User login

Pediatric version of SOFA effective

An age-adjusted version of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for sepsis has been found to be at least as good, if not better than, other pediatric organ dysfunction scores at predicting in-hospital mortality.

Writing in the Aug. 7 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics, researchers reported the outcome of a retrospective observational cohort study in 6,303 critically ill patients aged 21 years or younger, which was used to adapt and validate a pediatric version of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score.

“One of the major limitations of the SOFA score is that it was developed for adult patients and contains measures that vary significantly with age, which makes it unsuitable for children,” wrote Travis J. Matics, DO, and L. Nelson Sanchez-Pinto, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Chicago.

Several pediatric organ dysfunction scores exist, but their range, scale, and coverage are different from those of the SOFA score, which makes them difficult to use concurrently (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2352).

“Fundamentally, having different definitions of sepsis for patients above or below the pediatric-adult threshold has no known physiologic justification and should therefore be avoided,” the authors wrote.

In this study, they modified the age-dependent cardiovascular and renal variables of the adult SOFA score by using validated cut-offs from the updated Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD-2) scoring system. They also expanded the respiratory subscore to incorporate the SpO2:FiO2 ratio as an alternative surrogate of lung injury.

The neurologic subscore, based on the Glasgow Coma Scale, was changed to a pediatric version of the scale. The coagulation and hepatic criteria remained the same as the adult version of the score.

Validating the pediatric version of the SOFA score (pSOFA) score in 8,711 hospital encounters, researchers found that nonsurvivors had a significantly higher median maximum pSOFA score, compared with survivors (13 vs. 2, P less than .001). The area under the curve (AUC) for discriminating in-hospital mortality was 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.95) and remained stable across sex, age groups, and admission types.

The maximum pSOFA score was as good as the PELOD and PELOD-2 scales at discriminating in-hospital mortality and better than the Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score. It also showed “excellent” discrimination of in-hospital mortality among the 48.4% of patients who had a confirmed or suspected infection in the pediatric intensive care unit (AUC, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.91-0.94), Dr. Matics and Dr. Sanchez-Pinto reported.

Researchers also looked at the clinical utility of pSOFA on the day of admission, compared with the Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) III score, and found the two were similar, while the pSOFA outperformed other organ dysfunction scores in this setting.

Overall, 14.1% of the pediatric intensive care population met the sepsis criteria according to the adapted definitions and pSOFA scores, and this group had a mortality of 12.1%. Four percent of the population met the criteria for septic shock, with a mortality of 32.3%.

The SOFA score incorporates respiratory, coagulation, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and neurologic variables. The authors, however, argued that it does not account for age-related variability, in particular in renal criteria and the detrimental effects of kidney dysfunction in younger patients.

“In addition, the respiratory subscore criteria – based on the ratio of PaO2 to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) – have not been modified in previous adaptations of the SOFA score even though the decreased use of arterial blood gases in children is a known limitation,” they wrote.

“Having a harmonized definition of sepsis across age groups while recognizing the importance of the age-based variation of its measures can have many benefits, including better design of clinical trials, improved accuracy of reported outcomes, and better translation of the research and clinical strategies in the management of sepsis,” Dr. Matics and Dr. Sanchez-Pinto said.

They acknowledged, however, that their findings were limited because they were generated using retrospective data and needed to be validated in a large multicenter sample of critically ill children. They also pointed out that they did not evaluate the performance of pSOFA as a longitudinal biomarker and suggested that such studies would improve understanding of pSOFA’s clinical utility.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

An age-adjusted version of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for sepsis has been found to be at least as good, if not better than, other pediatric organ dysfunction scores at predicting in-hospital mortality.

Writing in the Aug. 7 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics, researchers reported the outcome of a retrospective observational cohort study in 6,303 critically ill patients aged 21 years or younger, which was used to adapt and validate a pediatric version of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score.

“One of the major limitations of the SOFA score is that it was developed for adult patients and contains measures that vary significantly with age, which makes it unsuitable for children,” wrote Travis J. Matics, DO, and L. Nelson Sanchez-Pinto, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Chicago.

Several pediatric organ dysfunction scores exist, but their range, scale, and coverage are different from those of the SOFA score, which makes them difficult to use concurrently (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2352).

“Fundamentally, having different definitions of sepsis for patients above or below the pediatric-adult threshold has no known physiologic justification and should therefore be avoided,” the authors wrote.

In this study, they modified the age-dependent cardiovascular and renal variables of the adult SOFA score by using validated cut-offs from the updated Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD-2) scoring system. They also expanded the respiratory subscore to incorporate the SpO2:FiO2 ratio as an alternative surrogate of lung injury.

The neurologic subscore, based on the Glasgow Coma Scale, was changed to a pediatric version of the scale. The coagulation and hepatic criteria remained the same as the adult version of the score.

Validating the pediatric version of the SOFA score (pSOFA) score in 8,711 hospital encounters, researchers found that nonsurvivors had a significantly higher median maximum pSOFA score, compared with survivors (13 vs. 2, P less than .001). The area under the curve (AUC) for discriminating in-hospital mortality was 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.95) and remained stable across sex, age groups, and admission types.

The maximum pSOFA score was as good as the PELOD and PELOD-2 scales at discriminating in-hospital mortality and better than the Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score. It also showed “excellent” discrimination of in-hospital mortality among the 48.4% of patients who had a confirmed or suspected infection in the pediatric intensive care unit (AUC, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.91-0.94), Dr. Matics and Dr. Sanchez-Pinto reported.

Researchers also looked at the clinical utility of pSOFA on the day of admission, compared with the Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) III score, and found the two were similar, while the pSOFA outperformed other organ dysfunction scores in this setting.

Overall, 14.1% of the pediatric intensive care population met the sepsis criteria according to the adapted definitions and pSOFA scores, and this group had a mortality of 12.1%. Four percent of the population met the criteria for septic shock, with a mortality of 32.3%.

The SOFA score incorporates respiratory, coagulation, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and neurologic variables. The authors, however, argued that it does not account for age-related variability, in particular in renal criteria and the detrimental effects of kidney dysfunction in younger patients.

“In addition, the respiratory subscore criteria – based on the ratio of PaO2 to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) – have not been modified in previous adaptations of the SOFA score even though the decreased use of arterial blood gases in children is a known limitation,” they wrote.

“Having a harmonized definition of sepsis across age groups while recognizing the importance of the age-based variation of its measures can have many benefits, including better design of clinical trials, improved accuracy of reported outcomes, and better translation of the research and clinical strategies in the management of sepsis,” Dr. Matics and Dr. Sanchez-Pinto said.

