User login

Colchicine Effective for First Episode of Acute Pericarditis

Clinical question

Does the addition of colchicine improve outcomes in the treatment of an initial episode of acute pericarditis?

Bottom line

When used in addition to conventional anti-inflammatory therapy, colchicine decreases the rate of incessant or recurrent pericarditis. You would need to treat 4 patients with colchicine to prevent one such episode. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Imazio M, Brucato A, Cemin R, et al, for the ICAP Investigators. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med 2013;369(16):1522-1528.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

Funding source

Government

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Colchicine has been previously shown effective in the prevention of recurrent pericarditis (Daily POEM 12-16-2011). In this study, patients with a first episode of acute pericarditis were randomized to receive either colchicine (0.5 mg - 1 mg daily for 3 months; n = 120) or matching placebo (n = 120). All patients also received conventional treatment for acute pericarditis, either aspirin 800 mg or ibuprofen 600 mg every 8 hours for 7 to 10 days, followed by a taper, or (for those with contraindications to aspirin or ibuprofen) glucorticoid therapy for 2 weeks, followed by a taper. Baseline characteristics in the 2 groups were similar: mean age was 52 years, 60% were male, and the most common cause of pericarditis was idiopathic. The majority of patients received aspirin rather than ibuprofen or glucocorticoids as concomitant therapy. Adherence to the study drug was higher than 95% and did not differ between the 2 groups. Patients were followed up for a mean of 22 months and none were lost to follow-up. Analysis was by intention to treat. The primary outcome of incessant or recurrent pericarditis was decreased in the colchicine group as compared with the placebo group (16.7% vs 37.5%; relative risk = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.30-0.72; P < .001). In addition, the colchicine group had significantly better outcomes with regard to the number of patients with persistent symptoms at 72 hours (19% vs 40%), rate of remission within 1 week (85% vs 58%), time to first recurrence (25 weeks vs 18 weeks), and rate of percarditis-related hospitalizations (5% vs 14%). There was no difference in either overall side effects or gastrointestinal side effects between the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does the addition of colchicine improve outcomes in the treatment of an initial episode of acute pericarditis?

Bottom line

When used in addition to conventional anti-inflammatory therapy, colchicine decreases the rate of incessant or recurrent pericarditis. You would need to treat 4 patients with colchicine to prevent one such episode. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Imazio M, Brucato A, Cemin R, et al, for the ICAP Investigators. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med 2013;369(16):1522-1528.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

Funding source

Government

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Colchicine has been previously shown effective in the prevention of recurrent pericarditis (Daily POEM 12-16-2011). In this study, patients with a first episode of acute pericarditis were randomized to receive either colchicine (0.5 mg - 1 mg daily for 3 months; n = 120) or matching placebo (n = 120). All patients also received conventional treatment for acute pericarditis, either aspirin 800 mg or ibuprofen 600 mg every 8 hours for 7 to 10 days, followed by a taper, or (for those with contraindications to aspirin or ibuprofen) glucorticoid therapy for 2 weeks, followed by a taper. Baseline characteristics in the 2 groups were similar: mean age was 52 years, 60% were male, and the most common cause of pericarditis was idiopathic. The majority of patients received aspirin rather than ibuprofen or glucocorticoids as concomitant therapy. Adherence to the study drug was higher than 95% and did not differ between the 2 groups. Patients were followed up for a mean of 22 months and none were lost to follow-up. Analysis was by intention to treat. The primary outcome of incessant or recurrent pericarditis was decreased in the colchicine group as compared with the placebo group (16.7% vs 37.5%; relative risk = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.30-0.72; P < .001). In addition, the colchicine group had significantly better outcomes with regard to the number of patients with persistent symptoms at 72 hours (19% vs 40%), rate of remission within 1 week (85% vs 58%), time to first recurrence (25 weeks vs 18 weeks), and rate of percarditis-related hospitalizations (5% vs 14%). There was no difference in either overall side effects or gastrointestinal side effects between the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does the addition of colchicine improve outcomes in the treatment of an initial episode of acute pericarditis?

Bottom line

When used in addition to conventional anti-inflammatory therapy, colchicine decreases the rate of incessant or recurrent pericarditis. You would need to treat 4 patients with colchicine to prevent one such episode. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Imazio M, Brucato A, Cemin R, et al, for the ICAP Investigators. A randomized trial of colchicine for acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med 2013;369(16):1522-1528.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

Funding source

Government

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Colchicine has been previously shown effective in the prevention of recurrent pericarditis (Daily POEM 12-16-2011). In this study, patients with a first episode of acute pericarditis were randomized to receive either colchicine (0.5 mg - 1 mg daily for 3 months; n = 120) or matching placebo (n = 120). All patients also received conventional treatment for acute pericarditis, either aspirin 800 mg or ibuprofen 600 mg every 8 hours for 7 to 10 days, followed by a taper, or (for those with contraindications to aspirin or ibuprofen) glucorticoid therapy for 2 weeks, followed by a taper. Baseline characteristics in the 2 groups were similar: mean age was 52 years, 60% were male, and the most common cause of pericarditis was idiopathic. The majority of patients received aspirin rather than ibuprofen or glucocorticoids as concomitant therapy. Adherence to the study drug was higher than 95% and did not differ between the 2 groups. Patients were followed up for a mean of 22 months and none were lost to follow-up. Analysis was by intention to treat. The primary outcome of incessant or recurrent pericarditis was decreased in the colchicine group as compared with the placebo group (16.7% vs 37.5%; relative risk = 0.56; 95% CI, 0.30-0.72; P < .001). In addition, the colchicine group had significantly better outcomes with regard to the number of patients with persistent symptoms at 72 hours (19% vs 40%), rate of remission within 1 week (85% vs 58%), time to first recurrence (25 weeks vs 18 weeks), and rate of percarditis-related hospitalizations (5% vs 14%). There was no difference in either overall side effects or gastrointestinal side effects between the 2 groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

The danger of measles

First the good news: According to a study commissioned by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and published in JAMA Pediatrics on Dec. 5, measles was officially eliminated in the United States in 2000, and that elimination persisted until 2011. This shows that the vaccine, first approved in 1963, has been effective at "eliminating" the disease, defined as the absence of endemic disease transmission.

This is no small feat. Measles is highly contagious, and prior to 1963, resulted in about 500 deaths per year in the United States, and tens of thousands of hospitalizations. Because it’s so highly contagious, vaccinating a large chunk of susceptible patients was the only way to effectively combat the disease. The "elimination" of the disease marks the success of vaccination strategies. Globally, there are now 500,000 fewer deaths per year from measles than there were a decade ago. If we continue with vaccination programs as we do, there is a chance we can eradicate the disease (JAMA Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4342]).

Now the bad news: This year, according to a statement that the CDC put out on Dec. 5, there have been 175 cases of measles. This is three times the annual median number of about 60. These cases have been concentrated in communities that are against vaccination, usually brought in from other places where antivaccination sentiments are also high, like Europe, or where vaccination strategies are lagging, like the developing world.

In a well-publicized outbreak in Texas in August, 21 unvaccinated people belonging to the Eagle Mountain International Church contracted the disease when an unvaccinated man travelled to Indonesia and came back ill. The pastor, Terri Copeland Pearsons, daughter of a televangelist Kenneth Copeland, clarifies that she is not against vaccinations but she has reservations about them. "The concerns we have had are primarily with very young children who have family history of autism and with bundling too many immunizations at one time."

Ms. Pearsons further says: "the facts are the facts, but then we know the truth. That always overcomes facts." When did fact become the enemy? How does faith trump science? Why do people treat science with such skepticism, and yet take anecdotes as gospel truth? How is it that despite the best efforts of infectious disease and pediatric societies to dispel such mistaken notions, these ideas survive?

In studies exploring the psychology of vaccine refusal, the factors that parents take into consideration include, but are not limited to, the perceptions of vulnerability of the children, severity of the disease, and safety of the vaccine.

People have forgotten just how severe measles can be. In addition, the unfounded belief that the vaccine can cause autism has just taken on a life of its own, given credibility by celebrities.

I understand that for some people anecdotes often tell a more powerful story than data does. So here’s one anecdote from the personal anecdote library of a doctor from a developing country.

I knew Albert through mutual friends. He played bass in a rock band, belonged to a fraternity in medical school, was involved in intramural basketball, and was in a loving relationship. By the time we graduated from medical school, he was the proud father of a baby girl.

