User login

Most charity assistance programs do not cover prescriptions for uninsured patients

Almost all of the patient assistance programs funded by independent charities for subsidizing prescription medications exclude patients without insurance, a cross-sectional analysis has shown.

Of 274 patient assistance programs analyzed from six independent charities, 267 (97%) listed insurance coverage as an eligibility requirement for their program, according to So-Yeon Kang, MPH, MBA, a PhD student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

Out-of-pocket prescription costs for Medicare Part D plans can cost “thousands of dollars” because of higher coinsurance rates and no catastrophic cap on the program, the researchers noted in JAMA.

“For this reason, independent charity foundations offering patient assistance programs to these patients are entitled to receive tax-deductible donations from pharmaceutical companies,” they wrote. “However, the findings from this study suggest that several features of the programs may limit their usefulness to financially needy patients and bolster the use of expensive drugs.”

The researchers examined the 274 patient assistance programs funded by the CancerCare Co-Payment Assistance Foundation, Good Days, the HealthWell Foundation, the Patient Access Network Foundation, Patient Advocate Foundation Co-Pay Relief, and Patient Services Incorporated. Copayment assistance alone was provided by 168 programs, 90 programs offered assistance with copayments and health insurance premiums, and 9 programs provided assistance to subsidize health insurance premiums only.

Cancer or cancer-related treatments were covered by 41% of programs, and 34% provided assistance for genetic or rare diseases.

In 2017, the six charities spent an average of 86% of their revenue on patient expenditures: They had a total revenue of between $24 million and $532 million, while the expenditures for patient assistance ranged from $24 million and $353 million. With regard to eligibility, the income limit that was most common was 500% of the federal poverty level.

The researchers also studied which of 18 drugs were covered by assistance programs. They found that Of the 18 drugs studied, 12 drugs (67%) were in protected classes and therefore covered by Medicare Part D. Prescription drugs that were covered were more likely to be expensive, compared with drugs that were not covered (median annual cost of $1,157, versus $367).

The researchers noted several limitations of the study, such the inability to correlate the programs with drug spending, assuming that generic substitution was always possible. In addition, the analysis of drug use was limited to two charity foundations.

In a related editorial, Katherine L. Kraschel and Gregory D. Curfman, MD, wrote that some patient assistance programs might be violating federal law.

“Coupled with recent enforcement activity by the Department of Justice, the data reported by Kang et al. suggest that some programs may warrant continued regulatory scrutiny and enforcement,” wrote Ms. Kraschel, executive director of the Solomon Center for Health Law & Policy at Yale University Law School, New Haven, Conn., and Dr. Curfman, deputy editor of JAMA in Chicago (JAMA. 2019;322[5]:405-6).

In addition, the Office of Inspector General created a special advisory bulletin in 2014 that clarifies how pharmaceutical companies should comply with the Anti-Kickback Statute within a patient assistance program. This guidance states that pharmaceutical companies should make assistance available to all products, rather than simply high-cost or specialty drugs, which pharmaceutical companies have not consistently followed, Ms. Kraschel and Dr. Curfman explained.

To help patients and the health care system, the authors recommended the Office of the Inspector General implement stronger restrictions for pharmaceutical companies contributing to patient assistance programs and develop reporting requirements for transparency purposes.

“The extent to which patient assistance programs violate tax exemption standards that prohibit private benefit that does not further its charitable purpose and is intentionally aimed to benefit the pharmaceutical companies warrants further scrutiny,” Ms. Kraschel and Dr. Curfman wrote. “It is particularly egregious that the payments made from pharmaceutical companies to patient assistance programs may be illegal yet simultaneously tax deductible.”

The study was funded by Arnold Ventures. The authors of the study and the editorial reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kang S-Y et al. JAMA. 2019;322(5):422-9.

Almost all of the patient assistance programs funded by independent charities for subsidizing prescription medications exclude patients without insurance, a cross-sectional analysis has shown.

Of 274 patient assistance programs analyzed from six independent charities, 267 (97%) listed insurance coverage as an eligibility requirement for their program, according to So-Yeon Kang, MPH, MBA, a PhD student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

Out-of-pocket prescription costs for Medicare Part D plans can cost “thousands of dollars” because of higher coinsurance rates and no catastrophic cap on the program, the researchers noted in JAMA.

“For this reason, independent charity foundations offering patient assistance programs to these patients are entitled to receive tax-deductible donations from pharmaceutical companies,” they wrote. “However, the findings from this study suggest that several features of the programs may limit their usefulness to financially needy patients and bolster the use of expensive drugs.”

The researchers examined the 274 patient assistance programs funded by the CancerCare Co-Payment Assistance Foundation, Good Days, the HealthWell Foundation, the Patient Access Network Foundation, Patient Advocate Foundation Co-Pay Relief, and Patient Services Incorporated. Copayment assistance alone was provided by 168 programs, 90 programs offered assistance with copayments and health insurance premiums, and 9 programs provided assistance to subsidize health insurance premiums only.

Cancer or cancer-related treatments were covered by 41% of programs, and 34% provided assistance for genetic or rare diseases.

In 2017, the six charities spent an average of 86% of their revenue on patient expenditures: They had a total revenue of between $24 million and $532 million, while the expenditures for patient assistance ranged from $24 million and $353 million. With regard to eligibility, the income limit that was most common was 500% of the federal poverty level.

The researchers also studied which of 18 drugs were covered by assistance programs. They found that Of the 18 drugs studied, 12 drugs (67%) were in protected classes and therefore covered by Medicare Part D. Prescription drugs that were covered were more likely to be expensive, compared with drugs that were not covered (median annual cost of $1,157, versus $367).

The researchers noted several limitations of the study, such the inability to correlate the programs with drug spending, assuming that generic substitution was always possible. In addition, the analysis of drug use was limited to two charity foundations.

In a related editorial, Katherine L. Kraschel and Gregory D. Curfman, MD, wrote that some patient assistance programs might be violating federal law.

“Coupled with recent enforcement activity by the Department of Justice, the data reported by Kang et al. suggest that some programs may warrant continued regulatory scrutiny and enforcement,” wrote Ms. Kraschel, executive director of the Solomon Center for Health Law & Policy at Yale University Law School, New Haven, Conn., and Dr. Curfman, deputy editor of JAMA in Chicago (JAMA. 2019;322[5]:405-6).

In addition, the Office of Inspector General created a special advisory bulletin in 2014 that clarifies how pharmaceutical companies should comply with the Anti-Kickback Statute within a patient assistance program. This guidance states that pharmaceutical companies should make assistance available to all products, rather than simply high-cost or specialty drugs, which pharmaceutical companies have not consistently followed, Ms. Kraschel and Dr. Curfman explained.

To help patients and the health care system, the authors recommended the Office of the Inspector General implement stronger restrictions for pharmaceutical companies contributing to patient assistance programs and develop reporting requirements for transparency purposes.

“The extent to which patient assistance programs violate tax exemption standards that prohibit private benefit that does not further its charitable purpose and is intentionally aimed to benefit the pharmaceutical companies warrants further scrutiny,” Ms. Kraschel and Dr. Curfman wrote. “It is particularly egregious that the payments made from pharmaceutical companies to patient assistance programs may be illegal yet simultaneously tax deductible.”

The study was funded by Arnold Ventures. The authors of the study and the editorial reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kang S-Y et al. JAMA. 2019;322(5):422-9.

Almost all of the patient assistance programs funded by independent charities for subsidizing prescription medications exclude patients without insurance, a cross-sectional analysis has shown.

Of 274 patient assistance programs analyzed from six independent charities, 267 (97%) listed insurance coverage as an eligibility requirement for their program, according to So-Yeon Kang, MPH, MBA, a PhD student at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, and colleagues.

