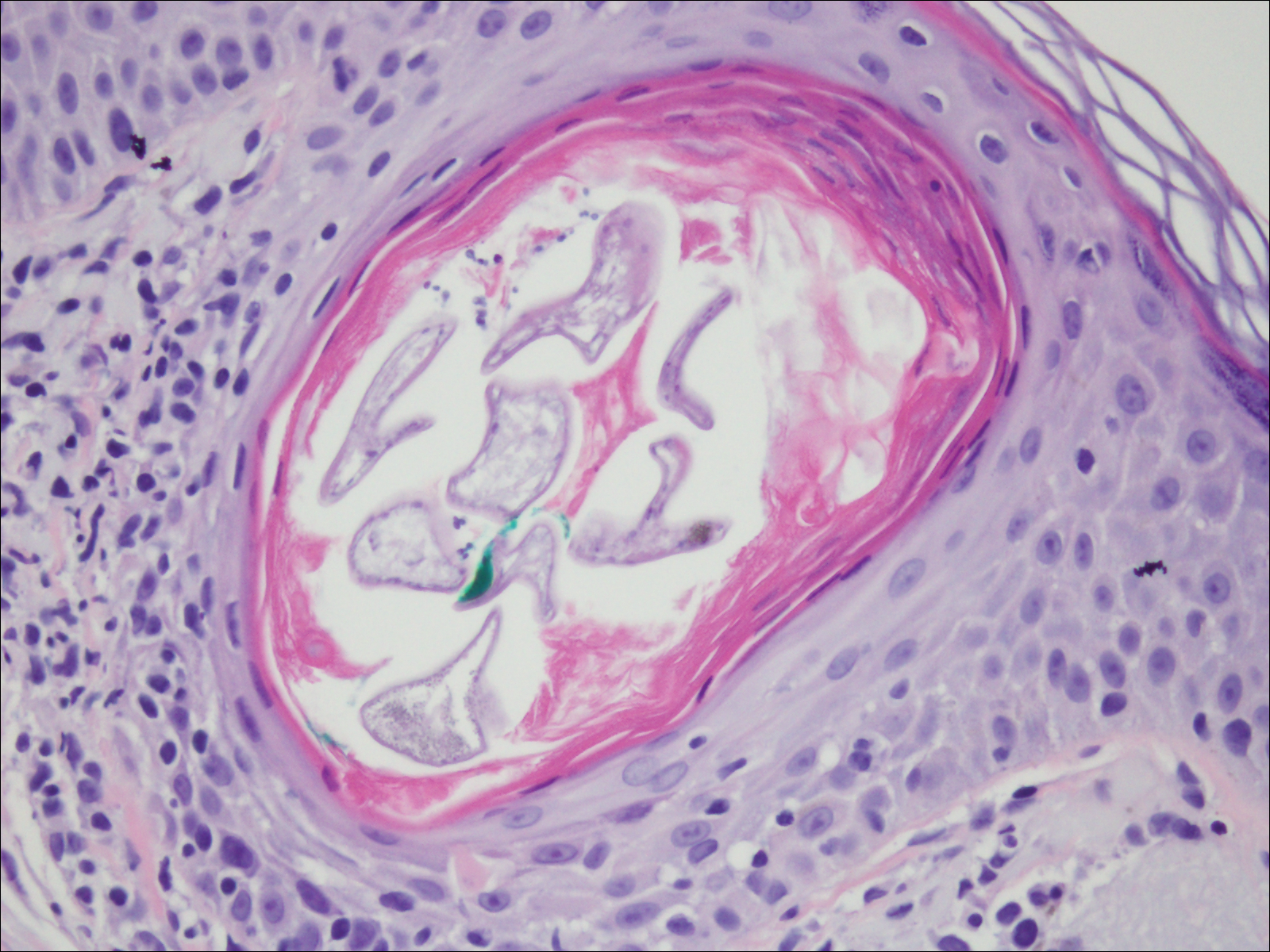

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

The Diagnosis: Bacterial Infection

The tetrad arrangement of organisms seen in this case was classic for Micrococcus and Sarcina species. Both are gram-positive cocci that occur in tetrads, but Micrococcus is aerobic and catalase positive, whereas Sarcina species are anaerobic, catalase negative, acidophilic, and form spores in alkaline pH.1 Although difficult to definitively differentiate on light microscopy, micrococci are smaller in size, ranging from 0.5 to 2.0 μm, and occur in tight clusters, as seen in this case (quiz images), in contrast to Sarcina species, which are relatively larger (1.8-3.0 μm).2 Sarcinae typically are found in soil and air, are considered pathogenic, and are associated with gastric symptoms (Sarcina ventriculi).1Sarcina species also are reported to colonize the skin of patients with diabetes mellitus, but no pathogenic activity is known in the skin.3Micrococcus species, with the majority being Micrococcus luteus, are part of the normal flora of the human skin as well as the oral and nasal cavities. Occasional reports of pneumonia, endocarditis, meningitis, arthritis, endophthalmitis, and sepsis have been reported in immunocompromised individuals.4 In the skin, Micrococcus is a commensal organism; however, Micrococcus sedentarius has been associated with pitted keratolysis, and reports of Micrococcus folliculitis in human immunodeficiency virus patients also are described in the literature.5,6 Micrococci are considered opportunistic bacteria and may worsen and prolong a localized cutaneous infection caused by other organisms under favorable conditions.7Micrococcus luteus is one of the most common bacteria cultured from skin and soft tissue infections caused by fungal organisms.8 Depending on the immune status of an individual, use of broad-spectrum antibiotic and/or elimination of favorable milieu (ie, primary pathogen, breaks in skin) usually treats the infection.

