User login

Unnecessary pelvic exams, Pap tests common in young women

according to estimates from a study published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Approximately 2.6 million young women – about a quarter of those in this age group – reported receiving a pelvic exam in the previous year even though fewer than 10% were pregnant or receiving treatment for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) at the time.

Similarly, an estimated three in four Pap tests given to women aged 15-20 years likely were unnecessary. Based on Medicare payments for screening Pap tests and pelvic exams, the unnecessary procedures represented an estimated $123 million in a year.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recognizes that no evidence supports routine speculum examination or BPE in healthy, asymptomatic women younger than 21 years and recommends that these examinations be performed only when medically indicated,” said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues.

“Our results showed that, despite the recommendation, many young women without discernible medical indication received potentially unnecessary BPE or Pap tests, which may be a reflection of a long-standing clinical practice in the United States.”

These findings “demonstrate what happens to vulnerable populations (in this case, girls and young women) when clinicians do not keep up with or do not adhere to new guidelines,” Melissa A. Simon, MD, MPH, wrote in an invited commentary. She acknowledged the challenges of keeping up with new guidelines but noted the potential for harm from unnecessary screening. Dr. Simon is vice chair for clinical research in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The researchers analyzed responses from 3,410 young women aged 15-20 years in the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) during 2011-2017 and extrapolated the results to estimate nationwide statistics. The researchers found that 23% of young women – 2.6 million in the United States – had received a bimanual pelvic exam during the previous year.

“This analysis focused on the bimanual component of the pelvic examination because it is the most invasive of the pelvic examination components and less likely to be confused with a speculum examination for cervical cancer or STI screening,” the authors note.

More than half of these pelvic exams (54%) – an estimated 1.4 million exams – potentially were unnecessary. The authors classified these pelvic exams as potentially unnecessary if it was not indicated for pregnancy, intrauterine device (IUD) use, or STI treatment in the past 12 months or for another medical problem.

Among the respondents, 5% were pregnant, 22% had been tested for an STI, and 5% had been treated for an STI during the previous year. About a third of respondents (33%) had used at least one type of hormonal contraception besides an IUD in the past year, but only 2% had used an IUD.

Dr. Simon said that some have advocated for routine bimanual pelvic exams to prompt women to see their provider every year, but without evidence to support the practice.

“In fact, many women (younger and older) associate the bimanual pelvic and speculum examinations with fear, anxiety, embarrassment, discomfort, and pain,” Dr. Simon emphasized. “Girls and women with a history of sexual violence may be more vulnerable to these harms. In addition, adolescent girls may delay starting contraception use or obtaining screening for sexually transmitted infections because of fear of pelvic examination, which thus creates unnecessary barriers to obtaining important screening and family-planning methods.”

The researchers also found that 19% of young women, about 2.2 million, had received a Pap test in the previous year. The majority of these (72%) likely were unnecessary, they wrote, explaining that cervical cancer screening is not recommended for those younger than 21 years unless they are HIV positive and sexually active.

“Because HIV infection status is not available in the NSFG, we estimated prevalence of Pap tests performed as part of a routine examination and considered them potentially unnecessary,” the authors explained.

Young women were seven times more likely to have undergone a bimanual pelvic exam if they received a Pap test (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR], 7.12). In fact, the authors reported that nearly all potentially unnecessary bimanual pelvic exams (98%) occurred during the same visit as a Pap test that was potentially unnecessary as well.

Young women also were more likely to receive a bimanual pelvic exam if they underwent STI testing or used any hormonal contraception besides an IUD (aPR, 1.6 and 1.31, respectively). Those with public insurance or no insurance were less likely to receive a pelvic exam compared with those who had private insurance, although no associations were found with race/ethnicity.

Young women were about four times more likely to have a Pap test if they had STI testing (aPR, 3.77). Odds of a Pap test also were greater among those aged 18-20 years (aPR, 1.54), those with a pregnancy (aPR, 2.31), those with an IUD (aPR, 1.54), and those using any non-IUD hormonal contraception (aPR, 1.75).

Staying up to date on current guidelines and consistently delivering evidence-based care according to those guidelines “is not easy,” Dr. Simon commented. It involves building and maintaining a trusting clinician-patient relationship that centers on shared decision making, keeping up with research, and “unlearn[ing] deeply ingrained practices,” which is difficult.

“Clinicians are not well instructed on how to pivot or unlearn a practice,” Dr. Simon continued. “The science of deimplementation, especially with respect to guideline-concordant care, is in its infancy.” She also noted the value of annual visits, even without routine pelvic exams.

“Rethinking the goals of the annual health examination for young women and learning to unlearn will not put anyone out of business,” Dr. Simon concluded. “Rather, change can increase patients’ connectivity, trust, and engagement with primary care clinicians and, most importantly, avoid harms, especially to those who are most vulnerable.”

No external funding was used. The study authors and Dr. Simon have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Qin J et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5727.

An earlier version of this story appeared on Medscape.com.

A call for shared decision making

The experts who wrote American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ clinical guideline on the pelvic exam (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;132[4]:e174-80) reviewed available evidence and found insufficient evidence to support routine screening for asymptomatic nonpregnant women who have no increased risk for specific gynecologic conditions (e.g., history of gynecologic cancer). Hence, ACOG recommends routine screening based on a shared decision between the asymptomatic woman and her doctor keeping in mind her medical and family history and her preference. This decision should be made after reviewing the limitations of the exam with regard to insufficient evidence to support its accuracy in screening for ovarian cancer, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and genital herpes, plus lack of evidence for other gynecologic conditions.

In addition, we physicians must educate women, especially vulnerable populations, that deferring a pelvic exam for asymptomatic women entails judicious care. Deferring an exam does not mean that we are withholding medical care. If she wants an exam, understanding its limitations, then this preference is an indication itself for the exam as stated in our guideline.

It is important to emphasize to patients that we are deferring Pap smears until age 21 years per ACOG and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and that there is no need for a pelvic exam for sexually transmitted infection screening per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Likewise, there is no need for a pelvic exam prior initiation of contraception except for intrauterine device insertion also according to the CDC.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH , is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She was asked to comment on the Qin et al. article. Dr. Cansino is a coauthor of the ACOG 2018 guideline on the utility of pelvic exam. She also is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board. She reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A call for shared decision making

The experts who wrote American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ clinical guideline on the pelvic exam (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;132[4]:e174-80) reviewed available evidence and found insufficient evidence to support routine screening for asymptomatic nonpregnant women who have no increased risk for specific gynecologic conditions (e.g., history of gynecologic cancer). Hence, ACOG recommends routine screening based on a shared decision between the asymptomatic woman and her doctor keeping in mind her medical and family history and her preference. This decision should be made after reviewing the limitations of the exam with regard to insufficient evidence to support its accuracy in screening for ovarian cancer, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and genital herpes, plus lack of evidence for other gynecologic conditions.

In addition, we physicians must educate women, especially vulnerable populations, that deferring a pelvic exam for asymptomatic women entails judicious care. Deferring an exam does not mean that we are withholding medical care. If she wants an exam, understanding its limitations, then this preference is an indication itself for the exam as stated in our guideline.

It is important to emphasize to patients that we are deferring Pap smears until age 21 years per ACOG and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and that there is no need for a pelvic exam for sexually transmitted infection screening per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Likewise, there is no need for a pelvic exam prior initiation of contraception except for intrauterine device insertion also according to the CDC.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH , is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She was asked to comment on the Qin et al. article. Dr. Cansino is a coauthor of the ACOG 2018 guideline on the utility of pelvic exam. She also is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board. She reported no relevant financial disclosures.

