User login

Status Epilepticus in Pregnancy

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

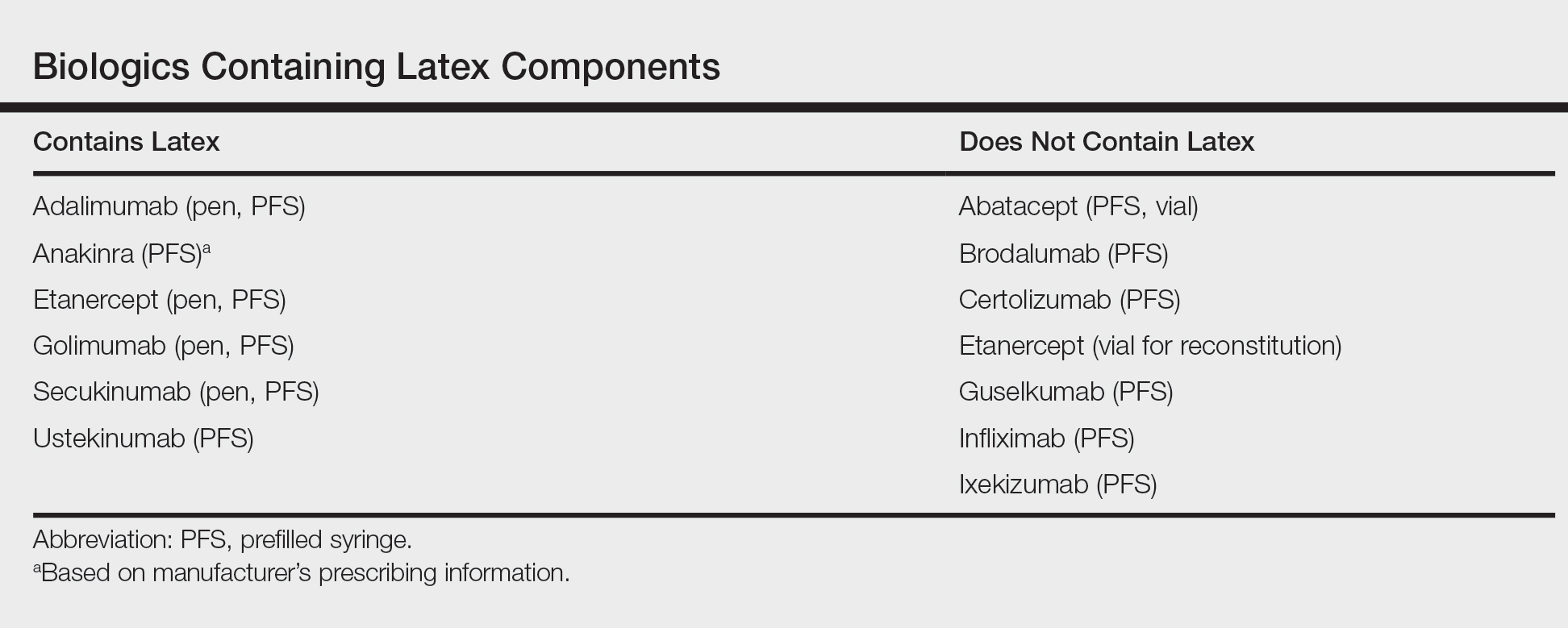

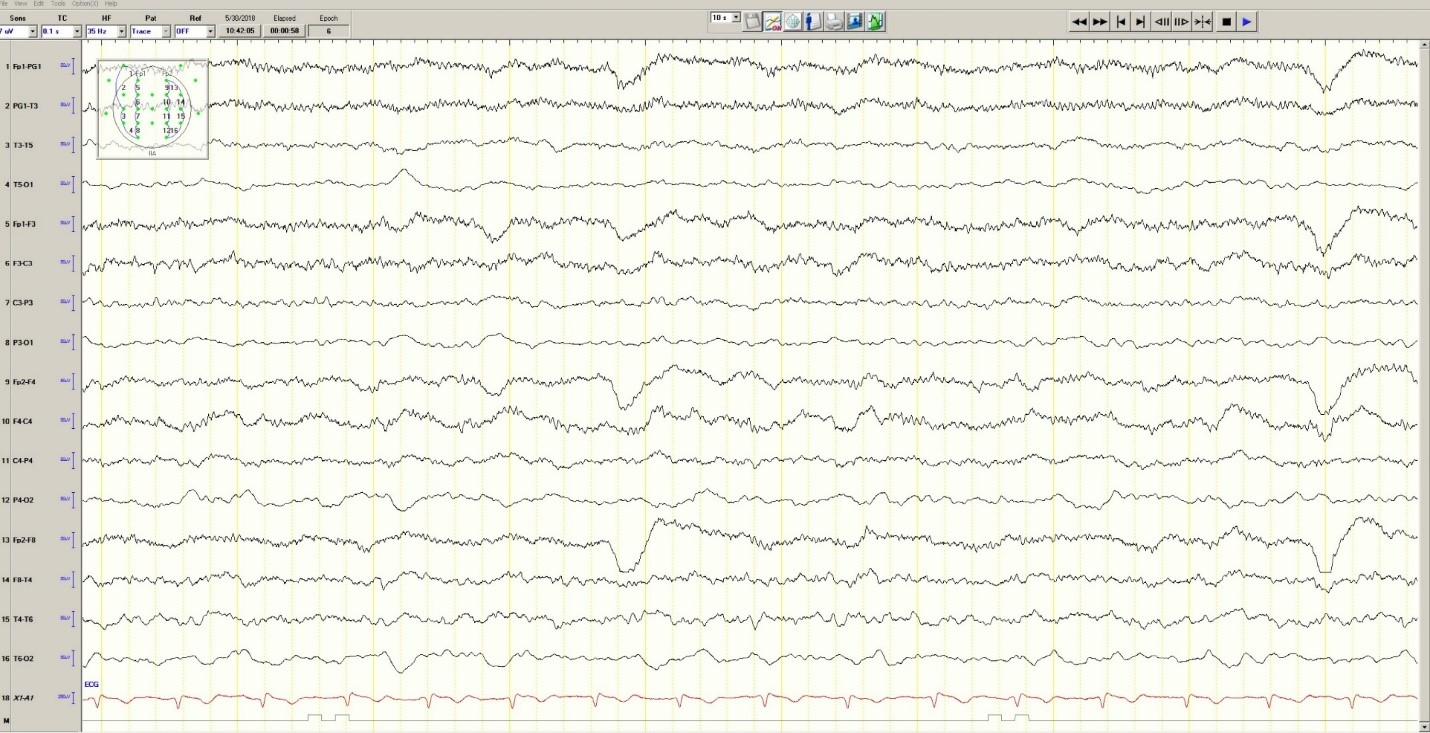

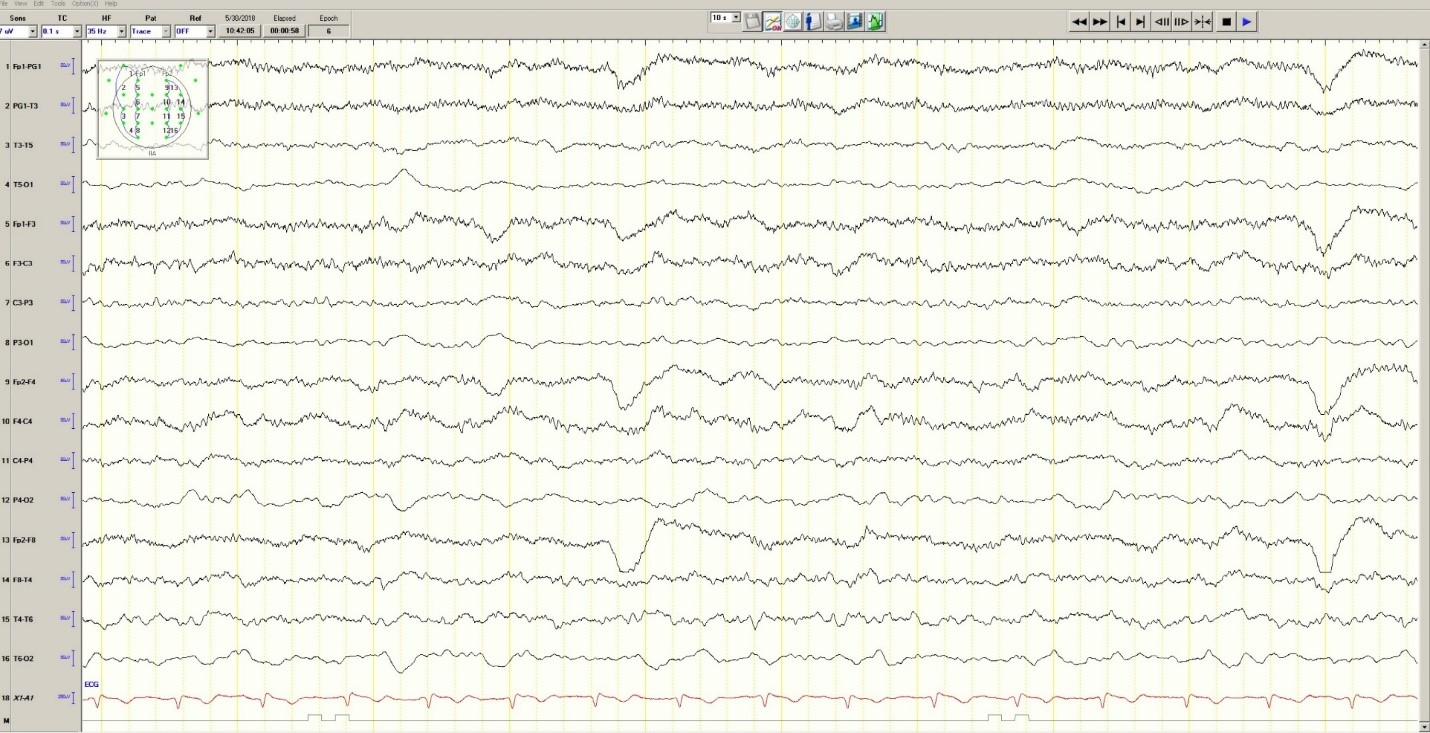

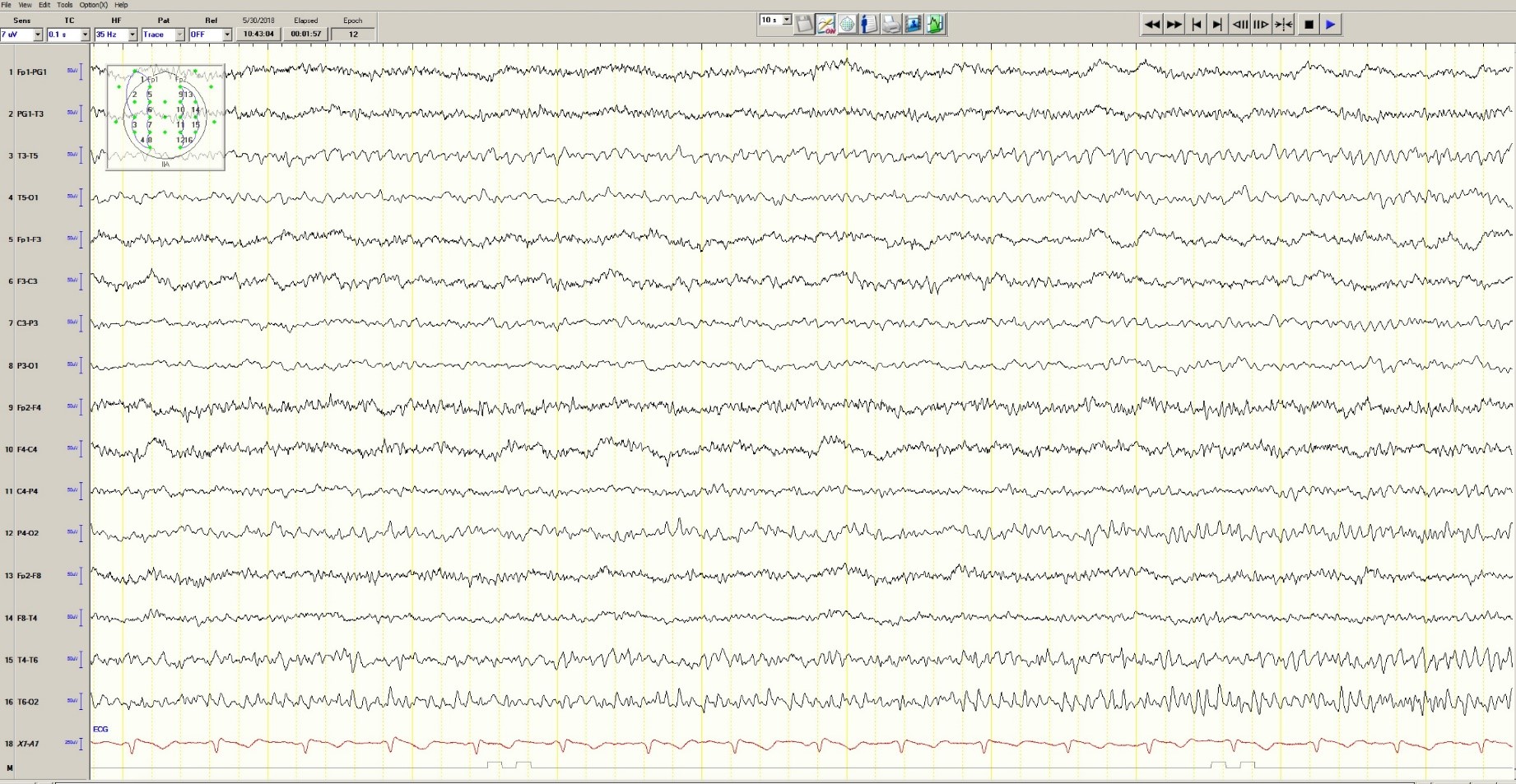

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

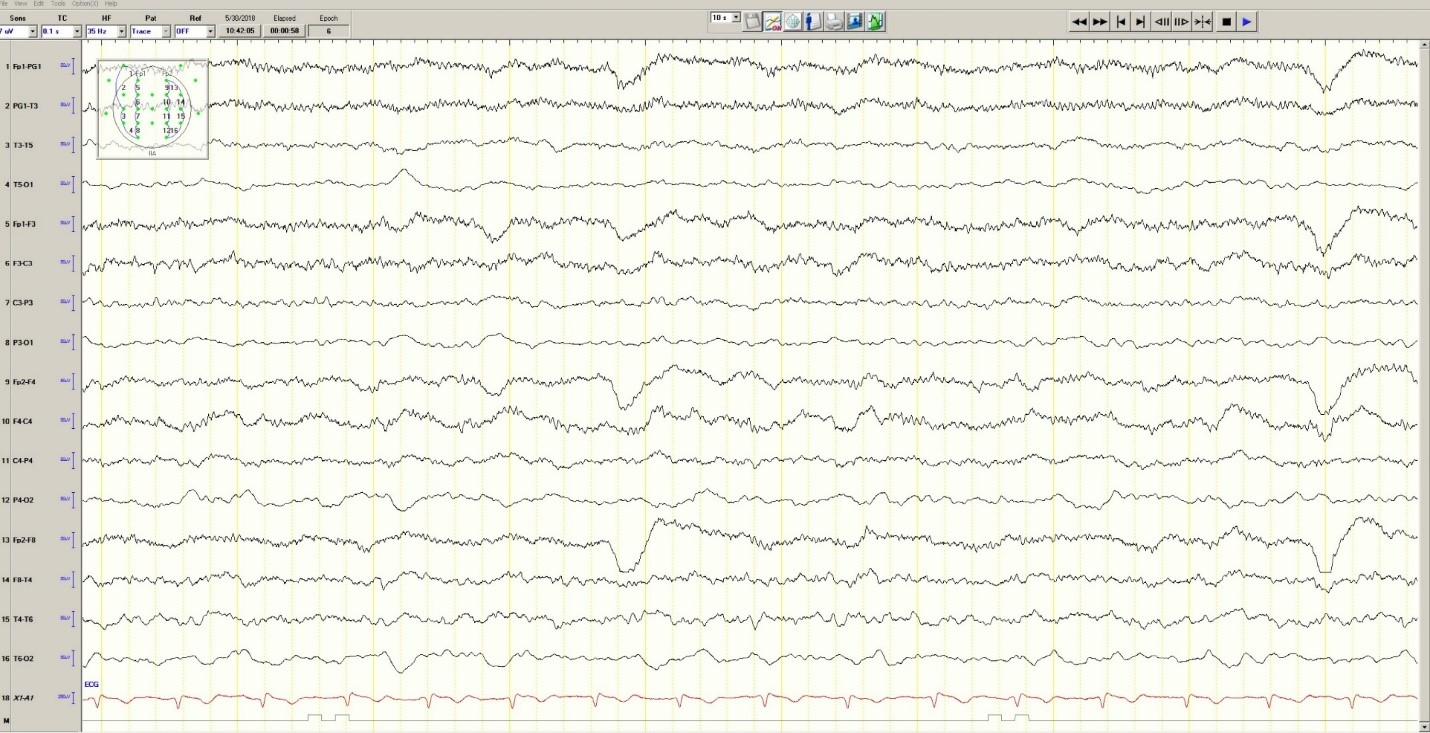

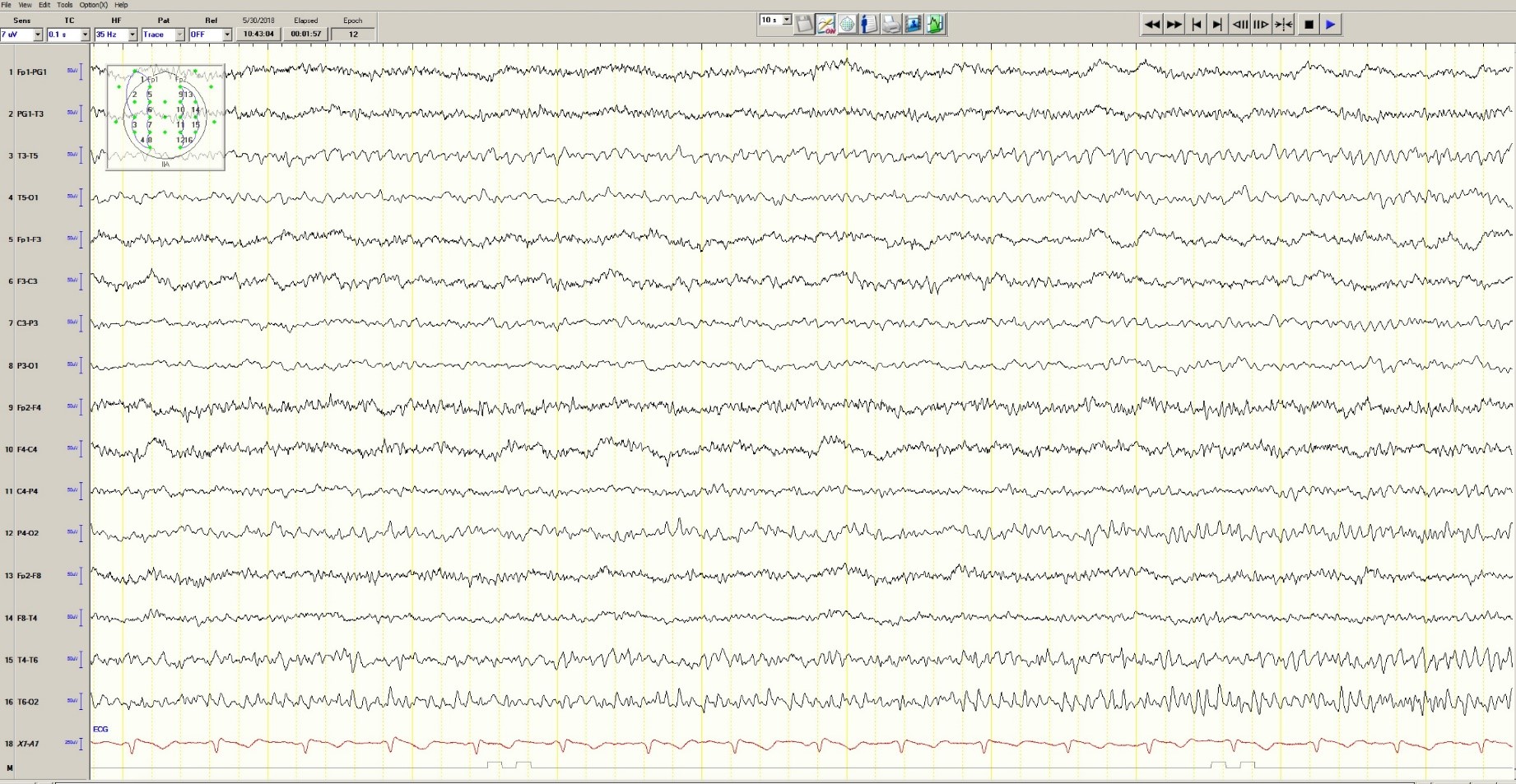

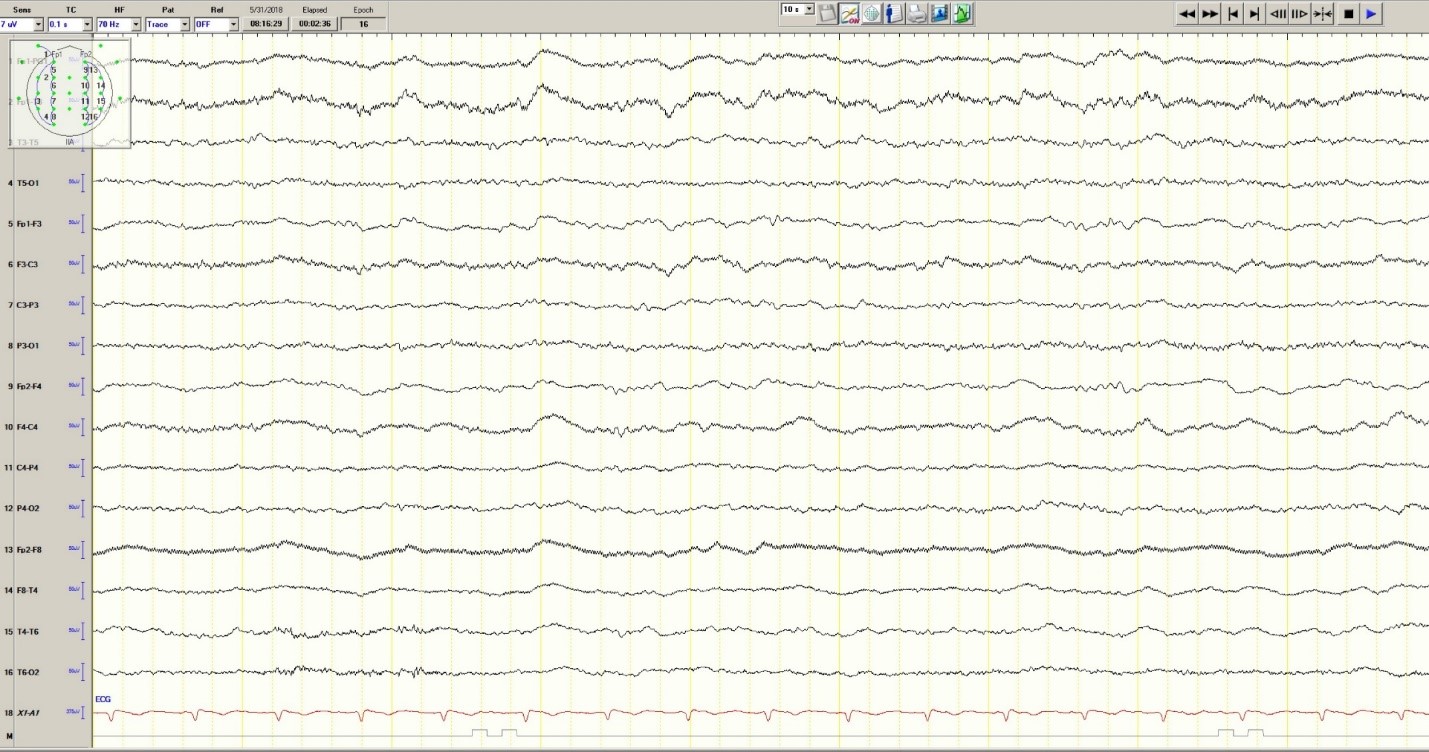

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

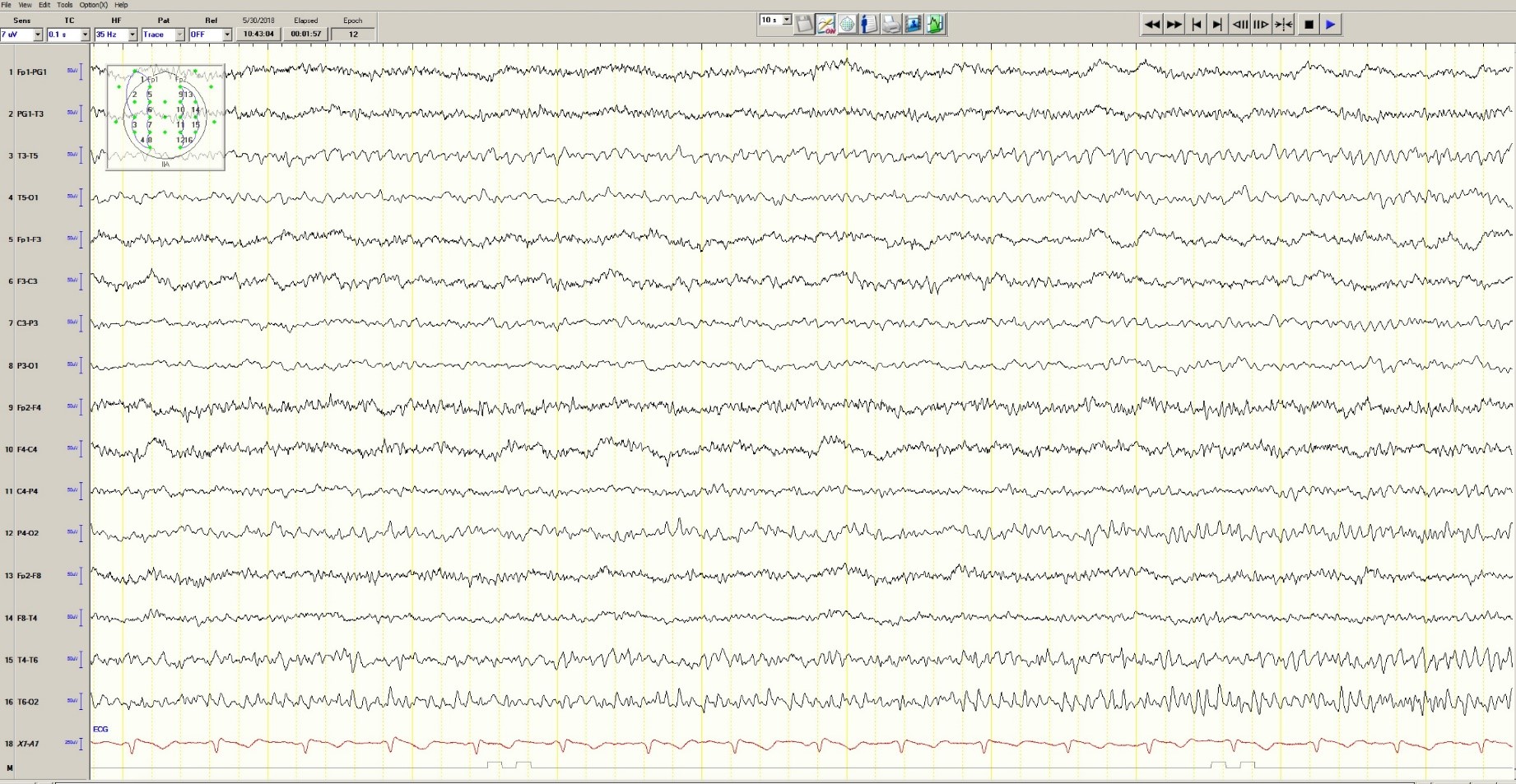

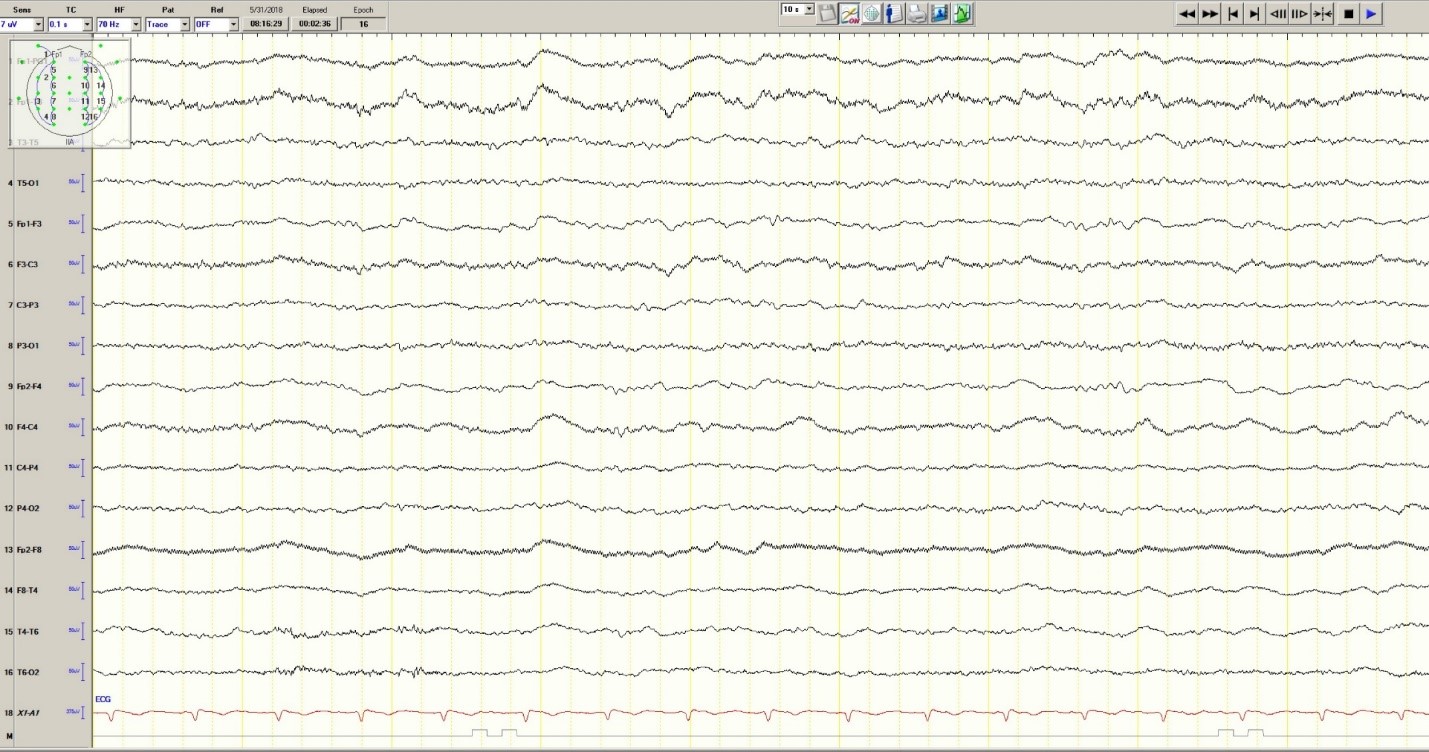

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD, FAAN, FACP

Angels Neurological Centers

Abington, MA

Clinical History

A 37-year-old pregnant African American woman with a history of epilepsy and polysubstance abuse was found unresponsive in a hotel room. She had four convulsions en route to the hospital. In transit, she received levetiracetam and phenytoin, resulting in the cessation of the clinical seizures.

According to her mother, seizures began at age 16 during her first pregnancy, which was complicated by hypertension. She was prescribed medications for hypertension and phenytoin for seizures. The patient provided a different history, claiming that her seizures began 2 years ago. She denied taking medication for seizures or other health problems.

The patient has two children, ages 22 and 11 years. Past medical history is otherwise unremarkable. She has no allergies. Social history includes cigarette smoking, and alcohol and substance abuse. She lives with her boyfriend and does not work. She is 25 weeks pregnant. Family history was notable only for migraine in her mother and grandmother.

Physical Examination

In the emergency department, blood pressure was 135/65, pulse 121 beats per minute, and oxygen saturation was 97%. She was oriented only to self and did not follow commands. Pupils were equal and reactive. There was no facial asymmetry. She moved all 4 extremities spontaneously. Reflexes were brisk. Oral mucosa was dry. She had no edema in the lower extremities.

Laboratories

Chest x-ray was normal. EKG revealed tachycardia and nonspecific ST changes. Hemoglobin was 11.1 g/dl, hematocrit 32%, white blood cell count 10,900, and platelets 181,000. Electrolytes were normal except for a low sodium of 132 mmol/l (135-145) and bicarbonate of 17 mmol/l (21-31). Glucose was initially 67 mg/dl and dropped to 46 mg/dl. Total protein was 6 g/dl (6.7-8.2) and albumin was 2.7 g/dl (3.2-5.5). Metabolic panel was otherwise normal. Urinalysis was positive for glucose, ketones, and a small amount of blood and protein. There were no bacteria. Blood and urine cultures were negative. Phenytoin level was undetectable. Urine drug screen was positive for cannabinoids and cocaine.

