User login

Experts offer guidance on GLP-1 receptor agonists prior to endoscopy

to support the success of endoscopic procedures, according to a new Clinical Practice Update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) has been associated with delayed gastric emptying, which raises a clinical concern about performing endoscopic procedures, especially upper endoscopies in patients using these medications, wrote Jana G. Al Hashash, MD, MSc, of the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues.

The Clinical Practice Update (CPU), published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, reviews the evidence and provides expert advice for clinicians on the evolving landscape of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists prior to endoscopic procedures. The CPU reflects on the most recent literature and the experience of the authors, all experts in bariatric medicine and/or endoscopy.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) issued guidance that reflects concerns for the risk of aspiration in sedated patients because of delayed gastric motility from the use of GLP-1 RAs. The ASA advises patients on daily doses of GLP-1 RAs to refrain from taking the medications on the day of a procedure; those on weekly dosing should hold the drugs for a week prior to surgery.

However, the ASA suggestions do not differentiate based on the indication for the drug or for the type of procedure, and questions remain as to whether these changes are necessary and/or effective, the CPU authors said. The ASA’s guidance is based mainly on expert opinion, as not enough published evidence on this topic exists for a robust review and formal guideline, they added.

Recently, a multisociety statement from the AGA, AASLD, ACG, ASGE, and NASPGHAN noted that widespread implementation of the ASA guidance could be associated with unintended harms to patients.

Therefore, the AGA CPU suggests an individualized approach to managing patients on GLP-1 RAs in a pre-endoscopic setting.

For patients on GLP-1 RAs for diabetes management, discontinuing prior to endoscopic may not be worth the potential risk. Also, consider not only the dose and frequency of the GLP-1 RAs but also other comorbidities, medications, and potential gastrointestinal side effects.

“If patients taking GLP-1 RAs solely for weight loss can be identified beforehand, a dose of the medication could be withheld prior to endoscopy with likely little harm, though this should not be considered mandatory or evidence-based,” the CPU authors wrote.

However, withholding a single dose of medication may not be enough for an individual’s gastric motility to return to normal, the authors emphasized.

Additionally, the ASA’s suggestions for holding GLP-1 RAs add complexity to periprocedural medication management, which may strain resources and delay care.

The AGA CPU offers the following guidance for patients on GLP-1 RAs prior to endoscopy:

In general, patients using GLP-1 RAs who have followed the standard perioperative procedures, usually an 8-hour solid-food fast and 2-hour liquid fast, and who do not have symptoms such as ongoing nausea, vomiting, or abdominal distension should proceed with upper and/or lower endoscopy.

For symptomatic patients who may experience negative clinical consequences of endoscopy if delayed, consider rapid-sequence intubation, but the authors acknowledge that this option may not be possible in most ambulatory or office-based endoscopy settings.

Finally, consider placing patients on a liquid diet the day before a sedated procedure instead of stopping GLP-1 RAs; this strategy is “more consistent with the holistic approach to preprocedural management of other similar condi-tions,” the authors said.

The current CPU endorses the multi-society statement that puts patient safety first and encourages AGA members to follow best practices when performing endoscopies on patients who are using GLP-1 RAs, in the absence of actionable data, the authors concluded.

The Clinical Practice Update received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Al Hashash had no financial conflicts to disclose.

to support the success of endoscopic procedures, according to a new Clinical Practice Update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) has been associated with delayed gastric emptying, which raises a clinical concern about performing endoscopic procedures, especially upper endoscopies in patients using these medications, wrote Jana G. Al Hashash, MD, MSc, of the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues.

The Clinical Practice Update (CPU), published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, reviews the evidence and provides expert advice for clinicians on the evolving landscape of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists prior to endoscopic procedures. The CPU reflects on the most recent literature and the experience of the authors, all experts in bariatric medicine and/or endoscopy.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) issued guidance that reflects concerns for the risk of aspiration in sedated patients because of delayed gastric motility from the use of GLP-1 RAs. The ASA advises patients on daily doses of GLP-1 RAs to refrain from taking the medications on the day of a procedure; those on weekly dosing should hold the drugs for a week prior to surgery.

However, the ASA suggestions do not differentiate based on the indication for the drug or for the type of procedure, and questions remain as to whether these changes are necessary and/or effective, the CPU authors said. The ASA’s guidance is based mainly on expert opinion, as not enough published evidence on this topic exists for a robust review and formal guideline, they added.

Recently, a multisociety statement from the AGA, AASLD, ACG, ASGE, and NASPGHAN noted that widespread implementation of the ASA guidance could be associated with unintended harms to patients.

Therefore, the AGA CPU suggests an individualized approach to managing patients on GLP-1 RAs in a pre-endoscopic setting.

For patients on GLP-1 RAs for diabetes management, discontinuing prior to endoscopic may not be worth the potential risk. Also, consider not only the dose and frequency of the GLP-1 RAs but also other comorbidities, medications, and potential gastrointestinal side effects.

“If patients taking GLP-1 RAs solely for weight loss can be identified beforehand, a dose of the medication could be withheld prior to endoscopy with likely little harm, though this should not be considered mandatory or evidence-based,” the CPU authors wrote.

However, withholding a single dose of medication may not be enough for an individual’s gastric motility to return to normal, the authors emphasized.

Additionally, the ASA’s suggestions for holding GLP-1 RAs add complexity to periprocedural medication management, which may strain resources and delay care.

The AGA CPU offers the following guidance for patients on GLP-1 RAs prior to endoscopy:

In general, patients using GLP-1 RAs who have followed the standard perioperative procedures, usually an 8-hour solid-food fast and 2-hour liquid fast, and who do not have symptoms such as ongoing nausea, vomiting, or abdominal distension should proceed with upper and/or lower endoscopy.

For symptomatic patients who may experience negative clinical consequences of endoscopy if delayed, consider rapid-sequence intubation, but the authors acknowledge that this option may not be possible in most ambulatory or office-based endoscopy settings.

Finally, consider placing patients on a liquid diet the day before a sedated procedure instead of stopping GLP-1 RAs; this strategy is “more consistent with the holistic approach to preprocedural management of other similar condi-tions,” the authors said.

The current CPU endorses the multi-society statement that puts patient safety first and encourages AGA members to follow best practices when performing endoscopies on patients who are using GLP-1 RAs, in the absence of actionable data, the authors concluded.

The Clinical Practice Update received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Al Hashash had no financial conflicts to disclose.

to support the success of endoscopic procedures, according to a new Clinical Practice Update from the American Gastroenterological Association.

Use of glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) has been associated with delayed gastric emptying, which raises a clinical concern about performing endoscopic procedures, especially upper endoscopies in patients using these medications, wrote Jana G. Al Hashash, MD, MSc, of the Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, Fla., and colleagues.

