User login

Sarcoidosis, complete heart block, and warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a young woman

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that affects 10-40 people per 100,000 in the United States and Europe, with an increased prevalence among blacks compared with whites.1 The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is variable. Sarcoidosis frequently involves the lungs and can have numerous extrapulmonary manifestations including skin, joint, cardiac, and eye lesions. We present a rare case of sarcoidosis with concurrent third-degree heart block and warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia and discuss possible mechanisms behind this presentation.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that affects 10-40 people per 100,000 in the United States and Europe, with an increased prevalence among blacks compared with whites.1 The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is variable. Sarcoidosis frequently involves the lungs and can have numerous extrapulmonary manifestations including skin, joint, cardiac, and eye lesions. We present a rare case of sarcoidosis with concurrent third-degree heart block and warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia and discuss possible mechanisms behind this presentation.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem granulomatous disease that affects 10-40 people per 100,000 in the United States and Europe, with an increased prevalence among blacks compared with whites.1 The clinical presentation of sarcoidosis is variable. Sarcoidosis frequently involves the lungs and can have numerous extrapulmonary manifestations including skin, joint, cardiac, and eye lesions. We present a rare case of sarcoidosis with concurrent third-degree heart block and warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia and discuss possible mechanisms behind this presentation.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Distant skin metastases as primary presentation of gastric cancer

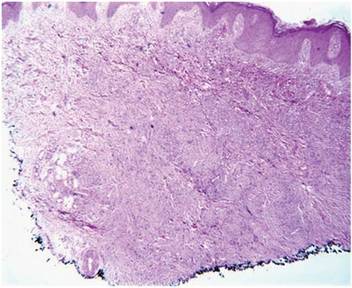

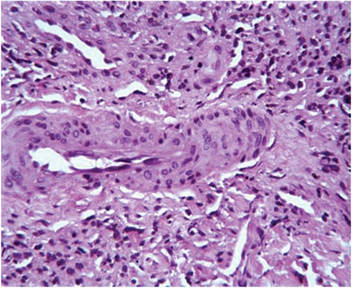

Distant gastric metastasis to the skin is uncommonly a presenting symptom, although nonspecific paraneoplastic syndromes with dermatologic manifestation including diffuse seborrheic keratoses (Leser-Trelat sign), tripe palms, and acanthosis nigricans have been described in the literature. We report here the case of a 49-year-old woman with gastric adenocarcinoma who presented with cutaneous metastasis as an initial symptom. In our case, metastatic skin lesions responded significantly to EOX chemotherapy (epirubicin+oxaliplatin+capecitabine) despite progression of systemic disease. In similar presentations, a high index of clinical suspicion and skin biopsy are important.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Distant gastric metastasis to the skin is uncommonly a presenting symptom, although nonspecific paraneoplastic syndromes with dermatologic manifestation including diffuse seborrheic keratoses (Leser-Trelat sign), tripe palms, and acanthosis nigricans have been described in the literature. We report here the case of a 49-year-old woman with gastric adenocarcinoma who presented with cutaneous metastasis as an initial symptom. In our case, metastatic skin lesions responded significantly to EOX chemotherapy (epirubicin+oxaliplatin+capecitabine) despite progression of systemic disease. In similar presentations, a high index of clinical suspicion and skin biopsy are important.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Distant gastric metastasis to the skin is uncommonly a presenting symptom, although nonspecific paraneoplastic syndromes with dermatologic manifestation including diffuse seborrheic keratoses (Leser-Trelat sign), tripe palms, and acanthosis nigricans have been described in the literature. We report here the case of a 49-year-old woman with gastric adenocarcinoma who presented with cutaneous metastasis as an initial symptom. In our case, metastatic skin lesions responded significantly to EOX chemotherapy (epirubicin+oxaliplatin+capecitabine) despite progression of systemic disease. In similar presentations, a high index of clinical suspicion and skin biopsy are important.

Click on the PDF icon at the top of this introduction to read the full article.

Total Hip Arthroplasty After Contralateral Hip Disarticulation: A Challenging “Simple Primary”

Patients with lower limb amputation have a high incidence of hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) in the residual limb as well as the contralateral limb. A radical surgery, hip disarticulation is generally performed in younger patients after malignancy or trauma. Compliance is poor with existing prostheses, resulting in increased dependency on and use of the remaining sound limb.

In this case report, a crutch-walking 51-year-old woman presented with severe left hip arthritis 25 years after a right hip disarticulation. She underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA), a challenging procedure in a person without a contralateral hip joint. The many complex technical considerations associated with her THA included precise perioperative planning, the selection of appropriate prostheses and bearing surfaces, and the preoperative and intraoperative assessment of limb length and offset. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented to our service with a 3-year history of debilitating left hip pain. Twenty-five years earlier, she had been diagnosed with synovial sarcoma of the right knee and underwent limb-sparing surgery, followed by a true hip disarticulation performed for local recurrence. After her surgery, she declined the use of a prosthesis and mobilized with the use of 2 crutches. She has remained otherwise healthy and active, and runs her own business, which involves some lifting and carrying of objects. During the 3 years prior to presentation, she developed progressively debilitating left hip and groin pain, which radiated to the medial aspect of her left knee. Her mobilization distance had reduced to a few hundred meters, and she experienced significant night pain, and start-up pain. Activity modification, weight loss, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication afforded no relief. She denied any back pain or radicular symptoms.

Clinical examination showed a well-healed scar and pristine stump under her right hemipelvis. Passive range of movement of her left hip was painful for all movements, reduced at flexion (90º) and internal (10º) and external rotation (5º). Examination of her left knee was normal, with a full range of movement and no joint-line tenderness. A high body mass index (>30) was noted. Radiographic imaging confirmed significant OA of the hip joint (Figure 1). Informed consent was obtained for THA. The implants were selected—an uncemented collared Corail Stem (DePuy, Warsaw, Indiana) with a stainless steel dual mobility (DM) Novae SunFit acetabular cup (Serf, Decines, France), with bearing components of ceramic on polyethylene. A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan of the left hip was performed (Figure 2) to aid templating, which was accomplished using plain films and CT images, with reference to the proximal femur for deciding level of neck cut, planning stem size, and optimizing length and offset, while determining cup size, depth, inclination, and height for the acetabular component.

Prior to surgery, the patient was positioned in the lateral decubitus position, using folded pillows under the medial aspect of her left proximal and distal thigh in lieu of her amputated limb. Pillows were secured to the table with elastic bandage tape. Standard pubic symphysis, lumbosacral, and midthoracic padded bolsters stabilized the pelvis in the normal fashion, with additional elastic bandage tape to further secure the pelvis brim to the table and reduce intraoperative motion. A posterior approach was used. A capsulotomy was performed with the hip in extension and slight abduction, with meticulous preservation of the capsule as the guide for the patient’s native length and offset. Reaming of the acetabulum was line to line, with insertion of an uncemented DM metal-back press-fit hydroxyapatite-coated shell placed in a standard fashion parallel with the transverse acetabular ligament, as described by Archbold and colleagues.1 The femur was sequentially reamed with broaches until press fit was achieved, and a calcar reamer was used to optimize interface with the collared implant. The surgeon’s standard 4 clinical tests were performed with trial implants after reduction to gauge hip tension, length, and offset. These tests are positive shuck test with hip and knee extension, lack of shuck in hip extension with knee flexion, lack of kick sign in hip extension and knee flexion, and palpation of gluteus medius belly to determine tension. Finally, with the hip returned to the extended and slightly abducted position, the capsule was tested for length and tension. The definitive stem implant was inserted, final testing with trial heads was repeated prior to definitive neck length and head selection, and final reduction was performed. A layered closure was performed, after generous washout. Pillows were taped together and positioned from the bed railing across the midline of the bed to prevent abduction, in the fashion of an abduction pillow.

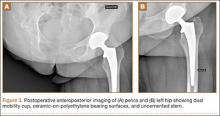

The patient was mobilized the day after surgery and permitted full weight-bearing. Recovery was uneventful, and the patient returned to work within 6 weeks of surgery after her scheduled appointment and radiographic examination (Figure 3). Ongoing regular clinical and radiologic surveillance are planned.

