User login

Addressing suicide prevention among South Asian Americans

Multifaceted strategies are needed to address unique cultural factors

On first glance, the age-adjusted rate of suicide for Asian and Pacific Islander populations living in the United States looks comparatively low.

Over the past 2 decades in the United States, for example, the overall rate increased by 35%, from, 10.5 to 14.2 per 100,000 individuals. That compares with a rate of 7.0 per 100,000 among Asian and Pacific Islander communities.1

However, because of the aggregate nature (national suicide mortality data combine people of Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander descent into a single group) in which these data are reported, a significant amount of salient information on subgroups of Asian Americans is lost.2 There is a growing body of research on the mental health of Asian Americans, but the dearth of information and research on suicide in South Asians is striking.3 In fact, a review of literature finds fewer than 10 articles on the topic that have been published in peer-reviewed journals in the last decade. to provide effective, culturally sensitive care.

Diverse group

There are 3.4 million individuals of South Asian descent in the United States. Geographically, South Asians may have familial and cultural/historical roots in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan.4 They enjoy a rich diversity in terms of cultural and religious beliefs, language, socioeconomic status, modes of acculturation, and immigration patterns. Asian Indians are the largest group of South Asians in the United States. They are highly educated, with a larger proportion of them pursuing an undergraduate and/or graduate level education than the general population. The median household income of Asian Indians is also higher than the national average.5

In general, suicide, like all mental health issues, is a stigmatized and taboo topic in the South Asian community.6 Also, South Asian Americans are hesitant to seek mental health care because of a perceived inability of Western health care professionals to understand their cultural views. Extrapolation from data on South Asians in the United Kingdom, aggregate statistics for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and studies on South Asians in the United States highlight two South Asian subgroups that are particularly vulnerable to suicide. These are young adults (aged 18-24 years) and women.7

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young Asian American men in the United States. Rates of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts are higher among younger Asian Americans (aged 18-24 years) than among older Asian American adults. Young Asian American adults have been found to have higher levels of suicidal ideation than their white counterparts.8,9 Acculturation or assimilating into a different culture, familial violence as a child, hopelessness or a thought pattern with a pessimistic outlook, depression, and childhood sexual abuse have all been found to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in South Asian Americans. One study that conducted0 in-group analysis on undergraduate university students of South Asian descent living in New York found higher levels of hopelessness and depression in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans.10

In addition, higher levels of suicidal ideation are reported in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans. These results resemble findings from similar studies in the United Kingdom. A posited reason for these findings is a difference in religious beliefs. Pakistani and Bangladeshi Americans are predominantly Muslim, have stronger moral beliefs against suicide, and consider it a sin as defined by Islamic beliefs. Asian Indians, in contrast, are majority Hindu and believe in reincarnation – a context that might make suicide seem more permissible.11

South Asian women are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and/or familial violence. Cultural gender norms, traditional norms, and patriarchal ideology in the South Asian community make quantifying the level of childhood sexual abuse and familial violence a challenge. Furthermore, culturally, South Asian women are often considered subordinate relative to men, and discussion around family violence and childhood sexual abuse is avoided. Studies from the United Kingdom find a lack of knowledge around, disclosure of, and fear of reporting childhood sexual abuse in South Asian women. A study of a sample of representative South Asian American women found that 25.2% had experienced some form of childhood sexual abuse.12

Research also suggests that South Asians in the United States have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence. Another study in the United States found that two out of five South Asian women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence. This is much higher than the rate found in representative general U.S. population samples.

Literature suggests that exposure to these factors increases womens’ risk for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide. In the United Kingdom, research on South Asian women (aged 18-24 years) has found rates of attempted suicide to be three times higher than those of their white counterparts. Research from the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that younger married South Asian women are exposed to emotional and/or physical abuse from their spouse or in-laws, which is often a mediating factor in their increased risk for suicide.

Attempts to address suicide in the South Asian American community have to be multifaceted. An ideal approach would consist of educating, and connecting with, the community through ethnic media and trusted community sources, such as primary care doctors, caregivers, and social workers. In line with established American Psychological Association guidelines on caring for individuals of immigrant origin, health care professionals should document the patient’s number of generations in the country, number of years in the country, language fluency, family and community support, educational level, social status changes related to immigration, intimate relationships with people of different backgrounds, and stress related to acculturation. Special attention should be paid to South Asian women. Health care professionals should screen South Asian women for past and current intimate partner violence, provide culturally appropriate intimate partner violence resources, and be prepared to refer them to legal counseling services. Also, South Asian women should be screened for a history of exposure to familial violence and childhood sexual abuse.1

To adequately serve this population, there is a need to build capacity in the provision of culturally appropriate mental health services. Access to mental health care professionals through settings such as shelters for abused women, South Asian community–based organizations, youth centers, college counseling, and senior centers would encourage individuals to seek care without the threat of being stigmatized.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 330. 2018 Nov.

2. Ahmad-Stout DJ and Nath SR. J College Stud Psychother. 2013 Jan 10;27(1):43-61.

3. Li H and Keshavan M. Asian J Psychiatry. 2011;4(1):1.

4. Nagaraj NC et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019 Oct;21(5):978-1003.

5. Nagaraj NC et al. J Comm Health. 2018;43(3):543-51.

6. Cao KO. Generations. 2014;30(4):82-5.

7. Hurwitz EJ et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):251-61.

8. Polanco-Roman L et al. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019 Dec 23. doi: 10.1037/cpd0000313.

9. Erausquin JT et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Sep;48(9):1796-1805.

10. Lane R et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2016;7(2):120-8.

11. Nath SR et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2018;9(4):334-343.

12. Robertson HA et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016 Jul 31;18(4):921-7.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University (CMU) College of Medicine, Mt. Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in immigrant populations.

Multifaceted strategies are needed to address unique cultural factors

Multifaceted strategies are needed to address unique cultural factors

On first glance, the age-adjusted rate of suicide for Asian and Pacific Islander populations living in the United States looks comparatively low.

Over the past 2 decades in the United States, for example, the overall rate increased by 35%, from, 10.5 to 14.2 per 100,000 individuals. That compares with a rate of 7.0 per 100,000 among Asian and Pacific Islander communities.1

However, because of the aggregate nature (national suicide mortality data combine people of Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander descent into a single group) in which these data are reported, a significant amount of salient information on subgroups of Asian Americans is lost.2 There is a growing body of research on the mental health of Asian Americans, but the dearth of information and research on suicide in South Asians is striking.3 In fact, a review of literature finds fewer than 10 articles on the topic that have been published in peer-reviewed journals in the last decade. to provide effective, culturally sensitive care.

Diverse group

There are 3.4 million individuals of South Asian descent in the United States. Geographically, South Asians may have familial and cultural/historical roots in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan.4 They enjoy a rich diversity in terms of cultural and religious beliefs, language, socioeconomic status, modes of acculturation, and immigration patterns. Asian Indians are the largest group of South Asians in the United States. They are highly educated, with a larger proportion of them pursuing an undergraduate and/or graduate level education than the general population. The median household income of Asian Indians is also higher than the national average.5

In general, suicide, like all mental health issues, is a stigmatized and taboo topic in the South Asian community.6 Also, South Asian Americans are hesitant to seek mental health care because of a perceived inability of Western health care professionals to understand their cultural views. Extrapolation from data on South Asians in the United Kingdom, aggregate statistics for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and studies on South Asians in the United States highlight two South Asian subgroups that are particularly vulnerable to suicide. These are young adults (aged 18-24 years) and women.7

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young Asian American men in the United States. Rates of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts are higher among younger Asian Americans (aged 18-24 years) than among older Asian American adults. Young Asian American adults have been found to have higher levels of suicidal ideation than their white counterparts.8,9 Acculturation or assimilating into a different culture, familial violence as a child, hopelessness or a thought pattern with a pessimistic outlook, depression, and childhood sexual abuse have all been found to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in South Asian Americans. One study that conducted0 in-group analysis on undergraduate university students of South Asian descent living in New York found higher levels of hopelessness and depression in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans.10

In addition, higher levels of suicidal ideation are reported in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans. These results resemble findings from similar studies in the United Kingdom. A posited reason for these findings is a difference in religious beliefs. Pakistani and Bangladeshi Americans are predominantly Muslim, have stronger moral beliefs against suicide, and consider it a sin as defined by Islamic beliefs. Asian Indians, in contrast, are majority Hindu and believe in reincarnation – a context that might make suicide seem more permissible.11

South Asian women are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and/or familial violence. Cultural gender norms, traditional norms, and patriarchal ideology in the South Asian community make quantifying the level of childhood sexual abuse and familial violence a challenge. Furthermore, culturally, South Asian women are often considered subordinate relative to men, and discussion around family violence and childhood sexual abuse is avoided. Studies from the United Kingdom find a lack of knowledge around, disclosure of, and fear of reporting childhood sexual abuse in South Asian women. A study of a sample of representative South Asian American women found that 25.2% had experienced some form of childhood sexual abuse.12

Research also suggests that South Asians in the United States have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence. Another study in the United States found that two out of five South Asian women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence. This is much higher than the rate found in representative general U.S. population samples.

