User login

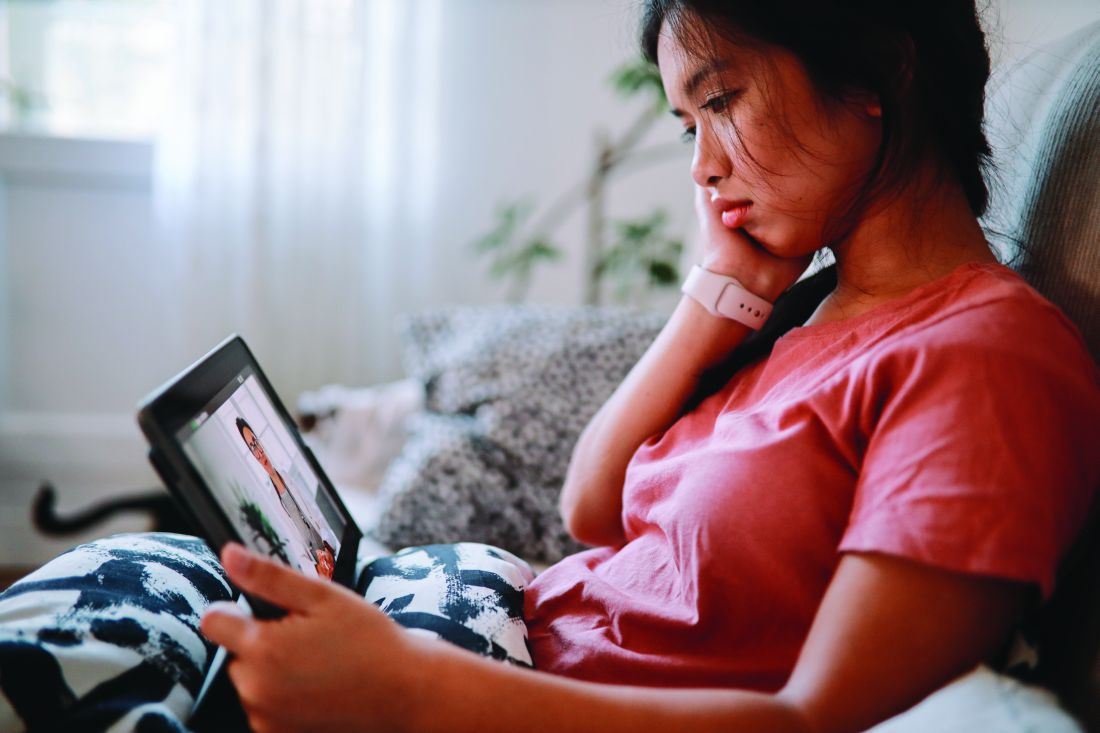

Five reasons why medical meetings will never be the same

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virtual medical meeting is now the norm. And while it’s admirable that key data are being disseminated (often for free), there is no escaping the fact that it is a fundamentally different and lesser experience.

Watching from home, most of us split our attention between live streams of the meeting and work and family obligations. There is far less urgency when early live presentations are recorded and can be viewed later.

In terms of discussing the data, Twitter may offer broader participation than a live meeting, yet only a small number of attendees actively engage online.

And the exhibit halls for these online meetings? With neither free coffee nor company-branded tchotchkes, I expect that they have virtual tumbleweeds blowing through and crickets chirping.

Even still, the virtual meeting experience, while inferior to the live one, is a tremendous advance. It should never be banished as a historical footnote but rather should remain an option. It’s analogous to watching the Super Bowl at home: Obviously, it’s not the same as being there, but it’s a terrific alternative. Like telemedicine, this pandemic has provided a critical proof of concept that there is a better model.

Reshaping the medical meeting

Let’s consider five reasons why medical meetings should be permanently reshaped by this pandemic.

This pandemic isn’t going away in 2020. While nearly every country has done a far better job than the United States of containing COVID-19 thus far, outbreaks remain a problem wherever crowds assemble. You’d be hard-pressed to devise a setting more conducive to mass spread than a conference of 20,000 attendees from all over the world sitting alongside each other cheek to jowl for 5 days. Worse yet is the thought of them returning home and infecting their patients, families, and friends. What medical society wants to be remembered for creating a COVID-19 superspreader event? Professional medical societies will need to offer this option as the safest alternative moving forward.

Virtual learning still conveys the most important content. Despite the many social benefits of a live meeting, its core purpose is to disseminate new research and current and emerging treatment options. Virtual meetings have proven that this format can effectively deliver the content, and not as a secondary offering but as the sole platform in real time.

Virtual learning levels the playing field. Traveling to attend conferences typically costs thousands of dollars, accounting for the registration fees, inflated hotel rates, ground transportation, and meals out for days on end. Most meetings also demand several days away from our work and families, forcing many of us to work extra in the days before we leave and upon our return. Parents and those with commitments at home also face special challenges. For international participants, the financial and time costs are even greater. A virtual meeting helps overcome these hurdles and erases barriers that have long precluded many from attending a conference.