They acknowledged, however, that their findings were limited because they were generated using retrospective data and needed to be validated in a large multicenter sample of critically ill children. They also pointed out that they did not evaluate the performance of pSOFA as a longitudinal biomarker and suggested that such studies would improve understanding of pSOFA’s clinical utility.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

An age-adjusted version of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for sepsis has been found to be at least as good, if not better than, other pediatric organ dysfunction scores at predicting in-hospital mortality.

Writing in the Aug. 7 online edition of JAMA Pediatrics, researchers reported the outcome of a retrospective observational cohort study in 6,303 critically ill patients aged 21 years or younger, which was used to adapt and validate a pediatric version of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score.

“One of the major limitations of the SOFA score is that it was developed for adult patients and contains measures that vary significantly with age, which makes it unsuitable for children,” wrote Travis J. Matics, DO, and L. Nelson Sanchez-Pinto, MD, of the department of pediatrics at the University of Chicago.

Several pediatric organ dysfunction scores exist, but their range, scale, and coverage are different from those of the SOFA score, which makes them difficult to use concurrently (JAMA Pediatr. 2017 Aug 7. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2352).

“Fundamentally, having different definitions of sepsis for patients above or below the pediatric-adult threshold has no known physiologic justification and should therefore be avoided,” the authors wrote.

In this study, they modified the age-dependent cardiovascular and renal variables of the adult SOFA score by using validated cut-offs from the updated Pediatric Logistic Organ Dysfunction (PELOD-2) scoring system. They also expanded the respiratory subscore to incorporate the SpO2:FiO2 ratio as an alternative surrogate of lung injury.

The neurologic subscore, based on the Glasgow Coma Scale, was changed to a pediatric version of the scale. The coagulation and hepatic criteria remained the same as the adult version of the score.

Validating the pediatric version of the SOFA score (pSOFA) score in 8,711 hospital encounters, researchers found that nonsurvivors had a significantly higher median maximum pSOFA score, compared with survivors (13 vs. 2, P less than .001). The area under the curve (AUC) for discriminating in-hospital mortality was 0.94 (95% confidence interval, 0.92-0.95) and remained stable across sex, age groups, and admission types.

The maximum pSOFA score was as good as the PELOD and PELOD-2 scales at discriminating in-hospital mortality and better than the Pediatric Multiple Organ Dysfunction Score. It also showed “excellent” discrimination of in-hospital mortality among the 48.4% of patients who had a confirmed or suspected infection in the pediatric intensive care unit (AUC, 0.92; 95% CI, 0.91-0.94), Dr. Matics and Dr. Sanchez-Pinto reported.

Researchers also looked at the clinical utility of pSOFA on the day of admission, compared with the Pediatric Risk of Mortality (PRISM) III score, and found the two were similar, while the pSOFA outperformed other organ dysfunction scores in this setting.

Overall, 14.1% of the pediatric intensive care population met the sepsis criteria according to the adapted definitions and pSOFA scores, and this group had a mortality of 12.1%. Four percent of the population met the criteria for septic shock, with a mortality of 32.3%.

The SOFA score incorporates respiratory, coagulation, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, and neurologic variables. The authors, however, argued that it does not account for age-related variability, in particular in renal criteria and the detrimental effects of kidney dysfunction in younger patients.

“In addition, the respiratory subscore criteria – based on the ratio of PaO2 to the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) – have not been modified in previous adaptations of the SOFA score even though the decreased use of arterial blood gases in children is a known limitation,” they wrote.

“Having a harmonized definition of sepsis across age groups while recognizing the importance of the age-based variation of its measures can have many benefits, including better design of clinical trials, improved accuracy of reported outcomes, and better translation of the research and clinical strategies in the management of sepsis,” Dr. Matics and Dr. Sanchez-Pinto said.

They acknowledged, however, that their findings were limited because they were generated using retrospective data and needed to be validated in a large multicenter sample of critically ill children. They also pointed out that they did not evaluate the performance of pSOFA as a longitudinal biomarker and suggested that such studies would improve understanding of pSOFA’s clinical utility.

No conflicts of interest were reported.

FROM JAMA PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: A pediatric version of the Sequential Organ Failure Assessment score for sepsis can discriminate in-hospital mortality in critically ill children.

Major finding: An age-adjusted version of the SOFA score for sepsis has found to be at least as good, if not better than, other pediatric organ dysfunction scores at predicting in-hospital mortality.

Data source: A retrospective observational cohort study in 6,303 critically ill patients aged 21 years or younger.

Disclosures: No conflicts of interest were declared.

