User login

‘Genetic’ height linked to peripheral neuropathy and certain skin and bone infections

, according to a study published in PLOS Genetics.

Prior studies have investigated height as a risk factor for chronic diseases, such as a higher risk for atrial fibrillation and a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. It’s been consistently difficult, however, to eliminate the confounding influences of diet, socioeconomics, lifestyle behaviors, and other environmental factors that may interfere with a person’s reaching their expected height based on their genes.

This study, however, was able to better parse those differences by using Mendelian randomization within the comprehensive clinical and genetic dataset of a national health care system biobank. Mendelian randomization uses “genetic instruments for exposures of interest under the assumption that genotype is less susceptible to confounding than measured exposures,” the authors explained. The findings confirmed previously suspected associations between height and a range of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions as well as revealing new associations with several other conditions.

Prior associations confirmed, new associations uncovered

The results confirmed that being tall is linked to a higher risk of atrial fibrillation and varicose veins, and a lower risk of coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. The study also uncovered new associations between greater height and a higher risk of peripheral neuropathy, which is caused by damage to nerves on the extremities, as well as skin and bone infections, such as leg and foot ulcers.

The meta-analysis “identified five additional traits associated with genetically-predicted height,” wrote Sridharan Raghavan, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and colleagues. “Two were genitourinary conditions – erectile dysfunction and urinary retention – that can be associated with neuropathy, and a third was a phecode for nonspecific skin disorders that may be related to skin infections – consistent with the race/ethnicity stratified results.”

Removing potential confounders

F. Perry Wilson, MD, associate professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who was not involved in the study, said the findings were not particularly surprising overall, but it’s striking that the researchers had ”such a large cohort with such detailed electronic health records allowing for the comparison of genetic height with a variety of clinical outcomes.” He also noted the study’s strength in using Mendelian randomization so that the exposure is the predicted genetic height instead of a person’s measured height.

“This is key, since lots of things affect actual height – nutrition is an important one that could certainly be linked to disease as well,” Dr. Wilson said. ”By using genetic height, the authors remove these potential confounders. Since genetic height is “assigned” at birth (or conception), there is little opportunity for confounding. Of course, it is possible that some of the gene variants used to predict genetic height actually do something else, such as make you seek out less nutritious meals, but by and large this is how these types of studies need to be done.”

Height may impact over 100 clinical traits

The study relied on data from the U.S. Veteran Affairs Million Veteran Program with 222,300 non-Hispanic White and 58,151 non-Hispanic Black participants. The researchers first estimated the likelihood of participants’ genetic height based on 3,290 genetic variants determined to affect genetic height in a recent European-ancestry genome-wide meta-analysis. Then they compared these estimates with participants’ actual height in the VA medical record, adjusting for age, sex, and other genetic characteristics.

In doing so, the researchers found 345 clinical traits that were associated with the actual measured height in White participants plus another 17 clinical trials linked to actual measured height in Black participants. An overall 127 of these clinical traits were significantly associated with White participants’ genetically predicted height, and two of them were significantly associated with Black participants’ genetically predicted height.

In analyzing all these data together, the researchers were largely able to separate out those associations between genetically predicted height and certain health conditions from those associations between health conditions and a person’s actual measured height. They also determined that including body mass index as a covariate had little impact on the results. The researchers conducted the appropriate statistical correction to ensure the use of so many variables did not result in spurious statistical significance in some associations.

“Using genetic methods applied to the VA Million Veteran Program, we found evidence that adult height may impact over 100 clinical traits, including several conditions associated with poor outcomes and quality of life – peripheral neuropathy, lower extremity ulcers, and chronic venous insufficiency. We conclude that height may be an unrecognized nonmodifiable risk factor for several common conditions in adults.”