Hospital Course

Hypoglycemia was treated with an ampule of D50 and intravenous fluids. On the obstetrics ward, nurses observed several episodes of head and eye deviation to the right accompanied by decreased responsiveness that lasted approximately 30 seconds. The patient was sent to the electrophysiology lab where an EEG revealed a diffusely slow background (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Generalized Slowing

During the 20-minute EEG recording, the patient had six clinical seizures similar to those described by the nurses. These events correlated with an ictal pattern consisting of 11 HZ_sharp activity in the right occipital temporal region that spread to the right parietal and left occipital temporal regions (Figure 2). Head CT revealed mild generalized atrophy and an enlarged right occipital horn, but no acute lesions (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Partial seizure originating in right occipital temporal region

Figure 3. Mild generalized arophy, greater in right hemisphere

The patient was transferred to intensive care and received fosphenytoin. No further clinical and /or electrographic seizures were identified. The following day, an EEG revealed diffuse slowing without focal seizures (Figure 4). The patient gradually became more alert and cooperative over the next 24 hours. However, the next day no fetal heartbeat was detected. Labor was induced and a stillborn baby delivered. The pathology report indicated that the placenta was between the 5th and 10th percentile for gestational age.

Figure 4. Improved generalized slowing

Discussion

Status epilepticus is associated with significant morbidity and mortality (Claassen et al. 2002). This 37-year-old pregnant woman had an episode of focal status epilepticus with impaired awareness likely provoked by nonadherence to antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). Cocaine may have contributed to the episode of status epilepticus (Majlesi et al. 2010). The obstetric service did not diagnose preeclampsia.

The patient’s seizures started in the right occipital region, which was abnormal on neuroimaging. An MRI might have revealed more subtle structural abnormalities such as cortical dysplasia as the etiology of her epilepsy, but she refused the scan.

