User login

Strategy critical to surviving drug shortages

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. –

“Statistically speaking, there is no proof that patients are worse off from drug shortages,” Matt Grissinger, RPh, director of error-reporting programs at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, told the audience at the annual conference of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. The data and anecdotes he presented suggest the contrary.

As Mr. Grissinger pointed out, drug shortages can create a sequela of events that stress health care workers seeking to find the next-best available and most appropriate therapy for their patients. In the process, numerous medication-related errors can occur, resulting in patient harm, including adverse drug events and even death.

One potential problems is erroneous or inappropriate drug substitution stemming from mis- or uncalculated doses because of factors such as incorrect labeling and lack of knowledge regarding acceptable therapeutic interchanges. Other potential errors include non–therapeutically equivalent drug substitutions, resulting in supraoptimal therapy or overdoses, and unfamiliarity with drug labeling from outsourced facilities.

As a result, patients may experience worse outcomes as a consequence of the drug shortage: Worsening of the disease, disease prolongation, side effects stemming from alternative drug selections, untreated pain, psychological effects, severe electrolyte imbalances, severe acid/base imbalances, and death.

While a paper trail can help piece together clues regarding how a medication error occurred, documentation or lack thereof can also introduce errors when drug shortages occur.

Any changes to a drug order or prescription that deviate from the prescriber’s original request require prescriber approval but can still create opportunities for error. While documenting these changes and updating labeling is essential, appropriate documentation does not always occur and raises the question of who is responsible for making such changes.

Drug shortages also challenge a clinician’s professional judgment. Mr. Grissinger cited an example in which a nurse used half of a 0.5-mg single-use vial of promethazine for a patient requiring a 0.25 mg dose. The nurse wrote on the label that the remainder should be saved. While the vial was manufactured for one-time use, whether to discard the unused contents in a situation of drug shortages required the nurse to make a judgment call. In this case, the nurse chose to save the balance of the drug – a choice Mr. Grissinger stated he might have made had he been in a similar situation.

Additionally, drug shortages can create a climate in which more ethical questions arise – especially with regard to disease states such as cancer.

“If you only have 10 vials of vincristine, who gets it?” Mr. Grissinger asked the audience.

To help answer these difficult life-or-death questions, hospital settings need to engage the ethics committees and social workers.

While education plays a vital role in bringing attention to and addressing errors stemming from drug shortages, Mr. Grissinger cautioned the audience not to rely on education as the solution.

“Education is a poor strategy for addressing drug shortages,” he said. While education can draw awareness to drug shortages and subsequent medication-related errors, Mr. Grissinger recommends that organizations implement strategies to help ameliorate the havoc created by drug shortages.

Drug shortage assessment checklists can help organizations evaluate the impact of shortages by verifying inventory, and proactively searching for alternatives. From there, they can enact strategies such as assigning priority to patients who have the greatest need, altering packaging and concentrations, and finding suitable therapeutic substitutions.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. –

“Statistically speaking, there is no proof that patients are worse off from drug shortages,” Matt Grissinger, RPh, director of error-reporting programs at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, told the audience at the annual conference of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. The data and anecdotes he presented suggest the contrary.

As Mr. Grissinger pointed out, drug shortages can create a sequela of events that stress health care workers seeking to find the next-best available and most appropriate therapy for their patients. In the process, numerous medication-related errors can occur, resulting in patient harm, including adverse drug events and even death.

One potential problems is erroneous or inappropriate drug substitution stemming from mis- or uncalculated doses because of factors such as incorrect labeling and lack of knowledge regarding acceptable therapeutic interchanges. Other potential errors include non–therapeutically equivalent drug substitutions, resulting in supraoptimal therapy or overdoses, and unfamiliarity with drug labeling from outsourced facilities.

As a result, patients may experience worse outcomes as a consequence of the drug shortage: Worsening of the disease, disease prolongation, side effects stemming from alternative drug selections, untreated pain, psychological effects, severe electrolyte imbalances, severe acid/base imbalances, and death.

While a paper trail can help piece together clues regarding how a medication error occurred, documentation or lack thereof can also introduce errors when drug shortages occur.

Any changes to a drug order or prescription that deviate from the prescriber’s original request require prescriber approval but can still create opportunities for error. While documenting these changes and updating labeling is essential, appropriate documentation does not always occur and raises the question of who is responsible for making such changes.

Drug shortages also challenge a clinician’s professional judgment. Mr. Grissinger cited an example in which a nurse used half of a 0.5-mg single-use vial of promethazine for a patient requiring a 0.25 mg dose. The nurse wrote on the label that the remainder should be saved. While the vial was manufactured for one-time use, whether to discard the unused contents in a situation of drug shortages required the nurse to make a judgment call. In this case, the nurse chose to save the balance of the drug – a choice Mr. Grissinger stated he might have made had he been in a similar situation.

Additionally, drug shortages can create a climate in which more ethical questions arise – especially with regard to disease states such as cancer.

“If you only have 10 vials of vincristine, who gets it?” Mr. Grissinger asked the audience.

To help answer these difficult life-or-death questions, hospital settings need to engage the ethics committees and social workers.

While education plays a vital role in bringing attention to and addressing errors stemming from drug shortages, Mr. Grissinger cautioned the audience not to rely on education as the solution.

“Education is a poor strategy for addressing drug shortages,” he said. While education can draw awareness to drug shortages and subsequent medication-related errors, Mr. Grissinger recommends that organizations implement strategies to help ameliorate the havoc created by drug shortages.

Drug shortage assessment checklists can help organizations evaluate the impact of shortages by verifying inventory, and proactively searching for alternatives. From there, they can enact strategies such as assigning priority to patients who have the greatest need, altering packaging and concentrations, and finding suitable therapeutic substitutions.

NATIONAL HARBOR, MD. –

“Statistically speaking, there is no proof that patients are worse off from drug shortages,” Matt Grissinger, RPh, director of error-reporting programs at the Institute for Safe Medication Practices, told the audience at the annual conference of the Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy. The data and anecdotes he presented suggest the contrary.

As Mr. Grissinger pointed out, drug shortages can create a sequela of events that stress health care workers seeking to find the next-best available and most appropriate therapy for their patients. In the process, numerous medication-related errors can occur, resulting in patient harm, including adverse drug events and even death.

One potential problems is erroneous or inappropriate drug substitution stemming from mis- or uncalculated doses because of factors such as incorrect labeling and lack of knowledge regarding acceptable therapeutic interchanges. Other potential errors include non–therapeutically equivalent drug substitutions, resulting in supraoptimal therapy or overdoses, and unfamiliarity with drug labeling from outsourced facilities.

As a result, patients may experience worse outcomes as a consequence of the drug shortage: Worsening of the disease, disease prolongation, side effects stemming from alternative drug selections, untreated pain, psychological effects, severe electrolyte imbalances, severe acid/base imbalances, and death.

While a paper trail can help piece together clues regarding how a medication error occurred, documentation or lack thereof can also introduce errors when drug shortages occur.

Any changes to a drug order or prescription that deviate from the prescriber’s original request require prescriber approval but can still create opportunities for error. While documenting these changes and updating labeling is essential, appropriate documentation does not always occur and raises the question of who is responsible for making such changes.

Drug shortages also challenge a clinician’s professional judgment. Mr. Grissinger cited an example in which a nurse used half of a 0.5-mg single-use vial of promethazine for a patient requiring a 0.25 mg dose. The nurse wrote on the label that the remainder should be saved. While the vial was manufactured for one-time use, whether to discard the unused contents in a situation of drug shortages required the nurse to make a judgment call. In this case, the nurse chose to save the balance of the drug – a choice Mr. Grissinger stated he might have made had he been in a similar situation.