Literature suggests that exposure to these factors increases womens’ risk for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide. In the United Kingdom, research on South Asian women (aged 18-24 years) has found rates of attempted suicide to be three times higher than those of their white counterparts. Research from the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that younger married South Asian women are exposed to emotional and/or physical abuse from their spouse or in-laws, which is often a mediating factor in their increased risk for suicide.

Attempts to address suicide in the South Asian American community have to be multifaceted. An ideal approach would consist of educating, and connecting with, the community through ethnic media and trusted community sources, such as primary care doctors, caregivers, and social workers. In line with established American Psychological Association guidelines on caring for individuals of immigrant origin, health care professionals should document the patient’s number of generations in the country, number of years in the country, language fluency, family and community support, educational level, social status changes related to immigration, intimate relationships with people of different backgrounds, and stress related to acculturation. Special attention should be paid to South Asian women. Health care professionals should screen South Asian women for past and current intimate partner violence, provide culturally appropriate intimate partner violence resources, and be prepared to refer them to legal counseling services. Also, South Asian women should be screened for a history of exposure to familial violence and childhood sexual abuse.1

To adequately serve this population, there is a need to build capacity in the provision of culturally appropriate mental health services. Access to mental health care professionals through settings such as shelters for abused women, South Asian community–based organizations, youth centers, college counseling, and senior centers would encourage individuals to seek care without the threat of being stigmatized.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 330. 2018 Nov.

2. Ahmad-Stout DJ and Nath SR. J College Stud Psychother. 2013 Jan 10;27(1):43-61.

3. Li H and Keshavan M. Asian J Psychiatry. 2011;4(1):1.

4. Nagaraj NC et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019 Oct;21(5):978-1003.

5. Nagaraj NC et al. J Comm Health. 2018;43(3):543-51.

6. Cao KO. Generations. 2014;30(4):82-5.

7. Hurwitz EJ et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):251-61.

8. Polanco-Roman L et al. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019 Dec 23. doi: 10.1037/cpd0000313.

9. Erausquin JT et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Sep;48(9):1796-1805.

10. Lane R et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2016;7(2):120-8.

11. Nath SR et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2018;9(4):334-343.

12. Robertson HA et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016 Jul 31;18(4):921-7.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University (CMU) College of Medicine, Mt. Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in immigrant populations.

On first glance, the age-adjusted rate of suicide for Asian and Pacific Islander populations living in the United States looks comparatively low.

Over the past 2 decades in the United States, for example, the overall rate increased by 35%, from, 10.5 to 14.2 per 100,000 individuals. That compares with a rate of 7.0 per 100,000 among Asian and Pacific Islander communities.1

However, because of the aggregate nature (national suicide mortality data combine people of Asian, Native Hawaiian, and other Pacific Islander descent into a single group) in which these data are reported, a significant amount of salient information on subgroups of Asian Americans is lost.2 There is a growing body of research on the mental health of Asian Americans, but the dearth of information and research on suicide in South Asians is striking.3 In fact, a review of literature finds fewer than 10 articles on the topic that have been published in peer-reviewed journals in the last decade. to provide effective, culturally sensitive care.

Diverse group

There are 3.4 million individuals of South Asian descent in the United States. Geographically, South Asians may have familial and cultural/historical roots in Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, and Pakistan.4 They enjoy a rich diversity in terms of cultural and religious beliefs, language, socioeconomic status, modes of acculturation, and immigration patterns. Asian Indians are the largest group of South Asians in the United States. They are highly educated, with a larger proportion of them pursuing an undergraduate and/or graduate level education than the general population. The median household income of Asian Indians is also higher than the national average.5

In general, suicide, like all mental health issues, is a stigmatized and taboo topic in the South Asian community.6 Also, South Asian Americans are hesitant to seek mental health care because of a perceived inability of Western health care professionals to understand their cultural views. Extrapolation from data on South Asians in the United Kingdom, aggregate statistics for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders, and studies on South Asians in the United States highlight two South Asian subgroups that are particularly vulnerable to suicide. These are young adults (aged 18-24 years) and women.7

Suicide is the second-leading cause of death for young Asian American men in the United States. Rates of lifetime suicidal ideation and attempts are higher among younger Asian Americans (aged 18-24 years) than among older Asian American adults. Young Asian American adults have been found to have higher levels of suicidal ideation than their white counterparts.8,9 Acculturation or assimilating into a different culture, familial violence as a child, hopelessness or a thought pattern with a pessimistic outlook, depression, and childhood sexual abuse have all been found to be positively correlated with suicidal ideation and attempted suicide in South Asian Americans. One study that conducted0 in-group analysis on undergraduate university students of South Asian descent living in New York found higher levels of hopelessness and depression in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans.10

In addition, higher levels of suicidal ideation are reported in Asian Indians relative to Bangladeshi or Pakistani Americans. These results resemble findings from similar studies in the United Kingdom. A posited reason for these findings is a difference in religious beliefs. Pakistani and Bangladeshi Americans are predominantly Muslim, have stronger moral beliefs against suicide, and consider it a sin as defined by Islamic beliefs. Asian Indians, in contrast, are majority Hindu and believe in reincarnation – a context that might make suicide seem more permissible.11

South Asian women are particularly vulnerable to domestic violence, childhood sexual abuse, intimate partner violence, and/or familial violence. Cultural gender norms, traditional norms, and patriarchal ideology in the South Asian community make quantifying the level of childhood sexual abuse and familial violence a challenge. Furthermore, culturally, South Asian women are often considered subordinate relative to men, and discussion around family violence and childhood sexual abuse is avoided. Studies from the United Kingdom find a lack of knowledge around, disclosure of, and fear of reporting childhood sexual abuse in South Asian women. A study of a sample of representative South Asian American women found that 25.2% had experienced some form of childhood sexual abuse.12

Research also suggests that South Asians in the United States have some of the highest rates of intimate partner violence. Another study in the United States found that two out of five South Asian women have experienced physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence. This is much higher than the rate found in representative general U.S. population samples.

Literature suggests that exposure to these factors increases womens’ risk for suicidal ideation and attempted suicide. In the United Kingdom, research on South Asian women (aged 18-24 years) has found rates of attempted suicide to be three times higher than those of their white counterparts. Research from the United Kingdom and the United States suggests that younger married South Asian women are exposed to emotional and/or physical abuse from their spouse or in-laws, which is often a mediating factor in their increased risk for suicide.