A call for shared decision making

The experts who wrote American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ clinical guideline on the pelvic exam (Obstet Gynecol. 2018 Oct;132[4]:e174-80) reviewed available evidence and found insufficient evidence to support routine screening for asymptomatic nonpregnant women who have no increased risk for specific gynecologic conditions (e.g., history of gynecologic cancer). Hence, ACOG recommends routine screening based on a shared decision between the asymptomatic woman and her doctor keeping in mind her medical and family history and her preference. This decision should be made after reviewing the limitations of the exam with regard to insufficient evidence to support its accuracy in screening for ovarian cancer, bacterial vaginosis, trichomoniasis, and genital herpes, plus lack of evidence for other gynecologic conditions.

In addition, we physicians must educate women, especially vulnerable populations, that deferring a pelvic exam for asymptomatic women entails judicious care. Deferring an exam does not mean that we are withholding medical care. If she wants an exam, understanding its limitations, then this preference is an indication itself for the exam as stated in our guideline.

It is important to emphasize to patients that we are deferring Pap smears until age 21 years per ACOG and the American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology, and that there is no need for a pelvic exam for sexually transmitted infection screening per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Likewise, there is no need for a pelvic exam prior initiation of contraception except for intrauterine device insertion also according to the CDC.

Catherine Cansino, MD, MPH , is associate clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of California, Davis. She was asked to comment on the Qin et al. article. Dr. Cansino is a coauthor of the ACOG 2018 guideline on the utility of pelvic exam. She also is a member of the Ob.Gyn. News editorial advisory board. She reported no relevant financial disclosures.

according to estimates from a study published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Approximately 2.6 million young women – about a quarter of those in this age group – reported receiving a pelvic exam in the previous year even though fewer than 10% were pregnant or receiving treatment for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) at the time.

Similarly, an estimated three in four Pap tests given to women aged 15-20 years likely were unnecessary. Based on Medicare payments for screening Pap tests and pelvic exams, the unnecessary procedures represented an estimated $123 million in a year.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recognizes that no evidence supports routine speculum examination or BPE in healthy, asymptomatic women younger than 21 years and recommends that these examinations be performed only when medically indicated,” said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues.

“Our results showed that, despite the recommendation, many young women without discernible medical indication received potentially unnecessary BPE or Pap tests, which may be a reflection of a long-standing clinical practice in the United States.”

These findings “demonstrate what happens to vulnerable populations (in this case, girls and young women) when clinicians do not keep up with or do not adhere to new guidelines,” Melissa A. Simon, MD, MPH, wrote in an invited commentary. She acknowledged the challenges of keeping up with new guidelines but noted the potential for harm from unnecessary screening. Dr. Simon is vice chair for clinical research in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The researchers analyzed responses from 3,410 young women aged 15-20 years in the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) during 2011-2017 and extrapolated the results to estimate nationwide statistics. The researchers found that 23% of young women – 2.6 million in the United States – had received a bimanual pelvic exam during the previous year.

“This analysis focused on the bimanual component of the pelvic examination because it is the most invasive of the pelvic examination components and less likely to be confused with a speculum examination for cervical cancer or STI screening,” the authors note.

More than half of these pelvic exams (54%) – an estimated 1.4 million exams – potentially were unnecessary. The authors classified these pelvic exams as potentially unnecessary if it was not indicated for pregnancy, intrauterine device (IUD) use, or STI treatment in the past 12 months or for another medical problem.

Among the respondents, 5% were pregnant, 22% had been tested for an STI, and 5% had been treated for an STI during the previous year. About a third of respondents (33%) had used at least one type of hormonal contraception besides an IUD in the past year, but only 2% had used an IUD.

Dr. Simon said that some have advocated for routine bimanual pelvic exams to prompt women to see their provider every year, but without evidence to support the practice.

“In fact, many women (younger and older) associate the bimanual pelvic and speculum examinations with fear, anxiety, embarrassment, discomfort, and pain,” Dr. Simon emphasized. “Girls and women with a history of sexual violence may be more vulnerable to these harms. In addition, adolescent girls may delay starting contraception use or obtaining screening for sexually transmitted infections because of fear of pelvic examination, which thus creates unnecessary barriers to obtaining important screening and family-planning methods.”

The researchers also found that 19% of young women, about 2.2 million, had received a Pap test in the previous year. The majority of these (72%) likely were unnecessary, they wrote, explaining that cervical cancer screening is not recommended for those younger than 21 years unless they are HIV positive and sexually active.

“Because HIV infection status is not available in the NSFG, we estimated prevalence of Pap tests performed as part of a routine examination and considered them potentially unnecessary,” the authors explained.

Young women were seven times more likely to have undergone a bimanual pelvic exam if they received a Pap test (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR], 7.12). In fact, the authors reported that nearly all potentially unnecessary bimanual pelvic exams (98%) occurred during the same visit as a Pap test that was potentially unnecessary as well.

Young women also were more likely to receive a bimanual pelvic exam if they underwent STI testing or used any hormonal contraception besides an IUD (aPR, 1.6 and 1.31, respectively). Those with public insurance or no insurance were less likely to receive a pelvic exam compared with those who had private insurance, although no associations were found with race/ethnicity.

Young women were about four times more likely to have a Pap test if they had STI testing (aPR, 3.77). Odds of a Pap test also were greater among those aged 18-20 years (aPR, 1.54), those with a pregnancy (aPR, 2.31), those with an IUD (aPR, 1.54), and those using any non-IUD hormonal contraception (aPR, 1.75).

Staying up to date on current guidelines and consistently delivering evidence-based care according to those guidelines “is not easy,” Dr. Simon commented. It involves building and maintaining a trusting clinician-patient relationship that centers on shared decision making, keeping up with research, and “unlearn[ing] deeply ingrained practices,” which is difficult.

“Clinicians are not well instructed on how to pivot or unlearn a practice,” Dr. Simon continued. “The science of deimplementation, especially with respect to guideline-concordant care, is in its infancy.” She also noted the value of annual visits, even without routine pelvic exams.

“Rethinking the goals of the annual health examination for young women and learning to unlearn will not put anyone out of business,” Dr. Simon concluded. “Rather, change can increase patients’ connectivity, trust, and engagement with primary care clinicians and, most importantly, avoid harms, especially to those who are most vulnerable.”

No external funding was used. The study authors and Dr. Simon have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Qin J et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5727.

An earlier version of this story appeared on Medscape.com.

according to estimates from a study published online in JAMA Internal Medicine.

Approximately 2.6 million young women – about a quarter of those in this age group – reported receiving a pelvic exam in the previous year even though fewer than 10% were pregnant or receiving treatment for a sexually transmitted infection (STI) at the time.

Similarly, an estimated three in four Pap tests given to women aged 15-20 years likely were unnecessary. Based on Medicare payments for screening Pap tests and pelvic exams, the unnecessary procedures represented an estimated $123 million in a year.

“The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recognizes that no evidence supports routine speculum examination or BPE in healthy, asymptomatic women younger than 21 years and recommends that these examinations be performed only when medically indicated,” said Jin Qin, ScD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and colleagues.

“Our results showed that, despite the recommendation, many young women without discernible medical indication received potentially unnecessary BPE or Pap tests, which may be a reflection of a long-standing clinical practice in the United States.”

These findings “demonstrate what happens to vulnerable populations (in this case, girls and young women) when clinicians do not keep up with or do not adhere to new guidelines,” Melissa A. Simon, MD, MPH, wrote in an invited commentary. She acknowledged the challenges of keeping up with new guidelines but noted the potential for harm from unnecessary screening. Dr. Simon is vice chair for clinical research in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

The researchers analyzed responses from 3,410 young women aged 15-20 years in the National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) during 2011-2017 and extrapolated the results to estimate nationwide statistics. The researchers found that 23% of young women – 2.6 million in the United States – had received a bimanual pelvic exam during the previous year.

“This analysis focused on the bimanual component of the pelvic examination because it is the most invasive of the pelvic examination components and less likely to be confused with a speculum examination for cervical cancer or STI screening,” the authors note.

More than half of these pelvic exams (54%) – an estimated 1.4 million exams – potentially were unnecessary. The authors classified these pelvic exams as potentially unnecessary if it was not indicated for pregnancy, intrauterine device (IUD) use, or STI treatment in the past 12 months or for another medical problem.

