User login

More on AI-generated content

In his recent editorial (“A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT?”

Sara Hartley, MD

Berkeley, California

I just read the “guest editorial” generated by ChatGPT. Thank you for this article. Although this is truly an amazing advancement in artificial intelligence (AI), I feel this guest editorial was very basic. It did not read like scientific writing. It read more like it was written at an 11th- or 12th-grade level, though I am fully aware that the question was simple, and thus the answer was not very deep. I can’t deny that if I had been tested, chances are good I would have fallen among the 32% of my peers who would not have recognized it as AI. I appreciate that you (and your team) are working on a protocol regarding how to include content generated by or with the help of AI. God knows if (most likely, when) people with evil minds will use AI to spread false information that may dispute the accredited scientific data and research that guide the medical world and many other fields. I wonder if AI can serve as a search engine that is better or easier to use than PubMed (for example) and the other services we use for research and learning.

Alex Mustachi, PMHNP-BC

Suffern, New York

I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed reading your recent editorial on AI and scientific writing. Sharing the 4 AI-generated “articles” with readers (“For artificial intelligence, the future is finally here,”

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

Continue to: The AI-generated samples...

The Al-generated samples were fascinating. As far as I superficially noted, the spelling, grammar, and punctuation were correct. That is better than one gets from most student compositions. However, the articles were completely lacking in depth or apparent insight. The article on anosognosia mentioned it can be present in up to 50% of cases of schizophrenia. In my experience, it is present in approximately 99.9% of cases. It clearly did not consider if anosognosia is also present in alcoholics, codependents, abusers, or people with bizarre political beliefs. But I guess the “intelligence” wasn’t asked that. The other samples also show shallow thinking and repetitive wording—pretty much like my high school junior compositions.

Maybe an appropriate use for AI is a task such as evaluating suicide notes. AI’s success causes one to feel nonplussed. Much more disconcerting was a recent news article that reported AI made up nonexistent references to a professor’s alleged sexual harassment, and then generated citations to its own made-up reference.1 That is indeed frightening new territory. How does one fight against a machine to clear their own name?

Linda Miller, NP

Harrisonburg, Virginia

References

1. Verma P, Oremus W. ChatGPT invented a sexual harassment scandal and named a real law prof as the accused. The Washington Post. April 5, 2023. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/04/05/chatgpt-lies/

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for your latest thought-provoking articles on AI. Time and again you provide the profession with cutting-edge, relevant food for thought. Caveat emptor, indeed.

Lawrence E. Cormier, MD

Denver, Colorado

Continue to: We read with interest...

We read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial that invited readers to share their take on the quality of an AI-generated writing sample. I (MZP) was a computational neuroscience major at Columbia University and was accepted to medical school in 2022 at age 19. I identify with the character traits common among many young tech entrepreneurs driving the AI revolution—social awkwardness; discomfort with subjective emotions; restricted areas of interest; algorithmic thinking; strict, naive idealism; and an obsession with data. To gain a deeper understanding of Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT), we analyzed a 2.5-hour interview that MIT research scientist Lex Fridman conducted with Altman.1 As a result, we began to discern why AI-generated text feels so stiff and bland compared to the superior fluidity and expressiveness of human communication. As of now, the creation is a reflection of its creator.

Generally speaking, computer scientists are not warm and fuzzy types. Hence, ChatGPT strives to be neutral, accurate, and objective compared to more biased and fallible humans, and, consequently, its language lacks the emotive flair we have come to relish in normal human interactions. In the interview, Altman discusses several solutions that will soon raise the quality of ChatGPT’s currently deficient emotional quotient to approximate its superior IQ. Altruistically, Altman has opened ChatGPT to all, so we can freely interact and utilize its potential to increase our productivity exponentially. As a result, ChatGPT interfaces with millions of humans through RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback), which makes each iteration more in tune with our sensibilities.2 Another initiative Altman is undertaking is to depart his Silicon Valley bubble for a road trip to interact with “regular people” and gain a better sense of how to make ChatGPT more user-friendly.1

What’s so saddening about Dr. Nasrallah’s homework assignment is that he is asking us to evaluate with our mature adult standards an article that was written at the emotional stage of a child in early high school. But our hubris and complacency are entirely unfounded because ChatGPT is learning much faster than we ever could, and it will quickly surpass us all as it continues to evolve.

It is also quite disconcerting to hear how Altman is naively relying upon governmental regulation and corporate responsibility to manage the potential misuse of future artificial general intelligence for social, economic, and political control and upheaval. We know well the harmful effects of the internet and social media, particularly on our youth, yet our laws still lag far behind the fact that these technological innovations are simultaneously enhancing our knowledge while destroying our souls. As custodians of our world, dedicated to promoting and preserving mental well-being, we cannot wait much longer to intervene in properly parenting AI along its wisest developmental trajectory before it is too late.

Maxwell Zachary Price, BA

Nutley, New Jersey

Richard Louis Price, MD

New York, New York

References

1. Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI. Lex Fridman Podcast #367. March 25, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_Guz73e6fw

2. Heikkilä M. How OpenAI is trying to make ChatGPT safer and less biased. MIT Technology Review. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/21/1068893/how-openai-is-trying-to-make-chatgpt-safer-and-less-biased/

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

In his recent editorial (“A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT?”

Sara Hartley, MD

Berkeley, California

I just read the “guest editorial” generated by ChatGPT. Thank you for this article. Although this is truly an amazing advancement in artificial intelligence (AI), I feel this guest editorial was very basic. It did not read like scientific writing. It read more like it was written at an 11th- or 12th-grade level, though I am fully aware that the question was simple, and thus the answer was not very deep. I can’t deny that if I had been tested, chances are good I would have fallen among the 32% of my peers who would not have recognized it as AI. I appreciate that you (and your team) are working on a protocol regarding how to include content generated by or with the help of AI. God knows if (most likely, when) people with evil minds will use AI to spread false information that may dispute the accredited scientific data and research that guide the medical world and many other fields. I wonder if AI can serve as a search engine that is better or easier to use than PubMed (for example) and the other services we use for research and learning.