Attempts to address suicide in the South Asian American community have to be multifaceted. An ideal approach would consist of educating, and connecting with, the community through ethnic media and trusted community sources, such as primary care doctors, caregivers, and social workers. In line with established American Psychological Association guidelines on caring for individuals of immigrant origin, health care professionals should document the patient’s number of generations in the country, number of years in the country, language fluency, family and community support, educational level, social status changes related to immigration, intimate relationships with people of different backgrounds, and stress related to acculturation. Special attention should be paid to South Asian women. Health care professionals should screen South Asian women for past and current intimate partner violence, provide culturally appropriate intimate partner violence resources, and be prepared to refer them to legal counseling services. Also, South Asian women should be screened for a history of exposure to familial violence and childhood sexual abuse.1

To adequately serve this population, there is a need to build capacity in the provision of culturally appropriate mental health services. Access to mental health care professionals through settings such as shelters for abused women, South Asian community–based organizations, youth centers, college counseling, and senior centers would encourage individuals to seek care without the threat of being stigmatized.

References

1. Hedegaard H et al. Suicide mortality in the United States, 1999–2017. NCHS Data Brief, No. 330. 2018 Nov.

2. Ahmad-Stout DJ and Nath SR. J College Stud Psychother. 2013 Jan 10;27(1):43-61.

3. Li H and Keshavan M. Asian J Psychiatry. 2011;4(1):1.

4. Nagaraj NC et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2019 Oct;21(5):978-1003.

5. Nagaraj NC et al. J Comm Health. 2018;43(3):543-51.

6. Cao KO. Generations. 2014;30(4):82-5.

7. Hurwitz EJ et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(3):251-61.

8. Polanco-Roman L et al. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019 Dec 23. doi: 10.1037/cpd0000313.

9. Erausquin JT et al. J Youth Adolesc. 2019 Sep;48(9):1796-1805.

10. Lane R et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2016;7(2):120-8.

11. Nath SR et al. Asian Am J Psychol. 2018;9(4):334-343.

12. Robertson HA et al. J Immigr Minor Health. 2016 Jul 31;18(4):921-7.

Mr. Kaleka is a medical student in the class of 2021 at Central Michigan University (CMU) College of Medicine, Mt. Pleasant. He has no disclosures. Mr. Kaleka would like to thank his mentor, Furhut Janssen, DO, for her continued guidance and support in research on mental health in immigrant populations.

Mental health visits account for 19% of ED costs

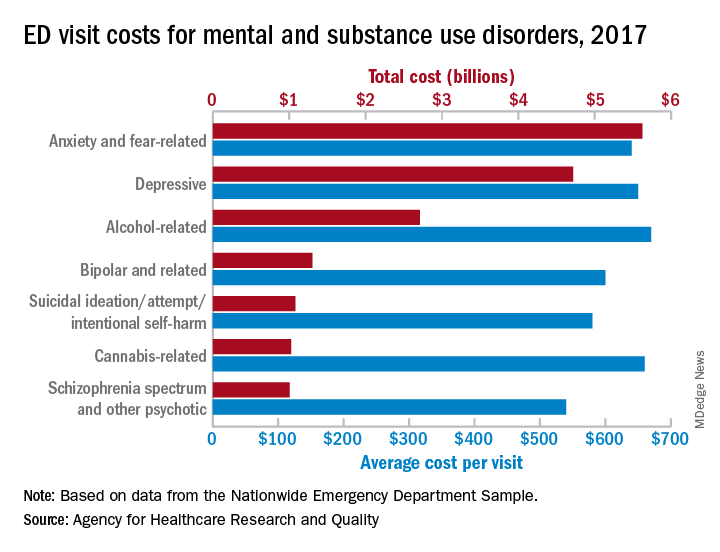

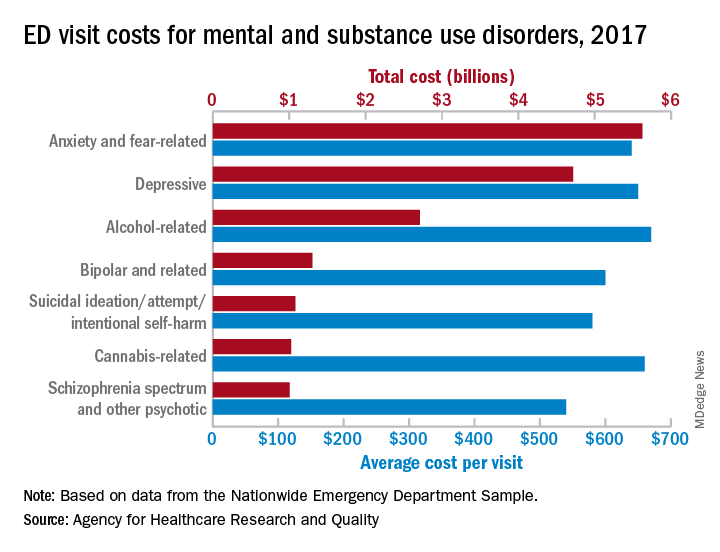

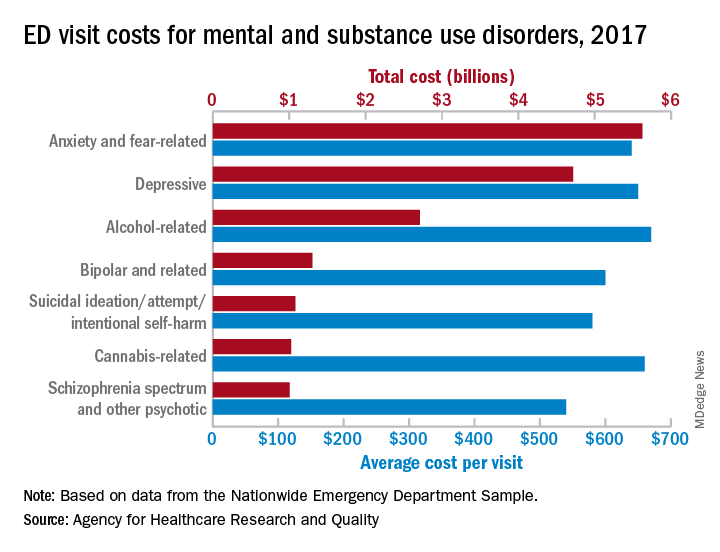

Emergency department visits for mental and substance use disorders (MUSDs) cost $14.6 billion in 2017, representing 19% of the total for all ED visits that year, according to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

In terms of the total number of visits for MUSDs, 23.1 million, the proportion was slightly lower: 16% of all ED visits for the year, Zeynal Karaca, PhD, a senior economist with AHRQ, and Brian J. Moore, PhD, a senior research leader at IBM Watson Health, said in a recent statistical brief.

Put those figures together and the average visit for an MUSD diagnosis cost $630 and that is 19% higher than the average of $530 for all 145 million ED visits, they reported based on data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The most costly MUSD diagnosis in 2017 was anxiety and fear-related disorders, with a total of $5.6 billion for ED visits, followed by depressive disorders at $4.7 billion and alcohol-related disorders at $2.7 billion. Some ED visits may involve more than one MUSD diagnosis, so the sum of all the individual diagnoses does not agree with the total for the entire MUSD category, the researchers noted.

On a per-visit basis, in 2017. [It was not included in the graph because it was 13th.] Other disorders with high per-visit costs were alcohol-related ($670), cannabis-related ($660), and depressive and stimulant-related (both with $650), Dr. Karaca and Dr. Moore said.

Patients with MUSDs who were routinely discharged after an ED visit in 2017 represented a much lower share of the total MUSD cost (68.0%), compared with the overall group of ED visitors (81.4%), but MUSD visits resulting in an inpatient admission made up a larger proportion of costs (19.0%), compared with all visits (9.5%), they said.

Costs between MUSD visits and all ED visits also differed by patient age. Visits by patients aged 0-9 years represented only 0.7% of MUSD-related ED costs but 5.6% of the overall cost, but the respective figures for those aged 45-64 were 36.2% for MUSD costs and 28.5% for the total ED cost, they reported.

SOURCE: Karaca Z and Moore BJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #257. May 12, 2020.

Emergency department visits for mental and substance use disorders (MUSDs) cost $14.6 billion in 2017, representing 19% of the total for all ED visits that year, according to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

In terms of the total number of visits for MUSDs, 23.1 million, the proportion was slightly lower: 16% of all ED visits for the year, Zeynal Karaca, PhD, a senior economist with AHRQ, and Brian J. Moore, PhD, a senior research leader at IBM Watson Health, said in a recent statistical brief.

