User login

Lower socioeconomic status linked with poor NSCLC prognosis in those with pretreatment weight loss

, in a retrospective review of medical records.

Investigators identified 1,366 patients with NSCLC who had been consecutively treated at a tertiary care health system between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2013, and obtained their insurance status from an institutional tumor registry.

Cancer-associated weight loss was present at the time of diagnosis in 30% of the patients. Among those patients with pretreatment weight loss, uninsured patients had worse survival compared with those who had private insurance (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.35). However, no association was found for patients without pretreatment weight loss, wrote Steven Lau, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his associates. The report was published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

After the researchers controlled for other prognostic factors, Medicaid insurance (odds ratio, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.42-3.30) and lack of insurance (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.50-3.58) were independently associated with pretreatment weight loss.

“Patients with NSCLC of lower SES as measured by primary payer are disproportionately affected by cancer-associated weight loss, which in turn is prognostic of diminished survival ... These findings suggest early recognition and management of cachexia, even at the time of cancer diagnosis, could result in improved survival,” Dr. Lau and his associates concluded.

The study was supported in part by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grants TL1TR001104 and UL1TR001105. Dr. Lau reported employment with LabCorp by an immediate family member. Coauthors reported financial ties to Advenchen Laboratories, Macrogen, Peregrine Pharmaceuticals, and DFINE.

SOURCE: Lau S et al. J Oncol Pract. 2018 Mar 20. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025239

, in a retrospective review of medical records.

Investigators identified 1,366 patients with NSCLC who had been consecutively treated at a tertiary care health system between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2013, and obtained their insurance status from an institutional tumor registry.

Cancer-associated weight loss was present at the time of diagnosis in 30% of the patients. Among those patients with pretreatment weight loss, uninsured patients had worse survival compared with those who had private insurance (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.35). However, no association was found for patients without pretreatment weight loss, wrote Steven Lau, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his associates. The report was published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

After the researchers controlled for other prognostic factors, Medicaid insurance (odds ratio, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.42-3.30) and lack of insurance (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.50-3.58) were independently associated with pretreatment weight loss.

“Patients with NSCLC of lower SES as measured by primary payer are disproportionately affected by cancer-associated weight loss, which in turn is prognostic of diminished survival ... These findings suggest early recognition and management of cachexia, even at the time of cancer diagnosis, could result in improved survival,” Dr. Lau and his associates concluded.

The study was supported in part by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grants TL1TR001104 and UL1TR001105. Dr. Lau reported employment with LabCorp by an immediate family member. Coauthors reported financial ties to Advenchen Laboratories, Macrogen, Peregrine Pharmaceuticals, and DFINE.

SOURCE: Lau S et al. J Oncol Pract. 2018 Mar 20. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025239

, in a retrospective review of medical records.

Investigators identified 1,366 patients with NSCLC who had been consecutively treated at a tertiary care health system between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2013, and obtained their insurance status from an institutional tumor registry.

Cancer-associated weight loss was present at the time of diagnosis in 30% of the patients. Among those patients with pretreatment weight loss, uninsured patients had worse survival compared with those who had private insurance (hazard ratio, 1.63; 95% confidence interval, 1.14-2.35). However, no association was found for patients without pretreatment weight loss, wrote Steven Lau, MD, of the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and his associates. The report was published in the Journal of Oncology Practice.

After the researchers controlled for other prognostic factors, Medicaid insurance (odds ratio, 2.17; 95% CI, 1.42-3.30) and lack of insurance (OR, 2.32; 95% CI, 1.50-3.58) were independently associated with pretreatment weight loss.

“Patients with NSCLC of lower SES as measured by primary payer are disproportionately affected by cancer-associated weight loss, which in turn is prognostic of diminished survival ... These findings suggest early recognition and management of cachexia, even at the time of cancer diagnosis, could result in improved survival,” Dr. Lau and his associates concluded.

The study was supported in part by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grants TL1TR001104 and UL1TR001105. Dr. Lau reported employment with LabCorp by an immediate family member. Coauthors reported financial ties to Advenchen Laboratories, Macrogen, Peregrine Pharmaceuticals, and DFINE.

SOURCE: Lau S et al. J Oncol Pract. 2018 Mar 20. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025239

FROM JOURNAL OF ONCOLOGY PRACTICE

Key clinical point: Early recognition and management of cancer-associated weight loss in patients with NSCLC and low socioeconomic status may improve outcomes.

Major finding: Lack of insurance was significantly prognostic among patients with NSCLC and pretreatment weight loss (hazard ratio, 1.63 95% CI, 1.14-2.35).

Study details: 1,366 adult patients with NSCLC consecutively treated at a tertiary care health system between Jan. 1, 2006, and Dec. 31, 2013.

Disclosures: The study was supported in part by National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences grants TL1TR001104 and UL1TR001105. Dr. Lau reported employment with LabCorp by an immediate family member. Coauthors reported financial ties to Advenchen Laboratories, Macrogen, Peregrine Pharmaceuticals, and DFINE.

Source: Lau S et al. J Oncol Pract. 2018 Mar 20. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2017.025239.

Glenoid Bone Loss in Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty Treated with Bone Graft Techniques

ABSTRACT

The reverse shoulder arthroplasty facilitates surgical treatment of primary and revision shoulder with rotator cuff and bone deficiencies. Wear pattern classifications and a logical treatment approach for glenoid bone loss enable the surgeon to address a difficult series of problems in the reconstructions where the glenoid might not otherwise be able to support the implants. Bone grafting using the native humeral head in primary cases, and in revision cases, iliac crest are the most reliable sources for structural grafts for the worn or deficient glenoid vault.

Continue to: The reverse shoulder arthroplasty...

The reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) technique was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and introduced to the US market in 2004. It has been a successful addition to the treatment of shoulder pathologies with bone and rotator cuff loss. Its indications have expanded from treatment of very elderly patients with rotator cuff deficiencies to now include younger patients with humeral and glenoid bone loss, arthritis, soft-tissue losses, fractures, instability, and revision arthroplasty. Many of these conditions, when not adequately addressed with anatomic arthroplasty, now have viable treatment options for newer complex and successful reconstructions.

Glenoid bone deficiencies offer unique challenges for successful arthroplasty management. Basing treatment on bone loss classifications permits meaningful evaluation of these surgical options and whether they might be carried out in 1- or 2-stage reconstructions. An underlying premise is that restoration of the glenoid joint line and version assist in final stability, power, and functional results. For this purpose, bone graft options, or augmented implants are beneficial. This review covers the bone grafting options for autografts and allografts for deficient glenoids in reverse shoulder arthroplasty reconstructions.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

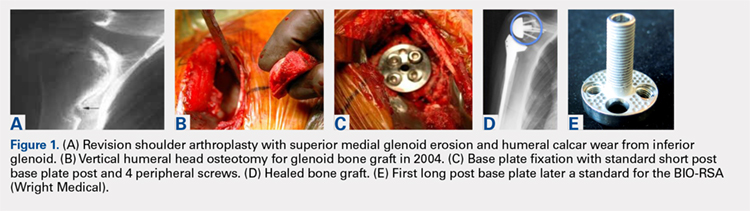

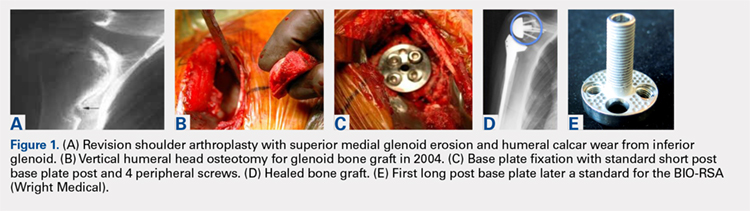

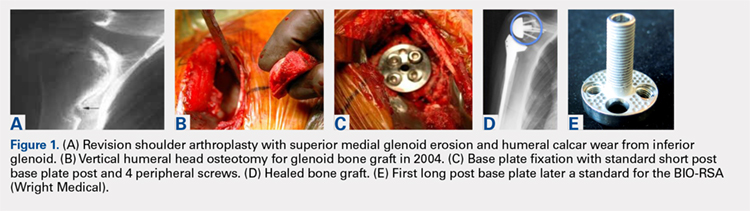

For patients without prior arthroplasty, the humeral head is available for bone grafting the glenoid bone deficits. Favard and Hamada have described vertical glenoid classifications for uneven glenoid bone loss applicable to cuff tear arthropathy and inflammatory arthritis patients.1,2 The more severe E3 superior and medial bone loss is ideally addressed with the humeral head. An early example in 2004 confirmed that this was a good indication for glenoid bone grafting and using the reverse shoulder in these advanced cases (Figures 1A-1E).

In this case, it was noted that with bone grafts the base plate post did not engage the native scapula glenoid vault. Given that the on-growth central post was the strongest part of the fixation, it was fortunate that this healed. The need for a longer post with bone grafts was recognized. Laurent Comtat with the Wright Medical company accommodated the author’s request to develop the first 25- and 30-mm-long posts to allow better fixation and on-growth potential when used with bone grafts.

