User login

Myo-inositol is one of the components of an integrative approach to acne

, Jonette Elizabeth Keri, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Miami, said during a presentation on therapies for acne at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

Probiotics and omega-3 fatty acids are among the other complementary therapies that have a role in acne treatment, she and others said during the meeting.

Myo-inositol has been well-studied in the gynecology-endocrinology community in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), demonstrating an ability to improve the metabolic profile and reduce acne and hirsutism, Dr. Keri said.

A study of 137 young, overweight women with PCOS and moderate acne, for example, found that compared with placebo, 6 months of myo-inositol or D-chiro-inositol, another isoform of inositol, significantly improved the acne score, endocrine and metabolic parameters, insulin resistance, and regularity of the menstrual cycle, Dr. Keri said. Both isoforms of inositol are second messengers in the signal transduction of insulin.

During a panel discussion, asked about a case of an adult female with acne, Dr. Keri said that many of her adult female patients “don’t want to do isotretinoin or antibiotics, and they don’t want to do any kind of hormonal treatment,” the options she would recommend. But for patients who do not want these treatments, she said, “I go down the route of supplements,” and myo-inositol is her “favorite” option. It’s safe to use during pregnancy, she emphasized, noting that myo-inositol is being studied for the prevention of preterm birth.

Dr. Keri, who described herself as “more of a traditionalist,” prescribes myo-inositol 2 gm twice a day in pill form. In Europe, she noted in her presentation, myo-inositol is also compounded for topical use.

Diet, probiotics, other nutraceuticals

A low-glycemic-load diet was among several complementary therapies reported in a 2015 Cochrane Database Systematic Review to have some evidence (though low-quality) of reducing total skin lesions in acne (along with tea tree oil and bee venom) and today, it is the most evidence-based dietary recommendation for acne, Dr. Keri said.

Omega-3 fatty acids and increased fruit and vegetable intake have also been reported to be acne-protective — and hyperglycemia, carbohydrates, milk and dairy products, and saturated fats and trans fats have been reported to be acne-promoting, she noted.

But, the low-glycemic-load data “is the strongest,” she said. The best advice for patients, she added, is to consume less sugar and fewer sugary drinks and “avoid white foods” such as white bread, rice, and pasta.

Probiotics can also be recommended, especially for patients on antibiotic therapy, Dr. Keri said. For “basic science evidence,” she pointed to a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of 20 adults with acne, which evaluated the impact of a probiotic on improvement in acne and skin expression of genes involved with insulin signaling. Participants took either a liquid supplement containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus SP1 (LSP1) or placebo over a 12-week period. The investigators performed paired skin biopsies before and after 12 weeks of treatment and analyzed them for insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) gene expression.

They found that compared with baseline, the probiotic group showed a 32% reduction in IGF1 and a 65% increase in FOXO1 gene expression (P < .0001 for both), with no such differences observed in the placebo group.

Clinically, patients in the probiotic group had an adjusted odds ratio of 28.4 (95% confidence interval, 2.2-411.1, P < .05) of acne being rated as improved or markedly improved compared with those on placebo.

Dr. Keri and others at the meeting also referenced a 2013 prospective, open-label trial that randomized 45 women with acne, ages 18-35 years, to one of three arms: Probiotic supplementation only, minocycline only, and both probiotic and minocycline. The probiotic used was a product containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Bifidobacterium bifidum. At 8 and 12 weeks, the combination group “did the best with the lowest total lesion count” compared with the probiotic group and the minocycline group, differences that were significant (P < .001 and P <.01, respectively), she said. “And they also had less candidiasis when using a probiotic than when using an antibiotic alone,” she said. Two patients in the minocycline-only group failed to complete the study because they developed vaginal candidiasis.

In addition to reducing potential adverse events secondary to chronic antibiotic use, probiotics can have synergistic anti-inflammatory effects, she said.

Dr. Keri said she recommends probiotics for patients taking antibiotics and encourages them “to get a branded probiotic,” such as Culturelle, “or if they prefer a food source, soy or almond milk–based yogurt.” As with other elements of a holistic approach to acne, she urged clinicians to consider the cost of treatment.

Probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum) were one of four nutraceuticals determined in a 2023 systematic review to have “good-quality” evidence for potential efficacy, Dr. Keri noted, along with vitamin D, green tea extract, and cheongsangbangpoong-tang, the latter of which is an herbal therapeutic formula approved by the Korean Food and Drug Administration for use in acne.

“There were really no bad systemic effects for any of these,” she said. “The tricky part of this review is that each of the four have only one study” deemed to be a good-quality study. Omega-3 fatty acids were among several other nutraceuticals deemed to have “fair-quality” evidence for efficacy. Zinc was reported to be the most studied nutraceutical in acne, but didn’t rate as highly in the review. Dr. Keri said she likes to include zinc in her armamentarium because “it can be used in pregnant women,” noting that reviews and guidelines “are just that, a guide ... to combine with experience.”

Omega-3 fatty acids with isotretinoin

Several speakers at the meeting, including Steven Daveluy, MD, associate professor and residency program director in the department of dermatology, Wayne State University, Dearborn, Michigan, spoke about the value of omega-3 fatty acids in reducing side effects of isotretinoin. “In the FDA trials [of isotretinoin] they had patients take 50 grams of fat,” he said. “You can use the good fats to help you out.”

Research has shown that 1 gm per day of oral omega-3 reduces dryness of the lips, nose, eyes, and skin, “which are the big side effects we see with isotretinoin,” he said. An impact on triglyceride levels has also been demonstrated, Dr. Daveluy said, pointing to a longitudinal survey study of 39 patients treated with isotretinoin that showed a mean increase in triglyceride levels of 49% during treatment in patients who did not use omega-3 supplementation, compared with a mean increase of 13.9% (P =.04) in patients who used the supplements.“There is also evidence that omega-3 can decrease depression, which may or may not be a side effect of isotretinoin ... but it’s something we consider in our [acne] patients,” Dr. Daveluy said.

During a panel discussion at the meeting, Apple A. Bodemer, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said she usually prescribes 2 g of docosahexaenoic acid eicosapentaenoic acid combined in patients on isotretinoin because “at that dose, omega-3s have been found to be anti-inflammatory.”

Dr. Keri reported being an investigator and speaker for Galderma, and an advisory board member for Ortho Dermatologics and for Almirall. Dr. Daveluy reported no relevant disclosures.

, Jonette Elizabeth Keri, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Miami, said during a presentation on therapies for acne at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

Probiotics and omega-3 fatty acids are among the other complementary therapies that have a role in acne treatment, she and others said during the meeting.

Myo-inositol has been well-studied in the gynecology-endocrinology community in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), demonstrating an ability to improve the metabolic profile and reduce acne and hirsutism, Dr. Keri said.

A study of 137 young, overweight women with PCOS and moderate acne, for example, found that compared with placebo, 6 months of myo-inositol or D-chiro-inositol, another isoform of inositol, significantly improved the acne score, endocrine and metabolic parameters, insulin resistance, and regularity of the menstrual cycle, Dr. Keri said. Both isoforms of inositol are second messengers in the signal transduction of insulin.