Put those figures together and the average visit for an MUSD diagnosis cost $630 and that is 19% higher than the average of $530 for all 145 million ED visits, they reported based on data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The most costly MUSD diagnosis in 2017 was anxiety and fear-related disorders, with a total of $5.6 billion for ED visits, followed by depressive disorders at $4.7 billion and alcohol-related disorders at $2.7 billion. Some ED visits may involve more than one MUSD diagnosis, so the sum of all the individual diagnoses does not agree with the total for the entire MUSD category, the researchers noted.

On a per-visit basis, in 2017. [It was not included in the graph because it was 13th.] Other disorders with high per-visit costs were alcohol-related ($670), cannabis-related ($660), and depressive and stimulant-related (both with $650), Dr. Karaca and Dr. Moore said.

Patients with MUSDs who were routinely discharged after an ED visit in 2017 represented a much lower share of the total MUSD cost (68.0%), compared with the overall group of ED visitors (81.4%), but MUSD visits resulting in an inpatient admission made up a larger proportion of costs (19.0%), compared with all visits (9.5%), they said.

Costs between MUSD visits and all ED visits also differed by patient age. Visits by patients aged 0-9 years represented only 0.7% of MUSD-related ED costs but 5.6% of the overall cost, but the respective figures for those aged 45-64 were 36.2% for MUSD costs and 28.5% for the total ED cost, they reported.

SOURCE: Karaca Z and Moore BJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #257. May 12, 2020.

Emergency department visits for mental and substance use disorders (MUSDs) cost $14.6 billion in 2017, representing 19% of the total for all ED visits that year, according to the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research.

In terms of the total number of visits for MUSDs, 23.1 million, the proportion was slightly lower: 16% of all ED visits for the year, Zeynal Karaca, PhD, a senior economist with AHRQ, and Brian J. Moore, PhD, a senior research leader at IBM Watson Health, said in a recent statistical brief.

Put those figures together and the average visit for an MUSD diagnosis cost $630 and that is 19% higher than the average of $530 for all 145 million ED visits, they reported based on data from the Nationwide Emergency Department Sample.

The most costly MUSD diagnosis in 2017 was anxiety and fear-related disorders, with a total of $5.6 billion for ED visits, followed by depressive disorders at $4.7 billion and alcohol-related disorders at $2.7 billion. Some ED visits may involve more than one MUSD diagnosis, so the sum of all the individual diagnoses does not agree with the total for the entire MUSD category, the researchers noted.

On a per-visit basis, in 2017. [It was not included in the graph because it was 13th.] Other disorders with high per-visit costs were alcohol-related ($670), cannabis-related ($660), and depressive and stimulant-related (both with $650), Dr. Karaca and Dr. Moore said.

Patients with MUSDs who were routinely discharged after an ED visit in 2017 represented a much lower share of the total MUSD cost (68.0%), compared with the overall group of ED visitors (81.4%), but MUSD visits resulting in an inpatient admission made up a larger proportion of costs (19.0%), compared with all visits (9.5%), they said.

Costs between MUSD visits and all ED visits also differed by patient age. Visits by patients aged 0-9 years represented only 0.7% of MUSD-related ED costs but 5.6% of the overall cost, but the respective figures for those aged 45-64 were 36.2% for MUSD costs and 28.5% for the total ED cost, they reported.

SOURCE: Karaca Z and Moore BJ. HCUP Statistical Brief #257. May 12, 2020.

Fracture risk higher for children with anxiety on benzodiazepines

a new study found, which offers further argument for caution with this class of drugs in young patients.

In research published in Pediatrics, Greta A. Bushnell, PhD, of Columbia University in New York and colleagues, looked at private insurance claims data including prescription records from 120,715 children aged 6-17 years diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and from 179,768 young adults aged 18-24 years also diagnosed with anxiety.

The investigators compared fracture incidence within 3 months of treatment initiation between the group prescribed benzodiazepines for anxiety and the group prescribed SSRIs. Subjects prescribed both classes of drugs were excluded from the analysis.

Of patients aged 6-17 years, 11% were prescribed benzodiazepines, with the remainder receiving SSRIs. Children on benzodiazepines saw 33 fractures per 1,000 person-years, compared with 25 of those on SSRIs, with an adjusted incidence rate ratio of 1.53. These were fractures in the upper and lower limbs.

Similar differences in fracture risk were not seen among the young adults in the study, of whom 32% were prescribed benzodiazepines and among whom fracture rates were low overall, 9 per 1,000 person-years in both medication groups.

Several SSRIs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat anxiety disorders in children, but benzodiazepines are used off label in youth. The drugs most commonly prescribed in the study were alprazolam and lorazepam, and 82% of the group in this study aged 6-17 years did not fill their prescriptions beyond 1 month.

In adults, benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to cause drowsiness, dizziness, and weakness, which can result in injury, and it also is associated with increased risk of car accidents, falls, and fractures. The higher fracture rate among children on benzodiazepine treatment seen in this study is similar to rates reported in studies of older adults, Dr. Bushnell and colleagues noted.

The researchers could not explain why the young adults in the study did not see a higher risk of fractures on benzodiazepines, compared with that among those taking SSRIs. They hypothesized that young adults are less active than children, with fewer opportunities for falls, and there were few fractures among the 18- to 24-year-old cohort in general.

David C. Rettew, MD, from the University of Vermont in Burlington, commented in an interview that, while there are plenty of reasons to be cautious about using benzodiazepines in youth, “fracture risk isn’t usually very prominent among them, so it is a nice reminder to have this on the radar screen.” Most clinicians, he said, already are quite wary of using benzodiazepines in children, which is suggested by the small proportion of children treated with them in this study.

“It seems quite possible that children and adolescents prescribed benzodiazepines are quite different clinically than the group prescribed SSRIs, despite the strong measures the study authors took to control for other variables between the two groups,” Dr. Rettew added. “I’d have to wonder if those clinical differences may be behind some of the fracture rate differences” seen in the study.

Dr. Bushnell and her colleagues acknowledged this among the study’s several limitations. “It is unclear how much unmeasured differences in psychiatric condition severity exist between youth initiating a benzodiazepine versus SSRI and how anxiety severity impacts fracture risk.” The researchers also noted that they could not measure use of the drugs beyond whether and when prescriptions were filled.

Dr. Bushnell and colleagues’ study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the National Institutes of Health. One of its coauthors disclosed financial relationships with several pharmaceutical manufacturers. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures

SOURCE: Bushnell GA et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3478.

a new study found, which offers further argument for caution with this class of drugs in young patients.

In research published in Pediatrics, Greta A. Bushnell, PhD, of Columbia University in New York and colleagues, looked at private insurance claims data including prescription records from 120,715 children aged 6-17 years diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and from 179,768 young adults aged 18-24 years also diagnosed with anxiety.

The investigators compared fracture incidence within 3 months of treatment initiation between the group prescribed benzodiazepines for anxiety and the group prescribed SSRIs. Subjects prescribed both classes of drugs were excluded from the analysis.

Of patients aged 6-17 years, 11% were prescribed benzodiazepines, with the remainder receiving SSRIs. Children on benzodiazepines saw 33 fractures per 1,000 person-years, compared with 25 of those on SSRIs, with an adjusted incidence rate ratio of 1.53. These were fractures in the upper and lower limbs.

Similar differences in fracture risk were not seen among the young adults in the study, of whom 32% were prescribed benzodiazepines and among whom fracture rates were low overall, 9 per 1,000 person-years in both medication groups.

Several SSRIs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat anxiety disorders in children, but benzodiazepines are used off label in youth. The drugs most commonly prescribed in the study were alprazolam and lorazepam, and 82% of the group in this study aged 6-17 years did not fill their prescriptions beyond 1 month.

