User login

Bell Palsy Mimics

Facial paralysis is a common medical complaint—one that has fascinated ancient and contemporary physicians alike.1 An idiopathic facial nerve paresis involving the lower motor neuron was described in 1821 by Sir Charles Bell. This entity became known as a Bell’s palsy, the hallmark of which was weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. However, not all facial paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy.

We present a case of a patient with a Bell’s palsy mimic to facilitate and guide the differential diagnosis and distinguish conditions from the classical presentation that Bell first described to the more concerning symptoms that may not be immediately obvious. Our case further underscores the importance of performing a thorough assessment to determine the presence of other neurological findings.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of right facial droop and sensation of “room spinning.” The patient stated both symptoms began approximately 36 hours prior to presentation, upon awakening.

The patient denied any headache, neck or chest pain, extremity numbness, or weakness, but stated that she felt like she was going to fall toward her right side whenever she attempted to walk. The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, for which she was taking losartan. Her surgical history was notable for a left oophorectomy secondary to an ovarian cyst. Regarding the social history, the patient admitted to smoking 90 packs of cigarettes per year, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 164/86 mm Hg: pulse, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

Physical examination revealed the patient had a right facial droop consistent with right facial palsy. She was unable to wrinkle her right forehead or fully close her right eye. There were no field cuts on confrontation. The patient’s speech was noticeable for a mild dysarthria. The motor examination revealed mild weakness of the left upper extremity and impaired right facial sensation. There were no rashes noted on the face, head, or ears. The patient had slightly impaired hearing in the right ear, which was new in onset. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Although the patient exhibited the classic signs of Bell’s palsy, including complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, inability to wrinkle the muscle of the right forehead, and inability to fully close the right eye, she also had concerning symptoms of vertigo, dysarthria, and contralateral upper extremity weakness.

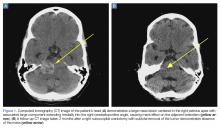

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was ordered, which revealed a large mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex, with an associated large component extending medially into the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) that caused a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem (Figures 1a and 1b).

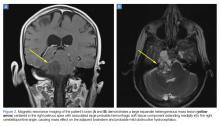

Upon these findings, the patient was transferred to another facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies performed at the receiving hospital demonstrated a large expansile heterogeneous mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex with an associated large, probable hemorrhagic soft-tissue component extending medially into the right CPA, causing a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem and mild obstructive hydrocephalus (Figures 2a and 2b).

The patient was given dexamethasone 10 mg intravenously and taken to the operating room for a right suboccipital craniotomy with subtotal tumor removal. Intraoperative high-voltage stimulation of the fifth to eighth cranial nerves showed no response, indicating significant impairment.

While there were no intraoperative complications, the patient had significant postoperative dysphagia and resultant aspiration. A tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube were subsequently placed. Results of a biopsy taken during surgery identified an atypical meningioma. The patient remained in the hospital for 4 weeks, after which she was discharged to a long-term care (LTC) and rehabilitation facility.

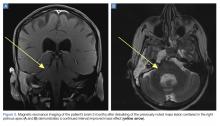

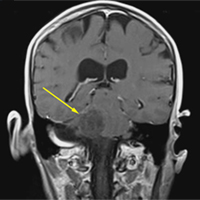

A repeat CT scan taken 2 months after surgery demonstrated absence of the previously identified large mass (Figure 1b). Three months after discharge from the LTC-rehabilitation facility, MRI of the brain showed continued interval improvement of the previously noted mass centered in the right petrous apex (Figures 3a and 3b).

Discussion

Accounts of facial paralysis and facial nerve disorders have been noted throughout history and include accounts of the condition by Hippocrates.1 Bell’s palsy was named after surgeon Sir Charles Bell, who described a peripheral-nerve paralysis of the facial nerve in 1821. Bell’s work helped to elucidate the anatomy and functional role of the facial nerve.1,2

Signs and Symptoms

The classic presentation of Bell’s palsy is weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. The eyelid on the affected side generally does not close, which can result in ocular irritation due to ineffective lubrication.

A scoring system has been developed by House and Brackmann which grades the degree impairment based on such characteristics as facial muscle function and eye closure.3,4 Approximately 96% of patients with a Bell’s palsy will improve to a House-Brackmann score of 2 or better within 1 year from diagnosis,5 and 85% of patients with Bell’s palsy will show at least some improvement within 3 weeks of onset (Table).2 Although the classic description of Bell’s palsy notes the condition as idiopathic, there is an increasing body of evidence in the literature showing a link to herpes simplex virus 1.5-7

Ramsey-Hunt Syndrome

The relationship between Bell’s palsy and Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is complex and controversial. Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is a constellation of possible complications from varicella-virus infection. Symptoms of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome include facial paralysis, tinnitus, hearing loss, vertigo, hyperacusis (increased sensitivity to certain frequencies and volume ranges of sound), and decreased ocular tearing.8 Due to the nature of symptoms associated with Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, it is apparent that the condition involves more than the seventh cranial nerve. In fact, studies have shown that Ramsey-Hunt syndrome can affect the fifth, sixth, eighth, and ninth cranial nerves.8

Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, which can present in the absence of cutaneous rash (referred to as zoster sine herpete), is estimated to occur in 8% to 20% of unilateral facial nerve palsies in adult patients.8,9 Regardless of the etiology of Bell’s palsy, a review of the literature makes it clear that facial nerve paralysis is not synonymous with Bell’s palsy.10 In one example, Yetter et al10 describe the case of a patient who, though initially diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, ultimately was found to have a facial palsy due to a parotid gland malignancy.

Likewise, Stomeo11 describes a case of a patient with facial paralysis and profound ipsilateral hearing loss who ultimately was found to have a mucoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland. In their report, the authors note that approximately 80% of facial nerve paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy, while 5% is due to malignancy.

In another report, Clemis12 describes a case in which a patient who initially was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy eventually was found to have an adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Thus, the authors appropriately emphasize in their report that “all that palsies is not Bell’s.”

Differential Diagnosis

Historical factors, including timing and duration of symptom onset, help to distinguish a Bell’s palsy from other disorders that can mimic this condition. In their study, Brach VanSwewaringen13 highlight the fact that “not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy.” In their review, the authors describe clues to help distinguish conditions that mimic Bell’s palsy. For example, maximal weakness from Bell’s Palsy typically occurs within 3 to 7 days from symptom onset, and that a more gradual onset of symptoms, with slow or negligible improvement over 6 to 12 months, is more indicative of a space-occupying lesion than Bell’s palsy.13It is, however, important to note that although the patient in our case had a central lesion, she experienced an acute onset of symptoms.

The presence of additional symptoms may also suggest an alternative diagnosis. Brach and VanSwearingen13 further noted that symptoms associated with the eighth nerve, such as vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss may be found in patients with a CPA tumor. In patients with larger tumors, ninth and 10th nerve symptoms, including the impaired hearing noted in our patient, may be present. Some patients with ninth and 10th nerve symptoms may perceive a sense of facial numbness, but actual sensory changes in the facial nerve distribution are unlikely in Bell’s palsy. Gustatory changes, however, are consistent with Bell’s palsy.

Ear pain is consistent with Bell’s palsy and is a signal to be vigilant for the possible emergence of an ear rash, which would suggest the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus along the trajectory of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Facial pain in the area of the facial nerve is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy, while hyperacusis is consistent with Bell’s palsy. Hearing loss is an eighth nerve symptom that is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy.

Similarly, there are physical examination findings that can help distinguish a true Bell’s palsy from a mimic. Changes in tear production are consistent with Bell’s palsy, but imbalance and disequilibrium are not.14

As previously noted, the patient in this case had difficulty walking and felt as if she was falling toward her right side.

One way to organize the causes of facial paralysis has been proposed by Adour et al.15 In this system, etiologies are listed as either acute paralysis or chronic, progressive paralysis. Acute paralysis (ie, the sudden onset of symptoms with maximal severity within 2 weeks), of which Bell’s palsy is the most common, can be seen in cases of polyneuritis.