During a panel discussion, asked about a case of an adult female with acne, Dr. Keri said that many of her adult female patients “don’t want to do isotretinoin or antibiotics, and they don’t want to do any kind of hormonal treatment,” the options she would recommend. But for patients who do not want these treatments, she said, “I go down the route of supplements,” and myo-inositol is her “favorite” option. It’s safe to use during pregnancy, she emphasized, noting that myo-inositol is being studied for the prevention of preterm birth.

Dr. Keri, who described herself as “more of a traditionalist,” prescribes myo-inositol 2 gm twice a day in pill form. In Europe, she noted in her presentation, myo-inositol is also compounded for topical use.

Diet, probiotics, other nutraceuticals

A low-glycemic-load diet was among several complementary therapies reported in a 2015 Cochrane Database Systematic Review to have some evidence (though low-quality) of reducing total skin lesions in acne (along with tea tree oil and bee venom) and today, it is the most evidence-based dietary recommendation for acne, Dr. Keri said.

Omega-3 fatty acids and increased fruit and vegetable intake have also been reported to be acne-protective — and hyperglycemia, carbohydrates, milk and dairy products, and saturated fats and trans fats have been reported to be acne-promoting, she noted.

But, the low-glycemic-load data “is the strongest,” she said. The best advice for patients, she added, is to consume less sugar and fewer sugary drinks and “avoid white foods” such as white bread, rice, and pasta.

Probiotics can also be recommended, especially for patients on antibiotic therapy, Dr. Keri said. For “basic science evidence,” she pointed to a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of 20 adults with acne, which evaluated the impact of a probiotic on improvement in acne and skin expression of genes involved with insulin signaling. Participants took either a liquid supplement containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus SP1 (LSP1) or placebo over a 12-week period. The investigators performed paired skin biopsies before and after 12 weeks of treatment and analyzed them for insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) gene expression.

They found that compared with baseline, the probiotic group showed a 32% reduction in IGF1 and a 65% increase in FOXO1 gene expression (P < .0001 for both), with no such differences observed in the placebo group.

Clinically, patients in the probiotic group had an adjusted odds ratio of 28.4 (95% confidence interval, 2.2-411.1, P < .05) of acne being rated as improved or markedly improved compared with those on placebo.

Dr. Keri and others at the meeting also referenced a 2013 prospective, open-label trial that randomized 45 women with acne, ages 18-35 years, to one of three arms: Probiotic supplementation only, minocycline only, and both probiotic and minocycline. The probiotic used was a product containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Bifidobacterium bifidum. At 8 and 12 weeks, the combination group “did the best with the lowest total lesion count” compared with the probiotic group and the minocycline group, differences that were significant (P < .001 and P <.01, respectively), she said. “And they also had less candidiasis when using a probiotic than when using an antibiotic alone,” she said. Two patients in the minocycline-only group failed to complete the study because they developed vaginal candidiasis.

In addition to reducing potential adverse events secondary to chronic antibiotic use, probiotics can have synergistic anti-inflammatory effects, she said.

Dr. Keri said she recommends probiotics for patients taking antibiotics and encourages them “to get a branded probiotic,” such as Culturelle, “or if they prefer a food source, soy or almond milk–based yogurt.” As with other elements of a holistic approach to acne, she urged clinicians to consider the cost of treatment.

Probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum) were one of four nutraceuticals determined in a 2023 systematic review to have “good-quality” evidence for potential efficacy, Dr. Keri noted, along with vitamin D, green tea extract, and cheongsangbangpoong-tang, the latter of which is an herbal therapeutic formula approved by the Korean Food and Drug Administration for use in acne.

“There were really no bad systemic effects for any of these,” she said. “The tricky part of this review is that each of the four have only one study” deemed to be a good-quality study. Omega-3 fatty acids were among several other nutraceuticals deemed to have “fair-quality” evidence for efficacy. Zinc was reported to be the most studied nutraceutical in acne, but didn’t rate as highly in the review. Dr. Keri said she likes to include zinc in her armamentarium because “it can be used in pregnant women,” noting that reviews and guidelines “are just that, a guide ... to combine with experience.”

Omega-3 fatty acids with isotretinoin

Several speakers at the meeting, including Steven Daveluy, MD, associate professor and residency program director in the department of dermatology, Wayne State University, Dearborn, Michigan, spoke about the value of omega-3 fatty acids in reducing side effects of isotretinoin. “In the FDA trials [of isotretinoin] they had patients take 50 grams of fat,” he said. “You can use the good fats to help you out.”

Research has shown that 1 gm per day of oral omega-3 reduces dryness of the lips, nose, eyes, and skin, “which are the big side effects we see with isotretinoin,” he said. An impact on triglyceride levels has also been demonstrated, Dr. Daveluy said, pointing to a longitudinal survey study of 39 patients treated with isotretinoin that showed a mean increase in triglyceride levels of 49% during treatment in patients who did not use omega-3 supplementation, compared with a mean increase of 13.9% (P =.04) in patients who used the supplements.“There is also evidence that omega-3 can decrease depression, which may or may not be a side effect of isotretinoin ... but it’s something we consider in our [acne] patients,” Dr. Daveluy said.

During a panel discussion at the meeting, Apple A. Bodemer, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said she usually prescribes 2 g of docosahexaenoic acid eicosapentaenoic acid combined in patients on isotretinoin because “at that dose, omega-3s have been found to be anti-inflammatory.”

Dr. Keri reported being an investigator and speaker for Galderma, and an advisory board member for Ortho Dermatologics and for Almirall. Dr. Daveluy reported no relevant disclosures.

, Jonette Elizabeth Keri, MD, PhD, professor of dermatology at the University of Miami, said during a presentation on therapies for acne at the annual Integrative Dermatology Symposium.

Probiotics and omega-3 fatty acids are among the other complementary therapies that have a role in acne treatment, she and others said during the meeting.

Myo-inositol has been well-studied in the gynecology-endocrinology community in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), demonstrating an ability to improve the metabolic profile and reduce acne and hirsutism, Dr. Keri said.

A study of 137 young, overweight women with PCOS and moderate acne, for example, found that compared with placebo, 6 months of myo-inositol or D-chiro-inositol, another isoform of inositol, significantly improved the acne score, endocrine and metabolic parameters, insulin resistance, and regularity of the menstrual cycle, Dr. Keri said. Both isoforms of inositol are second messengers in the signal transduction of insulin.

During a panel discussion, asked about a case of an adult female with acne, Dr. Keri said that many of her adult female patients “don’t want to do isotretinoin or antibiotics, and they don’t want to do any kind of hormonal treatment,” the options she would recommend. But for patients who do not want these treatments, she said, “I go down the route of supplements,” and myo-inositol is her “favorite” option. It’s safe to use during pregnancy, she emphasized, noting that myo-inositol is being studied for the prevention of preterm birth.

Dr. Keri, who described herself as “more of a traditionalist,” prescribes myo-inositol 2 gm twice a day in pill form. In Europe, she noted in her presentation, myo-inositol is also compounded for topical use.

Diet, probiotics, other nutraceuticals

A low-glycemic-load diet was among several complementary therapies reported in a 2015 Cochrane Database Systematic Review to have some evidence (though low-quality) of reducing total skin lesions in acne (along with tea tree oil and bee venom) and today, it is the most evidence-based dietary recommendation for acne, Dr. Keri said.

Omega-3 fatty acids and increased fruit and vegetable intake have also been reported to be acne-protective — and hyperglycemia, carbohydrates, milk and dairy products, and saturated fats and trans fats have been reported to be acne-promoting, she noted.