Pulmonary Perspectives ® Immigrants in Health Care

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

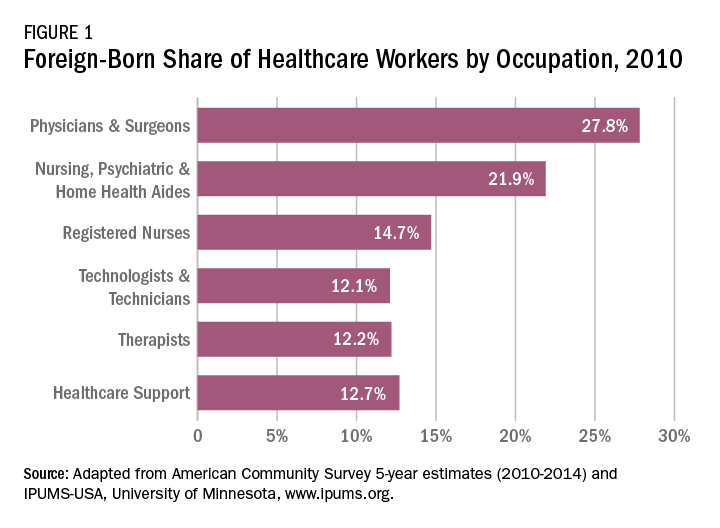

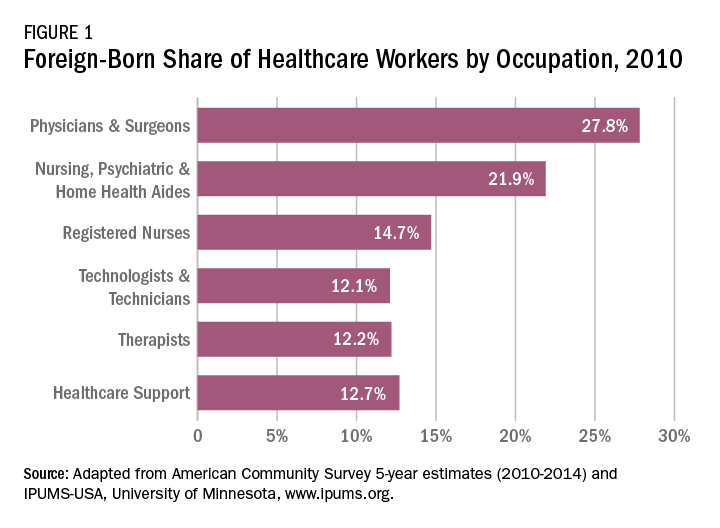

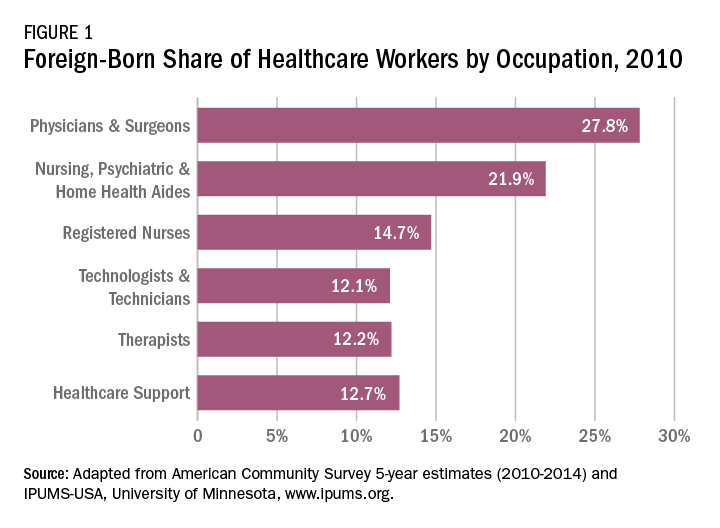

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

July 4th was bittersweet for me, this year. Independence days of my childhood were spent grilling, sitting by the campfire on the lakes and rivers of Northern Michigan, watching the fireworks turn the night sky red, white, and blue. These fond memories were a painful reminder that others like me may not have the privilege to experience such joy, secondary to their background.

I don’t remember the first time that I heard the tale of my parents coming to America. They were both medical students from India, who received brightly colored brochures from American hospitals inviting them to come further their medical training. Due to the deficit of physicians in the United States, the hospitals even loaned money to medical students, so they would do their residencies in America. My parents took advantage of this opportunity and embarked on a journey that would define their lives. Often, my mother would talk about my father leaving for the hospital on Friday morning only to return to his wife and two toddlers on Monday afternoon. As a child, I remember my uncles taking bottles of milk to the hospital to make chai to fuel through their grueling overnight calls. These immigrant tales were the backdrop of my childhood, the basis of my understanding of America. I was raised in an immigrant community of physicians who were grateful for the opportunities that America offered them. They worked hard, reaped significant rewards, and substantially contributed to their communities. Maybe, I am just nostalgic for my childhood, but this experience, I believe, is still an integral part of the American dream.

The recent choice to restrict immigration from specific nations is disturbing at best and reminiscent of an America that I have never known. More than 7,000 physicians from Libya, Iran, Somalia, Sudan, Syria, and Yemen are currently working in the United States, providing care for more than 14 million people. An estimated 94% of American communities have at least one doctor from one of the targeted countries. These physicians are more likely to work in rural and underserved communities and provide essential services.1 They are immigrants who have come to America to better their lives and, in turn, have bettered the lives of those around them. They are my parents. Not all physicians are good people or are worthy of the American dream, but America is a better place for welcoming those who are willing to work hard to make a better life for themselves. An important criticism of the effect of migration of medical professionals to the United States has been the loss of human capital to their respective nations, but never the ill-effect they have had on the nations they have emigrated to.

The 2015 Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates (ECFMG) reported that a quarter of practicing physicians in the United States are international medical graduates (IMGs) and a fifth of all residency applicants were IMGs.2 Measuring the impact of the IMGs who have come to America is difficult to quantify but can be assessed by countless anecdotes and success stories. Forty-two percent of researchers at the seven top cancer research centers in the United States are immigrants. This is impressive considering that only about a tenth of the United States population is foreign born. Twenty-eight American Nobel prize winners in Medicine since 1960 are immigrants and taking a broader view as seen in Figure 1, almost 28% of physicians and 22% of RNs in the United States are foreign born.3,4 That does not take into account those like myself, first generation children who chose to enter this field of work out of respect for what their parents had accomplished.

The American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), over the past 15 years, has had several Presidents who are American immigrants. One of them, Dr. Kalpalatha K. Guntupalli, President 2009-2010, I have met, and I was humbled by the experience. She is brilliant, kind, and modest and without her knowing, she has served as one of the role models for my career.

I applaud CHEST for standing with other member organizations to oppose the immigration hiatus (Letter to John F. Kelly, Secretary of Homeland Security. Feb 7, 2017). The medical organizations made four concrete proposals:

• Reinstate the Visa Interview Waiver Program, as the suspension of this program increases the risk for significant delays in new and renewal visa processing for trainees from any foreign country;

• Remove entry restrictions of physicians and medical students from the seven designated countries that have been approved for J-1, H-1B or F-1 visas;

• Allow affected physicians to obtain travel visas to visit the United States for medical conferences, as well as other medical and research related events; and

• Prioritize the admission of refugees with urgent medical needs who had already been checked and approved for entry prior to the executive order.

These recommendations were good but not broad enough. The decision to bar immigration for any period of time, from any country, is an affront to the American dream with long-lasting consequences, most importantly, the loss of health-care services to the American populace. My Congressman knows how I feel about this, does yours?

1. Fivethirtyeight.com/features/trumps-new-travel-ban-could-affect-doctors-especially-in-the-rust-belt-and-appalachia/.Accessed July 18, 2017.

2. Masri A, Senussi MH. Trump’s executive order on immigration—detrimental effects on medical training and health care. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(19): e39.

3. http://www.immigrationresearch-info.org/report/immigrant-learning-center-inc/immigrants-health-care-keeping-americans-healthy-through-care-a.Accessed July 27, 2017.

4. http://www.nfap.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/International-Educator.May-June-2015.pdf.Accessed July 27, 2017 (not available on Safari).

Letter to CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends

Dear CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends:

The Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS) is an organization comprised of the world’s leading international professional respiratory societies presenting a unifying voice to improve lung health globally. Its members are: the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR), Asociación Latino Americana De Tórax (ALAT), European Respiratory Society (ERS), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union), the Pan African Thoracic Society (PATS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). FIRS has more than 70,000 professional members; the physicians and patients they serve magnify our efforts, allowing FIRS to speak for lung health on a global scale.

FIRS is working with the World Health Organization and the United Nations to make sure lung health is represented in national health agendas. FIRS’ position paper on electronic nicotine delivery systems was presented at a side-event at the United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHL) in New York in 2014 and is now a world standard. At the recent World Health Assembly meeting (May 2017) in Geneva, FIRS launched its Global Impact of Lung Disease report that called for a global clean air standard, strong anti-tobacco laws, and better health care for patients with respiratory disease.