Additionally, drug shortages can create a climate in which more ethical questions arise – especially with regard to disease states such as cancer.

“If you only have 10 vials of vincristine, who gets it?” Mr. Grissinger asked the audience.

To help answer these difficult life-or-death questions, hospital settings need to engage the ethics committees and social workers.

While education plays a vital role in bringing attention to and addressing errors stemming from drug shortages, Mr. Grissinger cautioned the audience not to rely on education as the solution.

“Education is a poor strategy for addressing drug shortages,” he said. While education can draw awareness to drug shortages and subsequent medication-related errors, Mr. Grissinger recommends that organizations implement strategies to help ameliorate the havoc created by drug shortages.

Drug shortage assessment checklists can help organizations evaluate the impact of shortages by verifying inventory, and proactively searching for alternatives. From there, they can enact strategies such as assigning priority to patients who have the greatest need, altering packaging and concentrations, and finding suitable therapeutic substitutions.

REPORTING FROM AMCP NEXUS 2019

Student vapers make mint the most popular Juul flavor

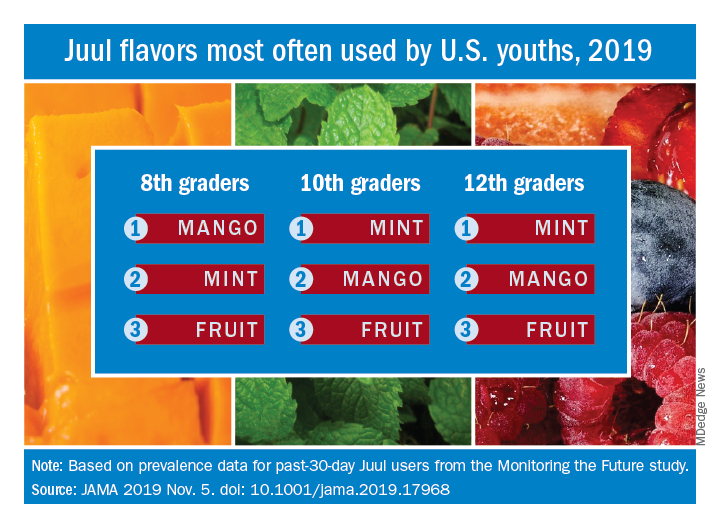

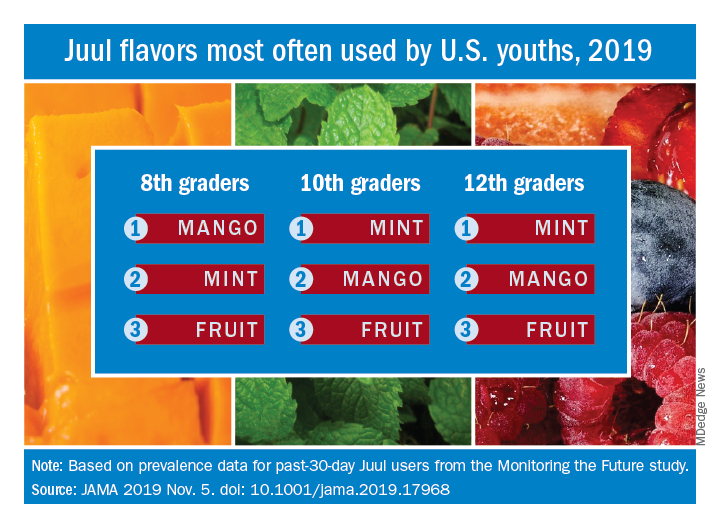

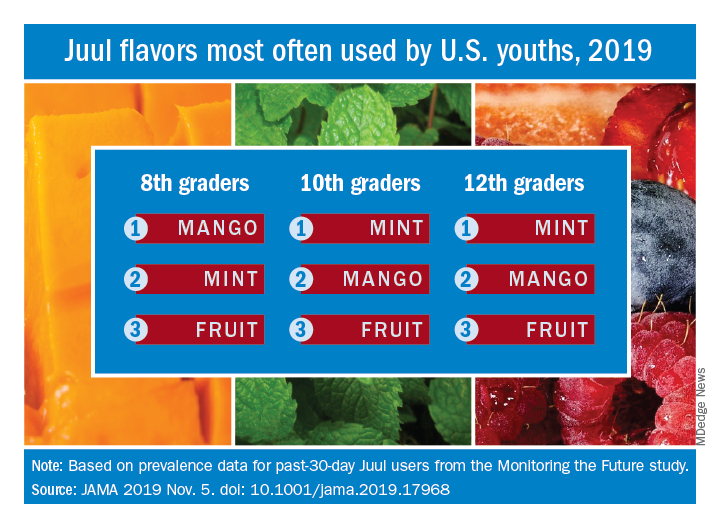

according to data from the 2019 Monitoring the Future study.

Almost half (47.1%) of the 12th graders who had used Juul e-cigarettes in the past 30 days reported that mint was the flavor they most often used, compared with 23.8% for mango and 8.6% for fruit, which is a combination of flavors, Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

Mint was also the flavor most often used by 10th graders (43.5%), with mango again second at 27.3%, and fruit third at 10.8%. Eighth-grade students switched mango (33.5%) and mint (29.2%) but had fruit third again at 16.0%, the investigators reported, based on data for 1,739 respondents to the Monitoring the Future survey who had used a vaping product within the past 30 days.

Juul has suspended sales of four – mango, fruit, creme, and cucumber – of its original eight flavors, Dr. Leventhal and associates noted, and e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco, menthol, and mint have been prohibited by some local municipalities.

“The current findings raise uncertainty whether regulations or sales suspensions that exempt mint flavors are optimal strategies for reducing youth e-cigarette use,” they wrote.

As this article was being written, the Wall Street Journal had just reported that the Food and Drug Administration will ban mint and all other e-cigarette flavors except tobacco and menthol.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968.

according to data from the 2019 Monitoring the Future study.

Almost half (47.1%) of the 12th graders who had used Juul e-cigarettes in the past 30 days reported that mint was the flavor they most often used, compared with 23.8% for mango and 8.6% for fruit, which is a combination of flavors, Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

Mint was also the flavor most often used by 10th graders (43.5%), with mango again second at 27.3%, and fruit third at 10.8%. Eighth-grade students switched mango (33.5%) and mint (29.2%) but had fruit third again at 16.0%, the investigators reported, based on data for 1,739 respondents to the Monitoring the Future survey who had used a vaping product within the past 30 days.

Juul has suspended sales of four – mango, fruit, creme, and cucumber – of its original eight flavors, Dr. Leventhal and associates noted, and e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco, menthol, and mint have been prohibited by some local municipalities.

“The current findings raise uncertainty whether regulations or sales suspensions that exempt mint flavors are optimal strategies for reducing youth e-cigarette use,” they wrote.

As this article was being written, the Wall Street Journal had just reported that the Food and Drug Administration will ban mint and all other e-cigarette flavors except tobacco and menthol.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968.

according to data from the 2019 Monitoring the Future study.

Almost half (47.1%) of the 12th graders who had used Juul e-cigarettes in the past 30 days reported that mint was the flavor they most often used, compared with 23.8% for mango and 8.6% for fruit, which is a combination of flavors, Adam M. Leventhal, PhD, of the University of Southern California, Los Angeles, and associates wrote in JAMA.

Mint was also the flavor most often used by 10th graders (43.5%), with mango again second at 27.3%, and fruit third at 10.8%. Eighth-grade students switched mango (33.5%) and mint (29.2%) but had fruit third again at 16.0%, the investigators reported, based on data for 1,739 respondents to the Monitoring the Future survey who had used a vaping product within the past 30 days.