But, the low-glycemic-load data “is the strongest,” she said. The best advice for patients, she added, is to consume less sugar and fewer sugary drinks and “avoid white foods” such as white bread, rice, and pasta.

Probiotics can also be recommended, especially for patients on antibiotic therapy, Dr. Keri said. For “basic science evidence,” she pointed to a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study of 20 adults with acne, which evaluated the impact of a probiotic on improvement in acne and skin expression of genes involved with insulin signaling. Participants took either a liquid supplement containing Lactobacillus rhamnosus SP1 (LSP1) or placebo over a 12-week period. The investigators performed paired skin biopsies before and after 12 weeks of treatment and analyzed them for insulin-like growth factor 1 (IGF1) and forkhead box protein O1 (FOXO1) gene expression.

They found that compared with baseline, the probiotic group showed a 32% reduction in IGF1 and a 65% increase in FOXO1 gene expression (P < .0001 for both), with no such differences observed in the placebo group.

Clinically, patients in the probiotic group had an adjusted odds ratio of 28.4 (95% confidence interval, 2.2-411.1, P < .05) of acne being rated as improved or markedly improved compared with those on placebo.

Dr. Keri and others at the meeting also referenced a 2013 prospective, open-label trial that randomized 45 women with acne, ages 18-35 years, to one of three arms: Probiotic supplementation only, minocycline only, and both probiotic and minocycline. The probiotic used was a product containing Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus bulgaricus, and Bifidobacterium bifidum. At 8 and 12 weeks, the combination group “did the best with the lowest total lesion count” compared with the probiotic group and the minocycline group, differences that were significant (P < .001 and P <.01, respectively), she said. “And they also had less candidiasis when using a probiotic than when using an antibiotic alone,” she said. Two patients in the minocycline-only group failed to complete the study because they developed vaginal candidiasis.

In addition to reducing potential adverse events secondary to chronic antibiotic use, probiotics can have synergistic anti-inflammatory effects, she said.

Dr. Keri said she recommends probiotics for patients taking antibiotics and encourages them “to get a branded probiotic,” such as Culturelle, “or if they prefer a food source, soy or almond milk–based yogurt.” As with other elements of a holistic approach to acne, she urged clinicians to consider the cost of treatment.

Probiotics (Lactobacillus plantarum) were one of four nutraceuticals determined in a 2023 systematic review to have “good-quality” evidence for potential efficacy, Dr. Keri noted, along with vitamin D, green tea extract, and cheongsangbangpoong-tang, the latter of which is an herbal therapeutic formula approved by the Korean Food and Drug Administration for use in acne.

“There were really no bad systemic effects for any of these,” she said. “The tricky part of this review is that each of the four have only one study” deemed to be a good-quality study. Omega-3 fatty acids were among several other nutraceuticals deemed to have “fair-quality” evidence for efficacy. Zinc was reported to be the most studied nutraceutical in acne, but didn’t rate as highly in the review. Dr. Keri said she likes to include zinc in her armamentarium because “it can be used in pregnant women,” noting that reviews and guidelines “are just that, a guide ... to combine with experience.”

Omega-3 fatty acids with isotretinoin

Several speakers at the meeting, including Steven Daveluy, MD, associate professor and residency program director in the department of dermatology, Wayne State University, Dearborn, Michigan, spoke about the value of omega-3 fatty acids in reducing side effects of isotretinoin. “In the FDA trials [of isotretinoin] they had patients take 50 grams of fat,” he said. “You can use the good fats to help you out.”

Research has shown that 1 gm per day of oral omega-3 reduces dryness of the lips, nose, eyes, and skin, “which are the big side effects we see with isotretinoin,” he said. An impact on triglyceride levels has also been demonstrated, Dr. Daveluy said, pointing to a longitudinal survey study of 39 patients treated with isotretinoin that showed a mean increase in triglyceride levels of 49% during treatment in patients who did not use omega-3 supplementation, compared with a mean increase of 13.9% (P =.04) in patients who used the supplements.“There is also evidence that omega-3 can decrease depression, which may or may not be a side effect of isotretinoin ... but it’s something we consider in our [acne] patients,” Dr. Daveluy said.

During a panel discussion at the meeting, Apple A. Bodemer, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, said she usually prescribes 2 g of docosahexaenoic acid eicosapentaenoic acid combined in patients on isotretinoin because “at that dose, omega-3s have been found to be anti-inflammatory.”

Dr. Keri reported being an investigator and speaker for Galderma, and an advisory board member for Ortho Dermatologics and for Almirall. Dr. Daveluy reported no relevant disclosures.