Discussion

Hip and knee OA in the residual limb is more common for amputees than for the general population.2,3 THA for OA in amputees has been reported after below-knee amputation in both the ipsilateral and the contralateral hip.4 A true hip disarticulation is a rarely performed radical surgical procedure, involving the removal of the entire femur, and is most often related to surgical oncologic treatment or combat-related injuries, both being more common in younger people. Like many patients who have had a hip disarticulation,5 our patient declined a prosthesis, finding the design cosmetically unappealing and uncomfortable, in favor of crutch-walking. This accelerated wear of the remaining hip, and is a sobering reminder of the high demand on the bearing surfaces of the implants after her procedure.

The implants chosen for this procedure are critical. We use implants which are proven and reliable. Our institution uses the Corail Stem, an uncemented collared stem with an Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP) 10A rating,6 widely used for THA.7 For the acetabulum, we chose the Novae SunFit, a modern version based on Bousquet’s 1976 DM design. The DM cup is a tripolar cup with a fixed porous-coated or cemented metal cup, which articulates with a large mobile polyethylene liner. A standard head in either metal or ceramic is inserted into this liner. The articulation between the head and the liner is constrained, while the articulation between the liner and the metal cup is unconstrained. This interposition of a mobile insert increases the effective head diameter, and the favorable head-neck ratio allows increased range of motion while avoiding early femoral neck impingement with a fixed liner or metal cup. A growing body of evidence indicates that DM cups reduce dislocation rates in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty and, when used with prudence, in selected tumor cases.8 A study of 1905 hips, using second-generation DM cups, reported cumulative survival rate of 98.6% at 12.2 years,9 with favorable outcomes compared with standard prostheses in the medium term for younger patients,10 and in the longer term,11 without increasing polyethylene wear.12

We use DM cups for 2 patient cohorts: first, for all patients older than 75 years because, in this age group, the risk of dislocation is higher than the risk of revision for wear-induced lysis; and second, in younger patients with any neuromuscular, cognitive, or mechanical risk factors that would excessively increase the risk of dislocation. This reflects the balance of risks in arthroplasty, with the ever-present trade-off between polyethylene-induced osteolysis and stability. Dislocation of the remaining sound limb for this young, active, agile patient would be a catastrophic complication. Given our patient’s risk factors for dislocation—female, an amputee with a high risk of falling, high body mass index, and lack of a contralateral limb to restrict adduction—the balance of risks favored hip stability over wear. We chose, therefore, a DM cup, using a ceramic-head-on-polyethylene-insert surface-bearing combination.

CT scanning is routinely performed in our institution to optimize preoperative templating. The preoperative CT images enable accurate planning, notably for the extramedullary reconstruction,13 and are used in addition to acetates and standard radiographs. This encourages preservation of acetabular bone stock by selecting the smallest suitable cup, reduces the risk of femoral fracture by giving an accurate prediction of the stem size, and ensures accuracy of restoring the patient’s offset and length. Although limb-length discrepancy was not an issue for this patient with a single sound limb, the sequalae of excessively increasing offset or length (eg, gluteus medius tendinopathy and trochanteric bursitis) would arguably be more debilitating than for someone who could offload weight to the “good hip.” For these reasons, marrying the preoperative templating with on-table testing with trial prostheses and restoring the native capsular tension is vital.

The importance of on-table positioning for proximal amputees undergoing hip arthroplasty has been highlighted.14 Lacking the normal bony constraints increases the risk of intraoperative on-table movement, which, in turn, risks reducing the accuracy of implant positioning. Crude limb-length checking using the contralateral knee is not possible. In addition, the lack of a contralateral hip joint causes a degree of compensatory pelvic tilt, which raises the option of increasing the coverage to compensate for obligate adduction during single-leg, crutch-walking gait. Lacking established guidelines to accommodate these variables, we inserted the cup in a standard fashion, at 45º, referencing acetabular version using the transverse acetabular ligament,1 and used the smallest stable cup after line-to-line reaming.

This case of THA in a young, crutch-walking patient with a contralateral true hip disarticulation highlights the importance of meticulous preoperative planning, implant selection appropriate for the patient in question, perioperative positioning, and the technical and operative challenges of restoring the patient’s normal hip architecture.

1. Archbold HA, Mockford B, Molloy D, McConway J, Ogonda L, Beverland D. The transverse acetabular ligament: an aid to orientation of the acetabular component during primary total hip replacement: a preliminary study of 1000 cases investigating postoperative stability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(7):883-886.

2. Kulkarni J, Adams J, Thomas E, Silman A. Association between amputation, arthritis and osteopenia in British male war veterans with major lower limb amputations. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12(4):348-353.

3. Struyf PA, van Heugten CM, Hitters MW, Smeets RJ. The prevalence of osteoarthritis of the intact hip and knee among traumatic leg amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(3):440-446.

4. Nejat EJ, Meyer A, Sánchez PM, Schaefer SH, Westrich GH. Total hip arthroplasty and rehabilitation in ambulatory lower extremity amputees--a case series. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:38-41.

5. Zaffer SM, Braddom RL, Conti A, Goff J, Bokma D. Total hip disarticulation prosthesis with suction socket: report of two cases. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78(2):160-162.

6. Lewis P. ODEP [Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel]. NHS Supply Chain website. http://www.supplychain.nhs.uk/odep. Accessed April 2, 2015.

7. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 8th Annual Report, 2011. National Joint Registry website. www.njrcentre.org.uk/NjrCentre/Portals/0/Documents/NJR%208th%20Annual%20Report%202011.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2015.

8. Grazioli A, Ek ET, Rüdiger HA. Biomechanical concept and clinical outcome of dual mobility cups. Int Orthop. 2012;36(12):2411-2418.

9. Massin P, Orain V, Philippot R, Farizon F, Fessy MH. Fixation failures of dual mobility cups: a mid-term study of 2601 hip replacements. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(7):1932-1940.

10. Epinette JA, Béracassat R, Tracol P, Pagazani G, Vandenbussche E. Are modern dual mobility cups a valuable option in reducing instability after primary hip arthroplasty, even in younger patients? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1323-1328.

11. Philippot R, Meucci JF, Boyer B, Farizon F. Modern dual-mobility cup implanted with an uncemented stem: about 100 cases with 12-year follow-up. Surg Technol Int. 2013;23:208-212.

12. Prudhon JL, Ferreira A, Verdier R. Dual mobility cup: dislocation rate and survivorship at ten years of follow-up. Int Orthop. 2013;37(12):2345-2350.

13. Sariali E, Mouttet A, Pasquier G, Durante E, Catone Y. Accuracy of reconstruction of the hip using computerised three-dimensional pre-operative planning and a cementless modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(13):333-340.

14. Bong MR, Kaplan KM, Jaffe WL. Total hip arthroplasty in a patient with contralateral hemipelvectomy. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):762-764.

Patients with lower limb amputation have a high incidence of hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) in the residual limb as well as the contralateral limb. A radical surgery, hip disarticulation is generally performed in younger patients after malignancy or trauma. Compliance is poor with existing prostheses, resulting in increased dependency on and use of the remaining sound limb.

In this case report, a crutch-walking 51-year-old woman presented with severe left hip arthritis 25 years after a right hip disarticulation. She underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA), a challenging procedure in a person without a contralateral hip joint. The many complex technical considerations associated with her THA included precise perioperative planning, the selection of appropriate prostheses and bearing surfaces, and the preoperative and intraoperative assessment of limb length and offset. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented to our service with a 3-year history of debilitating left hip pain. Twenty-five years earlier, she had been diagnosed with synovial sarcoma of the right knee and underwent limb-sparing surgery, followed by a true hip disarticulation performed for local recurrence. After her surgery, she declined the use of a prosthesis and mobilized with the use of 2 crutches. She has remained otherwise healthy and active, and runs her own business, which involves some lifting and carrying of objects. During the 3 years prior to presentation, she developed progressively debilitating left hip and groin pain, which radiated to the medial aspect of her left knee. Her mobilization distance had reduced to a few hundred meters, and she experienced significant night pain, and start-up pain. Activity modification, weight loss, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication afforded no relief. She denied any back pain or radicular symptoms.

