User login

Glucose metabolism deemed key to platelet survival

New research published in Cell Reports suggests platelets are highly reliant on their ability to metabolize glucose.

Researchers studied mice lacking proteins that platelets use to import glucose—glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 and GLUT3.

These mice had lower platelet counts and their platelets had shorter life spans than platelets in wild-type mice.

“We found that glucose metabolism is very critical across the entire life cycle of platelets—from production, to what they do in the body, to how they get cleared from the body,” said E. Dale Abel, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

For this study, Dr Abel and his colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models that were missing GLUT1 and GLUT3 or GLUT3 alone and observed how platelet formation, function, and clearance were affected.

Mice missing glucose transporter proteins did produce platelets, and the platelets’ mitochondria metabolized other substances in place of glucose. However, the mice had platelet counts that were lower than normal.

The researchers were able to pinpoint 2 causes for the low platelet count in mice lacking GLUT1 and GLUT3—fewer platelets being produced and increased clearance of platelets.

The team tested megakaryocytes’ ability to generate new platelets by depleting the blood of platelets and observing the subsequent recovery, which was lower than normal.

They also tested the megakaryocytes in culture, stimulating them to create new platelets, and found the generation of new platelets was defective.

“Clearly, we show that there’s an obligate need for glucose to bud platelets off from the bone marrow,” Dr Abel said.

In addition, the team observed that young platelets functioned normally, even in the absence of glucose. But as they aged, the platelets were cleared from the circulation earlier than normal because they were being destroyed.

“We identified a new mechanism of necrosis by which the absence of glucose leads to the cleavage of a protein called calpain, which marks them for this necrotic pathway,” Dr Abel said. “If we treated the animals with a calpain inhibitor, we could reduce the increased platelet clearance.”

The team also sought to determine whether platelets could exist and function when mitochondria metabolism is halted.

They injected the mice with oligomycin, which inhibits mitochondrial metabolism. In the mice deficient in GLUT1 and GLUT3, platelet counts dropped to 0 within about 30 minutes. The same effect did not occur in wild-type mice.

“This work defined a very important role for metabolism in how platelets leave the bone marrow, how they come into circulation, and how they stay in circulation,” Dr Abel said. “It could even have implications for why platelets have to be used within a certain period of time when they’re donated at the blood bank—the fresher the better.” ![]()

New research published in Cell Reports suggests platelets are highly reliant on their ability to metabolize glucose.

Researchers studied mice lacking proteins that platelets use to import glucose—glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 and GLUT3.

These mice had lower platelet counts and their platelets had shorter life spans than platelets in wild-type mice.

“We found that glucose metabolism is very critical across the entire life cycle of platelets—from production, to what they do in the body, to how they get cleared from the body,” said E. Dale Abel, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

For this study, Dr Abel and his colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models that were missing GLUT1 and GLUT3 or GLUT3 alone and observed how platelet formation, function, and clearance were affected.

Mice missing glucose transporter proteins did produce platelets, and the platelets’ mitochondria metabolized other substances in place of glucose. However, the mice had platelet counts that were lower than normal.

The researchers were able to pinpoint 2 causes for the low platelet count in mice lacking GLUT1 and GLUT3—fewer platelets being produced and increased clearance of platelets.

The team tested megakaryocytes’ ability to generate new platelets by depleting the blood of platelets and observing the subsequent recovery, which was lower than normal.

They also tested the megakaryocytes in culture, stimulating them to create new platelets, and found the generation of new platelets was defective.

“Clearly, we show that there’s an obligate need for glucose to bud platelets off from the bone marrow,” Dr Abel said.

In addition, the team observed that young platelets functioned normally, even in the absence of glucose. But as they aged, the platelets were cleared from the circulation earlier than normal because they were being destroyed.

“We identified a new mechanism of necrosis by which the absence of glucose leads to the cleavage of a protein called calpain, which marks them for this necrotic pathway,” Dr Abel said. “If we treated the animals with a calpain inhibitor, we could reduce the increased platelet clearance.”

The team also sought to determine whether platelets could exist and function when mitochondria metabolism is halted.

They injected the mice with oligomycin, which inhibits mitochondrial metabolism. In the mice deficient in GLUT1 and GLUT3, platelet counts dropped to 0 within about 30 minutes. The same effect did not occur in wild-type mice.

“This work defined a very important role for metabolism in how platelets leave the bone marrow, how they come into circulation, and how they stay in circulation,” Dr Abel said. “It could even have implications for why platelets have to be used within a certain period of time when they’re donated at the blood bank—the fresher the better.” ![]()

New research published in Cell Reports suggests platelets are highly reliant on their ability to metabolize glucose.

Researchers studied mice lacking proteins that platelets use to import glucose—glucose transporter (GLUT) 1 and GLUT3.

These mice had lower platelet counts and their platelets had shorter life spans than platelets in wild-type mice.

“We found that glucose metabolism is very critical across the entire life cycle of platelets—from production, to what they do in the body, to how they get cleared from the body,” said E. Dale Abel, MBBS, PhD, of the University of Iowa in Iowa City.

For this study, Dr Abel and his colleagues studied genetically engineered mouse models that were missing GLUT1 and GLUT3 or GLUT3 alone and observed how platelet formation, function, and clearance were affected.

Mice missing glucose transporter proteins did produce platelets, and the platelets’ mitochondria metabolized other substances in place of glucose. However, the mice had platelet counts that were lower than normal.

The researchers were able to pinpoint 2 causes for the low platelet count in mice lacking GLUT1 and GLUT3—fewer platelets being produced and increased clearance of platelets.

The team tested megakaryocytes’ ability to generate new platelets by depleting the blood of platelets and observing the subsequent recovery, which was lower than normal.

They also tested the megakaryocytes in culture, stimulating them to create new platelets, and found the generation of new platelets was defective.

“Clearly, we show that there’s an obligate need for glucose to bud platelets off from the bone marrow,” Dr Abel said.

In addition, the team observed that young platelets functioned normally, even in the absence of glucose. But as they aged, the platelets were cleared from the circulation earlier than normal because they were being destroyed.

“We identified a new mechanism of necrosis by which the absence of glucose leads to the cleavage of a protein called calpain, which marks them for this necrotic pathway,” Dr Abel said. “If we treated the animals with a calpain inhibitor, we could reduce the increased platelet clearance.”

The team also sought to determine whether platelets could exist and function when mitochondria metabolism is halted.

They injected the mice with oligomycin, which inhibits mitochondrial metabolism. In the mice deficient in GLUT1 and GLUT3, platelet counts dropped to 0 within about 30 minutes. The same effect did not occur in wild-type mice.

“This work defined a very important role for metabolism in how platelets leave the bone marrow, how they come into circulation, and how they stay in circulation,” Dr Abel said. “It could even have implications for why platelets have to be used within a certain period of time when they’re donated at the blood bank—the fresher the better.” ![]()

Team characterizes RIMs in childhood cancer survivors

Neuroscientists say they have uncovered genetic differences between radiation-induced meningiomas (RIMs) and sporadic meningiomas (SMs).

Their work suggests RIMs have a different “mutational landscape” from SMs, a finding that may have “significant therapeutic implications” for childhood cancer survivors who undergo cranial radiation.

Gelareh Zadeh, MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

“Radiation-induced meningiomas appear the same [as SMs] on MRI and pathology, feel the same during surgery, and look the same under the operating microscope,” Dr Zadeh said.

“What’s different is they are more aggressive, tend to recur in multiples, and invade the brain, causing significant morbidity and limitations (or impairments) for individuals who survive following childhood radiation. By understanding the biology, the goal is to identify a therapeutic strategy that could be implemented early on after childhood radiation to prevent the formation of these tumors in the first place.”

To better understand the biology, Dr Zadeh and her colleagues analyzed 31 RIMs. This included 18 tumors from 16 patients with childhood cancers, 9 with leukemia.

The researchers found NF2 gene rearrangements in 12 of the RIMs and noted that such rearrangements have not been observed in SMs.

On the other hand, recurrent mutations characteristic of SMs—AKT1, KLF4, TRAF7, and SMO—were not found in the RIMs.

The researchers also noted that, overall, chromosomal aberrations in RIMs were more complex than those observed in SMs. And combined loss of chromosomes 1p and 22q was common in RIMs (16/18).

“Our research identified a specific rearrangement involving the NF2 gene that causes radiation-induced meningiomas,” said Kenneth Aldape, MD, of University Health Network in Toronto.