FROM IDS 2023

Appetite loss and unusual agitation

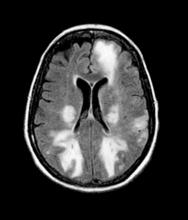

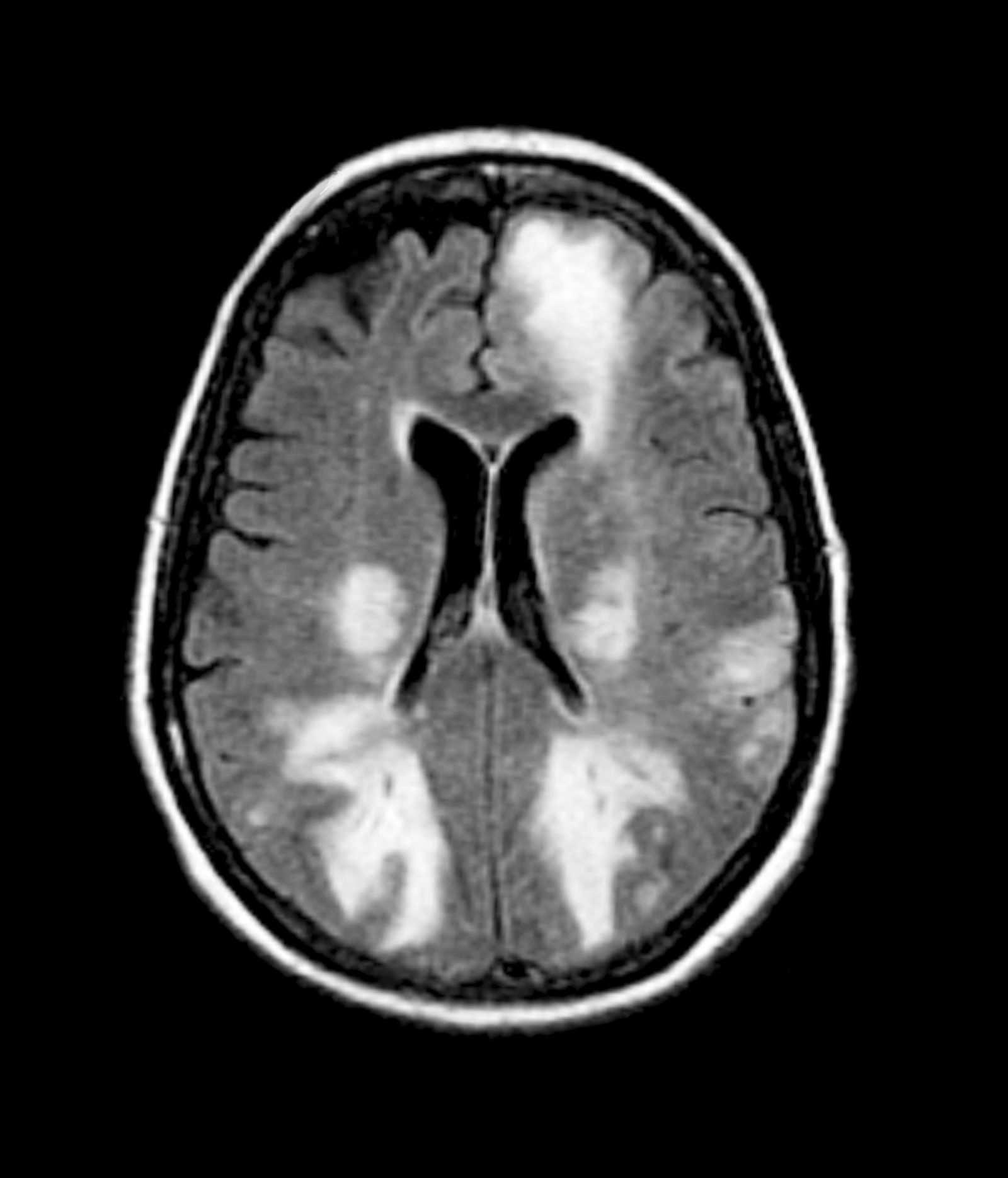

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

Given the patient's results on the genetic panel and MRI, as well as the noted cognitive decline and increased aggression, this patient is suspected of having limbic-predominant age-related TDP-43 encephalopathy (LATE) secondary to AD and is referred to the neurologist on her multidisciplinary care team for further consultation and testing.

AD is one of the most common forms of dementia. More than 6 million people in the United States have clinical AD or mild cognitive impairment because of AD. LATE is a new classification of dementia, identified in 2019, that mimics AD but is a unique disease entity driven by the misfolding of the protein TDP-43, which regulates gene expression in the brain. Misfolded TDP-43 protein is common among older adults aged ≥ 85 years, and about a quarter of this population has enough misfolded TDP-43 protein to affect their memory and cognition.

Diagnosing AD currently relies on a clinical approach. A complete physical examination, with a detailed neurologic examination and a mental status examination, is used to evaluate disease stage. Initial mental status testing evaluates attention and concentration, recent and remote memory, language, praxis, executive function, and visuospatial function. Because LATE is a newly discovered form of dementia, there are no set guidelines on diagnosing LATE and no robust biomarker for TDP-43. What is known about LATE has been gleaned mostly from retrospective clinicopathologic studies.

The LATE consensus working group reports that the clinical course of disease, as studied by autopsy-proven LATE neuropathologic change (LATE-NC), is described as an "amnestic cognitive syndrome that can evolve to incorporate multiple cognitive domains and ultimately to impair activities of daily living." Researchers are currently analyzing different clinical assessments and neuroimaging with MRI to characterize LATE. A group of international researchers recently published a set of clinical criteria for limbic-predominant amnestic neurodegenerative syndrome (LANS), which is associated with LATE-NC. Their criteria include "core, standard and advanced features that are measurable in vivo, including older age at evaluation, mild clinical syndrome, disproportionate hippocampal atrophy, impaired semantic memory, limbic hypometabolism, absence of neocortical degenerative patterns and low likelihood of neocortical tau, with degrees of certainty (highest, high, moderate, low)." Other neuroimaging studies of autopsy-confirmed LATE-NC have shown that atrophy is mostly focused in the medial temporal lobe with marked reduced hippocampal volume.

The group reports that LATE and AD probably share pathophysiologic mechanisms. One of the universally accepted hallmarks of AD is the formation of beta-amyloid plaques, which are dense, mostly insoluble deposits of beta-amyloid protein that develop around neurons in the hippocampus and other regions in the cerebral cortex used for decision-making. These plaques disrupt brain function and lead to brain atrophy. The LATE group also reports that this same pathology has been noted with LATE: "Many subjects with LATE-NC have comorbid brain pathologies, often including amyloid-beta plaques and tauopathy." That said, genetic studies have helped identify five genes with risk alleles for LATE (GRN, TMEM106B, ABCC9, KCNMB2, and APOE), suggesting disease-specific underlying mechanisms compared to AD.

Patient and caregiver education and guidance is vital with a dementia diagnosis. If LATE and/or AD are suspected, physicians should encourage the involvement of family and friends who agree to become more involved in the patient's care as the disease progresses. These individuals need to understand the patient's wishes around care, especially for the future when the patient is no longer able to make decisions. The patient may also consider establishing medical advance directives and durable power of attorney for medical and financial decision-making. Caregivers supporting the patient are encouraged to help balance the physical needs of the patient while maintaining respect for them as a competent adult to the extent allowed by the progression of their disease.

Because LATE is a new classification of dementia, there are no known effective treatments. One ongoing study is testing the use of autologous bone marrow–derived stem cells to help improve cognitive impairment among patients with LATE, AD, and other dementias. Current AD treatments are focused on symptomatic therapies that modulate neurotransmitters — either acetylcholine or glutamate. The standard medical treatment includes cholinesterase inhibitors and a partial N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Two amyloid-directed antibodies (aducanumab, lecanemab) are currently available in the United States for individuals with AD exhibiting mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. A third agent currently in clinical trials (donanemab) has shown significantly slowed clinical progression after 1.5 years among clinical trial participants with early symptomatic AD and amyloid and tau pathology.

Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, Chief of Pain Management, Carilion Clinic and Virginia Tech Carilion School of Medicine, Roanoke, Virginia.

Disclosure: Shaheen E. Lakhan, MD, PhD, MS, MEd, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

Image Quizzes are fictional or fictionalized clinical scenarios intended to provide evidence-based educational takeaways.

An 85-year-old woman presents to her geriatrician with her daughter, who is her primary caregiver. Seven years ago, the patient was diagnosed with mild Alzheimer's disease (AD). Her symptoms at diagnosis were irritability, forgetfulness, and panic attacks. Cognitive, behavioral, and functional assessments showed levels of decline; neurologic examination revealed mild hyposmia. The patient has been living with her daughter ever since her AD diagnosis.

At today's visit, the daughter reports that her mother has been experiencing loss of appetite and wide mood fluctuations with moments of unusual agitation. In addition, she tells the geriatrician that her mother has had trouble maintaining her balance and seems to have lost her sense of time. The patient has difficulty remembering what month and day it is, and how long it's been since her brother came to visit — which has been every Sunday like clockwork since the patient moved in with her daughter. The daughter also notes that her mother loses track of the story line when she is watching movie and TV shows lately.

The physician orders a brain MRI and genetic panel. MRI reveals atrophy in the frontal cortex as well as the medial temporal lobe, with hippocampal sclerosis. The genetic panel shows APOE and TMEM106 mutations.

‘Fake Xanax’ Tied to Seizures, Coma Is Resistant to Naloxone

Bromazolam, a street drug that has been detected with increasing frequency in the United States, has reportedly caused protracted seizures, myocardial injury, comas, and multiday intensive care stays in three individuals, new data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed.

The substance is one of at least a dozen designer benzodiazepines created in the lab but not approved for any therapeutic use. The Center for Forensic Science Research and Education (CFSRE) reported that bromazolam was first detected in 2016 in recreational drugs in Europe and subsequently appeared in the United States.

