User login

FDA, FTC uniting to promote biosimilars

The Food and Drug Administration is collaborating with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand the biosimilars market.

The two agencies signed a joint statement on Feb. 3, 2020, outlining four sets of goals aimed at creating meaningful competition from biosimilars against their reference biologic products.

“Competition is key for helping American patients have access to affordable medicines,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “Strengthening efforts to curtail and discourage anticompetitive behavior is key for facilitating robust competition for patients in the biologics marketplace, including through biosimilars, bringing down the costs of these crucial products for patients.”

“We appreciate and applaud the FDA and FTC in recognizing that biosimilar development and approval has not been as robust as many stakeholders had hoped,” said Colin Edgerton, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care. “We continue to see anticompetitive activities that prevent manufacturers from developing biosimilar products. We hope that a greater focus on these practices will pave the way for more biosimilars to be developed.”

The statement highlighted four goals. First is that the agencies will coordinate to promote greater competition in the biologic market, including the development of materials to educate the market about biosimilars. The FDA and FTC also will be sponsoring a public workshop on March 9 to discuss competition for biologics.

“This workshop is the first step,” Dr. Edgerton said. “ACR will continue to work with other organizations and patient groups to help educate providers and patients on the scientific rigor that is required in developing and approving biosimilars. Additionally, we look forward to working with the FDA and FTC to continue this conversation on ways to encourage more development of biosimilar products and greater education for the providers and patients.”

The second goal has the FDA and FTC working together “to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for the development of biologics, including biosimilars,” the joint statement notes.

Third, the agencies will crack down on “false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars, within their respective authorities,” according to the joint statement.

“FDA and FTC, as authorized by their respective statutes, will work together to address false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars,” the statement continues. “In particular, if a communication makes a false or misleading comparison between a reference product and a biosimilar in a manner that misrepresents the safety or efficacy of biosimilars, deceives consumers, or deters competition, FDA and FTC intend to take appropriate action within their respective authorities. FDA intends to take appropriate action to address such communications where those communications have the potential to impact public health.”

Finally, the FTC committed to review patent settlement agreements involving biologics, including biosimilars, for antitrust violations.

Dr. Edgerton highlighted why this agreement between the two agencies is so important.

“Biologics are life-changing treatments for many of our patients,” he said. “Due to the high cost of discovery and development, the cost of biologics has resulted in delayed access and financial hardships for so many. It has always been our hope that biosimilars would offer the same life-changing treatment for patients at a lower price point. A robust biosimilars market is imperative to allow greater access to these treatments that can help patients to have a better quality of life.”

Separately, the FDA issued a draft guidance document for comment on manufacturers seeking licensure of biosimilar products that do not cover all the approved uses of the reference product, as well as how to add uses over time that were not part of the initial license of the biosimilar product. The draft guidance covers licensure of products, labeling of biosimilars with fewer indications than the reference product, supplemental applications for indications not on the initial biosimilar application but covered by the reference product, and the timing of applications.

The FDA notes in the draft guidance that this is needed to cover situations such as when some indications on the reference product are covered by exclusivity, although it does encourage a biosimilar manufacturer to seek licensure for all indications that the reference product does have.

The Food and Drug Administration is collaborating with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand the biosimilars market.

The two agencies signed a joint statement on Feb. 3, 2020, outlining four sets of goals aimed at creating meaningful competition from biosimilars against their reference biologic products.

“Competition is key for helping American patients have access to affordable medicines,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “Strengthening efforts to curtail and discourage anticompetitive behavior is key for facilitating robust competition for patients in the biologics marketplace, including through biosimilars, bringing down the costs of these crucial products for patients.”

“We appreciate and applaud the FDA and FTC in recognizing that biosimilar development and approval has not been as robust as many stakeholders had hoped,” said Colin Edgerton, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care. “We continue to see anticompetitive activities that prevent manufacturers from developing biosimilar products. We hope that a greater focus on these practices will pave the way for more biosimilars to be developed.”

The statement highlighted four goals. First is that the agencies will coordinate to promote greater competition in the biologic market, including the development of materials to educate the market about biosimilars. The FDA and FTC also will be sponsoring a public workshop on March 9 to discuss competition for biologics.

“This workshop is the first step,” Dr. Edgerton said. “ACR will continue to work with other organizations and patient groups to help educate providers and patients on the scientific rigor that is required in developing and approving biosimilars. Additionally, we look forward to working with the FDA and FTC to continue this conversation on ways to encourage more development of biosimilar products and greater education for the providers and patients.”

The second goal has the FDA and FTC working together “to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for the development of biologics, including biosimilars,” the joint statement notes.

Third, the agencies will crack down on “false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars, within their respective authorities,” according to the joint statement.

“FDA and FTC, as authorized by their respective statutes, will work together to address false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars,” the statement continues. “In particular, if a communication makes a false or misleading comparison between a reference product and a biosimilar in a manner that misrepresents the safety or efficacy of biosimilars, deceives consumers, or deters competition, FDA and FTC intend to take appropriate action within their respective authorities. FDA intends to take appropriate action to address such communications where those communications have the potential to impact public health.”

Finally, the FTC committed to review patent settlement agreements involving biologics, including biosimilars, for antitrust violations.

Dr. Edgerton highlighted why this agreement between the two agencies is so important.

“Biologics are life-changing treatments for many of our patients,” he said. “Due to the high cost of discovery and development, the cost of biologics has resulted in delayed access and financial hardships for so many. It has always been our hope that biosimilars would offer the same life-changing treatment for patients at a lower price point. A robust biosimilars market is imperative to allow greater access to these treatments that can help patients to have a better quality of life.”

Separately, the FDA issued a draft guidance document for comment on manufacturers seeking licensure of biosimilar products that do not cover all the approved uses of the reference product, as well as how to add uses over time that were not part of the initial license of the biosimilar product. The draft guidance covers licensure of products, labeling of biosimilars with fewer indications than the reference product, supplemental applications for indications not on the initial biosimilar application but covered by the reference product, and the timing of applications.

The FDA notes in the draft guidance that this is needed to cover situations such as when some indications on the reference product are covered by exclusivity, although it does encourage a biosimilar manufacturer to seek licensure for all indications that the reference product does have.

The Food and Drug Administration is collaborating with the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to expand the biosimilars market.

The two agencies signed a joint statement on Feb. 3, 2020, outlining four sets of goals aimed at creating meaningful competition from biosimilars against their reference biologic products.

“Competition is key for helping American patients have access to affordable medicines,” FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said in a statement. “Strengthening efforts to curtail and discourage anticompetitive behavior is key for facilitating robust competition for patients in the biologics marketplace, including through biosimilars, bringing down the costs of these crucial products for patients.”

“We appreciate and applaud the FDA and FTC in recognizing that biosimilar development and approval has not been as robust as many stakeholders had hoped,” said Colin Edgerton, MD, chair of the American College of Rheumatology’s Committee on Rheumatologic Care. “We continue to see anticompetitive activities that prevent manufacturers from developing biosimilar products. We hope that a greater focus on these practices will pave the way for more biosimilars to be developed.”