The Clinical Practice Update (CPU), published in Clinical Gastroenterology and Hepatology, reviews the evidence and provides expert advice for clinicians on the evolving landscape of patients taking GLP-1 receptor agonists prior to endoscopic procedures. The CPU reflects on the most recent literature and the experience of the authors, all experts in bariatric medicine and/or endoscopy.

The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) issued guidance that reflects concerns for the risk of aspiration in sedated patients because of delayed gastric motility from the use of GLP-1 RAs. The ASA advises patients on daily doses of GLP-1 RAs to refrain from taking the medications on the day of a procedure; those on weekly dosing should hold the drugs for a week prior to surgery.

However, the ASA suggestions do not differentiate based on the indication for the drug or for the type of procedure, and questions remain as to whether these changes are necessary and/or effective, the CPU authors said. The ASA’s guidance is based mainly on expert opinion, as not enough published evidence on this topic exists for a robust review and formal guideline, they added.

Recently, a multisociety statement from the AGA, AASLD, ACG, ASGE, and NASPGHAN noted that widespread implementation of the ASA guidance could be associated with unintended harms to patients.

Therefore, the AGA CPU suggests an individualized approach to managing patients on GLP-1 RAs in a pre-endoscopic setting.

For patients on GLP-1 RAs for diabetes management, discontinuing prior to endoscopic may not be worth the potential risk. Also, consider not only the dose and frequency of the GLP-1 RAs but also other comorbidities, medications, and potential gastrointestinal side effects.

“If patients taking GLP-1 RAs solely for weight loss can be identified beforehand, a dose of the medication could be withheld prior to endoscopy with likely little harm, though this should not be considered mandatory or evidence-based,” the CPU authors wrote.

However, withholding a single dose of medication may not be enough for an individual’s gastric motility to return to normal, the authors emphasized.

Additionally, the ASA’s suggestions for holding GLP-1 RAs add complexity to periprocedural medication management, which may strain resources and delay care.

The AGA CPU offers the following guidance for patients on GLP-1 RAs prior to endoscopy:

In general, patients using GLP-1 RAs who have followed the standard perioperative procedures, usually an 8-hour solid-food fast and 2-hour liquid fast, and who do not have symptoms such as ongoing nausea, vomiting, or abdominal distension should proceed with upper and/or lower endoscopy.

For symptomatic patients who may experience negative clinical consequences of endoscopy if delayed, consider rapid-sequence intubation, but the authors acknowledge that this option may not be possible in most ambulatory or office-based endoscopy settings.

Finally, consider placing patients on a liquid diet the day before a sedated procedure instead of stopping GLP-1 RAs; this strategy is “more consistent with the holistic approach to preprocedural management of other similar condi-tions,” the authors said.

The current CPU endorses the multi-society statement that puts patient safety first and encourages AGA members to follow best practices when performing endoscopies on patients who are using GLP-1 RAs, in the absence of actionable data, the authors concluded.

The Clinical Practice Update received no outside funding. Lead author Dr. Al Hashash had no financial conflicts to disclose.

CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY AND HEPATOLOGY

Studies address primary care oral health screening and prevention for children

Both were published online in JAMA.

In one report, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes that there is not enough evidence to assess harms versus benefits of routine screening or interventions for oral health conditions, including dental caries, in primary care for asymptomatic children and adolescents aged 5-17 years.

The evidence report on administering fluoride supplements, fluoride gels, sealants and varnish finds evidence that they improve outcomes. The report was done to inform the USPSTF for a new recommendation on primary care screening, dental referral, behavioral counseling, and preventive interventions for oral health in children and adolescents aged 5-17.

Primary care physicians’ role

One problem the USPSTF identified in its report was limited evidence on available clinical screening tools or assessments to identify which children have oral health conditions in the primary care setting.

The USPSTF’s team, led by Michael J. Barry, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, calls for more research to fill in the gaps before it can reassess.

Michael S. Reddy, DMD, DMSc, with University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry, Oral Health Affairs, said in an accompanying editorial that the current lack of data should not keep primary care physicians from considering oral health during routine medical exams or keep dentists from finding ways to collaborate with primary care physicians. “Medical primary care must partner with dentistry,” they wrote.

Until there is enough evidence for a USPSTF reevaluation on the topic, primary care clinicians should ask patients about their oral hygiene routines, whether they have any dental symptoms, and when they last saw a dentist, as well as referring to a dentist as necessary, the editorialists wrote.

That works both ways, the editorialists added. “Equally important, oral health professionals are encouraged to collaborate and be a resource for their primary care colleagues. Prevention is one of the best tools clinicians have, and it is promoted by integrated, whole-person health effort, “ wrote Dr. Reddy and colleagues.

When oral health stays separate from medical care, patients are left vulnerable, and referrals between medical and dental offices should be a stronger two-way system, the editorialists said.

“[N]ot every primary care patient has access to a dentist,” they wrote. “Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health. Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Evidence that gels, varnish, sealants are effective

In a companion paper, done to inform the USPSTF, Roger Chou, MD, with Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, and colleagues found that when administered by a dental professional or in school settings, fluoride supplements, gels and varnish, and resin-based sealants improved health outcomes.

The findings were based on three systematic reviews (20,684 participants) and 19 randomized clinical trials; three nonrandomized trials; and one observational study (total 15,026 participants.)

With fluoride versus placebo or no intervention, researchers found a decrease from baseline in the number of decayed, missing, or filled permanent teeth (DMFT index) or decayed or filled permanent teeth (DFT index). The average difference was −0.73 [95% confidence interval [CI], −1.30 to −0.19]) at 1.5 to 3 years (six trials; n = 1,395).

Fluoride gels were associated with a DMFT- or DFT-prevented fraction of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.09-0.27) at outcomes closest to 3 years (four trials; n = 1,525).

Researchers found an association between fluoride varnish and a DMFT- or DFT-prevented fraction of 0.44 (95% CI, 0.11-0.76) at 1 to 4.5 years (five trials; n = 3,902). The sealants tested were associated with decreased risk of caries in first molars (odds ratio, 0.21 [95% CI, 0.16-0.28]) at 48-54 months (four trials; n = 440).

They noted that the feasibility of administering preventive measures in primary care is unknown; the effectiveness shown here was based on administration in dental and supervised school settings.

Barriers in primary care settings may include lack of training and equipment (particularly for sealants), uncertain reimbursement and lack of acceptance and uptake.

USPSTF working to close evidence gaps

Wanda Nicholson, MD, MPH, Prevention and Community Health, George Washington Milken Institute of Public Health in Washington, wrote in an accompanying editorial that to speed necessary research to facilitate recommendations, “the USPSTF and its stakeholders need a transparent, easily implementable communication tool that will systematically describe the research necessary to be directly responsive to the evidence gaps.”