Because of the rarity of infections caused and being part of the normal flora, the clinical implications of subtyping and sensitivity studies via culture or molecular studies may not be important; however, incidental presence of these organisms with unfamiliar morphology may cause confusion for the dermatopathologist. An extremely small size (0.5-2.0 μm) compared to red blood cells (7-8 μm) and white blood cells (10-12 μm) in a tight tetrad arrangement should raise the suspicion for Micrococcus.1 The refractive nature of these organisms from a thick extracellular layer can mimic fungus or plant matter; a negative Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain in this case helped in not only differentiating but also ruling out secondary fungal infection. Finally, a Gram stain with violet staining of these organisms reaffirmed the diagnosis of gram-positive bacterial organisms, most consistent with Micrococcus species (Figure 1). Culture studies were not performed because of contamination of the tissue specimen and resolution of the patient's symptoms.

The presence of foreign material in the skin may be traumatic, occupational, cosmetic, iatrogenic, or self-inflicted, including a wide variety of substances that appear in different morphological forms on hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained sections, depending on their structure and physiochemical properties.9 Although not all foreign bodies may polarize, examining the sample under polarized light is considered an important step to narrow down the differential diagnosis. The tissue reaction is primarily dependent on the nature of the substance and duration, consisting of histiocytes, macrophages, plasma cells, lymphocytes, and fibrosis.9 Activated histiocytes, multinucleated giant cells, and granulomas are classic findings that generally are seen surrounding and engulfing the foreign material (Figure 2). In addition to foreign material, substances such as calcium salts, urate crystals, extruded keratin, ruptured cysts, and hair follicles may act as foreign materials and can incite a tissue response.9 Absence of histiocytic response, granuloma formation, and fibrosis in a lesion of 1 month's duration made the tetrad bodies unlikely to be foreign material.

Demodex mites are superficial inhabitants of human skin that are acquired shortly after birth, live in or near pilosebaceous units, and obtain nourishment from skin cells and sebum.10,11 The mites can be recovered on 10% of skin biopsies, most commonly on the face due to high sebum production.10 Adult mites range from 0.1 to 0.4 mm in length and are round to oval in shape. Females lay eggs inside the hair follicle or sebaceous glands.11 They usually are asymptomatic, but their infestation may become pathogenic, especially in immunocompromised individuals.10 The clinical picture may resemble bacterial folliculitis, rosacea, and perioral dermatitis, while histology typically is characterized by spongiosis, lymphohistiocytic inflammation around infested follicles, and mite(s) in follicular infundibula (Figure 3). Sometimes the protrusion of mites and keratin from the follicles is seen as follicular spines on histology and referred to as pityriasis folliculorum.

Deposits of urate crystals in skin occur from the elevated serum uric acid levels in gout. The cutaneous deposits are mainly in the dermis and subcutaneous tissue and are extremely painful.12 Urate crystals get dissolved during formalin fixation and leave needlelike clefts in a homogenous, lightly basophilic material on H&E slide (Figure 4). For the same reason, polarized microscopy also is not helpful despite the birefringent nature of urate crystals.12

Fungal yeast forms appear round to oval under light microscopy, ranging from 2 to 100 μm in size.13 The common superficial forms involving the epidermis or hair follicles similar to the current case of bacterial infection include Malassezia and dermatophyte infections. Malassezia is part of the normal flora of sebum-rich areas of skin and is associated with superficial infections such as folliculitis, atopic dermatitis, psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, and dandruff.14Malassezia appear as clusters of yeast cells that are pleomorphic and round to oval in shape, ranging from 2 to 6 μm in size. It forms hyphae in its pathogenic form and gives rise to the classic spaghetti and meatball-like appearance that can be highlighted by periodic acid-Schiff (Figure 5) and Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver special stains. Dermatophytes include 3 genera--Trichophyton, Microsporum, and Epidermophyton--with at least 40 species that causes skin infections in humans.14 Fungal spores and hyphae forms are restricted to the stratum corneum. The hyphae forms may not be apparent on H&E stain, and periodic acid-Schiff staining is helpful in visualizing the fungal elements. The presence of neutrophils in the corneal layer, basket weave hyperkeratosis, and presence of fungal hyphae within the corneal layer fissures (sandwich sign) are clues to the dermatophyte infection.15 Other smaller fungi such as Histoplasma capsulatum (2-4 μm), Candida (3-5 μm), and Pneumocystis (2-5 μm) species can be found in skin in disseminated infections, usually affecting immunocompromised individuals.13Histoplasma is a basophilic yeast that exhibits narrow-based budding and appears clustered within or outside of macrophages. Candida species generally are dimorphic, and yeasts are found intermingled with filamentous forms. Pneumocystis infection in skin is extremely rare, and the fungi appear as spherical or crescent-shaped bodies in a foamy amorphous material.16

