User login

Depression further boosts stroke risk in A-fib

NEW ORLEANS – Depression increases the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, Bruno B. Lima, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This novel finding from what’s believed to be the first prospective observational study to examine the association between depression and stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) raises the exciting possibility that systematic screening for depression and provision of effective antidepressant therapy in affected AF patients could reduce their risk of stroke. But clinical trials will be necessary to answer that question, noted Dr. Lima of the University of Pittsburgh.

He reported on 5,976 consecutive patients diagnosed with paroxysmal or persistent AF and placed on rhythm control medication at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and its affiliated clinics. Physician-diagnosed depression was present in 11.4% of the patients’ charts.

During a median follow-up of 39 months, 200 strokes occurred, including 35 in patients with depression. The incidence was 7.5% in AF patients with depression and 4.7% in those without diagnosed depression.

The depressed AF patients had more comorbid conditions, including significantly higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, cancer, and heart failure. They were also more likely to be smokers. But in a multivariate analysis controlling for comorbidities, age, gender, previous stroke, and use of anticoagulant therapy, the depressed AF patients remained at 45% greater risk of stroke compared with AF patients without diagnosed depression.

Strengths of this study include its large size and reasonable duration of follow-up. Limitations include the fact that investigators had to rely upon physician documentation of depressive episodes in the medical record, with no standardized measure of depression severity. Clinical trials addressing the issue of whether effective antidepressant therapy prevents strokes in depressed AF patients will need to use systematic screening for depression and serial measurements of depression severity, according to Dr. Lima.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – Depression increases the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, Bruno B. Lima, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This novel finding from what’s believed to be the first prospective observational study to examine the association between depression and stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) raises the exciting possibility that systematic screening for depression and provision of effective antidepressant therapy in affected AF patients could reduce their risk of stroke. But clinical trials will be necessary to answer that question, noted Dr. Lima of the University of Pittsburgh.

He reported on 5,976 consecutive patients diagnosed with paroxysmal or persistent AF and placed on rhythm control medication at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and its affiliated clinics. Physician-diagnosed depression was present in 11.4% of the patients’ charts.

During a median follow-up of 39 months, 200 strokes occurred, including 35 in patients with depression. The incidence was 7.5% in AF patients with depression and 4.7% in those without diagnosed depression.

The depressed AF patients had more comorbid conditions, including significantly higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, cancer, and heart failure. They were also more likely to be smokers. But in a multivariate analysis controlling for comorbidities, age, gender, previous stroke, and use of anticoagulant therapy, the depressed AF patients remained at 45% greater risk of stroke compared with AF patients without diagnosed depression.

Strengths of this study include its large size and reasonable duration of follow-up. Limitations include the fact that investigators had to rely upon physician documentation of depressive episodes in the medical record, with no standardized measure of depression severity. Clinical trials addressing the issue of whether effective antidepressant therapy prevents strokes in depressed AF patients will need to use systematic screening for depression and serial measurements of depression severity, according to Dr. Lima.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

NEW ORLEANS – Depression increases the risk of stroke in patients with atrial fibrillation, Bruno B. Lima, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

This novel finding from what’s believed to be the first prospective observational study to examine the association between depression and stroke risk in patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) raises the exciting possibility that systematic screening for depression and provision of effective antidepressant therapy in affected AF patients could reduce their risk of stroke. But clinical trials will be necessary to answer that question, noted Dr. Lima of the University of Pittsburgh.

He reported on 5,976 consecutive patients diagnosed with paroxysmal or persistent AF and placed on rhythm control medication at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center and its affiliated clinics. Physician-diagnosed depression was present in 11.4% of the patients’ charts.

During a median follow-up of 39 months, 200 strokes occurred, including 35 in patients with depression. The incidence was 7.5% in AF patients with depression and 4.7% in those without diagnosed depression.

The depressed AF patients had more comorbid conditions, including significantly higher rates of hypertension, diabetes, chronic kidney disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, obesity, cancer, and heart failure. They were also more likely to be smokers. But in a multivariate analysis controlling for comorbidities, age, gender, previous stroke, and use of anticoagulant therapy, the depressed AF patients remained at 45% greater risk of stroke compared with AF patients without diagnosed depression.

Strengths of this study include its large size and reasonable duration of follow-up. Limitations include the fact that investigators had to rely upon physician documentation of depressive episodes in the medical record, with no standardized measure of depression severity. Clinical trials addressing the issue of whether effective antidepressant therapy prevents strokes in depressed AF patients will need to use systematic screening for depression and serial measurements of depression severity, according to Dr. Lima.

He reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: After adjustment for numerous potential confounders, depressed patients with atrial fibrillation were 45% more likely to have a stroke during follow-up than were nondepressed patients with the arrhythmia.

Data source: A single-center prospective observational study of nearly 6,000 consecutive AF patients followed for a median of 39 months, 11.4% of whom carried a diagnosis of depression.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts of interest regarding this study, which was conducted free of commercial support.

VIDEO: ECG screen for cardiac disease in all youths is cost effective

NEW ORLEANS – Results of a first-of-its-kind nationwide U.K. cardiac disease screening program in the general population of teens and young adults indicate that incorporating a 12-lead ECG alongside history and physical examination not only increases the diagnostic yield for conditions predisposing to sudden cardiac death, but it’s actually cost saving, compared with screening by history and physical exam alone, Harshil Dhutia, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Current practice in the United Kingdom and most other western countries, including the United States, is to screen for cardiac disease in the general population of young people by history and physical exam alone. Only those with symptoms or a positive family history on the initial screen go on to a more comprehensive evaluation including an ECG. The ECG isn’t part of the initial screen primarily because of cost concerns. However, those concerns are based upon conjecture. The diagnostic and financial implications of routine screening by 12-lead ECG in the general population of young people hadn’t been examined prior to the nationwide U.K. screening program – and the results of the U.K. project indicate it’s time for a change in policy, according to Dr. Dhutia, a cardiology research fellow at St. George’s University in London.

The screening project, known as the Cardiac Risk in the Young Program, included 26,900 subjects aged 14-35 years without known cardiovascular disease who responded to public service announcements and voluntarily presented for screening at schools, community centers, and health centers across the U.K. during 2011-2013. The mean age of the subjects was 19.4 years, roughly two-thirds were male, and 90% were white. All screening was performed by cardiologists who followed the AHA protocol for history-taking, performed the physical exam, and followed the European Society of Cardiology 2010 recommendations for ECG interpretation. Individuals with a positive screen were referred to their local hospital for further investigation. Participants were prospectively followed for 2 years.

“This was the first study of comprehensive cardiovascular screening of young individuals outside competitive sport,” Dr. Dhutia noted.

Among the key findings: 3.5% of subjects were deemed by their screening cardiologist to have an abnormal history and/or physical exam warranting further investigation, 8.1% had an abnormal 12-lead ECG, and 0.5% had both. Overall, 11.7% of subjects underwent echocardiography to confirm or refute a diagnosis of cardiac disease, 1.7% underwent Holter monitoring, 1.7% had an exercise stress test, and 0.9% underwent cardiac MRI.