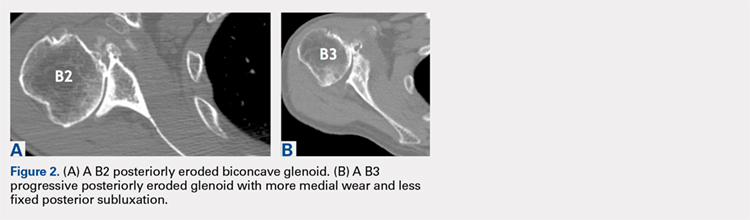

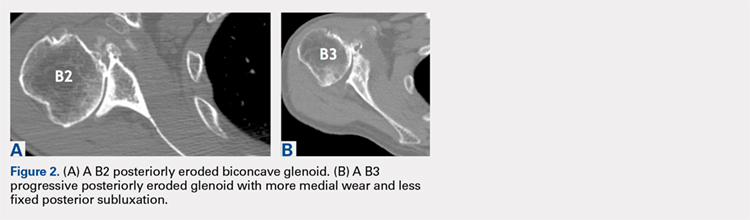

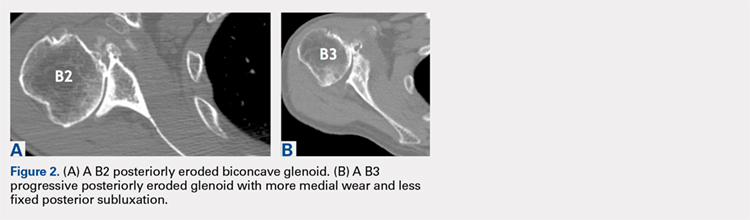

Gilles Walch’s classification addresses arthritic central and horizontal bone loss.3,4 Considerations relevant in RSA include the severe A2 central bone loss found in inflammatory arthritis and the B2, B3, and C patterns with posterior bone loss seen in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and congenital dysplasia5,6 as seen in Figures 2A, 2B. The 3-dimensional (3-D) computed tomography (CT) scan is considered the most accurate method of assessment when compared with axial radiographs.7 The glenoid vault model as a measurement of glenoid bone loss has great promise in designing prosthetic replacements and bone graft techniques.8

Continue to: Modern methods for determining glenoid version...

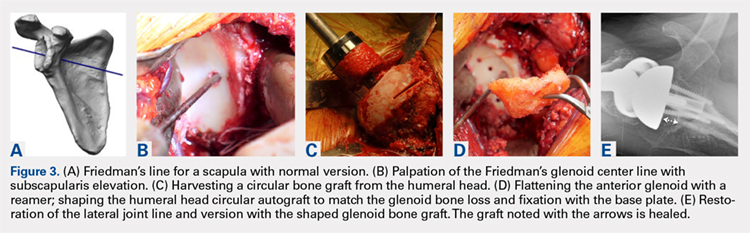

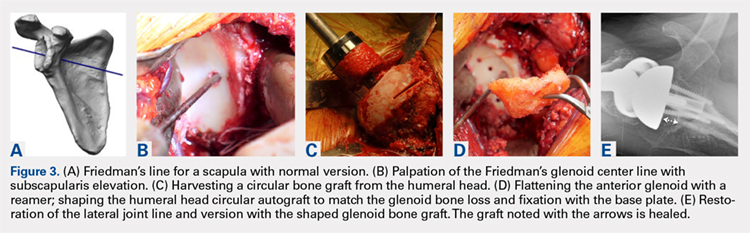

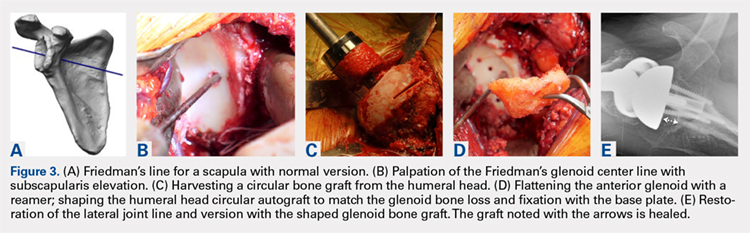

Modern methods for determining glenoid version, medialization, and eccentric bone wear include 3-D reconstruction and patient-specific instruments. For many years, version determination has been confirmed at surgery with subscapularis elevation, palpating the glenoid center point along Friedman’s line, and then inserting a Steinmann pin as a guide to restore version and the lateral joint line at the time of bone grafting. An example of this is demonstrated in Figures 3A-3E.9

All grafts are harvested with a hole saw from the humeral head. The inner diameter is 29 mm, the same as that of the base plate. Originally, the hole saw and mandrel were obtained from the hardware store, but Pascal Boileau upgraded the hole saw quality when he had industry develop a stainless-steel hole saw and published his results with the BIO-RSA (Wright Medical).10 In an unpublished study, Harmsen reviewed our 220 consecutive humeral head bone grafts for use of this technique with successful and reproducible results. In a separate evaluation, 29 shaped humeral head bone grafts for B2, B3, and C glenoid bone deficits showed 100% healing.11 This technique has good reproducibility when performed with an autogenous bone graft from a local donor source.

The more challenging cases involve glenoid bone loss from polyethylene osteolysis and, in some revision cases, concomitant sepsis.12 The humeral head is no longer available, and the distal clavicle or humeral metaphysis are often insufficient to restore the glenoid vault and joint line. Gunther and associates at the UC Berkeley biomaterials laboratory have made many contributions to our understanding of polyethylene wear and the factors leading to its loosening that result in massive glenoid bone loss.13

Antuna and colleagues14 classified these cases as having a central vault cavitary defect, or one combined with a peripheral glenoid wall bone loss of either the anterior or posterior glenoid. Newton and colleagues15 described the structural tricortical iliac crest bone graft as a 2-stage reconstruction. The second stage could be performed 4 to 6 months later after graft incorporation. With the excellent Association for Osteosynthesis (AO) type fixation using the base plate with compression and locking screws, it was reasonable to perform this in 1 stage, assuming that adequate fixation could be obtained with the iliac bone graft to the glenoid.16 This worked well with the cavitary glenoid defects and those in which either the anterior or posterior wall was absent.17-19

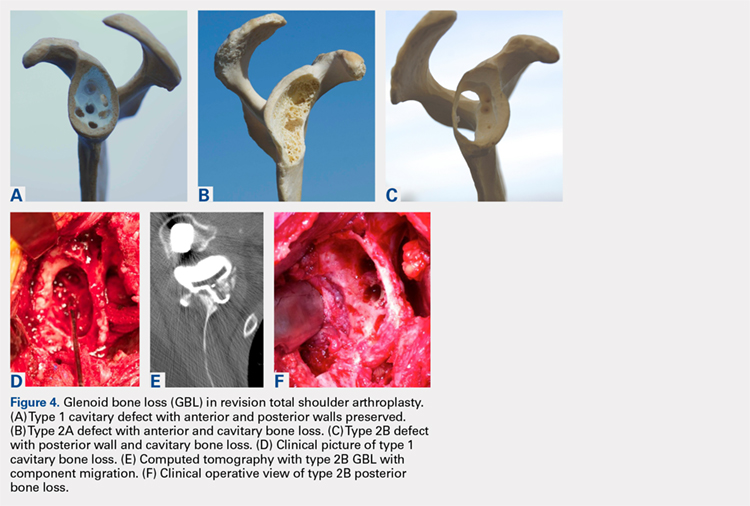

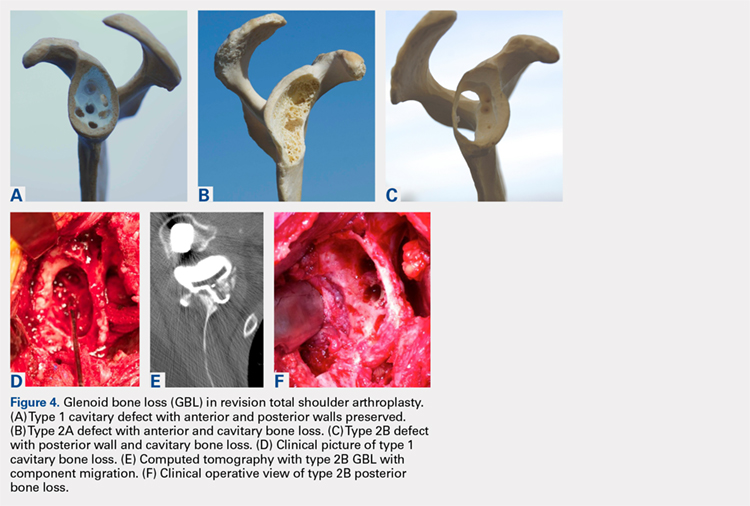

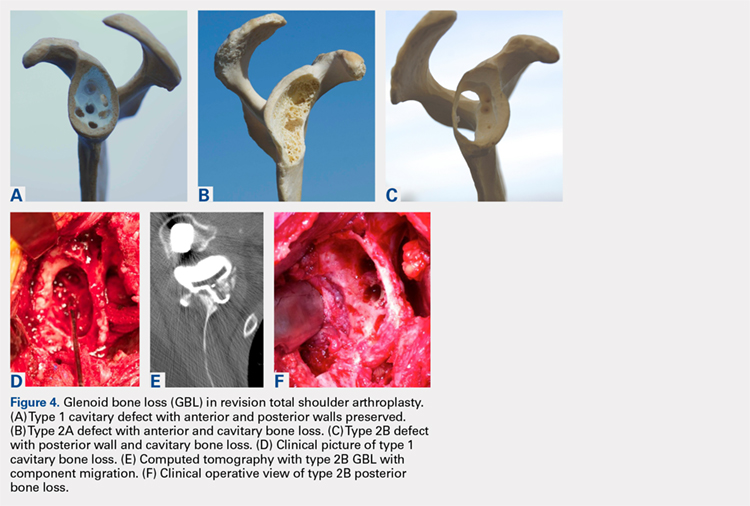

EXCEPTIONS TO THE 1-STAGE FIXATION TECHNIQUE

Fixation could still be obtained medially, but more severe cases were encountered with loss of both the anterior and posterior walls. In these more advanced cases, the vault was no longer present after removal of the polyethylene, cement, and rubbery osteolytic tissue that replaced the bone. To account for this, a simplified 3-stage classification was proposed.20 The cavitary vault defect is designated as type 1 bone loss. Type 2A includes the cavitary central defect plus loss of the anterior glenoid wall, and 2B is similar with loss of the posterior wall (Figures 4A-4F). Type 3 involves loss of the glenoid vault and both anterior and posterior walls with erosion down to the medial juncture of the base of the scapular spine, coracoid, and pillar of the scapula.

Continue to: The tricortical iliac crest bone graft...