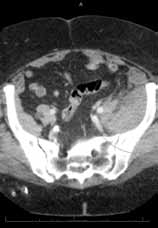

Clinical examination showed a well-healed scar and pristine stump under her right hemipelvis. Passive range of movement of her left hip was painful for all movements, reduced at flexion (90º) and internal (10º) and external rotation (5º). Examination of her left knee was normal, with a full range of movement and no joint-line tenderness. A high body mass index (>30) was noted. Radiographic imaging confirmed significant OA of the hip joint (Figure 1). Informed consent was obtained for THA. The implants were selected—an uncemented collared Corail Stem (DePuy, Warsaw, Indiana) with a stainless steel dual mobility (DM) Novae SunFit acetabular cup (Serf, Decines, France), with bearing components of ceramic on polyethylene. A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan of the left hip was performed (Figure 2) to aid templating, which was accomplished using plain films and CT images, with reference to the proximal femur for deciding level of neck cut, planning stem size, and optimizing length and offset, while determining cup size, depth, inclination, and height for the acetabular component.

Prior to surgery, the patient was positioned in the lateral decubitus position, using folded pillows under the medial aspect of her left proximal and distal thigh in lieu of her amputated limb. Pillows were secured to the table with elastic bandage tape. Standard pubic symphysis, lumbosacral, and midthoracic padded bolsters stabilized the pelvis in the normal fashion, with additional elastic bandage tape to further secure the pelvis brim to the table and reduce intraoperative motion. A posterior approach was used. A capsulotomy was performed with the hip in extension and slight abduction, with meticulous preservation of the capsule as the guide for the patient’s native length and offset. Reaming of the acetabulum was line to line, with insertion of an uncemented DM metal-back press-fit hydroxyapatite-coated shell placed in a standard fashion parallel with the transverse acetabular ligament, as described by Archbold and colleagues.1 The femur was sequentially reamed with broaches until press fit was achieved, and a calcar reamer was used to optimize interface with the collared implant. The surgeon’s standard 4 clinical tests were performed with trial implants after reduction to gauge hip tension, length, and offset. These tests are positive shuck test with hip and knee extension, lack of shuck in hip extension with knee flexion, lack of kick sign in hip extension and knee flexion, and palpation of gluteus medius belly to determine tension. Finally, with the hip returned to the extended and slightly abducted position, the capsule was tested for length and tension. The definitive stem implant was inserted, final testing with trial heads was repeated prior to definitive neck length and head selection, and final reduction was performed. A layered closure was performed, after generous washout. Pillows were taped together and positioned from the bed railing across the midline of the bed to prevent abduction, in the fashion of an abduction pillow.

The patient was mobilized the day after surgery and permitted full weight-bearing. Recovery was uneventful, and the patient returned to work within 6 weeks of surgery after her scheduled appointment and radiographic examination (Figure 3). Ongoing regular clinical and radiologic surveillance are planned.

Discussion

Hip and knee OA in the residual limb is more common for amputees than for the general population.2,3 THA for OA in amputees has been reported after below-knee amputation in both the ipsilateral and the contralateral hip.4 A true hip disarticulation is a rarely performed radical surgical procedure, involving the removal of the entire femur, and is most often related to surgical oncologic treatment or combat-related injuries, both being more common in younger people. Like many patients who have had a hip disarticulation,5 our patient declined a prosthesis, finding the design cosmetically unappealing and uncomfortable, in favor of crutch-walking. This accelerated wear of the remaining hip, and is a sobering reminder of the high demand on the bearing surfaces of the implants after her procedure.

The implants chosen for this procedure are critical. We use implants which are proven and reliable. Our institution uses the Corail Stem, an uncemented collared stem with an Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP) 10A rating,6 widely used for THA.7 For the acetabulum, we chose the Novae SunFit, a modern version based on Bousquet’s 1976 DM design. The DM cup is a tripolar cup with a fixed porous-coated or cemented metal cup, which articulates with a large mobile polyethylene liner. A standard head in either metal or ceramic is inserted into this liner. The articulation between the head and the liner is constrained, while the articulation between the liner and the metal cup is unconstrained. This interposition of a mobile insert increases the effective head diameter, and the favorable head-neck ratio allows increased range of motion while avoiding early femoral neck impingement with a fixed liner or metal cup. A growing body of evidence indicates that DM cups reduce dislocation rates in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty and, when used with prudence, in selected tumor cases.8 A study of 1905 hips, using second-generation DM cups, reported cumulative survival rate of 98.6% at 12.2 years,9 with favorable outcomes compared with standard prostheses in the medium term for younger patients,10 and in the longer term,11 without increasing polyethylene wear.12

We use DM cups for 2 patient cohorts: first, for all patients older than 75 years because, in this age group, the risk of dislocation is higher than the risk of revision for wear-induced lysis; and second, in younger patients with any neuromuscular, cognitive, or mechanical risk factors that would excessively increase the risk of dislocation. This reflects the balance of risks in arthroplasty, with the ever-present trade-off between polyethylene-induced osteolysis and stability. Dislocation of the remaining sound limb for this young, active, agile patient would be a catastrophic complication. Given our patient’s risk factors for dislocation—female, an amputee with a high risk of falling, high body mass index, and lack of a contralateral limb to restrict adduction—the balance of risks favored hip stability over wear. We chose, therefore, a DM cup, using a ceramic-head-on-polyethylene-insert surface-bearing combination.

CT scanning is routinely performed in our institution to optimize preoperative templating. The preoperative CT images enable accurate planning, notably for the extramedullary reconstruction,13 and are used in addition to acetates and standard radiographs. This encourages preservation of acetabular bone stock by selecting the smallest suitable cup, reduces the risk of femoral fracture by giving an accurate prediction of the stem size, and ensures accuracy of restoring the patient’s offset and length. Although limb-length discrepancy was not an issue for this patient with a single sound limb, the sequalae of excessively increasing offset or length (eg, gluteus medius tendinopathy and trochanteric bursitis) would arguably be more debilitating than for someone who could offload weight to the “good hip.” For these reasons, marrying the preoperative templating with on-table testing with trial prostheses and restoring the native capsular tension is vital.

The importance of on-table positioning for proximal amputees undergoing hip arthroplasty has been highlighted.14 Lacking the normal bony constraints increases the risk of intraoperative on-table movement, which, in turn, risks reducing the accuracy of implant positioning. Crude limb-length checking using the contralateral knee is not possible. In addition, the lack of a contralateral hip joint causes a degree of compensatory pelvic tilt, which raises the option of increasing the coverage to compensate for obligate adduction during single-leg, crutch-walking gait. Lacking established guidelines to accommodate these variables, we inserted the cup in a standard fashion, at 45º, referencing acetabular version using the transverse acetabular ligament,1 and used the smallest stable cup after line-to-line reaming.

This case of THA in a young, crutch-walking patient with a contralateral true hip disarticulation highlights the importance of meticulous preoperative planning, implant selection appropriate for the patient in question, perioperative positioning, and the technical and operative challenges of restoring the patient’s normal hip architecture.

Patients with lower limb amputation have a high incidence of hip and knee osteoarthritis (OA) in the residual limb as well as the contralateral limb. A radical surgery, hip disarticulation is generally performed in younger patients after malignancy or trauma. Compliance is poor with existing prostheses, resulting in increased dependency on and use of the remaining sound limb.

In this case report, a crutch-walking 51-year-old woman presented with severe left hip arthritis 25 years after a right hip disarticulation. She underwent total hip arthroplasty (THA), a challenging procedure in a person without a contralateral hip joint. The many complex technical considerations associated with her THA included precise perioperative planning, the selection of appropriate prostheses and bearing surfaces, and the preoperative and intraoperative assessment of limb length and offset. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

Case Report

A 51-year-old woman presented to our service with a 3-year history of debilitating left hip pain. Twenty-five years earlier, she had been diagnosed with synovial sarcoma of the right knee and underwent limb-sparing surgery, followed by a true hip disarticulation performed for local recurrence. After her surgery, she declined the use of a prosthesis and mobilized with the use of 2 crutches. She has remained otherwise healthy and active, and runs her own business, which involves some lifting and carrying of objects. During the 3 years prior to presentation, she developed progressively debilitating left hip and groin pain, which radiated to the medial aspect of her left knee. Her mobilization distance had reduced to a few hundred meters, and she experienced significant night pain, and start-up pain. Activity modification, weight loss, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medication afforded no relief. She denied any back pain or radicular symptoms.