“But there are likely other genetic rearrangements that are occurring as a result of that radiation-induced DNA damage. So one of the next steps is to identify what the radiation is doing to the DNA of the meninges.”

“In addition, identifying the subset of childhood cancer patients who are at highest risk to develop meningioma is critical so that they could be followed closely for early detection and management.” ![]()

Neuroscientists say they have uncovered genetic differences between radiation-induced meningiomas (RIMs) and sporadic meningiomas (SMs).

Their work suggests RIMs have a different “mutational landscape” from SMs, a finding that may have “significant therapeutic implications” for childhood cancer survivors who undergo cranial radiation.

Gelareh Zadeh, MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

“Radiation-induced meningiomas appear the same [as SMs] on MRI and pathology, feel the same during surgery, and look the same under the operating microscope,” Dr Zadeh said.

“What’s different is they are more aggressive, tend to recur in multiples, and invade the brain, causing significant morbidity and limitations (or impairments) for individuals who survive following childhood radiation. By understanding the biology, the goal is to identify a therapeutic strategy that could be implemented early on after childhood radiation to prevent the formation of these tumors in the first place.”

To better understand the biology, Dr Zadeh and her colleagues analyzed 31 RIMs. This included 18 tumors from 16 patients with childhood cancers, 9 with leukemia.

The researchers found NF2 gene rearrangements in 12 of the RIMs and noted that such rearrangements have not been observed in SMs.

On the other hand, recurrent mutations characteristic of SMs—AKT1, KLF4, TRAF7, and SMO—were not found in the RIMs.

The researchers also noted that, overall, chromosomal aberrations in RIMs were more complex than those observed in SMs. And combined loss of chromosomes 1p and 22q was common in RIMs (16/18).

“Our research identified a specific rearrangement involving the NF2 gene that causes radiation-induced meningiomas,” said Kenneth Aldape, MD, of University Health Network in Toronto.

“But there are likely other genetic rearrangements that are occurring as a result of that radiation-induced DNA damage. So one of the next steps is to identify what the radiation is doing to the DNA of the meninges.”

“In addition, identifying the subset of childhood cancer patients who are at highest risk to develop meningioma is critical so that they could be followed closely for early detection and management.” ![]()

Neuroscientists say they have uncovered genetic differences between radiation-induced meningiomas (RIMs) and sporadic meningiomas (SMs).

Their work suggests RIMs have a different “mutational landscape” from SMs, a finding that may have “significant therapeutic implications” for childhood cancer survivors who undergo cranial radiation.

Gelareh Zadeh, MD, PhD, of the University of Toronto in Ontario, Canada, and her colleagues reported these findings in Nature Communications.

“Radiation-induced meningiomas appear the same [as SMs] on MRI and pathology, feel the same during surgery, and look the same under the operating microscope,” Dr Zadeh said.

“What’s different is they are more aggressive, tend to recur in multiples, and invade the brain, causing significant morbidity and limitations (or impairments) for individuals who survive following childhood radiation. By understanding the biology, the goal is to identify a therapeutic strategy that could be implemented early on after childhood radiation to prevent the formation of these tumors in the first place.”

To better understand the biology, Dr Zadeh and her colleagues analyzed 31 RIMs. This included 18 tumors from 16 patients with childhood cancers, 9 with leukemia.

The researchers found NF2 gene rearrangements in 12 of the RIMs and noted that such rearrangements have not been observed in SMs.

On the other hand, recurrent mutations characteristic of SMs—AKT1, KLF4, TRAF7, and SMO—were not found in the RIMs.

The researchers also noted that, overall, chromosomal aberrations in RIMs were more complex than those observed in SMs. And combined loss of chromosomes 1p and 22q was common in RIMs (16/18).

“Our research identified a specific rearrangement involving the NF2 gene that causes radiation-induced meningiomas,” said Kenneth Aldape, MD, of University Health Network in Toronto.

“But there are likely other genetic rearrangements that are occurring as a result of that radiation-induced DNA damage. So one of the next steps is to identify what the radiation is doing to the DNA of the meninges.”

“In addition, identifying the subset of childhood cancer patients who are at highest risk to develop meningioma is critical so that they could be followed closely for early detection and management.” ![]()

Drug granted priority review, breakthrough designation for ECD

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review and breakthrough therapy designation to vemurafenib (Zelboraf®) as a treatment for Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) with BRAF V600 mutation.

Vemurafenib is a kinase inhibitor designed to inhibit some mutated forms of BRAF.

The drug is already FDA-approved to treat patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test.

The FDA is expected to make a decision on the approval of vemurafenib in ECD by December 7, 2017.

The supplemental new drug application for vemurafenib in this indication is supported by data from the phase 2 VE-BASKET study.

VE-BASKET was designed to investigate the use of vemurafenib in patients with BRAF V600 mutation-positive diseases, including ECD.

Final results for the 22 people with ECD showed a best overall response rate of 54.5%. The median duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival were not reached at a median follow-up of 26.6 months.

The most common adverse events were joint pain, rash, hair loss, change in heart rhythm, fatigue, skin tags, diarrhea, and thickening of the skin. The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were new skin cancers, high blood pressure, rash, and joint pain.

Initial results from this study were published in NEJM in August 2015.

About priority review

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as a rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review and breakthrough therapy designation to vemurafenib (Zelboraf®) as a treatment for Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) with BRAF V600 mutation.

Vemurafenib is a kinase inhibitor designed to inhibit some mutated forms of BRAF.

The drug is already FDA-approved to treat patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test.

The FDA is expected to make a decision on the approval of vemurafenib in ECD by December 7, 2017.

The supplemental new drug application for vemurafenib in this indication is supported by data from the phase 2 VE-BASKET study.

VE-BASKET was designed to investigate the use of vemurafenib in patients with BRAF V600 mutation-positive diseases, including ECD.

Final results for the 22 people with ECD showed a best overall response rate of 54.5%. The median duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival were not reached at a median follow-up of 26.6 months.

The most common adverse events were joint pain, rash, hair loss, change in heart rhythm, fatigue, skin tags, diarrhea, and thickening of the skin. The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were new skin cancers, high blood pressure, rash, and joint pain.

Initial results from this study were published in NEJM in August 2015.

About priority review

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as a rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted priority review and breakthrough therapy designation to vemurafenib (Zelboraf®) as a treatment for Erdheim-Chester disease (ECD) with BRAF V600 mutation.

Vemurafenib is a kinase inhibitor designed to inhibit some mutated forms of BRAF.

The drug is already FDA-approved to treat patients with unresectable or metastatic melanoma with BRAF V600E mutation as detected by an FDA-approved test.

The FDA is expected to make a decision on the approval of vemurafenib in ECD by December 7, 2017.

The supplemental new drug application for vemurafenib in this indication is supported by data from the phase 2 VE-BASKET study.

VE-BASKET was designed to investigate the use of vemurafenib in patients with BRAF V600 mutation-positive diseases, including ECD.

Final results for the 22 people with ECD showed a best overall response rate of 54.5%. The median duration of response, progression-free survival, and overall survival were not reached at a median follow-up of 26.6 months.

The most common adverse events were joint pain, rash, hair loss, change in heart rhythm, fatigue, skin tags, diarrhea, and thickening of the skin. The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events were new skin cancers, high blood pressure, rash, and joint pain.

Initial results from this study were published in NEJM in August 2015.

About priority review

The FDA grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The agency’s goal is to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

About breakthrough designation

The FDA’s breakthrough designation is intended to expedite the development and review of new treatments for serious or life-threatening conditions.

The designation entitles the company developing a therapy to more intensive FDA guidance on an efficient and accelerated development program, as well as eligibility for other actions to expedite FDA review, such as a rolling submission and priority review.

To earn breakthrough designation, a treatment must show encouraging early clinical results demonstrating substantial improvement over available therapies with regard to a clinically significant endpoint, or it must fulfill an unmet need. ![]()

FDA issues EUA for Zika virus test

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Thermo Fisher Scientific’s TaqPath Zika Virus Kit.

This means the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is authorized for the qualitative detection of RNA from Zika virus and diagnosis of Zika virus infection in human serum and urine (collected alongside a patient-matched serum specimen) from individuals meeting the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s criteria for testing.

The EUA does not mean the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

Testing using the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is authorized to be conducted by laboratories in the US that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, 42 U.S.C. § 263a, to perform high complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories.