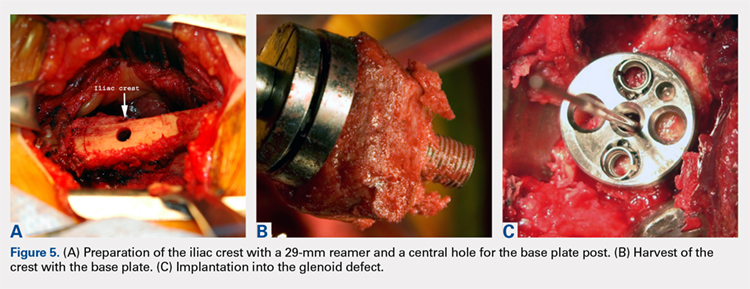

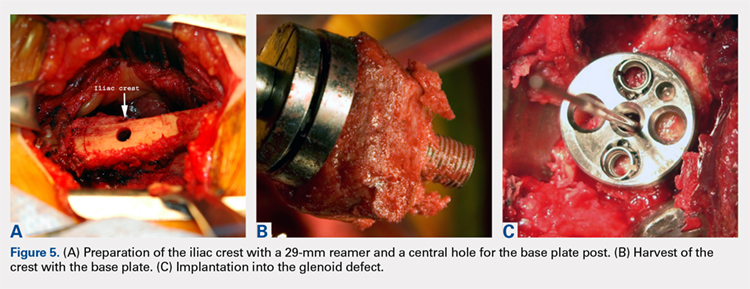

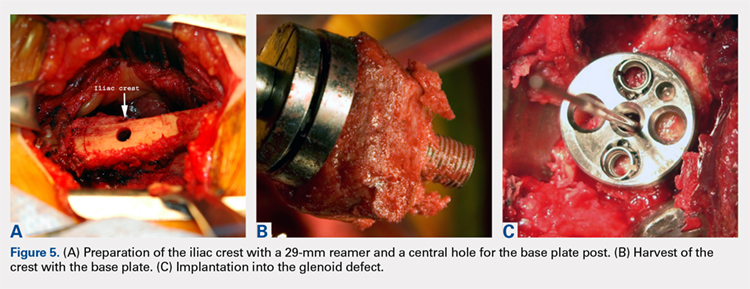

The tricortical iliac crest bone graft (TICBG) offered a structural graft that worked well for these cases of bone loss. When the graft is performed in 1 stage, the glenoid is exposed, and the defect measured after removing the osteolytic, polyethylene-laden tissue from the glenoid. The iliac graft is harvested and placed with the long post base plate engaging the native scapula medially (Figures 5A-5C).

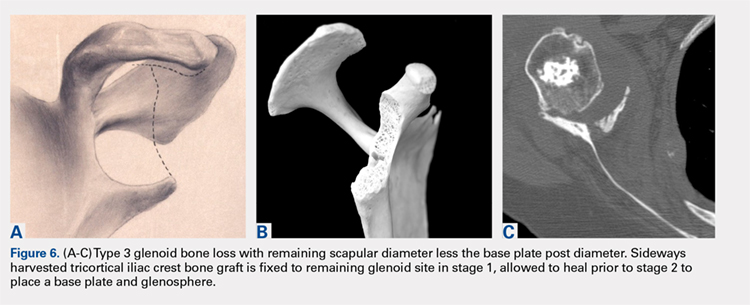

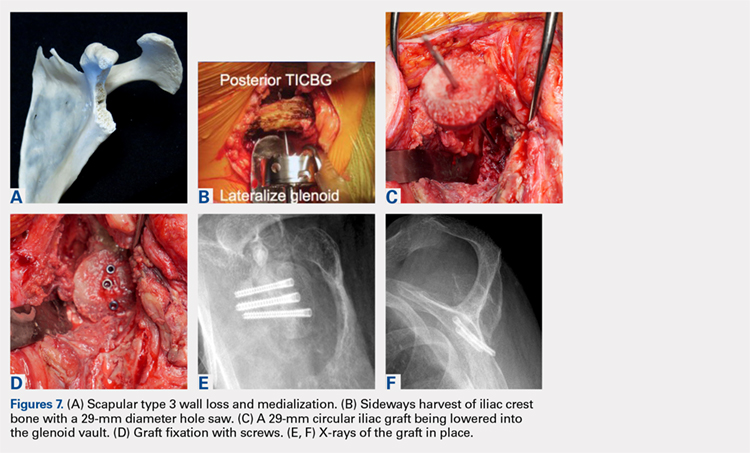

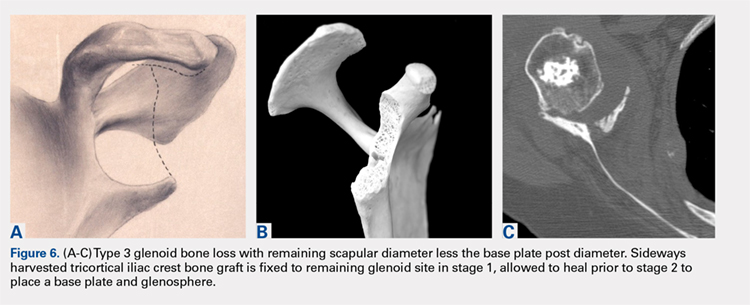

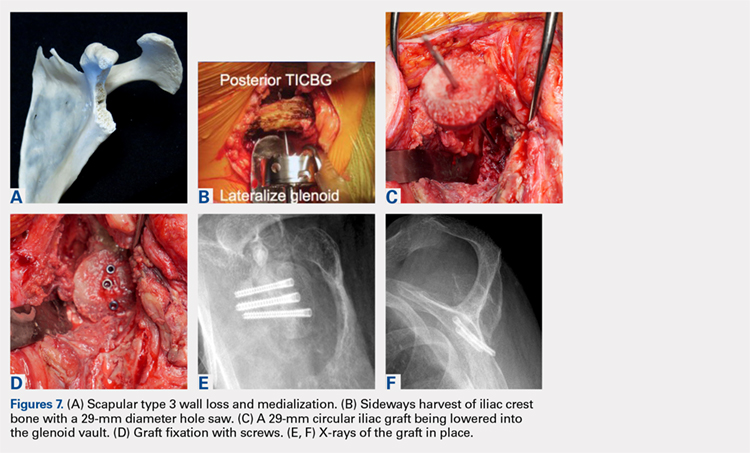

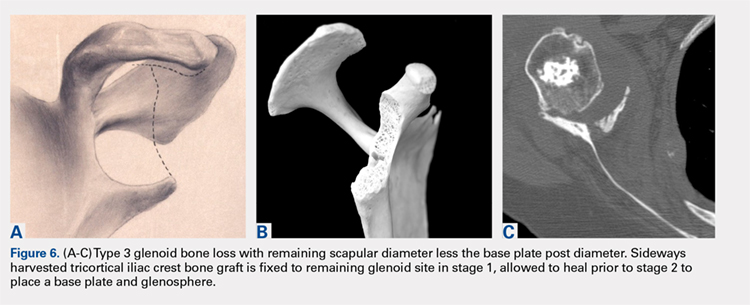

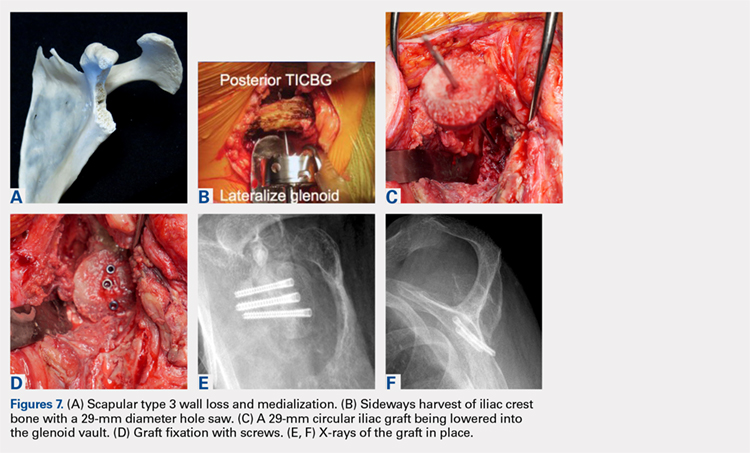

This technique worked well with the type 1 and 2 defects, but when attempted with the type 3 glenoid defect with global glenoid bone loss, adequate fixation for a single-stage reconstruction could not be predictably obtained with type 3 loss of the vault and both walls. In this situation, the base plate post is wider than the remaining medialized glenoid vault (Figures 6A-6C). The iliac crest provides better bone for this global loss when harvested sideways, fixed with screws, and after secure healing, the second-stage base plate is placed (Figures 7A-7F).

An alternative to the iliac crest as a bone graft donor site is the femoral neck allograft.21 It avoids the additional surgery and pain at the donor site, but healing is less assured. Scalise and Iannotti22 have had good clinical results but noted substantial graft resorption when revising a total shoulder to a humeral head arthroplasty. In a recent report by Ozgur and colleagues,23 64% of femoral neck allografts were still intact at 1-year follow-up. The technique involved harvesting the graft with a hole saw, shaping and affixing it to the deficient glenoid, and gaining central fixation with a threaded or solid post base plate and peripheral screws. Poor results were obtained with the use of the femoral shaft, as it is brittle. Angled peripheral screws caused the allograft shaft to fracture. Low-grade sepsis remained an unanswered problem in the patient group, which averaged 6 prior procedures, and often led to another revision. Less favorable results were found using the 1-piece threaded post base plate with grafts.24 It is assumed that the allograft has less healing potential, and micro motion plays a role when the long central screw has no on-growth healing potential in the native scapula. This graft choice is the author’s least favorite, but is available in desperate situations. Jones and colleagues25 report promising results with bulk allografts and autografts for large glenoid defects with good clinical results. The results in the graft cohort were inferior to those in a matched group not requiring grafts. Their complications were consistent with the revision setting for shoulders having multiple operations. It is well known that preoperative factors are strong predictors of postoperative outcomes.26