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

- Al Rasheed MR, Senseng CG. Sarcina ventriculi: review of the literature. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140:1441-1445.

- Lam-Himlin D, Tsiatis AC, Montgomery E, et al. Sarcina organisms in the gastrointestinal tract: a clinicopathologic and molecular study. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35:1700-1705.

- Somerville DA, Lancaster-Smith M. The aerobic cutaneous microflora of diabetic subjects. Br J Dermatol. 1973;89:395-400.

- Hetem DJ, Rooijakkers S, Ekkelenkamp MB. Staphylococci and Micrococci. In: Cohen J, Powderly WG, Opal SM, eds. Infectious Diseases. 4th ed. Vol 2. New York, NY: Elsevier; 2017:1509-1522.

- Nordstrom KM, McGinley KJ, Cappiello L, et al. Pitted keratolysis. the role of Micrococcus sedentarius. Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:1320-1325.

- Smith KJ, Neafie R, Yeager J, et al. Micrococcus folliculitis in HIV-1 disease. Br J Dermatol. 1999;141:558-561.

- van Rensburg JJ, Lin H, Gao X, et al. The human skin microbiome associates with the outcome of and is influenced by bacterial infection. mBio. 2015;6:E01315-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01315-15.

- Chuku A, Nwankiti OO. Association of bacteria with fungal infection of skin and soft tissue lesions in plateau state, Nigeria. Br Microbiol Res J. 2013;3:470-477.

- Molina-Ruiz AM, Requena L. Foreign body granulomas. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:497-523.

- Elston CA, Elston DM. Demodex mites. Clin Dermatol. 2014;32:739-743.

- Rather PA, Hassan I. Human Demodex mite: the versatile mite of dermatological importance. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59:60-66.

- Gaviria JL, Ortega VG, Gaona J, et al. Unusual dermatological manifestations of gout: review of literature and a case report. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2015;3:E445.

- Guarner J, Brandt ME. Histopathologic diagnosis of fungal infections in the 21st century. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2011;24:247-280.

- White TC, Findley K, Dawson TL Jr, et al. Fungi on the skin: dermatophytes and Malassezia. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4. pii:a019802. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019802.

- Gottlieb GJ, Ackerman AB. The "sandwich sign" of dermatophytosis. Am J Dermatopathol. 1986;8:347.

- Hennessey NP, Parro EL, Cockerell CJ. Cutaneous Pneumocystis carinii infection in patients with acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Arch Dermatol. 1991;127:1699-1701.

A 72-year-old woman with a medical history notable for multiple sclerosis and intravenous drug abuse presented to the dermatology clinic with a 0.6×0.5-cm, pruritic, wartlike, inflamed, keratotic papule on the palmar aspect of the right finger of more than 1 month's duration. A shave biopsy was performed that showed excoriation with serum crust, parakeratosis, and neutrophilic infiltrate in the papillary dermis. Within the serum crust and at the dermoepidermal junction, clusters of refractive basophilic bodies (arrows) in tetrad arrangement also were noted (inset). The papule resolved after the biopsy without any additional treatment.

Researchers Investigate Nontraditional Methods of Providing CBT-I

Studies compare telehealth with in-person treatment and examine two Internet-based methods of delivering CBT-I.

BALTIMORE—Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is an effective treatment, but a scarcity of trained clinicians has limited patients’ access to it. Telehealth and Internet-based platforms could broaden access to CBT-I, and investigators presented research on the efficacy of these methods of administration at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

CBT-I by Telehealth Is Noninferior to In-Person CBT-I

Philip Gehrman, PhD, Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia VA Medical Center, and colleagues conducted a cluster-randomized trial to determine whether group CBT-I delivered by telehealth was noninferior to CBT-I delivered in person. Eligible participants were veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score of 15 or higher. The investigators randomized 95 participants in groups of six to eight to group CBT-I in person or by telehealth. The primary outcome was the change in ISI score from baseline to the three-month follow-up. Dr. Gehrman and colleagues defined treatment inferiority as a difference of greater than two points on the ISI score.

Participants’ mean age was 55.6, about 91% of the sample was male, and 42.2% of the sample was African American. The study population generally was overweight and had severe PTSD. Approximately half of the population was receiving one or more psychotropic medication. Forty-six participants were randomized to in-person CBT-I, and 49 were randomized to CBT-I delivered by telehealth.