More information on the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Thermo Fisher Scientific’s TaqPath Zika Virus Kit.

This means the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is authorized for the qualitative detection of RNA from Zika virus and diagnosis of Zika virus infection in human serum and urine (collected alongside a patient-matched serum specimen) from individuals meeting the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s criteria for testing.

The EUA does not mean the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

Testing using the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is authorized to be conducted by laboratories in the US that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, 42 U.S.C. § 263a, to perform high complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories.

More information on the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has issued an emergency use authorization (EUA) for Thermo Fisher Scientific’s TaqPath Zika Virus Kit.

This means the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is authorized for the qualitative detection of RNA from Zika virus and diagnosis of Zika virus infection in human serum and urine (collected alongside a patient-matched serum specimen) from individuals meeting the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s criteria for testing.

The EUA does not mean the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is FDA cleared or approved.

An EUA allows for the use of unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products in an emergency. The products must be used to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening conditions caused by chemical, biological, radiological, or nuclear threat agents, when there are no adequate alternatives.

The EUA for the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit means the test is only authorized as long as circumstances exist to justify the emergency use of in vitro diagnostics for the detection of Zika virus, unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner.

Testing using the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit is authorized to be conducted by laboratories in the US that are certified under the Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments of 1988, 42 U.S.C. § 263a, to perform high complexity tests, or by similarly qualified non-US laboratories.

More information on the TaqPath Zika Virus Kit and other Zika tests granted EUAs can be found on the FDA’s EUA page. ![]()

Small study advances noninvasive ICP monitoring

A device that noninvasively measures intracranial pressure (ICP) had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring, based on the results of an industry-sponsored study of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

“This study provides the first clinical data on the accuracy of the HS-1000 noninvasive ICP monitor, which uses advanced signal analysis algorithms to evaluate properties of acoustic signals traveling through the brain,” wrote Oliver Ganslandt, MD, of Klinikum Stuttgart (Germany) and his associates. The findings were published online Aug. 8 in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The noninvasive and invasive measurements produced more than 2,500 parallel ICP data points. Notably, each of the two methods produced the same number of data points. Readings averaged 10 (standard deviation, 6.1) mm Hg with invasive monitoring and 9.5 (SD, 4.7) mm Hg for noninvasive monitoring with the HS-1000. Compared with invasive ICP monitoring, the HS-1000 had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89% at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg. Linear regression showed a “strong positive relationship between the [noninvasive and invasive] measurements,” the investigators said. In all, 63% of paired data points fell within 3 mm Hg of each other, and 85% fell within 5 mm Hg of each other. A receiver operating characteristic area under the curve analysis of the two methods generated an area under the curve of almost 90%.

The study did not include children or patients who were pregnant or had ear disease or ear injuries, rhinorrhea or otorrhea, or skull defects, the researchers said. If the HS-1000 holds up in other ongoing studies (NCT02284217, NCT02773901), physicians might be able to use it to decide if patients needs invasive ICP monitoring, they added. Use of the noninvasive method could also help prevent infections and other morbidity associated with invasive ICP monitoring in both neurocritical intensive care units and low-resource settings, they said.

HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

A device that noninvasively measures intracranial pressure (ICP) had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring, based on the results of an industry-sponsored study of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

“This study provides the first clinical data on the accuracy of the HS-1000 noninvasive ICP monitor, which uses advanced signal analysis algorithms to evaluate properties of acoustic signals traveling through the brain,” wrote Oliver Ganslandt, MD, of Klinikum Stuttgart (Germany) and his associates. The findings were published online Aug. 8 in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The noninvasive and invasive measurements produced more than 2,500 parallel ICP data points. Notably, each of the two methods produced the same number of data points. Readings averaged 10 (standard deviation, 6.1) mm Hg with invasive monitoring and 9.5 (SD, 4.7) mm Hg for noninvasive monitoring with the HS-1000. Compared with invasive ICP monitoring, the HS-1000 had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89% at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg. Linear regression showed a “strong positive relationship between the [noninvasive and invasive] measurements,” the investigators said. In all, 63% of paired data points fell within 3 mm Hg of each other, and 85% fell within 5 mm Hg of each other. A receiver operating characteristic area under the curve analysis of the two methods generated an area under the curve of almost 90%.

The study did not include children or patients who were pregnant or had ear disease or ear injuries, rhinorrhea or otorrhea, or skull defects, the researchers said. If the HS-1000 holds up in other ongoing studies (NCT02284217, NCT02773901), physicians might be able to use it to decide if patients needs invasive ICP monitoring, they added. Use of the noninvasive method could also help prevent infections and other morbidity associated with invasive ICP monitoring in both neurocritical intensive care units and low-resource settings, they said.

HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

A device that noninvasively measures intracranial pressure (ICP) had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring, based on the results of an industry-sponsored study of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

“This study provides the first clinical data on the accuracy of the HS-1000 noninvasive ICP monitor, which uses advanced signal analysis algorithms to evaluate properties of acoustic signals traveling through the brain,” wrote Oliver Ganslandt, MD, of Klinikum Stuttgart (Germany) and his associates. The findings were published online Aug. 8 in the Journal of Neurosurgery.

The noninvasive and invasive measurements produced more than 2,500 parallel ICP data points. Notably, each of the two methods produced the same number of data points. Readings averaged 10 (standard deviation, 6.1) mm Hg with invasive monitoring and 9.5 (SD, 4.7) mm Hg for noninvasive monitoring with the HS-1000. Compared with invasive ICP monitoring, the HS-1000 had a sensitivity of 75% and a specificity of 89% at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg. Linear regression showed a “strong positive relationship between the [noninvasive and invasive] measurements,” the investigators said. In all, 63% of paired data points fell within 3 mm Hg of each other, and 85% fell within 5 mm Hg of each other. A receiver operating characteristic area under the curve analysis of the two methods generated an area under the curve of almost 90%.

The study did not include children or patients who were pregnant or had ear disease or ear injuries, rhinorrhea or otorrhea, or skull defects, the researchers said. If the HS-1000 holds up in other ongoing studies (NCT02284217, NCT02773901), physicians might be able to use it to decide if patients needs invasive ICP monitoring, they added. Use of the noninvasive method could also help prevent infections and other morbidity associated with invasive ICP monitoring in both neurocritical intensive care units and low-resource settings, they said.

HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF NEUROSURGERY

Key clinical point: A noninvasive device that measures intracranial pressure generated data that was comparable with standard invasive methods.

Major finding: Sensitivity was 75%, and specificity was 89%, compared with standard invasive monitoring at an arbitrary cutoff of at least 17 mm Hg.

Data source: Noninvasive and invasive intracranial pressure monitoring of 14 patients with traumatic brain injury or subarachnoid hemorrhage.

Disclosures: HeadSense Medical sponsored the study. The researchers had no relevant disclosures.

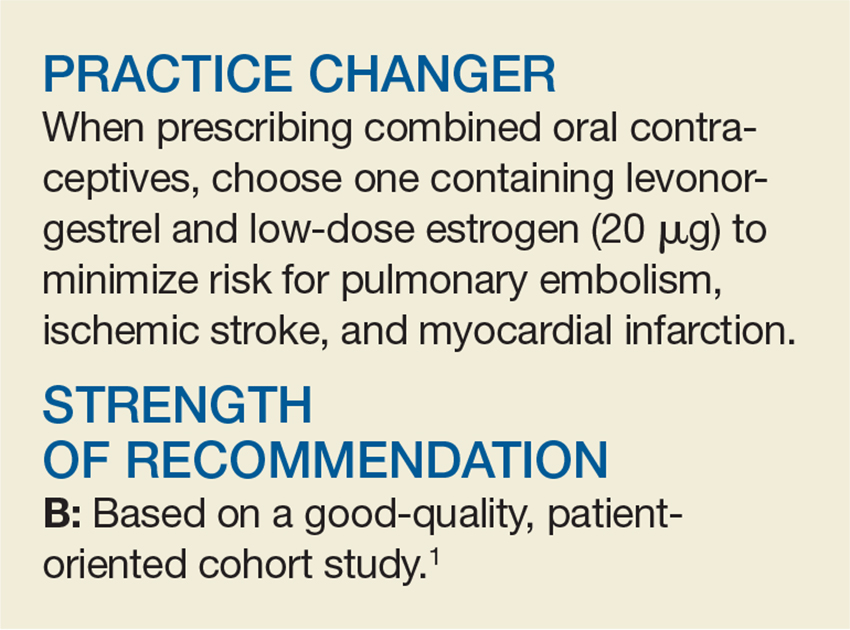

Prescribe This Combined OC With CV Safety in Mind

A 28-year-old woman presents to your office for a routine health maintenance exam. She is currently using an oral contraceptive containing desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol for contraception and is inquiring about a refill for the coming year. What would you recommend?

