User login

How Do Type 2 Diabetes and Thyroid Disorder Interact?

Although studies have examined the relationship between thyroid disorder (TD) and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), the information on TD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is limited, say researchers from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and Aja University of Medical Science in Tehran, Iran, who report on an 11-year follow-up from the Tehran Thyroid Study. However, undetected TDs may compromise metabolic control of patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), impaired glucose tolerance, or impaired fasting glucose, the researchers point out. Undetected TDs also may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases. And DM and prediabetes can affect thyroid tests.

The researchers evaluated 435 patients with DM, 286 with prediabetes, and 989 healthy controls. They conducted follow-up assessments every 3 years. About 19% of both the diabetic and prediabetic groups had TD, as did about 14% of the healthy controls. However, after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, blood pressure, body mass index, thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb), thyrotropin (TSH), insulin resistance index, triglycerides, and cholesterol, no significant difference was found among the 3 groups. The mean incidence of TD was 14, 18, and 21 per 1000 patients per year in patients with DM, prediabetes, and healthy controls, respectively.

As in other studies, subclinical hypothyroidism and clinical hyperthyroidism were the most and the least common TD in patients with DM. Baseline TSH > 1.94 mU/L was predictive of TD with 70% sensitivity and specificity and had better predictive value than TPOAb . The researchers say conducting screening tests in all patients is not recommended except in those with TPOAb ≥ 401 U/mL or TSH > 1.94 mU/L.

Source:

Gholampour Dehaki M, Amouzegar A, Delshad H, Mehrabi Y, Tohidi M, Azizi F. PLoS One. 2017;12(10): e0184808.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184808.

Although studies have examined the relationship between thyroid disorder (TD) and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), the information on TD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is limited, say researchers from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and Aja University of Medical Science in Tehran, Iran, who report on an 11-year follow-up from the Tehran Thyroid Study. However, undetected TDs may compromise metabolic control of patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), impaired glucose tolerance, or impaired fasting glucose, the researchers point out. Undetected TDs also may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases. And DM and prediabetes can affect thyroid tests.

The researchers evaluated 435 patients with DM, 286 with prediabetes, and 989 healthy controls. They conducted follow-up assessments every 3 years. About 19% of both the diabetic and prediabetic groups had TD, as did about 14% of the healthy controls. However, after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, blood pressure, body mass index, thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb), thyrotropin (TSH), insulin resistance index, triglycerides, and cholesterol, no significant difference was found among the 3 groups. The mean incidence of TD was 14, 18, and 21 per 1000 patients per year in patients with DM, prediabetes, and healthy controls, respectively.

As in other studies, subclinical hypothyroidism and clinical hyperthyroidism were the most and the least common TD in patients with DM. Baseline TSH > 1.94 mU/L was predictive of TD with 70% sensitivity and specificity and had better predictive value than TPOAb . The researchers say conducting screening tests in all patients is not recommended except in those with TPOAb ≥ 401 U/mL or TSH > 1.94 mU/L.

Source:

Gholampour Dehaki M, Amouzegar A, Delshad H, Mehrabi Y, Tohidi M, Azizi F. PLoS One. 2017;12(10): e0184808.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184808.

Although studies have examined the relationship between thyroid disorder (TD) and type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM), the information on TD and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is limited, say researchers from Shahid Beheshti University of Medical Sciences and Aja University of Medical Science in Tehran, Iran, who report on an 11-year follow-up from the Tehran Thyroid Study. However, undetected TDs may compromise metabolic control of patients with diabetes mellitus (DM), impaired glucose tolerance, or impaired fasting glucose, the researchers point out. Undetected TDs also may increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases. And DM and prediabetes can affect thyroid tests.

The researchers evaluated 435 patients with DM, 286 with prediabetes, and 989 healthy controls. They conducted follow-up assessments every 3 years. About 19% of both the diabetic and prediabetic groups had TD, as did about 14% of the healthy controls. However, after adjusting for age, sex, smoking, blood pressure, body mass index, thyroid peroxidase antibody (TPOAb), thyrotropin (TSH), insulin resistance index, triglycerides, and cholesterol, no significant difference was found among the 3 groups. The mean incidence of TD was 14, 18, and 21 per 1000 patients per year in patients with DM, prediabetes, and healthy controls, respectively.

As in other studies, subclinical hypothyroidism and clinical hyperthyroidism were the most and the least common TD in patients with DM. Baseline TSH > 1.94 mU/L was predictive of TD with 70% sensitivity and specificity and had better predictive value than TPOAb . The researchers say conducting screening tests in all patients is not recommended except in those with TPOAb ≥ 401 U/mL or TSH > 1.94 mU/L.

Source:

Gholampour Dehaki M, Amouzegar A, Delshad H, Mehrabi Y, Tohidi M, Azizi F. PLoS One. 2017;12(10): e0184808.

doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0184808.

Eltrombopag can control ITP long-term, study suggests

Eltrombopag can provide long-term disease control for chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to research published in Blood.

In the EXTEND study, investigators evaluated patients exposed to eltrombopag for a median of 2.4 years.

Most patients achieved a response to the drug, and more than half of them maintained that response for at least 25 weeks.

More than a third of patients were able to discontinue at least 1 concomitant ITP medication.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2. However, 32% of patients had serious AEs, and 14% of patients withdrew from the study due to AEs.

This research was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the company that previously owned eltrombopag. Now, the drug is a product of Novartis.

Patients

EXTEND is an open-label extension study of 4 trials (TRA100773A, TRA100773B, TRA102537/RAISE, and TRA108057/REPEAT), which enrolled 302 adults with chronic/persistent ITP.

Patients had completed the treatment and follow-up periods as defined in their previous study protocol and did not experience eltrombopag-related toxicity or other drug intolerance on a prior eltrombopag study. Patients who discontinued a previous study due to toxicity were only eligible if they had received a placebo.

The patients’ median time from diagnosis to enrollment in EXTEND was 58.8 months (range, 9-552). Their median age was 50 (range, 18-86), and 67% were female.

Most patients (70%) had a baseline platelet count below 30×109/L. Thirty-three percent of patients were using concomitant ITP medications, 53% had received at least 3 prior ITP treatments, and 38% had undergone splenectomy.

Treatment

Eltrombopag was started at a dose of 50 mg/day and titrated to 25-75 mg/day or less often based on platelet counts. Maintenance dosing continued after minimization of concomitant ITP medication and optimization of eltrombopag dosing.

The overall median duration of eltrombopag exposure was 2.37 years (range, 2 days to 8.76 years), and the mean average daily dose was 50.2 mg/day (range, 1-75).

One hundred and thirty-five patients (45%) completed the study, and 75 patients (25%) were treated for 4 or more years. The most common reasons for study withdrawal included AEs (n=41), patient decision (n=39), lack of efficacy (n=32), and “other” reasons (n=39).

Safety

AEs leading to study withdrawal (occurring at least twice) included hepatobiliary AEs (n=7), cataracts (n=4), deep vein thrombosis (n=3), cerebral infarction (n=2), headache (n=2), and myelofibrosis (n=2).

The overall incidence of AEs was 92%. The most frequent AEs were headache (28%), nasopharyngitis (25%), and upper respiratory tract infection (23%).

Twenty-six percent of patients had grade 3 AEs, 6% had grade 4 AEs, and 32% had serious AEs. Serious AEs included cataracts (5%), pneumonia (3%), anemia (2%), ALT increase (2%), epistaxis (1%), AST increase, (1%), bilirubin increase (1%), and deep vein thrombosis (1%).