Among the respondents, 5% were pregnant, 22% had been tested for an STI, and 5% had been treated for an STI during the previous year. About a third of respondents (33%) had used at least one type of hormonal contraception besides an IUD in the past year, but only 2% had used an IUD.

Dr. Simon said that some have advocated for routine bimanual pelvic exams to prompt women to see their provider every year, but without evidence to support the practice.

“In fact, many women (younger and older) associate the bimanual pelvic and speculum examinations with fear, anxiety, embarrassment, discomfort, and pain,” Dr. Simon emphasized. “Girls and women with a history of sexual violence may be more vulnerable to these harms. In addition, adolescent girls may delay starting contraception use or obtaining screening for sexually transmitted infections because of fear of pelvic examination, which thus creates unnecessary barriers to obtaining important screening and family-planning methods.”

The researchers also found that 19% of young women, about 2.2 million, had received a Pap test in the previous year. The majority of these (72%) likely were unnecessary, they wrote, explaining that cervical cancer screening is not recommended for those younger than 21 years unless they are HIV positive and sexually active.

“Because HIV infection status is not available in the NSFG, we estimated prevalence of Pap tests performed as part of a routine examination and considered them potentially unnecessary,” the authors explained.

Young women were seven times more likely to have undergone a bimanual pelvic exam if they received a Pap test (adjusted prevalence ratio [aPR], 7.12). In fact, the authors reported that nearly all potentially unnecessary bimanual pelvic exams (98%) occurred during the same visit as a Pap test that was potentially unnecessary as well.

Young women also were more likely to receive a bimanual pelvic exam if they underwent STI testing or used any hormonal contraception besides an IUD (aPR, 1.6 and 1.31, respectively). Those with public insurance or no insurance were less likely to receive a pelvic exam compared with those who had private insurance, although no associations were found with race/ethnicity.

Young women were about four times more likely to have a Pap test if they had STI testing (aPR, 3.77). Odds of a Pap test also were greater among those aged 18-20 years (aPR, 1.54), those with a pregnancy (aPR, 2.31), those with an IUD (aPR, 1.54), and those using any non-IUD hormonal contraception (aPR, 1.75).

Staying up to date on current guidelines and consistently delivering evidence-based care according to those guidelines “is not easy,” Dr. Simon commented. It involves building and maintaining a trusting clinician-patient relationship that centers on shared decision making, keeping up with research, and “unlearn[ing] deeply ingrained practices,” which is difficult.

“Clinicians are not well instructed on how to pivot or unlearn a practice,” Dr. Simon continued. “The science of deimplementation, especially with respect to guideline-concordant care, is in its infancy.” She also noted the value of annual visits, even without routine pelvic exams.

“Rethinking the goals of the annual health examination for young women and learning to unlearn will not put anyone out of business,” Dr. Simon concluded. “Rather, change can increase patients’ connectivity, trust, and engagement with primary care clinicians and, most importantly, avoid harms, especially to those who are most vulnerable.”

No external funding was used. The study authors and Dr. Simon have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Qin J et al. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Jan 6. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.5727.

An earlier version of this story appeared on Medscape.com.

Pediatricians take on more mental health care

Assessment and treatment of many of the more common behavioral disorders in childhood, such as ADHD and anxiety, should be considered within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, a stance made very clear by a recent policy statement published by the American Academy of Pediatrics entitled “Mental health competencies for pediatric practice.”1 These competencies include medication treatment. As stated in the article, “certain disorders (ADHD, common anxiety disorders, depression), if associated with no more than moderate impairment, are amenable to primary care medication management because there are indicated medications with a well-established safety profile.”

This shift to shared ownership when it comes to mental health care is likely coming from multiple sources, not the least of them being necessity and an acknowledgment that there simply aren’t enough psychiatrists to take over the mental health care of every youth with a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. While the number of child and adolescent psychiatrists remains relatively flat, the youth suicide rate is rising, as are the numbers presenting to emergency departments in crisis – all for reasons still to be fully understood. And these trends all are occurring as the medical community overall is appreciating more and more that good mental health is a cornerstone of all health.

The response from the pediatric community, whether it be because of personal conviction or simply a lack of options, largely has been to step up to the plate and take on these new responsibilities and challenges while trying to get up to speed with the latest information about mental health best practices. From my own experience doing evaluations and consultations from area primary care clinicians for over 15 years, the shift is noticeable. The typical patient now coming in has already seen a mental health counselor and tried at least one medication, while evaluations for diagnosis and treatment recommendations for things like uncomplicated and treatment-naive ADHD symptoms, for example, are becoming much more infrequent – although still far from extinct.

Nevertheless, there remain concerns about the extent of these new charges. Joe Nasca, MD, an experienced pediatrician who has been practicing in rural Vermont for decades, is worried that there is simply too much already for pediatricians to know and do to be able to add extensive mental health care. “There is so much to know in general peds [pediatrics] that I would guess a year or more of additional residency and experience would adequately prepare me to take this on,” he said in an interview. In comparing psychiatric care to other specialties, Dr. Nasca went on to say that, “I would not presume to treat chronic renal failure without the help of a nephrologist or a dilated aortic arch without a cardiologist.”

In a similar vein, however, it also is true that a significant percentage of children presenting to pediatricians for orthopedic problems, infections, asthma, and rashes are managed without referrals to specialists. The right balance, of course, will vary from clinician to clinician based on that pediatrician’s level of interest, experience, and available resources in the community. The AAP position papers don’t mandate or even encourage the notion that all pediatricians need to be at the same place when it comes to competency in assessment and treatment of mental health problems, although it is probably fair to say that there is a push for the pediatric community as a whole to raise the collective bar at least a notch or two.

In response, the mental health community has moved to support the primary care community in their expanded role. These efforts have taken many forms, most notably the model of integrated care, in which mental health clinicians of various types see patients in primary care offices rather than making patients come to them. There also are new consultation programs that provide easy access to a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional for case-related questions delivered by phone, email, or for single in-person consultations. Additional training and educational offerings also are now available for pediatricians either in training and for those already in practice. These initiatives are bolstered by research showing that, not only can good mental health care be delivered in pediatric settings, but there are cost savings that can be realized, particularly for nonpsychiatric medical care.2 Despite these promising leads, however, there will remain some for whom anything less than the increased availability of a psychiatrist to “take over” a patient’s mental health care will be seen as a falling short of the clinical need.