It is sold under names such as “XLI-268,” “Xanax,” “Fake Xanax,” and “Dope.” Bromazolam may be sold in tablet or powder form, or sometimes as gummies, and is often taken with fentanyl by users.

The CDC report, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), described three cases of “previously healthy young adults,” two 25-year-old men and a 20-year-old woman, who took tablets believing it was alprazolam, when it was actually bromazolam and were found unresponsive.

They could not be revived with naloxone and continued to be unresponsive upon arrival at the emergency department. One of the men was hypertensive (152/100 mmHg), tachycardic (heart rate of 124 beats per minute), and hyperthermic (101.7 °F [38.7 °C]) and experienced multiple generalized seizures. He was intubated and admitted to intensive care.

The other man also had an elevated temperature (100.4 °F) and was intubated and admitted to the ICU because of unresponsiveness and multiple generalized seizures.

The woman was also intubated and nonresponsive with focal seizures. All three had elevated troponin levels and had urine tests positive for benzodiazepines.

The first man was intubated for 5 days and discharged after 11 days, while the second man was discharged on the fourth day with mild hearing difficulty.

The woman progressed to status epilepticus despite administration of multiple antiepileptic medications and was in a persistent coma. She was transferred to a second hospital after 11 days and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Toxicology testing by the Drug Enforcement Administration confirmed the presence of bromazolam (range = 31.1-207 ng/mL), without the presence of fentanyl or any other opioid.

The CDC said that “the constellation of findings reported should prompt close involvement with public health officials and regional poison centers, given the more severe findings in these reported cases compared with those expected from routine benzodiazepine overdoses.” In addition, it noted that clinicians and first responders should “consider bromazolam in cases of patients requiring treatment for seizures, myocardial injury, or hyperthermia after illicit drug use.”

Surging Supply, Increased Warnings

In 2022, the CDC warned that the drug was surging in the United States, noting that as of mid-2022, bromazolam was identified in more than 250 toxicology cases submitted to NMS Labs, and that it had been identified in more than 190 toxicology samples tested at CFSRE.

In early 2021, only 1% of samples were positive for bromazolam. By mid-2022, 13% of samples were positive for bromazolam, and 75% of the bromazolam samples were positive for fentanyl.

The combination is sold on the street as benzo-dope.

Health authorities across the globe have been warning about the dangers of designer benzodiazepines, and bromazolam in particular. They’ve noted that the overdose reversal agent naloxone does not combat the effects of a benzodiazepine overdose.

In December 2022, the Canadian province of New Brunswick said that bromazolam had been detected in nine sudden death investigations, and that fentanyl was detected in some of those cases. The provincial government of the Northwest Territories warned in May 2023 that bromazolam had been detected in the region’s drug supply and cautioned against combining it with opioids.

The Indiana Department of Health notified the public, first responders, law enforcement, and clinicians in August 2023 that the drug was increasingly being detected in the state. In the first half of the year, 35 people who had overdosed in Indiana tested positive for bromazolam. The state did not test for the presence of bromazolam before 2023.

According to the MMWR, the law enforcement seizures in the United States of bromazolam increased from no more than three per year during 2016-2018 to 2142 in 2022 and 2913 in 2023.

Illinois has been an area of increased use. Bromazolam-involved deaths increased from 10 in 2021 to 51 in 2022, the CDC researchers reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Bromazolam, a street drug that has been detected with increasing frequency in the United States, has reportedly caused protracted seizures, myocardial injury, comas, and multiday intensive care stays in three individuals, new data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed.

The substance is one of at least a dozen designer benzodiazepines created in the lab but not approved for any therapeutic use. The Center for Forensic Science Research and Education (CFSRE) reported that bromazolam was first detected in 2016 in recreational drugs in Europe and subsequently appeared in the United States.

It is sold under names such as “XLI-268,” “Xanax,” “Fake Xanax,” and “Dope.” Bromazolam may be sold in tablet or powder form, or sometimes as gummies, and is often taken with fentanyl by users.

The CDC report, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), described three cases of “previously healthy young adults,” two 25-year-old men and a 20-year-old woman, who took tablets believing it was alprazolam, when it was actually bromazolam and were found unresponsive.

They could not be revived with naloxone and continued to be unresponsive upon arrival at the emergency department. One of the men was hypertensive (152/100 mmHg), tachycardic (heart rate of 124 beats per minute), and hyperthermic (101.7 °F [38.7 °C]) and experienced multiple generalized seizures. He was intubated and admitted to intensive care.

The other man also had an elevated temperature (100.4 °F) and was intubated and admitted to the ICU because of unresponsiveness and multiple generalized seizures.

The woman was also intubated and nonresponsive with focal seizures. All three had elevated troponin levels and had urine tests positive for benzodiazepines.

The first man was intubated for 5 days and discharged after 11 days, while the second man was discharged on the fourth day with mild hearing difficulty.

The woman progressed to status epilepticus despite administration of multiple antiepileptic medications and was in a persistent coma. She was transferred to a second hospital after 11 days and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Toxicology testing by the Drug Enforcement Administration confirmed the presence of bromazolam (range = 31.1-207 ng/mL), without the presence of fentanyl or any other opioid.

The CDC said that “the constellation of findings reported should prompt close involvement with public health officials and regional poison centers, given the more severe findings in these reported cases compared with those expected from routine benzodiazepine overdoses.” In addition, it noted that clinicians and first responders should “consider bromazolam in cases of patients requiring treatment for seizures, myocardial injury, or hyperthermia after illicit drug use.”

Surging Supply, Increased Warnings

In 2022, the CDC warned that the drug was surging in the United States, noting that as of mid-2022, bromazolam was identified in more than 250 toxicology cases submitted to NMS Labs, and that it had been identified in more than 190 toxicology samples tested at CFSRE.

In early 2021, only 1% of samples were positive for bromazolam. By mid-2022, 13% of samples were positive for bromazolam, and 75% of the bromazolam samples were positive for fentanyl.

The combination is sold on the street as benzo-dope.

Health authorities across the globe have been warning about the dangers of designer benzodiazepines, and bromazolam in particular. They’ve noted that the overdose reversal agent naloxone does not combat the effects of a benzodiazepine overdose.

In December 2022, the Canadian province of New Brunswick said that bromazolam had been detected in nine sudden death investigations, and that fentanyl was detected in some of those cases. The provincial government of the Northwest Territories warned in May 2023 that bromazolam had been detected in the region’s drug supply and cautioned against combining it with opioids.

The Indiana Department of Health notified the public, first responders, law enforcement, and clinicians in August 2023 that the drug was increasingly being detected in the state. In the first half of the year, 35 people who had overdosed in Indiana tested positive for bromazolam. The state did not test for the presence of bromazolam before 2023.

According to the MMWR, the law enforcement seizures in the United States of bromazolam increased from no more than three per year during 2016-2018 to 2142 in 2022 and 2913 in 2023.

Illinois has been an area of increased use. Bromazolam-involved deaths increased from 10 in 2021 to 51 in 2022, the CDC researchers reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Bromazolam, a street drug that has been detected with increasing frequency in the United States, has reportedly caused protracted seizures, myocardial injury, comas, and multiday intensive care stays in three individuals, new data from the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) showed.