Alex Mustachi, PMHNP-BC

Suffern, New York

I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed reading your recent editorial on AI and scientific writing. Sharing the 4 AI-generated “articles” with readers (“For artificial intelligence, the future is finally here,”

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

Continue to: The AI-generated samples...

The Al-generated samples were fascinating. As far as I superficially noted, the spelling, grammar, and punctuation were correct. That is better than one gets from most student compositions. However, the articles were completely lacking in depth or apparent insight. The article on anosognosia mentioned it can be present in up to 50% of cases of schizophrenia. In my experience, it is present in approximately 99.9% of cases. It clearly did not consider if anosognosia is also present in alcoholics, codependents, abusers, or people with bizarre political beliefs. But I guess the “intelligence” wasn’t asked that. The other samples also show shallow thinking and repetitive wording—pretty much like my high school junior compositions.

Maybe an appropriate use for AI is a task such as evaluating suicide notes. AI’s success causes one to feel nonplussed. Much more disconcerting was a recent news article that reported AI made up nonexistent references to a professor’s alleged sexual harassment, and then generated citations to its own made-up reference.1 That is indeed frightening new territory. How does one fight against a machine to clear their own name?

Linda Miller, NP

Harrisonburg, Virginia

References

1. Verma P, Oremus W. ChatGPT invented a sexual harassment scandal and named a real law prof as the accused. The Washington Post. April 5, 2023. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/04/05/chatgpt-lies/

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for your latest thought-provoking articles on AI. Time and again you provide the profession with cutting-edge, relevant food for thought. Caveat emptor, indeed.

Lawrence E. Cormier, MD

Denver, Colorado

Continue to: We read with interest...

We read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial that invited readers to share their take on the quality of an AI-generated writing sample. I (MZP) was a computational neuroscience major at Columbia University and was accepted to medical school in 2022 at age 19. I identify with the character traits common among many young tech entrepreneurs driving the AI revolution—social awkwardness; discomfort with subjective emotions; restricted areas of interest; algorithmic thinking; strict, naive idealism; and an obsession with data. To gain a deeper understanding of Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT), we analyzed a 2.5-hour interview that MIT research scientist Lex Fridman conducted with Altman.1 As a result, we began to discern why AI-generated text feels so stiff and bland compared to the superior fluidity and expressiveness of human communication. As of now, the creation is a reflection of its creator.

Generally speaking, computer scientists are not warm and fuzzy types. Hence, ChatGPT strives to be neutral, accurate, and objective compared to more biased and fallible humans, and, consequently, its language lacks the emotive flair we have come to relish in normal human interactions. In the interview, Altman discusses several solutions that will soon raise the quality of ChatGPT’s currently deficient emotional quotient to approximate its superior IQ. Altruistically, Altman has opened ChatGPT to all, so we can freely interact and utilize its potential to increase our productivity exponentially. As a result, ChatGPT interfaces with millions of humans through RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback), which makes each iteration more in tune with our sensibilities.2 Another initiative Altman is undertaking is to depart his Silicon Valley bubble for a road trip to interact with “regular people” and gain a better sense of how to make ChatGPT more user-friendly.1

What’s so saddening about Dr. Nasrallah’s homework assignment is that he is asking us to evaluate with our mature adult standards an article that was written at the emotional stage of a child in early high school. But our hubris and complacency are entirely unfounded because ChatGPT is learning much faster than we ever could, and it will quickly surpass us all as it continues to evolve.

It is also quite disconcerting to hear how Altman is naively relying upon governmental regulation and corporate responsibility to manage the potential misuse of future artificial general intelligence for social, economic, and political control and upheaval. We know well the harmful effects of the internet and social media, particularly on our youth, yet our laws still lag far behind the fact that these technological innovations are simultaneously enhancing our knowledge while destroying our souls. As custodians of our world, dedicated to promoting and preserving mental well-being, we cannot wait much longer to intervene in properly parenting AI along its wisest developmental trajectory before it is too late.

Maxwell Zachary Price, BA

Nutley, New Jersey

Richard Louis Price, MD

New York, New York

References

1. Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI. Lex Fridman Podcast #367. March 25, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_Guz73e6fw

2. Heikkilä M. How OpenAI is trying to make ChatGPT safer and less biased. MIT Technology Review. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/21/1068893/how-openai-is-trying-to-make-chatgpt-safer-and-less-biased/

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

In his recent editorial (“A ‘guest editorial’ … generated by ChatGPT?”

Sara Hartley, MD

Berkeley, California

I just read the “guest editorial” generated by ChatGPT. Thank you for this article. Although this is truly an amazing advancement in artificial intelligence (AI), I feel this guest editorial was very basic. It did not read like scientific writing. It read more like it was written at an 11th- or 12th-grade level, though I am fully aware that the question was simple, and thus the answer was not very deep. I can’t deny that if I had been tested, chances are good I would have fallen among the 32% of my peers who would not have recognized it as AI. I appreciate that you (and your team) are working on a protocol regarding how to include content generated by or with the help of AI. God knows if (most likely, when) people with evil minds will use AI to spread false information that may dispute the accredited scientific data and research that guide the medical world and many other fields. I wonder if AI can serve as a search engine that is better or easier to use than PubMed (for example) and the other services we use for research and learning.

Alex Mustachi, PMHNP-BC

Suffern, New York

I wanted to let you know how much I enjoyed reading your recent editorial on AI and scientific writing. Sharing the 4 AI-generated “articles” with readers (“For artificial intelligence, the future is finally here,”

Martha Sajatovic, MD

Cleveland, Ohio

Continue to: The AI-generated samples...

The Al-generated samples were fascinating. As far as I superficially noted, the spelling, grammar, and punctuation were correct. That is better than one gets from most student compositions. However, the articles were completely lacking in depth or apparent insight. The article on anosognosia mentioned it can be present in up to 50% of cases of schizophrenia. In my experience, it is present in approximately 99.9% of cases. It clearly did not consider if anosognosia is also present in alcoholics, codependents, abusers, or people with bizarre political beliefs. But I guess the “intelligence” wasn’t asked that. The other samples also show shallow thinking and repetitive wording—pretty much like my high school junior compositions.