A new case of Bell’s palsy has been estimated to occur in the United States every 10 minutes.8 Guillain-Barré syndrome and Lyme disease are also in this category, as is Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Patients with Lyme disease may have a history of a tick bite or rash.14

Trauma can also cause acute facial nerve paralysis (eg, blunt trauma-associated facial fracture, penetrating trauma, birth trauma). Unilateral central facial weakness can have a neurological cause, such as a lesion to the contralateral cortex, subcortical white matter, or internal capsule.2,15 Otitis media can sometimes cause facial paralysis.16 A cholesteatoma can cause acute facial paralysis.2 Malignancies cause 5% of all cases of facial paralysis. Primary parotid tumors of various types are in this category. Metastatic disease from breast, lung, skin, colon, and kidney may cause facial paralysis. As our case illustrates, CPA tumors can cause facial paralysis.15 It is important to also note that a patient can have both a Bell’s palsy and a concurrent disease. There are a number of case reports in the literature that describe acute onset of facial paralysis as a presenting symptom of malignancy.17 In addition, there are cases wherein a neurological finding on imaging, such as an acoustic neuroma, was presumed to be the cause of facial paralysis, yet the patient’s symptoms resolved in a manner consistent with Bell’s palsy.18

For example, Lagman et al19 described a patient in which a CPA lipoma was presumed to be the cause of the facial paralysis, but the eventual outcome showed the lipoma to have been an incidentaloma.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates a presenting symptom of facial palsy and the presence of a CPA tumor. The presence of vertigo along with other historical and physical examination findings inconsistent with Bell’s palsy prompted the CT scan of the head. A review of the literature suggests a number of important findings in patients with facial palsy to assist the clinician in distinguishing true Bell’s palsy from other diseases that can mimic this condition. This case serves as a reminder of the need to perform a thorough and diligent workup to determine the presence or absence of other neurologic findings prior to closing on the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy.

1. Glicenstein J. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2015;60(5):347-362. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2015.05.007.

2. Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(7):997-1002.

3. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202.

4. Reitzen SD, Babb JS, Lalwani AK. Significance and reliability of the House-Brackmann grading system for regional facial nerve function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):154-158. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.021.

5. Yeo SW, Lee DH, Jun BC, Chang KH, Park YS. Analysis of prognostic factors in Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34(2):159-164. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.005.

6. Ahmed A. When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):398-401, 405.

7. Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1323-1331. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp041120.

8. Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster.Ann Neurol. 1994;35:Suppl:S62-S64.

9. Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy. Neurology. 2000;55(5):708-710.

10. Yetter MF, Ogren FP, Moore GF, Yonkers AJ. Bell’s palsy: a facial nerve paralysis diagnosis of exclusion. Nebr Med J. 1990;75(5):109-116.

11. Stomeo F. Possibilities of diagnostic errors in paralysis of the 7th cranial nerve. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1989;9(6):629-633.

12. Clemis JD. All that palsies is not Bell’s: Bell’s palsy due to adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Am J Otol. 1991;12(5):397.

13. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(7):857-859.

14. Albers JR, Tamang S. Common questions about Bell palsy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):209-212.

15. Adour KK, Hilsinger RL Jr, Callan EJ. Facial paralysis and Bell’s palsy: a protocol for differential diagnosis. Am J Otol. 1985;Suppl:68-73.

16. Morrow MJ. Bell’s palsy and herpes zoster. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(5):407-416.

17. Quesnel AM, Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA. When the bell tolls on Bell’s palsy: finding occult malignancy in acute-onset facial paralysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(5):339-342. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.003.

18. Kaushal A, Curran WJ Jr. For whom the Bell’s palsy tolls? Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(4):450-451. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000239141.22916.22.

19. Lagman C, Choy W, Lee SJ, et al. A Case of Bell’s palsy with an incidental finding of a cerebellopontine angle lipoma. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e747. doi:10.7759/cureus.747.

Facial paralysis is a common medical complaint—one that has fascinated ancient and contemporary physicians alike.1 An idiopathic facial nerve paresis involving the lower motor neuron was described in 1821 by Sir Charles Bell. This entity became known as a Bell’s palsy, the hallmark of which was weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. However, not all facial paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy.

We present a case of a patient with a Bell’s palsy mimic to facilitate and guide the differential diagnosis and distinguish conditions from the classical presentation that Bell first described to the more concerning symptoms that may not be immediately obvious. Our case further underscores the importance of performing a thorough assessment to determine the presence of other neurological findings.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of right facial droop and sensation of “room spinning.” The patient stated both symptoms began approximately 36 hours prior to presentation, upon awakening.

The patient denied any headache, neck or chest pain, extremity numbness, or weakness, but stated that she felt like she was going to fall toward her right side whenever she attempted to walk. The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, for which she was taking losartan. Her surgical history was notable for a left oophorectomy secondary to an ovarian cyst. Regarding the social history, the patient admitted to smoking 90 packs of cigarettes per year, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 164/86 mm Hg: pulse, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

Physical examination revealed the patient had a right facial droop consistent with right facial palsy. She was unable to wrinkle her right forehead or fully close her right eye. There were no field cuts on confrontation. The patient’s speech was noticeable for a mild dysarthria. The motor examination revealed mild weakness of the left upper extremity and impaired right facial sensation. There were no rashes noted on the face, head, or ears. The patient had slightly impaired hearing in the right ear, which was new in onset. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Although the patient exhibited the classic signs of Bell’s palsy, including complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, inability to wrinkle the muscle of the right forehead, and inability to fully close the right eye, she also had concerning symptoms of vertigo, dysarthria, and contralateral upper extremity weakness.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was ordered, which revealed a large mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex, with an associated large component extending medially into the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) that caused a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem (Figures 1a and 1b).

Upon these findings, the patient was transferred to another facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies performed at the receiving hospital demonstrated a large expansile heterogeneous mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex with an associated large, probable hemorrhagic soft-tissue component extending medially into the right CPA, causing a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem and mild obstructive hydrocephalus (Figures 2a and 2b).

The patient was given dexamethasone 10 mg intravenously and taken to the operating room for a right suboccipital craniotomy with subtotal tumor removal. Intraoperative high-voltage stimulation of the fifth to eighth cranial nerves showed no response, indicating significant impairment.

While there were no intraoperative complications, the patient had significant postoperative dysphagia and resultant aspiration. A tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube were subsequently placed. Results of a biopsy taken during surgery identified an atypical meningioma. The patient remained in the hospital for 4 weeks, after which she was discharged to a long-term care (LTC) and rehabilitation facility.

A repeat CT scan taken 2 months after surgery demonstrated absence of the previously identified large mass (Figure 1b). Three months after discharge from the LTC-rehabilitation facility, MRI of the brain showed continued interval improvement of the previously noted mass centered in the right petrous apex (Figures 3a and 3b).

Discussion

Accounts of facial paralysis and facial nerve disorders have been noted throughout history and include accounts of the condition by Hippocrates.1 Bell’s palsy was named after surgeon Sir Charles Bell, who described a peripheral-nerve paralysis of the facial nerve in 1821. Bell’s work helped to elucidate the anatomy and functional role of the facial nerve.1,2

Signs and Symptoms

The classic presentation of Bell’s palsy is weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. The eyelid on the affected side generally does not close, which can result in ocular irritation due to ineffective lubrication.

A scoring system has been developed by House and Brackmann which grades the degree impairment based on such characteristics as facial muscle function and eye closure.3,4 Approximately 96% of patients with a Bell’s palsy will improve to a House-Brackmann score of 2 or better within 1 year from diagnosis,5 and 85% of patients with Bell’s palsy will show at least some improvement within 3 weeks of onset (Table).2 Although the classic description of Bell’s palsy notes the condition as idiopathic, there is an increasing body of evidence in the literature showing a link to herpes simplex virus 1.5-7

Ramsey-Hunt Syndrome

The relationship between Bell’s palsy and Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is complex and controversial. Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is a constellation of possible complications from varicella-virus infection. Symptoms of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome include facial paralysis, tinnitus, hearing loss, vertigo, hyperacusis (increased sensitivity to certain frequencies and volume ranges of sound), and decreased ocular tearing.8 Due to the nature of symptoms associated with Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, it is apparent that the condition involves more than the seventh cranial nerve. In fact, studies have shown that Ramsey-Hunt syndrome can affect the fifth, sixth, eighth, and ninth cranial nerves.8

Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, which can present in the absence of cutaneous rash (referred to as zoster sine herpete), is estimated to occur in 8% to 20% of unilateral facial nerve palsies in adult patients.8,9 Regardless of the etiology of Bell’s palsy, a review of the literature makes it clear that facial nerve paralysis is not synonymous with Bell’s palsy.10 In one example, Yetter et al10 describe the case of a patient who, though initially diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, ultimately was found to have a facial palsy due to a parotid gland malignancy.