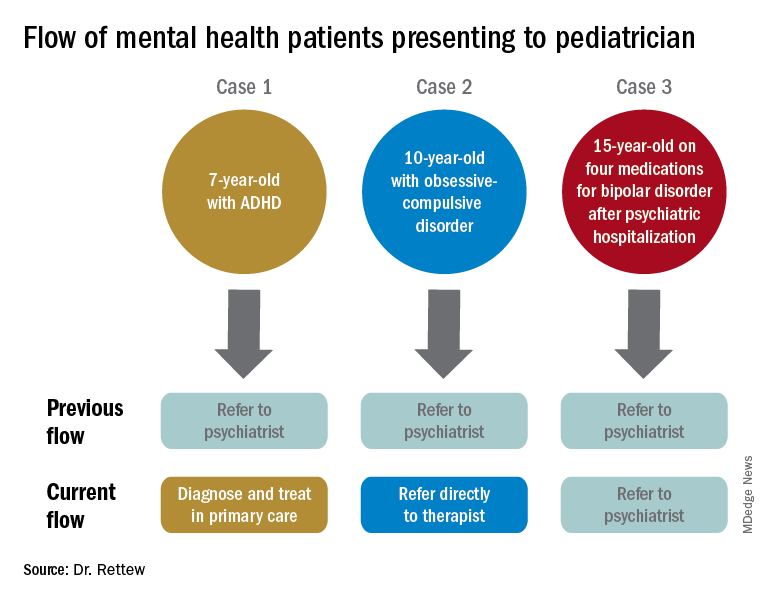

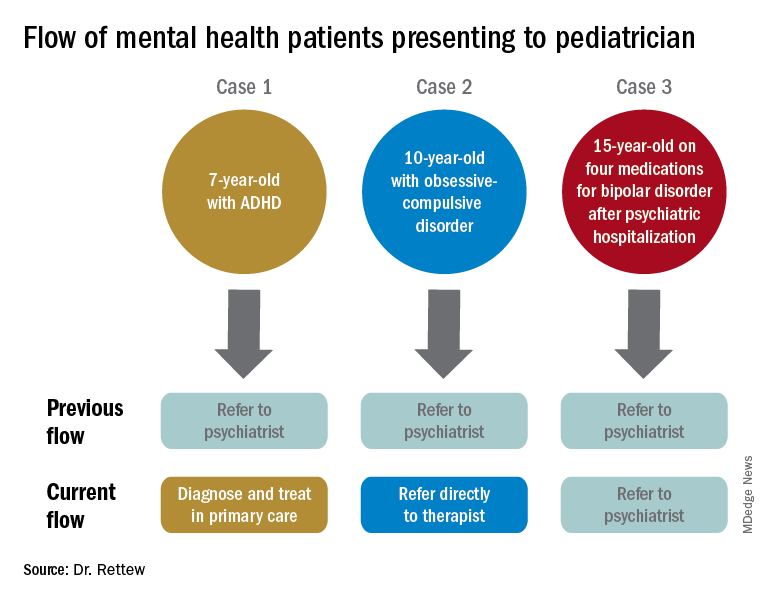

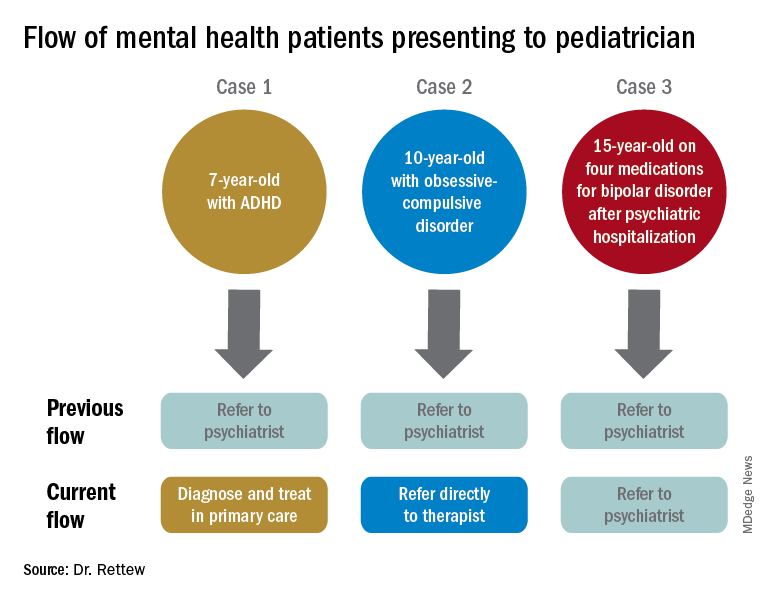

To illustrate how things have and continue to change, consider the following three common clinical scenarios that generally present to a pediatrician:

- New presentation of ADHD symptoms.

- Anxiety or obsessive-compulsive problems.

- Return of a patient who has been psychiatrically hospitalized and now is taking multiple medications.

In the past, all three cases often would have resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist. Today, however, it is quite likely that only one of these cases would be referred because ADHD could be well diagnosed and managed within the primary care setting, and problems like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder are sent first not to a psychiatrist but to a non-MD psychotherapist.

Moving forward, today’s pediatricians are expected to do more for the mental health care of patients themselves instead of referring to a psychiatrist. Most already do, despite having had little in the way of formal training. As the evidence grows that the promotion of mental well-being can be a key to future overall health, as well as to the cost of future health care, there are many reasons to be optimistic that support for pediatricians and collaborative care models for clinicians trying to fulfill these new responsibilities will get only stronger.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov;144(5). pii: e20192757.

2. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul;144(1). pii: e20183243.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 14th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington on May 8, 2020 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Assessment and treatment of many of the more common behavioral disorders in childhood, such as ADHD and anxiety, should be considered within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, a stance made very clear by a recent policy statement published by the American Academy of Pediatrics entitled “Mental health competencies for pediatric practice.”1 These competencies include medication treatment. As stated in the article, “certain disorders (ADHD, common anxiety disorders, depression), if associated with no more than moderate impairment, are amenable to primary care medication management because there are indicated medications with a well-established safety profile.”

This shift to shared ownership when it comes to mental health care is likely coming from multiple sources, not the least of them being necessity and an acknowledgment that there simply aren’t enough psychiatrists to take over the mental health care of every youth with a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. While the number of child and adolescent psychiatrists remains relatively flat, the youth suicide rate is rising, as are the numbers presenting to emergency departments in crisis – all for reasons still to be fully understood. And these trends all are occurring as the medical community overall is appreciating more and more that good mental health is a cornerstone of all health.

The response from the pediatric community, whether it be because of personal conviction or simply a lack of options, largely has been to step up to the plate and take on these new responsibilities and challenges while trying to get up to speed with the latest information about mental health best practices. From my own experience doing evaluations and consultations from area primary care clinicians for over 15 years, the shift is noticeable. The typical patient now coming in has already seen a mental health counselor and tried at least one medication, while evaluations for diagnosis and treatment recommendations for things like uncomplicated and treatment-naive ADHD symptoms, for example, are becoming much more infrequent – although still far from extinct.

Nevertheless, there remain concerns about the extent of these new charges. Joe Nasca, MD, an experienced pediatrician who has been practicing in rural Vermont for decades, is worried that there is simply too much already for pediatricians to know and do to be able to add extensive mental health care. “There is so much to know in general peds [pediatrics] that I would guess a year or more of additional residency and experience would adequately prepare me to take this on,” he said in an interview. In comparing psychiatric care to other specialties, Dr. Nasca went on to say that, “I would not presume to treat chronic renal failure without the help of a nephrologist or a dilated aortic arch without a cardiologist.”

In a similar vein, however, it also is true that a significant percentage of children presenting to pediatricians for orthopedic problems, infections, asthma, and rashes are managed without referrals to specialists. The right balance, of course, will vary from clinician to clinician based on that pediatrician’s level of interest, experience, and available resources in the community. The AAP position papers don’t mandate or even encourage the notion that all pediatricians need to be at the same place when it comes to competency in assessment and treatment of mental health problems, although it is probably fair to say that there is a push for the pediatric community as a whole to raise the collective bar at least a notch or two.

In response, the mental health community has moved to support the primary care community in their expanded role. These efforts have taken many forms, most notably the model of integrated care, in which mental health clinicians of various types see patients in primary care offices rather than making patients come to them. There also are new consultation programs that provide easy access to a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional for case-related questions delivered by phone, email, or for single in-person consultations. Additional training and educational offerings also are now available for pediatricians either in training and for those already in practice. These initiatives are bolstered by research showing that, not only can good mental health care be delivered in pediatric settings, but there are cost savings that can be realized, particularly for nonpsychiatric medical care.2 Despite these promising leads, however, there will remain some for whom anything less than the increased availability of a psychiatrist to “take over” a patient’s mental health care will be seen as a falling short of the clinical need.

To illustrate how things have and continue to change, consider the following three common clinical scenarios that generally present to a pediatrician:

- New presentation of ADHD symptoms.

- Anxiety or obsessive-compulsive problems.

- Return of a patient who has been psychiatrically hospitalized and now is taking multiple medications.

In the past, all three cases often would have resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist. Today, however, it is quite likely that only one of these cases would be referred because ADHD could be well diagnosed and managed within the primary care setting, and problems like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder are sent first not to a psychiatrist but to a non-MD psychotherapist.