At 2 years of follow-up, 87 individuals, or 0.3% of the overall study cohort, had been diagnosed with a serious cardiac disease predisposing to sudden cardiac death.

“The vast majority of these individuals were asymptomatic and diagnosed on the basis of an ECG abnormality,” Dr. Dhutia observed.

Indeed, 72 of the 87 patients with serious cardiac disease were diagnosed on the basis on their abnormal ECG. This tool proved particularly helpful in identifying individuals with cardiomyopathies or congenital accessory pathways, such as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome or long QT syndrome. At 2 years of follow-up, 42 of these 72 patients were on disease-modifying therapies beyond lifestyle interventions, most commonly ablation procedures or antiarrhythmic medication.

The history and physical exam was useful in identifying young people with channelopathies or Marfan syndrome. Roughly half of individuals identified by history and physical exam as having serious cardiac disease were on antiarrhythmic medication – or, less commonly, pacemaker therapy – at 2 years follow-up.

The overall cost per individual screened using history, physical exam, and ECG amounted to $110 on the basis of U.K. National Health Service rates. The cost per serious cardiac condition identified was $33,927. In contrast, the average cost per serious cardiac diagnosis under the current U.K. protocol of screening youth by history and physical exam only is 67% greater, at $56,597.

“Inclusion of ECG to history and physical examination is associated with a significantly improved diagnostic yield and superior economic profile. These findings have the potential to influence health care policy and certainly suggest that the National Health Service framework in the United Kingdom is counterintuitive and may warrant revision,” he concluded.

Session moderator Nisha Parikh, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, asked if Dr. Dhutia and his coinvestigators had identified any characteristics associated with serious occult cardiac disease in adolescents and young adults that would permit a more refined, selective approach to screening.

Not in the general population of nearly 27,000 subjects in the U.K. study, he replied. Competitive athletes are a different story, though.

“In competitive athletes, certainly individuals who play stop/start sports such as basketball or football [soccer], appear to be at higher risk, especially those of Afro-Caribbean origin. The incidence of sudden cardiac death in Afro-Caribbean basketball players is 1 in 3,000,” according to Dr. Dhutia, who discussed his findings in a video interview.

He reported receiving a small research grant for his study from the Cardiac Risk in the Young Program, a U.K. charitable organization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Results of a first-of-its-kind nationwide U.K. cardiac disease screening program in the general population of teens and young adults indicate that incorporating a 12-lead ECG alongside history and physical examination not only increases the diagnostic yield for conditions predisposing to sudden cardiac death, but it’s actually cost saving, compared with screening by history and physical exam alone, Harshil Dhutia, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Current practice in the United Kingdom and most other western countries, including the United States, is to screen for cardiac disease in the general population of young people by history and physical exam alone. Only those with symptoms or a positive family history on the initial screen go on to a more comprehensive evaluation including an ECG. The ECG isn’t part of the initial screen primarily because of cost concerns. However, those concerns are based upon conjecture. The diagnostic and financial implications of routine screening by 12-lead ECG in the general population of young people hadn’t been examined prior to the nationwide U.K. screening program – and the results of the U.K. project indicate it’s time for a change in policy, according to Dr. Dhutia, a cardiology research fellow at St. George’s University in London.

The screening project, known as the Cardiac Risk in the Young Program, included 26,900 subjects aged 14-35 years without known cardiovascular disease who responded to public service announcements and voluntarily presented for screening at schools, community centers, and health centers across the U.K. during 2011-2013. The mean age of the subjects was 19.4 years, roughly two-thirds were male, and 90% were white. All screening was performed by cardiologists who followed the AHA protocol for history-taking, performed the physical exam, and followed the European Society of Cardiology 2010 recommendations for ECG interpretation. Individuals with a positive screen were referred to their local hospital for further investigation. Participants were prospectively followed for 2 years.

“This was the first study of comprehensive cardiovascular screening of young individuals outside competitive sport,” Dr. Dhutia noted.

Among the key findings: 3.5% of subjects were deemed by their screening cardiologist to have an abnormal history and/or physical exam warranting further investigation, 8.1% had an abnormal 12-lead ECG, and 0.5% had both. Overall, 11.7% of subjects underwent echocardiography to confirm or refute a diagnosis of cardiac disease, 1.7% underwent Holter monitoring, 1.7% had an exercise stress test, and 0.9% underwent cardiac MRI.

At 2 years of follow-up, 87 individuals, or 0.3% of the overall study cohort, had been diagnosed with a serious cardiac disease predisposing to sudden cardiac death.

“The vast majority of these individuals were asymptomatic and diagnosed on the basis of an ECG abnormality,” Dr. Dhutia observed.

Indeed, 72 of the 87 patients with serious cardiac disease were diagnosed on the basis on their abnormal ECG. This tool proved particularly helpful in identifying individuals with cardiomyopathies or congenital accessory pathways, such as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome or long QT syndrome. At 2 years of follow-up, 42 of these 72 patients were on disease-modifying therapies beyond lifestyle interventions, most commonly ablation procedures or antiarrhythmic medication.

The history and physical exam was useful in identifying young people with channelopathies or Marfan syndrome. Roughly half of individuals identified by history and physical exam as having serious cardiac disease were on antiarrhythmic medication – or, less commonly, pacemaker therapy – at 2 years follow-up.

The overall cost per individual screened using history, physical exam, and ECG amounted to $110 on the basis of U.K. National Health Service rates. The cost per serious cardiac condition identified was $33,927. In contrast, the average cost per serious cardiac diagnosis under the current U.K. protocol of screening youth by history and physical exam only is 67% greater, at $56,597.

“Inclusion of ECG to history and physical examination is associated with a significantly improved diagnostic yield and superior economic profile. These findings have the potential to influence health care policy and certainly suggest that the National Health Service framework in the United Kingdom is counterintuitive and may warrant revision,” he concluded.

Session moderator Nisha Parikh, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, asked if Dr. Dhutia and his coinvestigators had identified any characteristics associated with serious occult cardiac disease in adolescents and young adults that would permit a more refined, selective approach to screening.

Not in the general population of nearly 27,000 subjects in the U.K. study, he replied. Competitive athletes are a different story, though.

“In competitive athletes, certainly individuals who play stop/start sports such as basketball or football [soccer], appear to be at higher risk, especially those of Afro-Caribbean origin. The incidence of sudden cardiac death in Afro-Caribbean basketball players is 1 in 3,000,” according to Dr. Dhutia, who discussed his findings in a video interview.

He reported receiving a small research grant for his study from the Cardiac Risk in the Young Program, a U.K. charitable organization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

NEW ORLEANS – Results of a first-of-its-kind nationwide U.K. cardiac disease screening program in the general population of teens and young adults indicate that incorporating a 12-lead ECG alongside history and physical examination not only increases the diagnostic yield for conditions predisposing to sudden cardiac death, but it’s actually cost saving, compared with screening by history and physical exam alone, Harshil Dhutia, MD, said at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

Current practice in the United Kingdom and most other western countries, including the United States, is to screen for cardiac disease in the general population of young people by history and physical exam alone. Only those with symptoms or a positive family history on the initial screen go on to a more comprehensive evaluation including an ECG. The ECG isn’t part of the initial screen primarily because of cost concerns. However, those concerns are based upon conjecture. The diagnostic and financial implications of routine screening by 12-lead ECG in the general population of young people hadn’t been examined prior to the nationwide U.K. screening program – and the results of the U.K. project indicate it’s time for a change in policy, according to Dr. Dhutia, a cardiology research fellow at St. George’s University in London.