CONCLUSION

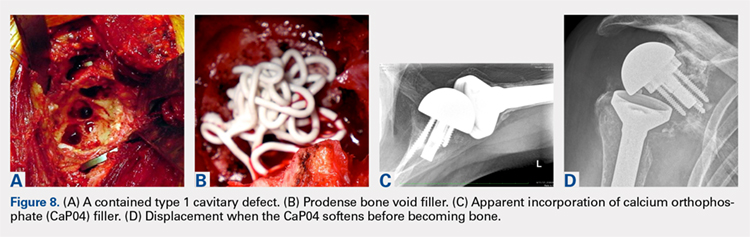

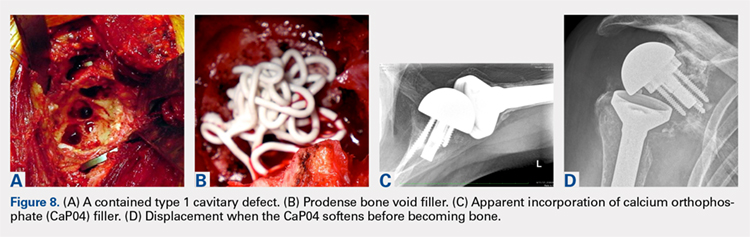

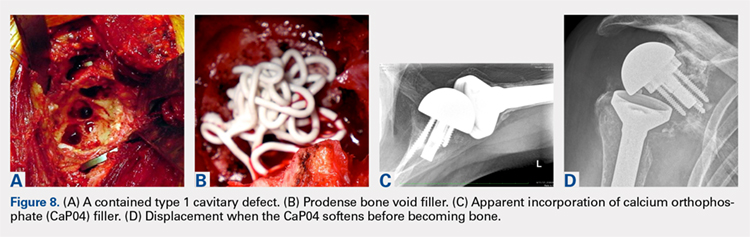

The author’s current technique is to use the native humeral head when available, or iliac crest for structural support to the base plate and glenosphere. Secure fixation to the native scapula is necessary if the operation is to be done in 1-stage. Incorporation with calcium orthophosphate bone substitution does not replace the need for structural support as shown in Figures 8A-8D.

For the type 2 vault and 1 wall glenoid bone loss defects, the TICBG is still the most useful option. For the type 3 global bone loss defects, a 2-stage approach is the safer option. Additional options that may replace some of these grafting techniques are the introduction of the metallic augmented ingrowth base plates to correct for superior, anterior, and posterior glenoid bone losses. The early unpublished experiences by Wright and colleagues are very promising. All of the above options should be available in the operating room for a busy arthroplasty surgeon.

1. Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobay Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:92-96.

2. Favard L, Alami G. The glenoid in the frontal plane: The Favard and Hamada radiographic classifications of cuff tear osteoarthritis. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:53-58.

3. Rouleau DM, Kidder JF, Pons-Villanueva J, Dynamidis S, Walch G. The glenoid in the horizontal plane: Walch classification revisited humeral subluxation and glenoid retroversion. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:45-51.

4. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphological study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

5. Iannotti JP, Ricchetti E. Walch classification: adding two new glenoid types. Orthopaedic Insights Cleveland Clinic. 2017:6-7.

6. Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, Walch G. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1297-1304.

7. Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: conventional radiographs verses computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):493-496.

8. Scalise JJ, Bryan J, Polster J, Brems JJ, Iannotti JP. Quantitative analysis of glenoid bone loss in osteoarthritis using three-dimensional compute tomography scans. [published online ahead of print January 22, 2008]. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):328-335.

9. Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(7):1032-1037.

10. Boileau P, Moineau G, Roussanne Y, O’Shea K. Bony increased-offset reverse shoulder arthroplasty: minimizing scapular impingement while maximizing glenoid fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2558-2567.

11. Harmsen S, Casagrande D, Norris T: “Shaped” humeral head autograft reverse shoulder arthroplasty: Treatment for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis with significant posterior glenoid bone loss (B2, B3, and C-type). Orthopade. 2017;46(12):1045-1054.

12. Norris TR, Phipatanakul WP. Treatment of glenoid loosening and bone loss due to osteolysis with glenoid bone grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(1):84-87.

13. Farzana F, Lee T, Malito L, et al. Analysis of severely fractured glenoid components: clinical consequences of biomechanics, design, and materials selection on implant performance. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(7):1041-1050.

14. Antuña SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

15. Newton L, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Edwards TB. Glenoid cortical cancellous bone grafting after glenoid component removal in the treatment of glenoid loosening. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):173-179.

16. Norris TR, Kelly JD, Humphrey CS. Management of glenoid bone defects in revision shoulder arthroplasty: a new application of the reverse total shoulder prosthesis. Techniques Shoulder Elbow Surgery. 2007;8(1):37-46.

17. Kelly JD II, Zhao JX, Hobgood ER, Norris TR. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty using the reverse prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1516-1525.

18. Norris TR. Reconstruction of glenoid bone loss in total shoulder arthroplasty. In: Boileau P, ed. Shoulder Concepts 2008-Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2008:397-404.

19. Humphrey CS, Kelly JD, Norris TR. Management of glenoid deficiency in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. In: Fealy S, Warren RF, Craig EV, Sperling JW, eds. Shoulder Arthroplasty. New York, NY: Thieme; 2006.

20. Norris TR, Abdus-Salaam S. Lessons learned from the Hylamer experience and technical salvage for glenoid reconstruction. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:265-278.

21. Bateman E, Donald SM. Reconstruction of massive uncontained glenoid defects using a combined autograft-allograft construct with reverse shoulder arthroplasty: preliminary results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):925-934.

22. Scalise JJ, Iannotti JP. Bone grafting severe glenoid defects in revision shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(1):139-145.

23. Ozgur S, Sadeghpour R, Norris TR. Revision shoulder arthroplasty with a reverse shoulder prosthesis. Use of structural allograft for glenoid bone loss. Orthopade. 2017;46(12):1055-1062.

24. Sadeghpour R, Ozgur S, Norris TR. Threaded post baseplate failures in RSA. In: Hardy PH, Valenti PH, Scheibel M, eds. Shoulder Arthroplasty, Current Concepts. Paris International Shoulder Course 2017. 2017:148-157.

25. Jones RB, Wright TW, Zuckerman JD. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with structural bone grafting of large glenoid defects. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(9):1425-1432.

26. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85(2):251-258.

ABSTRACT

The reverse shoulder arthroplasty facilitates surgical treatment of primary and revision shoulder with rotator cuff and bone deficiencies. Wear pattern classifications and a logical treatment approach for glenoid bone loss enable the surgeon to address a difficult series of problems in the reconstructions where the glenoid might not otherwise be able to support the implants. Bone grafting using the native humeral head in primary cases, and in revision cases, iliac crest are the most reliable sources for structural grafts for the worn or deficient glenoid vault.

Continue to: The reverse shoulder arthroplasty...

The reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) technique was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and introduced to the US market in 2004. It has been a successful addition to the treatment of shoulder pathologies with bone and rotator cuff loss. Its indications have expanded from treatment of very elderly patients with rotator cuff deficiencies to now include younger patients with humeral and glenoid bone loss, arthritis, soft-tissue losses, fractures, instability, and revision arthroplasty. Many of these conditions, when not adequately addressed with anatomic arthroplasty, now have viable treatment options for newer complex and successful reconstructions.

Glenoid bone deficiencies offer unique challenges for successful arthroplasty management. Basing treatment on bone loss classifications permits meaningful evaluation of these surgical options and whether they might be carried out in 1- or 2-stage reconstructions. An underlying premise is that restoration of the glenoid joint line and version assist in final stability, power, and functional results. For this purpose, bone graft options, or augmented implants are beneficial. This review covers the bone grafting options for autografts and allografts for deficient glenoids in reverse shoulder arthroplasty reconstructions.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

For patients without prior arthroplasty, the humeral head is available for bone grafting the glenoid bone deficits. Favard and Hamada have described vertical glenoid classifications for uneven glenoid bone loss applicable to cuff tear arthropathy and inflammatory arthritis patients.1,2 The more severe E3 superior and medial bone loss is ideally addressed with the humeral head. An early example in 2004 confirmed that this was a good indication for glenoid bone grafting and using the reverse shoulder in these advanced cases (Figures 1A-1E).

In this case, it was noted that with bone grafts the base plate post did not engage the native scapula glenoid vault. Given that the on-growth central post was the strongest part of the fixation, it was fortunate that this healed. The need for a longer post with bone grafts was recognized. Laurent Comtat with the Wright Medical company accommodated the author’s request to develop the first 25- and 30-mm-long posts to allow better fixation and on-growth potential when used with bone grafts.

Gilles Walch’s classification addresses arthritic central and horizontal bone loss.3,4 Considerations relevant in RSA include the severe A2 central bone loss found in inflammatory arthritis and the B2, B3, and C patterns with posterior bone loss seen in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and congenital dysplasia5,6 as seen in Figures 2A, 2B. The 3-dimensional (3-D) computed tomography (CT) scan is considered the most accurate method of assessment when compared with axial radiographs.7 The glenoid vault model as a measurement of glenoid bone loss has great promise in designing prosthetic replacements and bone graft techniques.8

Continue to: Modern methods for determining glenoid version...

Modern methods for determining glenoid version, medialization, and eccentric bone wear include 3-D reconstruction and patient-specific instruments. For many years, version determination has been confirmed at surgery with subscapularis elevation, palpating the glenoid center point along Friedman’s line, and then inserting a Steinmann pin as a guide to restore version and the lateral joint line at the time of bone grafting. An example of this is demonstrated in Figures 3A-3E.9

All grafts are harvested with a hole saw from the humeral head. The inner diameter is 29 mm, the same as that of the base plate. Originally, the hole saw and mandrel were obtained from the hardware store, but Pascal Boileau upgraded the hole saw quality when he had industry develop a stainless-steel hole saw and published his results with the BIO-RSA (Wright Medical).10 In an unpublished study, Harmsen reviewed our 220 consecutive humeral head bone grafts for use of this technique with successful and reproducible results. In a separate evaluation, 29 shaped humeral head bone grafts for B2, B3, and C glenoid bone deficits showed 100% healing.11 This technique has good reproducibility when performed with an autogenous bone graft from a local donor source.

