User login

50 years of growth: More dermatologists, more demand

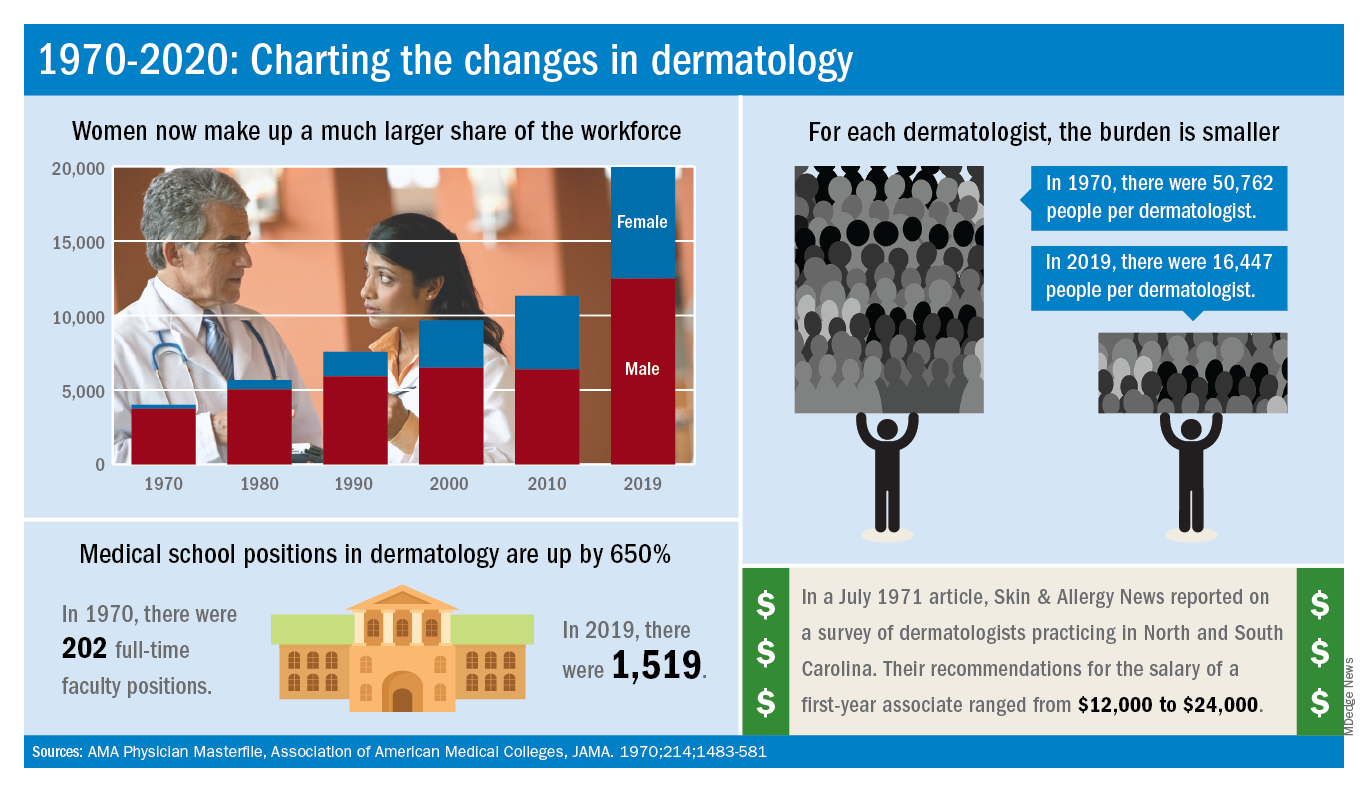

A dive into the dermatology data pool reveals a great deal of change in the 50 years that Dermatology News and Skin & Allergy News have been covering the specialty.

For one thing, there are a lot more dermatologists now. The American Academy of Dermatology puts its 2020 membership at a somewhat lower 18,898, noting that not all dermatologists are AAD members.

Much of that 50-year increase comes from the larger proportion of women entering the specialty. In 1970, only 7% of dermatologists were women, but by 2019 they represented over 37% of the dermatology workforce, according to the AMA numbers. The AAD, however, reports more women than the AMA (8,940 vs. 7,482), so the proportion of female academy members in 2020 is about 47%.

The population of dermatologists has increased faster than the general population since 1970, leading to a rising density of providers. A report from 1973 put the national figure at 1.7 dermatologists per 100,000 population in 1970, and two more recent studies in JAMA Dermatology reported density levels of 3.65 per 100,000 in 2013 and 3.36 per 100,000 in 2016.

In that 1973 report, the authors said that there was “no evidence to suggest that there will not be sufficient dermatologists in the future, if training centers are maintained and adequately financed,” noting that “the current rate of filling of dermatologic residency positions should not diminish and may continue to increase.”

In 2017, the conclusion was quite different: “Dermatologists alone have been unable to meet increasing patient demand for dermatologic services. The number of dermatology residency training positions has been relatively stagnant, suggesting that the current supply of dermatologists in training will be insufficient to fully meet growing future demand.”

The current state of strong demand for dermatologists does come with some benefits. In a 2019 survey by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, dermatologists had the 6th-highest starting salary at $420,000 a year. An article in the July 1971 issue of Skin & Allergy News offered a somewhat different perspective on compensation for first-year dermatologists: Recommendations offered by those already in practice ranged from $12,000 to $24,000.

Those first-year physicians are coming from residencies that, not too surprisingly, are now producing more new dermatologists than they did in 1970, although perhaps not as many more as might be expected.

There were an estimated 250 individuals completing dermatology residencies annually in 1976 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4[3]:344-5), which suggests a total of approximately 750 active residents at a time when there were about 5,000 practicing dermatologists in the country.

For the 2018-2019 academic year, there were 1,439 active residents in U.S. training programs, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, so there were twice the number of residents but four times as many dermatologists in practice, compared with 1976.

The next link in the dermatology supply chain would be the medical schools, and there the numbers of full-time faculty have more than kept up. For the 1969-1970 academic year, there were 202 full-time positions in dermatology (JAMA. 1970;214:1483-581). By 2019, the number had risen to 1,519, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

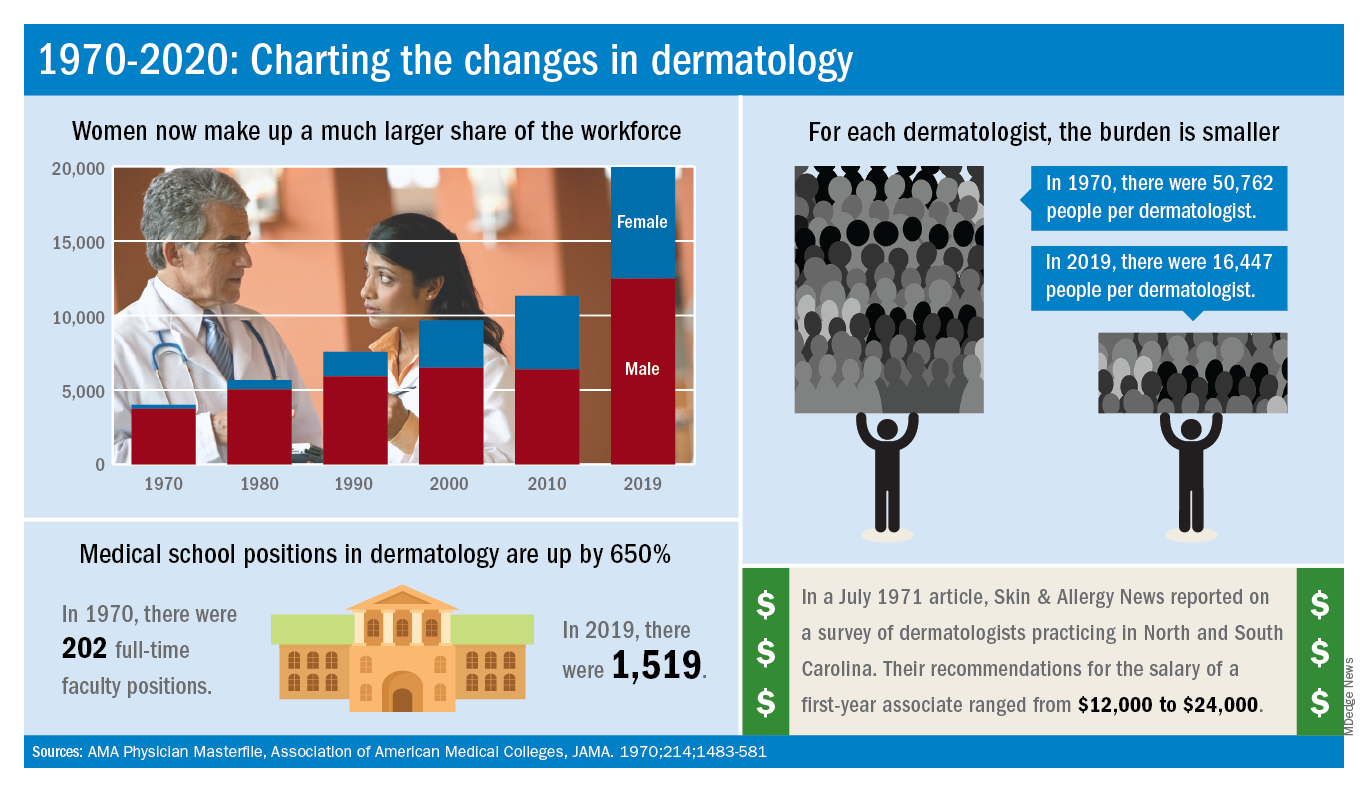

A dive into the dermatology data pool reveals a great deal of change in the 50 years that Dermatology News and Skin & Allergy News have been covering the specialty.