When choosing a combined oral contraceptive (COC) for a pa

In general, when compared with nonusers, women who use COCs have a two- to four-fold increase in risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and an increased risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke.2,3 More specifically, higher doses of estrogen combined with the progesterones gestodene, desogestrel, and levonorgestrel, are associated with a higher risk for VTE.2-6

In 2012, the European Medicines Agency warned that COCs containing drospirenone were associated with a higher risk for VTE than other preparations, despite similar estrogen content.7 The FDA produced a similar statement that same year, recommending that providers carefully consider the risks and benefits before prescribing contraceptives containing drospirenone.8

The risks for ischemic stroke and MI have not been clearly established for varying doses of estrogen and different progesterones. This large observational study fills that informational gap by providing risk estimates for the various COC options.

STUDY SUMMARY

One COC comes out ahead

The authors used an observational cohort model to determine the effects of different doses of estrogen combined with different progesterones in COCs on the risks for pulmonary embolism (PE), ischemic stroke, and MI.1 Data were collected from the French national health insurance database and the French national hospital discharge database.9,10 The study included nearly 5 million women ages 15 to 49, living in France, who had at least one prescription filled for COCs between July 2010 and September 2012.

The investigators calculated the absolute and relative risks for first PE, ischemic stroke, and MI in women using COC formulations containing either low-dose estrogen (20 µg) or high-dose estrogen (30-40 µg) combined with one of five progesterones (norethisterone, norgestrel, levonorgestrel, desogestrel, gestodene). The relative risk (RR) was adjusted for confounding factors, including age, complimentary universal health insurance, socioeconomic status, hypertension, diabetes, and consultation with a gynecologist in the previous year.

The absolute risk per 100,000 woman-years for all COC use was 33 for PE, 19 for ischemic stroke, and 7 for MI, with a composite risk of 60. The RRs for low-dose estrogen vs high-dose estrogen were 0.75 for PE, 0.82 for ischemic stroke, and 0.56 for MI. The absolute risk reduction (ARR) with low-dose estrogen vs high-dose estrogen was 14/100,000 person-years of use; the number needed to harm (NNH) was 7,143.

Compared with levonorgestrel, desogestrel and gestodene were associated with higher RRs for PE but not arterial events (2.16 for desogestrel and 1.63 for gestodene). For PE, the ARR with levonorgestrel compared to desogestrel and gestodene, respectively, was 19/100,000 and 12/100,000 person-years of use (NNH, 5,263 and 8,333, respectively). The authors concluded that for the same progesterone, using a lower dose of estrogen decreases risk for PE, ischemic stroke, and MI, and that oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel and low-dose estrogen resulted in the lowest overall risks for PE and arterial thromboembolism.

WHAT’S NEW?

Low-dose estrogen + levonorgestrel confer lowest risk

Prior studies have shown that COCs increase the risk for PE and may also increase the risks for ischemic stroke and MI.3,11 Studies have also suggested that a higher dose of estrogen in COCs is associated with an increased risk for VTE.11,12 This study shows that 20 µg of estrogen combined with levonorgestrel is associated with the lowest risks for PE, MI, and ischemic stroke.

CAVEATS

Cohort study, no start date, incomplete tobacco use data

This is an observational cohort study, so it is subject to confounding factors and biases. It does, however, include a very large population, which improves validity. The study did not account for COC start date, which may be confounding because the risk for VTE is highest in the first three months to one year of COC use.12 Data on tobacco use, a significant independent risk factor for arterial but not venous thromboembolism, was incomplete; however, in other studies, it has only marginally affected outcomes.3,13

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Increased vaginal spotting

One potential challenge to implementing this practice changer may be the increased rate of vaginal spotting associated with low-dose estrogen. COCs containing 20 µg of estrogen are associated with spotting in approximately two-thirds of menstrual cycles over the course of a year.14 That said, women may prefer to endure the spotting in light of the improved safety profile of a lower-dose estrogen pill.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[7]:454-456).

1. Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, et al. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2002.

2. Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Svendsen AL, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: national follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2890.

3. Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257-2266.

4. Stegeman BH, de Bastos M, Rosendaal FR, et al. Different combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5298.

5. FDA. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/ucm277384. Accessed July 5, 2017.

6. Seeger JD, Loughlin J, Eng PM, et al. Risk of thromboembolism in women taking ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone and other oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:587-593.

7. European Medicines Agency. PhVWP monthly report on safety concerns, guidelines and general matters. 2012. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2012/01/WC500121387.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2017.

8. FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. 2012. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed July 5, 2017.

9. Tuppin P, de Roquefeuil L, Weill A, et al. French national health insurance information system and the permanent beneficiaries sample. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2010;58:286-290.

10. Moulis G, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Palmaro A, et al. French health insurance databases: what interest for medical research? Rev Med Interne. 2015;36:411-417.

11. Farmer RD, Lawrenson RA, Thompson CR, et al. Population-based study of risk of venous thromboembolism associated with various oral contraceptives. Lancet. 1997;349:83-88.

12. Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001-9. BMJ. 2011;343:d6423.

13. Zhang G, Xu X, Su W, et al. Smoking and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45:736-745.

14. Akerlund M, Røde A, Westergaard J. Comparative profiles of reliability, cycle control and side effects of two oral contraceptive formulations containing 150 micrograms desogestrel and either 30 micrograms or 20 micrograms ethinyl oestradiol. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:832-838.

A 28-year-old woman presents to your office for a routine health maintenance exam. She is currently using an oral contraceptive containing desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol for contraception and is inquiring about a refill for the coming year. What would you recommend?

When choosing a combined oral contraceptive (COC) for a pa

In general, when compared with nonusers, women who use COCs have a two- to four-fold increase in risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and an increased risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke.2,3 More specifically, higher doses of estrogen combined with the progesterones gestodene, desogestrel, and levonorgestrel, are associated with a higher risk for VTE.2-6

In 2012, the European Medicines Agency warned that COCs containing drospirenone were associated with a higher risk for VTE than other preparations, despite similar estrogen content.7 The FDA produced a similar statement that same year, recommending that providers carefully consider the risks and benefits before prescribing contraceptives containing drospirenone.8

The risks for ischemic stroke and MI have not been clearly established for varying doses of estrogen and different progesterones. This large observational study fills that informational gap by providing risk estimates for the various COC options.

STUDY SUMMARY

One COC comes out ahead

The authors used an observational cohort model to determine the effects of different doses of estrogen combined with different progesterones in COCs on the risks for pulmonary embolism (PE), ischemic stroke, and MI.1 Data were collected from the French national health insurance database and the French national hospital discharge database.9,10 The study included nearly 5 million women ages 15 to 49, living in France, who had at least one prescription filled for COCs between July 2010 and September 2012.

The investigators calculated the absolute and relative risks for first PE, ischemic stroke, and MI in women using COC formulations containing either low-dose estrogen (20 µg) or high-dose estrogen (30-40 µg) combined with one of five progesterones (norethisterone, norgestrel, levonorgestrel, desogestrel, gestodene). The relative risk (RR) was adjusted for confounding factors, including age, complimentary universal health insurance, socioeconomic status, hypertension, diabetes, and consultation with a gynecologist in the previous year.

The absolute risk per 100,000 woman-years for all COC use was 33 for PE, 19 for ischemic stroke, and 7 for MI, with a composite risk of 60. The RRs for low-dose estrogen vs high-dose estrogen were 0.75 for PE, 0.82 for ischemic stroke, and 0.56 for MI. The absolute risk reduction (ARR) with low-dose estrogen vs high-dose estrogen was 14/100,000 person-years of use; the number needed to harm (NNH) was 7,143.

Compared with levonorgestrel, desogestrel and gestodene were associated with higher RRs for PE but not arterial events (2.16 for desogestrel and 1.63 for gestodene). For PE, the ARR with levonorgestrel compared to desogestrel and gestodene, respectively, was 19/100,000 and 12/100,000 person-years of use (NNH, 5,263 and 8,333, respectively). The authors concluded that for the same progesterone, using a lower dose of estrogen decreases risk for PE, ischemic stroke, and MI, and that oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel and low-dose estrogen resulted in the lowest overall risks for PE and arterial thromboembolism.