Juul has suspended sales of four – mango, fruit, creme, and cucumber – of its original eight flavors, Dr. Leventhal and associates noted, and e-cigarette flavors other than tobacco, menthol, and mint have been prohibited by some local municipalities.

“The current findings raise uncertainty whether regulations or sales suspensions that exempt mint flavors are optimal strategies for reducing youth e-cigarette use,” they wrote.

As this article was being written, the Wall Street Journal had just reported that the Food and Drug Administration will ban mint and all other e-cigarette flavors except tobacco and menthol.

SOURCE: Leventhal AM et al. JAMA. 2019 Nov 5. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.17968.

FROM JAMA

MIPS, E/M changes highlight 2020 Medicare fee schedule

A Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) overhaul and evaluation and management changes to support the care of complex patients highlight the final Medicare physician fee schedule for 2020.

The new MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) framework “aims to align and connect measures and activities across the quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities performance categories of MIPS for different specialties or conditions,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a fact sheet outlining the updates to the Quality Payment Program.

CMS noted that the framework will have measures aimed at population health and public health priorities, as well as reducing the reporting burden of the MIPS program and providing enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.

“We also intend to analyze existing Medicare information so that we can provide clinicians and patients with more information to improve health outcomes,” the agency wrote. “We believe the MVPs framework will help simplify MIPS, create a more cohesive and meaningful participation experience, improve value, reduce clinician burden, and better align with APMs [advanced alternative payment models] to help ease transition between the two tracks.

While the specifics of how the pathways will work are yet to be determined, the goal is to reduce the reporting burden while increasing its clinical applicability

Under the current MIPS structure, clinicians report on a specific number of measures chosen from a menu that may or may not be relevant to the care of patients with a specific disease, such as diabetes.

The MVPs framework will have some “foundation” measures in the first 2 years linked to promoting interoperability and population health that all clinicians will use. These, however, will be coupled with additional measures across the other MIPS categories (quality, cost, and improvement) that are specifically related to diabetes treatment. The expectation is that disease-specific measures plus foundation measures will add up to fewer measures than clinicians currently report, according to CMS.

Over the next 3-5 years, disease-specific measures will be refined and foundation measures expanded to include enhanced performance feedback and patient-reported outcomes.

“We recognize that this will be a significant shift in the way clinicians may potentially participate in MIPS, therefore we want to work closely with clinicians, patients, specialty societies, third parties, and others to establish the MVPs,” CMS officials said.

In the meantime, there are changes to the current MIPS program. Category weighting remains unchanged for the 2020 performance year (payable in 2022), with the performance threshold being 45 points and the exceptional performance threshold being 85 points.

In the quality performance category, the data completeness threshold is increased to 70%, while the agency continues to remove low-bar, standard-of-care process measures and adding new specialty sets, such as audiology, chiropractic medicine, pulmonology, and endocrinology.

In the cost category, 10 new episode-based measures were added to help expand access to this category. In the improvement activities category, CMS reduced barriers to obtaining a patient-centered medical home designation and increased the participation threshold for a practice from a single clinician to 50% of the clinicians in the practice. In the promoting interoperability category, the agency included queries to a prescription drug–monitoring program as an option measure, removed the verify opioid treatment–agreement measure, and reduced the threshold for a group to be considered hospital based from 100% to 75% being hospital based in order for a group to be excluded from reporting measures in this category.

One change not made in the MIPS update is threshold for exclusion from participating in the MIPS program, which has generated continued criticism over the years from the American Medical Group Association, which represents multispecialty practices.

“Overall, CMS expects Part B payment adjustments of 1.4% for those providers who participate in the program,” AMGA officials said in a statement. “However, Congress authorized up to a 9% payment adjustment for the 2020 performance year. While not every provider will achieve the highest possible adjustment, CMS’ continued policy of excluding otherwise eligible providers from participating in MIPS makes it impossible to achieve sustainable payments to cover the cost of participation. Thus, AMGA members have expressed that the program is no longer a viable tool for transitioning to value-based care.”

The physician fee schedule also finalized a number of provisions aimed at reducing administrative burden and increasing the time physicians have with patients. The changes will save clinicians 2.3 million hours per year in burden reduction, according to CMS.

New evaluation and management services (E/M) codes will allow clinicians to choose the appropriate level of coding based on either the medical decision making or time spent with the patient. In 2021, an add-on code will be implemented for prolonged service times for when clinicians spend more time treating complex patients, according to a CMS fact sheet.

Beginning in 2020, clinicians will be paid for care management services for patients with one serious and high-risk condition. Previously, a patient would need at least two serious and high-risk conditions for clinicians to get paid for care management services. For those with multiple chronic conditions, a Medicare-specific code has been added that covers patient visits that last beyond 20 minutes allowed in the current coding for chronic care management services.

The E/M changes are “a significant step in reducing administrative burden that gets in the way of patient care. Now it’s time for vendors and payors to take the necessary steps to align their systems with the E/M office visit code changes by the time the revisions are deployed on Jan. 1, 2021,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement.

The American College of Physicians also applauded the change.

“Medicare has long undervalued E/M codes by internal medicine physicians, family physicians, and other cognitive and primary care physicians,” ACP said in a statement, adding that it is “extremely pleased that CMS’s final payment rules will strengthen primary and cognitive care by improving E/M codes and payment levels and reducing administrative burdens.”

The changes also will help address physician shortages, according to ACP officials.

“Fewer physicians are going into office-based internal medicine and other primary care disciplines in large part because Medicare and other payers have long undervalued their services and imposed unreasonable documentation requirements,” they wrote. “CMS’s new rule can help reverse this trend at a time when an aging population will need more primary care physicians, especially internal medicine specialists, to care for them.”

Opioid use disorder treatment programs will be covered by Medicare beginning in 2020. Enrolled opioid treatment programs will receive a bundled payment based on weekly episodes of care that cover Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that treat opioid use disorder, the dispensing and administering those medications, counseling, individual and group therapy, and toxicology testing.

The physician fee schedule also includes codes for telehealth services related to the opioid treatment bundle.

CMS also is finalizing updates on physician supervision of physician assistants to give physician assistants “greater flexibility to practice more broadly in the current health care system in accordance with state law and state scope of practice,” the fact sheet notes.

SOURCE: CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2020.

A Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) overhaul and evaluation and management changes to support the care of complex patients highlight the final Medicare physician fee schedule for 2020.

The new MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) framework “aims to align and connect measures and activities across the quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities performance categories of MIPS for different specialties or conditions,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a fact sheet outlining the updates to the Quality Payment Program.

CMS noted that the framework will have measures aimed at population health and public health priorities, as well as reducing the reporting burden of the MIPS program and providing enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.

“We also intend to analyze existing Medicare information so that we can provide clinicians and patients with more information to improve health outcomes,” the agency wrote. “We believe the MVPs framework will help simplify MIPS, create a more cohesive and meaningful participation experience, improve value, reduce clinician burden, and better align with APMs [advanced alternative payment models] to help ease transition between the two tracks.

While the specifics of how the pathways will work are yet to be determined, the goal is to reduce the reporting burden while increasing its clinical applicability

Under the current MIPS structure, clinicians report on a specific number of measures chosen from a menu that may or may not be relevant to the care of patients with a specific disease, such as diabetes.

The MVPs framework will have some “foundation” measures in the first 2 years linked to promoting interoperability and population health that all clinicians will use. These, however, will be coupled with additional measures across the other MIPS categories (quality, cost, and improvement) that are specifically related to diabetes treatment. The expectation is that disease-specific measures plus foundation measures will add up to fewer measures than clinicians currently report, according to CMS.

Over the next 3-5 years, disease-specific measures will be refined and foundation measures expanded to include enhanced performance feedback and patient-reported outcomes.