Likewise, Stomeo11 describes a case of a patient with facial paralysis and profound ipsilateral hearing loss who ultimately was found to have a mucoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland. In their report, the authors note that approximately 80% of facial nerve paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy, while 5% is due to malignancy.

In another report, Clemis12 describes a case in which a patient who initially was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy eventually was found to have an adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Thus, the authors appropriately emphasize in their report that “all that palsies is not Bell’s.”

Differential Diagnosis

Historical factors, including timing and duration of symptom onset, help to distinguish a Bell’s palsy from other disorders that can mimic this condition. In their study, Brach VanSwewaringen13 highlight the fact that “not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy.” In their review, the authors describe clues to help distinguish conditions that mimic Bell’s palsy. For example, maximal weakness from Bell’s Palsy typically occurs within 3 to 7 days from symptom onset, and that a more gradual onset of symptoms, with slow or negligible improvement over 6 to 12 months, is more indicative of a space-occupying lesion than Bell’s palsy.13It is, however, important to note that although the patient in our case had a central lesion, she experienced an acute onset of symptoms.

The presence of additional symptoms may also suggest an alternative diagnosis. Brach and VanSwearingen13 further noted that symptoms associated with the eighth nerve, such as vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss may be found in patients with a CPA tumor. In patients with larger tumors, ninth and 10th nerve symptoms, including the impaired hearing noted in our patient, may be present. Some patients with ninth and 10th nerve symptoms may perceive a sense of facial numbness, but actual sensory changes in the facial nerve distribution are unlikely in Bell’s palsy. Gustatory changes, however, are consistent with Bell’s palsy.

Ear pain is consistent with Bell’s palsy and is a signal to be vigilant for the possible emergence of an ear rash, which would suggest the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus along the trajectory of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Facial pain in the area of the facial nerve is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy, while hyperacusis is consistent with Bell’s palsy. Hearing loss is an eighth nerve symptom that is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy.

Similarly, there are physical examination findings that can help distinguish a true Bell’s palsy from a mimic. Changes in tear production are consistent with Bell’s palsy, but imbalance and disequilibrium are not.14

As previously noted, the patient in this case had difficulty walking and felt as if she was falling toward her right side.

One way to organize the causes of facial paralysis has been proposed by Adour et al.15 In this system, etiologies are listed as either acute paralysis or chronic, progressive paralysis. Acute paralysis (ie, the sudden onset of symptoms with maximal severity within 2 weeks), of which Bell’s palsy is the most common, can be seen in cases of polyneuritis.

A new case of Bell’s palsy has been estimated to occur in the United States every 10 minutes.8 Guillain-Barré syndrome and Lyme disease are also in this category, as is Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Patients with Lyme disease may have a history of a tick bite or rash.14

Trauma can also cause acute facial nerve paralysis (eg, blunt trauma-associated facial fracture, penetrating trauma, birth trauma). Unilateral central facial weakness can have a neurological cause, such as a lesion to the contralateral cortex, subcortical white matter, or internal capsule.2,15 Otitis media can sometimes cause facial paralysis.16 A cholesteatoma can cause acute facial paralysis.2 Malignancies cause 5% of all cases of facial paralysis. Primary parotid tumors of various types are in this category. Metastatic disease from breast, lung, skin, colon, and kidney may cause facial paralysis. As our case illustrates, CPA tumors can cause facial paralysis.15 It is important to also note that a patient can have both a Bell’s palsy and a concurrent disease. There are a number of case reports in the literature that describe acute onset of facial paralysis as a presenting symptom of malignancy.17 In addition, there are cases wherein a neurological finding on imaging, such as an acoustic neuroma, was presumed to be the cause of facial paralysis, yet the patient’s symptoms resolved in a manner consistent with Bell’s palsy.18

For example, Lagman et al19 described a patient in which a CPA lipoma was presumed to be the cause of the facial paralysis, but the eventual outcome showed the lipoma to have been an incidentaloma.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates a presenting symptom of facial palsy and the presence of a CPA tumor. The presence of vertigo along with other historical and physical examination findings inconsistent with Bell’s palsy prompted the CT scan of the head. A review of the literature suggests a number of important findings in patients with facial palsy to assist the clinician in distinguishing true Bell’s palsy from other diseases that can mimic this condition. This case serves as a reminder of the need to perform a thorough and diligent workup to determine the presence or absence of other neurologic findings prior to closing on the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy.

Facial paralysis is a common medical complaint—one that has fascinated ancient and contemporary physicians alike.1 An idiopathic facial nerve paresis involving the lower motor neuron was described in 1821 by Sir Charles Bell. This entity became known as a Bell’s palsy, the hallmark of which was weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. However, not all facial paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy.

We present a case of a patient with a Bell’s palsy mimic to facilitate and guide the differential diagnosis and distinguish conditions from the classical presentation that Bell first described to the more concerning symptoms that may not be immediately obvious. Our case further underscores the importance of performing a thorough assessment to determine the presence of other neurological findings.

Case

A 61-year-old woman presented to the ED for evaluation of right facial droop and sensation of “room spinning.” The patient stated both symptoms began approximately 36 hours prior to presentation, upon awakening.

The patient denied any headache, neck or chest pain, extremity numbness, or weakness, but stated that she felt like she was going to fall toward her right side whenever she attempted to walk. The patient’s medical history was significant for hypertension, for which she was taking losartan. Her surgical history was notable for a left oophorectomy secondary to an ovarian cyst. Regarding the social history, the patient admitted to smoking 90 packs of cigarettes per year, but denied alcohol or illicit drug use.

Upon arrival at the ED, the patient’s vital signs were: blood pressure, 164/86 mm Hg: pulse, 89 beats/min; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min; and temperature, 98.6°F. Oxygen saturation was 98% on room air.

Physical examination revealed the patient had a right facial droop consistent with right facial palsy. She was unable to wrinkle her right forehead or fully close her right eye. There were no field cuts on confrontation. The patient’s speech was noticeable for a mild dysarthria. The motor examination revealed mild weakness of the left upper extremity and impaired right facial sensation. There were no rashes noted on the face, head, or ears. The patient had slightly impaired hearing in the right ear, which was new in onset. The remainder of the physical examination was unremarkable.

Although the patient exhibited the classic signs of Bell’s palsy, including complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, inability to wrinkle the muscle of the right forehead, and inability to fully close the right eye, she also had concerning symptoms of vertigo, dysarthria, and contralateral upper extremity weakness.

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the head was ordered, which revealed a large mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex, with an associated large component extending medially into the right cerebellopontine angle (CPA) that caused a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem (Figures 1a and 1b).

Upon these findings, the patient was transferred to another facility for neurosurgical evaluation. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies performed at the receiving hospital demonstrated a large expansile heterogeneous mass lesion centered in the right petrous apex with an associated large, probable hemorrhagic soft-tissue component extending medially into the right CPA, causing a mass effect on the adjacent brainstem and mild obstructive hydrocephalus (Figures 2a and 2b).

The patient was given dexamethasone 10 mg intravenously and taken to the operating room for a right suboccipital craniotomy with subtotal tumor removal. Intraoperative high-voltage stimulation of the fifth to eighth cranial nerves showed no response, indicating significant impairment.

While there were no intraoperative complications, the patient had significant postoperative dysphagia and resultant aspiration. A tracheostomy and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy tube were subsequently placed. Results of a biopsy taken during surgery identified an atypical meningioma. The patient remained in the hospital for 4 weeks, after which she was discharged to a long-term care (LTC) and rehabilitation facility.

A repeat CT scan taken 2 months after surgery demonstrated absence of the previously identified large mass (Figure 1b). Three months after discharge from the LTC-rehabilitation facility, MRI of the brain showed continued interval improvement of the previously noted mass centered in the right petrous apex (Figures 3a and 3b).

