User login

HPV positivity associated with good esophageal adenocarcinoma outcomes

Patients with Barrett high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma who are positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection have significantly better outcomes than patients with the same diseases who are negative for HPV, investigators report.

Among patients with Barrett high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), mean disease-free survival (DFS) was 40.3 months for HPV-positive patients, compared with 24.1 months for HPV-negative patients (P = .003). Mean overall survival was also significantly better in HPV-positive patients, at 43.7 months versus 29.8 months (P =.009) respectively, reported Shanmugarajah Rajendra, MD, from Bankstown-Lincombe Hospital in Sydney and colleagues.

“If these findings of a favorable prognosis of HPV-positive HGD and EAC are confirmed in larger cohorts with more advanced disease, it presents an opportunity for treatment de-escalation in the hope of reducing toxic effects without deleteriously affecting survival,” they wrote in JAMA Network Open.

The findings support those of earlier studies suggesting that HPV infection is associated with better prognosis among patients with other cancers of the head and neck. For example, a retrospective analysis of data from two clinical trials reported in 2014 found that, 2 years after a diagnosis of recurrent oropharyngeal cancer, 54.6% of HPV-positive patients were alive, compared with 27.6% of HPV-negative patients (P less than .001).

To determine whether there was a similar association between HPV infection and better prognosis of Barrett HGD or EAC, Dr. Rajendra and associates conducted a retrospective case-control study of 142 patients with HGD or EAC treated at secondary or tertiary referral centers in Australia. The patients, all of whom were white, included 126 men. The mean age was 66 years, and in all, 37 patients were positive for HPV.

As noted before, both DFS and overall survival were significantly better for HPV-infected patients, with mean differences of 16.2 months and 13.9 months, respectively. HPV-positive patients also had lower rates of progression or recurrence (24.3% vs. 58.1%; P less than .001), distant metastases (8.1% vs. 27.6%; P = .02), and death from EAC (13.5% vs. 36.2%; P = .02).

In multivariate analysis, superior DFS was associated with HPV positivity, (hazard ratio, 0.39; P = .02), biologically active virus (HR, 0.36; P = .02), E6 and E7 messenger RNA (HR, 0.36; P = .04), and with high p16 expression (HR, 0.49; P = .02).

The study was supported by the South Western Sydney Clinical School; the University of New South Wales, Sydney; and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund. Dr. Rajendra reported grants from the University of New South Wales and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Rajendra S et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Aug 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1054.

The study by Rajendra et al highlights the potential role of human papillomavirus (HPV) status in the prognosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). However, the use of HPV as a predictive marker for treatment remains unproven, and many questions abound. Important considerations for studies of de-escalation of treatment in HPV-positive EAC include how best to select patients for less intensive treatment: Should trials be restricted to nonsmoking patients with better prognosis pathology characteristics, including lower T stage and lack of lymph node involvement? What is the best method to assess HPV status in a cost-effective and easily available assay for broad international use? Should there be a de-escalation of chemotherapy, radiation, or both? Is there potentially a role for de-escalation of surgery? Are these trials that patients would consider participation in given the lethality of these cancers?

Finally, the presence of a vaccine for HPV may affect the incidence of cervical, oropharyngeal, and other cancers. If HPV is an important risk factor for EAC, we may see a reduction in the rates of this highly lethal cancer over time. These benefits may take some time to bear out and are highly dependent on vaccination rates. Nonetheless, primary prevention of HPV infection may result in a significant reduction in the global burden of this disease. In the meantime, larger-scale studies of the role of HPV in the pathogenesis of EAC are warranted, particularly before moving toward trials of less intensive therapy. While the results of this small cohort study are impressive, they are preliminary, and the study requires confirmation in a larger, prospective trial.

Sukhbinder Dhesy-Thind, MD, FRCPC is from McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. Her remarks are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study. She reported personal fees from Teva Canada Innovation and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada outside the submitted work.

The study by Rajendra et al highlights the potential role of human papillomavirus (HPV) status in the prognosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). However, the use of HPV as a predictive marker for treatment remains unproven, and many questions abound. Important considerations for studies of de-escalation of treatment in HPV-positive EAC include how best to select patients for less intensive treatment: Should trials be restricted to nonsmoking patients with better prognosis pathology characteristics, including lower T stage and lack of lymph node involvement? What is the best method to assess HPV status in a cost-effective and easily available assay for broad international use? Should there be a de-escalation of chemotherapy, radiation, or both? Is there potentially a role for de-escalation of surgery? Are these trials that patients would consider participation in given the lethality of these cancers?

Finally, the presence of a vaccine for HPV may affect the incidence of cervical, oropharyngeal, and other cancers. If HPV is an important risk factor for EAC, we may see a reduction in the rates of this highly lethal cancer over time. These benefits may take some time to bear out and are highly dependent on vaccination rates. Nonetheless, primary prevention of HPV infection may result in a significant reduction in the global burden of this disease. In the meantime, larger-scale studies of the role of HPV in the pathogenesis of EAC are warranted, particularly before moving toward trials of less intensive therapy. While the results of this small cohort study are impressive, they are preliminary, and the study requires confirmation in a larger, prospective trial.

Sukhbinder Dhesy-Thind, MD, FRCPC is from McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. Her remarks are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study. She reported personal fees from Teva Canada Innovation and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada outside the submitted work.

The study by Rajendra et al highlights the potential role of human papillomavirus (HPV) status in the prognosis of esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC). However, the use of HPV as a predictive marker for treatment remains unproven, and many questions abound. Important considerations for studies of de-escalation of treatment in HPV-positive EAC include how best to select patients for less intensive treatment: Should trials be restricted to nonsmoking patients with better prognosis pathology characteristics, including lower T stage and lack of lymph node involvement? What is the best method to assess HPV status in a cost-effective and easily available assay for broad international use? Should there be a de-escalation of chemotherapy, radiation, or both? Is there potentially a role for de-escalation of surgery? Are these trials that patients would consider participation in given the lethality of these cancers?

Finally, the presence of a vaccine for HPV may affect the incidence of cervical, oropharyngeal, and other cancers. If HPV is an important risk factor for EAC, we may see a reduction in the rates of this highly lethal cancer over time. These benefits may take some time to bear out and are highly dependent on vaccination rates. Nonetheless, primary prevention of HPV infection may result in a significant reduction in the global burden of this disease. In the meantime, larger-scale studies of the role of HPV in the pathogenesis of EAC are warranted, particularly before moving toward trials of less intensive therapy. While the results of this small cohort study are impressive, they are preliminary, and the study requires confirmation in a larger, prospective trial.

Sukhbinder Dhesy-Thind, MD, FRCPC is from McMaster University, Hamilton, Ontario. Her remarks are excerpted from an editorial accompanying the study. She reported personal fees from Teva Canada Innovation and Novartis Pharmaceuticals Canada outside the submitted work.

Patients with Barrett high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma who are positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection have significantly better outcomes than patients with the same diseases who are negative for HPV, investigators report.

Among patients with Barrett high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), mean disease-free survival (DFS) was 40.3 months for HPV-positive patients, compared with 24.1 months for HPV-negative patients (P = .003). Mean overall survival was also significantly better in HPV-positive patients, at 43.7 months versus 29.8 months (P =.009) respectively, reported Shanmugarajah Rajendra, MD, from Bankstown-Lincombe Hospital in Sydney and colleagues.

“If these findings of a favorable prognosis of HPV-positive HGD and EAC are confirmed in larger cohorts with more advanced disease, it presents an opportunity for treatment de-escalation in the hope of reducing toxic effects without deleteriously affecting survival,” they wrote in JAMA Network Open.

The findings support those of earlier studies suggesting that HPV infection is associated with better prognosis among patients with other cancers of the head and neck. For example, a retrospective analysis of data from two clinical trials reported in 2014 found that, 2 years after a diagnosis of recurrent oropharyngeal cancer, 54.6% of HPV-positive patients were alive, compared with 27.6% of HPV-negative patients (P less than .001).