Height linked with health conditions

Genetically predicted height predicted a reduced risk of hyperlipidemia and hypertension independent of coronary heart disease, the analysis revealed. Genetically predicted height was also linked to an approximately 51% increased risk of atrial fibrillation in participants without coronary heart disease but, paradoxically, only a 39% increased risk in those with coronary heart disease, despite coronary heart disease being a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Genetically predicted height was also associated with a greater risk of varicose veins in the legs and deep vein thrombosis.

Another novel association uncovered by the analysis was between women’s genetically predicted height and both asthma and nonspecific peripheral nerve disorders. “Whether these associations reflect differences by sex in disease pathophysiology related to height may warrant exploration in a sample with better balance between men and women,” the authors wrote. “In sum, our results suggest that an individual’s height may warrant consideration as a nonmodifiable predictor for several common conditions, particularly those affecting peripheral/distal extremities that are most physically impacted by tall stature.”

A substantial limitation of the study was its homogeneity of participants, who were 92% male with an average height of 176 cm and an average BMI of 30.1. The Black participants tended to be younger, with an average age of 58 compared with 64 years in the White participants, but the groups were otherwise similar in height and weight.* The database included data from Hispanic participants, but the researchers excluded these data because of the small sample size.

The smaller dataset for Black participants was a limitation as well as the fact that the genome-wide association study the researchers relied on came from a European population, which may not be as accurate in people with other ancestry, Dr. Wilson said. The bigger limitation, however, is what the findings’ clinical relevance is.

What does it all mean?

“Genetic height is in your genes – there is nothing to be done about it – so it is more of academic interest than clinical interest,” Dr. Wilson said. It’s not even clear whether incorporating a person’s height – actual or genetically predicted, if it could be easily determined for each person – into risk calculators. ”To know whether it would be beneficial to use height (or genetic height) as a risk factor, you’d need to examine each condition of interest, adjusting for all known risk factors, to see if height improved the prediction,” Dr. Wilson said. “I suspect for most conditions, the well-known risk factors would swamp height. For example, high genetic height might truly increase risk for neuropathy. But diabetes might increase the risk so much more that height is not particularly relevant.”

On the other hand, the fact that height in general has any potential influence at all on disease risk may inspire physicians to consider other risk factors in especially tall individuals.

”Physicians may find it interesting that we have some confirmation that height does increase the risk of certain conditions,” Dr. Wilson said. “While this is unlikely to dramatically change practice, they may be a bit more diligent in looking for other relevant risk factors for the diseases found in this study in their very tall patients.”

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, the Boettcher Foundation’s Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Program, the National Institutes of Health, and a Linda Pechenik Montague Investigator award. One study coauthor is a full-time employee of Novartis Institutes of Biomedical Research. The other authors and Dr. Wilson had no disclosures.

*Correction, 6/29/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the average age of Black participants.

, according to a study published in PLOS Genetics.

Prior studies have investigated height as a risk factor for chronic diseases, such as a higher risk for atrial fibrillation and a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. It’s been consistently difficult, however, to eliminate the confounding influences of diet, socioeconomics, lifestyle behaviors, and other environmental factors that may interfere with a person’s reaching their expected height based on their genes.

This study, however, was able to better parse those differences by using Mendelian randomization within the comprehensive clinical and genetic dataset of a national health care system biobank. Mendelian randomization uses “genetic instruments for exposures of interest under the assumption that genotype is less susceptible to confounding than measured exposures,” the authors explained. The findings confirmed previously suspected associations between height and a range of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions as well as revealing new associations with several other conditions.

Prior associations confirmed, new associations uncovered

The results confirmed that being tall is linked to a higher risk of atrial fibrillation and varicose veins, and a lower risk of coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. The study also uncovered new associations between greater height and a higher risk of peripheral neuropathy, which is caused by damage to nerves on the extremities, as well as skin and bone infections, such as leg and foot ulcers.