The statement highlighted four goals. First is that the agencies will coordinate to promote greater competition in the biologic market, including the development of materials to educate the market about biosimilars. The FDA and FTC also will be sponsoring a public workshop on March 9 to discuss competition for biologics.

“This workshop is the first step,” Dr. Edgerton said. “ACR will continue to work with other organizations and patient groups to help educate providers and patients on the scientific rigor that is required in developing and approving biosimilars. Additionally, we look forward to working with the FDA and FTC to continue this conversation on ways to encourage more development of biosimilar products and greater education for the providers and patients.”

The second goal has the FDA and FTC working together “to deter behavior that impedes access to samples needed for the development of biologics, including biosimilars,” the joint statement notes.

Third, the agencies will crack down on “false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars, within their respective authorities,” according to the joint statement.

“FDA and FTC, as authorized by their respective statutes, will work together to address false or misleading communications about biologics, including biosimilars,” the statement continues. “In particular, if a communication makes a false or misleading comparison between a reference product and a biosimilar in a manner that misrepresents the safety or efficacy of biosimilars, deceives consumers, or deters competition, FDA and FTC intend to take appropriate action within their respective authorities. FDA intends to take appropriate action to address such communications where those communications have the potential to impact public health.”

Finally, the FTC committed to review patent settlement agreements involving biologics, including biosimilars, for antitrust violations.

Dr. Edgerton highlighted why this agreement between the two agencies is so important.

“Biologics are life-changing treatments for many of our patients,” he said. “Due to the high cost of discovery and development, the cost of biologics has resulted in delayed access and financial hardships for so many. It has always been our hope that biosimilars would offer the same life-changing treatment for patients at a lower price point. A robust biosimilars market is imperative to allow greater access to these treatments that can help patients to have a better quality of life.”

Separately, the FDA issued a draft guidance document for comment on manufacturers seeking licensure of biosimilar products that do not cover all the approved uses of the reference product, as well as how to add uses over time that were not part of the initial license of the biosimilar product. The draft guidance covers licensure of products, labeling of biosimilars with fewer indications than the reference product, supplemental applications for indications not on the initial biosimilar application but covered by the reference product, and the timing of applications.

The FDA notes in the draft guidance that this is needed to cover situations such as when some indications on the reference product are covered by exclusivity, although it does encourage a biosimilar manufacturer to seek licensure for all indications that the reference product does have.

Medical malpractice insurance premiums likely to rise in 2020

For more than a decade, most physicians have paid a steady amount for medical liability insurance. But that price stability appears to be ending, according to a recent analysis.

In 2019, more than 25% of medical liability insurance premiums rose for internists, ob.gyns., and surgeons, a review by the Medical Liability Monitor (MLM) found. The MLM survey, published annually, analyzes premium data from major malpractice insurers based on mature, claims-made policies with $1 million/$3 million limits for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns.

The increases mark a shift in the long-stable market and suggest rising premiums in the future, said Michael Matray, editor for the Medical Liability Monitor.

“It’s my impression that rates will increase again in [2020]. It’s almost a foregone conclusion,” he said in an interview. “We can expect more firming within the market.”

Most of the premium increases in 2019 were small – between 0.1% and 10%, Mr. Matray said. At the same time, close to 70% of premium rates were flat in 2019 and about 5% of premium rates decreased, according to the survey, released in late 2019.

Comparatively, about 58% of premium rates were flat from 2007 to 2014, about 30% of rates went down during that time frame, and 12% of rates went up. From 2015 to 2018, nearly 76% of rates were steady, 10% went down, and 15% of rates increased, according to the latest analysis. 2019 was the first time since 2006 that more than 25% of premium rates rose, the survey noted.

“This is a normal cycle for the insurance industry – years of feast, followed by years of famine. Eventually companies reach a point where they feel enough pain and one response is to raise rates,” said Alyssa Gittleman, a coauthor of the survey and senior associate in the insurance research department at Conning, an investment management firm for the insurance industry.

“We could also point out many of the rate increases reported in the survey came from the larger [medical professional liability] companies. These companies are well capitalized, and the fact that they are raising rates could be a bellwether that a hard market is coming. However, as we said in the survey, it will probably take another 12-24 months before we know for certain,” she added.

Location, location, location

Physicians continue to pay vastly different premiums depending on where they practice. Ob.gyns. in eastern New York for example, paid about $201,000 in 2019, while their Minnesota colleagues paid about $16,500. Internists in southern Florida, meanwhile, paid about $49,000 in 2019, while their counterparts in northern California paid about $4,100. General surgeons in southern Florida paid about $195,000 for malpractice insurance, while some Wisconsin general surgeons paid about $11,000.

“Medical malpractice rates are determined locally, that’s why we don’t give state averages or national averages [in the survey],” Mr. Matray said. “It’s all determined by malpractice claims history within that territory and how aggressive the plaintiffs bar is in those areas.”

Two states – Arizona and Pennsylvania – experienced exceptional rate decreases in 2019. In Arizona, The Doctors Company lowered their rates by more than 60% for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns. In Pennsylvania, which operates a patient compensation fund, The Doctors Company decreased its rates between 20% and 46% for each of the three specialties. The insurer reported it made the decreases to align its rates with other insurers in those states, according to the survey. The Doctors Company did not respond to messages seeking comment for this article.

When individual companies greatly increase or greatly decrease rates in a given state, it’s generally to bring their rates in line with those of larger companies in the market, said Bill Burns, a coauthor of the MLM report and a vice president in the insurance research department at Conning. In 2018, The Doctors Company held about 2% of the market in Arizona, and the company held about 1% of the Pennsylvania market, he noted.

“These decreases, which get them in line with the larger writers, should tighten up the range of rates in those states,” Mr. Burns said in an interview. “To sell the product, they’re going to have be close to the competition.”

For a clear picture of the overall premium landscape, the survey authors analyzed the data both with and without the exceptional rate decreases in Arizona and Pennsylvania. Regionally – excluding the exceptional decreases – the average premium rate increase was 2% in the Midwest, 1.4% in the Northeast, 1.1% in the South, and 0.3% in the West.

For all three specialties surveyed, premiums rose slightly in 2019, with surgeons experiencing the largest increase. Internists saw a nearly 1% average rate increase, ob.gyns. experienced a 0.5% rise, and surgeons experienced a 2.3% rate increase, the survey found. For doctors in the seven states that have patient compensation funds, internists experienced a nearly 2.1% average rate increase, ob.gyns. saw a 1.4% rise, and surgeons experienced a 2.1% rate increase. (These data sets exclude the exceptional rate decreases in Arizona and Pennsylvania.)

The change in rates for general surgery could mean more claims are being filed against surgeons or that the cost of claims are rising, Mr. Burns said.

“The differences are not terribly significant, but suggest something is happening with general surgery,” he said.

Why are rates on the rise?

A number of factors are behind the changing medical liability insurance market, said Brian Atchinson, president and CEO for the Medical Professional Liability Association (MPL Association), a trade association for medical liability insurers.

While the frequency of claims against physicians has remained flat for an extended period of time, the cost of managing those claims has continued to increase, he said.

“Medical liability insurers insuring physicians and other clinicians, they need to defend every claim that they believe warrants defense,” Mr. Atchinson said in an interview. “When the medical treatment provided is within the appropriate standards, even though there may be claims or lawsuits, every one of those [cases] can be very expensive to defend.”