The more challenging cases involve glenoid bone loss from polyethylene osteolysis and, in some revision cases, concomitant sepsis.12 The humeral head is no longer available, and the distal clavicle or humeral metaphysis are often insufficient to restore the glenoid vault and joint line. Gunther and associates at the UC Berkeley biomaterials laboratory have made many contributions to our understanding of polyethylene wear and the factors leading to its loosening that result in massive glenoid bone loss.13

Antuna and colleagues14 classified these cases as having a central vault cavitary defect, or one combined with a peripheral glenoid wall bone loss of either the anterior or posterior glenoid. Newton and colleagues15 described the structural tricortical iliac crest bone graft as a 2-stage reconstruction. The second stage could be performed 4 to 6 months later after graft incorporation. With the excellent Association for Osteosynthesis (AO) type fixation using the base plate with compression and locking screws, it was reasonable to perform this in 1 stage, assuming that adequate fixation could be obtained with the iliac bone graft to the glenoid.16 This worked well with the cavitary glenoid defects and those in which either the anterior or posterior wall was absent.17-19

EXCEPTIONS TO THE 1-STAGE FIXATION TECHNIQUE

Fixation could still be obtained medially, but more severe cases were encountered with loss of both the anterior and posterior walls. In these more advanced cases, the vault was no longer present after removal of the polyethylene, cement, and rubbery osteolytic tissue that replaced the bone. To account for this, a simplified 3-stage classification was proposed.20 The cavitary vault defect is designated as type 1 bone loss. Type 2A includes the cavitary central defect plus loss of the anterior glenoid wall, and 2B is similar with loss of the posterior wall (Figures 4A-4F). Type 3 involves loss of the glenoid vault and both anterior and posterior walls with erosion down to the medial juncture of the base of the scapular spine, coracoid, and pillar of the scapula.

Continue to: The tricortical iliac crest bone graft...

The tricortical iliac crest bone graft (TICBG) offered a structural graft that worked well for these cases of bone loss. When the graft is performed in 1 stage, the glenoid is exposed, and the defect measured after removing the osteolytic, polyethylene-laden tissue from the glenoid. The iliac graft is harvested and placed with the long post base plate engaging the native scapula medially (Figures 5A-5C).

This technique worked well with the type 1 and 2 defects, but when attempted with the type 3 glenoid defect with global glenoid bone loss, adequate fixation for a single-stage reconstruction could not be predictably obtained with type 3 loss of the vault and both walls. In this situation, the base plate post is wider than the remaining medialized glenoid vault (Figures 6A-6C). The iliac crest provides better bone for this global loss when harvested sideways, fixed with screws, and after secure healing, the second-stage base plate is placed (Figures 7A-7F).

An alternative to the iliac crest as a bone graft donor site is the femoral neck allograft.21 It avoids the additional surgery and pain at the donor site, but healing is less assured. Scalise and Iannotti22 have had good clinical results but noted substantial graft resorption when revising a total shoulder to a humeral head arthroplasty. In a recent report by Ozgur and colleagues,23 64% of femoral neck allografts were still intact at 1-year follow-up. The technique involved harvesting the graft with a hole saw, shaping and affixing it to the deficient glenoid, and gaining central fixation with a threaded or solid post base plate and peripheral screws. Poor results were obtained with the use of the femoral shaft, as it is brittle. Angled peripheral screws caused the allograft shaft to fracture. Low-grade sepsis remained an unanswered problem in the patient group, which averaged 6 prior procedures, and often led to another revision. Less favorable results were found using the 1-piece threaded post base plate with grafts.24 It is assumed that the allograft has less healing potential, and micro motion plays a role when the long central screw has no on-growth healing potential in the native scapula. This graft choice is the author’s least favorite, but is available in desperate situations. Jones and colleagues25 report promising results with bulk allografts and autografts for large glenoid defects with good clinical results. The results in the graft cohort were inferior to those in a matched group not requiring grafts. Their complications were consistent with the revision setting for shoulders having multiple operations. It is well known that preoperative factors are strong predictors of postoperative outcomes.26

CONCLUSION

The author’s current technique is to use the native humeral head when available, or iliac crest for structural support to the base plate and glenosphere. Secure fixation to the native scapula is necessary if the operation is to be done in 1-stage. Incorporation with calcium orthophosphate bone substitution does not replace the need for structural support as shown in Figures 8A-8D.

For the type 2 vault and 1 wall glenoid bone loss defects, the TICBG is still the most useful option. For the type 3 global bone loss defects, a 2-stage approach is the safer option. Additional options that may replace some of these grafting techniques are the introduction of the metallic augmented ingrowth base plates to correct for superior, anterior, and posterior glenoid bone losses. The early unpublished experiences by Wright and colleagues are very promising. All of the above options should be available in the operating room for a busy arthroplasty surgeon.

ABSTRACT

The reverse shoulder arthroplasty facilitates surgical treatment of primary and revision shoulder with rotator cuff and bone deficiencies. Wear pattern classifications and a logical treatment approach for glenoid bone loss enable the surgeon to address a difficult series of problems in the reconstructions where the glenoid might not otherwise be able to support the implants. Bone grafting using the native humeral head in primary cases, and in revision cases, iliac crest are the most reliable sources for structural grafts for the worn or deficient glenoid vault.

Continue to: The reverse shoulder arthroplasty...

The reverse shoulder arthroplasty (RSA) technique was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration and introduced to the US market in 2004. It has been a successful addition to the treatment of shoulder pathologies with bone and rotator cuff loss. Its indications have expanded from treatment of very elderly patients with rotator cuff deficiencies to now include younger patients with humeral and glenoid bone loss, arthritis, soft-tissue losses, fractures, instability, and revision arthroplasty. Many of these conditions, when not adequately addressed with anatomic arthroplasty, now have viable treatment options for newer complex and successful reconstructions.

Glenoid bone deficiencies offer unique challenges for successful arthroplasty management. Basing treatment on bone loss classifications permits meaningful evaluation of these surgical options and whether they might be carried out in 1- or 2-stage reconstructions. An underlying premise is that restoration of the glenoid joint line and version assist in final stability, power, and functional results. For this purpose, bone graft options, or augmented implants are beneficial. This review covers the bone grafting options for autografts and allografts for deficient glenoids in reverse shoulder arthroplasty reconstructions.

OPERATIVE TECHNIQUES

For patients without prior arthroplasty, the humeral head is available for bone grafting the glenoid bone deficits. Favard and Hamada have described vertical glenoid classifications for uneven glenoid bone loss applicable to cuff tear arthropathy and inflammatory arthritis patients.1,2 The more severe E3 superior and medial bone loss is ideally addressed with the humeral head. An early example in 2004 confirmed that this was a good indication for glenoid bone grafting and using the reverse shoulder in these advanced cases (Figures 1A-1E).

In this case, it was noted that with bone grafts the base plate post did not engage the native scapula glenoid vault. Given that the on-growth central post was the strongest part of the fixation, it was fortunate that this healed. The need for a longer post with bone grafts was recognized. Laurent Comtat with the Wright Medical company accommodated the author’s request to develop the first 25- and 30-mm-long posts to allow better fixation and on-growth potential when used with bone grafts.

Gilles Walch’s classification addresses arthritic central and horizontal bone loss.3,4 Considerations relevant in RSA include the severe A2 central bone loss found in inflammatory arthritis and the B2, B3, and C patterns with posterior bone loss seen in osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and congenital dysplasia5,6 as seen in Figures 2A, 2B. The 3-dimensional (3-D) computed tomography (CT) scan is considered the most accurate method of assessment when compared with axial radiographs.7 The glenoid vault model as a measurement of glenoid bone loss has great promise in designing prosthetic replacements and bone graft techniques.8

Continue to: Modern methods for determining glenoid version...

Modern methods for determining glenoid version, medialization, and eccentric bone wear include 3-D reconstruction and patient-specific instruments. For many years, version determination has been confirmed at surgery with subscapularis elevation, palpating the glenoid center point along Friedman’s line, and then inserting a Steinmann pin as a guide to restore version and the lateral joint line at the time of bone grafting. An example of this is demonstrated in Figures 3A-3E.9

All grafts are harvested with a hole saw from the humeral head. The inner diameter is 29 mm, the same as that of the base plate. Originally, the hole saw and mandrel were obtained from the hardware store, but Pascal Boileau upgraded the hole saw quality when he had industry develop a stainless-steel hole saw and published his results with the BIO-RSA (Wright Medical).10 In an unpublished study, Harmsen reviewed our 220 consecutive humeral head bone grafts for use of this technique with successful and reproducible results. In a separate evaluation, 29 shaped humeral head bone grafts for B2, B3, and C glenoid bone deficits showed 100% healing.11 This technique has good reproducibility when performed with an autogenous bone graft from a local donor source.

The more challenging cases involve glenoid bone loss from polyethylene osteolysis and, in some revision cases, concomitant sepsis.12 The humeral head is no longer available, and the distal clavicle or humeral metaphysis are often insufficient to restore the glenoid vault and joint line. Gunther and associates at the UC Berkeley biomaterials laboratory have made many contributions to our understanding of polyethylene wear and the factors leading to its loosening that result in massive glenoid bone loss.13

Antuna and colleagues14 classified these cases as having a central vault cavitary defect, or one combined with a peripheral glenoid wall bone loss of either the anterior or posterior glenoid. Newton and colleagues15 described the structural tricortical iliac crest bone graft as a 2-stage reconstruction. The second stage could be performed 4 to 6 months later after graft incorporation. With the excellent Association for Osteosynthesis (AO) type fixation using the base plate with compression and locking screws, it was reasonable to perform this in 1 stage, assuming that adequate fixation could be obtained with the iliac bone graft to the glenoid.16 This worked well with the cavitary glenoid defects and those in which either the anterior or posterior wall was absent.17-19

EXCEPTIONS TO THE 1-STAGE FIXATION TECHNIQUE

Fixation could still be obtained medially, but more severe cases were encountered with loss of both the anterior and posterior walls. In these more advanced cases, the vault was no longer present after removal of the polyethylene, cement, and rubbery osteolytic tissue that replaced the bone. To account for this, a simplified 3-stage classification was proposed.20 The cavitary vault defect is designated as type 1 bone loss. Type 2A includes the cavitary central defect plus loss of the anterior glenoid wall, and 2B is similar with loss of the posterior wall (Figures 4A-4F). Type 3 involves loss of the glenoid vault and both anterior and posterior walls with erosion down to the medial juncture of the base of the scapular spine, coracoid, and pillar of the scapula.