For one thing, there are a lot more dermatologists now. The American Academy of Dermatology puts its 2020 membership at a somewhat lower 18,898, noting that not all dermatologists are AAD members.

Much of that 50-year increase comes from the larger proportion of women entering the specialty. In 1970, only 7% of dermatologists were women, but by 2019 they represented over 37% of the dermatology workforce, according to the AMA numbers. The AAD, however, reports more women than the AMA (8,940 vs. 7,482), so the proportion of female academy members in 2020 is about 47%.

The population of dermatologists has increased faster than the general population since 1970, leading to a rising density of providers. A report from 1973 put the national figure at 1.7 dermatologists per 100,000 population in 1970, and two more recent studies in JAMA Dermatology reported density levels of 3.65 per 100,000 in 2013 and 3.36 per 100,000 in 2016.

In that 1973 report, the authors said that there was “no evidence to suggest that there will not be sufficient dermatologists in the future, if training centers are maintained and adequately financed,” noting that “the current rate of filling of dermatologic residency positions should not diminish and may continue to increase.”

In 2017, the conclusion was quite different: “Dermatologists alone have been unable to meet increasing patient demand for dermatologic services. The number of dermatology residency training positions has been relatively stagnant, suggesting that the current supply of dermatologists in training will be insufficient to fully meet growing future demand.”

The current state of strong demand for dermatologists does come with some benefits. In a 2019 survey by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, dermatologists had the 6th-highest starting salary at $420,000 a year. An article in the July 1971 issue of Skin & Allergy News offered a somewhat different perspective on compensation for first-year dermatologists: Recommendations offered by those already in practice ranged from $12,000 to $24,000.

Those first-year physicians are coming from residencies that, not too surprisingly, are now producing more new dermatologists than they did in 1970, although perhaps not as many more as might be expected.

There were an estimated 250 individuals completing dermatology residencies annually in 1976 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4[3]:344-5), which suggests a total of approximately 750 active residents at a time when there were about 5,000 practicing dermatologists in the country.

For the 2018-2019 academic year, there were 1,439 active residents in U.S. training programs, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, so there were twice the number of residents but four times as many dermatologists in practice, compared with 1976.

The next link in the dermatology supply chain would be the medical schools, and there the numbers of full-time faculty have more than kept up. For the 1969-1970 academic year, there were 202 full-time positions in dermatology (JAMA. 1970;214:1483-581). By 2019, the number had risen to 1,519, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

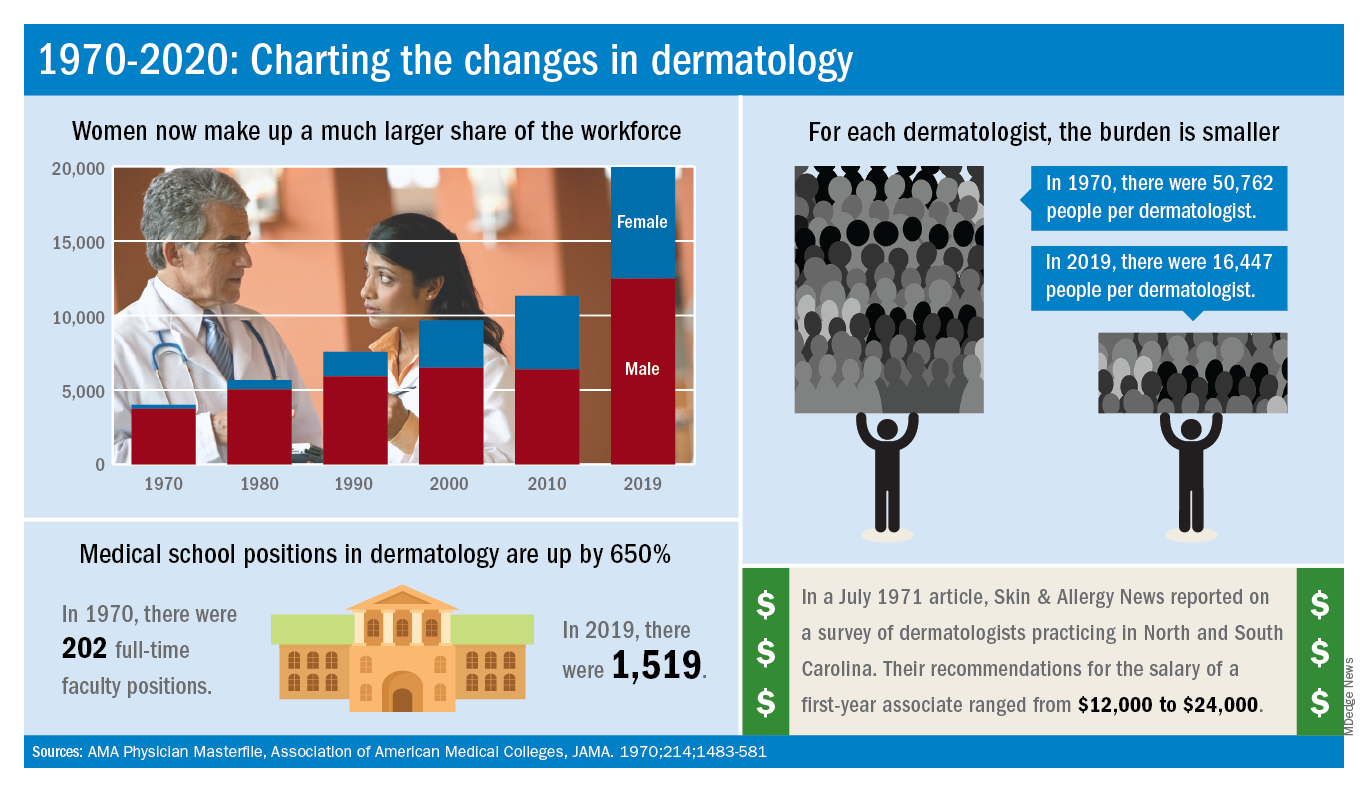

A dive into the dermatology data pool reveals a great deal of change in the 50 years that Dermatology News and Skin & Allergy News have been covering the specialty.

For one thing, there are a lot more dermatologists now. The American Academy of Dermatology puts its 2020 membership at a somewhat lower 18,898, noting that not all dermatologists are AAD members.

Much of that 50-year increase comes from the larger proportion of women entering the specialty. In 1970, only 7% of dermatologists were women, but by 2019 they represented over 37% of the dermatology workforce, according to the AMA numbers. The AAD, however, reports more women than the AMA (8,940 vs. 7,482), so the proportion of female academy members in 2020 is about 47%.

The population of dermatologists has increased faster than the general population since 1970, leading to a rising density of providers. A report from 1973 put the national figure at 1.7 dermatologists per 100,000 population in 1970, and two more recent studies in JAMA Dermatology reported density levels of 3.65 per 100,000 in 2013 and 3.36 per 100,000 in 2016.

In that 1973 report, the authors said that there was “no evidence to suggest that there will not be sufficient dermatologists in the future, if training centers are maintained and adequately financed,” noting that “the current rate of filling of dermatologic residency positions should not diminish and may continue to increase.”

In 2017, the conclusion was quite different: “Dermatologists alone have been unable to meet increasing patient demand for dermatologic services. The number of dermatology residency training positions has been relatively stagnant, suggesting that the current supply of dermatologists in training will be insufficient to fully meet growing future demand.”