But then things seemed to fall out of place. He failed the medical boards. He uncharacteristically sank into a deep depression that was so severe that he required inpatient treatment, and even then the treatments were not working. Still the assumption was that he had depression from his life’s circumstances.

And then he had a seizure.

That was when the diagnosis of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, or SSPE, was made. It explained the personality change, intellectual difficulty, and seizures. He had contracted measles 10 years earlier, and this is a known complication of measles, one that hospitals in the Philippines are unfortunately all too familiar with. He died within a few weeks of diagnosis.

Society has forgotten how severe measles can be. We have an effective vaccine and effective global vaccination programs. We therefore have a chance to eradicate this disease altogether, like we did with smallpox and like we’re trying to do with polio. One parent’s strongly held but erroneous beliefs can cause trouble for large segments of the population. Ignoring the antivaccination rhetoric won’t make it go away.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

First the good news: According to a study commissioned by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and published in JAMA Pediatrics on Dec. 5, measles was officially eliminated in the United States in 2000, and that elimination persisted until 2011. This shows that the vaccine, first approved in 1963, has been effective at "eliminating" the disease, defined as the absence of endemic disease transmission.

This is no small feat. Measles is highly contagious, and prior to 1963, resulted in about 500 deaths per year in the United States, and tens of thousands of hospitalizations. Because it’s so highly contagious, vaccinating a large chunk of susceptible patients was the only way to effectively combat the disease. The "elimination" of the disease marks the success of vaccination strategies. Globally, there are now 500,000 fewer deaths per year from measles than there were a decade ago. If we continue with vaccination programs as we do, there is a chance we can eradicate the disease (JAMA Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4342]).

Now the bad news: This year, according to a statement that the CDC put out on Dec. 5, there have been 175 cases of measles. This is three times the annual median number of about 60. These cases have been concentrated in communities that are against vaccination, usually brought in from other places where antivaccination sentiments are also high, like Europe, or where vaccination strategies are lagging, like the developing world.

In a well-publicized outbreak in Texas in August, 21 unvaccinated people belonging to the Eagle Mountain International Church contracted the disease when an unvaccinated man travelled to Indonesia and came back ill. The pastor, Terri Copeland Pearsons, daughter of a televangelist Kenneth Copeland, clarifies that she is not against vaccinations but she has reservations about them. "The concerns we have had are primarily with very young children who have family history of autism and with bundling too many immunizations at one time."

Ms. Pearsons further says: "the facts are the facts, but then we know the truth. That always overcomes facts." When did fact become the enemy? How does faith trump science? Why do people treat science with such skepticism, and yet take anecdotes as gospel truth? How is it that despite the best efforts of infectious disease and pediatric societies to dispel such mistaken notions, these ideas survive?

In studies exploring the psychology of vaccine refusal, the factors that parents take into consideration include, but are not limited to, the perceptions of vulnerability of the children, severity of the disease, and safety of the vaccine.

People have forgotten just how severe measles can be. In addition, the unfounded belief that the vaccine can cause autism has just taken on a life of its own, given credibility by celebrities.

I understand that for some people anecdotes often tell a more powerful story than data does. So here’s one anecdote from the personal anecdote library of a doctor from a developing country.

I knew Albert through mutual friends. He played bass in a rock band, belonged to a fraternity in medical school, was involved in intramural basketball, and was in a loving relationship. By the time we graduated from medical school, he was the proud father of a baby girl.

But then things seemed to fall out of place. He failed the medical boards. He uncharacteristically sank into a deep depression that was so severe that he required inpatient treatment, and even then the treatments were not working. Still the assumption was that he had depression from his life’s circumstances.

And then he had a seizure.

That was when the diagnosis of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, or SSPE, was made. It explained the personality change, intellectual difficulty, and seizures. He had contracted measles 10 years earlier, and this is a known complication of measles, one that hospitals in the Philippines are unfortunately all too familiar with. He died within a few weeks of diagnosis.

Society has forgotten how severe measles can be. We have an effective vaccine and effective global vaccination programs. We therefore have a chance to eradicate this disease altogether, like we did with smallpox and like we’re trying to do with polio. One parent’s strongly held but erroneous beliefs can cause trouble for large segments of the population. Ignoring the antivaccination rhetoric won’t make it go away.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

First the good news: According to a study commissioned by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and published in JAMA Pediatrics on Dec. 5, measles was officially eliminated in the United States in 2000, and that elimination persisted until 2011. This shows that the vaccine, first approved in 1963, has been effective at "eliminating" the disease, defined as the absence of endemic disease transmission.

This is no small feat. Measles is highly contagious, and prior to 1963, resulted in about 500 deaths per year in the United States, and tens of thousands of hospitalizations. Because it’s so highly contagious, vaccinating a large chunk of susceptible patients was the only way to effectively combat the disease. The "elimination" of the disease marks the success of vaccination strategies. Globally, there are now 500,000 fewer deaths per year from measles than there were a decade ago. If we continue with vaccination programs as we do, there is a chance we can eradicate the disease (JAMA Pediatrics 2013 [doi:10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.4342]).

Now the bad news: This year, according to a statement that the CDC put out on Dec. 5, there have been 175 cases of measles. This is three times the annual median number of about 60. These cases have been concentrated in communities that are against vaccination, usually brought in from other places where antivaccination sentiments are also high, like Europe, or where vaccination strategies are lagging, like the developing world.

In a well-publicized outbreak in Texas in August, 21 unvaccinated people belonging to the Eagle Mountain International Church contracted the disease when an unvaccinated man travelled to Indonesia and came back ill. The pastor, Terri Copeland Pearsons, daughter of a televangelist Kenneth Copeland, clarifies that she is not against vaccinations but she has reservations about them. "The concerns we have had are primarily with very young children who have family history of autism and with bundling too many immunizations at one time."

Ms. Pearsons further says: "the facts are the facts, but then we know the truth. That always overcomes facts." When did fact become the enemy? How does faith trump science? Why do people treat science with such skepticism, and yet take anecdotes as gospel truth? How is it that despite the best efforts of infectious disease and pediatric societies to dispel such mistaken notions, these ideas survive?

In studies exploring the psychology of vaccine refusal, the factors that parents take into consideration include, but are not limited to, the perceptions of vulnerability of the children, severity of the disease, and safety of the vaccine.

People have forgotten just how severe measles can be. In addition, the unfounded belief that the vaccine can cause autism has just taken on a life of its own, given credibility by celebrities.

I understand that for some people anecdotes often tell a more powerful story than data does. So here’s one anecdote from the personal anecdote library of a doctor from a developing country.

I knew Albert through mutual friends. He played bass in a rock band, belonged to a fraternity in medical school, was involved in intramural basketball, and was in a loving relationship. By the time we graduated from medical school, he was the proud father of a baby girl.

But then things seemed to fall out of place. He failed the medical boards. He uncharacteristically sank into a deep depression that was so severe that he required inpatient treatment, and even then the treatments were not working. Still the assumption was that he had depression from his life’s circumstances.

And then he had a seizure.

That was when the diagnosis of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis, or SSPE, was made. It explained the personality change, intellectual difficulty, and seizures. He had contracted measles 10 years earlier, and this is a known complication of measles, one that hospitals in the Philippines are unfortunately all too familiar with. He died within a few weeks of diagnosis.

Society has forgotten how severe measles can be. We have an effective vaccine and effective global vaccination programs. We therefore have a chance to eradicate this disease altogether, like we did with smallpox and like we’re trying to do with polio. One parent’s strongly held but erroneous beliefs can cause trouble for large segments of the population. Ignoring the antivaccination rhetoric won’t make it go away.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

Psychiatric medications and lactation: Informing clinical decisions

Over the last 2 decades, abundant data on the reproductive safety of medications used to treat psychiatric disorders have become available, filling in many gaps with respect to our knowledge about the safety of commonly used psychiatric medications during pregnancy. But the availability of such safety data with respect to the use of these agents during breastfeeding is less complete.

Because of fears of potential adverse effects on infants associated with psychotropic drug use during lactation, many women with a psychiatric disorder who are treated with a range of psychiatric medications are advised not to breastfeed; or if they choose to breastfeed, they are counseled to avoid taking the essential medication that has made them well. This has been a somewhat intuitive, cautious approach. However, in my 25 years of clinical experience taking care of pregnant and postpartum women with a range of psychiatric disorders, one sad scenario I have frequently witnessed is the woman who decides to defer pharmacologic treatment for severe postpartum psychiatric illness after being counseled to defer treatment given a wish to breastfeed. Those women often have been psychiatrically ill for months while breastfeeding after having decided to defer their own treatment because they do not want to expose the baby to even scant amounts of medication secreted into breast milk associated with use of a needed medicine during lactation.