The screening project, known as the Cardiac Risk in the Young Program, included 26,900 subjects aged 14-35 years without known cardiovascular disease who responded to public service announcements and voluntarily presented for screening at schools, community centers, and health centers across the U.K. during 2011-2013. The mean age of the subjects was 19.4 years, roughly two-thirds were male, and 90% were white. All screening was performed by cardiologists who followed the AHA protocol for history-taking, performed the physical exam, and followed the European Society of Cardiology 2010 recommendations for ECG interpretation. Individuals with a positive screen were referred to their local hospital for further investigation. Participants were prospectively followed for 2 years.

“This was the first study of comprehensive cardiovascular screening of young individuals outside competitive sport,” Dr. Dhutia noted.

Among the key findings: 3.5% of subjects were deemed by their screening cardiologist to have an abnormal history and/or physical exam warranting further investigation, 8.1% had an abnormal 12-lead ECG, and 0.5% had both. Overall, 11.7% of subjects underwent echocardiography to confirm or refute a diagnosis of cardiac disease, 1.7% underwent Holter monitoring, 1.7% had an exercise stress test, and 0.9% underwent cardiac MRI.

At 2 years of follow-up, 87 individuals, or 0.3% of the overall study cohort, had been diagnosed with a serious cardiac disease predisposing to sudden cardiac death.

“The vast majority of these individuals were asymptomatic and diagnosed on the basis of an ECG abnormality,” Dr. Dhutia observed.

Indeed, 72 of the 87 patients with serious cardiac disease were diagnosed on the basis on their abnormal ECG. This tool proved particularly helpful in identifying individuals with cardiomyopathies or congenital accessory pathways, such as Wolff-Parkinson-White syndrome or long QT syndrome. At 2 years of follow-up, 42 of these 72 patients were on disease-modifying therapies beyond lifestyle interventions, most commonly ablation procedures or antiarrhythmic medication.

The history and physical exam was useful in identifying young people with channelopathies or Marfan syndrome. Roughly half of individuals identified by history and physical exam as having serious cardiac disease were on antiarrhythmic medication – or, less commonly, pacemaker therapy – at 2 years follow-up.

The overall cost per individual screened using history, physical exam, and ECG amounted to $110 on the basis of U.K. National Health Service rates. The cost per serious cardiac condition identified was $33,927. In contrast, the average cost per serious cardiac diagnosis under the current U.K. protocol of screening youth by history and physical exam only is 67% greater, at $56,597.

“Inclusion of ECG to history and physical examination is associated with a significantly improved diagnostic yield and superior economic profile. These findings have the potential to influence health care policy and certainly suggest that the National Health Service framework in the United Kingdom is counterintuitive and may warrant revision,” he concluded.

Session moderator Nisha Parikh, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco, asked if Dr. Dhutia and his coinvestigators had identified any characteristics associated with serious occult cardiac disease in adolescents and young adults that would permit a more refined, selective approach to screening.

Not in the general population of nearly 27,000 subjects in the U.K. study, he replied. Competitive athletes are a different story, though.

“In competitive athletes, certainly individuals who play stop/start sports such as basketball or football [soccer], appear to be at higher risk, especially those of Afro-Caribbean origin. The incidence of sudden cardiac death in Afro-Caribbean basketball players is 1 in 3,000,” according to Dr. Dhutia, who discussed his findings in a video interview.

He reported receiving a small research grant for his study from the Cardiac Risk in the Young Program, a U.K. charitable organization.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Key clinical point:

Major finding: The cost of identifying one case of serious cardiac disease predisposing to sudden cardiac death in young people was reduced by 40% when initial screening of the general population ages 14-35 years was conducted by history, physical examination, and 12-lead ECG, compared with no ECG.

Data source: A prospective observational study of nearly 27,000 young people ages 14-35 years in the general population across the United Kingdom who presented for cardiac screening conducted by cardiologists using history, physical examination, and a 12-lead ECG.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the Cardiac Risk in the Young Program, a U.K. charitable organization.

Daratumumab combo holds up across POLLUX myeloma subgroups

SAN DIEGO – Adding daratumumab (D) to lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) significantly improved outcomes in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma, even when patients had previously received lenalidomide, were refractory to bortezomib, or had high-risk tumor cytogenetics, based on updated analyses from the multicenter, randomized, phase III, open-label POLLUX trial.

The findings underscore the “significant benefit of combining daratumumab with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma,” said lead investigator Philippe Moreau, MD, of University Hospital Hotel-Dieu in Nantes, France.

Among a large subgroup of 524 POLLUX patients who had received one to three prior lines of therapy, estimated median progression-free survival (PFS) has not been reached in the daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (DRd) arm, versus 18.4 months in the lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) arm (hazard ratio, 0.36; 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.49; P less than .0001), Dr. Moreau said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

That means adding daratumumab to Rd led to a 64% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death among patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, he noted. Fully 77% of DRd patients were alive without having progressed at 18 months, and responses “continued to deepen in the DRd group with longer follow-up,” he added.

Additional analyses supported the use of DRd in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, “irrespective of prior lenalidomide treatment or bortezomib refractoriness,” Dr. Moreau continued. He reported that DRd significantly improved PFS over Rd alone not only among 445 lenalidomide-naive patients (HR, 0.37; P less than .0001), but also among 91 lenalidomide-exposed patients (HR, 0.45; P = .04), 140 patients who were refractory to their most recent line of therapy (HR, 0.45; P = .001), and 99 bortezomib- refractory patients (HR 0.51; P = .02).

Daratumumab (Darzalex), a human CD38 IgG1k monoclonal antibody, was first approved as monotherapy for multiple myeloma in patients who had received at least three prior lines of therapy or had double-refractory disease. In 2016, results from the twin POLLUX and CASTOR studies won daratumumab a Food and Drug Administration breakthrough designation status for use with Rd in patients who had received at least one prior line.

The POLLUX trial included 569 patients with multiple myeloma who had received a median of 1 and up to 11 prior lines of therapy. Patients were randomized to either Rd alone or to Rd plus intravenous daratumumab (16 mg/kg) once a week during the first two 28-day treatment cycles, every 2 weeks during cycles 3-6, and once only on day 1 of subsequent cycles.

POLLUX patients were fairly heavily pretreated, Dr. Moreau noted. Thirteen percent had received three prior lines of therapy, 86% had received a proteasome inhibitor, 18% had received lenalidomide, 21% were refractory to bortezomib, and 28% were refractory to their most recent line of therapy.