The current state of strong demand for dermatologists does come with some benefits. In a 2019 survey by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins, dermatologists had the 6th-highest starting salary at $420,000 a year. An article in the July 1971 issue of Skin & Allergy News offered a somewhat different perspective on compensation for first-year dermatologists: Recommendations offered by those already in practice ranged from $12,000 to $24,000.

Those first-year physicians are coming from residencies that, not too surprisingly, are now producing more new dermatologists than they did in 1970, although perhaps not as many more as might be expected.

There were an estimated 250 individuals completing dermatology residencies annually in 1976 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 1981;4[3]:344-5), which suggests a total of approximately 750 active residents at a time when there were about 5,000 practicing dermatologists in the country.

For the 2018-2019 academic year, there were 1,439 active residents in U.S. training programs, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges, so there were twice the number of residents but four times as many dermatologists in practice, compared with 1976.

The next link in the dermatology supply chain would be the medical schools, and there the numbers of full-time faculty have more than kept up. For the 1969-1970 academic year, there were 202 full-time positions in dermatology (JAMA. 1970;214:1483-581). By 2019, the number had risen to 1,519, according to the Association of American Medical Colleges.

Oncologists are average in terms of happiness, survey suggests

When it comes to physician happiness both in and outside the workplace, oncologists are about average, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

Oncologists landed in the middle of the pack among all physicians surveyed for happiness. Rheumatologists were most likely to report being very or extremely happy outside of work (60%) and neurologists were least likely to do so (44%), but about half of oncologists (51%) reported being very/extremely happy outside of work. For happiness at work, dermatologists topped the list (41%), neurologists came in last (18%), and oncologists remained in the middle (29%).

Oncologists were average when it came to burnout as well, matching the rate of overall physicians. Specifically, 32% of oncologists were burned out, 4% were depressed, and 9% were both burned out and depressed.

The most commonly reported factors contributing to burnout among oncologists were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (74%), spending too many hours at work (42%), and a lack of respect from colleagues in the workplace (36%).

Exercise was the most commonly reported way oncologists dealt with burnout (51%), followed by talking with family and friends (49%), and isolating themselves from others (38%). In addition, 57% of oncologists took 3-4 weeks’ vacation, compared with 44% of physicians overall; 29% of oncologists took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 18% of oncologists said they had contemplated suicide, and 1% said they’d attempted it; 72% said they’d never had thoughts of suicide. Just under one-quarter of oncologists said they were currently seeking professional help or were planning to seek help for symptoms of depression and/or burnout.

“The survey results are concerning on several levels,” Maurie Markman, MD, of Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“First, the data suggest a considerable number of oncologists are simply burned out from the day-to-day bureaucracy (paperwork, etc.) of medical practice, which has absolutely nothing to do with the actual care delivered. This likely impacts the willingness to continue in this role. Second, one must be concerned for the future recruitment of physicians to become clinical oncologists. And finally, one must wonder about the impact of these concerning figures on the quality of care being provided to cancer patients.”

This survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians. Oncologists made up 1% of the survey pool.

When it comes to physician happiness both in and outside the workplace, oncologists are about average, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

Oncologists landed in the middle of the pack among all physicians surveyed for happiness. Rheumatologists were most likely to report being very or extremely happy outside of work (60%) and neurologists were least likely to do so (44%), but about half of oncologists (51%) reported being very/extremely happy outside of work. For happiness at work, dermatologists topped the list (41%), neurologists came in last (18%), and oncologists remained in the middle (29%).

Oncologists were average when it came to burnout as well, matching the rate of overall physicians. Specifically, 32% of oncologists were burned out, 4% were depressed, and 9% were both burned out and depressed.

The most commonly reported factors contributing to burnout among oncologists were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (74%), spending too many hours at work (42%), and a lack of respect from colleagues in the workplace (36%).

Exercise was the most commonly reported way oncologists dealt with burnout (51%), followed by talking with family and friends (49%), and isolating themselves from others (38%). In addition, 57% of oncologists took 3-4 weeks’ vacation, compared with 44% of physicians overall; 29% of oncologists took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 18% of oncologists said they had contemplated suicide, and 1% said they’d attempted it; 72% said they’d never had thoughts of suicide. Just under one-quarter of oncologists said they were currently seeking professional help or were planning to seek help for symptoms of depression and/or burnout.

“The survey results are concerning on several levels,” Maurie Markman, MD, of Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“First, the data suggest a considerable number of oncologists are simply burned out from the day-to-day bureaucracy (paperwork, etc.) of medical practice, which has absolutely nothing to do with the actual care delivered. This likely impacts the willingness to continue in this role. Second, one must be concerned for the future recruitment of physicians to become clinical oncologists. And finally, one must wonder about the impact of these concerning figures on the quality of care being provided to cancer patients.”

This survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians. Oncologists made up 1% of the survey pool.

When it comes to physician happiness both in and outside the workplace, oncologists are about average, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

Oncologists landed in the middle of the pack among all physicians surveyed for happiness. Rheumatologists were most likely to report being very or extremely happy outside of work (60%) and neurologists were least likely to do so (44%), but about half of oncologists (51%) reported being very/extremely happy outside of work. For happiness at work, dermatologists topped the list (41%), neurologists came in last (18%), and oncologists remained in the middle (29%).

Oncologists were average when it came to burnout as well, matching the rate of overall physicians. Specifically, 32% of oncologists were burned out, 4% were depressed, and 9% were both burned out and depressed.

The most commonly reported factors contributing to burnout among oncologists were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (74%), spending too many hours at work (42%), and a lack of respect from colleagues in the workplace (36%).

Exercise was the most commonly reported way oncologists dealt with burnout (51%), followed by talking with family and friends (49%), and isolating themselves from others (38%). In addition, 57% of oncologists took 3-4 weeks’ vacation, compared with 44% of physicians overall; 29% of oncologists took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 18% of oncologists said they had contemplated suicide, and 1% said they’d attempted it; 72% said they’d never had thoughts of suicide. Just under one-quarter of oncologists said they were currently seeking professional help or were planning to seek help for symptoms of depression and/or burnout.

“The survey results are concerning on several levels,” Maurie Markman, MD, of Cancer Treatment Centers of America, Philadelphia, said in an interview.

“First, the data suggest a considerable number of oncologists are simply burned out from the day-to-day bureaucracy (paperwork, etc.) of medical practice, which has absolutely nothing to do with the actual care delivered. This likely impacts the willingness to continue in this role. Second, one must be concerned for the future recruitment of physicians to become clinical oncologists. And finally, one must wonder about the impact of these concerning figures on the quality of care being provided to cancer patients.”

This survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians. Oncologists made up 1% of the survey pool.

Cardiologists’ happiness average both in and outside the office

Compared with their colleagues, cardiologists are in the middle when it comes to happiness both in and outside the workplace, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 28% of cardiologists reported that they were very happy in the workplace, according to the Medscape report, with dermatologists taking the top spot at 41%; 51% of cardiologists said that they were very happy outside of work, 9 percentage points behind rheumatologists at 60%.

The burnout rate for cardiologists was 29%, well below the 41% average for all physicians. About 15% of cardiologists reported that they were both burned out and depressed. An overabundance of bureaucratic tasks was the most commonly reported contributing factor to burnout at 64%, followed by spending too many hours at work at 39% and increased usage of EHRs at 33%.

Cardiologists most commonly dealt with burnout by exercising (45%), talking with friends/family (43%), and isolating themselves from others (42%). In addition, 47% of cardiologists reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, slightly more than the 44% average for all physicians; only 29% said they had taken less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 10% of cardiologists said that they’d contemplated suicide and 1% reported that they’d attempted it; 83% reported that they’d never thought about suicide. Only 10% of cardiologists reported that they were either currently seeking help or were planning to seek professional help for symptoms of burnout and/or depression, while 76% said they had no plans to consult help and had not done so in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Compared with their colleagues, cardiologists are in the middle when it comes to happiness both in and outside the workplace, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 28% of cardiologists reported that they were very happy in the workplace, according to the Medscape report, with dermatologists taking the top spot at 41%; 51% of cardiologists said that they were very happy outside of work, 9 percentage points behind rheumatologists at 60%.

The burnout rate for cardiologists was 29%, well below the 41% average for all physicians. About 15% of cardiologists reported that they were both burned out and depressed. An overabundance of bureaucratic tasks was the most commonly reported contributing factor to burnout at 64%, followed by spending too many hours at work at 39% and increased usage of EHRs at 33%.