Virtual learning is efficient and comfortable. Virtual meetings over the past 6 months have given us a glimpse of an astonishingly more efficient form. If the content seems of a lower magnitude without the fanfare of a live conference, it is in part because so much of a live meeting is spent walking a mile between session rooms, waiting in concession or taxi lines, sitting in traffic between venues, or simply waiting for a session to begin. All of that has been replaced with time that you can use productively in between video sessions viewed either live or on demand. And with a virtual meeting, you can comfortably watch the sessions. There’s no need to stand along the back wall of an overcrowded room or step over 10 people to squeeze into an open middle seat. You can be focused, rather than having an end-of-day presentation wash over you as your eyes cross because you’ve been running around for the past 12 hours.

Virtual learning and social media will only improve. While virtual meetings unquestionably have limitations, it’s important to acknowledge that the successes thus far still represent only the earliest forays into this endeavor. In-person meetings evolved to their present form over centuries. In contrast, virtual meetings are being cobbled together within a few weeks or months. They can only be expected to improve as presenters adapt their skills to the online audience and new tools improve virtual discussions.

I am not implying that live meetings will or should be replaced by virtual ones. We still need that experience of trainees and experts presenting to a live audience and discussing the results together, all while sharing the energy of the moment. But there should be room for both a live conference and a virtual version.

Practically speaking, it is unclear whether professional societies could forgo the revenue they receive from registration fees, meeting sponsorships, and corporate exhibits. Yet, there are certainly ways to obtain sponsorship revenue for a virtual program. Even if the virtual version of a conference costs far less than attending in person, there is plenty of room between that number and free. It costs remarkably little for a professional society to share its content, and virtual offerings further the mission of distributing this content broadly.

We should not rush to return to the previous status quo. Despite their limitations, virtual meetings have brought a new, higher standard of access and efficiency for sharing important new data and treatment options in medicine.

H. Jack West, MD, associate clinical professor and executive director of employer services at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, Calif., regularly comments on lung cancer for Medscape. West serves as web editor for JAMA Oncology, edits and writes several sections on lung cancer for UpToDate, and leads a wide range of continuing education programs and other educational programs, including hosting the audio podcast West Wind.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virtual medical meeting is now the norm. And while it’s admirable that key data are being disseminated (often for free), there is no escaping the fact that it is a fundamentally different and lesser experience.

Watching from home, most of us split our attention between live streams of the meeting and work and family obligations. There is far less urgency when early live presentations are recorded and can be viewed later.

In terms of discussing the data, Twitter may offer broader participation than a live meeting, yet only a small number of attendees actively engage online.

And the exhibit halls for these online meetings? With neither free coffee nor company-branded tchotchkes, I expect that they have virtual tumbleweeds blowing through and crickets chirping.

Even still, the virtual meeting experience, while inferior to the live one, is a tremendous advance. It should never be banished as a historical footnote but rather should remain an option. It’s analogous to watching the Super Bowl at home: Obviously, it’s not the same as being there, but it’s a terrific alternative. Like telemedicine, this pandemic has provided a critical proof of concept that there is a better model.

Reshaping the medical meeting

Let’s consider five reasons why medical meetings should be permanently reshaped by this pandemic.

This pandemic isn’t going away in 2020. While nearly every country has done a far better job than the United States of containing COVID-19 thus far, outbreaks remain a problem wherever crowds assemble. You’d be hard-pressed to devise a setting more conducive to mass spread than a conference of 20,000 attendees from all over the world sitting alongside each other cheek to jowl for 5 days. Worse yet is the thought of them returning home and infecting their patients, families, and friends. What medical society wants to be remembered for creating a COVID-19 superspreader event? Professional medical societies will need to offer this option as the safest alternative moving forward.

Virtual learning still conveys the most important content. Despite the many social benefits of a live meeting, its core purpose is to disseminate new research and current and emerging treatment options. Virtual meetings have proven that this format can effectively deliver the content, and not as a secondary offering but as the sole platform in real time.

Virtual learning levels the playing field. Traveling to attend conferences typically costs thousands of dollars, accounting for the registration fees, inflated hotel rates, ground transportation, and meals out for days on end. Most meetings also demand several days away from our work and families, forcing many of us to work extra in the days before we leave and upon our return. Parents and those with commitments at home also face special challenges. For international participants, the financial and time costs are even greater. A virtual meeting helps overcome these hurdles and erases barriers that have long precluded many from attending a conference.

Virtual learning is efficient and comfortable. Virtual meetings over the past 6 months have given us a glimpse of an astonishingly more efficient form. If the content seems of a lower magnitude without the fanfare of a live conference, it is in part because so much of a live meeting is spent walking a mile between session rooms, waiting in concession or taxi lines, sitting in traffic between venues, or simply waiting for a session to begin. All of that has been replaced with time that you can use productively in between video sessions viewed either live or on demand. And with a virtual meeting, you can comfortably watch the sessions. There’s no need to stand along the back wall of an overcrowded room or step over 10 people to squeeze into an open middle seat. You can be focused, rather than having an end-of-day presentation wash over you as your eyes cross because you’ve been running around for the past 12 hours.

Virtual learning and social media will only improve. While virtual meetings unquestionably have limitations, it’s important to acknowledge that the successes thus far still represent only the earliest forays into this endeavor. In-person meetings evolved to their present form over centuries. In contrast, virtual meetings are being cobbled together within a few weeks or months. They can only be expected to improve as presenters adapt their skills to the online audience and new tools improve virtual discussions.

I am not implying that live meetings will or should be replaced by virtual ones. We still need that experience of trainees and experts presenting to a live audience and discussing the results together, all while sharing the energy of the moment. But there should be room for both a live conference and a virtual version.