“We recognize that this will be a significant shift in the way clinicians may potentially participate in MIPS, therefore we want to work closely with clinicians, patients, specialty societies, third parties, and others to establish the MVPs,” CMS officials said.

In the meantime, there are changes to the current MIPS program. Category weighting remains unchanged for the 2020 performance year (payable in 2022), with the performance threshold being 45 points and the exceptional performance threshold being 85 points.

In the quality performance category, the data completeness threshold is increased to 70%, while the agency continues to remove low-bar, standard-of-care process measures and adding new specialty sets, such as audiology, chiropractic medicine, pulmonology, and endocrinology.

In the cost category, 10 new episode-based measures were added to help expand access to this category. In the improvement activities category, CMS reduced barriers to obtaining a patient-centered medical home designation and increased the participation threshold for a practice from a single clinician to 50% of the clinicians in the practice. In the promoting interoperability category, the agency included queries to a prescription drug–monitoring program as an option measure, removed the verify opioid treatment–agreement measure, and reduced the threshold for a group to be considered hospital based from 100% to 75% being hospital based in order for a group to be excluded from reporting measures in this category.

One change not made in the MIPS update is threshold for exclusion from participating in the MIPS program, which has generated continued criticism over the years from the American Medical Group Association, which represents multispecialty practices.

“Overall, CMS expects Part B payment adjustments of 1.4% for those providers who participate in the program,” AMGA officials said in a statement. “However, Congress authorized up to a 9% payment adjustment for the 2020 performance year. While not every provider will achieve the highest possible adjustment, CMS’ continued policy of excluding otherwise eligible providers from participating in MIPS makes it impossible to achieve sustainable payments to cover the cost of participation. Thus, AMGA members have expressed that the program is no longer a viable tool for transitioning to value-based care.”

The physician fee schedule also finalized a number of provisions aimed at reducing administrative burden and increasing the time physicians have with patients. The changes will save clinicians 2.3 million hours per year in burden reduction, according to CMS.

New evaluation and management services (E/M) codes will allow clinicians to choose the appropriate level of coding based on either the medical decision making or time spent with the patient. In 2021, an add-on code will be implemented for prolonged service times for when clinicians spend more time treating complex patients, according to a CMS fact sheet.

Beginning in 2020, clinicians will be paid for care management services for patients with one serious and high-risk condition. Previously, a patient would need at least two serious and high-risk conditions for clinicians to get paid for care management services. For those with multiple chronic conditions, a Medicare-specific code has been added that covers patient visits that last beyond 20 minutes allowed in the current coding for chronic care management services.

The E/M changes are “a significant step in reducing administrative burden that gets in the way of patient care. Now it’s time for vendors and payors to take the necessary steps to align their systems with the E/M office visit code changes by the time the revisions are deployed on Jan. 1, 2021,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement.

The American College of Physicians also applauded the change.

“Medicare has long undervalued E/M codes by internal medicine physicians, family physicians, and other cognitive and primary care physicians,” ACP said in a statement, adding that it is “extremely pleased that CMS’s final payment rules will strengthen primary and cognitive care by improving E/M codes and payment levels and reducing administrative burdens.”

The changes also will help address physician shortages, according to ACP officials.

“Fewer physicians are going into office-based internal medicine and other primary care disciplines in large part because Medicare and other payers have long undervalued their services and imposed unreasonable documentation requirements,” they wrote. “CMS’s new rule can help reverse this trend at a time when an aging population will need more primary care physicians, especially internal medicine specialists, to care for them.”

Opioid use disorder treatment programs will be covered by Medicare beginning in 2020. Enrolled opioid treatment programs will receive a bundled payment based on weekly episodes of care that cover Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that treat opioid use disorder, the dispensing and administering those medications, counseling, individual and group therapy, and toxicology testing.

The physician fee schedule also includes codes for telehealth services related to the opioid treatment bundle.

CMS also is finalizing updates on physician supervision of physician assistants to give physician assistants “greater flexibility to practice more broadly in the current health care system in accordance with state law and state scope of practice,” the fact sheet notes.

SOURCE: CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2020.

A Merit-based Incentive Payment System (MIPS) overhaul and evaluation and management changes to support the care of complex patients highlight the final Medicare physician fee schedule for 2020.

The new MIPS Value Pathways (MVPs) framework “aims to align and connect measures and activities across the quality, cost, promoting interoperability, and improvement activities performance categories of MIPS for different specialties or conditions,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in a fact sheet outlining the updates to the Quality Payment Program.

CMS noted that the framework will have measures aimed at population health and public health priorities, as well as reducing the reporting burden of the MIPS program and providing enhanced data and feedback to clinicians.

“We also intend to analyze existing Medicare information so that we can provide clinicians and patients with more information to improve health outcomes,” the agency wrote. “We believe the MVPs framework will help simplify MIPS, create a more cohesive and meaningful participation experience, improve value, reduce clinician burden, and better align with APMs [advanced alternative payment models] to help ease transition between the two tracks.

While the specifics of how the pathways will work are yet to be determined, the goal is to reduce the reporting burden while increasing its clinical applicability

Under the current MIPS structure, clinicians report on a specific number of measures chosen from a menu that may or may not be relevant to the care of patients with a specific disease, such as diabetes.

The MVPs framework will have some “foundation” measures in the first 2 years linked to promoting interoperability and population health that all clinicians will use. These, however, will be coupled with additional measures across the other MIPS categories (quality, cost, and improvement) that are specifically related to diabetes treatment. The expectation is that disease-specific measures plus foundation measures will add up to fewer measures than clinicians currently report, according to CMS.

Over the next 3-5 years, disease-specific measures will be refined and foundation measures expanded to include enhanced performance feedback and patient-reported outcomes.

“We recognize that this will be a significant shift in the way clinicians may potentially participate in MIPS, therefore we want to work closely with clinicians, patients, specialty societies, third parties, and others to establish the MVPs,” CMS officials said.

In the meantime, there are changes to the current MIPS program. Category weighting remains unchanged for the 2020 performance year (payable in 2022), with the performance threshold being 45 points and the exceptional performance threshold being 85 points.

In the quality performance category, the data completeness threshold is increased to 70%, while the agency continues to remove low-bar, standard-of-care process measures and adding new specialty sets, such as audiology, chiropractic medicine, pulmonology, and endocrinology.

In the cost category, 10 new episode-based measures were added to help expand access to this category. In the improvement activities category, CMS reduced barriers to obtaining a patient-centered medical home designation and increased the participation threshold for a practice from a single clinician to 50% of the clinicians in the practice. In the promoting interoperability category, the agency included queries to a prescription drug–monitoring program as an option measure, removed the verify opioid treatment–agreement measure, and reduced the threshold for a group to be considered hospital based from 100% to 75% being hospital based in order for a group to be excluded from reporting measures in this category.

One change not made in the MIPS update is threshold for exclusion from participating in the MIPS program, which has generated continued criticism over the years from the American Medical Group Association, which represents multispecialty practices.

“Overall, CMS expects Part B payment adjustments of 1.4% for those providers who participate in the program,” AMGA officials said in a statement. “However, Congress authorized up to a 9% payment adjustment for the 2020 performance year. While not every provider will achieve the highest possible adjustment, CMS’ continued policy of excluding otherwise eligible providers from participating in MIPS makes it impossible to achieve sustainable payments to cover the cost of participation. Thus, AMGA members have expressed that the program is no longer a viable tool for transitioning to value-based care.”

The physician fee schedule also finalized a number of provisions aimed at reducing administrative burden and increasing the time physicians have with patients. The changes will save clinicians 2.3 million hours per year in burden reduction, according to CMS.