The substance is one of at least a dozen designer benzodiazepines created in the lab but not approved for any therapeutic use. The Center for Forensic Science Research and Education (CFSRE) reported that bromazolam was first detected in 2016 in recreational drugs in Europe and subsequently appeared in the United States.

It is sold under names such as “XLI-268,” “Xanax,” “Fake Xanax,” and “Dope.” Bromazolam may be sold in tablet or powder form, or sometimes as gummies, and is often taken with fentanyl by users.

The CDC report, published in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR), described three cases of “previously healthy young adults,” two 25-year-old men and a 20-year-old woman, who took tablets believing it was alprazolam, when it was actually bromazolam and were found unresponsive.

They could not be revived with naloxone and continued to be unresponsive upon arrival at the emergency department. One of the men was hypertensive (152/100 mmHg), tachycardic (heart rate of 124 beats per minute), and hyperthermic (101.7 °F [38.7 °C]) and experienced multiple generalized seizures. He was intubated and admitted to intensive care.

The other man also had an elevated temperature (100.4 °F) and was intubated and admitted to the ICU because of unresponsiveness and multiple generalized seizures.

The woman was also intubated and nonresponsive with focal seizures. All three had elevated troponin levels and had urine tests positive for benzodiazepines.

The first man was intubated for 5 days and discharged after 11 days, while the second man was discharged on the fourth day with mild hearing difficulty.

The woman progressed to status epilepticus despite administration of multiple antiepileptic medications and was in a persistent coma. She was transferred to a second hospital after 11 days and was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Toxicology testing by the Drug Enforcement Administration confirmed the presence of bromazolam (range = 31.1-207 ng/mL), without the presence of fentanyl or any other opioid.

The CDC said that “the constellation of findings reported should prompt close involvement with public health officials and regional poison centers, given the more severe findings in these reported cases compared with those expected from routine benzodiazepine overdoses.” In addition, it noted that clinicians and first responders should “consider bromazolam in cases of patients requiring treatment for seizures, myocardial injury, or hyperthermia after illicit drug use.”

Surging Supply, Increased Warnings

In 2022, the CDC warned that the drug was surging in the United States, noting that as of mid-2022, bromazolam was identified in more than 250 toxicology cases submitted to NMS Labs, and that it had been identified in more than 190 toxicology samples tested at CFSRE.

In early 2021, only 1% of samples were positive for bromazolam. By mid-2022, 13% of samples were positive for bromazolam, and 75% of the bromazolam samples were positive for fentanyl.

The combination is sold on the street as benzo-dope.

Health authorities across the globe have been warning about the dangers of designer benzodiazepines, and bromazolam in particular. They’ve noted that the overdose reversal agent naloxone does not combat the effects of a benzodiazepine overdose.

In December 2022, the Canadian province of New Brunswick said that bromazolam had been detected in nine sudden death investigations, and that fentanyl was detected in some of those cases. The provincial government of the Northwest Territories warned in May 2023 that bromazolam had been detected in the region’s drug supply and cautioned against combining it with opioids.

The Indiana Department of Health notified the public, first responders, law enforcement, and clinicians in August 2023 that the drug was increasingly being detected in the state. In the first half of the year, 35 people who had overdosed in Indiana tested positive for bromazolam. The state did not test for the presence of bromazolam before 2023.

According to the MMWR, the law enforcement seizures in the United States of bromazolam increased from no more than three per year during 2016-2018 to 2142 in 2022 and 2913 in 2023.

Illinois has been an area of increased use. Bromazolam-involved deaths increased from 10 in 2021 to 51 in 2022, the CDC researchers reported.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM THE MORBIDITY AND MORTALITY WEEKLY REPORT

Side Effects of Local Treatment for Advanced Prostate Cancer May Linger for Years

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

Recent evidence suggested that in men with advanced prostate cancer, local therapy with radical prostatectomy or radiation may improve survival outcomes; however, data on the long-term side effects from these local options were limited.

The retrospective cohort included 5502 men (mean age, 68 years) diagnosed with advanced (T4, N1, and/or M1) prostate cancer.

A total of 1705 men (31%) received initial local treatment, consisting of radical prostatectomy, (55%), radiation (39%), or both (5.6%), while 3797 (69%) opted for initial nonlocal treatment (hormone therapy, chemotherapy, or both).

The main outcomes were treatment-related adverse effects, including GI, chronic pain, sexual dysfunction, and urinary symptoms, assessed at three timepoints after initial treatment — up to 1 year, between 1 and 2 years, and between 2 and 5 years.

TAKEAWAY:

Overall, 916 men (75%) who had initial local treatment and 897 men (67%) with initial nonlocal therapy reported at least one adverse condition up to 5 years after initial treatment.

In the first year after initial treatment, local therapy was associated with a higher prevalence of GI (9% vs 3%), pain (60% vs 38%), sexual (37% vs 8%), and urinary (46.5% vs 18%) conditions. Men receiving local therapy were more likely to experience GI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.08), pain (aOR, 1.57), sexual (aOR, 2.96), and urinary (aOR, 2.25) conditions.

Between 2 and 5 years after local therapy, certain conditions remained more prevalent — 7.8% vs 4.2% for GI, 40% vs 13% for sexual, and 40.5% vs 26% for urinary issues. Men receiving local vs nonlocal therapy were more likely to experience GI (aOR, 2.39), sexual (aOR, 3.36), and urinary (aOR, 1.39) issues over the long term.

The researchers found no difference in the prevalence of constitutional conditions such as hot flashes (36.5% vs 34.4%) in the first year following initial local or nonlocal therapy. However, local treatment followed by any secondary treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of developing constitutional conditions at 1-2 years (aOR, 1.50) and 2-5 years (aOR, 1.78) after initial treatment.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results suggest that patients and clinicians should consider the adverse effects of local treatment” alongside the potential for enhanced survival when making treatment decisions in the setting of advanced prostate cancer, the authors explained. Careful informed decision-making by both patients and practitioners is especially important because “there are currently no established guidelines regarding the use of local treatment among men with advanced prostate cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Saira Khan, PhD, MPH, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective design. Men who received local treatment were, on average, younger; older or lesser healthy patients who received local treatment may experience worse adverse effects than observed in the study. The study was limited to US veterans.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a grant from the US Department of Defense. The authors have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

Recent evidence suggested that in men with advanced prostate cancer, local therapy with radical prostatectomy or radiation may improve survival outcomes; however, data on the long-term side effects from these local options were limited.

The retrospective cohort included 5502 men (mean age, 68 years) diagnosed with advanced (T4, N1, and/or M1) prostate cancer.

A total of 1705 men (31%) received initial local treatment, consisting of radical prostatectomy, (55%), radiation (39%), or both (5.6%), while 3797 (69%) opted for initial nonlocal treatment (hormone therapy, chemotherapy, or both).

The main outcomes were treatment-related adverse effects, including GI, chronic pain, sexual dysfunction, and urinary symptoms, assessed at three timepoints after initial treatment — up to 1 year, between 1 and 2 years, and between 2 and 5 years.

TAKEAWAY:

Overall, 916 men (75%) who had initial local treatment and 897 men (67%) with initial nonlocal therapy reported at least one adverse condition up to 5 years after initial treatment.