Cardiologists most commonly dealt with burnout by exercising (45%), talking with friends/family (43%), and isolating themselves from others (42%). In addition, 47% of cardiologists reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, slightly more than the 44% average for all physicians; only 29% said they had taken less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 10% of cardiologists said that they’d contemplated suicide and 1% reported that they’d attempted it; 83% reported that they’d never thought about suicide. Only 10% of cardiologists reported that they were either currently seeking help or were planning to seek professional help for symptoms of burnout and/or depression, while 76% said they had no plans to consult help and had not done so in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Compared with their colleagues, cardiologists are in the middle when it comes to happiness both in and outside the workplace, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 28% of cardiologists reported that they were very happy in the workplace, according to the Medscape report, with dermatologists taking the top spot at 41%; 51% of cardiologists said that they were very happy outside of work, 9 percentage points behind rheumatologists at 60%.

The burnout rate for cardiologists was 29%, well below the 41% average for all physicians. About 15% of cardiologists reported that they were both burned out and depressed. An overabundance of bureaucratic tasks was the most commonly reported contributing factor to burnout at 64%, followed by spending too many hours at work at 39% and increased usage of EHRs at 33%.

Cardiologists most commonly dealt with burnout by exercising (45%), talking with friends/family (43%), and isolating themselves from others (42%). In addition, 47% of cardiologists reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, slightly more than the 44% average for all physicians; only 29% said they had taken less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 10% of cardiologists said that they’d contemplated suicide and 1% reported that they’d attempted it; 83% reported that they’d never thought about suicide. Only 10% of cardiologists reported that they were either currently seeking help or were planning to seek professional help for symptoms of burnout and/or depression, while 76% said they had no plans to consult help and had not done so in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

An epidemic of fear and misinformation

As I write this, the 2019 novel coronavirus* continues to spread, exceeding 59,000 cases and 1,300 deaths worldwide. With it spreads fear. In the modern world of social media, misinformation spreads even faster than disease.

The news about a novel and deadly illness crowds out more substantial worries. Humans are not particularly good at assessing risk or responding rationally and consistently to it. Risk is hard to fully define. If you look up “risk” in Merriam Webster’s online dictionary, you get the simple definition of “possibility of loss or injury; peril.” If you look up risk in Wikipedia, you get 12 pages of explanation and 8 more pages of links and references.

People handle risk differently. Some people are more risk adverse than others. Some get a pleasurable thrill from risk, whether a slot machine or a parachute jump. Most people really don’t comprehend small probabilities, with tens of billions of dollars spent annually on U.S. lotteries.

Because 98% of people who get COVID-19 are recovering, this is not an extinction-level event or the zombie apocalypse. It is a major health hazard, and one where morbidity and mortality might be assuaged by an early and effective public health response, including the population’s adoption of good habits such as hand washing, cough etiquette, and staying home when ill.

Three key factors may help reduce the fear factor.

One key factor is accurate communication of health information to the public. This has been severely harmed in the last few years by the promotion of gossip on social media, such as Facebook, within newsfeeds without any vetting, along with a smaller component of deliberate misinformation from untraceable sources. Compare this situation with the decision in May 1988 when Surgeon General C. Everett Koop chose to snail mail a brochure on AIDS to every household in America. It was unprecedented. One element of this communication is the public’s belief that government and health care officials will responsibly and timely convey the information. There are accusations that the Chinese government initially impeded early warnings about COVID-19. Dr. Koop, to his great credit and lifesaving leadership, overcame queasiness within the Reagan administration about issues of morality and taste in discussing some of the HIV information. Alas, no similar leadership occurred in the decade of the 2010s when deaths from the opioid epidemic in the United States skyrocketed to claim more lives annually than car accidents or suicide.

A second factor is the credibility of the scientists. Antivaxxers, climate change deniers, and mercenary scientists have severely damaged that credibility of science, compared with the trust in scientists 50 years ago during the Apollo moon shot.

A third factor is perspective. Poor journalism and clickbait can focus excessively on the rare events as news. Airline crashes make the front page while fatal car accidents, claiming a hundred times more lives annually, don’t even merit a story in local media. Someone wins the lottery weekly but few pay attention to those suffering from gambling debts.

Influenza is killing many times more people than the 2019 novel coronavirus, but the news is focused on cruise ships. In the United States, influenza annually will strike tens of millions, with about 10 per 1,000 hospitalized and 0.5 per 1,000 dying. The novel coronavirus is more lethal. SARS (a coronavirus epidemic in 2003) had 8,000 cases with a mortality rate of 96 per 1,000 while the novel 2019 strain so far is killing about 20 per 1,000. That value may be an overestimate, because there may be a significant fraction of COVID-19 patients with symptoms mild enough that they do not seek medical care and do not get tested and counted.

For perspective, in 1952 the United States reported 50,000 cases of polio (meningitis or paralytic) annually with 3,000 deaths. As many as 95% of cases of poliovirus infection have no or mild symptoms and would not have been reported, so the case fatality rate estimate is skewed. In the 1950s, the United States averaged about 500,000 cases of measles per year, with about 500 deaths annually for a case fatality rate of about 1 per 1,000 in a population that was well nourished with good medical care. In malnourished children without access to modern health care, the case fatality rate can be as high as 100 per 1,000, which is why globally measles killed 142,000 people in 2018, a substantial improvement from 536,000 deaths globally in 2000, but still a leading killer of children worldwide. Vaccines had reduced the annual death toll of polio and measles in the U.S. to zero.

In comparison, in this country the annual incidences are about 70,000 overdose deaths, 50,000 suicides, and 40,000 traffic deaths.

Reassurance is the most common product sold by pediatricians. We look for low-probability, high-impact bad things. Usually we don’t find them and can reassure parents that the child will be okay. Sometimes we spot a higher-risk situation and intervene. My job is to worry professionally so that parents can worry less.

COVID-19 worries me, but irrational people worry me more. The real enemies are fear, disinformation, discrimination, and economic warfare.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

*This article was updated 2/21/2020.

As I write this, the 2019 novel coronavirus* continues to spread, exceeding 59,000 cases and 1,300 deaths worldwide. With it spreads fear. In the modern world of social media, misinformation spreads even faster than disease.

The news about a novel and deadly illness crowds out more substantial worries. Humans are not particularly good at assessing risk or responding rationally and consistently to it. Risk is hard to fully define. If you look up “risk” in Merriam Webster’s online dictionary, you get the simple definition of “possibility of loss or injury; peril.” If you look up risk in Wikipedia, you get 12 pages of explanation and 8 more pages of links and references.

People handle risk differently. Some people are more risk adverse than others. Some get a pleasurable thrill from risk, whether a slot machine or a parachute jump. Most people really don’t comprehend small probabilities, with tens of billions of dollars spent annually on U.S. lotteries.

Because 98% of people who get COVID-19 are recovering, this is not an extinction-level event or the zombie apocalypse. It is a major health hazard, and one where morbidity and mortality might be assuaged by an early and effective public health response, including the population’s adoption of good habits such as hand washing, cough etiquette, and staying home when ill.

Three key factors may help reduce the fear factor.

One key factor is accurate communication of health information to the public. This has been severely harmed in the last few years by the promotion of gossip on social media, such as Facebook, within newsfeeds without any vetting, along with a smaller component of deliberate misinformation from untraceable sources. Compare this situation with the decision in May 1988 when Surgeon General C. Everett Koop chose to snail mail a brochure on AIDS to every household in America. It was unprecedented. One element of this communication is the public’s belief that government and health care officials will responsibly and timely convey the information. There are accusations that the Chinese government initially impeded early warnings about COVID-19. Dr. Koop, to his great credit and lifesaving leadership, overcame queasiness within the Reagan administration about issues of morality and taste in discussing some of the HIV information. Alas, no similar leadership occurred in the decade of the 2010s when deaths from the opioid epidemic in the United States skyrocketed to claim more lives annually than car accidents or suicide.

A second factor is the credibility of the scientists. Antivaxxers, climate change deniers, and mercenary scientists have severely damaged that credibility of science, compared with the trust in scientists 50 years ago during the Apollo moon shot.

A third factor is perspective. Poor journalism and clickbait can focus excessively on the rare events as news. Airline crashes make the front page while fatal car accidents, claiming a hundred times more lives annually, don’t even merit a story in local media. Someone wins the lottery weekly but few pay attention to those suffering from gambling debts.

Influenza is killing many times more people than the 2019 novel coronavirus, but the news is focused on cruise ships. In the United States, influenza annually will strike tens of millions, with about 10 per 1,000 hospitalized and 0.5 per 1,000 dying. The novel coronavirus is more lethal. SARS (a coronavirus epidemic in 2003) had 8,000 cases with a mortality rate of 96 per 1,000 while the novel 2019 strain so far is killing about 20 per 1,000. That value may be an overestimate, because there may be a significant fraction of COVID-19 patients with symptoms mild enough that they do not seek medical care and do not get tested and counted.