Continue to: The tricortical iliac crest bone graft...

The tricortical iliac crest bone graft (TICBG) offered a structural graft that worked well for these cases of bone loss. When the graft is performed in 1 stage, the glenoid is exposed, and the defect measured after removing the osteolytic, polyethylene-laden tissue from the glenoid. The iliac graft is harvested and placed with the long post base plate engaging the native scapula medially (Figures 5A-5C).

This technique worked well with the type 1 and 2 defects, but when attempted with the type 3 glenoid defect with global glenoid bone loss, adequate fixation for a single-stage reconstruction could not be predictably obtained with type 3 loss of the vault and both walls. In this situation, the base plate post is wider than the remaining medialized glenoid vault (Figures 6A-6C). The iliac crest provides better bone for this global loss when harvested sideways, fixed with screws, and after secure healing, the second-stage base plate is placed (Figures 7A-7F).

An alternative to the iliac crest as a bone graft donor site is the femoral neck allograft.21 It avoids the additional surgery and pain at the donor site, but healing is less assured. Scalise and Iannotti22 have had good clinical results but noted substantial graft resorption when revising a total shoulder to a humeral head arthroplasty. In a recent report by Ozgur and colleagues,23 64% of femoral neck allografts were still intact at 1-year follow-up. The technique involved harvesting the graft with a hole saw, shaping and affixing it to the deficient glenoid, and gaining central fixation with a threaded or solid post base plate and peripheral screws. Poor results were obtained with the use of the femoral shaft, as it is brittle. Angled peripheral screws caused the allograft shaft to fracture. Low-grade sepsis remained an unanswered problem in the patient group, which averaged 6 prior procedures, and often led to another revision. Less favorable results were found using the 1-piece threaded post base plate with grafts.24 It is assumed that the allograft has less healing potential, and micro motion plays a role when the long central screw has no on-growth healing potential in the native scapula. This graft choice is the author’s least favorite, but is available in desperate situations. Jones and colleagues25 report promising results with bulk allografts and autografts for large glenoid defects with good clinical results. The results in the graft cohort were inferior to those in a matched group not requiring grafts. Their complications were consistent with the revision setting for shoulders having multiple operations. It is well known that preoperative factors are strong predictors of postoperative outcomes.26

CONCLUSION

The author’s current technique is to use the native humeral head when available, or iliac crest for structural support to the base plate and glenosphere. Secure fixation to the native scapula is necessary if the operation is to be done in 1-stage. Incorporation with calcium orthophosphate bone substitution does not replace the need for structural support as shown in Figures 8A-8D.

For the type 2 vault and 1 wall glenoid bone loss defects, the TICBG is still the most useful option. For the type 3 global bone loss defects, a 2-stage approach is the safer option. Additional options that may replace some of these grafting techniques are the introduction of the metallic augmented ingrowth base plates to correct for superior, anterior, and posterior glenoid bone losses. The early unpublished experiences by Wright and colleagues are very promising. All of the above options should be available in the operating room for a busy arthroplasty surgeon.

1. Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobay Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:92-96.

2. Favard L, Alami G. The glenoid in the frontal plane: The Favard and Hamada radiographic classifications of cuff tear osteoarthritis. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:53-58.

3. Rouleau DM, Kidder JF, Pons-Villanueva J, Dynamidis S, Walch G. The glenoid in the horizontal plane: Walch classification revisited humeral subluxation and glenoid retroversion. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:45-51.

4. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphological study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

5. Iannotti JP, Ricchetti E. Walch classification: adding two new glenoid types. Orthopaedic Insights Cleveland Clinic. 2017:6-7.

6. Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, Walch G. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1297-1304.

7. Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: conventional radiographs verses computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):493-496.

8. Scalise JJ, Bryan J, Polster J, Brems JJ, Iannotti JP. Quantitative analysis of glenoid bone loss in osteoarthritis using three-dimensional compute tomography scans. [published online ahead of print January 22, 2008]. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):328-335.

9. Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(7):1032-1037.

10. Boileau P, Moineau G, Roussanne Y, O’Shea K. Bony increased-offset reverse shoulder arthroplasty: minimizing scapular impingement while maximizing glenoid fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2558-2567.

11. Harmsen S, Casagrande D, Norris T: “Shaped” humeral head autograft reverse shoulder arthroplasty: Treatment for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis with significant posterior glenoid bone loss (B2, B3, and C-type). Orthopade. 2017;46(12):1045-1054.

12. Norris TR, Phipatanakul WP. Treatment of glenoid loosening and bone loss due to osteolysis with glenoid bone grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(1):84-87.

13. Farzana F, Lee T, Malito L, et al. Analysis of severely fractured glenoid components: clinical consequences of biomechanics, design, and materials selection on implant performance. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(7):1041-1050.

14. Antuña SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

15. Newton L, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Edwards TB. Glenoid cortical cancellous bone grafting after glenoid component removal in the treatment of glenoid loosening. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):173-179.

16. Norris TR, Kelly JD, Humphrey CS. Management of glenoid bone defects in revision shoulder arthroplasty: a new application of the reverse total shoulder prosthesis. Techniques Shoulder Elbow Surgery. 2007;8(1):37-46.

17. Kelly JD II, Zhao JX, Hobgood ER, Norris TR. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty using the reverse prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1516-1525.

18. Norris TR. Reconstruction of glenoid bone loss in total shoulder arthroplasty. In: Boileau P, ed. Shoulder Concepts 2008-Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2008:397-404.

19. Humphrey CS, Kelly JD, Norris TR. Management of glenoid deficiency in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. In: Fealy S, Warren RF, Craig EV, Sperling JW, eds. Shoulder Arthroplasty. New York, NY: Thieme; 2006.

20. Norris TR, Abdus-Salaam S. Lessons learned from the Hylamer experience and technical salvage for glenoid reconstruction. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:265-278.

21. Bateman E, Donald SM. Reconstruction of massive uncontained glenoid defects using a combined autograft-allograft construct with reverse shoulder arthroplasty: preliminary results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):925-934.

22. Scalise JJ, Iannotti JP. Bone grafting severe glenoid defects in revision shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(1):139-145.

23. Ozgur S, Sadeghpour R, Norris TR. Revision shoulder arthroplasty with a reverse shoulder prosthesis. Use of structural allograft for glenoid bone loss. Orthopade. 2017;46(12):1055-1062.

24. Sadeghpour R, Ozgur S, Norris TR. Threaded post baseplate failures in RSA. In: Hardy PH, Valenti PH, Scheibel M, eds. Shoulder Arthroplasty, Current Concepts. Paris International Shoulder Course 2017. 2017:148-157.

25. Jones RB, Wright TW, Zuckerman JD. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with structural bone grafting of large glenoid defects. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(9):1425-1432.

26. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85(2):251-258.

1. Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobay Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;254:92-96.

2. Favard L, Alami G. The glenoid in the frontal plane: The Favard and Hamada radiographic classifications of cuff tear osteoarthritis. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:53-58.

3. Rouleau DM, Kidder JF, Pons-Villanueva J, Dynamidis S, Walch G. The glenoid in the horizontal plane: Walch classification revisited humeral subluxation and glenoid retroversion. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:45-51.

4. Walch G, Badet R, Boulahia A, Khoury A. Morphological study of the glenoid in primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Arthroplasty. 1999;14(6):756-760.

5. Iannotti JP, Ricchetti E. Walch classification: adding two new glenoid types. Orthopaedic Insights Cleveland Clinic. 2017:6-7.

6. Mizuno N, Denard PJ, Raiss P, Walch G. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis with a biconcave glenoid. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(14):1297-1304.

7. Nyffeler RW, Jost B, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Measurement of glenoid version: conventional radiographs verses computed tomography scans. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12(5):493-496.

8. Scalise JJ, Bryan J, Polster J, Brems JJ, Iannotti JP. Quantitative analysis of glenoid bone loss in osteoarthritis using three-dimensional compute tomography scans. [published online ahead of print January 22, 2008]. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(2):328-335.

9. Friedman RJ, Hawthorne KB, Genez BM. The use of computerized tomography in the measurement of glenoid version. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74(7):1032-1037.

10. Boileau P, Moineau G, Roussanne Y, O’Shea K. Bony increased-offset reverse shoulder arthroplasty: minimizing scapular impingement while maximizing glenoid fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469(9):2558-2567.

11. Harmsen S, Casagrande D, Norris T: “Shaped” humeral head autograft reverse shoulder arthroplasty: Treatment for primary glenohumeral osteoarthritis with significant posterior glenoid bone loss (B2, B3, and C-type). Orthopade. 2017;46(12):1045-1054.

12. Norris TR, Phipatanakul WP. Treatment of glenoid loosening and bone loss due to osteolysis with glenoid bone grafting. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(1):84-87.

13. Farzana F, Lee T, Malito L, et al. Analysis of severely fractured glenoid components: clinical consequences of biomechanics, design, and materials selection on implant performance. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(7):1041-1050.

14. Antuña SA, Sperling JW, Cofield RH, Rowland CM. Glenoid revision surgery after total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(3):217-224.

15. Newton L, Walch G, Nove-Josserand L, Edwards TB. Glenoid cortical cancellous bone grafting after glenoid component removal in the treatment of glenoid loosening. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(2):173-179.

16. Norris TR, Kelly JD, Humphrey CS. Management of glenoid bone defects in revision shoulder arthroplasty: a new application of the reverse total shoulder prosthesis. Techniques Shoulder Elbow Surgery. 2007;8(1):37-46.

17. Kelly JD II, Zhao JX, Hobgood ER, Norris TR. Clinical results of revision shoulder arthroplasty using the reverse prosthesis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1516-1525.