Women with epilepsy are at increased risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes such as preeclampsia, preterm labor, and stillbirth and should be considered high risk (MacDonald et al. 2015). Serum levels of AEDs such as lamotrigine, levetiracetam and phenytoin may decrease during pregnancy and contribute to breakthrough seizures. Accordingly, monthly measurements of serum levels of AEDs during the entire course of the pregnancy are strongly recommended. These measurements allow for a timely adjustment of AED doses to prevent significant drop in their serum concentrations and minimize the occurrence of breakthrough seizures. In the case of phenytoin, measurement of free and total serum concentrations are recommended. Supplementation with at least 0.4 mg/day to 1 mg /day of folic acid (and up to 4 mg /day) has been recommended (Harden et al. 2009a). Of note, there is no increase in the incidence of status epilepticus due to pregnancy per se (Harden et al. 2009b).

Although the patient survived this episode of status epilepticus, her fetus did not. Antiseizure drug nonadherence and polysubstance abuse probably contributed to fetal demise.

References

Claassen J, Lokin JK, Fitzsimons BFM et al. Predictors of functional disability and mortality after status epilepticus. Neurology. 2002;58:139-142.

Harden CL, Pennell PB, Koppel BS et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy Focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Vitamin K, folic acid, blood levels, and breastfeeding: Neurology 2009a;73:142-149.

Harden CL, Hopp J, Ting TY et al. Practice Parameter update: Management issues for women with epilepsy-focus on pregnancy (an evidence-based review): Obstetrical complications and change in seizure frequency. Neurology 2009b;50(5):1229-36.

MacDonald SC, Bateman BT, McElrath TF, Hernandez-Diaz S. Mortality and morbidity during delivery hospitalization among pregnant women with epilepsy in the United States. JAMA Neurol. 2015;72(9):981-988.

Majlesi N, Shih R, Fiesseler FW et al. Cocaine-associated seizures and incidence of status epilepticus. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2010;XI(2):157-160.

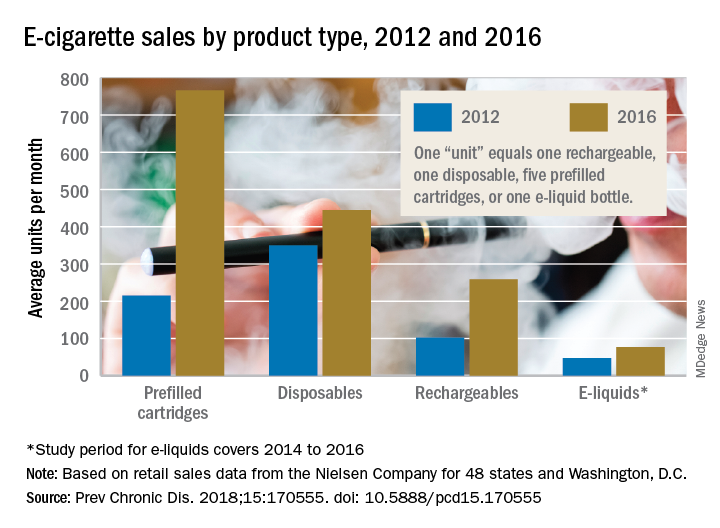

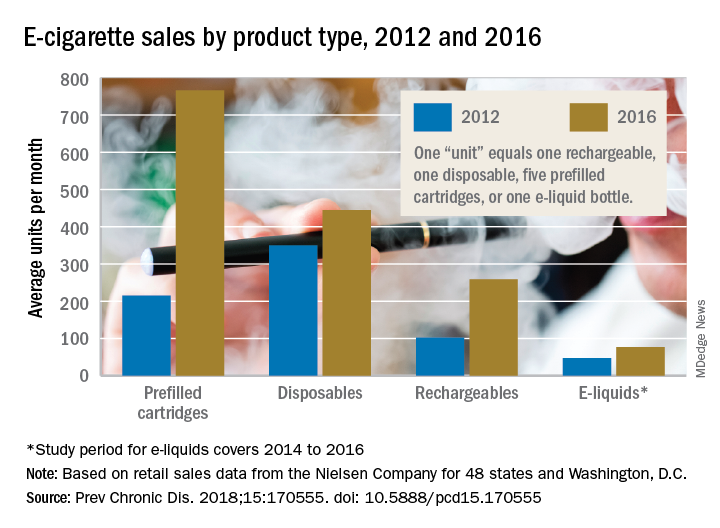

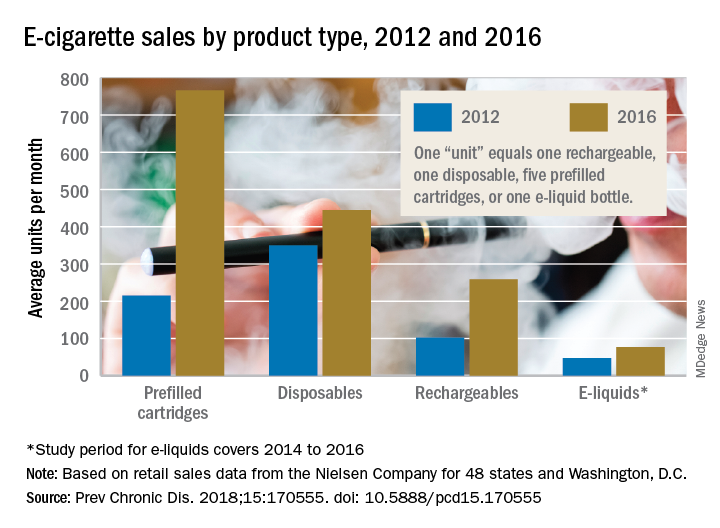

E-cigarettes: Prices down, sales up

Any economist could have predicted it: As the .