Practically speaking, it is unclear whether professional societies could forgo the revenue they receive from registration fees, meeting sponsorships, and corporate exhibits. Yet, there are certainly ways to obtain sponsorship revenue for a virtual program. Even if the virtual version of a conference costs far less than attending in person, there is plenty of room between that number and free. It costs remarkably little for a professional society to share its content, and virtual offerings further the mission of distributing this content broadly.

We should not rush to return to the previous status quo. Despite their limitations, virtual meetings have brought a new, higher standard of access and efficiency for sharing important new data and treatment options in medicine.

H. Jack West, MD, associate clinical professor and executive director of employer services at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, Calif., regularly comments on lung cancer for Medscape. West serves as web editor for JAMA Oncology, edits and writes several sections on lung cancer for UpToDate, and leads a wide range of continuing education programs and other educational programs, including hosting the audio podcast West Wind.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic, the virtual medical meeting is now the norm. And while it’s admirable that key data are being disseminated (often for free), there is no escaping the fact that it is a fundamentally different and lesser experience.

Watching from home, most of us split our attention between live streams of the meeting and work and family obligations. There is far less urgency when early live presentations are recorded and can be viewed later.

In terms of discussing the data, Twitter may offer broader participation than a live meeting, yet only a small number of attendees actively engage online.

And the exhibit halls for these online meetings? With neither free coffee nor company-branded tchotchkes, I expect that they have virtual tumbleweeds blowing through and crickets chirping.

Even still, the virtual meeting experience, while inferior to the live one, is a tremendous advance. It should never be banished as a historical footnote but rather should remain an option. It’s analogous to watching the Super Bowl at home: Obviously, it’s not the same as being there, but it’s a terrific alternative. Like telemedicine, this pandemic has provided a critical proof of concept that there is a better model.

Reshaping the medical meeting

Let’s consider five reasons why medical meetings should be permanently reshaped by this pandemic.

This pandemic isn’t going away in 2020. While nearly every country has done a far better job than the United States of containing COVID-19 thus far, outbreaks remain a problem wherever crowds assemble. You’d be hard-pressed to devise a setting more conducive to mass spread than a conference of 20,000 attendees from all over the world sitting alongside each other cheek to jowl for 5 days. Worse yet is the thought of them returning home and infecting their patients, families, and friends. What medical society wants to be remembered for creating a COVID-19 superspreader event? Professional medical societies will need to offer this option as the safest alternative moving forward.

Virtual learning still conveys the most important content. Despite the many social benefits of a live meeting, its core purpose is to disseminate new research and current and emerging treatment options. Virtual meetings have proven that this format can effectively deliver the content, and not as a secondary offering but as the sole platform in real time.

Virtual learning levels the playing field. Traveling to attend conferences typically costs thousands of dollars, accounting for the registration fees, inflated hotel rates, ground transportation, and meals out for days on end. Most meetings also demand several days away from our work and families, forcing many of us to work extra in the days before we leave and upon our return. Parents and those with commitments at home also face special challenges. For international participants, the financial and time costs are even greater. A virtual meeting helps overcome these hurdles and erases barriers that have long precluded many from attending a conference.

Virtual learning is efficient and comfortable. Virtual meetings over the past 6 months have given us a glimpse of an astonishingly more efficient form. If the content seems of a lower magnitude without the fanfare of a live conference, it is in part because so much of a live meeting is spent walking a mile between session rooms, waiting in concession or taxi lines, sitting in traffic between venues, or simply waiting for a session to begin. All of that has been replaced with time that you can use productively in between video sessions viewed either live or on demand. And with a virtual meeting, you can comfortably watch the sessions. There’s no need to stand along the back wall of an overcrowded room or step over 10 people to squeeze into an open middle seat. You can be focused, rather than having an end-of-day presentation wash over you as your eyes cross because you’ve been running around for the past 12 hours.

Virtual learning and social media will only improve. While virtual meetings unquestionably have limitations, it’s important to acknowledge that the successes thus far still represent only the earliest forays into this endeavor. In-person meetings evolved to their present form over centuries. In contrast, virtual meetings are being cobbled together within a few weeks or months. They can only be expected to improve as presenters adapt their skills to the online audience and new tools improve virtual discussions.

I am not implying that live meetings will or should be replaced by virtual ones. We still need that experience of trainees and experts presenting to a live audience and discussing the results together, all while sharing the energy of the moment. But there should be room for both a live conference and a virtual version.

Practically speaking, it is unclear whether professional societies could forgo the revenue they receive from registration fees, meeting sponsorships, and corporate exhibits. Yet, there are certainly ways to obtain sponsorship revenue for a virtual program. Even if the virtual version of a conference costs far less than attending in person, there is plenty of room between that number and free. It costs remarkably little for a professional society to share its content, and virtual offerings further the mission of distributing this content broadly.

We should not rush to return to the previous status quo. Despite their limitations, virtual meetings have brought a new, higher standard of access and efficiency for sharing important new data and treatment options in medicine.

H. Jack West, MD, associate clinical professor and executive director of employer services at City of Hope Comprehensive Cancer Center in Duarte, Calif., regularly comments on lung cancer for Medscape. West serves as web editor for JAMA Oncology, edits and writes several sections on lung cancer for UpToDate, and leads a wide range of continuing education programs and other educational programs, including hosting the audio podcast West Wind.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Identifying ovarian malignancy is not so easy

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

When an ovarian mass is anticipated or known, following evaluation of a patient’s history and physician examination, imaging via transvaginal and often abdominal ultrasound is the very next step. This evaluation likely will include both gray-scale and color Doppler examination. The initial concern always must be to identify ovarian malignancy.

Despite morphological scoring systems as well as the use of Doppler ultrasonography, there remains a lack of agreement and acceptance. In a 2008 multicenter study, Timmerman and colleagues evaluated 1,066 patients with 1,233 persistent adnexal tumors via transvaginal grayscale and Doppler ultrasound; 73% were benign tumors, and 27% were malignant tumors. Information on 42 gray-scale ultrasound variables and 6 Doppler variables was collected and evaluated to determine which variables had the highest positive predictive value for a malignant tumor and for a benign mass (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365).

Five simple rules were selected that best predict malignancy (M-rules), as follows:

- Irregular solid tumor.

- Ascites.

- At least four papillary projections.

- Irregular multilocular-solid tumor with a greatest diameter greater than or equal to 10 cm.

- Very high color content on Doppler exam.

The following five simple rules suggested that a mass is benign (B-rules):

- Unilocular cyst.

- Largest solid component less than 7 mm.

- Acoustic shadows.

- Smooth multilocular tumor less than 10 cm.

- No detectable blood flow with Doppler exam.

Unfortunately, despite a sensitivity of 93% and specificity of 90%, and a positive and negative predictive value of 80% and 97%, these 10 simple rules were applicable to only 76% of tumors.

To assist those of us who are not gynecologic oncologists and who are often faced with having to determine whether surgery is recommended, I have elicited the expertise of Jubilee Brown, MD, professor and associate director of gynecologic oncology at the Levine Cancer Institute, Carolinas HealthCare System, in Charlotte, N.C., and the current president of the AAGL, to lead us in a review of evaluating an ovarian mass.

Dr. Miller is professor of obstetrics & gynecology in the department of clinical sciences, Rosalind Franklin University, North Chicago, Ill., and director of minimally invasive gynecologic surgery at Advocate Lutheran General Hospital, Park Ridge, both in Illinois. Email him at obnews@mdedge.com.

How to evaluate a suspicious ovarian mass

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

Ovarian masses are common in women of all ages. It is important not to miss even one ovarian cancer, but we must also identify masses that will resolve on their own over time to avoid overtreatment. These concurrent goals of excluding malignancy while not overtreating patients are the basis for management of the pelvic mass. Additionally, fertility preservation is important when surgery is performed in a reproductive-aged woman.

An ovarian mass may be anything from a simple functional or physiologic cyst to an endometrioma to an epithelial carcinoma, a germ-cell tumor, or a stromal tumor (the latter three of which may metastasize). Across the general population, women have a 5%-10% lifetime risk of needing surgery for a suspected ovarian mass and a 1.4% (1 in 70) risk that this mass is cancerous. The majority of ovarian cysts or masses therefore are benign.

A thorough history – including family history – and physical examination with appropriate laboratory testing and directed imaging are important first steps for the ob.gyn. Fortunately, we have guidelines and criteria governing not only when observation or surgery is warranted but also when patients should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist. By following these guidelines,1 we are able to achieve the best outcomes.

Transvaginal ultrasound

A 2007 groundbreaking study led by Barbara Goff, MD, demonstrated that there are warning signs for ovarian cancer – symptoms that are significantly associated with malignancy. Dr. Goff and her coinvestigators evaluated the charts of hundreds of patients, including about 150 with ovarian cancer, and found that pelvic/abdominal pressure or pain, bloating, increase in abdominal size, and difficulty eating or feeling full were significantly and independently associated with cancer if these symptoms were present for less than a year and occurred at least 12 times per month.2

A pelvic examination is an integral part of evaluating every patient who has such concerns. That said, pelvic exams have limited ability to identify adnexal masses, especially in women who are obese – and that’s where imaging becomes especially important.

Masses generally can be considered simple or complex based on their appearance. A simple cyst is fluid-filled with thin, smooth walls and the absence of solid components or septations; it is significantly more likely to resolve on its own and is less likely to imply malignancy than a complex cyst, especially in a premenopausal woman. A complex cyst is multiseptated and/or solid – possibly with papillary projections – and is more concerning, especially if there is increased, new vascularity. Making this distinction helps us determine the risk of malignancy.

Transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is the preferred method for imaging, and our threshold for obtaining a TVUS should be very low. Women who have symptoms or concerns that can’t be attributed to a particular condition, and women in whom a mass can be palpated (even if asymptomatic) should have a TVUS. The imaging modality is cost effective and well tolerated by patients, does not expose the patient to ionizing radiation, and should generally be considered first-line imaging.3,4

Size is not predictive of malignancy, but it is important for determining whether surgery is warranted. In our experience, a mass of 8-10 cm or larger on TVUS is at risk of torsion and is unlikely to resolve on its own, even in a premenopausal woman. While large masses generally require surgery, patients of any age who have simple cysts smaller than 8-10 cm generally can be followed with serial exams and ultrasound; spontaneous regression is common.

Doppler ultrasonography is useful for evaluating blood flow in and around an ovarian mass and can be helpful for confirming suspected characteristics of a mass.

Recent studies from the radiology community have looked at the utility of the resistive index – a measure of the impedance and velocity of blood flow – as a predictor of ovarian malignancy. However, we caution against using Doppler to determine whether a mass is benign or malignant, or to determine the necessity of surgery. An abnormal ovary may have what is considered to be a normal resistive index, and the resistive index of a normal ovary may fall within the abnormal range. Doppler flow can be helpful, but it must be combined with other predictive features, like solid components with flow or papillary projections within a cyst, to define a decision about surgery.4,5

Magnetic resonance imaging can be useful in differentiating a fibroid from an ovarian mass, and a CT scan can be helpful in looking for disseminated disease when ovarian cancer is suspected based on ultrasound imaging, physical and history, and serum markers. A CT is useful, for instance, in a patient whose ovary is distended with ascites or who has upper abdominal complaints and a complex cyst. CT, PET, and MRI are not recommended in the initial evaluation of an ovarian mass.

The utility of serum biomarkers

Cancer antigen 125 (CA-125) testing may be helpful – in combination with other findings – for decision-making regarding the likelihood of malignancy and the need to refer patients. CA-125 is like Doppler in that a normal CA-125 cannot eliminate the possibility of cancer, and an abnormal CA-125 does not in and of itself imply malignancy. It’s far from a perfect cancer screening test.

CA-125 is a protein associated with epithelial ovarian malignancies, the type of ovarian cancer most commonly seen in postmenopausal women with genetic predispositions. Its specificity and positive predictive value are much higher in postmenopausal women than in average-risk premenopausal women (those without a family history or a known mutation that predisposes them to ovarian cancer). Levels of the marker are elevated in association with many nonmalignant conditions in premenopausal women – endometriosis, fibroids, and various inflammatory conditions, for instance – so the marker’s utility in this population is limited.

For women who have a family history of ovarian cancer or a known breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1) or BRCA2 mutation, there are some data that suggest that monitoring with CA-125 measurements and TVUS may be a good approach to following patients prior to the age at which risk-reducing surgery can best be performed.

In an adolescent girl or a woman of reproductive age, we think less about epithelial cancer and more about germ-cell and stromal tumors. When a solid mass is palpated or visualized on imaging, we therefore will utilize a different set of markers; alpha-fetoprotein, L-lactate dehydrogenase, and beta-HCG, for instance, have much higher specificity than CA-125 does for germ-cell tumors in this age group and may be helpful in the evaluation. Similarly, in cases of a very large mass resembling a mucinous tumor, a carcinoembryonic antigen may be helpful.

A number of proprietary profiling technologies have been developed to determine the risk of a diagnosed mass being malignant. For instance, the OVA1 assay looks at five serum markers and scores the results, and the Risk of Ovarian Malignancy Algorithm (ROMA) combines the results of three serum markers with menopausal status into a numerical score. Both have Food and Drug Administration approval for use in women in whom surgery has been deemed necessary. These panels can be fairly predictive of risk and may be helpful – especially in rural areas – in determining which women should be referred to a gynecologic oncologist for surgery.

It is important to appreciate that an ovarian cyst or mass should never be biopsied or aspirated lest a malignant tumor confined to one ovary be potentially spread to the peritoneum.

Referral to a gynecologic oncologist

Postmenopausal women with a CA-125 greater than 35 U/mL should be referred, as should postmenopausal women with ascites, those with a nodular or fixed pelvic mass, and those with suspected abdominal or distant metastases (per a CT scan, for instance).

In premenopausal women, ascites, a nodular or fixed mass, and evidence of metastases also are reasons for referral to a gynecologic oncologist. CA-125, again, is much more likely to be elevated for reasons other than malignancy and therefore is not as strong a driver for referral as in postmenopausal women. Patients with markedly elevated levels, however, should probably be referred – particularly when other clinical factors also suggest the need for consultation. While there is no evidence-based threshold for CA-125 in premenopausal women, a CA-125 greater than 200 U/mL is a good cutoff for referral.

For any patient, family history of breast and/or ovarian cancer – especially in a first-degree relative – raises the risk of malignancy and should figure prominently into decision-making regarding referral. Criteria for referral are among the points discussed in the ACOG 2016 Practice Bulletin on Evaluation and Management of Adnexal Masses.1

A note on BRCA mutations

As the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says in its practice bulletin, the most important personal risk factor for ovarian cancer is a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer. Women with such a family history can undergo genetic testing for BRCA mutations and have the opportunity to prevent ovarian cancers when mutations are detected. This simple blood test can save lives.

A modeling study we recently completed – not yet published – shows that it actually would be cost effective to do population screening with BRCA testing performed on every woman at age 30 years.

According to the National Cancer Institute website (last review: 2018), it is estimated that about 44% of women who inherit a BRCA1 mutation, and about 17% of those who inherit a BRAC2 mutation, will develop ovarian cancer by the age of 80 years. By identifying those mutations, women may undergo risk-reducing surgery at designated ages after childbearing is complete and bring their risk down to under 5%.

An international take on managing adnexal masses

- Pelvic ultrasound should include the transvaginal approach. Use Doppler imaging as indicated.

- Although simple ovarian cysts are not precursor lesions to a malignant ovarian cancer, perform a high-quality examination to make sure there are no solid/papillary structures before classifying a cyst as a simple cyst. The risk of progression to malignancy is extremely low, but some follow-up is prudent.

- The most accurate method of characterizing an ovarian mass currently is real-time pattern recognition sonography in the hands of an experienced imager.

- Pattern recognition sonography or a risk model such as the International Ovarian Tumor Analysis (IOTA) Simple Rules can be used to initially characterize an ovarian mass.

- When an ovarian lesion is classified as benign, the patient may be followed conservatively, or if indicated, surgery can be performed by a general gynecologist.

- Serial sonography can be beneficial, but there are limited prospective data to support an exact interval and duration.

- Fewer surgical interventions may result in an increase in sonographic surveillance.

- When an ovarian lesion is considered indeterminate on initial sonography, and after appropriate clinical evaluation, a “second-step” evaluation may include referral to an expert sonologist, serial sonography, application of established risk-prediction models, correlation with serum biomarkers, correlation with MRI, or referral to a gynecologic oncologist for further evaluation.

From the First International Consensus Report on Adnexal Masses: Management Recommendations

Source: Glanc P et al. J Ultrasound Med. 2017 May;36(5):849-63.

Dr. Brown reported that she had received an earlier grant from Aspira Labs, the company that developed the OVA1 assay. Dr. Miller reported that he has no relevant financial disclosures.

References

1. Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Nov. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000001768.

2. Cancer. 2007 Jan 15. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22371.

3. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2015 Mar. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000083.

4. Ultrasound Q. 2013 Mar. doi: 10.1097/RUQ.0b013e3182814d9b.

5. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2008 Jun. doi: 10.1002/uog.5365.

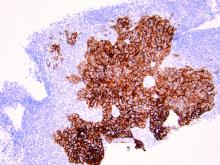

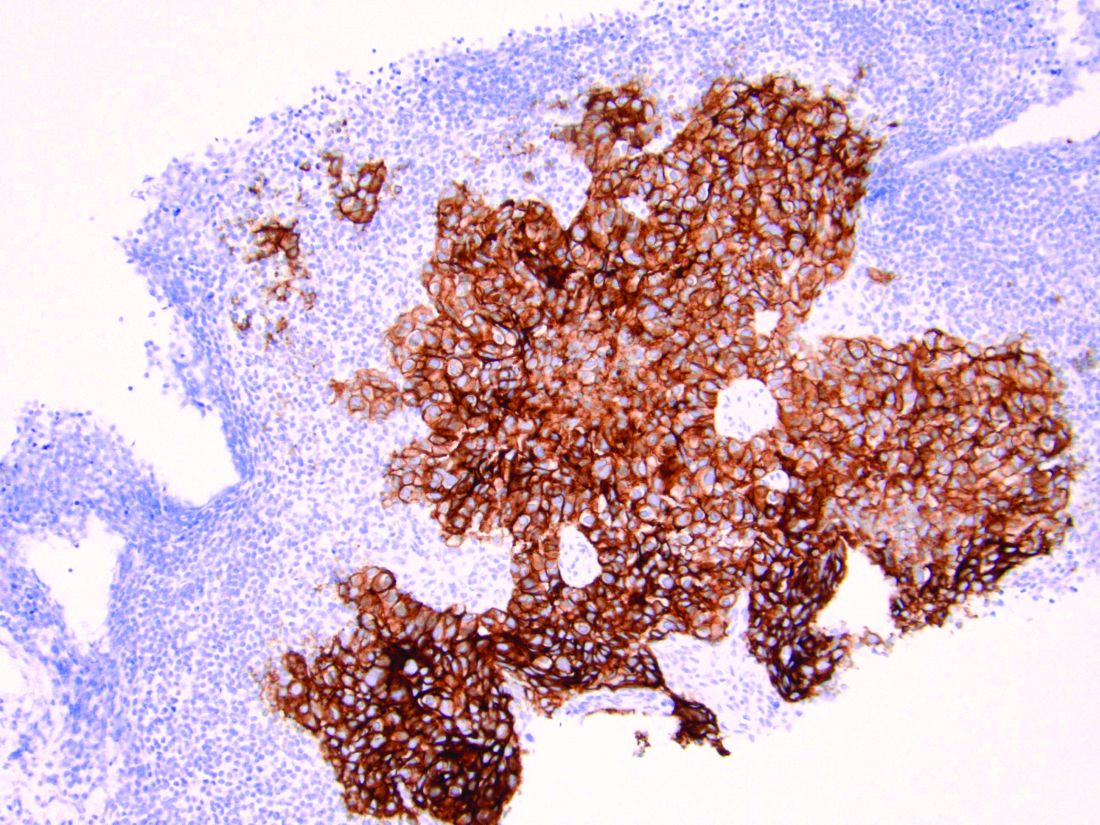

Molecular developments in treatment of UPSC

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is an infrequent but deadly form of endometrial cancer comprising 10% of cases but contributing 40% of deaths from the disease. Recurrence rates are high for this disease. Five-year survival is 55% for all patients and only 70% for stage I disease.1 Patterns of recurrence tend to be distant (extrapelvic and extraabdominal) as frequently as they are localized to the pelvis, and metastases and recurrences are unrelated to the extent of uterine disease (such as myometrial invasion). It is for these reasons that the recommended course of adjuvant therapy for this disease is systemic therapy (typically six doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy) with consideration for radiation to the vagina or pelvis to consolidate pelvic and vaginal control.2 This differs from early-stage high/intermediate–risk endometrioid adenocarcinomas, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has not been found to be helpful.

Because of the lower incidence of UPSC, it frequently has been studied alongside endometrioid cell types in clinical trials which explore novel adjuvant therapies. However, UPSC is biologically distinct from endometrioid endometrial cancers, which likely results in inferior clinical responses to conventional interventions. Fortunately we are beginning to better understand UPSC at a molecular level, and advancements are being made in the targeted therapies for these patients that are unique, compared with those applied to other cancer subtypes.

As discussed above, UPSC is a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer. Histologically it is characterized by a precursor lesion of endometrial glandular dysplasia progressing to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIC). Histologically it presents with a highly atypical slit-like glandular configuration, which appears similar to serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and ovary. Molecularly these tumors commonly manifest mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which are both genes associated with oncogenic potential.1 While most UPSC tumors have loss of expression in hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone, 25%-30% of cases overexpress the tyrosine kinase receptor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).3-5 This has proven to provide an exciting target for therapeutic interventions.

A target for therapeutic intervention

HER2 is a transmembrane receptor which, when activated, signals complex downstream pathways responsible for cellular proliferation, dedifferentiation, and metastasis. In a recent multi-institutional analysis of early-stage UPSC, HER2 overexpression was identified among 25% of cases.4 Approximately 30% of cases of advanced disease manifest overexpression of this biomarker.5 HER2 overexpression (HER2-positive status) is significantly associated with higher rates of recurrence and mortality, even among patients treated with conventional therapies.3 Thus HER2-positive status is obviously an indicator of particularly aggressive disease.

Fortunately this particular biomarker is one for which we have established and developing therapeutics. The humanized monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, has been highly effective in improving survival for HER2-positive breast cancer.6 More recently, it was studied in a phase 2 trial with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent HER2-positive UPSC.5 This trial showed that the addition of this targeted therapy to conventional chemotherapy improved recurrence-free survival from 8 months to 12 months, and improved overall survival from 24.4 months to 29.6 months.5

One discovery leads to another treatment

This discovery led to the approval of trastuzumab to be used in addition to chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent disease.2 The most significant effects appear to be among those who have not received prior therapies, with a doubling of progression-free survival among these patients, and a more modest response among patients treated for recurrent, mostly pretreated disease.

Work currently is underway to explore an array of antibody or small-molecule blockades of HER2 in addition to vaccines against the protein or treatment with conjugate compounds in which an antibody to HER2 is paired with a cytotoxic drug able to be internalized into HER2-expressing cells.7 This represents a form of personalized medicine referred to as biomarker-driven targeted therapy, in which therapies are prescribed based on the expression of specific molecular markers (such as HER2 expression) typically in combination with other clinical markers such as surgical staging results, race, age, etc. These approaches can be very effective strategies in rare tumor subtypes with distinct molecular and clinical behaviors.

As previously mentioned, the targeting of HER2 overexpression with trastuzumab has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancers where even patients with early-stage disease receive a multimodal therapy approach including antibody, chemotherapy, surgical, and often radiation treatments.6 We are moving towards a similar multimodal comprehensive treatment strategy for UPSC. If it is as successful as it is in breast cancer, it will be long overdue, and desperately necessary given the poor prognosis of this disease for all stages because of the inadequacies of current treatments strategies.

Routine testing of UPSC for HER2 expression is now a part of routine molecular substaging of uterine cancers in the same way we have embraced testing for microsatellite instability and hormone-receptor status. While a diagnosis of HER2 overexpression in UPSC portends a poor prognosis, patients can be reassured that treatment strategies exist that can target this malignant mechanism in advanced disease and more are under further development for early-stage disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328334d8a3.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Uterine Neoplasms (version 2.2020).

3. Cancer 2005 Oct 1. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21308.

4. Gynecol Oncol 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.07.016.

5. J Clin Oncol 2018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5966.

6. N Engl J Med 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383.

7. Discov Med. 2016 Apr;21(116):293-303.

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is an infrequent but deadly form of endometrial cancer comprising 10% of cases but contributing 40% of deaths from the disease. Recurrence rates are high for this disease. Five-year survival is 55% for all patients and only 70% for stage I disease.1 Patterns of recurrence tend to be distant (extrapelvic and extraabdominal) as frequently as they are localized to the pelvis, and metastases and recurrences are unrelated to the extent of uterine disease (such as myometrial invasion). It is for these reasons that the recommended course of adjuvant therapy for this disease is systemic therapy (typically six doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy) with consideration for radiation to the vagina or pelvis to consolidate pelvic and vaginal control.2 This differs from early-stage high/intermediate–risk endometrioid adenocarcinomas, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has not been found to be helpful.

Because of the lower incidence of UPSC, it frequently has been studied alongside endometrioid cell types in clinical trials which explore novel adjuvant therapies. However, UPSC is biologically distinct from endometrioid endometrial cancers, which likely results in inferior clinical responses to conventional interventions. Fortunately we are beginning to better understand UPSC at a molecular level, and advancements are being made in the targeted therapies for these patients that are unique, compared with those applied to other cancer subtypes.

As discussed above, UPSC is a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer. Histologically it is characterized by a precursor lesion of endometrial glandular dysplasia progressing to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIC). Histologically it presents with a highly atypical slit-like glandular configuration, which appears similar to serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and ovary. Molecularly these tumors commonly manifest mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which are both genes associated with oncogenic potential.1 While most UPSC tumors have loss of expression in hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone, 25%-30% of cases overexpress the tyrosine kinase receptor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).3-5 This has proven to provide an exciting target for therapeutic interventions.

A target for therapeutic intervention

HER2 is a transmembrane receptor which, when activated, signals complex downstream pathways responsible for cellular proliferation, dedifferentiation, and metastasis. In a recent multi-institutional analysis of early-stage UPSC, HER2 overexpression was identified among 25% of cases.4 Approximately 30% of cases of advanced disease manifest overexpression of this biomarker.5 HER2 overexpression (HER2-positive status) is significantly associated with higher rates of recurrence and mortality, even among patients treated with conventional therapies.3 Thus HER2-positive status is obviously an indicator of particularly aggressive disease.

Fortunately this particular biomarker is one for which we have established and developing therapeutics. The humanized monoclonal antibody, trastuzumab, has been highly effective in improving survival for HER2-positive breast cancer.6 More recently, it was studied in a phase 2 trial with carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent HER2-positive UPSC.5 This trial showed that the addition of this targeted therapy to conventional chemotherapy improved recurrence-free survival from 8 months to 12 months, and improved overall survival from 24.4 months to 29.6 months.5

One discovery leads to another treatment

This discovery led to the approval of trastuzumab to be used in addition to chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent disease.2 The most significant effects appear to be among those who have not received prior therapies, with a doubling of progression-free survival among these patients, and a more modest response among patients treated for recurrent, mostly pretreated disease.

Work currently is underway to explore an array of antibody or small-molecule blockades of HER2 in addition to vaccines against the protein or treatment with conjugate compounds in which an antibody to HER2 is paired with a cytotoxic drug able to be internalized into HER2-expressing cells.7 This represents a form of personalized medicine referred to as biomarker-driven targeted therapy, in which therapies are prescribed based on the expression of specific molecular markers (such as HER2 expression) typically in combination with other clinical markers such as surgical staging results, race, age, etc. These approaches can be very effective strategies in rare tumor subtypes with distinct molecular and clinical behaviors.

As previously mentioned, the targeting of HER2 overexpression with trastuzumab has been shown to be highly effective in the treatment of HER2-positive breast cancers where even patients with early-stage disease receive a multimodal therapy approach including antibody, chemotherapy, surgical, and often radiation treatments.6 We are moving towards a similar multimodal comprehensive treatment strategy for UPSC. If it is as successful as it is in breast cancer, it will be long overdue, and desperately necessary given the poor prognosis of this disease for all stages because of the inadequacies of current treatments strategies.

Routine testing of UPSC for HER2 expression is now a part of routine molecular substaging of uterine cancers in the same way we have embraced testing for microsatellite instability and hormone-receptor status. While a diagnosis of HER2 overexpression in UPSC portends a poor prognosis, patients can be reassured that treatment strategies exist that can target this malignant mechanism in advanced disease and more are under further development for early-stage disease.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She has no relevant financial disclosures. Email her at obnews@mdedge.com.

References

1. Curr Opin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Feb. doi: 10.1097/GCO.0b013e328334d8a3.

2. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Uterine Neoplasms (version 2.2020).

3. Cancer 2005 Oct 1. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21308.

4. Gynecol Oncol 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2020.07.016.

5. J Clin Oncol 2018. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.5966.

6. N Engl J Med 2011. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0910383.

7. Discov Med. 2016 Apr;21(116):293-303.

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma (UPSC) is an infrequent but deadly form of endometrial cancer comprising 10% of cases but contributing 40% of deaths from the disease. Recurrence rates are high for this disease. Five-year survival is 55% for all patients and only 70% for stage I disease.1 Patterns of recurrence tend to be distant (extrapelvic and extraabdominal) as frequently as they are localized to the pelvis, and metastases and recurrences are unrelated to the extent of uterine disease (such as myometrial invasion). It is for these reasons that the recommended course of adjuvant therapy for this disease is systemic therapy (typically six doses of carboplatin and paclitaxel chemotherapy) with consideration for radiation to the vagina or pelvis to consolidate pelvic and vaginal control.2 This differs from early-stage high/intermediate–risk endometrioid adenocarcinomas, for which adjuvant chemotherapy has not been found to be helpful.

Because of the lower incidence of UPSC, it frequently has been studied alongside endometrioid cell types in clinical trials which explore novel adjuvant therapies. However, UPSC is biologically distinct from endometrioid endometrial cancers, which likely results in inferior clinical responses to conventional interventions. Fortunately we are beginning to better understand UPSC at a molecular level, and advancements are being made in the targeted therapies for these patients that are unique, compared with those applied to other cancer subtypes.

As discussed above, UPSC is a particularly aggressive form of uterine cancer. Histologically it is characterized by a precursor lesion of endometrial glandular dysplasia progressing to endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIC). Histologically it presents with a highly atypical slit-like glandular configuration, which appears similar to serous carcinomas of the fallopian tube and ovary. Molecularly these tumors commonly manifest mutations in tumor protein p53 (TP53) and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase catalytic subunit alpha (PIK3CA), which are both genes associated with oncogenic potential.1 While most UPSC tumors have loss of expression in hormone receptors such as estrogen and progesterone, 25%-30% of cases overexpress the tyrosine kinase receptor human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2).3-5 This has proven to provide an exciting target for therapeutic interventions.

A target for therapeutic intervention