Maybe an appropriate use for AI is a task such as evaluating suicide notes. AI’s success causes one to feel nonplussed. Much more disconcerting was a recent news article that reported AI made up nonexistent references to a professor’s alleged sexual harassment, and then generated citations to its own made-up reference.1 That is indeed frightening new territory. How does one fight against a machine to clear their own name?

Linda Miller, NP

Harrisonburg, Virginia

References

1. Verma P, Oremus W. ChatGPT invented a sexual harassment scandal and named a real law prof as the accused. The Washington Post. April 5, 2023. Accessed May 8, 2023. https://www.washingtonpost.com/technology/2023/04/05/chatgpt-lies/

Thank you, Dr. Nasrallah, for your latest thought-provoking articles on AI. Time and again you provide the profession with cutting-edge, relevant food for thought. Caveat emptor, indeed.

Lawrence E. Cormier, MD

Denver, Colorado

Continue to: We read with interest...

We read with interest Dr. Nasrallah’s editorial that invited readers to share their take on the quality of an AI-generated writing sample. I (MZP) was a computational neuroscience major at Columbia University and was accepted to medical school in 2022 at age 19. I identify with the character traits common among many young tech entrepreneurs driving the AI revolution—social awkwardness; discomfort with subjective emotions; restricted areas of interest; algorithmic thinking; strict, naive idealism; and an obsession with data. To gain a deeper understanding of Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI (the company that created ChatGPT), we analyzed a 2.5-hour interview that MIT research scientist Lex Fridman conducted with Altman.1 As a result, we began to discern why AI-generated text feels so stiff and bland compared to the superior fluidity and expressiveness of human communication. As of now, the creation is a reflection of its creator.

Generally speaking, computer scientists are not warm and fuzzy types. Hence, ChatGPT strives to be neutral, accurate, and objective compared to more biased and fallible humans, and, consequently, its language lacks the emotive flair we have come to relish in normal human interactions. In the interview, Altman discusses several solutions that will soon raise the quality of ChatGPT’s currently deficient emotional quotient to approximate its superior IQ. Altruistically, Altman has opened ChatGPT to all, so we can freely interact and utilize its potential to increase our productivity exponentially. As a result, ChatGPT interfaces with millions of humans through RLHF (reinforcement learning from human feedback), which makes each iteration more in tune with our sensibilities.2 Another initiative Altman is undertaking is to depart his Silicon Valley bubble for a road trip to interact with “regular people” and gain a better sense of how to make ChatGPT more user-friendly.1

What’s so saddening about Dr. Nasrallah’s homework assignment is that he is asking us to evaluate with our mature adult standards an article that was written at the emotional stage of a child in early high school. But our hubris and complacency are entirely unfounded because ChatGPT is learning much faster than we ever could, and it will quickly surpass us all as it continues to evolve.

It is also quite disconcerting to hear how Altman is naively relying upon governmental regulation and corporate responsibility to manage the potential misuse of future artificial general intelligence for social, economic, and political control and upheaval. We know well the harmful effects of the internet and social media, particularly on our youth, yet our laws still lag far behind the fact that these technological innovations are simultaneously enhancing our knowledge while destroying our souls. As custodians of our world, dedicated to promoting and preserving mental well-being, we cannot wait much longer to intervene in properly parenting AI along its wisest developmental trajectory before it is too late.

Maxwell Zachary Price, BA

Nutley, New Jersey

Richard Louis Price, MD

New York, New York

References

1. Sam Altman: OpenAI CEO on GPT-4, ChatGPT, and the Future of AI. Lex Fridman Podcast #367. March 25, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=L_Guz73e6fw

2. Heikkilä M. How OpenAI is trying to make ChatGPT safer and less biased. MIT Technology Review. Published February 21, 2023. Accessed April 5, 2023. https://www.technologyreview.com/2023/02/21/1068893/how-openai-is-trying-to-make-chatgpt-safer-and-less-biased/

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in their letters, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Membership priorities shape the AGA advocacy agenda