Other contributers to the increasing rates include the trend of high-dollar settlements and judgments, particularly in the hospital space, Mr. Atchinson noted. Such large payouts are generally tied to hospital and health system claims, but they still affect the broader medical liability insurance marketplace, he said.

Additionally, a growing number of medical liability tort reform measures enacted over the last 20 years are being eliminated, Mr. Atchinson said. In June 2019, the Kansas Supreme Court for instance, struck down the state’s cap on damages for noneconomic injuries in medical liability cases. In a 2017 ruling, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court changed the state’s statue of limitations for medical malpractice wrongful death claims from 2 years from the time of the patient’s injury to 2 years from the time of the patient’s death.

When legislatures change state laws and courts invalidate protections against nonmeritorious lawsuits, the actions can have serious consequences for physicians and companies operating in those states, Mr. Atchinson said.

“These [changes] will all ultimately work their way into the rates that physicians are paying,” he said.

For more than a decade, most physicians have paid a steady amount for medical liability insurance. But that price stability appears to be ending, according to a recent analysis.

In 2019, more than 25% of medical liability insurance premiums rose for internists, ob.gyns., and surgeons, a review by the Medical Liability Monitor (MLM) found. The MLM survey, published annually, analyzes premium data from major malpractice insurers based on mature, claims-made policies with $1 million/$3 million limits for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns.

The increases mark a shift in the long-stable market and suggest rising premiums in the future, said Michael Matray, editor for the Medical Liability Monitor.

“It’s my impression that rates will increase again in [2020]. It’s almost a foregone conclusion,” he said in an interview. “We can expect more firming within the market.”

Most of the premium increases in 2019 were small – between 0.1% and 10%, Mr. Matray said. At the same time, close to 70% of premium rates were flat in 2019 and about 5% of premium rates decreased, according to the survey, released in late 2019.

Comparatively, about 58% of premium rates were flat from 2007 to 2014, about 30% of rates went down during that time frame, and 12% of rates went up. From 2015 to 2018, nearly 76% of rates were steady, 10% went down, and 15% of rates increased, according to the latest analysis. 2019 was the first time since 2006 that more than 25% of premium rates rose, the survey noted.

“This is a normal cycle for the insurance industry – years of feast, followed by years of famine. Eventually companies reach a point where they feel enough pain and one response is to raise rates,” said Alyssa Gittleman, a coauthor of the survey and senior associate in the insurance research department at Conning, an investment management firm for the insurance industry.

“We could also point out many of the rate increases reported in the survey came from the larger [medical professional liability] companies. These companies are well capitalized, and the fact that they are raising rates could be a bellwether that a hard market is coming. However, as we said in the survey, it will probably take another 12-24 months before we know for certain,” she added.

Location, location, location

Physicians continue to pay vastly different premiums depending on where they practice. Ob.gyns. in eastern New York for example, paid about $201,000 in 2019, while their Minnesota colleagues paid about $16,500. Internists in southern Florida, meanwhile, paid about $49,000 in 2019, while their counterparts in northern California paid about $4,100. General surgeons in southern Florida paid about $195,000 for malpractice insurance, while some Wisconsin general surgeons paid about $11,000.

“Medical malpractice rates are determined locally, that’s why we don’t give state averages or national averages [in the survey],” Mr. Matray said. “It’s all determined by malpractice claims history within that territory and how aggressive the plaintiffs bar is in those areas.”

Two states – Arizona and Pennsylvania – experienced exceptional rate decreases in 2019. In Arizona, The Doctors Company lowered their rates by more than 60% for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns. In Pennsylvania, which operates a patient compensation fund, The Doctors Company decreased its rates between 20% and 46% for each of the three specialties. The insurer reported it made the decreases to align its rates with other insurers in those states, according to the survey. The Doctors Company did not respond to messages seeking comment for this article.

When individual companies greatly increase or greatly decrease rates in a given state, it’s generally to bring their rates in line with those of larger companies in the market, said Bill Burns, a coauthor of the MLM report and a vice president in the insurance research department at Conning. In 2018, The Doctors Company held about 2% of the market in Arizona, and the company held about 1% of the Pennsylvania market, he noted.

“These decreases, which get them in line with the larger writers, should tighten up the range of rates in those states,” Mr. Burns said in an interview. “To sell the product, they’re going to have be close to the competition.”

For a clear picture of the overall premium landscape, the survey authors analyzed the data both with and without the exceptional rate decreases in Arizona and Pennsylvania. Regionally – excluding the exceptional decreases – the average premium rate increase was 2% in the Midwest, 1.4% in the Northeast, 1.1% in the South, and 0.3% in the West.

For all three specialties surveyed, premiums rose slightly in 2019, with surgeons experiencing the largest increase. Internists saw a nearly 1% average rate increase, ob.gyns. experienced a 0.5% rise, and surgeons experienced a 2.3% rate increase, the survey found. For doctors in the seven states that have patient compensation funds, internists experienced a nearly 2.1% average rate increase, ob.gyns. saw a 1.4% rise, and surgeons experienced a 2.1% rate increase. (These data sets exclude the exceptional rate decreases in Arizona and Pennsylvania.)

The change in rates for general surgery could mean more claims are being filed against surgeons or that the cost of claims are rising, Mr. Burns said.

“The differences are not terribly significant, but suggest something is happening with general surgery,” he said.

Why are rates on the rise?

A number of factors are behind the changing medical liability insurance market, said Brian Atchinson, president and CEO for the Medical Professional Liability Association (MPL Association), a trade association for medical liability insurers.

While the frequency of claims against physicians has remained flat for an extended period of time, the cost of managing those claims has continued to increase, he said.

“Medical liability insurers insuring physicians and other clinicians, they need to defend every claim that they believe warrants defense,” Mr. Atchinson said in an interview. “When the medical treatment provided is within the appropriate standards, even though there may be claims or lawsuits, every one of those [cases] can be very expensive to defend.”

Other contributers to the increasing rates include the trend of high-dollar settlements and judgments, particularly in the hospital space, Mr. Atchinson noted. Such large payouts are generally tied to hospital and health system claims, but they still affect the broader medical liability insurance marketplace, he said.

Additionally, a growing number of medical liability tort reform measures enacted over the last 20 years are being eliminated, Mr. Atchinson said. In June 2019, the Kansas Supreme Court for instance, struck down the state’s cap on damages for noneconomic injuries in medical liability cases. In a 2017 ruling, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court changed the state’s statue of limitations for medical malpractice wrongful death claims from 2 years from the time of the patient’s injury to 2 years from the time of the patient’s death.

When legislatures change state laws and courts invalidate protections against nonmeritorious lawsuits, the actions can have serious consequences for physicians and companies operating in those states, Mr. Atchinson said.

“These [changes] will all ultimately work their way into the rates that physicians are paying,” he said.

For more than a decade, most physicians have paid a steady amount for medical liability insurance. But that price stability appears to be ending, according to a recent analysis.

In 2019, more than 25% of medical liability insurance premiums rose for internists, ob.gyns., and surgeons, a review by the Medical Liability Monitor (MLM) found. The MLM survey, published annually, analyzes premium data from major malpractice insurers based on mature, claims-made policies with $1 million/$3 million limits for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns.