FIRS will be reviewing the new WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines and will help promote them globally through advocacy and messaging, as well as by providing air quality expertise. FIRS will be involved at the Coimbra meeting (Sept 26-29) on improving the urban environment, the Montevideo UN High-Level (UNHL) meeting on chronic disease (Oct 18-20), and the UN Ministerial Meeting in Moscow on tuberculosis, and it is preparing for the 2018 UNHL meetings on antibiotic drug resistance, tuberculosis, and chronic diseases.

At the World Health Assembly, FIRS proclaimed September 25 as World Lung Day and hopes to use this as a rallying point for advocacy related to respiratory health or air quality. Lung Disease is the only major chronic disease that does not have a World Day. FIRS produced a Charter for Lung Health (www.firsnet.org/publications/charter) and hopes to have 100,000 persons sign on to it. FIRS also seeks to have lung-health organizations sign on and develop activities that can be carried out to celebrate lung health. Uruguay was the first country to sign the charter. The logos of the organizations who have signed the charter are on the FIRS website at firsnet.org. Activities being planned include editorials, newsletters, and letters-to-the-editor articles, legislative proclamations, social media exposure, and free spirometry, smoking cessation guidance, and carbon monoxide testing, but FIRS is looking for many more ways to celebrate healthy lungs on September 25 and many more partners!

Sixty-five million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 3 million die of it each year, making it the third leading cause of death worldwide; 10 million people develop tuberculosis and 1.4 million die of it each year, making it the most common deadly infectious disease; 1.6 million people die of lung cancer each year, making it the most deadly cancer; 334 million people suffer from asthma, making it the most common chronic disease of childhood; pneumonia kills millions of people each year, making it a leading cause of death in the very young and very old. At least 2 billion people are exposed to toxic indoor smoke; 1 billion inhale polluted outdoor air; and 1 billion are exposed to tobacco smoke, and the tragedy is that many conditions are getting worse. We cannot sit still and allow this to happen.

FIRS proposes a multipronged campaign to combat lung disease to bring together all people concerned with lung health. It starts with naming September 25 World Lung Day and calling on respiratory health organizations to pledge to improve lung health and help identify ways to celebrate this day.

Please sign up, and share this call for action with your professional, advocacy, and social networks, and those of your friends and families. Please do your part as global citizens to improve lung health. To do so, organizations should indicate they wish to sign on and send their logo to Betty Sax, FIRS Secretariat, betty.sax@ersnet.org. Organizations should also encourage individuals to sign on and show that they are committed to increasing awareness and action to promote global lung health.

Thank you.

Gerard Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

CHEST President

Darcy Marciniuk, MD, FCCP

CHEST FIRS Liaison

Dear CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends:

The Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS) is an organization comprised of the world’s leading international professional respiratory societies presenting a unifying voice to improve lung health globally. Its members are: the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR), Asociación Latino Americana De Tórax (ALAT), European Respiratory Society (ERS), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union), the Pan African Thoracic Society (PATS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). FIRS has more than 70,000 professional members; the physicians and patients they serve magnify our efforts, allowing FIRS to speak for lung health on a global scale.

FIRS is working with the World Health Organization and the United Nations to make sure lung health is represented in national health agendas. FIRS’ position paper on electronic nicotine delivery systems was presented at a side-event at the United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHL) in New York in 2014 and is now a world standard. At the recent World Health Assembly meeting (May 2017) in Geneva, FIRS launched its Global Impact of Lung Disease report that called for a global clean air standard, strong anti-tobacco laws, and better health care for patients with respiratory disease.

FIRS will be reviewing the new WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines and will help promote them globally through advocacy and messaging, as well as by providing air quality expertise. FIRS will be involved at the Coimbra meeting (Sept 26-29) on improving the urban environment, the Montevideo UN High-Level (UNHL) meeting on chronic disease (Oct 18-20), and the UN Ministerial Meeting in Moscow on tuberculosis, and it is preparing for the 2018 UNHL meetings on antibiotic drug resistance, tuberculosis, and chronic diseases.

At the World Health Assembly, FIRS proclaimed September 25 as World Lung Day and hopes to use this as a rallying point for advocacy related to respiratory health or air quality. Lung Disease is the only major chronic disease that does not have a World Day. FIRS produced a Charter for Lung Health (www.firsnet.org/publications/charter) and hopes to have 100,000 persons sign on to it. FIRS also seeks to have lung-health organizations sign on and develop activities that can be carried out to celebrate lung health. Uruguay was the first country to sign the charter. The logos of the organizations who have signed the charter are on the FIRS website at firsnet.org. Activities being planned include editorials, newsletters, and letters-to-the-editor articles, legislative proclamations, social media exposure, and free spirometry, smoking cessation guidance, and carbon monoxide testing, but FIRS is looking for many more ways to celebrate healthy lungs on September 25 and many more partners!

Sixty-five million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 3 million die of it each year, making it the third leading cause of death worldwide; 10 million people develop tuberculosis and 1.4 million die of it each year, making it the most common deadly infectious disease; 1.6 million people die of lung cancer each year, making it the most deadly cancer; 334 million people suffer from asthma, making it the most common chronic disease of childhood; pneumonia kills millions of people each year, making it a leading cause of death in the very young and very old. At least 2 billion people are exposed to toxic indoor smoke; 1 billion inhale polluted outdoor air; and 1 billion are exposed to tobacco smoke, and the tragedy is that many conditions are getting worse. We cannot sit still and allow this to happen.

FIRS proposes a multipronged campaign to combat lung disease to bring together all people concerned with lung health. It starts with naming September 25 World Lung Day and calling on respiratory health organizations to pledge to improve lung health and help identify ways to celebrate this day.

Please sign up, and share this call for action with your professional, advocacy, and social networks, and those of your friends and families. Please do your part as global citizens to improve lung health. To do so, organizations should indicate they wish to sign on and send their logo to Betty Sax, FIRS Secretariat, betty.sax@ersnet.org. Organizations should also encourage individuals to sign on and show that they are committed to increasing awareness and action to promote global lung health.

Thank you.

Gerard Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

CHEST President

Darcy Marciniuk, MD, FCCP

CHEST FIRS Liaison

Dear CHEST Leaders, Members, and Friends:

The Forum of International Respiratory Societies (FIRS) is an organization comprised of the world’s leading international professional respiratory societies presenting a unifying voice to improve lung health globally. Its members are: the American College of Chest Physicians (CHEST), American Thoracic Society (ATS), Asian Pacific Society of Respirology (APSR), Asociación Latino Americana De Tórax (ALAT), European Respiratory Society (ERS), International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Diseases (The Union), the Pan African Thoracic Society (PATS), the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD), and the Global Initiative for Asthma (GINA). FIRS has more than 70,000 professional members; the physicians and patients they serve magnify our efforts, allowing FIRS to speak for lung health on a global scale.