Three percent of patients reported a malignancy while on study, including basal cell carcinoma, intramucosal adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, metastases to the lung, ovarian cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, lymphoma, unclassifiable B-cell lymphoma (low grade), and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Efficacy

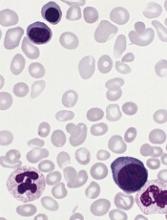

In all, 85.8% (259/302) of patients had a response to eltrombopag, which was defined as achieving a platelet count of at least 50×109/L at least once without rescue therapy.

Fifty-two percent (133/257) of patients achieved a continuous response lasting at least 25 weeks.

Thirty-four percent (34/101) of patients who were on concomitant ITP medication discontinued at least 1 medication. Thirty-nine percent (39/101) reduced or permanently stopped at least 1 ITP medication without receiving rescue therapy.

Fifty-seven percent of patients (171/302) had bleeding symptoms at baseline. This decreased to 16% (13/80) at 1 year.

“The EXTEND data published in Blood validate [eltrombopag] as an important oral treatment option that, by often increasing platelet counts, significantly decreased bleeding rates and reduced the need for concurrent therapies in certain patients with chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia,” said study author James Bussel, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

“With this information, physicians can better optimize long-term disease management for appropriate patients living with this chronic disease.” ![]()

Eltrombopag can provide long-term disease control for chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to research published in Blood.

In the EXTEND study, investigators evaluated patients exposed to eltrombopag for a median of 2.4 years.

Most patients achieved a response to the drug, and more than half of them maintained that response for at least 25 weeks.

More than a third of patients were able to discontinue at least 1 concomitant ITP medication.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2. However, 32% of patients had serious AEs, and 14% of patients withdrew from the study due to AEs.

This research was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the company that previously owned eltrombopag. Now, the drug is a product of Novartis.

Patients

EXTEND is an open-label extension study of 4 trials (TRA100773A, TRA100773B, TRA102537/RAISE, and TRA108057/REPEAT), which enrolled 302 adults with chronic/persistent ITP.

Patients had completed the treatment and follow-up periods as defined in their previous study protocol and did not experience eltrombopag-related toxicity or other drug intolerance on a prior eltrombopag study. Patients who discontinued a previous study due to toxicity were only eligible if they had received a placebo.

The patients’ median time from diagnosis to enrollment in EXTEND was 58.8 months (range, 9-552). Their median age was 50 (range, 18-86), and 67% were female.

Most patients (70%) had a baseline platelet count below 30×109/L. Thirty-three percent of patients were using concomitant ITP medications, 53% had received at least 3 prior ITP treatments, and 38% had undergone splenectomy.

Treatment

Eltrombopag was started at a dose of 50 mg/day and titrated to 25-75 mg/day or less often based on platelet counts. Maintenance dosing continued after minimization of concomitant ITP medication and optimization of eltrombopag dosing.

The overall median duration of eltrombopag exposure was 2.37 years (range, 2 days to 8.76 years), and the mean average daily dose was 50.2 mg/day (range, 1-75).

One hundred and thirty-five patients (45%) completed the study, and 75 patients (25%) were treated for 4 or more years. The most common reasons for study withdrawal included AEs (n=41), patient decision (n=39), lack of efficacy (n=32), and “other” reasons (n=39).

Safety

AEs leading to study withdrawal (occurring at least twice) included hepatobiliary AEs (n=7), cataracts (n=4), deep vein thrombosis (n=3), cerebral infarction (n=2), headache (n=2), and myelofibrosis (n=2).

The overall incidence of AEs was 92%. The most frequent AEs were headache (28%), nasopharyngitis (25%), and upper respiratory tract infection (23%).

Twenty-six percent of patients had grade 3 AEs, 6% had grade 4 AEs, and 32% had serious AEs. Serious AEs included cataracts (5%), pneumonia (3%), anemia (2%), ALT increase (2%), epistaxis (1%), AST increase, (1%), bilirubin increase (1%), and deep vein thrombosis (1%).

Three percent of patients reported a malignancy while on study, including basal cell carcinoma, intramucosal adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, metastases to the lung, ovarian cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, lymphoma, unclassifiable B-cell lymphoma (low grade), and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Efficacy

In all, 85.8% (259/302) of patients had a response to eltrombopag, which was defined as achieving a platelet count of at least 50×109/L at least once without rescue therapy.

Fifty-two percent (133/257) of patients achieved a continuous response lasting at least 25 weeks.

Thirty-four percent (34/101) of patients who were on concomitant ITP medication discontinued at least 1 medication. Thirty-nine percent (39/101) reduced or permanently stopped at least 1 ITP medication without receiving rescue therapy.

Fifty-seven percent of patients (171/302) had bleeding symptoms at baseline. This decreased to 16% (13/80) at 1 year.

“The EXTEND data published in Blood validate [eltrombopag] as an important oral treatment option that, by often increasing platelet counts, significantly decreased bleeding rates and reduced the need for concurrent therapies in certain patients with chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia,” said study author James Bussel, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

“With this information, physicians can better optimize long-term disease management for appropriate patients living with this chronic disease.” ![]()

Eltrombopag can provide long-term disease control for chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia (ITP), according to research published in Blood.

In the EXTEND study, investigators evaluated patients exposed to eltrombopag for a median of 2.4 years.

Most patients achieved a response to the drug, and more than half of them maintained that response for at least 25 weeks.

More than a third of patients were able to discontinue at least 1 concomitant ITP medication.

Most adverse events (AEs) were grade 1 or 2. However, 32% of patients had serious AEs, and 14% of patients withdrew from the study due to AEs.

This research was sponsored by GlaxoSmithKline, the company that previously owned eltrombopag. Now, the drug is a product of Novartis.

Patients

EXTEND is an open-label extension study of 4 trials (TRA100773A, TRA100773B, TRA102537/RAISE, and TRA108057/REPEAT), which enrolled 302 adults with chronic/persistent ITP.

Patients had completed the treatment and follow-up periods as defined in their previous study protocol and did not experience eltrombopag-related toxicity or other drug intolerance on a prior eltrombopag study. Patients who discontinued a previous study due to toxicity were only eligible if they had received a placebo.

The patients’ median time from diagnosis to enrollment in EXTEND was 58.8 months (range, 9-552). Their median age was 50 (range, 18-86), and 67% were female.

Most patients (70%) had a baseline platelet count below 30×109/L. Thirty-three percent of patients were using concomitant ITP medications, 53% had received at least 3 prior ITP treatments, and 38% had undergone splenectomy.

Treatment

Eltrombopag was started at a dose of 50 mg/day and titrated to 25-75 mg/day or less often based on platelet counts. Maintenance dosing continued after minimization of concomitant ITP medication and optimization of eltrombopag dosing.

The overall median duration of eltrombopag exposure was 2.37 years (range, 2 days to 8.76 years), and the mean average daily dose was 50.2 mg/day (range, 1-75).

One hundred and thirty-five patients (45%) completed the study, and 75 patients (25%) were treated for 4 or more years. The most common reasons for study withdrawal included AEs (n=41), patient decision (n=39), lack of efficacy (n=32), and “other” reasons (n=39).

Safety

AEs leading to study withdrawal (occurring at least twice) included hepatobiliary AEs (n=7), cataracts (n=4), deep vein thrombosis (n=3), cerebral infarction (n=2), headache (n=2), and myelofibrosis (n=2).

The overall incidence of AEs was 92%. The most frequent AEs were headache (28%), nasopharyngitis (25%), and upper respiratory tract infection (23%).

Twenty-six percent of patients had grade 3 AEs, 6% had grade 4 AEs, and 32% had serious AEs. Serious AEs included cataracts (5%), pneumonia (3%), anemia (2%), ALT increase (2%), epistaxis (1%), AST increase, (1%), bilirubin increase (1%), and deep vein thrombosis (1%).