In the first year after initial treatment, local therapy was associated with a higher prevalence of GI (9% vs 3%), pain (60% vs 38%), sexual (37% vs 8%), and urinary (46.5% vs 18%) conditions. Men receiving local therapy were more likely to experience GI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.08), pain (aOR, 1.57), sexual (aOR, 2.96), and urinary (aOR, 2.25) conditions.

Between 2 and 5 years after local therapy, certain conditions remained more prevalent — 7.8% vs 4.2% for GI, 40% vs 13% for sexual, and 40.5% vs 26% for urinary issues. Men receiving local vs nonlocal therapy were more likely to experience GI (aOR, 2.39), sexual (aOR, 3.36), and urinary (aOR, 1.39) issues over the long term.

The researchers found no difference in the prevalence of constitutional conditions such as hot flashes (36.5% vs 34.4%) in the first year following initial local or nonlocal therapy. However, local treatment followed by any secondary treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of developing constitutional conditions at 1-2 years (aOR, 1.50) and 2-5 years (aOR, 1.78) after initial treatment.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results suggest that patients and clinicians should consider the adverse effects of local treatment” alongside the potential for enhanced survival when making treatment decisions in the setting of advanced prostate cancer, the authors explained. Careful informed decision-making by both patients and practitioners is especially important because “there are currently no established guidelines regarding the use of local treatment among men with advanced prostate cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Saira Khan, PhD, MPH, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective design. Men who received local treatment were, on average, younger; older or lesser healthy patients who received local treatment may experience worse adverse effects than observed in the study. The study was limited to US veterans.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a grant from the US Department of Defense. The authors have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

TOPLINE:

METHODOLOGY:

Recent evidence suggested that in men with advanced prostate cancer, local therapy with radical prostatectomy or radiation may improve survival outcomes; however, data on the long-term side effects from these local options were limited.

The retrospective cohort included 5502 men (mean age, 68 years) diagnosed with advanced (T4, N1, and/or M1) prostate cancer.

A total of 1705 men (31%) received initial local treatment, consisting of radical prostatectomy, (55%), radiation (39%), or both (5.6%), while 3797 (69%) opted for initial nonlocal treatment (hormone therapy, chemotherapy, or both).

The main outcomes were treatment-related adverse effects, including GI, chronic pain, sexual dysfunction, and urinary symptoms, assessed at three timepoints after initial treatment — up to 1 year, between 1 and 2 years, and between 2 and 5 years.

TAKEAWAY:

Overall, 916 men (75%) who had initial local treatment and 897 men (67%) with initial nonlocal therapy reported at least one adverse condition up to 5 years after initial treatment.

In the first year after initial treatment, local therapy was associated with a higher prevalence of GI (9% vs 3%), pain (60% vs 38%), sexual (37% vs 8%), and urinary (46.5% vs 18%) conditions. Men receiving local therapy were more likely to experience GI (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 4.08), pain (aOR, 1.57), sexual (aOR, 2.96), and urinary (aOR, 2.25) conditions.

Between 2 and 5 years after local therapy, certain conditions remained more prevalent — 7.8% vs 4.2% for GI, 40% vs 13% for sexual, and 40.5% vs 26% for urinary issues. Men receiving local vs nonlocal therapy were more likely to experience GI (aOR, 2.39), sexual (aOR, 3.36), and urinary (aOR, 1.39) issues over the long term.

The researchers found no difference in the prevalence of constitutional conditions such as hot flashes (36.5% vs 34.4%) in the first year following initial local or nonlocal therapy. However, local treatment followed by any secondary treatment was associated with a higher likelihood of developing constitutional conditions at 1-2 years (aOR, 1.50) and 2-5 years (aOR, 1.78) after initial treatment.

IN PRACTICE:

“These results suggest that patients and clinicians should consider the adverse effects of local treatment” alongside the potential for enhanced survival when making treatment decisions in the setting of advanced prostate cancer, the authors explained. Careful informed decision-making by both patients and practitioners is especially important because “there are currently no established guidelines regarding the use of local treatment among men with advanced prostate cancer.”

SOURCE:

The study, with first author Saira Khan, PhD, MPH, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri, was published online in JAMA Network Open.

LIMITATIONS:

The authors noted that the study was limited by its retrospective design. Men who received local treatment were, on average, younger; older or lesser healthy patients who received local treatment may experience worse adverse effects than observed in the study. The study was limited to US veterans.

DISCLOSURES:

The study was supported by a grant from the US Department of Defense. The authors have no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Rebranding NAFLD: Correcting ‘Flawed’ Conventions

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) should now be referred to as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), according to a recent commentary by leading hepatologists.

This update, which was determined by a panel of 236 panelists from 56 countries, is part of a broader effort to rebrand “fatty liver disease” as “steatotic liver disease” (SLD), reported lead author Alina M. Allen, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and colleagues.

Writing in Gastroenterology, they described a range of reasons for the nomenclature changes, from the need for better characterization of disease subtypes, to the concern that the term “fatty” may be perceived as stigmatizing by some patients.

“The scientific community and stakeholder organizations associated with liver diseases determined there was a need for new terminology to cover liver disease related to alcohol alone, metabolic risk factors (until recently termed NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH]) alone, the combination of alcohol and metabolic risk factors, and hepatic steatosis due to other specific etiologies,” the authors wrote.

Naming conventions in this area have been flawed since inception, Dr. Allen and colleagues wrote, noting that “nonalcoholic” is exclusionary rather than descriptive, and is particularly misplaced in the pediatric setting. These shortcomings could explain why the term “NASH” took more than a decade to enter common usage, they suggested, and why the present effort is not the first of its kind.

“There have been several movements to change the nomenclature [of NAFLD], including most recently to ‘metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease’ (MAFLD), a term that received limited traction,” the authors wrote.

Still, a change is needed, they added, as metabolic dysfunction is becoming increasingly common on a global scale, driving up rates of liver disease. Furthermore, in some patients, alcohol consumption and metabolic factors concurrently drive steatosis, suggesting an intermediate condition between alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) and NAFLD that is indescribable via current naming conventions.

SLD (determined by imaging or biopsy) now comprises five disease subtypes that can be determined via an algorithm provided in the present publication.

If at least one metabolic criterion is present, but no other causes of steatosis, then that patient has MASLD. The three other metabolic subtypes include MetALD (2-3 drinks per day for women and 3-4 drinks per day for men), ALD (more than 3 drinks per day for women and more than 4 drinks per day for men), and monogenic miscellaneous drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

Patients without metabolic criteria can also be classified with monogenic miscellaneous DILI with no caveat, whereas patients with metabolic criteria need only consume 2 or 3 drinks per day for women or 3-4 drinks per day for men, respectively, to be diagnosed with ALD.

Finally, patients with no metabolic criteria or other cause of steatosis should be characterized by cryptogenic SLD.

“While renaming and redefining the disease was needed, the implementation is not without challenges,” Dr. Allen and colleagues wrote. “A more complex classification may add confusion in the mind of nonhepatology providers when awareness and understanding of the implications of SLD are already suboptimal.”

Still, they predicted that the new naming system could lead to several positive outcomes, including improved SLD screening among individuals with metabolic risk factors, more accurate phenotyping of patients with moderate alcohol consumption, increased disease awareness in nonhepatology practices, and improved multidisciplinary collaboration.

