User login

What to expect in the new concussion guidelines

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD: I’m your host, Dr. Andrew Wilner, reporting virtually from the 2023 American Academy of Neurology meeting in Boston. It’s my pleasure today to speak with Dr. Shae Datta, codirector of the NYU Langone Concussion Center.

She’s also a clinical assistant professor of neurology at NYU School of Medicine. Dr. Datta is chair of the AAN Sports Neurology Section, and she’s leading a panel on concussion at this year’s meeting. She’s going to give us an update. Welcome, Dr. Datta.

Shae Datta, MD: Thank you so much, Andrew. I really love the fact that I’m here speaking to you about all of the new, exciting developments in the field.

Dr. Wilner: Before we get too deep, tell us how you got interested in this topic.

Dr. Datta: I initially thought, when I was in training as a resident, that I wanted to do something like neurocritical care or EEG. It also puzzled me why these seemingly smaller head injuries that didn’t end up in the hospital or ICU were bounced from neurology headache clinic to neuro-ophthalmology headache clinic to neurovestibular headache clinic, and nobody seemed to be able to put together the dots about why they’re having so many different issues — but at the same time, nobody could help them.

At that time, this field was very new. I was on a plane to Paris to a neurocritical care conference as a resident, and I saw the movie Concussion with Will Smith.

It featured one of my current mentors who taught at the fellowship that I graduated from, and it was a fascinating field. I just started looking deeply into it, and I saw that there was a new training fellowship for sports neurology and concussion management, and this is basically why we’re here today.

New concussion consensus guidelines coming

Dr. Wilner: I think this field has really exploded. It used to be that you banged your head, you did a CT scan – remember, I trained about 45 years ago – and if there was nothing on the CT scan, you were done. If you had headaches, you took Tylenol until they went away.

Now, we do MRI, and we realized that it’s really a syndrome. I understand that there are going to be some formal guidelines that have been put together. Is that correct?

Dr. Datta: That’s correct. The 6th International Consensus Conference on Concussion in Sport, in Amsterdam, where I attended and presented a poster, was really a meeting of all the best minds – clinicians and researchers in brain injury – to form a consensus on the newest guidelines that are going to direct our treatment going forward.

Dr. Wilner: I’m going to ask you a trick question because the last time I looked it up I did not get a satisfying answer. What is a concussion?

Dr. Datta: That’s a very good question, and everyone always asks. A concussion is an external force that is emitted upon the head or the neck, or the body, in general, that may cause temporary loss of function. It’s a functional problem.

We don’t see much on CT. We can do MRI. We can do SPECT or we can do these very fancy images, sometimes, of high-velocity head injuries and see small microhemorrhages.

Often, we don’t see anything, but still the patient is loopy. They can’t see straight. They are double-visioned. They have vertigo. Why is that happening? On the cellular level, we have an energy deficit in the sodium-potassium-ATPase pump of the neurons themselves.

Dr. Wilner: Suppose you do see diffuse axonal injury; does that take it out of concussion, or can you have a concussion with visible injury?

Dr. Datta: I think you can have overlap in the symptoms. The diffuse axonal injury would put it into a higher grade of head injury as opposed to a mild traumatic brain injury. Definitely, we would need to work together with our trauma doctors to ensure that patients are not on blood thinners or anything until they heal well enough. Obviously, I would pick them up as an outpatient and follow them until we resolve or rehab them as best as possible.

Concussion assessment tools

Dr. Wilner: There are many sports out there where concussions are fairly frequent, like American football and hockey, for example. Are there any statements in the new guidelines?

Dr. Datta: There are no statements for or against a particular sport because that would really make too much of a bold statement about cause and effect. There is a cause and effect in long-term, repetitive exposure, I would say, in terms of someone being able to play or sustain injury.

Right now, at least at the concussion conference I went to and in the upcoming consensus statement, they will not comment on a specific sport. Obviously, we know that the higher-impact sports are a little more dangerous.

Let’s be honest. At the high school, middle school, or even younger level, some kids are not necessarily the most athletic, right? They play because their friends are playing. If they’re repeatedly getting injured, it’s time for an astute clinician, or a coach, and a whole team to assess them to see if maybe this person is just going to continue to get hurt if they’re not taken out of the game and perhaps they should go to a lower-impact sport.

Dr. Wilner: In schools, often there’s a big size and weight difference. There are 14-year-olds who are 6 fett 2 inches and 200 pounds, and there are 14-year-olds who are 5 feet 2 inches and 110 pounds. Obviously, they’re mismatched on the football field.

You mentioned coaches. Is there anything in the guidelines about training coaches?

Dr. Datta: Specifically, there was nothing in the guidelines about that. There’s a tool for coaches at every level to use, which is called the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool, or SCAT, which is going to be updated to the SCAT6. At the NCAA level, they must receive annual training on concussion management and be given an NCAA concussion handout for coaches.

Obviously, there are more rigorous protocols for national-level coaching. As it stands now, it is not mandatory, but they are given tools to assess someone once they’ve gotten a hit to take them out of the game.

Dr. Wilner: I’ve been following the concussion research through the years. They did some neuropsychological testing on athletes who’ve had this many concussions or that many concussions, and they would find deficits here or subtle deficits there, but they had no baseline.

Then, there was a movement to start testing athletes before the season starts so that they could do a repeat test after concussion and see if there is any difference. Is that something we’re recommending?

Dr. Datta: Most of the time, NCAA-level – certainly where I trained – and national-level sports do testing, but it’s not everywhere. Prior guidelines have indicated that preseason testing is not required. That is largely because there has been no standardized neuropsychological testing established.

There are computerized testing options where the validity and reliability are questionable. Also, let’s say it’s a college student; they didn’t sleep all night and then they took this computer test. They would probably do worse than they would if they had received a head hit.

Just to be on the safe side, most places that have collegiate-level sports that are at a high level do preseason testing. If I were to speak personally, aside from the guidelines, I would say that it’s been helpful for me to look at the before and after, in general, overall, to make a decision about my treatment protocol.

Dr. Wilner: Let’s talk about the patient. You have a 20-year-old guy. He’s playing football. There’s a big play. Bonk, he gets hit on the head. He’s on the ground. He’s dazed, staggers a little bit, gets up, and you ask how he is feeling. He says he’s fine and then he wobbles off to the sideline. What do you do with that kid?

Dr. Datta: Obviously, the first thing is to remove him from the play environment to a quiet space. Second, either an athletic trainer or a coach would administer basic screening neurologic tests, such as “where are you, what’s today’s date, what is your name?” and other orientation questions.

They’ll also go through the SCAT – that’ll be SCAT6 starting in July – the SCAT5 symptom questionnaire to see what symptoms they have. Often, they’re using sideline testing software.