The average prices of three mutually exclusive e-cigarette products – rechargeable devices, disposable devices, and disposable cartridges filled with e-liquid – all dropped from 2012 to 2016, as did that of a fourth product – e-liquid bottles for filling reusable cartridges – not available nationwide until 2014. At the same time, average monthly sales for e-cigarette products overall rose by a statistically significant 132%, Teresa W. Wang, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates reported in Preventing Chronic Disease.

Sales of prefilled cartridges, the most popular product by the end of the study period, increased 256%, going from 215 units per 100,000 people each month in 2012 to 766 units. [For the study, a unit was defined as one rechargeable, one disposable, one pack of five prefilled cartridges, or one bottle of e-liquid.] Disposables were the most popular product at the start of the study period but had the smallest relative increase (27%), while monthly sales of rechargeables jumped by 154% and e-liquids saw a 64% rise, the investigators said.

Price decreases for the three products available in 2012 were all significant: The average price per unit was down 48% for rechargeables by 2016, 14% for disposables, and 12% for prefilled cartridges. E-liquids were 9% cheaper by 2016, but that change did not reach significance, they noted.

“Overall, the increase in e-cigarette sales and decrease in price is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that e-cigarette sales are responsive to their own price changes. These trends suggest that, if e-cigarette prices continue to decrease, their sales may also continue to rise,” Dr. Wang and her associates wrote.

The data for the study came from the Nielsen Company and were based on retail sales at convenience stores; supermarkets; drug, dollar, and club stores; and military commissaries in the 48 contiguous states and Washington, D.C. One study limitation was the lack of data from tobacco/vape shops and the Internet.

SOURCE: Wang TW et al. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:170555. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170555.

Any economist could have predicted it: As the .

The average prices of three mutually exclusive e-cigarette products – rechargeable devices, disposable devices, and disposable cartridges filled with e-liquid – all dropped from 2012 to 2016, as did that of a fourth product – e-liquid bottles for filling reusable cartridges – not available nationwide until 2014. At the same time, average monthly sales for e-cigarette products overall rose by a statistically significant 132%, Teresa W. Wang, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates reported in Preventing Chronic Disease.

Sales of prefilled cartridges, the most popular product by the end of the study period, increased 256%, going from 215 units per 100,000 people each month in 2012 to 766 units. [For the study, a unit was defined as one rechargeable, one disposable, one pack of five prefilled cartridges, or one bottle of e-liquid.] Disposables were the most popular product at the start of the study period but had the smallest relative increase (27%), while monthly sales of rechargeables jumped by 154% and e-liquids saw a 64% rise, the investigators said.

Price decreases for the three products available in 2012 were all significant: The average price per unit was down 48% for rechargeables by 2016, 14% for disposables, and 12% for prefilled cartridges. E-liquids were 9% cheaper by 2016, but that change did not reach significance, they noted.

“Overall, the increase in e-cigarette sales and decrease in price is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that e-cigarette sales are responsive to their own price changes. These trends suggest that, if e-cigarette prices continue to decrease, their sales may also continue to rise,” Dr. Wang and her associates wrote.

The data for the study came from the Nielsen Company and were based on retail sales at convenience stores; supermarkets; drug, dollar, and club stores; and military commissaries in the 48 contiguous states and Washington, D.C. One study limitation was the lack of data from tobacco/vape shops and the Internet.

SOURCE: Wang TW et al. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:170555. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170555.

Any economist could have predicted it: As the .

The average prices of three mutually exclusive e-cigarette products – rechargeable devices, disposable devices, and disposable cartridges filled with e-liquid – all dropped from 2012 to 2016, as did that of a fourth product – e-liquid bottles for filling reusable cartridges – not available nationwide until 2014. At the same time, average monthly sales for e-cigarette products overall rose by a statistically significant 132%, Teresa W. Wang, PhD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, and her associates reported in Preventing Chronic Disease.

Sales of prefilled cartridges, the most popular product by the end of the study period, increased 256%, going from 215 units per 100,000 people each month in 2012 to 766 units. [For the study, a unit was defined as one rechargeable, one disposable, one pack of five prefilled cartridges, or one bottle of e-liquid.] Disposables were the most popular product at the start of the study period but had the smallest relative increase (27%), while monthly sales of rechargeables jumped by 154% and e-liquids saw a 64% rise, the investigators said.

Price decreases for the three products available in 2012 were all significant: The average price per unit was down 48% for rechargeables by 2016, 14% for disposables, and 12% for prefilled cartridges. E-liquids were 9% cheaper by 2016, but that change did not reach significance, they noted.

“Overall, the increase in e-cigarette sales and decrease in price is consistent with previous studies demonstrating that e-cigarette sales are responsive to their own price changes. These trends suggest that, if e-cigarette prices continue to decrease, their sales may also continue to rise,” Dr. Wang and her associates wrote.

The data for the study came from the Nielsen Company and were based on retail sales at convenience stores; supermarkets; drug, dollar, and club stores; and military commissaries in the 48 contiguous states and Washington, D.C. One study limitation was the lack of data from tobacco/vape shops and the Internet.

SOURCE: Wang TW et al. Prev Chronic Dis. 2018;15:170555. doi: 10.5888/pcd15.170555.

FROM PREVENTING CHRONIC DISEASE

Deer Ked: A Lyme-Carrying Ectoparasite on the Move

How to Prevent Mosquito and Tick-Borne Disease

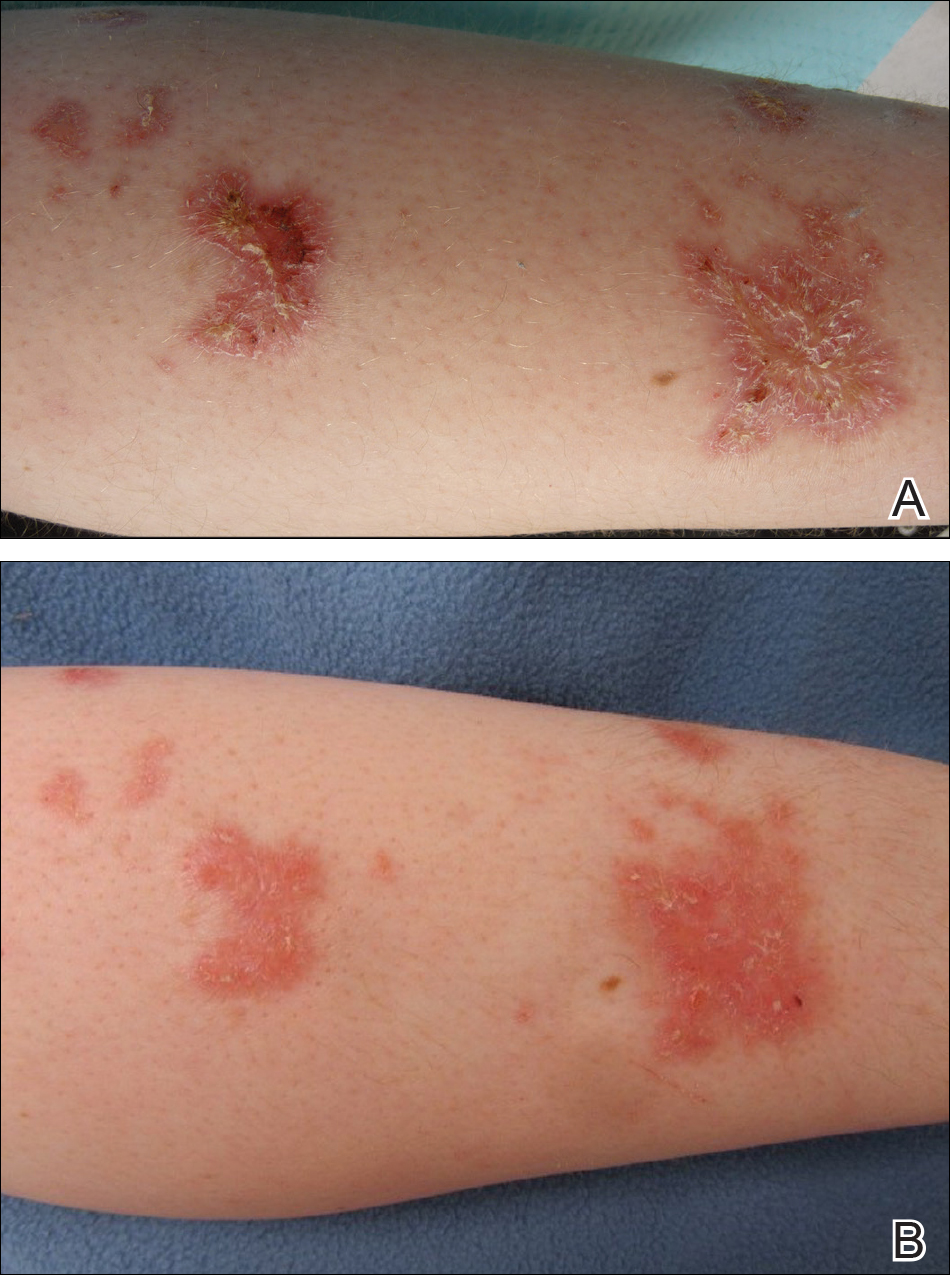

Case Report

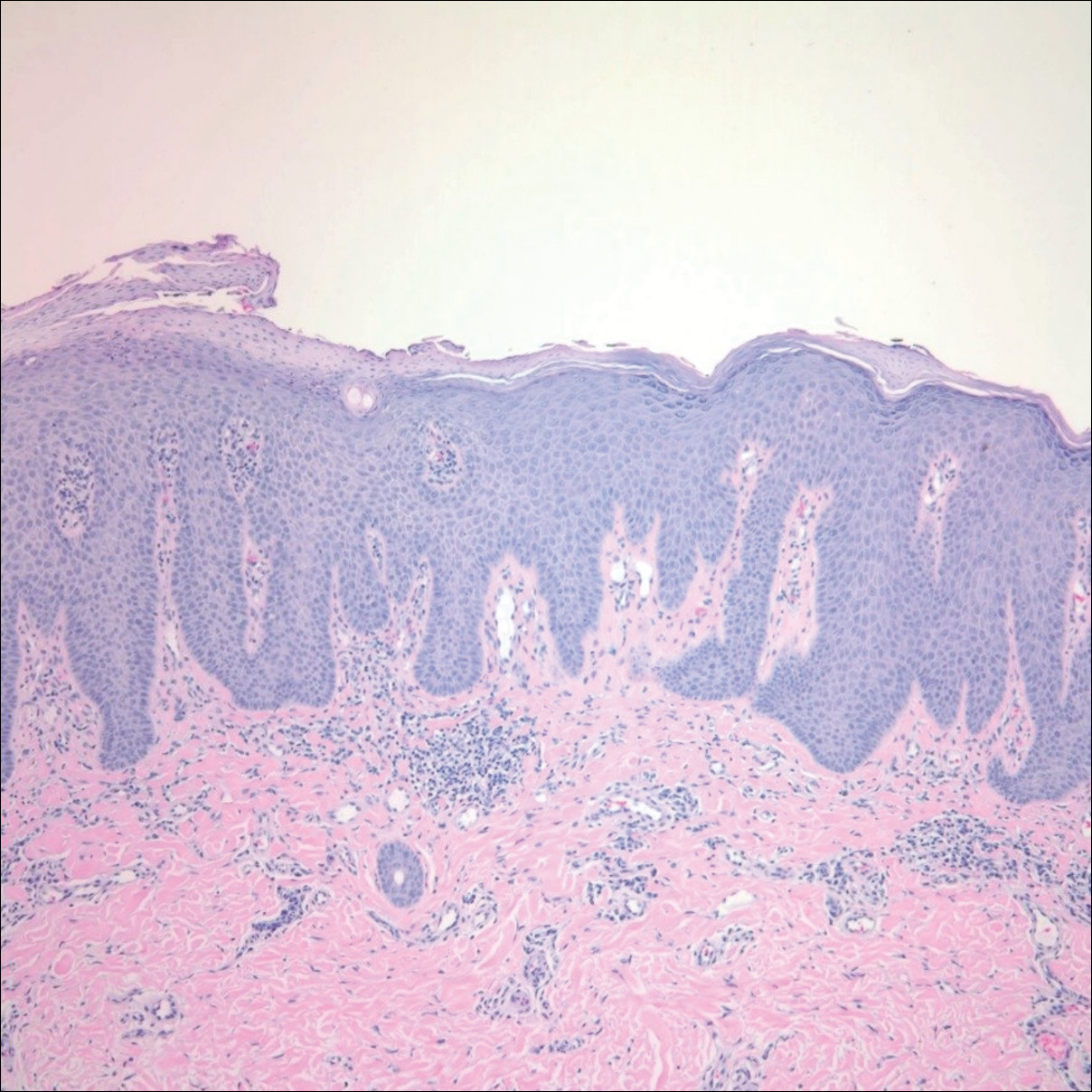

A 31-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic 1 day after mountain biking in the woods in Hartford County, Connecticut. He stated that he found a tick attached to his shirt after riding (Figure). Careful examination of the patient showed no signs of a bite reaction. The insect was identified via microscopy as the deer ked Lipoptena cervi.

