User login

Accused: Doc increases patient’s penis size with improper fillers; more

, as reported in NJ.com.

The physician, Muhammad A. Mirza, MD, is a board-certified internal medicine doctor and owner of Mirza Aesthetics, which has its main New Jersey office in Cedar Grove, a township in Essex County. The practice also leases space in New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut, where at press time Dr. Mirza was still licensed to practice medicine.

The acting New Jersey attorney general said that Dr. Mirza had deviated from the accepted standards of medical care in at least four key areas: he practiced in ways that put his patients in bodily danger; he lacked the formal training in and an adequate knowledge of aesthetic medicine; he practiced in office settings that inspectors found to be subpar; and he failed to safely store medical supplies or maintain proper medical records.

In one instance singled out by the attorney general’s office, Dr. Mirza used an injectable dermal filler to enhance a patient’s penis. As a result of that nonsurgical procedure, the patient needed to be rushed to a nearby hospital, where he underwent two emergency surgical interventions. Contacted by the emergency department doctor, Dr. Mirza allegedly failed to disclose the name of the filler he used, thereby complicating the patient’s recovery, according to the board complaint.

Dr. Mirza’s other alleged breaches of professional conduct include the following:

- Failure to wear a mask or surgical gloves during procedures

- Failure to keep electronic medical records of any kind

- Improper, off-label use of an injectable dermal filler in proximity to patients’ eyes

- Improper, off-label use of an injectable dermal filler for breast enhancement

- Use of a certain injectable dermal filler without first testing for skin allergies

In addition, site inspections of Dr. Mirza’s offices turned up substandard conditions. On April 23, 2021, in response to numerous patient complaints, the Enforcement Bureau of the Division of Consumer Affairs inspected Dr. Mirza’s Summit, N.J. office, one of several in the state.

Among other things, the inspection uncovered the following:

- The medical office was one large room. A curtain separated the reception area and the examination/treatment area, which consisted of only chairs and a fold-away table.

- “Duffle bags” were used to store injectable fillers. No medical storage refrigerators were observed.

- COVID-19 protocols were not followed. Inspectors could identify no barrier between receptionist and patients, no posted mask mandate, no social distancing policy, and no COVID-19 screening measures.

In addition to temporarily suspending Dr. Mirza’s license, the medical board has prohibited him from treating New Jersey patients in any of the out-of-state locations where he’s licensed to practice medicine.

Prosecutors have urged other patients who believe they’ve been injured by Mirza Aesthetics to file a complaint with the State Division of Consumer Affairs.

Dr. Mirza has agreed to the temporary suspension of his medical license, pending a hearing before an administrative law judge. In addition to facing civil penalties for each of the counts against him, he could be held responsible for paying investigative costs, attorney fees, trial costs, and other costs.

Doctor’s failure to diagnose results in mega award

In what is believed to be a record verdict in a wrongful death suit in Volusia County, Fla., a jury awarded $6.46 million to the family of a woman who died from an undiagnosed heart infection after being transferred from a local hospital, according to a report in The Daytona Beach News-Journal, among other news outlets.

In March 2016, Laura Staib went to what was then Florida Hospital DeLand — now AdventHealth DeLand — complaining of a variety of symptoms. There, she was examined by a doctor who was a member of a nearby cardiology group. His diagnosis: congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and sepsis. Transferred to a long-term care facility, Ms. Staib died 4 days later.

In their complaint against the cardiologist and his cardiology group, family members alleged that the doctor failed to identify Ms. Staib’s main problem: viral myocarditis.

“This was primarily a heart failure problem and a heart infection that was probably causing some problems in the lungs,” said the attorney representing the family. “A virus was attacking her heart, and they missed it,” he said. Claims against the hospital and other doctors were eventually resolved and dismissed.

The jury’s verdict will be appealed, said the attorney representing the cardiologist.

He argues that his client “did not cause that woman’s death. She died of an overwhelming lung infection...acute respiratory distress syndrome, caused by an overwhelming pneumonia that got worse after she was transferred to a facility where [my client] doesn’t practice.”

The bulk of the award will be in compensation for family members’ future pain and suffering and for other noneconomic damages.

Botched outpatient procedure leaves woman disfigured

In early September, a patient was allegedly administered the wrong drug during an outpatient procedure on her hand. She sued the Austin, Tex., hospital and surgical center where that procedure was performed, according to a story in Law/Street.

On January 9, 2020, Jessica Arguello went to HCA Healthcare’s South Austin Surgery Center to undergo a right-hand first metacarpophalangeal arthrodesis (fusion) and neuroma excision. In her suit against the hospital, Ms. Arguello claims that while her surgeon was preparing to close the incision after having irrigated the site, he called for a syringe containing an anesthetic. He was instead handed a syringe that contained formalin, the chemical used to preserve specimens for later review.

The mistake, Ms. Arguello claims, caused her to suffer massive chemical burns and necrosis of her flesh, which required four additional surgeries. In the end, she says, her right hand is disfigured and has limited mobility.

She adds that her injuries were preventable. Standard surgical procedure typically forbids chemicals such as formalin to be included among items on the prep tray. In addition to other compensation, she seeks damages for past and future medical expenses and past and future pain and suffering.

At press time, the defendants had not responded to Ms. Arguello’s complaint.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, as reported in NJ.com.

The physician, Muhammad A. Mirza, MD, is a board-certified internal medicine doctor and owner of Mirza Aesthetics, which has its main New Jersey office in Cedar Grove, a township in Essex County. The practice also leases space in New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut, where at press time Dr. Mirza was still licensed to practice medicine.

The acting New Jersey attorney general said that Dr. Mirza had deviated from the accepted standards of medical care in at least four key areas: he practiced in ways that put his patients in bodily danger; he lacked the formal training in and an adequate knowledge of aesthetic medicine; he practiced in office settings that inspectors found to be subpar; and he failed to safely store medical supplies or maintain proper medical records.

In one instance singled out by the attorney general’s office, Dr. Mirza used an injectable dermal filler to enhance a patient’s penis. As a result of that nonsurgical procedure, the patient needed to be rushed to a nearby hospital, where he underwent two emergency surgical interventions. Contacted by the emergency department doctor, Dr. Mirza allegedly failed to disclose the name of the filler he used, thereby complicating the patient’s recovery, according to the board complaint.

Dr. Mirza’s other alleged breaches of professional conduct include the following:

- Failure to wear a mask or surgical gloves during procedures

- Failure to keep electronic medical records of any kind

- Improper, off-label use of an injectable dermal filler in proximity to patients’ eyes

- Improper, off-label use of an injectable dermal filler for breast enhancement

- Use of a certain injectable dermal filler without first testing for skin allergies

In addition, site inspections of Dr. Mirza’s offices turned up substandard conditions. On April 23, 2021, in response to numerous patient complaints, the Enforcement Bureau of the Division of Consumer Affairs inspected Dr. Mirza’s Summit, N.J. office, one of several in the state.

Among other things, the inspection uncovered the following:

- The medical office was one large room. A curtain separated the reception area and the examination/treatment area, which consisted of only chairs and a fold-away table.