For perspective, in 1952 the United States reported 50,000 cases of polio (meningitis or paralytic) annually with 3,000 deaths. As many as 95% of cases of poliovirus infection have no or mild symptoms and would not have been reported, so the case fatality rate estimate is skewed. In the 1950s, the United States averaged about 500,000 cases of measles per year, with about 500 deaths annually for a case fatality rate of about 1 per 1,000 in a population that was well nourished with good medical care. In malnourished children without access to modern health care, the case fatality rate can be as high as 100 per 1,000, which is why globally measles killed 142,000 people in 2018, a substantial improvement from 536,000 deaths globally in 2000, but still a leading killer of children worldwide. Vaccines had reduced the annual death toll of polio and measles in the U.S. to zero.

In comparison, in this country the annual incidences are about 70,000 overdose deaths, 50,000 suicides, and 40,000 traffic deaths.

Reassurance is the most common product sold by pediatricians. We look for low-probability, high-impact bad things. Usually we don’t find them and can reassure parents that the child will be okay. Sometimes we spot a higher-risk situation and intervene. My job is to worry professionally so that parents can worry less.

COVID-19 worries me, but irrational people worry me more. The real enemies are fear, disinformation, discrimination, and economic warfare.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

*This article was updated 2/21/2020.

As I write this, the 2019 novel coronavirus* continues to spread, exceeding 59,000 cases and 1,300 deaths worldwide. With it spreads fear. In the modern world of social media, misinformation spreads even faster than disease.

The news about a novel and deadly illness crowds out more substantial worries. Humans are not particularly good at assessing risk or responding rationally and consistently to it. Risk is hard to fully define. If you look up “risk” in Merriam Webster’s online dictionary, you get the simple definition of “possibility of loss or injury; peril.” If you look up risk in Wikipedia, you get 12 pages of explanation and 8 more pages of links and references.

People handle risk differently. Some people are more risk adverse than others. Some get a pleasurable thrill from risk, whether a slot machine or a parachute jump. Most people really don’t comprehend small probabilities, with tens of billions of dollars spent annually on U.S. lotteries.

Because 98% of people who get COVID-19 are recovering, this is not an extinction-level event or the zombie apocalypse. It is a major health hazard, and one where morbidity and mortality might be assuaged by an early and effective public health response, including the population’s adoption of good habits such as hand washing, cough etiquette, and staying home when ill.

Three key factors may help reduce the fear factor.

One key factor is accurate communication of health information to the public. This has been severely harmed in the last few years by the promotion of gossip on social media, such as Facebook, within newsfeeds without any vetting, along with a smaller component of deliberate misinformation from untraceable sources. Compare this situation with the decision in May 1988 when Surgeon General C. Everett Koop chose to snail mail a brochure on AIDS to every household in America. It was unprecedented. One element of this communication is the public’s belief that government and health care officials will responsibly and timely convey the information. There are accusations that the Chinese government initially impeded early warnings about COVID-19. Dr. Koop, to his great credit and lifesaving leadership, overcame queasiness within the Reagan administration about issues of morality and taste in discussing some of the HIV information. Alas, no similar leadership occurred in the decade of the 2010s when deaths from the opioid epidemic in the United States skyrocketed to claim more lives annually than car accidents or suicide.

A second factor is the credibility of the scientists. Antivaxxers, climate change deniers, and mercenary scientists have severely damaged that credibility of science, compared with the trust in scientists 50 years ago during the Apollo moon shot.

A third factor is perspective. Poor journalism and clickbait can focus excessively on the rare events as news. Airline crashes make the front page while fatal car accidents, claiming a hundred times more lives annually, don’t even merit a story in local media. Someone wins the lottery weekly but few pay attention to those suffering from gambling debts.

Influenza is killing many times more people than the 2019 novel coronavirus, but the news is focused on cruise ships. In the United States, influenza annually will strike tens of millions, with about 10 per 1,000 hospitalized and 0.5 per 1,000 dying. The novel coronavirus is more lethal. SARS (a coronavirus epidemic in 2003) had 8,000 cases with a mortality rate of 96 per 1,000 while the novel 2019 strain so far is killing about 20 per 1,000. That value may be an overestimate, because there may be a significant fraction of COVID-19 patients with symptoms mild enough that they do not seek medical care and do not get tested and counted.

For perspective, in 1952 the United States reported 50,000 cases of polio (meningitis or paralytic) annually with 3,000 deaths. As many as 95% of cases of poliovirus infection have no or mild symptoms and would not have been reported, so the case fatality rate estimate is skewed. In the 1950s, the United States averaged about 500,000 cases of measles per year, with about 500 deaths annually for a case fatality rate of about 1 per 1,000 in a population that was well nourished with good medical care. In malnourished children without access to modern health care, the case fatality rate can be as high as 100 per 1,000, which is why globally measles killed 142,000 people in 2018, a substantial improvement from 536,000 deaths globally in 2000, but still a leading killer of children worldwide. Vaccines had reduced the annual death toll of polio and measles in the U.S. to zero.

In comparison, in this country the annual incidences are about 70,000 overdose deaths, 50,000 suicides, and 40,000 traffic deaths.

Reassurance is the most common product sold by pediatricians. We look for low-probability, high-impact bad things. Usually we don’t find them and can reassure parents that the child will be okay. Sometimes we spot a higher-risk situation and intervene. My job is to worry professionally so that parents can worry less.

COVID-19 worries me, but irrational people worry me more. The real enemies are fear, disinformation, discrimination, and economic warfare.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

*This article was updated 2/21/2020.

Burnout rate lower among psychiatrists than physicians overall

Psychiatrists do better compared with those in most specialties in finding happiness at work, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 32% of psychiatrists reported being happy at work, according to the Medscape survey, though they lagged well behind dermatologists, who were the most satisfied with their work lives. In terms of happiness outside the office, psychiatrists were in the middle of the pack with 51% reporting that they were happy.

Somewhat fewer psychiatrists reported being burned out, compared with physicians overall, at 37% versus 41%. The biggest contributing factors to psychiatrist burnout were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (63%), increased time devoted to EHRs (34%), and a lack of respect from colleagues in the workplace (32%).

Psychiatrists most commonly dealt with burnout by isolating themselves from others (57%), sleeping (43%), and talking with family/friends (42%). Just under half of psychiatrists took 3-4 weeks’ vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians, and 33% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

and 1% reported that they had attempted suicide. About 45% said that they were currently seeking professional help, planning to seek help, or had used help in the past to deal with burnout or depression; 48% said that they were not planning to seek help and had not done so in the past.

In an interview, Carol A. Bernstein, MD, said it is challenging to find the meaning in these survey results.

“The challenge with surveys that measure burnout is that the drivers may be somewhat different in different specialties. I am less interested in looking at ‘who has it worse’ than I am at trying to address those systemic factors that are important for all physicians, regardless of specialty,” said Dr. Bernstein of Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

“The survey noted some of these factors: the increased burden of regulation and bureaucratic tasks, an EHR that was designed for billing and scheduling – not for taking care of patients – and challenges of professionalism in the workplace. These are issues that we must address for the benefit of all health care providers and patients.”

Dr. Bernstein, a past president of the American Psychiatric Association, is vice chair for faculty development and well-being at Montefiore/Albert Einstein. She is a professor in the departments of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and obstetrics/gynecology & women’s health.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Psychiatrists do better compared with those in most specialties in finding happiness at work, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 32% of psychiatrists reported being happy at work, according to the Medscape survey, though they lagged well behind dermatologists, who were the most satisfied with their work lives. In terms of happiness outside the office, psychiatrists were in the middle of the pack with 51% reporting that they were happy.

Somewhat fewer psychiatrists reported being burned out, compared with physicians overall, at 37% versus 41%. The biggest contributing factors to psychiatrist burnout were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (63%), increased time devoted to EHRs (34%), and a lack of respect from colleagues in the workplace (32%).

Psychiatrists most commonly dealt with burnout by isolating themselves from others (57%), sleeping (43%), and talking with family/friends (42%). Just under half of psychiatrists took 3-4 weeks’ vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians, and 33% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

and 1% reported that they had attempted suicide. About 45% said that they were currently seeking professional help, planning to seek help, or had used help in the past to deal with burnout or depression; 48% said that they were not planning to seek help and had not done so in the past.