The editorialists noted that the USPSTF in trying to update recommendations often has few, if any, high-quality additional studies to consider since its previous recommendation.

To address that, meetings were conducted in November of 2022 involving USPSTF members, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) staff, and leadership from the Office of Disease Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Members formed a working group “to develop a standardized template for communicating research gaps” according to a framework developed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Dr. Nicholson and colleagues wrote, “classifying evidence gaps and calling for specific research needs is a prudent, collaborative step in addressing missing evidence,” particularly for underserved populations.

The authors and editorialists declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

Both were published online in JAMA.

In one report, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes that there is not enough evidence to assess harms versus benefits of routine screening or interventions for oral health conditions, including dental caries, in primary care for asymptomatic children and adolescents aged 5-17 years.

The evidence report on administering fluoride supplements, fluoride gels, sealants and varnish finds evidence that they improve outcomes. The report was done to inform the USPSTF for a new recommendation on primary care screening, dental referral, behavioral counseling, and preventive interventions for oral health in children and adolescents aged 5-17.

Primary care physicians’ role

One problem the USPSTF identified in its report was limited evidence on available clinical screening tools or assessments to identify which children have oral health conditions in the primary care setting.

The USPSTF’s team, led by Michael J. Barry, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, calls for more research to fill in the gaps before it can reassess.

Michael S. Reddy, DMD, DMSc, with University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry, Oral Health Affairs, said in an accompanying editorial that the current lack of data should not keep primary care physicians from considering oral health during routine medical exams or keep dentists from finding ways to collaborate with primary care physicians. “Medical primary care must partner with dentistry,” they wrote.

Until there is enough evidence for a USPSTF reevaluation on the topic, primary care clinicians should ask patients about their oral hygiene routines, whether they have any dental symptoms, and when they last saw a dentist, as well as referring to a dentist as necessary, the editorialists wrote.

That works both ways, the editorialists added. “Equally important, oral health professionals are encouraged to collaborate and be a resource for their primary care colleagues. Prevention is one of the best tools clinicians have, and it is promoted by integrated, whole-person health effort, “ wrote Dr. Reddy and colleagues.

When oral health stays separate from medical care, patients are left vulnerable, and referrals between medical and dental offices should be a stronger two-way system, the editorialists said.

“[N]ot every primary care patient has access to a dentist,” they wrote. “Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health. Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Evidence that gels, varnish, sealants are effective

In a companion paper, done to inform the USPSTF, Roger Chou, MD, with Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, and colleagues found that when administered by a dental professional or in school settings, fluoride supplements, gels and varnish, and resin-based sealants improved health outcomes.

The findings were based on three systematic reviews (20,684 participants) and 19 randomized clinical trials; three nonrandomized trials; and one observational study (total 15,026 participants.)

With fluoride versus placebo or no intervention, researchers found a decrease from baseline in the number of decayed, missing, or filled permanent teeth (DMFT index) or decayed or filled permanent teeth (DFT index). The average difference was −0.73 [95% confidence interval [CI], −1.30 to −0.19]) at 1.5 to 3 years (six trials; n = 1,395).

Fluoride gels were associated with a DMFT- or DFT-prevented fraction of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.09-0.27) at outcomes closest to 3 years (four trials; n = 1,525).

Researchers found an association between fluoride varnish and a DMFT- or DFT-prevented fraction of 0.44 (95% CI, 0.11-0.76) at 1 to 4.5 years (five trials; n = 3,902). The sealants tested were associated with decreased risk of caries in first molars (odds ratio, 0.21 [95% CI, 0.16-0.28]) at 48-54 months (four trials; n = 440).

They noted that the feasibility of administering preventive measures in primary care is unknown; the effectiveness shown here was based on administration in dental and supervised school settings.

Barriers in primary care settings may include lack of training and equipment (particularly for sealants), uncertain reimbursement and lack of acceptance and uptake.

USPSTF working to close evidence gaps

Wanda Nicholson, MD, MPH, Prevention and Community Health, George Washington Milken Institute of Public Health in Washington, wrote in an accompanying editorial that to speed necessary research to facilitate recommendations, “the USPSTF and its stakeholders need a transparent, easily implementable communication tool that will systematically describe the research necessary to be directly responsive to the evidence gaps.”

The editorialists noted that the USPSTF in trying to update recommendations often has few, if any, high-quality additional studies to consider since its previous recommendation.

To address that, meetings were conducted in November of 2022 involving USPSTF members, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) staff, and leadership from the Office of Disease Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Members formed a working group “to develop a standardized template for communicating research gaps” according to a framework developed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Dr. Nicholson and colleagues wrote, “classifying evidence gaps and calling for specific research needs is a prudent, collaborative step in addressing missing evidence,” particularly for underserved populations.

The authors and editorialists declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

Both were published online in JAMA.

In one report, the United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) concludes that there is not enough evidence to assess harms versus benefits of routine screening or interventions for oral health conditions, including dental caries, in primary care for asymptomatic children and adolescents aged 5-17 years.

The evidence report on administering fluoride supplements, fluoride gels, sealants and varnish finds evidence that they improve outcomes. The report was done to inform the USPSTF for a new recommendation on primary care screening, dental referral, behavioral counseling, and preventive interventions for oral health in children and adolescents aged 5-17.

Primary care physicians’ role

One problem the USPSTF identified in its report was limited evidence on available clinical screening tools or assessments to identify which children have oral health conditions in the primary care setting.

The USPSTF’s team, led by Michael J. Barry, MD, of Harvard Medical School in Boston, calls for more research to fill in the gaps before it can reassess.

Michael S. Reddy, DMD, DMSc, with University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry, Oral Health Affairs, said in an accompanying editorial that the current lack of data should not keep primary care physicians from considering oral health during routine medical exams or keep dentists from finding ways to collaborate with primary care physicians. “Medical primary care must partner with dentistry,” they wrote.

Until there is enough evidence for a USPSTF reevaluation on the topic, primary care clinicians should ask patients about their oral hygiene routines, whether they have any dental symptoms, and when they last saw a dentist, as well as referring to a dentist as necessary, the editorialists wrote.

That works both ways, the editorialists added. “Equally important, oral health professionals are encouraged to collaborate and be a resource for their primary care colleagues. Prevention is one of the best tools clinicians have, and it is promoted by integrated, whole-person health effort, “ wrote Dr. Reddy and colleagues.

When oral health stays separate from medical care, patients are left vulnerable, and referrals between medical and dental offices should be a stronger two-way system, the editorialists said.