At three months, the mean change in ISI score was 6.48 for in-person CBT-I and 4.45 for telehealth CBT-I. The difference between groups was outside of the prespecified margin of inferiority, and the researchers concluded that CBT-I delivered by telehealth was noninferior to in-person CBT-I.

The overall effectiveness of both methods of administration was modest, said Dr. Gehrman. The effect size might be greater in a group with fewer comorbidities or in a group that received more treatment sessions, he added. Nevertheless, the results “demonstrate that CBT-I can be effective even in a complex patient population,” he concluded.

SHUTi May Be Inferior to In-Person CBT-I

The online CBT-I intervention Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi) has reduced insomnia with effect sizes similar to those of traditional CBT-I. No researchers had compared the two techniques directly, however. Håvard Kallestad, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Saint Olav’s Hospital in Trondheim, Norway, and colleagues examined whether SHUTi was a noninferior treatment for insomnia, compared with in-person CBT-I.

Eligible participants were 18 or older, had a diagnosis of insomnia, had been referred to a sleep clinic, and had access to a computer and adequate computer skills. Participants were randomized to in-person CBT-I or SHUTi. The primary outcome was ISI score, and three therapists assessed participants’ outcomes at baseline, after treatment, and at six months. They defined noninferiority as a difference between treatments of 2 or fewer points on ISI score.

Dr. Kallestad and colleagues randomized 52 participants to in-person CBT-I and 49 to SHUTi. Mean duration of insomnia was about 13 years. Approximately 60% of participants were currently using sleep medication, and about 90% had had previous treatment with sleep medication. After treatment, two patients in the in-person group and five in the SHUTi group were lost to follow-up. At six months, four participants in the in-person group and eight in the SHUTi group were lost to follow-up.

Both study arms had significantly lower ISI scores after treatment and at six months. After treatment, the mean ISI score in the in-person group was 5.1 points lower than in the SHUTi group, indicating that SHUTi was inferior at that time. At six months, mean ISI score was 3.3 points lower in the in-person group than in the SHUTi group. Because part of the confidence interval overlapped with the noninferiority margin, the result was inconclusive.

After treatment, the response rate was 70% in the in-person group and 43% in the SHUTi group. The remission rate was 52% in the in-person group and 18% in the SHUTi group. At six months, the response rate was 65% for the in-person group and 46% for the SHUTi group. The remission rate was 56% in the in-person group and 24% in the SHUTi group.

“SHUTi did not have the same effectiveness in this patient sample, compared with previous studies,” said Dr. Kallestad. One reason could be that previous studies included self-selected participants, rather than patients who had been referred to a sleep clinic. Also, the researchers interviewed all participants at baseline, and SHUTi might have seemed “more limited” in comparison with the interview, Dr. Kallestad concluded.

Digital CBT-I May Prevent Incident Depression

Insomnia is a modifiable risk factor for depression, and research has indicated that CBT-I reduces the severity of depression. Investigators also have shown that digitally delivered CBT-I effectively reduces insomnia and depression. Phillip C. Cheng, PhD, a researcher at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, and colleagues sought to determine whether digitally delivered CBT-I could prevent incident depression.

The researchers randomized 658 people with insomnia to Sleepio, an Internet-based CBT-I treatment, or to a control condition of online sleep education. The study’s primary outcome was the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), and Dr. Cheng’s group defined depression as a score greater than 10 on the QIDS. The researchers also examined participants’ ISI scores and functional outcomes such as work productivity, social functioning, cognitive functioning, and resilience. Assessments were performed at baseline, after treatment, and at one year.

In all, 358 participants were randomized to Sleepio, and 300 were randomized to sleep education. The patient population was predominantly female, was racially diverse, and had a diversity of educational attainment. The demographics of the study arms did not differ significantly.

After treatment, the rate of incident depression was 11% in the sleep education group and 6.5% in the Sleepio group. The difference between arms was not statistically significant. At one year, the rate of incident depression was 22% in the sleep education group and 5.1% in the Sleepio group. The difference between arms at one year was statistically significant, as was the change in depression incidence over time in the sleep education group.

Among patients who did not develop depression, ISI score decreased to a value below the cutoff for insomnia, regardless of study arm. ISI score did not change significantly among participants who developed depression, however. Work productivity, social functioning, cognitive functioning, and resilience improved more in the Sleepio group than in the sleep education group.

The results indicate that “digitally delivered CBT-I may prevent incident depression in adults with insomnia,” said Dr. Cheng. Each episode of depression increases the risk of relapse of depression, which underscores the significance of preventing incident depression, he added. Digital CBT-I also appears to reduce the economic burden associated with depression, and further studies could clarify whether it improves resilience, Dr. Cheng concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Espie CA, Kyle SD, Williams C, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep. 2012;35(6):769-781.

Gehrman P, Shah MT, Miles A, et al. Feasibility of group cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia delivered by clinical video telehealth. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1041-1046.