Discussion

Accounts of facial paralysis and facial nerve disorders have been noted throughout history and include accounts of the condition by Hippocrates.1 Bell’s palsy was named after surgeon Sir Charles Bell, who described a peripheral-nerve paralysis of the facial nerve in 1821. Bell’s work helped to elucidate the anatomy and functional role of the facial nerve.1,2

Signs and Symptoms

The classic presentation of Bell’s palsy is weakness or complete paralysis of the muscles of one side of the face, with no sparing of the muscles of the forehead. The eyelid on the affected side generally does not close, which can result in ocular irritation due to ineffective lubrication.

A scoring system has been developed by House and Brackmann which grades the degree impairment based on such characteristics as facial muscle function and eye closure.3,4 Approximately 96% of patients with a Bell’s palsy will improve to a House-Brackmann score of 2 or better within 1 year from diagnosis,5 and 85% of patients with Bell’s palsy will show at least some improvement within 3 weeks of onset (Table).2 Although the classic description of Bell’s palsy notes the condition as idiopathic, there is an increasing body of evidence in the literature showing a link to herpes simplex virus 1.5-7

Ramsey-Hunt Syndrome

The relationship between Bell’s palsy and Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is complex and controversial. Ramsey-Hunt syndrome is a constellation of possible complications from varicella-virus infection. Symptoms of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome include facial paralysis, tinnitus, hearing loss, vertigo, hyperacusis (increased sensitivity to certain frequencies and volume ranges of sound), and decreased ocular tearing.8 Due to the nature of symptoms associated with Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, it is apparent that the condition involves more than the seventh cranial nerve. In fact, studies have shown that Ramsey-Hunt syndrome can affect the fifth, sixth, eighth, and ninth cranial nerves.8

Ramsey-Hunt syndrome, which can present in the absence of cutaneous rash (referred to as zoster sine herpete), is estimated to occur in 8% to 20% of unilateral facial nerve palsies in adult patients.8,9 Regardless of the etiology of Bell’s palsy, a review of the literature makes it clear that facial nerve paralysis is not synonymous with Bell’s palsy.10 In one example, Yetter et al10 describe the case of a patient who, though initially diagnosed with Bell’s palsy, ultimately was found to have a facial palsy due to a parotid gland malignancy.

Likewise, Stomeo11 describes a case of a patient with facial paralysis and profound ipsilateral hearing loss who ultimately was found to have a mucoepithelial carcinoma of the parotid gland. In their report, the authors note that approximately 80% of facial nerve paralysis is due to Bell’s palsy, while 5% is due to malignancy.

In another report, Clemis12 describes a case in which a patient who initially was diagnosed with Bell’s palsy eventually was found to have an adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Thus, the authors appropriately emphasize in their report that “all that palsies is not Bell’s.”

Differential Diagnosis

Historical factors, including timing and duration of symptom onset, help to distinguish a Bell’s palsy from other disorders that can mimic this condition. In their study, Brach VanSwewaringen13 highlight the fact that “not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy.” In their review, the authors describe clues to help distinguish conditions that mimic Bell’s palsy. For example, maximal weakness from Bell’s Palsy typically occurs within 3 to 7 days from symptom onset, and that a more gradual onset of symptoms, with slow or negligible improvement over 6 to 12 months, is more indicative of a space-occupying lesion than Bell’s palsy.13It is, however, important to note that although the patient in our case had a central lesion, she experienced an acute onset of symptoms.

The presence of additional symptoms may also suggest an alternative diagnosis. Brach and VanSwearingen13 further noted that symptoms associated with the eighth nerve, such as vertigo, tinnitus, and hearing loss may be found in patients with a CPA tumor. In patients with larger tumors, ninth and 10th nerve symptoms, including the impaired hearing noted in our patient, may be present. Some patients with ninth and 10th nerve symptoms may perceive a sense of facial numbness, but actual sensory changes in the facial nerve distribution are unlikely in Bell’s palsy. Gustatory changes, however, are consistent with Bell’s palsy.

Ear pain is consistent with Bell’s palsy and is a signal to be vigilant for the possible emergence of an ear rash, which would suggest the diagnosis of herpes zoster oticus along the trajectory of Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Facial pain in the area of the facial nerve is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy, while hyperacusis is consistent with Bell’s palsy. Hearing loss is an eighth nerve symptom that is inconsistent with Bell’s palsy.

Similarly, there are physical examination findings that can help distinguish a true Bell’s palsy from a mimic. Changes in tear production are consistent with Bell’s palsy, but imbalance and disequilibrium are not.14

As previously noted, the patient in this case had difficulty walking and felt as if she was falling toward her right side.

One way to organize the causes of facial paralysis has been proposed by Adour et al.15 In this system, etiologies are listed as either acute paralysis or chronic, progressive paralysis. Acute paralysis (ie, the sudden onset of symptoms with maximal severity within 2 weeks), of which Bell’s palsy is the most common, can be seen in cases of polyneuritis.

A new case of Bell’s palsy has been estimated to occur in the United States every 10 minutes.8 Guillain-Barré syndrome and Lyme disease are also in this category, as is Ramsey-Hunt syndrome. Patients with Lyme disease may have a history of a tick bite or rash.14

Trauma can also cause acute facial nerve paralysis (eg, blunt trauma-associated facial fracture, penetrating trauma, birth trauma). Unilateral central facial weakness can have a neurological cause, such as a lesion to the contralateral cortex, subcortical white matter, or internal capsule.2,15 Otitis media can sometimes cause facial paralysis.16 A cholesteatoma can cause acute facial paralysis.2 Malignancies cause 5% of all cases of facial paralysis. Primary parotid tumors of various types are in this category. Metastatic disease from breast, lung, skin, colon, and kidney may cause facial paralysis. As our case illustrates, CPA tumors can cause facial paralysis.15 It is important to also note that a patient can have both a Bell’s palsy and a concurrent disease. There are a number of case reports in the literature that describe acute onset of facial paralysis as a presenting symptom of malignancy.17 In addition, there are cases wherein a neurological finding on imaging, such as an acoustic neuroma, was presumed to be the cause of facial paralysis, yet the patient’s symptoms resolved in a manner consistent with Bell’s palsy.18

For example, Lagman et al19 described a patient in which a CPA lipoma was presumed to be the cause of the facial paralysis, but the eventual outcome showed the lipoma to have been an incidentaloma.

Conclusion

This case demonstrates a presenting symptom of facial palsy and the presence of a CPA tumor. The presence of vertigo along with other historical and physical examination findings inconsistent with Bell’s palsy prompted the CT scan of the head. A review of the literature suggests a number of important findings in patients with facial palsy to assist the clinician in distinguishing true Bell’s palsy from other diseases that can mimic this condition. This case serves as a reminder of the need to perform a thorough and diligent workup to determine the presence or absence of other neurologic findings prior to closing on the diagnosis of Bell’s palsy.

1. Glicenstein J. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2015;60(5):347-362. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2015.05.007.

2. Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(7):997-1002.

3. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202.

4. Reitzen SD, Babb JS, Lalwani AK. Significance and reliability of the House-Brackmann grading system for regional facial nerve function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):154-158. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.021.

5. Yeo SW, Lee DH, Jun BC, Chang KH, Park YS. Analysis of prognostic factors in Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34(2):159-164. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.005.

6. Ahmed A. When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):398-401, 405.

7. Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1323-1331. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp041120.

8. Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster.Ann Neurol. 1994;35:Suppl:S62-S64.

9. Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy. Neurology. 2000;55(5):708-710.

10. Yetter MF, Ogren FP, Moore GF, Yonkers AJ. Bell’s palsy: a facial nerve paralysis diagnosis of exclusion. Nebr Med J. 1990;75(5):109-116.

11. Stomeo F. Possibilities of diagnostic errors in paralysis of the 7th cranial nerve. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1989;9(6):629-633.

12. Clemis JD. All that palsies is not Bell’s: Bell’s palsy due to adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Am J Otol. 1991;12(5):397.

13. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(7):857-859.

14. Albers JR, Tamang S. Common questions about Bell palsy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):209-212.

15. Adour KK, Hilsinger RL Jr, Callan EJ. Facial paralysis and Bell’s palsy: a protocol for differential diagnosis. Am J Otol. 1985;Suppl:68-73.

16. Morrow MJ. Bell’s palsy and herpes zoster. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(5):407-416.

17. Quesnel AM, Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA. When the bell tolls on Bell’s palsy: finding occult malignancy in acute-onset facial paralysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(5):339-342. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.003.