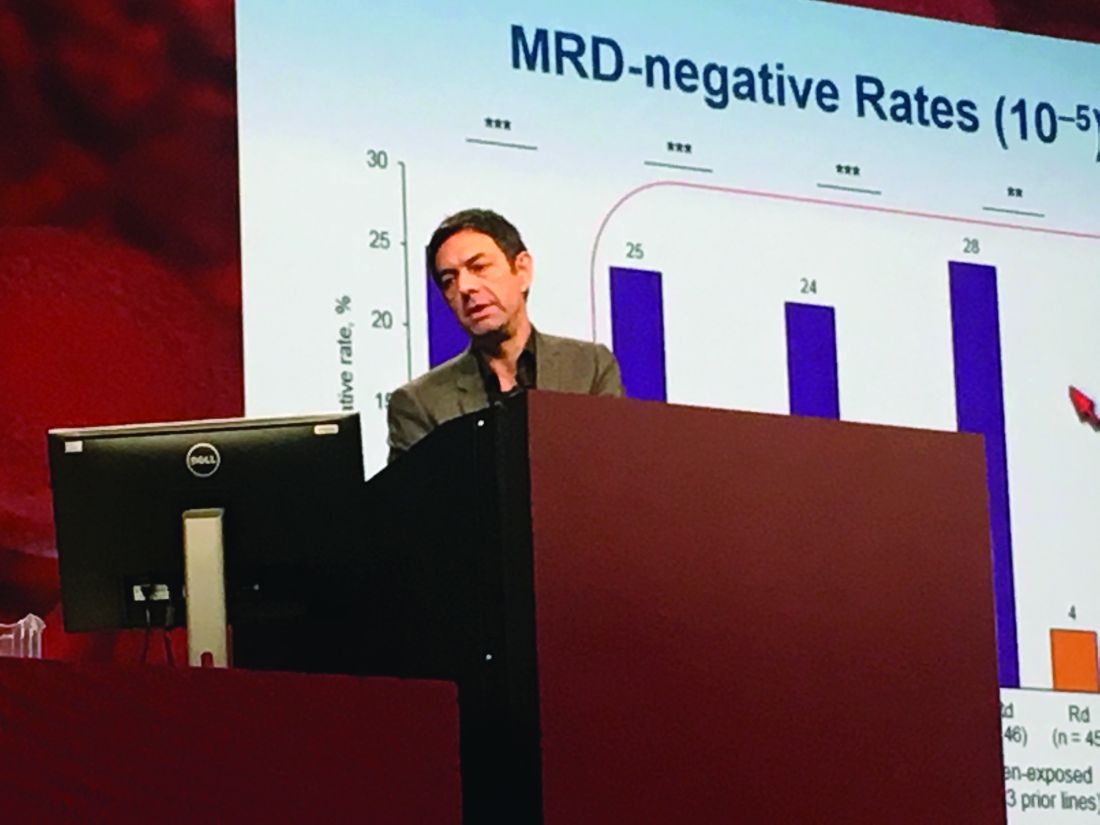

Researchers performed “stringent, unbiased” assessments of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity not only when a complete response was suspected, but also 3 and 6 months later, Dr. Moreau said. He emphasized that rates of MRD negativity in lenalidomide-exposed, bortezomib-refractory subgroups in POLLUX almost exactly matched those in the intent-to-treat population (25% on DRd vs. 6% on Rd; P less than .0001).

A total of 17% of DRd patients and 25% of Rd patients had high-risk cytogenetic profiles, and DRd performed well in these individuals, Dr. Moreau reported. Fully 85% of all evaluable high-risk patients had at least a partial response to DRd, and 33% had a complete response, versus only 67% and 6% of high-risk Rd patients, respectively. Among patients with standard-risk cytogenetics, rates of best overall response were 95% on DRd and 82% on Rd, and rates of complete response were 52% on DRd and 24% on Rd.

POLLUX yielded no new safety signals for DRd, Dr. Moreau said. Rates of primary and secondary malignancies were less than 2%. Neutropenia, the most common adverse effect, was managed by interrupting treatment, reducing the dose of lenalidomide, and administering growth factor.

Janssen Research & Development funded the study. Dr. Moreau had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Adding daratumumab (D) to lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) significantly improved outcomes in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma, even when patients had previously received lenalidomide, were refractory to bortezomib, or had high-risk tumor cytogenetics, based on updated analyses from the multicenter, randomized, phase III, open-label POLLUX trial.

The findings underscore the “significant benefit of combining daratumumab with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma,” said lead investigator Philippe Moreau, MD, of University Hospital Hotel-Dieu in Nantes, France.

Among a large subgroup of 524 POLLUX patients who had received one to three prior lines of therapy, estimated median progression-free survival (PFS) has not been reached in the daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (DRd) arm, versus 18.4 months in the lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) arm (hazard ratio, 0.36; 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.49; P less than .0001), Dr. Moreau said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

That means adding daratumumab to Rd led to a 64% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death among patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, he noted. Fully 77% of DRd patients were alive without having progressed at 18 months, and responses “continued to deepen in the DRd group with longer follow-up,” he added.

Additional analyses supported the use of DRd in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, “irrespective of prior lenalidomide treatment or bortezomib refractoriness,” Dr. Moreau continued. He reported that DRd significantly improved PFS over Rd alone not only among 445 lenalidomide-naive patients (HR, 0.37; P less than .0001), but also among 91 lenalidomide-exposed patients (HR, 0.45; P = .04), 140 patients who were refractory to their most recent line of therapy (HR, 0.45; P = .001), and 99 bortezomib- refractory patients (HR 0.51; P = .02).

Daratumumab (Darzalex), a human CD38 IgG1k monoclonal antibody, was first approved as monotherapy for multiple myeloma in patients who had received at least three prior lines of therapy or had double-refractory disease. In 2016, results from the twin POLLUX and CASTOR studies won daratumumab a Food and Drug Administration breakthrough designation status for use with Rd in patients who had received at least one prior line.

The POLLUX trial included 569 patients with multiple myeloma who had received a median of 1 and up to 11 prior lines of therapy. Patients were randomized to either Rd alone or to Rd plus intravenous daratumumab (16 mg/kg) once a week during the first two 28-day treatment cycles, every 2 weeks during cycles 3-6, and once only on day 1 of subsequent cycles.

POLLUX patients were fairly heavily pretreated, Dr. Moreau noted. Thirteen percent had received three prior lines of therapy, 86% had received a proteasome inhibitor, 18% had received lenalidomide, 21% were refractory to bortezomib, and 28% were refractory to their most recent line of therapy.

Researchers performed “stringent, unbiased” assessments of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity not only when a complete response was suspected, but also 3 and 6 months later, Dr. Moreau said. He emphasized that rates of MRD negativity in lenalidomide-exposed, bortezomib-refractory subgroups in POLLUX almost exactly matched those in the intent-to-treat population (25% on DRd vs. 6% on Rd; P less than .0001).

A total of 17% of DRd patients and 25% of Rd patients had high-risk cytogenetic profiles, and DRd performed well in these individuals, Dr. Moreau reported. Fully 85% of all evaluable high-risk patients had at least a partial response to DRd, and 33% had a complete response, versus only 67% and 6% of high-risk Rd patients, respectively. Among patients with standard-risk cytogenetics, rates of best overall response were 95% on DRd and 82% on Rd, and rates of complete response were 52% on DRd and 24% on Rd.

POLLUX yielded no new safety signals for DRd, Dr. Moreau said. Rates of primary and secondary malignancies were less than 2%. Neutropenia, the most common adverse effect, was managed by interrupting treatment, reducing the dose of lenalidomide, and administering growth factor.