In an interview, Carol A. Bernstein, MD, said it is challenging to find the meaning in these survey results.

“The challenge with surveys that measure burnout is that the drivers may be somewhat different in different specialties. I am less interested in looking at ‘who has it worse’ than I am at trying to address those systemic factors that are important for all physicians, regardless of specialty,” said Dr. Bernstein of Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

“The survey noted some of these factors: the increased burden of regulation and bureaucratic tasks, an EHR that was designed for billing and scheduling – not for taking care of patients – and challenges of professionalism in the workplace. These are issues that we must address for the benefit of all health care providers and patients.”

Dr. Bernstein, a past president of the American Psychiatric Association, is vice chair for faculty development and well-being at Montefiore/Albert Einstein. She is a professor in the departments of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and obstetrics/gynecology & women’s health.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Psychiatrists do better compared with those in most specialties in finding happiness at work, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 32% of psychiatrists reported being happy at work, according to the Medscape survey, though they lagged well behind dermatologists, who were the most satisfied with their work lives. In terms of happiness outside the office, psychiatrists were in the middle of the pack with 51% reporting that they were happy.

Somewhat fewer psychiatrists reported being burned out, compared with physicians overall, at 37% versus 41%. The biggest contributing factors to psychiatrist burnout were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (63%), increased time devoted to EHRs (34%), and a lack of respect from colleagues in the workplace (32%).

Psychiatrists most commonly dealt with burnout by isolating themselves from others (57%), sleeping (43%), and talking with family/friends (42%). Just under half of psychiatrists took 3-4 weeks’ vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians, and 33% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

and 1% reported that they had attempted suicide. About 45% said that they were currently seeking professional help, planning to seek help, or had used help in the past to deal with burnout or depression; 48% said that they were not planning to seek help and had not done so in the past.

In an interview, Carol A. Bernstein, MD, said it is challenging to find the meaning in these survey results.

“The challenge with surveys that measure burnout is that the drivers may be somewhat different in different specialties. I am less interested in looking at ‘who has it worse’ than I am at trying to address those systemic factors that are important for all physicians, regardless of specialty,” said Dr. Bernstein of Montefiore Medical Center/Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New York.

“The survey noted some of these factors: the increased burden of regulation and bureaucratic tasks, an EHR that was designed for billing and scheduling – not for taking care of patients – and challenges of professionalism in the workplace. These are issues that we must address for the benefit of all health care providers and patients.”

Dr. Bernstein, a past president of the American Psychiatric Association, is vice chair for faculty development and well-being at Montefiore/Albert Einstein. She is a professor in the departments of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, and obstetrics/gynecology & women’s health.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

An unusual ‘retirement’ option

Whether “retirement” is withdrawing from one’s occupation or from an active working life, it is of utmost importance to not let one’s mind degenerate. Some individuals move on to gathering new intellectual skills by attending new educational courses or meetings, some travel, some become semiprofessional golfers or fishermen, and some find other forms of personal extension. I now serve to develop cost-saving medical programs for county jails in the state of Texas while attempting to improve the overall quality of inmate care.

Initially I was a pediatrician in Houston with special training in allergy and immunology, but because of a medical problem I was forced to abandon my first love – primary pediatrics. My move to a small town at the age of 40 required me to reevaluate my professional life, and I opted to provide care only in my allergy and immunology specialty.

However, living in a small town is different from life in a metropolis, and it was not uncommon for doctors to be asked to assist the community. A number of years ago, our county judge asked if I would help evaluate why our county jail was spending so much money. After several attempts to refuse, I eventually did evaluate the program there, and was flabbergasted by how much money was being wasted. I made some rather simple suggestions as how to correct the problem, but when no primary care doctor stepped forward to implement the changes and run the jail medical program, I became its medical director. When we saved $120,000 the first year, even I was astounded.

While I continued to run my private practice, I did accept other small community’s offers to look into their county jails’ programs. I found that their problems in cost control and quality of health care mirrored those I found in the first jail, and they were easily solvable if the county judge and the local sheriff wanted solutions. I also found that politics makes strange bedfellows, as the saying goes, and often the obvious changes were met with obstruction in one form or another. Nonetheless, I found that I could serve these communities in addition to my individual patients. When it was time for retirement, I continued to have a real desire to make the towns around which I lived and my own community more livable. So

In most things, I found that the same business philosophy and personal medical approach I learned in my pediatrics training and as a private practitioner applied to the jail system. Let me mention some specifics. Using generic medicines was less expensive than using brand names. The diagnoses which patients claimed when they entered jail might or might not be correct, so reevaluating the diagnosis and treatment was appropriate as soon as possible. Hospital and ED visits should be limited to patients’ medically requiring them rather than using the ED as a screening tool.

But I did come to understand that medical care in the county jail is different from medical care outside an incarcerated facility in that sometimes the prisoners had their own reasons for seeking medical care. This was complicated by the fact that often there were critically ill patients presenting to county jails. So carefully established criteria and protocols were an absolute necessity to save lives.

Let me expand on the topic of seeking medical care by the inmate-patients. A relatively small number of these individuals required immediate emergency treatment, without which they could not do well: The diabetic who was not taking his insulin, the out-of-control paranoid schizophrenic who decided he was cured and therefore was unattended, the alcoholic or drug addict who would develop delirium tremens if medications were stopped abruptly. These people had to be identified as quickly as possible and correctly treated. Confounding the problem was the fact that many, and I repeat many, individuals try to use the medical route to manipulate their incarceration environment. I called this the B problem: beds, blankets, barter, buzz, better food, and be out of here. They might claim an illness existed, and often they might believe it did.

A related situation might exist when individuals would demand psychiatric and pain medications, often in large quantities, when they in fact had not taken them for some time in the outside world. Often these patients were addicts, and of course this could create an entire other relationship with the medical team. A third example would be the claim of hypoglycemia so that the prisoner would receive more frequent meals.

One might think that as a pediatrician I was ill prepared to treat adults, and in fact, there was much review of the general medical care needed when I began this program. However, the internists and family physicians in town were glad to assist me whenever I encountered a difficult patient. When hospitalizations were required, the inpatient always was covered by one of the internists on hospital staff. Quite frankly, the doctors seemed pleased to not be dealing with this group of individuals as much as they had in the past.

On a slightly different note, skills honed during my pediatric career were extremely valuable. Children, particularly young children, do not verbally communicate with their parents or their doctor particularly well, so pediatricians are well trained in the skill of observation. The patient who claims a guard hurt his shoulder so badly during an altercation that he cannot move it is found out when he easily whips his arms over his head when asked to remove his shirt. It is not uncommon for an individual to demand antidepressant medications from the medical staff, but when evaluated more thoroughly and for a longer period of time, the patient ends up laughing, even denying any suicidal ideation or any other sign of depression. One also deals with a lot of adolescent behavior from the inmates, such as the individuals who say that unless they don’t get their way (more food) they are not going to take their medications and thus get sicker. That’s Adolescent Medicine 101.

Some of the modalities I utilized in modifying the jail programs will be familiar to every practicing pediatrician. I educate; I teach; I train. Parents of my asthmatic patients had to know what medications to keep handy and when to use them. It is pretty easy to see how that relates to jail medicine. Many patients come into jail with inhalers and with a diagnosis of asthma. Some have the condition, and some do not. By training jail and medical staff how to observe breathing patterns and by performing pulse oximetry, we eliminated a large number of unnecessary ED visits, and we often made the diagnosis of hyperventilation syndrome rather than misdiagnosed asthma.

Jail medicine is a large part of the cost of housing inmates. I did consultation work for a large urban jail, and we saved over $7 million in 1 year. In a medium-sized jail, the cost-savings after a 4-month consultation was over $300,000. This is a lot of money to me, and I suspect is to you, too. Just as in our general communities, we have enough resources to provide medical care and to provide a high level of care for all. However, we cannot waste money by providing inappropriate care or overtesting or overtreating. The medical care must be what treats the disease the patient actually has ... nothing more and nothing less!

If it sounds as if I am cynical about inmate patients, that is not true. However, I am realistic that no one wishes to be in jail. I realize that the medical route is just one that prisoners can and do use to modify their situation. I understand that the medical staff within a jail needs constant education and supervision at first, and with time they become more astute – just like a physician in this arena – at distinguishing the very serious from the mildly serious from malingering. In spite of this, we doctors also can be fooled. However, through constant vigilance and constant education we can get better.

Jail medicine is not for everyone in retirement. Heck, it is not for everyone ever. I found it interesting because it required me to match my diagnostic skills against the diseases and the psychodynamics of individuals who often – not always – made that diagnosis more difficult. Diagnosing illness and curing it – isn’t this why we all went into medicine?