“[N]ot every primary care patient has access to a dentist,” they wrote. “Oral health screening and referral by medical primary care clinicians can help ensure that individuals get to the dental chair to receive needed interventions that can benefit both oral and potentially overall health. Likewise, medical challenges and oral mucosal manifestations of chronic health conditions detected at a dental visit should result in medical referral, allowing prompt evaluation and treatment.”

Evidence that gels, varnish, sealants are effective

In a companion paper, done to inform the USPSTF, Roger Chou, MD, with Pacific Northwest Evidence-based Practice Center, Department of Medical Informatics and Clinical Epidemiology at Oregon Health & Science University in Portland, and colleagues found that when administered by a dental professional or in school settings, fluoride supplements, gels and varnish, and resin-based sealants improved health outcomes.

The findings were based on three systematic reviews (20,684 participants) and 19 randomized clinical trials; three nonrandomized trials; and one observational study (total 15,026 participants.)

With fluoride versus placebo or no intervention, researchers found a decrease from baseline in the number of decayed, missing, or filled permanent teeth (DMFT index) or decayed or filled permanent teeth (DFT index). The average difference was −0.73 [95% confidence interval [CI], −1.30 to −0.19]) at 1.5 to 3 years (six trials; n = 1,395).

Fluoride gels were associated with a DMFT- or DFT-prevented fraction of 0.18 (95% CI, 0.09-0.27) at outcomes closest to 3 years (four trials; n = 1,525).

Researchers found an association between fluoride varnish and a DMFT- or DFT-prevented fraction of 0.44 (95% CI, 0.11-0.76) at 1 to 4.5 years (five trials; n = 3,902). The sealants tested were associated with decreased risk of caries in first molars (odds ratio, 0.21 [95% CI, 0.16-0.28]) at 48-54 months (four trials; n = 440).

They noted that the feasibility of administering preventive measures in primary care is unknown; the effectiveness shown here was based on administration in dental and supervised school settings.

Barriers in primary care settings may include lack of training and equipment (particularly for sealants), uncertain reimbursement and lack of acceptance and uptake.

USPSTF working to close evidence gaps

Wanda Nicholson, MD, MPH, Prevention and Community Health, George Washington Milken Institute of Public Health in Washington, wrote in an accompanying editorial that to speed necessary research to facilitate recommendations, “the USPSTF and its stakeholders need a transparent, easily implementable communication tool that will systematically describe the research necessary to be directly responsive to the evidence gaps.”

The editorialists noted that the USPSTF in trying to update recommendations often has few, if any, high-quality additional studies to consider since its previous recommendation.

To address that, meetings were conducted in November of 2022 involving USPSTF members, Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) staff, and leadership from the Office of Disease Prevention and the National Institutes of Health. Members formed a working group “to develop a standardized template for communicating research gaps” according to a framework developed by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine.

Dr. Nicholson and colleagues wrote, “classifying evidence gaps and calling for specific research needs is a prudent, collaborative step in addressing missing evidence,” particularly for underserved populations.

The authors and editorialists declared no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA

Suicide prevention and the pediatrician

Suicide is among the top three causes of death for young people in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of suicide deaths has climbed from 4.4 per 100,000 American 12- to 17-year-olds in 2011 to 6.5 per 100,000 in 2021, an increase of almost 50%. As with accidents and homicides, we hope these are preventable deaths, although the factors contributing to them are complex.

We do know that

Suicide screening

In 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that all adolescents get screened for suicide risk annually. Given that less than 1 in 10,000 adolescents commit suicide and that there is no definitive data on how to prevent suicide in any individual, the goal of suicide screening is much broader than preventing suicide. Beyond universal screening, we will review how being open and curious with all of your patients can be the most extraordinary screening instrument.

There is extensive data that tells us that far from causing suicide, asking about suicidal thoughts is protective. When you make suicidal thoughts discussable, you directly counteract the isolation, stigma, and shame that are strong predictors of actual suicide attempts. You model the value of bringing difficult or frightening thoughts to the attention of caring adults, and you model calm listening rather than emotional overreaction for their parents. The resulting connectedness can lower the risk for vulnerable patients and enhance resilience for all of your patients.

Who is at greater risk?

We have robust data to guide our understanding of which youth have suicidal ideation, which is distinct from those who attempt suicide, which also may be quite distinct from those who complete. The CDC reports that the rate of suicidal thoughts (“seriously considering suicide”) in high school students climbed from 16% in 2011 to 22% in 2021. In that decade, the number of high schoolers with a suicide plan climbed from 13% to 18%, and those with suicide attempts climbed from 8% to 10%. Girls are at higher risk for suicidal thoughts and attempts, but boys are at greater risk for suicide completion. Black youth were more likely to attempt suicide than were their Asian, Hispanic, or White peers and LGBTQ+ youth are at particular risk; in 2021, they were three times as likely as were their heterosexual peers to have suicidal thoughts and attempts. Youth with psychiatric illness (particularly PTSD, mood or thought disorders), a family history of suicide, a history of risk-taking behavior (including sexual activity, smoking, drinking, and drug use) and those with prior suicide attempts are at the highest risk for suicide. Adding all these risk factors together means that many, if not the majority, of teenagers have risk factors.

Focus on the patient

In your office, though, a public health approach should give way to curiosity about your individual patient. Suicidal thoughts usually follow a substantial stress. Pay attention to exceptional stresses, especially if they have a component of social stigma or isolation. Did your patient report another student for an assault? Are they now being bullied or ostracized by friends? Have they lost an especially important relationship? Some other stresses may seem minor, such as a poor grade on a test. But for a very driven, perfectionistic teenager who believes that a perfect 4.0 GPA is essential to college admission and future success and happiness, one poor grade may feel like a catastrophe.

When your patients tell you about a challenge or setback, slow down and be curious. Listen to the importance they give it. How have they managed it? Are they finding it hard to go to school or back to practice? Do they feel discouraged or even hopeless? Discouragement is a normal response to adversity, but it should be temporary. This approach can make it easy to ask if they have ever wished they were dead, or made a suicide plan or an attempt. When you calmly and supportively learn about their inner experience, it will be easy for young people to be honest with you.

There will be teenagers in your practice who are sensation-seeking and impulsive, and you should pay special attention to this group. They may not be classically depressed, but in the aftermath of a stressful experience that they find humiliating or shameful, they are at risk for an impulsive act that could still be lethal. Be curious with these patients after they feel they have let down their team or their family, or if they have been caught in a crime or cheating, or even if their girlfriend breaks up with them. Find out how they are managing, and where their support comes from. Ask them in a nonjudgmental manner about whether they are having thoughts about death or suicide, and if those thoughts are troubling, frequent, or feel like a relief. What has stopped them from acting on these thoughts? Offer your patient the perspective that such thoughts may be normal in the face of a large stress, but that the pain of stress always subsides, whereas suicide is irreversible.