There are two things that can be used on a card to test eye movements, to see if they’re slower. They come out of NYU, coincidentally – the Memory Image Completion (MIC) and the Mobile Universal Lexicon Evaluation System (MULES) – and are used to determine whether eye movements are slower. That way, you can tell whether someone is, compared with before they got their head hit, slower than before.

Based on this composite information, usually the teammates and the head people on the team will know if a player looks different.

They need to be taken out, obviously, if there is nausea or vomiting, any neurologic signs and symptoms, or a neck injury that needs to be stabilized. ABCs first, right? If there’s any vomiting or seizures, they should be taken to the ER right away.

The first thing is to take them out, then do a sideline assessment. Third, see if they need to immediately go to the ED versus follow-up outpatient with me within a day or two.

Dr. Wilner: I think it’s the subtle injuries that are the tough ones. Back to our 20-year-old. He says: “Oh, I’m fine. I want to go back in the game.” Everybody can tell he’s not quite right, even though he passed all the tests. What do you do then?

Dr. Datta: You have to make a judgment call for the safety of the player. They always want to go back, right? This is also an issue when they’re competing for college scholarships and things of that nature. Sometimes they’re sandbagging, where they memorize the answers.

Everything’s on the Internet nowadays, right? We have to make a judgment call as members of the healthcare community and the sports community to keep that player safe.

Just keep them out. Don’t bring them back in the game. Keep them out for a reasonable amount of time. There’s a test called the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test; Dr. John Leddy from University of Buffalo has developed a way for us to put athletes through a screening protocol.

This can be part of their vestibular and ocular rehabilitation, where if they don’t have symptoms when we bring their heart rate to certain levels, then we can slowly clear them for return to play as long as they’re nonsymptomatic.

Dr. Wilner: I spoke with your colleague, Dr. Riggins, who is also on your panel, and we were talking about when they can go back. She said they can go back when they don’t have any symptoms. No more headache, no more dizziness, no more lightheadedness, no more trouble concentrating or with memory – all those things have gone away.

Sometimes these symptoms are stubborn. If you have, say, 100 patients like our 20-year-old who got bonked on the head, has some headaches, and doesn’t feel quite right, what usually happens? How many are back to play the next day, the next week, or the next month? How many are out for the season? How does that play out?

Dr. Datta: It depends on a couple of different factors. One, have they had previous head injuries? Two, do they have preexisting symptoms or signs, or diagnoses like migraines, which are likely to get worse after a head injury? Anything that’s preexisting, like a mood disorder, anxiety, depression, or trouble sleeping, is going to get worse.

If they were compensating for untreated ADD or borderline personality or bipolar, I’ve seen many people who’ve developed them. These are not the norm, but I’m saying that you have to be very careful.

Getting back to the question, you treat them. Reasonably, if they’re healthy and they don’t have preexisting signs and symptoms, I would say more than half are back in about 2 weeks.. I would say 60%-70%. It all depends. If they have preexisting issues, then it’s going to take much longer.

From SCAT to SCOAT

Dr. Wilner: This has been very informative. Before we wrap up, tell us what to expect from these guidelines in July. How are they really going to help?

Dr. Datta: We’ve been using the SCAT, which was meant for more sideline assessment because that’s all we had, and it’s worked perfectly well.

This will be better because we often see them within 24-48 hours, when the symptoms are sometimes a little bit better.

We also will see the sport and concussion group come up with added athlete perspectives, ethics discussion, power-sport athlete considerations, and development of this new SCOAT.

Dr. Wilner: Dr. Datta, this is very exciting. I look forward to reading these guidelines in July. I want to thank you for your hard work. I also look forward to talking to you at next year’s meeting. Thank you very much for giving us this update.

Dr. Datta: No problem. It’s my pleasure.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD: I’m your host, Dr. Andrew Wilner, reporting virtually from the 2023 American Academy of Neurology meeting in Boston. It’s my pleasure today to speak with Dr. Shae Datta, codirector of the NYU Langone Concussion Center.

She’s also a clinical assistant professor of neurology at NYU School of Medicine. Dr. Datta is chair of the AAN Sports Neurology Section, and she’s leading a panel on concussion at this year’s meeting. She’s going to give us an update. Welcome, Dr. Datta.

Shae Datta, MD: Thank you so much, Andrew. I really love the fact that I’m here speaking to you about all of the new, exciting developments in the field.

Dr. Wilner: Before we get too deep, tell us how you got interested in this topic.

Dr. Datta: I initially thought, when I was in training as a resident, that I wanted to do something like neurocritical care or EEG. It also puzzled me why these seemingly smaller head injuries that didn’t end up in the hospital or ICU were bounced from neurology headache clinic to neuro-ophthalmology headache clinic to neurovestibular headache clinic, and nobody seemed to be able to put together the dots about why they’re having so many different issues — but at the same time, nobody could help them.

At that time, this field was very new. I was on a plane to Paris to a neurocritical care conference as a resident, and I saw the movie Concussion with Will Smith.

It featured one of my current mentors who taught at the fellowship that I graduated from, and it was a fascinating field. I just started looking deeply into it, and I saw that there was a new training fellowship for sports neurology and concussion management, and this is basically why we’re here today.

New concussion consensus guidelines coming

Dr. Wilner: I think this field has really exploded. It used to be that you banged your head, you did a CT scan – remember, I trained about 45 years ago – and if there was nothing on the CT scan, you were done. If you had headaches, you took Tylenol until they went away.

Now, we do MRI, and we realized that it’s really a syndrome. I understand that there are going to be some formal guidelines that have been put together. Is that correct?

Dr. Datta: That’s correct. The 6th International Consensus Conference on Concussion in Sport, in Amsterdam, where I attended and presented a poster, was really a meeting of all the best minds – clinicians and researchers in brain injury – to form a consensus on the newest guidelines that are going to direct our treatment going forward.

Dr. Wilner: I’m going to ask you a trick question because the last time I looked it up I did not get a satisfying answer. What is a concussion?

Dr. Datta: That’s a very good question, and everyone always asks. A concussion is an external force that is emitted upon the head or the neck, or the body, in general, that may cause temporary loss of function. It’s a functional problem.

We don’t see much on CT. We can do MRI. We can do SPECT or we can do these very fancy images, sometimes, of high-velocity head injuries and see small microhemorrhages.

Often, we don’t see anything, but still the patient is loopy. They can’t see straight. They are double-visioned. They have vertigo. Why is that happening? On the cellular level, we have an energy deficit in the sodium-potassium-ATPase pump of the neurons themselves.

Dr. Wilner: Suppose you do see diffuse axonal injury; does that take it out of concussion, or can you have a concussion with visible injury?