Clinical examination showed a well-healed scar and pristine stump under her right hemipelvis. Passive range of movement of her left hip was painful for all movements, reduced at flexion (90º) and internal (10º) and external rotation (5º). Examination of her left knee was normal, with a full range of movement and no joint-line tenderness. A high body mass index (>30) was noted. Radiographic imaging confirmed significant OA of the hip joint (Figure 1). Informed consent was obtained for THA. The implants were selected—an uncemented collared Corail Stem (DePuy, Warsaw, Indiana) with a stainless steel dual mobility (DM) Novae SunFit acetabular cup (Serf, Decines, France), with bearing components of ceramic on polyethylene. A preoperative computed tomography (CT) scan of the left hip was performed (Figure 2) to aid templating, which was accomplished using plain films and CT images, with reference to the proximal femur for deciding level of neck cut, planning stem size, and optimizing length and offset, while determining cup size, depth, inclination, and height for the acetabular component.

Prior to surgery, the patient was positioned in the lateral decubitus position, using folded pillows under the medial aspect of her left proximal and distal thigh in lieu of her amputated limb. Pillows were secured to the table with elastic bandage tape. Standard pubic symphysis, lumbosacral, and midthoracic padded bolsters stabilized the pelvis in the normal fashion, with additional elastic bandage tape to further secure the pelvis brim to the table and reduce intraoperative motion. A posterior approach was used. A capsulotomy was performed with the hip in extension and slight abduction, with meticulous preservation of the capsule as the guide for the patient’s native length and offset. Reaming of the acetabulum was line to line, with insertion of an uncemented DM metal-back press-fit hydroxyapatite-coated shell placed in a standard fashion parallel with the transverse acetabular ligament, as described by Archbold and colleagues.1 The femur was sequentially reamed with broaches until press fit was achieved, and a calcar reamer was used to optimize interface with the collared implant. The surgeon’s standard 4 clinical tests were performed with trial implants after reduction to gauge hip tension, length, and offset. These tests are positive shuck test with hip and knee extension, lack of shuck in hip extension with knee flexion, lack of kick sign in hip extension and knee flexion, and palpation of gluteus medius belly to determine tension. Finally, with the hip returned to the extended and slightly abducted position, the capsule was tested for length and tension. The definitive stem implant was inserted, final testing with trial heads was repeated prior to definitive neck length and head selection, and final reduction was performed. A layered closure was performed, after generous washout. Pillows were taped together and positioned from the bed railing across the midline of the bed to prevent abduction, in the fashion of an abduction pillow.

The patient was mobilized the day after surgery and permitted full weight-bearing. Recovery was uneventful, and the patient returned to work within 6 weeks of surgery after her scheduled appointment and radiographic examination (Figure 3). Ongoing regular clinical and radiologic surveillance are planned.

Discussion

Hip and knee OA in the residual limb is more common for amputees than for the general population.2,3 THA for OA in amputees has been reported after below-knee amputation in both the ipsilateral and the contralateral hip.4 A true hip disarticulation is a rarely performed radical surgical procedure, involving the removal of the entire femur, and is most often related to surgical oncologic treatment or combat-related injuries, both being more common in younger people. Like many patients who have had a hip disarticulation,5 our patient declined a prosthesis, finding the design cosmetically unappealing and uncomfortable, in favor of crutch-walking. This accelerated wear of the remaining hip, and is a sobering reminder of the high demand on the bearing surfaces of the implants after her procedure.

The implants chosen for this procedure are critical. We use implants which are proven and reliable. Our institution uses the Corail Stem, an uncemented collared stem with an Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP) 10A rating,6 widely used for THA.7 For the acetabulum, we chose the Novae SunFit, a modern version based on Bousquet’s 1976 DM design. The DM cup is a tripolar cup with a fixed porous-coated or cemented metal cup, which articulates with a large mobile polyethylene liner. A standard head in either metal or ceramic is inserted into this liner. The articulation between the head and the liner is constrained, while the articulation between the liner and the metal cup is unconstrained. This interposition of a mobile insert increases the effective head diameter, and the favorable head-neck ratio allows increased range of motion while avoiding early femoral neck impingement with a fixed liner or metal cup. A growing body of evidence indicates that DM cups reduce dislocation rates in primary and revision total knee arthroplasty and, when used with prudence, in selected tumor cases.8 A study of 1905 hips, using second-generation DM cups, reported cumulative survival rate of 98.6% at 12.2 years,9 with favorable outcomes compared with standard prostheses in the medium term for younger patients,10 and in the longer term,11 without increasing polyethylene wear.12

We use DM cups for 2 patient cohorts: first, for all patients older than 75 years because, in this age group, the risk of dislocation is higher than the risk of revision for wear-induced lysis; and second, in younger patients with any neuromuscular, cognitive, or mechanical risk factors that would excessively increase the risk of dislocation. This reflects the balance of risks in arthroplasty, with the ever-present trade-off between polyethylene-induced osteolysis and stability. Dislocation of the remaining sound limb for this young, active, agile patient would be a catastrophic complication. Given our patient’s risk factors for dislocation—female, an amputee with a high risk of falling, high body mass index, and lack of a contralateral limb to restrict adduction—the balance of risks favored hip stability over wear. We chose, therefore, a DM cup, using a ceramic-head-on-polyethylene-insert surface-bearing combination.

CT scanning is routinely performed in our institution to optimize preoperative templating. The preoperative CT images enable accurate planning, notably for the extramedullary reconstruction,13 and are used in addition to acetates and standard radiographs. This encourages preservation of acetabular bone stock by selecting the smallest suitable cup, reduces the risk of femoral fracture by giving an accurate prediction of the stem size, and ensures accuracy of restoring the patient’s offset and length. Although limb-length discrepancy was not an issue for this patient with a single sound limb, the sequalae of excessively increasing offset or length (eg, gluteus medius tendinopathy and trochanteric bursitis) would arguably be more debilitating than for someone who could offload weight to the “good hip.” For these reasons, marrying the preoperative templating with on-table testing with trial prostheses and restoring the native capsular tension is vital.

The importance of on-table positioning for proximal amputees undergoing hip arthroplasty has been highlighted.14 Lacking the normal bony constraints increases the risk of intraoperative on-table movement, which, in turn, risks reducing the accuracy of implant positioning. Crude limb-length checking using the contralateral knee is not possible. In addition, the lack of a contralateral hip joint causes a degree of compensatory pelvic tilt, which raises the option of increasing the coverage to compensate for obligate adduction during single-leg, crutch-walking gait. Lacking established guidelines to accommodate these variables, we inserted the cup in a standard fashion, at 45º, referencing acetabular version using the transverse acetabular ligament,1 and used the smallest stable cup after line-to-line reaming.

This case of THA in a young, crutch-walking patient with a contralateral true hip disarticulation highlights the importance of meticulous preoperative planning, implant selection appropriate for the patient in question, perioperative positioning, and the technical and operative challenges of restoring the patient’s normal hip architecture.

1. Archbold HA, Mockford B, Molloy D, McConway J, Ogonda L, Beverland D. The transverse acetabular ligament: an aid to orientation of the acetabular component during primary total hip replacement: a preliminary study of 1000 cases investigating postoperative stability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(7):883-886.

2. Kulkarni J, Adams J, Thomas E, Silman A. Association between amputation, arthritis and osteopenia in British male war veterans with major lower limb amputations. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12(4):348-353.

3. Struyf PA, van Heugten CM, Hitters MW, Smeets RJ. The prevalence of osteoarthritis of the intact hip and knee among traumatic leg amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(3):440-446.

4. Nejat EJ, Meyer A, Sánchez PM, Schaefer SH, Westrich GH. Total hip arthroplasty and rehabilitation in ambulatory lower extremity amputees--a case series. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:38-41.

5. Zaffer SM, Braddom RL, Conti A, Goff J, Bokma D. Total hip disarticulation prosthesis with suction socket: report of two cases. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78(2):160-162.

6. Lewis P. ODEP [Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel]. NHS Supply Chain website. http://www.supplychain.nhs.uk/odep. Accessed April 2, 2015.

7. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 8th Annual Report, 2011. National Joint Registry website. www.njrcentre.org.uk/NjrCentre/Portals/0/Documents/NJR%208th%20Annual%20Report%202011.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2015.