Three percent of patients reported a malignancy while on study, including basal cell carcinoma, intramucosal adenocarcinoma, breast cancer, metastases to the lung, ovarian cancer, squamous cell carcinoma, transitional cell carcinoma, lymphoma, unclassifiable B-cell lymphoma (low grade), and Hodgkin lymphoma.

Efficacy

In all, 85.8% (259/302) of patients had a response to eltrombopag, which was defined as achieving a platelet count of at least 50×109/L at least once without rescue therapy.

Fifty-two percent (133/257) of patients achieved a continuous response lasting at least 25 weeks.

Thirty-four percent (34/101) of patients who were on concomitant ITP medication discontinued at least 1 medication. Thirty-nine percent (39/101) reduced or permanently stopped at least 1 ITP medication without receiving rescue therapy.

Fifty-seven percent of patients (171/302) had bleeding symptoms at baseline. This decreased to 16% (13/80) at 1 year.

“The EXTEND data published in Blood validate [eltrombopag] as an important oral treatment option that, by often increasing platelet counts, significantly decreased bleeding rates and reduced the need for concurrent therapies in certain patients with chronic/persistent immune thrombocytopenia,” said study author James Bussel, MD, of Weill Cornell Medicine in New York, New York.

“With this information, physicians can better optimize long-term disease management for appropriate patients living with this chronic disease.” ![]()

What we don’t know about BIA-ALCL

Results of a systematic review suggest a need for more research and long-term follow-up of patients with breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL).

Although data suggest BIA-ALCL is likely associated with textured implants and may result from chronic inflammation, neither of these theories has been confirmed.

Furthermore, researchers have yet to establish optimal prognostic and treatment guidelines for BIA-ALCL.

Dino Ravnic, DO, of Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues highlighted these areas of need in an article published in JAMA Surgery.

The team conducted a literature review to learn more about the development, risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of BIA-ALCL. They reviewed data from 115 articles and 95 patients.

The researchers noted that the incidence of BIA-ALCL is unknown. The Association of Breast Surgery estimates an incidence of 1 in 300,000 breast implants, while the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration estimates BIA-ALCL could affect between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 10,000 women with breast implants.

“We’re seeing that this cancer is likely very underreported, and, as more information on this type of cancer comes to light, the number of cases is likely to increase in the coming years,” Dr Ravnic said.

He and his colleagues noted that almost all documented cases of BIA-ALCL have been associated with textured implants. These implants rose in popularity in the 1990s, and the first case of BIA-ALCL was documented in 1997.

The researchers said that because they could find no incidents of BIA-ALCL prior to the introduction of textured implants, this suggests a causal relationship, but more research is needed to confirm this theory.

“We’re still exploring the exact causes, but according to current knowledge, this cancer only really started to appear after textured implants came on the market in the 1990s,” Dr Ravnic said.

“All manufacturers of textured implants have had cases linked to this type of lymphoma, and we haven’t seen cases linked to smooth implants. But, in many of these cases, the implant was removed without testing the surrounding fluid and tissue for lymphoma cells, so it’s difficult to definitively correlate the two.”

The researchers also said the evidence suggests BIA-ALCL may occur as a result of inflammation surrounding the breast implant, and tissue that grows into pores in the textured implant may prolong inflammation.

Chronic inflammation may lead to malignant transformation of T cells that are anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative and CD30-positive.

The data also suggest BIA-ALCL tends to develop slowly. The mean time to BIA-ALCL presentation in the 95 patients analyzed was about 10 years after the patients received their implants.

The researchers said treatment of BIA-ALCL must include removal of the implant and surrounding capsule. However, patients with advanced disease—including a tumor mass (stage II), lymph node involvement (stage II/III), or distant disease (stage IV)—may require chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both. Brentuximab vedotin has also been used.

Overall, the patients included in this review appeared to have a good prognosis, with only 5 patients experiencing disease recurrence and dying of BIA-ALCL.

However, the researchers noted that it was difficult to calculate the mean overall survival and disease-free survival of these patients due to a lack of data and inadequate follow-up. ![]()

Results of a systematic review suggest a need for more research and long-term follow-up of patients with breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL).

Although data suggest BIA-ALCL is likely associated with textured implants and may result from chronic inflammation, neither of these theories has been confirmed.

Furthermore, researchers have yet to establish optimal prognostic and treatment guidelines for BIA-ALCL.

Dino Ravnic, DO, of Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues highlighted these areas of need in an article published in JAMA Surgery.

The team conducted a literature review to learn more about the development, risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of BIA-ALCL. They reviewed data from 115 articles and 95 patients.

The researchers noted that the incidence of BIA-ALCL is unknown. The Association of Breast Surgery estimates an incidence of 1 in 300,000 breast implants, while the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration estimates BIA-ALCL could affect between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 10,000 women with breast implants.

“We’re seeing that this cancer is likely very underreported, and, as more information on this type of cancer comes to light, the number of cases is likely to increase in the coming years,” Dr Ravnic said.

He and his colleagues noted that almost all documented cases of BIA-ALCL have been associated with textured implants. These implants rose in popularity in the 1990s, and the first case of BIA-ALCL was documented in 1997.

The researchers said that because they could find no incidents of BIA-ALCL prior to the introduction of textured implants, this suggests a causal relationship, but more research is needed to confirm this theory.

“We’re still exploring the exact causes, but according to current knowledge, this cancer only really started to appear after textured implants came on the market in the 1990s,” Dr Ravnic said.

“All manufacturers of textured implants have had cases linked to this type of lymphoma, and we haven’t seen cases linked to smooth implants. But, in many of these cases, the implant was removed without testing the surrounding fluid and tissue for lymphoma cells, so it’s difficult to definitively correlate the two.”

The researchers also said the evidence suggests BIA-ALCL may occur as a result of inflammation surrounding the breast implant, and tissue that grows into pores in the textured implant may prolong inflammation.

Chronic inflammation may lead to malignant transformation of T cells that are anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative and CD30-positive.

The data also suggest BIA-ALCL tends to develop slowly. The mean time to BIA-ALCL presentation in the 95 patients analyzed was about 10 years after the patients received their implants.

The researchers said treatment of BIA-ALCL must include removal of the implant and surrounding capsule. However, patients with advanced disease—including a tumor mass (stage II), lymph node involvement (stage II/III), or distant disease (stage IV)—may require chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both. Brentuximab vedotin has also been used.

Overall, the patients included in this review appeared to have a good prognosis, with only 5 patients experiencing disease recurrence and dying of BIA-ALCL.

However, the researchers noted that it was difficult to calculate the mean overall survival and disease-free survival of these patients due to a lack of data and inadequate follow-up. ![]()

Results of a systematic review suggest a need for more research and long-term follow-up of patients with breast implant-associated anaplastic large-cell lymphoma (BIA-ALCL).

Although data suggest BIA-ALCL is likely associated with textured implants and may result from chronic inflammation, neither of these theories has been confirmed.

Furthermore, researchers have yet to establish optimal prognostic and treatment guidelines for BIA-ALCL.

Dino Ravnic, DO, of Penn State Health Milton S. Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and his colleagues highlighted these areas of need in an article published in JAMA Surgery.

The team conducted a literature review to learn more about the development, risk factors, diagnosis, and treatment of BIA-ALCL. They reviewed data from 115 articles and 95 patients.

The researchers noted that the incidence of BIA-ALCL is unknown. The Association of Breast Surgery estimates an incidence of 1 in 300,000 breast implants, while the Australian Therapeutic Goods Administration estimates BIA-ALCL could affect between 1 in 1000 and 1 in 10,000 women with breast implants.

“We’re seeing that this cancer is likely very underreported, and, as more information on this type of cancer comes to light, the number of cases is likely to increase in the coming years,” Dr Ravnic said.