To determine whether there was a similar association between HPV infection and better prognosis of Barrett HGD or EAC, Dr. Rajendra and associates conducted a retrospective case-control study of 142 patients with HGD or EAC treated at secondary or tertiary referral centers in Australia. The patients, all of whom were white, included 126 men. The mean age was 66 years, and in all, 37 patients were positive for HPV.

As noted before, both DFS and overall survival were significantly better for HPV-infected patients, with mean differences of 16.2 months and 13.9 months, respectively. HPV-positive patients also had lower rates of progression or recurrence (24.3% vs. 58.1%; P less than .001), distant metastases (8.1% vs. 27.6%; P = .02), and death from EAC (13.5% vs. 36.2%; P = .02).

In multivariate analysis, superior DFS was associated with HPV positivity, (hazard ratio, 0.39; P = .02), biologically active virus (HR, 0.36; P = .02), E6 and E7 messenger RNA (HR, 0.36; P = .04), and with high p16 expression (HR, 0.49; P = .02).

The study was supported by the South Western Sydney Clinical School; the University of New South Wales, Sydney; and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund. Dr. Rajendra reported grants from the University of New South Wales and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Rajendra S et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Aug 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1054.

Patients with Barrett high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma who are positive for human papillomavirus (HPV) infection have significantly better outcomes than patients with the same diseases who are negative for HPV, investigators report.

Among patients with Barrett high-grade dysplasia (HGD) or esophageal adenocarcinoma (EAC), mean disease-free survival (DFS) was 40.3 months for HPV-positive patients, compared with 24.1 months for HPV-negative patients (P = .003). Mean overall survival was also significantly better in HPV-positive patients, at 43.7 months versus 29.8 months (P =.009) respectively, reported Shanmugarajah Rajendra, MD, from Bankstown-Lincombe Hospital in Sydney and colleagues.

“If these findings of a favorable prognosis of HPV-positive HGD and EAC are confirmed in larger cohorts with more advanced disease, it presents an opportunity for treatment de-escalation in the hope of reducing toxic effects without deleteriously affecting survival,” they wrote in JAMA Network Open.

The findings support those of earlier studies suggesting that HPV infection is associated with better prognosis among patients with other cancers of the head and neck. For example, a retrospective analysis of data from two clinical trials reported in 2014 found that, 2 years after a diagnosis of recurrent oropharyngeal cancer, 54.6% of HPV-positive patients were alive, compared with 27.6% of HPV-negative patients (P less than .001).

To determine whether there was a similar association between HPV infection and better prognosis of Barrett HGD or EAC, Dr. Rajendra and associates conducted a retrospective case-control study of 142 patients with HGD or EAC treated at secondary or tertiary referral centers in Australia. The patients, all of whom were white, included 126 men. The mean age was 66 years, and in all, 37 patients were positive for HPV.

As noted before, both DFS and overall survival were significantly better for HPV-infected patients, with mean differences of 16.2 months and 13.9 months, respectively. HPV-positive patients also had lower rates of progression or recurrence (24.3% vs. 58.1%; P less than .001), distant metastases (8.1% vs. 27.6%; P = .02), and death from EAC (13.5% vs. 36.2%; P = .02).

In multivariate analysis, superior DFS was associated with HPV positivity, (hazard ratio, 0.39; P = .02), biologically active virus (HR, 0.36; P = .02), E6 and E7 messenger RNA (HR, 0.36; P = .04), and with high p16 expression (HR, 0.49; P = .02).

The study was supported by the South Western Sydney Clinical School; the University of New South Wales, Sydney; and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund. Dr. Rajendra reported grants from the University of New South Wales and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

SOURCE: Rajendra S et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Aug 3. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1054.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Key clinical point: Human papillomavirus infection is associated with better outcomes for patients with esophageal adenocarcinoma and other head and neck cancers.

Major finding: Mean disease-free survival was 40.3 months for HPV-positive patients versus 24.1 months for HPV-negative patients (P = .003).

Study details: A retrospective case-control study of 142 patients with Barrett high-grade dysplasia or esophageal adenocarcinoma.

Disclosures: The study was supported by the South Western Sydney Clinical School; the University of New South Wales, Sydney; and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund. Dr. Rajendra reported grants from University of New South Wales and the Oesophageal Cancer Research Fund during the conduct of the study. No other disclosures were reported.

Source: Rajendra S et al. JAMA Network Open. 2018 Aug 3. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.1054.

A Rational Approach to Starting, Stopping, and Switching DMTs

Dr. Patricia Coyle’s Donald Paty Memorial Lecture covered current controversies in DMT use.

NASHVILLE—What guides decisions to start, stop, switch, or restart disease-modifying therapy (DMT) in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS)—particularly in the absence of extensive robust data? Because multiple treatment options exist, there is a higher bar for a DMT to be considered successful. Clinicians need to base individualized decisions on the best available evidence, according to a presentation at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting.

“We have practice guidelines, but unfortunately they are almost always out of date,” said Patricia K. Coyle, MD, Professor and Vice Chair of Clinical Affairs and Director of the MS Comprehensive Care Center at Stony Brook University Hospital in New York. “Guidelines have a lot of good things to say and several things that I would not quite agree with, but at least they are a helpful start. In the future, as we use cooperative studies, databases, and meaningful observations on large numbers of patients with MS to maximize our information and data, we will ultimately resolve all of these DMT debates.”

Starting Treatment

Controversies surrounding initiation of DMTs include whether to treat patients with radiologically isolated syndrome, when to start treating relapsing forms of MS that are not active, and, in patients with primary progressive MS, when the monoclonal agent ocrelizumab is appropriate. Current American Academy of Neurology (AAN) practice guidelines recommend both prescribing a DMT to patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), patients with a first attack who have at least two MRI lesions characteristic of MS, and offering DMTs to patients with relapsing forms of MS and recent attacks or MRI activity.

The AAN recommendations stem from the benefits seen with early treatment, Dr. Coyle emphasized. “There may be a critical window of opportunity in treating early,” she said. “If MS involves accumulating permanent damage to the CNS, wouldn’t you want to stop or minimize that as quickly as possible—not wait until there has already been significant injury?” Virtually all studies comparing early versus delayed treatment support early treatment—and “age probably matters.”

In a 2017 meta-analysis of 38 clinical trials that assessed disability worsening and disease progression in a total population of 28,000 subjects with MS, the authors found that DMT efficacy and impact on disability fell with advancing age. The model created from this study predicted that none of the DMTs would be efficacious on disability in patients older than 53. Evidence also suggested that, after patients reached age 40.5, high-efficacy DMTs (eg, ocrelizumab, natalizumab) no longer outperformed lower-efficacy oral agents (fingolimod, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate) or injectables (interferon betas and glatiramer acetates).

While skeptical of this latter finding, Dr. Coyle termed it “provocative” because it demonstrates that patients should be treated at a younger age. “When MS declares itself, the disease has probably existed for years, damaging CNS tissue,” she said. Older age at onset probably means that the disease has been present but silent for a long period of time. In addition, CNS and brain reserve become increasingly impaired with age. “The older you are, in theory, the less CNS reserve you have.”

Stopping Treatment

Potential reasons for stopping DMT include relapsing MS or CIS that has been inactive for years; secondary progressive MS that is distant from the relapsing phase and now in a purely neurodegenerative one; age older than 60; and pregnancy.