The meta-analysis “identified five additional traits associated with genetically-predicted height,” wrote Sridharan Raghavan, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and colleagues. “Two were genitourinary conditions – erectile dysfunction and urinary retention – that can be associated with neuropathy, and a third was a phecode for nonspecific skin disorders that may be related to skin infections – consistent with the race/ethnicity stratified results.”

Removing potential confounders

F. Perry Wilson, MD, associate professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who was not involved in the study, said the findings were not particularly surprising overall, but it’s striking that the researchers had ”such a large cohort with such detailed electronic health records allowing for the comparison of genetic height with a variety of clinical outcomes.” He also noted the study’s strength in using Mendelian randomization so that the exposure is the predicted genetic height instead of a person’s measured height.

“This is key, since lots of things affect actual height – nutrition is an important one that could certainly be linked to disease as well,” Dr. Wilson said. ”By using genetic height, the authors remove these potential confounders. Since genetic height is “assigned” at birth (or conception), there is little opportunity for confounding. Of course, it is possible that some of the gene variants used to predict genetic height actually do something else, such as make you seek out less nutritious meals, but by and large this is how these types of studies need to be done.”

Height may impact over 100 clinical traits

The study relied on data from the U.S. Veteran Affairs Million Veteran Program with 222,300 non-Hispanic White and 58,151 non-Hispanic Black participants. The researchers first estimated the likelihood of participants’ genetic height based on 3,290 genetic variants determined to affect genetic height in a recent European-ancestry genome-wide meta-analysis. Then they compared these estimates with participants’ actual height in the VA medical record, adjusting for age, sex, and other genetic characteristics.

In doing so, the researchers found 345 clinical traits that were associated with the actual measured height in White participants plus another 17 clinical trials linked to actual measured height in Black participants. An overall 127 of these clinical traits were significantly associated with White participants’ genetically predicted height, and two of them were significantly associated with Black participants’ genetically predicted height.

In analyzing all these data together, the researchers were largely able to separate out those associations between genetically predicted height and certain health conditions from those associations between health conditions and a person’s actual measured height. They also determined that including body mass index as a covariate had little impact on the results. The researchers conducted the appropriate statistical correction to ensure the use of so many variables did not result in spurious statistical significance in some associations.

“Using genetic methods applied to the VA Million Veteran Program, we found evidence that adult height may impact over 100 clinical traits, including several conditions associated with poor outcomes and quality of life – peripheral neuropathy, lower extremity ulcers, and chronic venous insufficiency. We conclude that height may be an unrecognized nonmodifiable risk factor for several common conditions in adults.”

Height linked with health conditions

Genetically predicted height predicted a reduced risk of hyperlipidemia and hypertension independent of coronary heart disease, the analysis revealed. Genetically predicted height was also linked to an approximately 51% increased risk of atrial fibrillation in participants without coronary heart disease but, paradoxically, only a 39% increased risk in those with coronary heart disease, despite coronary heart disease being a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Genetically predicted height was also associated with a greater risk of varicose veins in the legs and deep vein thrombosis.

Another novel association uncovered by the analysis was between women’s genetically predicted height and both asthma and nonspecific peripheral nerve disorders. “Whether these associations reflect differences by sex in disease pathophysiology related to height may warrant exploration in a sample with better balance between men and women,” the authors wrote. “In sum, our results suggest that an individual’s height may warrant consideration as a nonmodifiable predictor for several common conditions, particularly those affecting peripheral/distal extremities that are most physically impacted by tall stature.”

A substantial limitation of the study was its homogeneity of participants, who were 92% male with an average height of 176 cm and an average BMI of 30.1. The Black participants tended to be younger, with an average age of 58 compared with 64 years in the White participants, but the groups were otherwise similar in height and weight.* The database included data from Hispanic participants, but the researchers excluded these data because of the small sample size.

The smaller dataset for Black participants was a limitation as well as the fact that the genome-wide association study the researchers relied on came from a European population, which may not be as accurate in people with other ancestry, Dr. Wilson said. The bigger limitation, however, is what the findings’ clinical relevance is.