In a recently published clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics committee on drugs, authors suggest that advice not to breastfeed or to uniformly avoid medications while nursing because of possible adverse effects in the infant is often not evidence based and may not be necessary in many cases. The committee states that most drugs do not pose a risk to the mother or infant who is nursing, and that "the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks of exposure to most therapeutic agents via human breast milk" (Pediatrics 2013;132:e796-e809).

The report points out that for certain drugs, a careful risk-benefit analysis is needed, especially for drugs that are concentrated in human milk, those with unproven benefits, and those with long half-lives. Importantly, the report notes say that decisions about the use of medications during lactation have to be made on a case-by-case basis. A concrete example would be exercising appropriate vigilance about the use of these medicines in premature infants with immature metabolism.

The report, published on-line in Pediatrics in August 2013, includes a section on antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics. As a resource for clinicians, the report highlights LactMed, part of the National Library of Medicine’s toxicology data network (TOXNET), which provides real-time updated scientific information on the excretion of drugs into breast milk.

The report makes the important distinction regarding the range of clinical decisions that get made in the context of different clinical situations. For example, at our center, patients frequently present with questions about whether to use psychiatric medications while breastfeeding when these women have already been taking the medication during pregnancy for treatment of underlying psychiatric disorder. Others make queries about introduction of pharmacologic therapy in the early postpartum period in the context, for example, of new-onset postpartum depression. Specifically, a woman with a history of psychiatric disorder who is treated with antidepressant during pregnancy may continue that medication across the postpartum period to attenuate risk for postpartum depression, particularly if she has a history of recurrent disease, or depressive relapse when medication has been discontinued. That is clinical scenario differs from that of a woman who develops new onset of depression during the postpartum period.

One part of the AAP report addresses use of certain psychiatric medications in the context of available information from the literature regarding extent of excretion of these medications into breast milk. This section states that many antianxiety drugs, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers are excreted in low concentrations into human milk, with the estimated infant doses under 2% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose. However, the authors also cite small series or case reports where infant plasma levels of some drugs were reported to exceed 10% of maternal plasma concentrations. They list 13 such drugs, which include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and mood stabilizers. It is important to keep in mind that the number of these cases is small and represent a very small proportion of cases, when the total denominator of reports in the literature of psychotropic drug use during lactation is considered. For example, olanzapine, a second generation antipsychotic is highlighted as an agent of concern based on one case report (J. Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:121-3).

The take-home message for the clinician is that all psychotropics are excreted into breast milk, even if quantification of the agents in breast milk or infant plasma reveals relatively scant concentration (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003;64:73-80). If mom takes the medicine coincident with lactation, baby is exposed. At our center, we are usually reluctant to discontinue a medication such as an atypical antipsychotic to treat bipolar disorder in the postpartum period even if the mom chooses to breastfeed considering the extent to which women with bipolar disorder are at a high risk for relapse during the puerperium.

Ironically, we probably have more information regarding the excretion of antidepressants and drugs such as lamotrigine, used as a mood stabilizer, into breast milk than most medicines women take during the postpartum period, with data over the past 15 years suggesting that these medications, like other medications, are excreted into breast milk and are present in infant plasma in extremely sparse concentrations. It is noteworthy that cases of frank newborn toxicity directly associated with mothers who breastfeed on psychiatric medications are extremely few and far between, and are anecdotal at best. For some context, the literature on the effects of SSRI use during pregnancy is vast and prevalence of use of these medications during pregnancy and the postpartum period is substantial; that being said, reports of adverse effects reported in the babies of women who breastfeed while taking an SSRI are scant and thus at least somewhat reassuring.

And yet, consistently, I have witnessed that psychiatric medications are highlighted in the literature as particular agents of concern when it comes to lactation, compared with other medicines, for which only sparse data are available. Whether this reflects a bias about the necessity of treating psychiatric disorders during the postpartum period is unknown. Certainly, the long-term implications for the infant of exposure to low concentrations of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medications in the context of breastfeeding exposure have yet to be clarified.

Whether a woman treated with a psychiatric medication during the post partum should breastfeed is a prime example of a clinical scenario in which there is no perfect decision, and we need to make the best decision possible, taking into account the available data, and the mother’s psychiatric disorder and her wishes. Some women may be extremely committed to breastfeeding and may choose to breastfeed, acknowledging some of the unknowns regarding these medications during lactation, while other women consider some of the ambiguity associated with the long-term effects of exposure while lactating and may choose not to breastfeed.

It is noteworthy that the AAP committee on drugs concluded the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risk of exposure to most therapeutic agents via human milk. And those at our center would certainly suggest that this is the case for psychiatric medications, particularly those used to sustain postpartum maternal psychiatric well-being, which is so critical. As is the case with any clinical decision, and certainly with respect to the use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation, the decision to treat is contingent on a careful risk-benefit analysis, where the risks of exposure to a medicine is weighed against the risk of untreated psychiatric illness. Even with the well-documented benefits of breastfeeding, nothing should trump the treatment of postpartum psychiatric illness, even if the cost is deferring breastfeeding. Treatment cannot be deferred because of the impact of untreated maternal psychiatric illness on maternal morbidity and on the development of children.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information about reproductive mental health at www.womensmentalhealth.org. To comment, e-mail him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com. Dr. Cohen has been a consultant to manufacturers of antidepressants and antipsychotic medications.

Over the last 2 decades, abundant data on the reproductive safety of medications used to treat psychiatric disorders have become available, filling in many gaps with respect to our knowledge about the safety of commonly used psychiatric medications during pregnancy. But the availability of such safety data with respect to the use of these agents during breastfeeding is less complete.

Because of fears of potential adverse effects on infants associated with psychotropic drug use during lactation, many women with a psychiatric disorder who are treated with a range of psychiatric medications are advised not to breastfeed; or if they choose to breastfeed, they are counseled to avoid taking the essential medication that has made them well. This has been a somewhat intuitive, cautious approach. However, in my 25 years of clinical experience taking care of pregnant and postpartum women with a range of psychiatric disorders, one sad scenario I have frequently witnessed is the woman who decides to defer pharmacologic treatment for severe postpartum psychiatric illness after being counseled to defer treatment given a wish to breastfeed. Those women often have been psychiatrically ill for months while breastfeeding after having decided to defer their own treatment because they do not want to expose the baby to even scant amounts of medication secreted into breast milk associated with use of a needed medicine during lactation.

In a recently published clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics committee on drugs, authors suggest that advice not to breastfeed or to uniformly avoid medications while nursing because of possible adverse effects in the infant is often not evidence based and may not be necessary in many cases. The committee states that most drugs do not pose a risk to the mother or infant who is nursing, and that "the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks of exposure to most therapeutic agents via human breast milk" (Pediatrics 2013;132:e796-e809).

The report points out that for certain drugs, a careful risk-benefit analysis is needed, especially for drugs that are concentrated in human milk, those with unproven benefits, and those with long half-lives. Importantly, the report notes say that decisions about the use of medications during lactation have to be made on a case-by-case basis. A concrete example would be exercising appropriate vigilance about the use of these medicines in premature infants with immature metabolism.

The report, published on-line in Pediatrics in August 2013, includes a section on antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics. As a resource for clinicians, the report highlights LactMed, part of the National Library of Medicine’s toxicology data network (TOXNET), which provides real-time updated scientific information on the excretion of drugs into breast milk.

The report makes the important distinction regarding the range of clinical decisions that get made in the context of different clinical situations. For example, at our center, patients frequently present with questions about whether to use psychiatric medications while breastfeeding when these women have already been taking the medication during pregnancy for treatment of underlying psychiatric disorder. Others make queries about introduction of pharmacologic therapy in the early postpartum period in the context, for example, of new-onset postpartum depression. Specifically, a woman with a history of psychiatric disorder who is treated with antidepressant during pregnancy may continue that medication across the postpartum period to attenuate risk for postpartum depression, particularly if she has a history of recurrent disease, or depressive relapse when medication has been discontinued. That is clinical scenario differs from that of a woman who develops new onset of depression during the postpartum period.