Citing just a handful of studies in this area, Dr. Coyle pointed to the MSBase Registry of patients with relapsing MS who, on injectables, had no relapse for five years or more. Among 485 patients who stopped DMT versus 854 who continued treatment, time to relapse was similar but time to confirmed disability was shorter in those who stopped treatment. Those who stopped treatment also had an increased risk for entering the progressive stage. In another study of two cohorts who stopped DMT, 11.7% of patients with secondary progressive MS who were stable for two to 20 years, versus 58.8% of patients with relapsing MS, had acute disease within one to two years. The authors noted the secondary progressive MS cohort was older with higher EDSS scores. A retrospective review of patients with MS older than 60 who had been on DMT for more than two years showed that, of the 29.7% who stopped DMT, only one relapsed and just 10.7% reinitiated DMT.

“I would not stop a well-tolerated DMT in relapsing MS,” said Dr. Coyle. “I would continue DMT in CIS if patients were at high risk, even if they had had no disease activity for years. I would discuss stopping therapy in patients with secondary progressive MS who were older than 60, and in very debilitated patients with progressive MS.”

Switching DMTs

In terms of switching, a suboptimal response is likely magnified by delaying therapy, not matching patients well to their initial DMT, and not identifying poor response quickly,” said Dr. Coyle.

Reasons to switch include breakthrough activity—ie, the minimal evidence of disease activity (MEDA) or no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) target not met; MRI activity; poor tolerability; and abnormal laboratory data or clinical complications. Clinicians should consult the AAN practice guidelines for recommendations on when and which DMTs to switch.

Dr. Coyle again cited the MSBase Registry, in which three studies were conducted involving patients with MS who were on interferon beta or glatiramer acetate who had breakthrough attacks or disability. “In one study they switched them to another injectable or fingolimod,” she said. “They did better if they got to fingolimod. Another study involved switching to another injectable or natalizumab. They did better if they were on natalizumab. A third study looked at switching to fingolimod or natalizumab. They did better with natalizumab.”

Dr. Coyle observed that the first one to two years after initiating DMT may be the most important for determining whether a patient is doing well. “A DMT takes a few months to be fully operational,” she said. “If you are switching for breakthrough activity, you need to go to a higher-efficacy DMT. My treat-to target is not NEDA, it is MEDA.”

—Fred Balzac

Suggested Reading

Berkovich R. Clinical and MRI outcomes after stopping or switching disease-modifying therapy in stable MS patients: a case series report. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;17:123-127.

Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in nonrelapsing multiple sclerosis: experience from a clinical practice. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(1):11-14.

Coyle PK. Switching therapies in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(4):239-247.

Hua LH, Fan TH, Conway D, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler. 2018 Mar 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Kappos L, Radue EW, Comi G, et al, for the TOFINGO study group. Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in RRMS. Neurology. 2015;85(1):29-39.

Kister I, Spelman T, Alroughani R, et al, for the MSBase Study Group. Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in MS after a prolonged relapse-free period: a propensity score-matched study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1133-1137.

Maillart E, Vidal JS, Brassat D, et al. Natalizumab-PML survivors with subsequent MS treatment: clinico-radiologic outcome. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(3):e346.

Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-788.

Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, et al. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577.

Dr. Patricia Coyle’s Donald Paty Memorial Lecture covered current controversies in DMT use.

Dr. Patricia Coyle’s Donald Paty Memorial Lecture covered current controversies in DMT use.

NASHVILLE—What guides decisions to start, stop, switch, or restart disease-modifying therapy (DMT) in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS)—particularly in the absence of extensive robust data? Because multiple treatment options exist, there is a higher bar for a DMT to be considered successful. Clinicians need to base individualized decisions on the best available evidence, according to a presentation at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting.

“We have practice guidelines, but unfortunately they are almost always out of date,” said Patricia K. Coyle, MD, Professor and Vice Chair of Clinical Affairs and Director of the MS Comprehensive Care Center at Stony Brook University Hospital in New York. “Guidelines have a lot of good things to say and several things that I would not quite agree with, but at least they are a helpful start. In the future, as we use cooperative studies, databases, and meaningful observations on large numbers of patients with MS to maximize our information and data, we will ultimately resolve all of these DMT debates.”

Starting Treatment

Controversies surrounding initiation of DMTs include whether to treat patients with radiologically isolated syndrome, when to start treating relapsing forms of MS that are not active, and, in patients with primary progressive MS, when the monoclonal agent ocrelizumab is appropriate. Current American Academy of Neurology (AAN) practice guidelines recommend both prescribing a DMT to patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), patients with a first attack who have at least two MRI lesions characteristic of MS, and offering DMTs to patients with relapsing forms of MS and recent attacks or MRI activity.

The AAN recommendations stem from the benefits seen with early treatment, Dr. Coyle emphasized. “There may be a critical window of opportunity in treating early,” she said. “If MS involves accumulating permanent damage to the CNS, wouldn’t you want to stop or minimize that as quickly as possible—not wait until there has already been significant injury?” Virtually all studies comparing early versus delayed treatment support early treatment—and “age probably matters.”

In a 2017 meta-analysis of 38 clinical trials that assessed disability worsening and disease progression in a total population of 28,000 subjects with MS, the authors found that DMT efficacy and impact on disability fell with advancing age. The model created from this study predicted that none of the DMTs would be efficacious on disability in patients older than 53. Evidence also suggested that, after patients reached age 40.5, high-efficacy DMTs (eg, ocrelizumab, natalizumab) no longer outperformed lower-efficacy oral agents (fingolimod, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate) or injectables (interferon betas and glatiramer acetates).

While skeptical of this latter finding, Dr. Coyle termed it “provocative” because it demonstrates that patients should be treated at a younger age. “When MS declares itself, the disease has probably existed for years, damaging CNS tissue,” she said. Older age at onset probably means that the disease has been present but silent for a long period of time. In addition, CNS and brain reserve become increasingly impaired with age. “The older you are, in theory, the less CNS reserve you have.”

Stopping Treatment

Potential reasons for stopping DMT include relapsing MS or CIS that has been inactive for years; secondary progressive MS that is distant from the relapsing phase and now in a purely neurodegenerative one; age older than 60; and pregnancy.

Citing just a handful of studies in this area, Dr. Coyle pointed to the MSBase Registry of patients with relapsing MS who, on injectables, had no relapse for five years or more. Among 485 patients who stopped DMT versus 854 who continued treatment, time to relapse was similar but time to confirmed disability was shorter in those who stopped treatment. Those who stopped treatment also had an increased risk for entering the progressive stage. In another study of two cohorts who stopped DMT, 11.7% of patients with secondary progressive MS who were stable for two to 20 years, versus 58.8% of patients with relapsing MS, had acute disease within one to two years. The authors noted the secondary progressive MS cohort was older with higher EDSS scores. A retrospective review of patients with MS older than 60 who had been on DMT for more than two years showed that, of the 29.7% who stopped DMT, only one relapsed and just 10.7% reinitiated DMT.

“I would not stop a well-tolerated DMT in relapsing MS,” said Dr. Coyle. “I would continue DMT in CIS if patients were at high risk, even if they had had no disease activity for years. I would discuss stopping therapy in patients with secondary progressive MS who were older than 60, and in very debilitated patients with progressive MS.”

Switching DMTs

In terms of switching, a suboptimal response is likely magnified by delaying therapy, not matching patients well to their initial DMT, and not identifying poor response quickly,” said Dr. Coyle.

Reasons to switch include breakthrough activity—ie, the minimal evidence of disease activity (MEDA) or no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) target not met; MRI activity; poor tolerability; and abnormal laboratory data or clinical complications. Clinicians should consult the AAN practice guidelines for recommendations on when and which DMTs to switch.

Dr. Coyle again cited the MSBase Registry, in which three studies were conducted involving patients with MS who were on interferon beta or glatiramer acetate who had breakthrough attacks or disability. “In one study they switched them to another injectable or fingolimod,” she said. “They did better if they got to fingolimod. Another study involved switching to another injectable or natalizumab. They did better if they were on natalizumab. A third study looked at switching to fingolimod or natalizumab. They did better with natalizumab.”