FIRS is working with the World Health Organization and the United Nations to make sure lung health is represented in national health agendas. FIRS’ position paper on electronic nicotine delivery systems was presented at a side-event at the United Nations High-Level Meeting (UNHL) in New York in 2014 and is now a world standard. At the recent World Health Assembly meeting (May 2017) in Geneva, FIRS launched its Global Impact of Lung Disease report that called for a global clean air standard, strong anti-tobacco laws, and better health care for patients with respiratory disease.

FIRS will be reviewing the new WHO Global Air Quality Guidelines and will help promote them globally through advocacy and messaging, as well as by providing air quality expertise. FIRS will be involved at the Coimbra meeting (Sept 26-29) on improving the urban environment, the Montevideo UN High-Level (UNHL) meeting on chronic disease (Oct 18-20), and the UN Ministerial Meeting in Moscow on tuberculosis, and it is preparing for the 2018 UNHL meetings on antibiotic drug resistance, tuberculosis, and chronic diseases.

At the World Health Assembly, FIRS proclaimed September 25 as World Lung Day and hopes to use this as a rallying point for advocacy related to respiratory health or air quality. Lung Disease is the only major chronic disease that does not have a World Day. FIRS produced a Charter for Lung Health (www.firsnet.org/publications/charter) and hopes to have 100,000 persons sign on to it. FIRS also seeks to have lung-health organizations sign on and develop activities that can be carried out to celebrate lung health. Uruguay was the first country to sign the charter. The logos of the organizations who have signed the charter are on the FIRS website at firsnet.org. Activities being planned include editorials, newsletters, and letters-to-the-editor articles, legislative proclamations, social media exposure, and free spirometry, smoking cessation guidance, and carbon monoxide testing, but FIRS is looking for many more ways to celebrate healthy lungs on September 25 and many more partners!

Sixty-five million people suffer from chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and 3 million die of it each year, making it the third leading cause of death worldwide; 10 million people develop tuberculosis and 1.4 million die of it each year, making it the most common deadly infectious disease; 1.6 million people die of lung cancer each year, making it the most deadly cancer; 334 million people suffer from asthma, making it the most common chronic disease of childhood; pneumonia kills millions of people each year, making it a leading cause of death in the very young and very old. At least 2 billion people are exposed to toxic indoor smoke; 1 billion inhale polluted outdoor air; and 1 billion are exposed to tobacco smoke, and the tragedy is that many conditions are getting worse. We cannot sit still and allow this to happen.

FIRS proposes a multipronged campaign to combat lung disease to bring together all people concerned with lung health. It starts with naming September 25 World Lung Day and calling on respiratory health organizations to pledge to improve lung health and help identify ways to celebrate this day.

Please sign up, and share this call for action with your professional, advocacy, and social networks, and those of your friends and families. Please do your part as global citizens to improve lung health. To do so, organizations should indicate they wish to sign on and send their logo to Betty Sax, FIRS Secretariat, betty.sax@ersnet.org. Organizations should also encourage individuals to sign on and show that they are committed to increasing awareness and action to promote global lung health.

Thank you.

Gerard Silvestri, MD, MS, FCCP

CHEST President

Darcy Marciniuk, MD, FCCP

CHEST FIRS Liaison

Critical Care Commentary Conscience Rights, Medical Training, and Critical Care Editor’s Note:

When I invited Dr. Wes Ely – the coauthor of a recent article regarding physician-assisted suicide – to write a Critical Care Commentary on said topic, an interesting thing happened: he declined and suggested that I invite a group of students from medical schools across the country to write the piece instead. The idea was brilliant, and the resulting piece was so insightful that the CHEST® journal editorial leadership suggested submission to the journal, and the accepted article will appear in the September issue. Out of that effort, the idea for the present piece was born. The result is an opportunity to hear the students’ voices, not only to stimulate discussion on conscientious objection in medicine but also to remind the ICU community that our learners have their own opinions and that through dialogues such as this, we might all learn from one another.

Lee Morrow, MD, FCCP

“No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.” – Thomas Jefferson

(Washington HA. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Biker, Thorne, & Co. 1854,; Vol 3:147.)

What is the proper role of conscience in medicine? A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Stahl & Emmanuel. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(14):1380) is the latest to address this question. It is often argued that physicians who cite conscience in refusing to perform requested procedures or treatments necessarily infringe upon patients’ rights. However, we feel that these concerns stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of what conscience is, why it ought to be respected as an indispensable part of medical judgment (Genuis & Lipp . Int J Family Med. 2013; Epub 2013 Dec 12), and how conscience is oriented toward the end goal of health, which we pursue in medicine.

By failing to define “conscience,” the crux of the argument against conscience rights is built on the basis of an implied diminution of conscience from an imperative moral judgment down to mere personal preference. If conscience represents only personal preference – if it is limited to a set of choices of the same moral equivalent as the selection of an ice cream flavor, with no need for technical expertise—then it would follow that a physician ought to simply comply with the patient’s decisions in any given medical situation. However, we know intuitively that this line of reasoning cannot hold, if followed to its conclusion. For example, if a patient presenting with symptoms of clear rhinorrhea and dry cough in December asks for an antibiotic, through this patient-sovereignty model, the physician surely ought to provide the prescription to honor the patient’s request. The patient would have every right to insist on the antibiotic, and the physician would be obliged to prescribe accordingly. We, as students, are trained, however, that it would be morally and professionally fitting, even obligatory, for the physician to refuse this request, precisely through exercise of his/her professional conscience.

If conscience, then, is not simply a subject of one’s personal preferences, how are we to properly understand it? Conscience is “a person’s moral sense of right and wrong, viewed as acting as a guide to one’s behavior” (Conscience. Oxford Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 2017). It exhibits the commitment to engage in a “self-conscience activity, integrating reason, emotion, and will, in self-committed decisions about right and wrong, good and evil” (Sulmasy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2008; 29(3):135). Whether or not a person intentionally seeks to form his/her conscience, it continues to be molded through the regular actions of daily life. The actions we perform – and those we omit – constantly shape our individual consciences. One’s conscience can indeed err due to emotional imbalance or faulty reasoning, but, even in these instances, it is essential to invest in the proper shaping of conscience in accordance with truth and goodness, rather than to reject the place of conscience altogether.

By attributing appropriate value to an individual’s conscience, we thereby recognize the centrality of conscience to identity and personal integrity. Consequently, we see that forcing an individual to impinge on his/her conscience through coercive means incidentally violates that person’s autonomy and dignity as a human being capable of moral decision-making.

In the practice of medicine, the free exercise of conscience is especially relevant. When patients and physicians meet to act in the pursuit of the patient’s health, they begin the process of conscience-mediated shared decision-making, rife with the potential for disagreement. Throughout this process, a physician should not violate a patient’s conscience rights by forcing medical treatment where it is unwanted, but neither should a patient violate a physician’s conscience rights by demanding a procedure or treatment that the physician cannot perform in good conscience. Moreover, to insert an external arbiter (eg, a professional society) to resolve the situation by means of contradiction of conscience would have the same violating effect on one or both parties.