18. Kaushal A, Curran WJ Jr. For whom the Bell’s palsy tolls? Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(4):450-451. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000239141.22916.22.

19. Lagman C, Choy W, Lee SJ, et al. A Case of Bell’s palsy with an incidental finding of a cerebellopontine angle lipoma. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e747. doi:10.7759/cureus.747.

1. Glicenstein J. Ann Chir Plast Esthet. 2015;60(5):347-362. doi:10.1016/j.anplas.2015.05.007.

2. Tiemstra JD, Khatkhate N. Bell’s palsy: diagnosis and management. Am Fam Physician. 2007;76(7):997-1002.

3. House JW, Brackmann DE. Facial nerve grading system. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1985;93(2):146-147. doi:10.1177/019459988509300202.

4. Reitzen SD, Babb JS, Lalwani AK. Significance and reliability of the House-Brackmann grading system for regional facial nerve function. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;140(2):154-158. doi:10.1016/j.otohns.2008.11.021.

5. Yeo SW, Lee DH, Jun BC, Chang KH, Park YS. Analysis of prognostic factors in Bell’s palsy and Ramsay Hunt syndrome. Auris Nasus Larynx. 2007;34(2):159-164. doi:10.1016/j.anl.2006.09.005.

6. Ahmed A. When is facial paralysis Bell palsy? Current diagnosis and treatment. Cleve Clin J Med. 2005;72(5):398-401, 405.

7. Gilden DH. Clinical practice. Bell’s palsy. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(13):1323-1331. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp041120.

8. Adour KK. Otological complications of herpes zoster.Ann Neurol. 1994;35:Suppl:S62-S64.

9. Furuta Y, Ohtani F, Mesuda Y, Fukuda S, Inuyama Y. Early diagnosis of zoster sine herpete and antiviral therapy for the treatment of facial palsy. Neurology. 2000;55(5):708-710.

10. Yetter MF, Ogren FP, Moore GF, Yonkers AJ. Bell’s palsy: a facial nerve paralysis diagnosis of exclusion. Nebr Med J. 1990;75(5):109-116.

11. Stomeo F. Possibilities of diagnostic errors in paralysis of the 7th cranial nerve. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital. 1989;9(6):629-633.

12. Clemis JD. All that palsies is not Bell’s: Bell’s palsy due to adenoid cystic carcinoma of the parotid. Am J Otol. 1991;12(5):397.

13. Brach JS, VanSwearingen JM. Not all facial paralysis is Bell’s palsy: a case report. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;80(7):857-859.

14. Albers JR, Tamang S. Common questions about Bell palsy. Am Fam Physician. 2014;89(3):209-212.

15. Adour KK, Hilsinger RL Jr, Callan EJ. Facial paralysis and Bell’s palsy: a protocol for differential diagnosis. Am J Otol. 1985;Suppl:68-73.

16. Morrow MJ. Bell’s palsy and herpes zoster. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2000;2(5):407-416.

17. Quesnel AM, Lindsay RW, Hadlock TA. When the bell tolls on Bell’s palsy: finding occult malignancy in acute-onset facial paralysis. Am J Otolaryngol. 2010;31(5):339-342. doi:10.1016/j.amjoto.2009.04.003.

18. Kaushal A, Curran WJ Jr. For whom the Bell’s palsy tolls? Am J Clin Oncol. 2009;32(4):450-451. doi:10.1097/01.coc.0000239141.22916.22.

19. Lagman C, Choy W, Lee SJ, et al. A Case of Bell’s palsy with an incidental finding of a cerebellopontine angle lipoma. Cureus. 2016;8(8):e747. doi:10.7759/cureus.747.

2017 notches up some landmark approvals

With advances in the understanding of cellular pathways, molecular genetics, and immunology, new drugs for cancer are being released at an increasing rate. A variety of novel agents have recently become available for use, generating excitement for patients and oncologists. Keeping track of all of these new agents is increasingly challenging. This brief review will summarize some of the newest drugs, their indications, and benefits (see related article).

Therapies by tumor

Breast cancer

CDK4/6 inhibitors. The CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib was approved in 2015 for the treatment of estrogen-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, and this year, two more drugs in this class – ribociclib and abemaciclib – were approved for the treatment of hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

Ribociclib (Kisqali) 600 mg daily (3 weeks on, 1 week off) is approved for use in combination with an aromatase inhibitor. In the study on which the approval was based, there was a response rate of 53% for patients in the study group, compared with 37% for those who received aromatase inhibitor alone (progression-free survival (PFS), not reached vs 14.7 months for single-agent aromatase inhibitor).1 The occurrence of neutropenia seemed to be similar to that in patients receiving palbociclib. However, unlike with palbociclib, ribociclib requires ECG monitoring for QTc prolongation as well as monitoring of liver function tests.

Abemaciclib (Verzenio) has been approved in combination with fulvestrant as well as a monotherapy.2 PFS was 16.4 months for abemaciclib (150 mg bid in combination with fulvestrant), compared with 9.3 months for fulvestrant alone, with corresponding response rates of 48% and 21%. As monotherapy, abemaciclib 200 mg bid had a response rate of 20% with a duration of response of 8.6 months.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor neratinib (Nerlynx) was approved for extended adjuvant treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer after 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab.3 Given at 240 mg (6 tablets) daily for a year, compared with a no-treatment control arm, it demonstrated an improvement in invasive disease-free survival (DFS) at 2 years from 91.9% to 94.2%, with no difference in overall survival yet noted. It is associated with diarrhea and also requires hepatic function monitoring.

Acute myelogenous leukemia

Multiple new agents were recently approved for use in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), after decades of slow advance in new drug development.

Midostaurin (Rydapt) is an FLT3 inhibitor approved for use in combination with daunorubicin and Ara-C (cytosine arabinoside) for newly diagnosed AML with FLT3 mutations, which occur in about 30% of AML patients.4 It is given orally on days 8-21 at 50 mg bid with induction and consolidation.

In the study on which the approval was based, there was a 10% improvement in overall survival for this subset of AML patients who have a typically a worse prognosis. Event-free survival in patients in the study group was 8.2 months, compared with 3 months in the control arm patients, who did not receive the agent. The drug was also approved for aggressive systemic mastocytosis.

Enasidenib (Idhifa) has been approved for AML with an IDH2 mutation in the refractory/relapsed settings.5IDH2 mutations are present in about 20% of patients with AML. Given orally at 100 mg daily as a single agent, enasidenib was associated with a 19% complete remission rate. Patients need to be monitored for differentiation syndrome, somewhat similar to what is seen with ATRA with acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Liposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine (Vyxeos) was approved for newly diagnosed therapy- or myelodysplasia-related AML.6 This novel liposomal formulation combines two standard agents and is given intravenously on days 1, 3 and 5 over 90 minutes as daunorubicin 44 mg/m2 and cytarabine 100 mg/ m2. (For a second induction and in lower dose on consolidation cycles, it is given only on days 1 and 3). The liposomal formulation achieved a superior complete response rate compared with the standard 7+3 daunorubicin plus cytarabine regimen (38% vs 26%, respectively) and longer overall survival (9.6 versus 5.9 months) in these generally poor prognosis subsets.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) was initially approved in 2000 but withdrawn from use in 2010 after trials failed to confirm benefit and demonstrated safety concerns. It has now been re-released in a lower dose and schedule from its original label.7 This immunoconjugate of an anti-CD33 bound to calicheamicin is approved for CD33-positive AML. Given at 3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, and 7 in combination with standard daunorubicin–cytarabine induction chemotherapy, it improved event-free survival from 9.5 to 17.3 months. When administered as a single agent (6 mg/m2 on day 1 and 3 mg/m2 on day 8) in patients who were unable or unwilling to tolerate standard chemotherapy, it improved overall survival (4.9 months versus 3.6 months for best supportive care). As a single agent in relapsed AML, given at 3 mg/m2 days 1, 4, and 7 and followed by cytarabine consolidation, it was associated with a 26% complete response rate, with a median relapse-free survival of 11.6 months.

Ovarian/fallopian tube cancers

PARP inhibitors. For patients with ovarian/fallopian tube cancer, there are new indications and agents for PARP inhibition, including for patients with BRCA mutations (both somatic and germline) and those without BRCA mutations.