WHAT’S NEW?

Low-dose estrogen + levonorgestrel confer lowest risk

Prior studies have shown that COCs increase the risk for PE and may also increase the risks for ischemic stroke and MI.3,11 Studies have also suggested that a higher dose of estrogen in COCs is associated with an increased risk for VTE.11,12 This study shows that 20 µg of estrogen combined with levonorgestrel is associated with the lowest risks for PE, MI, and ischemic stroke.

CAVEATS

Cohort study, no start date, incomplete tobacco use data

This is an observational cohort study, so it is subject to confounding factors and biases. It does, however, include a very large population, which improves validity. The study did not account for COC start date, which may be confounding because the risk for VTE is highest in the first three months to one year of COC use.12 Data on tobacco use, a significant independent risk factor for arterial but not venous thromboembolism, was incomplete; however, in other studies, it has only marginally affected outcomes.3,13

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Increased vaginal spotting

One potential challenge to implementing this practice changer may be the increased rate of vaginal spotting associated with low-dose estrogen. COCs containing 20 µg of estrogen are associated with spotting in approximately two-thirds of menstrual cycles over the course of a year.14 That said, women may prefer to endure the spotting in light of the improved safety profile of a lower-dose estrogen pill.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[7]:454-456).

A 28-year-old woman presents to your office for a routine health maintenance exam. She is currently using an oral contraceptive containing desogestrel and ethinyl estradiol for contraception and is inquiring about a refill for the coming year. What would you recommend?

When choosing a combined oral contraceptive (COC) for a pa

In general, when compared with nonusers, women who use COCs have a two- to four-fold increase in risk for venous thromboembolism (VTE) and an increased risk for myocardial infarction (MI) and stroke.2,3 More specifically, higher doses of estrogen combined with the progesterones gestodene, desogestrel, and levonorgestrel, are associated with a higher risk for VTE.2-6

In 2012, the European Medicines Agency warned that COCs containing drospirenone were associated with a higher risk for VTE than other preparations, despite similar estrogen content.7 The FDA produced a similar statement that same year, recommending that providers carefully consider the risks and benefits before prescribing contraceptives containing drospirenone.8

The risks for ischemic stroke and MI have not been clearly established for varying doses of estrogen and different progesterones. This large observational study fills that informational gap by providing risk estimates for the various COC options.

STUDY SUMMARY

One COC comes out ahead

The authors used an observational cohort model to determine the effects of different doses of estrogen combined with different progesterones in COCs on the risks for pulmonary embolism (PE), ischemic stroke, and MI.1 Data were collected from the French national health insurance database and the French national hospital discharge database.9,10 The study included nearly 5 million women ages 15 to 49, living in France, who had at least one prescription filled for COCs between July 2010 and September 2012.

The investigators calculated the absolute and relative risks for first PE, ischemic stroke, and MI in women using COC formulations containing either low-dose estrogen (20 µg) or high-dose estrogen (30-40 µg) combined with one of five progesterones (norethisterone, norgestrel, levonorgestrel, desogestrel, gestodene). The relative risk (RR) was adjusted for confounding factors, including age, complimentary universal health insurance, socioeconomic status, hypertension, diabetes, and consultation with a gynecologist in the previous year.

The absolute risk per 100,000 woman-years for all COC use was 33 for PE, 19 for ischemic stroke, and 7 for MI, with a composite risk of 60. The RRs for low-dose estrogen vs high-dose estrogen were 0.75 for PE, 0.82 for ischemic stroke, and 0.56 for MI. The absolute risk reduction (ARR) with low-dose estrogen vs high-dose estrogen was 14/100,000 person-years of use; the number needed to harm (NNH) was 7,143.

Compared with levonorgestrel, desogestrel and gestodene were associated with higher RRs for PE but not arterial events (2.16 for desogestrel and 1.63 for gestodene). For PE, the ARR with levonorgestrel compared to desogestrel and gestodene, respectively, was 19/100,000 and 12/100,000 person-years of use (NNH, 5,263 and 8,333, respectively). The authors concluded that for the same progesterone, using a lower dose of estrogen decreases risk for PE, ischemic stroke, and MI, and that oral contraceptives containing levonorgestrel and low-dose estrogen resulted in the lowest overall risks for PE and arterial thromboembolism.

WHAT’S NEW?

Low-dose estrogen + levonorgestrel confer lowest risk

Prior studies have shown that COCs increase the risk for PE and may also increase the risks for ischemic stroke and MI.3,11 Studies have also suggested that a higher dose of estrogen in COCs is associated with an increased risk for VTE.11,12 This study shows that 20 µg of estrogen combined with levonorgestrel is associated with the lowest risks for PE, MI, and ischemic stroke.

CAVEATS

Cohort study, no start date, incomplete tobacco use data

This is an observational cohort study, so it is subject to confounding factors and biases. It does, however, include a very large population, which improves validity. The study did not account for COC start date, which may be confounding because the risk for VTE is highest in the first three months to one year of COC use.12 Data on tobacco use, a significant independent risk factor for arterial but not venous thromboembolism, was incomplete; however, in other studies, it has only marginally affected outcomes.3,13

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Increased vaginal spotting

One potential challenge to implementing this practice changer may be the increased rate of vaginal spotting associated with low-dose estrogen. COCs containing 20 µg of estrogen are associated with spotting in approximately two-thirds of menstrual cycles over the course of a year.14 That said, women may prefer to endure the spotting in light of the improved safety profile of a lower-dose estrogen pill.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

Copyright © 2017. The Family Physicians Inquiries Network. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with permission from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network and The Journal of Family Practice (2017;66[7]:454-456).

1. Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, et al. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2002.

2. Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Svendsen AL, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: national follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2890.

3. Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257-2266.

4. Stegeman BH, de Bastos M, Rosendaal FR, et al. Different combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5298.

5. FDA. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/ucm277384. Accessed July 5, 2017.

6. Seeger JD, Loughlin J, Eng PM, et al. Risk of thromboembolism in women taking ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone and other oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:587-593.

7. European Medicines Agency. PhVWP monthly report on safety concerns, guidelines and general matters. 2012. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2012/01/WC500121387.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2017.

8. FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. 2012. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed July 5, 2017.

9. Tuppin P, de Roquefeuil L, Weill A, et al. French national health insurance information system and the permanent beneficiaries sample. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2010;58:286-290.

10. Moulis G, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Palmaro A, et al. French health insurance databases: what interest for medical research? Rev Med Interne. 2015;36:411-417.

11. Farmer RD, Lawrenson RA, Thompson CR, et al. Population-based study of risk of venous thromboembolism associated with various oral contraceptives. Lancet. 1997;349:83-88.

12. Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001-9. BMJ. 2011;343:d6423.

13. Zhang G, Xu X, Su W, et al. Smoking and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45:736-745.

14. Akerlund M, Røde A, Westergaard J. Comparative profiles of reliability, cycle control and side effects of two oral contraceptive formulations containing 150 micrograms desogestrel and either 30 micrograms or 20 micrograms ethinyl oestradiol. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:832-838.

1. Weill A, Dalichampt M, Raguideau F, et al. Low dose oestrogen combined oral contraception and risk of pulmonary embolism, stroke, and myocardial infarction in five million French women: cohort study. BMJ. 2016;353:i2002.

2. Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Svendsen AL, et al. Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism: national follow-up study. BMJ. 2009;339:b2890.

3. Lidegaard Ø, Løkkegaard E, Jensen A, et al. Thrombotic stroke and myocardial infarction with hormonal contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:2257-2266.

4. Stegeman BH, de Bastos M, Rosendaal FR, et al. Different combined oral contraceptives and the risk of venous thrombosis: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f5298.

5. FDA. Combined hormonal contraceptives (CHCs) and the risk of cardiovascular disease endpoints. www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/drugsafety/ucm277384. Accessed July 5, 2017.

6. Seeger JD, Loughlin J, Eng PM, et al. Risk of thromboembolism in women taking ethinyl estradiol/drospirenone and other oral contraceptives. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:587-593.

7. European Medicines Agency. PhVWP monthly report on safety concerns, guidelines and general matters. 2012. www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/Report/2012/01/WC500121387.pdf. Accessed July 5, 2017.