Moving forward, today’s pediatricians are expected to do more for the mental health care of patients themselves instead of referring to a psychiatrist. Most already do, despite having had little in the way of formal training. As the evidence grows that the promotion of mental well-being can be a key to future overall health, as well as to the cost of future health care, there are many reasons to be optimistic that support for pediatricians and collaborative care models for clinicians trying to fulfill these new responsibilities will get only stronger.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov;144(5). pii: e20192757.

2. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul;144(1). pii: e20183243.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 14th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington on May 8, 2020 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Assessment and treatment of many of the more common behavioral disorders in childhood, such as ADHD and anxiety, should be considered within a pediatrician’s scope of practice, a stance made very clear by a recent policy statement published by the American Academy of Pediatrics entitled “Mental health competencies for pediatric practice.”1 These competencies include medication treatment. As stated in the article, “certain disorders (ADHD, common anxiety disorders, depression), if associated with no more than moderate impairment, are amenable to primary care medication management because there are indicated medications with a well-established safety profile.”

This shift to shared ownership when it comes to mental health care is likely coming from multiple sources, not the least of them being necessity and an acknowledgment that there simply aren’t enough psychiatrists to take over the mental health care of every youth with a diagnosable psychiatric disorder. While the number of child and adolescent psychiatrists remains relatively flat, the youth suicide rate is rising, as are the numbers presenting to emergency departments in crisis – all for reasons still to be fully understood. And these trends all are occurring as the medical community overall is appreciating more and more that good mental health is a cornerstone of all health.

The response from the pediatric community, whether it be because of personal conviction or simply a lack of options, largely has been to step up to the plate and take on these new responsibilities and challenges while trying to get up to speed with the latest information about mental health best practices. From my own experience doing evaluations and consultations from area primary care clinicians for over 15 years, the shift is noticeable. The typical patient now coming in has already seen a mental health counselor and tried at least one medication, while evaluations for diagnosis and treatment recommendations for things like uncomplicated and treatment-naive ADHD symptoms, for example, are becoming much more infrequent – although still far from extinct.

Nevertheless, there remain concerns about the extent of these new charges. Joe Nasca, MD, an experienced pediatrician who has been practicing in rural Vermont for decades, is worried that there is simply too much already for pediatricians to know and do to be able to add extensive mental health care. “There is so much to know in general peds [pediatrics] that I would guess a year or more of additional residency and experience would adequately prepare me to take this on,” he said in an interview. In comparing psychiatric care to other specialties, Dr. Nasca went on to say that, “I would not presume to treat chronic renal failure without the help of a nephrologist or a dilated aortic arch without a cardiologist.”

In a similar vein, however, it also is true that a significant percentage of children presenting to pediatricians for orthopedic problems, infections, asthma, and rashes are managed without referrals to specialists. The right balance, of course, will vary from clinician to clinician based on that pediatrician’s level of interest, experience, and available resources in the community. The AAP position papers don’t mandate or even encourage the notion that all pediatricians need to be at the same place when it comes to competency in assessment and treatment of mental health problems, although it is probably fair to say that there is a push for the pediatric community as a whole to raise the collective bar at least a notch or two.

In response, the mental health community has moved to support the primary care community in their expanded role. These efforts have taken many forms, most notably the model of integrated care, in which mental health clinicians of various types see patients in primary care offices rather than making patients come to them. There also are new consultation programs that provide easy access to a child psychiatrist or other mental health professional for case-related questions delivered by phone, email, or for single in-person consultations. Additional training and educational offerings also are now available for pediatricians either in training and for those already in practice. These initiatives are bolstered by research showing that, not only can good mental health care be delivered in pediatric settings, but there are cost savings that can be realized, particularly for nonpsychiatric medical care.2 Despite these promising leads, however, there will remain some for whom anything less than the increased availability of a psychiatrist to “take over” a patient’s mental health care will be seen as a falling short of the clinical need.

To illustrate how things have and continue to change, consider the following three common clinical scenarios that generally present to a pediatrician:

- New presentation of ADHD symptoms.

- Anxiety or obsessive-compulsive problems.

- Return of a patient who has been psychiatrically hospitalized and now is taking multiple medications.

In the past, all three cases often would have resulted in a referral to a psychiatrist. Today, however, it is quite likely that only one of these cases would be referred because ADHD could be well diagnosed and managed within the primary care setting, and problems like anxiety and obsessive-compulsive disorder are sent first not to a psychiatrist but to a non-MD psychotherapist.

Moving forward, today’s pediatricians are expected to do more for the mental health care of patients themselves instead of referring to a psychiatrist. Most already do, despite having had little in the way of formal training. As the evidence grows that the promotion of mental well-being can be a key to future overall health, as well as to the cost of future health care, there are many reasons to be optimistic that support for pediatricians and collaborative care models for clinicians trying to fulfill these new responsibilities will get only stronger.

References

1. Pediatrics. 2019 Nov;144(5). pii: e20192757.

2. Pediatrics. 2019 Jul;144(1). pii: e20183243.

Dr. Rettew is a child and adolescent psychiatrist and associate professor of psychiatry and pediatrics at the University of Vermont, Burlington. Follow him on Twitter @PediPsych. Email him at pdnews@mdedge.com. Looking for more mental health training? Attend the 14th annual Child Psychiatry in Primary Care conference in Burlington on May 8, 2020 (http://www.med.uvm.edu/cme/conferences).

Standards for health claims in advertisements need to go up

Three months is how long I’ll leave a magazine out in my waiting room. When its lobby lifespan is up, I’ll usually recycle it, though sometimes will take it home to read myself when I have down time.

Leafing through an accumulated pile of them over the recent holiday break, I was struck by how many carry ads for questionable “cures”: magnetic bracelets for headaches, copper-based topical creams that claim to cure diabetic neuropathy. Another was from a company with something that looks like a standard tanning bed advertising that it has special lights to “alternatively treat cancer.”

How on Earth is this legal?

Seriously. Since college I’ve been through 4 years of medical school, another 5 combined of residency and fellowship, and now 21 years of frontline neurology experience. And if, after all that, I were to start marketing such horse hockey as a cure for anything (besides my wallet), I’d be hounded by the Food and Drug Administration and state board and probably driven out of practice.

Yet, people with no “real” (science-based) medical treatment experience are free to market this stuff to a public who, for the most part, don’t have the training, knowledge, or experience to know it’s a crock.

I’m sure some of the people selling this stuff really believe they’re helping. Admittedly, there are a lot of things we don’t know in medicine. But anything that’s making such claims should have real evidence – like a large double-blind, placebo-controlled trial – behind it. Not anecdotal reports, small uncontrolled trials, and patient testimonials. The placebo effect is remarkably strong.

There are also some selling this stuff who are less than scrupulous. They’ll claim to have good intentions, but are well aware they’re bilking people – often desperate – out of their savings. They’re no better than the doctors who make headlines for Medicare and insurance fraud by performing unnecessary surgeries and billing for medications that weren’t given.

Either way, the point is the same. Unproven treatments are just that – unproven – and shouldn’t be marketed as effective ones. If it works, let the evidence prove it. But if it doesn’t, no one should be promoting it to anyone, regardless of how long (and where) they went to school.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Three months is how long I’ll leave a magazine out in my waiting room. When its lobby lifespan is up, I’ll usually recycle it, though sometimes will take it home to read myself when I have down time.

Leafing through an accumulated pile of them over the recent holiday break, I was struck by how many carry ads for questionable “cures”: magnetic bracelets for headaches, copper-based topical creams that claim to cure diabetic neuropathy. Another was from a company with something that looks like a standard tanning bed advertising that it has special lights to “alternatively treat cancer.”

How on Earth is this legal?

Seriously. Since college I’ve been through 4 years of medical school, another 5 combined of residency and fellowship, and now 21 years of frontline neurology experience. And if, after all that, I were to start marketing such horse hockey as a cure for anything (besides my wallet), I’d be hounded by the Food and Drug Administration and state board and probably driven out of practice.