Hagatun S, Vedaa Ø, Nordgreen T, et al. The short-term efficacy of an unguided internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial with a six-month nonrandomized follow-up. Behav Sleep Med. 2017 Mar 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Ye YY, Chen NK, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e010707.

Studies compare telehealth with in-person treatment and examine two Internet-based methods of delivering CBT-I.

Studies compare telehealth with in-person treatment and examine two Internet-based methods of delivering CBT-I.

BALTIMORE—Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is an effective treatment, but a scarcity of trained clinicians has limited patients’ access to it. Telehealth and Internet-based platforms could broaden access to CBT-I, and investigators presented research on the efficacy of these methods of administration at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

CBT-I by Telehealth Is Noninferior to In-Person CBT-I

Philip Gehrman, PhD, Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia VA Medical Center, and colleagues conducted a cluster-randomized trial to determine whether group CBT-I delivered by telehealth was noninferior to CBT-I delivered in person. Eligible participants were veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score of 15 or higher. The investigators randomized 95 participants in groups of six to eight to group CBT-I in person or by telehealth. The primary outcome was the change in ISI score from baseline to the three-month follow-up. Dr. Gehrman and colleagues defined treatment inferiority as a difference of greater than two points on the ISI score.

Participants’ mean age was 55.6, about 91% of the sample was male, and 42.2% of the sample was African American. The study population generally was overweight and had severe PTSD. Approximately half of the population was receiving one or more psychotropic medication. Forty-six participants were randomized to in-person CBT-I, and 49 were randomized to CBT-I delivered by telehealth.

At three months, the mean change in ISI score was 6.48 for in-person CBT-I and 4.45 for telehealth CBT-I. The difference between groups was outside of the prespecified margin of inferiority, and the researchers concluded that CBT-I delivered by telehealth was noninferior to in-person CBT-I.

The overall effectiveness of both methods of administration was modest, said Dr. Gehrman. The effect size might be greater in a group with fewer comorbidities or in a group that received more treatment sessions, he added. Nevertheless, the results “demonstrate that CBT-I can be effective even in a complex patient population,” he concluded.

SHUTi May Be Inferior to In-Person CBT-I

The online CBT-I intervention Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi) has reduced insomnia with effect sizes similar to those of traditional CBT-I. No researchers had compared the two techniques directly, however. Håvard Kallestad, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Saint Olav’s Hospital in Trondheim, Norway, and colleagues examined whether SHUTi was a noninferior treatment for insomnia, compared with in-person CBT-I.

Eligible participants were 18 or older, had a diagnosis of insomnia, had been referred to a sleep clinic, and had access to a computer and adequate computer skills. Participants were randomized to in-person CBT-I or SHUTi. The primary outcome was ISI score, and three therapists assessed participants’ outcomes at baseline, after treatment, and at six months. They defined noninferiority as a difference between treatments of 2 or fewer points on ISI score.

Dr. Kallestad and colleagues randomized 52 participants to in-person CBT-I and 49 to SHUTi. Mean duration of insomnia was about 13 years. Approximately 60% of participants were currently using sleep medication, and about 90% had had previous treatment with sleep medication. After treatment, two patients in the in-person group and five in the SHUTi group were lost to follow-up. At six months, four participants in the in-person group and eight in the SHUTi group were lost to follow-up.

Both study arms had significantly lower ISI scores after treatment and at six months. After treatment, the mean ISI score in the in-person group was 5.1 points lower than in the SHUTi group, indicating that SHUTi was inferior at that time. At six months, mean ISI score was 3.3 points lower in the in-person group than in the SHUTi group. Because part of the confidence interval overlapped with the noninferiority margin, the result was inconclusive.

After treatment, the response rate was 70% in the in-person group and 43% in the SHUTi group. The remission rate was 52% in the in-person group and 18% in the SHUTi group. At six months, the response rate was 65% for the in-person group and 46% for the SHUTi group. The remission rate was 56% in the in-person group and 24% in the SHUTi group.

“SHUTi did not have the same effectiveness in this patient sample, compared with previous studies,” said Dr. Kallestad. One reason could be that previous studies included self-selected participants, rather than patients who had been referred to a sleep clinic. Also, the researchers interviewed all participants at baseline, and SHUTi might have seemed “more limited” in comparison with the interview, Dr. Kallestad concluded.

Digital CBT-I May Prevent Incident Depression

Insomnia is a modifiable risk factor for depression, and research has indicated that CBT-I reduces the severity of depression. Investigators also have shown that digitally delivered CBT-I effectively reduces insomnia and depression. Phillip C. Cheng, PhD, a researcher at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, and colleagues sought to determine whether digitally delivered CBT-I could prevent incident depression.