- “Duffle bags” were used to store injectable fillers. No medical storage refrigerators were observed.

- COVID-19 protocols were not followed. Inspectors could identify no barrier between receptionist and patients, no posted mask mandate, no social distancing policy, and no COVID-19 screening measures.

In addition to temporarily suspending Dr. Mirza’s license, the medical board has prohibited him from treating New Jersey patients in any of the out-of-state locations where he’s licensed to practice medicine.

Prosecutors have urged other patients who believe they’ve been injured by Mirza Aesthetics to file a complaint with the State Division of Consumer Affairs.

Dr. Mirza has agreed to the temporary suspension of his medical license, pending a hearing before an administrative law judge. In addition to facing civil penalties for each of the counts against him, he could be held responsible for paying investigative costs, attorney fees, trial costs, and other costs.

Doctor’s failure to diagnose results in mega award

In what is believed to be a record verdict in a wrongful death suit in Volusia County, Fla., a jury awarded $6.46 million to the family of a woman who died from an undiagnosed heart infection after being transferred from a local hospital, according to a report in The Daytona Beach News-Journal, among other news outlets.

In March 2016, Laura Staib went to what was then Florida Hospital DeLand — now AdventHealth DeLand — complaining of a variety of symptoms. There, she was examined by a doctor who was a member of a nearby cardiology group. His diagnosis: congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and sepsis. Transferred to a long-term care facility, Ms. Staib died 4 days later.

In their complaint against the cardiologist and his cardiology group, family members alleged that the doctor failed to identify Ms. Staib’s main problem: viral myocarditis.

“This was primarily a heart failure problem and a heart infection that was probably causing some problems in the lungs,” said the attorney representing the family. “A virus was attacking her heart, and they missed it,” he said. Claims against the hospital and other doctors were eventually resolved and dismissed.

The jury’s verdict will be appealed, said the attorney representing the cardiologist.

He argues that his client “did not cause that woman’s death. She died of an overwhelming lung infection...acute respiratory distress syndrome, caused by an overwhelming pneumonia that got worse after she was transferred to a facility where [my client] doesn’t practice.”

The bulk of the award will be in compensation for family members’ future pain and suffering and for other noneconomic damages.

Botched outpatient procedure leaves woman disfigured

In early September, a patient was allegedly administered the wrong drug during an outpatient procedure on her hand. She sued the Austin, Tex., hospital and surgical center where that procedure was performed, according to a story in Law/Street.

On January 9, 2020, Jessica Arguello went to HCA Healthcare’s South Austin Surgery Center to undergo a right-hand first metacarpophalangeal arthrodesis (fusion) and neuroma excision. In her suit against the hospital, Ms. Arguello claims that while her surgeon was preparing to close the incision after having irrigated the site, he called for a syringe containing an anesthetic. He was instead handed a syringe that contained formalin, the chemical used to preserve specimens for later review.

The mistake, Ms. Arguello claims, caused her to suffer massive chemical burns and necrosis of her flesh, which required four additional surgeries. In the end, she says, her right hand is disfigured and has limited mobility.

She adds that her injuries were preventable. Standard surgical procedure typically forbids chemicals such as formalin to be included among items on the prep tray. In addition to other compensation, she seeks damages for past and future medical expenses and past and future pain and suffering.

At press time, the defendants had not responded to Ms. Arguello’s complaint.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

, as reported in NJ.com.

The physician, Muhammad A. Mirza, MD, is a board-certified internal medicine doctor and owner of Mirza Aesthetics, which has its main New Jersey office in Cedar Grove, a township in Essex County. The practice also leases space in New York, Pennsylvania, and Connecticut, where at press time Dr. Mirza was still licensed to practice medicine.

The acting New Jersey attorney general said that Dr. Mirza had deviated from the accepted standards of medical care in at least four key areas: he practiced in ways that put his patients in bodily danger; he lacked the formal training in and an adequate knowledge of aesthetic medicine; he practiced in office settings that inspectors found to be subpar; and he failed to safely store medical supplies or maintain proper medical records.

In one instance singled out by the attorney general’s office, Dr. Mirza used an injectable dermal filler to enhance a patient’s penis. As a result of that nonsurgical procedure, the patient needed to be rushed to a nearby hospital, where he underwent two emergency surgical interventions. Contacted by the emergency department doctor, Dr. Mirza allegedly failed to disclose the name of the filler he used, thereby complicating the patient’s recovery, according to the board complaint.

Dr. Mirza’s other alleged breaches of professional conduct include the following:

- Failure to wear a mask or surgical gloves during procedures

- Failure to keep electronic medical records of any kind

- Improper, off-label use of an injectable dermal filler in proximity to patients’ eyes

- Improper, off-label use of an injectable dermal filler for breast enhancement

- Use of a certain injectable dermal filler without first testing for skin allergies

In addition, site inspections of Dr. Mirza’s offices turned up substandard conditions. On April 23, 2021, in response to numerous patient complaints, the Enforcement Bureau of the Division of Consumer Affairs inspected Dr. Mirza’s Summit, N.J. office, one of several in the state.

Among other things, the inspection uncovered the following:

- The medical office was one large room. A curtain separated the reception area and the examination/treatment area, which consisted of only chairs and a fold-away table.

- “Duffle bags” were used to store injectable fillers. No medical storage refrigerators were observed.

- COVID-19 protocols were not followed. Inspectors could identify no barrier between receptionist and patients, no posted mask mandate, no social distancing policy, and no COVID-19 screening measures.

In addition to temporarily suspending Dr. Mirza’s license, the medical board has prohibited him from treating New Jersey patients in any of the out-of-state locations where he’s licensed to practice medicine.

Prosecutors have urged other patients who believe they’ve been injured by Mirza Aesthetics to file a complaint with the State Division of Consumer Affairs.

Dr. Mirza has agreed to the temporary suspension of his medical license, pending a hearing before an administrative law judge. In addition to facing civil penalties for each of the counts against him, he could be held responsible for paying investigative costs, attorney fees, trial costs, and other costs.

Doctor’s failure to diagnose results in mega award

In what is believed to be a record verdict in a wrongful death suit in Volusia County, Fla., a jury awarded $6.46 million to the family of a woman who died from an undiagnosed heart infection after being transferred from a local hospital, according to a report in The Daytona Beach News-Journal, among other news outlets.

In March 2016, Laura Staib went to what was then Florida Hospital DeLand — now AdventHealth DeLand — complaining of a variety of symptoms. There, she was examined by a doctor who was a member of a nearby cardiology group. His diagnosis: congestive heart failure, pneumonia, and sepsis. Transferred to a long-term care facility, Ms. Staib died 4 days later.

In their complaint against the cardiologist and his cardiology group, family members alleged that the doctor failed to identify Ms. Staib’s main problem: viral myocarditis.

“This was primarily a heart failure problem and a heart infection that was probably causing some problems in the lungs,” said the attorney representing the family. “A virus was attacking her heart, and they missed it,” he said. Claims against the hospital and other doctors were eventually resolved and dismissed.

The jury’s verdict will be appealed, said the attorney representing the cardiologist.