There will also be patients in your practice who cut themselves. This is sometimes called “nonsuicidal self-injury,” and it often raises concern about suicide risk. While accelerating frequency of self-injury in a teenager who is suicidal can indicate growing risk, this behavior alone is usually a mechanism for regulating emotion. Ask your patient about when they cut themselves. What are the triggers? How do they feel afterward? Are their friends all doing it? Is it only after fighting with their parents? Or does it make their parents worry instead of getting angry? As you learn about the nature of the behavior, you will be able to offer thoughtful guidance about better strategies for stress management or to pursue further assessment and support.

Next steps

Speaking comfortably with your patients about suicidal thoughts and behaviors requires that you also feel comfortable with what comes next. As in the ASQ screening instrument recommended by the AAP, you should always follow affirmative answers about suicidal thoughts with more questions. Do they have a plan? Do they have access to lethal means including any guns in the home? Have they ever made an attempt? Are they thinking about killing themselves now? If the thoughts are current, they have access, and they have tried before, it is clear that they need an urgent assessment, probably in an emergency department. But when the thoughts were in the past or have never been connected to plans or intent, there is an opportunity to enhance their connectedness. You can diminish the potential for shame, stigma and isolation by reminding them that such thoughts and feelings are normal in the face of difficulty. They deserve support to help them face and manage their adversity, whether that stress comes from an internal or external source. How do they feel now that they have shared these thoughts with you? Most will describe feeling better, relieved, even hopeful once they are not facing intense thoughts and feelings alone.

You should tell them that you would like to bring their parents into the conversation. You want them to know they can turn to their parents if they are having these thoughts, so they are never alone in facing them. Parents can learn from your model of calm and supportive listening to fully understand the situation before turning together to talk about what might be helpful next steps. It is always prudent to create “speed bumps” between thought and action with impulsive teens, so recommend limiting access to any lethal means (firearms especially). But the strongest protective intervention is for the child to feel confident in and connected to their support network, trusting you and their parents to listen and understand before figuring out together what else is needed to address the situation.

Lastly, recognize that talking about difficult issues with teenagers is among the most stressful and demanding aspects of pediatric primary care. Talk to colleagues, never worry alone, and recognize and manage your own stress. This is among the best ways to model for your patients and their parents that every challenge can be met, but we often need support.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Suicide is among the top three causes of death for young people in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of suicide deaths has climbed from 4.4 per 100,000 American 12- to 17-year-olds in 2011 to 6.5 per 100,000 in 2021, an increase of almost 50%. As with accidents and homicides, we hope these are preventable deaths, although the factors contributing to them are complex.

We do know that

Suicide screening

In 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that all adolescents get screened for suicide risk annually. Given that less than 1 in 10,000 adolescents commit suicide and that there is no definitive data on how to prevent suicide in any individual, the goal of suicide screening is much broader than preventing suicide. Beyond universal screening, we will review how being open and curious with all of your patients can be the most extraordinary screening instrument.

There is extensive data that tells us that far from causing suicide, asking about suicidal thoughts is protective. When you make suicidal thoughts discussable, you directly counteract the isolation, stigma, and shame that are strong predictors of actual suicide attempts. You model the value of bringing difficult or frightening thoughts to the attention of caring adults, and you model calm listening rather than emotional overreaction for their parents. The resulting connectedness can lower the risk for vulnerable patients and enhance resilience for all of your patients.

Who is at greater risk?

We have robust data to guide our understanding of which youth have suicidal ideation, which is distinct from those who attempt suicide, which also may be quite distinct from those who complete. The CDC reports that the rate of suicidal thoughts (“seriously considering suicide”) in high school students climbed from 16% in 2011 to 22% in 2021. In that decade, the number of high schoolers with a suicide plan climbed from 13% to 18%, and those with suicide attempts climbed from 8% to 10%. Girls are at higher risk for suicidal thoughts and attempts, but boys are at greater risk for suicide completion. Black youth were more likely to attempt suicide than were their Asian, Hispanic, or White peers and LGBTQ+ youth are at particular risk; in 2021, they were three times as likely as were their heterosexual peers to have suicidal thoughts and attempts. Youth with psychiatric illness (particularly PTSD, mood or thought disorders), a family history of suicide, a history of risk-taking behavior (including sexual activity, smoking, drinking, and drug use) and those with prior suicide attempts are at the highest risk for suicide. Adding all these risk factors together means that many, if not the majority, of teenagers have risk factors.

Focus on the patient

In your office, though, a public health approach should give way to curiosity about your individual patient. Suicidal thoughts usually follow a substantial stress. Pay attention to exceptional stresses, especially if they have a component of social stigma or isolation. Did your patient report another student for an assault? Are they now being bullied or ostracized by friends? Have they lost an especially important relationship? Some other stresses may seem minor, such as a poor grade on a test. But for a very driven, perfectionistic teenager who believes that a perfect 4.0 GPA is essential to college admission and future success and happiness, one poor grade may feel like a catastrophe.

When your patients tell you about a challenge or setback, slow down and be curious. Listen to the importance they give it. How have they managed it? Are they finding it hard to go to school or back to practice? Do they feel discouraged or even hopeless? Discouragement is a normal response to adversity, but it should be temporary. This approach can make it easy to ask if they have ever wished they were dead, or made a suicide plan or an attempt. When you calmly and supportively learn about their inner experience, it will be easy for young people to be honest with you.

There will be teenagers in your practice who are sensation-seeking and impulsive, and you should pay special attention to this group. They may not be classically depressed, but in the aftermath of a stressful experience that they find humiliating or shameful, they are at risk for an impulsive act that could still be lethal. Be curious with these patients after they feel they have let down their team or their family, or if they have been caught in a crime or cheating, or even if their girlfriend breaks up with them. Find out how they are managing, and where their support comes from. Ask them in a nonjudgmental manner about whether they are having thoughts about death or suicide, and if those thoughts are troubling, frequent, or feel like a relief. What has stopped them from acting on these thoughts? Offer your patient the perspective that such thoughts may be normal in the face of a large stress, but that the pain of stress always subsides, whereas suicide is irreversible.

There will also be patients in your practice who cut themselves. This is sometimes called “nonsuicidal self-injury,” and it often raises concern about suicide risk. While accelerating frequency of self-injury in a teenager who is suicidal can indicate growing risk, this behavior alone is usually a mechanism for regulating emotion. Ask your patient about when they cut themselves. What are the triggers? How do they feel afterward? Are their friends all doing it? Is it only after fighting with their parents? Or does it make their parents worry instead of getting angry? As you learn about the nature of the behavior, you will be able to offer thoughtful guidance about better strategies for stress management or to pursue further assessment and support.