One part of the AAP report addresses use of certain psychiatric medications in the context of available information from the literature regarding extent of excretion of these medications into breast milk. This section states that many antianxiety drugs, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers are excreted in low concentrations into human milk, with the estimated infant doses under 2% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose. However, the authors also cite small series or case reports where infant plasma levels of some drugs were reported to exceed 10% of maternal plasma concentrations. They list 13 such drugs, which include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and mood stabilizers. It is important to keep in mind that the number of these cases is small and represent a very small proportion of cases, when the total denominator of reports in the literature of psychotropic drug use during lactation is considered. For example, olanzapine, a second generation antipsychotic is highlighted as an agent of concern based on one case report (J. Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:121-3).

The take-home message for the clinician is that all psychotropics are excreted into breast milk, even if quantification of the agents in breast milk or infant plasma reveals relatively scant concentration (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003;64:73-80). If mom takes the medicine coincident with lactation, baby is exposed. At our center, we are usually reluctant to discontinue a medication such as an atypical antipsychotic to treat bipolar disorder in the postpartum period even if the mom chooses to breastfeed considering the extent to which women with bipolar disorder are at a high risk for relapse during the puerperium.

Ironically, we probably have more information regarding the excretion of antidepressants and drugs such as lamotrigine, used as a mood stabilizer, into breast milk than most medicines women take during the postpartum period, with data over the past 15 years suggesting that these medications, like other medications, are excreted into breast milk and are present in infant plasma in extremely sparse concentrations. It is noteworthy that cases of frank newborn toxicity directly associated with mothers who breastfeed on psychiatric medications are extremely few and far between, and are anecdotal at best. For some context, the literature on the effects of SSRI use during pregnancy is vast and prevalence of use of these medications during pregnancy and the postpartum period is substantial; that being said, reports of adverse effects reported in the babies of women who breastfeed while taking an SSRI are scant and thus at least somewhat reassuring.

And yet, consistently, I have witnessed that psychiatric medications are highlighted in the literature as particular agents of concern when it comes to lactation, compared with other medicines, for which only sparse data are available. Whether this reflects a bias about the necessity of treating psychiatric disorders during the postpartum period is unknown. Certainly, the long-term implications for the infant of exposure to low concentrations of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medications in the context of breastfeeding exposure have yet to be clarified.

Whether a woman treated with a psychiatric medication during the post partum should breastfeed is a prime example of a clinical scenario in which there is no perfect decision, and we need to make the best decision possible, taking into account the available data, and the mother’s psychiatric disorder and her wishes. Some women may be extremely committed to breastfeeding and may choose to breastfeed, acknowledging some of the unknowns regarding these medications during lactation, while other women consider some of the ambiguity associated with the long-term effects of exposure while lactating and may choose not to breastfeed.

It is noteworthy that the AAP committee on drugs concluded the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risk of exposure to most therapeutic agents via human milk. And those at our center would certainly suggest that this is the case for psychiatric medications, particularly those used to sustain postpartum maternal psychiatric well-being, which is so critical. As is the case with any clinical decision, and certainly with respect to the use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation, the decision to treat is contingent on a careful risk-benefit analysis, where the risks of exposure to a medicine is weighed against the risk of untreated psychiatric illness. Even with the well-documented benefits of breastfeeding, nothing should trump the treatment of postpartum psychiatric illness, even if the cost is deferring breastfeeding. Treatment cannot be deferred because of the impact of untreated maternal psychiatric illness on maternal morbidity and on the development of children.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information about reproductive mental health at www.womensmentalhealth.org. To comment, e-mail him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com. Dr. Cohen has been a consultant to manufacturers of antidepressants and antipsychotic medications.

Over the last 2 decades, abundant data on the reproductive safety of medications used to treat psychiatric disorders have become available, filling in many gaps with respect to our knowledge about the safety of commonly used psychiatric medications during pregnancy. But the availability of such safety data with respect to the use of these agents during breastfeeding is less complete.

Because of fears of potential adverse effects on infants associated with psychotropic drug use during lactation, many women with a psychiatric disorder who are treated with a range of psychiatric medications are advised not to breastfeed; or if they choose to breastfeed, they are counseled to avoid taking the essential medication that has made them well. This has been a somewhat intuitive, cautious approach. However, in my 25 years of clinical experience taking care of pregnant and postpartum women with a range of psychiatric disorders, one sad scenario I have frequently witnessed is the woman who decides to defer pharmacologic treatment for severe postpartum psychiatric illness after being counseled to defer treatment given a wish to breastfeed. Those women often have been psychiatrically ill for months while breastfeeding after having decided to defer their own treatment because they do not want to expose the baby to even scant amounts of medication secreted into breast milk associated with use of a needed medicine during lactation.

In a recently published clinical report from the American Academy of Pediatrics committee on drugs, authors suggest that advice not to breastfeed or to uniformly avoid medications while nursing because of possible adverse effects in the infant is often not evidence based and may not be necessary in many cases. The committee states that most drugs do not pose a risk to the mother or infant who is nursing, and that "the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risks of exposure to most therapeutic agents via human breast milk" (Pediatrics 2013;132:e796-e809).

The report points out that for certain drugs, a careful risk-benefit analysis is needed, especially for drugs that are concentrated in human milk, those with unproven benefits, and those with long half-lives. Importantly, the report notes say that decisions about the use of medications during lactation have to be made on a case-by-case basis. A concrete example would be exercising appropriate vigilance about the use of these medicines in premature infants with immature metabolism.

The report, published on-line in Pediatrics in August 2013, includes a section on antidepressants, anxiolytics, and antipsychotics. As a resource for clinicians, the report highlights LactMed, part of the National Library of Medicine’s toxicology data network (TOXNET), which provides real-time updated scientific information on the excretion of drugs into breast milk.

The report makes the important distinction regarding the range of clinical decisions that get made in the context of different clinical situations. For example, at our center, patients frequently present with questions about whether to use psychiatric medications while breastfeeding when these women have already been taking the medication during pregnancy for treatment of underlying psychiatric disorder. Others make queries about introduction of pharmacologic therapy in the early postpartum period in the context, for example, of new-onset postpartum depression. Specifically, a woman with a history of psychiatric disorder who is treated with antidepressant during pregnancy may continue that medication across the postpartum period to attenuate risk for postpartum depression, particularly if she has a history of recurrent disease, or depressive relapse when medication has been discontinued. That is clinical scenario differs from that of a woman who develops new onset of depression during the postpartum period.

One part of the AAP report addresses use of certain psychiatric medications in the context of available information from the literature regarding extent of excretion of these medications into breast milk. This section states that many antianxiety drugs, antidepressants, and mood stabilizers are excreted in low concentrations into human milk, with the estimated infant doses under 2% of the weight-adjusted maternal dose. However, the authors also cite small series or case reports where infant plasma levels of some drugs were reported to exceed 10% of maternal plasma concentrations. They list 13 such drugs, which include selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), antipsychotics, anxiolytics, and mood stabilizers. It is important to keep in mind that the number of these cases is small and represent a very small proportion of cases, when the total denominator of reports in the literature of psychotropic drug use during lactation is considered. For example, olanzapine, a second generation antipsychotic is highlighted as an agent of concern based on one case report (J. Psychopharmacol. 2010;24:121-3).

The take-home message for the clinician is that all psychotropics are excreted into breast milk, even if quantification of the agents in breast milk or infant plasma reveals relatively scant concentration (J. Clin. Psychiatry 2003;64:73-80). If mom takes the medicine coincident with lactation, baby is exposed. At our center, we are usually reluctant to discontinue a medication such as an atypical antipsychotic to treat bipolar disorder in the postpartum period even if the mom chooses to breastfeed considering the extent to which women with bipolar disorder are at a high risk for relapse during the puerperium.

Ironically, we probably have more information regarding the excretion of antidepressants and drugs such as lamotrigine, used as a mood stabilizer, into breast milk than most medicines women take during the postpartum period, with data over the past 15 years suggesting that these medications, like other medications, are excreted into breast milk and are present in infant plasma in extremely sparse concentrations. It is noteworthy that cases of frank newborn toxicity directly associated with mothers who breastfeed on psychiatric medications are extremely few and far between, and are anecdotal at best. For some context, the literature on the effects of SSRI use during pregnancy is vast and prevalence of use of these medications during pregnancy and the postpartum period is substantial; that being said, reports of adverse effects reported in the babies of women who breastfeed while taking an SSRI are scant and thus at least somewhat reassuring.