New evaluation and management services (E/M) codes will allow clinicians to choose the appropriate level of coding based on either the medical decision making or time spent with the patient. In 2021, an add-on code will be implemented for prolonged service times for when clinicians spend more time treating complex patients, according to a CMS fact sheet.

Beginning in 2020, clinicians will be paid for care management services for patients with one serious and high-risk condition. Previously, a patient would need at least two serious and high-risk conditions for clinicians to get paid for care management services. For those with multiple chronic conditions, a Medicare-specific code has been added that covers patient visits that last beyond 20 minutes allowed in the current coding for chronic care management services.

The E/M changes are “a significant step in reducing administrative burden that gets in the way of patient care. Now it’s time for vendors and payors to take the necessary steps to align their systems with the E/M office visit code changes by the time the revisions are deployed on Jan. 1, 2021,” Patrice Harris, MD, president of the American Medical Association, said in a statement.

The American College of Physicians also applauded the change.

“Medicare has long undervalued E/M codes by internal medicine physicians, family physicians, and other cognitive and primary care physicians,” ACP said in a statement, adding that it is “extremely pleased that CMS’s final payment rules will strengthen primary and cognitive care by improving E/M codes and payment levels and reducing administrative burdens.”

The changes also will help address physician shortages, according to ACP officials.

“Fewer physicians are going into office-based internal medicine and other primary care disciplines in large part because Medicare and other payers have long undervalued their services and imposed unreasonable documentation requirements,” they wrote. “CMS’s new rule can help reverse this trend at a time when an aging population will need more primary care physicians, especially internal medicine specialists, to care for them.”

Opioid use disorder treatment programs will be covered by Medicare beginning in 2020. Enrolled opioid treatment programs will receive a bundled payment based on weekly episodes of care that cover Food and Drug Administration–approved medications that treat opioid use disorder, the dispensing and administering those medications, counseling, individual and group therapy, and toxicology testing.

The physician fee schedule also includes codes for telehealth services related to the opioid treatment bundle.

CMS also is finalizing updates on physician supervision of physician assistants to give physician assistants “greater flexibility to practice more broadly in the current health care system in accordance with state law and state scope of practice,” the fact sheet notes.

SOURCE: CMS Medicare Physician Fee Schedule for calendar year 2020.

Letters: Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout

To the Editor: In the September 2019 guest editorial “Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout,” the authors have advanced a thoughtful and provocative hypothesis addressing a salient issue.1 Their argument is that burnout does not accurately capture physician distress. Furthermore, they posit the term burnout focuses remediation strategies at the individual provider level, thereby discounting the contribution of the larger health care system. This is not the first effort to argue that burnout is not a syndrome of mental illness (eg, depression) located within the person but rather a disrupted physician-work relationship.2

As the authors cite, population and practice changes have contributed significantly to physician distress and dissatisfaction. Indeed, recent findings indicate that female physicians may suffer increased prevalence of burnout, which represents a challenge given the growing numbers of women in medicine.3 Unfortunately, by shifting focus almost exclusively to the system level to address burnout, the authors discount a large body of literature examining associations and contributors at the individual and clinic level.

Burnout is conceptualized as consisting of 3 domains: depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and personal accomplishment.4 While this conceptualization may not capture the totality of physician distress, it has provided a body of literature focused on decreasing symptoms of burnout. Successful interventions have been targeted at the individual provider level (ie, stress management, small group discussion, mindfulness) as well as the organizational level (ie, reduction in duty hours, scribes).5,6 Recent studies have also suggested that increasing the occurrence of social encounters that are civil and respectful decreases reported physician burnout.7

Frustration, the annoyance or anger at being unable to change or achieve something, also can be a leading cause of burnout and moral injury. The inability to deal with unresolvable issues due to a lack of skills or inability to create a positive reframe can lead to a constellation of symptoms that are detrimental to the individual provider. Nevertheless, system rigidity, inability to recognitize pain and pressure, and goals perceived as unachievable can also lead to frustration. Physicians may experience growing frustration if they are unable to influence their systems. Thus, experiencing personal frustration, combined with an inability or lack of energy or time to influence a system can snowball.

Just as we counsel our patients that good medical care involves not only engagement with the medical system, but also individual engagement in their care (eg, nutrition, exercise), this problem requires a multicomponent solution. While advocating and working for a system that induces less moral injury, frustration, and burnout, physicians need to examine the resources available to them and their colleagues in a more immediate way.

Physician distress is a serious problem with both personal, patient, occupational, and public health costs. Thus, it is important that we grapple with the complexity of a multiconstruct definition amenable to multilevel interventions. The concept of moral injury is an important component and opens additional lines of both clinical inquiry and intervention. However, in our view, to subsume all burnout under this construct is overly reductive.

In closing, this topic is too important not to discuss. Let the conversations continue!

Lynne Padgett, PhD; and Joao L. Ascensao, MD, PhD

Author affiliations: Departments of Medicine and Mental Health, Washington DC VA Medical Center and Department of Medicine, George Washington University School of Medicine

Correspondence: Lynne Padgett (lynne.padgett@va.gov)

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest with regard to this article.

References

1. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinical distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

2. Epstein RM, Privitera MR. Doing something about physician burnout. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2216-2217.

3. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2019. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Gender-Based-Differences-in-Burnout.pdf. Published May 28, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2019.

4. Eckleberry-Hunt J Kirkpatrick H, Barbera T. The problems with burnout research. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):367-370.

5. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281.

6. Squiers JJ, Lobdell KW, Fann JI, DiMaio JM. Physician burnout: are we treating the symptom instead of the disease? Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(4):1117-1122.

7. Maslach C, Leiter MP. New insights into burnout and health care: strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):160-163.

To the Editor: We applaud Dean and her colleagues for their thought-provoking commentary on clinicians’ distress, a problem that has surged in recent years and has now reached epidemic proportions.1 Their argument focuses on the language used to define and frame clinical distress. Do we label this distress as burnout, as moral injury, or as something else? Moral injury occurs any time clinicians are impeded from doing the right thing at the right time in the right way; or even worse, doing the wrong thing to serve the needs of health system stakeholders other than the patient. These other stakeholders may include administrators, corporations, insurance adjusters, and others.

Naming the problem correctly is crucial to finding the solution. The name frames the discussion and impacts the solution. Burnout implies difficulty coping with the many stresses of health care and of personal responsibility for the problem. The solution would therefore be to help individuals to cope with their stresses. Moral injury on the other hand implies a corrupt system; thereby, reframing the discussion to systems issues and suggesting solutions by changing the business of health care delivery.

These authors state that current clinical distress is due to moral injury and not to burnout. Therefore, the business in which health care is performed needs to change.

The authors define the drivers of moral injury in our current system, mostly as (1) a massive information technology overload that has largely overtaken the patient as center of attention; and (2) the profit motive of the health care corporation and its shareholders. A focus on making profits has increased in the wake of falling reimbursements; the result is pressure on clinicians to see more patients more quickly and to do more even when not necessary. This has diverted the focus on healing patients to a focus on making profits. These major drivers of clinician distress—the electronic health record and the pressure to bill more—are fundamentally driven by the corporatization of American medicine in which profit is the measured outcome.

Thus rather than having their highest loyalty to patients and their families, clinicians now have other loyalties—the electronic health record, insurers, the hospital, the health care system, and even their own salaries.