Dr. Coyle observed that the first one to two years after initiating DMT may be the most important for determining whether a patient is doing well. “A DMT takes a few months to be fully operational,” she said. “If you are switching for breakthrough activity, you need to go to a higher-efficacy DMT. My treat-to target is not NEDA, it is MEDA.”

—Fred Balzac

Suggested Reading

Berkovich R. Clinical and MRI outcomes after stopping or switching disease-modifying therapy in stable MS patients: a case series report. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;17:123-127.

Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in nonrelapsing multiple sclerosis: experience from a clinical practice. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(1):11-14.

Coyle PK. Switching therapies in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(4):239-247.

Hua LH, Fan TH, Conway D, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler. 2018 Mar 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Kappos L, Radue EW, Comi G, et al, for the TOFINGO study group. Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in RRMS. Neurology. 2015;85(1):29-39.

Kister I, Spelman T, Alroughani R, et al, for the MSBase Study Group. Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in MS after a prolonged relapse-free period: a propensity score-matched study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1133-1137.

Maillart E, Vidal JS, Brassat D, et al. Natalizumab-PML survivors with subsequent MS treatment: clinico-radiologic outcome. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(3):e346.

Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-788.

Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, et al. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577.

NASHVILLE—What guides decisions to start, stop, switch, or restart disease-modifying therapy (DMT) in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS)—particularly in the absence of extensive robust data? Because multiple treatment options exist, there is a higher bar for a DMT to be considered successful. Clinicians need to base individualized decisions on the best available evidence, according to a presentation at the 2018 CMSC Annual Meeting.

“We have practice guidelines, but unfortunately they are almost always out of date,” said Patricia K. Coyle, MD, Professor and Vice Chair of Clinical Affairs and Director of the MS Comprehensive Care Center at Stony Brook University Hospital in New York. “Guidelines have a lot of good things to say and several things that I would not quite agree with, but at least they are a helpful start. In the future, as we use cooperative studies, databases, and meaningful observations on large numbers of patients with MS to maximize our information and data, we will ultimately resolve all of these DMT debates.”

Starting Treatment

Controversies surrounding initiation of DMTs include whether to treat patients with radiologically isolated syndrome, when to start treating relapsing forms of MS that are not active, and, in patients with primary progressive MS, when the monoclonal agent ocrelizumab is appropriate. Current American Academy of Neurology (AAN) practice guidelines recommend both prescribing a DMT to patients with clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), patients with a first attack who have at least two MRI lesions characteristic of MS, and offering DMTs to patients with relapsing forms of MS and recent attacks or MRI activity.

The AAN recommendations stem from the benefits seen with early treatment, Dr. Coyle emphasized. “There may be a critical window of opportunity in treating early,” she said. “If MS involves accumulating permanent damage to the CNS, wouldn’t you want to stop or minimize that as quickly as possible—not wait until there has already been significant injury?” Virtually all studies comparing early versus delayed treatment support early treatment—and “age probably matters.”

In a 2017 meta-analysis of 38 clinical trials that assessed disability worsening and disease progression in a total population of 28,000 subjects with MS, the authors found that DMT efficacy and impact on disability fell with advancing age. The model created from this study predicted that none of the DMTs would be efficacious on disability in patients older than 53. Evidence also suggested that, after patients reached age 40.5, high-efficacy DMTs (eg, ocrelizumab, natalizumab) no longer outperformed lower-efficacy oral agents (fingolimod, teriflunomide, dimethyl fumarate) or injectables (interferon betas and glatiramer acetates).

While skeptical of this latter finding, Dr. Coyle termed it “provocative” because it demonstrates that patients should be treated at a younger age. “When MS declares itself, the disease has probably existed for years, damaging CNS tissue,” she said. Older age at onset probably means that the disease has been present but silent for a long period of time. In addition, CNS and brain reserve become increasingly impaired with age. “The older you are, in theory, the less CNS reserve you have.”

Stopping Treatment

Potential reasons for stopping DMT include relapsing MS or CIS that has been inactive for years; secondary progressive MS that is distant from the relapsing phase and now in a purely neurodegenerative one; age older than 60; and pregnancy.

Citing just a handful of studies in this area, Dr. Coyle pointed to the MSBase Registry of patients with relapsing MS who, on injectables, had no relapse for five years or more. Among 485 patients who stopped DMT versus 854 who continued treatment, time to relapse was similar but time to confirmed disability was shorter in those who stopped treatment. Those who stopped treatment also had an increased risk for entering the progressive stage. In another study of two cohorts who stopped DMT, 11.7% of patients with secondary progressive MS who were stable for two to 20 years, versus 58.8% of patients with relapsing MS, had acute disease within one to two years. The authors noted the secondary progressive MS cohort was older with higher EDSS scores. A retrospective review of patients with MS older than 60 who had been on DMT for more than two years showed that, of the 29.7% who stopped DMT, only one relapsed and just 10.7% reinitiated DMT.

“I would not stop a well-tolerated DMT in relapsing MS,” said Dr. Coyle. “I would continue DMT in CIS if patients were at high risk, even if they had had no disease activity for years. I would discuss stopping therapy in patients with secondary progressive MS who were older than 60, and in very debilitated patients with progressive MS.”

Switching DMTs

In terms of switching, a suboptimal response is likely magnified by delaying therapy, not matching patients well to their initial DMT, and not identifying poor response quickly,” said Dr. Coyle.

Reasons to switch include breakthrough activity—ie, the minimal evidence of disease activity (MEDA) or no evidence of disease activity (NEDA) target not met; MRI activity; poor tolerability; and abnormal laboratory data or clinical complications. Clinicians should consult the AAN practice guidelines for recommendations on when and which DMTs to switch.

Dr. Coyle again cited the MSBase Registry, in which three studies were conducted involving patients with MS who were on interferon beta or glatiramer acetate who had breakthrough attacks or disability. “In one study they switched them to another injectable or fingolimod,” she said. “They did better if they got to fingolimod. Another study involved switching to another injectable or natalizumab. They did better if they were on natalizumab. A third study looked at switching to fingolimod or natalizumab. They did better with natalizumab.”

Dr. Coyle observed that the first one to two years after initiating DMT may be the most important for determining whether a patient is doing well. “A DMT takes a few months to be fully operational,” she said. “If you are switching for breakthrough activity, you need to go to a higher-efficacy DMT. My treat-to target is not NEDA, it is MEDA.”

—Fred Balzac

Suggested Reading

Berkovich R. Clinical and MRI outcomes after stopping or switching disease-modifying therapy in stable MS patients: a case series report. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2017;17:123-127.

Birnbaum G. Stopping disease-modifying therapy in nonrelapsing multiple sclerosis: experience from a clinical practice. Int J MS Care. 2017;19(1):11-14.

Coyle PK. Switching therapies in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs. 2013;27(4):239-247.

Hua LH, Fan TH, Conway D, et al. Discontinuation of disease-modifying therapy in patients with multiple sclerosis over age 60. Mult Scler. 2018 Mar 1 [Epub ahead of print].

Kappos L, Radue EW, Comi G, et al, for the TOFINGO study group. Switching from natalizumab to fingolimod: a randomized, placebo-controlled study in RRMS. Neurology. 2015;85(1):29-39.

Kister I, Spelman T, Alroughani R, et al, for the MSBase Study Group. Discontinuing disease-modifying therapy in MS after a prolonged relapse-free period: a propensity score-matched study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2016;87(10):1133-1137.

Maillart E, Vidal JS, Brassat D, et al. Natalizumab-PML survivors with subsequent MS treatment: clinico-radiologic outcome. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm. 2017;4(3):e346.

Rae-Grant A, Day GS, Marrie RA, et al. Practice guideline recommendations summary: disease-modifying therapies for adults with multiple sclerosis: Report of the Guideline Development, Dissemination, and Implementation Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2018;90(17):777-788.

Weideman AM, Tapia-Maltos MA, Johnson K, et al. Meta-analysis of the age-dependent efficacy of multiple sclerosis treatments. Front Neurol. 2017;8:577.