He argues that his client “did not cause that woman’s death. She died of an overwhelming lung infection...acute respiratory distress syndrome, caused by an overwhelming pneumonia that got worse after she was transferred to a facility where [my client] doesn’t practice.”

The bulk of the award will be in compensation for family members’ future pain and suffering and for other noneconomic damages.

Botched outpatient procedure leaves woman disfigured

In early September, a patient was allegedly administered the wrong drug during an outpatient procedure on her hand. She sued the Austin, Tex., hospital and surgical center where that procedure was performed, according to a story in Law/Street.

On January 9, 2020, Jessica Arguello went to HCA Healthcare’s South Austin Surgery Center to undergo a right-hand first metacarpophalangeal arthrodesis (fusion) and neuroma excision. In her suit against the hospital, Ms. Arguello claims that while her surgeon was preparing to close the incision after having irrigated the site, he called for a syringe containing an anesthetic. He was instead handed a syringe that contained formalin, the chemical used to preserve specimens for later review.

The mistake, Ms. Arguello claims, caused her to suffer massive chemical burns and necrosis of her flesh, which required four additional surgeries. In the end, she says, her right hand is disfigured and has limited mobility.

She adds that her injuries were preventable. Standard surgical procedure typically forbids chemicals such as formalin to be included among items on the prep tray. In addition to other compensation, she seeks damages for past and future medical expenses and past and future pain and suffering.

At press time, the defendants had not responded to Ms. Arguello’s complaint.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

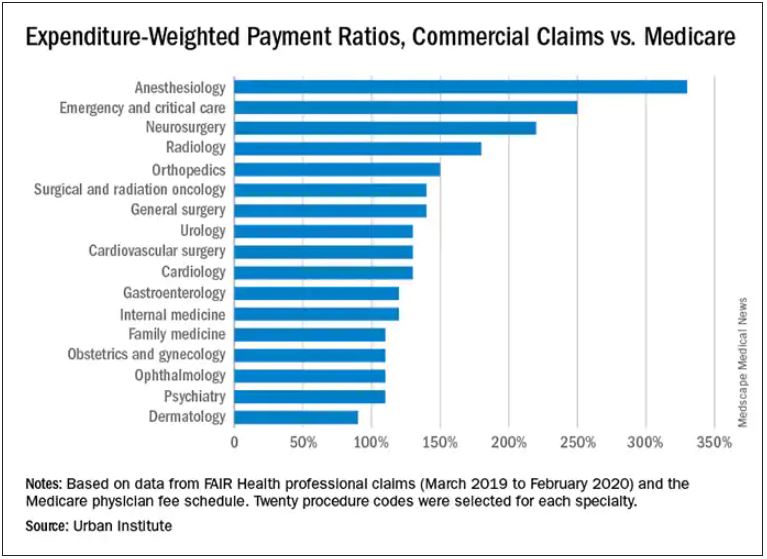

Which specialties get the biggest markups over Medicare rates?

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Anesthesiologists charge private insurers more than 300% above Medicare rates, a markup that is higher than that of 16 other specialties, according to a study released by the Urban Institute.

The Washington-based nonprofit institute found that the lowest markups were in psychiatry, ophthalmology, ob.gyn., family medicine, gastroenterology, and internal medicine, at 110%-120% of Medicare rates. .

In the middle are cardiology and cardiovascular surgery (130%), urology (130%), general surgery, surgical and radiation oncology (all at 140%), and orthopedics (150%).

At the top end were radiology (180%), neurosurgery (220%), emergency and critical care (250%), and anesthesiology (330%).

The wide variation in payments could be cited in support of the idea of applying Medicare rates across all physician specialties, say the study authors. Although lowering practitioner payments might lead to savings, it “will also create more pushback from providers, especially if these rates are introduced in the employer market,” write researchers Stacey McMorrow, PhD, Robert A. Berenson, MD, and John Holahan, PhD.

It is not known whether lowering commercial payment rates might decrease patient access, they write.

The authors also note that specialties in which the potential for a fee reduction was greatest were also the specialties for which baseline compensation was highest – from $350,000 annually for emergency physicians to $800,000 a year for neurosurgeons. Annual compensation for ob.gyns., dermatologists, and opthalmologists is about $350,000 a year, which suggests that “these specialties are similarly well compensated by both Medicare and commercial insurers,” the authors write.

The investigators assessed the top 20 procedure codes by expenditure in each of 17 physician specialties. They estimated the commercial-to-Medicare payment ratio for each service and constructed weighted averages across services for each specialty at the national level and for 12 states for which data for all the specialties and services were available.

The researchers analyzed claims from the FAIR Health database between March 2019 and March 2020. That database represents 60 insurers covering 150 million people.

Pediatric and geriatric specialties, nonphysician practitioners, out-of-network clinicians, and ambulatory surgery center claims were excluded. Codes with modifiers, J codes, and clinical laboratory services were also not included.

The charges used in the study were not the actual contracted rates. The authors instead used “imputed allowed amounts” for each claim line. That method was used to protect the confidentiality of the negotiated rates.

With regard to all specialties, the lowest compensated services were procedures, evaluation and management, and tests, which received 140%-150% of the Medicare rate. Treatments and imaging were marked up 160%. Anesthesia was reimbursed at a rate 330% higher than the rate Medicare would pay.

The authors also assessed geographic variation for the 12 states for which they had data.

Similar to findings in other studies, the researchers found that the markup was lowest in Pennsylvania (120%) and highest in Wisconsin (260%). The U.S. average was 160%. California and Missouri were at 150%; Michigan was right at the average.

For physicians in Illinois, Louisiana, Colorado, Texas, and New York, markups were 170%-180% over the Medicare rate. Markups for clinicians in New Jersey (190%) and Arizona (200%) were closest to the Wisconsin rate.

The authors note some study limitations, including the fact that they excluded out-of-network practitioners, “and such payments may disproportionately affect certain specialties.”

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Risk-based antenatal type-and-screen blood testing safe and economical

Implementing a selective type-and-screen blood testing policy in the labor and delivery unit was associated with projected annual savings of close to $200,000, a large single-center study found. Furthermore, there was no evidence of increased maternal morbidity in the university-based facility performing more than 4,400 deliveries per year, according to Ashley E. Benson, MD, MA, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and colleagues.

The study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, evaluated patient safety, resource utilization, and transfusion-related costs after a policy change from universal type and screen to selective, risk-based type and screen on admission to labor and delivery.

“There had been some national interest in moving toward decreased resource utilization, and findings that universal screening was not cost effective,” Dr. Benson, who has since relocated to Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. An earlier cost-effective modeling study at her center had suggested that universal test and screen was not cost effective and likely not safer either. “So based on that data we felt an implementation study was warranted.”

The switch to a selective policy was made in 2018, after which her group compared outcomes from October 2017 to September 2019, looking those both 1 year preimplementation and 1 year post implementation.