Therein lies the moral injury felt by increasing numbers of clinicians, leading to soaring rates of clinical distress. Many physicians are now recognizing moral injury as the basis of their pain. For example, Gawande has described unceasing computer data entry as a cause of physician distress and physician loneliness in the interesting essay, “Why Doctors Hate Their Computers.”2 Topol has suggested that corporate interference and attention away from patient care is a reason doctors should unite and organize for a more healthful environment.3 Ofri has gone so far as to suggest that the health care system is surviving because it can exploit its physicians for every drop of energy, diverting the focus of clinical encounters on billing rather than healing.4 However, it may be simplistic to imply or state that all clinical distress is related to moral injury. Other factors in caring for the sick and dying also can cause distress to health care providers. Physicians work long, hard hours and listen to many stories of distress and suffering from patients. Some of this is internalized and processed as one’s own suffering. Clinicians also have enormous amounts of information to absorb and assimilate, keep long hours, and are often sleep deprived, all of which may harm their well-being. In addition, clinicians may have work/life imbalances, be hesitant to reveal their weaknesses, and have perfectionist personalities. Still other factors may also be involved, such as a hostile environment in which managers can overuse their power; racism that can limit opportunities for advancement; and/or a family-unfriendly environment.

Just as the treatment of cancer depends on good surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy as well as reducing underlying predisposing cause (ie, smoking, drinking, obesity, antiviral therapy) and leading a healthy lifestyle, so too treatment of clinical distress needs a multipronged approach. Fixing the business framework is an important step forward but may not always be enough. We agree with the authors’ suggestions for improvement: bringing administrators and clinicians into conversation with each other, making clinician satisfaction a financial priority, assuring that physician leaders have cell phone numbers of their legislators, and reestablishing a sense of community among clinicians. However, none of these goals will be easy to accomplish and some may be impossible to realize in some settings.

A necessary corollary to the suggestions by Dean and colleagues is research. Much research is needed to discover all of the factors of clinician distress, whatever we name the problem. We need to know vulnerabilities of different populations of clinicians and differences in prevalence in different types of health care systems.

It is likely that physicians in a government-owned health care system, such as the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals, have lower distress since there are no corporate interests or profit motives. In our experience, we have noted that many VA providers are expatriates of private health care systems due to their moral distress. If profit making and corporatization are important factors in distress, then clinicians in the VA system should have much lower distress; however, this is not known.

We also need research in pilot projects that relieve clinician distress. These could relate to collegial activities to bring physicians—and administrators—together in community, allowing more time with patients than the usual 15-minute allotments, allowing more time for creative, narrative experiences in medicine, developing forums for discussion and resolution of distress-inducing situations, etc.

An important yet overlooked issue in this discussion is that clinician distress, regardless of its name or cause, is a public health crisis. Clinician distress not only affects the clinician most directly and most crucially, but also affects every person in his/her community. Physicians who are distressed for whatever reason deliver less adequate care, make more medical errors, and are less invested in their patients. Patients of distressed clinicians have less favorable outcomes and suffer more. Medical errors are now the third leading cause of death in the US. Much of this is due to inadequate care by focusing attention on profit-making over health improvement and to clinician distress. Clinician distress due to moral injury or any other factor is a public health crisis and needs much more attention, research, and prioritization of clinician satisfaction.

Paulette Mehta, MD, MPH; and Jay Mehta, PhD

Author Affiliations: Central Arkansas Veterans Health Care System; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Correspondence: Paulette Mehta (paulette.mehta@va.gov)

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest with regard to this article.

References

1. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinical distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

2. Gawande A. Why doctors hate their computers. New Yorker. November 12, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/11/12/why-doctors-hate-their-computers. Accessed October 16, 2019.

3. Topol E. Why doctors should organize. New Yorker. August 5, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-inquiry/why-doctors-should-organize. Accessed October 16, 2019.

4. Ofri D. The business of healthcare depends on exploiting doctors and nurses. The New York Times. June 8, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/08/opinion/sunday/hospitals-doctors-nurses-burnout.html. Accessed October 16, 2019.

To the Editor: The September 2019 editorial “Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout” argues for a renaming of what has been called burnout to moral injury.1 The article by Dean, Talbot, and Dean compares the experience of health care providers to soldiers and other service members who have served in combat and suffer as a result of their experiences. I would like to comment on 2 areas: Whether the term burnout should be replaced with moral injury; and the adequacy of the recommendations made by Dean, Talbot, and Dean.

Briefly, my own credentials to opine on the topic include being both a physician and a soldier. I served in the US Army as a psychiatrist from 1986 to 2010 and deployed to various hazardous locations, including South Korea, Somalia, Iraq, and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Since my retirement from the Army I have worked as a psychiatrist on different front lines, with both veterans and the chronically mentally ill and often homeless population.

Moral injury is a term that was popularized by Johnathan Shay after the Vietnam War, especially in his masterful book Achilles in Vietnam.1 Most authors who have written on the subject of moral injury, including myself, think of it as feelings of guilt and shame related to (1) killing civilians (especially children or innocents); (2) surviving while other comrades did not; and/or (3) feeling betrayed by the government they served.2,3

While also arising in combat settings, moral injury is related but separate from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It comes from an affront to our morals rather than our physical well-being. It is not considered a medical diagnosis, treatments are experimental, and the literature is anecdotal.

I have mixed feelings about equating the moral injury from combat to working as a physician or other health care provider. On the one hand, certainly health care providers may sacrifice health and safety to taking care of patients. They may feel guilty when they cannot do enough for their patients. But does it rise to the same level as actually combat and having numerous comrades killed or maimed?

On the other hand, working on an inpatient psychiatry ward with an inner-city population who generally have severe mental illness and are often on phencyclidine and related drugs, has its own share of risks. Unfortunately, physical attacks on staff are way too common.

The term burnout also has a robust background of research into both causes and possible solutions. Indeed, there was even a journal devoted to it: Burnout Research.4 Moral injury research is on different populations, and generally the remedies are focused more on spiritual and existential support.

Which brings me to the recommendations and solutions part of the editorial. I agree that yoga and meditation, while beneficial, do not curb the feelings of frustration and betrayal that often arise when you cannot treat patients the way you feel they deserve. The recommendations listed in the editorial are a start, but much more should be done.

Now comes the hard part. Specifically, what more should be done? All the easy solutions have already been tried. Ones that would really make a difference, such as making an electronic health record that allows you to still look at and connect to the patient, seem to elude us. Many of us in the health care industry would love to have a single payer system across the board, to avoid all the inequities cited in the article. But health care, like climate change, is mired in our political deadlocks.

Therefore, I will finish by focusing on one of their recommendations, which is achievable: tie the incentives for the executive leadership to the satisfaction of health care providers, as is done for patient satisfaction. That is both doable and will benefit various institutions in the long run. Health care providers will be more likely to stay in a health care system and thus patient satisfaction improves. Win-win.

COL (Ret) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, USA

Author Affiliation: Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Correspondence: Elspeth Cameron Ritchie (elspethcameronritchie@gmail.com)

Disclosures: The author reports no conflict of interest with regard to this article.

References

1. Shay J. Achilles in Vietnam: Combat Trauma and the Undoing of Character. New York: Atheneum; 1994.

2. Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin. Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695-706.

3. Ritchie EC. Moral injury: a profound sense of alienation and abject shame. Time. April 17, 2013. http://nation.time.com/2013/04/17/moral-injury-a-profound-sense-of-alienation-and-abject-shame.

4. Burnout Research. 2014;1(1):1-56. https://www.sciencedirect.com/journal/burnout-research/vol/1/issue/1. Accessed October 17, 2019.

Response: We appreciate the very thoughtful and thorough responses of Mehta. Mehta, Padgett, Ascensao, and Ritchie. Common themes in the responses were the suggestion that supplanting the term burnout with moral injury may not be appropriate and that changing the underlying drivers of distress requires a multifaceted approach, which is likely to require prolonged effort. We agree with both of these themes, believing the concept of moral injury and mitigation strategies do not benefit from reductionism.