Dr. Datta: I think you can have overlap in the symptoms. The diffuse axonal injury would put it into a higher grade of head injury as opposed to a mild traumatic brain injury. Definitely, we would need to work together with our trauma doctors to ensure that patients are not on blood thinners or anything until they heal well enough. Obviously, I would pick them up as an outpatient and follow them until we resolve or rehab them as best as possible.

Concussion assessment tools

Dr. Wilner: There are many sports out there where concussions are fairly frequent, like American football and hockey, for example. Are there any statements in the new guidelines?

Dr. Datta: There are no statements for or against a particular sport because that would really make too much of a bold statement about cause and effect. There is a cause and effect in long-term, repetitive exposure, I would say, in terms of someone being able to play or sustain injury.

Right now, at least at the concussion conference I went to and in the upcoming consensus statement, they will not comment on a specific sport. Obviously, we know that the higher-impact sports are a little more dangerous.

Let’s be honest. At the high school, middle school, or even younger level, some kids are not necessarily the most athletic, right? They play because their friends are playing. If they’re repeatedly getting injured, it’s time for an astute clinician, or a coach, and a whole team to assess them to see if maybe this person is just going to continue to get hurt if they’re not taken out of the game and perhaps they should go to a lower-impact sport.

Dr. Wilner: In schools, often there’s a big size and weight difference. There are 14-year-olds who are 6 fett 2 inches and 200 pounds, and there are 14-year-olds who are 5 feet 2 inches and 110 pounds. Obviously, they’re mismatched on the football field.

You mentioned coaches. Is there anything in the guidelines about training coaches?

Dr. Datta: Specifically, there was nothing in the guidelines about that. There’s a tool for coaches at every level to use, which is called the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool, or SCAT, which is going to be updated to the SCAT6. At the NCAA level, they must receive annual training on concussion management and be given an NCAA concussion handout for coaches.

Obviously, there are more rigorous protocols for national-level coaching. As it stands now, it is not mandatory, but they are given tools to assess someone once they’ve gotten a hit to take them out of the game.

Dr. Wilner: I’ve been following the concussion research through the years. They did some neuropsychological testing on athletes who’ve had this many concussions or that many concussions, and they would find deficits here or subtle deficits there, but they had no baseline.

Then, there was a movement to start testing athletes before the season starts so that they could do a repeat test after concussion and see if there is any difference. Is that something we’re recommending?

Dr. Datta: Most of the time, NCAA-level – certainly where I trained – and national-level sports do testing, but it’s not everywhere. Prior guidelines have indicated that preseason testing is not required. That is largely because there has been no standardized neuropsychological testing established.

There are computerized testing options where the validity and reliability are questionable. Also, let’s say it’s a college student; they didn’t sleep all night and then they took this computer test. They would probably do worse than they would if they had received a head hit.

Just to be on the safe side, most places that have collegiate-level sports that are at a high level do preseason testing. If I were to speak personally, aside from the guidelines, I would say that it’s been helpful for me to look at the before and after, in general, overall, to make a decision about my treatment protocol.

Dr. Wilner: Let’s talk about the patient. You have a 20-year-old guy. He’s playing football. There’s a big play. Bonk, he gets hit on the head. He’s on the ground. He’s dazed, staggers a little bit, gets up, and you ask how he is feeling. He says he’s fine and then he wobbles off to the sideline. What do you do with that kid?

Dr. Datta: Obviously, the first thing is to remove him from the play environment to a quiet space. Second, either an athletic trainer or a coach would administer basic screening neurologic tests, such as “where are you, what’s today’s date, what is your name?” and other orientation questions.

They’ll also go through the SCAT – that’ll be SCAT6 starting in July – the SCAT5 symptom questionnaire to see what symptoms they have. Often, they’re using sideline testing software.

There are two things that can be used on a card to test eye movements, to see if they’re slower. They come out of NYU, coincidentally – the Memory Image Completion (MIC) and the Mobile Universal Lexicon Evaluation System (MULES) – and are used to determine whether eye movements are slower. That way, you can tell whether someone is, compared with before they got their head hit, slower than before.

Based on this composite information, usually the teammates and the head people on the team will know if a player looks different.

They need to be taken out, obviously, if there is nausea or vomiting, any neurologic signs and symptoms, or a neck injury that needs to be stabilized. ABCs first, right? If there’s any vomiting or seizures, they should be taken to the ER right away.

The first thing is to take them out, then do a sideline assessment. Third, see if they need to immediately go to the ED versus follow-up outpatient with me within a day or two.

Dr. Wilner: I think it’s the subtle injuries that are the tough ones. Back to our 20-year-old. He says: “Oh, I’m fine. I want to go back in the game.” Everybody can tell he’s not quite right, even though he passed all the tests. What do you do then?

Dr. Datta: You have to make a judgment call for the safety of the player. They always want to go back, right? This is also an issue when they’re competing for college scholarships and things of that nature. Sometimes they’re sandbagging, where they memorize the answers.

Everything’s on the Internet nowadays, right? We have to make a judgment call as members of the healthcare community and the sports community to keep that player safe.

Just keep them out. Don’t bring them back in the game. Keep them out for a reasonable amount of time. There’s a test called the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test; Dr. John Leddy from University of Buffalo has developed a way for us to put athletes through a screening protocol.

This can be part of their vestibular and ocular rehabilitation, where if they don’t have symptoms when we bring their heart rate to certain levels, then we can slowly clear them for return to play as long as they’re nonsymptomatic.

Dr. Wilner: I spoke with your colleague, Dr. Riggins, who is also on your panel, and we were talking about when they can go back. She said they can go back when they don’t have any symptoms. No more headache, no more dizziness, no more lightheadedness, no more trouble concentrating or with memory – all those things have gone away.

Sometimes these symptoms are stubborn. If you have, say, 100 patients like our 20-year-old who got bonked on the head, has some headaches, and doesn’t feel quite right, what usually happens? How many are back to play the next day, the next week, or the next month? How many are out for the season? How does that play out?

Dr. Datta: It depends on a couple of different factors. One, have they had previous head injuries? Two, do they have preexisting symptoms or signs, or diagnoses like migraines, which are likely to get worse after a head injury? Anything that’s preexisting, like a mood disorder, anxiety, depression, or trouble sleeping, is going to get worse.

If they were compensating for untreated ADD or borderline personality or bipolar, I’ve seen many people who’ve developed them. These are not the norm, but I’m saying that you have to be very careful.

Getting back to the question, you treat them. Reasonably, if they’re healthy and they don’t have preexisting signs and symptoms, I would say more than half are back in about 2 weeks.. I would say 60%-70%. It all depends. If they have preexisting issues, then it’s going to take much longer.