Study offers snapshot of esophageal strictures in EB patients

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – and direct visualization of these strictures is the preferred method of diagnosis. Those are key findings from a multicenter study that lead author Elena Pope, MD, discussed at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

According to Dr. Pope, who heads the section of dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, an estimated 10%-17% of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) patients experience strictures, with an overrepresentation in the recessive dystrophic EB subtype in up to 80% of cases. The risk increases with age. “What remains unknown is the best short- and long-term intervention to manage the strictures and predictors/associations for stricture-free episodes,” Dr. Pope said. “The objectives of the current study were to determine the prevalence and predisposing factors for strictures in EB, management options, patient outcomes, and predictors for recurrences and stricture-free intervals.”

She and her associates at seven centers worldwide collected data on 125 EB patients who experienced at least one episode of esophageal stricture. Data was analyzed descriptively and with ANOVA regression analysis for associations/predictors for recurrences/episode-free intervals.

The researchers evaluated 497 stricture events in the 125 patients. A slight female predominance was noted (53%), and the mean age of the first episode was 12.7 years, “which is a little bit older” than the age found in previously published data, Dr. Pope said. As expected, dystrophic EB patients made up most of the sample (98.4%); of these 123 patients, recessive dystrophic EB severe generalized subtype – approaching 50% – was the most common, followed by the recessive dystrophic EB severe intermediate subtype (almost 21%), the dominant dystrophic EB generalized subtype (7%), and other types of dystrophic EB (almost 26%).

The median body mass index percentile for age was 6.3, “so these were patients who were severely malnourished, probably as a result of their strictures as well as their underlying disease,” Dr. Pope said.

As expected, dysphagia was a presenting symptom in most patients (85.5%), while 29.8% presented with inability to swallow solids. The preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%), and less commonly with barium swallow (22.3%) or with clinical symptoms alone (0.1%). The mean number of strictures was 1.69; 76.7% were located in the cervical area, 56.7% were located in the thoracic area, and 9.7% were located in the abdominal area. Most patients (76%) had lesions that were 1 cm or longer in size.

Fluoroscopy guidance was the most common method of dilatation (in 45.2% of cases), followed by retrograde endoscopy was (33%), antegrade endoscopy (19.1%), and bougienage (0.1%). General anesthesia was used in most cases (87.6%), and corticosteroids were used around the dilatation in 90.4% of patients. The mean duration of medication use was about 5 days.

As for outcomes after dilatation, 92.2% of strictures completely resolved, 3.8% were partially resolved, 3.9% were not resolved, and 2.7% had complications. The median interval between dilatations was 7 months. Fluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation was associated with the longest esophageal stricture-free duration (mean of 13.83 months vs. 8.75 months; P less than .001), followed by retrograde endoscopy (mean of 13.10 months vs. 7.85 months; P less than .001), and antegrade endoscopy (mean of 7.63 months vs. 11.46 months; P = .024). “I think this is interesting,” said Dr. Pope, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “I think the difference occurs because if you use the endoscopy, which a rigid tube, you can potentially cause more damage, and more long-term scarring.”

Another predictor of esophageal stricture-free episodes was systemic corticosteroid use (a mean of 25.28 months vs. 10.24 months; P less than .001) around the time of the dilatation procedure. “By using systemic steroids, you’re actually decreasing some of the inflammation associated with the trauma of the procedure decreasing the chances of strictures formation,” she said.

Dr. Pope recommended that future studies evaluate the benefit of periprocedural medical interventions on increasing the intervals between esophageal stricture occurrences.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – and direct visualization of these strictures is the preferred method of diagnosis. Those are key findings from a multicenter study that lead author Elena Pope, MD, discussed at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

According to Dr. Pope, who heads the section of dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, an estimated 10%-17% of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) patients experience strictures, with an overrepresentation in the recessive dystrophic EB subtype in up to 80% of cases. The risk increases with age. “What remains unknown is the best short- and long-term intervention to manage the strictures and predictors/associations for stricture-free episodes,” Dr. Pope said. “The objectives of the current study were to determine the prevalence and predisposing factors for strictures in EB, management options, patient outcomes, and predictors for recurrences and stricture-free intervals.”

She and her associates at seven centers worldwide collected data on 125 EB patients who experienced at least one episode of esophageal stricture. Data was analyzed descriptively and with ANOVA regression analysis for associations/predictors for recurrences/episode-free intervals.

The researchers evaluated 497 stricture events in the 125 patients. A slight female predominance was noted (53%), and the mean age of the first episode was 12.7 years, “which is a little bit older” than the age found in previously published data, Dr. Pope said. As expected, dystrophic EB patients made up most of the sample (98.4%); of these 123 patients, recessive dystrophic EB severe generalized subtype – approaching 50% – was the most common, followed by the recessive dystrophic EB severe intermediate subtype (almost 21%), the dominant dystrophic EB generalized subtype (7%), and other types of dystrophic EB (almost 26%).

The median body mass index percentile for age was 6.3, “so these were patients who were severely malnourished, probably as a result of their strictures as well as their underlying disease,” Dr. Pope said.

As expected, dysphagia was a presenting symptom in most patients (85.5%), while 29.8% presented with inability to swallow solids. The preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%), and less commonly with barium swallow (22.3%) or with clinical symptoms alone (0.1%). The mean number of strictures was 1.69; 76.7% were located in the cervical area, 56.7% were located in the thoracic area, and 9.7% were located in the abdominal area. Most patients (76%) had lesions that were 1 cm or longer in size.

Fluoroscopy guidance was the most common method of dilatation (in 45.2% of cases), followed by retrograde endoscopy was (33%), antegrade endoscopy (19.1%), and bougienage (0.1%). General anesthesia was used in most cases (87.6%), and corticosteroids were used around the dilatation in 90.4% of patients. The mean duration of medication use was about 5 days.

As for outcomes after dilatation, 92.2% of strictures completely resolved, 3.8% were partially resolved, 3.9% were not resolved, and 2.7% had complications. The median interval between dilatations was 7 months. Fluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation was associated with the longest esophageal stricture-free duration (mean of 13.83 months vs. 8.75 months; P less than .001), followed by retrograde endoscopy (mean of 13.10 months vs. 7.85 months; P less than .001), and antegrade endoscopy (mean of 7.63 months vs. 11.46 months; P = .024). “I think this is interesting,” said Dr. Pope, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “I think the difference occurs because if you use the endoscopy, which a rigid tube, you can potentially cause more damage, and more long-term scarring.”

Another predictor of esophageal stricture-free episodes was systemic corticosteroid use (a mean of 25.28 months vs. 10.24 months; P less than .001) around the time of the dilatation procedure. “By using systemic steroids, you’re actually decreasing some of the inflammation associated with the trauma of the procedure decreasing the chances of strictures formation,” she said.

Dr. Pope recommended that future studies evaluate the benefit of periprocedural medical interventions on increasing the intervals between esophageal stricture occurrences.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. She reported having no financial disclosures.

LAKE TAHOE, CALIF. – and direct visualization of these strictures is the preferred method of diagnosis. Those are key findings from a multicenter study that lead author Elena Pope, MD, discussed at the annual meeting of the Society for Pediatric Dermatology.

According to Dr. Pope, who heads the section of dermatology at the Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, an estimated 10%-17% of epidermolysis bullosa (EB) patients experience strictures, with an overrepresentation in the recessive dystrophic EB subtype in up to 80% of cases. The risk increases with age. “What remains unknown is the best short- and long-term intervention to manage the strictures and predictors/associations for stricture-free episodes,” Dr. Pope said. “The objectives of the current study were to determine the prevalence and predisposing factors for strictures in EB, management options, patient outcomes, and predictors for recurrences and stricture-free intervals.”