And yet, consistently, I have witnessed that psychiatric medications are highlighted in the literature as particular agents of concern when it comes to lactation, compared with other medicines, for which only sparse data are available. Whether this reflects a bias about the necessity of treating psychiatric disorders during the postpartum period is unknown. Certainly, the long-term implications for the infant of exposure to low concentrations of psychiatric and nonpsychiatric medications in the context of breastfeeding exposure have yet to be clarified.

Whether a woman treated with a psychiatric medication during the post partum should breastfeed is a prime example of a clinical scenario in which there is no perfect decision, and we need to make the best decision possible, taking into account the available data, and the mother’s psychiatric disorder and her wishes. Some women may be extremely committed to breastfeeding and may choose to breastfeed, acknowledging some of the unknowns regarding these medications during lactation, while other women consider some of the ambiguity associated with the long-term effects of exposure while lactating and may choose not to breastfeed.

It is noteworthy that the AAP committee on drugs concluded the benefits of breastfeeding outweigh the risk of exposure to most therapeutic agents via human milk. And those at our center would certainly suggest that this is the case for psychiatric medications, particularly those used to sustain postpartum maternal psychiatric well-being, which is so critical. As is the case with any clinical decision, and certainly with respect to the use of psychiatric medications during pregnancy and lactation, the decision to treat is contingent on a careful risk-benefit analysis, where the risks of exposure to a medicine is weighed against the risk of untreated psychiatric illness. Even with the well-documented benefits of breastfeeding, nothing should trump the treatment of postpartum psychiatric illness, even if the cost is deferring breastfeeding. Treatment cannot be deferred because of the impact of untreated maternal psychiatric illness on maternal morbidity and on the development of children.

Dr. Cohen is the director of the Center for Women’s Mental Health at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, which provides information about reproductive mental health at www.womensmentalhealth.org. To comment, e-mail him at obnews@frontlinemedcom.com. Dr. Cohen has been a consultant to manufacturers of antidepressants and antipsychotic medications.

Measuring the MEWS and the Rothman Index

Bedside calculation of early warning system (EWS) scores is standard practice in many hospitals to predict clinical deterioration. These systems were designed for periodic hand‐scoring, typically using a half‐dozen variables dominated by vital signs. Most derive from the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS).[1, 2] Despite years of modification, EWSs have had only modest impact on outcomes.[3, 4] Major improvement is possible only by adding more information than is contained in vital signs. Thus, the next generation of EWSs must analyze electronic medical records (EMRs). Analysis would be performed by computer, displayed automatically, and updated whenever new data are entered into the EMR. Such systems could deliver timely, accurate, longitudinally trended acuity information that could aid in earlier detection of declining patient condition as well as improving sensitivity and specificity of EWS alarms.

Advancing this endeavor along with others,[5, 6] we previously published a patient acuity metric, the Rothman Index (RI), which automatically updates when asynchronous vital signs, laboratory test results, Braden Scale,[7] cardiac rhythm, and nursing assessments are entered into the EMR.[8] Our goal was to enable clinicians to visualize changes in acuity by simple line graphs personalized to each patient at any point in time across the trajectory of care. In our model validation studies,[8] we made no attempt to identify generalizable thresholds, though others[9] have defined decision cut points for RI in a nonemergent context. To examine decision support feasibility in an emergent context, and to compare RI with a general EWS standard, we compare the accuracy of the RI with the MEWS in predicting hospital death within 24 hours.

METHODS

Site Description and Ethics

The institutional review board of Abington Memorial Hospital (Abington, PA) approved collection of retrospective data obtained from their 665‐bed, regional referral center and teaching hospital. Handling of patient information complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations.

Patient Inclusion

The analysis included all patients, aged 18 years or older, admitted from July 2009 through June 2010, when there were sufficient data in the EMR to compute the RI. Obstetric and psychiatric patients were excluded because nursing documentation is insufficient in this dataset.

Data Collection/Data Sources

Clinical variables were extracted from the EMR (AllScripts Sunrise Clinical Manager, Chicago, IL) by SQL query and placed into a database. RI[8] and MEWS[1] were computed according to published methods. Table 1 shows definitions of standards for each nursing assessment,[8] and Table 2 identifies all clinical variables employed for each system. Briefly, RI utilizes 26 variables related to clinical care and routinely available in the EMR. These include vital signs, laboratory results, cardiac rhythms, and nursing assessments. Excess risk associated with any value of a variable is defined as percent absolute increase in 1‐year mortality relative to minimum 1‐year mortality identified for that variable. Excess risk is summed on a linear scale to reflect cumulative risk for individual patients at any given time. RI was computed at every new observation during a patient visit, when input values were available. Laboratory results are included when measured, but after 24 hours their weighting is reduced by 50%, and after 48 hours they are excluded. Data input intervals were a function of institutional patient care protocols and physician orders. All observations during a patient's stay were included in the analysis, per the method of Prytherch et al.[4] Because data did not contain the simplified alert/voice/pain/unresponsive (A/V/P/U) score, computation of MEWS used appropriate mapping of the Glasgow Coma Scale.[10] A corresponding MEWS was calculated for each RI. The relationship between RI and MEWS is inverse. RI ranges from 91 to 100, with lower scores indicating increasing acuity. MEWS ranges from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating increasing acuity.

| |

| Cardiac | Pulse regular, rate 60100 bpm, skin warm and dry. Blood pressure <140/90 and no symptoms of hypotension. |

| Food/nutrition | No difficulty with chewing, swallowing, or manual dexterity. Patient consuming >50% of daily diet ordered as observed or stated. |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdomen soft and nontender. Bowel sounds present. No nausea or vomiting. Continent. Bowel pattern normal as observed or stated. |

| Genitourinary | Voids without difficulty. Continent. Urine clear, yellow to amber as observed or stated. Urinary catheter patent if present. |

| Musculoskeletal | Independently able to move all extremities and perform functional activities as observed or stated (includes assistive devices). |

| Neurological | Alert and oriented to person, place, time, situation. Speech is coherent. |

| Peripheral‐vascular | Extremities are normal or pink and warm. Peripheral pulses palpable. Capillary refill <3 seconds. No edema, numbness or tingling. |

| Psychosocial | Behavior appropriate to situation. Expressed concerns and fears being addressed. Adequate support system. |

| Respiratory | Respiration 1224/minute at rest, quiet and regular. Bilateral breath sounds clear. Nail beds and mucous membranes pink. Sputum clear, if present. |

| Safety/fall risk | Safety/fall risk factors not present. Not a risk to self or others. |

| Skin/tissue | Skin clean, dry, and intact with no reddened areas. Patient is alert, cooperative and able to reposition self independently. Braden Scale >15. |

| Input Variable | A: Alive in 24 Hours, Mean (SD) | B: Dead Within 24 Hours, Mean (SD) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 66.8 (13.5) | 56.6 (16.8) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hga | 127.3 (23.8) | 105.2 (29.4) | <0.0001 |

| Temperature, Fa | 98.2 (1.1) | 98.2 (2.0) | 0.1165 |

| Respiration, breaths per minutea | 20.1 (4.7) | 23.6 (9.1) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, bpma | 81.1 (16.5) | 96.9 (22.2) | <0.0001 |

| Pulse oximetry, % O2 saturation | 96.3 (3.3) | 93.8 (10.1) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 23.9 (17.9) | 42.1 (26.4) | <0.0001 |

| Serum chloride, mmol/L | 104.3 (5.4) | 106.9 (9.7) | <0.0001 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 139.0 (4.1) | 140.7 (8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin, gm/dL | 11.2 (2.1) | 10.6 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| White blood cell count, 103 cell/L | 9.9 (6.3) | 15.0 (10.9) | <0.0001 |

| Braden Scale, total points | 17.7 (3.4) | 12.2 (3.1) | <0.0001 |

| NURSING ASSESSMENTS | A: Alive in 24 Hours and Failed Standard | B: Dead Within 24 Hours and Failed Standard | P Value |

| Neurological | 38.7% | 91.4% | <0.0001 |

| Genitourinary | 46.6% | 90.0% | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory | 55.6% | 89.0% | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular | 54.1% | 86.9% | <0.0001 |

| Food | 28.3% | 80.6% | <0.0001 |

| Skin | 56.3% | 75.0% | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 49.3% | 75.0% | <0.0001 |

| Musculoskeletal | 50.3% | 72.4% | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac | 30.4% | 59.8% | <0.0001 |

| Psychosocial | 24.6% | 40.9% | <0.0001 |

| Safety | 25.5% | 29.0% | <0.0001 |

| A/V/P/U scorea | 96.3/2.1/1.4/0.2% | 88.6/21.6/4.6/5.3% | <0.0001 |

| Sinus rhythm (absent)b | 34.9% | 53.3% | <0.0001 |

Outcome Ascertainment

In‐hospital death was determined by merging the date and time of discharge with clinical inputs from the hospital's EMR. Data points were judged to be within 24 hours of death if the timestamp of the data point collection was within 24 hours of the discharge time with expired as the discharge disposition.