8. FDA. FDA Drug Safety Communication: Updated information about the risk of blood clots in women taking birth control pills containing drospirenone. 2012. www.fda.gov/Drugs/DrugSafety/ucm299305.htm. Accessed July 5, 2017.

9. Tuppin P, de Roquefeuil L, Weill A, et al. French national health insurance information system and the permanent beneficiaries sample. Rev Epidemiol Sante Publique. 2010;58:286-290.

10. Moulis G, Lapeyre-Mestre M, Palmaro A, et al. French health insurance databases: what interest for medical research? Rev Med Interne. 2015;36:411-417.

11. Farmer RD, Lawrenson RA, Thompson CR, et al. Population-based study of risk of venous thromboembolism associated with various oral contraceptives. Lancet. 1997;349:83-88.

12. Lidegaard Ø, Nielsen LH, Skovlund CW, et al. Risk of venous thromboembolism from use of oral contraceptives containing different progestogens and oestrogen doses: Danish cohort study, 2001-9. BMJ. 2011;343:d6423.

13. Zhang G, Xu X, Su W, et al. Smoking and risk of venous thromboembolism: a systematic review. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2014;45:736-745.

14. Akerlund M, Røde A, Westergaard J. Comparative profiles of reliability, cycle control and side effects of two oral contraceptive formulations containing 150 micrograms desogestrel and either 30 micrograms or 20 micrograms ethinyl oestradiol. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1993;100:832-838.

Thyroid Storm: Early Management and Prevention

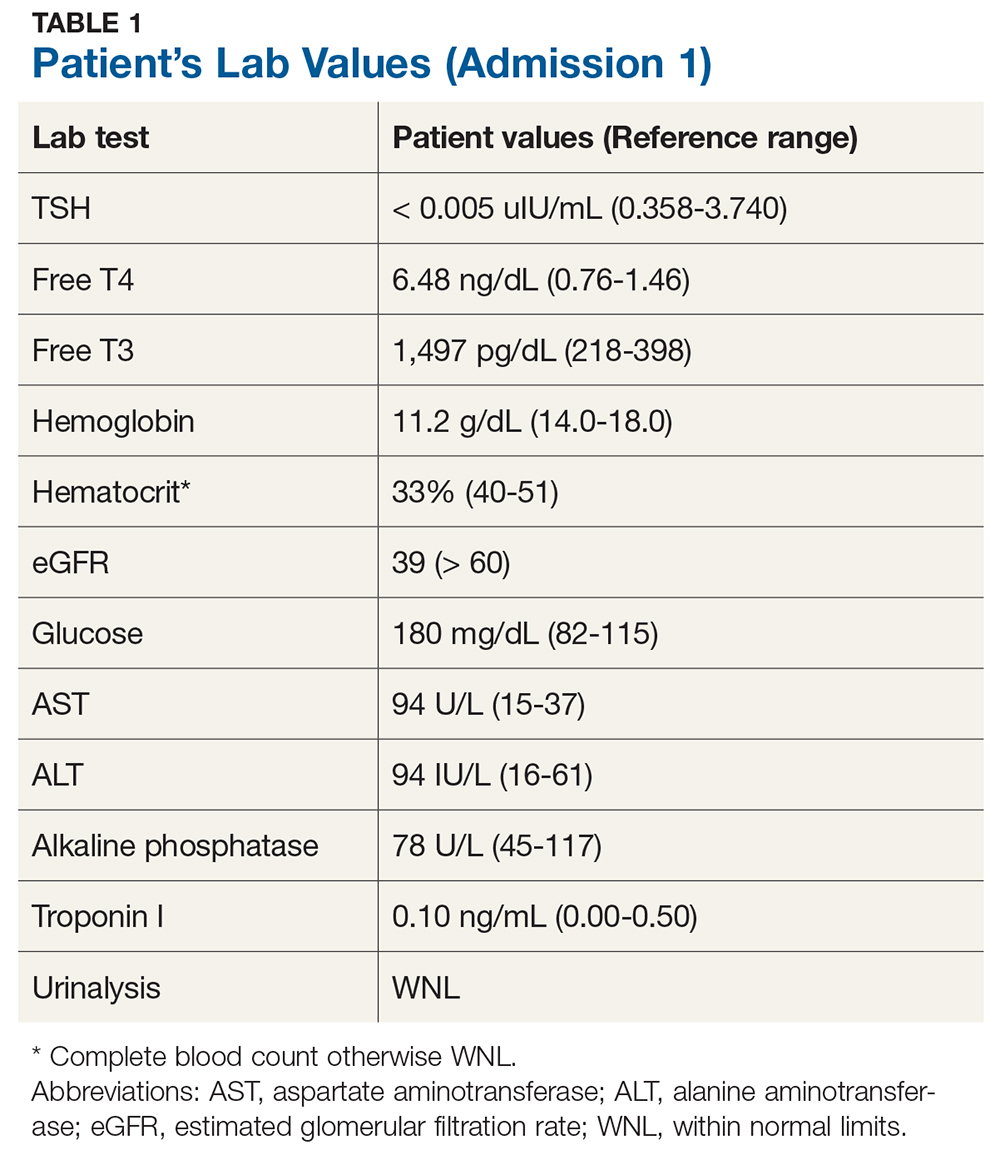

A 73-year-old man is transported to the emergency department (ED) by ambulance for nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and weakness of three days’ duration. Earlier today, he presented to his primary care provider with these symptoms and was found to be hypotensive; he was advised to go to the ED but instead went home against medical advice.

The patient’s medical history is significant for type 2 diabetes, stage 3b chronic kidney disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. He has undergone stent placement and triple coronary artery bypass graft surgery. His medication list includes insulin glargine, glimepiride, liraglutide, atorvastatin, benazepril, carvedilol, amlodipine, clopidogrel, and tamsulosin.

Upon admission, the patient has a pulse of 98 beats/min; temperature, 98.2°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; and PO2, 98 mm Hg. An ECG, chest radiograph, and CT (without contrast) of the head, chest, and abdomen are all within normal limits. Lab evaluation is significant for severe thyrotoxicosis (see Table 1).

Endocrinology consult is requested. Further testing yields the following findings

- Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin: 309% (reference range, < 30%)

- Nuclear medicine thyroid scan with uptake: 6-hour uptake of 70.3% (10%-25%) and 24-hour uptake, 81.8% (15%-35%)

- Homogeneous radiotracer uptake within the thyroid gland: no evidence of hot or cold nodules

- Thyroid ultrasound: bilateral enlarged heterogeneous gland and multiple subcentimeter nodules (largest measuring 6 × 7 mm)

These results confirm a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Treatment options, including antithyroid medications, radioactive iodine ablation (RAI), and surgery, are discussed. The patient is treated with RAI therapy (10 mCi) and discharged from the hospital.

Six days later, however, he returns to the ED with severe intermittent dizziness and lightheadedness of two hours’ duration, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and mild shortness of breath. His vital signs include a pulse of 116 beats/min; temperature, 98.1°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1, blood pressure, 154/88 mm Hg; and PO2, 100 mm Hg.

His lab values include

- TSH < 0.005 uIU/mL

- Free T4, 8.01 ng/dL

- Free T3, 3,701 pg/dL

- eGFR, 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

Cardiology consult is requested. A pacemaker is placed for bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome, and the patient is put on rivaroxaban for stroke prevention.

The endocrinologist suspects post-RAI thyroiditis or ineffective RAI treatment. The patient is started on methimazole (10 mg bid), and his carvedilol is replaced with metoprolol (50 mg bid).

Two weeks postdischarge, the patient returns to the office. Although he says he’s doing better, he seems uneasy and agitated and has a pulse of 120 beats/min. His methimazole and metoprolol are increased (to 10 mg tid and 50 mg tid, respectively).

Another two weeks later, lab results still show elevated thyroid levels—now with increased enzyme levels on liver function testing. The patient reports worsening dizziness and shortness of breath. He is sent back to hospital and admitted for inpatient management, with urgent surgical consult for thyroidectomy. Total thyroidectomy is successfully performed, and the final pathology report shows a benign goiter.