Next steps

Speaking comfortably with your patients about suicidal thoughts and behaviors requires that you also feel comfortable with what comes next. As in the ASQ screening instrument recommended by the AAP, you should always follow affirmative answers about suicidal thoughts with more questions. Do they have a plan? Do they have access to lethal means including any guns in the home? Have they ever made an attempt? Are they thinking about killing themselves now? If the thoughts are current, they have access, and they have tried before, it is clear that they need an urgent assessment, probably in an emergency department. But when the thoughts were in the past or have never been connected to plans or intent, there is an opportunity to enhance their connectedness. You can diminish the potential for shame, stigma and isolation by reminding them that such thoughts and feelings are normal in the face of difficulty. They deserve support to help them face and manage their adversity, whether that stress comes from an internal or external source. How do they feel now that they have shared these thoughts with you? Most will describe feeling better, relieved, even hopeful once they are not facing intense thoughts and feelings alone.

You should tell them that you would like to bring their parents into the conversation. You want them to know they can turn to their parents if they are having these thoughts, so they are never alone in facing them. Parents can learn from your model of calm and supportive listening to fully understand the situation before turning together to talk about what might be helpful next steps. It is always prudent to create “speed bumps” between thought and action with impulsive teens, so recommend limiting access to any lethal means (firearms especially). But the strongest protective intervention is for the child to feel confident in and connected to their support network, trusting you and their parents to listen and understand before figuring out together what else is needed to address the situation.

Lastly, recognize that talking about difficult issues with teenagers is among the most stressful and demanding aspects of pediatric primary care. Talk to colleagues, never worry alone, and recognize and manage your own stress. This is among the best ways to model for your patients and their parents that every challenge can be met, but we often need support.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Suicide is among the top three causes of death for young people in the United States. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the rate of suicide deaths has climbed from 4.4 per 100,000 American 12- to 17-year-olds in 2011 to 6.5 per 100,000 in 2021, an increase of almost 50%. As with accidents and homicides, we hope these are preventable deaths, although the factors contributing to them are complex.

We do know that

Suicide screening

In 2022, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommended that all adolescents get screened for suicide risk annually. Given that less than 1 in 10,000 adolescents commit suicide and that there is no definitive data on how to prevent suicide in any individual, the goal of suicide screening is much broader than preventing suicide. Beyond universal screening, we will review how being open and curious with all of your patients can be the most extraordinary screening instrument.

There is extensive data that tells us that far from causing suicide, asking about suicidal thoughts is protective. When you make suicidal thoughts discussable, you directly counteract the isolation, stigma, and shame that are strong predictors of actual suicide attempts. You model the value of bringing difficult or frightening thoughts to the attention of caring adults, and you model calm listening rather than emotional overreaction for their parents. The resulting connectedness can lower the risk for vulnerable patients and enhance resilience for all of your patients.

Who is at greater risk?

We have robust data to guide our understanding of which youth have suicidal ideation, which is distinct from those who attempt suicide, which also may be quite distinct from those who complete. The CDC reports that the rate of suicidal thoughts (“seriously considering suicide”) in high school students climbed from 16% in 2011 to 22% in 2021. In that decade, the number of high schoolers with a suicide plan climbed from 13% to 18%, and those with suicide attempts climbed from 8% to 10%. Girls are at higher risk for suicidal thoughts and attempts, but boys are at greater risk for suicide completion. Black youth were more likely to attempt suicide than were their Asian, Hispanic, or White peers and LGBTQ+ youth are at particular risk; in 2021, they were three times as likely as were their heterosexual peers to have suicidal thoughts and attempts. Youth with psychiatric illness (particularly PTSD, mood or thought disorders), a family history of suicide, a history of risk-taking behavior (including sexual activity, smoking, drinking, and drug use) and those with prior suicide attempts are at the highest risk for suicide. Adding all these risk factors together means that many, if not the majority, of teenagers have risk factors.

Focus on the patient

In your office, though, a public health approach should give way to curiosity about your individual patient. Suicidal thoughts usually follow a substantial stress. Pay attention to exceptional stresses, especially if they have a component of social stigma or isolation. Did your patient report another student for an assault? Are they now being bullied or ostracized by friends? Have they lost an especially important relationship? Some other stresses may seem minor, such as a poor grade on a test. But for a very driven, perfectionistic teenager who believes that a perfect 4.0 GPA is essential to college admission and future success and happiness, one poor grade may feel like a catastrophe.

When your patients tell you about a challenge or setback, slow down and be curious. Listen to the importance they give it. How have they managed it? Are they finding it hard to go to school or back to practice? Do they feel discouraged or even hopeless? Discouragement is a normal response to adversity, but it should be temporary. This approach can make it easy to ask if they have ever wished they were dead, or made a suicide plan or an attempt. When you calmly and supportively learn about their inner experience, it will be easy for young people to be honest with you.

There will be teenagers in your practice who are sensation-seeking and impulsive, and you should pay special attention to this group. They may not be classically depressed, but in the aftermath of a stressful experience that they find humiliating or shameful, they are at risk for an impulsive act that could still be lethal. Be curious with these patients after they feel they have let down their team or their family, or if they have been caught in a crime or cheating, or even if their girlfriend breaks up with them. Find out how they are managing, and where their support comes from. Ask them in a nonjudgmental manner about whether they are having thoughts about death or suicide, and if those thoughts are troubling, frequent, or feel like a relief. What has stopped them from acting on these thoughts? Offer your patient the perspective that such thoughts may be normal in the face of a large stress, but that the pain of stress always subsides, whereas suicide is irreversible.

There will also be patients in your practice who cut themselves. This is sometimes called “nonsuicidal self-injury,” and it often raises concern about suicide risk. While accelerating frequency of self-injury in a teenager who is suicidal can indicate growing risk, this behavior alone is usually a mechanism for regulating emotion. Ask your patient about when they cut themselves. What are the triggers? How do they feel afterward? Are their friends all doing it? Is it only after fighting with their parents? Or does it make their parents worry instead of getting angry? As you learn about the nature of the behavior, you will be able to offer thoughtful guidance about better strategies for stress management or to pursue further assessment and support.

Next steps

Speaking comfortably with your patients about suicidal thoughts and behaviors requires that you also feel comfortable with what comes next. As in the ASQ screening instrument recommended by the AAP, you should always follow affirmative answers about suicidal thoughts with more questions. Do they have a plan? Do they have access to lethal means including any guns in the home? Have they ever made an attempt? Are they thinking about killing themselves now? If the thoughts are current, they have access, and they have tried before, it is clear that they need an urgent assessment, probably in an emergency department. But when the thoughts were in the past or have never been connected to plans or intent, there is an opportunity to enhance their connectedness. You can diminish the potential for shame, stigma and isolation by reminding them that such thoughts and feelings are normal in the face of difficulty. They deserve support to help them face and manage their adversity, whether that stress comes from an internal or external source. How do they feel now that they have shared these thoughts with you? Most will describe feeling better, relieved, even hopeful once they are not facing intense thoughts and feelings alone.