Dr. Yoffe is a retired pediatrician specializing in allergy and immunology who resides in Brenham, Tex. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This article was updated 2/13/2020.

Whether “retirement” is withdrawing from one’s occupation or from an active working life, it is of utmost importance to not let one’s mind degenerate. Some individuals move on to gathering new intellectual skills by attending new educational courses or meetings, some travel, some become semiprofessional golfers or fishermen, and some find other forms of personal extension. I now serve to develop cost-saving medical programs for county jails in the state of Texas while attempting to improve the overall quality of inmate care.

Initially I was a pediatrician in Houston with special training in allergy and immunology, but because of a medical problem I was forced to abandon my first love – primary pediatrics. My move to a small town at the age of 40 required me to reevaluate my professional life, and I opted to provide care only in my allergy and immunology specialty.

However, living in a small town is different from life in a metropolis, and it was not uncommon for doctors to be asked to assist the community. A number of years ago, our county judge asked if I would help evaluate why our county jail was spending so much money. After several attempts to refuse, I eventually did evaluate the program there, and was flabbergasted by how much money was being wasted. I made some rather simple suggestions as how to correct the problem, but when no primary care doctor stepped forward to implement the changes and run the jail medical program, I became its medical director. When we saved $120,000 the first year, even I was astounded.

While I continued to run my private practice, I did accept other small community’s offers to look into their county jails’ programs. I found that their problems in cost control and quality of health care mirrored those I found in the first jail, and they were easily solvable if the county judge and the local sheriff wanted solutions. I also found that politics makes strange bedfellows, as the saying goes, and often the obvious changes were met with obstruction in one form or another. Nonetheless, I found that I could serve these communities in addition to my individual patients. When it was time for retirement, I continued to have a real desire to make the towns around which I lived and my own community more livable. So

In most things, I found that the same business philosophy and personal medical approach I learned in my pediatrics training and as a private practitioner applied to the jail system. Let me mention some specifics. Using generic medicines was less expensive than using brand names. The diagnoses which patients claimed when they entered jail might or might not be correct, so reevaluating the diagnosis and treatment was appropriate as soon as possible. Hospital and ED visits should be limited to patients’ medically requiring them rather than using the ED as a screening tool.

But I did come to understand that medical care in the county jail is different from medical care outside an incarcerated facility in that sometimes the prisoners had their own reasons for seeking medical care. This was complicated by the fact that often there were critically ill patients presenting to county jails. So carefully established criteria and protocols were an absolute necessity to save lives.

Let me expand on the topic of seeking medical care by the inmate-patients. A relatively small number of these individuals required immediate emergency treatment, without which they could not do well: The diabetic who was not taking his insulin, the out-of-control paranoid schizophrenic who decided he was cured and therefore was unattended, the alcoholic or drug addict who would develop delirium tremens if medications were stopped abruptly. These people had to be identified as quickly as possible and correctly treated. Confounding the problem was the fact that many, and I repeat many, individuals try to use the medical route to manipulate their incarceration environment. I called this the B problem: beds, blankets, barter, buzz, better food, and be out of here. They might claim an illness existed, and often they might believe it did.

A related situation might exist when individuals would demand psychiatric and pain medications, often in large quantities, when they in fact had not taken them for some time in the outside world. Often these patients were addicts, and of course this could create an entire other relationship with the medical team. A third example would be the claim of hypoglycemia so that the prisoner would receive more frequent meals.

One might think that as a pediatrician I was ill prepared to treat adults, and in fact, there was much review of the general medical care needed when I began this program. However, the internists and family physicians in town were glad to assist me whenever I encountered a difficult patient. When hospitalizations were required, the inpatient always was covered by one of the internists on hospital staff. Quite frankly, the doctors seemed pleased to not be dealing with this group of individuals as much as they had in the past.

On a slightly different note, skills honed during my pediatric career were extremely valuable. Children, particularly young children, do not verbally communicate with their parents or their doctor particularly well, so pediatricians are well trained in the skill of observation. The patient who claims a guard hurt his shoulder so badly during an altercation that he cannot move it is found out when he easily whips his arms over his head when asked to remove his shirt. It is not uncommon for an individual to demand antidepressant medications from the medical staff, but when evaluated more thoroughly and for a longer period of time, the patient ends up laughing, even denying any suicidal ideation or any other sign of depression. One also deals with a lot of adolescent behavior from the inmates, such as the individuals who say that unless they don’t get their way (more food) they are not going to take their medications and thus get sicker. That’s Adolescent Medicine 101.

Some of the modalities I utilized in modifying the jail programs will be familiar to every practicing pediatrician. I educate; I teach; I train. Parents of my asthmatic patients had to know what medications to keep handy and when to use them. It is pretty easy to see how that relates to jail medicine. Many patients come into jail with inhalers and with a diagnosis of asthma. Some have the condition, and some do not. By training jail and medical staff how to observe breathing patterns and by performing pulse oximetry, we eliminated a large number of unnecessary ED visits, and we often made the diagnosis of hyperventilation syndrome rather than misdiagnosed asthma.

Jail medicine is a large part of the cost of housing inmates. I did consultation work for a large urban jail, and we saved over $7 million in 1 year. In a medium-sized jail, the cost-savings after a 4-month consultation was over $300,000. This is a lot of money to me, and I suspect is to you, too. Just as in our general communities, we have enough resources to provide medical care and to provide a high level of care for all. However, we cannot waste money by providing inappropriate care or overtesting or overtreating. The medical care must be what treats the disease the patient actually has ... nothing more and nothing less!

If it sounds as if I am cynical about inmate patients, that is not true. However, I am realistic that no one wishes to be in jail. I realize that the medical route is just one that prisoners can and do use to modify their situation. I understand that the medical staff within a jail needs constant education and supervision at first, and with time they become more astute – just like a physician in this arena – at distinguishing the very serious from the mildly serious from malingering. In spite of this, we doctors also can be fooled. However, through constant vigilance and constant education we can get better.

Jail medicine is not for everyone in retirement. Heck, it is not for everyone ever. I found it interesting because it required me to match my diagnostic skills against the diseases and the psychodynamics of individuals who often – not always – made that diagnosis more difficult. Diagnosing illness and curing it – isn’t this why we all went into medicine?

Dr. Yoffe is a retired pediatrician specializing in allergy and immunology who resides in Brenham, Tex. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This article was updated 2/13/2020.

Whether “retirement” is withdrawing from one’s occupation or from an active working life, it is of utmost importance to not let one’s mind degenerate. Some individuals move on to gathering new intellectual skills by attending new educational courses or meetings, some travel, some become semiprofessional golfers or fishermen, and some find other forms of personal extension. I now serve to develop cost-saving medical programs for county jails in the state of Texas while attempting to improve the overall quality of inmate care.

Initially I was a pediatrician in Houston with special training in allergy and immunology, but because of a medical problem I was forced to abandon my first love – primary pediatrics. My move to a small town at the age of 40 required me to reevaluate my professional life, and I opted to provide care only in my allergy and immunology specialty.

However, living in a small town is different from life in a metropolis, and it was not uncommon for doctors to be asked to assist the community. A number of years ago, our county judge asked if I would help evaluate why our county jail was spending so much money. After several attempts to refuse, I eventually did evaluate the program there, and was flabbergasted by how much money was being wasted. I made some rather simple suggestions as how to correct the problem, but when no primary care doctor stepped forward to implement the changes and run the jail medical program, I became its medical director. When we saved $120,000 the first year, even I was astounded.

While I continued to run my private practice, I did accept other small community’s offers to look into their county jails’ programs. I found that their problems in cost control and quality of health care mirrored those I found in the first jail, and they were easily solvable if the county judge and the local sheriff wanted solutions. I also found that politics makes strange bedfellows, as the saying goes, and often the obvious changes were met with obstruction in one form or another. Nonetheless, I found that I could serve these communities in addition to my individual patients. When it was time for retirement, I continued to have a real desire to make the towns around which I lived and my own community more livable. So

In most things, I found that the same business philosophy and personal medical approach I learned in my pediatrics training and as a private practitioner applied to the jail system. Let me mention some specifics. Using generic medicines was less expensive than using brand names. The diagnoses which patients claimed when they entered jail might or might not be correct, so reevaluating the diagnosis and treatment was appropriate as soon as possible. Hospital and ED visits should be limited to patients’ medically requiring them rather than using the ED as a screening tool.