From SCAT to SCOAT

Dr. Wilner: This has been very informative. Before we wrap up, tell us what to expect from these guidelines in July. How are they really going to help?

Dr. Datta: We’ve been using the SCAT, which was meant for more sideline assessment because that’s all we had, and it’s worked perfectly well.

This will be better because we often see them within 24-48 hours, when the symptoms are sometimes a little bit better.

We also will see the sport and concussion group come up with added athlete perspectives, ethics discussion, power-sport athlete considerations, and development of this new SCOAT.

Dr. Wilner: Dr. Datta, this is very exciting. I look forward to reading these guidelines in July. I want to thank you for your hard work. I also look forward to talking to you at next year’s meeting. Thank you very much for giving us this update.

Dr. Datta: No problem. It’s my pleasure.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Andrew N. Wilner, MD: I’m your host, Dr. Andrew Wilner, reporting virtually from the 2023 American Academy of Neurology meeting in Boston. It’s my pleasure today to speak with Dr. Shae Datta, codirector of the NYU Langone Concussion Center.

She’s also a clinical assistant professor of neurology at NYU School of Medicine. Dr. Datta is chair of the AAN Sports Neurology Section, and she’s leading a panel on concussion at this year’s meeting. She’s going to give us an update. Welcome, Dr. Datta.

Shae Datta, MD: Thank you so much, Andrew. I really love the fact that I’m here speaking to you about all of the new, exciting developments in the field.

Dr. Wilner: Before we get too deep, tell us how you got interested in this topic.

Dr. Datta: I initially thought, when I was in training as a resident, that I wanted to do something like neurocritical care or EEG. It also puzzled me why these seemingly smaller head injuries that didn’t end up in the hospital or ICU were bounced from neurology headache clinic to neuro-ophthalmology headache clinic to neurovestibular headache clinic, and nobody seemed to be able to put together the dots about why they’re having so many different issues — but at the same time, nobody could help them.

At that time, this field was very new. I was on a plane to Paris to a neurocritical care conference as a resident, and I saw the movie Concussion with Will Smith.

It featured one of my current mentors who taught at the fellowship that I graduated from, and it was a fascinating field. I just started looking deeply into it, and I saw that there was a new training fellowship for sports neurology and concussion management, and this is basically why we’re here today.

New concussion consensus guidelines coming

Dr. Wilner: I think this field has really exploded. It used to be that you banged your head, you did a CT scan – remember, I trained about 45 years ago – and if there was nothing on the CT scan, you were done. If you had headaches, you took Tylenol until they went away.

Now, we do MRI, and we realized that it’s really a syndrome. I understand that there are going to be some formal guidelines that have been put together. Is that correct?

Dr. Datta: That’s correct. The 6th International Consensus Conference on Concussion in Sport, in Amsterdam, where I attended and presented a poster, was really a meeting of all the best minds – clinicians and researchers in brain injury – to form a consensus on the newest guidelines that are going to direct our treatment going forward.

Dr. Wilner: I’m going to ask you a trick question because the last time I looked it up I did not get a satisfying answer. What is a concussion?

Dr. Datta: That’s a very good question, and everyone always asks. A concussion is an external force that is emitted upon the head or the neck, or the body, in general, that may cause temporary loss of function. It’s a functional problem.

We don’t see much on CT. We can do MRI. We can do SPECT or we can do these very fancy images, sometimes, of high-velocity head injuries and see small microhemorrhages.

Often, we don’t see anything, but still the patient is loopy. They can’t see straight. They are double-visioned. They have vertigo. Why is that happening? On the cellular level, we have an energy deficit in the sodium-potassium-ATPase pump of the neurons themselves.

Dr. Wilner: Suppose you do see diffuse axonal injury; does that take it out of concussion, or can you have a concussion with visible injury?

Dr. Datta: I think you can have overlap in the symptoms. The diffuse axonal injury would put it into a higher grade of head injury as opposed to a mild traumatic brain injury. Definitely, we would need to work together with our trauma doctors to ensure that patients are not on blood thinners or anything until they heal well enough. Obviously, I would pick them up as an outpatient and follow them until we resolve or rehab them as best as possible.

Concussion assessment tools

Dr. Wilner: There are many sports out there where concussions are fairly frequent, like American football and hockey, for example. Are there any statements in the new guidelines?

Dr. Datta: There are no statements for or against a particular sport because that would really make too much of a bold statement about cause and effect. There is a cause and effect in long-term, repetitive exposure, I would say, in terms of someone being able to play or sustain injury.

Right now, at least at the concussion conference I went to and in the upcoming consensus statement, they will not comment on a specific sport. Obviously, we know that the higher-impact sports are a little more dangerous.

Let’s be honest. At the high school, middle school, or even younger level, some kids are not necessarily the most athletic, right? They play because their friends are playing. If they’re repeatedly getting injured, it’s time for an astute clinician, or a coach, and a whole team to assess them to see if maybe this person is just going to continue to get hurt if they’re not taken out of the game and perhaps they should go to a lower-impact sport.

Dr. Wilner: In schools, often there’s a big size and weight difference. There are 14-year-olds who are 6 fett 2 inches and 200 pounds, and there are 14-year-olds who are 5 feet 2 inches and 110 pounds. Obviously, they’re mismatched on the football field.

You mentioned coaches. Is there anything in the guidelines about training coaches?

Dr. Datta: Specifically, there was nothing in the guidelines about that. There’s a tool for coaches at every level to use, which is called the Sports Concussion Assessment Tool, or SCAT, which is going to be updated to the SCAT6. At the NCAA level, they must receive annual training on concussion management and be given an NCAA concussion handout for coaches.

Obviously, there are more rigorous protocols for national-level coaching. As it stands now, it is not mandatory, but they are given tools to assess someone once they’ve gotten a hit to take them out of the game.

Dr. Wilner: I’ve been following the concussion research through the years. They did some neuropsychological testing on athletes who’ve had this many concussions or that many concussions, and they would find deficits here or subtle deficits there, but they had no baseline.

Then, there was a movement to start testing athletes before the season starts so that they could do a repeat test after concussion and see if there is any difference. Is that something we’re recommending?

Dr. Datta: Most of the time, NCAA-level – certainly where I trained – and national-level sports do testing, but it’s not everywhere. Prior guidelines have indicated that preseason testing is not required. That is largely because there has been no standardized neuropsychological testing established.

There are computerized testing options where the validity and reliability are questionable. Also, let’s say it’s a college student; they didn’t sleep all night and then they took this computer test. They would probably do worse than they would if they had received a head hit.