The researchers randomized 658 people with insomnia to Sleepio, an Internet-based CBT-I treatment, or to a control condition of online sleep education. The study’s primary outcome was the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), and Dr. Cheng’s group defined depression as a score greater than 10 on the QIDS. The researchers also examined participants’ ISI scores and functional outcomes such as work productivity, social functioning, cognitive functioning, and resilience. Assessments were performed at baseline, after treatment, and at one year.

In all, 358 participants were randomized to Sleepio, and 300 were randomized to sleep education. The patient population was predominantly female, was racially diverse, and had a diversity of educational attainment. The demographics of the study arms did not differ significantly.

After treatment, the rate of incident depression was 11% in the sleep education group and 6.5% in the Sleepio group. The difference between arms was not statistically significant. At one year, the rate of incident depression was 22% in the sleep education group and 5.1% in the Sleepio group. The difference between arms at one year was statistically significant, as was the change in depression incidence over time in the sleep education group.

Among patients who did not develop depression, ISI score decreased to a value below the cutoff for insomnia, regardless of study arm. ISI score did not change significantly among participants who developed depression, however. Work productivity, social functioning, cognitive functioning, and resilience improved more in the Sleepio group than in the sleep education group.

The results indicate that “digitally delivered CBT-I may prevent incident depression in adults with insomnia,” said Dr. Cheng. Each episode of depression increases the risk of relapse of depression, which underscores the significance of preventing incident depression, he added. Digital CBT-I also appears to reduce the economic burden associated with depression, and further studies could clarify whether it improves resilience, Dr. Cheng concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Espie CA, Kyle SD, Williams C, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep. 2012;35(6):769-781.

Gehrman P, Shah MT, Miles A, et al. Feasibility of group cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia delivered by clinical video telehealth. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1041-1046.

Hagatun S, Vedaa Ø, Nordgreen T, et al. The short-term efficacy of an unguided internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial with a six-month nonrandomized follow-up. Behav Sleep Med. 2017 Mar 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Ye YY, Chen NK, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e010707.

BALTIMORE—Cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I) is an effective treatment, but a scarcity of trained clinicians has limited patients’ access to it. Telehealth and Internet-based platforms could broaden access to CBT-I, and investigators presented research on the efficacy of these methods of administration at the 32nd Annual Meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

CBT-I by Telehealth Is Noninferior to In-Person CBT-I

Philip Gehrman, PhD, Associate Professor of Psychology at the University of Pennsylvania and the Philadelphia VA Medical Center, and colleagues conducted a cluster-randomized trial to determine whether group CBT-I delivered by telehealth was noninferior to CBT-I delivered in person. Eligible participants were veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and an Insomnia Severity Index (ISI) score of 15 or higher. The investigators randomized 95 participants in groups of six to eight to group CBT-I in person or by telehealth. The primary outcome was the change in ISI score from baseline to the three-month follow-up. Dr. Gehrman and colleagues defined treatment inferiority as a difference of greater than two points on the ISI score.

Participants’ mean age was 55.6, about 91% of the sample was male, and 42.2% of the sample was African American. The study population generally was overweight and had severe PTSD. Approximately half of the population was receiving one or more psychotropic medication. Forty-six participants were randomized to in-person CBT-I, and 49 were randomized to CBT-I delivered by telehealth.

At three months, the mean change in ISI score was 6.48 for in-person CBT-I and 4.45 for telehealth CBT-I. The difference between groups was outside of the prespecified margin of inferiority, and the researchers concluded that CBT-I delivered by telehealth was noninferior to in-person CBT-I.

The overall effectiveness of both methods of administration was modest, said Dr. Gehrman. The effect size might be greater in a group with fewer comorbidities or in a group that received more treatment sessions, he added. Nevertheless, the results “demonstrate that CBT-I can be effective even in a complex patient population,” he concluded.

SHUTi May Be Inferior to In-Person CBT-I

The online CBT-I intervention Sleep Healthy Using the Internet (SHUTi) has reduced insomnia with effect sizes similar to those of traditional CBT-I. No researchers had compared the two techniques directly, however. Håvard Kallestad, PhD, a clinical psychologist at Saint Olav’s Hospital in Trondheim, Norway, and colleagues examined whether SHUTi was a noninferior treatment for insomnia, compared with in-person CBT-I.

Eligible participants were 18 or older, had a diagnosis of insomnia, had been referred to a sleep clinic, and had access to a computer and adequate computer skills. Participants were randomized to in-person CBT-I or SHUTi. The primary outcome was ISI score, and three therapists assessed participants’ outcomes at baseline, after treatment, and at six months. They defined noninferiority as a difference between treatments of 2 or fewer points on ISI score.

Dr. Kallestad and colleagues randomized 52 participants to in-person CBT-I and 49 to SHUTi. Mean duration of insomnia was about 13 years. Approximately 60% of participants were currently using sleep medication, and about 90% had had previous treatment with sleep medication. After treatment, two patients in the in-person group and five in the SHUTi group were lost to follow-up. At six months, four participants in the in-person group and eight in the SHUTi group were lost to follow-up.