The increases mark a shift in the long-stable market and suggest rising premiums in the future, said Michael Matray, editor for the Medical Liability Monitor.

“It’s my impression that rates will increase again in [2020]. It’s almost a foregone conclusion,” he said in an interview. “We can expect more firming within the market.”

Most of the premium increases in 2019 were small – between 0.1% and 10%, Mr. Matray said. At the same time, close to 70% of premium rates were flat in 2019 and about 5% of premium rates decreased, according to the survey, released in late 2019.

Comparatively, about 58% of premium rates were flat from 2007 to 2014, about 30% of rates went down during that time frame, and 12% of rates went up. From 2015 to 2018, nearly 76% of rates were steady, 10% went down, and 15% of rates increased, according to the latest analysis. 2019 was the first time since 2006 that more than 25% of premium rates rose, the survey noted.

“This is a normal cycle for the insurance industry – years of feast, followed by years of famine. Eventually companies reach a point where they feel enough pain and one response is to raise rates,” said Alyssa Gittleman, a coauthor of the survey and senior associate in the insurance research department at Conning, an investment management firm for the insurance industry.

“We could also point out many of the rate increases reported in the survey came from the larger [medical professional liability] companies. These companies are well capitalized, and the fact that they are raising rates could be a bellwether that a hard market is coming. However, as we said in the survey, it will probably take another 12-24 months before we know for certain,” she added.

Location, location, location

Physicians continue to pay vastly different premiums depending on where they practice. Ob.gyns. in eastern New York for example, paid about $201,000 in 2019, while their Minnesota colleagues paid about $16,500. Internists in southern Florida, meanwhile, paid about $49,000 in 2019, while their counterparts in northern California paid about $4,100. General surgeons in southern Florida paid about $195,000 for malpractice insurance, while some Wisconsin general surgeons paid about $11,000.

“Medical malpractice rates are determined locally, that’s why we don’t give state averages or national averages [in the survey],” Mr. Matray said. “It’s all determined by malpractice claims history within that territory and how aggressive the plaintiffs bar is in those areas.”

Two states – Arizona and Pennsylvania – experienced exceptional rate decreases in 2019. In Arizona, The Doctors Company lowered their rates by more than 60% for internists, general surgeons, and ob.gyns. In Pennsylvania, which operates a patient compensation fund, The Doctors Company decreased its rates between 20% and 46% for each of the three specialties. The insurer reported it made the decreases to align its rates with other insurers in those states, according to the survey. The Doctors Company did not respond to messages seeking comment for this article.

When individual companies greatly increase or greatly decrease rates in a given state, it’s generally to bring their rates in line with those of larger companies in the market, said Bill Burns, a coauthor of the MLM report and a vice president in the insurance research department at Conning. In 2018, The Doctors Company held about 2% of the market in Arizona, and the company held about 1% of the Pennsylvania market, he noted.

“These decreases, which get them in line with the larger writers, should tighten up the range of rates in those states,” Mr. Burns said in an interview. “To sell the product, they’re going to have be close to the competition.”

For a clear picture of the overall premium landscape, the survey authors analyzed the data both with and without the exceptional rate decreases in Arizona and Pennsylvania. Regionally – excluding the exceptional decreases – the average premium rate increase was 2% in the Midwest, 1.4% in the Northeast, 1.1% in the South, and 0.3% in the West.

For all three specialties surveyed, premiums rose slightly in 2019, with surgeons experiencing the largest increase. Internists saw a nearly 1% average rate increase, ob.gyns. experienced a 0.5% rise, and surgeons experienced a 2.3% rate increase, the survey found. For doctors in the seven states that have patient compensation funds, internists experienced a nearly 2.1% average rate increase, ob.gyns. saw a 1.4% rise, and surgeons experienced a 2.1% rate increase. (These data sets exclude the exceptional rate decreases in Arizona and Pennsylvania.)

The change in rates for general surgery could mean more claims are being filed against surgeons or that the cost of claims are rising, Mr. Burns said.

“The differences are not terribly significant, but suggest something is happening with general surgery,” he said.

Why are rates on the rise?

A number of factors are behind the changing medical liability insurance market, said Brian Atchinson, president and CEO for the Medical Professional Liability Association (MPL Association), a trade association for medical liability insurers.

While the frequency of claims against physicians has remained flat for an extended period of time, the cost of managing those claims has continued to increase, he said.

“Medical liability insurers insuring physicians and other clinicians, they need to defend every claim that they believe warrants defense,” Mr. Atchinson said in an interview. “When the medical treatment provided is within the appropriate standards, even though there may be claims or lawsuits, every one of those [cases] can be very expensive to defend.”

Other contributers to the increasing rates include the trend of high-dollar settlements and judgments, particularly in the hospital space, Mr. Atchinson noted. Such large payouts are generally tied to hospital and health system claims, but they still affect the broader medical liability insurance marketplace, he said.

Additionally, a growing number of medical liability tort reform measures enacted over the last 20 years are being eliminated, Mr. Atchinson said. In June 2019, the Kansas Supreme Court for instance, struck down the state’s cap on damages for noneconomic injuries in medical liability cases. In a 2017 ruling, the Pennsylvania Supreme Court changed the state’s statue of limitations for medical malpractice wrongful death claims from 2 years from the time of the patient’s injury to 2 years from the time of the patient’s death.

When legislatures change state laws and courts invalidate protections against nonmeritorious lawsuits, the actions can have serious consequences for physicians and companies operating in those states, Mr. Atchinson said.

“These [changes] will all ultimately work their way into the rates that physicians are paying,” he said.

Work happiness about average for ob.gyns.

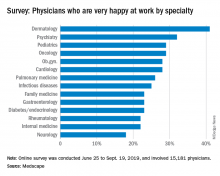

Ob.gyns. are in the middle of the pack when it comes to physician happiness both in and outside the office, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 28% of ob.gyns. reported that they were very happy at work, and 54% said that they were very happy outside of work, according to the Medscape report. Dermatologists were most likely to be happy at work at 41%, and rheumatologists were most likely to be happy outside of work at 60%.

The rate of burnout was higher in ob.gyns. than in physicians overall at 46% versus 41%; notably, 19% of all ob.gyns. reported being both burned out and depressed. The most commonly reported reasons for burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (57%), increased time devoted to EHRs (36%), and insufficient compensation/reimbursement (35%).

The most common ways ob.gyns. dealt with burnout was by isolating themselves from others (50%), exercising (49%), and talking with friends/family (44%). About 48% of ob.gyns. took 3-4 weeks of vacation, slightly more than the 44% average for all physicians; 32% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 15% of ob.gyns. have contemplated suicide, and 1% have attempted suicide; 80% have never contemplated suicide. Only 21% reported that they were currently seeking or planning to seek professional help for symptoms of burnout and/or depression, with 63% saying they would not consider and had not utilized professional help in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

This report definitely calls attention for improving both individual and organizational wellness. Historically, facing the challenges in medicine is something that we’ve come to expect as students and trainees. This normalized expectation – in addition to limited organizational support and potential lack of guaranteed privacy with regard to mental health concerns – explains the limited motivation to seek help. We knew about the long hours, bureaucracy, and pay inequity when we signed on. The main difference now is the greater emphasis on the value of addressing these issues on a greater scale.