Yet, people with no “real” (science-based) medical treatment experience are free to market this stuff to a public who, for the most part, don’t have the training, knowledge, or experience to know it’s a crock.

I’m sure some of the people selling this stuff really believe they’re helping. Admittedly, there are a lot of things we don’t know in medicine. But anything that’s making such claims should have real evidence – like a large double-blind, placebo-controlled trial – behind it. Not anecdotal reports, small uncontrolled trials, and patient testimonials. The placebo effect is remarkably strong.

There are also some selling this stuff who are less than scrupulous. They’ll claim to have good intentions, but are well aware they’re bilking people – often desperate – out of their savings. They’re no better than the doctors who make headlines for Medicare and insurance fraud by performing unnecessary surgeries and billing for medications that weren’t given.

Either way, the point is the same. Unproven treatments are just that – unproven – and shouldn’t be marketed as effective ones. If it works, let the evidence prove it. But if it doesn’t, no one should be promoting it to anyone, regardless of how long (and where) they went to school.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Three months is how long I’ll leave a magazine out in my waiting room. When its lobby lifespan is up, I’ll usually recycle it, though sometimes will take it home to read myself when I have down time.

Leafing through an accumulated pile of them over the recent holiday break, I was struck by how many carry ads for questionable “cures”: magnetic bracelets for headaches, copper-based topical creams that claim to cure diabetic neuropathy. Another was from a company with something that looks like a standard tanning bed advertising that it has special lights to “alternatively treat cancer.”

How on Earth is this legal?

Seriously. Since college I’ve been through 4 years of medical school, another 5 combined of residency and fellowship, and now 21 years of frontline neurology experience. And if, after all that, I were to start marketing such horse hockey as a cure for anything (besides my wallet), I’d be hounded by the Food and Drug Administration and state board and probably driven out of practice.

Yet, people with no “real” (science-based) medical treatment experience are free to market this stuff to a public who, for the most part, don’t have the training, knowledge, or experience to know it’s a crock.

I’m sure some of the people selling this stuff really believe they’re helping. Admittedly, there are a lot of things we don’t know in medicine. But anything that’s making such claims should have real evidence – like a large double-blind, placebo-controlled trial – behind it. Not anecdotal reports, small uncontrolled trials, and patient testimonials. The placebo effect is remarkably strong.

There are also some selling this stuff who are less than scrupulous. They’ll claim to have good intentions, but are well aware they’re bilking people – often desperate – out of their savings. They’re no better than the doctors who make headlines for Medicare and insurance fraud by performing unnecessary surgeries and billing for medications that weren’t given.

Either way, the point is the same. Unproven treatments are just that – unproven – and shouldn’t be marketed as effective ones. If it works, let the evidence prove it. But if it doesn’t, no one should be promoting it to anyone, regardless of how long (and where) they went to school.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Letter to the Editor

Editor’s note: This is one of the many emails readers sent to Dermatology News in response to Dr. Alan Rockoff’s last “Under My Skin” column in the December issue.

Dr. Rockoff,

I was deeply heartbroken to read that this would be your last column in Dermatology News today. I am a medical dermatologist with 19 years of experience in a small town in North Carolina and have always looked forward to reading your columns. No matter what the topic for the article you chose, I would always glean something worthwhile from it, be it a poignant insight, a relevant practice tip on treatment or patient management, and nearly always a hearty laugh.

Being somewhat rural and without a lot of competition, my very busy practice consists mainly of salt of the earth patients needing straight dermatologic care, mostly skin cancer, psoriasis, acne, the general stuff. Your ability to capture the essence of what it is like to be one of us in the trenches, to expose and eloquently define the most common and frustrating issues we face, has been a source of pleasure for years. On more than one occasion, I put down the magazine and attempted to write a thank you letter for one article or another you wrote, to say that you are doing a great job and please continue to enlighten us with your insight and that your efforts are greatly valued. I am embarrassed to admit, I never could complete those emails, thinking “Why bother the man? He is clearly as busy as me, and why would he want to hear from me anyway?”

Well, at the risk of bothering you, sir, please do accept my apologies for not writing you before you retired your article, and please know that your articles have personally given me years of immense happiness. They will be sorely missed, and likely not ever replaced.

With gratitude,

Jeff Suchniak, MD

Rocky Mount, N.C.

Editor’s note: This is one of the many emails readers sent to Dermatology News in response to Dr. Alan Rockoff’s last “Under My Skin” column in the December issue.

Dr. Rockoff,

I was deeply heartbroken to read that this would be your last column in Dermatology News today. I am a medical dermatologist with 19 years of experience in a small town in North Carolina and have always looked forward to reading your columns. No matter what the topic for the article you chose, I would always glean something worthwhile from it, be it a poignant insight, a relevant practice tip on treatment or patient management, and nearly always a hearty laugh.

Being somewhat rural and without a lot of competition, my very busy practice consists mainly of salt of the earth patients needing straight dermatologic care, mostly skin cancer, psoriasis, acne, the general stuff. Your ability to capture the essence of what it is like to be one of us in the trenches, to expose and eloquently define the most common and frustrating issues we face, has been a source of pleasure for years. On more than one occasion, I put down the magazine and attempted to write a thank you letter for one article or another you wrote, to say that you are doing a great job and please continue to enlighten us with your insight and that your efforts are greatly valued. I am embarrassed to admit, I never could complete those emails, thinking “Why bother the man? He is clearly as busy as me, and why would he want to hear from me anyway?”

Well, at the risk of bothering you, sir, please do accept my apologies for not writing you before you retired your article, and please know that your articles have personally given me years of immense happiness. They will be sorely missed, and likely not ever replaced.

With gratitude,

Jeff Suchniak, MD

Rocky Mount, N.C.

Editor’s note: This is one of the many emails readers sent to Dermatology News in response to Dr. Alan Rockoff’s last “Under My Skin” column in the December issue.

Dr. Rockoff,

I was deeply heartbroken to read that this would be your last column in Dermatology News today. I am a medical dermatologist with 19 years of experience in a small town in North Carolina and have always looked forward to reading your columns. No matter what the topic for the article you chose, I would always glean something worthwhile from it, be it a poignant insight, a relevant practice tip on treatment or patient management, and nearly always a hearty laugh.

Being somewhat rural and without a lot of competition, my very busy practice consists mainly of salt of the earth patients needing straight dermatologic care, mostly skin cancer, psoriasis, acne, the general stuff. Your ability to capture the essence of what it is like to be one of us in the trenches, to expose and eloquently define the most common and frustrating issues we face, has been a source of pleasure for years. On more than one occasion, I put down the magazine and attempted to write a thank you letter for one article or another you wrote, to say that you are doing a great job and please continue to enlighten us with your insight and that your efforts are greatly valued. I am embarrassed to admit, I never could complete those emails, thinking “Why bother the man? He is clearly as busy as me, and why would he want to hear from me anyway?”

Well, at the risk of bothering you, sir, please do accept my apologies for not writing you before you retired your article, and please know that your articles have personally given me years of immense happiness. They will be sorely missed, and likely not ever replaced.

With gratitude,

Jeff Suchniak, MD

Rocky Mount, N.C.

Big practices outpace small ones in Medicare pay bonuses

More physician practices are earning positive payments under Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, but smaller practices won’t fare quite as well as larger ones in 2020.

Under the Quality Payment Program, 97% of MIPS-eligible clinicians are scheduled to receive an incentive payment this year, based on meeting performance criteria in 2018. That’s up five percentage points from the 2017 performance year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported Jan. 6. But 2% of clinicians will see a negative adjustment for not having met those criteria.

Among small practices, however, the rate of MIPS-eligible clinicians earning a positive payment adjustment in 2020 is about 84%. While lower than the overall rate, that’s still a 10 percentage point improvement from the previous performance year. But 13% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in small practices face a negative adjustment.