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

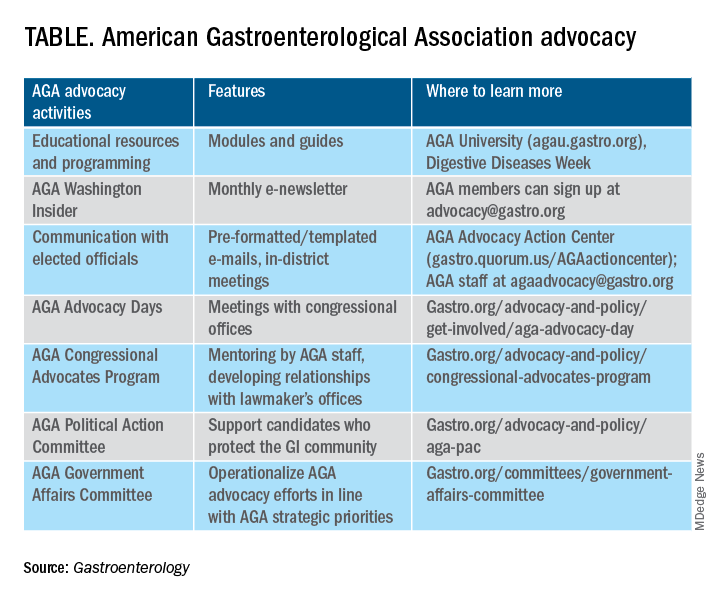

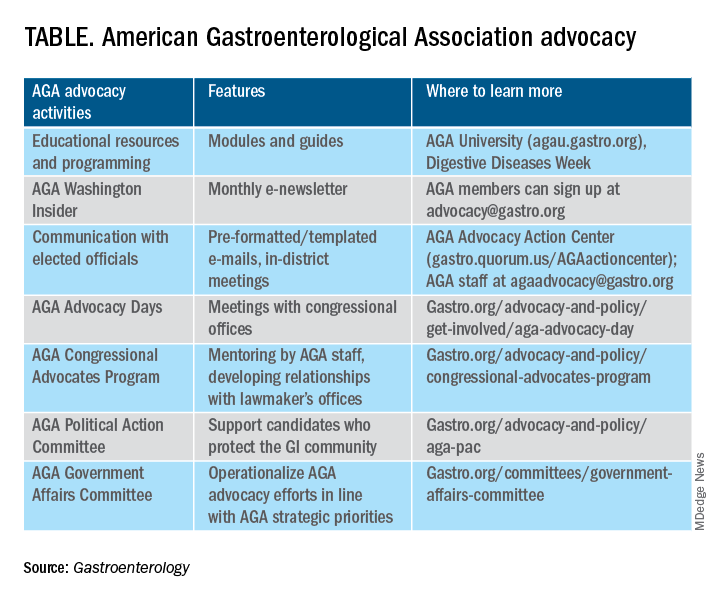

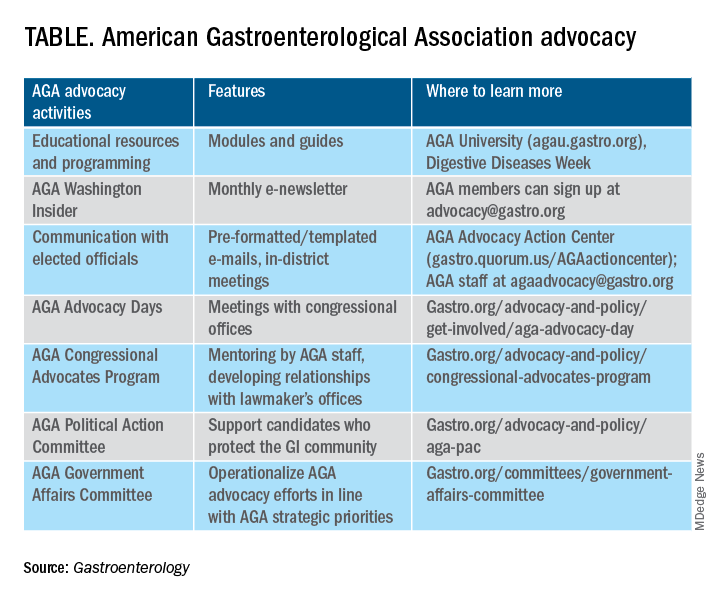

AGA’s advocacy work

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

Here, we present key highlights from the survey findings and share opportunities for members to engage in GI advocacy.

AGA advocacy has contributed to significant recent successes that include lowering the average-risk of colorectal cancer screening age from 50 to 45 years, phasing out cost-sharing burdens associated with polypectomy at screening colonoscopy, encouraging federal support to focus on GI cancer disparities, ensuring coverage for telehealth services, expanding colonoscopy coverage after positive noninvasive colorectal cancer screening tests, and mitigating scheduled cuts in Medicare reimbursement for GI services.

Despite these important successes, the GI community faces significant challenges that include persisting GI health disparities; declines in reimbursement and increased prior authorization burdens for GI procedures and clinic visits, limited research funding to address the burden of GI disease, climate change, provider burnout, and increasing administrative burdens (such as insurance prior authorizations and step therapy policies.

The AGA sought to better understand policy priorities of the GI community by disseminating a 34-question policy priority survey to AGA members in December 2022. A total of 251 members responded to the survey with career stage and primary practice setting varying among respondents (Figure 1). The AGA vetted and selected 10 health policy issues of highest interest with 95% of survey respondents agreeing these 10 selected topics covered the top priority issues impacting gastroenterology (Figure 2).

From these 10 policy issues, members were asked to identify the top 5 issues that AGA advocacy efforts should address.

The issues most frequently identified included reducing administrative burdens and patient delays in care because of increased prior authorizations (78%), ensuring fair reimbursement for GI providers (68%), reducing insurance-initiated switching of patient treatments for nonmedical reasons (58%), maintaining coverage of video and telephone evaluation and management visits (55%), and reducing delays in clinical care resulting from step therapy protocols (53%).

Other important issues included ensuring patients with pre-existing conditions have access to essential benefits and quality specialty care (43%); protecting providers from medical licensing restrictions and liability to deliver care across state lines (35%); addressing Medicare Quality Payment Program reporting requirements and lack of specialty advanced payment models (27%); increasing funding for GI health disparities (24%); and, increasing federal research funding to ensure greater opportunities for diverse early career investigators (20%).

Most problematic burdens

Survey respondents identified insurer prior authorization and step therapy burdens as especially problematic. 93% of respondents described the impact of prior authorization on their practices as “significantly burdensome” (61%) or “somewhat burdensome” (32%).

About 95% noted that prior authorization restrictions have impacted patient access to clinically appropriate treatments and patient clinical outcomes “significantly” (56%) or “somewhat” (39%) negatively. 84% described the burdens associated with prior authorization policies as having increased “significantly” (60%) or “somewhat” (24%) over the last 5 years.

Likewise, step therapy protocols were perceived by 84% of respondents as burdensome; by 88% as negatively impactful on patient access to clinically appropriate treatments; and, by 88% as negatively impactful on patient clinical outcomes.

About 84% of respondents noted increases in the frequency of nonmedical switching and dosing restrictions over the last 5 years, with 90% perceiving negative impacts on patient clinical outcomes. 73% of respondents reported increased burdens associated with compliance in the Medicare QPP over the last 5 years.

AGA’s advocacy work

About 76% of respondents were interested in learning more about the AGA’s advocacy work. We presented some of the various opportunities and resources for members to engage with and contribute to AGA advocacy efforts (see pie chart). Based on the tremendous efforts and dedication of AGA staff, some of these opportunities include educational modules on AGA University, DDW programming, the AGA Washington Insider monthly policy newsletter, preformatted communications available through the AGA Advocacy Action Center, participation in AGA Advocacy Days or the AGA Congressional Advocates Program, service on the AGA Government Affairs Committee, and/or contributing to the AGA Political Action Committee.