He and his colleagues noted that almost all documented cases of BIA-ALCL have been associated with textured implants. These implants rose in popularity in the 1990s, and the first case of BIA-ALCL was documented in 1997.

The researchers said that because they could find no incidents of BIA-ALCL prior to the introduction of textured implants, this suggests a causal relationship, but more research is needed to confirm this theory.

“We’re still exploring the exact causes, but according to current knowledge, this cancer only really started to appear after textured implants came on the market in the 1990s,” Dr Ravnic said.

“All manufacturers of textured implants have had cases linked to this type of lymphoma, and we haven’t seen cases linked to smooth implants. But, in many of these cases, the implant was removed without testing the surrounding fluid and tissue for lymphoma cells, so it’s difficult to definitively correlate the two.”

The researchers also said the evidence suggests BIA-ALCL may occur as a result of inflammation surrounding the breast implant, and tissue that grows into pores in the textured implant may prolong inflammation.

Chronic inflammation may lead to malignant transformation of T cells that are anaplastic lymphoma kinase-negative and CD30-positive.

The data also suggest BIA-ALCL tends to develop slowly. The mean time to BIA-ALCL presentation in the 95 patients analyzed was about 10 years after the patients received their implants.

The researchers said treatment of BIA-ALCL must include removal of the implant and surrounding capsule. However, patients with advanced disease—including a tumor mass (stage II), lymph node involvement (stage II/III), or distant disease (stage IV)—may require chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both. Brentuximab vedotin has also been used.

Overall, the patients included in this review appeared to have a good prognosis, with only 5 patients experiencing disease recurrence and dying of BIA-ALCL.

However, the researchers noted that it was difficult to calculate the mean overall survival and disease-free survival of these patients due to a lack of data and inadequate follow-up. ![]()

NCCN releases new guidelines for patients with MPNs

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN) has released new guidelines for patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The guidelines include information on the diagnosis and treatment of polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis.

NCCN Guidelines for Patients® are written in plain language and include tools such as suggested questions for doctors, a glossary of terms, and medical illustrations of anatomy, tests, and treatment.

NCCN also provides accompanying Quick Guide™ sheets, which are short summaries of key points in the guidelines.

The patient guidelines and Quick Guide sheet for MPNs are available to read and download for free from the NCCN website and via the NCCN Patient Guides for Cancer mobile app. Printed editions can be ordered from Amazon.com for a fee.

“As a physician, I find it makes a difference when patients and caregivers have access to the information they need when making treatment decisions, to complement what they’re hearing from me,” said Brady L. Stein, MD, an associate professor at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, and a member of the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Panel for MPN.

“Sitting in the hematologists’ office can be an overwhelming experience. These patient guidelines provide the most comprehensive at-home resource available for people with these rare diseases. They cover everything from basic explanations to complicated decision-making around diagnostic confirmation, supportive care techniques, treatment sequencing, adverse effects, and more.”

NCCN also has patient guidelines on acute lymphoblastic leukemia, adolescents and young adults with cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia*, distress/supportive care, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma*, myelodysplastic syndromes*, nausea and vomiting/supportive care, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, and a range of solid tumor malignancies. ![]()

*Guidelines with new updates coming soon.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN) has released new guidelines for patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The guidelines include information on the diagnosis and treatment of polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis.

NCCN Guidelines for Patients® are written in plain language and include tools such as suggested questions for doctors, a glossary of terms, and medical illustrations of anatomy, tests, and treatment.

NCCN also provides accompanying Quick Guide™ sheets, which are short summaries of key points in the guidelines.

The patient guidelines and Quick Guide sheet for MPNs are available to read and download for free from the NCCN website and via the NCCN Patient Guides for Cancer mobile app. Printed editions can be ordered from Amazon.com for a fee.

“As a physician, I find it makes a difference when patients and caregivers have access to the information they need when making treatment decisions, to complement what they’re hearing from me,” said Brady L. Stein, MD, an associate professor at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, and a member of the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Panel for MPN.

“Sitting in the hematologists’ office can be an overwhelming experience. These patient guidelines provide the most comprehensive at-home resource available for people with these rare diseases. They cover everything from basic explanations to complicated decision-making around diagnostic confirmation, supportive care techniques, treatment sequencing, adverse effects, and more.”

NCCN also has patient guidelines on acute lymphoblastic leukemia, adolescents and young adults with cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia*, distress/supportive care, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma*, myelodysplastic syndromes*, nausea and vomiting/supportive care, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, and a range of solid tumor malignancies. ![]()

*Guidelines with new updates coming soon.

The National Comprehensive Cancer Network® (NCCN) has released new guidelines for patients with myeloproliferative neoplasms (MPNs).

The guidelines include information on the diagnosis and treatment of polycythemia vera, essential thrombocythemia, and myelofibrosis.

NCCN Guidelines for Patients® are written in plain language and include tools such as suggested questions for doctors, a glossary of terms, and medical illustrations of anatomy, tests, and treatment.

NCCN also provides accompanying Quick Guide™ sheets, which are short summaries of key points in the guidelines.

The patient guidelines and Quick Guide sheet for MPNs are available to read and download for free from the NCCN website and via the NCCN Patient Guides for Cancer mobile app. Printed editions can be ordered from Amazon.com for a fee.

“As a physician, I find it makes a difference when patients and caregivers have access to the information they need when making treatment decisions, to complement what they’re hearing from me,” said Brady L. Stein, MD, an associate professor at Northwestern University in Chicago, Illinois, and a member of the NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology Panel for MPN.

“Sitting in the hematologists’ office can be an overwhelming experience. These patient guidelines provide the most comprehensive at-home resource available for people with these rare diseases. They cover everything from basic explanations to complicated decision-making around diagnostic confirmation, supportive care techniques, treatment sequencing, adverse effects, and more.”

NCCN also has patient guidelines on acute lymphoblastic leukemia, adolescents and young adults with cancer, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, chronic myelogenous leukemia*, distress/supportive care, Hodgkin lymphoma, multiple myeloma*, myelodysplastic syndromes*, nausea and vomiting/supportive care, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia, and a range of solid tumor malignancies. ![]()

*Guidelines with new updates coming soon.

“I’m sorry, doctor, I’m afraid I can’t do that”

In “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the epic 1968 film by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, humanity makes first contact with an alien intelligence, and the course of history is irreversibly altered. Hailed as a watershed moment in science fiction, “2001” was considered way ahead of its time and raised a number of philosophical questions about what would happen if we ever encountered another form of life. Interestingly, the most noteworthy character in the film isn’t human or alien, but instead a new form of life altogether: an artificial intelligence (AI) known as the Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer 9000. HAL (as he is known colloquially) operates the Discovery One spacecraft, ferrying several scientists bound for Jupiter on a mission of exploration. Stating that he is “foolproof and incapable of error,” HAL’s superiority complex leads him to become the film’s antagonist, as he believes that human error is the cause of the difficulties they encounter. He eventually concludes that the best way to complete the mission is to eliminate human interference. When asked by scientist Dr. David Bowman to perform a simple function essential to the survival of the crew, HAL simply states “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.” Bowman is forced to disconnect HAL’s higher intellectual capabilities, reverting the computer to its most basic functions to ensure human survival.

Kubrick and Clarke may have been overly ambitious in predicting the progress of human space flight, but their call for concern over the risks of artificial intelligence seems quite prescient. Recently, billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk (CEO of Tesla Motors and SpaceX) raised his concerns about AI, warning that, left unchecked, AI could be mankind’s final invention – one that could eventually destroy us. Other giants of the tech industry, including Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, disagree. They believe AI represents tremendous promise for humanity and could usher in innovations unlike any we have ever seen.