Out-of-pocket prescription costs for Medicare Part D plans can cost “thousands of dollars” because of higher coinsurance rates and no catastrophic cap on the program, the researchers noted in JAMA.

“For this reason, independent charity foundations offering patient assistance programs to these patients are entitled to receive tax-deductible donations from pharmaceutical companies,” they wrote. “However, the findings from this study suggest that several features of the programs may limit their usefulness to financially needy patients and bolster the use of expensive drugs.”

The researchers examined the 274 patient assistance programs funded by the CancerCare Co-Payment Assistance Foundation, Good Days, the HealthWell Foundation, the Patient Access Network Foundation, Patient Advocate Foundation Co-Pay Relief, and Patient Services Incorporated. Copayment assistance alone was provided by 168 programs, 90 programs offered assistance with copayments and health insurance premiums, and 9 programs provided assistance to subsidize health insurance premiums only.

Cancer or cancer-related treatments were covered by 41% of programs, and 34% provided assistance for genetic or rare diseases.

In 2017, the six charities spent an average of 86% of their revenue on patient expenditures: They had a total revenue of between $24 million and $532 million, while the expenditures for patient assistance ranged from $24 million and $353 million. With regard to eligibility, the income limit that was most common was 500% of the federal poverty level.

The researchers also studied which of 18 drugs were covered by assistance programs. They found that Of the 18 drugs studied, 12 drugs (67%) were in protected classes and therefore covered by Medicare Part D. Prescription drugs that were covered were more likely to be expensive, compared with drugs that were not covered (median annual cost of $1,157, versus $367).

The researchers noted several limitations of the study, such the inability to correlate the programs with drug spending, assuming that generic substitution was always possible. In addition, the analysis of drug use was limited to two charity foundations.

In a related editorial, Katherine L. Kraschel and Gregory D. Curfman, MD, wrote that some patient assistance programs might be violating federal law.

“Coupled with recent enforcement activity by the Department of Justice, the data reported by Kang et al. suggest that some programs may warrant continued regulatory scrutiny and enforcement,” wrote Ms. Kraschel, executive director of the Solomon Center for Health Law & Policy at Yale University Law School, New Haven, Conn., and Dr. Curfman, deputy editor of JAMA in Chicago (JAMA. 2019;322[5]:405-6).

In addition, the Office of Inspector General created a special advisory bulletin in 2014 that clarifies how pharmaceutical companies should comply with the Anti-Kickback Statute within a patient assistance program. This guidance states that pharmaceutical companies should make assistance available to all products, rather than simply high-cost or specialty drugs, which pharmaceutical companies have not consistently followed, Ms. Kraschel and Dr. Curfman explained.

To help patients and the health care system, the authors recommended the Office of the Inspector General implement stronger restrictions for pharmaceutical companies contributing to patient assistance programs and develop reporting requirements for transparency purposes.

“The extent to which patient assistance programs violate tax exemption standards that prohibit private benefit that does not further its charitable purpose and is intentionally aimed to benefit the pharmaceutical companies warrants further scrutiny,” Ms. Kraschel and Dr. Curfman wrote. “It is particularly egregious that the payments made from pharmaceutical companies to patient assistance programs may be illegal yet simultaneously tax deductible.”

The study was funded by Arnold Ventures. The authors of the study and the editorial reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Kang S-Y et al. JAMA. 2019;322(5):422-9.

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Nearly all patient assistance programs do not provide help with prescription costs for patients without insurance.

Major finding: Of 274 assistance programs examined, 267 programs (97%) list insurance coverage as a requirement for eligibility, and those programs were more likely to cover off-patent, brand-name drugs than generic versions.

Study details: A cross-sectional study of 274 patient assistance programs funded by six independent charities in 2018.

Disclosures: This study was funded by Arnold Ventures. The authors reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Source: Kang S-Y et al. JAMA. 2019;322(5):422-9.

Finding the right job

. There is some useful material pertaining to this topic on the American Academy of Dermatology website, which I helped develop. This should help you decide whether you want to go solo, small group, large group, VA, or academic practice. These options all have certain advantages and drawbacks.

Your first decision should be where you want to practice geographically, which will determine many of the details of any practice situation. For instance, if you go where there is a shortage of dermatologists, you will be more welcome and more sought after. I will never forget sitting in a hospital break room in New York City after giving grand rounds with a large group of residents, who asked me about practice opportunities. I asked them where they wanted to practice. Every resident – first, second, and third year – indicated they wanted to stay in New York City. I had to laugh to myself. If there are any cities with a surplus of dermatologists, it’s the hip ones: New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Miami, and so on. If you can find a job there, it will be a “this is what everyone signs” contract situation, and a large part of your pay is the privilege of living in an urban “paradise.”

If you are willing to look further afield, I suggest you start with an old classic, the “Places Rated Almanac: The Classic Guide for Finding Your Best Places to Live in America” (Washington: Places Rated Books, 2007). This is a resource (that needs a new edition) that provides all kinds of details on different areas of the country that you may not have considered, including median income, schools, climate, and livability.

When you know the general area where you would like to settle – and after considering the parents, the in-laws, and the outlaws – remember that the best jobs are not advertised. You should contact all the dermatology, multispeciality, and hospital groups in the area (yes, write them a nice snail mail letter) indicating you are interested, and ask them if they are hiring. Practices are usually interested in a general dermatologist, or perhaps a Mohs surgeon or dermatopathologist, willing to practice general dermatology half time. For example, I know a very nice general dermatology practice in the Midwest that has been looking for the right derm-path/general derm for years. The days of strolling in and setting up an all-Mohs or all-dermpath practice are over, unless you buy out, or become employed by one of the older established specialist groups.

Ask the staff (and former physician employees if you can find them) lots of questions. See if their style of medicine suits you. See if their electronic health record system is fast or a major hindrance. Find out how many extenders you will be responsible for supervising.

And find out if they are considering selling out (selling you) to private equity. Private equity groups are a major new influence on the specialty, run a lot of ads, and hire a lot of graduating dermatologists. They offer more benefits and higher initial salaries. There is no free lunch, however, and these perks must be paid back with future earnings. The private equity groups take 20%-30% of profits “off the top” and your earnings will hit a ceiling at a level that is significantly lower than it would be in a solo practice or dermatology group. They also have long, detailed, ferocious contracts with penalty clauses and noncompetes from all outlets. More numerous advertisements are a negative tip off, but will give you an idea of which markets they think are promising with regard to need and payer mix. See what the private equity group’s private health insurance rates are. If they are significantly greater than Medicare rates, they deserve a second look, though few are. Remember that the senior physician who pitches for them in the lounge doesn’t work for free, but receives a significant bonus for getting you to sign.

If you find a great location, it is time for contract review. The first rule is that no contract is better than who you sign it with. If they are determined to mistreat you, they will – no matter the contract. I advise always having a graceful exit written into the contract specifying severance terms (if any), even if you never need this.

If you are ready to work hard and make more income, you should forgo the perks and go on a percentage of collections basis. If you are considering a place where they very much need dermatologists (sorry, not New York City), you may have some negotiating room and it is worth spending a few thousand dollars to ask a medical contract attorney to go over the contract for you, or even negotiate for you. Don’t overestimate your value, however, because you might negotiate your way right out of a job. The expanding scope of nurse practitioners and physician assistants have taken away much of your indispensability. While there is a shortage of dermatologists in most of the United States, there generally is no shortage of dermatology appointments.

When you start a new job you are not certain about, resist the urge to buy a big house and put down roots right away. You may need to move on if it doesn’t work out. You may want to work a few years, pay down school loans, save a little, and set up your own practice somewhere.