One year post implementation, the following outcomes emerged, compared with preimplementation:

- Overall projected saving of $181,000 a year in the maternity unit

- Lower mean monthly type- and screen-related costs, such as those for ABO typing, antibody screen, and antibody workup. cross-matches, hold clots, and transfused products: $9,753 vs. $20,676 in the preimplementation year (P < .001)

- A lower mean monthly cost of total transfusion preparedness: $25,090 vs. $39,211 (P < .001)

- No differences in emergency-release transfusion events (four vs. three, P = .99),the study’s primary safety outcome

- Fewer emergency-release red blood cell units transfused (9 vs. 24, P = .002) and O-negative RBC units transfused (8 vs. 18, P = .016)

- No differences in hysterectomies (0.05% vs. 0.1%, P = .44) and ICU admissions (0.45% vs. 0.51%, P = .43)

“In a year of selective type and screen, we saw a 51% reduction in costs related to type and screen, and a 38% reduction in overall transfusion-related costs,” the authors wrote. “This study supports other literature suggesting that more judicious use of type and screen may be safe and cost effective.”

Dr. Benson said the results were positively received when presented a meeting 2 years ago but the published version has yet to prompt feedback.

The study

Antepartum patients underwent transfusion preparedness tests according to the center’s standard antenatal admission order sets and were risk stratified in alignment with California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative recommendations. The mean maternal age of patients in both time periods was similar at just over 29 years and the mean gestational age at delivery was just under 38 weeks.

Under the new policy, a “hold clot” is obtained for women stratified as low or medium risk on admission. In this instance, a tube of patient blood is held in the blood bank but processed only if needed, as in the event of active hemorrhage or an order for transfusion. A blood cross-match is obtained on all women stratified as high risk or having a prior positive antibody screen.

Relevant costs were the direct costs of transfusion-related testing in the labor and delivery unit from a health system perspective.

Obstetric hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal death worldwide, the authors pointed out. While transfusion in obstetric patients occurs in only 1% or 2% of all deliveries it is nevertheless difficult to predict which patients will need transfusion, with only 2%-8% of those stratified as high risk ultimately requiring transfusion. Although obstetric hemorrhage safety bundles recommend risk stratification on admission to labor and delivery with selective type and screen for higher-risk individuals, for safety and simplicity’s sake, many labor and delivery units perform universal type and screen.

The authors cautioned that these results occurred in an academic tertiary care center with systems fine-tuned to deal with active hemorrhage and deliver timely transfusable blood. “At the moment we don’t have enough data to say whether the selective approach would be safe in hospitals with more limited blood bank capacity and access and fewer transfusion specialists in a setting optimized to respond to emergent needs, Dr. Benson said.

Katayoun F. M. Fomani, MD, a transfusion medicine specialist and medical director of blood bank and transfusion services at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New York, agreed. “This approach only works in a controlled environment such as in this study where eligible women were assessed antenatally at the same center, but it would not work at every institution,” she said in an interview. “In addition, all patients were assessed according to the California Collaborative guideline, which itself increases the safety level but is not followed everywhere.”

The obstetric division at her hospital in New York adheres to the universal type and screen. “We have patients coming in from outside whose antenatal testing was not done at our hospital,” she said. “For this selective approach to work you need a controlled population and the electronic resources and personnel to follow each patient carefully.”

The authors indicated no specific funding for this study and disclosed no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Fomani had no potential competing interests to declare.

Implementing a selective type-and-screen blood testing policy in the labor and delivery unit was associated with projected annual savings of close to $200,000, a large single-center study found. Furthermore, there was no evidence of increased maternal morbidity in the university-based facility performing more than 4,400 deliveries per year, according to Ashley E. Benson, MD, MA, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and colleagues.

The study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, evaluated patient safety, resource utilization, and transfusion-related costs after a policy change from universal type and screen to selective, risk-based type and screen on admission to labor and delivery.

“There had been some national interest in moving toward decreased resource utilization, and findings that universal screening was not cost effective,” Dr. Benson, who has since relocated to Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. An earlier cost-effective modeling study at her center had suggested that universal test and screen was not cost effective and likely not safer either. “So based on that data we felt an implementation study was warranted.”

The switch to a selective policy was made in 2018, after which her group compared outcomes from October 2017 to September 2019, looking those both 1 year preimplementation and 1 year post implementation.

One year post implementation, the following outcomes emerged, compared with preimplementation:

- Overall projected saving of $181,000 a year in the maternity unit

- Lower mean monthly type- and screen-related costs, such as those for ABO typing, antibody screen, and antibody workup. cross-matches, hold clots, and transfused products: $9,753 vs. $20,676 in the preimplementation year (P < .001)

- A lower mean monthly cost of total transfusion preparedness: $25,090 vs. $39,211 (P < .001)

- No differences in emergency-release transfusion events (four vs. three, P = .99),the study’s primary safety outcome

- Fewer emergency-release red blood cell units transfused (9 vs. 24, P = .002) and O-negative RBC units transfused (8 vs. 18, P = .016)

- No differences in hysterectomies (0.05% vs. 0.1%, P = .44) and ICU admissions (0.45% vs. 0.51%, P = .43)

“In a year of selective type and screen, we saw a 51% reduction in costs related to type and screen, and a 38% reduction in overall transfusion-related costs,” the authors wrote. “This study supports other literature suggesting that more judicious use of type and screen may be safe and cost effective.”

Dr. Benson said the results were positively received when presented a meeting 2 years ago but the published version has yet to prompt feedback.

The study

Antepartum patients underwent transfusion preparedness tests according to the center’s standard antenatal admission order sets and were risk stratified in alignment with California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative recommendations. The mean maternal age of patients in both time periods was similar at just over 29 years and the mean gestational age at delivery was just under 38 weeks.

Under the new policy, a “hold clot” is obtained for women stratified as low or medium risk on admission. In this instance, a tube of patient blood is held in the blood bank but processed only if needed, as in the event of active hemorrhage or an order for transfusion. A blood cross-match is obtained on all women stratified as high risk or having a prior positive antibody screen.

Relevant costs were the direct costs of transfusion-related testing in the labor and delivery unit from a health system perspective.

Obstetric hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal death worldwide, the authors pointed out. While transfusion in obstetric patients occurs in only 1% or 2% of all deliveries it is nevertheless difficult to predict which patients will need transfusion, with only 2%-8% of those stratified as high risk ultimately requiring transfusion. Although obstetric hemorrhage safety bundles recommend risk stratification on admission to labor and delivery with selective type and screen for higher-risk individuals, for safety and simplicity’s sake, many labor and delivery units perform universal type and screen.

The authors cautioned that these results occurred in an academic tertiary care center with systems fine-tuned to deal with active hemorrhage and deliver timely transfusable blood. “At the moment we don’t have enough data to say whether the selective approach would be safe in hospitals with more limited blood bank capacity and access and fewer transfusion specialists in a setting optimized to respond to emergent needs, Dr. Benson said.

Katayoun F. M. Fomani, MD, a transfusion medicine specialist and medical director of blood bank and transfusion services at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New York, agreed. “This approach only works in a controlled environment such as in this study where eligible women were assessed antenatally at the same center, but it would not work at every institution,” she said in an interview. “In addition, all patients were assessed according to the California Collaborative guideline, which itself increases the safety level but is not followed everywhere.”