Physicians who are well can have a greater capacity to be productive. It benefits organizations substantially when they employ physicians who are happy and continue to find meaning in their work.

This issue clearly is not unique to ob.gyns. It’s also hard to miss the irony of advocating for patient wellness without prioritizing our own. There’s a greater discrepancy with regard to burnout and gender because of the “second shift” that women tend to take on at home.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

This report definitely calls attention for improving both individual and organizational wellness. Historically, facing the challenges in medicine is something that we’ve come to expect as students and trainees. This normalized expectation – in addition to limited organizational support and potential lack of guaranteed privacy with regard to mental health concerns – explains the limited motivation to seek help. We knew about the long hours, bureaucracy, and pay inequity when we signed on. The main difference now is the greater emphasis on the value of addressing these issues on a greater scale.

Physicians who are well can have a greater capacity to be productive. It benefits organizations substantially when they employ physicians who are happy and continue to find meaning in their work.

This issue clearly is not unique to ob.gyns. It’s also hard to miss the irony of advocating for patient wellness without prioritizing our own. There’s a greater discrepancy with regard to burnout and gender because of the “second shift” that women tend to take on at home.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

This report definitely calls attention for improving both individual and organizational wellness. Historically, facing the challenges in medicine is something that we’ve come to expect as students and trainees. This normalized expectation – in addition to limited organizational support and potential lack of guaranteed privacy with regard to mental health concerns – explains the limited motivation to seek help. We knew about the long hours, bureaucracy, and pay inequity when we signed on. The main difference now is the greater emphasis on the value of addressing these issues on a greater scale.

Physicians who are well can have a greater capacity to be productive. It benefits organizations substantially when they employ physicians who are happy and continue to find meaning in their work.

This issue clearly is not unique to ob.gyns. It’s also hard to miss the irony of advocating for patient wellness without prioritizing our own. There’s a greater discrepancy with regard to burnout and gender because of the “second shift” that women tend to take on at home.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH, is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board.

Ob.gyns. are in the middle of the pack when it comes to physician happiness both in and outside the office, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 28% of ob.gyns. reported that they were very happy at work, and 54% said that they were very happy outside of work, according to the Medscape report. Dermatologists were most likely to be happy at work at 41%, and rheumatologists were most likely to be happy outside of work at 60%.

The rate of burnout was higher in ob.gyns. than in physicians overall at 46% versus 41%; notably, 19% of all ob.gyns. reported being both burned out and depressed. The most commonly reported reasons for burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (57%), increased time devoted to EHRs (36%), and insufficient compensation/reimbursement (35%).

The most common ways ob.gyns. dealt with burnout was by isolating themselves from others (50%), exercising (49%), and talking with friends/family (44%). About 48% of ob.gyns. took 3-4 weeks of vacation, slightly more than the 44% average for all physicians; 32% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 15% of ob.gyns. have contemplated suicide, and 1% have attempted suicide; 80% have never contemplated suicide. Only 21% reported that they were currently seeking or planning to seek professional help for symptoms of burnout and/or depression, with 63% saying they would not consider and had not utilized professional help in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Ob.gyns. are in the middle of the pack when it comes to physician happiness both in and outside the office, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 28% of ob.gyns. reported that they were very happy at work, and 54% said that they were very happy outside of work, according to the Medscape report. Dermatologists were most likely to be happy at work at 41%, and rheumatologists were most likely to be happy outside of work at 60%.

The rate of burnout was higher in ob.gyns. than in physicians overall at 46% versus 41%; notably, 19% of all ob.gyns. reported being both burned out and depressed. The most commonly reported reasons for burnout were too many bureaucratic tasks (57%), increased time devoted to EHRs (36%), and insufficient compensation/reimbursement (35%).

The most common ways ob.gyns. dealt with burnout was by isolating themselves from others (50%), exercising (49%), and talking with friends/family (44%). About 48% of ob.gyns. took 3-4 weeks of vacation, slightly more than the 44% average for all physicians; 32% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 15% of ob.gyns. have contemplated suicide, and 1% have attempted suicide; 80% have never contemplated suicide. Only 21% reported that they were currently seeking or planning to seek professional help for symptoms of burnout and/or depression, with 63% saying they would not consider and had not utilized professional help in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

ID physicians twice as happy outside work than at work

Infectious disease physicians are more than twice as likely to be happy outside of work than in the office, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 25% of infectious disease physicians reported that they were very happy in the office, compared with dermatologists, who had the highest rate of in-office happiness at 41%, according to the Medscape report. The out-of-office happiness rate rose to 52% for ID physicians, compared with the top spot of rheumatologists, who reported a 60% happiness rate.

The burnout rate for ID physicians was 46%, compared with 41% for physicians overall, with 12% of ID physicians reporting that they were both burned out and depressed. Having too many bureaucratic tasks was the most commonly reported reason for ID physician burnout at 49%, followed by a lack of respect from colleagues at 46% and spending too much time at work at 43%.

ID physicians most commonly dealt with burnout by talking with friends/family (49%), exercising (48%), and isolating themselves from others (43%). In addition, 52% of ID physicians reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians, with 33% of ID physicians saying that they took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 14% of ID physicians reported that they’d contemplated suicide, with 0% reporting that they’d attempted it; 80% reported that they’d never thought about it. About 54% said they weren’t considering seeking professional help for symptoms of burnout or depression, 13% said they’d used therapy in the past but weren’t currently looking, 7% said they were planning on seeking help, and 17% said they were currently seeking help.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Infectious disease physicians are more than twice as likely to be happy outside of work than in the office, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 25% of infectious disease physicians reported that they were very happy in the office, compared with dermatologists, who had the highest rate of in-office happiness at 41%, according to the Medscape report. The out-of-office happiness rate rose to 52% for ID physicians, compared with the top spot of rheumatologists, who reported a 60% happiness rate.

The burnout rate for ID physicians was 46%, compared with 41% for physicians overall, with 12% of ID physicians reporting that they were both burned out and depressed. Having too many bureaucratic tasks was the most commonly reported reason for ID physician burnout at 49%, followed by a lack of respect from colleagues at 46% and spending too much time at work at 43%.

ID physicians most commonly dealt with burnout by talking with friends/family (49%), exercising (48%), and isolating themselves from others (43%). In addition, 52% of ID physicians reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians, with 33% of ID physicians saying that they took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 14% of ID physicians reported that they’d contemplated suicide, with 0% reporting that they’d attempted it; 80% reported that they’d never thought about it. About 54% said they weren’t considering seeking professional help for symptoms of burnout or depression, 13% said they’d used therapy in the past but weren’t currently looking, 7% said they were planning on seeking help, and 17% said they were currently seeking help.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Infectious disease physicians are more than twice as likely to be happy outside of work than in the office, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 25% of infectious disease physicians reported that they were very happy in the office, compared with dermatologists, who had the highest rate of in-office happiness at 41%, according to the Medscape report. The out-of-office happiness rate rose to 52% for ID physicians, compared with the top spot of rheumatologists, who reported a 60% happiness rate.