Burnout is a nonspecific symptom constellation of emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a lack of a sense of accomplishment.1 Because it is nonspecific, the symptoms can arise from any number of situations, not only moral injury. However, from our conversations over the past 15 months, moral injury fuels a large percentage of burnout in health care. In a recent informal survey conducted at the ORExcellence meeting, almost all respondents believed they were experiencing moral injury rather than burnout when both terms were explained. When clinicians are physically and emotionally exhausted with battling a broken system in their efforts to provide good care—when they have incurred innumerable moral insults, amassing to a moral injury—many give up. This is the end stage of moral injury, or burnout.We absolutely agree research is necessary to validate this concept, which has been applied only to health care since July 2018. We are pursuing various avenues of inquiry and are validating a new assessment tool. But we do not believe that intervention must wait until there are data to support what resonates so profoundly with so many and, as we have heard dozens of times, “finally gives language to my experience.”Finally, we would not suggest that civilian physician experience is equivalent to combat experience. But just as there are multiple etiologies for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), such as combat exposure, physical abuse, sexual assault, there are likely multiple ways one can incur moral injury. Witnessing or participating in a situation that transgresses deeply held moral beliefs is the prerequisite for moral injury rather than physical danger. In different contexts, physicians and service members may ultimately face similar accumulated risk to their moral integrity, though of widely disparate intensity, frequency, and duration. Physicians face low-intensity, high-frequency threats over years; service members more often face high-intensity, less frequent threats during time-limited deployments. Just because moral injury was first applied to combat veterans—as was PTSD—does not mean we should limit the use of a powerfully resonant concept to a military population any more than we limited the use of Letterman’s ambulances or Morel’s tourniquets to the battlefield.2,3

Wendy Dean, MD; and Simon Talbot, MD

Author affiliations: Wendy Dean is President and co-founder of Moral Injury of Healthcare. Simon Talbot is a reconstructive plastic surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital and associate professor of surgery at Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts.

Correspondence: Wendy Dean (wdean@moralinjury. Healthcare,@WDeanMD)

Disclosures: Wendy Dean and Simon Talbot founded Moral Injury of Healthcare, a nonprofit organization; they report no other actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

References

1. Freudenberger HJ. The staff burn-out syndrome in alternative institutions. Psychother Theory Res Pract. 1975;12(1):73-82.

2. Place RJ. The strategic genius of Jonathan Letterman: the relevancy of the American Civil War to current health care policy makers. Mil Med. 2015;180(3):259-262.

3. Welling DR, McKay PL, Rasmussen TE, Rich NM. A brief history of the tourniquet. J Vasc Surg. 2012;55(1):286-290.

To the Editor: In the September 2019 guest editorial “Reframing Clinician Distress: Moral Injury Not Burnout,” the authors have advanced a thoughtful and provocative hypothesis addressing a salient issue.1 Their argument is that burnout does not accurately capture physician distress. Furthermore, they posit the term burnout focuses remediation strategies at the individual provider level, thereby discounting the contribution of the larger health care system. This is not the first effort to argue that burnout is not a syndrome of mental illness (eg, depression) located within the person but rather a disrupted physician-work relationship.2

As the authors cite, population and practice changes have contributed significantly to physician distress and dissatisfaction. Indeed, recent findings indicate that female physicians may suffer increased prevalence of burnout, which represents a challenge given the growing numbers of women in medicine.3 Unfortunately, by shifting focus almost exclusively to the system level to address burnout, the authors discount a large body of literature examining associations and contributors at the individual and clinic level.

Burnout is conceptualized as consisting of 3 domains: depersonalization, emotional exhaustion, and personal accomplishment.4 While this conceptualization may not capture the totality of physician distress, it has provided a body of literature focused on decreasing symptoms of burnout. Successful interventions have been targeted at the individual provider level (ie, stress management, small group discussion, mindfulness) as well as the organizational level (ie, reduction in duty hours, scribes).5,6 Recent studies have also suggested that increasing the occurrence of social encounters that are civil and respectful decreases reported physician burnout.7

Frustration, the annoyance or anger at being unable to change or achieve something, also can be a leading cause of burnout and moral injury. The inability to deal with unresolvable issues due to a lack of skills or inability to create a positive reframe can lead to a constellation of symptoms that are detrimental to the individual provider. Nevertheless, system rigidity, inability to recognitize pain and pressure, and goals perceived as unachievable can also lead to frustration. Physicians may experience growing frustration if they are unable to influence their systems. Thus, experiencing personal frustration, combined with an inability or lack of energy or time to influence a system can snowball.

Just as we counsel our patients that good medical care involves not only engagement with the medical system, but also individual engagement in their care (eg, nutrition, exercise), this problem requires a multicomponent solution. While advocating and working for a system that induces less moral injury, frustration, and burnout, physicians need to examine the resources available to them and their colleagues in a more immediate way.

Physician distress is a serious problem with both personal, patient, occupational, and public health costs. Thus, it is important that we grapple with the complexity of a multiconstruct definition amenable to multilevel interventions. The concept of moral injury is an important component and opens additional lines of both clinical inquiry and intervention. However, in our view, to subsume all burnout under this construct is overly reductive.

In closing, this topic is too important not to discuss. Let the conversations continue!

Lynne Padgett, PhD; and Joao L. Ascensao, MD, PhD

Author affiliations: Departments of Medicine and Mental Health, Washington DC VA Medical Center and Department of Medicine, George Washington University School of Medicine

Correspondence: Lynne Padgett (lynne.padgett@va.gov)

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest with regard to this article.

References

1. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinical distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

2. Epstein RM, Privitera MR. Doing something about physician burnout. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2216-2217.

3. Templeton K, Bernstein CA, Sukhera J, et al. Gender-based differences in burnout: issues faced by women physicians. NAM Perspectives. Discussion Paper. Washington, DC: National Academy of Medicine; 2019. https://nam.edu/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Gender-Based-Differences-in-Burnout.pdf. Published May 28, 2019. Accessed October 10, 2019.

4. Eckleberry-Hunt J Kirkpatrick H, Barbera T. The problems with burnout research. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):367-370.

5. West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281.

6. Squiers JJ, Lobdell KW, Fann JI, DiMaio JM. Physician burnout: are we treating the symptom instead of the disease? Ann Thorac Surg. 2017;104(4):1117-1122.

7. Maslach C, Leiter MP. New insights into burnout and health care: strategies for improving civility and alleviating burnout. Med Teach. 2017;39(2):160-163.

To the Editor: We applaud Dean and her colleagues for their thought-provoking commentary on clinicians’ distress, a problem that has surged in recent years and has now reached epidemic proportions.1 Their argument focuses on the language used to define and frame clinical distress. Do we label this distress as burnout, as moral injury, or as something else? Moral injury occurs any time clinicians are impeded from doing the right thing at the right time in the right way; or even worse, doing the wrong thing to serve the needs of health system stakeholders other than the patient. These other stakeholders may include administrators, corporations, insurance adjusters, and others.

Naming the problem correctly is crucial to finding the solution. The name frames the discussion and impacts the solution. Burnout implies difficulty coping with the many stresses of health care and of personal responsibility for the problem. The solution would therefore be to help individuals to cope with their stresses. Moral injury on the other hand implies a corrupt system; thereby, reframing the discussion to systems issues and suggesting solutions by changing the business of health care delivery.

These authors state that current clinical distress is due to moral injury and not to burnout. Therefore, the business in which health care is performed needs to change.

The authors define the drivers of moral injury in our current system, mostly as (1) a massive information technology overload that has largely overtaken the patient as center of attention; and (2) the profit motive of the health care corporation and its shareholders. A focus on making profits has increased in the wake of falling reimbursements; the result is pressure on clinicians to see more patients more quickly and to do more even when not necessary. This has diverted the focus on healing patients to a focus on making profits. These major drivers of clinician distress—the electronic health record and the pressure to bill more—are fundamentally driven by the corporatization of American medicine in which profit is the measured outcome.