In adults, benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to cause drowsiness, dizziness, and weakness, which can result in injury, and it also is associated with increased risk of car accidents, falls, and fractures. The higher fracture rate among children on benzodiazepine treatment seen in this study is similar to rates reported in studies of older adults, Dr. Bushnell and colleagues noted.

The researchers could not explain why the young adults in the study did not see a higher risk of fractures on benzodiazepines, compared with that among those taking SSRIs. They hypothesized that young adults are less active than children, with fewer opportunities for falls, and there were few fractures among the 18- to 24-year-old cohort in general.

David C. Rettew, MD, from the University of Vermont in Burlington, commented in an interview that, while there are plenty of reasons to be cautious about using benzodiazepines in youth, “fracture risk isn’t usually very prominent among them, so it is a nice reminder to have this on the radar screen.” Most clinicians, he said, already are quite wary of using benzodiazepines in children, which is suggested by the small proportion of children treated with them in this study.

“It seems quite possible that children and adolescents prescribed benzodiazepines are quite different clinically than the group prescribed SSRIs, despite the strong measures the study authors took to control for other variables between the two groups,” Dr. Rettew added. “I’d have to wonder if those clinical differences may be behind some of the fracture rate differences” seen in the study.

Dr. Bushnell and her colleagues acknowledged this among the study’s several limitations. “It is unclear how much unmeasured differences in psychiatric condition severity exist between youth initiating a benzodiazepine versus SSRI and how anxiety severity impacts fracture risk.” The researchers also noted that they could not measure use of the drugs beyond whether and when prescriptions were filled.

Dr. Bushnell and colleagues’ study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the National Institutes of Health. One of its coauthors disclosed financial relationships with several pharmaceutical manufacturers. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures

SOURCE: Bushnell GA et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3478.

a new study found, which offers further argument for caution with this class of drugs in young patients.

In research published in Pediatrics, Greta A. Bushnell, PhD, of Columbia University in New York and colleagues, looked at private insurance claims data including prescription records from 120,715 children aged 6-17 years diagnosed with an anxiety disorder and from 179,768 young adults aged 18-24 years also diagnosed with anxiety.

The investigators compared fracture incidence within 3 months of treatment initiation between the group prescribed benzodiazepines for anxiety and the group prescribed SSRIs. Subjects prescribed both classes of drugs were excluded from the analysis.

Of patients aged 6-17 years, 11% were prescribed benzodiazepines, with the remainder receiving SSRIs. Children on benzodiazepines saw 33 fractures per 1,000 person-years, compared with 25 of those on SSRIs, with an adjusted incidence rate ratio of 1.53. These were fractures in the upper and lower limbs.

Similar differences in fracture risk were not seen among the young adults in the study, of whom 32% were prescribed benzodiazepines and among whom fracture rates were low overall, 9 per 1,000 person-years in both medication groups.

Several SSRIs have been approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat anxiety disorders in children, but benzodiazepines are used off label in youth. The drugs most commonly prescribed in the study were alprazolam and lorazepam, and 82% of the group in this study aged 6-17 years did not fill their prescriptions beyond 1 month.

In adults, benzodiazepine treatment has been shown to cause drowsiness, dizziness, and weakness, which can result in injury, and it also is associated with increased risk of car accidents, falls, and fractures. The higher fracture rate among children on benzodiazepine treatment seen in this study is similar to rates reported in studies of older adults, Dr. Bushnell and colleagues noted.

The researchers could not explain why the young adults in the study did not see a higher risk of fractures on benzodiazepines, compared with that among those taking SSRIs. They hypothesized that young adults are less active than children, with fewer opportunities for falls, and there were few fractures among the 18- to 24-year-old cohort in general.

David C. Rettew, MD, from the University of Vermont in Burlington, commented in an interview that, while there are plenty of reasons to be cautious about using benzodiazepines in youth, “fracture risk isn’t usually very prominent among them, so it is a nice reminder to have this on the radar screen.” Most clinicians, he said, already are quite wary of using benzodiazepines in children, which is suggested by the small proportion of children treated with them in this study.

“It seems quite possible that children and adolescents prescribed benzodiazepines are quite different clinically than the group prescribed SSRIs, despite the strong measures the study authors took to control for other variables between the two groups,” Dr. Rettew added. “I’d have to wonder if those clinical differences may be behind some of the fracture rate differences” seen in the study.

Dr. Bushnell and her colleagues acknowledged this among the study’s several limitations. “It is unclear how much unmeasured differences in psychiatric condition severity exist between youth initiating a benzodiazepine versus SSRI and how anxiety severity impacts fracture risk.” The researchers also noted that they could not measure use of the drugs beyond whether and when prescriptions were filled.

Dr. Bushnell and colleagues’ study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health and by grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the National Institutes of Health. One of its coauthors disclosed financial relationships with several pharmaceutical manufacturers. Dr. Rettew said he had no relevant financial disclosures

SOURCE: Bushnell GA et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3478.

FROM PEDIATRICS

Key clinical point: Children aged 6-17 years prescribed sedatives for anxiety saw a higher risk of fractures, compared with those on SSRIs.

Major finding: Children prescribed benzodiazepines for anxiety had 33 fractures per 1,000 person-years versus 25 among children prescribed SSRIs (adjusted incidence rate ratio, 1.53).

Study details: A retrospective cohort study using commercial insurance claims data from 120,715 children aged 6-17 years and 179,768 young adults ages 18-24 years from 2007 through 2016, all with anxiety diagnoses and prescribed either benzodiazepines or SSRIs.

Disclosures: Dr. Bushnell and colleagues’ study was funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, and grants from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, and the National Institutes of Health. One of its coauthors disclosed financial relationships with several pharmaceutical manufacturers.

Source: Bushnell GA et al. Pediatrics. 2020 Jun. doi: 10.1542/peds.2019-3478.

Atopic dermatitis in adults, children linked to neuropsychiatric disorders

according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

“The risk increase ranges from as low as 5% up to 59%, depending on the outcome, with generally greater effects observed among the adults,” Joy Wan, MD, a postdoctoral dermatology fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in her presentation. The risk was independent of other atopic disease, gender, age, and socioeconomic status.

Dr. Wan and colleagues conducted a cohort study of patients with AD in the United Kingdom using data from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) electronic records database, matching AD patients in THIN with up to five patients without AD, similar in age and also registered to general practices. The researchers validated AD disease status using an algorithm that identified patients with a diagnostic code and two therapy codes related to AD. Outcomes of interest included anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, schizophrenia, and autism. Patients entered into the cohort when they were diagnosed with AD, registered by a practice, or when data from a practice was reported to THIN. The researchers stopped following patients when they developed a neuropsychiatric outcome of interest, left a practice, died, or when the study ended.

“Previous studies have found associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. However, many previous studies had been cross-sectional and they were unable to evaluate the directionality of association between atopic dermatitis and neuropsychiatric outcomes, while other previous studies have relied on the self-report of atopic dermatitis and outcomes as well,” Dr. Wan said. “Thus, longitudinal studies, using validated measures of atopic dermatitis, and those that include the entire age span, are really needed.”

Overall, 434,859 children and adolescents under aged 18 with AD in the THIN database were matched to 1,983,589 controls, and 644,802 adults with AD were matched to almost 2,900,000 adults without AD. In the pediatric group, demographics were mostly balanced between children with and without AD: the average age ranged between about 5 and almost 6 years. In pediatric patients with AD, there was a higher rate of allergic rhinitis (6.2% vs. 4%) and asthma (13.5% vs. 9.3%) than in the control group.

For adults, the average age was about 48 years in both groups. Compared with patients who did not have AD, adults with AD also had higher rates of allergic rhinitis (15.2% vs. 9.6%) and asthma (19.9% vs. 12.6%).

After adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, Dr. Wan and colleagues found greater rates of bipolar disorder (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.65), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.41), anxiety (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11), and depression (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) among children and adolescents with AD, compared with controls.