Only time will tell whether these benefits come to fruition, Dr. Allen and colleagues noted, before closing with a quote: “In the words of Jean Piaget, the developmental psychologist of the 20th century, who coincidentally died the year the term NASH was coined, ‘Scientific knowledge is in perpetual evolution; it finds itself changed from one day to the next.’”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) should now be referred to as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), according to a recent commentary by leading hepatologists.

This update, which was determined by a panel of 236 panelists from 56 countries, is part of a broader effort to rebrand “fatty liver disease” as “steatotic liver disease” (SLD), reported lead author Alina M. Allen, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and colleagues.

Writing in Gastroenterology, they described a range of reasons for the nomenclature changes, from the need for better characterization of disease subtypes, to the concern that the term “fatty” may be perceived as stigmatizing by some patients.

“The scientific community and stakeholder organizations associated with liver diseases determined there was a need for new terminology to cover liver disease related to alcohol alone, metabolic risk factors (until recently termed NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH]) alone, the combination of alcohol and metabolic risk factors, and hepatic steatosis due to other specific etiologies,” the authors wrote.

Naming conventions in this area have been flawed since inception, Dr. Allen and colleagues wrote, noting that “nonalcoholic” is exclusionary rather than descriptive, and is particularly misplaced in the pediatric setting. These shortcomings could explain why the term “NASH” took more than a decade to enter common usage, they suggested, and why the present effort is not the first of its kind.

“There have been several movements to change the nomenclature [of NAFLD], including most recently to ‘metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease’ (MAFLD), a term that received limited traction,” the authors wrote.

Still, a change is needed, they added, as metabolic dysfunction is becoming increasingly common on a global scale, driving up rates of liver disease. Furthermore, in some patients, alcohol consumption and metabolic factors concurrently drive steatosis, suggesting an intermediate condition between alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) and NAFLD that is indescribable via current naming conventions.

SLD (determined by imaging or biopsy) now comprises five disease subtypes that can be determined via an algorithm provided in the present publication.

If at least one metabolic criterion is present, but no other causes of steatosis, then that patient has MASLD. The three other metabolic subtypes include MetALD (2-3 drinks per day for women and 3-4 drinks per day for men), ALD (more than 3 drinks per day for women and more than 4 drinks per day for men), and monogenic miscellaneous drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

Patients without metabolic criteria can also be classified with monogenic miscellaneous DILI with no caveat, whereas patients with metabolic criteria need only consume 2 or 3 drinks per day for women or 3-4 drinks per day for men, respectively, to be diagnosed with ALD.

Finally, patients with no metabolic criteria or other cause of steatosis should be characterized by cryptogenic SLD.

“While renaming and redefining the disease was needed, the implementation is not without challenges,” Dr. Allen and colleagues wrote. “A more complex classification may add confusion in the mind of nonhepatology providers when awareness and understanding of the implications of SLD are already suboptimal.”

Still, they predicted that the new naming system could lead to several positive outcomes, including improved SLD screening among individuals with metabolic risk factors, more accurate phenotyping of patients with moderate alcohol consumption, increased disease awareness in nonhepatology practices, and improved multidisciplinary collaboration.

Only time will tell whether these benefits come to fruition, Dr. Allen and colleagues noted, before closing with a quote: “In the words of Jean Piaget, the developmental psychologist of the 20th century, who coincidentally died the year the term NASH was coined, ‘Scientific knowledge is in perpetual evolution; it finds itself changed from one day to the next.’”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) should now be referred to as metabolic dysfunction–associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD), according to a recent commentary by leading hepatologists.

This update, which was determined by a panel of 236 panelists from 56 countries, is part of a broader effort to rebrand “fatty liver disease” as “steatotic liver disease” (SLD), reported lead author Alina M. Allen, MD, of Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, and colleagues.

Writing in Gastroenterology, they described a range of reasons for the nomenclature changes, from the need for better characterization of disease subtypes, to the concern that the term “fatty” may be perceived as stigmatizing by some patients.

“The scientific community and stakeholder organizations associated with liver diseases determined there was a need for new terminology to cover liver disease related to alcohol alone, metabolic risk factors (until recently termed NAFLD/nonalcoholic steatohepatitis [NASH]) alone, the combination of alcohol and metabolic risk factors, and hepatic steatosis due to other specific etiologies,” the authors wrote.

Naming conventions in this area have been flawed since inception, Dr. Allen and colleagues wrote, noting that “nonalcoholic” is exclusionary rather than descriptive, and is particularly misplaced in the pediatric setting. These shortcomings could explain why the term “NASH” took more than a decade to enter common usage, they suggested, and why the present effort is not the first of its kind.

“There have been several movements to change the nomenclature [of NAFLD], including most recently to ‘metabolic dysfunction–associated fatty liver disease’ (MAFLD), a term that received limited traction,” the authors wrote.

Still, a change is needed, they added, as metabolic dysfunction is becoming increasingly common on a global scale, driving up rates of liver disease. Furthermore, in some patients, alcohol consumption and metabolic factors concurrently drive steatosis, suggesting an intermediate condition between alcohol-related liver disease (ALD) and NAFLD that is indescribable via current naming conventions.

SLD (determined by imaging or biopsy) now comprises five disease subtypes that can be determined via an algorithm provided in the present publication.

If at least one metabolic criterion is present, but no other causes of steatosis, then that patient has MASLD. The three other metabolic subtypes include MetALD (2-3 drinks per day for women and 3-4 drinks per day for men), ALD (more than 3 drinks per day for women and more than 4 drinks per day for men), and monogenic miscellaneous drug-induced liver injury (DILI).

Patients without metabolic criteria can also be classified with monogenic miscellaneous DILI with no caveat, whereas patients with metabolic criteria need only consume 2 or 3 drinks per day for women or 3-4 drinks per day for men, respectively, to be diagnosed with ALD.

Finally, patients with no metabolic criteria or other cause of steatosis should be characterized by cryptogenic SLD.

“While renaming and redefining the disease was needed, the implementation is not without challenges,” Dr. Allen and colleagues wrote. “A more complex classification may add confusion in the mind of nonhepatology providers when awareness and understanding of the implications of SLD are already suboptimal.”

Still, they predicted that the new naming system could lead to several positive outcomes, including improved SLD screening among individuals with metabolic risk factors, more accurate phenotyping of patients with moderate alcohol consumption, increased disease awareness in nonhepatology practices, and improved multidisciplinary collaboration.

Only time will tell whether these benefits come to fruition, Dr. Allen and colleagues noted, before closing with a quote: “In the words of Jean Piaget, the developmental psychologist of the 20th century, who coincidentally died the year the term NASH was coined, ‘Scientific knowledge is in perpetual evolution; it finds itself changed from one day to the next.’”

The authors disclosed no conflicts of interest.

FROM GASTROENTEROLOGY

Zoom: Convenient and Imperfect

Making eye contact is important in human interactions. It shows attention and comprehension. It also helps us read the nuances of another’s facial expressions when interacting.

Although the idea of video phone calls isn’t new — I remember it from my childhood in “house of the future” TV shows — it certainly didn’t take off until the advent of high-speed Internet, computers, and phones with cameras. Then Facetime, Skype, Zoom, Teams, and others.

Of course, it all still took a back seat to actually seeing people and having meetings in person. Until the pandemic made that the least attractive option. Then the adoption of such things went into hyperdrive and has stayed there ever since.