But I did come to understand that medical care in the county jail is different from medical care outside an incarcerated facility in that sometimes the prisoners had their own reasons for seeking medical care. This was complicated by the fact that often there were critically ill patients presenting to county jails. So carefully established criteria and protocols were an absolute necessity to save lives.

Let me expand on the topic of seeking medical care by the inmate-patients. A relatively small number of these individuals required immediate emergency treatment, without which they could not do well: The diabetic who was not taking his insulin, the out-of-control paranoid schizophrenic who decided he was cured and therefore was unattended, the alcoholic or drug addict who would develop delirium tremens if medications were stopped abruptly. These people had to be identified as quickly as possible and correctly treated. Confounding the problem was the fact that many, and I repeat many, individuals try to use the medical route to manipulate their incarceration environment. I called this the B problem: beds, blankets, barter, buzz, better food, and be out of here. They might claim an illness existed, and often they might believe it did.

A related situation might exist when individuals would demand psychiatric and pain medications, often in large quantities, when they in fact had not taken them for some time in the outside world. Often these patients were addicts, and of course this could create an entire other relationship with the medical team. A third example would be the claim of hypoglycemia so that the prisoner would receive more frequent meals.

One might think that as a pediatrician I was ill prepared to treat adults, and in fact, there was much review of the general medical care needed when I began this program. However, the internists and family physicians in town were glad to assist me whenever I encountered a difficult patient. When hospitalizations were required, the inpatient always was covered by one of the internists on hospital staff. Quite frankly, the doctors seemed pleased to not be dealing with this group of individuals as much as they had in the past.

On a slightly different note, skills honed during my pediatric career were extremely valuable. Children, particularly young children, do not verbally communicate with their parents or their doctor particularly well, so pediatricians are well trained in the skill of observation. The patient who claims a guard hurt his shoulder so badly during an altercation that he cannot move it is found out when he easily whips his arms over his head when asked to remove his shirt. It is not uncommon for an individual to demand antidepressant medications from the medical staff, but when evaluated more thoroughly and for a longer period of time, the patient ends up laughing, even denying any suicidal ideation or any other sign of depression. One also deals with a lot of adolescent behavior from the inmates, such as the individuals who say that unless they don’t get their way (more food) they are not going to take their medications and thus get sicker. That’s Adolescent Medicine 101.

Some of the modalities I utilized in modifying the jail programs will be familiar to every practicing pediatrician. I educate; I teach; I train. Parents of my asthmatic patients had to know what medications to keep handy and when to use them. It is pretty easy to see how that relates to jail medicine. Many patients come into jail with inhalers and with a diagnosis of asthma. Some have the condition, and some do not. By training jail and medical staff how to observe breathing patterns and by performing pulse oximetry, we eliminated a large number of unnecessary ED visits, and we often made the diagnosis of hyperventilation syndrome rather than misdiagnosed asthma.

Jail medicine is a large part of the cost of housing inmates. I did consultation work for a large urban jail, and we saved over $7 million in 1 year. In a medium-sized jail, the cost-savings after a 4-month consultation was over $300,000. This is a lot of money to me, and I suspect is to you, too. Just as in our general communities, we have enough resources to provide medical care and to provide a high level of care for all. However, we cannot waste money by providing inappropriate care or overtesting or overtreating. The medical care must be what treats the disease the patient actually has ... nothing more and nothing less!

If it sounds as if I am cynical about inmate patients, that is not true. However, I am realistic that no one wishes to be in jail. I realize that the medical route is just one that prisoners can and do use to modify their situation. I understand that the medical staff within a jail needs constant education and supervision at first, and with time they become more astute – just like a physician in this arena – at distinguishing the very serious from the mildly serious from malingering. In spite of this, we doctors also can be fooled. However, through constant vigilance and constant education we can get better.

Jail medicine is not for everyone in retirement. Heck, it is not for everyone ever. I found it interesting because it required me to match my diagnostic skills against the diseases and the psychodynamics of individuals who often – not always – made that diagnosis more difficult. Diagnosing illness and curing it – isn’t this why we all went into medicine?

Dr. Yoffe is a retired pediatrician specializing in allergy and immunology who resides in Brenham, Tex. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com.

This article was updated 2/13/2020.

Pediatricians twice as happy outside work than at work

Pediatricians are twice as likely to be happy outside the office than they are at work, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 29% of pediatricians reported being happy at work, with dermatologists taking the top spot at 41%. Pediatricians did much better when it came to finding happiness outside the office, with 57% reporting that they were very happy when away from work, according to the Medscape report.

The biggest contributing factors to burnout in pediatricians were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (59%), insufficient compensation/reimbursement (37%), and spending too many hours at work (34%).

Pediatricians most commonly dealt with burnout by talking with friends/family (54%), exercising (47%), and sleeping (41%). Just over half of pediatricians reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians; 32% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 8% of pediatricians reported that they’d contemplated suicide, but 0% reported that they’d attempted it; 85% said that they’d never thought about it. Just under one-quarter of pediatricians said that were currently seeking or planning to seek professional help for depression and/or burnout; 55% said they were not seeking help and had never made use of it in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

We all feel it. It is not surprising that only 29% of today's pediatricians report that they are "happy" at work and 30% report "burnout"!

This report serves to identify only some of the countless ways in which we are forced to compromise the 24-hour clock, leaving too little time for ourselves and families.

We spend too many hours at work, and other data show we are undercompensated for our efforts.

Today, electronically, most of us are reachable even when out of the office. It is difficult, if not impossible, to completely disconnect. The challenge to achieve the work/life balance we have all imagined is too great!

I try to carve out "forced escapes from reality" through novels, movies, and when possible, distant travel with my spouse. However, the bliss is too short lived. When I return to reality, some bliss fades as I jump back onto the "merry-go-round" for a few more turns.

Lillian M. Beard, MD, is a clinical professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington. She is a Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board member.

We all feel it. It is not surprising that only 29% of today's pediatricians report that they are "happy" at work and 30% report "burnout"!

This report serves to identify only some of the countless ways in which we are forced to compromise the 24-hour clock, leaving too little time for ourselves and families.

We spend too many hours at work, and other data show we are undercompensated for our efforts.

Today, electronically, most of us are reachable even when out of the office. It is difficult, if not impossible, to completely disconnect. The challenge to achieve the work/life balance we have all imagined is too great!

I try to carve out "forced escapes from reality" through novels, movies, and when possible, distant travel with my spouse. However, the bliss is too short lived. When I return to reality, some bliss fades as I jump back onto the "merry-go-round" for a few more turns.

Lillian M. Beard, MD, is a clinical professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington. She is a Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board member.

We all feel it. It is not surprising that only 29% of today's pediatricians report that they are "happy" at work and 30% report "burnout"!

This report serves to identify only some of the countless ways in which we are forced to compromise the 24-hour clock, leaving too little time for ourselves and families.

We spend too many hours at work, and other data show we are undercompensated for our efforts.

Today, electronically, most of us are reachable even when out of the office. It is difficult, if not impossible, to completely disconnect. The challenge to achieve the work/life balance we have all imagined is too great!

I try to carve out "forced escapes from reality" through novels, movies, and when possible, distant travel with my spouse. However, the bliss is too short lived. When I return to reality, some bliss fades as I jump back onto the "merry-go-round" for a few more turns.

Lillian M. Beard, MD, is a clinical professor of pediatrics at George Washington University, Washington. She is a Pediatric News Editorial Advisory Board member.

Pediatricians are twice as likely to be happy outside the office than they are at work, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.

About 29% of pediatricians reported being happy at work, with dermatologists taking the top spot at 41%. Pediatricians did much better when it came to finding happiness outside the office, with 57% reporting that they were very happy when away from work, according to the Medscape report.

The biggest contributing factors to burnout in pediatricians were an overabundance of bureaucratic tasks (59%), insufficient compensation/reimbursement (37%), and spending too many hours at work (34%).

Pediatricians most commonly dealt with burnout by talking with friends/family (54%), exercising (47%), and sleeping (41%). Just over half of pediatricians reported taking 3-4 weeks of vacation, compared with 44% of all physicians; 32% took less than 3 weeks’ vacation.

About 8% of pediatricians reported that they’d contemplated suicide, but 0% reported that they’d attempted it; 85% said that they’d never thought about it. Just under one-quarter of pediatricians said that were currently seeking or planning to seek professional help for depression and/or burnout; 55% said they were not seeking help and had never made use of it in the past.

The Medscape survey was conducted from June 25 to Sept. 19, 2019, and involved 15,181 physicians.

Pediatricians are twice as likely to be happy outside the office than they are at work, according to Medscape’s 2020 Lifestyle, Happiness, and Burnout Report.