One common debate as to the application of conscience in the setting of critical care focuses on the issue of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia (PAS/E) (Rhee J, et al. Chest. 2017;152[3]. Accepted for Sept 2017 publication). Those who would deny physicians the right to conscientiously object to PAS/E depict this as merely an issue of the physician’s personal preference. Given the distinction between preference and conscience, however, we recognize that much more is at play. For students and practitioners who hold that health signifies the “well-working of the organism as a whole,” (Kass L. Public Interest. 1975; 40(summer):11-42) and feel that the killing of a patient is an action that goes directly against the health of the patient, the obligation to participate in PAS/E represents not only a violation of our decision-making dignity, but also subverts the critical component of clinical judgment inherent to our profession. The conscientiously practicing doctor who follows what they believe to be their professional obligations, acting in accordance with the health of the patient, may reasonably conclude that PAS/E directly contradicts their obligations to pursue the best health interests of the patient. As such, their refusal to participate can hardly be deemed a simple personal preference, as the refusal is both reasoned and reasonable. Indeed, experts have concluded that regardless of the legality of PAS/E, physicians must be allowed to conscientiously object to participate (Goligher et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(2):149).

As medical students who have recently gone through the arduous medical school application process, we are particularly concerned with the claim that if one sees fit to exercise conscientious objection as a practitioner, they should leave medicine, or choose a field in medicine with few ethical dilemmas. To crassly exclude students from the pursuit of medicine on the basis of the shape of their conscience would be to unjustly discriminate by assigning different values to genuinely held beliefs. A direct consequence of this exclusion would be to decrease the diversity of thought, which is central to medical innovation and medical progress. History has taught us that the frontiers of medical advancement are most ardently pursued by those who think deeply and then dare to act creatively, seeking to bring to fruition what others deemed impossible. Without conscience rights, physicians are not free to think for themselves. We find it hard to believe that many physicians would feel comfortable jettisoning conscience in all instances where it may go against the wishes of their patients or the consensus opinion of the profession.

Furthermore, as medical students, we are acutely aware of the importance of conscientious objection due to the extant hierarchical nature of medical training. Evaluations are often performed by residents and physicians in places of authority, so students will readily subjugate everything from bodily needs to conscience in order to appease their attending physicians. Evidence indicates that medical students will even fail to object when they recognize medical errors performed by their superiors (Madigosky WS, et al. Acad Med. 2006; 81(1):94).

It is, therefore, crucial to the proper formation of medical students that our exercise of conscience be safeguarded during our training. A student who is free to exercise conscience is a student who is learning to think independently, as well as to shoulder the responsibility that comes as a consequence of free choices.

Ultimately, we must ask ourselves: how is the role of the physician altered if we choose to minimize the role of conscience in medicine? And do patients truly want physicians who forfeit their consciences even in matters of life and death? If we take the demands of those who dismiss conscience to their end – that only those willing to put their conscience aside should enter medicine – we would be left with practitioners whose group think training would stifle discussion between physicians and patients, and whose role would be reduced to simply acquiescing to any and all demands of the patient, even to their own detriment. Such a group of people, in our view, would fail to be physicians.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH (Dr. Dumitru); University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC (Mr. Frush); Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH (Mr. Radlicz); Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY (Mr. Allen); Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA (Mr. Brown); Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta School, Edmonton, AB, Canada (Mr. Bannon); Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Mr. Rhee).

When I invited Dr. Wes Ely – the coauthor of a recent article regarding physician-assisted suicide – to write a Critical Care Commentary on said topic, an interesting thing happened: he declined and suggested that I invite a group of students from medical schools across the country to write the piece instead. The idea was brilliant, and the resulting piece was so insightful that the CHEST® journal editorial leadership suggested submission to the journal, and the accepted article will appear in the September issue. Out of that effort, the idea for the present piece was born. The result is an opportunity to hear the students’ voices, not only to stimulate discussion on conscientious objection in medicine but also to remind the ICU community that our learners have their own opinions and that through dialogues such as this, we might all learn from one another.

Lee Morrow, MD, FCCP

“No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.” – Thomas Jefferson

(Washington HA. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Biker, Thorne, & Co. 1854,; Vol 3:147.)

What is the proper role of conscience in medicine? A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Stahl & Emmanuel. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(14):1380) is the latest to address this question. It is often argued that physicians who cite conscience in refusing to perform requested procedures or treatments necessarily infringe upon patients’ rights. However, we feel that these concerns stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of what conscience is, why it ought to be respected as an indispensable part of medical judgment (Genuis & Lipp . Int J Family Med. 2013; Epub 2013 Dec 12), and how conscience is oriented toward the end goal of health, which we pursue in medicine.

By failing to define “conscience,” the crux of the argument against conscience rights is built on the basis of an implied diminution of conscience from an imperative moral judgment down to mere personal preference. If conscience represents only personal preference – if it is limited to a set of choices of the same moral equivalent as the selection of an ice cream flavor, with no need for technical expertise—then it would follow that a physician ought to simply comply with the patient’s decisions in any given medical situation. However, we know intuitively that this line of reasoning cannot hold, if followed to its conclusion. For example, if a patient presenting with symptoms of clear rhinorrhea and dry cough in December asks for an antibiotic, through this patient-sovereignty model, the physician surely ought to provide the prescription to honor the patient’s request. The patient would have every right to insist on the antibiotic, and the physician would be obliged to prescribe accordingly. We, as students, are trained, however, that it would be morally and professionally fitting, even obligatory, for the physician to refuse this request, precisely through exercise of his/her professional conscience.

If conscience, then, is not simply a subject of one’s personal preferences, how are we to properly understand it? Conscience is “a person’s moral sense of right and wrong, viewed as acting as a guide to one’s behavior” (Conscience. Oxford Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 2017). It exhibits the commitment to engage in a “self-conscience activity, integrating reason, emotion, and will, in self-committed decisions about right and wrong, good and evil” (Sulmasy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2008; 29(3):135). Whether or not a person intentionally seeks to form his/her conscience, it continues to be molded through the regular actions of daily life. The actions we perform – and those we omit – constantly shape our individual consciences. One’s conscience can indeed err due to emotional imbalance or faulty reasoning, but, even in these instances, it is essential to invest in the proper shaping of conscience in accordance with truth and goodness, rather than to reject the place of conscience altogether.

By attributing appropriate value to an individual’s conscience, we thereby recognize the centrality of conscience to identity and personal integrity. Consequently, we see that forcing an individual to impinge on his/her conscience through coercive means incidentally violates that person’s autonomy and dignity as a human being capable of moral decision-making.