The burnout rate for ID physicians was 46%, compared with 41% for physicians overall, with 12% of ID physicians reporting that they were both burned out and depressed. Having too many bureaucratic tasks was the most commonly reported reason for ID physician burnout at 49%, followed by a lack of respect from colleagues at 46% and spending too much time at work at 43%.

ID physicians most commonly dealt with burnout by talking with friends/family (49%), exercising (48%), and isolating themselves from others (43%). In addition, 52% of ID physicians reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians, with 33% of ID physicians saying that they took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 14% of ID physicians reported that they’d contemplated suicide, with 0% reporting that they’d attempted it; 80% reported that they’d never thought about it. About 54% said they weren’t considering seeking professional help for symptoms of burnout or depression, 13% said they’d used therapy in the past but weren’t currently looking, 7% said they were planning on seeking help, and 17% said they were currently seeking help.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

‘Momentous’ USMLE change: New pass/fail format stuns medicine

News that the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) program will change its Step 1 scoring from a 3-digit number to pass/fail starting Jan. 1, 2022, has set off a flurry of shocked responses from students and physicians.

J. Bryan Carmody, MD, MPH, an assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said in an interview that he was “stunned” when he heard the news on Wednesday and said the switch presents “the single biggest opportunity for medical school education reform since the Flexner Report,” which in 1910 established standards for modern medical education.

Numbers will continue for some tests

The USMLE cosponsors – the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) – said that the Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) exam and Step 3 will continue to be scored numerically. Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) will continue its pass/fail system.

The change was made after Step 1 had been roundly criticized as playing too big a role in the process of becoming a physician and for causing students to study for the test instead of engaging fully in their medical education.

Ramie Fathy, a third-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, currently studying for Step 1, said in an interview that it would have been nice personally to have the pass/fail choice, but he predicts both good and unintended consequences in the change.

The positive news, Mr. Fathy said, is that less emphasis will be put on the Step 1 test, which includes memorizing basic science details that may or not be relevant depending on later specialty choice.

“It’s not necessarily measuring what the test makers intended, which was whether or not a student can understand and apply basic science concepts to the practice of medicine,” he said.

“The current system encourages students to get as high a score as possible, which – after a certain point – translates to memorizing many little details that become increasingly less practically relevant,” Mr. Fathy said.

Pressure may move elsewhere?

However, Mr. Fathy worries that, without a scoring system to help decide who stands out in Step 1, residency program directors will depend more on the reputation of candidates’ medical school and the clout of the person writing a letter of recommendation – factors that are often influenced by family resources and social standing. That could wedge a further economic divide into the path to becoming a physician.

Mr. Fathy said he and fellow students are watching for information on what the passing bar will be and what happens with Step 2 Clinical Knowledge exam. USMLE has promised more information as soon as it is available.

“The question is whether that test will replace Step 1 as the standardized metric of student competency,” Mr. Fathy said, which would put more pressure on students further down the medical path.

Will Step 2 anxiety increase?

Dr. Carmody agreed that there is the danger that students now will spend their time studying for Step 2 CK at the expense of other parts of their education.

Meaningful reform will depend on the pass/fail move being coupled with other reforms, most importantly application caps, said Dr. Carmody, who teaches preclinical medical students and works with the residency program.

He has been blogging about Step 1 pass/fail for the past year.

Currently students can apply for as many residencies as they can pay for and Carmody said the number of applications per student has been rising over the past decade.

“That puts program directors under an impossible burden,” he said. “With our Step 1-based system, there’s significant inequality in the number of interviews people get. Programs end up overinviting the same group of people who look good on paper.”

People outside that group respond by sending more applications than they need to just to get a few interviews, Dr. Carmody added.

With caps, students would have an incentive to apply to only those programs in which they had a sincere interest, he said. Program directors also would then be better able to evaluate each application.

Switching Step 1 to pass/fail may have some effect on medical school burnout, Dr. Carmody said.

“It’s one thing to work hard when you’re on call and your patients depend on it,” he said. “But I would have a hard time staying up late every night studying something that I know in my heart is not going to help my patients, but I have to do it because I have to do better than the person who’s studying in the apartment next to me.”

Test has strayed from original purpose

Joseph Safdieh, MD, an assistant dean for clinical curriculum and director of the medical student neurology clerkship for the Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, sees the move as positive overall.

“We should not be using any single metric to define or describe our students’ overall profile,” he said in an interview.

“This has been a very significant anxiety point for our medical students for quite a number of years,” Dr. Safdieh said. “They were frustrated that their entire 4 years of medical school seemingly came down to one number.”

The test was created originally as one of three parts of licensure, he pointed out.

“Over the past 10 or 15 years, the exam has morphed to become a litmus test for very specific residency programs,” he said.

However, Dr. Safdieh has concerns that Step 2 will cultivate the same anxiety and may get too big a spotlight without the Step 1 metric, “although one could argue that test does more accurately reflect clinical material,” he said.

He also worries that students who have selected a specialty by the time they take Step 2 may find late in the game that they are less competitive in their field than they thought they were and may have to make a last-minute switch.

Dr. Safdieh said he thinks Step 2 will be next to go the pass/fail route. In reading between the lines of the announcement, he believes the test cosponsors didn’t make both pass/fail at once because it would have been “a nuclear bomb to the system.”

He credited the cosponsors with making what he called a “bold and momentous decision to initiate radical change in the overall transition between undergraduate and graduate medical education.”

Dr. Safdieh added that few in medicine were expecting Wednesday’s announcement.

“I think many of us were expecting them to go to quartile grading, not to go this far,” he said.

Dr. Safdieh suggested that, among those who may see downstream effects from the pass/fail move are offshore schools, such as those in the Caribbean. “Those schools rely on Step 1 to demonstrate that their students are meeting the rigor,” he said. But he hopes that this will lead to more holistic review.

“We’re hoping that this will force change in the system so that residency directors will look at more than just test-taking ability. They’ll look at publications and scholarship, community service and advocacy and performance in medical school,” Dr. Safdieh said.

Alison J. Whelan, MD, chief medical education officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges said in a statement, “The transition from medical school to residency training is a matter of great concern throughout academic medicine.

“The decision by the NBME and FSMB to change USMLE Step 1 score reporting to pass/fail was very carefully considered to balance student learning and student well-being,” she said. “The medical education community must now work together to identify and implement additional changes to improve the overall UME-GME [undergraduate and graduate medical education] transition system for all stakeholders and the AAMC is committed to helping lead this work.”

Dr. Fathy, Dr. Carmody, and Dr. Safdieh have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

News that the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) program will change its Step 1 scoring from a 3-digit number to pass/fail starting Jan. 1, 2022, has set off a flurry of shocked responses from students and physicians.

J. Bryan Carmody, MD, MPH, an assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said in an interview that he was “stunned” when he heard the news on Wednesday and said the switch presents “the single biggest opportunity for medical school education reform since the Flexner Report,” which in 1910 established standards for modern medical education.

Numbers will continue for some tests

The USMLE cosponsors – the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) – said that the Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) exam and Step 3 will continue to be scored numerically. Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) will continue its pass/fail system.

The change was made after Step 1 had been roundly criticized as playing too big a role in the process of becoming a physician and for causing students to study for the test instead of engaging fully in their medical education.