Statistical Methods

Demographics and input variables from the 2 groups of observations, those who were within 24 hours of death and those who were not, were compared using a t test with a Cochran and Cox[11] approximation of the probability level of the approximate t statistic for unequal variances. Mean, standard deviation, and P values are reported. Discrimination of RI and MEWS to predict 24‐hour mortality was estimated using area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), and null hypothesis was tested using 2. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+, LR) were computed. Analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (procedures ttest, freq, logistic, nlmixed; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Typically MEWS=4 triggers a protocol to increase level of assessment and/or care, often a transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). We denoted the point on ROC curve where MEWS=4 and identified an RI point of similar LR and sensitivity to compare false alarm rate. Then we identified an RI point of similar LR+ for comparison of LR and sensitivity.

RESULTS

A total of 1,794,910 observations during 32,472 patient visits were included; 617 patients died (1.9%). Physiological characteristics for all input variables used by RI or MEWS are shown in Table 2, comparing observations taken within 24 hours of death to all other observations.

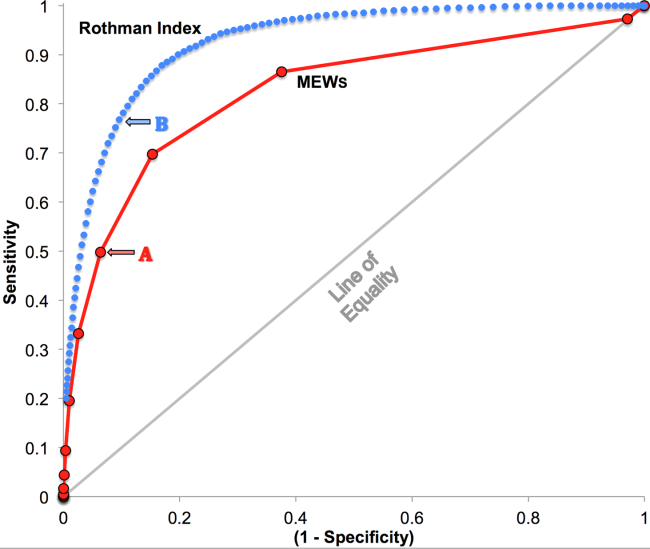

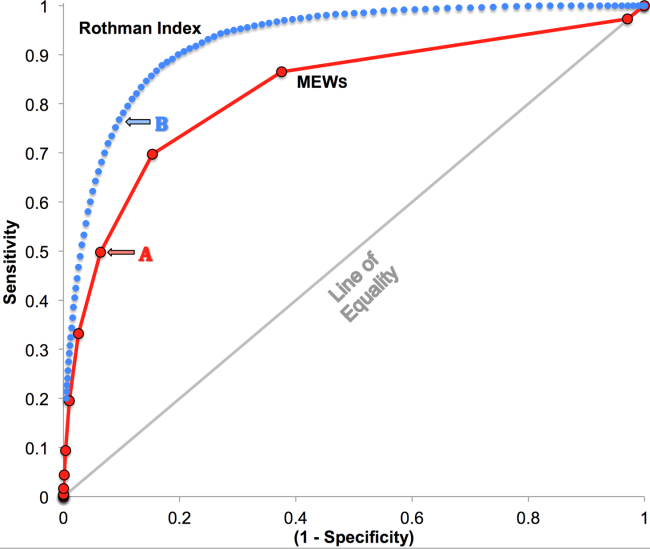

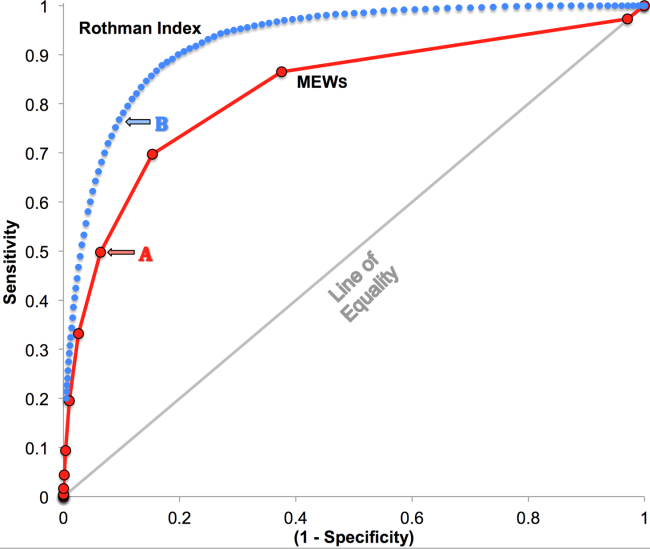

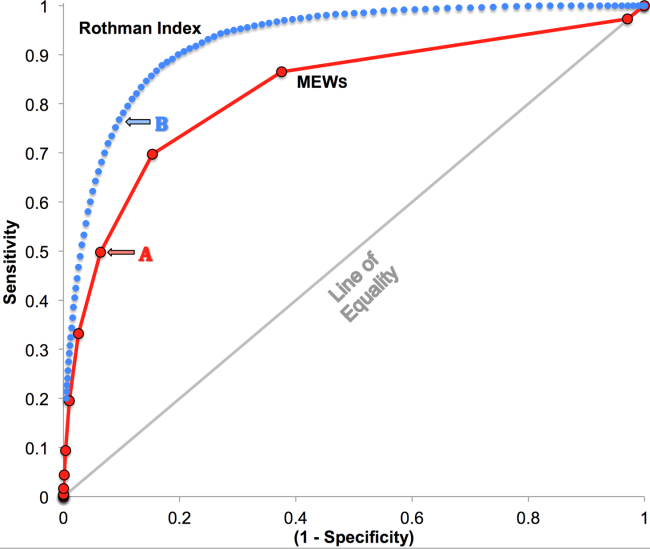

RI versus MEWS demonstrated superior discrimination of 24‐hour mortality (AUC was 0.93 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 0.92‐0.93] vs 0.82 [95% CI: 0.82‐0.83]; difference, 0.11 [95% CI: 0.10‐0.11]; P<0.0001). ROC curves for RI and MEWS are shown in Figure 1; the MEWS is subsumed by RI across the entire range. Further, paired comparisons at points of clinical importance are presented in Table 3 for LR+, LR, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. In the first pair of columns, MEWS=4 (typical trigger point for alarms) is matched to RI using sensitivity or LR; the corresponding point is RI=16, which generates twice the LR+ and reduces false alarms by 53%. In the second pair of columns, MEWS=4 is matched to RI using PPV or LR+; the corresponding point is RI=30, which captures 54% more of those patients who will die within 24 hours.

| Cut Points | MEWS=4 | RI=16a | MEWS=4 | RI=30b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Likelihood ratio, positive | 7.8 | 16.9 | 7.8c | 7.9c |

| Likelihood ratio, negative | 0.54c | 0.53c | 0.54 | 0.26 |

| Sensitivity | 49.8% | 48.9% | 49.8% | 76.8% |

| Specificity | 93.6% | 97.1% | 93.6% | 90.4% |

| Positive predictive value | 5.2% | 10.6% | 5.2% | 5.3% |

| Negative predictive value | 99.6% | 99.6% | 99.6% | 99.8% |

DISCUSSION

We have shown that a general acuity metric (RI) computed using data routinely entered into an EMR outperforms MEWS in identifying hospitalized patients likely to die within 24 hours. At similar sensitivity, RI yields an LR+ more than 2‐fold greater, at a value often considered conclusive. MEWS is derived using 4 vital signs and a neurologic assessment. Such a focus on vital signs may limit responsiveness to changes in acuity, especially during early clinical deterioration. Indeed, threshold breach tools may inadvertently induce a false sense of an individual patient's condition and safety.[12] The present findings suggest the performance of RI over MEWS may be due to inclusion of nursing assessments, laboratory test results, and heart rhythm. Relative contributions of each category are: vital signs (35%), nursing assessments (34%), and laboratory test results (31%). We found in previous work that failed nursing assessments strongly correlate with mortality,[13] as illustrated in Table 2 by sharp differences between patients dying within 24 hours and those who did not.