DISCUSSION

Thyroid storm is an extreme form of thyrotoxicosis with an associated mortality rate of 8% to 25%.1 When thyroid hormone levels are elevated, adrenaline receptors are upregulated—but, while it is possible for persistent thyrotoxicosis to progress to thyroid storm on its own, a surge of adrenaline is usually needed. Most cases are triggered by acute stressors (ie, myocardial infarction, surgery, anesthesia, labor and delivery) in the context of underlying thyrotoxicosis.1

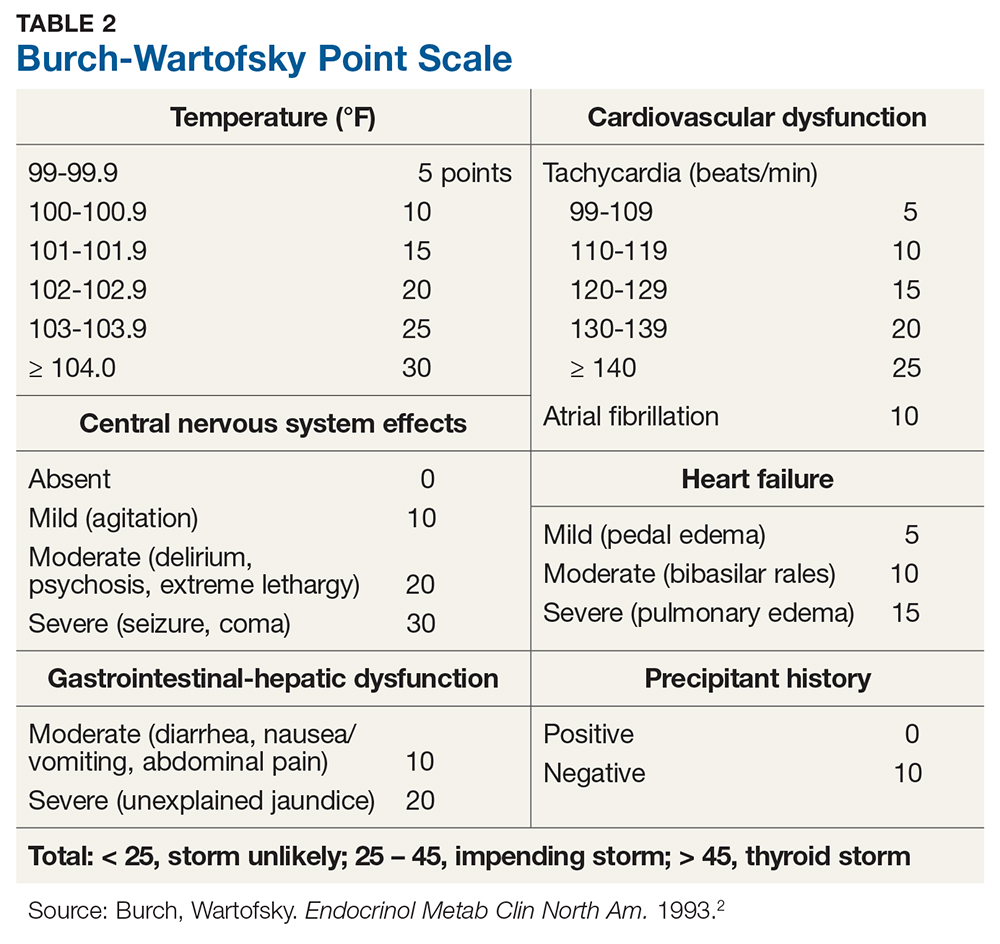

Diagnosis of thyroid storm is made clinically in patients who are thyrotoxic and present with systemic decompensation (ie, altered mental status, cardiovascular dysfunction, hyperpyrexia). Although no universally accepted criteria currently exist, the Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale (BWPS; see Table 2) can be used to assess disease severity and guide the extent of treatment and monitoring.2 However, this measure should not replace clinical judgment—the distinction between compensated thyrotoxicosis and decompensating thyrotoxicosis (thyroid storm) should be made by sound but prompt clinical assessment.

Once thyroid storm is suspected, aggressive treatment should be implemented to improve the systemic thyrotoxic state. Propylthiouracil (PTU) is preferred over methimazole, as it blocks T4 to T3 conversion in addition to blocking new hormone synthesis. Propranolol is the best choice of ß-blocker because it also blocks T4 to T3 conversion and controls cardiac rhythm.

Iodine can rapidly block new hormone synthesis and release; it is often used to reduce thyroid hormone levels prior to emergency thyroid surgery. However, it should be given at least one hour after a dose of PTU. Hydrocortisone is given prophylactically for relative adrenal insufficiency (due to rapid cortisol clearance during thyrotoxic state); it may block T4 to T3 conversion as well. Volume resuscitation, respiratory care, temperature control (eg, antipyretics, cooling blankets), and nutritional support should also be incorporated, ideally in the intensive care unit (ICU). During or after thyroid storm management, treatment of the precipitating event/illness and of hyperthyroidism should be initiated to prevent recurrence.1

The patient’s initial BWPS was 30 (gastrointestinal [GI] score 10 + central nervous system [CNS] score 10 + without precipitating factor 10), which put him in the “impending storm” category. At his second ED visit, his BWPS was 40 (cardiovascular score 10 + A-fib 10 + GI score 10 + CNS score 10 + precipitating factor [RAI ablation] score 0)—still in the “impending storm” category but certainly indicating a worsened state.

RAI for hyperthyroidism can transiently increase thyroid hormone levels due to inflammation of the gland. To prevent exacerbation of the thyrotoxic state, pretreatment with methimazole should be considered in patients with risk factors (eg, older age, cardiovascular complications, cerebrovascular disease, pulmonary disease, renal failure, infection, trauma, and poorly controlled diabetes). Patients should also be placed on ß-blockers prior to treatment, in anticipation of a transient rise in thyroid hormone levels.

Due to this patient’s age, severity of thyrotoxicosis, and multiple risk factors, strong consideration should have been given to pretreating him with antithyroid medication and a ß-blocker before definitive treatment was given. This would have potentially averted his subsequent hospital visits and urgent need for thyroidectomy.

CONCLUSION

Thyroid storm is an uncommon but serious medical condition with a high mortality rate. Prompt recognition and an aggressive multimodal treatment approach, ideally in the ICU, are paramount to stabilize patients and seek definitive treatment.

1. Ross DS, Burch HB, Cooper DS, et al. 2016 American Thyroid Association guidelines for diagnosis and management of hyperthyroidism and other causes of thyrotoxicosis. Thyroid. 2016;26(10):1343-1421.

2. Burch HB, Wartofsky L. Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis: thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 1993; 22(2):263-277.

A 73-year-old man is transported to the emergency department (ED) by ambulance for nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and weakness of three days’ duration. Earlier today, he presented to his primary care provider with these symptoms and was found to be hypotensive; he was advised to go to the ED but instead went home against medical advice.

The patient’s medical history is significant for type 2 diabetes, stage 3b chronic kidney disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. He has undergone stent placement and triple coronary artery bypass graft surgery. His medication list includes insulin glargine, glimepiride, liraglutide, atorvastatin, benazepril, carvedilol, amlodipine, clopidogrel, and tamsulosin.

Upon admission, the patient has a pulse of 98 beats/min; temperature, 98.2°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; and PO2, 98 mm Hg. An ECG, chest radiograph, and CT (without contrast) of the head, chest, and abdomen are all within normal limits. Lab evaluation is significant for severe thyrotoxicosis (see Table 1).

Endocrinology consult is requested. Further testing yields the following findings

- Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin: 309% (reference range, < 30%)

- Nuclear medicine thyroid scan with uptake: 6-hour uptake of 70.3% (10%-25%) and 24-hour uptake, 81.8% (15%-35%)

- Homogeneous radiotracer uptake within the thyroid gland: no evidence of hot or cold nodules

- Thyroid ultrasound: bilateral enlarged heterogeneous gland and multiple subcentimeter nodules (largest measuring 6 × 7 mm)

These results confirm a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Treatment options, including antithyroid medications, radioactive iodine ablation (RAI), and surgery, are discussed. The patient is treated with RAI therapy (10 mCi) and discharged from the hospital.

Six days later, however, he returns to the ED with severe intermittent dizziness and lightheadedness of two hours’ duration, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and mild shortness of breath. His vital signs include a pulse of 116 beats/min; temperature, 98.1°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1, blood pressure, 154/88 mm Hg; and PO2, 100 mm Hg.