Thus rather than having their highest loyalty to patients and their families, clinicians now have other loyalties—the electronic health record, insurers, the hospital, the health care system, and even their own salaries.

Therein lies the moral injury felt by increasing numbers of clinicians, leading to soaring rates of clinical distress. Many physicians are now recognizing moral injury as the basis of their pain. For example, Gawande has described unceasing computer data entry as a cause of physician distress and physician loneliness in the interesting essay, “Why Doctors Hate Their Computers.”2 Topol has suggested that corporate interference and attention away from patient care is a reason doctors should unite and organize for a more healthful environment.3 Ofri has gone so far as to suggest that the health care system is surviving because it can exploit its physicians for every drop of energy, diverting the focus of clinical encounters on billing rather than healing.4 However, it may be simplistic to imply or state that all clinical distress is related to moral injury. Other factors in caring for the sick and dying also can cause distress to health care providers. Physicians work long, hard hours and listen to many stories of distress and suffering from patients. Some of this is internalized and processed as one’s own suffering. Clinicians also have enormous amounts of information to absorb and assimilate, keep long hours, and are often sleep deprived, all of which may harm their well-being. In addition, clinicians may have work/life imbalances, be hesitant to reveal their weaknesses, and have perfectionist personalities. Still other factors may also be involved, such as a hostile environment in which managers can overuse their power; racism that can limit opportunities for advancement; and/or a family-unfriendly environment.

Just as the treatment of cancer depends on good surgery, radiation and/or chemotherapy as well as reducing underlying predisposing cause (ie, smoking, drinking, obesity, antiviral therapy) and leading a healthy lifestyle, so too treatment of clinical distress needs a multipronged approach. Fixing the business framework is an important step forward but may not always be enough. We agree with the authors’ suggestions for improvement: bringing administrators and clinicians into conversation with each other, making clinician satisfaction a financial priority, assuring that physician leaders have cell phone numbers of their legislators, and reestablishing a sense of community among clinicians. However, none of these goals will be easy to accomplish and some may be impossible to realize in some settings.

A necessary corollary to the suggestions by Dean and colleagues is research. Much research is needed to discover all of the factors of clinician distress, whatever we name the problem. We need to know vulnerabilities of different populations of clinicians and differences in prevalence in different types of health care systems.

It is likely that physicians in a government-owned health care system, such as the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) hospitals, have lower distress since there are no corporate interests or profit motives. In our experience, we have noted that many VA providers are expatriates of private health care systems due to their moral distress. If profit making and corporatization are important factors in distress, then clinicians in the VA system should have much lower distress; however, this is not known.

We also need research in pilot projects that relieve clinician distress. These could relate to collegial activities to bring physicians—and administrators—together in community, allowing more time with patients than the usual 15-minute allotments, allowing more time for creative, narrative experiences in medicine, developing forums for discussion and resolution of distress-inducing situations, etc.

An important yet overlooked issue in this discussion is that clinician distress, regardless of its name or cause, is a public health crisis. Clinician distress not only affects the clinician most directly and most crucially, but also affects every person in his/her community. Physicians who are distressed for whatever reason deliver less adequate care, make more medical errors, and are less invested in their patients. Patients of distressed clinicians have less favorable outcomes and suffer more. Medical errors are now the third leading cause of death in the US. Much of this is due to inadequate care by focusing attention on profit-making over health improvement and to clinician distress. Clinician distress due to moral injury or any other factor is a public health crisis and needs much more attention, research, and prioritization of clinician satisfaction.

Paulette Mehta, MD, MPH; and Jay Mehta, PhD

Author Affiliations: Central Arkansas Veterans Health Care System; University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences

Correspondence: Paulette Mehta (paulette.mehta@va.gov)

Disclosures: The authors report no conflict of interest with regard to this article.

References

1. Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinical distress: moral injury not burnout. Fed Pract. 2019;36(9):400-402.

2. Gawande A. Why doctors hate their computers. New Yorker. November 12, 2018. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2018/11/12/why-doctors-hate-their-computers. Accessed October 16, 2019.

3. Topol E. Why doctors should organize. New Yorker. August 5, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/annals-of-inquiry/why-doctors-should-organize. Accessed October 16, 2019.

4. Ofri D. The business of healthcare depends on exploiting doctors and nurses. The New York Times. June 8, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/08/opinion/sunday/hospitals-doctors-nurses-burnout.html. Accessed October 16, 2019.

To the Editor: The September 2019 editorial “Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout” argues for a renaming of what has been called burnout to moral injury.1 The article by Dean, Talbot, and Dean compares the experience of health care providers to soldiers and other service members who have served in combat and suffer as a result of their experiences. I would like to comment on 2 areas: Whether the term burnout should be replaced with moral injury; and the adequacy of the recommendations made by Dean, Talbot, and Dean.

Briefly, my own credentials to opine on the topic include being both a physician and a soldier. I served in the US Army as a psychiatrist from 1986 to 2010 and deployed to various hazardous locations, including South Korea, Somalia, Iraq, and Guantanamo Bay, Cuba. Since my retirement from the Army I have worked as a psychiatrist on different front lines, with both veterans and the chronically mentally ill and often homeless population.

Moral injury is a term that was popularized by Johnathan Shay after the Vietnam War, especially in his masterful book Achilles in Vietnam.1 Most authors who have written on the subject of moral injury, including myself, think of it as feelings of guilt and shame related to (1) killing civilians (especially children or innocents); (2) surviving while other comrades did not; and/or (3) feeling betrayed by the government they served.2,3

While also arising in combat settings, moral injury is related but separate from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It comes from an affront to our morals rather than our physical well-being. It is not considered a medical diagnosis, treatments are experimental, and the literature is anecdotal.

I have mixed feelings about equating the moral injury from combat to working as a physician or other health care provider. On the one hand, certainly health care providers may sacrifice health and safety to taking care of patients. They may feel guilty when they cannot do enough for their patients. But does it rise to the same level as actually combat and having numerous comrades killed or maimed?

On the other hand, working on an inpatient psychiatry ward with an inner-city population who generally have severe mental illness and are often on phencyclidine and related drugs, has its own share of risks. Unfortunately, physical attacks on staff are way too common.

The term burnout also has a robust background of research into both causes and possible solutions. Indeed, there was even a journal devoted to it: Burnout Research.4 Moral injury research is on different populations, and generally the remedies are focused more on spiritual and existential support.

Which brings me to the recommendations and solutions part of the editorial. I agree that yoga and meditation, while beneficial, do not curb the feelings of frustration and betrayal that often arise when you cannot treat patients the way you feel they deserve. The recommendations listed in the editorial are a start, but much more should be done.

Now comes the hard part. Specifically, what more should be done? All the easy solutions have already been tried. Ones that would really make a difference, such as making an electronic health record that allows you to still look at and connect to the patient, seem to elude us. Many of us in the health care industry would love to have a single payer system across the board, to avoid all the inequities cited in the article. But health care, like climate change, is mired in our political deadlocks.

Therefore, I will finish by focusing on one of their recommendations, which is achievable: tie the incentives for the executive leadership to the satisfaction of health care providers, as is done for patient satisfaction. That is both doable and will benefit various institutions in the long run. Health care providers will be more likely to stay in a health care system and thus patient satisfaction improves. Win-win.

COL (Ret) Elspeth Cameron Ritchie, MD, MPH, USA

Author Affiliation: Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences

Correspondence: Elspeth Cameron Ritchie (elspethcameronritchie@gmail.com)

Disclosures: The author reports no conflict of interest with regard to this article.

References