In the practice of medicine, the free exercise of conscience is especially relevant. When patients and physicians meet to act in the pursuit of the patient’s health, they begin the process of conscience-mediated shared decision-making, rife with the potential for disagreement. Throughout this process, a physician should not violate a patient’s conscience rights by forcing medical treatment where it is unwanted, but neither should a patient violate a physician’s conscience rights by demanding a procedure or treatment that the physician cannot perform in good conscience. Moreover, to insert an external arbiter (eg, a professional society) to resolve the situation by means of contradiction of conscience would have the same violating effect on one or both parties.

One common debate as to the application of conscience in the setting of critical care focuses on the issue of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia (PAS/E) (Rhee J, et al. Chest. 2017;152[3]. Accepted for Sept 2017 publication). Those who would deny physicians the right to conscientiously object to PAS/E depict this as merely an issue of the physician’s personal preference. Given the distinction between preference and conscience, however, we recognize that much more is at play. For students and practitioners who hold that health signifies the “well-working of the organism as a whole,” (Kass L. Public Interest. 1975; 40(summer):11-42) and feel that the killing of a patient is an action that goes directly against the health of the patient, the obligation to participate in PAS/E represents not only a violation of our decision-making dignity, but also subverts the critical component of clinical judgment inherent to our profession. The conscientiously practicing doctor who follows what they believe to be their professional obligations, acting in accordance with the health of the patient, may reasonably conclude that PAS/E directly contradicts their obligations to pursue the best health interests of the patient. As such, their refusal to participate can hardly be deemed a simple personal preference, as the refusal is both reasoned and reasonable. Indeed, experts have concluded that regardless of the legality of PAS/E, physicians must be allowed to conscientiously object to participate (Goligher et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(2):149).

As medical students who have recently gone through the arduous medical school application process, we are particularly concerned with the claim that if one sees fit to exercise conscientious objection as a practitioner, they should leave medicine, or choose a field in medicine with few ethical dilemmas. To crassly exclude students from the pursuit of medicine on the basis of the shape of their conscience would be to unjustly discriminate by assigning different values to genuinely held beliefs. A direct consequence of this exclusion would be to decrease the diversity of thought, which is central to medical innovation and medical progress. History has taught us that the frontiers of medical advancement are most ardently pursued by those who think deeply and then dare to act creatively, seeking to bring to fruition what others deemed impossible. Without conscience rights, physicians are not free to think for themselves. We find it hard to believe that many physicians would feel comfortable jettisoning conscience in all instances where it may go against the wishes of their patients or the consensus opinion of the profession.

Furthermore, as medical students, we are acutely aware of the importance of conscientious objection due to the extant hierarchical nature of medical training. Evaluations are often performed by residents and physicians in places of authority, so students will readily subjugate everything from bodily needs to conscience in order to appease their attending physicians. Evidence indicates that medical students will even fail to object when they recognize medical errors performed by their superiors (Madigosky WS, et al. Acad Med. 2006; 81(1):94).

It is, therefore, crucial to the proper formation of medical students that our exercise of conscience be safeguarded during our training. A student who is free to exercise conscience is a student who is learning to think independently, as well as to shoulder the responsibility that comes as a consequence of free choices.

Ultimately, we must ask ourselves: how is the role of the physician altered if we choose to minimize the role of conscience in medicine? And do patients truly want physicians who forfeit their consciences even in matters of life and death? If we take the demands of those who dismiss conscience to their end – that only those willing to put their conscience aside should enter medicine – we would be left with practitioners whose group think training would stifle discussion between physicians and patients, and whose role would be reduced to simply acquiescing to any and all demands of the patient, even to their own detriment. Such a group of people, in our view, would fail to be physicians.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH (Dr. Dumitru); University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC (Mr. Frush); Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH (Mr. Radlicz); Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY (Mr. Allen); Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA (Mr. Brown); Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta School, Edmonton, AB, Canada (Mr. Bannon); Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Mr. Rhee).

When I invited Dr. Wes Ely – the coauthor of a recent article regarding physician-assisted suicide – to write a Critical Care Commentary on said topic, an interesting thing happened: he declined and suggested that I invite a group of students from medical schools across the country to write the piece instead. The idea was brilliant, and the resulting piece was so insightful that the CHEST® journal editorial leadership suggested submission to the journal, and the accepted article will appear in the September issue. Out of that effort, the idea for the present piece was born. The result is an opportunity to hear the students’ voices, not only to stimulate discussion on conscientious objection in medicine but also to remind the ICU community that our learners have their own opinions and that through dialogues such as this, we might all learn from one another.

Lee Morrow, MD, FCCP

“No provision in our Constitution ought to be dearer to man than that which protects the rights of conscience against the enterprises of the civil authority.” – Thomas Jefferson

(Washington HA. The Writings of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Biker, Thorne, & Co. 1854,; Vol 3:147.)

What is the proper role of conscience in medicine? A recent article in the New England Journal of Medicine (Stahl & Emmanuel. N Engl J Med. 2017; 376(14):1380) is the latest to address this question. It is often argued that physicians who cite conscience in refusing to perform requested procedures or treatments necessarily infringe upon patients’ rights. However, we feel that these concerns stem from a fundamental misunderstanding of what conscience is, why it ought to be respected as an indispensable part of medical judgment (Genuis & Lipp . Int J Family Med. 2013; Epub 2013 Dec 12), and how conscience is oriented toward the end goal of health, which we pursue in medicine.

By failing to define “conscience,” the crux of the argument against conscience rights is built on the basis of an implied diminution of conscience from an imperative moral judgment down to mere personal preference. If conscience represents only personal preference – if it is limited to a set of choices of the same moral equivalent as the selection of an ice cream flavor, with no need for technical expertise—then it would follow that a physician ought to simply comply with the patient’s decisions in any given medical situation. However, we know intuitively that this line of reasoning cannot hold, if followed to its conclusion. For example, if a patient presenting with symptoms of clear rhinorrhea and dry cough in December asks for an antibiotic, through this patient-sovereignty model, the physician surely ought to provide the prescription to honor the patient’s request. The patient would have every right to insist on the antibiotic, and the physician would be obliged to prescribe accordingly. We, as students, are trained, however, that it would be morally and professionally fitting, even obligatory, for the physician to refuse this request, precisely through exercise of his/her professional conscience.

If conscience, then, is not simply a subject of one’s personal preferences, how are we to properly understand it? Conscience is “a person’s moral sense of right and wrong, viewed as acting as a guide to one’s behavior” (Conscience. Oxford Dictionary. Oxford, Oxford University Press. 2017). It exhibits the commitment to engage in a “self-conscience activity, integrating reason, emotion, and will, in self-committed decisions about right and wrong, good and evil” (Sulmasy. Theor Med Bioeth. 2008; 29(3):135). Whether or not a person intentionally seeks to form his/her conscience, it continues to be molded through the regular actions of daily life. The actions we perform – and those we omit – constantly shape our individual consciences. One’s conscience can indeed err due to emotional imbalance or faulty reasoning, but, even in these instances, it is essential to invest in the proper shaping of conscience in accordance with truth and goodness, rather than to reject the place of conscience altogether.