A few weeks ago, we attended a national electronic health records conference where a well-known EHR vendor unveiled the new features in the upcoming release of their software. One of the most noteworthy additions was an intelligent virtual assistant, designed to help providers care for patients. While this is not the first time AI has ventured into health care (see IBM’s “Watson”), it is the first time the idea has become mainstream and fully integrated into physician workflow. Much like the virtual assistants mentioned above, this one can use voice or mouse/keyboard interaction to find clinical information, simplify common tasks, and help with medical decision-making.

While exciting at first, the idea of artificially intelligent EHRs may sound terrifying to some who aren’t yet ready to trust any patient care to machines. Reassuringly, while the integrated virtual assistant mentioned above can make suggestions to guide physicians to the right data or offer decision support when available, it is primarily focused on interface enhancement to improve work flow. It is not yet capable of making true clinical decisions that remove the physician from care delivery, but computers that do the diagnostic work of physicians may be closer than you think.

Research done at Jefferson University in Philadelphia and published in the August 2017 edition of Radiology1 investigated the ability of deep-learning algorithms to interpret chest radiographs for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. The computers achieved an impressive reliability of 99%. While at first radiograph interpretation seems quite different than the diagnostic decision-making done in primary care, the fundamental skill required for both is similar: pattern recognition. To build those patterns, artificial intelligence requires an enormous number of data points, but that’s hardly a problem thanks to the continual collection of patient data through electronic health records. The amount of raw information available to these algorithms is growing exponentially by the day, and with time their predictive ability will be unmatched. So where will that leave us, the physicians, entrusted for generations with the responsibility of diagnosis? Possibly more satisfied than we are today.

There was a time – not long ago – when the body of available medical knowledge was incredibly limited. Diagnostic testing was primitive and often inaccurate, and the treatment provided by physicians was focused on supporting, communicating, and genuinely caring for patients and their families. In the past 50 years, medical knowledge has exploded, and diagnostic testing has become incredibly advanced. Sadly, at the same time physicians have begun to feel more like clerical workers: entering data, writing prescriptions, and filling out forms. As artificial intelligence assumes some of this busywork and takes much of the guesswork out of diagnosis, physicians may find greater job satisfaction as they provide the skills a computer never can: a human touch, a personal and reflective interpretation of a patient’s diagnosis, and a true emotional connection. Ask this of a computer, and the response will always be the same: “I’m sorry, doctor, I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

Reference

1. Lakhani, Paras & Sundaram, Baskaran, “Deep Learning at Chest Radiography: Automated Classification of Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Using Convolutional Neural Networks,” Radiology. 2017 Aug;284:574-82.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

In “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the epic 1968 film by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, humanity makes first contact with an alien intelligence, and the course of history is irreversibly altered. Hailed as a watershed moment in science fiction, “2001” was considered way ahead of its time and raised a number of philosophical questions about what would happen if we ever encountered another form of life. Interestingly, the most noteworthy character in the film isn’t human or alien, but instead a new form of life altogether: an artificial intelligence (AI) known as the Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer 9000. HAL (as he is known colloquially) operates the Discovery One spacecraft, ferrying several scientists bound for Jupiter on a mission of exploration. Stating that he is “foolproof and incapable of error,” HAL’s superiority complex leads him to become the film’s antagonist, as he believes that human error is the cause of the difficulties they encounter. He eventually concludes that the best way to complete the mission is to eliminate human interference. When asked by scientist Dr. David Bowman to perform a simple function essential to the survival of the crew, HAL simply states “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.” Bowman is forced to disconnect HAL’s higher intellectual capabilities, reverting the computer to its most basic functions to ensure human survival.

Kubrick and Clarke may have been overly ambitious in predicting the progress of human space flight, but their call for concern over the risks of artificial intelligence seems quite prescient. Recently, billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk (CEO of Tesla Motors and SpaceX) raised his concerns about AI, warning that, left unchecked, AI could be mankind’s final invention – one that could eventually destroy us. Other giants of the tech industry, including Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, disagree. They believe AI represents tremendous promise for humanity and could usher in innovations unlike any we have ever seen.

A few weeks ago, we attended a national electronic health records conference where a well-known EHR vendor unveiled the new features in the upcoming release of their software. One of the most noteworthy additions was an intelligent virtual assistant, designed to help providers care for patients. While this is not the first time AI has ventured into health care (see IBM’s “Watson”), it is the first time the idea has become mainstream and fully integrated into physician workflow. Much like the virtual assistants mentioned above, this one can use voice or mouse/keyboard interaction to find clinical information, simplify common tasks, and help with medical decision-making.

While exciting at first, the idea of artificially intelligent EHRs may sound terrifying to some who aren’t yet ready to trust any patient care to machines. Reassuringly, while the integrated virtual assistant mentioned above can make suggestions to guide physicians to the right data or offer decision support when available, it is primarily focused on interface enhancement to improve work flow. It is not yet capable of making true clinical decisions that remove the physician from care delivery, but computers that do the diagnostic work of physicians may be closer than you think.

Research done at Jefferson University in Philadelphia and published in the August 2017 edition of Radiology1 investigated the ability of deep-learning algorithms to interpret chest radiographs for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. The computers achieved an impressive reliability of 99%. While at first radiograph interpretation seems quite different than the diagnostic decision-making done in primary care, the fundamental skill required for both is similar: pattern recognition. To build those patterns, artificial intelligence requires an enormous number of data points, but that’s hardly a problem thanks to the continual collection of patient data through electronic health records. The amount of raw information available to these algorithms is growing exponentially by the day, and with time their predictive ability will be unmatched. So where will that leave us, the physicians, entrusted for generations with the responsibility of diagnosis? Possibly more satisfied than we are today.

There was a time – not long ago – when the body of available medical knowledge was incredibly limited. Diagnostic testing was primitive and often inaccurate, and the treatment provided by physicians was focused on supporting, communicating, and genuinely caring for patients and their families. In the past 50 years, medical knowledge has exploded, and diagnostic testing has become incredibly advanced. Sadly, at the same time physicians have begun to feel more like clerical workers: entering data, writing prescriptions, and filling out forms. As artificial intelligence assumes some of this busywork and takes much of the guesswork out of diagnosis, physicians may find greater job satisfaction as they provide the skills a computer never can: a human touch, a personal and reflective interpretation of a patient’s diagnosis, and a true emotional connection. Ask this of a computer, and the response will always be the same: “I’m sorry, doctor, I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

Reference

1. Lakhani, Paras & Sundaram, Baskaran, “Deep Learning at Chest Radiography: Automated Classification of Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Using Convolutional Neural Networks,” Radiology. 2017 Aug;284:574-82.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

In “2001: A Space Odyssey,” the epic 1968 film by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, humanity makes first contact with an alien intelligence, and the course of history is irreversibly altered. Hailed as a watershed moment in science fiction, “2001” was considered way ahead of its time and raised a number of philosophical questions about what would happen if we ever encountered another form of life. Interestingly, the most noteworthy character in the film isn’t human or alien, but instead a new form of life altogether: an artificial intelligence (AI) known as the Heuristically programmed ALgorithmic computer 9000. HAL (as he is known colloquially) operates the Discovery One spacecraft, ferrying several scientists bound for Jupiter on a mission of exploration. Stating that he is “foolproof and incapable of error,” HAL’s superiority complex leads him to become the film’s antagonist, as he believes that human error is the cause of the difficulties they encounter. He eventually concludes that the best way to complete the mission is to eliminate human interference. When asked by scientist Dr. David Bowman to perform a simple function essential to the survival of the crew, HAL simply states “I’m sorry, Dave, I’m afraid I can’t do that.” Bowman is forced to disconnect HAL’s higher intellectual capabilities, reverting the computer to its most basic functions to ensure human survival.