Janssen Research & Development funded the study. Dr. Moreau had no relevant financial disclosures.

SAN DIEGO – Adding daratumumab (D) to lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) significantly improved outcomes in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma, even when patients had previously received lenalidomide, were refractory to bortezomib, or had high-risk tumor cytogenetics, based on updated analyses from the multicenter, randomized, phase III, open-label POLLUX trial.

The findings underscore the “significant benefit of combining daratumumab with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma,” said lead investigator Philippe Moreau, MD, of University Hospital Hotel-Dieu in Nantes, France.

Among a large subgroup of 524 POLLUX patients who had received one to three prior lines of therapy, estimated median progression-free survival (PFS) has not been reached in the daratumumab, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (DRd) arm, versus 18.4 months in the lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) arm (hazard ratio, 0.36; 95% CI: 0.26 to 0.49; P less than .0001), Dr. Moreau said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

That means adding daratumumab to Rd led to a 64% reduction in the risk of disease progression or death among patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, he noted. Fully 77% of DRd patients were alive without having progressed at 18 months, and responses “continued to deepen in the DRd group with longer follow-up,” he added.

Additional analyses supported the use of DRd in relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma, “irrespective of prior lenalidomide treatment or bortezomib refractoriness,” Dr. Moreau continued. He reported that DRd significantly improved PFS over Rd alone not only among 445 lenalidomide-naive patients (HR, 0.37; P less than .0001), but also among 91 lenalidomide-exposed patients (HR, 0.45; P = .04), 140 patients who were refractory to their most recent line of therapy (HR, 0.45; P = .001), and 99 bortezomib- refractory patients (HR 0.51; P = .02).

Daratumumab (Darzalex), a human CD38 IgG1k monoclonal antibody, was first approved as monotherapy for multiple myeloma in patients who had received at least three prior lines of therapy or had double-refractory disease. In 2016, results from the twin POLLUX and CASTOR studies won daratumumab a Food and Drug Administration breakthrough designation status for use with Rd in patients who had received at least one prior line.

The POLLUX trial included 569 patients with multiple myeloma who had received a median of 1 and up to 11 prior lines of therapy. Patients were randomized to either Rd alone or to Rd plus intravenous daratumumab (16 mg/kg) once a week during the first two 28-day treatment cycles, every 2 weeks during cycles 3-6, and once only on day 1 of subsequent cycles.

POLLUX patients were fairly heavily pretreated, Dr. Moreau noted. Thirteen percent had received three prior lines of therapy, 86% had received a proteasome inhibitor, 18% had received lenalidomide, 21% were refractory to bortezomib, and 28% were refractory to their most recent line of therapy.

Researchers performed “stringent, unbiased” assessments of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity not only when a complete response was suspected, but also 3 and 6 months later, Dr. Moreau said. He emphasized that rates of MRD negativity in lenalidomide-exposed, bortezomib-refractory subgroups in POLLUX almost exactly matched those in the intent-to-treat population (25% on DRd vs. 6% on Rd; P less than .0001).

A total of 17% of DRd patients and 25% of Rd patients had high-risk cytogenetic profiles, and DRd performed well in these individuals, Dr. Moreau reported. Fully 85% of all evaluable high-risk patients had at least a partial response to DRd, and 33% had a complete response, versus only 67% and 6% of high-risk Rd patients, respectively. Among patients with standard-risk cytogenetics, rates of best overall response were 95% on DRd and 82% on Rd, and rates of complete response were 52% on DRd and 24% on Rd.

POLLUX yielded no new safety signals for DRd, Dr. Moreau said. Rates of primary and secondary malignancies were less than 2%. Neutropenia, the most common adverse effect, was managed by interrupting treatment, reducing the dose of lenalidomide, and administering growth factor.

Janssen Research & Development funded the study. Dr. Moreau had no relevant financial disclosures.

AT ASH 2016

Key clinical point: Adding daratumumab (D) to lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) significantly improved outcomes in patients with relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma, regardless of factors such as bortezomib refractoriness, lenalidomide exposure, or high-risk tumor cytogenetics.

Major finding: DRd significantly improved PFS over Rd not only among 445 lenalidomide-naive patients (HR, 0.37; P less than .0001), but also among 91 lenalidomide-exposed patients (HR, 0.45; P = .04), 140 patients who were refractory to their most recent line of therapy (HR, 0.45; P = .001), and 99 bortezomib-refractory patients (HR 0.51; P = .02).

Data source: POLLUX, a multicenter, randomized, phase III, open-label trial of 569 patients with multiple myeloma who had received one or more previous lines of therapy.

Disclosures: Janssen Research & Development funded the study. Dr. Moreau had no relevant financial disclosures.

Project aims to improve understanding of AED prescribing trends

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

HOUSTON – A significant proportion of epilepsy patients in the United States are not taking newer antiepileptic medications, results from a pilot study suggested.

The finding comes from the Connectors Project, a collaboration between the Epilepsy Foundation and UCB Pharma that is intended to improve epilepsy patient care in underserved areas of the United States. One aim of the project is to evaluate the current status and geographic variations of antiepileptic drug (AED) use to identify regions where epilepsy care might be improved.

Dr. Sirven, who chairs the department of neurology at the Mayo Clinic, Scottsdale, Ariz., reported that about 2.5 million epilepsy patients were identified from 2013 to 2015. Of these, 237,347 patients were newly treated with AEDs. As expected, states with the highest population had the highest volume of epilepsy patients prescribed an AED, including California (8.2%), Texas (7.7%), Florida (6.9%), and New York (6.5%). Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%). At the same time, states with the highest total proportion of newer AED use and lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Hawaii (77.7% vs. 17.6%, respectively), Montana (70.4% vs. 7.9%), Alaska (67.8% vs. 8.4%), Delaware (66.9% vs. 10.3%), and Colorado (66.5% vs. 11.8%).

When the researchers limited the analysis to epilepsy patients who were newly treated with AEDs, they found that Hawaii and Alaska had the highest percentage of phenytoin use, compared with all other states (39.1% and 38.8%). States with the lowest proportion of phenytoin use were Vermont (2.4%), Delaware (2.6%), and Montana (3.7%). North Dakota had the highest use of older AEDs (29.6%), followed by Washington, D.C. (27.9%), Vermont (26.9%), and Maine (25.8%). Meanwhile, Idaho had the highest proportion of patients treated with newer AEDs (86.1%), followed by Montana (84.4%), Delaware (82.2%), Rhode Island (82%), Wyoming (81.1%), and Minnesota (80.3%).

“One question we haven’t answered is: ‘What are the long-term implications of initial AED selection?’ ” coauthor Jesse Fishman, PharmD, of UCB Pharma said at the meeting. “Initially, the selection may be from a hospital or an ER physician. Maybe there’s some relationship between the ER physician for seeing the seizure patient, they get on a medication, and then it’s carried over for some time and they don’t see a specialist. We’re looking at how referrals are tied to this. It may not be the neurologists who are selecting these initial drugs and the patients are staying on them.”