8. Grazioli A, Ek ET, Rüdiger HA. Biomechanical concept and clinical outcome of dual mobility cups. Int Orthop. 2012;36(12):2411-2418.

9. Massin P, Orain V, Philippot R, Farizon F, Fessy MH. Fixation failures of dual mobility cups: a mid-term study of 2601 hip replacements. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(7):1932-1940.

10. Epinette JA, Béracassat R, Tracol P, Pagazani G, Vandenbussche E. Are modern dual mobility cups a valuable option in reducing instability after primary hip arthroplasty, even in younger patients? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1323-1328.

11. Philippot R, Meucci JF, Boyer B, Farizon F. Modern dual-mobility cup implanted with an uncemented stem: about 100 cases with 12-year follow-up. Surg Technol Int. 2013;23:208-212.

12. Prudhon JL, Ferreira A, Verdier R. Dual mobility cup: dislocation rate and survivorship at ten years of follow-up. Int Orthop. 2013;37(12):2345-2350.

13. Sariali E, Mouttet A, Pasquier G, Durante E, Catone Y. Accuracy of reconstruction of the hip using computerised three-dimensional pre-operative planning and a cementless modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(13):333-340.

14. Bong MR, Kaplan KM, Jaffe WL. Total hip arthroplasty in a patient with contralateral hemipelvectomy. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):762-764.

1. Archbold HA, Mockford B, Molloy D, McConway J, Ogonda L, Beverland D. The transverse acetabular ligament: an aid to orientation of the acetabular component during primary total hip replacement: a preliminary study of 1000 cases investigating postoperative stability. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88(7):883-886.

2. Kulkarni J, Adams J, Thomas E, Silman A. Association between amputation, arthritis and osteopenia in British male war veterans with major lower limb amputations. Clin Rehabil. 1998;12(4):348-353.

3. Struyf PA, van Heugten CM, Hitters MW, Smeets RJ. The prevalence of osteoarthritis of the intact hip and knee among traumatic leg amputees. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2009;90(3):440-446.

4. Nejat EJ, Meyer A, Sánchez PM, Schaefer SH, Westrich GH. Total hip arthroplasty and rehabilitation in ambulatory lower extremity amputees--a case series. Iowa Orthop J. 2005;25:38-41.

5. Zaffer SM, Braddom RL, Conti A, Goff J, Bokma D. Total hip disarticulation prosthesis with suction socket: report of two cases. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 1999;78(2):160-162.

6. Lewis P. ODEP [Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel]. NHS Supply Chain website. http://www.supplychain.nhs.uk/odep. Accessed April 2, 2015.

7. National Joint Registry for England and Wales. 8th Annual Report, 2011. National Joint Registry website. www.njrcentre.org.uk/NjrCentre/Portals/0/Documents/NJR%208th%20Annual%20Report%202011.pdf. Accessed April 2, 2015.

8. Grazioli A, Ek ET, Rüdiger HA. Biomechanical concept and clinical outcome of dual mobility cups. Int Orthop. 2012;36(12):2411-2418.

9. Massin P, Orain V, Philippot R, Farizon F, Fessy MH. Fixation failures of dual mobility cups: a mid-term study of 2601 hip replacements. Clin Orthop. 2012;470(7):1932-1940.

10. Epinette JA, Béracassat R, Tracol P, Pagazani G, Vandenbussche E. Are modern dual mobility cups a valuable option in reducing instability after primary hip arthroplasty, even in younger patients? J Arthroplasty. 2014;29(6):1323-1328.

11. Philippot R, Meucci JF, Boyer B, Farizon F. Modern dual-mobility cup implanted with an uncemented stem: about 100 cases with 12-year follow-up. Surg Technol Int. 2013;23:208-212.

12. Prudhon JL, Ferreira A, Verdier R. Dual mobility cup: dislocation rate and survivorship at ten years of follow-up. Int Orthop. 2013;37(12):2345-2350.

13. Sariali E, Mouttet A, Pasquier G, Durante E, Catone Y. Accuracy of reconstruction of the hip using computerised three-dimensional pre-operative planning and a cementless modular neck. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2009;91(13):333-340.

14. Bong MR, Kaplan KM, Jaffe WL. Total hip arthroplasty in a patient with contralateral hemipelvectomy. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21(5):762-764.

Cholinergic Urticaria With Anaphylaxis: Hazardous Duty of a Deployed US Marine

Cholinergic urticaria (CU) is a condition that primarily affects young adults. It can severely limit their activity levels and therefore job performance. Rarely, this condition can be associated with anaphylaxis, requiring a high index of suspicion by the clinician to ensure proper evaluation and treatment to prevent future respiratory compromise. We present the case of a 27-year-old US Marine with CU and anaphylaxis confirmed by a water challenge test in a warm bath.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 27-year-old white man who was a US Marine presented with a concern of hives that appeared during strenuous exercise when he was deployed in Afghanistan approximately 1 year earlier. He initially began to experience urticarial lesions when taking warm showers with concomitant shortness of breath and wheezing. He reported no history of hives or asthma. Despite using diphenhydramine as needed to control symptoms for several months, he noted that the episodes of urticaria occurred with light-headedness, dizziness, or vomiting even with mild physical activity or common daily activities. Symptoms typically would resolve 30 to 90 minutes after he stopped exercising or cooled off. Over the course of approximately 1 year, the patient was prescribed a variety of sedating and nonsedating antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, doxepin, cetirizine, loratadine, fexofenadine, montelukast) by primary care while deployed, some of which mitigated his symptoms during warm showers and outdoor activities but not during exercise.

After returning from his deployment, the patient was initially referred to the dermatology department. No lesions were noted on physical examination. Based on his history, he was advised to avoid strenuous exercise and activity. During subsequent visits to dermatology an exercise challenge test was considered but not initiated due to lack of facilities to provide appropriate airway monitoring. The allergy department was consulted and the patient also was prescribed leukotriene receptor antagonists in addition to the antihistamines he was already taking. It was decided that a water challenge test in a warm bath would be performed in lieu of an exercise challenge to confirm a diagnosis of CU versus CU with anaphylaxis. If the patient did not have a reaction to the water challenge test, an exercise challenge would be offered.

After stopping treatment with antihistamines and leukotriene receptor antagonists for 1 week, a water challenge test was performed. A heparin lock was placed in the untested left arm for intravenous access. The right arm was immersed in a warm bath for 5 minutes without incident. After confirming no reaction, the arm was immersed for another 5 minutes, after which the patient reported flushing, warmth, and itching with visible 2- to 3-mm urticarial lesions on the back (Figure, A) and chest (Figure, B). The arm was subsequently removed from the water. No lesions were noted on either of the arms. The patient developed a cough after removing the arm from the water and his peak expiratory flow rate dropped from 520 to 440 L/min. After 5 minutes his peak expiratory flow rate recovered to 500 L/min and the coughing subsided. He also reported mild nausea and a headache. He was rapidly cooled with ice to abort any further reaction. An epinephrine autoinjector was on hand but was not used due to rapidly resolving symptoms. The diagnosis of CU with anaphylaxis was confirmed.

Erythematous eruption with 2- to 3-mm urticarial lesions on the back (A) and chest (B). |

Comment

Urticaria is a heterogeneous group of disorders that includes both cholinergic and exercise-induced variants. Cholinergic urticaria affects as many as 11.2% of young adults aged 15 to 35 years, with a peak incidence of 20% between 26 and 28 years of age.1 Clinical presentation consists of wheals (central swelling with peripheral erythema) that are 1 to 5 mm in diameter2 with associated itching/burning that typically resolves within 1 to 24 hours. Cholinergic urticaria is the result of a rise in core body temperature independent of exercise status; it is distinguished from exercise-induced urticaria, which occurs in response to vigorous exercise and is not related to a rise in body temperature.3 In particular, these forms of urticaria can severely impact the lives and careers of young servicemen and servicewomen who are routinely deployed to warm environments.