Kubrick and Clarke may have been overly ambitious in predicting the progress of human space flight, but their call for concern over the risks of artificial intelligence seems quite prescient. Recently, billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk (CEO of Tesla Motors and SpaceX) raised his concerns about AI, warning that, left unchecked, AI could be mankind’s final invention – one that could eventually destroy us. Other giants of the tech industry, including Bill Gates and Mark Zuckerberg, disagree. They believe AI represents tremendous promise for humanity and could usher in innovations unlike any we have ever seen.

A few weeks ago, we attended a national electronic health records conference where a well-known EHR vendor unveiled the new features in the upcoming release of their software. One of the most noteworthy additions was an intelligent virtual assistant, designed to help providers care for patients. While this is not the first time AI has ventured into health care (see IBM’s “Watson”), it is the first time the idea has become mainstream and fully integrated into physician workflow. Much like the virtual assistants mentioned above, this one can use voice or mouse/keyboard interaction to find clinical information, simplify common tasks, and help with medical decision-making.

While exciting at first, the idea of artificially intelligent EHRs may sound terrifying to some who aren’t yet ready to trust any patient care to machines. Reassuringly, while the integrated virtual assistant mentioned above can make suggestions to guide physicians to the right data or offer decision support when available, it is primarily focused on interface enhancement to improve work flow. It is not yet capable of making true clinical decisions that remove the physician from care delivery, but computers that do the diagnostic work of physicians may be closer than you think.

Research done at Jefferson University in Philadelphia and published in the August 2017 edition of Radiology1 investigated the ability of deep-learning algorithms to interpret chest radiographs for the diagnosis of tuberculosis. The computers achieved an impressive reliability of 99%. While at first radiograph interpretation seems quite different than the diagnostic decision-making done in primary care, the fundamental skill required for both is similar: pattern recognition. To build those patterns, artificial intelligence requires an enormous number of data points, but that’s hardly a problem thanks to the continual collection of patient data through electronic health records. The amount of raw information available to these algorithms is growing exponentially by the day, and with time their predictive ability will be unmatched. So where will that leave us, the physicians, entrusted for generations with the responsibility of diagnosis? Possibly more satisfied than we are today.

There was a time – not long ago – when the body of available medical knowledge was incredibly limited. Diagnostic testing was primitive and often inaccurate, and the treatment provided by physicians was focused on supporting, communicating, and genuinely caring for patients and their families. In the past 50 years, medical knowledge has exploded, and diagnostic testing has become incredibly advanced. Sadly, at the same time physicians have begun to feel more like clerical workers: entering data, writing prescriptions, and filling out forms. As artificial intelligence assumes some of this busywork and takes much of the guesswork out of diagnosis, physicians may find greater job satisfaction as they provide the skills a computer never can: a human touch, a personal and reflective interpretation of a patient’s diagnosis, and a true emotional connection. Ask this of a computer, and the response will always be the same: “I’m sorry, doctor, I’m afraid I can’t do that.”

Reference

1. Lakhani, Paras & Sundaram, Baskaran, “Deep Learning at Chest Radiography: Automated Classification of Pulmonary Tuberculosis by Using Convolutional Neural Networks,” Radiology. 2017 Aug;284:574-82.

Dr. Notte is a family physician and clinical informaticist for Abington (Pa.) Memorial Hospital. He is also a partner in EHR Practice Consultants, a firm that aids physicians in adopting electronic health records. Dr. Skolnik is professor of family and community medicine at Sidney Kimmel Medical College, Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, and associate director of the family medicine residency program at Abington Jefferson Health.

CDC: Zika-exposed newborns need intensified eye, hearing, and neurological testing

Infants with possible prenatal Zika exposure who test positive for the virus should receive an in-depth ophthalmologic exam, intensified hearing testing, and a thorough neurological evaluation with brain imaging within 1 month of birth, according to new interim guidance set forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new clinical management guidelines, published in the Oct. 20 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, supersede the most recent CDC guidance, issued in August 2016. The agency deemed the update necessary after a recent convocation sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The meeting drew dozens of practicing clinicians and federal agency representatives, who reviewed the ever-evolving body of knowledge on how to best manage the care of these infants. Since Zika emerged as a public health threat, clinicians have reported postnatal onset of some symptoms, including eye abnormalities, a developing microcephaly in infants with a normal head circumference at birth, EEG abnormalities, and diaphragmatic paralysis.

The guidance focuses on three groups: infants with clinical findings of Zika syndrome born to mothers with possible Zika exposure during pregnancy; infants without clinical findings of Zika syndrome whose mothers had lab-confirmed Zika exposure; and infants without symptoms whose mothers might have been exposed, but who did not have laboratory-confirmed infection (MMWR. 2017 Oct 20;66[41]:1089-120).

Infants with clinical findings consistent with Zika syndrome and mothers with possible prenatal Zika exposure

These infants should be tested for Zika virus with serum and urine tests. If those are negative and there is no other apparent cause of the symptoms, they should have a cerebrospinal fluid sample tested for Zika RNA and IgM Zika antibodies.

By 1 month, these infants need a head ultrasound and a detailed ophthalmologic exam. The eye exam should pick up any anomalies of the anterior and posterior eye, including microphthalmia, coloboma, intraocular calcifications, optic nerve hypoplasia and atrophy, and macular scarring with focal pigmentary retinal mottling.

A comprehensive neurological exam also is part of the recommendation. Seizures are sometimes part of Zika syndrome, but infants can also have subclinical EEG abnormalities. Advanced neuroimaging can identify both obvious and subtle brain abnormalities: cortical thinning, corpus callosum abnormalities, calcifications at the white/gray matter junction, and ventricular enlargement are possible findings.

As infants grow, clinicians should be alert for signs of increased intracranial pressure that could signal postnatal hydrocephalus. Diaphragmatic paralysis also has been seen; this manifests by respiratory distress. Dysphagia that interferes with feeding can develop as well.

The complicated clinical picture calls for a team approach, Dr. Adebanjo said. “The follow-up care of [these infants] requires a multidisciplinary team and an established medical home to facilitate the coordination of care and ensure that abnormal findings are addressed.”

Infants without clinical findings, whose mothers have lab-confirmed Zika exposure

Initially, these infants should have the same early head ultrasound, hearing, and eye exams as those who display clinical findings. All of these infants also should be tested for Zika virus in the same way as those with clinical findings.

If tests return a positive result, they should have all the investigations and follow-ups recommended for babies with clinical findings. If lab testing is negative, and clinical findings are normal, Zika infection is highly unlikely and they can receive routine care, although clinicians and parents should be on the lookout for any new symptoms that might suggest postnatal Zika syndrome.

Infants without clinical findings, whose mothers had possible, but unconfirmed, Zika exposure

This is a varied and large group, which includes women who were never tested during pregnancy, as well as those who could have had a false negative test. “Because the latter issue is not easily discerned, all mothers with possible exposure to Zika virus infection, including those who tested negative with currently available technology, should be considered in this group,” Dr. Adebanjo said.

CDC does not recommend further Zika evaluation for these infants unless additional testing confirms maternal infection. For older infants, parents and clinicians should decide together whether any further evaluations would be helpful. But, Dr. Adebanjo said, “If findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome are identified at any time, referrals to appropriate specialties should be made, and subsequent evaluation should follow recommendations for infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika.”

CDC also reiterated its special recommendations for infants who had a prenatal diagnosis of Zika infection. For now, these remain unchanged from 2016, although “as more data become available, understanding of the diagnostic role of prenatal ultrasound and amniocentesis will improve and guidance will be updated.”

No one has yet identified the optimal timing for a Zika diagnostic ultrasound. CDC recommends serial ultrasounds be done every 3-4 weeks for women with lab-confirmed prenatal Zika exposure. Women with possible exposure need only routine ultrasound screenings.