She and her associates at seven centers worldwide collected data on 125 EB patients who experienced at least one episode of esophageal stricture. Data was analyzed descriptively and with ANOVA regression analysis for associations/predictors for recurrences/episode-free intervals.

The researchers evaluated 497 stricture events in the 125 patients. A slight female predominance was noted (53%), and the mean age of the first episode was 12.7 years, “which is a little bit older” than the age found in previously published data, Dr. Pope said. As expected, dystrophic EB patients made up most of the sample (98.4%); of these 123 patients, recessive dystrophic EB severe generalized subtype – approaching 50% – was the most common, followed by the recessive dystrophic EB severe intermediate subtype (almost 21%), the dominant dystrophic EB generalized subtype (7%), and other types of dystrophic EB (almost 26%).

The median body mass index percentile for age was 6.3, “so these were patients who were severely malnourished, probably as a result of their strictures as well as their underlying disease,” Dr. Pope said.

As expected, dysphagia was a presenting symptom in most patients (85.5%), while 29.8% presented with inability to swallow solids. The preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%), and less commonly with barium swallow (22.3%) or with clinical symptoms alone (0.1%). The mean number of strictures was 1.69; 76.7% were located in the cervical area, 56.7% were located in the thoracic area, and 9.7% were located in the abdominal area. Most patients (76%) had lesions that were 1 cm or longer in size.

Fluoroscopy guidance was the most common method of dilatation (in 45.2% of cases), followed by retrograde endoscopy was (33%), antegrade endoscopy (19.1%), and bougienage (0.1%). General anesthesia was used in most cases (87.6%), and corticosteroids were used around the dilatation in 90.4% of patients. The mean duration of medication use was about 5 days.

As for outcomes after dilatation, 92.2% of strictures completely resolved, 3.8% were partially resolved, 3.9% were not resolved, and 2.7% had complications. The median interval between dilatations was 7 months. Fluoroscopy-guided balloon dilatation was associated with the longest esophageal stricture-free duration (mean of 13.83 months vs. 8.75 months; P less than .001), followed by retrograde endoscopy (mean of 13.10 months vs. 7.85 months; P less than .001), and antegrade endoscopy (mean of 7.63 months vs. 11.46 months; P = .024). “I think this is interesting,” said Dr. Pope, who is also a professor of pediatrics at the University of Toronto. “I think the difference occurs because if you use the endoscopy, which a rigid tube, you can potentially cause more damage, and more long-term scarring.”

Another predictor of esophageal stricture-free episodes was systemic corticosteroid use (a mean of 25.28 months vs. 10.24 months; P less than .001) around the time of the dilatation procedure. “By using systemic steroids, you’re actually decreasing some of the inflammation associated with the trauma of the procedure decreasing the chances of strictures formation,” she said.

Dr. Pope recommended that future studies evaluate the benefit of periprocedural medical interventions on increasing the intervals between esophageal stricture occurrences.

The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. She reported having no financial disclosures.

REPORTING FROM SPD 2018

Key clinical point: Esophageal strictures are common complications of patients with severe types of epidermolysis bullosa.

Major finding: Most epidermolysis bullosa patients (85.5%) presented with dysphagia, while the preferred method of evaluation was video fluoroscopy (57.7%).

Study details: A multicenter study of 497 stricture events in 125 patients with epidermolysis bullosa.

Disclosures: The study was supported by an unrestricted grant from the Epidermolysis Bullosa Research Foundation. Dr. Pope reported having no financial disclosures.

More female authors than ever in cardiology journals

Also this week, valsartan recall and risk, synergy DES shines in acute MI, and incident heart failure is linked to HIV infection.

Also this week, valsartan recall and risk, synergy DES shines in acute MI, and incident heart failure is linked to HIV infection.

Also this week, valsartan recall and risk, synergy DES shines in acute MI, and incident heart failure is linked to HIV infection.

Interns Get IHS Work Experience—Virtually

Indian Health Service (IHS) is taking applications for students to “take part in enriching projects to further the IHS mission of raising the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives to the highest level.” The twist? The students can do it remotely.

The IHS is a new partner with the Virtual Federal Service, the largest virtual internship program in the world, making it the 31st federal agency to participate. Other agencies include the Peace Corps and The National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The “einterns” spend 10 hours a week from September through May working remotely. The work is unpaid, although they may get course credit. For some, it is the first time they have worked on issues affecting Native people. Those projects have included producing bilingual Navajo and English videos for rural health clinics, developing Navajo-specific health education materials on palliative care, creating a sexual assault locator map, and creating social media strategies and campaigns for health promotion.

IHS welcomed more than 15 interns, both undergraduates and graduate students, for the 2017-2018 academic year.

Indian Health Service (IHS) is taking applications for students to “take part in enriching projects to further the IHS mission of raising the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives to the highest level.” The twist? The students can do it remotely.

The IHS is a new partner with the Virtual Federal Service, the largest virtual internship program in the world, making it the 31st federal agency to participate. Other agencies include the Peace Corps and The National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The “einterns” spend 10 hours a week from September through May working remotely. The work is unpaid, although they may get course credit. For some, it is the first time they have worked on issues affecting Native people. Those projects have included producing bilingual Navajo and English videos for rural health clinics, developing Navajo-specific health education materials on palliative care, creating a sexual assault locator map, and creating social media strategies and campaigns for health promotion.

IHS welcomed more than 15 interns, both undergraduates and graduate students, for the 2017-2018 academic year.

Indian Health Service (IHS) is taking applications for students to “take part in enriching projects to further the IHS mission of raising the physical, mental, social, and spiritual health of American Indians and Alaska Natives to the highest level.” The twist? The students can do it remotely.

The IHS is a new partner with the Virtual Federal Service, the largest virtual internship program in the world, making it the 31st federal agency to participate. Other agencies include the Peace Corps and The National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

The “einterns” spend 10 hours a week from September through May working remotely. The work is unpaid, although they may get course credit. For some, it is the first time they have worked on issues affecting Native people. Those projects have included producing bilingual Navajo and English videos for rural health clinics, developing Navajo-specific health education materials on palliative care, creating a sexual assault locator map, and creating social media strategies and campaigns for health promotion.

IHS welcomed more than 15 interns, both undergraduates and graduate students, for the 2017-2018 academic year.

Work explains link between hypoxia and thrombosis

Researchers say they have discovered how hypoxia increases the risk of thrombosis.

The team noted that the cellular response to hypoxia is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1).

The researchers were able to show that HIF1 downregulates expression of protein S (PS), a natural anticoagulant, which increases the risk of thrombosis.

“Our earlier work found that PS inhibits a key clotting protein, factor IXa,” said Rinku Majumder, PhD, of LSU Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, Louisiana.

“We knew that PS deficiency could occur in hypoxia but not why. With this study, our group identified the gene regulatory mechanism by which oxygen concentration controls PS production.”

Dr Majumder and her colleagues described this discovery in a letter published in Blood.

Because PS is primarily produced in the liver, the researchers cultured human hepatocarcinoma cells in normoxic and hypoxic conditions and then measured levels of PS.

The team found that increasing hypoxia reduced PS levels and increased stability of the HIF1α subunit of HIF1. The researchers said this inverse relationship between HIF1α and PS levels suggests HIF1 might regulate PS expression, and this theory was confirmed via experiments with mice.

Dr Majumder and her colleagues pointed out that an oxygen-dependent signaling system degrades HIF1α, and oxygen deficiency prevents HIF1α degradation. The HIF1α P564A mutant (HIF1α dPA) is resistant to degradation, which results in elevated HIF1 even in normoxic conditions.

The researchers conducted experiments with knockout mice expressing HIF1α dPA in the liver, HIF1α liver-specific knockout mice, and control mice.

When compared to PS levels in liver samples from control mice (100%), PS levels were elevated in liver samples from the HIF1α liver-specific knockout mice (220%) and reduced in samples from the HIF1α dPA mice (50%).