A provocation test is recommended by Magerl et al4 in patients with a suspected diagnosis of CU. First, an exercise challenge test using a bicycle, treadmill, or similar equipment is recommended, with the patient exercising for 15 minutes beyond the start of sweating. Readings for urticaria are made immediately following the test and 10 minutes later. If the test is positive, a water challenge test in a hot bath (42°C) is then recommended for 15 minutes beyond an increase of 1°C in baseline core body temperature.4 One study demonstrated that 43% (13/30) of patients with CU experienced bronchial hyperresponsiveness on methacholine challenge testing.5 These findings suggest a possible utility in testing CU patients for potential disease-related respiratory compromise. A practical limitation of this study was that it did not examine a link between bronchial hyperresponsiveness and anaphylaxis during cholinergic urticarial flares. An exercise challenge test was not performed in our patient due to a history of wheezing and shortness of breath with exercise; instead we went directly to the water challenge test. We felt that limited immersion in the water (ie, only 1 arm) further minimized the risk for anaphylaxis compared with full-body immersion.

Any activity that raises core body temperature in a patient with CU can induce onset of lesions. One case report described a patient who experienced symptoms while undergoing hemodialysis, which resolved when the dialysate temperature was decreased from the normal 36.5°C to 35°C.6 However, most cases are triggered by daily activities or work. The mainstay of treatment of CU is nonsedating antihistamines. Cetirizine has demonstrated particular efficacy.7 For unresponsive cases, treatments include scopolamine butylbromide8,9; ketotifen10; combinations of cetirizine, montelukast, and propanolol11; and danazol.12

Conclusion

Cholinergic urticaria is mostly prevalent among young adults, with highest incidence in the late 20s. Active duty servicemen and servicewomen are among those who are at the greatest risk for developing CU, especially those deployed to tropical environments. Frequently, CU is associated with bronchial hyperresponsiveness and also can be associated with anaphylaxis, as was seen in our patient. Care must be taken before provocative tests are conducted in these patients and should be done in a controlled environment in which airway compromise can be properly assessed and treated if anaphylaxis were to occur.

1. Zuberbier T, Althaus C, Chantraine-Hess S, et al. Prevalence of cholinergic urticaria in young adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:978-981.

2. Kontou-Fili K, Borici-Mazi R, Kapp A, et al. Physical urticaria: classification and diagnostic guidelines. an EAACI position paper. Allergy. 1997;52:504-513.

3. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al; Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417-1426.

4. Magerl M, Borzova E, Giménez-Arnau A, et al; EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV. The definition and diagnostic testing of physical and cholinergic urticarias—EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus panel recommendations [published online ahead of print September 30, 2009]. Allergy. 2009;64:1715-1721.

5. Petalas K, Kontou-Fili K, Gratziou C. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with cholinergic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:416-421.

6. Morel V, Hauser C. Generalized cholinergic heat urticaria induced by hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2006;70:230.

7. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Burtin B, et al. Efficacy of cetirizine in cholinergic urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:147-149.

8. Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with scopolamine butylbromide. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:850.

9. Ujiie H, Shimizu T, Natsuga K, et al. Severe cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with scopolamine butylbromide in addition to antihistamines. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:588-589.

10. McClean SP, Arreaza EE, Lett-Brown MA, et al. Refractory cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with ketotifen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83:738-741.

11. Feinberg JH, Toner CB. Successful treatment of disabling cholinergic urticaria. Mil Med. 2008;173:217-220.

12. La Shell MS, England RW. Severe refractory cholinergic urticaria treated with danazol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:664-667.

Cholinergic urticaria (CU) is a condition that primarily affects young adults. It can severely limit their activity levels and therefore job performance. Rarely, this condition can be associated with anaphylaxis, requiring a high index of suspicion by the clinician to ensure proper evaluation and treatment to prevent future respiratory compromise. We present the case of a 27-year-old US Marine with CU and anaphylaxis confirmed by a water challenge test in a warm bath.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 27-year-old white man who was a US Marine presented with a concern of hives that appeared during strenuous exercise when he was deployed in Afghanistan approximately 1 year earlier. He initially began to experience urticarial lesions when taking warm showers with concomitant shortness of breath and wheezing. He reported no history of hives or asthma. Despite using diphenhydramine as needed to control symptoms for several months, he noted that the episodes of urticaria occurred with light-headedness, dizziness, or vomiting even with mild physical activity or common daily activities. Symptoms typically would resolve 30 to 90 minutes after he stopped exercising or cooled off. Over the course of approximately 1 year, the patient was prescribed a variety of sedating and nonsedating antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, doxepin, cetirizine, loratadine, fexofenadine, montelukast) by primary care while deployed, some of which mitigated his symptoms during warm showers and outdoor activities but not during exercise.

After returning from his deployment, the patient was initially referred to the dermatology department. No lesions were noted on physical examination. Based on his history, he was advised to avoid strenuous exercise and activity. During subsequent visits to dermatology an exercise challenge test was considered but not initiated due to lack of facilities to provide appropriate airway monitoring. The allergy department was consulted and the patient also was prescribed leukotriene receptor antagonists in addition to the antihistamines he was already taking. It was decided that a water challenge test in a warm bath would be performed in lieu of an exercise challenge to confirm a diagnosis of CU versus CU with anaphylaxis. If the patient did not have a reaction to the water challenge test, an exercise challenge would be offered.

After stopping treatment with antihistamines and leukotriene receptor antagonists for 1 week, a water challenge test was performed. A heparin lock was placed in the untested left arm for intravenous access. The right arm was immersed in a warm bath for 5 minutes without incident. After confirming no reaction, the arm was immersed for another 5 minutes, after which the patient reported flushing, warmth, and itching with visible 2- to 3-mm urticarial lesions on the back (Figure, A) and chest (Figure, B). The arm was subsequently removed from the water. No lesions were noted on either of the arms. The patient developed a cough after removing the arm from the water and his peak expiratory flow rate dropped from 520 to 440 L/min. After 5 minutes his peak expiratory flow rate recovered to 500 L/min and the coughing subsided. He also reported mild nausea and a headache. He was rapidly cooled with ice to abort any further reaction. An epinephrine autoinjector was on hand but was not used due to rapidly resolving symptoms. The diagnosis of CU with anaphylaxis was confirmed.

Erythematous eruption with 2- to 3-mm urticarial lesions on the back (A) and chest (B). |

Comment

Urticaria is a heterogeneous group of disorders that includes both cholinergic and exercise-induced variants. Cholinergic urticaria affects as many as 11.2% of young adults aged 15 to 35 years, with a peak incidence of 20% between 26 and 28 years of age.1 Clinical presentation consists of wheals (central swelling with peripheral erythema) that are 1 to 5 mm in diameter2 with associated itching/burning that typically resolves within 1 to 24 hours. Cholinergic urticaria is the result of a rise in core body temperature independent of exercise status; it is distinguished from exercise-induced urticaria, which occurs in response to vigorous exercise and is not related to a rise in body temperature.3 In particular, these forms of urticaria can severely impact the lives and careers of young servicemen and servicewomen who are routinely deployed to warm environments.

A provocation test is recommended by Magerl et al4 in patients with a suspected diagnosis of CU. First, an exercise challenge test using a bicycle, treadmill, or similar equipment is recommended, with the patient exercising for 15 minutes beyond the start of sweating. Readings for urticaria are made immediately following the test and 10 minutes later. If the test is positive, a water challenge test in a hot bath (42°C) is then recommended for 15 minutes beyond an increase of 1°C in baseline core body temperature.4 One study demonstrated that 43% (13/30) of patients with CU experienced bronchial hyperresponsiveness on methacholine challenge testing.5 These findings suggest a possible utility in testing CU patients for potential disease-related respiratory compromise. A practical limitation of this study was that it did not examine a link between bronchial hyperresponsiveness and anaphylaxis during cholinergic urticarial flares. An exercise challenge test was not performed in our patient due to a history of wheezing and shortness of breath with exercise; instead we went directly to the water challenge test. We felt that limited immersion in the water (ie, only 1 arm) further minimized the risk for anaphylaxis compared with full-body immersion.