The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Regions with the highest total proportion of phenytoin use and the lowest proportion of newer AED use were Washington, D.C. (24.7% vs. 58.1%, respectively), Mississippi (24.4% vs. 53.1%), Louisiana (20.7% vs. 57.6%), and Arkansas (20.3% vs. 56.2%).

Data source: A pilot study that evaluated medical records from about 2.5 million epilepsy patients from 2013 to 2015.

Disclosures: The study was sponsored by UCB Pharma. Dr. Sirven disclosed that he has served as a consultant for UCB Pharma, Acorda Therapeutics, and Upsher-Smith. Dr. Fishman is employed by UCB Pharma.

Webcast: Emergency contraception: How to choose the right one for your patient

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Contraceptive considerations for women with headache and migraine

- Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism

- Oral contraceptives and breast cancer: What’s the risk?

- Factors that contribute to overall contraceptive efficacy and risks

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resources for your practice:

- United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016

- United States Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2010

- Summary Chart of US Medical Eligibility for Contraceptive Use

- Book recommendation: Allen RH, Cwiak CA, eds. Contraception for the medically challenging patient. New York, New York: Springer New York; 2014.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Contraceptive considerations for women with headache and migraine

- Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism

- Oral contraceptives and breast cancer: What’s the risk?

- Factors that contribute to overall contraceptive efficacy and risks

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resources for your practice:

- United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016

- United States Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2010

- Summary Chart of US Medical Eligibility for Contraceptive Use

- Book recommendation: Allen RH, Cwiak CA, eds. Contraception for the medically challenging patient. New York, New York: Springer New York; 2014.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Access Dr. Burkman's Webcasts on contraception:

- Contraceptive considerations for women with headache and migraine

- Hormonal contraception and risk of venous thromboembolism

- Oral contraceptives and breast cancer: What’s the risk?

- Factors that contribute to overall contraceptive efficacy and risks

- Obesity and contraceptive efficacy and risks

- How to use the CDC's online tools to manage complex cases in contraception

Helpful resources for your practice:

- United States Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use, 2016

- United States Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC) for Contraceptive Use, 2010

- Summary Chart of US Medical Eligibility for Contraceptive Use

- Book recommendation: Allen RH, Cwiak CA, eds. Contraception for the medically challenging patient. New York, New York: Springer New York; 2014.

Psychiatric comorbidities common in newly diagnosed pediatric epilepsy cases

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – About one in three children diagnosed with new-onset epilepsy presents with psychiatric diagnoses at the onset, results from a single-center study showed.

The finding “tells us that when kids are coming in, even if they’re only having psychiatric symptoms at their onset of epilepsy, they should be referred for some treatment to help them possibly mitigate the development of these psychiatric diagnoses in the first year,” lead study author Julia Doss, PsyD, said in an interview at annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

Dr. Doss, a clinical psychologist with Minnesota Epilepsy Group, and her associates divided the children into three groups: age 3-6 (group 1), age 7-11 (group 2), and age 12-18 (group 3). Based on the Clinical Interview, none of the patients in group 1 screened positive for depression or anxiety, but 16% met criteria for some other behavioral disorder. However, among patients in group 2, the percentage who met criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 13%, 25%, and 13%, respectively. The corresponding percentages for patients in group 3 were 29%, 38%, and 10%.

Of the 96 patients evaluated in the clinic, 64 parents completed all of the questions on the SDQ. The researchers observed significant correlations between parent response and diagnoses assigned on the Clinical Interview for behavior diagnoses (P = .002) and anxiety diagnoses (P = .009) but not for depression diagnoses. “Despite the correlations on both behavior and anxiety responses and clinical diagnoses assigned, parents still only reported significant concerns in about half of the children that were given diagnoses,” Dr. Doss and her associates wrote in their abstract.

The comparison of RCADS scores between parent and child demonstrated moderate to strong correlation with each other on the following scales: separation anxiety, generalized anxiety, obsessive/compulsive, and depression.

Dr. Doss cited the study’s small sample size as a key limitation. “Early evaluation or at least screening is necessary in all of our kids who present with an epilepsy diagnosis, because more than 30% develop psychiatric disorders within the first year of their diagnosis,” she concluded. “That’s one in three, so if we can start to better evaluate that early and get them funneled into treatment early, we might be able to prevent some of these problems from becoming lifelong issues.”

She reported having no financial disclosures.

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among patients aged 12-18 years, the percentage who met criteria for criteria for depression, anxiety, and other behavioral disorders was 29%, 38%, and 10%, respectively.

Data source: A study of 96 patients who presented to a New Onset Pediatric Epilepsy (NOPE) clinic within 8 weeks of their epilepsy diagnosis.

Disclosures: Dr. Doss reported having no financial disclosures.

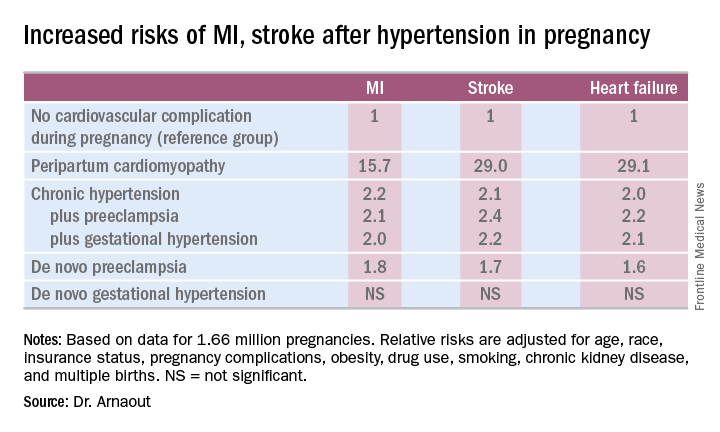

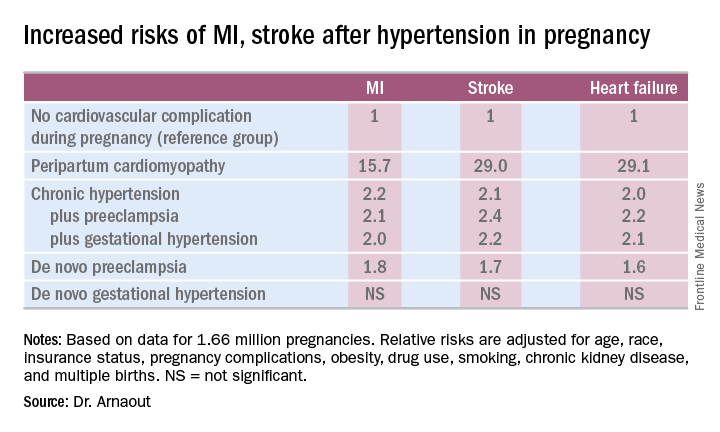

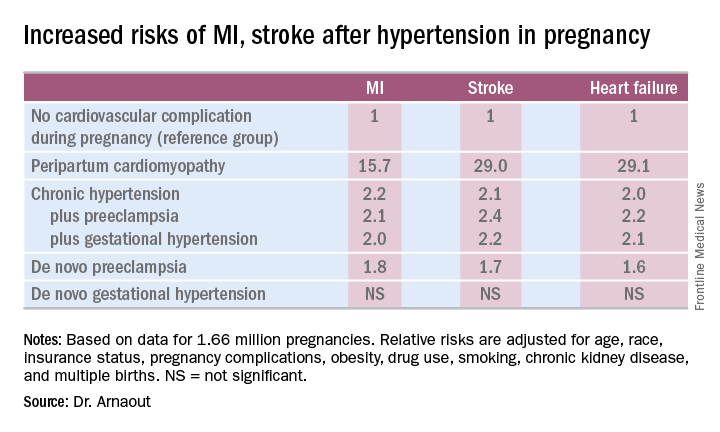

Cardiovascular complications in pregnancy quickly boost future risk

NEW ORLEANS – Women who experience peripartum cardiomyopathy or any of a variety of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are at sharply increased risk of acute MI, stroke, or new-onset heart failure beginning within just a few years, Rima Arnaout, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our study supports the idea that women who have cardiovascular complications in pregnancy really need to be monitored closely for potential primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Arnaout of the University of California, San Francisco.