Comment

Lipoptena cervi, known as the deer ked, is an ectoparasite of cervids traditionally found in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.1 The deer ked was first reported in American deer in 2 independent sightings in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire in 1907.2 More recently deer keds have been reported in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.3 In the United States, L cervi is thought to be an invasive species transported from Europe in the 1800s.4,5 The main host is thought to be the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus viginianus). Once a suitable host is found, the deer ked sheds its wings and crawls into the fur. After engorging on a blood meal, it deposits prepupae that fall from the host and mature into winged adults during the late summer into the autumn. Adults may exhibit swarming behavior, and it is during this host-seeking activity that they land on humans.3

Following the bite of a deer ked, there are reports of long-lasting dermatitis in both humans and dogs.1,4,6 One case series involving 19 patients following deer ked bites reported pruritic bite papules.4 The reaction appeared to be treatment resistant and lasted from 2 weeks to 12 months. Histologic examination was typical for arthropod assault. Of 11 papules that were biopsied, most (7/11) showed C3 deposition in dermal vessel walls under direct immunofluorescence. Of 19 patients, 57% had elevated serum IgE levels.4

In addition to the associated dermatologic findings, the deer ked is a vector of various infectious agents. Bartonella schoenbuchensis has been isolated from deer ked in Massachusettes.7 A recent study found a 75% prevalence of Bartonella species in 217 deer keds collected from red deer in Poland.5 The first incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophylum in deer keds was reported in the United States in 2016. Of 48 adult deer keds collected from an unknown number of deer, 19 (40%), 14 (29%), and 3 (6%) were positive for B burgdorferi, A phagocytophylum, and both on polymerase chain reaction, respectively.3

A recent study from Europe showed deer keds are now more frequently found in regions where they had not previously been observed.8 It stands to reason that with climate change, L cervi and other disease-carrying vectors are likely to migrate to and inhabit new regions of the country. Even in the current climate, there are more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied in medicine, and all patients who experience an arthropod assault should be monitored for signs of systemic disease.

- Mysterud A, Madslien K, Herland A, et al. Phenology of deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) host-seeking flight activity and its relationship with prevailing autumn weather. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:95.

- Bequaert JC. A Monograph of the Melophaginae or Ked-flies of Sheep, Goats, Deer, and Antelopes (Diptera, Hippoboscidae). Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Entomological Society; 1942.

- Buss M, Case L, Kearney B, et al. Detection of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis pathogens via PCR in Pennsylvania deer ked. J Vector Ecol. 2016;41:292-294.

- Rantanen T, Reunala T, Vuojolahti P, et al. Persistent pruritic papules from deer ked bites. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:307-311.

- Szewczyk T, Werszko J, Steiner-Bogdaszewska Ż, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella spp. in deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:487.

- Hermosilla C, Pantchev N, Bachmann R, et al. Lipoptena cervi (deer ked) in two naturally infested dogs. Vet Rec. 2006;159:286-287.

- Matsumoto K, Berrada ZL, Klinger E, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella schoenbuchensis from ectoparasites of deer in Massachusetts. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:549-554.

- Sokół R, Gałęcki R. Prevalence of keds on city dogs in central Poland. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;31:114-116.

How to Prevent Mosquito and Tick-Borne Disease

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic 1 day after mountain biking in the woods in Hartford County, Connecticut. He stated that he found a tick attached to his shirt after riding (Figure). Careful examination of the patient showed no signs of a bite reaction. The insect was identified via microscopy as the deer ked Lipoptena cervi.

Comment

Lipoptena cervi, known as the deer ked, is an ectoparasite of cervids traditionally found in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.1 The deer ked was first reported in American deer in 2 independent sightings in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire in 1907.2 More recently deer keds have been reported in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.3 In the United States, L cervi is thought to be an invasive species transported from Europe in the 1800s.4,5 The main host is thought to be the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus viginianus). Once a suitable host is found, the deer ked sheds its wings and crawls into the fur. After engorging on a blood meal, it deposits prepupae that fall from the host and mature into winged adults during the late summer into the autumn. Adults may exhibit swarming behavior, and it is during this host-seeking activity that they land on humans.3

Following the bite of a deer ked, there are reports of long-lasting dermatitis in both humans and dogs.1,4,6 One case series involving 19 patients following deer ked bites reported pruritic bite papules.4 The reaction appeared to be treatment resistant and lasted from 2 weeks to 12 months. Histologic examination was typical for arthropod assault. Of 11 papules that were biopsied, most (7/11) showed C3 deposition in dermal vessel walls under direct immunofluorescence. Of 19 patients, 57% had elevated serum IgE levels.4

In addition to the associated dermatologic findings, the deer ked is a vector of various infectious agents. Bartonella schoenbuchensis has been isolated from deer ked in Massachusettes.7 A recent study found a 75% prevalence of Bartonella species in 217 deer keds collected from red deer in Poland.5 The first incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophylum in deer keds was reported in the United States in 2016. Of 48 adult deer keds collected from an unknown number of deer, 19 (40%), 14 (29%), and 3 (6%) were positive for B burgdorferi, A phagocytophylum, and both on polymerase chain reaction, respectively.3

A recent study from Europe showed deer keds are now more frequently found in regions where they had not previously been observed.8 It stands to reason that with climate change, L cervi and other disease-carrying vectors are likely to migrate to and inhabit new regions of the country. Even in the current climate, there are more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied in medicine, and all patients who experience an arthropod assault should be monitored for signs of systemic disease.

How to Prevent Mosquito and Tick-Borne Disease

Case Report

A 31-year-old man presented to the dermatology clinic 1 day after mountain biking in the woods in Hartford County, Connecticut. He stated that he found a tick attached to his shirt after riding (Figure). Careful examination of the patient showed no signs of a bite reaction. The insect was identified via microscopy as the deer ked Lipoptena cervi.

Comment

Lipoptena cervi, known as the deer ked, is an ectoparasite of cervids traditionally found in Norway, Sweden, and Finland.1 The deer ked was first reported in American deer in 2 independent sightings in Pennsylvania and New Hampshire in 1907.2 More recently deer keds have been reported in Massachusetts, New York, Pennsylvania, and New Hampshire.3 In the United States, L cervi is thought to be an invasive species transported from Europe in the 1800s.4,5 The main host is thought to be the white-tailed deer (Odocoileus viginianus). Once a suitable host is found, the deer ked sheds its wings and crawls into the fur. After engorging on a blood meal, it deposits prepupae that fall from the host and mature into winged adults during the late summer into the autumn. Adults may exhibit swarming behavior, and it is during this host-seeking activity that they land on humans.3

Following the bite of a deer ked, there are reports of long-lasting dermatitis in both humans and dogs.1,4,6 One case series involving 19 patients following deer ked bites reported pruritic bite papules.4 The reaction appeared to be treatment resistant and lasted from 2 weeks to 12 months. Histologic examination was typical for arthropod assault. Of 11 papules that were biopsied, most (7/11) showed C3 deposition in dermal vessel walls under direct immunofluorescence. Of 19 patients, 57% had elevated serum IgE levels.4

In addition to the associated dermatologic findings, the deer ked is a vector of various infectious agents. Bartonella schoenbuchensis has been isolated from deer ked in Massachusettes.7 A recent study found a 75% prevalence of Bartonella species in 217 deer keds collected from red deer in Poland.5 The first incidence of Borrelia burgdorferi and Anaplasma phagocytophylum in deer keds was reported in the United States in 2016. Of 48 adult deer keds collected from an unknown number of deer, 19 (40%), 14 (29%), and 3 (6%) were positive for B burgdorferi, A phagocytophylum, and both on polymerase chain reaction, respectively.3

A recent study from Europe showed deer keds are now more frequently found in regions where they had not previously been observed.8 It stands to reason that with climate change, L cervi and other disease-carrying vectors are likely to migrate to and inhabit new regions of the country. Even in the current climate, there are more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied in medicine, and all patients who experience an arthropod assault should be monitored for signs of systemic disease.

- Mysterud A, Madslien K, Herland A, et al. Phenology of deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) host-seeking flight activity and its relationship with prevailing autumn weather. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:95.

- Bequaert JC. A Monograph of the Melophaginae or Ked-flies of Sheep, Goats, Deer, and Antelopes (Diptera, Hippoboscidae). Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Entomological Society; 1942.

- Buss M, Case L, Kearney B, et al. Detection of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis pathogens via PCR in Pennsylvania deer ked. J Vector Ecol. 2016;41:292-294.

- Rantanen T, Reunala T, Vuojolahti P, et al. Persistent pruritic papules from deer ked bites. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:307-311.

- Szewczyk T, Werszko J, Steiner-Bogdaszewska Ż, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella spp. in deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:487.

- Hermosilla C, Pantchev N, Bachmann R, et al. Lipoptena cervi (deer ked) in two naturally infested dogs. Vet Rec. 2006;159:286-287.

- Matsumoto K, Berrada ZL, Klinger E, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella schoenbuchensis from ectoparasites of deer in Massachusetts. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:549-554.

- Sokół R, Gałęcki R. Prevalence of keds on city dogs in central Poland. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;31:114-116.

- Mysterud A, Madslien K, Herland A, et al. Phenology of deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) host-seeking flight activity and its relationship with prevailing autumn weather. Parasit Vectors. 2016;9:95.

- Bequaert JC. A Monograph of the Melophaginae or Ked-flies of Sheep, Goats, Deer, and Antelopes (Diptera, Hippoboscidae). Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Entomological Society; 1942.

- Buss M, Case L, Kearney B, et al. Detection of Lyme disease and anaplasmosis pathogens via PCR in Pennsylvania deer ked. J Vector Ecol. 2016;41:292-294.

- Rantanen T, Reunala T, Vuojolahti P, et al. Persistent pruritic papules from deer ked bites. Acta Derm Venereol. 1982;62:307-311.

- Szewczyk T, Werszko J, Steiner-Bogdaszewska Ż, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella spp. in deer ked (Lipoptena cervi) in Poland. Parasit Vectors. 2017;10:487.

- Hermosilla C, Pantchev N, Bachmann R, et al. Lipoptena cervi (deer ked) in two naturally infested dogs. Vet Rec. 2006;159:286-287.

- Matsumoto K, Berrada ZL, Klinger E, et al. Molecular detection of Bartonella schoenbuchensis from ectoparasites of deer in Massachusetts. Vector Borne Zoonotic Dis. 2008;8:549-554.

- Sokół R, Gałęcki R. Prevalence of keds on city dogs in central Poland. Med Vet Entomol. 2017;31:114-116.

Practice Points

- There are many more disease-carrying arthropods than are routinely studied by scientists and physicians.

- Even if the insect cannot be identified, it is important to monitor patients who have experienced arthropod assault for signs of clinical diseases.

Melanoma diagnosis does not deter pregnancy

Women in the United States do not appear to be delaying pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma, despite general recommendations to wait at least 2 years to attempt pregnancy because it might increase the risk of recurrence or exacerbate disease, investigators reported in the Journal of Surgical Research.

A review of records from a large national health care database showed that women aged 18-40 years with melanoma who were not pregnant on the index date had a significantly higher rate of pregnancy within 2 years, compared with matched controls, reported Julie A. DiSano, MD, from Penn State University, Hershey.

“These results suggest that a diagnosis of melanoma may serve as an impetus for some families to begin childbearing or have additional children sooner than they otherwise would have,” they wrote.

The investigators also found, reassuringly, that women who became pregnant after a melanoma diagnosis were not at increased risk for requiring additional therapy for the malignancy, at least in the short term.

Although earlier studies suggested that women who were pregnant at the time of a melanoma diagnosis had worse prognoses when compared with women who were not pregnant at the time of diagnosis, more recent studies have indicated women who are pregnant when diagnosed have similar outcomes as nonpregnant women with the same disease stage, the investigators noted.

“What is unclear and difficult to study is the relationship between melanoma and subsequent pregnancy rates, and pregnancy on melanoma outcomes. Very little data exist to guide women and physicians as to the safety of pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma. As a result, there are no formal guidelines for physicians who wish to counsel their patients regarding pregnancy after melanoma, and it is unknown whether women receive any counseling at all,” they wrote.

To get a clearer picture of the link between melanoma and subsequent pregnancy, the investigators scanned the Truven Health MarketScan database and identified 11,801 women from 18-40 years with melanoma who were not pregnant on the index date, determined by the earliest claim for melanoma diagnosis or therapy.

Each patient was matched on a 1:1 basis with women who did not have a melanoma claim at any time; cases were matched with controls on the basis of year of index date, age at index date, state of residence, and pregnancy status in the 90 days before the index date.

The authors found that the rate of pregnancy within 2 years of the index date was 15.8% for cases, compared with 13.6% for controls (P less than .001).

They also found, however, that women who required postsurgical therapy, suggesting more advanced disease stage or early recurrence, had a significantly lower probability of becoming pregnant within the first 9 months after the index date (hazard ratio, 0.26; P = .003).

There were no significant differences in the rate of postsurgical treatment by pregnancy status at either 3, 6, 9, or 12 months after surgery (P less than .05 for each), or in a Cox regression model for all time points (HR, 0.68, P = .23).

The authors offered several possible explanations for the higher pregnancy rates among women with melanoma, including the possibility that a cancer diagnosis could bring some couples closer together and “reorder” their priorities about starting a family.

“Another hypothesis is that families facing a melanoma diagnosis may decide to complete childbearing sooner in case the cancer recurs and subsequent treatment compromises fertility. Either way, the increased likelihood of pregnancy after melanoma diagnosis suggests an optimism about their future among families in the current childbearing generation in the United States,” they wrote.

The authors cautioned that the database does not include information about disease stage, and that “more detailed stage information is needed before revisiting recommendations.”

The study was supported by a Barsumian Trust grant; the authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DiSano JA et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Jun 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.05.026.

Women in the United States do not appear to be delaying pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma, despite general recommendations to wait at least 2 years to attempt pregnancy because it might increase the risk of recurrence or exacerbate disease, investigators reported in the Journal of Surgical Research.