Ramie Fathy, a third-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, currently studying for Step 1, said in an interview that it would have been nice personally to have the pass/fail choice, but he predicts both good and unintended consequences in the change.

The positive news, Mr. Fathy said, is that less emphasis will be put on the Step 1 test, which includes memorizing basic science details that may or not be relevant depending on later specialty choice.

“It’s not necessarily measuring what the test makers intended, which was whether or not a student can understand and apply basic science concepts to the practice of medicine,” he said.

“The current system encourages students to get as high a score as possible, which – after a certain point – translates to memorizing many little details that become increasingly less practically relevant,” Mr. Fathy said.

Pressure may move elsewhere?

However, Mr. Fathy worries that, without a scoring system to help decide who stands out in Step 1, residency program directors will depend more on the reputation of candidates’ medical school and the clout of the person writing a letter of recommendation – factors that are often influenced by family resources and social standing. That could wedge a further economic divide into the path to becoming a physician.

Mr. Fathy said he and fellow students are watching for information on what the passing bar will be and what happens with Step 2 Clinical Knowledge exam. USMLE has promised more information as soon as it is available.

“The question is whether that test will replace Step 1 as the standardized metric of student competency,” Mr. Fathy said, which would put more pressure on students further down the medical path.

Will Step 2 anxiety increase?

Dr. Carmody agreed that there is the danger that students now will spend their time studying for Step 2 CK at the expense of other parts of their education.

Meaningful reform will depend on the pass/fail move being coupled with other reforms, most importantly application caps, said Dr. Carmody, who teaches preclinical medical students and works with the residency program.

He has been blogging about Step 1 pass/fail for the past year.

Currently students can apply for as many residencies as they can pay for and Carmody said the number of applications per student has been rising over the past decade.

“That puts program directors under an impossible burden,” he said. “With our Step 1-based system, there’s significant inequality in the number of interviews people get. Programs end up overinviting the same group of people who look good on paper.”

People outside that group respond by sending more applications than they need to just to get a few interviews, Dr. Carmody added.

With caps, students would have an incentive to apply to only those programs in which they had a sincere interest, he said. Program directors also would then be better able to evaluate each application.

Switching Step 1 to pass/fail may have some effect on medical school burnout, Dr. Carmody said.

“It’s one thing to work hard when you’re on call and your patients depend on it,” he said. “But I would have a hard time staying up late every night studying something that I know in my heart is not going to help my patients, but I have to do it because I have to do better than the person who’s studying in the apartment next to me.”

Test has strayed from original purpose

Joseph Safdieh, MD, an assistant dean for clinical curriculum and director of the medical student neurology clerkship for the Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, sees the move as positive overall.

“We should not be using any single metric to define or describe our students’ overall profile,” he said in an interview.

“This has been a very significant anxiety point for our medical students for quite a number of years,” Dr. Safdieh said. “They were frustrated that their entire 4 years of medical school seemingly came down to one number.”

The test was created originally as one of three parts of licensure, he pointed out.

“Over the past 10 or 15 years, the exam has morphed to become a litmus test for very specific residency programs,” he said.

However, Dr. Safdieh has concerns that Step 2 will cultivate the same anxiety and may get too big a spotlight without the Step 1 metric, “although one could argue that test does more accurately reflect clinical material,” he said.

He also worries that students who have selected a specialty by the time they take Step 2 may find late in the game that they are less competitive in their field than they thought they were and may have to make a last-minute switch.

Dr. Safdieh said he thinks Step 2 will be next to go the pass/fail route. In reading between the lines of the announcement, he believes the test cosponsors didn’t make both pass/fail at once because it would have been “a nuclear bomb to the system.”

He credited the cosponsors with making what he called a “bold and momentous decision to initiate radical change in the overall transition between undergraduate and graduate medical education.”

Dr. Safdieh added that few in medicine were expecting Wednesday’s announcement.

“I think many of us were expecting them to go to quartile grading, not to go this far,” he said.

Dr. Safdieh suggested that, among those who may see downstream effects from the pass/fail move are offshore schools, such as those in the Caribbean. “Those schools rely on Step 1 to demonstrate that their students are meeting the rigor,” he said. But he hopes that this will lead to more holistic review.

“We’re hoping that this will force change in the system so that residency directors will look at more than just test-taking ability. They’ll look at publications and scholarship, community service and advocacy and performance in medical school,” Dr. Safdieh said.

Alison J. Whelan, MD, chief medical education officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges said in a statement, “The transition from medical school to residency training is a matter of great concern throughout academic medicine.

“The decision by the NBME and FSMB to change USMLE Step 1 score reporting to pass/fail was very carefully considered to balance student learning and student well-being,” she said. “The medical education community must now work together to identify and implement additional changes to improve the overall UME-GME [undergraduate and graduate medical education] transition system for all stakeholders and the AAMC is committed to helping lead this work.”

Dr. Fathy, Dr. Carmody, and Dr. Safdieh have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

News that the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE) program will change its Step 1 scoring from a 3-digit number to pass/fail starting Jan. 1, 2022, has set off a flurry of shocked responses from students and physicians.

J. Bryan Carmody, MD, MPH, an assistant professor at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said in an interview that he was “stunned” when he heard the news on Wednesday and said the switch presents “the single biggest opportunity for medical school education reform since the Flexner Report,” which in 1910 established standards for modern medical education.

Numbers will continue for some tests

The USMLE cosponsors – the Federation of State Medical Boards (FSMB) and the National Board of Medical Examiners (NBME) – said that the Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) exam and Step 3 will continue to be scored numerically. Step 2 Clinical Skills (CS) will continue its pass/fail system.

The change was made after Step 1 had been roundly criticized as playing too big a role in the process of becoming a physician and for causing students to study for the test instead of engaging fully in their medical education.

Ramie Fathy, a third-year medical student at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, currently studying for Step 1, said in an interview that it would have been nice personally to have the pass/fail choice, but he predicts both good and unintended consequences in the change.

The positive news, Mr. Fathy said, is that less emphasis will be put on the Step 1 test, which includes memorizing basic science details that may or not be relevant depending on later specialty choice.

“It’s not necessarily measuring what the test makers intended, which was whether or not a student can understand and apply basic science concepts to the practice of medicine,” he said.

“The current system encourages students to get as high a score as possible, which – after a certain point – translates to memorizing many little details that become increasingly less practically relevant,” Mr. Fathy said.

Pressure may move elsewhere?

However, Mr. Fathy worries that, without a scoring system to help decide who stands out in Step 1, residency program directors will depend more on the reputation of candidates’ medical school and the clout of the person writing a letter of recommendation – factors that are often influenced by family resources and social standing. That could wedge a further economic divide into the path to becoming a physician.

Mr. Fathy said he and fellow students are watching for information on what the passing bar will be and what happens with Step 2 Clinical Knowledge exam. USMLE has promised more information as soon as it is available.

“The question is whether that test will replace Step 1 as the standardized metric of student competency,” Mr. Fathy said, which would put more pressure on students further down the medical path.

Will Step 2 anxiety increase?

Dr. Carmody agreed that there is the danger that students now will spend their time studying for Step 2 CK at the expense of other parts of their education.