Any activity that raises core body temperature in a patient with CU can induce onset of lesions. One case report described a patient who experienced symptoms while undergoing hemodialysis, which resolved when the dialysate temperature was decreased from the normal 36.5°C to 35°C.6 However, most cases are triggered by daily activities or work. The mainstay of treatment of CU is nonsedating antihistamines. Cetirizine has demonstrated particular efficacy.7 For unresponsive cases, treatments include scopolamine butylbromide8,9; ketotifen10; combinations of cetirizine, montelukast, and propanolol11; and danazol.12

Conclusion

Cholinergic urticaria is mostly prevalent among young adults, with highest incidence in the late 20s. Active duty servicemen and servicewomen are among those who are at the greatest risk for developing CU, especially those deployed to tropical environments. Frequently, CU is associated with bronchial hyperresponsiveness and also can be associated with anaphylaxis, as was seen in our patient. Care must be taken before provocative tests are conducted in these patients and should be done in a controlled environment in which airway compromise can be properly assessed and treated if anaphylaxis were to occur.

Cholinergic urticaria (CU) is a condition that primarily affects young adults. It can severely limit their activity levels and therefore job performance. Rarely, this condition can be associated with anaphylaxis, requiring a high index of suspicion by the clinician to ensure proper evaluation and treatment to prevent future respiratory compromise. We present the case of a 27-year-old US Marine with CU and anaphylaxis confirmed by a water challenge test in a warm bath.

Case Report

An otherwise healthy 27-year-old white man who was a US Marine presented with a concern of hives that appeared during strenuous exercise when he was deployed in Afghanistan approximately 1 year earlier. He initially began to experience urticarial lesions when taking warm showers with concomitant shortness of breath and wheezing. He reported no history of hives or asthma. Despite using diphenhydramine as needed to control symptoms for several months, he noted that the episodes of urticaria occurred with light-headedness, dizziness, or vomiting even with mild physical activity or common daily activities. Symptoms typically would resolve 30 to 90 minutes after he stopped exercising or cooled off. Over the course of approximately 1 year, the patient was prescribed a variety of sedating and nonsedating antihistamines (eg, diphenhydramine, hydroxyzine, doxepin, cetirizine, loratadine, fexofenadine, montelukast) by primary care while deployed, some of which mitigated his symptoms during warm showers and outdoor activities but not during exercise.

After returning from his deployment, the patient was initially referred to the dermatology department. No lesions were noted on physical examination. Based on his history, he was advised to avoid strenuous exercise and activity. During subsequent visits to dermatology an exercise challenge test was considered but not initiated due to lack of facilities to provide appropriate airway monitoring. The allergy department was consulted and the patient also was prescribed leukotriene receptor antagonists in addition to the antihistamines he was already taking. It was decided that a water challenge test in a warm bath would be performed in lieu of an exercise challenge to confirm a diagnosis of CU versus CU with anaphylaxis. If the patient did not have a reaction to the water challenge test, an exercise challenge would be offered.

After stopping treatment with antihistamines and leukotriene receptor antagonists for 1 week, a water challenge test was performed. A heparin lock was placed in the untested left arm for intravenous access. The right arm was immersed in a warm bath for 5 minutes without incident. After confirming no reaction, the arm was immersed for another 5 minutes, after which the patient reported flushing, warmth, and itching with visible 2- to 3-mm urticarial lesions on the back (Figure, A) and chest (Figure, B). The arm was subsequently removed from the water. No lesions were noted on either of the arms. The patient developed a cough after removing the arm from the water and his peak expiratory flow rate dropped from 520 to 440 L/min. After 5 minutes his peak expiratory flow rate recovered to 500 L/min and the coughing subsided. He also reported mild nausea and a headache. He was rapidly cooled with ice to abort any further reaction. An epinephrine autoinjector was on hand but was not used due to rapidly resolving symptoms. The diagnosis of CU with anaphylaxis was confirmed.

Erythematous eruption with 2- to 3-mm urticarial lesions on the back (A) and chest (B). |

Comment

Urticaria is a heterogeneous group of disorders that includes both cholinergic and exercise-induced variants. Cholinergic urticaria affects as many as 11.2% of young adults aged 15 to 35 years, with a peak incidence of 20% between 26 and 28 years of age.1 Clinical presentation consists of wheals (central swelling with peripheral erythema) that are 1 to 5 mm in diameter2 with associated itching/burning that typically resolves within 1 to 24 hours. Cholinergic urticaria is the result of a rise in core body temperature independent of exercise status; it is distinguished from exercise-induced urticaria, which occurs in response to vigorous exercise and is not related to a rise in body temperature.3 In particular, these forms of urticaria can severely impact the lives and careers of young servicemen and servicewomen who are routinely deployed to warm environments.

A provocation test is recommended by Magerl et al4 in patients with a suspected diagnosis of CU. First, an exercise challenge test using a bicycle, treadmill, or similar equipment is recommended, with the patient exercising for 15 minutes beyond the start of sweating. Readings for urticaria are made immediately following the test and 10 minutes later. If the test is positive, a water challenge test in a hot bath (42°C) is then recommended for 15 minutes beyond an increase of 1°C in baseline core body temperature.4 One study demonstrated that 43% (13/30) of patients with CU experienced bronchial hyperresponsiveness on methacholine challenge testing.5 These findings suggest a possible utility in testing CU patients for potential disease-related respiratory compromise. A practical limitation of this study was that it did not examine a link between bronchial hyperresponsiveness and anaphylaxis during cholinergic urticarial flares. An exercise challenge test was not performed in our patient due to a history of wheezing and shortness of breath with exercise; instead we went directly to the water challenge test. We felt that limited immersion in the water (ie, only 1 arm) further minimized the risk for anaphylaxis compared with full-body immersion.

Any activity that raises core body temperature in a patient with CU can induce onset of lesions. One case report described a patient who experienced symptoms while undergoing hemodialysis, which resolved when the dialysate temperature was decreased from the normal 36.5°C to 35°C.6 However, most cases are triggered by daily activities or work. The mainstay of treatment of CU is nonsedating antihistamines. Cetirizine has demonstrated particular efficacy.7 For unresponsive cases, treatments include scopolamine butylbromide8,9; ketotifen10; combinations of cetirizine, montelukast, and propanolol11; and danazol.12

Conclusion

Cholinergic urticaria is mostly prevalent among young adults, with highest incidence in the late 20s. Active duty servicemen and servicewomen are among those who are at the greatest risk for developing CU, especially those deployed to tropical environments. Frequently, CU is associated with bronchial hyperresponsiveness and also can be associated with anaphylaxis, as was seen in our patient. Care must be taken before provocative tests are conducted in these patients and should be done in a controlled environment in which airway compromise can be properly assessed and treated if anaphylaxis were to occur.

1. Zuberbier T, Althaus C, Chantraine-Hess S, et al. Prevalence of cholinergic urticaria in young adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:978-981.

2. Kontou-Fili K, Borici-Mazi R, Kapp A, et al. Physical urticaria: classification and diagnostic guidelines. an EAACI position paper. Allergy. 1997;52:504-513.

3. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al; Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417-1426.

4. Magerl M, Borzova E, Giménez-Arnau A, et al; EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV. The definition and diagnostic testing of physical and cholinergic urticarias—EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus panel recommendations [published online ahead of print September 30, 2009]. Allergy. 2009;64:1715-1721.

5. Petalas K, Kontou-Fili K, Gratziou C. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with cholinergic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:416-421.

6. Morel V, Hauser C. Generalized cholinergic heat urticaria induced by hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2006;70:230.

7. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Burtin B, et al. Efficacy of cetirizine in cholinergic urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:147-149.

8. Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with scopolamine butylbromide. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:850.

9. Ujiie H, Shimizu T, Natsuga K, et al. Severe cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with scopolamine butylbromide in addition to antihistamines. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:588-589.

10. McClean SP, Arreaza EE, Lett-Brown MA, et al. Refractory cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with ketotifen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83:738-741.

11. Feinberg JH, Toner CB. Successful treatment of disabling cholinergic urticaria. Mil Med. 2008;173:217-220.

12. La Shell MS, England RW. Severe refractory cholinergic urticaria treated with danazol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:664-667.

1. Zuberbier T, Althaus C, Chantraine-Hess S, et al. Prevalence of cholinergic urticaria in young adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1994;31:978-981.

2. Kontou-Fili K, Borici-Mazi R, Kapp A, et al. Physical urticaria: classification and diagnostic guidelines. an EAACI position paper. Allergy. 1997;52:504-513.

3. Zuberbier T, Asero R, Bindslev-Jensen C, et al; Dermatology Section of the European Academy of Allergology and Immunology; Global Allergy and Asthma European Network; European Dermatology Forum; World Allergy Organization. EAACI/GA(2)LEN/EDF/WAO guideline: definition, classification and diagnosis of urticaria. Allergy. 2009;64:1417-1426.