A review of records from a large national health care database showed that women aged 18-40 years with melanoma who were not pregnant on the index date had a significantly higher rate of pregnancy within 2 years, compared with matched controls, reported Julie A. DiSano, MD, from Penn State University, Hershey.

“These results suggest that a diagnosis of melanoma may serve as an impetus for some families to begin childbearing or have additional children sooner than they otherwise would have,” they wrote.

The investigators also found, reassuringly, that women who became pregnant after a melanoma diagnosis were not at increased risk for requiring additional therapy for the malignancy, at least in the short term.

Although earlier studies suggested that women who were pregnant at the time of a melanoma diagnosis had worse prognoses when compared with women who were not pregnant at the time of diagnosis, more recent studies have indicated women who are pregnant when diagnosed have similar outcomes as nonpregnant women with the same disease stage, the investigators noted.

“What is unclear and difficult to study is the relationship between melanoma and subsequent pregnancy rates, and pregnancy on melanoma outcomes. Very little data exist to guide women and physicians as to the safety of pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma. As a result, there are no formal guidelines for physicians who wish to counsel their patients regarding pregnancy after melanoma, and it is unknown whether women receive any counseling at all,” they wrote.

To get a clearer picture of the link between melanoma and subsequent pregnancy, the investigators scanned the Truven Health MarketScan database and identified 11,801 women from 18-40 years with melanoma who were not pregnant on the index date, determined by the earliest claim for melanoma diagnosis or therapy.

Each patient was matched on a 1:1 basis with women who did not have a melanoma claim at any time; cases were matched with controls on the basis of year of index date, age at index date, state of residence, and pregnancy status in the 90 days before the index date.

The authors found that the rate of pregnancy within 2 years of the index date was 15.8% for cases, compared with 13.6% for controls (P less than .001).

They also found, however, that women who required postsurgical therapy, suggesting more advanced disease stage or early recurrence, had a significantly lower probability of becoming pregnant within the first 9 months after the index date (hazard ratio, 0.26; P = .003).

There were no significant differences in the rate of postsurgical treatment by pregnancy status at either 3, 6, 9, or 12 months after surgery (P less than .05 for each), or in a Cox regression model for all time points (HR, 0.68, P = .23).

The authors offered several possible explanations for the higher pregnancy rates among women with melanoma, including the possibility that a cancer diagnosis could bring some couples closer together and “reorder” their priorities about starting a family.

“Another hypothesis is that families facing a melanoma diagnosis may decide to complete childbearing sooner in case the cancer recurs and subsequent treatment compromises fertility. Either way, the increased likelihood of pregnancy after melanoma diagnosis suggests an optimism about their future among families in the current childbearing generation in the United States,” they wrote.

The authors cautioned that the database does not include information about disease stage, and that “more detailed stage information is needed before revisiting recommendations.”

The study was supported by a Barsumian Trust grant; the authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DiSano JA et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Jun 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.05.026.

Women in the United States do not appear to be delaying pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma, despite general recommendations to wait at least 2 years to attempt pregnancy because it might increase the risk of recurrence or exacerbate disease, investigators reported in the Journal of Surgical Research.

A review of records from a large national health care database showed that women aged 18-40 years with melanoma who were not pregnant on the index date had a significantly higher rate of pregnancy within 2 years, compared with matched controls, reported Julie A. DiSano, MD, from Penn State University, Hershey.

“These results suggest that a diagnosis of melanoma may serve as an impetus for some families to begin childbearing or have additional children sooner than they otherwise would have,” they wrote.

The investigators also found, reassuringly, that women who became pregnant after a melanoma diagnosis were not at increased risk for requiring additional therapy for the malignancy, at least in the short term.

Although earlier studies suggested that women who were pregnant at the time of a melanoma diagnosis had worse prognoses when compared with women who were not pregnant at the time of diagnosis, more recent studies have indicated women who are pregnant when diagnosed have similar outcomes as nonpregnant women with the same disease stage, the investigators noted.

“What is unclear and difficult to study is the relationship between melanoma and subsequent pregnancy rates, and pregnancy on melanoma outcomes. Very little data exist to guide women and physicians as to the safety of pregnancy after a diagnosis of melanoma. As a result, there are no formal guidelines for physicians who wish to counsel their patients regarding pregnancy after melanoma, and it is unknown whether women receive any counseling at all,” they wrote.

To get a clearer picture of the link between melanoma and subsequent pregnancy, the investigators scanned the Truven Health MarketScan database and identified 11,801 women from 18-40 years with melanoma who were not pregnant on the index date, determined by the earliest claim for melanoma diagnosis or therapy.

Each patient was matched on a 1:1 basis with women who did not have a melanoma claim at any time; cases were matched with controls on the basis of year of index date, age at index date, state of residence, and pregnancy status in the 90 days before the index date.

The authors found that the rate of pregnancy within 2 years of the index date was 15.8% for cases, compared with 13.6% for controls (P less than .001).

They also found, however, that women who required postsurgical therapy, suggesting more advanced disease stage or early recurrence, had a significantly lower probability of becoming pregnant within the first 9 months after the index date (hazard ratio, 0.26; P = .003).

There were no significant differences in the rate of postsurgical treatment by pregnancy status at either 3, 6, 9, or 12 months after surgery (P less than .05 for each), or in a Cox regression model for all time points (HR, 0.68, P = .23).

The authors offered several possible explanations for the higher pregnancy rates among women with melanoma, including the possibility that a cancer diagnosis could bring some couples closer together and “reorder” their priorities about starting a family.

“Another hypothesis is that families facing a melanoma diagnosis may decide to complete childbearing sooner in case the cancer recurs and subsequent treatment compromises fertility. Either way, the increased likelihood of pregnancy after melanoma diagnosis suggests an optimism about their future among families in the current childbearing generation in the United States,” they wrote.

The authors cautioned that the database does not include information about disease stage, and that “more detailed stage information is needed before revisiting recommendations.”

The study was supported by a Barsumian Trust grant; the authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: DiSano JA et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Jun 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.05.026.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF SURGICAL RESEARCH

Key clinical point: Pregnancy after melanoma does not appear to increase risk for melanoma recurrence.

Major finding: The rate of pregnancy for women with melanoma was 15.8%, compared with 13.6% for controls (P less than .001).

Study details: A retrospective study of claims database records on 11,801 women with melanoma and an equal number of matched controls.

Disclosures: The study was supported by a Barsumian Trust grant; the authors reported having no conflicts of interest.

Source: DiSano JA et al. J Surg Res. 2018 Jun 16. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2018.05.026.

Chronic Migraine Is Associated With Changes in Age-Related Cortical Thickness

Some brain areas are thicker, and others thinner, in patients with chronic migraine, compared with controls.

SAN FRANCISCO—Chronic migraine is associated with increased age-related cortical thinning of some brain areas and decreased age-related cortical thinning in other areas, according to research presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. It remains uncertain whether these cortical changes are a cause or an effect of chronic migraine.

Age-related cortical integrity had not been explored in chronic migraine previously. To investigate this topic, Yohannes Woubishet Woldeamanuel, MD, Instructor in Neurology and Neurologic Sciences at Stanford University in California, and colleagues enrolled 30 patients with chronic migraine and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy controls into a study. All participants were right-handed. The mean age in the chronic migraine group was 40.5, and the male-to-female ratio was 1:4. Investigators obtained the duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine from participants with chronic migraine.

Dr. Woldeamanuel and colleagues acquired T1-weighted brain images on a 3T MRI from all participants. They analyzed whole-brain cortical thickness on unmasked images. The investigators used linear regression to examine group differences on age by cortical thickness between people with chronic migraine and controls. Multiple regression enabled the researchers to control for the confounding effect of duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine on age-related cortical thickness changes.

Compared with controls, patients with chronic migraine had significant age-related thinning of the lateral orbitofrontal and supramarginal cortex of the left hemisphere. Patients with chronic migraine had a lack of age-related thinning of the pars orbitalis, superior and inferior parietal, superior temporal, pars opercularis, posterior cingulate, precuneus, superior frontal of the left hemisphere, and the left hemisphere mean cortical thickness, however. In the right hemisphere, the chronic migraine group had significant age-related thinning of the banks of the superior temporal sulcus, caudal anterior cingulate, inferior parietal, precuneus, and supramarginal cortex. The chronic migraine group lacked age-related thinning of the caudal middle frontal, isthmus cingulate, lateral orbitofrontal, paracentral, pars orbitalis, posterior cingulate, rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, and temporal pole of the right hemisphere. These results were not influenced by duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine.

The absence of normative age-related cortical thinning in implicated brain areas possibly indicates a perpetually enhanced headache response, head pain cognition, visual and auditory processing, affective behavior, interaction with internal and external cues, and multisensory integration, said the researchers. Accelerated age-related thinning in brain areas involved in sensory pain pathways could represent reduced habituation in chronic migraine, they added. In addition, age-related cortical thinning might indicate progressive loss of migraine modulation. The investigators hypothesized that repetitive migraine attacks might increase allostatic load from headache and nonheadache migraine symptoms.

“We are following these cohorts to determine whether these age-related cortical thickness changes signify cause or effect of chronic migraine,” said Dr. Woldeamanuel.

Suggested Reading

Chong CD, Dodick DW, Schlaggar BL, Schwedt TJ. Atypical age-related cortical thinning in episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(14):1115-1124.

Schwedt TJ, Berisha V, Chong CD. Temporal lobe cortical thickness correlations differentiate the migraine brain from the healthy brain. PLoS One. 2015 Feb 13;10(2):e0116687.

Some brain areas are thicker, and others thinner, in patients with chronic migraine, compared with controls.

Some brain areas are thicker, and others thinner, in patients with chronic migraine, compared with controls.

SAN FRANCISCO—Chronic migraine is associated with increased age-related cortical thinning of some brain areas and decreased age-related cortical thinning in other areas, according to research presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. It remains uncertain whether these cortical changes are a cause or an effect of chronic migraine.

Age-related cortical integrity had not been explored in chronic migraine previously. To investigate this topic, Yohannes Woubishet Woldeamanuel, MD, Instructor in Neurology and Neurologic Sciences at Stanford University in California, and colleagues enrolled 30 patients with chronic migraine and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy controls into a study. All participants were right-handed. The mean age in the chronic migraine group was 40.5, and the male-to-female ratio was 1:4. Investigators obtained the duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine from participants with chronic migraine.

Dr. Woldeamanuel and colleagues acquired T1-weighted brain images on a 3T MRI from all participants. They analyzed whole-brain cortical thickness on unmasked images. The investigators used linear regression to examine group differences on age by cortical thickness between people with chronic migraine and controls. Multiple regression enabled the researchers to control for the confounding effect of duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine on age-related cortical thickness changes.

Compared with controls, patients with chronic migraine had significant age-related thinning of the lateral orbitofrontal and supramarginal cortex of the left hemisphere. Patients with chronic migraine had a lack of age-related thinning of the pars orbitalis, superior and inferior parietal, superior temporal, pars opercularis, posterior cingulate, precuneus, superior frontal of the left hemisphere, and the left hemisphere mean cortical thickness, however. In the right hemisphere, the chronic migraine group had significant age-related thinning of the banks of the superior temporal sulcus, caudal anterior cingulate, inferior parietal, precuneus, and supramarginal cortex. The chronic migraine group lacked age-related thinning of the caudal middle frontal, isthmus cingulate, lateral orbitofrontal, paracentral, pars orbitalis, posterior cingulate, rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, and temporal pole of the right hemisphere. These results were not influenced by duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine.

The absence of normative age-related cortical thinning in implicated brain areas possibly indicates a perpetually enhanced headache response, head pain cognition, visual and auditory processing, affective behavior, interaction with internal and external cues, and multisensory integration, said the researchers. Accelerated age-related thinning in brain areas involved in sensory pain pathways could represent reduced habituation in chronic migraine, they added. In addition, age-related cortical thinning might indicate progressive loss of migraine modulation. The investigators hypothesized that repetitive migraine attacks might increase allostatic load from headache and nonheadache migraine symptoms.

“We are following these cohorts to determine whether these age-related cortical thickness changes signify cause or effect of chronic migraine,” said Dr. Woldeamanuel.

Suggested Reading

Chong CD, Dodick DW, Schlaggar BL, Schwedt TJ. Atypical age-related cortical thinning in episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(14):1115-1124.

Schwedt TJ, Berisha V, Chong CD. Temporal lobe cortical thickness correlations differentiate the migraine brain from the healthy brain. PLoS One. 2015 Feb 13;10(2):e0116687.

SAN FRANCISCO—Chronic migraine is associated with increased age-related cortical thinning of some brain areas and decreased age-related cortical thinning in other areas, according to research presented at the 60th Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Headache Society. It remains uncertain whether these cortical changes are a cause or an effect of chronic migraine.

Age-related cortical integrity had not been explored in chronic migraine previously. To investigate this topic, Yohannes Woubishet Woldeamanuel, MD, Instructor in Neurology and Neurologic Sciences at Stanford University in California, and colleagues enrolled 30 patients with chronic migraine and 30 age- and sex-matched healthy controls into a study. All participants were right-handed. The mean age in the chronic migraine group was 40.5, and the male-to-female ratio was 1:4. Investigators obtained the duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine from participants with chronic migraine.

Dr. Woldeamanuel and colleagues acquired T1-weighted brain images on a 3T MRI from all participants. They analyzed whole-brain cortical thickness on unmasked images. The investigators used linear regression to examine group differences on age by cortical thickness between people with chronic migraine and controls. Multiple regression enabled the researchers to control for the confounding effect of duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine on age-related cortical thickness changes.