The bonus rate among rural practices mirrors the national rate, with more than 97% of rural practices eligible to receive a bonus in 2020. In 2019, 93% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in rural settings received a positive adjustment.

More small and rural practices will see positive payment adjustments in 2020, compared with 2019, CMS Administrator Seema Verma said. “This shows we are making strides toward making MIPS a practical program for every clinician, regardless of size.”

While most clinicians earned a positive adjustment, Ms. Verma acknowledged that the dollar value of the adjustment remains relatively small.

For clinicians who met the exceptional performance criteria for 2020 based on work in 2018, the maximum adjustment will be 1.68%. For those who failed to meet the exceptional performance threshold, the maximum positive adjustment will be 0.2%. The range of negative payment adjustments will be between –0.01% and –5%.

Those positive payment adjustments are modest in part because adjustments overall must be budget neutral, Ms. Verma explained. But CMS expects that to change in future years. As the program matures, increased performance thresholds will shrink distribution of positive payment adjustments for high-performing clinicians. That will lead to larger positive payment adjustments for those who do earn them.

More physician practices are earning positive payments under Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, but smaller practices won’t fare quite as well as larger ones in 2020.

Under the Quality Payment Program, 97% of MIPS-eligible clinicians are scheduled to receive an incentive payment this year, based on meeting performance criteria in 2018. That’s up five percentage points from the 2017 performance year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported Jan. 6. But 2% of clinicians will see a negative adjustment for not having met those criteria.

Among small practices, however, the rate of MIPS-eligible clinicians earning a positive payment adjustment in 2020 is about 84%. While lower than the overall rate, that’s still a 10 percentage point improvement from the previous performance year. But 13% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in small practices face a negative adjustment.

The bonus rate among rural practices mirrors the national rate, with more than 97% of rural practices eligible to receive a bonus in 2020. In 2019, 93% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in rural settings received a positive adjustment.

More small and rural practices will see positive payment adjustments in 2020, compared with 2019, CMS Administrator Seema Verma said. “This shows we are making strides toward making MIPS a practical program for every clinician, regardless of size.”

While most clinicians earned a positive adjustment, Ms. Verma acknowledged that the dollar value of the adjustment remains relatively small.

For clinicians who met the exceptional performance criteria for 2020 based on work in 2018, the maximum adjustment will be 1.68%. For those who failed to meet the exceptional performance threshold, the maximum positive adjustment will be 0.2%. The range of negative payment adjustments will be between –0.01% and –5%.

Those positive payment adjustments are modest in part because adjustments overall must be budget neutral, Ms. Verma explained. But CMS expects that to change in future years. As the program matures, increased performance thresholds will shrink distribution of positive payment adjustments for high-performing clinicians. That will lead to larger positive payment adjustments for those who do earn them.

More physician practices are earning positive payments under Medicare’s Merit-Based Incentive Payment System, but smaller practices won’t fare quite as well as larger ones in 2020.

Under the Quality Payment Program, 97% of MIPS-eligible clinicians are scheduled to receive an incentive payment this year, based on meeting performance criteria in 2018. That’s up five percentage points from the 2017 performance year, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported Jan. 6. But 2% of clinicians will see a negative adjustment for not having met those criteria.

Among small practices, however, the rate of MIPS-eligible clinicians earning a positive payment adjustment in 2020 is about 84%. While lower than the overall rate, that’s still a 10 percentage point improvement from the previous performance year. But 13% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in small practices face a negative adjustment.

The bonus rate among rural practices mirrors the national rate, with more than 97% of rural practices eligible to receive a bonus in 2020. In 2019, 93% of MIPS-eligible clinicians in rural settings received a positive adjustment.

More small and rural practices will see positive payment adjustments in 2020, compared with 2019, CMS Administrator Seema Verma said. “This shows we are making strides toward making MIPS a practical program for every clinician, regardless of size.”

While most clinicians earned a positive adjustment, Ms. Verma acknowledged that the dollar value of the adjustment remains relatively small.

For clinicians who met the exceptional performance criteria for 2020 based on work in 2018, the maximum adjustment will be 1.68%. For those who failed to meet the exceptional performance threshold, the maximum positive adjustment will be 0.2%. The range of negative payment adjustments will be between –0.01% and –5%.

Those positive payment adjustments are modest in part because adjustments overall must be budget neutral, Ms. Verma explained. But CMS expects that to change in future years. As the program matures, increased performance thresholds will shrink distribution of positive payment adjustments for high-performing clinicians. That will lead to larger positive payment adjustments for those who do earn them.

Beware the dangers of nerve injury in vaginal surgery

LAS VEGAS – a pelvic surgeon urged colleagues.

“It’s a very high medical and legal risk. You have to think about the various nerves that can be influenced,” urogynecologist Mickey M. Karram, MD, said at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

Dr. Karram, director of urogynecology and reconstructive surgery at the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati and clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Cincinnati, offered these pearls:

- Understand the anatomy of nerves at risk. These include the ilioinguinal nerve, obturator neurovascular bundle, and pudendal nerve.

- Position the patient correctly. The buttocks should be at edge of table, Dr. Karram said, and there should be slight extension and lateral rotation of the thigh. Beware of compression of the lateral knee.

- Avoid compression from stirrups. If you still use candy-cane stirrups, he said, you can get compression along the lateral aspect of the knee. “You can [get] common perineal nerve injuries. You can also get femoral nerve injuries that are stretch injuries and over-extension injuries as well. Just be careful about this.” Dr. Karram said he prefers fin-type stirrups such as the Allen Yellofin brand. Also, he said, avoid compression injuries that result when there are too many people between the patient’s legs and someone leans on the thighs, he said.

- Free the retractor in abdominal procedures. “If you’re operating abdominally and use retractors, free the retractor at times,” he said. Otherwise, “you can get injuries to the genitofemoral nerve and the femoral nerve itself.”

- Beware buttock pain after sacrospinous fixation. “About 15%-20% of the time, you’ll get extreme buttock pain,” Dr. Karram said. “Assuming the buttock pain doesn’t radiate anywhere and doesn’t go down the leg, it’s definitely not a problem. If it goes down the leg, then you have to think about things like deligating pretty quickly.”

Dr. Karram disclosed consulting (Coloplast and Cynosure/Hologic) and speaker (Allergan, Astellas, Coloplast, and Cynosure/Hologic) relationships. He has royalties from Fidelis Medical and LumeNXT.

This meeting was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

LAS VEGAS – a pelvic surgeon urged colleagues.

“It’s a very high medical and legal risk. You have to think about the various nerves that can be influenced,” urogynecologist Mickey M. Karram, MD, said at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

Dr. Karram, director of urogynecology and reconstructive surgery at the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati and clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Cincinnati, offered these pearls:

- Understand the anatomy of nerves at risk. These include the ilioinguinal nerve, obturator neurovascular bundle, and pudendal nerve.

- Position the patient correctly. The buttocks should be at edge of table, Dr. Karram said, and there should be slight extension and lateral rotation of the thigh. Beware of compression of the lateral knee.

- Avoid compression from stirrups. If you still use candy-cane stirrups, he said, you can get compression along the lateral aspect of the knee. “You can [get] common perineal nerve injuries. You can also get femoral nerve injuries that are stretch injuries and over-extension injuries as well. Just be careful about this.” Dr. Karram said he prefers fin-type stirrups such as the Allen Yellofin brand. Also, he said, avoid compression injuries that result when there are too many people between the patient’s legs and someone leans on the thighs, he said.

- Free the retractor in abdominal procedures. “If you’re operating abdominally and use retractors, free the retractor at times,” he said. Otherwise, “you can get injuries to the genitofemoral nerve and the femoral nerve itself.”

- Beware buttock pain after sacrospinous fixation. “About 15%-20% of the time, you’ll get extreme buttock pain,” Dr. Karram said. “Assuming the buttock pain doesn’t radiate anywhere and doesn’t go down the leg, it’s definitely not a problem. If it goes down the leg, then you have to think about things like deligating pretty quickly.”