Sensitivity to detect early deterioration, especially when not evidenced by compromised vital signs, is crucial for acuity vigilance and preemptive interventions. Others[14] have demonstrated that our approach to longitudinal modeling of the acuity continuum is well positioned to investigate clinical pathophysiology preceding adverse events and to identify actionable trends in patients at high risk of complications and sepsis after colorectal operations. Future research may reveal both clinical and administrative advantages to having this real‐time acuity measure available for all patients during the entire hospital visit, with efficacy in applications beyond use as a trigger for EWS alarms.

Study limitations include retrospective design, single‐center cohort, no exclusion of expected hospital deaths, and EMR requirement. For MEWS, the Glasgow Coma Scale was mapped to A/V/P/U, which does not appear to affect results, as our c‐statistic is identical to the literature.[4] Any hospital with an EMR collects the data necessary for computation of RI values. The RI algorithms are available in software compatible with systems from numerous EMR manufacturers (eg, Epic, Cerner, McKesson, Siemens, AllScripts, Phillips).

The advent of the EMR in hospitals marries well with an EWS that leverages from additional data more information than is contained in vital signs, permitting complex numeric computations of acuity scores, a process simply not possible with paper systems. Further, the automatic recalculation of the score reduces the burden on clinicians, and broadens potential use over a wide range, from minute‐by‐minute recalculations when attached to sensors in the ICU, to comparative metrics of hospital performance, to nonclinical financial resource applications. This new information technology is guiding methods to achieve a significant performance increment over current EWS and may assist earlier detection of deterioration, providing a chance to avoid medical crises.[15]

Acknowledgements

The authors express their appreciation to Abington Memorial Hospital. Particular thanks are extended to Steven I. Rothman, MSEM, for extensive discussions and technical support. The authors thank Alan Solinger, PhD, for his assistance in reviewing the manuscript.

Disclosures: One author (RAS) declares no conflict of interest. Two authors (GDF, MJR) are employees and shareholders in PeraHealth, Inc. of Charlotte, North Carolina, a health information technology company that offers products utilizing the Rothman Index. All of the original research defining the Rothman Index was performed prior to the formation of the company and is now published in peer‐reviewed journals. The index is freely available to all qualified researchers and is currently installed at several major medical research centers and hospital systems. This present work is under the auspices and partly funded by an independent foundation, F.A.R. Institute of Sarasota, Florida. Early research defining the Rothman Index was funded by grants from Sarasota Memorial Healthcare Foundation and the Goldsmith Fund of Greenfield Foundation. Continuing research has been funded by the F.A.R. Institute.

- , , , . Validation of a modified Early Warning Score in medical admissions. QJM Mon J Assoc Physicians. 2001;94:521–526.

- , , . Monitoring vital signs using early warning scoring systems: a review of the literature. J Nurs Manag. 2011;19:311–330.

- , , , et al. A clinical deterioration prediction tool for internal medicine patients. Am J Med Qual. 2013;28:135–142.

- , , , . ViEWS—towards a national early warning score for detecting adult inpatient deterioration. Resuscitation. 2010;81:932–937.

- , , , , , . Early detection of impending physiologic deterioration among patients who are not in intensive care: development of predictive models using data from an automated electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2012;7:388–395.

- , , , et al. Predicting out of intensive care unit cardiopulmonary arrest or death using electronic medical record data. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2013;13:28.

- , , , The Braden Scale for predicting pressure sore risk. Nurs Res. 1987;36:205–210.

- , , . Development and validation of a continuous measure of patient condition using the electronic medical record. J Biomed Inform. 2013;46:837–848.

- , , , , . Identifying patients at increased risk for unplanned readmission. Med Care. 2013;51:761–766.

- , , . Comparison of consciousness level assessment in the poisoned patient using the alert/verbal/painful/unresponsive scale and the Glasgow Coma Scale. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44:108–113.

- , . Experimental Design. New York, NY: John Wiley 1950.

- , . Patterns of unexpected in‐hospital deaths: a root cause analysis. Patient Saf Surg. 2011;5:3.

- , , , . Clinical implications and validity of nursing assessments: a longitudinal measure of patient condition from analysis of the Electronic Medical Record. BMJ Open. 2012;2(4):pii: e000646.

- , , , . Automated analysis of electronic medical record data reflects the pathophysiology of operative complications. Surgery. 2013;154:918–926.

- , , Not getting better means getting worse—trends in Early Warning Scores suggest that there might only be a short time span to rescue those threatening to fall off a “physiological” cliff? Resuscitation. 2013;84:409–410.

Bedside calculation of early warning system (EWS) scores is standard practice in many hospitals to predict clinical deterioration. These systems were designed for periodic hand‐scoring, typically using a half‐dozen variables dominated by vital signs. Most derive from the Modified Early Warning Score (MEWS).[1, 2] Despite years of modification, EWSs have had only modest impact on outcomes.[3, 4] Major improvement is possible only by adding more information than is contained in vital signs. Thus, the next generation of EWSs must analyze electronic medical records (EMRs). Analysis would be performed by computer, displayed automatically, and updated whenever new data are entered into the EMR. Such systems could deliver timely, accurate, longitudinally trended acuity information that could aid in earlier detection of declining patient condition as well as improving sensitivity and specificity of EWS alarms.

Advancing this endeavor along with others,[5, 6] we previously published a patient acuity metric, the Rothman Index (RI), which automatically updates when asynchronous vital signs, laboratory test results, Braden Scale,[7] cardiac rhythm, and nursing assessments are entered into the EMR.[8] Our goal was to enable clinicians to visualize changes in acuity by simple line graphs personalized to each patient at any point in time across the trajectory of care. In our model validation studies,[8] we made no attempt to identify generalizable thresholds, though others[9] have defined decision cut points for RI in a nonemergent context. To examine decision support feasibility in an emergent context, and to compare RI with a general EWS standard, we compare the accuracy of the RI with the MEWS in predicting hospital death within 24 hours.

METHODS

Site Description and Ethics

The institutional review board of Abington Memorial Hospital (Abington, PA) approved collection of retrospective data obtained from their 665‐bed, regional referral center and teaching hospital. Handling of patient information complied with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 regulations.

Patient Inclusion

The analysis included all patients, aged 18 years or older, admitted from July 2009 through June 2010, when there were sufficient data in the EMR to compute the RI. Obstetric and psychiatric patients were excluded because nursing documentation is insufficient in this dataset.

Data Collection/Data Sources

Clinical variables were extracted from the EMR (AllScripts Sunrise Clinical Manager, Chicago, IL) by SQL query and placed into a database. RI[8] and MEWS[1] were computed according to published methods. Table 1 shows definitions of standards for each nursing assessment,[8] and Table 2 identifies all clinical variables employed for each system. Briefly, RI utilizes 26 variables related to clinical care and routinely available in the EMR. These include vital signs, laboratory results, cardiac rhythms, and nursing assessments. Excess risk associated with any value of a variable is defined as percent absolute increase in 1‐year mortality relative to minimum 1‐year mortality identified for that variable. Excess risk is summed on a linear scale to reflect cumulative risk for individual patients at any given time. RI was computed at every new observation during a patient visit, when input values were available. Laboratory results are included when measured, but after 24 hours their weighting is reduced by 50%, and after 48 hours they are excluded. Data input intervals were a function of institutional patient care protocols and physician orders. All observations during a patient's stay were included in the analysis, per the method of Prytherch et al.[4] Because data did not contain the simplified alert/voice/pain/unresponsive (A/V/P/U) score, computation of MEWS used appropriate mapping of the Glasgow Coma Scale.[10] A corresponding MEWS was calculated for each RI. The relationship between RI and MEWS is inverse. RI ranges from 91 to 100, with lower scores indicating increasing acuity. MEWS ranges from 0 to 14, with higher scores indicating increasing acuity.