In the adult cohort, a diagnosis of AD was associated with an increased risk of autism (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.40-1.59), ADHD (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.53), anxiety (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.15-1.18), depression (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14-1.16), and bipolar disorder (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21), after adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

One reason for the increased associations among the adults, even for ADHD and autism, which are more characteristically diagnosed in childhood, Dr. Wan said, is that, since they looked at incident outcomes, “many children may already have had these prevalent comorbidities at the time of the entry in the cohort.”

She noted that the study may have observation bias or unknown confounders, but she hopes these results raise awareness of the association between AD and neuropsychiatric disorders, although more research is needed to determine how AD severity affects neuropsychiatric outcomes. “Additional work is needed to really understand the mechanisms that drive these associations, whether it’s mediated through symptoms of atopic dermatitis such as itch and poor sleep, or potentially the stigma of having a chronic skin disease, or perhaps shared pathophysiology between atopic dermatitis and these neuropsychiatric diseases,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from Pfizer. Dr. Wan reports receiving research funding from Pfizer paid to the University of Pennsylvania.

according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

“The risk increase ranges from as low as 5% up to 59%, depending on the outcome, with generally greater effects observed among the adults,” Joy Wan, MD, a postdoctoral dermatology fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in her presentation. The risk was independent of other atopic disease, gender, age, and socioeconomic status.

Dr. Wan and colleagues conducted a cohort study of patients with AD in the United Kingdom using data from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) electronic records database, matching AD patients in THIN with up to five patients without AD, similar in age and also registered to general practices. The researchers validated AD disease status using an algorithm that identified patients with a diagnostic code and two therapy codes related to AD. Outcomes of interest included anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, schizophrenia, and autism. Patients entered into the cohort when they were diagnosed with AD, registered by a practice, or when data from a practice was reported to THIN. The researchers stopped following patients when they developed a neuropsychiatric outcome of interest, left a practice, died, or when the study ended.

“Previous studies have found associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. However, many previous studies had been cross-sectional and they were unable to evaluate the directionality of association between atopic dermatitis and neuropsychiatric outcomes, while other previous studies have relied on the self-report of atopic dermatitis and outcomes as well,” Dr. Wan said. “Thus, longitudinal studies, using validated measures of atopic dermatitis, and those that include the entire age span, are really needed.”

Overall, 434,859 children and adolescents under aged 18 with AD in the THIN database were matched to 1,983,589 controls, and 644,802 adults with AD were matched to almost 2,900,000 adults without AD. In the pediatric group, demographics were mostly balanced between children with and without AD: the average age ranged between about 5 and almost 6 years. In pediatric patients with AD, there was a higher rate of allergic rhinitis (6.2% vs. 4%) and asthma (13.5% vs. 9.3%) than in the control group.

For adults, the average age was about 48 years in both groups. Compared with patients who did not have AD, adults with AD also had higher rates of allergic rhinitis (15.2% vs. 9.6%) and asthma (19.9% vs. 12.6%).

After adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, Dr. Wan and colleagues found greater rates of bipolar disorder (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.65), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.41), anxiety (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11), and depression (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) among children and adolescents with AD, compared with controls.

In the adult cohort, a diagnosis of AD was associated with an increased risk of autism (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.40-1.59), ADHD (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.53), anxiety (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.15-1.18), depression (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14-1.16), and bipolar disorder (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21), after adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

One reason for the increased associations among the adults, even for ADHD and autism, which are more characteristically diagnosed in childhood, Dr. Wan said, is that, since they looked at incident outcomes, “many children may already have had these prevalent comorbidities at the time of the entry in the cohort.”

She noted that the study may have observation bias or unknown confounders, but she hopes these results raise awareness of the association between AD and neuropsychiatric disorders, although more research is needed to determine how AD severity affects neuropsychiatric outcomes. “Additional work is needed to really understand the mechanisms that drive these associations, whether it’s mediated through symptoms of atopic dermatitis such as itch and poor sleep, or potentially the stigma of having a chronic skin disease, or perhaps shared pathophysiology between atopic dermatitis and these neuropsychiatric diseases,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from Pfizer. Dr. Wan reports receiving research funding from Pfizer paid to the University of Pennsylvania.

according to a study presented at the annual meeting of the Society for Investigative Dermatology, held virtually.

“The risk increase ranges from as low as 5% up to 59%, depending on the outcome, with generally greater effects observed among the adults,” Joy Wan, MD, a postdoctoral dermatology fellow at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in her presentation. The risk was independent of other atopic disease, gender, age, and socioeconomic status.

Dr. Wan and colleagues conducted a cohort study of patients with AD in the United Kingdom using data from the Health Improvement Network (THIN) electronic records database, matching AD patients in THIN with up to five patients without AD, similar in age and also registered to general practices. The researchers validated AD disease status using an algorithm that identified patients with a diagnostic code and two therapy codes related to AD. Outcomes of interest included anxiety, depression, bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, ADHD, schizophrenia, and autism. Patients entered into the cohort when they were diagnosed with AD, registered by a practice, or when data from a practice was reported to THIN. The researchers stopped following patients when they developed a neuropsychiatric outcome of interest, left a practice, died, or when the study ended.

“Previous studies have found associations between atopic dermatitis and anxiety, depression, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. However, many previous studies had been cross-sectional and they were unable to evaluate the directionality of association between atopic dermatitis and neuropsychiatric outcomes, while other previous studies have relied on the self-report of atopic dermatitis and outcomes as well,” Dr. Wan said. “Thus, longitudinal studies, using validated measures of atopic dermatitis, and those that include the entire age span, are really needed.”

Overall, 434,859 children and adolescents under aged 18 with AD in the THIN database were matched to 1,983,589 controls, and 644,802 adults with AD were matched to almost 2,900,000 adults without AD. In the pediatric group, demographics were mostly balanced between children with and without AD: the average age ranged between about 5 and almost 6 years. In pediatric patients with AD, there was a higher rate of allergic rhinitis (6.2% vs. 4%) and asthma (13.5% vs. 9.3%) than in the control group.

For adults, the average age was about 48 years in both groups. Compared with patients who did not have AD, adults with AD also had higher rates of allergic rhinitis (15.2% vs. 9.6%) and asthma (19.9% vs. 12.6%).

After adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis, Dr. Wan and colleagues found greater rates of bipolar disorder (hazard ratio, 1.34; 95% confidence interval, 1.09-1.65), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.30; 95% CI, 1.21-1.41), anxiety (HR, 1.09; 95% CI, 1.07-1.11), and depression (HR, 1.06; 95% CI, 1.04-1.08) among children and adolescents with AD, compared with controls.

In the adult cohort, a diagnosis of AD was associated with an increased risk of autism (HR, 1.53; 95% CI, 1.30-1.80), obsessive-compulsive disorder (HR, 1.49; 95% CI, 1.40-1.59), ADHD (HR, 1.31; 95% CI, 1.13-1.53), anxiety (HR, 1.17; 95% CI, 1.15-1.18), depression (HR, 1.15; 95% CI, 1.14-1.16), and bipolar disorder (HR, 1.12; 95% CI, 1.04-1.21), after adjusting for age, gender, socioeconomic status, asthma, and allergic rhinitis.

One reason for the increased associations among the adults, even for ADHD and autism, which are more characteristically diagnosed in childhood, Dr. Wan said, is that, since they looked at incident outcomes, “many children may already have had these prevalent comorbidities at the time of the entry in the cohort.”

She noted that the study may have observation bias or unknown confounders, but she hopes these results raise awareness of the association between AD and neuropsychiatric disorders, although more research is needed to determine how AD severity affects neuropsychiatric outcomes. “Additional work is needed to really understand the mechanisms that drive these associations, whether it’s mediated through symptoms of atopic dermatitis such as itch and poor sleep, or potentially the stigma of having a chronic skin disease, or perhaps shared pathophysiology between atopic dermatitis and these neuropsychiatric diseases,” she said.

The study was funded by a grant from Pfizer. Dr. Wan reports receiving research funding from Pfizer paid to the University of Pennsylvania.