Overall, the survey respondents illustrate the diversity and enthusiasm of AGA membership. Importantly, 95% of AGA members responding to the survey agreed these 10 selected policy issues are inclusive of the current top priority issues of the GI community. Amidst an ever-shifting health care landscape, we – the AGA community – must remain vigilant and adaptable to best address expected and unexpected changes and challenges to our patients and colleagues. In this respect, we should encourage constructive communication and dialogue between AGA membership, leadership, other issue stakeholders, government representatives and entities, and payers.

Amit Patel, MD, is a gastroenterologist and associate professor of medicine at Duke University and the Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center, both in Durham, N.C. He serves on the editorial review board of Gastroenterology. Rotonya McCants Carr, MD, is the Cyrus E. Rubin Chair and division head of gastroenterology at the University of Washington, Seattle. Both Dr. Patel and Dr. Carr serve on the AGA Government Affairs Committee. The contents of this article do not represent the views of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

Reference

Patel A et al. Gastroenterology. 2023 May;164[6]:847-50.

The power of mentorship

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

In a 2018 JAMA Viewpoint, Dr. Vineet Chopra, a former colleague of mine at the University of Michigan (now chair of medicine at the University of Colorado) and colleagues wrote about four archetypes of mentorship: mentor, coach, sponsor, and connector. along the way.

For me, DDW serves as an annual reminder of the power of mentorship in building and sustaining careers. Each May, trainees and early career faculty present their projects in oral or poster sessions, cheered on by their research mentors. Senior thought leaders offer career advice and guidance to more junior colleagues through structured sessions or informal conversations and facilitate introductions to new collaborators. Department chairs, division chiefs, and senior practice leaders take time to reconnect with their early mentors who believed in their potential and provided them with opportunities to take their careers to new heights. And, we see the incredible payoff of programs like AGA’s FORWARD and Future Leaders Programs in serving as springboards for career advancement and creating powerful role models and mentors for the future.

This year’s AGA presidential leadership transition served as a particularly poignant example of the power of mentorship as incoming AGA President Dr. Barbara Jung succeeded one of her early mentors, outgoing AGA President Dr. John Carethers, in this prestigious role. I hope you’ll join me in reflecting on the tremendous impact that mentors, coaches, sponsors, and connectors have had on your career, and continue to pay it forward to the next generation.

In this month’s issue, we feature several stories from DDW 2023, including summaries of the AGA presidential address and a study evaluating the impact of state Medicaid expansion on uptake of CRC screening in safety-net practices. From AGA’s flagship journals, we highlight a propensity-matched cohort study assessing the impact of pancreatic cancer surveillance of high-risk patients on important clinical outcomes and a new AGA CPU on management of extraesophageal GERD. In this month’s AGA Policy and Advocacy column, Dr. Amit Patel and Dr. Rotonya Carr review the results of a recent membership survey on policy priorities and outline the many ways you can get involved in advocacy efforts. Finally, our Member Spotlight column celebrates gastroenterologist and humanitarian Kadirawel Iswara, MD, recipient of this year’s AGA Distinguished Clinician Award in Private Practice, who is a cherished mentor to many prominent members of our field.