The obstetric division at her hospital in New York adheres to the universal type and screen. “We have patients coming in from outside whose antenatal testing was not done at our hospital,” she said. “For this selective approach to work you need a controlled population and the electronic resources and personnel to follow each patient carefully.”

The authors indicated no specific funding for this study and disclosed no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Fomani had no potential competing interests to declare.

Implementing a selective type-and-screen blood testing policy in the labor and delivery unit was associated with projected annual savings of close to $200,000, a large single-center study found. Furthermore, there was no evidence of increased maternal morbidity in the university-based facility performing more than 4,400 deliveries per year, according to Ashley E. Benson, MD, MA, of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Utah, Salt Lake City, and colleagues.

The study, published in Obstetrics & Gynecology, evaluated patient safety, resource utilization, and transfusion-related costs after a policy change from universal type and screen to selective, risk-based type and screen on admission to labor and delivery.

“There had been some national interest in moving toward decreased resource utilization, and findings that universal screening was not cost effective,” Dr. Benson, who has since relocated to Oregon Health & Science University, Portland, said in an interview. An earlier cost-effective modeling study at her center had suggested that universal test and screen was not cost effective and likely not safer either. “So based on that data we felt an implementation study was warranted.”

The switch to a selective policy was made in 2018, after which her group compared outcomes from October 2017 to September 2019, looking those both 1 year preimplementation and 1 year post implementation.

One year post implementation, the following outcomes emerged, compared with preimplementation:

- Overall projected saving of $181,000 a year in the maternity unit

- Lower mean monthly type- and screen-related costs, such as those for ABO typing, antibody screen, and antibody workup. cross-matches, hold clots, and transfused products: $9,753 vs. $20,676 in the preimplementation year (P < .001)

- A lower mean monthly cost of total transfusion preparedness: $25,090 vs. $39,211 (P < .001)

- No differences in emergency-release transfusion events (four vs. three, P = .99),the study’s primary safety outcome

- Fewer emergency-release red blood cell units transfused (9 vs. 24, P = .002) and O-negative RBC units transfused (8 vs. 18, P = .016)

- No differences in hysterectomies (0.05% vs. 0.1%, P = .44) and ICU admissions (0.45% vs. 0.51%, P = .43)

“In a year of selective type and screen, we saw a 51% reduction in costs related to type and screen, and a 38% reduction in overall transfusion-related costs,” the authors wrote. “This study supports other literature suggesting that more judicious use of type and screen may be safe and cost effective.”

Dr. Benson said the results were positively received when presented a meeting 2 years ago but the published version has yet to prompt feedback.

The study

Antepartum patients underwent transfusion preparedness tests according to the center’s standard antenatal admission order sets and were risk stratified in alignment with California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative recommendations. The mean maternal age of patients in both time periods was similar at just over 29 years and the mean gestational age at delivery was just under 38 weeks.

Under the new policy, a “hold clot” is obtained for women stratified as low or medium risk on admission. In this instance, a tube of patient blood is held in the blood bank but processed only if needed, as in the event of active hemorrhage or an order for transfusion. A blood cross-match is obtained on all women stratified as high risk or having a prior positive antibody screen.

Relevant costs were the direct costs of transfusion-related testing in the labor and delivery unit from a health system perspective.

Obstetric hemorrhage is the leading cause of maternal death worldwide, the authors pointed out. While transfusion in obstetric patients occurs in only 1% or 2% of all deliveries it is nevertheless difficult to predict which patients will need transfusion, with only 2%-8% of those stratified as high risk ultimately requiring transfusion. Although obstetric hemorrhage safety bundles recommend risk stratification on admission to labor and delivery with selective type and screen for higher-risk individuals, for safety and simplicity’s sake, many labor and delivery units perform universal type and screen.

The authors cautioned that these results occurred in an academic tertiary care center with systems fine-tuned to deal with active hemorrhage and deliver timely transfusable blood. “At the moment we don’t have enough data to say whether the selective approach would be safe in hospitals with more limited blood bank capacity and access and fewer transfusion specialists in a setting optimized to respond to emergent needs, Dr. Benson said.

Katayoun F. M. Fomani, MD, a transfusion medicine specialist and medical director of blood bank and transfusion services at Long Island Jewish Medical Center, New York, agreed. “This approach only works in a controlled environment such as in this study where eligible women were assessed antenatally at the same center, but it would not work at every institution,” she said in an interview. “In addition, all patients were assessed according to the California Collaborative guideline, which itself increases the safety level but is not followed everywhere.”

The obstetric division at her hospital in New York adheres to the universal type and screen. “We have patients coming in from outside whose antenatal testing was not done at our hospital,” she said. “For this selective approach to work you need a controlled population and the electronic resources and personnel to follow each patient carefully.”

The authors indicated no specific funding for this study and disclosed no potential conflicts of interest. Dr. Fomani had no potential competing interests to declare.

FROM OBSTETRICS & GYNECOLOGY

The missing puzzle piece

Mrs. Stevens died last week. She was 87.

That’s nothing new. The nature of medicine is such that you’ll see patients pass on.

But Mrs. Stevens bothers me, because even to the end I’m not sure I ever had an answer.

Her case began with somewhat nebulous, but clearly neurological, symptoms. An initial workup was normal, as was the secondary one.

The third stage of increasingly esoteric tests turned up some clues as to what was going wrong, even as she continued to dwindle. I could at least start working on a differential, even if none of it was good.

I met with her and her husband, and they wanted an answer, good or bad.

I pulled some strings at a local tertiary subspecialty center and got her in. They agreed with my suspicions, though also couldn’t find something definitive. They even repeated the tests, and came to the same conclusions – narrowed down to a few things, but no smoking gun.

Throughout all of this Mrs. Stevens kept spiraling down. After a few hospital admissions and even a biopsy of an abdominal mass we thought would give us the answer, we still didn’t solve the puzzle.

At some point she and her husband grew tired of looking and accepted that it wouldn’t change anything. Her internist called hospice in. They kept her comfortable for her last few weeks.

They didn’t want an autopsy, so the secret stayed with her.

Looking back, I agree with their decision to stop the workup. When looking further won’t change anything, why bother?

But, as a doctor, it’s frustrating. There’s a degree of intellectual curiosity that drives us. We want answers. We want to solve puzzles.

And sometimes we never get that final piece. Even if it’s the right decision for the patient, at the end of the day it’s still an unsolved crime to us. A reminder that,

We probably never will.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Mrs. Stevens died last week. She was 87.

That’s nothing new. The nature of medicine is such that you’ll see patients pass on.

But Mrs. Stevens bothers me, because even to the end I’m not sure I ever had an answer.

Her case began with somewhat nebulous, but clearly neurological, symptoms. An initial workup was normal, as was the secondary one.

The third stage of increasingly esoteric tests turned up some clues as to what was going wrong, even as she continued to dwindle. I could at least start working on a differential, even if none of it was good.

I met with her and her husband, and they wanted an answer, good or bad.

I pulled some strings at a local tertiary subspecialty center and got her in. They agreed with my suspicions, though also couldn’t find something definitive. They even repeated the tests, and came to the same conclusions – narrowed down to a few things, but no smoking gun.