Both study arms had significantly lower ISI scores after treatment and at six months. After treatment, the mean ISI score in the in-person group was 5.1 points lower than in the SHUTi group, indicating that SHUTi was inferior at that time. At six months, mean ISI score was 3.3 points lower in the in-person group than in the SHUTi group. Because part of the confidence interval overlapped with the noninferiority margin, the result was inconclusive.

After treatment, the response rate was 70% in the in-person group and 43% in the SHUTi group. The remission rate was 52% in the in-person group and 18% in the SHUTi group. At six months, the response rate was 65% for the in-person group and 46% for the SHUTi group. The remission rate was 56% in the in-person group and 24% in the SHUTi group.

“SHUTi did not have the same effectiveness in this patient sample, compared with previous studies,” said Dr. Kallestad. One reason could be that previous studies included self-selected participants, rather than patients who had been referred to a sleep clinic. Also, the researchers interviewed all participants at baseline, and SHUTi might have seemed “more limited” in comparison with the interview, Dr. Kallestad concluded.

Digital CBT-I May Prevent Incident Depression

Insomnia is a modifiable risk factor for depression, and research has indicated that CBT-I reduces the severity of depression. Investigators also have shown that digitally delivered CBT-I effectively reduces insomnia and depression. Phillip C. Cheng, PhD, a researcher at the Henry Ford Health System in Detroit, and colleagues sought to determine whether digitally delivered CBT-I could prevent incident depression.

The researchers randomized 658 people with insomnia to Sleepio, an Internet-based CBT-I treatment, or to a control condition of online sleep education. The study’s primary outcome was the Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS), and Dr. Cheng’s group defined depression as a score greater than 10 on the QIDS. The researchers also examined participants’ ISI scores and functional outcomes such as work productivity, social functioning, cognitive functioning, and resilience. Assessments were performed at baseline, after treatment, and at one year.

In all, 358 participants were randomized to Sleepio, and 300 were randomized to sleep education. The patient population was predominantly female, was racially diverse, and had a diversity of educational attainment. The demographics of the study arms did not differ significantly.

After treatment, the rate of incident depression was 11% in the sleep education group and 6.5% in the Sleepio group. The difference between arms was not statistically significant. At one year, the rate of incident depression was 22% in the sleep education group and 5.1% in the Sleepio group. The difference between arms at one year was statistically significant, as was the change in depression incidence over time in the sleep education group.

Among patients who did not develop depression, ISI score decreased to a value below the cutoff for insomnia, regardless of study arm. ISI score did not change significantly among participants who developed depression, however. Work productivity, social functioning, cognitive functioning, and resilience improved more in the Sleepio group than in the sleep education group.

The results indicate that “digitally delivered CBT-I may prevent incident depression in adults with insomnia,” said Dr. Cheng. Each episode of depression increases the risk of relapse of depression, which underscores the significance of preventing incident depression, he added. Digital CBT-I also appears to reduce the economic burden associated with depression, and further studies could clarify whether it improves resilience, Dr. Cheng concluded.

—Erik Greb

Suggested Reading

Espie CA, Kyle SD, Williams C, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of online cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic insomnia disorder delivered via an automated media-rich web application. Sleep. 2012;35(6):769-781.

Gehrman P, Shah MT, Miles A, et al. Feasibility of group cognitive-behavioral treatment of insomnia delivered by clinical video telehealth. Telemed J E Health. 2016;22(12):1041-1046.

Hagatun S, Vedaa Ø, Nordgreen T, et al. The short-term efficacy of an unguided internet-based cognitive-behavioral therapy for insomnia: a randomized controlled trial with a six-month nonrandomized follow-up. Behav Sleep Med. 2017 Mar 27 [Epub ahead of print].

Ye YY, Chen NK, Chen J, et al. Internet-based cognitive-behavioural therapy for insomnia (ICBT-i): a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ Open. 2016;6(11):e010707.

Outcomes Associated With Shorter Wait Times at a County Hospital Outpatient Dermatology Clinic