FROM SID 2020

COVID-19 ravaging the Navajo Nation

The Navajo people have dealt with adversity that has tested our strength and resilience since our creation. In Navajo culture, the Holy People or gods challenged us with Naayee (monsters). We endured and learned from each Naayee, hunger, and death to name a few adversities. The COVID-19 pandemic, or “Big Cough” (Dikos Nitsaa’igii -19 in Navajo language) is a monster confronting the Navajo today. It has had significant impact on our nation and people.

The Navajo have the most cases of the COVID-19 virus of any tribe in the United States, and numbers as of May 31, 2020, are 5,348, with 246 confirmed deaths.1 The Navajo Nation, which once lagged behind New York, has reported the largest per-capita infection rate in the United States.

These devastating numbers, which might be leveling off, are associated with Navajo people having higher-than-average numbers of diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. This is compounded with 30%-40% of homes having no electricity or running water, and a poverty rate of about 38%.2

Geographical and cultural factors also contribute to the inability to gain a foothold in mitigating the number of cases. The Navajo Nation is the largest tribe in the United States, covering 27,000 square miles over an arid, red rock expanse with canyons and mountains. The population is over 250,000,3 and Navajo have traditionally lived in matrilineal clan units throughout the reservation, the size of West Virginia. The family traditional dwelling, called a “hogan,” often is clustered together. Multiple generations live together in these units. The COVID-19 virus inflicted many Navajo and rapidly spread to the elderly in these close-proximity living quarters.

Most Navajo live away from services and grocery stores and travel back and forth for food and water, which contributes to the virus rapidly being transmitted among the community members. Education aimed at curbing travel and spread of the virus was issued with curfews, commands to stay at home and keep social distance, and protect elders. The Navajo leadership and traditional medicine people, meanwhile, advised the people to follow their cultural values by caring for family and community members and providing a safe environment.

Resources are spread out

There are only 13 stores in this expansive reservation,4 so tribal members rely on traveling to border towns, such as Farmington and Gallup, N.M., Families usually travel to these towns on weekends to replenish food and supplies. There has been a cluster of cases in Gallup, N.M., so to reduce the numbers, the town shut itself off from outsiders – including the Navajo people coming to buy food, do laundry, and get water and feed for livestock. This has affected and stressed the Navajo further in attempting to access necessities.

Access to health care is already challenging because of lack of transportation and distance. This has made it more difficult to access COVID-19 testing and more challenging to get the results back. The Indian Health Service has been the designated health care system for the Navajo since 1955. The Treaty of Bosque Redondo, signed by the Navajo in 1868, included the provision of health care, as well as education in exchange for tracts of land, that included the Navajo homeland or Dinetah.5

The Indian Health Service provides care with hospitals and clinics throughout the reservation. Some of the IHS facilities have been taken over by the Navajo, so there are four Navajo tribally controlled hospitals, along with one private hospital. Coordination of care for a pandemic is, therefore, more challenging to coordinate. This contributes to problems with coordination of the health care, establishing alternate care sites, accessing personal protective equipment, and providing testing sites. The Navajo Nation Council is working hard to equitably distribute the $600 million from the CARES Act.6

Dealing with the pandemic is compromised by chronic underfunding from the U.S. government. The treaty obligation of the U.S. government is to provide health care to all federally recognized Native Americans. The IHS, which has been designated to provide that care for a tribal person, gets one-third the Medicare dollars for health care provided for a person in the general population.7 Health factors have led to the public health issues of poorly controlled diabetes, obesity, and coronary artery disease, which is related to this underfunding and the high rate of COVID-19 cases. Parts of the reservation are also exposed to high levels of pollution from oil and gas wells from the coal-fueled power plants. Those exposed to these high levels of pollutions have a higher than average number of cases of COVID-19, higher than in areas where the pollution is markedly lower.8

The Navajo are having to rely on the strength and resilience of traditional Navajo culture and philosophy to confront this monster, Dikos Nitsaa’igii’ 19. We have relied on Western medicine and its limited resources but now need to empower the strength from our traditional ways of knowing. We have used this knowledge in times of adversity for hundreds of years. The Navajo elders and medicine people have reminded us we have dealt with monsters and know how to endure hardship and be resilient. This helps to ameliorate mental health conditions, but there are still issues that remain challenging.

Those having the virus go through times of shortness of breath, which produces anxiety and panic. The risk of death adds further stress, and for a family-oriented culture, the need to isolate from family adds further stress. For the elderly and young people with more serious disease having to go to the hospital alone without family, often far from home, is so challenging. Connecting family by phone or social media with those stricken is essential to decrease anxiety and isolation. Those infected with the virus can learn breathing exercises, which can help the damage from the virus and decrease emotional activation and triggers. Specific breathing techniques can be taught by medical providers. An effective breathing technique to reduce anxiety is coherent breathing, which is done by inhaling 6 seconds and exhaling for 6 seconds without holding your breath. Behavioral health practitioners are available in the tribal and IHS mental health clinics to refer patients to therapy support to manage anxiety and are available by telemedicine. Many of these programs are offering social media informational sessions for the Navajo community. Navajo people often access traditional healing for protection prayers and ceremonies. Some of the tribal and IHS programs provide traditional counselors to talk to. The Navajo access healing that focuses on restoring balance to the body, mind, and spirit.

Taking action against the virus by social distancing, hand washing, and wearing masks can go a long way in reducing anxiety and fear about getting the virus. Resources to help the Navajo Nation are coming from all over the world, from as far as Ireland,9 Doctors Without Borders, 10 and University of San Francisco.11

Two resources that provide relief on the reservation are the Navajo Relief Fund and United Natives.

References

1. Navaho Times. 2020 May 27.

2. Ingalls A et al. BMC Obes. 2019 May 6. doi: 10.1186/s40608-019-0233-9.

3. U.S. Census 2010, as reported by discovernavajo.com.

4. Gould C et al. “Addressing food insecurity on the Navajo reservation through sustainable greenhouses.” 2018 Aug.

5. Native Knowledge 360. Smithsonian Institution. “Bosque Redondo.”

6. Personal communication, Carl Roessel Slater, Navajo Nation Council delegate.

7. IHS Profile Fact Sheet.

8. Wu X et al. medRxiv. 2020 Apr 27.

9. Carroll R. ”Irish support for Native American COVID-19 relief highlights historic bond.” The Guardian. 2020 May 9.

10. Capatides C. “Doctors Without Borders dispatches team to the Navajo Nation” CBS News. 2020 May 11.

11. Weiler N. “UCSF sends second wave of health workers to Navajo Nation.” UCSF.edu. 2020 May 21.

Dr. Roessel is a Navajo board-certified psychiatrist practicing in Santa Fe, N.M., working with the local indigenous population. She has special expertise in cultural psychiatry; her childhood was spent growing up in the Navajo Nation with her grandfather, who was a Navajo medicine man. Her psychiatric practice focuses on integrating indigenous knowledge and principles. Dr. Roessel is a distinguished fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. She has no disclosures.

The Navajo people have dealt with adversity that has tested our strength and resilience since our creation. In Navajo culture, the Holy People or gods challenged us with Naayee (monsters). We endured and learned from each Naayee, hunger, and death to name a few adversities. The COVID-19 pandemic, or “Big Cough” (Dikos Nitsaa’igii -19 in Navajo language) is a monster confronting the Navajo today. It has had significant impact on our nation and people.

The Navajo have the most cases of the COVID-19 virus of any tribe in the United States, and numbers as of May 31, 2020, are 5,348, with 246 confirmed deaths.1 The Navajo Nation, which once lagged behind New York, has reported the largest per-capita infection rate in the United States.

These devastating numbers, which might be leveling off, are associated with Navajo people having higher-than-average numbers of diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. This is compounded with 30%-40% of homes having no electricity or running water, and a poverty rate of about 38%.2

Geographical and cultural factors also contribute to the inability to gain a foothold in mitigating the number of cases. The Navajo Nation is the largest tribe in the United States, covering 27,000 square miles over an arid, red rock expanse with canyons and mountains. The population is over 250,000,3 and Navajo have traditionally lived in matrilineal clan units throughout the reservation, the size of West Virginia. The family traditional dwelling, called a “hogan,” often is clustered together. Multiple generations live together in these units. The COVID-19 virus inflicted many Navajo and rapidly spread to the elderly in these close-proximity living quarters.