Throughout all of this Mrs. Stevens kept spiraling down. After a few hospital admissions and even a biopsy of an abdominal mass we thought would give us the answer, we still didn’t solve the puzzle.

At some point she and her husband grew tired of looking and accepted that it wouldn’t change anything. Her internist called hospice in. They kept her comfortable for her last few weeks.

They didn’t want an autopsy, so the secret stayed with her.

Looking back, I agree with their decision to stop the workup. When looking further won’t change anything, why bother?

But, as a doctor, it’s frustrating. There’s a degree of intellectual curiosity that drives us. We want answers. We want to solve puzzles.

And sometimes we never get that final piece. Even if it’s the right decision for the patient, at the end of the day it’s still an unsolved crime to us. A reminder that,

We probably never will.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Mrs. Stevens died last week. She was 87.

That’s nothing new. The nature of medicine is such that you’ll see patients pass on.

But Mrs. Stevens bothers me, because even to the end I’m not sure I ever had an answer.

Her case began with somewhat nebulous, but clearly neurological, symptoms. An initial workup was normal, as was the secondary one.

The third stage of increasingly esoteric tests turned up some clues as to what was going wrong, even as she continued to dwindle. I could at least start working on a differential, even if none of it was good.

I met with her and her husband, and they wanted an answer, good or bad.

I pulled some strings at a local tertiary subspecialty center and got her in. They agreed with my suspicions, though also couldn’t find something definitive. They even repeated the tests, and came to the same conclusions – narrowed down to a few things, but no smoking gun.

Throughout all of this Mrs. Stevens kept spiraling down. After a few hospital admissions and even a biopsy of an abdominal mass we thought would give us the answer, we still didn’t solve the puzzle.

At some point she and her husband grew tired of looking and accepted that it wouldn’t change anything. Her internist called hospice in. They kept her comfortable for her last few weeks.

They didn’t want an autopsy, so the secret stayed with her.

Looking back, I agree with their decision to stop the workup. When looking further won’t change anything, why bother?

But, as a doctor, it’s frustrating. There’s a degree of intellectual curiosity that drives us. We want answers. We want to solve puzzles.

And sometimes we never get that final piece. Even if it’s the right decision for the patient, at the end of the day it’s still an unsolved crime to us. A reminder that,

We probably never will.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Pandemic exacerbates primary care practices’ financial struggles

according to experts and the results of recent surveys by the Primary Care Collaborative (PCC).

Fewer than 30% (26.4%) of primary care clinicians report that their practices are financially healthy, according to the latest results from a periodic survey by the PCC. An earlier survey by the PCC suggests clinicians’ confidence in the financial viability of their practices has significantly declined since last year, when compared with the new survey’s results. When the older survey was taken between Sept. 4 and Sept. 8 of 2020, only 35% of primary care clinicians said that revenue and pay were significantly lower than they were before the pandemic.

Submissions to the new PCC survey were collected between Aug. 13 and Aug. 17 of 2021 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories. The PCC and the Larry A. Green Center have been regularly surveying primary care clinicians to better understand the impact of COVID-19 throughout the pandemic.

PCC President and CEO Ann Greiner said in an interview that the drop over a year follows a trend.

Though primary care faced struggles before the pandemic, the COVID-19 effect has been striking and cumulative, she noted.

“[Primary care practices] were healthier prepandemic,” said Ms. Greiner. “The precipitous drop in revenue when stay-at-home orders went into effect had a very big effect though pay structure and lack of investment in primary care was a problem long before COVID-19.”

COVID-19 has exacerbated all that ails primary care, and has increased fears of viability of primary care offices, she said.

Ms. Greiner pointed to a report from Health Affairs, that projected in 2020 that primary care would lose $65,000 in revenue per full-time physician by the end of the year for a total shortfall of $15 billion, following steep drops in office visits and fees for services from March to May, 2020.

In July of this year, she said, PCC’s survey found that, “Four in 10 clinicians worry that primary care will be gone in 5 years and one-fifth of respondents expect to leave the profession within the next three.”

The July PCC survey also showed that 13% of primary care clinicians said they have discussed selling their practice and cite high-level burnout/exhaustion as a main challenge for the next 6 months.

Robert L. Phillips, MD, a Virginia-based physician who oversees research for the American Board of Family Medicine, said, “Practices in our national primary care practice registry (PRIME) saw visit volumes drop 40% in the 2-3 months around the start of the pandemic and had not seen them return to normal as of June of this year. This means most remain financially underwater.”

End to paycheck protection hurt practices

Conrad L. Flick, MD, managing partner of Family Medical Associates in Raleigh, N.C., said the end of the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) at the end of 2020 caused further distress to primary care and could also help explain the drop in healthy practices that PCC’s survey from last year suggested.

“Many of us who struggled financially as the pandemic hit last year were really worried. PPP certainly shored that up for a lot of us. But now it’s no longer here,” he said.

Dr. Flick said his 10-clinician independent practice is financially sound and he credits that to having the PPP loan, shared savings from an accountable care organization, and holding some profit over from last year to this year.

His practice had to cut two nurse practitioners this year when volume did not return to prepandemic levels.

“The PPP loan let us keep [those NPs] employed through spring, but we were hoping the volume would come back. Come spring this year the volume hasn’t come back, and we couldn’t afford to keep the office at full staff,” he said.

The way primary care physicians are paid is what makes them so vulnerable in a pandemic, he explained.

“Our revenue is purely based on how many people I can get through my office at a given period of time. We don’t have ways to generate revenue and build a cushion.”

Family physician L. Allen Dobson, MD, said the survey results may have become even more grim in the last year, because primary care practices, especially small practices, have not recovered from the 2020 losses and effects have snowballed.

Even though primary care offices have largely reopened and many patients have returned to in-person visits, he said, physicians are dealing with uncertainties of COVID-19 surges and variants and are having trouble recruiting and maintaining staff.

Revenue that should have come to primary care practices in testing and distributing vaccines instead went elsewhere to larger vaccination sites and retail clinics, noted Dr. Dobson, who is chair of the board of managers of Community Care Physicians Network in Mount Pleasant, N.C., which provides assistance with administrative tasks to small and solo primary care practices.

COVID-19 brought ‘accelerated change’

COVID-19 brought “an accelerated change,” in decreasing revenue, Dr. Dobson said.

Small primary care practices have followed the rules of changing to electronic health records, getting patient-centered medical home certification, and documenting quality improvement measures, but they have not reaped the financial benefits from these changes, he explained.

A report commissioned by the Physician Advocacy Institute found that the pandemic accelerated a long national trend of hospitals and corporate entities acquiring physician practices and employing physicians.

From January 2019 to January 2021, these entities acquired 20,900 additional physician practices and 48,000 additional physicians left independent practice for employment by hospital systems or other corporate entities.

Further straining practices is a thinning workforce, with 21% or respondents to the most recent PCC survey having said they were unable to hire clinicians for open positions and 54% saying they are unable to hire staff for open positions.