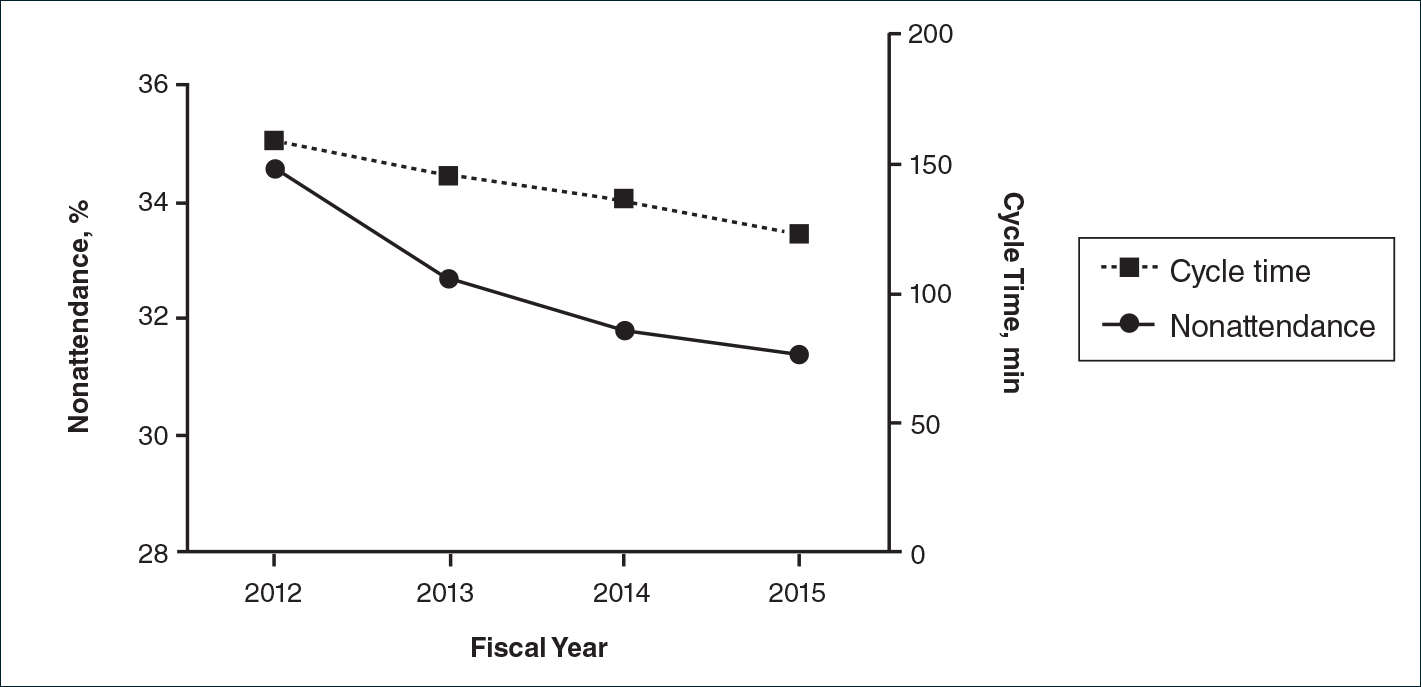

Maximizing productivity is prudent for outpatient subspecialty clinics to improve access to care. The outpatient dermatology clinic at Parkland Health and Hospital System in Dallas, Texas, which is a safety-net hospital in Dallas County, decreased wait times for new patients (from 377 to 48 days) and follow-up patients (from 95 to 34 days) from May 2012 to September 2015.1 Changes in clinic productivity measures that occur with decreased wait times are not well characterized; therefore, we sought to address this knowledge gap. We propose that decreased wait times are associated with improvement in additional clinic productivity measures, specifically decreases in nonattendance and cycle times (defined as time between patient check-in and discharge) as well as increases in referrals.

In our retrospective cohort study of patients seen in the Parkland outpatient dermatology clinic between fiscal year (FY) 2012 and FY 2015 (between October 2011 and September 2015), we collected data on patient nonattendance rates, cycle times, and referral volumes. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and changes in cycle times were analyzed using 2-way analysis of variance. P<.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were 52,775 scheduled clinic visits from FY 2012 to FY 2015. The overall proportion of patient nonattendance rates decreased from 34.6% (4202/12,141) to 31.4% (4429/14,119)(P<.001)(Figure), despite an increase in completed patient visits during the study period (7939 vs 9690). New patient nonattendance rates decreased from 42.9% (1831/4269) to 30.2% (1474/4874)(P<.001). The number of completed visits for new patients increased from 2438 in FY 2012 to 3400 in FY 2015. Follow-up nonattendance rates increased from 30.1% (2371/7872) to 32.0% (2955/9245)(P<.001). Follow-up completed visits increased from 5501 in FY 2012 to 6290 in FY 2015. Overall, average cycle time showed a trend to decrease from 159 to 123 minutes (22.6%)(Figure). Average cycle times were reduced from 159 to 128 minutes (19.5%) for new patients and from 161 to 115 minutes (28.6%) for follow-up patients (P=.02). Overall, referrals increased by 14.1% (816/5799)(P<.001), which was largely due to the increase in volume of referrals observed between FY 2014 (n=5770) and FY 2015 (n=6615).

We have demonstrated that decreased wait times can be associated with improvements in clinic productivity measures, namely decreased nonattendance rates and cycle times and increased referrals. Patient nonattendance is a burden on clinic resources and has been described in the dermatology clinic setting.2-6 Increased likelihood of nonattendance has been associated with prolonged wait times.3,7 We propose that decreased wait times can lead to diminished nonattendance rates, as patients are more likely to keep their appointments rather than seek other providers for dermatologic care. The difference in trends between new patient and follow-up nonattendance rates may be attributed to the larger relative increase in completed new patient visits compared to follow-ups during the study period.