You should tell them that you would like to bring their parents into the conversation. You want them to know they can turn to their parents if they are having these thoughts, so they are never alone in facing them. Parents can learn from your model of calm and supportive listening to fully understand the situation before turning together to talk about what might be helpful next steps. It is always prudent to create “speed bumps” between thought and action with impulsive teens, so recommend limiting access to any lethal means (firearms especially). But the strongest protective intervention is for the child to feel confident in and connected to their support network, trusting you and their parents to listen and understand before figuring out together what else is needed to address the situation.

Lastly, recognize that talking about difficult issues with teenagers is among the most stressful and demanding aspects of pediatric primary care. Talk to colleagues, never worry alone, and recognize and manage your own stress. This is among the best ways to model for your patients and their parents that every challenge can be met, but we often need support.

Dr. Swick is physician in chief at Ohana, Center for Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health, Community Hospital of the Monterey (Calif.) Peninsula. Dr. Jellinek is professor emeritus of psychiatry and pediatrics, Harvard Medical School, Boston. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and high stroke risk in Black women

I’d like to talk with you about a recent report from the large-scale Black Women’s Health Study, published in the new journal NEJM Evidence.

This study looked at the association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, and the risk for stroke over the next 20 (median, 22) years. Previous studies have linked hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with an increased risk for stroke. However, most of these studies have been done in White women of European ancestry, and evidence in Black women has been very limited, despite a disproportionately high risk of having a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and also of stroke.

– overall, a 66% increased risk, an 80% increased risk with gestational hypertension, and about a 50% increased risk with preeclampsia.

We know that pregnancy itself can lead to some remodeling of the vascular system, but we don’t know whether a direct causal relationship exists between preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and subsequent stroke. Another potential explanation is that these complications of pregnancy serve as a window into a woman’s future cardiometabolic health and a marker of her cardiovascular risk.

Regardless, the clinical implications are the same. First, we would want to prevent these complications of pregnancy whenever possible. Some women will be candidates for the use of aspirin if they are at high risk for preeclampsia, and certainly for monitoring blood pressure very closely during pregnancy. It will also be important to maintain blood pressure control in the postpartum period and during the subsequent years of adulthood to minimize risk for stroke, because hypertension is such a powerful risk factor for stroke.

It will also be tremendously important to intensify lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity and having a heart-healthy diet. These complications of pregnancy have also been linked in other studies to an increased risk for subsequent coronary heart disease events and heart failure.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Manson is professor of medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and chief of the division of preventive medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and past president, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012. She disclosed receiving study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about a recent report from the large-scale Black Women’s Health Study, published in the new journal NEJM Evidence.

This study looked at the association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, and the risk for stroke over the next 20 (median, 22) years. Previous studies have linked hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with an increased risk for stroke. However, most of these studies have been done in White women of European ancestry, and evidence in Black women has been very limited, despite a disproportionately high risk of having a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and also of stroke.

– overall, a 66% increased risk, an 80% increased risk with gestational hypertension, and about a 50% increased risk with preeclampsia.

We know that pregnancy itself can lead to some remodeling of the vascular system, but we don’t know whether a direct causal relationship exists between preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and subsequent stroke. Another potential explanation is that these complications of pregnancy serve as a window into a woman’s future cardiometabolic health and a marker of her cardiovascular risk.

Regardless, the clinical implications are the same. First, we would want to prevent these complications of pregnancy whenever possible. Some women will be candidates for the use of aspirin if they are at high risk for preeclampsia, and certainly for monitoring blood pressure very closely during pregnancy. It will also be important to maintain blood pressure control in the postpartum period and during the subsequent years of adulthood to minimize risk for stroke, because hypertension is such a powerful risk factor for stroke.

It will also be tremendously important to intensify lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity and having a heart-healthy diet. These complications of pregnancy have also been linked in other studies to an increased risk for subsequent coronary heart disease events and heart failure.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Manson is professor of medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and chief of the division of preventive medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and past president, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012. She disclosed receiving study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

I’d like to talk with you about a recent report from the large-scale Black Women’s Health Study, published in the new journal NEJM Evidence.

This study looked at the association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, including preeclampsia and gestational hypertension, and the risk for stroke over the next 20 (median, 22) years. Previous studies have linked hypertensive disorders of pregnancy with an increased risk for stroke. However, most of these studies have been done in White women of European ancestry, and evidence in Black women has been very limited, despite a disproportionately high risk of having a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy and also of stroke.

– overall, a 66% increased risk, an 80% increased risk with gestational hypertension, and about a 50% increased risk with preeclampsia.

We know that pregnancy itself can lead to some remodeling of the vascular system, but we don’t know whether a direct causal relationship exists between preeclampsia or gestational hypertension and subsequent stroke. Another potential explanation is that these complications of pregnancy serve as a window into a woman’s future cardiometabolic health and a marker of her cardiovascular risk.

Regardless, the clinical implications are the same. First, we would want to prevent these complications of pregnancy whenever possible. Some women will be candidates for the use of aspirin if they are at high risk for preeclampsia, and certainly for monitoring blood pressure very closely during pregnancy. It will also be important to maintain blood pressure control in the postpartum period and during the subsequent years of adulthood to minimize risk for stroke, because hypertension is such a powerful risk factor for stroke.

It will also be tremendously important to intensify lifestyle modifications such as increasing physical activity and having a heart-healthy diet. These complications of pregnancy have also been linked in other studies to an increased risk for subsequent coronary heart disease events and heart failure.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Dr. Manson is professor of medicine and the Michael and Lee Bell Professor of Women’s Health, Harvard Medical School, and chief of the division of preventive medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, both in Boston, and past president, North American Menopause Society, 2011-2012. She disclosed receiving study pill donation and infrastructure support from Mars Symbioscience (for the COSMOS trial).