One respondent to the PCC survey from Utah said, “We need more support. It’s a moral injury to have our pay cut and be severely understaffed. Most of the burden of educating patients and getting them vaccinated has fallen to primary care and we are already overwhelmed with taking care of patients with worsening mental and physical health.”

According to Bruce Landon, MD, MBA, professor of health care policy at the Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care, Boston, another source of financial strain for primary care practices is that they are having difficulty attracting doctors, nurses, and administrators.

These practices often need to increase pay for those positions to recruit people, and they are leaving many positions unfilled, Dr. Landon explained.

Plus, COVID-19 introduced costs for personal protective equipment (PPE) and cleaning products, and those expenses generally have not been reimbursed, Dr. Landon said.

Uncertainty around telemedicine

A new risk for primary care is a decline in telemedicine payments at a time when practices are still relying on telemedicine for revenue.

In the most recent PCC report, 40% of clinicians said they use telemedicine for at least a fifth of all office visits.

Even though most practices have reopened there’s still a fair amount of telemedicine and that will continue, Dr. Landon said in an interview.

In March of 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services lifted restrictions and that helped physicians with getting reimbursed for the services as they would office visits. But some commercial payers are starting to back off full payment for telemedicine, Dr. Landon noted.

“At some point the feds will probably start to do that with Medicare. I think that’s a mistake. [Telemedicine] has been one of the silver linings of this cloud of the pandemic,” he said.

If prepandemic payment regulations are restored, 41% of clinicians said, in the most recent PCC survey, that they worry their practices will no longer be able to support telemedicine.

Possible safety nets

Dr. Landon said that one thing that’s also clear is that some form of primary care capitation payment is necessary, at least for some of the work in primary care.

The practices that had capitation as part of payment were the ones who were most easily able to handle the pandemic because they didn’t see the immediate drop in revenue that fee-for-service practices saw, he noted.

“If we have a next pandemic, having a steady revenue stream to support primary care is really important and having a different way to pay for primary care is probably the best way to do that,” he said. “These longer-term strategies are going to be really crucial if we want to have a primary care system 10 years from now.”

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Flick, Dr. Phillips, Dr. Dobson, and Dr. Landon report no relevant financial relationships.

according to experts and the results of recent surveys by the Primary Care Collaborative (PCC).

Fewer than 30% (26.4%) of primary care clinicians report that their practices are financially healthy, according to the latest results from a periodic survey by the PCC. An earlier survey by the PCC suggests clinicians’ confidence in the financial viability of their practices has significantly declined since last year, when compared with the new survey’s results. When the older survey was taken between Sept. 4 and Sept. 8 of 2020, only 35% of primary care clinicians said that revenue and pay were significantly lower than they were before the pandemic.

Submissions to the new PCC survey were collected between Aug. 13 and Aug. 17 of 2021 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories. The PCC and the Larry A. Green Center have been regularly surveying primary care clinicians to better understand the impact of COVID-19 throughout the pandemic.

PCC President and CEO Ann Greiner said in an interview that the drop over a year follows a trend.

Though primary care faced struggles before the pandemic, the COVID-19 effect has been striking and cumulative, she noted.

“[Primary care practices] were healthier prepandemic,” said Ms. Greiner. “The precipitous drop in revenue when stay-at-home orders went into effect had a very big effect though pay structure and lack of investment in primary care was a problem long before COVID-19.”

COVID-19 has exacerbated all that ails primary care, and has increased fears of viability of primary care offices, she said.

Ms. Greiner pointed to a report from Health Affairs, that projected in 2020 that primary care would lose $65,000 in revenue per full-time physician by the end of the year for a total shortfall of $15 billion, following steep drops in office visits and fees for services from March to May, 2020.

In July of this year, she said, PCC’s survey found that, “Four in 10 clinicians worry that primary care will be gone in 5 years and one-fifth of respondents expect to leave the profession within the next three.”

The July PCC survey also showed that 13% of primary care clinicians said they have discussed selling their practice and cite high-level burnout/exhaustion as a main challenge for the next 6 months.

Robert L. Phillips, MD, a Virginia-based physician who oversees research for the American Board of Family Medicine, said, “Practices in our national primary care practice registry (PRIME) saw visit volumes drop 40% in the 2-3 months around the start of the pandemic and had not seen them return to normal as of June of this year. This means most remain financially underwater.”

End to paycheck protection hurt practices

Conrad L. Flick, MD, managing partner of Family Medical Associates in Raleigh, N.C., said the end of the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) at the end of 2020 caused further distress to primary care and could also help explain the drop in healthy practices that PCC’s survey from last year suggested.

“Many of us who struggled financially as the pandemic hit last year were really worried. PPP certainly shored that up for a lot of us. But now it’s no longer here,” he said.

Dr. Flick said his 10-clinician independent practice is financially sound and he credits that to having the PPP loan, shared savings from an accountable care organization, and holding some profit over from last year to this year.

His practice had to cut two nurse practitioners this year when volume did not return to prepandemic levels.

“The PPP loan let us keep [those NPs] employed through spring, but we were hoping the volume would come back. Come spring this year the volume hasn’t come back, and we couldn’t afford to keep the office at full staff,” he said.

The way primary care physicians are paid is what makes them so vulnerable in a pandemic, he explained.

“Our revenue is purely based on how many people I can get through my office at a given period of time. We don’t have ways to generate revenue and build a cushion.”

Family physician L. Allen Dobson, MD, said the survey results may have become even more grim in the last year, because primary care practices, especially small practices, have not recovered from the 2020 losses and effects have snowballed.

Even though primary care offices have largely reopened and many patients have returned to in-person visits, he said, physicians are dealing with uncertainties of COVID-19 surges and variants and are having trouble recruiting and maintaining staff.

Revenue that should have come to primary care practices in testing and distributing vaccines instead went elsewhere to larger vaccination sites and retail clinics, noted Dr. Dobson, who is chair of the board of managers of Community Care Physicians Network in Mount Pleasant, N.C., which provides assistance with administrative tasks to small and solo primary care practices.

COVID-19 brought ‘accelerated change’

COVID-19 brought “an accelerated change,” in decreasing revenue, Dr. Dobson said.

Small primary care practices have followed the rules of changing to electronic health records, getting patient-centered medical home certification, and documenting quality improvement measures, but they have not reaped the financial benefits from these changes, he explained.

A report commissioned by the Physician Advocacy Institute found that the pandemic accelerated a long national trend of hospitals and corporate entities acquiring physician practices and employing physicians.

From January 2019 to January 2021, these entities acquired 20,900 additional physician practices and 48,000 additional physicians left independent practice for employment by hospital systems or other corporate entities.

Further straining practices is a thinning workforce, with 21% or respondents to the most recent PCC survey having said they were unable to hire clinicians for open positions and 54% saying they are unable to hire staff for open positions.

One respondent to the PCC survey from Utah said, “We need more support. It’s a moral injury to have our pay cut and be severely understaffed. Most of the burden of educating patients and getting them vaccinated has fallen to primary care and we are already overwhelmed with taking care of patients with worsening mental and physical health.”