18. Norris TR. Reconstruction of glenoid bone loss in total shoulder arthroplasty. In: Boileau P, ed. Shoulder Concepts 2008-Arthroscopy and Arthroplasty. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2008:397-404.

19. Humphrey CS, Kelly JD, Norris TR. Management of glenoid deficiency in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. In: Fealy S, Warren RF, Craig EV, Sperling JW, eds. Shoulder Arthroplasty. New York, NY: Thieme; 2006.

20. Norris TR, Abdus-Salaam S. Lessons learned from the Hylamer experience and technical salvage for glenoid reconstruction. In: Walch G, Boileau P, Favard ML, Lévigne C, Sirveaux F, eds. Shoulder Concepts 2010: The Glenoid. Paris, France: Sauramps Medical; 2010:265-278.

21. Bateman E, Donald SM. Reconstruction of massive uncontained glenoid defects using a combined autograft-allograft construct with reverse shoulder arthroplasty: preliminary results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(7):925-934.

22. Scalise JJ, Iannotti JP. Bone grafting severe glenoid defects in revision shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop. 2008;466(1):139-145.

23. Ozgur S, Sadeghpour R, Norris TR. Revision shoulder arthroplasty with a reverse shoulder prosthesis. Use of structural allograft for glenoid bone loss. Orthopade. 2017;46(12):1055-1062.

24. Sadeghpour R, Ozgur S, Norris TR. Threaded post baseplate failures in RSA. In: Hardy PH, Valenti PH, Scheibel M, eds. Shoulder Arthroplasty, Current Concepts. Paris International Shoulder Course 2017. 2017:148-157.

25. Jones RB, Wright TW, Zuckerman JD. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with structural bone grafting of large glenoid defects. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(9):1425-1432.

26. Iannotti JP, Norris TR. Influence of preoperative factors on outcome of shoulder arthroplasty for glenohumeral osteoarthritis. J Bone Joint Surg. 2003;85(2):251-258.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- Glenoid deficiencies that occur from dysplasia, arthritis, or polyethylene osteolysis may be successfully addressed with bone grafting techniques and reverse shoulder arthroplasty.

- The intact humeral head in a primary case is ideal graft to be shaped to fit the glenoid deficits.

- The reverse shoulder with a long post base plate that is fixed securely to the native scapula is the author’s preferred technique.

- As the native humeral head is not available in revision cases, the tricortical iliac crest bone graft may be fixed as a structural graft in 1-stage.

- When the scapular walls are deficient and medial fixation is not secure, 2 stages 4 months to 6 months apart will be necessary before loading the construct.

Takotsubo cardiomyopathy incidence, mortality on the rise

WASHINGTON – Hospitalizations for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), a condition that primarily affects postmenopausal women, have been rising steadily, along with rates of in-hospital mortality due to this condition, according to a study conducted with outcomes from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database.

The study was presented at CRT 2018, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

Importantly, a multivariate analysis of predictors of in-hospital mortality based on this database revealed that there were “several potentially reversible causes,” reported Konstantinos V. Voudris, MD, PhD, who is completing a residency in internal medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

TCM, which is characterized by left ventricular apical akinesis and chest pain that mimics the features of acute coronary syndromes (ACS), was first described in 1990 in Japan. The first U.S. case was reported in 1998, but the condition is now well recognized and an ICD code was created for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in 2007.

There were 72,559 TCM admissions during the study period. When stratified by year, the annual rate of TCM cases rose significantly, from 11.1 to 43.8 per 100,000 hospitalizations from 2007 to 2013.

Although overall in-hospital mortality was 2.5%, it climbed from 1.4% in 2007 to 3.2% in 2013. When compared to patients who did not die during hospitalizations, those who did die were on average older (69.9 vs. 66.4 years; P less than .0001) and had more comorbidities. When a multivariate adjustment was made for baseline clinical risk, the presence of acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), pulmonary hypertension, and arrhythmias remained significant predictors of mortality in patients with TCM.

“We found a number of modifiable and nonmodifiable factors that are associated with a significantly increased mortality, and we think clinicians should be aware of these factors when managing this condition,” Dr. Voudris reported.

Of these risk factors, AKI was associated with the greatest increased odds ratio (OR) with a more than fourfold increased risk of death (OR, 4.18; P less than .001). The presence of PAD (OR, 1.87; P less than .0001) and arrhythmia (OR, 1.88; P less than .0001) almost doubled the risk of in-hospital mortality.

Although females represented 89% of the TCM cases collected during the study period, males with comorbid diseases were at particularly high risk of death, an observation that is consistent with previous reports, according to Dr. Voudris. Relative to women, men were more likely to present with unstable hemodynamics and to develop cardiogenic shock.

Although Dr. Voudris acknowledged that the rising number of hospitalizations for TCM is likely due largely to increasing recognition of this condition, he suggested that there may be other contributing factors to the growing incidence, such as the aging of the U.S. population. He noted that the rise in cases persisted throughout the study period when awareness of TCM might be expected to have improved.

“This is still an uncommon disease, but it is important to recognize,” agreed Sachin Kumar, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Moderator of the session in which these data were presented, Dr. Kumar indicated that it is important to increase awareness of the condition to accelerate the time to diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Voudris reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Voudris, KV. CRT 2018.

WASHINGTON – Hospitalizations for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), a condition that primarily affects postmenopausal women, have been rising steadily, along with rates of in-hospital mortality due to this condition, according to a study conducted with outcomes from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database.

The study was presented at CRT 2018, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

Importantly, a multivariate analysis of predictors of in-hospital mortality based on this database revealed that there were “several potentially reversible causes,” reported Konstantinos V. Voudris, MD, PhD, who is completing a residency in internal medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

TCM, which is characterized by left ventricular apical akinesis and chest pain that mimics the features of acute coronary syndromes (ACS), was first described in 1990 in Japan. The first U.S. case was reported in 1998, but the condition is now well recognized and an ICD code was created for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in 2007.

There were 72,559 TCM admissions during the study period. When stratified by year, the annual rate of TCM cases rose significantly, from 11.1 to 43.8 per 100,000 hospitalizations from 2007 to 2013.

Although overall in-hospital mortality was 2.5%, it climbed from 1.4% in 2007 to 3.2% in 2013. When compared to patients who did not die during hospitalizations, those who did die were on average older (69.9 vs. 66.4 years; P less than .0001) and had more comorbidities. When a multivariate adjustment was made for baseline clinical risk, the presence of acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), pulmonary hypertension, and arrhythmias remained significant predictors of mortality in patients with TCM.

“We found a number of modifiable and nonmodifiable factors that are associated with a significantly increased mortality, and we think clinicians should be aware of these factors when managing this condition,” Dr. Voudris reported.

Of these risk factors, AKI was associated with the greatest increased odds ratio (OR) with a more than fourfold increased risk of death (OR, 4.18; P less than .001). The presence of PAD (OR, 1.87; P less than .0001) and arrhythmia (OR, 1.88; P less than .0001) almost doubled the risk of in-hospital mortality.

Although females represented 89% of the TCM cases collected during the study period, males with comorbid diseases were at particularly high risk of death, an observation that is consistent with previous reports, according to Dr. Voudris. Relative to women, men were more likely to present with unstable hemodynamics and to develop cardiogenic shock.

Although Dr. Voudris acknowledged that the rising number of hospitalizations for TCM is likely due largely to increasing recognition of this condition, he suggested that there may be other contributing factors to the growing incidence, such as the aging of the U.S. population. He noted that the rise in cases persisted throughout the study period when awareness of TCM might be expected to have improved.

“This is still an uncommon disease, but it is important to recognize,” agreed Sachin Kumar, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Moderator of the session in which these data were presented, Dr. Kumar indicated that it is important to increase awareness of the condition to accelerate the time to diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Voudris reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Voudris, KV. CRT 2018.

WASHINGTON – Hospitalizations for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy (TCM), a condition that primarily affects postmenopausal women, have been rising steadily, along with rates of in-hospital mortality due to this condition, according to a study conducted with outcomes from the National Inpatient Sample (NIS) database.

The study was presented at CRT 2018, sponsored by the Cardiovascular Research Institute at Washington Hospital Center.

Importantly, a multivariate analysis of predictors of in-hospital mortality based on this database revealed that there were “several potentially reversible causes,” reported Konstantinos V. Voudris, MD, PhD, who is completing a residency in internal medicine at the University of Illinois at Chicago.

TCM, which is characterized by left ventricular apical akinesis and chest pain that mimics the features of acute coronary syndromes (ACS), was first described in 1990 in Japan. The first U.S. case was reported in 1998, but the condition is now well recognized and an ICD code was created for Takotsubo cardiomyopathy in 2007.

There were 72,559 TCM admissions during the study period. When stratified by year, the annual rate of TCM cases rose significantly, from 11.1 to 43.8 per 100,000 hospitalizations from 2007 to 2013.

Although overall in-hospital mortality was 2.5%, it climbed from 1.4% in 2007 to 3.2% in 2013. When compared to patients who did not die during hospitalizations, those who did die were on average older (69.9 vs. 66.4 years; P less than .0001) and had more comorbidities. When a multivariate adjustment was made for baseline clinical risk, the presence of acute kidney injury (AKI), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), peripheral artery disease (PAD), pulmonary hypertension, and arrhythmias remained significant predictors of mortality in patients with TCM.

“We found a number of modifiable and nonmodifiable factors that are associated with a significantly increased mortality, and we think clinicians should be aware of these factors when managing this condition,” Dr. Voudris reported.

Of these risk factors, AKI was associated with the greatest increased odds ratio (OR) with a more than fourfold increased risk of death (OR, 4.18; P less than .001). The presence of PAD (OR, 1.87; P less than .0001) and arrhythmia (OR, 1.88; P less than .0001) almost doubled the risk of in-hospital mortality.

Although females represented 89% of the TCM cases collected during the study period, males with comorbid diseases were at particularly high risk of death, an observation that is consistent with previous reports, according to Dr. Voudris. Relative to women, men were more likely to present with unstable hemodynamics and to develop cardiogenic shock.