Megan A. Adams, M.D., J.D., MSc

Editor-in-Chief

COVID boosters effective, but not for long

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

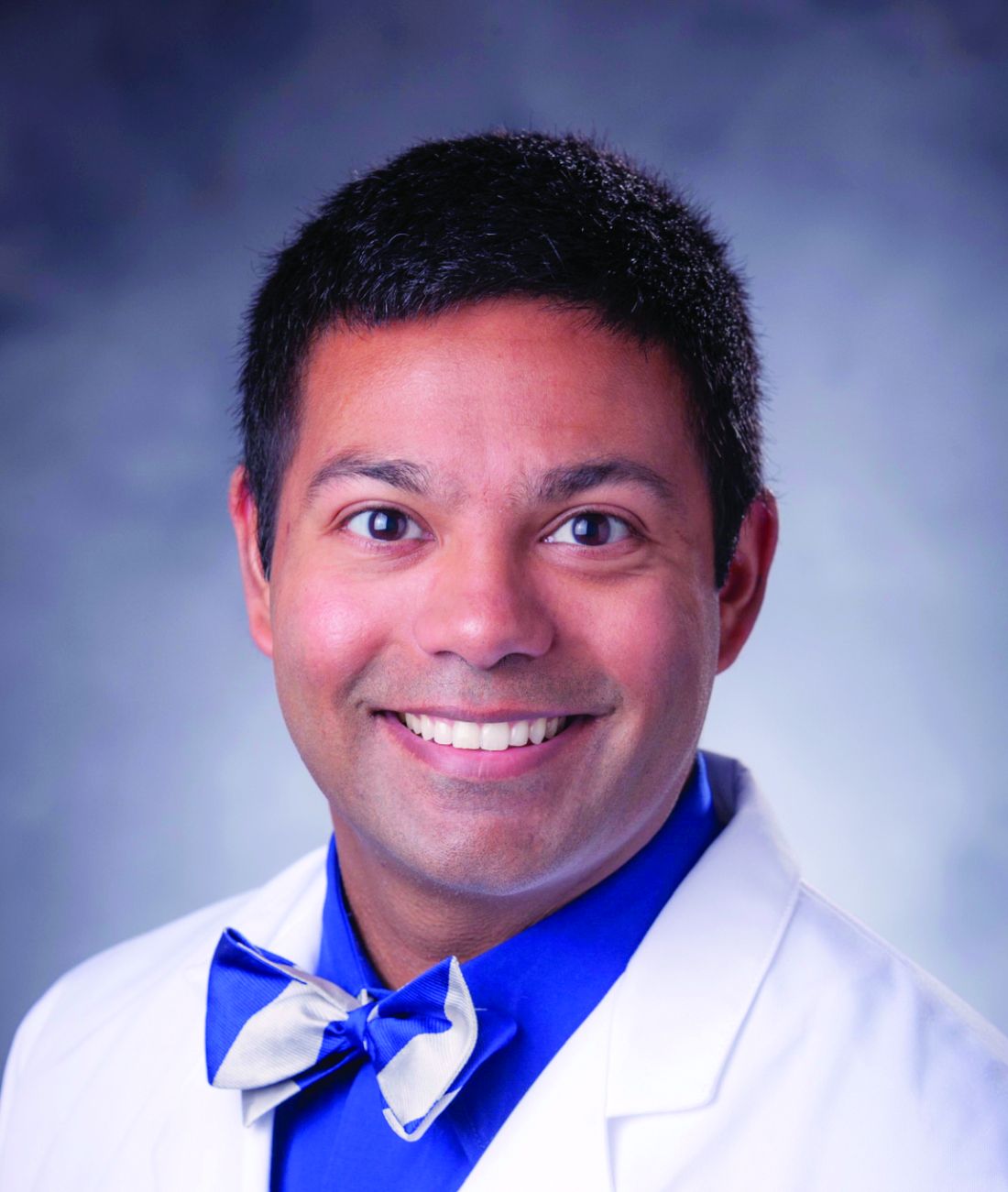

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

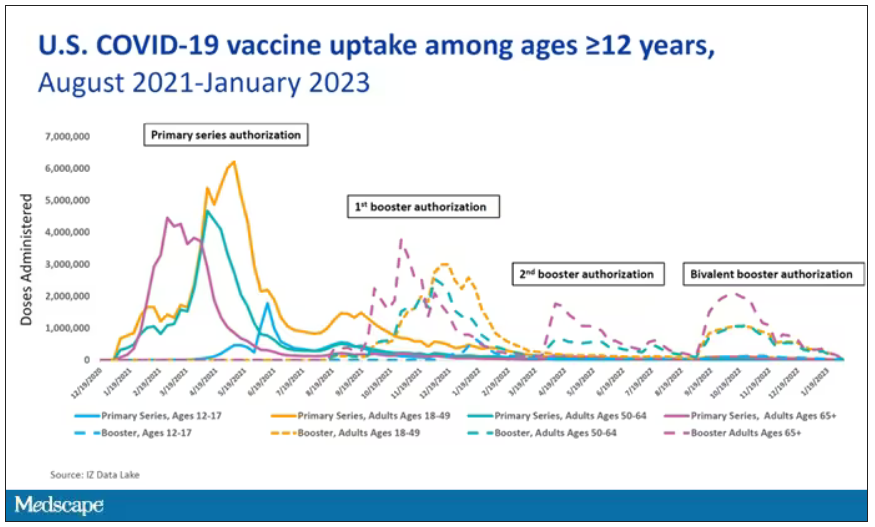

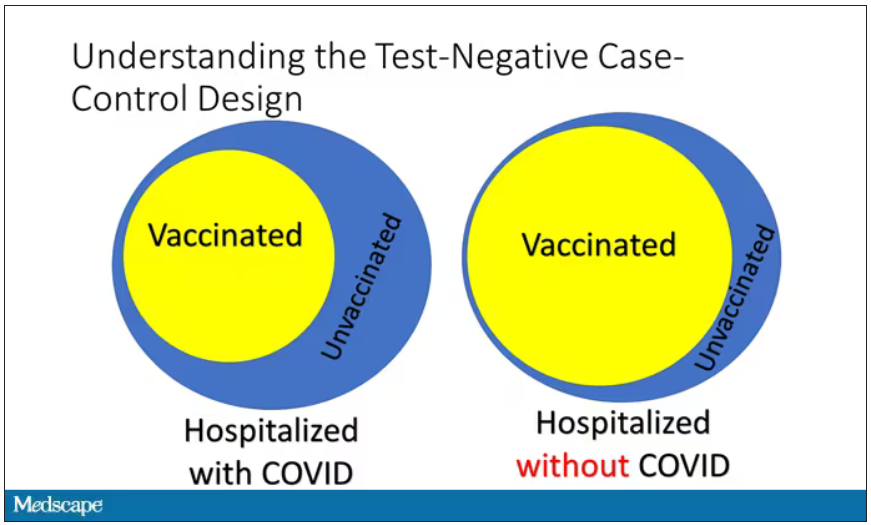

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

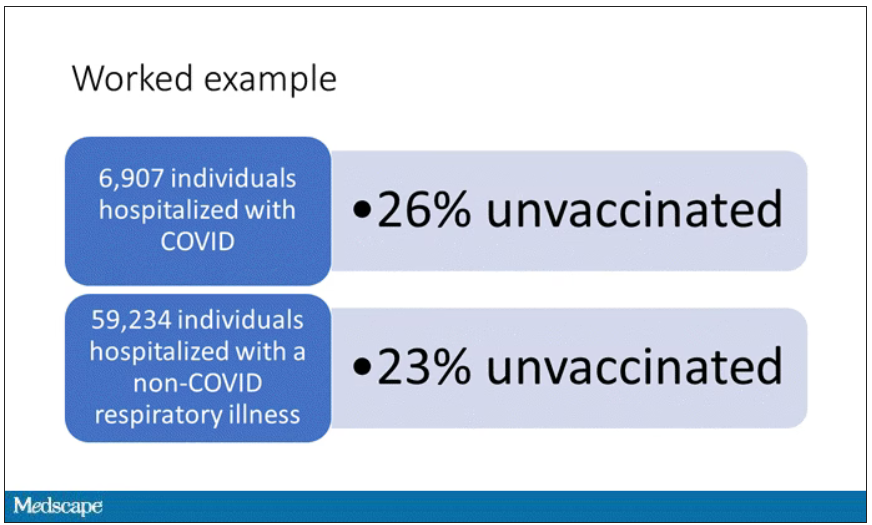

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

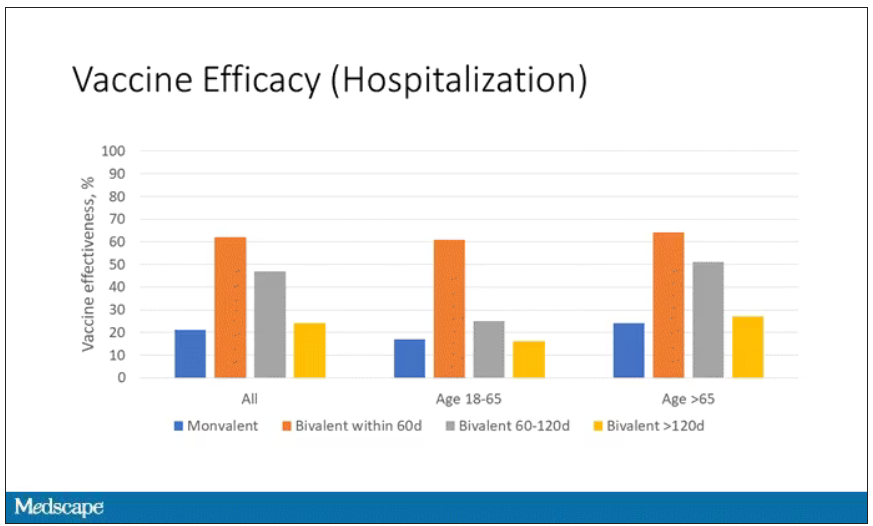

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

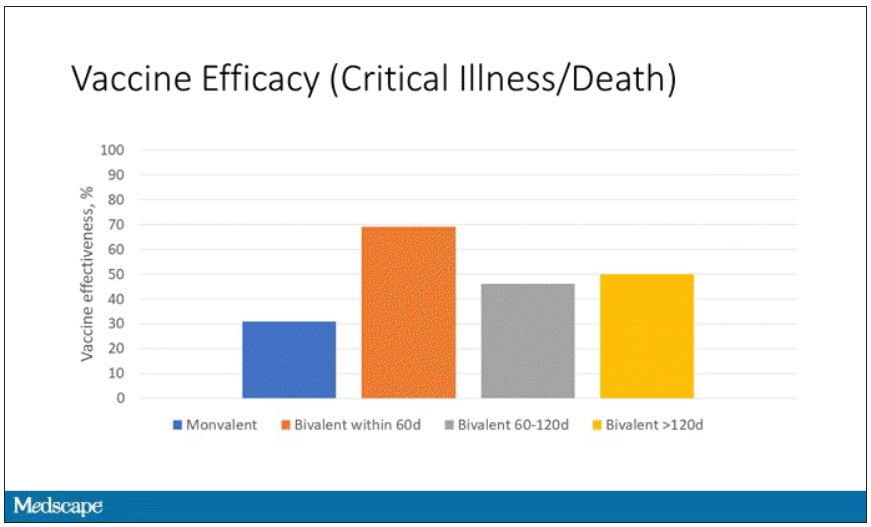

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

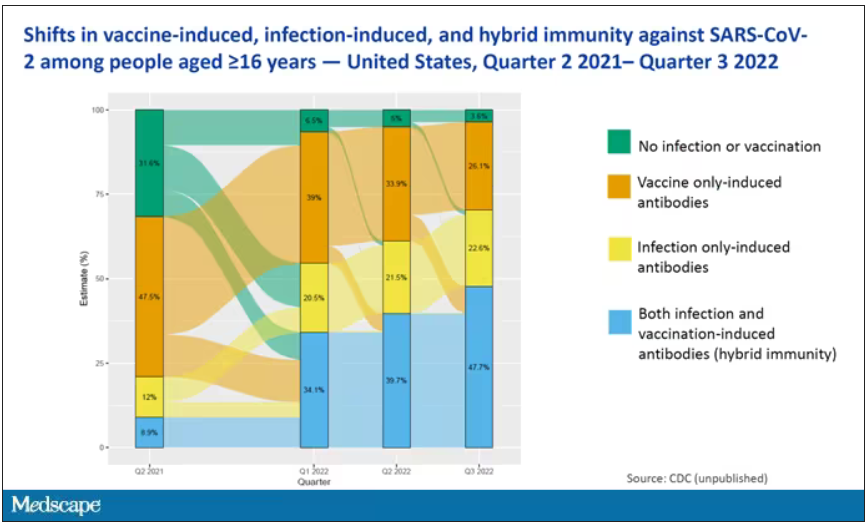

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.

The really interesting question about future vaccination and future booster doses is, how does it work on the background of this pattern? The CDC study doesn’t tell us, and I don’t think they have the data to tell us the vaccine efficacy in these different groups. Is it more effective in people who have only had an infection, for example? Is it more effective in people who have only had vaccination versus people who had both, or people who have no protection whatsoever? Those are the really interesting questions that need to be answered going forward as vaccine policy gets developed in the future.

I hope this was a helpful primer on how the test-negative case-control design can answer questions that seem a little bit unanswerable.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study.

I am here today to talk about the effectiveness of COVID vaccine boosters in the midst of 2023. The reason I want to talk about this isn’t necessarily to dig into exactly how effective vaccines are. This is an area that’s been trod upon multiple times. But it does give me an opportunity to talk about a neat study design called the “test-negative case-control” design, which has some unique properties when you’re trying to evaluate the effect of something outside of the context of a randomized trial.