Meaningful reform will depend on the pass/fail move being coupled with other reforms, most importantly application caps, said Dr. Carmody, who teaches preclinical medical students and works with the residency program.

He has been blogging about Step 1 pass/fail for the past year.

Currently students can apply for as many residencies as they can pay for and Carmody said the number of applications per student has been rising over the past decade.

“That puts program directors under an impossible burden,” he said. “With our Step 1-based system, there’s significant inequality in the number of interviews people get. Programs end up overinviting the same group of people who look good on paper.”

People outside that group respond by sending more applications than they need to just to get a few interviews, Dr. Carmody added.

With caps, students would have an incentive to apply to only those programs in which they had a sincere interest, he said. Program directors also would then be better able to evaluate each application.

Switching Step 1 to pass/fail may have some effect on medical school burnout, Dr. Carmody said.

“It’s one thing to work hard when you’re on call and your patients depend on it,” he said. “But I would have a hard time staying up late every night studying something that I know in my heart is not going to help my patients, but I have to do it because I have to do better than the person who’s studying in the apartment next to me.”

Test has strayed from original purpose

Joseph Safdieh, MD, an assistant dean for clinical curriculum and director of the medical student neurology clerkship for the Weill Cornell Medicine, New York, sees the move as positive overall.

“We should not be using any single metric to define or describe our students’ overall profile,” he said in an interview.

“This has been a very significant anxiety point for our medical students for quite a number of years,” Dr. Safdieh said. “They were frustrated that their entire 4 years of medical school seemingly came down to one number.”

The test was created originally as one of three parts of licensure, he pointed out.

“Over the past 10 or 15 years, the exam has morphed to become a litmus test for very specific residency programs,” he said.

However, Dr. Safdieh has concerns that Step 2 will cultivate the same anxiety and may get too big a spotlight without the Step 1 metric, “although one could argue that test does more accurately reflect clinical material,” he said.

He also worries that students who have selected a specialty by the time they take Step 2 may find late in the game that they are less competitive in their field than they thought they were and may have to make a last-minute switch.

Dr. Safdieh said he thinks Step 2 will be next to go the pass/fail route. In reading between the lines of the announcement, he believes the test cosponsors didn’t make both pass/fail at once because it would have been “a nuclear bomb to the system.”

He credited the cosponsors with making what he called a “bold and momentous decision to initiate radical change in the overall transition between undergraduate and graduate medical education.”

Dr. Safdieh added that few in medicine were expecting Wednesday’s announcement.

“I think many of us were expecting them to go to quartile grading, not to go this far,” he said.

Dr. Safdieh suggested that, among those who may see downstream effects from the pass/fail move are offshore schools, such as those in the Caribbean. “Those schools rely on Step 1 to demonstrate that their students are meeting the rigor,” he said. But he hopes that this will lead to more holistic review.

“We’re hoping that this will force change in the system so that residency directors will look at more than just test-taking ability. They’ll look at publications and scholarship, community service and advocacy and performance in medical school,” Dr. Safdieh said.

Alison J. Whelan, MD, chief medical education officer of the Association of American Medical Colleges said in a statement, “The transition from medical school to residency training is a matter of great concern throughout academic medicine.

“The decision by the NBME and FSMB to change USMLE Step 1 score reporting to pass/fail was very carefully considered to balance student learning and student well-being,” she said. “The medical education community must now work together to identify and implement additional changes to improve the overall UME-GME [undergraduate and graduate medical education] transition system for all stakeholders and the AAMC is committed to helping lead this work.”

Dr. Fathy, Dr. Carmody, and Dr. Safdieh have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

My inspiration

Kobe Bryant knew me. Not personally, of course. I never received an autograph or shook his hand. But once in a while if I was up early enough, I’d run into Kobe at the gym in Newport Beach where he and I both worked out. As he did for all his fans at the gym, he’d make eye contact with me and nod hello. He was always focused on his workout – working with a trainer, never with headphones on. In person, he appeared enormous. Unlike most retired professional athletes, he still was in great shape. No doubt he could have suited up in purple and gold, and played against the Clippers that night if needed.

Being from New England, I never was a Laker fan. But I thought, if Kobe can head to the gym after midnight and take a 1,000 shots to prepare for a game, then I could set my alarm for 4 a.m. and take a few dozen more questions from my First Aid books. Head down, “Kryptonite” cranked on my iPod, I wasn’t going to let anyone in that test room outwork me. Neither did he. I put in the time and, like Kobe in the 2002 conference finals against Sacramento, I crushed it.*

When we moved to California, I followed Kobe and the Lakers until he retired. To be clear, I didn’t aspire to be like him, firstly because I’m slightly shorter than Michael Bloomberg, but also because although accomplished, Kobe made some poor choices at times. Indeed, it seems he might have been kinder and more considerate when he was at the top. But in his retirement he looked to be toiling to make reparations, refocusing his prodigious energy and talent for the benefit of others rather than for just for scoring 81 points. His Rolls Royce was there before mine at the gym, and I was there early. He was still getting up early and now preparing to be a great venture capitalist, podcaster, author, and father to his girls.

Watching him carry kettle bells across the floor one morning, I wondered, do people like Kobe Bryant look to others for inspiration? Or are they are born with an endless supply of it? For me, I seemed to push harder and faster when watching idols pass by. Whether it was Kobe or Clayton Christensen (author of “The Innovator’s Dilemma”), Joe Jorizzo, or Barack Obama, I found I could do just a bit more if I had them in mind.

On game days, Kobe spoke of arriving at the arena early, long before anyone. He would use the silent, solo time to reflect on what he needed to do perform that night. I tried this last week, arriving at our clinic early, before any patients or staff. I turned the lights on and took a few minutes to think about what we needed to accomplish that day. I previewed patients on my schedule, searched Up to Date for the latest recommendations on a difficult case. I didn’t know Kobe, but I felt like I did.

When I received the text that Kobe Bryant had died, I was actually working on this column. So I decided to change the topic to write about people who inspire me, ironically inspired by him again. May he rest in peace.

Dr. Benabio is director of Healthcare Transformation and chief of dermatology at Kaiser Permanente San Diego. The opinions expressed in this column are his own and do not represent those of Kaiser Permanente. Dr. Benabio is @Dermdoc on Twitter. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

*This article was updated 2/19/2020.

Kobe Bryant knew me. Not personally, of course. I never received an autograph or shook his hand. But once in a while if I was up early enough, I’d run into Kobe at the gym in Newport Beach where he and I both worked out. As he did for all his fans at the gym, he’d make eye contact with me and nod hello. He was always focused on his workout – working with a trainer, never with headphones on. In person, he appeared enormous. Unlike most retired professional athletes, he still was in great shape. No doubt he could have suited up in purple and gold, and played against the Clippers that night if needed.

Being from New England, I never was a Laker fan. But I thought, if Kobe can head to the gym after midnight and take a 1,000 shots to prepare for a game, then I could set my alarm for 4 a.m. and take a few dozen more questions from my First Aid books. Head down, “Kryptonite” cranked on my iPod, I wasn’t going to let anyone in that test room outwork me. Neither did he. I put in the time and, like Kobe in the 2002 conference finals against Sacramento, I crushed it.*