All things considered, these are exciting times and being a board-certified dermatologist is a wonderful place to be in the medical world. I am not at all sure if any of the proposed end-of-the-world health care plans will come true. And let me know if you are one of those New York City residents who struck out for the western frontier. Us fly-over-country folk have got to stick together!

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

. There is some useful material pertaining to this topic on the American Academy of Dermatology website, which I helped develop. This should help you decide whether you want to go solo, small group, large group, VA, or academic practice. These options all have certain advantages and drawbacks.

Your first decision should be where you want to practice geographically, which will determine many of the details of any practice situation. For instance, if you go where there is a shortage of dermatologists, you will be more welcome and more sought after. I will never forget sitting in a hospital break room in New York City after giving grand rounds with a large group of residents, who asked me about practice opportunities. I asked them where they wanted to practice. Every resident – first, second, and third year – indicated they wanted to stay in New York City. I had to laugh to myself. If there are any cities with a surplus of dermatologists, it’s the hip ones: New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Miami, and so on. If you can find a job there, it will be a “this is what everyone signs” contract situation, and a large part of your pay is the privilege of living in an urban “paradise.”

If you are willing to look further afield, I suggest you start with an old classic, the “Places Rated Almanac: The Classic Guide for Finding Your Best Places to Live in America” (Washington: Places Rated Books, 2007). This is a resource (that needs a new edition) that provides all kinds of details on different areas of the country that you may not have considered, including median income, schools, climate, and livability.

When you know the general area where you would like to settle – and after considering the parents, the in-laws, and the outlaws – remember that the best jobs are not advertised. You should contact all the dermatology, multispeciality, and hospital groups in the area (yes, write them a nice snail mail letter) indicating you are interested, and ask them if they are hiring. Practices are usually interested in a general dermatologist, or perhaps a Mohs surgeon or dermatopathologist, willing to practice general dermatology half time. For example, I know a very nice general dermatology practice in the Midwest that has been looking for the right derm-path/general derm for years. The days of strolling in and setting up an all-Mohs or all-dermpath practice are over, unless you buy out, or become employed by one of the older established specialist groups.

Ask the staff (and former physician employees if you can find them) lots of questions. See if their style of medicine suits you. See if their electronic health record system is fast or a major hindrance. Find out how many extenders you will be responsible for supervising.

And find out if they are considering selling out (selling you) to private equity. Private equity groups are a major new influence on the specialty, run a lot of ads, and hire a lot of graduating dermatologists. They offer more benefits and higher initial salaries. There is no free lunch, however, and these perks must be paid back with future earnings. The private equity groups take 20%-30% of profits “off the top” and your earnings will hit a ceiling at a level that is significantly lower than it would be in a solo practice or dermatology group. They also have long, detailed, ferocious contracts with penalty clauses and noncompetes from all outlets. More numerous advertisements are a negative tip off, but will give you an idea of which markets they think are promising with regard to need and payer mix. See what the private equity group’s private health insurance rates are. If they are significantly greater than Medicare rates, they deserve a second look, though few are. Remember that the senior physician who pitches for them in the lounge doesn’t work for free, but receives a significant bonus for getting you to sign.

If you find a great location, it is time for contract review. The first rule is that no contract is better than who you sign it with. If they are determined to mistreat you, they will – no matter the contract. I advise always having a graceful exit written into the contract specifying severance terms (if any), even if you never need this.

If you are ready to work hard and make more income, you should forgo the perks and go on a percentage of collections basis. If you are considering a place where they very much need dermatologists (sorry, not New York City), you may have some negotiating room and it is worth spending a few thousand dollars to ask a medical contract attorney to go over the contract for you, or even negotiate for you. Don’t overestimate your value, however, because you might negotiate your way right out of a job. The expanding scope of nurse practitioners and physician assistants have taken away much of your indispensability. While there is a shortage of dermatologists in most of the United States, there generally is no shortage of dermatology appointments.

When you start a new job you are not certain about, resist the urge to buy a big house and put down roots right away. You may need to move on if it doesn’t work out. You may want to work a few years, pay down school loans, save a little, and set up your own practice somewhere.

All things considered, these are exciting times and being a board-certified dermatologist is a wonderful place to be in the medical world. I am not at all sure if any of the proposed end-of-the-world health care plans will come true. And let me know if you are one of those New York City residents who struck out for the western frontier. Us fly-over-country folk have got to stick together!

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

. There is some useful material pertaining to this topic on the American Academy of Dermatology website, which I helped develop. This should help you decide whether you want to go solo, small group, large group, VA, or academic practice. These options all have certain advantages and drawbacks.

Your first decision should be where you want to practice geographically, which will determine many of the details of any practice situation. For instance, if you go where there is a shortage of dermatologists, you will be more welcome and more sought after. I will never forget sitting in a hospital break room in New York City after giving grand rounds with a large group of residents, who asked me about practice opportunities. I asked them where they wanted to practice. Every resident – first, second, and third year – indicated they wanted to stay in New York City. I had to laugh to myself. If there are any cities with a surplus of dermatologists, it’s the hip ones: New York, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Miami, and so on. If you can find a job there, it will be a “this is what everyone signs” contract situation, and a large part of your pay is the privilege of living in an urban “paradise.”

If you are willing to look further afield, I suggest you start with an old classic, the “Places Rated Almanac: The Classic Guide for Finding Your Best Places to Live in America” (Washington: Places Rated Books, 2007). This is a resource (that needs a new edition) that provides all kinds of details on different areas of the country that you may not have considered, including median income, schools, climate, and livability.

When you know the general area where you would like to settle – and after considering the parents, the in-laws, and the outlaws – remember that the best jobs are not advertised. You should contact all the dermatology, multispeciality, and hospital groups in the area (yes, write them a nice snail mail letter) indicating you are interested, and ask them if they are hiring. Practices are usually interested in a general dermatologist, or perhaps a Mohs surgeon or dermatopathologist, willing to practice general dermatology half time. For example, I know a very nice general dermatology practice in the Midwest that has been looking for the right derm-path/general derm for years. The days of strolling in and setting up an all-Mohs or all-dermpath practice are over, unless you buy out, or become employed by one of the older established specialist groups.

Ask the staff (and former physician employees if you can find them) lots of questions. See if their style of medicine suits you. See if their electronic health record system is fast or a major hindrance. Find out how many extenders you will be responsible for supervising.

And find out if they are considering selling out (selling you) to private equity. Private equity groups are a major new influence on the specialty, run a lot of ads, and hire a lot of graduating dermatologists. They offer more benefits and higher initial salaries. There is no free lunch, however, and these perks must be paid back with future earnings. The private equity groups take 20%-30% of profits “off the top” and your earnings will hit a ceiling at a level that is significantly lower than it would be in a solo practice or dermatology group. They also have long, detailed, ferocious contracts with penalty clauses and noncompetes from all outlets. More numerous advertisements are a negative tip off, but will give you an idea of which markets they think are promising with regard to need and payer mix. See what the private equity group’s private health insurance rates are. If they are significantly greater than Medicare rates, they deserve a second look, though few are. Remember that the senior physician who pitches for them in the lounge doesn’t work for free, but receives a significant bonus for getting you to sign.

If you find a great location, it is time for contract review. The first rule is that no contract is better than who you sign it with. If they are determined to mistreat you, they will – no matter the contract. I advise always having a graceful exit written into the contract specifying severance terms (if any), even if you never need this.

If you are ready to work hard and make more income, you should forgo the perks and go on a percentage of collections basis. If you are considering a place where they very much need dermatologists (sorry, not New York City), you may have some negotiating room and it is worth spending a few thousand dollars to ask a medical contract attorney to go over the contract for you, or even negotiate for you. Don’t overestimate your value, however, because you might negotiate your way right out of a job. The expanding scope of nurse practitioners and physician assistants have taken away much of your indispensability. While there is a shortage of dermatologists in most of the United States, there generally is no shortage of dermatology appointments.