Just to be on the safe side, most places that have collegiate-level sports that are at a high level do preseason testing. If I were to speak personally, aside from the guidelines, I would say that it’s been helpful for me to look at the before and after, in general, overall, to make a decision about my treatment protocol.

Dr. Wilner: Let’s talk about the patient. You have a 20-year-old guy. He’s playing football. There’s a big play. Bonk, he gets hit on the head. He’s on the ground. He’s dazed, staggers a little bit, gets up, and you ask how he is feeling. He says he’s fine and then he wobbles off to the sideline. What do you do with that kid?

Dr. Datta: Obviously, the first thing is to remove him from the play environment to a quiet space. Second, either an athletic trainer or a coach would administer basic screening neurologic tests, such as “where are you, what’s today’s date, what is your name?” and other orientation questions.

They’ll also go through the SCAT – that’ll be SCAT6 starting in July – the SCAT5 symptom questionnaire to see what symptoms they have. Often, they’re using sideline testing software.

There are two things that can be used on a card to test eye movements, to see if they’re slower. They come out of NYU, coincidentally – the Memory Image Completion (MIC) and the Mobile Universal Lexicon Evaluation System (MULES) – and are used to determine whether eye movements are slower. That way, you can tell whether someone is, compared with before they got their head hit, slower than before.

Based on this composite information, usually the teammates and the head people on the team will know if a player looks different.

They need to be taken out, obviously, if there is nausea or vomiting, any neurologic signs and symptoms, or a neck injury that needs to be stabilized. ABCs first, right? If there’s any vomiting or seizures, they should be taken to the ER right away.

The first thing is to take them out, then do a sideline assessment. Third, see if they need to immediately go to the ED versus follow-up outpatient with me within a day or two.

Dr. Wilner: I think it’s the subtle injuries that are the tough ones. Back to our 20-year-old. He says: “Oh, I’m fine. I want to go back in the game.” Everybody can tell he’s not quite right, even though he passed all the tests. What do you do then?

Dr. Datta: You have to make a judgment call for the safety of the player. They always want to go back, right? This is also an issue when they’re competing for college scholarships and things of that nature. Sometimes they’re sandbagging, where they memorize the answers.

Everything’s on the Internet nowadays, right? We have to make a judgment call as members of the healthcare community and the sports community to keep that player safe.

Just keep them out. Don’t bring them back in the game. Keep them out for a reasonable amount of time. There’s a test called the Buffalo Concussion Treadmill Test; Dr. John Leddy from University of Buffalo has developed a way for us to put athletes through a screening protocol.

This can be part of their vestibular and ocular rehabilitation, where if they don’t have symptoms when we bring their heart rate to certain levels, then we can slowly clear them for return to play as long as they’re nonsymptomatic.

Dr. Wilner: I spoke with your colleague, Dr. Riggins, who is also on your panel, and we were talking about when they can go back. She said they can go back when they don’t have any symptoms. No more headache, no more dizziness, no more lightheadedness, no more trouble concentrating or with memory – all those things have gone away.

Sometimes these symptoms are stubborn. If you have, say, 100 patients like our 20-year-old who got bonked on the head, has some headaches, and doesn’t feel quite right, what usually happens? How many are back to play the next day, the next week, or the next month? How many are out for the season? How does that play out?

Dr. Datta: It depends on a couple of different factors. One, have they had previous head injuries? Two, do they have preexisting symptoms or signs, or diagnoses like migraines, which are likely to get worse after a head injury? Anything that’s preexisting, like a mood disorder, anxiety, depression, or trouble sleeping, is going to get worse.

If they were compensating for untreated ADD or borderline personality or bipolar, I’ve seen many people who’ve developed them. These are not the norm, but I’m saying that you have to be very careful.

Getting back to the question, you treat them. Reasonably, if they’re healthy and they don’t have preexisting signs and symptoms, I would say more than half are back in about 2 weeks.. I would say 60%-70%. It all depends. If they have preexisting issues, then it’s going to take much longer.

From SCAT to SCOAT

Dr. Wilner: This has been very informative. Before we wrap up, tell us what to expect from these guidelines in July. How are they really going to help?

Dr. Datta: We’ve been using the SCAT, which was meant for more sideline assessment because that’s all we had, and it’s worked perfectly well.

This will be better because we often see them within 24-48 hours, when the symptoms are sometimes a little bit better.

We also will see the sport and concussion group come up with added athlete perspectives, ethics discussion, power-sport athlete considerations, and development of this new SCOAT.

Dr. Wilner: Dr. Datta, this is very exciting. I look forward to reading these guidelines in July. I want to thank you for your hard work. I also look forward to talking to you at next year’s meeting. Thank you very much for giving us this update.

Dr. Datta: No problem. It’s my pleasure.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

Morning PT

Tuesdays and Fridays are tough. Not so much because of clinic, but rather because of the 32 minutes before clinic that I’m on the Peloton bike. They are the mornings I dedicate to training VO2max.

Training VO2max, or maximal oxygen consumption, is simple. Spin for a leisurely, easy-breathing, 4 minutes, then for 4 minutes push yourself until you see the light of heaven and wish for death to come. Then relax for 4 minutes again. Repeat this cycle four to six times. Done justly, you will dread Tuesdays and Fridays too. The punishing cycle of a 4-minute push, then 4-minute recovery is, however, an excellent way to improve cardiovascular fitness. And no, I’m not training for the Boston Marathon, so why am I working so hard? Because I’m training for marathon clinic days for the next 20 years.

Now more than ever, I feel we have to be physically fit to deal with a physicians’ day’s work. It’s exhausting. The root cause is too much work, yes, but I believe being physically fit could help.

I was talking to an 86-year-old patient about this very topic recently. He was short, with a well-manicured goatee and shiny head. He stuck his arm out to shake my hand. “Glad we’re back to handshakes again, doc.” His grip was that of a 30-year-old. “Buff” you’d likely describe him: He is noticeably muscular, not a skinny old man. He’s an old Navy Master Chief who started a business in wholesale flowers, which distributes all over the United States. And he’s still working full time. Impressed, I asked his secret for such vigor. PT, he replied.

PT, or physical training, is a foundational element of the Navy. Every sailor starts his or her day with morning PT before carrying out their duties. Some 30 years later, this guy is still getting after it. He does push-ups, sit-ups, and pull-ups nearly every morning. Morning PT is what he attributes to his success not only in health, but also business. As he sees it, he has the business savvy and experience of an old guy and the energy and stamina of a college kid. A good combination for a successful life.