Most Navajo live away from services and grocery stores and travel back and forth for food and water, which contributes to the virus rapidly being transmitted among the community members. Education aimed at curbing travel and spread of the virus was issued with curfews, commands to stay at home and keep social distance, and protect elders. The Navajo leadership and traditional medicine people, meanwhile, advised the people to follow their cultural values by caring for family and community members and providing a safe environment.

Resources are spread out

There are only 13 stores in this expansive reservation,4 so tribal members rely on traveling to border towns, such as Farmington and Gallup, N.M., Families usually travel to these towns on weekends to replenish food and supplies. There has been a cluster of cases in Gallup, N.M., so to reduce the numbers, the town shut itself off from outsiders – including the Navajo people coming to buy food, do laundry, and get water and feed for livestock. This has affected and stressed the Navajo further in attempting to access necessities.

Access to health care is already challenging because of lack of transportation and distance. This has made it more difficult to access COVID-19 testing and more challenging to get the results back. The Indian Health Service has been the designated health care system for the Navajo since 1955. The Treaty of Bosque Redondo, signed by the Navajo in 1868, included the provision of health care, as well as education in exchange for tracts of land, that included the Navajo homeland or Dinetah.5

The Indian Health Service provides care with hospitals and clinics throughout the reservation. Some of the IHS facilities have been taken over by the Navajo, so there are four Navajo tribally controlled hospitals, along with one private hospital. Coordination of care for a pandemic is, therefore, more challenging to coordinate. This contributes to problems with coordination of the health care, establishing alternate care sites, accessing personal protective equipment, and providing testing sites. The Navajo Nation Council is working hard to equitably distribute the $600 million from the CARES Act.6

Dealing with the pandemic is compromised by chronic underfunding from the U.S. government. The treaty obligation of the U.S. government is to provide health care to all federally recognized Native Americans. The IHS, which has been designated to provide that care for a tribal person, gets one-third the Medicare dollars for health care provided for a person in the general population.7 Health factors have led to the public health issues of poorly controlled diabetes, obesity, and coronary artery disease, which is related to this underfunding and the high rate of COVID-19 cases. Parts of the reservation are also exposed to high levels of pollution from oil and gas wells from the coal-fueled power plants. Those exposed to these high levels of pollutions have a higher than average number of cases of COVID-19, higher than in areas where the pollution is markedly lower.8

The Navajo are having to rely on the strength and resilience of traditional Navajo culture and philosophy to confront this monster, Dikos Nitsaa’igii’ 19. We have relied on Western medicine and its limited resources but now need to empower the strength from our traditional ways of knowing. We have used this knowledge in times of adversity for hundreds of years. The Navajo elders and medicine people have reminded us we have dealt with monsters and know how to endure hardship and be resilient. This helps to ameliorate mental health conditions, but there are still issues that remain challenging.

Those having the virus go through times of shortness of breath, which produces anxiety and panic. The risk of death adds further stress, and for a family-oriented culture, the need to isolate from family adds further stress. For the elderly and young people with more serious disease having to go to the hospital alone without family, often far from home, is so challenging. Connecting family by phone or social media with those stricken is essential to decrease anxiety and isolation. Those infected with the virus can learn breathing exercises, which can help the damage from the virus and decrease emotional activation and triggers. Specific breathing techniques can be taught by medical providers. An effective breathing technique to reduce anxiety is coherent breathing, which is done by inhaling 6 seconds and exhaling for 6 seconds without holding your breath. Behavioral health practitioners are available in the tribal and IHS mental health clinics to refer patients to therapy support to manage anxiety and are available by telemedicine. Many of these programs are offering social media informational sessions for the Navajo community. Navajo people often access traditional healing for protection prayers and ceremonies. Some of the tribal and IHS programs provide traditional counselors to talk to. The Navajo access healing that focuses on restoring balance to the body, mind, and spirit.

Taking action against the virus by social distancing, hand washing, and wearing masks can go a long way in reducing anxiety and fear about getting the virus. Resources to help the Navajo Nation are coming from all over the world, from as far as Ireland,9 Doctors Without Borders, 10 and University of San Francisco.11

Two resources that provide relief on the reservation are the Navajo Relief Fund and United Natives.

References

1. Navaho Times. 2020 May 27.

2. Ingalls A et al. BMC Obes. 2019 May 6. doi: 10.1186/s40608-019-0233-9.

3. U.S. Census 2010, as reported by discovernavajo.com.

4. Gould C et al. “Addressing food insecurity on the Navajo reservation through sustainable greenhouses.” 2018 Aug.

5. Native Knowledge 360. Smithsonian Institution. “Bosque Redondo.”

6. Personal communication, Carl Roessel Slater, Navajo Nation Council delegate.

7. IHS Profile Fact Sheet.

8. Wu X et al. medRxiv. 2020 Apr 27.

9. Carroll R. ”Irish support for Native American COVID-19 relief highlights historic bond.” The Guardian. 2020 May 9.

10. Capatides C. “Doctors Without Borders dispatches team to the Navajo Nation” CBS News. 2020 May 11.

11. Weiler N. “UCSF sends second wave of health workers to Navajo Nation.” UCSF.edu. 2020 May 21.

Dr. Roessel is a Navajo board-certified psychiatrist practicing in Santa Fe, N.M., working with the local indigenous population. She has special expertise in cultural psychiatry; her childhood was spent growing up in the Navajo Nation with her grandfather, who was a Navajo medicine man. Her psychiatric practice focuses on integrating indigenous knowledge and principles. Dr. Roessel is a distinguished fellow of the American Psychiatric Association. She has no disclosures.

The Navajo people have dealt with adversity that has tested our strength and resilience since our creation. In Navajo culture, the Holy People or gods challenged us with Naayee (monsters). We endured and learned from each Naayee, hunger, and death to name a few adversities. The COVID-19 pandemic, or “Big Cough” (Dikos Nitsaa’igii -19 in Navajo language) is a monster confronting the Navajo today. It has had significant impact on our nation and people.

The Navajo have the most cases of the COVID-19 virus of any tribe in the United States, and numbers as of May 31, 2020, are 5,348, with 246 confirmed deaths.1 The Navajo Nation, which once lagged behind New York, has reported the largest per-capita infection rate in the United States.

These devastating numbers, which might be leveling off, are associated with Navajo people having higher-than-average numbers of diabetes, heart disease, and cancer. This is compounded with 30%-40% of homes having no electricity or running water, and a poverty rate of about 38%.2

Geographical and cultural factors also contribute to the inability to gain a foothold in mitigating the number of cases. The Navajo Nation is the largest tribe in the United States, covering 27,000 square miles over an arid, red rock expanse with canyons and mountains. The population is over 250,000,3 and Navajo have traditionally lived in matrilineal clan units throughout the reservation, the size of West Virginia. The family traditional dwelling, called a “hogan,” often is clustered together. Multiple generations live together in these units. The COVID-19 virus inflicted many Navajo and rapidly spread to the elderly in these close-proximity living quarters.

Most Navajo live away from services and grocery stores and travel back and forth for food and water, which contributes to the virus rapidly being transmitted among the community members. Education aimed at curbing travel and spread of the virus was issued with curfews, commands to stay at home and keep social distance, and protect elders. The Navajo leadership and traditional medicine people, meanwhile, advised the people to follow their cultural values by caring for family and community members and providing a safe environment.

Resources are spread out

There are only 13 stores in this expansive reservation,4 so tribal members rely on traveling to border towns, such as Farmington and Gallup, N.M., Families usually travel to these towns on weekends to replenish food and supplies. There has been a cluster of cases in Gallup, N.M., so to reduce the numbers, the town shut itself off from outsiders – including the Navajo people coming to buy food, do laundry, and get water and feed for livestock. This has affected and stressed the Navajo further in attempting to access necessities.