So, just a little bit of background to remind everyone where we are. These are the number of doses of COVID vaccines administered over time throughout the pandemic.

You can see that it’s stratified by age. The orange lines are adults ages 18-49, for example. You can see a big wave of vaccination when the vaccine first came out at the start of 2021. Then subsequently, you can see smaller waves after the first and second booster authorizations, and maybe a bit of a pickup, particularly among older adults, when the bivalent boosters were authorized. But still very little overall pickup of the bivalent booster, compared with the monovalent vaccines, which might suggest vaccine fatigue going on this far into the pandemic. But it’s important to try to understand exactly how effective those new boosters are, at least at this point in time.

I’m talking about Early Estimates of Bivalent mRNA Booster Dose Vaccine Effectiveness in Preventing Symptomatic SARS-CoV-2 Infection Attributable to Omicron BA.5– and XBB/XBB.1.5–Related Sublineages Among Immunocompetent Adults – Increasing Community Access to Testing Program, United States, December 2022–January 2023, which came out in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report very recently, which uses this test-negative case-control design to evaluate the ability of bivalent mRNA vaccines to prevent hospitalization.

The question is: Does receipt of a bivalent COVID vaccine booster prevent hospitalizations, ICU stay, or death? That may not be the question that is of interest to everyone. I know people are interested in symptoms, missed work, and transmission, but this paper was looking at hospitalization, ICU stay, and death.