I’ve always been pretty fit. Lately, I’ve been trying to take it to the next level, to not just be “physically active,” but rather “high-performance fit.” There are plenty of sources for instruction; how to stay young and healthy isn’t a new idea after all. I mean, Herodotus wrote of finding the Fountain of Youth in the 5th century BCE. A couple thousand years later, it’s still on trend. One of my favorite sages giving health span advice is Peter Attia, MD. I’ve been a fan since I met him at TEDMED in 2013 and I marvel at the astounding body of work he has created since. A Johns Hopkins–trained surgeon, he has spent his career reviewing the scientific literature about longevity and sharing it as actionable content. His book, “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2023) is a nice summary of his work. I recommend it.

Right now I’m switching between type 2 muscle fiber work (lots of jumping like my 2-year-old) and cardiovascular training including the aforementioned VO2max work. I cannot say that my patient inbox is any cleaner, or that I’m faster in the office, but I’m not flagging by the end of the day anymore. Master Chief challenged me to match his 10 pull-ups before he returns for his follow up visit. I’ll gladly give up Peloton sprints to work on that.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Tuesdays and Fridays are tough. Not so much because of clinic, but rather because of the 32 minutes before clinic that I’m on the Peloton bike. They are the mornings I dedicate to training VO2max.

Training VO2max, or maximal oxygen consumption, is simple. Spin for a leisurely, easy-breathing, 4 minutes, then for 4 minutes push yourself until you see the light of heaven and wish for death to come. Then relax for 4 minutes again. Repeat this cycle four to six times. Done justly, you will dread Tuesdays and Fridays too. The punishing cycle of a 4-minute push, then 4-minute recovery is, however, an excellent way to improve cardiovascular fitness. And no, I’m not training for the Boston Marathon, so why am I working so hard? Because I’m training for marathon clinic days for the next 20 years.

Now more than ever, I feel we have to be physically fit to deal with a physicians’ day’s work. It’s exhausting. The root cause is too much work, yes, but I believe being physically fit could help.

I was talking to an 86-year-old patient about this very topic recently. He was short, with a well-manicured goatee and shiny head. He stuck his arm out to shake my hand. “Glad we’re back to handshakes again, doc.” His grip was that of a 30-year-old. “Buff” you’d likely describe him: He is noticeably muscular, not a skinny old man. He’s an old Navy Master Chief who started a business in wholesale flowers, which distributes all over the United States. And he’s still working full time. Impressed, I asked his secret for such vigor. PT, he replied.

PT, or physical training, is a foundational element of the Navy. Every sailor starts his or her day with morning PT before carrying out their duties. Some 30 years later, this guy is still getting after it. He does push-ups, sit-ups, and pull-ups nearly every morning. Morning PT is what he attributes to his success not only in health, but also business. As he sees it, he has the business savvy and experience of an old guy and the energy and stamina of a college kid. A good combination for a successful life.

I’ve always been pretty fit. Lately, I’ve been trying to take it to the next level, to not just be “physically active,” but rather “high-performance fit.” There are plenty of sources for instruction; how to stay young and healthy isn’t a new idea after all. I mean, Herodotus wrote of finding the Fountain of Youth in the 5th century BCE. A couple thousand years later, it’s still on trend. One of my favorite sages giving health span advice is Peter Attia, MD. I’ve been a fan since I met him at TEDMED in 2013 and I marvel at the astounding body of work he has created since. A Johns Hopkins–trained surgeon, he has spent his career reviewing the scientific literature about longevity and sharing it as actionable content. His book, “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2023) is a nice summary of his work. I recommend it.

Right now I’m switching between type 2 muscle fiber work (lots of jumping like my 2-year-old) and cardiovascular training including the aforementioned VO2max work. I cannot say that my patient inbox is any cleaner, or that I’m faster in the office, but I’m not flagging by the end of the day anymore. Master Chief challenged me to match his 10 pull-ups before he returns for his follow up visit. I’ll gladly give up Peloton sprints to work on that.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Tuesdays and Fridays are tough. Not so much because of clinic, but rather because of the 32 minutes before clinic that I’m on the Peloton bike. They are the mornings I dedicate to training VO2max.

Training VO2max, or maximal oxygen consumption, is simple. Spin for a leisurely, easy-breathing, 4 minutes, then for 4 minutes push yourself until you see the light of heaven and wish for death to come. Then relax for 4 minutes again. Repeat this cycle four to six times. Done justly, you will dread Tuesdays and Fridays too. The punishing cycle of a 4-minute push, then 4-minute recovery is, however, an excellent way to improve cardiovascular fitness. And no, I’m not training for the Boston Marathon, so why am I working so hard? Because I’m training for marathon clinic days for the next 20 years.

Now more than ever, I feel we have to be physically fit to deal with a physicians’ day’s work. It’s exhausting. The root cause is too much work, yes, but I believe being physically fit could help.

I was talking to an 86-year-old patient about this very topic recently. He was short, with a well-manicured goatee and shiny head. He stuck his arm out to shake my hand. “Glad we’re back to handshakes again, doc.” His grip was that of a 30-year-old. “Buff” you’d likely describe him: He is noticeably muscular, not a skinny old man. He’s an old Navy Master Chief who started a business in wholesale flowers, which distributes all over the United States. And he’s still working full time. Impressed, I asked his secret for such vigor. PT, he replied.

PT, or physical training, is a foundational element of the Navy. Every sailor starts his or her day with morning PT before carrying out their duties. Some 30 years later, this guy is still getting after it. He does push-ups, sit-ups, and pull-ups nearly every morning. Morning PT is what he attributes to his success not only in health, but also business. As he sees it, he has the business savvy and experience of an old guy and the energy and stamina of a college kid. A good combination for a successful life.

I’ve always been pretty fit. Lately, I’ve been trying to take it to the next level, to not just be “physically active,” but rather “high-performance fit.” There are plenty of sources for instruction; how to stay young and healthy isn’t a new idea after all. I mean, Herodotus wrote of finding the Fountain of Youth in the 5th century BCE. A couple thousand years later, it’s still on trend. One of my favorite sages giving health span advice is Peter Attia, MD. I’ve been a fan since I met him at TEDMED in 2013 and I marvel at the astounding body of work he has created since. A Johns Hopkins–trained surgeon, he has spent his career reviewing the scientific literature about longevity and sharing it as actionable content. His book, “Outlive: The Science and Art of Longevity” (New York: Penguin Random House, 2023) is a nice summary of his work. I recommend it.