Compared with controls, patients with chronic migraine had significant age-related thinning of the lateral orbitofrontal and supramarginal cortex of the left hemisphere. Patients with chronic migraine had a lack of age-related thinning of the pars orbitalis, superior and inferior parietal, superior temporal, pars opercularis, posterior cingulate, precuneus, superior frontal of the left hemisphere, and the left hemisphere mean cortical thickness, however. In the right hemisphere, the chronic migraine group had significant age-related thinning of the banks of the superior temporal sulcus, caudal anterior cingulate, inferior parietal, precuneus, and supramarginal cortex. The chronic migraine group lacked age-related thinning of the caudal middle frontal, isthmus cingulate, lateral orbitofrontal, paracentral, pars orbitalis, posterior cingulate, rostral middle frontal, superior frontal, and temporal pole of the right hemisphere. These results were not influenced by duration of chronic migraine and lifetime migraine.

The absence of normative age-related cortical thinning in implicated brain areas possibly indicates a perpetually enhanced headache response, head pain cognition, visual and auditory processing, affective behavior, interaction with internal and external cues, and multisensory integration, said the researchers. Accelerated age-related thinning in brain areas involved in sensory pain pathways could represent reduced habituation in chronic migraine, they added. In addition, age-related cortical thinning might indicate progressive loss of migraine modulation. The investigators hypothesized that repetitive migraine attacks might increase allostatic load from headache and nonheadache migraine symptoms.

“We are following these cohorts to determine whether these age-related cortical thickness changes signify cause or effect of chronic migraine,” said Dr. Woldeamanuel.

Suggested Reading

Chong CD, Dodick DW, Schlaggar BL, Schwedt TJ. Atypical age-related cortical thinning in episodic migraine. Cephalalgia. 2014;34(14):1115-1124.

Schwedt TJ, Berisha V, Chong CD. Temporal lobe cortical thickness correlations differentiate the migraine brain from the healthy brain. PLoS One. 2015 Feb 13;10(2):e0116687.

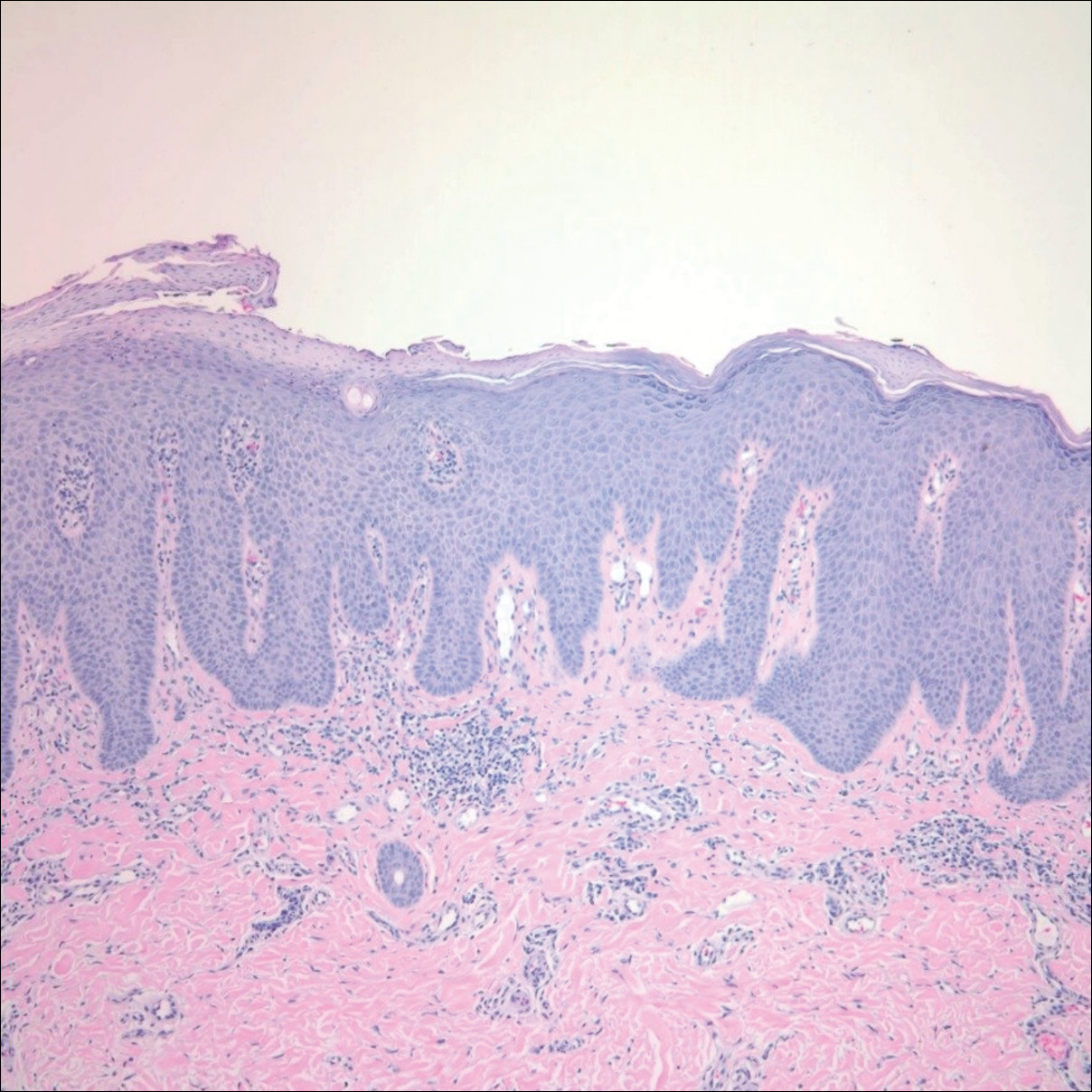

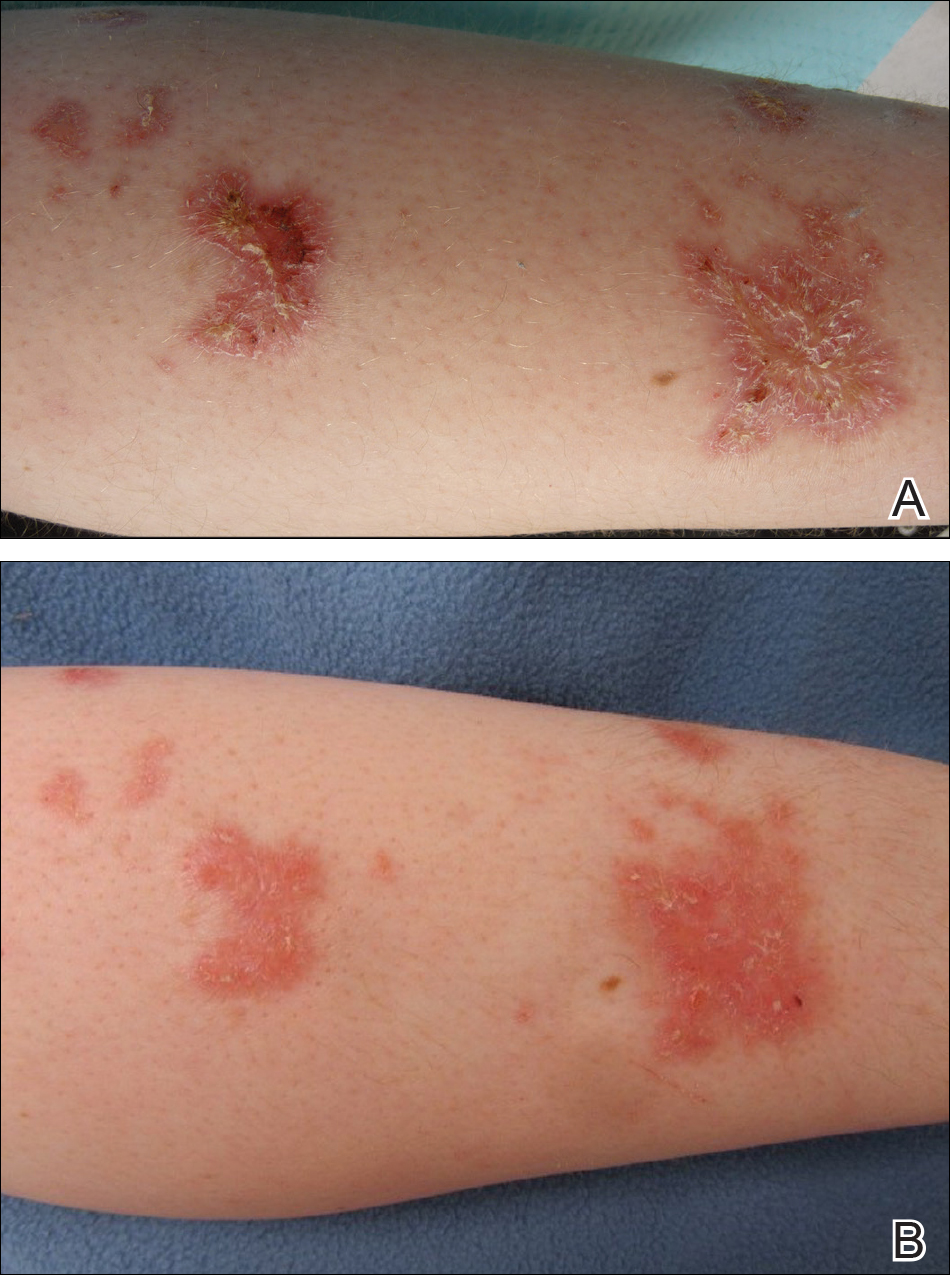

Latex Hypersensitivity to Injection Devices for Biologic Therapies in Psoriasis Patients