According to Bruce Landon, MD, MBA, professor of health care policy at the Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care, Boston, another source of financial strain for primary care practices is that they are having difficulty attracting doctors, nurses, and administrators.

These practices often need to increase pay for those positions to recruit people, and they are leaving many positions unfilled, Dr. Landon explained.

Plus, COVID-19 introduced costs for personal protective equipment (PPE) and cleaning products, and those expenses generally have not been reimbursed, Dr. Landon said.

Uncertainty around telemedicine

A new risk for primary care is a decline in telemedicine payments at a time when practices are still relying on telemedicine for revenue.

In the most recent PCC report, 40% of clinicians said they use telemedicine for at least a fifth of all office visits.

Even though most practices have reopened there’s still a fair amount of telemedicine and that will continue, Dr. Landon said in an interview.

In March of 2020, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services lifted restrictions and that helped physicians with getting reimbursed for the services as they would office visits. But some commercial payers are starting to back off full payment for telemedicine, Dr. Landon noted.

“At some point the feds will probably start to do that with Medicare. I think that’s a mistake. [Telemedicine] has been one of the silver linings of this cloud of the pandemic,” he said.

If prepandemic payment regulations are restored, 41% of clinicians said, in the most recent PCC survey, that they worry their practices will no longer be able to support telemedicine.

Possible safety nets

Dr. Landon said that one thing that’s also clear is that some form of primary care capitation payment is necessary, at least for some of the work in primary care.

The practices that had capitation as part of payment were the ones who were most easily able to handle the pandemic because they didn’t see the immediate drop in revenue that fee-for-service practices saw, he noted.

“If we have a next pandemic, having a steady revenue stream to support primary care is really important and having a different way to pay for primary care is probably the best way to do that,” he said. “These longer-term strategies are going to be really crucial if we want to have a primary care system 10 years from now.”

Ms. Greiner, Dr. Flick, Dr. Phillips, Dr. Dobson, and Dr. Landon report no relevant financial relationships.

according to experts and the results of recent surveys by the Primary Care Collaborative (PCC).

Fewer than 30% (26.4%) of primary care clinicians report that their practices are financially healthy, according to the latest results from a periodic survey by the PCC. An earlier survey by the PCC suggests clinicians’ confidence in the financial viability of their practices has significantly declined since last year, when compared with the new survey’s results. When the older survey was taken between Sept. 4 and Sept. 8 of 2020, only 35% of primary care clinicians said that revenue and pay were significantly lower than they were before the pandemic.

Submissions to the new PCC survey were collected between Aug. 13 and Aug. 17 of 2021 and included 1,263 respondents from 49 states, the District of Columbia, and two territories. The PCC and the Larry A. Green Center have been regularly surveying primary care clinicians to better understand the impact of COVID-19 throughout the pandemic.

PCC President and CEO Ann Greiner said in an interview that the drop over a year follows a trend.

Though primary care faced struggles before the pandemic, the COVID-19 effect has been striking and cumulative, she noted.

“[Primary care practices] were healthier prepandemic,” said Ms. Greiner. “The precipitous drop in revenue when stay-at-home orders went into effect had a very big effect though pay structure and lack of investment in primary care was a problem long before COVID-19.”

COVID-19 has exacerbated all that ails primary care, and has increased fears of viability of primary care offices, she said.

Ms. Greiner pointed to a report from Health Affairs, that projected in 2020 that primary care would lose $65,000 in revenue per full-time physician by the end of the year for a total shortfall of $15 billion, following steep drops in office visits and fees for services from March to May, 2020.

In July of this year, she said, PCC’s survey found that, “Four in 10 clinicians worry that primary care will be gone in 5 years and one-fifth of respondents expect to leave the profession within the next three.”

The July PCC survey also showed that 13% of primary care clinicians said they have discussed selling their practice and cite high-level burnout/exhaustion as a main challenge for the next 6 months.

Robert L. Phillips, MD, a Virginia-based physician who oversees research for the American Board of Family Medicine, said, “Practices in our national primary care practice registry (PRIME) saw visit volumes drop 40% in the 2-3 months around the start of the pandemic and had not seen them return to normal as of June of this year. This means most remain financially underwater.”

End to paycheck protection hurt practices

Conrad L. Flick, MD, managing partner of Family Medical Associates in Raleigh, N.C., said the end of the federal Paycheck Protection Program (PPP) at the end of 2020 caused further distress to primary care and could also help explain the drop in healthy practices that PCC’s survey from last year suggested.

“Many of us who struggled financially as the pandemic hit last year were really worried. PPP certainly shored that up for a lot of us. But now it’s no longer here,” he said.

Dr. Flick said his 10-clinician independent practice is financially sound and he credits that to having the PPP loan, shared savings from an accountable care organization, and holding some profit over from last year to this year.

His practice had to cut two nurse practitioners this year when volume did not return to prepandemic levels.

“The PPP loan let us keep [those NPs] employed through spring, but we were hoping the volume would come back. Come spring this year the volume hasn’t come back, and we couldn’t afford to keep the office at full staff,” he said.

The way primary care physicians are paid is what makes them so vulnerable in a pandemic, he explained.

“Our revenue is purely based on how many people I can get through my office at a given period of time. We don’t have ways to generate revenue and build a cushion.”

Family physician L. Allen Dobson, MD, said the survey results may have become even more grim in the last year, because primary care practices, especially small practices, have not recovered from the 2020 losses and effects have snowballed.

Even though primary care offices have largely reopened and many patients have returned to in-person visits, he said, physicians are dealing with uncertainties of COVID-19 surges and variants and are having trouble recruiting and maintaining staff.

Revenue that should have come to primary care practices in testing and distributing vaccines instead went elsewhere to larger vaccination sites and retail clinics, noted Dr. Dobson, who is chair of the board of managers of Community Care Physicians Network in Mount Pleasant, N.C., which provides assistance with administrative tasks to small and solo primary care practices.

COVID-19 brought ‘accelerated change’

COVID-19 brought “an accelerated change,” in decreasing revenue, Dr. Dobson said.

Small primary care practices have followed the rules of changing to electronic health records, getting patient-centered medical home certification, and documenting quality improvement measures, but they have not reaped the financial benefits from these changes, he explained.

A report commissioned by the Physician Advocacy Institute found that the pandemic accelerated a long national trend of hospitals and corporate entities acquiring physician practices and employing physicians.

From January 2019 to January 2021, these entities acquired 20,900 additional physician practices and 48,000 additional physicians left independent practice for employment by hospital systems or other corporate entities.

Further straining practices is a thinning workforce, with 21% or respondents to the most recent PCC survey having said they were unable to hire clinicians for open positions and 54% saying they are unable to hire staff for open positions.

One respondent to the PCC survey from Utah said, “We need more support. It’s a moral injury to have our pay cut and be severely understaffed. Most of the burden of educating patients and getting them vaccinated has fallen to primary care and we are already overwhelmed with taking care of patients with worsening mental and physical health.”

According to Bruce Landon, MD, MBA, professor of health care policy at the Harvard Medical School’s Center for Primary Care, Boston, another source of financial strain for primary care practices is that they are having difficulty attracting doctors, nurses, and administrators.