Right now I’m switching between type 2 muscle fiber work (lots of jumping like my 2-year-old) and cardiovascular training including the aforementioned VO2max work. I cannot say that my patient inbox is any cleaner, or that I’m faster in the office, but I’m not flagging by the end of the day anymore. Master Chief challenged me to match his 10 pull-ups before he returns for his follow up visit. I’ll gladly give up Peloton sprints to work on that.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

The antimicrobial peptide that even Pharma can love

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

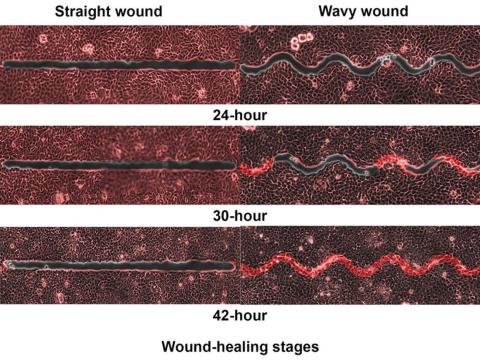

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Fastest peptide north, south, east, aaaaand west of the Pecos

Bacterial infections are supposed to be simple. You get infected, you get an antibiotic to treat it. Easy. Some bacteria, though, don’t play by the rules. Those antibiotics may kill 99.9% of germs, but what about the 0.1% that gets left behind? With their fallen comrades out of the way, the accidentally drug resistant species are free to inherit the Earth.

Antibiotic resistance is thus a major concern for the medical community. Naturally, anything that prevents doctors from successfully curing sick people is a priority. Unless you’re a major pharmaceutical company that has been loath to develop new drugs that can beat antibiotic-resistant bacteria. Blah blah, time and money, blah blah, long time between development and market application, blah blah, no profit. We all know the story with pharmaceutical companies.

Research from other sources has continued, however, and Brazilian scientists recently published research involving a peptide known as plantaricin 149. This peptide, derived from the bacterium Lactobacillus plantarum, has been known for nearly 30 years to have antibacterial properties. Pln149 in its natural state, though, is not particularly efficient at bacteria-killing. Fortunately, we have science and technology on our side.

The researchers synthesized 20 analogs of Pln149, of which Pln149-PEP20 had the best results. The elegantly named compound is less than half the size of the original peptide, less toxic, and far better at killing any and all drug-resistant bacteria the researchers threw at it. How much better? Pln149-PEP20 started killing bacteria less than an hour after being introduced in lab trials.

The research is just in its early days – just because something is less toxic doesn’t necessarily mean you want to go and help yourself to it – but we can only hope that those lovely pharmaceutical companies deign to look down upon us and actually develop a drug utilizing Pln149-PEP20 to, you know, actually help sick people, instead of trying to build monopolies or avoiding paying billions in taxes. Yeah, we couldn’t keep a straight face through that last sentence either.

Speed healing: The wavy wound gets the swirl

Did you know that wavy wounds heal faster than straight wounds? Well, we didn’t, but apparently quite a few people did, because somebody has been trying to figure out why wavy wounds heal faster than straight ones. Do the surgeons know about this? How about you dermatologists? Wavy over straight? We’re the media. We’re supposed to report this kind of stuff. Maybe hit us with a tweet next time you do something important, or push a TikTok our way, okay?

You could be more like the investigators at Nanyang Technological University in Singapore, who figured out the why and then released a statement about it.

They created synthetic wounds – some straight, some wavy – in micropatterned hydrogel substrates that mimicked human skin. Then they used an advanced optical technique known as particle image velocimetry to measure fluid flow and learn how cells moved to close the wound gaps.

The wavy wounds “induced more complex collective cell movements, such as a swirly, vortex-like motion,” according to the written statement from NTU Singapore. In the straight wounds, cell movements paralleled the wound front, “moving in straight lines like a marching band,” they pointed out, unlike some researchers who never call us unless they need money.

Complex epithelial cell movements are better, it turns out. Over an observation period of 64 hours the NTU team found that the healing efficiency of wavy gaps – measured by the area covered by the cells over time – is nearly five times faster than straight gaps.

The complex motion “enabled cells to quickly connect with similar cells on the opposite site of the wound edge, forming a bridge and closing the wavy wound gaps faster than straight gaps,” explained lead author Xu Hongmei, a doctoral student at NTU’s School of Mechanical and Aerospace Engineering, who seems to have time to toss out a tumblr or two to keep the press informed.

As for the rest of you, would it kill you to pick up a phone once in a while? Maybe let a journalist know that you’re still alive? We have feelings too, you know, and we worry.

A little Jekyll, a little Hyde, and a little shop of horrors

More “Little Shop of Horrors” references are coming, so be prepared.

We begin with Triphyophyllum peltatum. This woody vine is of great interest to medical and pharmaceutical researchers because its constituents have shown promise against pancreatic cancer and leukemia cells, among others, along with the pathogens that cause malaria and other diseases. There is another side, however. T. peltatum also has a tendency to turn into a realistic Audrey II when deprived.

No, of course they’re not craving human flesh, but it does become … carnivorous in its appetite.

T. peltatum, native to the West African tropics and not found in a New York florist shop, has the unique ability to change its diet and development based on the environmental circumstances. For some unknown reason, the leaves would develop adhesive traps in the form of sticky drops that capture insect prey. The plant is notoriously hard to grow, however, so no one could study the transformation under lab conditions. Until now.

A group of German scientists “exposed the plant to different stress factors, including deficiencies of various nutrients, and studied how it responded to each,” said Dr. Traud Winkelmann of Leibniz University Hannover. “Only in one case were we able to observe the formation of traps: in the case of a lack of phosphorus.”

Well, there you have it: phosphorus. We need it for healthy bones and teeth, which this plant doesn’t have to worry about, unlike its Tony Award–nominated counterpart. The investigators hope that their findings could lead to “future molecular analyses that will help understand the origins of carnivory,” but we’re guessing that a certain singing alien species will be left out of that research.

Expunging ‘penicillin allergy’: Your questions answered

Last month, I described a 28-year-old patient with a history of injection drug use who presented with pain in his left forearm. His history showed that, within the past 2 years, he’d been seen for cutaneous infections multiple times as an outpatient and in the emergency department. His records indicated that he was diagnosed with a penicillin allergy as a child when he developed a rash after receiving amoxicillin. I believed the next course of action should be to test for a penicillin allergy with an oral amoxicillin challenge.

Thank you for your excellent questions regarding this case. Great to hear the enthusiasm for testing for penicillin allergy!

One question focused on the course of action in the case of a mild or moderate IgE-mediated reaction after a single dose test with amoxicillin. Treatment for these reactions should include an antihistamine. I would reserve intravenous antihistamines for more severe cases, which also require treatment with a course of corticosteroids. However, the risk for a moderate to severe reaction to amoxicillin on retesting is quite low.