While Zika RNA has been identified in amniotic fluid, there is no consensus on the value of amniocentesis as a prenatal diagnostic tool. Investigations of serial amniocentesis suggests that viral shedding into the amniotic fluid might be transient. If the procedure is done for other reasons, Zika nucleic acid testing can be incorporated.

A shared decision-making process is key when making screening decisions that should be individually weighed, Dr. Adebanjo said. “For example, serial ultrasounds might be inconvenient, unpleasant, and expensive, and might prompt unnecessary interventions; amniocentesis carries additional known risks such as fetal loss. These potential harms of prenatal screening for congenital Zika syndrome might outweigh the clinical benefits for some patients. Therefore, these decisions should be individualized.”

Neither Dr. Adebanjo nor any of the coauthors had any financial disclosures.

Infants with possible prenatal Zika exposure who test positive for the virus should receive an in-depth ophthalmologic exam, intensified hearing testing, and a thorough neurological evaluation with brain imaging within 1 month of birth, according to new interim guidance set forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new clinical management guidelines, published in the Oct. 20 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, supersede the most recent CDC guidance, issued in August 2016. The agency deemed the update necessary after a recent convocation sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The meeting drew dozens of practicing clinicians and federal agency representatives, who reviewed the ever-evolving body of knowledge on how to best manage the care of these infants. Since Zika emerged as a public health threat, clinicians have reported postnatal onset of some symptoms, including eye abnormalities, a developing microcephaly in infants with a normal head circumference at birth, EEG abnormalities, and diaphragmatic paralysis.

The guidance focuses on three groups: infants with clinical findings of Zika syndrome born to mothers with possible Zika exposure during pregnancy; infants without clinical findings of Zika syndrome whose mothers had lab-confirmed Zika exposure; and infants without symptoms whose mothers might have been exposed, but who did not have laboratory-confirmed infection (MMWR. 2017 Oct 20;66[41]:1089-120).

Infants with clinical findings consistent with Zika syndrome and mothers with possible prenatal Zika exposure

These infants should be tested for Zika virus with serum and urine tests. If those are negative and there is no other apparent cause of the symptoms, they should have a cerebrospinal fluid sample tested for Zika RNA and IgM Zika antibodies.

By 1 month, these infants need a head ultrasound and a detailed ophthalmologic exam. The eye exam should pick up any anomalies of the anterior and posterior eye, including microphthalmia, coloboma, intraocular calcifications, optic nerve hypoplasia and atrophy, and macular scarring with focal pigmentary retinal mottling.

A comprehensive neurological exam also is part of the recommendation. Seizures are sometimes part of Zika syndrome, but infants can also have subclinical EEG abnormalities. Advanced neuroimaging can identify both obvious and subtle brain abnormalities: cortical thinning, corpus callosum abnormalities, calcifications at the white/gray matter junction, and ventricular enlargement are possible findings.

As infants grow, clinicians should be alert for signs of increased intracranial pressure that could signal postnatal hydrocephalus. Diaphragmatic paralysis also has been seen; this manifests by respiratory distress. Dysphagia that interferes with feeding can develop as well.

The complicated clinical picture calls for a team approach, Dr. Adebanjo said. “The follow-up care of [these infants] requires a multidisciplinary team and an established medical home to facilitate the coordination of care and ensure that abnormal findings are addressed.”

Infants without clinical findings, whose mothers have lab-confirmed Zika exposure

Initially, these infants should have the same early head ultrasound, hearing, and eye exams as those who display clinical findings. All of these infants also should be tested for Zika virus in the same way as those with clinical findings.

If tests return a positive result, they should have all the investigations and follow-ups recommended for babies with clinical findings. If lab testing is negative, and clinical findings are normal, Zika infection is highly unlikely and they can receive routine care, although clinicians and parents should be on the lookout for any new symptoms that might suggest postnatal Zika syndrome.

Infants without clinical findings, whose mothers had possible, but unconfirmed, Zika exposure

This is a varied and large group, which includes women who were never tested during pregnancy, as well as those who could have had a false negative test. “Because the latter issue is not easily discerned, all mothers with possible exposure to Zika virus infection, including those who tested negative with currently available technology, should be considered in this group,” Dr. Adebanjo said.

CDC does not recommend further Zika evaluation for these infants unless additional testing confirms maternal infection. For older infants, parents and clinicians should decide together whether any further evaluations would be helpful. But, Dr. Adebanjo said, “If findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome are identified at any time, referrals to appropriate specialties should be made, and subsequent evaluation should follow recommendations for infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika.”

CDC also reiterated its special recommendations for infants who had a prenatal diagnosis of Zika infection. For now, these remain unchanged from 2016, although “as more data become available, understanding of the diagnostic role of prenatal ultrasound and amniocentesis will improve and guidance will be updated.”

No one has yet identified the optimal timing for a Zika diagnostic ultrasound. CDC recommends serial ultrasounds be done every 3-4 weeks for women with lab-confirmed prenatal Zika exposure. Women with possible exposure need only routine ultrasound screenings.

While Zika RNA has been identified in amniotic fluid, there is no consensus on the value of amniocentesis as a prenatal diagnostic tool. Investigations of serial amniocentesis suggests that viral shedding into the amniotic fluid might be transient. If the procedure is done for other reasons, Zika nucleic acid testing can be incorporated.

A shared decision-making process is key when making screening decisions that should be individually weighed, Dr. Adebanjo said. “For example, serial ultrasounds might be inconvenient, unpleasant, and expensive, and might prompt unnecessary interventions; amniocentesis carries additional known risks such as fetal loss. These potential harms of prenatal screening for congenital Zika syndrome might outweigh the clinical benefits for some patients. Therefore, these decisions should be individualized.”

Neither Dr. Adebanjo nor any of the coauthors had any financial disclosures.

Infants with possible prenatal Zika exposure who test positive for the virus should receive an in-depth ophthalmologic exam, intensified hearing testing, and a thorough neurological evaluation with brain imaging within 1 month of birth, according to new interim guidance set forth by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

The new clinical management guidelines, published in the Oct. 20 issue of the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, supersede the most recent CDC guidance, issued in August 2016. The agency deemed the update necessary after a recent convocation sponsored by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. The meeting drew dozens of practicing clinicians and federal agency representatives, who reviewed the ever-evolving body of knowledge on how to best manage the care of these infants. Since Zika emerged as a public health threat, clinicians have reported postnatal onset of some symptoms, including eye abnormalities, a developing microcephaly in infants with a normal head circumference at birth, EEG abnormalities, and diaphragmatic paralysis.

The guidance focuses on three groups: infants with clinical findings of Zika syndrome born to mothers with possible Zika exposure during pregnancy; infants without clinical findings of Zika syndrome whose mothers had lab-confirmed Zika exposure; and infants without symptoms whose mothers might have been exposed, but who did not have laboratory-confirmed infection (MMWR. 2017 Oct 20;66[41]:1089-120).

Infants with clinical findings consistent with Zika syndrome and mothers with possible prenatal Zika exposure

These infants should be tested for Zika virus with serum and urine tests. If those are negative and there is no other apparent cause of the symptoms, they should have a cerebrospinal fluid sample tested for Zika RNA and IgM Zika antibodies.

By 1 month, these infants need a head ultrasound and a detailed ophthalmologic exam. The eye exam should pick up any anomalies of the anterior and posterior eye, including microphthalmia, coloboma, intraocular calcifications, optic nerve hypoplasia and atrophy, and macular scarring with focal pigmentary retinal mottling.