At a session devoted to “big data” studies in cardiovascular medicine, she presented one of the biggest: a retrospective cohort study of 1.66 million pregnancies during 2005-2009 in California women without any history of congenital or valvular heart disease or prepregnancy cardiovascular events. The California database was created as part of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s comprehensive Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, which included more than 95% of the state’s hospitals. Women who experienced an MI or a stroke, or who were diagnosed with heart failure, during a median of 2.7 years and a maximum of 6 years of follow-up post pregnancy were identified via ICD-9 codes.

There were 111,202 cases of various forms of hypertension in pregnancy, for a 6.9% incidence. Peripartum cardiomyopathy was diagnosed in 562 women, for a rate of 3.5 cases per 10,000 pregnancies.

Indeed, in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for numerous potential confounders, peripartum cardiomyopathy was associated with a 16-fold increased risk of acute MI during the relatively short follow-up period, as well as 29-fold increased risks of stroke and heart failure, compared with women with no cardiovascular issues during their pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension, regardless of whether it occurred alone or in combination with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, was associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of each of the three study outcomes, compared with women who didn’t experience a cardiovascular complication during pregnancy. De novo preeclampsia was also associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of later MI, heart failure, or stroke.

The only form of hypertension in pregnancy that wasn’t associated with a subsequent significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events was de novo gestational hypertension.

Audience member David C. Goff Jr., MD, head of the division of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md., rose to compliment Dr. Arnaout: “Great work and really important.”

He said that her findings are consistent with the notion that pregnancy constitutes a sort of early-life cardiovascular stress test. He said he wondered, however, just how comfortable Dr. Arnaout is in stating that gestational diabetes isn’t associated with increased subsequent cardiovascular risk, given the relatively short follow-up to date in this population of women who still remain several decades away from the age when cardiovascular event rates really start to climb.

“I completely agree with you,” she replied, noting that other investigators utilizing a different registry have reported an increased longer-term risk for women with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Arnaout said she and her coinvestigators plan to continue to follow the women who experienced peripartum cardiomyopathy or hypertension in pregnancy longer term. They’re also in the process of breaking down the data to look at the risks associated with specific subtypes of MI, stroke, and heart failure.

Dr. Arnaout reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the American Heart Association and the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

NEW ORLEANS – Women who experience peripartum cardiomyopathy or any of a variety of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are at sharply increased risk of acute MI, stroke, or new-onset heart failure beginning within just a few years, Rima Arnaout, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our study supports the idea that women who have cardiovascular complications in pregnancy really need to be monitored closely for potential primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Arnaout of the University of California, San Francisco.

At a session devoted to “big data” studies in cardiovascular medicine, she presented one of the biggest: a retrospective cohort study of 1.66 million pregnancies during 2005-2009 in California women without any history of congenital or valvular heart disease or prepregnancy cardiovascular events. The California database was created as part of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s comprehensive Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, which included more than 95% of the state’s hospitals. Women who experienced an MI or a stroke, or who were diagnosed with heart failure, during a median of 2.7 years and a maximum of 6 years of follow-up post pregnancy were identified via ICD-9 codes.

There were 111,202 cases of various forms of hypertension in pregnancy, for a 6.9% incidence. Peripartum cardiomyopathy was diagnosed in 562 women, for a rate of 3.5 cases per 10,000 pregnancies.

Indeed, in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for numerous potential confounders, peripartum cardiomyopathy was associated with a 16-fold increased risk of acute MI during the relatively short follow-up period, as well as 29-fold increased risks of stroke and heart failure, compared with women with no cardiovascular issues during their pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension, regardless of whether it occurred alone or in combination with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, was associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of each of the three study outcomes, compared with women who didn’t experience a cardiovascular complication during pregnancy. De novo preeclampsia was also associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of later MI, heart failure, or stroke.

The only form of hypertension in pregnancy that wasn’t associated with a subsequent significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events was de novo gestational hypertension.

Audience member David C. Goff Jr., MD, head of the division of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md., rose to compliment Dr. Arnaout: “Great work and really important.”

He said that her findings are consistent with the notion that pregnancy constitutes a sort of early-life cardiovascular stress test. He said he wondered, however, just how comfortable Dr. Arnaout is in stating that gestational diabetes isn’t associated with increased subsequent cardiovascular risk, given the relatively short follow-up to date in this population of women who still remain several decades away from the age when cardiovascular event rates really start to climb.

“I completely agree with you,” she replied, noting that other investigators utilizing a different registry have reported an increased longer-term risk for women with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Arnaout said she and her coinvestigators plan to continue to follow the women who experienced peripartum cardiomyopathy or hypertension in pregnancy longer term. They’re also in the process of breaking down the data to look at the risks associated with specific subtypes of MI, stroke, and heart failure.

Dr. Arnaout reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the American Heart Association and the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

NEW ORLEANS – Women who experience peripartum cardiomyopathy or any of a variety of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy are at sharply increased risk of acute MI, stroke, or new-onset heart failure beginning within just a few years, Rima Arnaout, MD, reported at the American Heart Association scientific sessions.

“Our study supports the idea that women who have cardiovascular complications in pregnancy really need to be monitored closely for potential primary prevention of cardiovascular events,” said Dr. Arnaout of the University of California, San Francisco.

At a session devoted to “big data” studies in cardiovascular medicine, she presented one of the biggest: a retrospective cohort study of 1.66 million pregnancies during 2005-2009 in California women without any history of congenital or valvular heart disease or prepregnancy cardiovascular events. The California database was created as part of the U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality’s comprehensive Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project, which included more than 95% of the state’s hospitals. Women who experienced an MI or a stroke, or who were diagnosed with heart failure, during a median of 2.7 years and a maximum of 6 years of follow-up post pregnancy were identified via ICD-9 codes.

There were 111,202 cases of various forms of hypertension in pregnancy, for a 6.9% incidence. Peripartum cardiomyopathy was diagnosed in 562 women, for a rate of 3.5 cases per 10,000 pregnancies.

Indeed, in a multivariate Cox proportional hazards analysis adjusted for numerous potential confounders, peripartum cardiomyopathy was associated with a 16-fold increased risk of acute MI during the relatively short follow-up period, as well as 29-fold increased risks of stroke and heart failure, compared with women with no cardiovascular issues during their pregnancy.