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

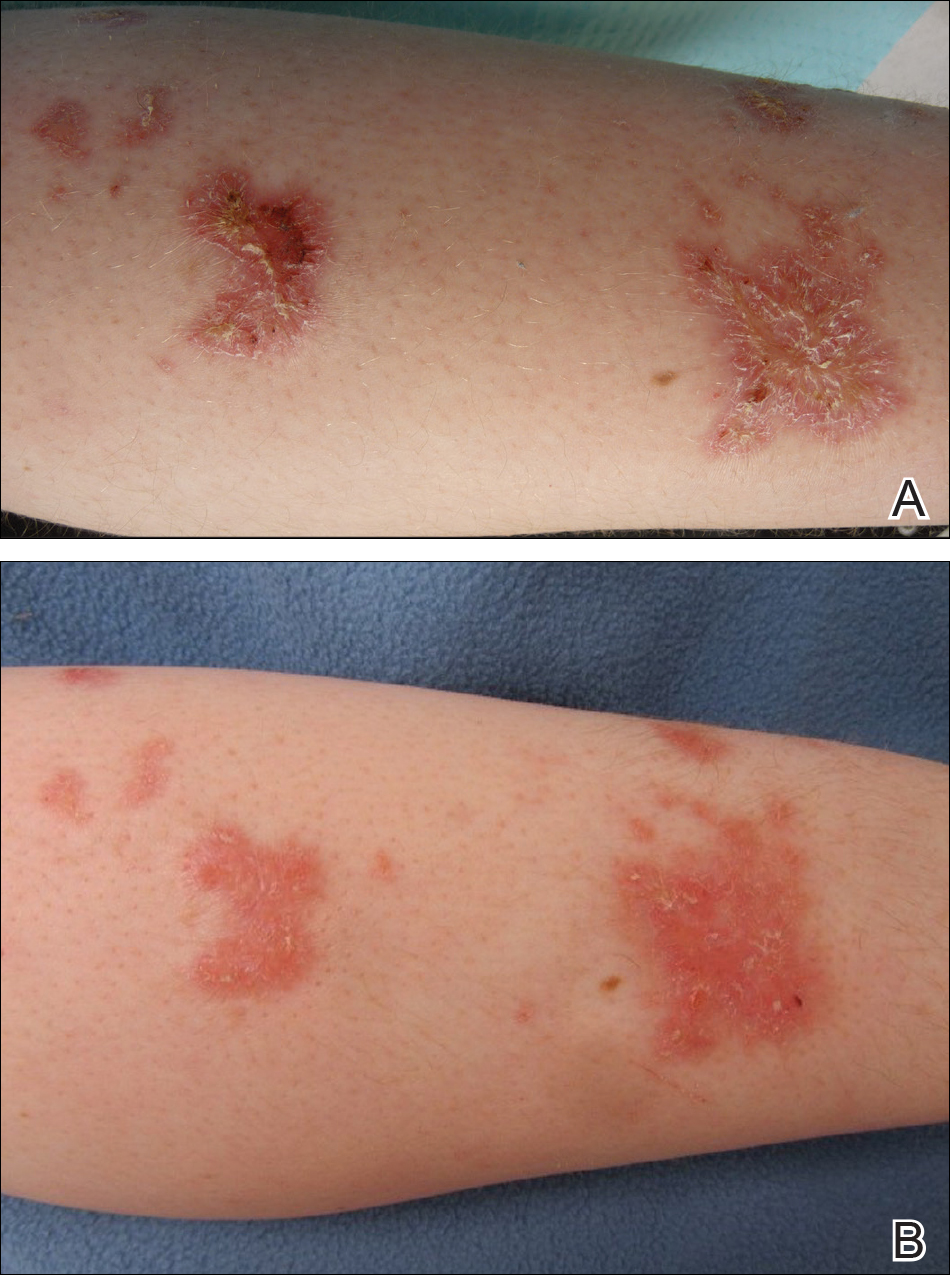

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

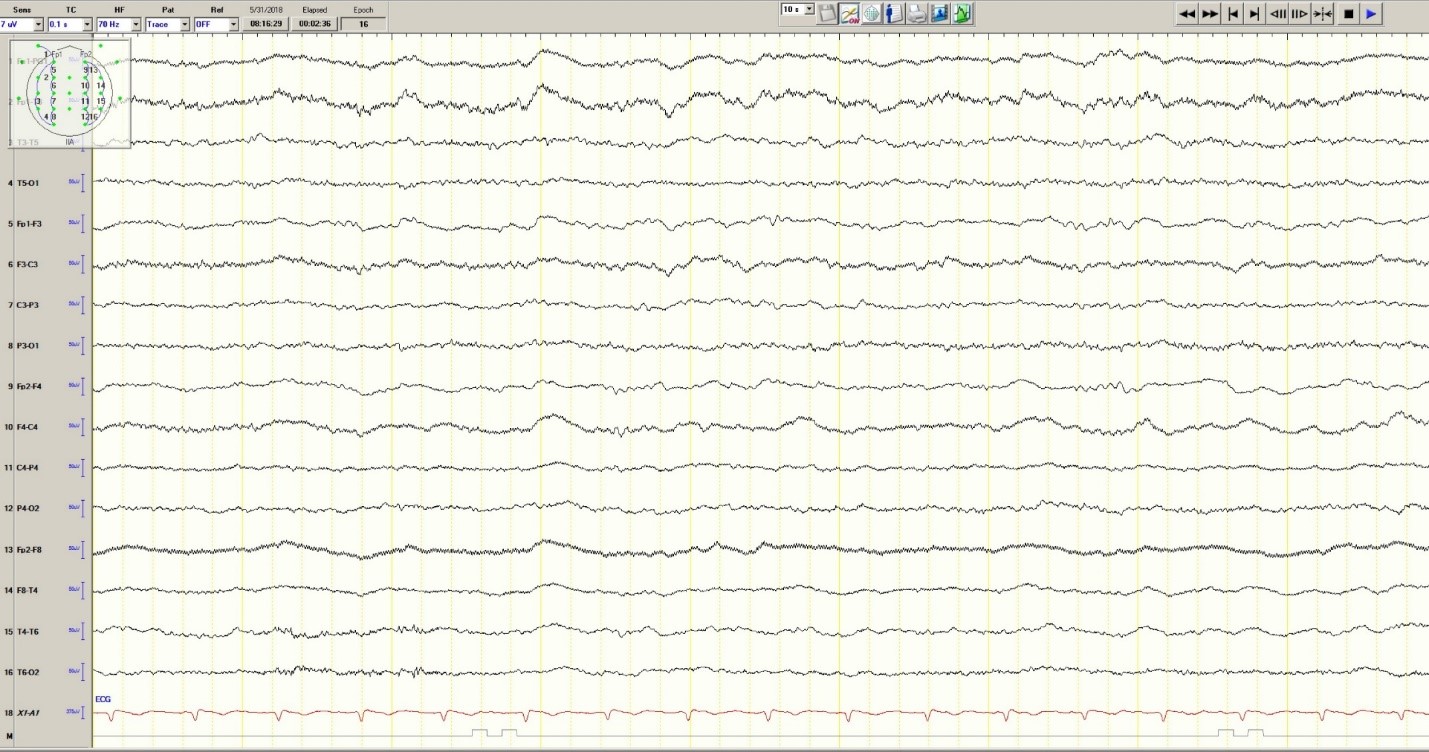

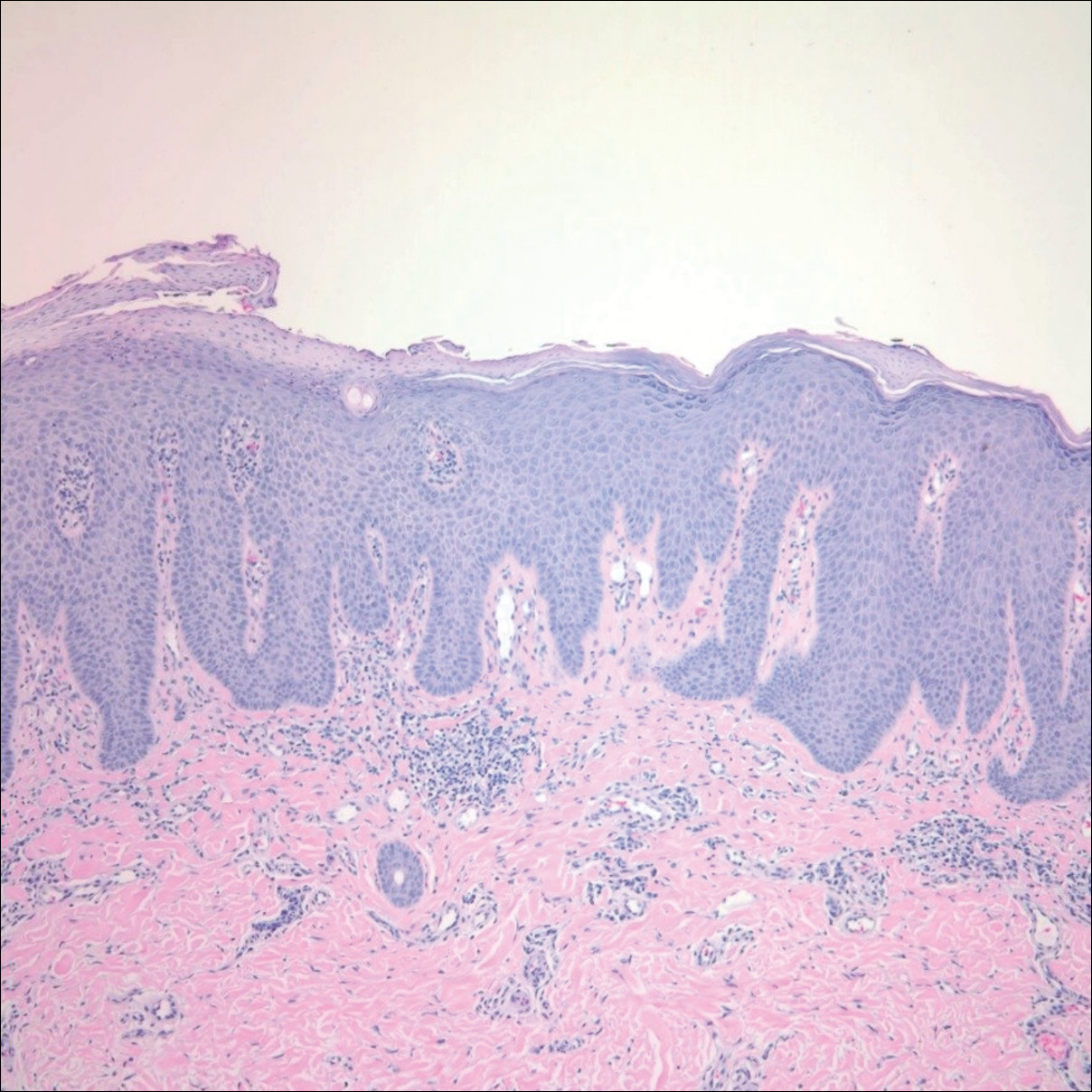

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment

Allergic responses to latex are most commonly seen in those exposed to gloves or rubber, but little has been reported on reactions to injections with pens or syringes that contain latex components. Some case reports have demonstrated allergic responses in diabetic patients receiving insulin injections.5,6 MacCracken et al5 reported the case of a young boy who had an allergic response to an insulin injection with a syringe containing latex. The patient had a history of bladder exstrophy with a recent diagnosis of diabetes mellitus. It is well known that patients with spina bifida and other conditions who undergo frequent urological procedures more commonly develop latex allergies. This patient reported a history of swollen lips after a dentist visit, presumably due to contact with latex gloves. Because of the suspected allergy, his first insulin injection was given using a glass syringe and insulin was withdrawn with the top removed due to the top containing latex. He did not experience any complications. After being injected later with insulin drawn through the top using a syringe that contained latex, he developed a flare-up of a 0.5-cm erythematous wheal within minutes with associated pruritus.5

Towse et al6 described another patient with diabetes who developed a local allergic reaction at the site of insulin injections. Workup by the physician ruled out insulin allergy but showed elevated latex-specific IgE antibodies. Future insulin draws through a latex-containing top produced a wheal at the injection site. After switching to latex-free syringes, the allergic reaction resolved.6

Latex allergies are common in medical practice, as latex is found in a wide variety of medical supplies, including syringes used for injections and their caps. Physicians need to be aware of latex allergies in their patients and exercise extreme caution in the use of latex-containing products. In the treatment of psoriasis, care must be given when injecting biologic agents. Although many injection devices contain latex limited to the cap, it may be enough to invoke an allergic response. If such a response is elicited, therapy with injection devices that do not contain latex in either the cap or syringe should be considered.

- Druce HM. Allergic and nonallergic rhinitis. In: Middleton EM Jr, Reed CE, Ellis EF, et al, eds. Allergy: Principles and Practice. 5th ed. Vol 1. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1998:1005-1016.

- Rochford C, Milles M. A review of the pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management of allergic reactions in the dental office. Quintessence Int. 2011;42:149-156.

- Hamilton RG, Peterson EL, Ownby DR. Clinical and laboratory-based methods in the diagnosis of natural rubber latex allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;110(2 suppl):S47-S56.

- Shibata M, Sawada Y, Yamaguchi T, et al. Drug eruption caused by secukinumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2017;27:67-68.

- MacCracken J, Stenger P, Jackson T. Latex allergy in diabetic patients: a call for latex-free insulin tops. Diabetes Care. 1996;19:184.

- Towse A, O'Brien M, Twarog FJ, et al. Local reaction secondary to insulin injection: a potential role for latex antigens in insulin vials and syringes. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1195-1197.

An allergic reaction is an exaggerated immune response that is known as a type I or immediate hypersensitivity reaction when provoked by reexposure to an allergen or antigen. Upon initial exposure to the antigen, dendritic cells bind it for presentation to helper T (TH2) lymphocytes. The TH2 cells then interact with B cells, stimulating them to become plasma cells and produce IgE antibodies to the antigen. When exposed to the same allergen a second time, IgE antibodies bind the allergen and cross-link on mast cells and basophils in the blood. Cross-linking stimulates degranulation of the cells, releasing histamine, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, and other cytokines. The major effects of the release of these mediators include vasodilation, increased vascular permeability, and bronchoconstriction. Leukotrienes also are responsible for chemotaxis of white blood cells, further propagating the immune response.1

Effects of a type I hypersensitivity reaction can be either local or systemic, resulting in symptoms ranging from mild irritation to anaphylactic shock and death. Latex allergy is a common example of a type I hypersensitivity reaction. Latex is found in many medical products, including gloves, rubber, elastics, blood pressure cuffs, bandages, dressings, and syringes. Reactions can include runny nose, tearing eyes, itching, hives, wheals, wheezing, and in rare cases anaphylaxis.2 Diagnosis can be suspected based on history and physical examination. Screening is performed with radioallergosorbent testing, which identifies specific IgE antibodies to latex; however, the reported sensitivity and specificity for the latex-specific IgE antibody varies widely in the literature, and the test cannot reliably rule in or rule out a true latex allergy.3

Allergic responses to latex in psoriasis patients receiving frequent injections with biologic agents are not commonly reported in the literature. We report the case of a patient with a long history of psoriasis who developed an allergic response after exposure to injection devices that contained latex components while undergoing treatment with biologic agents.

Case Report

A 72-year-old man presented with an extensive history of severe psoriasis with frequent flares. Treatment with topical agents and etanercept 6 months prior at an outside facility failed. At the time of presentation, the patient had more than 10% body surface area (BSA) involvement, which included the scalp, legs, chest, and back. He subsequently was started on ustekinumab injections. He initially responded well to therapy, but after 8 months of treatment, he began to have recurrent episodes of acute eruptive rashes over the trunk with associated severe pruritus that reproducibly recurred within 24 hours after each ustekinumab injection. It was decided to discontinue ustekinumab due to concern for intolerance, and the patient was switched to secukinumab.

After starting secukinumab, the patient's BSA involvement was reduced to 2% after 1 month; however, he began to develop an eruptive rash with severe pruritus again that reproducibly recurred after each secukinumab injection. On physical examination the patient had ill-defined, confluent, erythematous patches over much of the trunk and extremities. Punch biopsies of the eruptive dermatitis showed spongiform psoriasis and eosinophils with dermal hypersensitivity, consistent with a drug eruption. Upon further questioning, the patient noted that he had a long history of a strong latex allergy and he would develop a blistering dermatitis when coming into contact with latex, which caused a high suspicion for a latex allergy as the cause of the patient's acute dermatitis flares from his prior ustekinumab and secukinumab injections. Although it was confirmed with the manufacturers that both the ustekinumab syringe and secukinumab pen did not contain latex, the caps of these medications (and many other biologic injections) do have latex (Table). Other differential diagnoses included an atypical paradoxical psoriasis flare and a drug eruption to secukinumab, which previously has been reported.4

Based on the suspected cause of the eruption, the patient was instructed not to touch the cap of the secukinumab pen. Despite this recommendation, the rash was still present at the next appointment 1 month later. Repeat punch biopsy showed similar findings to the one prior with likely dermal hypersensitivity. The rash improved with steroid injections and continued to improve after holding the secukinumab for 1 month.

After resolution of the hypersensitivity reaction, the patient was started on ixekizumab, which does not contain latex in any component according to the manufacturer. After 2 months of treatment, the patient had 2% BSA involvement of psoriasis and has had no further reports of itching, rash, or other symptoms of a hypersensitivity reaction. On follow-up, the patient's psoriasis symptoms continue to be controlled without further reactions after injections of ixekizumab. Radioallergosorbent testing was not performed due to the lack of specificity and sensitivity of the test3 as well as the patient's known history of latex allergy and characteristic dermatitis that developed after exposure to latex and resolution with removal of the agent. These clinical manifestations are highly indicative of a type I hypersensitivity to injection devices that contain latex components during biologic therapy.

Comment