| |

| Cardiac | Pulse regular, rate 60100 bpm, skin warm and dry. Blood pressure <140/90 and no symptoms of hypotension. |

| Food/nutrition | No difficulty with chewing, swallowing, or manual dexterity. Patient consuming >50% of daily diet ordered as observed or stated. |

| Gastrointestinal | Abdomen soft and nontender. Bowel sounds present. No nausea or vomiting. Continent. Bowel pattern normal as observed or stated. |

| Genitourinary | Voids without difficulty. Continent. Urine clear, yellow to amber as observed or stated. Urinary catheter patent if present. |

| Musculoskeletal | Independently able to move all extremities and perform functional activities as observed or stated (includes assistive devices). |

| Neurological | Alert and oriented to person, place, time, situation. Speech is coherent. |

| Peripheral‐vascular | Extremities are normal or pink and warm. Peripheral pulses palpable. Capillary refill <3 seconds. No edema, numbness or tingling. |

| Psychosocial | Behavior appropriate to situation. Expressed concerns and fears being addressed. Adequate support system. |

| Respiratory | Respiration 1224/minute at rest, quiet and regular. Bilateral breath sounds clear. Nail beds and mucous membranes pink. Sputum clear, if present. |

| Safety/fall risk | Safety/fall risk factors not present. Not a risk to self or others. |

| Skin/tissue | Skin clean, dry, and intact with no reddened areas. Patient is alert, cooperative and able to reposition self independently. Braden Scale >15. |

| Input Variable | A: Alive in 24 Hours, Mean (SD) | B: Dead Within 24 Hours, Mean (SD) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Diastolic blood pressure, mm Hg | 66.8 (13.5) | 56.6 (16.8) | <0.0001 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mm Hga | 127.3 (23.8) | 105.2 (29.4) | <0.0001 |

| Temperature, Fa | 98.2 (1.1) | 98.2 (2.0) | 0.1165 |

| Respiration, breaths per minutea | 20.1 (4.7) | 23.6 (9.1) | <0.0001 |

| Heart rate, bpma | 81.1 (16.5) | 96.9 (22.2) | <0.0001 |

| Pulse oximetry, % O2 saturation | 96.3 (3.3) | 93.8 (10.1) | <0.0001 |

| Creatinine, mg/dL | 1.2 (1.2) | 1.8 (1.5) | <0.0001 |

| Blood urea nitrogen, mg/dL | 23.9 (17.9) | 42.1 (26.4) | <0.0001 |

| Serum chloride, mmol/L | 104.3 (5.4) | 106.9 (9.7) | <0.0001 |

| Serum potassium, mmol/L | 4.2 (0.5) | 4.4 (0.8) | <0.0001 |

| Serum sodium, mmol/L | 139.0 (4.1) | 140.7 (8.5) | <0.0001 |

| Hemoglobin, gm/dL | 11.2 (2.1) | 10.6 (2.1) | <0.0001 |

| White blood cell count, 103 cell/L | 9.9 (6.3) | 15.0 (10.9) | <0.0001 |

| Braden Scale, total points | 17.7 (3.4) | 12.2 (3.1) | <0.0001 |

| NURSING ASSESSMENTS | A: Alive in 24 Hours and Failed Standard | B: Dead Within 24 Hours and Failed Standard | P Value |

| Neurological | 38.7% | 91.4% | <0.0001 |

| Genitourinary | 46.6% | 90.0% | <0.0001 |

| Respiratory | 55.6% | 89.0% | <0.0001 |

| Peripheral vascular | 54.1% | 86.9% | <0.0001 |

| Food | 28.3% | 80.6% | <0.0001 |

| Skin | 56.3% | 75.0% | <0.0001 |

| Gastrointestinal | 49.3% | 75.0% | <0.0001 |

| Musculoskeletal | 50.3% | 72.4% | <0.0001 |

| Cardiac | 30.4% | 59.8% | <0.0001 |

| Psychosocial | 24.6% | 40.9% | <0.0001 |

| Safety | 25.5% | 29.0% | <0.0001 |

| A/V/P/U scorea | 96.3/2.1/1.4/0.2% | 88.6/21.6/4.6/5.3% | <0.0001 |

| Sinus rhythm (absent)b | 34.9% | 53.3% | <0.0001 |

Outcome Ascertainment

In‐hospital death was determined by merging the date and time of discharge with clinical inputs from the hospital's EMR. Data points were judged to be within 24 hours of death if the timestamp of the data point collection was within 24 hours of the discharge time with expired as the discharge disposition.

Statistical Methods

Demographics and input variables from the 2 groups of observations, those who were within 24 hours of death and those who were not, were compared using a t test with a Cochran and Cox[11] approximation of the probability level of the approximate t statistic for unequal variances. Mean, standard deviation, and P values are reported. Discrimination of RI and MEWS to predict 24‐hour mortality was estimated using area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve (AUC), and null hypothesis was tested using 2. Sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value (PPV), negative predictive value (NPV), positive and negative likelihood ratios (LR+, LR) were computed. Analyses were performed with SAS 9.3 (procedures ttest, freq, logistic, nlmixed; SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Typically MEWS=4 triggers a protocol to increase level of assessment and/or care, often a transfer to the intensive care unit (ICU). We denoted the point on ROC curve where MEWS=4 and identified an RI point of similar LR and sensitivity to compare false alarm rate. Then we identified an RI point of similar LR+ for comparison of LR and sensitivity.

RESULTS

A total of 1,794,910 observations during 32,472 patient visits were included; 617 patients died (1.9%). Physiological characteristics for all input variables used by RI or MEWS are shown in Table 2, comparing observations taken within 24 hours of death to all other observations.

RI versus MEWS demonstrated superior discrimination of 24‐hour mortality (AUC was 0.93 [95% confidence interval {CI}: 0.92‐0.93] vs 0.82 [95% CI: 0.82‐0.83]; difference, 0.11 [95% CI: 0.10‐0.11]; P<0.0001). ROC curves for RI and MEWS are shown in Figure 1; the MEWS is subsumed by RI across the entire range. Further, paired comparisons at points of clinical importance are presented in Table 3 for LR+, LR, sensitivity, specificity, PPV, and NPV. In the first pair of columns, MEWS=4 (typical trigger point for alarms) is matched to RI using sensitivity or LR; the corresponding point is RI=16, which generates twice the LR+ and reduces false alarms by 53%. In the second pair of columns, MEWS=4 is matched to RI using PPV or LR+; the corresponding point is RI=30, which captures 54% more of those patients who will die within 24 hours.

| Cut Points | MEWS=4 | RI=16a | MEWS=4 | RI=30b |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Likelihood ratio, positive | 7.8 | 16.9 | 7.8c | 7.9c |

| Likelihood ratio, negative | 0.54c | 0.53c | 0.54 | 0.26 |

| Sensitivity | 49.8% | 48.9% | 49.8% | 76.8% |

| Specificity | 93.6% | 97.1% | 93.6% | 90.4% |

| Positive predictive value | 5.2% | 10.6% | 5.2% | 5.3% |

| Negative predictive value | 99.6% | 99.6% | 99.6% | 99.8% |

DISCUSSION

We have shown that a general acuity metric (RI) computed using data routinely entered into an EMR outperforms MEWS in identifying hospitalized patients likely to die within 24 hours. At similar sensitivity, RI yields an LR+ more than 2‐fold greater, at a value often considered conclusive. MEWS is derived using 4 vital signs and a neurologic assessment. Such a focus on vital signs may limit responsiveness to changes in acuity, especially during early clinical deterioration. Indeed, threshold breach tools may inadvertently induce a false sense of an individual patient's condition and safety.[12] The present findings suggest the performance of RI over MEWS may be due to inclusion of nursing assessments, laboratory test results, and heart rhythm. Relative contributions of each category are: vital signs (35%), nursing assessments (34%), and laboratory test results (31%). We found in previous work that failed nursing assessments strongly correlate with mortality,[13] as illustrated in Table 2 by sharp differences between patients dying within 24 hours and those who did not.

Sensitivity to detect early deterioration, especially when not evidenced by compromised vital signs, is crucial for acuity vigilance and preemptive interventions. Others[14] have demonstrated that our approach to longitudinal modeling of the acuity continuum is well positioned to investigate clinical pathophysiology preceding adverse events and to identify actionable trends in patients at high risk of complications and sepsis after colorectal operations. Future research may reveal both clinical and administrative advantages to having this real‐time acuity measure available for all patients during the entire hospital visit, with efficacy in applications beyond use as a trigger for EWS alarms.

Study limitations include retrospective design, single‐center cohort, no exclusion of expected hospital deaths, and EMR requirement. For MEWS, the Glasgow Coma Scale was mapped to A/V/P/U, which does not appear to affect results, as our c‐statistic is identical to the literature.[4] Any hospital with an EMR collects the data necessary for computation of RI values. The RI algorithms are available in software compatible with systems from numerous EMR manufacturers (eg, Epic, Cerner, McKesson, Siemens, AllScripts, Phillips).