Olaparib (Lynparza) was previously approved only in a fourth-line setting for germline BRCA-mutated patients with advanced ovarian cancer, with a response rate of 34% with a median duration of 7.9 months. Given at 300 mg orally bid, it is now approved for use in maintenance in recurrence after response to platinum-based chemotherapy after 2 or more lines of therapy regardless of BRCA status. In this setting, progression-free survival increased to 8.4 months, compared with 4.8 months for placebo.8

Rubicarib (Rubraca) is approved for BRCA-mutated patients (either germline or somatic) with advanced ovarian cancer after two or more lines of chemotherapy.9 At 600 mg orally bid, results from phase 2 trials noted a 54% response rate, with a median duration of 9.2 months.

Niraparib (Zejula) is approved for use in maintenance in recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers after platinum-based chemotherapy.10 In patients with germline BRCA mutations, niraparib at 300 mg orally daily resulted in a PFS of 21 months, compared with 5.5 months with placebo; PFS in patients with nongermline BRCA mutations was 9.3 versus 3.9 months, respectively.

Non-small cell lung cancer with EML-4 alk translocation

Crizotinib (Xalkori) has been the mainstay for treatment of for EML4-alk translocated non-small cell lung cancer. However, alectinib (Alcensa), previously for predominantly second-line use, seems more active than crizotinib in the first-line setting, particularly in the treatment and prevention of CNS metastases.

In addition, brigantinib (Alunbrig) has been approved for patients who are intolerant/refractory to crizotinib.11 At 90 mg once daily for 7 days, then escalating to 180 mg daily, it was noted to have a 50% response rate in crizotinib failures, including in the CNS.

Ceritinib (Zykadia) was approved at 750 mg once daily for EML4 alk positive NSCLC.12 In first line it had a response rate of 73% (versus 27% for chemotherapy) with a remission duration of 23.9 months (versus 11.1 months for chemotherapy).

Therapies by drug class

PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies

Anti-PD-1 antibodies nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) are widely used for a range of tumor types. Newer approvals for pembrolizumab are for adenocarcinoma of the stomach/gastro-esophageal junction with at least 1% PD-L1 expression, and in any tumor demonstrated to be MSI-high. Newer indications for nivolumab are for bladder cancer, MSI-high colon cancer, and for hepatoma previously treated with sorafenib. The anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab (Tencentriq) is now approved for platinum-resistant metastatic lung cancer, in addition to platinum-ineligible and platinum-resistant urothelial cancer.

Avelumab (Bavencio) is an anti-PD-L1 approved for both Merkel cell and previously treated urothelial cancers at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks.13 It demonstrated a 33% response rate for Merkel cell and a 16% response rate for urothelial cancer.

Durvalumab (Imfinzi) is another anti PD-L1 antibody approved at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for previously treated urothelial cancer with a 17% response rate (RR: PD-L1 high, 26%; low, 4%).14

PI3K kinase inhibitors

Copanlisib (Aliqopa) is a PI3K inhibitor approved for relapsed follicular lymphoma in patients who have progressed after two previous lines of therapy.15 It is a 60-mg, 1-hour infusion given on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. In a phase 2 tria

BTK inhibitors

Acalabruitnib (Calquence) is approved for adults with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma. In a phase 2 trial at 100 mg orally bid, it achieved an 80% overall and 40% complete response rate.16 These response rates are higher than were seen for ibrutinib in its original phase 2 trial. The spectrum of toxicities seems similar to ibruitinib and includes bleeding, cytopenias, infection, and atrial fibrillation.

CD19 CAR-T cells

Perhaps the most exciting and novel new agents are genetically engineered autologous T cells. Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah), a chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CART) that targets CD19 is approved for refractory B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (in patients under 25 years) where the complete response rate was 83% (including patients with incomplete blood count recovery).17

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (aci-cel; Yescarta), also CD19-directed CART, is approved for adults with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma after two lines of previous therapy (specifically large-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, and transformed follicular lymphoma). Response rate was 72% (complete, 51%; partial, 21%), with a median duration of response of 9.2 months.18

1. Hortobagyi GN, Stemmer SM, Burris HA, et al. Ribociclib as first-line therapy for HR-positive, advanced breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(18):1738-1748.

2. Goetz MP, Toi M, Campone M, et al. MONARCH 3: Abemaciclib as initial therapy for advanced breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(32):3638-3646.

3. Chan A, Delaloge S, Holmes FA, et al. Neratinib after trastuzumab-based adjuvant therapy in patients with HER2-positive breast cancer (ExteNET): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016;17(3):367-377.

4. Stone RM, Mandrekar SJ, Sanford BL, et al. Midostaurin plus chemotherapy for acute myeloid leukemia with a FLT3 mutation. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(5):454-464.

5. Stein EM, DiNardo CD, Pollyea DA, et al. Enasidenib in mutant IDH2 relapsed or refractory acute myeloid leukemia. Blood. 2017 Aug 10;130(6):722-731.

6. Lancet JE, Rizzieri D, Schiller GJ, et al. Overall survival (OS) with CPX-351 versus 7+3 in older adults with newly diagnosed, therapy-related acute myeloid leukemia (tAML): subgroup analysis of a phase III study. http://ascopubs.org/doi/abs/10.1200/JCO.2017.35.15_suppl.7035. Published May 2017. Accessed November 20, 2017.

7. Appelbaum FR, Bernstein ID. Gemtuzumab ozogamicin for acute myeloid leukemia. http://www.bloodjournal.org/content/early/2017/10/11/blood-2017-09-797712?sso-checked=true. September 2017. Accessed November 20, 2017.

8. Kim G, Ison G, McKee AE, et al. FDA approval summary: olaparib monotherapy in patients with deleterious germline BRCA-mutated advanced ovarian cancer treated with three or more lines of chemotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21:4257-4261.

9. Swisher EM, Lin KK, Oza AM, et al. Rucaparib in relapsed, platinum-sensitive high-grade ovarian carcinoma (ARIEL2 part 1): an international, multicentre, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2017;18:75-87.

10. Mirza MR, Monk BJ, Herrstedt J, et al. Niraparib maintenance therapy in platinum-sensitive, recurrent ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:2154-2164.

11. Kim DW, Tiseo M, Ahn MJ, Reckamp KL, et al. Brigatinib in patients with crizotinib-refractory anaplastic lymphoma kinase-positive non-small-cell lung cancer: a randomized, multicenter phase II trial. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(22):2490-2498.

12. Soria J-C, Tan DSW, MD, Chiari R, et al. First-line ceritinib versus platinum-based chemotherapy in advanced ALK-rearranged non-small-cell lung cancer (ASCEND-4): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2017;389(10072):917-929.

13. Apolo AB, Infante JR, Balmanoukian A et al. Avelumab, an anti–programmed death-ligand 1 antibody, in patients with refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma: results from a multicenter, phase Ib study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(19):2117-2124.

14. Massard C, Gordon MS, Sharma S, et al. Safety and efficacy of durvalumab (MEDI4736), an anti–programmed cell death ligand-1 immune checkpoint inhibitor, in patients with advanced urothelial bladder cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(26):3119-3125.

15. Dreyling M, Morschhauser F, Bouabdallah K, et al. Phase II study of copanlisib, a PI3K inhibitor, in relapsed or refractory, indolent or aggressive lymphoma. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(9):2169-2178.

16. Wu J, Zhang M, Liu D. Acalabrutinib (ACP-196): a selective second-generation BTK inhibitor. https://jhoonline.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13045-016-0250-9. Published March 9, 2016. Accessed November 20, 2017.

17. Maude SL, Frey N, Shaw PA, et al. Chimeric antigen receptor T cells for sustained remissions in leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(16):1507-1517.

18. Locke FL, Neelapu SS, Bartlett NL, et al. Phase 1 results of ZUMA-1: a multicenter study of KTE-C19 anti-CD19 CAR T cell therapy in refractory aggressive lymphoma. Mol Ther. 2017;25(1):285-295.

With advances in the understanding of cellular pathways, molecular genetics, and immunology, new drugs for cancer are being released at an increasing rate. A variety of novel agents have recently become available for use, generating excitement for patients and oncologists. Keeping track of all of these new agents is increasingly challenging. This brief review will summarize some of the newest drugs, their indications, and benefits (see related article).