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Even one night in the ED raises risk for death

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

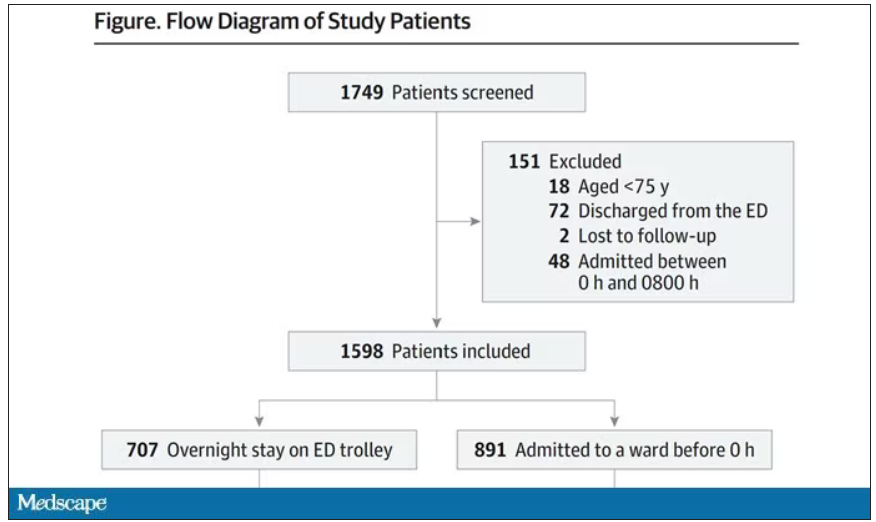

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

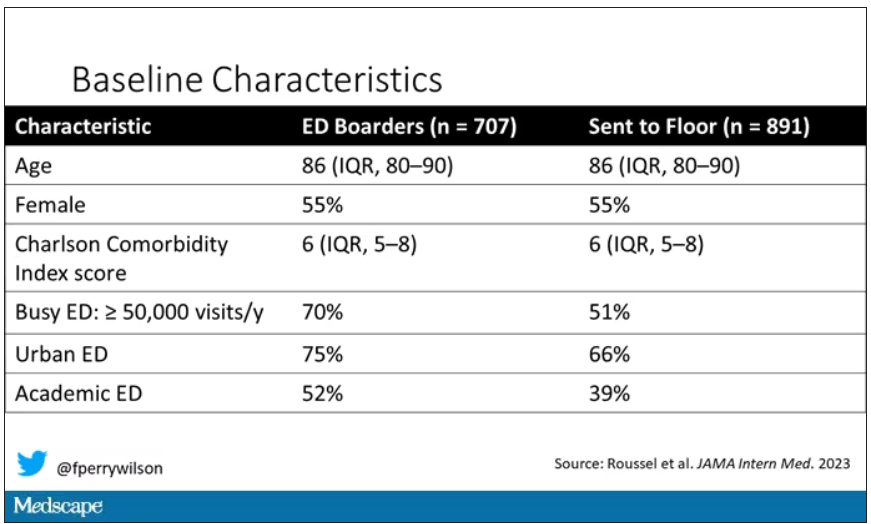

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial:

This difference held up even after adjustment for patient and hospital characteristics. Put another way, you’d need to send 22 patients to the floor instead of boarding in the ED to save one life. Not a bad return on investment.

It’s not entirely clear what the mechanism for the excess mortality might be, but the researchers note that patients kept in the ED overnight were about twice as likely to have a fall during their hospital stay – not surprising, given the dangers of gurneys in hallways and the sleep deprivation that trying to rest in a busy ED engenders.

I should point out that this could be worse in the United States. French ED doctors continue to care for admitted patients boarding in the ED, whereas in many hospitals in the United States, admitted patients are the responsibility of the floor team, regardless of where they are, making it more likely that these individuals may be neglected.

So, if boarding in the ED is a life-threatening situation, why do we do it? What conditions predispose to this?

You’ll hear a lot of talk, mostly from hospital administrators, saying that this is simply a problem of supply and demand. There are not enough beds for the number of patients who need beds. And staffing shortages don’t help either.

However, they never want to talk about the reasons for the staffing shortages, like poor pay, poor support, and, of course, the moral injury of treating patients in hallways.

The issue of volume is real. We could do a lot to prevent ED visits and hospital admissions by providing better access to preventive and primary care and improving our outpatient mental health infrastructure. But I think this framing passes the buck a little.

Another reason ED boarding occurs is the way our health care system is paid for. If you are building a hospital, you have little incentive to build in excess capacity. The most efficient hospital, from a profit-and-loss standpoint, is one that is 100% full as often as possible. That may be fine at times, but throw in a respiratory virus or even a pandemic, and those systems fracture under the pressure.

Let us also remember that not all hospital beds are given to patients who acutely need hospital beds. Many beds, in many hospitals, are necessary to handle postoperative patients undergoing elective procedures. Those patients having a knee replacement or abdominoplasty don’t spend the night in the ED when they leave the OR; they go to a hospital bed. And those procedures are – let’s face it – more profitable than an ED admission for a medical issue. That’s why, even when hospitals expand the number of beds they have, they do it with an eye toward increasing the rate of those profitable procedures, not decreasing the burden faced by their ED.

For now, the band-aid to the solution might be to better triage individuals boarding in the ED for floor access, prioritizing those of older age, greater frailty, or more medical complexity. But it feels like a stop-gap measure as long as the incentives are aligned to view an empty hospital bed as a sign of failure in the health system instead of success.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and public health and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He reported no conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

As a consulting nephrologist, I go all over the hospital. Medicine floors, surgical floors, the ICU – I’ve even done consults in the operating room. And more and more, I do consults in the emergency department.

The reason I am doing more consults in the ED is not because the ED docs are getting gun shy with creatinine increases; it’s because patients are staying for extended periods in the ED despite being formally admitted to the hospital. It’s a phenomenon known as boarding, because there are simply not enough beds. You know the scene if you have ever been to a busy hospital: The ED is full to breaking, with patients on stretchers in hallways. It can often feel more like a warzone than a place for healing.

This is a huge problem.

The Joint Commission specifies that admitted patients should spend no more than 4 hours in the ED waiting for a bed in the hospital.

That is, based on what I’ve seen, hugely ambitious. But I should point out that I work in a hospital that runs near capacity all the time, and studies – from some of my Yale colleagues, actually – have shown that once hospital capacity exceeds 85%, boarding rates skyrocket.

I want to discuss some of the causes of extended boarding and some solutions. But before that, I should prove to you that this really matters, and for that we are going to dig in to a new study which suggests that ED boarding kills.

To put some hard numbers to the boarding problem, we turn to this paper out of France, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

This is a unique study design. Basically, on a single day – Dec. 12, 2022 – researchers fanned out across France to 97 EDs and started counting patients. The study focused on those older than age 75 who were admitted to a hospital ward from the ED. The researchers then defined two groups: those who were sent up to the hospital floor before midnight, and those who spent at least from midnight until 8 AM in the ED (basically, people forced to sleep in the ED for a night). The middle-ground people who were sent up between midnight and 8 AM were excluded.

The baseline characteristics between the two groups of patients were pretty similar: median age around 86, 55% female. There were no significant differences in comorbidities. That said, comporting with previous studies, people in an urban ED, an academic ED, or a busy ED were much more likely to board overnight.

So, what we have are two similar groups of patients treated quite differently. Not quite a randomized trial, given the hospital differences, but not bad for purposes of analysis.

Here are the most important numbers from the trial: