User login

COVID-19: A primary care perspective

With the COVID-19 pandemic, we are experiencing a once-in-a-100-year event. Dr. Steven A. Schulz, who is serving children on the front line in upstate New York, and I outline some of the challenges primary care pediatricians have been facing and solutions that have succeeded.

Reduction in direct patient care and its consequences

Because of the unknowns of COVID-19, many parents have not wanted to bring their children to a medical office because of fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2. At the same time, pediatricians have restricted in-person visits to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 and to help flatten the curve of infection. Use of pediatric medical professional services, compared with last year, dropped by 52% in March 2020 and by 58% in April, according to FAIR Health, a nonprofit organization that manages a database of 31 million claims. This is resulting in decreased immunization rates, which increases concern for secondary spikes of other preventable illnesses; for example, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that, from mid-March to mid-April 2020, physicians in the Vaccines for Children program ordered 2.5 million fewer doses of vaccines and 250,000 fewer doses of measles-containing vaccines, compared with the same period in 2019. Fewer children are being seen for well visits, which means opportunities are lost for adequate monitoring of growth, development, physical wellness, and social determinants of health.

This is occurring at a time when families have been experiencing increased stress in terms of finances, social isolation, finding adequate child care, and serving as parent, teacher, and breadwinner. An increase in injuries is occurring because of inadequate parental supervision because many parents have been distracted while working from home. An increase in cases of severe abuse is occurring because schools, child care providers, physicians, and other mandated reporters in the community have decreased interaction with children. Children’s Hospital Colorado in Colorado Springs saw a 118% increase in the number of trauma cases in its ED between January and April 2020. Some of these were accidental injuries caused by falls or bicycle accidents, but there was a 200% increase in nonaccidental trauma, which was associated with a steep fall in calls to the state’s child abuse hotline. Academic gains are being lost, and there has been worry for a prolonged “summer slide” risk, especially for children living in poverty and children with developmental disabilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic also is affecting physicians and staff. As frontline personnel, we are at risk to contract the virus, and news media reminds us of severe illness and deaths among health care workers. The pandemic is affecting financial viability; estimated revenue of pediatric offices fell by 45% in March 2020 and 48% in April, compared with the previous year, according to FAIR Health. Nurses and staff have been furloughed. Practices have had to apply for grants and Paycheck Protection Program funds while extending credit lines.

Limited testing capability for SARS-CoV-2

Testing for SARS-CoV-2 has been variably available. There have been problems with false positive and especially false negative results (BMJ. 2020 May 12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1808).The best specimen collection method has yet to be determined. Blood testing for antibody has been touted, but it remains unclear if there is clinical benefit because a positive result offers no guarantee of immunity, and immunity may quickly wane. Perhaps widespread primary care office–based testing will be in place by the fall, with hope for future reliable point of care results.

Evolving knowledge regarding SARS-CoV-2 and MIS-C

It initially was thought that children were relatively spared from serious illness caused by COVID-19. Then reports of cases of newly identified multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children occurred. It has been unclear how children contribute to the spread of COVID-19 illness, although emerging evidence indicates it is lower than adult transmission. What will happen when children return to school and daycare in the fall?

The challenges have led to creative solutions for how to deliver care.

Adapting to telehealth to provide care

At least for the short term, HIPAA regulations have been relaxed to allow for video visits using platforms such as FaceTime, Skype, Zoom, Doximity, and Doxy.me. Some of these platforms are HIPAA compliant and will be long-term solutions; however, electronic medical record portals allowing for video visits are the more secure option, according to HIPAA.

It has been a learning experience to see what can be accomplished with a video visit. Taking a history and visual examination of injuries and rashes has been possible. Addressing mental health concerns through the video exchange generally has been effective.

However, video visits change the provider-patient interpersonal dynamic and offer only visual exam capabilities, compared with an in-person visit. We cannot look in ears, palpate a liver and spleen, touch and examine a joint or bone, or feel a rash. Video visits also are dependent on the quality of patient Internet access, sufficient data plans, and mutual capabilities to address the inevitable technological glitches on the provider’s end as well. Expanding information technology infrastructure ability and added licensure costs have occurred. Practices and health systems have been working with insurance companies to ensure telephone and video visits are reimbursed on a comparable level to in-office visits.

A new type of office visit and developing appropriate safety plans

Patients must be universally screened prior to arrival during appointment scheduling for well and illness visits. Patients aged older than 2 years and caregivers must wear masks on entering the facility. In many practices, patients are scheduled during specific sick or well visit time slots throughout the day. Waiting rooms chairs need to be spaced for 6-foot social distancing, and cars in the parking lot often serve as waiting rooms until staff can meet patients at the door and take them to the exam room. Alternate entrances, car-side exams, and drive-by and/or tent testing facilities often have become part of the new normal everyday practice. Creating virtual visit time blocks in provider’s schedules has allowed for decreased office congestion. Patients often are checked out from their room, as opposed to waiting in a line at a check out desk. Nurse triage protocols also have been adapted and enhanced to meet needs and concerns.

With the need for summer physicals and many regions opening up, a gradual return toward baseline has been evolving, although some of the twists of a “new normal” will stay in place. The new normal has been for providers and staff to wear surgical masks and face shields; sometimes N95 masks, gloves, and gowns have been needed. Cleaning rooms and equipment between patient visits has become a major, new time-consuming task. Acquiring and maintaining adequate supplies has been a challenge.

Summary

The American Academy of Pediatrics, CDC, and state and local health departments have been providing informative and regular updates, webinars, and best practices guidelines. Pediatricians, community organizations, schools, and mental health professionals have been collaborating, overcoming hurdles, and working together to help mitigate the effects of the pandemic on children, their families, and our communities. Continued education, cooperation, and adaptation will be needed in the months ahead. If there is a silver lining to this pandemic experience, it may be that families have grown closer together as they sheltered in place (and we have grown closer to our own families as well). One day perhaps a child who lived through this pandemic might be asked what it was like, and their recollection might be that it was a wonderful time because their parents stayed home all the time, took care of them, taught them their school work, and took lots of long family walks.

Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director, Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz and Dr. Pichichero said they have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This article was updated 7/16/2020.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, we are experiencing a once-in-a-100-year event. Dr. Steven A. Schulz, who is serving children on the front line in upstate New York, and I outline some of the challenges primary care pediatricians have been facing and solutions that have succeeded.

Reduction in direct patient care and its consequences

Because of the unknowns of COVID-19, many parents have not wanted to bring their children to a medical office because of fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2. At the same time, pediatricians have restricted in-person visits to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 and to help flatten the curve of infection. Use of pediatric medical professional services, compared with last year, dropped by 52% in March 2020 and by 58% in April, according to FAIR Health, a nonprofit organization that manages a database of 31 million claims. This is resulting in decreased immunization rates, which increases concern for secondary spikes of other preventable illnesses; for example, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that, from mid-March to mid-April 2020, physicians in the Vaccines for Children program ordered 2.5 million fewer doses of vaccines and 250,000 fewer doses of measles-containing vaccines, compared with the same period in 2019. Fewer children are being seen for well visits, which means opportunities are lost for adequate monitoring of growth, development, physical wellness, and social determinants of health.

This is occurring at a time when families have been experiencing increased stress in terms of finances, social isolation, finding adequate child care, and serving as parent, teacher, and breadwinner. An increase in injuries is occurring because of inadequate parental supervision because many parents have been distracted while working from home. An increase in cases of severe abuse is occurring because schools, child care providers, physicians, and other mandated reporters in the community have decreased interaction with children. Children’s Hospital Colorado in Colorado Springs saw a 118% increase in the number of trauma cases in its ED between January and April 2020. Some of these were accidental injuries caused by falls or bicycle accidents, but there was a 200% increase in nonaccidental trauma, which was associated with a steep fall in calls to the state’s child abuse hotline. Academic gains are being lost, and there has been worry for a prolonged “summer slide” risk, especially for children living in poverty and children with developmental disabilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic also is affecting physicians and staff. As frontline personnel, we are at risk to contract the virus, and news media reminds us of severe illness and deaths among health care workers. The pandemic is affecting financial viability; estimated revenue of pediatric offices fell by 45% in March 2020 and 48% in April, compared with the previous year, according to FAIR Health. Nurses and staff have been furloughed. Practices have had to apply for grants and Paycheck Protection Program funds while extending credit lines.

Limited testing capability for SARS-CoV-2

Testing for SARS-CoV-2 has been variably available. There have been problems with false positive and especially false negative results (BMJ. 2020 May 12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1808).The best specimen collection method has yet to be determined. Blood testing for antibody has been touted, but it remains unclear if there is clinical benefit because a positive result offers no guarantee of immunity, and immunity may quickly wane. Perhaps widespread primary care office–based testing will be in place by the fall, with hope for future reliable point of care results.

Evolving knowledge regarding SARS-CoV-2 and MIS-C

It initially was thought that children were relatively spared from serious illness caused by COVID-19. Then reports of cases of newly identified multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children occurred. It has been unclear how children contribute to the spread of COVID-19 illness, although emerging evidence indicates it is lower than adult transmission. What will happen when children return to school and daycare in the fall?

The challenges have led to creative solutions for how to deliver care.

Adapting to telehealth to provide care

At least for the short term, HIPAA regulations have been relaxed to allow for video visits using platforms such as FaceTime, Skype, Zoom, Doximity, and Doxy.me. Some of these platforms are HIPAA compliant and will be long-term solutions; however, electronic medical record portals allowing for video visits are the more secure option, according to HIPAA.

It has been a learning experience to see what can be accomplished with a video visit. Taking a history and visual examination of injuries and rashes has been possible. Addressing mental health concerns through the video exchange generally has been effective.

However, video visits change the provider-patient interpersonal dynamic and offer only visual exam capabilities, compared with an in-person visit. We cannot look in ears, palpate a liver and spleen, touch and examine a joint or bone, or feel a rash. Video visits also are dependent on the quality of patient Internet access, sufficient data plans, and mutual capabilities to address the inevitable technological glitches on the provider’s end as well. Expanding information technology infrastructure ability and added licensure costs have occurred. Practices and health systems have been working with insurance companies to ensure telephone and video visits are reimbursed on a comparable level to in-office visits.

A new type of office visit and developing appropriate safety plans

Patients must be universally screened prior to arrival during appointment scheduling for well and illness visits. Patients aged older than 2 years and caregivers must wear masks on entering the facility. In many practices, patients are scheduled during specific sick or well visit time slots throughout the day. Waiting rooms chairs need to be spaced for 6-foot social distancing, and cars in the parking lot often serve as waiting rooms until staff can meet patients at the door and take them to the exam room. Alternate entrances, car-side exams, and drive-by and/or tent testing facilities often have become part of the new normal everyday practice. Creating virtual visit time blocks in provider’s schedules has allowed for decreased office congestion. Patients often are checked out from their room, as opposed to waiting in a line at a check out desk. Nurse triage protocols also have been adapted and enhanced to meet needs and concerns.

With the need for summer physicals and many regions opening up, a gradual return toward baseline has been evolving, although some of the twists of a “new normal” will stay in place. The new normal has been for providers and staff to wear surgical masks and face shields; sometimes N95 masks, gloves, and gowns have been needed. Cleaning rooms and equipment between patient visits has become a major, new time-consuming task. Acquiring and maintaining adequate supplies has been a challenge.

Summary

The American Academy of Pediatrics, CDC, and state and local health departments have been providing informative and regular updates, webinars, and best practices guidelines. Pediatricians, community organizations, schools, and mental health professionals have been collaborating, overcoming hurdles, and working together to help mitigate the effects of the pandemic on children, their families, and our communities. Continued education, cooperation, and adaptation will be needed in the months ahead. If there is a silver lining to this pandemic experience, it may be that families have grown closer together as they sheltered in place (and we have grown closer to our own families as well). One day perhaps a child who lived through this pandemic might be asked what it was like, and their recollection might be that it was a wonderful time because their parents stayed home all the time, took care of them, taught them their school work, and took lots of long family walks.

Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director, Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz and Dr. Pichichero said they have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This article was updated 7/16/2020.

With the COVID-19 pandemic, we are experiencing a once-in-a-100-year event. Dr. Steven A. Schulz, who is serving children on the front line in upstate New York, and I outline some of the challenges primary care pediatricians have been facing and solutions that have succeeded.

Reduction in direct patient care and its consequences

Because of the unknowns of COVID-19, many parents have not wanted to bring their children to a medical office because of fear of contracting SARS-CoV-2. At the same time, pediatricians have restricted in-person visits to prevent spread of SARS-CoV-2 and to help flatten the curve of infection. Use of pediatric medical professional services, compared with last year, dropped by 52% in March 2020 and by 58% in April, according to FAIR Health, a nonprofit organization that manages a database of 31 million claims. This is resulting in decreased immunization rates, which increases concern for secondary spikes of other preventable illnesses; for example, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention showed that, from mid-March to mid-April 2020, physicians in the Vaccines for Children program ordered 2.5 million fewer doses of vaccines and 250,000 fewer doses of measles-containing vaccines, compared with the same period in 2019. Fewer children are being seen for well visits, which means opportunities are lost for adequate monitoring of growth, development, physical wellness, and social determinants of health.

This is occurring at a time when families have been experiencing increased stress in terms of finances, social isolation, finding adequate child care, and serving as parent, teacher, and breadwinner. An increase in injuries is occurring because of inadequate parental supervision because many parents have been distracted while working from home. An increase in cases of severe abuse is occurring because schools, child care providers, physicians, and other mandated reporters in the community have decreased interaction with children. Children’s Hospital Colorado in Colorado Springs saw a 118% increase in the number of trauma cases in its ED between January and April 2020. Some of these were accidental injuries caused by falls or bicycle accidents, but there was a 200% increase in nonaccidental trauma, which was associated with a steep fall in calls to the state’s child abuse hotline. Academic gains are being lost, and there has been worry for a prolonged “summer slide” risk, especially for children living in poverty and children with developmental disabilities.

The COVID-19 pandemic also is affecting physicians and staff. As frontline personnel, we are at risk to contract the virus, and news media reminds us of severe illness and deaths among health care workers. The pandemic is affecting financial viability; estimated revenue of pediatric offices fell by 45% in March 2020 and 48% in April, compared with the previous year, according to FAIR Health. Nurses and staff have been furloughed. Practices have had to apply for grants and Paycheck Protection Program funds while extending credit lines.

Limited testing capability for SARS-CoV-2

Testing for SARS-CoV-2 has been variably available. There have been problems with false positive and especially false negative results (BMJ. 2020 May 12. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1808).The best specimen collection method has yet to be determined. Blood testing for antibody has been touted, but it remains unclear if there is clinical benefit because a positive result offers no guarantee of immunity, and immunity may quickly wane. Perhaps widespread primary care office–based testing will be in place by the fall, with hope for future reliable point of care results.

Evolving knowledge regarding SARS-CoV-2 and MIS-C

It initially was thought that children were relatively spared from serious illness caused by COVID-19. Then reports of cases of newly identified multisystem inflammatory syndrome of children occurred. It has been unclear how children contribute to the spread of COVID-19 illness, although emerging evidence indicates it is lower than adult transmission. What will happen when children return to school and daycare in the fall?

The challenges have led to creative solutions for how to deliver care.

Adapting to telehealth to provide care

At least for the short term, HIPAA regulations have been relaxed to allow for video visits using platforms such as FaceTime, Skype, Zoom, Doximity, and Doxy.me. Some of these platforms are HIPAA compliant and will be long-term solutions; however, electronic medical record portals allowing for video visits are the more secure option, according to HIPAA.

It has been a learning experience to see what can be accomplished with a video visit. Taking a history and visual examination of injuries and rashes has been possible. Addressing mental health concerns through the video exchange generally has been effective.

However, video visits change the provider-patient interpersonal dynamic and offer only visual exam capabilities, compared with an in-person visit. We cannot look in ears, palpate a liver and spleen, touch and examine a joint or bone, or feel a rash. Video visits also are dependent on the quality of patient Internet access, sufficient data plans, and mutual capabilities to address the inevitable technological glitches on the provider’s end as well. Expanding information technology infrastructure ability and added licensure costs have occurred. Practices and health systems have been working with insurance companies to ensure telephone and video visits are reimbursed on a comparable level to in-office visits.

A new type of office visit and developing appropriate safety plans

Patients must be universally screened prior to arrival during appointment scheduling for well and illness visits. Patients aged older than 2 years and caregivers must wear masks on entering the facility. In many practices, patients are scheduled during specific sick or well visit time slots throughout the day. Waiting rooms chairs need to be spaced for 6-foot social distancing, and cars in the parking lot often serve as waiting rooms until staff can meet patients at the door and take them to the exam room. Alternate entrances, car-side exams, and drive-by and/or tent testing facilities often have become part of the new normal everyday practice. Creating virtual visit time blocks in provider’s schedules has allowed for decreased office congestion. Patients often are checked out from their room, as opposed to waiting in a line at a check out desk. Nurse triage protocols also have been adapted and enhanced to meet needs and concerns.

With the need for summer physicals and many regions opening up, a gradual return toward baseline has been evolving, although some of the twists of a “new normal” will stay in place. The new normal has been for providers and staff to wear surgical masks and face shields; sometimes N95 masks, gloves, and gowns have been needed. Cleaning rooms and equipment between patient visits has become a major, new time-consuming task. Acquiring and maintaining adequate supplies has been a challenge.

Summary

The American Academy of Pediatrics, CDC, and state and local health departments have been providing informative and regular updates, webinars, and best practices guidelines. Pediatricians, community organizations, schools, and mental health professionals have been collaborating, overcoming hurdles, and working together to help mitigate the effects of the pandemic on children, their families, and our communities. Continued education, cooperation, and adaptation will be needed in the months ahead. If there is a silver lining to this pandemic experience, it may be that families have grown closer together as they sheltered in place (and we have grown closer to our own families as well). One day perhaps a child who lived through this pandemic might be asked what it was like, and their recollection might be that it was a wonderful time because their parents stayed home all the time, took care of them, taught them their school work, and took lots of long family walks.

Dr. Schulz is pediatric medical director, Rochester (N.Y.) Regional Health. Dr. Pichichero is a specialist in pediatric infectious diseases and director of the Research Institute at Rochester (N.Y.) General Hospital. Dr. Schulz and Dr. Pichichero said they have no relevant financial disclosures. Email them at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This article was updated 7/16/2020.

Creating a student-staffed family call line to alleviate clinical burden

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

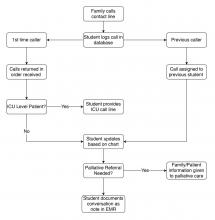

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

The coronavirus pandemic has fundamentally altered American health care. At our academic medical center in Brooklyn, a large safety net institution, clinical year medical students are normally integral members of the team consistent with the model of “value-added medical education.”1 With the suspension of clinical rotations on March 13, 2020, a key part of the workforce was suddenly withdrawn while demand skyrocketed.

In response, students self-organized into numerous remote support projects, including the project described below.

Under infection control regulations, a “no-visitor” policy was instituted. Concurrently, the dramatic increase in patient volume left clinicians unable to regularly update patients’ families. To address this gap, a family contact line was created.

A dedicated phone number was distributed to key hospital personnel to share with families seeking information. The work flow for returning calls is shown in the figure. After verifying patient information and the caller’s relation, students provide updates based on chart review. Calls are prefaced with the disclaimer that students are not part of the treatment team and can only give information that is accessible via the electronic medical record.

Students created a phone script in conjunction with faculty, as well as a referral system for those seeking specific information from other departments. This script undergoes daily revision after the student huddle to address new issues. Flow of information is bidirectional: students relay patient updates as well as quarantine precautions and obtain past medical history. This proved essential during the surge of patients, unknown to the hospital and frequently altered, arriving by ambulance. Students document these conversations in the EMR, including family concerns and whether immediate provider follow-up is needed.

Two key limitations were quickly addressed: First, patients requiring ICU-level care have fluctuating courses, and an update based solely on chart review is insufficient. In response, students worked with intensivist teams to create a dedicated call line staffed by providers.

Second, conversations regarding goals of care and end of life concerns were beyond students’ scope. Together with palliative care teams, students developed criteria for flagging families for follow-up by a consulting palliative care attending.

Through working the call line, students received a crash course in empathetically communicating over the phone. Particularly during the worst of the surge, families were afraid and often frustrated at the lack of communication up to that point. Navigating these emotions, learning how to update family members while removed from the teams, and educating callers on quarantine precautions and other concerns was a valuable learning experience.

As students, we have been exposed to many of the realities of communicating as a physician. Relaying updates and prognosis to family while also providing emotional support is not something we are taught in medical school, but is something we will be expected to handle our first night on the wards as an intern. This experience has prepared us well for that and has illuminated missing parts of the medical school curriculum we are working on emphasizing moving forward.

Over the first 2 weeks, students put in 848 volunteer-hours, making 1,438 calls which reached 1,114 different families. We hope our experience proves instructive for other academic medical centers facing similar concerns in coming months. This model allows medical students to be directly involved in patient care during this crisis and shifts these time-intensive conversations away from overwhelmed primary medical teams.

Reference

1. Gonzalo JD et al. Value-added clinical systems learning roles for 355 medical students that transform education and health: A guide for building partnerships between 356 medical schools and health systems. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):602-7.

Ms. Jaiman is an MD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn and a PhD candidate at the National Center of Biological Sciences in Bangalore, India. Mr. Hessburg is an MD/PhD candidate at State University of New York, Brooklyn. Dr. Egelko is a recent graduate of State University of New York, Brooklyn.

The public’s trust in science

Having been a bench research scientist 30 years ago, I am flabbergasted at what is and is not currently possible. In a few weeks, scientists sequenced a novel coronavirus and used the genetic sequence to select candidate molecules for a vaccine. But we still can’t reliably say how much protection a cloth mask provides. Worse yet, even if/when we could reliably quantify contagion, it isn’t clear that the public will believe us anyhow.

The good news is that the public worldwide did believe scientists about the threat of a pandemic and the need to flatten the curve. Saving lives has not been about the strength of an antibiotic or the skill in managing a ventilator, but the credibility of medical scientists. The degree of acceptance was variable and subject to a variety of delays caused by regional politicians, but The bad news is that the public’s trust in that scientific advice has waned, the willingness to accept onerous restrictions has fatigued, and the cooperation for maintaining these social changes is evaporating.

I will leave pontificating about the spread of COVID-19 to other experts in other forums. My focus is on the public’s trust in the professionalism of physicians, nurses, medical scientists, and the health care industry as a whole. That trust has been our most valuable tool in fighting the pandemic so far. There have been situations in which weaknesses in modern science have let society down during the pandemic of the century. In my February 2020 column, at the beginning of the outbreak, a month before it was declared a pandemic, when its magnitude was still unclear, I emphasized the importance of having a trusted scientific spokesperson providing timely, accurate information to the public. That, obviously, did not happen in the United States and the degree of the ensuing disaster is still to be revealed.

Scientists have made some wrong decisions about this novel threat. The advice on masks is an illustrative example. For many years, infection control nurses have insisted that medical students wear a mask to protect themselves, even if they were observing rounds from just inside the doorway of a room of a baby with bronchiolitis. The landfills are full of briefly worn surgical masks. Now the story goes: Surgical masks don’t protect staff; they protect others. Changes like that contribute to a credibility gap.

For 3 months, there was conflicting advice about the appropriateness of masks. In early March 2020, some health care workers were disciplined for wearing personal masks. Now, most scientists recommend the public use masks to reduce contagion. Significant subgroups in the U.S. population have refused, mostly to signal their contrarian politics. In June there was an anecdote of a success story from the Show Me state of Missouri, where a mask is credited for preventing an outbreak from a sick hair stylist.

It is hard to find something more reliable than an anecdote. On June 1, a meta-analysis funded by the World Health Organization was published online by Lancet. It supports the idea that masks are beneficial. It is mostly forest plots, so you can try to interpret it yourself. There were 172 observational studies in the systematic review, and the meta-analysis contains 44 relevant comparative studies and 0 randomized controlled trials. Most of those forest plots have an I2 of 75% or worse, which to me indicates that they are not much more reliable than a good anecdote. My primary conclusion was that modern academic science, in an era with a shortage of toilet paper, should convert to printing on soft tissue paper.

It is important to note that the guesstimated overall benefit of cloth masks was a relative risk of 0.30. That benefit is easily nullified if the false security of a mask causes people to congregate together in groups three times larger or for three times more minutes. N95 masks were more effective.

A different article was published in PNAS on June 11. Its senior author was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995. That article touted the benefits of masks. The article is facing heavy criticism for flaws in methodology and flaws in the peer review process. A long list of signatories have joined a letter asking for the article’s retraction.

This article, when combined with the two instances of prominent articles being retracted in the prior month by the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet, is accumulating evidence the peer review system is not working as intended.

There are many heroes in this pandemic, from the frontline health care workers in hotspots to the grocery workers and cleaning staff. There is hope, indeed some faith, that medical scientists in the foreseeable future will provide treatments and a vaccine for this viral plague. This month, the credibility of scientists again plays a major role as communities respond to outbreaks related to reopening the economy. Let’s celebrate the victories, resolve to fix the impure system, and restore a high level of public trust in science. Lives depend on it.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Having been a bench research scientist 30 years ago, I am flabbergasted at what is and is not currently possible. In a few weeks, scientists sequenced a novel coronavirus and used the genetic sequence to select candidate molecules for a vaccine. But we still can’t reliably say how much protection a cloth mask provides. Worse yet, even if/when we could reliably quantify contagion, it isn’t clear that the public will believe us anyhow.

The good news is that the public worldwide did believe scientists about the threat of a pandemic and the need to flatten the curve. Saving lives has not been about the strength of an antibiotic or the skill in managing a ventilator, but the credibility of medical scientists. The degree of acceptance was variable and subject to a variety of delays caused by regional politicians, but The bad news is that the public’s trust in that scientific advice has waned, the willingness to accept onerous restrictions has fatigued, and the cooperation for maintaining these social changes is evaporating.

I will leave pontificating about the spread of COVID-19 to other experts in other forums. My focus is on the public’s trust in the professionalism of physicians, nurses, medical scientists, and the health care industry as a whole. That trust has been our most valuable tool in fighting the pandemic so far. There have been situations in which weaknesses in modern science have let society down during the pandemic of the century. In my February 2020 column, at the beginning of the outbreak, a month before it was declared a pandemic, when its magnitude was still unclear, I emphasized the importance of having a trusted scientific spokesperson providing timely, accurate information to the public. That, obviously, did not happen in the United States and the degree of the ensuing disaster is still to be revealed.

Scientists have made some wrong decisions about this novel threat. The advice on masks is an illustrative example. For many years, infection control nurses have insisted that medical students wear a mask to protect themselves, even if they were observing rounds from just inside the doorway of a room of a baby with bronchiolitis. The landfills are full of briefly worn surgical masks. Now the story goes: Surgical masks don’t protect staff; they protect others. Changes like that contribute to a credibility gap.

For 3 months, there was conflicting advice about the appropriateness of masks. In early March 2020, some health care workers were disciplined for wearing personal masks. Now, most scientists recommend the public use masks to reduce contagion. Significant subgroups in the U.S. population have refused, mostly to signal their contrarian politics. In June there was an anecdote of a success story from the Show Me state of Missouri, where a mask is credited for preventing an outbreak from a sick hair stylist.

It is hard to find something more reliable than an anecdote. On June 1, a meta-analysis funded by the World Health Organization was published online by Lancet. It supports the idea that masks are beneficial. It is mostly forest plots, so you can try to interpret it yourself. There were 172 observational studies in the systematic review, and the meta-analysis contains 44 relevant comparative studies and 0 randomized controlled trials. Most of those forest plots have an I2 of 75% or worse, which to me indicates that they are not much more reliable than a good anecdote. My primary conclusion was that modern academic science, in an era with a shortage of toilet paper, should convert to printing on soft tissue paper.

It is important to note that the guesstimated overall benefit of cloth masks was a relative risk of 0.30. That benefit is easily nullified if the false security of a mask causes people to congregate together in groups three times larger or for three times more minutes. N95 masks were more effective.

A different article was published in PNAS on June 11. Its senior author was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995. That article touted the benefits of masks. The article is facing heavy criticism for flaws in methodology and flaws in the peer review process. A long list of signatories have joined a letter asking for the article’s retraction.

This article, when combined with the two instances of prominent articles being retracted in the prior month by the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet, is accumulating evidence the peer review system is not working as intended.

There are many heroes in this pandemic, from the frontline health care workers in hotspots to the grocery workers and cleaning staff. There is hope, indeed some faith, that medical scientists in the foreseeable future will provide treatments and a vaccine for this viral plague. This month, the credibility of scientists again plays a major role as communities respond to outbreaks related to reopening the economy. Let’s celebrate the victories, resolve to fix the impure system, and restore a high level of public trust in science. Lives depend on it.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Having been a bench research scientist 30 years ago, I am flabbergasted at what is and is not currently possible. In a few weeks, scientists sequenced a novel coronavirus and used the genetic sequence to select candidate molecules for a vaccine. But we still can’t reliably say how much protection a cloth mask provides. Worse yet, even if/when we could reliably quantify contagion, it isn’t clear that the public will believe us anyhow.

The good news is that the public worldwide did believe scientists about the threat of a pandemic and the need to flatten the curve. Saving lives has not been about the strength of an antibiotic or the skill in managing a ventilator, but the credibility of medical scientists. The degree of acceptance was variable and subject to a variety of delays caused by regional politicians, but The bad news is that the public’s trust in that scientific advice has waned, the willingness to accept onerous restrictions has fatigued, and the cooperation for maintaining these social changes is evaporating.

I will leave pontificating about the spread of COVID-19 to other experts in other forums. My focus is on the public’s trust in the professionalism of physicians, nurses, medical scientists, and the health care industry as a whole. That trust has been our most valuable tool in fighting the pandemic so far. There have been situations in which weaknesses in modern science have let society down during the pandemic of the century. In my February 2020 column, at the beginning of the outbreak, a month before it was declared a pandemic, when its magnitude was still unclear, I emphasized the importance of having a trusted scientific spokesperson providing timely, accurate information to the public. That, obviously, did not happen in the United States and the degree of the ensuing disaster is still to be revealed.

Scientists have made some wrong decisions about this novel threat. The advice on masks is an illustrative example. For many years, infection control nurses have insisted that medical students wear a mask to protect themselves, even if they were observing rounds from just inside the doorway of a room of a baby with bronchiolitis. The landfills are full of briefly worn surgical masks. Now the story goes: Surgical masks don’t protect staff; they protect others. Changes like that contribute to a credibility gap.

For 3 months, there was conflicting advice about the appropriateness of masks. In early March 2020, some health care workers were disciplined for wearing personal masks. Now, most scientists recommend the public use masks to reduce contagion. Significant subgroups in the U.S. population have refused, mostly to signal their contrarian politics. In June there was an anecdote of a success story from the Show Me state of Missouri, where a mask is credited for preventing an outbreak from a sick hair stylist.

It is hard to find something more reliable than an anecdote. On June 1, a meta-analysis funded by the World Health Organization was published online by Lancet. It supports the idea that masks are beneficial. It is mostly forest plots, so you can try to interpret it yourself. There were 172 observational studies in the systematic review, and the meta-analysis contains 44 relevant comparative studies and 0 randomized controlled trials. Most of those forest plots have an I2 of 75% or worse, which to me indicates that they are not much more reliable than a good anecdote. My primary conclusion was that modern academic science, in an era with a shortage of toilet paper, should convert to printing on soft tissue paper.

It is important to note that the guesstimated overall benefit of cloth masks was a relative risk of 0.30. That benefit is easily nullified if the false security of a mask causes people to congregate together in groups three times larger or for three times more minutes. N95 masks were more effective.

A different article was published in PNAS on June 11. Its senior author was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1995. That article touted the benefits of masks. The article is facing heavy criticism for flaws in methodology and flaws in the peer review process. A long list of signatories have joined a letter asking for the article’s retraction.

This article, when combined with the two instances of prominent articles being retracted in the prior month by the New England Journal of Medicine and The Lancet, is accumulating evidence the peer review system is not working as intended.

There are many heroes in this pandemic, from the frontline health care workers in hotspots to the grocery workers and cleaning staff. There is hope, indeed some faith, that medical scientists in the foreseeable future will provide treatments and a vaccine for this viral plague. This month, the credibility of scientists again plays a major role as communities respond to outbreaks related to reopening the economy. Let’s celebrate the victories, resolve to fix the impure system, and restore a high level of public trust in science. Lives depend on it.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He has no relevant financial disclosures. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

Wave, surge, or tsunami

Different COVID-19 models and predicting inpatient bed capacity

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the defining moments in history for this generation’s health care leaders. In 2019, most of us wrongly assumed that this virus would be similar to the past viral epidemics and pandemics such as 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome–CoV in Asia, 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, 2012 Middle East respiratory syndrome–CoV in Saudi Arabia, and 2014-2016 Ebola in West Africa. Moreover, we understood that the 50% fatality rate of Ebola, a single-stranded RNA virus, was deadly on the continent of Africa, but its transmission was through direct contact with blood or other bodily fluids. Hence, the infectivity of Ebola to the general public was lower than SARS-CoV-2, which is spread by respiratory droplets and contact routes in addition to being the virus that causes COVID-19.1 Many of us did not expect that SARS-CoV-2, a single-stranded RNA virus consisting of 32 kilobytes, would reach the shores of the United States from the Hubei province of China, the northern Lombardy region of Italy, or other initial hotspots. We could not imagine its effects would be so devastating from an economic and medical perspective. Until it did.

The first reported case of SARS-CoV-2 was on Jan. 20, 2020 in Snohomish County, Wash., and the first known death from COVID-19 occurred on Feb. 6, 2020 in Santa Clara County, Calif.2,3 Since then, the United States has lost over 135,000 people from COVID-19 with death(s) reported in every state and the highest number of overall deaths of any country in the world.4 At the beginning of 2020, at our institution, Wake Forest Baptist Health System in Winston-Salem, N.C., we began preparing for the wave, surge, or tsunami of inpatients that was coming. Plans were afoot to increase our staff, even perhaps by hiring out-of-state physicians and nurses if needed, and every possible bed was considered within the system. It was not an if, but rather a when, as to the arrival of COVID-19.

Epidemiologists and biostatisticians developed predictive COVID-19 models so that health care leaders could plan accordingly, especially those patients that required critical care or inpatient medical care. These predictive models have been used across the globe and can be categorized into three groups: Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered, Agent-Based, and Curve Fitting Extrapolation.5 Our original predictions were based on the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation model from Washington state (Curve Fitting Extrapolation). It creates projections from COVID-19 mortality data and assumes a 3% infection rate. Other health systems in our region used the COVID-19 Hospital Impact Model for Epidemics–University of Pennsylvania model. It pins its suppositions on hospitalized COVID-19 patients, regional infection rates, and hospital market shares. Lastly, the agent-based mode, such as the Global Epidemic and Mobility Project, takes simulated populations and forecasts the spread of SARS-CoV-2 anchoring on the interplay of individuals and groups. The assumptions are created secondary to the interactions of people, time, health care interventions, and public health policies.

Based on these predictive simulations, health systems have spent countless hours of planning and have utilized resources for the anticipated needs related to beds, ventilators, supplies, and staffing. Frontline staff were retrained how to don and doff personal protective equipment. Our teams were ready if we saw a wave of 250, a surge of 500, or a tsunami of 750 COVID-19 inpatients. We were prepared to run into the fire fully knowing the personal risks and consequences.

But, as yet, the tsunami in North Carolina has never come. On April 21, 2020, the COVID-19 mortality data in North Carolina peaked at 34 deaths, with the total number of deaths standing at 1,510 as of July 13, 2020.6 A surge did not hit our institutional shores at Wake Forest Baptist Health. As we looked through the proverbial back window and hear about the tsunami in Houston, Texas, we are very thankful that the tsunami turned out to be a small wave so far in North Carolina. We are grateful that there were fewer deaths than expected. The dust is settling now and the question, spoken or unspoken, is: “How could we be so wrong with our predictions?”

Models have strengths and weaknesses and none are perfect.7 There is an old aphorism in statistics that is often attributed to George Box that says: “All models are wrong but some are useful.”8 Predictions and projections are good, but not perfect. Our measurements and tests should not only be accurate, but also be as precise as possible.9 Moreover, the assumptions we make should be on solid ground. Since the beginning of the pandemic, there may have been undercounts and delays in reporting. The assumptions of the effects of social distancing may have been inaccurate. Just as important, the lack of early testing in our pandemic and the relatively limited testing currently available provide challenges not only in attributing past deaths to COVID-19, but also with planning and public health measures. To be fair, the tsunami that turned out to be a small wave in North Carolina may be caused by the strong leadership from politicians, public health officials, and health system leaders for their stay-at-home decree and vigorous public health measures in our state.

Some of the health systems in the United States have created “reemergence plans” to care for those patients who have stayed at home for the past several months. Elective surgeries and procedures have begun in different regions of the United States and will likely continue reopening into the late summer. Nevertheless, challenges and opportunities continue to abound during these difficult times of COVID-19. The tsunamis or surges will continue to occur in the United States and the premature reopening of some of the public places and businesses have not helped our collective efforts. In addition, the personal costs have been and will be immeasurable. Many of us have lost loved ones, been laid off, or face mental health crises because of the social isolation and false news.

COVID-19 is here to stay and will be with us for the foreseeable future. Health care providers have been literally risking their lives to serve the public and we will continue to do so. Hitting the target of needed inpatient beds and critical care beds is critically important and is tough without accurate data. We simply have inadequate and unreliable data of COVID-19 incidence and prevalence rates in the communities that we serve. More available testing would allow frontline health care providers and health care leaders to match hospital demand to supply, at individual hospitals and within the health care system. Moreover, contact tracing capabilities would give us the opportunity to isolate individuals and extinguish population-based hotspots.

We may have seen the first wave, but other waves of COVID-19 in North Carolina are sure to come. Since the partial reopening of North Carolina on May 8, 2020, coupled with pockets of nonadherence to social distancing and mask wearing, we expect a second wave sooner rather than later. Interestingly, daily new lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases in North Carolina have been on the rise, with the highest one-day total occurring on June 12, 2020 with 1,768 cases reported.6 As a result, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper and Secretary of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Dr. Mandy Cohen, placed a temporary pause on the Phase 2 reopening plan and mandated masks in public on June 24, 2020. It is unclear whether these intermittent daily spikes in lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases are a foreshadowing of our next wave, surge, or tsunami, or just an anomaly. Only time will tell, but as Jim Kim, MD, PhD, has stated so well, there is still time for social distancing, contact tracing, testing, isolation, and treatment.10 There is still time for us, for our loved ones, for our hospital systems, and for our public health system.

Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System and associate professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine. Dr. Lippert is assistant professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine. Mr. Payne is the associate vice president of Wake Forest Baptist Health. He is responsible for engineering, facilities planning & design as well as environmental health and safety departments. Dr. Pariyadath is comedical director of the Patient Flow Operations Center which facilitates patient placement throughout the Wake Forest Baptist Health system. He is also the associate medical director for the adult emergency department. Dr. Sunkara is assistant professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine. He is the medical director for hospital medicine units and the newly established PUI unit.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Julie Freischlag, MD; Kevin High, MD, MS; Gary Rosenthal, MD; Wayne Meredith, MD;Russ Howerton, MD; Mike Waid, Andrea Fernandez, MD; Brian Hiestand, MD; the Wake Forest Baptist Health System COVID-19 task force, the Operations Center, and the countless frontline staff at all five hospitals within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System.

References

1. World Health Organization. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: Implications for IPC precaution recommendations. 2020 June 30. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations.

2. Holshue et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382: 929-36.

3. Fuller T, Baker M. Coronavirus death in California came weeks before first known U.S. death. New York Times. 2020 Apr 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/us/coronavirus-first-united-states-death.html.

4. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map. Accessed 2020 May 28.

5. Michaud J et al. COVID-19 models: Can they tell us what we want to know? 2020 April 16. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-policy-watch/covid-19-models.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. Accessed 2020 June 30.

7. Jewell N et al. Caution warranted: Using the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Model for predicting the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:1-3.

8. Box G. Science and statistics. J Am Stat Assoc. 1972;71:791-9.

9. Shapiro DE. The interpretation of diagnostic tests. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:113-34.

10. Kim J. It is not too late to go on the offense against the coronavirus. The New Yorker. 2020 Apr 20. https://www.newyorker.com/science/medical-dispatch/its-not-too-late-to-go-on-offense-against-the-coronavirus.

Different COVID-19 models and predicting inpatient bed capacity

Different COVID-19 models and predicting inpatient bed capacity

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the defining moments in history for this generation’s health care leaders. In 2019, most of us wrongly assumed that this virus would be similar to the past viral epidemics and pandemics such as 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome–CoV in Asia, 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, 2012 Middle East respiratory syndrome–CoV in Saudi Arabia, and 2014-2016 Ebola in West Africa. Moreover, we understood that the 50% fatality rate of Ebola, a single-stranded RNA virus, was deadly on the continent of Africa, but its transmission was through direct contact with blood or other bodily fluids. Hence, the infectivity of Ebola to the general public was lower than SARS-CoV-2, which is spread by respiratory droplets and contact routes in addition to being the virus that causes COVID-19.1 Many of us did not expect that SARS-CoV-2, a single-stranded RNA virus consisting of 32 kilobytes, would reach the shores of the United States from the Hubei province of China, the northern Lombardy region of Italy, or other initial hotspots. We could not imagine its effects would be so devastating from an economic and medical perspective. Until it did.

The first reported case of SARS-CoV-2 was on Jan. 20, 2020 in Snohomish County, Wash., and the first known death from COVID-19 occurred on Feb. 6, 2020 in Santa Clara County, Calif.2,3 Since then, the United States has lost over 135,000 people from COVID-19 with death(s) reported in every state and the highest number of overall deaths of any country in the world.4 At the beginning of 2020, at our institution, Wake Forest Baptist Health System in Winston-Salem, N.C., we began preparing for the wave, surge, or tsunami of inpatients that was coming. Plans were afoot to increase our staff, even perhaps by hiring out-of-state physicians and nurses if needed, and every possible bed was considered within the system. It was not an if, but rather a when, as to the arrival of COVID-19.

Epidemiologists and biostatisticians developed predictive COVID-19 models so that health care leaders could plan accordingly, especially those patients that required critical care or inpatient medical care. These predictive models have been used across the globe and can be categorized into three groups: Susceptible-Exposed-Infectious-Recovered, Agent-Based, and Curve Fitting Extrapolation.5 Our original predictions were based on the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation model from Washington state (Curve Fitting Extrapolation). It creates projections from COVID-19 mortality data and assumes a 3% infection rate. Other health systems in our region used the COVID-19 Hospital Impact Model for Epidemics–University of Pennsylvania model. It pins its suppositions on hospitalized COVID-19 patients, regional infection rates, and hospital market shares. Lastly, the agent-based mode, such as the Global Epidemic and Mobility Project, takes simulated populations and forecasts the spread of SARS-CoV-2 anchoring on the interplay of individuals and groups. The assumptions are created secondary to the interactions of people, time, health care interventions, and public health policies.

Based on these predictive simulations, health systems have spent countless hours of planning and have utilized resources for the anticipated needs related to beds, ventilators, supplies, and staffing. Frontline staff were retrained how to don and doff personal protective equipment. Our teams were ready if we saw a wave of 250, a surge of 500, or a tsunami of 750 COVID-19 inpatients. We were prepared to run into the fire fully knowing the personal risks and consequences.

But, as yet, the tsunami in North Carolina has never come. On April 21, 2020, the COVID-19 mortality data in North Carolina peaked at 34 deaths, with the total number of deaths standing at 1,510 as of July 13, 2020.6 A surge did not hit our institutional shores at Wake Forest Baptist Health. As we looked through the proverbial back window and hear about the tsunami in Houston, Texas, we are very thankful that the tsunami turned out to be a small wave so far in North Carolina. We are grateful that there were fewer deaths than expected. The dust is settling now and the question, spoken or unspoken, is: “How could we be so wrong with our predictions?”

Models have strengths and weaknesses and none are perfect.7 There is an old aphorism in statistics that is often attributed to George Box that says: “All models are wrong but some are useful.”8 Predictions and projections are good, but not perfect. Our measurements and tests should not only be accurate, but also be as precise as possible.9 Moreover, the assumptions we make should be on solid ground. Since the beginning of the pandemic, there may have been undercounts and delays in reporting. The assumptions of the effects of social distancing may have been inaccurate. Just as important, the lack of early testing in our pandemic and the relatively limited testing currently available provide challenges not only in attributing past deaths to COVID-19, but also with planning and public health measures. To be fair, the tsunami that turned out to be a small wave in North Carolina may be caused by the strong leadership from politicians, public health officials, and health system leaders for their stay-at-home decree and vigorous public health measures in our state.

Some of the health systems in the United States have created “reemergence plans” to care for those patients who have stayed at home for the past several months. Elective surgeries and procedures have begun in different regions of the United States and will likely continue reopening into the late summer. Nevertheless, challenges and opportunities continue to abound during these difficult times of COVID-19. The tsunamis or surges will continue to occur in the United States and the premature reopening of some of the public places and businesses have not helped our collective efforts. In addition, the personal costs have been and will be immeasurable. Many of us have lost loved ones, been laid off, or face mental health crises because of the social isolation and false news.

COVID-19 is here to stay and will be with us for the foreseeable future. Health care providers have been literally risking their lives to serve the public and we will continue to do so. Hitting the target of needed inpatient beds and critical care beds is critically important and is tough without accurate data. We simply have inadequate and unreliable data of COVID-19 incidence and prevalence rates in the communities that we serve. More available testing would allow frontline health care providers and health care leaders to match hospital demand to supply, at individual hospitals and within the health care system. Moreover, contact tracing capabilities would give us the opportunity to isolate individuals and extinguish population-based hotspots.

We may have seen the first wave, but other waves of COVID-19 in North Carolina are sure to come. Since the partial reopening of North Carolina on May 8, 2020, coupled with pockets of nonadherence to social distancing and mask wearing, we expect a second wave sooner rather than later. Interestingly, daily new lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases in North Carolina have been on the rise, with the highest one-day total occurring on June 12, 2020 with 1,768 cases reported.6 As a result, North Carolina Gov. Roy Cooper and Secretary of the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Dr. Mandy Cohen, placed a temporary pause on the Phase 2 reopening plan and mandated masks in public on June 24, 2020. It is unclear whether these intermittent daily spikes in lab-confirmed COVID-19 cases are a foreshadowing of our next wave, surge, or tsunami, or just an anomaly. Only time will tell, but as Jim Kim, MD, PhD, has stated so well, there is still time for social distancing, contact tracing, testing, isolation, and treatment.10 There is still time for us, for our loved ones, for our hospital systems, and for our public health system.

Dr. Huang is the executive medical director and service line director of general medicine and hospital medicine within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System and associate professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine. Dr. Lippert is assistant professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine. Mr. Payne is the associate vice president of Wake Forest Baptist Health. He is responsible for engineering, facilities planning & design as well as environmental health and safety departments. Dr. Pariyadath is comedical director of the Patient Flow Operations Center which facilitates patient placement throughout the Wake Forest Baptist Health system. He is also the associate medical director for the adult emergency department. Dr. Sunkara is assistant professor of internal medicine at Wake Forest School of Medicine. He is the medical director for hospital medicine units and the newly established PUI unit.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Julie Freischlag, MD; Kevin High, MD, MS; Gary Rosenthal, MD; Wayne Meredith, MD;Russ Howerton, MD; Mike Waid, Andrea Fernandez, MD; Brian Hiestand, MD; the Wake Forest Baptist Health System COVID-19 task force, the Operations Center, and the countless frontline staff at all five hospitals within the Wake Forest Baptist Health System.

References

1. World Health Organization. Modes of transmission of virus causing COVID-19: Implications for IPC precaution recommendations. 2020 June 30. https://www.who.int/news-room/commentaries/detail/modes-of-transmission-of-virus-causing-covid-19-implications-for-ipc-precaution-recommendations.

2. Holshue et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020;382: 929-36.

3. Fuller T, Baker M. Coronavirus death in California came weeks before first known U.S. death. New York Times. 2020 Apr 22. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/22/us/coronavirus-first-united-states-death.html.

4. Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/us-map. Accessed 2020 May 28.

5. Michaud J et al. COVID-19 models: Can they tell us what we want to know? 2020 April 16. https://www.kff.org/coronavirus-policy-watch/covid-19-models.

6. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/cases-updates/cases-in-us.html. Accessed 2020 June 30.

7. Jewell N et al. Caution warranted: Using the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation Model for predicting the course of the COVID-19 pandemic. Ann Intern Med. 2020;173:1-3.

8. Box G. Science and statistics. J Am Stat Assoc. 1972;71:791-9.

9. Shapiro DE. The interpretation of diagnostic tests. Stat Methods Med Res. 1999;8:113-34.

10. Kim J. It is not too late to go on the offense against the coronavirus. The New Yorker. 2020 Apr 20. https://www.newyorker.com/science/medical-dispatch/its-not-too-late-to-go-on-offense-against-the-coronavirus.

The COVID-19 pandemic is one of the defining moments in history for this generation’s health care leaders. In 2019, most of us wrongly assumed that this virus would be similar to the past viral epidemics and pandemics such as 2002 severe acute respiratory syndrome–CoV in Asia, 2009 H1N1 influenza in the United States, 2012 Middle East respiratory syndrome–CoV in Saudi Arabia, and 2014-2016 Ebola in West Africa. Moreover, we understood that the 50% fatality rate of Ebola, a single-stranded RNA virus, was deadly on the continent of Africa, but its transmission was through direct contact with blood or other bodily fluids. Hence, the infectivity of Ebola to the general public was lower than SARS-CoV-2, which is spread by respiratory droplets and contact routes in addition to being the virus that causes COVID-19.1 Many of us did not expect that SARS-CoV-2, a single-stranded RNA virus consisting of 32 kilobytes, would reach the shores of the United States from the Hubei province of China, the northern Lombardy region of Italy, or other initial hotspots. We could not imagine its effects would be so devastating from an economic and medical perspective. Until it did.

The first reported case of SARS-CoV-2 was on Jan. 20, 2020 in Snohomish County, Wash., and the first known death from COVID-19 occurred on Feb. 6, 2020 in Santa Clara County, Calif.2,3 Since then, the United States has lost over 135,000 people from COVID-19 with death(s) reported in every state and the highest number of overall deaths of any country in the world.4 At the beginning of 2020, at our institution, Wake Forest Baptist Health System in Winston-Salem, N.C., we began preparing for the wave, surge, or tsunami of inpatients that was coming. Plans were afoot to increase our staff, even perhaps by hiring out-of-state physicians and nurses if needed, and every possible bed was considered within the system. It was not an if, but rather a when, as to the arrival of COVID-19.