His lab values include

- TSH < 0.005 uIU/mL

- Free T4, 8.01 ng/dL

- Free T3, 3,701 pg/dL

- eGFR, 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

Cardiology consult is requested. A pacemaker is placed for bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome, and the patient is put on rivaroxaban for stroke prevention.

The endocrinologist suspects post-RAI thyroiditis or ineffective RAI treatment. The patient is started on methimazole (10 mg bid), and his carvedilol is replaced with metoprolol (50 mg bid).

Two weeks postdischarge, the patient returns to the office. Although he says he’s doing better, he seems uneasy and agitated and has a pulse of 120 beats/min. His methimazole and metoprolol are increased (to 10 mg tid and 50 mg tid, respectively).

Another two weeks later, lab results still show elevated thyroid levels—now with increased enzyme levels on liver function testing. The patient reports worsening dizziness and shortness of breath. He is sent back to hospital and admitted for inpatient management, with urgent surgical consult for thyroidectomy. Total thyroidectomy is successfully performed, and the final pathology report shows a benign goiter.

DISCUSSION

Thyroid storm is an extreme form of thyrotoxicosis with an associated mortality rate of 8% to 25%.1 When thyroid hormone levels are elevated, adrenaline receptors are upregulated—but, while it is possible for persistent thyrotoxicosis to progress to thyroid storm on its own, a surge of adrenaline is usually needed. Most cases are triggered by acute stressors (ie, myocardial infarction, surgery, anesthesia, labor and delivery) in the context of underlying thyrotoxicosis.1

Diagnosis of thyroid storm is made clinically in patients who are thyrotoxic and present with systemic decompensation (ie, altered mental status, cardiovascular dysfunction, hyperpyrexia). Although no universally accepted criteria currently exist, the Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale (BWPS; see Table 2) can be used to assess disease severity and guide the extent of treatment and monitoring.2 However, this measure should not replace clinical judgment—the distinction between compensated thyrotoxicosis and decompensating thyrotoxicosis (thyroid storm) should be made by sound but prompt clinical assessment.

Once thyroid storm is suspected, aggressive treatment should be implemented to improve the systemic thyrotoxic state. Propylthiouracil (PTU) is preferred over methimazole, as it blocks T4 to T3 conversion in addition to blocking new hormone synthesis. Propranolol is the best choice of ß-blocker because it also blocks T4 to T3 conversion and controls cardiac rhythm.

Iodine can rapidly block new hormone synthesis and release; it is often used to reduce thyroid hormone levels prior to emergency thyroid surgery. However, it should be given at least one hour after a dose of PTU. Hydrocortisone is given prophylactically for relative adrenal insufficiency (due to rapid cortisol clearance during thyrotoxic state); it may block T4 to T3 conversion as well. Volume resuscitation, respiratory care, temperature control (eg, antipyretics, cooling blankets), and nutritional support should also be incorporated, ideally in the intensive care unit (ICU). During or after thyroid storm management, treatment of the precipitating event/illness and of hyperthyroidism should be initiated to prevent recurrence.1

The patient’s initial BWPS was 30 (gastrointestinal [GI] score 10 + central nervous system [CNS] score 10 + without precipitating factor 10), which put him in the “impending storm” category. At his second ED visit, his BWPS was 40 (cardiovascular score 10 + A-fib 10 + GI score 10 + CNS score 10 + precipitating factor [RAI ablation] score 0)—still in the “impending storm” category but certainly indicating a worsened state.

RAI for hyperthyroidism can transiently increase thyroid hormone levels due to inflammation of the gland. To prevent exacerbation of the thyrotoxic state, pretreatment with methimazole should be considered in patients with risk factors (eg, older age, cardiovascular complications, cerebrovascular disease, pulmonary disease, renal failure, infection, trauma, and poorly controlled diabetes). Patients should also be placed on ß-blockers prior to treatment, in anticipation of a transient rise in thyroid hormone levels.

Due to this patient’s age, severity of thyrotoxicosis, and multiple risk factors, strong consideration should have been given to pretreating him with antithyroid medication and a ß-blocker before definitive treatment was given. This would have potentially averted his subsequent hospital visits and urgent need for thyroidectomy.

CONCLUSION

Thyroid storm is an uncommon but serious medical condition with a high mortality rate. Prompt recognition and an aggressive multimodal treatment approach, ideally in the ICU, are paramount to stabilize patients and seek definitive treatment.

A 73-year-old man is transported to the emergency department (ED) by ambulance for nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and weakness of three days’ duration. Earlier today, he presented to his primary care provider with these symptoms and was found to be hypotensive; he was advised to go to the ED but instead went home against medical advice.

The patient’s medical history is significant for type 2 diabetes, stage 3b chronic kidney disease, dyslipidemia, hypertension, coronary artery disease, and benign prostatic hyperplasia. He has undergone stent placement and triple coronary artery bypass graft surgery. His medication list includes insulin glargine, glimepiride, liraglutide, atorvastatin, benazepril, carvedilol, amlodipine, clopidogrel, and tamsulosin.

Upon admission, the patient has a pulse of 98 beats/min; temperature, 98.2°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1; and PO2, 98 mm Hg. An ECG, chest radiograph, and CT (without contrast) of the head, chest, and abdomen are all within normal limits. Lab evaluation is significant for severe thyrotoxicosis (see Table 1).

Endocrinology consult is requested. Further testing yields the following findings

- Thyroid-stimulating immunoglobulin: 309% (reference range, < 30%)

- Nuclear medicine thyroid scan with uptake: 6-hour uptake of 70.3% (10%-25%) and 24-hour uptake, 81.8% (15%-35%)

- Homogeneous radiotracer uptake within the thyroid gland: no evidence of hot or cold nodules

- Thyroid ultrasound: bilateral enlarged heterogeneous gland and multiple subcentimeter nodules (largest measuring 6 × 7 mm)

These results confirm a diagnosis of Graves’ disease. Treatment options, including antithyroid medications, radioactive iodine ablation (RAI), and surgery, are discussed. The patient is treated with RAI therapy (10 mCi) and discharged from the hospital.

Six days later, however, he returns to the ED with severe intermittent dizziness and lightheadedness of two hours’ duration, new-onset atrial fibrillation (A-fib), and mild shortness of breath. His vital signs include a pulse of 116 beats/min; temperature, 98.1°F; respiratory rate, 18 breaths/min-1, blood pressure, 154/88 mm Hg; and PO2, 100 mm Hg.

His lab values include

- TSH < 0.005 uIU/mL

- Free T4, 8.01 ng/dL

- Free T3, 3,701 pg/dL

- eGFR, 60 mL/min/1.73 m2

Cardiology consult is requested. A pacemaker is placed for bradycardia-tachycardia syndrome, and the patient is put on rivaroxaban for stroke prevention.

The endocrinologist suspects post-RAI thyroiditis or ineffective RAI treatment. The patient is started on methimazole (10 mg bid), and his carvedilol is replaced with metoprolol (50 mg bid).

Two weeks postdischarge, the patient returns to the office. Although he says he’s doing better, he seems uneasy and agitated and has a pulse of 120 beats/min. His methimazole and metoprolol are increased (to 10 mg tid and 50 mg tid, respectively).

Another two weeks later, lab results still show elevated thyroid levels—now with increased enzyme levels on liver function testing. The patient reports worsening dizziness and shortness of breath. He is sent back to hospital and admitted for inpatient management, with urgent surgical consult for thyroidectomy. Total thyroidectomy is successfully performed, and the final pathology report shows a benign goiter.

DISCUSSION

Thyroid storm is an extreme form of thyrotoxicosis with an associated mortality rate of 8% to 25%.1 When thyroid hormone levels are elevated, adrenaline receptors are upregulated—but, while it is possible for persistent thyrotoxicosis to progress to thyroid storm on its own, a surge of adrenaline is usually needed. Most cases are triggered by acute stressors (ie, myocardial infarction, surgery, anesthesia, labor and delivery) in the context of underlying thyrotoxicosis.1

Diagnosis of thyroid storm is made clinically in patients who are thyrotoxic and present with systemic decompensation (ie, altered mental status, cardiovascular dysfunction, hyperpyrexia). Although no universally accepted criteria currently exist, the Burch-Wartofsky Point Scale (BWPS; see Table 2) can be used to assess disease severity and guide the extent of treatment and monitoring.2 However, this measure should not replace clinical judgment—the distinction between compensated thyrotoxicosis and decompensating thyrotoxicosis (thyroid storm) should be made by sound but prompt clinical assessment.