Dr. Karram disclosed consulting (Coloplast and Cynosure/Hologic) and speaker (Allergan, Astellas, Coloplast, and Cynosure/Hologic) relationships. He has royalties from Fidelis Medical and LumeNXT.

This meeting was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

LAS VEGAS – a pelvic surgeon urged colleagues.

“It’s a very high medical and legal risk. You have to think about the various nerves that can be influenced,” urogynecologist Mickey M. Karram, MD, said at the Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery Symposium.

Dr. Karram, director of urogynecology and reconstructive surgery at the Christ Hospital in Cincinnati and clinical professor of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Cincinnati, offered these pearls:

- Understand the anatomy of nerves at risk. These include the ilioinguinal nerve, obturator neurovascular bundle, and pudendal nerve.

- Position the patient correctly. The buttocks should be at edge of table, Dr. Karram said, and there should be slight extension and lateral rotation of the thigh. Beware of compression of the lateral knee.

- Avoid compression from stirrups. If you still use candy-cane stirrups, he said, you can get compression along the lateral aspect of the knee. “You can [get] common perineal nerve injuries. You can also get femoral nerve injuries that are stretch injuries and over-extension injuries as well. Just be careful about this.” Dr. Karram said he prefers fin-type stirrups such as the Allen Yellofin brand. Also, he said, avoid compression injuries that result when there are too many people between the patient’s legs and someone leans on the thighs, he said.

- Free the retractor in abdominal procedures. “If you’re operating abdominally and use retractors, free the retractor at times,” he said. Otherwise, “you can get injuries to the genitofemoral nerve and the femoral nerve itself.”

- Beware buttock pain after sacrospinous fixation. “About 15%-20% of the time, you’ll get extreme buttock pain,” Dr. Karram said. “Assuming the buttock pain doesn’t radiate anywhere and doesn’t go down the leg, it’s definitely not a problem. If it goes down the leg, then you have to think about things like deligating pretty quickly.”

Dr. Karram disclosed consulting (Coloplast and Cynosure/Hologic) and speaker (Allergan, Astellas, Coloplast, and Cynosure/Hologic) relationships. He has royalties from Fidelis Medical and LumeNXT.

This meeting was jointly provided by Global Academy for Medical Education and the University of Cincinnati. Global Academy and this news organization are owned by the same company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM PAGS 2019

Using Democratic Deliberation to Engage Veterans in Complex Policy Making for the Veterans Health Administration

Providing high-quality, patient-centered health care is a top priority for the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veteran Health Administration (VHA), whose core mission is to improve the health and well-being of US veterans. Thus, news of long wait times for medical appointments in the VHA sparked intense national attention and debate and led to changes in senior management and legislative action. 1 On August 8, 2014, President Bara c k Obama signed the Veterans Access, Choice, and Accountability Act of 2014, also known as the Choice Act, which provided an additional $16 billion in emergency spending over 3 years to improve veterans’ access to timely health care. 2 The Choice Act sought to develop an integrated health care network that allowed qualified VHA patients to receive specific health care services in their communities delivered by non-VHA health care providers (HCPs) but paid for by the VHA. The Choice Act also laid out explicit criteria for how to prioritize who would be eligible for VHA-purchased civilian care: (1) veterans who could not get timely appointments at a VHA medical facility within 30 days of referral; or (2) veterans who lived > 40 miles from the closest VHA medical facility.

VHA decision makers seeking to improve care delivery also need to weigh trade-offs between alternative approaches to providing rapid access. For instance, increasing access to non-VHA HCPs may not always decrease wait times and could result in loss of continuity, limited care coordination, limited ability to ensure and enforce high-quality standards at the VHA, and other challenges.3-6 Although the concerns and views of elected representatives, advocacy groups, and health system leaders are important, it is unknown whether these views and preferences align with those of veterans. Arguably, the range of views and concerns of informed veterans whose health is at stake should be particularly prominent in such policy decision making.

To identify the considerations that were most important to veterans regarding VHA policy around decreasing wait times, a study was designed to engage a group of veterans who were eligible for civilian care under the Choice Act. The study took place 1 year after the Choice Act was passed. Veterans were asked to focus on 2 related questions: First, how should funding be used for building VHA capacity (build) vs purchasing civilian care (buy)? Second, under what circumstances should civilian care be prioritized?

The aim of this paper is to describe democratic deliberation (DD), a specific method that engaged veteran patients in complex policy decisions around access to care. DD methods have been used increasingly in health care for developing policy guidance, setting priorities, providing advice on ethical dilemmas, weighing risk-benefit trade-offs, and determining decision-making authority.7-12 For example, DD helped guide national policy for mammography screening for breast cancer in New Zealand.13 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality has completed a systematic review and a large, randomized experiment on best practices for carrying out public deliberation.8,13,14 However, despite the potential value of this approach, there has been little use of deliberative methods within the VHA for the explicit purpose of informing veteran health care delivery.

This paper describes the experience engaging veterans by using DD methodology and informing VHA leadership about the results of those deliberations. The specific aims were to understand whether DD is an acceptable approach to use to engage patients in the medical services policy-making process within VHA and whether veterans are able to come to an informed consensus.

Methods

Engaging patients and incorporating their needs and concerns within the policy-making process may improve health system policies and make those policies more patient centered. Such engagement also could be a way to generate creative solutions. However, because health-system decisions often involve making difficult trade-offs, effectively obtaining patient population input on complex care delivery issues can be challenging.

Although surveys can provide intuitive, top-of-mind input from respondents, these opinions are generally not sufficient for resolving complex problems.15 Focus groups and interviews may produce results that are more in-depth than surveys, but these methods tend to elicit settled private preferences rather than opinions about what the community should do.16 DD, on the other hand, is designed to elicit deeply informed public opinions on complex, value-laden topics to develop recommendations and policies for a larger community.17 The goal is to find collective solutions to challenging social problems. DD achieves this by giving participants an opportunity to explore a topic in-depth, question experts, and engage peers in reason-based discussions.18,19 This method has its roots in political science and has been used over several decades to successfully inform policy making on a broad array of topics nationally and internationally—from health research ethics in the US to nuclear and energy policy in Japan.7,16,20,21 DD has been found to promote ownership of public programs and lend legitimacy to policy decisions, political institutions, and democracy itself.18

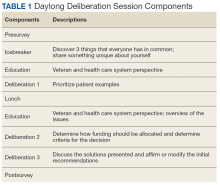

A single day (8 hours) DD session was convened, following a Citizens Jury model of deliberation, which brings veteran patients together to learn about a topic, ask questions of experts, deliberate with peers, and generate a “citizen’s report” that contains a set of recommendations (Table 1). An overview of the different models of DD and rationale for each can be found elsewhere.8,15

Recruitment Considerations

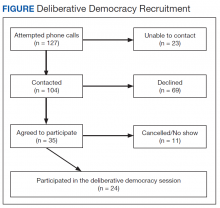

A purposively selected sample of civilian care-eligible veterans from a midwestern VHA health care system (1 medical center and 3 community-based outpatient clinics [CBOCs]) were invited to the DD session. The targeted number of participants was 30. Female veterans, who comprise only 7% of the local veteran population, were oversampled to account for their potentially different health care needs and to create balance between males and females in the session. Oversampling for other characteristics was not possible due to the relatively small sample size. Based on prior experience,7 it was assumed that 70% of willing participants would attend the session; therefore 34 veterans were invited and 24 attended. Each participant received a $200 incentive in appreciation for their substantial time commitment and to offset transportation costs.

Background Materials

A packet with educational materials (Flesch-Kincaid Grade Level of 10.5) was mailed to participants about 2 weeks before the DD session. Participants were asked to review prior to attending the session. These materials described the session (eg, purpose, organizers, importance) and provided factual information about the Choice Act (eg, eligibility, out-of-pocket costs, travel pay, prescription drug policies).

Session Overview