Chronic hypertension, regardless of whether it occurred alone or in combination with preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, was associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of each of the three study outcomes, compared with women who didn’t experience a cardiovascular complication during pregnancy. De novo preeclampsia was also associated with roughly a twofold increased risk of later MI, heart failure, or stroke.

The only form of hypertension in pregnancy that wasn’t associated with a subsequent significantly increased risk of cardiovascular events was de novo gestational hypertension.

Audience member David C. Goff Jr., MD, head of the division of cardiovascular sciences at the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute in Bethesda, Md., rose to compliment Dr. Arnaout: “Great work and really important.”

He said that her findings are consistent with the notion that pregnancy constitutes a sort of early-life cardiovascular stress test. He said he wondered, however, just how comfortable Dr. Arnaout is in stating that gestational diabetes isn’t associated with increased subsequent cardiovascular risk, given the relatively short follow-up to date in this population of women who still remain several decades away from the age when cardiovascular event rates really start to climb.

“I completely agree with you,” she replied, noting that other investigators utilizing a different registry have reported an increased longer-term risk for women with gestational diabetes.

Dr. Arnaout said she and her coinvestigators plan to continue to follow the women who experienced peripartum cardiomyopathy or hypertension in pregnancy longer term. They’re also in the process of breaking down the data to look at the risks associated with specific subtypes of MI, stroke, and heart failure.

Dr. Arnaout reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the American Heart Association and the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point:

Major finding: California women who developed peripartum cardiomyopathy were at 16- to 29-fold increased risk of experiencing an acute MI, stroke, or heart failure during a median 2.7 years of follow-up.

Data source: A retrospective cohort study of more than 95% of pregnancies in California during 2005-2009.

Disclosures: The presenter reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study, which was supported by the American Heart Association and the Sarnoff Cardiovascular Research Foundation.

NIAID panel: Introduce peanut foods early to cut allergy risk

Introducing peanut foods to children who are at different levels of risk for peanut allergies may prevent or mitigate the risk, and the strategies for clinicians are explained in new addendum guidelines issued by an expert panel sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The guidelines were published online Jan. 5 in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.010).

“In the majority of patients, peanut allergy begins early in life and persists as a lifelong problem,” wrote lead author Alkis Togias, MD, of NIAID in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues. Previous guidelines published in 2010 did not provide specific treatment strategies for peanut allergies because of a lack of research, but the significant results of the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study suggested that early exposure to peanut-containing foods reduces the risk of developing allergies.

The NIAID’s Guidelines Coordinating Committee conducted a literature review covering research from January 2010 to June 2016 and developed addendum guidelines, as follows:

For infants with severe eczema, egg allergies, or both, peanut-containing foods should be introduced at 4-6 months of age at the earliest, after the introduction of other solid foods to confirm developmental readiness. If the infant is developmentally ready for solids, clinicians should “strongly consider” evaluation by peanut-specific IgE (peanut sIgE) measurement and/or skin prick test before introducing peanut products to determine the potential sensitivity and need for supervised feeding vs. feeding at home.

If dietary peanut will be introduced based on the recommendations, “the total amount of peanut protein to be regularly consumed per week should be approximately 6 to 7 g over 3 or more feedings,” the authors wrote.

However, children already identified as allergic to peanut should practice strict peanut avoidance, they added. In addition, they recommend that clinicians review risks and benefits for high-risk children who may have family members with established peanut allergies.

For infants with mild to moderate eczema, the recommendation is to introduce peanut-containing foods at approximately 6 months of age, “in accordance with family preferences and cultural practices,” after the introduction of other solid foods, to help reduce the risk of peanut allergies. The expert panel recommends that infants in this moderate-risk category may receive peanut foods at home without an office visit, although caregivers or clinicians may choose an office visit for supervised feeding, evaluation, or both. Although the LEAP trial did not target infants with mild or moderate eczema, the panel has no reason to believe that the protective mechanisms are different in these children.

For infants with no eczema or any food allergies, the guidelines recommend introducing peanut-containing foods at any age, as appropriate and in keeping with a family’s preferences and cultural practices.

“The early introduction of dietary peanut in children without risk factors for peanut allergy is generally anticipated to be safe and to contribute modestly to an overall reduction in the prevalence of peanut allergy,” the researchers said.

The findings of the LEAP and accompanying LEAP-On trials were so compelling (approximately 80% relative reduction in peanut allergy at 5 years of age for peanut-exposed children, compared with standard of care) that the NIAID and expert panel “felt it was necessary to review and revise the previous recommendations from the 2010 guidelines on the diagnosis and management of food allergy,” Hugh Sampson, MD, director of the Jaffe Food Allergy Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, and a member of the panel, said in an interview.

“It is critical that pediatricians and family practitioners identify infants at high risk for developing peanut allergy (severe atopic dermatitis or egg allergy) between 4 and 6 months of age, evaluate them, or refer them to a food allergy specialist when necessary,” Dr. Sampson said.

“Have parents introduce peanut into the infant’s diet on a regular basis. It is important for parents to notify their pediatrician or family physician if they suspect their infant is at high risk for developing peanut allergy,” he added. “Also, once early peanut introduction is started, it is important that parents continue to provide peanut on a regular basis for several years.”

Next steps for research include pursuing other allergens, said Dr. Sampson. “Similar studies need to be done to determine if early introduction of other foods, such as milk, egg, [or] tree nuts will prevent these common food allergies in high-risk infants.”

Also, it will be important to study whether infants at mild to moderate risk for developing peanut or other food allergies as evidenced by mild to moderate eczema will experience the same benefits in allergy risk reduction seen in the highest-risk children, he added.

The panelists had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Introducing peanut foods to children who are at different levels of risk for peanut allergies may prevent or mitigate the risk, and the strategies for clinicians are explained in new addendum guidelines issued by an expert panel sponsored by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases.

The guidelines were published online Jan. 5 in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2016.10.010).

“In the majority of patients, peanut allergy begins early in life and persists as a lifelong problem,” wrote lead author Alkis Togias, MD, of NIAID in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues. Previous guidelines published in 2010 did not provide specific treatment strategies for peanut allergies because of a lack of research, but the significant results of the Learning Early About Peanut Allergy (LEAP) study suggested that early exposure to peanut-containing foods reduces the risk of developing allergies.

The NIAID’s Guidelines Coordinating Committee conducted a literature review covering research from January 2010 to June 2016 and developed addendum guidelines, as follows:

For infants with severe eczema, egg allergies, or both, peanut-containing foods should be introduced at 4-6 months of age at the earliest, after the introduction of other solid foods to confirm developmental readiness. If the infant is developmentally ready for solids, clinicians should “strongly consider” evaluation by peanut-specific IgE (peanut sIgE) measurement and/or skin prick test before introducing peanut products to determine the potential sensitivity and need for supervised feeding vs. feeding at home.

If dietary peanut will be introduced based on the recommendations, “the total amount of peanut protein to be regularly consumed per week should be approximately 6 to 7 g over 3 or more feedings,” the authors wrote.