When you start a new job you are not certain about, resist the urge to buy a big house and put down roots right away. You may need to move on if it doesn’t work out. You may want to work a few years, pay down school loans, save a little, and set up your own practice somewhere.

All things considered, these are exciting times and being a board-certified dermatologist is a wonderful place to be in the medical world. I am not at all sure if any of the proposed end-of-the-world health care plans will come true. And let me know if you are one of those New York City residents who struck out for the western frontier. Us fly-over-country folk have got to stick together!

Dr. Coldiron is in private practice but maintains a clinical assistant professorship at the University of Cincinnati. He cares for patients, teaches medical students and residents, and has several active clinical research projects. Dr. Coldiron is the author of more than 80 scientific letters, papers, and several book chapters, and he speaks frequently on a variety of topics. He is a past president of the American Academy of Dermatology. Write to him at dermnews@mdedge.com.

Feds propose new price transparency rules in health care

Three federal agencies have jointly issued a price transparency proposal that would require most employer-based health plans and health insurance issuers to disclose price and cost-sharing information up front.

The goal behind the proposal is to give consumers accurate estimates about the out-of-pocket costs they may incur for medical services, giving them the opportunity to shop around for medical treatment.

“Under the status quo, health care prices are about as clear as mud to patients,” Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a statement, adding that “we are throwing open the shutters and bringing to light the price of care for American consumers. Kept secret, these prices are simply dollar amounts on a ledger; disclosed, they deliver fuel to the engines of competition among hospitals and insurers.”

The “Transparency in Coverage” proposed rule, was released online on Nov. 15 jointly by the Department of Health & Human Services, the Department of Labor, and the Department of the Treasury. If finalized, it would give consumers “real-time, personalized access to cost-sharing information, including an estimate of their cost-sharing liability for all covered health care items and services through an online tool that most group health plans and health insurance issuers would be required to make available to all of their members, and in paper form, at the consumer’s request,” a fact sheet outlining the features of the proposed rule states.

Health plans would also “be required to disclose on a public website their negotiated rates for in-network providers and allowed amounts paid for out-of-network providers,” the fact sheet continues.

The proposal comes as the CMS finalized transparency-related rules in the 2020 update to the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS). The price transparency portion of the OPPS is scheduled to go into effect on Jan. 1, 2021.

A fact sheet on the OPPS states that each hospital in the United States will be required to “establish (and update) and make public a yearly list of the hospital’s standard charges for items and services provided by the hospital.”

That list must include all standard charges, including gross charges, discounted cash prices, payer-specific negotiated charges, and deidentified minimum and maximum negotiated charges for all hospital items and services, as well as cash prices, payer-specific negotiated charges, and deidentified minimum and maximum negotiated charges for 300 shoppable services (70 identified by CMS and 230 selected by the hospital). A shoppable service is a service that can be scheduled in advance.

“This final rule and the proposed rule will bring forward the transparency we need to finally begin reducing the overall health care costs,” Ms. Verma said. “Today’s rules usher in a new era that upends the status quo to empower patients and put them first.”

America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a statement that it is evaluating the proposal and the final OPPS rule through a lens of three core principles: that consumers deserve transparency about out-of-pocket costs to help them make informed decisions; that transparency should be achieved in a way that encourages, not undermines, competitive negotiations to lower costs; and that public programs and the free market work together to deliver on our commitments to affordable, quality, and value.

“Neither of these rules, together or separately, satisfies these principles,” AHIP stated.

The Federation of American Hospitals is already anticipating a legal challenge to the rules.

“Patients should have readily available and easy-to-understand cost-sharing information when they need to make health care decisions,” FAH President and CEO Chip Kahn said in a statement. “Health care pricing transparency ought to be defined by the right information at the right time. This final regulation on hospital transparency fails to meet the definition of price transparency useful for patients. Instead, it will only result in patient overload of useless information while distorting the competitive market for purchasing hospital care.”

Mr. Kahn said FAH plans “on joining with hospitals to file a legal challenge,” asserting that CMS has exceeded it’s authority with these rules.

Three federal agencies have jointly issued a price transparency proposal that would require most employer-based health plans and health insurance issuers to disclose price and cost-sharing information up front.

The goal behind the proposal is to give consumers accurate estimates about the out-of-pocket costs they may incur for medical services, giving them the opportunity to shop around for medical treatment.

“Under the status quo, health care prices are about as clear as mud to patients,” Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a statement, adding that “we are throwing open the shutters and bringing to light the price of care for American consumers. Kept secret, these prices are simply dollar amounts on a ledger; disclosed, they deliver fuel to the engines of competition among hospitals and insurers.”

The “Transparency in Coverage” proposed rule, was released online on Nov. 15 jointly by the Department of Health & Human Services, the Department of Labor, and the Department of the Treasury. If finalized, it would give consumers “real-time, personalized access to cost-sharing information, including an estimate of their cost-sharing liability for all covered health care items and services through an online tool that most group health plans and health insurance issuers would be required to make available to all of their members, and in paper form, at the consumer’s request,” a fact sheet outlining the features of the proposed rule states.

Health plans would also “be required to disclose on a public website their negotiated rates for in-network providers and allowed amounts paid for out-of-network providers,” the fact sheet continues.

The proposal comes as the CMS finalized transparency-related rules in the 2020 update to the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS). The price transparency portion of the OPPS is scheduled to go into effect on Jan. 1, 2021.

A fact sheet on the OPPS states that each hospital in the United States will be required to “establish (and update) and make public a yearly list of the hospital’s standard charges for items and services provided by the hospital.”

That list must include all standard charges, including gross charges, discounted cash prices, payer-specific negotiated charges, and deidentified minimum and maximum negotiated charges for all hospital items and services, as well as cash prices, payer-specific negotiated charges, and deidentified minimum and maximum negotiated charges for 300 shoppable services (70 identified by CMS and 230 selected by the hospital). A shoppable service is a service that can be scheduled in advance.

“This final rule and the proposed rule will bring forward the transparency we need to finally begin reducing the overall health care costs,” Ms. Verma said. “Today’s rules usher in a new era that upends the status quo to empower patients and put them first.”

America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a statement that it is evaluating the proposal and the final OPPS rule through a lens of three core principles: that consumers deserve transparency about out-of-pocket costs to help them make informed decisions; that transparency should be achieved in a way that encourages, not undermines, competitive negotiations to lower costs; and that public programs and the free market work together to deliver on our commitments to affordable, quality, and value.

“Neither of these rules, together or separately, satisfies these principles,” AHIP stated.

The Federation of American Hospitals is already anticipating a legal challenge to the rules.

“Patients should have readily available and easy-to-understand cost-sharing information when they need to make health care decisions,” FAH President and CEO Chip Kahn said in a statement. “Health care pricing transparency ought to be defined by the right information at the right time. This final regulation on hospital transparency fails to meet the definition of price transparency useful for patients. Instead, it will only result in patient overload of useless information while distorting the competitive market for purchasing hospital care.”

Mr. Kahn said FAH plans “on joining with hospitals to file a legal challenge,” asserting that CMS has exceeded it’s authority with these rules.

Three federal agencies have jointly issued a price transparency proposal that would require most employer-based health plans and health insurance issuers to disclose price and cost-sharing information up front.

The goal behind the proposal is to give consumers accurate estimates about the out-of-pocket costs they may incur for medical services, giving them the opportunity to shop around for medical treatment.

“Under the status quo, health care prices are about as clear as mud to patients,” Seema Verma, administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a statement, adding that “we are throwing open the shutters and bringing to light the price of care for American consumers. Kept secret, these prices are simply dollar amounts on a ledger; disclosed, they deliver fuel to the engines of competition among hospitals and insurers.”