By attributing appropriate value to an individual’s conscience, we thereby recognize the centrality of conscience to identity and personal integrity. Consequently, we see that forcing an individual to impinge on his/her conscience through coercive means incidentally violates that person’s autonomy and dignity as a human being capable of moral decision-making.

In the practice of medicine, the free exercise of conscience is especially relevant. When patients and physicians meet to act in the pursuit of the patient’s health, they begin the process of conscience-mediated shared decision-making, rife with the potential for disagreement. Throughout this process, a physician should not violate a patient’s conscience rights by forcing medical treatment where it is unwanted, but neither should a patient violate a physician’s conscience rights by demanding a procedure or treatment that the physician cannot perform in good conscience. Moreover, to insert an external arbiter (eg, a professional society) to resolve the situation by means of contradiction of conscience would have the same violating effect on one or both parties.

One common debate as to the application of conscience in the setting of critical care focuses on the issue of physician-assisted suicide and euthanasia (PAS/E) (Rhee J, et al. Chest. 2017;152[3]. Accepted for Sept 2017 publication). Those who would deny physicians the right to conscientiously object to PAS/E depict this as merely an issue of the physician’s personal preference. Given the distinction between preference and conscience, however, we recognize that much more is at play. For students and practitioners who hold that health signifies the “well-working of the organism as a whole,” (Kass L. Public Interest. 1975; 40(summer):11-42) and feel that the killing of a patient is an action that goes directly against the health of the patient, the obligation to participate in PAS/E represents not only a violation of our decision-making dignity, but also subverts the critical component of clinical judgment inherent to our profession. The conscientiously practicing doctor who follows what they believe to be their professional obligations, acting in accordance with the health of the patient, may reasonably conclude that PAS/E directly contradicts their obligations to pursue the best health interests of the patient. As such, their refusal to participate can hardly be deemed a simple personal preference, as the refusal is both reasoned and reasonable. Indeed, experts have concluded that regardless of the legality of PAS/E, physicians must be allowed to conscientiously object to participate (Goligher et al. Crit Care Med. 2017; 45(2):149).

As medical students who have recently gone through the arduous medical school application process, we are particularly concerned with the claim that if one sees fit to exercise conscientious objection as a practitioner, they should leave medicine, or choose a field in medicine with few ethical dilemmas. To crassly exclude students from the pursuit of medicine on the basis of the shape of their conscience would be to unjustly discriminate by assigning different values to genuinely held beliefs. A direct consequence of this exclusion would be to decrease the diversity of thought, which is central to medical innovation and medical progress. History has taught us that the frontiers of medical advancement are most ardently pursued by those who think deeply and then dare to act creatively, seeking to bring to fruition what others deemed impossible. Without conscience rights, physicians are not free to think for themselves. We find it hard to believe that many physicians would feel comfortable jettisoning conscience in all instances where it may go against the wishes of their patients or the consensus opinion of the profession.

Furthermore, as medical students, we are acutely aware of the importance of conscientious objection due to the extant hierarchical nature of medical training. Evaluations are often performed by residents and physicians in places of authority, so students will readily subjugate everything from bodily needs to conscience in order to appease their attending physicians. Evidence indicates that medical students will even fail to object when they recognize medical errors performed by their superiors (Madigosky WS, et al. Acad Med. 2006; 81(1):94).

It is, therefore, crucial to the proper formation of medical students that our exercise of conscience be safeguarded during our training. A student who is free to exercise conscience is a student who is learning to think independently, as well as to shoulder the responsibility that comes as a consequence of free choices.

Ultimately, we must ask ourselves: how is the role of the physician altered if we choose to minimize the role of conscience in medicine? And do patients truly want physicians who forfeit their consciences even in matters of life and death? If we take the demands of those who dismiss conscience to their end – that only those willing to put their conscience aside should enter medicine – we would be left with practitioners whose group think training would stifle discussion between physicians and patients, and whose role would be reduced to simply acquiescing to any and all demands of the patient, even to their own detriment. Such a group of people, in our view, would fail to be physicians.

Author Affiliations: Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth, Hanover, NH (Dr. Dumitru); University of North Carolina School of Medicine, Chapel Hill, NC (Mr. Frush); Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine, Athens, OH (Mr. Radlicz); Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, New York, NY (Mr. Allen); Thomas Jefferson School of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA (Mr. Brown); Faculty of Medicine & Dentistry, University of Alberta School, Edmonton, AB, Canada (Mr. Bannon); Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY (Mr. Rhee).

FDA approves faster, pangenotypic cure for hep C virus

The first pangenotypic treatment for the hepatitis C virus, which also shaves 4 weeks off current regimens, has just been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.

Manufactured by AbbVie, glecaprevir/pibrentasvir (Mavyret) combines a nonstructural protein 3/4A protease inhibitor with a next-generation NS5A protein inhibitor for a once-daily, ribavirin-free treatment for adults with any of the major genotypes of chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection.

“This approval provides a shorter treatment duration for many patients, and also a treatment option for certain patients with genotype 1 infection, the most common HCV genotype in the United States, who were not successfully treated with other direct-acting antiviral treatments in the past,” Edward Cox, MD, director of the office of antimicrobial products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, Silver Spring, Md., said in a statement.

The 8-week regimen is indicated in patients without cirrhosis or with compensated cirrhosis, who are new to treatment, and those with limited treatment options, such as patients with chronic kidney disease, including those on dialysis. The intervention also is indicated in adults with HCV genotype 1 who have been treated with either of the drugs in the combination, but not both. Glecaprevir/pibrentasvir is not recommended in patients with moderate cirrhosis and is contraindicated in patients with severe cirrhosis and in those taking the drugs atazanavir and rifampin.

The safety and efficacy of the treatment were evaluated in approximately 2,300 adults with genotype 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 or 6 HCV infection without cirrhosis or with mild cirrhosis. In the clinical trials, between 92% and 100% of patients treated with glecaprevir/pibrentasvir for 8, 12, or 16 weeks had no detectable serum levels of the virus 12 weeks after finishing treatment. The most commonly reported adverse reactions were headache, fatigue, and nausea.

The FDA directs health care professionals to test all patients for current or prior hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection prior to starting this direct-acting antiviral drug combination since HBV reactivation has been reported in adult patients coinfected with both viruses who were undergoing or had completed treatment with HCV direct-acting antivirals and who were not receiving HBV antiviral therapy.