Clinicians need to exercise caution in the use of systemic corticosteroids. These drugs can be lifesaving, but even short courses of corticosteroids are associated with potentially serious adverse events. In a review of adverse events associated with short-course systemic corticosteroids among children, the rate of vomiting was 5.4%; behavioral change, 4.7%; and sleep disturbance, 4.3%. One child died after contracting herpes zoster, more than one-third of children developed elevated blood pressure, and 81.1% had evidence of suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Among adults, short courses of systemic corticosteroids are associated with acute increases in the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hypertension. Cumulative exposure to short courses of corticosteroids over time results in higher risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Another question prompted by this young man’s case focused on the durability of IgE reactions against penicillin. The IgE response to penicillin does indeed wane over time; 80% of patients with a previous true penicillin allergy can tolerate the antibiotic after 10 years. Thus, about 95% of patients with a remote history of penicillin allergy are tolerant of penicillin, and testing can be performed using the algorithm described.

Clinicians should avoid applying current guidelines for the evaluation of patients with penicillin allergy to other common drug allergies. The overall prevalence of sulfonamide allergy is 3%-8%, and the vast majority of these reactions follow treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Sulfa allergy is even more common among persons living with HIV infection. The natural history of sulfa allergy is not as well established as penicillin allergy. Allergy testing is encouraged in these cases. Graded oral challenge testing is best reserved for patients who are unlikely to have a true sulfa allergy based on their history.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last month, I described a 28-year-old patient with a history of injection drug use who presented with pain in his left forearm. His history showed that, within the past 2 years, he’d been seen for cutaneous infections multiple times as an outpatient and in the emergency department. His records indicated that he was diagnosed with a penicillin allergy as a child when he developed a rash after receiving amoxicillin. I believed the next course of action should be to test for a penicillin allergy with an oral amoxicillin challenge.

Thank you for your excellent questions regarding this case. Great to hear the enthusiasm for testing for penicillin allergy!

One question focused on the course of action in the case of a mild or moderate IgE-mediated reaction after a single dose test with amoxicillin. Treatment for these reactions should include an antihistamine. I would reserve intravenous antihistamines for more severe cases, which also require treatment with a course of corticosteroids. However, the risk for a moderate to severe reaction to amoxicillin on retesting is quite low.

Clinicians need to exercise caution in the use of systemic corticosteroids. These drugs can be lifesaving, but even short courses of corticosteroids are associated with potentially serious adverse events. In a review of adverse events associated with short-course systemic corticosteroids among children, the rate of vomiting was 5.4%; behavioral change, 4.7%; and sleep disturbance, 4.3%. One child died after contracting herpes zoster, more than one-third of children developed elevated blood pressure, and 81.1% had evidence of suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Among adults, short courses of systemic corticosteroids are associated with acute increases in the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hypertension. Cumulative exposure to short courses of corticosteroids over time results in higher risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Another question prompted by this young man’s case focused on the durability of IgE reactions against penicillin. The IgE response to penicillin does indeed wane over time; 80% of patients with a previous true penicillin allergy can tolerate the antibiotic after 10 years. Thus, about 95% of patients with a remote history of penicillin allergy are tolerant of penicillin, and testing can be performed using the algorithm described.

Clinicians should avoid applying current guidelines for the evaluation of patients with penicillin allergy to other common drug allergies. The overall prevalence of sulfonamide allergy is 3%-8%, and the vast majority of these reactions follow treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Sulfa allergy is even more common among persons living with HIV infection. The natural history of sulfa allergy is not as well established as penicillin allergy. Allergy testing is encouraged in these cases. Graded oral challenge testing is best reserved for patients who are unlikely to have a true sulfa allergy based on their history.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Last month, I described a 28-year-old patient with a history of injection drug use who presented with pain in his left forearm. His history showed that, within the past 2 years, he’d been seen for cutaneous infections multiple times as an outpatient and in the emergency department. His records indicated that he was diagnosed with a penicillin allergy as a child when he developed a rash after receiving amoxicillin. I believed the next course of action should be to test for a penicillin allergy with an oral amoxicillin challenge.

Thank you for your excellent questions regarding this case. Great to hear the enthusiasm for testing for penicillin allergy!

One question focused on the course of action in the case of a mild or moderate IgE-mediated reaction after a single dose test with amoxicillin. Treatment for these reactions should include an antihistamine. I would reserve intravenous antihistamines for more severe cases, which also require treatment with a course of corticosteroids. However, the risk for a moderate to severe reaction to amoxicillin on retesting is quite low.

Clinicians need to exercise caution in the use of systemic corticosteroids. These drugs can be lifesaving, but even short courses of corticosteroids are associated with potentially serious adverse events. In a review of adverse events associated with short-course systemic corticosteroids among children, the rate of vomiting was 5.4%; behavioral change, 4.7%; and sleep disturbance, 4.3%. One child died after contracting herpes zoster, more than one-third of children developed elevated blood pressure, and 81.1% had evidence of suppression of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis.

Among adults, short courses of systemic corticosteroids are associated with acute increases in the risks for gastrointestinal bleeding and hypertension. Cumulative exposure to short courses of corticosteroids over time results in higher risks for obesity, type 2 diabetes, and osteoporosis.

Another question prompted by this young man’s case focused on the durability of IgE reactions against penicillin. The IgE response to penicillin does indeed wane over time; 80% of patients with a previous true penicillin allergy can tolerate the antibiotic after 10 years. Thus, about 95% of patients with a remote history of penicillin allergy are tolerant of penicillin, and testing can be performed using the algorithm described.

Clinicians should avoid applying current guidelines for the evaluation of patients with penicillin allergy to other common drug allergies. The overall prevalence of sulfonamide allergy is 3%-8%, and the vast majority of these reactions follow treatment with trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. Sulfa allergy is even more common among persons living with HIV infection. The natural history of sulfa allergy is not as well established as penicillin allergy. Allergy testing is encouraged in these cases. Graded oral challenge testing is best reserved for patients who are unlikely to have a true sulfa allergy based on their history.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Emotional eating isn’t all emotional

“Food gives me ‘hugs,’ ” Ms. S* said as her eyes lit up. Finally, after weeks of working together, she could articulate her complex relationship with food. She had been struggling to explain why she continued to eat when she was full or consumed foods she knew wouldn’t help her health.

Like millions of people struggling with their weight or the disease of obesity, Ms. S had tried multiple diets and programs but continued to return to unhelpful eating patterns. Ms. S was an emotional eater, and the pandemic only worsened her emotional eating. As a single professional forced to work from home during the pandemic, she became lonely. She went from working in a busy downtown office, training for half-marathons, and teaching live workout sessions to being alone daily. Her only “real” human interaction was when she ordered daily delivery meals of her favorite comfort foods. As a person with type 2 diabetes, she knew that her delivery habit was wrecking her health, but willpower wasn’t enough to make her stop.