PS messenger RNA was 2-fold higher in HIF1α knockout mice than in controls. In HIF1α dPA mice, PS messenger RNA was 0.3-fold that of controls.

PS levels in plasma from HIF1α knockout mice were double the levels of controls, while PS levels in plasma from HIF1α dPA mice were half that of controls.

Plasma from HIF1α knockout mice produced 5-fold less thrombin and plasma from HIF1α dPA mice produced 1.5-fold more thrombin than control plasma.

Subsequent experiments confirmed that the variations in thrombin generation were due to changes in plasma PS levels, the researchers said.

The team concluded that stabilization of HIF1 in the liver, which is a normal response to hypoxia, is associated with reduced PS expression. This results in lower plasma PS levels and an increased risk of thrombosis.

Researchers say they have discovered how hypoxia increases the risk of thrombosis.

The team noted that the cellular response to hypoxia is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1).

The researchers were able to show that HIF1 downregulates expression of protein S (PS), a natural anticoagulant, which increases the risk of thrombosis.

“Our earlier work found that PS inhibits a key clotting protein, factor IXa,” said Rinku Majumder, PhD, of LSU Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, Louisiana.

“We knew that PS deficiency could occur in hypoxia but not why. With this study, our group identified the gene regulatory mechanism by which oxygen concentration controls PS production.”

Dr Majumder and her colleagues described this discovery in a letter published in Blood.

Because PS is primarily produced in the liver, the researchers cultured human hepatocarcinoma cells in normoxic and hypoxic conditions and then measured levels of PS.

The team found that increasing hypoxia reduced PS levels and increased stability of the HIF1α subunit of HIF1. The researchers said this inverse relationship between HIF1α and PS levels suggests HIF1 might regulate PS expression, and this theory was confirmed via experiments with mice.

Dr Majumder and her colleagues pointed out that an oxygen-dependent signaling system degrades HIF1α, and oxygen deficiency prevents HIF1α degradation. The HIF1α P564A mutant (HIF1α dPA) is resistant to degradation, which results in elevated HIF1 even in normoxic conditions.

The researchers conducted experiments with knockout mice expressing HIF1α dPA in the liver, HIF1α liver-specific knockout mice, and control mice.

When compared to PS levels in liver samples from control mice (100%), PS levels were elevated in liver samples from the HIF1α liver-specific knockout mice (220%) and reduced in samples from the HIF1α dPA mice (50%).

PS messenger RNA was 2-fold higher in HIF1α knockout mice than in controls. In HIF1α dPA mice, PS messenger RNA was 0.3-fold that of controls.

PS levels in plasma from HIF1α knockout mice were double the levels of controls, while PS levels in plasma from HIF1α dPA mice were half that of controls.

Plasma from HIF1α knockout mice produced 5-fold less thrombin and plasma from HIF1α dPA mice produced 1.5-fold more thrombin than control plasma.

Subsequent experiments confirmed that the variations in thrombin generation were due to changes in plasma PS levels, the researchers said.

The team concluded that stabilization of HIF1 in the liver, which is a normal response to hypoxia, is associated with reduced PS expression. This results in lower plasma PS levels and an increased risk of thrombosis.

Researchers say they have discovered how hypoxia increases the risk of thrombosis.

The team noted that the cellular response to hypoxia is mediated by hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF1).

The researchers were able to show that HIF1 downregulates expression of protein S (PS), a natural anticoagulant, which increases the risk of thrombosis.

“Our earlier work found that PS inhibits a key clotting protein, factor IXa,” said Rinku Majumder, PhD, of LSU Health Sciences Center in New Orleans, Louisiana.

“We knew that PS deficiency could occur in hypoxia but not why. With this study, our group identified the gene regulatory mechanism by which oxygen concentration controls PS production.”

Dr Majumder and her colleagues described this discovery in a letter published in Blood.

Because PS is primarily produced in the liver, the researchers cultured human hepatocarcinoma cells in normoxic and hypoxic conditions and then measured levels of PS.

The team found that increasing hypoxia reduced PS levels and increased stability of the HIF1α subunit of HIF1. The researchers said this inverse relationship between HIF1α and PS levels suggests HIF1 might regulate PS expression, and this theory was confirmed via experiments with mice.

Dr Majumder and her colleagues pointed out that an oxygen-dependent signaling system degrades HIF1α, and oxygen deficiency prevents HIF1α degradation. The HIF1α P564A mutant (HIF1α dPA) is resistant to degradation, which results in elevated HIF1 even in normoxic conditions.

The researchers conducted experiments with knockout mice expressing HIF1α dPA in the liver, HIF1α liver-specific knockout mice, and control mice.

When compared to PS levels in liver samples from control mice (100%), PS levels were elevated in liver samples from the HIF1α liver-specific knockout mice (220%) and reduced in samples from the HIF1α dPA mice (50%).

PS messenger RNA was 2-fold higher in HIF1α knockout mice than in controls. In HIF1α dPA mice, PS messenger RNA was 0.3-fold that of controls.

PS levels in plasma from HIF1α knockout mice were double the levels of controls, while PS levels in plasma from HIF1α dPA mice were half that of controls.

Plasma from HIF1α knockout mice produced 5-fold less thrombin and plasma from HIF1α dPA mice produced 1.5-fold more thrombin than control plasma.

Subsequent experiments confirmed that the variations in thrombin generation were due to changes in plasma PS levels, the researchers said.

The team concluded that stabilization of HIF1 in the liver, which is a normal response to hypoxia, is associated with reduced PS expression. This results in lower plasma PS levels and an increased risk of thrombosis.

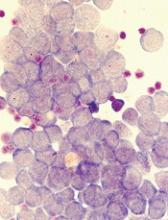

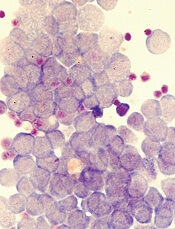

Method may enable eradication of LSCs in AML

Disrupting mitophagy may be a “promising strategy” for eliminating leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The team found that AML LSCs depend on mitophagy to maintain their “stemness,” but targeting the central metabolic stress regulator AMPK or the mitochondrial dynamics regulator FIS1 can disrupt mitophagy and impair LSC function.

Craig T. Jordan, PhD, of the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers said in vitro experiments showed that LSCs have elevated levels of FIS1 and “distinct mitochondrial morphology.”

When the team inhibited FIS1 in the AML cell line MOLM-13 and primary AML cells, they observed disruption of mitochondrial dynamics. Experiments in mouse models indicated that FIS1 is required for LSC self-renewal.

Specifically, the researchers said they found that depletion of FIS1 hinders mitophagy and leads to inactivation of GSK3, myeloid differentiation, cell-cycle arrest, and loss of LSC function.

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that AMPK is an upstream regulator of FIS1, and targeting AMPK produces similar effects as targeting FIS1—namely, disrupting mitophagy and impairing LSC self-renewal.

The researchers said their findings suggest that mitochondrial stress generated from oncogenic transformation may activate AMPK signaling in LSCs. And the AMPK signaling drives FIS1-mediated mitophagy, which eliminates stressed mitochondria and allows LSCs to thrive.

However, when AMPK or FIS1 is inhibited, the damaged mitochondria are not eliminated. This leads to “GSK3 inhibition and other unknown events” that prompt differentiation and hinder LSC function.

“Leukemia stem cells require AMPK for their survival, but normal hematopoietic cells can do without it,” Dr Jordan noted. “The reason this study is so important is that, so far, nobody’s come up with a good way to kill leukemia stem cells while sparing normal blood-forming cells. If we can translate this concept to patients, the potential for improved therapy is very exciting.”

Disrupting mitophagy may be a “promising strategy” for eliminating leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The team found that AML LSCs depend on mitophagy to maintain their “stemness,” but targeting the central metabolic stress regulator AMPK or the mitochondrial dynamics regulator FIS1 can disrupt mitophagy and impair LSC function.