4. Magerl M, Borzova E, Giménez-Arnau A, et al; EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV. The definition and diagnostic testing of physical and cholinergic urticarias—EAACI/GA2LEN/EDF/UNEV consensus panel recommendations [published online ahead of print September 30, 2009]. Allergy. 2009;64:1715-1721.

5. Petalas K, Kontou-Fili K, Gratziou C. Bronchial hyperresponsiveness in patients with cholinergic urticaria. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2009;102:416-421.

6. Morel V, Hauser C. Generalized cholinergic heat urticaria induced by hemodialysis. Kidney Int. 2006;70:230.

7. Zuberbier T, Aberer W, Burtin B, et al. Efficacy of cetirizine in cholinergic urticaria. Acta Derm Venereol. 1995;75:147-149.

8. Tsunemi Y, Ihn H, Saeki H, et al. Cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with scopolamine butylbromide. Int J Dermatol. 2003;42:850.

9. Ujiie H, Shimizu T, Natsuga K, et al. Severe cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with scopolamine butylbromide in addition to antihistamines. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2006;31:588-589.

10. McClean SP, Arreaza EE, Lett-Brown MA, et al. Refractory cholinergic urticaria successfully treated with ketotifen. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1989;83:738-741.

11. Feinberg JH, Toner CB. Successful treatment of disabling cholinergic urticaria. Mil Med. 2008;173:217-220.

12. La Shell MS, England RW. Severe refractory cholinergic urticaria treated with danazol. J Drugs Dermatol. 2006;5:664-667.

Practice Points

- Cholinergic urticaria can be a life-threatening condition and should be diagnosed in a controlled clinical setting where airway can be maintained.

- Cholinergic urticaria can be a profession-limiting condition, affecting people whose work involves exposure to heat or physical activity such as members of the military.

Diagnosis and Treatment of Leprosy Type 1 (Reversal) Reaction

Leprosy is a chronic granulomatous infection caused by the organism Mycobacterium leprae that primarily affects the skin and peripheral nerves.1 The organism is thought to be transmitted from person to person via the nasal secretions of infected individuals and is known to have a long incubation period, lasting 2 to 6 years.2 Leprosy has several distinct clinical presentations depending on the host immune response to the infection.3 Treatment typically involves antimicrobials (eg, clofazimine, dapsone, rifampin). Once treatment has begun, an important aspect of patient care is the recognition and treatment of leprosy reactions. Leprosy reactions are acute inflammatory complications that typically occur during the treatment course but also may occur in untreated disease. Type 1 (reversal) and type 2 (erythema nodosum leprosum) reactions are the 2 main types of leprosy reactions, which may affect 30% to 50% of all leprosy patients combined.4 Vasculonecrotic reactions (Lucio leprosy phenomenon) in leprosy are much less common.

We report a case of a 44-year-old man who repeatedly developed physical findings consistent with type 1 reactions after undergoing multiple treatments for leprosy. A discussion of leprosy, as well as its clinical manifestations, treatment options, and management of reversal reactions, also will be provided.

Case Report

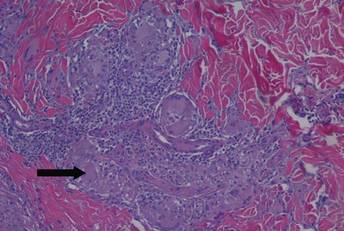

A healthy 44-year-old man presented with a several month history of elevated, erythematous to yellow, anesthetic papules and plaques on the trunk (Figure 1). No other systemic symptoms were noted. Biopsies of multiple skin lesions showed noncaseating granulomas with preferential extension in a perineural pattern and tracking along the arrector pili muscle (Figure 2). The cutaneous nerves appeared to be slightly enlarged. The patient reported a history of living in Louisiana and growing up with armadillos in the backyard, often filling the holes that they dug, but he denied having direct contact with or eating armadillos. In childhood, the patient traveled across the border to Mexico a few times but only for the day. He spent several months in the Middle East (ie, Diego Garcia, Saudi Arabia) more than 10 years prior to presentation, and he spent 2 weeks in Korea approximately 2 years prior to presentation but did not travel off the US air base. He had never traveled to South America or Africa. The clinical and histopathologic findings were consistent with Hansen disease (leprosy) and were determined to be tuberculoid in type given the limited clinical presentation, tuberculoid granulomas on biopsy, and no visible organisms on histopathologic analysis.

|

The patient initially was started on rifampin but was unable to tolerate treatment due to subsequent hepatotoxicity. He then was transitioned to a dual regimen of clofazimine and dapsone, which he tolerated well for the full 12-month treatment course. The cutaneous lesions quickly resolved after starting treatment, leaving a fine “cigarette paper–like” atrophy of the skin. After 12 months, it was subsequently presumed that the patient’s disease had been cured and treatment was stopped.

Nine months later, the patient noted new papules and plaques beginning to reappear in the truncal region. He was seen in clinic and a repeat biopsy was conducted, revealing perineural inflammation and noncaseating granulomas that were similar to the initial biopsies. Fite staining showed no acid-fast bacilli. Polymerase chain reaction was negative for M leprae. Nevertheless, a diagnosis of recurrent leprosy was made based on the patient’s clinical manifestations. He initially was started on dapsone, minocycline, and levofloxacin but was unable to tolerate the minocycline due to subsequent vertigo. After 1 month of treatment with dapsone and levofloxacin, the patient was clinically clear of all skin lesions and a repeat 12-month course of treatment was completed.

One year after completing the second 12-month treatment course, the patient again developed recurrent, indurated, erythematous papules and plaques on the trunk. Expert consultation from the National Hansen’s Disease (Leprosy) Program determined that the patient was experiencing a type 1 (reversal) reaction, not recurrent disease. Intralesional triamcinolone acetonide (10 mg/cc) was subsequently administered within the individual lesions. After a few treatments, the patient experienced notable regression of the lesions and has since been free of recurrent reactions (Figures 3 and 4).

|

Comment

Mycobacterium leprae

Mycobacterium leprae is an obligate intracellular bacillus that is confined to humans, armadillos of specific locales, and sphagnum moss. It is an acid-fast bacillus that is microscopically indistinguishable from other mycobacteria and is best detected on Fite staining of tissue sections.5

Mycobacterium leprae has 2 unique properties. It is thermolabile, growing best at 27°C to 30°C. Given its thermal sensitivity, M leprae has a preference for peripheral tissues including the skin, peripheral nerves, and the mucosa of the upper airways. It also may affect other tissues such as the bones and some viscera.2 The other unique quality of M leprae is its slow replication, with a generation time of 12 to 14 days. Because of the slow growth of M leprae, the incubation period in humans typically ranges from 2 to 6 years, with the minimal incubation period being 2 to 3 years and the maximum incubation period being as long as 40 years.6

Perhaps the greatest challenge to investigators is the fact that M leprae cannot be grown via normal laboratory culture methods. A possible explanation is reductive evolution, which may have led to a number of inactivated (pseudogenes) in the genome of this organism. In fact, close genetic examination of this organism has led to the conclusion that only half of the genome of M leprae is actually functional. This gene decay may explain the specific host tropism of M leprae as well as the inability to culture this organism in a laboratory setting.5,7

Incidence

Leprosy is primarily a disease of developing countries. More than 80% of the world’s cases of leprosy occur in India, China, Myanmar, Indonesia, Brazil, Nigeria, Madagascar, and Nepal. Although Africa has the highest prevalence, Asia is known to have had the most cases.5 In contrast, leprosy is largely absent from Europe, Canada, and the United States, except as imported cases or scattered cases along the southern border of the United States. In the United States, for example, fewer than 100 cases of leprosy are diagnosed each year, with almost all cases identified in immigrants from endemic areas.6

The global burden of leprosy, defined as the number of new cases detected annually, is stabilizing, which can be attributed in large part to the World Health Organization’s commitment in 1991 to eliminate leprosy as a public health concern by the year 2000 by implementing worldwide treatment regimes. Elimination was defined as a prevalence of less than 1 case per 10,000 persons.8 By 2012, only 3 of 122 countries had not achieved this standard, which is evidence of the program’s success.9

Disease Transmission