The “Transparency in Coverage” proposed rule, was released online on Nov. 15 jointly by the Department of Health & Human Services, the Department of Labor, and the Department of the Treasury. If finalized, it would give consumers “real-time, personalized access to cost-sharing information, including an estimate of their cost-sharing liability for all covered health care items and services through an online tool that most group health plans and health insurance issuers would be required to make available to all of their members, and in paper form, at the consumer’s request,” a fact sheet outlining the features of the proposed rule states.

Health plans would also “be required to disclose on a public website their negotiated rates for in-network providers and allowed amounts paid for out-of-network providers,” the fact sheet continues.

The proposal comes as the CMS finalized transparency-related rules in the 2020 update to the hospital outpatient prospective payment system (OPPS). The price transparency portion of the OPPS is scheduled to go into effect on Jan. 1, 2021.

A fact sheet on the OPPS states that each hospital in the United States will be required to “establish (and update) and make public a yearly list of the hospital’s standard charges for items and services provided by the hospital.”

That list must include all standard charges, including gross charges, discounted cash prices, payer-specific negotiated charges, and deidentified minimum and maximum negotiated charges for all hospital items and services, as well as cash prices, payer-specific negotiated charges, and deidentified minimum and maximum negotiated charges for 300 shoppable services (70 identified by CMS and 230 selected by the hospital). A shoppable service is a service that can be scheduled in advance.

“This final rule and the proposed rule will bring forward the transparency we need to finally begin reducing the overall health care costs,” Ms. Verma said. “Today’s rules usher in a new era that upends the status quo to empower patients and put them first.”

America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a statement that it is evaluating the proposal and the final OPPS rule through a lens of three core principles: that consumers deserve transparency about out-of-pocket costs to help them make informed decisions; that transparency should be achieved in a way that encourages, not undermines, competitive negotiations to lower costs; and that public programs and the free market work together to deliver on our commitments to affordable, quality, and value.

“Neither of these rules, together or separately, satisfies these principles,” AHIP stated.

The Federation of American Hospitals is already anticipating a legal challenge to the rules.

“Patients should have readily available and easy-to-understand cost-sharing information when they need to make health care decisions,” FAH President and CEO Chip Kahn said in a statement. “Health care pricing transparency ought to be defined by the right information at the right time. This final regulation on hospital transparency fails to meet the definition of price transparency useful for patients. Instead, it will only result in patient overload of useless information while distorting the competitive market for purchasing hospital care.”

Mr. Kahn said FAH plans “on joining with hospitals to file a legal challenge,” asserting that CMS has exceeded it’s authority with these rules.

Lay press stories about research: Putting them into perspective for patients

I recently had an unusual patient call. A woman I’ve seen for many years for migraines called to tell me her son was being hospitalized for appendicitis. He was scheduled for surgery in the morning.

She called because she’d recently seen a news report about how people without an appendix may have a higher rate of Parkinson’s disease as they age. She was, understandably, concerned about the long-term risks the procedure could pose.

On the surface, as a medical professional, the call sounds frivolous and silly. The risks of untreated acute appendicitis, such as peritonitis and death, are pretty well documented. Surgery offers the best possibility for a cure without recurrence. Compared with the long-term, uncertain, risk of Parkinson’s disease, the benefit-to-risk ratio and options are pretty obvious.

The question of the GI tract’s involvement in neurologic diseases is a legitimate one that needs to be answered. It may provide new insight into their causes and potential treatments. The research she brought up raises some interesting points.

But that doesn’t mean there should be any delay in treating something as easily cured – and potentially serious – as acute appendicitis.

My patient called to ask questions, and I have no issue with that. To someone with no medical training, it’s a legitimate concern. But not everyone will call to ask.

This is a hazard of early stages of medical research making it into the lay press. It may be right, it may be wrong, but it’s too early to tell either way. We have years of training to help us recognize the uncertainties of preliminary data, but the general public doesn’t. Stories like this create interest and raise questions in the medical literature and fear and anxiety in the lay press.

I’m a strong supporter of freedom of the press, and certainly they have every right to air or publish such stories. But they should also be put in perspective at the beginning, not the bottom, and make it clear the findings are far from proven.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I recently had an unusual patient call. A woman I’ve seen for many years for migraines called to tell me her son was being hospitalized for appendicitis. He was scheduled for surgery in the morning.

She called because she’d recently seen a news report about how people without an appendix may have a higher rate of Parkinson’s disease as they age. She was, understandably, concerned about the long-term risks the procedure could pose.

On the surface, as a medical professional, the call sounds frivolous and silly. The risks of untreated acute appendicitis, such as peritonitis and death, are pretty well documented. Surgery offers the best possibility for a cure without recurrence. Compared with the long-term, uncertain, risk of Parkinson’s disease, the benefit-to-risk ratio and options are pretty obvious.

The question of the GI tract’s involvement in neurologic diseases is a legitimate one that needs to be answered. It may provide new insight into their causes and potential treatments. The research she brought up raises some interesting points.

But that doesn’t mean there should be any delay in treating something as easily cured – and potentially serious – as acute appendicitis.

My patient called to ask questions, and I have no issue with that. To someone with no medical training, it’s a legitimate concern. But not everyone will call to ask.

This is a hazard of early stages of medical research making it into the lay press. It may be right, it may be wrong, but it’s too early to tell either way. We have years of training to help us recognize the uncertainties of preliminary data, but the general public doesn’t. Stories like this create interest and raise questions in the medical literature and fear and anxiety in the lay press.

I’m a strong supporter of freedom of the press, and certainly they have every right to air or publish such stories. But they should also be put in perspective at the beginning, not the bottom, and make it clear the findings are far from proven.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I recently had an unusual patient call. A woman I’ve seen for many years for migraines called to tell me her son was being hospitalized for appendicitis. He was scheduled for surgery in the morning.

She called because she’d recently seen a news report about how people without an appendix may have a higher rate of Parkinson’s disease as they age. She was, understandably, concerned about the long-term risks the procedure could pose.

On the surface, as a medical professional, the call sounds frivolous and silly. The risks of untreated acute appendicitis, such as peritonitis and death, are pretty well documented. Surgery offers the best possibility for a cure without recurrence. Compared with the long-term, uncertain, risk of Parkinson’s disease, the benefit-to-risk ratio and options are pretty obvious.

The question of the GI tract’s involvement in neurologic diseases is a legitimate one that needs to be answered. It may provide new insight into their causes and potential treatments. The research she brought up raises some interesting points.

But that doesn’t mean there should be any delay in treating something as easily cured – and potentially serious – as acute appendicitis.

My patient called to ask questions, and I have no issue with that. To someone with no medical training, it’s a legitimate concern. But not everyone will call to ask.

This is a hazard of early stages of medical research making it into the lay press. It may be right, it may be wrong, but it’s too early to tell either way. We have years of training to help us recognize the uncertainties of preliminary data, but the general public doesn’t. Stories like this create interest and raise questions in the medical literature and fear and anxiety in the lay press.