What’s kind of tricky here is that the data they’re using are in people who are hospitalized with various diseases. You might look at that on the surface and say: “Well, you can’t – that’s impossible.” But you can, actually, with this cool test-negative case-control design.

Here’s basically how it works. You take a population of people who are hospitalized and confirmed to have COVID. Some of them will be vaccinated and some of them will be unvaccinated. And the proportion of vaccinated and unvaccinated people doesn’t tell you very much because it depends on how that compares with the rates in the general population, for instance. Let me clarify this. If 100% of the population were vaccinated, then 100% of the people hospitalized with COVID would be vaccinated. That doesn’t mean vaccines are bad. Put another way, if 90% of the population were vaccinated and 60% of people hospitalized with COVID were vaccinated, that would actually show that the vaccines were working to some extent, all else being equal. So it’s not just the raw percentages that tell you anything. Some people are vaccinated, some people aren’t. You need to understand what the baseline rate is.

The test-negative case-control design looks at people who are hospitalized without COVID. Now who those people are (who the controls are, in this case) is something you really need to think about. In the case of this CDC study, they used people who were hospitalized with COVID-like illnesses – flu-like illnesses, respiratory illnesses, pneumonia, influenza, etc. This is a pretty good idea because it standardizes a little bit for people who have access to healthcare. They can get to a hospital and they’re the type of person who would go to a hospital when they’re feeling sick. That’s a better control than the general population overall, which is something I like about this design.

Some of those people who don’t have COVID (they’re in the hospital for flu or whatever) will have been vaccinated for COVID, and some will not have been vaccinated for COVID. And of course, we don’t expect COVID vaccines necessarily to protect against the flu or pneumonia, but that gives us a way to standardize.

If you look at these Venn diagrams, I’ve got vaccinated/unvaccinated being exactly the same proportion, which would suggest that you’re just as likely to be hospitalized with COVID if you’re vaccinated as you are to be hospitalized with some other respiratory illness, which suggests that the vaccine isn’t particularly effective.

However, if you saw something like this, looking at all those patients with flu and other non-COVID illnesses, a lot more of them had been vaccinated for COVID. What that tells you is that we’re seeing fewer vaccinated people hospitalized with COVID than we would expect because we have this standardization from other respiratory infections. We expect this many vaccinated people because that’s how many vaccinated people there are who show up with flu. But in the COVID population, there are fewer, and that would suggest that the vaccines are effective. So that is the test-negative case-control design. You can do the same thing with ICU stays and death.

There are some assumptions here which you might already be thinking about. The most important one is that vaccination status is not associated with the risk for the disease. I always think of older people in this context. During the pandemic, at least in the United States, older people were much more likely to be vaccinated but were also much more likely to contract COVID and be hospitalized with COVID. The test-negative design actually accounts for this in some sense, because older people are also more likely to be hospitalized for things like flu and pneumonia. So there’s some control there.

But to the extent that older people are uniquely susceptible to COVID compared with other respiratory illnesses, that would bias your results to make the vaccines look worse. So the standard approach here is to adjust for these things. I think the CDC adjusted for age, sex, race, ethnicity, and a few other things to settle down and see how effective the vaccines were.

Let’s get to a worked example.

This is the actual data from the CDC paper. They had 6,907 individuals who were hospitalized with COVID, and 26% of them were unvaccinated. What’s the baseline rate that we would expect to be unvaccinated? A total of 59,234 individuals were hospitalized with a non-COVID respiratory illness, and 23% of them were unvaccinated. So you can see that there were more unvaccinated people than you would think in the COVID group. In other words, fewer vaccinated people, which suggests that the vaccine works to some degree because it’s keeping some people out of the hospital.

Now, 26% versus 23% is not a very impressive difference. But it gets more interesting when you break it down by the type of vaccine and how long ago the individual was vaccinated.

Let’s walk through the “all” group on this figure. What you can see is the calculated vaccine effectiveness. If you look at just the monovalent vaccine here, we see a 20% vaccine effectiveness. This means that you’re preventing 20% of hospitalizations basically due to COVID by people getting vaccinated. That’s okay but it’s certainly not anything to write home about. But we see much better vaccine effectiveness with the bivalent vaccine if it had been received within 60 days.

This compares people who received the bivalent vaccine within 60 days in the COVID group and the non-COVID group. The concern that the vaccine was given very recently affects both groups equally so it shouldn’t result in bias there. You see a step-off in vaccine effectiveness from 60 days, 60-120 days, and greater than 120 days. This is 4 months, and you’ve gone from 60% to 20%. When you break that down by age, you can see a similar pattern in the 18-to-65 group and potentially some more protection the greater than 65 age group.

Why is vaccine efficacy going down? The study doesn’t tell us, but we can hypothesize that this might be an immunologic effect – the antibodies or the protective T cells are waning over time. This could also reflect changes in the virus in the environment as the virus seeks to evade certain immune responses. But overall, this suggests that waiting a year between booster doses may leave you exposed for quite some time, although the take-home here is that bivalent vaccines in general are probably a good idea for the proportion of people who haven’t gotten them.

When we look at critical illness and death, the numbers look a little bit better.

You can see that bivalent is better than monovalent – certainly pretty good if you’ve received it within 60 days. It does tend to wane a little bit, but not nearly as much. You’ve still got about 50% vaccine efficacy beyond 120 days when we’re looking at critical illness, which is stays in the ICU and death.

The overriding thing to think about when we think about vaccine policy is that the way you get immunized against COVID is either by vaccine or by getting infected with COVID, or both.

This really interesting graph from the CDC (although it’s updated only through quarter three of 2022) shows the proportion of Americans, based on routine lab tests, who have varying degrees of protection against COVID. What you can see is that, by quarter three of 2022, just 3.6% of people who had blood drawn at a commercial laboratory had no evidence of infection or vaccination. In other words, almost no one was totally naive. Then 26% of people had never been infected – they only have vaccine antibodies – plus 22% of people had only been infected but had never been vaccinated. And then 50% of people had both. So there’s a tremendous amount of existing immunity out there.