Therapies by tumor

Breast cancer

CDK4/6 inhibitors. The CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib was approved in 2015 for the treatment of estrogen-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, and this year, two more drugs in this class – ribociclib and abemaciclib – were approved for the treatment of hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

Ribociclib (Kisqali) 600 mg daily (3 weeks on, 1 week off) is approved for use in combination with an aromatase inhibitor. In the study on which the approval was based, there was a response rate of 53% for patients in the study group, compared with 37% for those who received aromatase inhibitor alone (progression-free survival (PFS), not reached vs 14.7 months for single-agent aromatase inhibitor).1 The occurrence of neutropenia seemed to be similar to that in patients receiving palbociclib. However, unlike with palbociclib, ribociclib requires ECG monitoring for QTc prolongation as well as monitoring of liver function tests.

Abemaciclib (Verzenio) has been approved in combination with fulvestrant as well as a monotherapy.2 PFS was 16.4 months for abemaciclib (150 mg bid in combination with fulvestrant), compared with 9.3 months for fulvestrant alone, with corresponding response rates of 48% and 21%. As monotherapy, abemaciclib 200 mg bid had a response rate of 20% with a duration of response of 8.6 months.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor neratinib (Nerlynx) was approved for extended adjuvant treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer after 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab.3 Given at 240 mg (6 tablets) daily for a year, compared with a no-treatment control arm, it demonstrated an improvement in invasive disease-free survival (DFS) at 2 years from 91.9% to 94.2%, with no difference in overall survival yet noted. It is associated with diarrhea and also requires hepatic function monitoring.

Acute myelogenous leukemia

Multiple new agents were recently approved for use in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), after decades of slow advance in new drug development.

Midostaurin (Rydapt) is an FLT3 inhibitor approved for use in combination with daunorubicin and Ara-C (cytosine arabinoside) for newly diagnosed AML with FLT3 mutations, which occur in about 30% of AML patients.4 It is given orally on days 8-21 at 50 mg bid with induction and consolidation.

In the study on which the approval was based, there was a 10% improvement in overall survival for this subset of AML patients who have a typically a worse prognosis. Event-free survival in patients in the study group was 8.2 months, compared with 3 months in the control arm patients, who did not receive the agent. The drug was also approved for aggressive systemic mastocytosis.

Enasidenib (Idhifa) has been approved for AML with an IDH2 mutation in the refractory/relapsed settings.5IDH2 mutations are present in about 20% of patients with AML. Given orally at 100 mg daily as a single agent, enasidenib was associated with a 19% complete remission rate. Patients need to be monitored for differentiation syndrome, somewhat similar to what is seen with ATRA with acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Liposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine (Vyxeos) was approved for newly diagnosed therapy- or myelodysplasia-related AML.6 This novel liposomal formulation combines two standard agents and is given intravenously on days 1, 3 and 5 over 90 minutes as daunorubicin 44 mg/m2 and cytarabine 100 mg/ m2. (For a second induction and in lower dose on consolidation cycles, it is given only on days 1 and 3). The liposomal formulation achieved a superior complete response rate compared with the standard 7+3 daunorubicin plus cytarabine regimen (38% vs 26%, respectively) and longer overall survival (9.6 versus 5.9 months) in these generally poor prognosis subsets.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) was initially approved in 2000 but withdrawn from use in 2010 after trials failed to confirm benefit and demonstrated safety concerns. It has now been re-released in a lower dose and schedule from its original label.7 This immunoconjugate of an anti-CD33 bound to calicheamicin is approved for CD33-positive AML. Given at 3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, and 7 in combination with standard daunorubicin–cytarabine induction chemotherapy, it improved event-free survival from 9.5 to 17.3 months. When administered as a single agent (6 mg/m2 on day 1 and 3 mg/m2 on day 8) in patients who were unable or unwilling to tolerate standard chemotherapy, it improved overall survival (4.9 months versus 3.6 months for best supportive care). As a single agent in relapsed AML, given at 3 mg/m2 days 1, 4, and 7 and followed by cytarabine consolidation, it was associated with a 26% complete response rate, with a median relapse-free survival of 11.6 months.

Ovarian/fallopian tube cancers

PARP inhibitors. For patients with ovarian/fallopian tube cancer, there are new indications and agents for PARP inhibition, including for patients with BRCA mutations (both somatic and germline) and those without BRCA mutations.

Olaparib (Lynparza) was previously approved only in a fourth-line setting for germline BRCA-mutated patients with advanced ovarian cancer, with a response rate of 34% with a median duration of 7.9 months. Given at 300 mg orally bid, it is now approved for use in maintenance in recurrence after response to platinum-based chemotherapy after 2 or more lines of therapy regardless of BRCA status. In this setting, progression-free survival increased to 8.4 months, compared with 4.8 months for placebo.8

Rubicarib (Rubraca) is approved for BRCA-mutated patients (either germline or somatic) with advanced ovarian cancer after two or more lines of chemotherapy.9 At 600 mg orally bid, results from phase 2 trials noted a 54% response rate, with a median duration of 9.2 months.

Niraparib (Zejula) is approved for use in maintenance in recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers after platinum-based chemotherapy.10 In patients with germline BRCA mutations, niraparib at 300 mg orally daily resulted in a PFS of 21 months, compared with 5.5 months with placebo; PFS in patients with nongermline BRCA mutations was 9.3 versus 3.9 months, respectively.

Non-small cell lung cancer with EML-4 alk translocation

Crizotinib (Xalkori) has been the mainstay for treatment of for EML4-alk translocated non-small cell lung cancer. However, alectinib (Alcensa), previously for predominantly second-line use, seems more active than crizotinib in the first-line setting, particularly in the treatment and prevention of CNS metastases.

In addition, brigantinib (Alunbrig) has been approved for patients who are intolerant/refractory to crizotinib.11 At 90 mg once daily for 7 days, then escalating to 180 mg daily, it was noted to have a 50% response rate in crizotinib failures, including in the CNS.

Ceritinib (Zykadia) was approved at 750 mg once daily for EML4 alk positive NSCLC.12 In first line it had a response rate of 73% (versus 27% for chemotherapy) with a remission duration of 23.9 months (versus 11.1 months for chemotherapy).

Therapies by drug class

PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies

Anti-PD-1 antibodies nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) are widely used for a range of tumor types. Newer approvals for pembrolizumab are for adenocarcinoma of the stomach/gastro-esophageal junction with at least 1% PD-L1 expression, and in any tumor demonstrated to be MSI-high. Newer indications for nivolumab are for bladder cancer, MSI-high colon cancer, and for hepatoma previously treated with sorafenib. The anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab (Tencentriq) is now approved for platinum-resistant metastatic lung cancer, in addition to platinum-ineligible and platinum-resistant urothelial cancer.

Avelumab (Bavencio) is an anti-PD-L1 approved for both Merkel cell and previously treated urothelial cancers at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks.13 It demonstrated a 33% response rate for Merkel cell and a 16% response rate for urothelial cancer.

Durvalumab (Imfinzi) is another anti PD-L1 antibody approved at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for previously treated urothelial cancer with a 17% response rate (RR: PD-L1 high, 26%; low, 4%).14

PI3K kinase inhibitors

Copanlisib (Aliqopa) is a PI3K inhibitor approved for relapsed follicular lymphoma in patients who have progressed after two previous lines of therapy.15 It is a 60-mg, 1-hour infusion given on days 1, 8, and 15 every 28 days. In a phase 2 tria

BTK inhibitors

Acalabruitnib (Calquence) is approved for adults with previously treated mantle cell lymphoma. In a phase 2 trial at 100 mg orally bid, it achieved an 80% overall and 40% complete response rate.16 These response rates are higher than were seen for ibrutinib in its original phase 2 trial. The spectrum of toxicities seems similar to ibruitinib and includes bleeding, cytopenias, infection, and atrial fibrillation.