A comprehensive neurological exam also is part of the recommendation. Seizures are sometimes part of Zika syndrome, but infants can also have subclinical EEG abnormalities. Advanced neuroimaging can identify both obvious and subtle brain abnormalities: cortical thinning, corpus callosum abnormalities, calcifications at the white/gray matter junction, and ventricular enlargement are possible findings.

As infants grow, clinicians should be alert for signs of increased intracranial pressure that could signal postnatal hydrocephalus. Diaphragmatic paralysis also has been seen; this manifests by respiratory distress. Dysphagia that interferes with feeding can develop as well.

The complicated clinical picture calls for a team approach, Dr. Adebanjo said. “The follow-up care of [these infants] requires a multidisciplinary team and an established medical home to facilitate the coordination of care and ensure that abnormal findings are addressed.”

Infants without clinical findings, whose mothers have lab-confirmed Zika exposure

Initially, these infants should have the same early head ultrasound, hearing, and eye exams as those who display clinical findings. All of these infants also should be tested for Zika virus in the same way as those with clinical findings.

If tests return a positive result, they should have all the investigations and follow-ups recommended for babies with clinical findings. If lab testing is negative, and clinical findings are normal, Zika infection is highly unlikely and they can receive routine care, although clinicians and parents should be on the lookout for any new symptoms that might suggest postnatal Zika syndrome.

Infants without clinical findings, whose mothers had possible, but unconfirmed, Zika exposure

This is a varied and large group, which includes women who were never tested during pregnancy, as well as those who could have had a false negative test. “Because the latter issue is not easily discerned, all mothers with possible exposure to Zika virus infection, including those who tested negative with currently available technology, should be considered in this group,” Dr. Adebanjo said.

CDC does not recommend further Zika evaluation for these infants unless additional testing confirms maternal infection. For older infants, parents and clinicians should decide together whether any further evaluations would be helpful. But, Dr. Adebanjo said, “If findings consistent with congenital Zika syndrome are identified at any time, referrals to appropriate specialties should be made, and subsequent evaluation should follow recommendations for infants with clinical findings consistent with congenital Zika.”

CDC also reiterated its special recommendations for infants who had a prenatal diagnosis of Zika infection. For now, these remain unchanged from 2016, although “as more data become available, understanding of the diagnostic role of prenatal ultrasound and amniocentesis will improve and guidance will be updated.”

No one has yet identified the optimal timing for a Zika diagnostic ultrasound. CDC recommends serial ultrasounds be done every 3-4 weeks for women with lab-confirmed prenatal Zika exposure. Women with possible exposure need only routine ultrasound screenings.

While Zika RNA has been identified in amniotic fluid, there is no consensus on the value of amniocentesis as a prenatal diagnostic tool. Investigations of serial amniocentesis suggests that viral shedding into the amniotic fluid might be transient. If the procedure is done for other reasons, Zika nucleic acid testing can be incorporated.

A shared decision-making process is key when making screening decisions that should be individually weighed, Dr. Adebanjo said. “For example, serial ultrasounds might be inconvenient, unpleasant, and expensive, and might prompt unnecessary interventions; amniocentesis carries additional known risks such as fetal loss. These potential harms of prenatal screening for congenital Zika syndrome might outweigh the clinical benefits for some patients. Therefore, these decisions should be individualized.”

Neither Dr. Adebanjo nor any of the coauthors had any financial disclosures.

FROM MMWR

VIDEO: Salvageable brain tissue can guide decision for stroke thrombectomy

SAN DIEGO – Neurologists have long suspected that some stroke patients could benefit from thrombectomy many hours after they were last seen well. But lingering doubts remained, and physicians weren’t sure which stroke patients were likely to improve.

Now, with the early stoppage of two key clinical trials, the answer is clear, Jeffrey Saver, MD, director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

At the European Stroke Organization Conference in May, Stryker Neurovascular announced the results of its DAWN trial, which tested the company’s mechanical thrombectomy device in patients who’d suffered a stroke within the past 6-24 hours and in whom imaging showed a clinical core mismatch. It was stopped early based on an interim analysis after it met multiple prespecified stopping criteria. At 90 days, 48.6% of patients in the treatment group were functionally independent, compared with 13.1% who received only medical management.

The DEFUSE 3 trial examined endovascular thrombectomy in patients 6-16 hours after a stroke who appeared to have salvageable brain tissue based on target mismatch profile with a less extreme core than in DAWN. It too was halted early because of a high probability of efficacy. Together, the trials suggest neurologists are entering a new era of treating based on tissue and not just time, Dr. Saver said.

SAN DIEGO – Neurologists have long suspected that some stroke patients could benefit from thrombectomy many hours after they were last seen well. But lingering doubts remained, and physicians weren’t sure which stroke patients were likely to improve.

Now, with the early stoppage of two key clinical trials, the answer is clear, Jeffrey Saver, MD, director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

At the European Stroke Organization Conference in May, Stryker Neurovascular announced the results of its DAWN trial, which tested the company’s mechanical thrombectomy device in patients who’d suffered a stroke within the past 6-24 hours and in whom imaging showed a clinical core mismatch. It was stopped early based on an interim analysis after it met multiple prespecified stopping criteria. At 90 days, 48.6% of patients in the treatment group were functionally independent, compared with 13.1% who received only medical management.

The DEFUSE 3 trial examined endovascular thrombectomy in patients 6-16 hours after a stroke who appeared to have salvageable brain tissue based on target mismatch profile with a less extreme core than in DAWN. It too was halted early because of a high probability of efficacy. Together, the trials suggest neurologists are entering a new era of treating based on tissue and not just time, Dr. Saver said.

SAN DIEGO – Neurologists have long suspected that some stroke patients could benefit from thrombectomy many hours after they were last seen well. But lingering doubts remained, and physicians weren’t sure which stroke patients were likely to improve.

Now, with the early stoppage of two key clinical trials, the answer is clear, Jeffrey Saver, MD, director of the stroke unit at the University of California, Los Angeles, said in a video interview at the annual meeting of the American Neurological Association.

At the European Stroke Organization Conference in May, Stryker Neurovascular announced the results of its DAWN trial, which tested the company’s mechanical thrombectomy device in patients who’d suffered a stroke within the past 6-24 hours and in whom imaging showed a clinical core mismatch. It was stopped early based on an interim analysis after it met multiple prespecified stopping criteria. At 90 days, 48.6% of patients in the treatment group were functionally independent, compared with 13.1% who received only medical management.

The DEFUSE 3 trial examined endovascular thrombectomy in patients 6-16 hours after a stroke who appeared to have salvageable brain tissue based on target mismatch profile with a less extreme core than in DAWN. It too was halted early because of a high probability of efficacy. Together, the trials suggest neurologists are entering a new era of treating based on tissue and not just time, Dr. Saver said.

AT ANA 2017

Burnout takes its toll on neurology

I’m burned out.

Heck, what doctor isn’t? Politicians say we get paid too much. Lawyers say we make too many mistakes. Insurance companies say we order too many tests and too many expensive treatments. And the patients, while generally good people looking for help, can also on occasion be angry and unreasonable. The bad apples may be in the minority, but it only takes one to ruin a day full of rewarding visits.

That can’t be good.

Some of the study’s listed reasons for burnout are very familiar: complaints about maintenance of certification and about calling insurances to authorize tests and medications, crappy reimbursement for time-consuming visits, having to spend more time at work just to break even, and the constant feeling of never being caught up. I leave work, come home, have dinner with my family, do dictations, go to bed, and do it over again. No matter where I am, I’ve never left the office.

Other common complaints aren’t as much an issue for me. I don’t have, or want, an electronic health record that qualifies for meaningful use; I designed the one I have, and it works fine for me. I don’t have a nonmedical administrator telling me how many patients I’m required to see each day, and my patient population is, overall, appreciative and polite.