Craig T. Jordan, PhD, of the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers said in vitro experiments showed that LSCs have elevated levels of FIS1 and “distinct mitochondrial morphology.”

When the team inhibited FIS1 in the AML cell line MOLM-13 and primary AML cells, they observed disruption of mitochondrial dynamics. Experiments in mouse models indicated that FIS1 is required for LSC self-renewal.

Specifically, the researchers said they found that depletion of FIS1 hinders mitophagy and leads to inactivation of GSK3, myeloid differentiation, cell-cycle arrest, and loss of LSC function.

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that AMPK is an upstream regulator of FIS1, and targeting AMPK produces similar effects as targeting FIS1—namely, disrupting mitophagy and impairing LSC self-renewal.

The researchers said their findings suggest that mitochondrial stress generated from oncogenic transformation may activate AMPK signaling in LSCs. And the AMPK signaling drives FIS1-mediated mitophagy, which eliminates stressed mitochondria and allows LSCs to thrive.

However, when AMPK or FIS1 is inhibited, the damaged mitochondria are not eliminated. This leads to “GSK3 inhibition and other unknown events” that prompt differentiation and hinder LSC function.

“Leukemia stem cells require AMPK for their survival, but normal hematopoietic cells can do without it,” Dr Jordan noted. “The reason this study is so important is that, so far, nobody’s come up with a good way to kill leukemia stem cells while sparing normal blood-forming cells. If we can translate this concept to patients, the potential for improved therapy is very exciting.”

Disrupting mitophagy may be a “promising strategy” for eliminating leukemia stem cells (LSCs) in acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to researchers.

The team found that AML LSCs depend on mitophagy to maintain their “stemness,” but targeting the central metabolic stress regulator AMPK or the mitochondrial dynamics regulator FIS1 can disrupt mitophagy and impair LSC function.

Craig T. Jordan, PhD, of the University of Colorado in Aurora, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cell Stem Cell.

The researchers said in vitro experiments showed that LSCs have elevated levels of FIS1 and “distinct mitochondrial morphology.”

When the team inhibited FIS1 in the AML cell line MOLM-13 and primary AML cells, they observed disruption of mitochondrial dynamics. Experiments in mouse models indicated that FIS1 is required for LSC self-renewal.

Specifically, the researchers said they found that depletion of FIS1 hinders mitophagy and leads to inactivation of GSK3, myeloid differentiation, cell-cycle arrest, and loss of LSC function.

Dr Jordan and his colleagues also found that AMPK is an upstream regulator of FIS1, and targeting AMPK produces similar effects as targeting FIS1—namely, disrupting mitophagy and impairing LSC self-renewal.

The researchers said their findings suggest that mitochondrial stress generated from oncogenic transformation may activate AMPK signaling in LSCs. And the AMPK signaling drives FIS1-mediated mitophagy, which eliminates stressed mitochondria and allows LSCs to thrive.

However, when AMPK or FIS1 is inhibited, the damaged mitochondria are not eliminated. This leads to “GSK3 inhibition and other unknown events” that prompt differentiation and hinder LSC function.

“Leukemia stem cells require AMPK for their survival, but normal hematopoietic cells can do without it,” Dr Jordan noted. “The reason this study is so important is that, so far, nobody’s come up with a good way to kill leukemia stem cells while sparing normal blood-forming cells. If we can translate this concept to patients, the potential for improved therapy is very exciting.”

Protein ‘atlas’ could aid study, treatment of diseases

New technology has enabled researchers to create a “genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome,” according to an article published in Nature.

The researchers identified nearly 2000 genetic associations with close to 1500 proteins, and they believe these discoveries will improve our understanding of diseases and aid drug development.

“Compared to genes, proteins have been relatively understudied in human blood, even though they are the ‘effectors’ of human biology, are disrupted in many diseases, and are the targets of most medicines,” said study author Adam Butterworth, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“Novel technologies are now allowing us to start addressing this gap in our knowledge.”

Dr Butterworth and his colleagues used an assay called SOMAscan (developed by the company SomaLogic) to measure 3622 proteins in the blood of 3301 people. The team then analyzed the DNA of these individuals to see which regions of their genomes were associated with protein levels.

In this way, the researchers found 1927 significant associations between 1478 proteins and 764 genomic regions. These findings are publicly available via the University of Cambridge website.

The researchers said one way to use this information is to identify biological pathways that cause diseases.

“Thanks to the genomics revolution over the past decade, we’ve been good at finding statistical associations between the genome and disease, but the difficulty has been then identifying the disease-causing genes and pathways,” said study author James Peters, PhD, of the University of Cambridge.

“Now, by combining our database with what we know about associations between genetic variants and disease, we are able to say a lot more about the biology of disease.”

In some cases, the researchers identified multiple genetic variants influencing levels of a protein. By combining these variants into a “score” for that protein, they were able to identify new associations between proteins and disease.

The team also said the proteomic genetic data can be used to aid drug development. In addition to highlighting potential side effects of drugs, the findings can provide insights on protein targets of new and existing drugs.

By linking drugs, proteins, genetic variation, and diseases, the researchers have already suggested existing drugs that could potentially be used to treat different diseases and increased confidence that certain drugs currently in development might be successful in clinical trials.

“Our database is really just a starting point,” said study author Benjamin Sun, an MB/PhD student at the University of Cambridge.

“We’ve given some examples in this study of how it might be used, but now it’s over to the research community to begin using it and finding new applications.”

The research was funded by MSD, National Institute for Health Research, NHS Blood and Transplant, British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, UK Research and Innovation, and SomaLogic.

New technology has enabled researchers to create a “genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome,” according to an article published in Nature.

The researchers identified nearly 2000 genetic associations with close to 1500 proteins, and they believe these discoveries will improve our understanding of diseases and aid drug development.

“Compared to genes, proteins have been relatively understudied in human blood, even though they are the ‘effectors’ of human biology, are disrupted in many diseases, and are the targets of most medicines,” said study author Adam Butterworth, PhD, of the University of Cambridge in the UK.

“Novel technologies are now allowing us to start addressing this gap in our knowledge.”

Dr Butterworth and his colleagues used an assay called SOMAscan (developed by the company SomaLogic) to measure 3622 proteins in the blood of 3301 people. The team then analyzed the DNA of these individuals to see which regions of their genomes were associated with protein levels.

In this way, the researchers found 1927 significant associations between 1478 proteins and 764 genomic regions. These findings are publicly available via the University of Cambridge website.

The researchers said one way to use this information is to identify biological pathways that cause diseases.

“Thanks to the genomics revolution over the past decade, we’ve been good at finding statistical associations between the genome and disease, but the difficulty has been then identifying the disease-causing genes and pathways,” said study author James Peters, PhD, of the University of Cambridge.

“Now, by combining our database with what we know about associations between genetic variants and disease, we are able to say a lot more about the biology of disease.”

In some cases, the researchers identified multiple genetic variants influencing levels of a protein. By combining these variants into a “score” for that protein, they were able to identify new associations between proteins and disease.

The team also said the proteomic genetic data can be used to aid drug development. In addition to highlighting potential side effects of drugs, the findings can provide insights on protein targets of new and existing drugs.

By linking drugs, proteins, genetic variation, and diseases, the researchers have already suggested existing drugs that could potentially be used to treat different diseases and increased confidence that certain drugs currently in development might be successful in clinical trials.

“Our database is really just a starting point,” said study author Benjamin Sun, an MB/PhD student at the University of Cambridge.

“We’ve given some examples in this study of how it might be used, but now it’s over to the research community to begin using it and finding new applications.”

The research was funded by MSD, National Institute for Health Research, NHS Blood and Transplant, British Heart Foundation, Medical Research Council, UK Research and Innovation, and SomaLogic.

New technology has enabled researchers to create a “genomic atlas of the human plasma proteome,” according to an article published in Nature.