CD19 CAR-T cells

Perhaps the most exciting and novel new agents are genetically engineered autologous T cells. Tisagenlecleucel (Kymriah), a chimeric antigen receptor T cell (CART) that targets CD19 is approved for refractory B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (in patients under 25 years) where the complete response rate was 83% (including patients with incomplete blood count recovery).17

Axicabtagene ciloleucel (aci-cel; Yescarta), also CD19-directed CART, is approved for adults with relapsed or refractory non-Hodgkin lymphoma after two lines of previous therapy (specifically large-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, and transformed follicular lymphoma). Response rate was 72% (complete, 51%; partial, 21%), with a median duration of response of 9.2 months.18

With advances in the understanding of cellular pathways, molecular genetics, and immunology, new drugs for cancer are being released at an increasing rate. A variety of novel agents have recently become available for use, generating excitement for patients and oncologists. Keeping track of all of these new agents is increasingly challenging. This brief review will summarize some of the newest drugs, their indications, and benefits (see related article).

Therapies by tumor

Breast cancer

CDK4/6 inhibitors. The CDK4/6 inhibitor palbociclib was approved in 2015 for the treatment of estrogen-positive, HER2-negative advanced breast cancer, and this year, two more drugs in this class – ribociclib and abemaciclib – were approved for the treatment of hormone receptor–positive breast cancer.

Ribociclib (Kisqali) 600 mg daily (3 weeks on, 1 week off) is approved for use in combination with an aromatase inhibitor. In the study on which the approval was based, there was a response rate of 53% for patients in the study group, compared with 37% for those who received aromatase inhibitor alone (progression-free survival (PFS), not reached vs 14.7 months for single-agent aromatase inhibitor).1 The occurrence of neutropenia seemed to be similar to that in patients receiving palbociclib. However, unlike with palbociclib, ribociclib requires ECG monitoring for QTc prolongation as well as monitoring of liver function tests.

Abemaciclib (Verzenio) has been approved in combination with fulvestrant as well as a monotherapy.2 PFS was 16.4 months for abemaciclib (150 mg bid in combination with fulvestrant), compared with 9.3 months for fulvestrant alone, with corresponding response rates of 48% and 21%. As monotherapy, abemaciclib 200 mg bid had a response rate of 20% with a duration of response of 8.6 months.

Tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The tyrosine kinase inhibitor neratinib (Nerlynx) was approved for extended adjuvant treatment of HER2-positive breast cancer after 1 year of adjuvant trastuzumab.3 Given at 240 mg (6 tablets) daily for a year, compared with a no-treatment control arm, it demonstrated an improvement in invasive disease-free survival (DFS) at 2 years from 91.9% to 94.2%, with no difference in overall survival yet noted. It is associated with diarrhea and also requires hepatic function monitoring.

Acute myelogenous leukemia

Multiple new agents were recently approved for use in acute myelogenous leukemia (AML), after decades of slow advance in new drug development.

Midostaurin (Rydapt) is an FLT3 inhibitor approved for use in combination with daunorubicin and Ara-C (cytosine arabinoside) for newly diagnosed AML with FLT3 mutations, which occur in about 30% of AML patients.4 It is given orally on days 8-21 at 50 mg bid with induction and consolidation.

In the study on which the approval was based, there was a 10% improvement in overall survival for this subset of AML patients who have a typically a worse prognosis. Event-free survival in patients in the study group was 8.2 months, compared with 3 months in the control arm patients, who did not receive the agent. The drug was also approved for aggressive systemic mastocytosis.

Enasidenib (Idhifa) has been approved for AML with an IDH2 mutation in the refractory/relapsed settings.5IDH2 mutations are present in about 20% of patients with AML. Given orally at 100 mg daily as a single agent, enasidenib was associated with a 19% complete remission rate. Patients need to be monitored for differentiation syndrome, somewhat similar to what is seen with ATRA with acute promyelocytic leukemia.

Liposomal daunorubicin and cytarabine (Vyxeos) was approved for newly diagnosed therapy- or myelodysplasia-related AML.6 This novel liposomal formulation combines two standard agents and is given intravenously on days 1, 3 and 5 over 90 minutes as daunorubicin 44 mg/m2 and cytarabine 100 mg/ m2. (For a second induction and in lower dose on consolidation cycles, it is given only on days 1 and 3). The liposomal formulation achieved a superior complete response rate compared with the standard 7+3 daunorubicin plus cytarabine regimen (38% vs 26%, respectively) and longer overall survival (9.6 versus 5.9 months) in these generally poor prognosis subsets.

Gemtuzumab ozogamicin (Mylotarg) was initially approved in 2000 but withdrawn from use in 2010 after trials failed to confirm benefit and demonstrated safety concerns. It has now been re-released in a lower dose and schedule from its original label.7 This immunoconjugate of an anti-CD33 bound to calicheamicin is approved for CD33-positive AML. Given at 3 mg/m2 on days 1, 4, and 7 in combination with standard daunorubicin–cytarabine induction chemotherapy, it improved event-free survival from 9.5 to 17.3 months. When administered as a single agent (6 mg/m2 on day 1 and 3 mg/m2 on day 8) in patients who were unable or unwilling to tolerate standard chemotherapy, it improved overall survival (4.9 months versus 3.6 months for best supportive care). As a single agent in relapsed AML, given at 3 mg/m2 days 1, 4, and 7 and followed by cytarabine consolidation, it was associated with a 26% complete response rate, with a median relapse-free survival of 11.6 months.

Ovarian/fallopian tube cancers

PARP inhibitors. For patients with ovarian/fallopian tube cancer, there are new indications and agents for PARP inhibition, including for patients with BRCA mutations (both somatic and germline) and those without BRCA mutations.

Olaparib (Lynparza) was previously approved only in a fourth-line setting for germline BRCA-mutated patients with advanced ovarian cancer, with a response rate of 34% with a median duration of 7.9 months. Given at 300 mg orally bid, it is now approved for use in maintenance in recurrence after response to platinum-based chemotherapy after 2 or more lines of therapy regardless of BRCA status. In this setting, progression-free survival increased to 8.4 months, compared with 4.8 months for placebo.8

Rubicarib (Rubraca) is approved for BRCA-mutated patients (either germline or somatic) with advanced ovarian cancer after two or more lines of chemotherapy.9 At 600 mg orally bid, results from phase 2 trials noted a 54% response rate, with a median duration of 9.2 months.

Niraparib (Zejula) is approved for use in maintenance in recurrent epithelial ovarian, fallopian tube, and primary peritoneal cancers after platinum-based chemotherapy.10 In patients with germline BRCA mutations, niraparib at 300 mg orally daily resulted in a PFS of 21 months, compared with 5.5 months with placebo; PFS in patients with nongermline BRCA mutations was 9.3 versus 3.9 months, respectively.

Non-small cell lung cancer with EML-4 alk translocation

Crizotinib (Xalkori) has been the mainstay for treatment of for EML4-alk translocated non-small cell lung cancer. However, alectinib (Alcensa), previously for predominantly second-line use, seems more active than crizotinib in the first-line setting, particularly in the treatment and prevention of CNS metastases.

In addition, brigantinib (Alunbrig) has been approved for patients who are intolerant/refractory to crizotinib.11 At 90 mg once daily for 7 days, then escalating to 180 mg daily, it was noted to have a 50% response rate in crizotinib failures, including in the CNS.

Ceritinib (Zykadia) was approved at 750 mg once daily for EML4 alk positive NSCLC.12 In first line it had a response rate of 73% (versus 27% for chemotherapy) with a remission duration of 23.9 months (versus 11.1 months for chemotherapy).

Therapies by drug class

PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies

Anti-PD-1 antibodies nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda) are widely used for a range of tumor types. Newer approvals for pembrolizumab are for adenocarcinoma of the stomach/gastro-esophageal junction with at least 1% PD-L1 expression, and in any tumor demonstrated to be MSI-high. Newer indications for nivolumab are for bladder cancer, MSI-high colon cancer, and for hepatoma previously treated with sorafenib. The anti-PD-L1 antibody atezolizumab (Tencentriq) is now approved for platinum-resistant metastatic lung cancer, in addition to platinum-ineligible and platinum-resistant urothelial cancer.

Avelumab (Bavencio) is an anti-PD-L1 approved for both Merkel cell and previously treated urothelial cancers at a dose of 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks.13 It demonstrated a 33% response rate for Merkel cell and a 16% response rate for urothelial cancer.

Durvalumab (Imfinzi) is another anti PD-L1 antibody approved at 10 mg/kg every 2 weeks for previously treated urothelial cancer with a 17% response rate (RR: PD-L1 high, 26%; low, 4%).14

PI3K kinase inhibitors