I’m a strong supporter of freedom of the press, and certainly they have every right to air or publish such stories. But they should also be put in perspective at the beginning, not the bottom, and make it clear the findings are far from proven.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

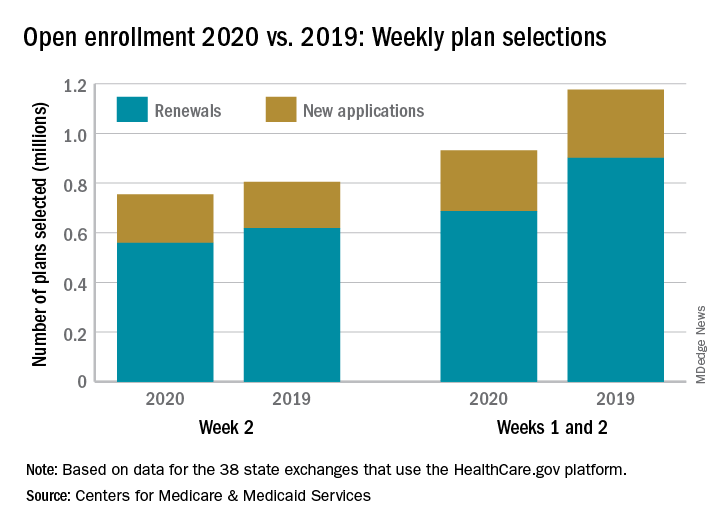

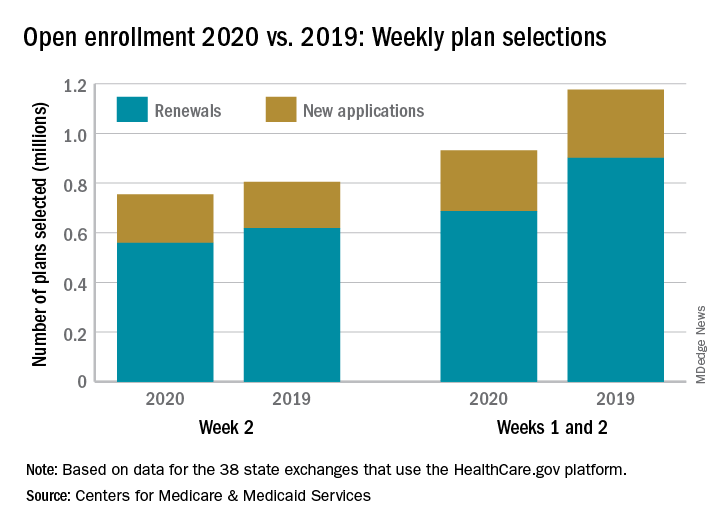

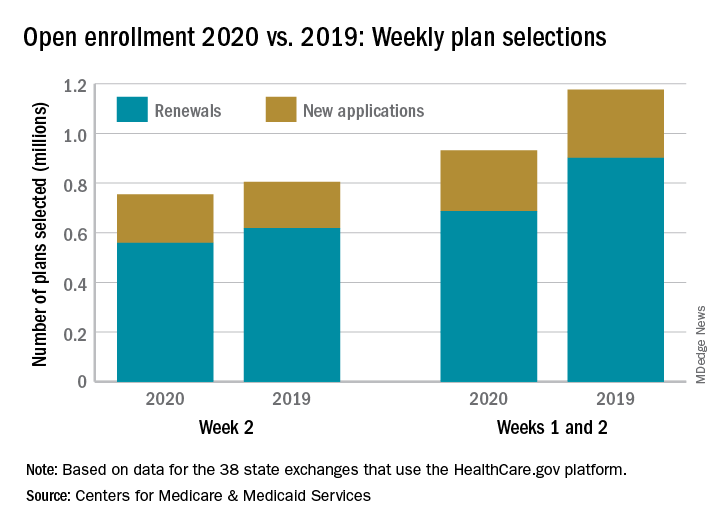

Open enrollment 2020: HealthCare.gov activity down from last year

The federal health insurance exchange is now through the first 2 weeks of its 2020 open enrollment on the HealthCare.gov platform, and just over 930,000 plans have been selected, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported.

The majority of those selections – almost 690,000 – were made by consumers renewing their existing coverage, with the rest coming from new consumers who did not have exchange coverage for 2019, the CMS said in its weekly enrollment snapshot on Nov. 13.

The total number of plans selected through week 2 is down almost 21% from last year, when selections totaled almost 1.18 million. This year, however, week 1 of open enrollment was only 2 days long (Nov. 1-2), versus 3 days (Nov. 1-3) last year, and last year there were 39 states using HealthCare.gov, compared with 38 this year since Nevada now has its own state-based exchange.

The total number of plans selected during a particular reporting period can change later if plans are modified or canceled, CMS noted, and “the weekly snapshot only reports new plan selections and active plan renewals and does not report the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.”

The federal health insurance exchange is now through the first 2 weeks of its 2020 open enrollment on the HealthCare.gov platform, and just over 930,000 plans have been selected, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported.

The majority of those selections – almost 690,000 – were made by consumers renewing their existing coverage, with the rest coming from new consumers who did not have exchange coverage for 2019, the CMS said in its weekly enrollment snapshot on Nov. 13.

The total number of plans selected through week 2 is down almost 21% from last year, when selections totaled almost 1.18 million. This year, however, week 1 of open enrollment was only 2 days long (Nov. 1-2), versus 3 days (Nov. 1-3) last year, and last year there were 39 states using HealthCare.gov, compared with 38 this year since Nevada now has its own state-based exchange.

The total number of plans selected during a particular reporting period can change later if plans are modified or canceled, CMS noted, and “the weekly snapshot only reports new plan selections and active plan renewals and does not report the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.”

The federal health insurance exchange is now through the first 2 weeks of its 2020 open enrollment on the HealthCare.gov platform, and just over 930,000 plans have been selected, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reported.

The majority of those selections – almost 690,000 – were made by consumers renewing their existing coverage, with the rest coming from new consumers who did not have exchange coverage for 2019, the CMS said in its weekly enrollment snapshot on Nov. 13.

The total number of plans selected through week 2 is down almost 21% from last year, when selections totaled almost 1.18 million. This year, however, week 1 of open enrollment was only 2 days long (Nov. 1-2), versus 3 days (Nov. 1-3) last year, and last year there were 39 states using HealthCare.gov, compared with 38 this year since Nevada now has its own state-based exchange.

The total number of plans selected during a particular reporting period can change later if plans are modified or canceled, CMS noted, and “the weekly snapshot only reports new plan selections and active plan renewals and does not report the number of consumers who have paid premiums to effectuate their enrollment.”

ACP recommends ways to address rising drug prices

such as promoting the use of lower-cost generics and introducing annual out-of-pocket spending caps.

Two position papers, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, outlined the College’s concerns about the increasing price of prescription drugs for Medicare and Medicaid, pointing out that the United States has an average annual per capita spend of $1,443 on pharmaceutical drugs and $1,026 on retail prescription drugs.

“The primary differences between health care expenditures in the United States versus other high-income nations are pricing of medical goods and services and the lack of direct price controls or negotiating power by centralized government health care systems,” wrote Hilary Daniel and Sue S. Bornstein, MD, of the Health Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians, in one of the papers.

They cited the example of new drugs for hepatitis C which, at more than $80,000 for a treatment course, accounted for 40% of the net growth in prescription drug spending in 2014.

Their first recommendation was to modify the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) program, which currently supports approximately 12 million beneficiaries, to encourage the use of lower-cost generic or biosimilar drugs.

The rate of generic drug dispensing among LIS enrollees has been consistently 4%-5% lower than among non-LIS enrollees, they wrote. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimated that Medicare could have saved nearly $9 billion, and passed on $3 billion in savings to the Part D program and its beneficiaries, if available equivalent generics were prescribed instead of brand-name drugs.

The authors wrote that zero-copay generics have had the strongest effect on generic drug use, both for LIS and non-LIS enrollees.

“Reducing or eliminating cost sharing for LIS enrollees would not require legislative action, because it would not increase cost sharing, would reduce overall out-of pocket costs for LIS enrollees, and would encourage use of generics among them,” they wrote. They authors of the paper also argued that this move could reduce Medicare spending on reinsurance payments, because most enrollees who reach the ‘catastrophic’ phase of coverage were in the LIS program.

The second recommendation was for annual out-of-pocket spending caps for Medicare Part D beneficiaries who reach the catastrophic phase of coverage. During 2007-2015, the number of seniors in Medicare Part D who reached this catastrophic limit of coverage doubled to more than 1 million, with those enrollees paying an average of more than $3,000 out of pocket in 2015 alone, the authors noted.

“Caps have been proposed in other areas of Medicare; a 2016 resolution from the House Committee on the Budget included a Medicare proposal with a catastrophic coverage cap on annual out-of-pocket expenses, which it called, ‘an important aspect of the private insurance market currently absent from Medicare that would safeguard the sickest and poorest beneficiaries,’ ” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Shelley A. Jazowski of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and coauthor Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., said that, while a cap would improve financial protection for beneficiaries, it could result in trade-offs such as increased premiums to accommodate lower spending by some beneficiaries.

The American College of Physicians (ACP) supports a full repeal of the noninterference clause in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, wrote the position paper’s authors. This Act prohibits Medicare from negotiating directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers over the price of drugs.

The position paper also advocated for interim approaches, such as allowing the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate on the price of a limited set of high-cost or sole-source drugs.

“Although negotiation alone may not be enough to rein in drug prices, this approach would allow the government to leverage its purchasing power to reduce Medicare program costs while also allowing plan sponsors to maintain the power to negotiate for the vast majority of drugs covered in the program,” they wrote.

The editorial’s authors pointed out that the success of these negotiations would rely on the ability of Medicare to walk away from a bad deal, which could delay or limit the availability of some drugs with limited competitors.

The ACP also called for efforts to minimize the financial impact of misclassifications of prescription drugs in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program on the federal government. One study found that these misclassifications occurred in 885 of the 30,000 drugs in the program. The EpiPen and EpiPen Jr autoinjectors, for example, were improperly classified as generic drugs, the paper states.

The authors’ final recommendation in the position paper was for further study of payment models that could reduce incentives to prescribe higher-priced drugs instead of lower-cost and similarly effective options.

In the second position paper, Ms. Daniel and Dr. Bornstein made policy recommendations targeted at pharmacy benefit managers. The first was to improve transparency for pharmacy benefit managers, such as by banning gag clauses that might prevent pharmacies from sharing pricing information with consumers.

“The continued lack of transparency from [pharmacy benefit managers] and insurers can hinder how patients, physicians, and others view the drug supply chain and can make it difficult to identify whether a particular entity is inappropriately driving up drug prices,” the authors wrote in the second position paper.

This was accompanied by a recommendation that accurate, understandable and actionable information on the price of prescription medication should be made available to physicians and patients at the point of prescription. They also called for health plans, pharmacy benefit managers and pharmaceutical manufacturers to share information on the amount paid for prescription drugs, aggregate amount of rebates, and pricing decisions to the Department of Health & Human Services and make that information publicly available, with exceptions for confidential data.

The editorial’s authors commented that many of the policy recommendations raised in the position paper were currently being debated in Congress, and there was clear support from physician groups to address drug pricing, out-of-pocket spending, and access.

“Although trade-offs will need to be considered before selection or implementation of policy solutions, policymakers must act to ensure that patients have access to the prescription drugs they need at a price that reflects the benefits to patients and society,” they wrote.

One author declared book royalties but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCES: Daniel H et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Nov 12. doi. 10.7326/M19-0013; doi. 10.7326/M19-0035.

such as promoting the use of lower-cost generics and introducing annual out-of-pocket spending caps.

Two position papers, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, outlined the College’s concerns about the increasing price of prescription drugs for Medicare and Medicaid, pointing out that the United States has an average annual per capita spend of $1,443 on pharmaceutical drugs and $1,026 on retail prescription drugs.

“The primary differences between health care expenditures in the United States versus other high-income nations are pricing of medical goods and services and the lack of direct price controls or negotiating power by centralized government health care systems,” wrote Hilary Daniel and Sue S. Bornstein, MD, of the Health Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians, in one of the papers.

They cited the example of new drugs for hepatitis C which, at more than $80,000 for a treatment course, accounted for 40% of the net growth in prescription drug spending in 2014.

Their first recommendation was to modify the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) program, which currently supports approximately 12 million beneficiaries, to encourage the use of lower-cost generic or biosimilar drugs.

The rate of generic drug dispensing among LIS enrollees has been consistently 4%-5% lower than among non-LIS enrollees, they wrote. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimated that Medicare could have saved nearly $9 billion, and passed on $3 billion in savings to the Part D program and its beneficiaries, if available equivalent generics were prescribed instead of brand-name drugs.

The authors wrote that zero-copay generics have had the strongest effect on generic drug use, both for LIS and non-LIS enrollees.

“Reducing or eliminating cost sharing for LIS enrollees would not require legislative action, because it would not increase cost sharing, would reduce overall out-of pocket costs for LIS enrollees, and would encourage use of generics among them,” they wrote. They authors of the paper also argued that this move could reduce Medicare spending on reinsurance payments, because most enrollees who reach the ‘catastrophic’ phase of coverage were in the LIS program.

The second recommendation was for annual out-of-pocket spending caps for Medicare Part D beneficiaries who reach the catastrophic phase of coverage. During 2007-2015, the number of seniors in Medicare Part D who reached this catastrophic limit of coverage doubled to more than 1 million, with those enrollees paying an average of more than $3,000 out of pocket in 2015 alone, the authors noted.

“Caps have been proposed in other areas of Medicare; a 2016 resolution from the House Committee on the Budget included a Medicare proposal with a catastrophic coverage cap on annual out-of-pocket expenses, which it called, ‘an important aspect of the private insurance market currently absent from Medicare that would safeguard the sickest and poorest beneficiaries,’ ” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Shelley A. Jazowski of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and coauthor Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., said that, while a cap would improve financial protection for beneficiaries, it could result in trade-offs such as increased premiums to accommodate lower spending by some beneficiaries.

The American College of Physicians (ACP) supports a full repeal of the noninterference clause in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, wrote the position paper’s authors. This Act prohibits Medicare from negotiating directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers over the price of drugs.

The position paper also advocated for interim approaches, such as allowing the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate on the price of a limited set of high-cost or sole-source drugs.

“Although negotiation alone may not be enough to rein in drug prices, this approach would allow the government to leverage its purchasing power to reduce Medicare program costs while also allowing plan sponsors to maintain the power to negotiate for the vast majority of drugs covered in the program,” they wrote.

The editorial’s authors pointed out that the success of these negotiations would rely on the ability of Medicare to walk away from a bad deal, which could delay or limit the availability of some drugs with limited competitors.

The ACP also called for efforts to minimize the financial impact of misclassifications of prescription drugs in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program on the federal government. One study found that these misclassifications occurred in 885 of the 30,000 drugs in the program. The EpiPen and EpiPen Jr autoinjectors, for example, were improperly classified as generic drugs, the paper states.

The authors’ final recommendation in the position paper was for further study of payment models that could reduce incentives to prescribe higher-priced drugs instead of lower-cost and similarly effective options.

In the second position paper, Ms. Daniel and Dr. Bornstein made policy recommendations targeted at pharmacy benefit managers. The first was to improve transparency for pharmacy benefit managers, such as by banning gag clauses that might prevent pharmacies from sharing pricing information with consumers.

“The continued lack of transparency from [pharmacy benefit managers] and insurers can hinder how patients, physicians, and others view the drug supply chain and can make it difficult to identify whether a particular entity is inappropriately driving up drug prices,” the authors wrote in the second position paper.

This was accompanied by a recommendation that accurate, understandable and actionable information on the price of prescription medication should be made available to physicians and patients at the point of prescription. They also called for health plans, pharmacy benefit managers and pharmaceutical manufacturers to share information on the amount paid for prescription drugs, aggregate amount of rebates, and pricing decisions to the Department of Health & Human Services and make that information publicly available, with exceptions for confidential data.