Although Dr. Voudris acknowledged that the rising number of hospitalizations for TCM is likely due largely to increasing recognition of this condition, he suggested that there may be other contributing factors to the growing incidence, such as the aging of the U.S. population. He noted that the rise in cases persisted throughout the study period when awareness of TCM might be expected to have improved.

“This is still an uncommon disease, but it is important to recognize,” agreed Sachin Kumar, MD, an interventional cardiologist at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston. Moderator of the session in which these data were presented, Dr. Kumar indicated that it is important to increase awareness of the condition to accelerate the time to diagnosis and treatment.

Dr. Voudris reported no financial relationships relevant to this study.

SOURCE: Voudris, KV. CRT 2018.

REPORTING FROM CRT 2018

Key clinical point: The Takotsubo cardiomyopathy hospitalization and mortality rates have increased in the United States, according to national data.

Major finding: From 2007 to 2013, Takotsubo cases rose from 11.1 to 43.8 cases per 100,000 hospitalizations and in-hospital mortality more than doubled.

Data source: Retrospective national database analysis.

Disclosures: Dr. Voudris reports no financial relationships relevant to this study.

Source: Voudris, KV. CRT 2018.

The Science Behind Monoclonal Antibodies: What Neurologists Need to Know

Click Here to Read the Content.

Topics in this content include:

- Target-related and non-specific toxicity of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

- Research in antibody-based therapeutics

- Differences between therapeutic mAbs and small-molecule therapies

Click Here to Read the Content.

Topics in this content include:

- Target-related and non-specific toxicity of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

- Research in antibody-based therapeutics

- Differences between therapeutic mAbs and small-molecule therapies

Click Here to Read the Content.

Topics in this content include:

- Target-related and non-specific toxicity of therapeutic monoclonal antibodies (mAbs)

- Research in antibody-based therapeutics

- Differences between therapeutic mAbs and small-molecule therapies

VIDEO: It is an exciting time in obesity treatment

BOSTON – For those in obesity treatment, things are looking up, said Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, MSc, in a video interview at the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. There are several new therapies to choose from, said Dr. Sharaiha, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University, New York – and a variety of therapies coming down the pipeline. The key is to choose the right treatment, or right combination of treatments – surgical, endoscopic, or medical – for the right patient at the right time and to follow up. Obesity is a chronic disease that needs long-term, team treatment. With obesity treatments there is sometimes a trade-off between risk and results, but the innovations coming along may balance that risk-results equation for some patients, she said.

BOSTON – For those in obesity treatment, things are looking up, said Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, MSc, in a video interview at the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. There are several new therapies to choose from, said Dr. Sharaiha, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University, New York – and a variety of therapies coming down the pipeline. The key is to choose the right treatment, or right combination of treatments – surgical, endoscopic, or medical – for the right patient at the right time and to follow up. Obesity is a chronic disease that needs long-term, team treatment. With obesity treatments there is sometimes a trade-off between risk and results, but the innovations coming along may balance that risk-results equation for some patients, she said.

BOSTON – For those in obesity treatment, things are looking up, said Reem Z. Sharaiha, MD, MSc, in a video interview at the AGA Tech Summit, sponsored by the AGA Center for GI Innovation and Technology. There are several new therapies to choose from, said Dr. Sharaiha, assistant professor of medicine at Cornell University, New York – and a variety of therapies coming down the pipeline. The key is to choose the right treatment, or right combination of treatments – surgical, endoscopic, or medical – for the right patient at the right time and to follow up. Obesity is a chronic disease that needs long-term, team treatment. With obesity treatments there is sometimes a trade-off between risk and results, but the innovations coming along may balance that risk-results equation for some patients, she said.

REPORTING FROM 2018 AGA TECH SUMMIT

Study links mumps outbreaks to vaccine waning

A new study links recent mumps outbreaks to the waning of the mumps vaccine – which researchers believe wears off in an average of 27 years – and not to heterologous virus genotypes.

“These observations indicate the need for either innovative clinical trial designs to measure the benefit of extending vaccine dosing schedules or new vaccines to address the problem of waning vaccine-induced protection,” the study authors wrote. The findings appeared in Science Translational Medicine.

The numbers over the past 2 years are the highest numbers by far since 2000, with the exception of 2006. The CDC attributes the 2016 and 2017 numbers to factors such as “the known effectiveness of the vaccine, waning immunity following vaccination, and the intensity of exposure to the virus in close-contact settings [such as a college campus] coupled with behaviors that increase the risk of transmission.”

This year, as of Feb. 24, the CDC stated that it has received reports of 304 cases in 32 states and Washington.

For the new study, Joseph A. Lewnard, PhD, and Yonatan H. Grad, MD, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, examined six studies and estimated that mumps vaccinations provide protection for an average of 27 years (95% confidence interval, 16-51 years). They also reported finding no evidence that the effectiveness of vaccines was affected by new heterologous virus genotypes.

Their analysis also determined that outbreaks in the late 1980s and early 1990s (among teens), and from 2006 to present (in young adults), “aligned with peaks in mumps susceptibility of these age groups predicted to be due to loss of vaccine-derived protection.”

The authors suggested that third doses of vaccine or an improved mumps vaccine could provide added protection. “Although congregated U.S. military populations resemble high-risk groups based on their age distribution and close-contact environments, no outbreaks have been reported in the military since a policy of administering an MMR dose to incoming recruits, regardless of vaccination history, was adopted in 1991,” the researchers wrote, referring to a 2008 study (Vaccine 2008, 26:494-501).

For now, however, “we expect population susceptibility to mumps to continue increasing as transient vaccine-derived immunity supersedes previous infection as the main determinant of mumps susceptibility in the U.S. population,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by awards from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The study authors report grant funding (Pfizer) and consulting (Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline) for work unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Lenward JA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Mar 21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao5945.

A new study links recent mumps outbreaks to the waning of the mumps vaccine – which researchers believe wears off in an average of 27 years – and not to heterologous virus genotypes.

“These observations indicate the need for either innovative clinical trial designs to measure the benefit of extending vaccine dosing schedules or new vaccines to address the problem of waning vaccine-induced protection,” the study authors wrote. The findings appeared in Science Translational Medicine.

The numbers over the past 2 years are the highest numbers by far since 2000, with the exception of 2006. The CDC attributes the 2016 and 2017 numbers to factors such as “the known effectiveness of the vaccine, waning immunity following vaccination, and the intensity of exposure to the virus in close-contact settings [such as a college campus] coupled with behaviors that increase the risk of transmission.”

This year, as of Feb. 24, the CDC stated that it has received reports of 304 cases in 32 states and Washington.

For the new study, Joseph A. Lewnard, PhD, and Yonatan H. Grad, MD, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, examined six studies and estimated that mumps vaccinations provide protection for an average of 27 years (95% confidence interval, 16-51 years). They also reported finding no evidence that the effectiveness of vaccines was affected by new heterologous virus genotypes.

Their analysis also determined that outbreaks in the late 1980s and early 1990s (among teens), and from 2006 to present (in young adults), “aligned with peaks in mumps susceptibility of these age groups predicted to be due to loss of vaccine-derived protection.”

The authors suggested that third doses of vaccine or an improved mumps vaccine could provide added protection. “Although congregated U.S. military populations resemble high-risk groups based on their age distribution and close-contact environments, no outbreaks have been reported in the military since a policy of administering an MMR dose to incoming recruits, regardless of vaccination history, was adopted in 1991,” the researchers wrote, referring to a 2008 study (Vaccine 2008, 26:494-501).

For now, however, “we expect population susceptibility to mumps to continue increasing as transient vaccine-derived immunity supersedes previous infection as the main determinant of mumps susceptibility in the U.S. population,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by awards from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The study authors report grant funding (Pfizer) and consulting (Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline) for work unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Lenward JA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Mar 21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao5945.

A new study links recent mumps outbreaks to the waning of the mumps vaccine – which researchers believe wears off in an average of 27 years – and not to heterologous virus genotypes.

“These observations indicate the need for either innovative clinical trial designs to measure the benefit of extending vaccine dosing schedules or new vaccines to address the problem of waning vaccine-induced protection,” the study authors wrote. The findings appeared in Science Translational Medicine.

The numbers over the past 2 years are the highest numbers by far since 2000, with the exception of 2006. The CDC attributes the 2016 and 2017 numbers to factors such as “the known effectiveness of the vaccine, waning immunity following vaccination, and the intensity of exposure to the virus in close-contact settings [such as a college campus] coupled with behaviors that increase the risk of transmission.”

This year, as of Feb. 24, the CDC stated that it has received reports of 304 cases in 32 states and Washington.

For the new study, Joseph A. Lewnard, PhD, and Yonatan H. Grad, MD, PhD, of the Harvard School of Public Health, Boston, examined six studies and estimated that mumps vaccinations provide protection for an average of 27 years (95% confidence interval, 16-51 years). They also reported finding no evidence that the effectiveness of vaccines was affected by new heterologous virus genotypes.

Their analysis also determined that outbreaks in the late 1980s and early 1990s (among teens), and from 2006 to present (in young adults), “aligned with peaks in mumps susceptibility of these age groups predicted to be due to loss of vaccine-derived protection.”

The authors suggested that third doses of vaccine or an improved mumps vaccine could provide added protection. “Although congregated U.S. military populations resemble high-risk groups based on their age distribution and close-contact environments, no outbreaks have been reported in the military since a policy of administering an MMR dose to incoming recruits, regardless of vaccination history, was adopted in 1991,” the researchers wrote, referring to a 2008 study (Vaccine 2008, 26:494-501).

For now, however, “we expect population susceptibility to mumps to continue increasing as transient vaccine-derived immunity supersedes previous infection as the main determinant of mumps susceptibility in the U.S. population,” the authors wrote.

The study was funded by awards from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences and the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation. The study authors report grant funding (Pfizer) and consulting (Pfizer, GlaxoSmithKline) for work unrelated to the study.

SOURCE: Lenward JA et al. Sci Transl Med. 2018 Mar 21. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aao5945.

FROM SCIENCE TRANSLATIONAL MEDICINE