The editorial’s authors commented that many of the policy recommendations raised in the position paper were currently being debated in Congress, and there was clear support from physician groups to address drug pricing, out-of-pocket spending, and access.

“Although trade-offs will need to be considered before selection or implementation of policy solutions, policymakers must act to ensure that patients have access to the prescription drugs they need at a price that reflects the benefits to patients and society,” they wrote.

One author declared book royalties but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCES: Daniel H et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Nov 12. doi. 10.7326/M19-0013; doi. 10.7326/M19-0035.

such as promoting the use of lower-cost generics and introducing annual out-of-pocket spending caps.

Two position papers, published in Annals of Internal Medicine, outlined the College’s concerns about the increasing price of prescription drugs for Medicare and Medicaid, pointing out that the United States has an average annual per capita spend of $1,443 on pharmaceutical drugs and $1,026 on retail prescription drugs.

“The primary differences between health care expenditures in the United States versus other high-income nations are pricing of medical goods and services and the lack of direct price controls or negotiating power by centralized government health care systems,” wrote Hilary Daniel and Sue S. Bornstein, MD, of the Health Public Policy Committee of the American College of Physicians, in one of the papers.

They cited the example of new drugs for hepatitis C which, at more than $80,000 for a treatment course, accounted for 40% of the net growth in prescription drug spending in 2014.

Their first recommendation was to modify the Medicare Part D low-income subsidy (LIS) program, which currently supports approximately 12 million beneficiaries, to encourage the use of lower-cost generic or biosimilar drugs.

The rate of generic drug dispensing among LIS enrollees has been consistently 4%-5% lower than among non-LIS enrollees, they wrote. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services estimated that Medicare could have saved nearly $9 billion, and passed on $3 billion in savings to the Part D program and its beneficiaries, if available equivalent generics were prescribed instead of brand-name drugs.

The authors wrote that zero-copay generics have had the strongest effect on generic drug use, both for LIS and non-LIS enrollees.

“Reducing or eliminating cost sharing for LIS enrollees would not require legislative action, because it would not increase cost sharing, would reduce overall out-of pocket costs for LIS enrollees, and would encourage use of generics among them,” they wrote. They authors of the paper also argued that this move could reduce Medicare spending on reinsurance payments, because most enrollees who reach the ‘catastrophic’ phase of coverage were in the LIS program.

The second recommendation was for annual out-of-pocket spending caps for Medicare Part D beneficiaries who reach the catastrophic phase of coverage. During 2007-2015, the number of seniors in Medicare Part D who reached this catastrophic limit of coverage doubled to more than 1 million, with those enrollees paying an average of more than $3,000 out of pocket in 2015 alone, the authors noted.

“Caps have been proposed in other areas of Medicare; a 2016 resolution from the House Committee on the Budget included a Medicare proposal with a catastrophic coverage cap on annual out-of-pocket expenses, which it called, ‘an important aspect of the private insurance market currently absent from Medicare that would safeguard the sickest and poorest beneficiaries,’ ” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial, Shelley A. Jazowski of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and coauthor Stacie B. Dusetzina, PhD, of Vanderbilt University, in Nashville, Tenn., said that, while a cap would improve financial protection for beneficiaries, it could result in trade-offs such as increased premiums to accommodate lower spending by some beneficiaries.

The American College of Physicians (ACP) supports a full repeal of the noninterference clause in the Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act of 2003, wrote the position paper’s authors. This Act prohibits Medicare from negotiating directly with pharmaceutical manufacturers over the price of drugs.

The position paper also advocated for interim approaches, such as allowing the Secretary of Health and Human Services to negotiate on the price of a limited set of high-cost or sole-source drugs.

“Although negotiation alone may not be enough to rein in drug prices, this approach would allow the government to leverage its purchasing power to reduce Medicare program costs while also allowing plan sponsors to maintain the power to negotiate for the vast majority of drugs covered in the program,” they wrote.

The editorial’s authors pointed out that the success of these negotiations would rely on the ability of Medicare to walk away from a bad deal, which could delay or limit the availability of some drugs with limited competitors.

The ACP also called for efforts to minimize the financial impact of misclassifications of prescription drugs in the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program on the federal government. One study found that these misclassifications occurred in 885 of the 30,000 drugs in the program. The EpiPen and EpiPen Jr autoinjectors, for example, were improperly classified as generic drugs, the paper states.

The authors’ final recommendation in the position paper was for further study of payment models that could reduce incentives to prescribe higher-priced drugs instead of lower-cost and similarly effective options.

In the second position paper, Ms. Daniel and Dr. Bornstein made policy recommendations targeted at pharmacy benefit managers. The first was to improve transparency for pharmacy benefit managers, such as by banning gag clauses that might prevent pharmacies from sharing pricing information with consumers.

“The continued lack of transparency from [pharmacy benefit managers] and insurers can hinder how patients, physicians, and others view the drug supply chain and can make it difficult to identify whether a particular entity is inappropriately driving up drug prices,” the authors wrote in the second position paper.

This was accompanied by a recommendation that accurate, understandable and actionable information on the price of prescription medication should be made available to physicians and patients at the point of prescription. They also called for health plans, pharmacy benefit managers and pharmaceutical manufacturers to share information on the amount paid for prescription drugs, aggregate amount of rebates, and pricing decisions to the Department of Health & Human Services and make that information publicly available, with exceptions for confidential data.

The editorial’s authors commented that many of the policy recommendations raised in the position paper were currently being debated in Congress, and there was clear support from physician groups to address drug pricing, out-of-pocket spending, and access.

“Although trade-offs will need to be considered before selection or implementation of policy solutions, policymakers must act to ensure that patients have access to the prescription drugs they need at a price that reflects the benefits to patients and society,” they wrote.

One author declared book royalties but no other conflicts of interest were declared.

SOURCES: Daniel H et al. Ann Intern Med. 2019 Nov 12. doi. 10.7326/M19-0013; doi. 10.7326/M19-0035.

FROM ANNALS OF INTERNAL MEDICINE

‘Tis the season to reflect and take stock

‘Tis the season to reflect and take stock: Maybe you had a baby, or learned a new procedure, or bought a Tesla? Of course, you made (loads of?) money and treated many patients. Imagine if I asked you this in person, what would you reply? And what made you most proud? I’d tell you this story.

Last week I saw a 50-something-year-old woman for her annual skin screening. She asked if I remembered her mother, who was also my patient. Squinting through my dermatoscope at the nevi on her back, I tried to recall. “Yes, I think so.” (Actually, I was unsure.)

“Well she passed away last week from breast cancer,” she said.

“Oh, I’m sorry to hear that,” I replied.

She added: “Yes, yet she lived much longer than we thought. I want you to know we believe it was in large part because of you.”

I stopped and wheeled around to face her. How could that possibly be true? I had only treated her for a simple skin cancer. She explained that I had seen her mom about a year ago and cut out a skin cancer on her face. Her mom was afraid of needles and of surgery. Apparently when she asked me if it would hurt, I replied: “Well, most patients, yes, but not you.” Pausing, I added: “Because you’re a tough old bird.” She laughed. Apparently that warmth I conveyed and display of confidence in her was just what she needed at that moment. She didn’t flinch.

Not long after, she was diagnosed with breast cancer. When given the news with her children present, she replied, “well, I’ll just fight it. I’m a tough old bird.” It was just what they needed in that moment. “I’m a tough old bird” became their rally cry. Apparently with each stage, surgery, radiation, chemo, they fell back on it. Her son had “Tough Old Bird” made into a magnet and prominently posted on the refrigerator door where she would see it every day.