What does it all mean?

“Genetic height is in your genes – there is nothing to be done about it – so it is more of academic interest than clinical interest,” Dr. Wilson said. It’s not even clear whether incorporating a person’s height – actual or genetically predicted, if it could be easily determined for each person – into risk calculators. ”To know whether it would be beneficial to use height (or genetic height) as a risk factor, you’d need to examine each condition of interest, adjusting for all known risk factors, to see if height improved the prediction,” Dr. Wilson said. “I suspect for most conditions, the well-known risk factors would swamp height. For example, high genetic height might truly increase risk for neuropathy. But diabetes might increase the risk so much more that height is not particularly relevant.”

On the other hand, the fact that height in general has any potential influence at all on disease risk may inspire physicians to consider other risk factors in especially tall individuals.

”Physicians may find it interesting that we have some confirmation that height does increase the risk of certain conditions,” Dr. Wilson said. “While this is unlikely to dramatically change practice, they may be a bit more diligent in looking for other relevant risk factors for the diseases found in this study in their very tall patients.”

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, the Boettcher Foundation’s Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Program, the National Institutes of Health, and a Linda Pechenik Montague Investigator award. One study coauthor is a full-time employee of Novartis Institutes of Biomedical Research. The other authors and Dr. Wilson had no disclosures.

*Correction, 6/29/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the average age of Black participants.

, according to a study published in PLOS Genetics.

Prior studies have investigated height as a risk factor for chronic diseases, such as a higher risk for atrial fibrillation and a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease. It’s been consistently difficult, however, to eliminate the confounding influences of diet, socioeconomics, lifestyle behaviors, and other environmental factors that may interfere with a person’s reaching their expected height based on their genes.

This study, however, was able to better parse those differences by using Mendelian randomization within the comprehensive clinical and genetic dataset of a national health care system biobank. Mendelian randomization uses “genetic instruments for exposures of interest under the assumption that genotype is less susceptible to confounding than measured exposures,” the authors explained. The findings confirmed previously suspected associations between height and a range of cardiovascular and metabolic conditions as well as revealing new associations with several other conditions.

Prior associations confirmed, new associations uncovered

The results confirmed that being tall is linked to a higher risk of atrial fibrillation and varicose veins, and a lower risk of coronary heart disease, high blood pressure, and high cholesterol. The study also uncovered new associations between greater height and a higher risk of peripheral neuropathy, which is caused by damage to nerves on the extremities, as well as skin and bone infections, such as leg and foot ulcers.

The meta-analysis “identified five additional traits associated with genetically-predicted height,” wrote Sridharan Raghavan, MD, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, and colleagues. “Two were genitourinary conditions – erectile dysfunction and urinary retention – that can be associated with neuropathy, and a third was a phecode for nonspecific skin disorders that may be related to skin infections – consistent with the race/ethnicity stratified results.”

Removing potential confounders

F. Perry Wilson, MD, associate professor of medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., who was not involved in the study, said the findings were not particularly surprising overall, but it’s striking that the researchers had ”such a large cohort with such detailed electronic health records allowing for the comparison of genetic height with a variety of clinical outcomes.” He also noted the study’s strength in using Mendelian randomization so that the exposure is the predicted genetic height instead of a person’s measured height.

“This is key, since lots of things affect actual height – nutrition is an important one that could certainly be linked to disease as well,” Dr. Wilson said. ”By using genetic height, the authors remove these potential confounders. Since genetic height is “assigned” at birth (or conception), there is little opportunity for confounding. Of course, it is possible that some of the gene variants used to predict genetic height actually do something else, such as make you seek out less nutritious meals, but by and large this is how these types of studies need to be done.”

Height may impact over 100 clinical traits

The study relied on data from the U.S. Veteran Affairs Million Veteran Program with 222,300 non-Hispanic White and 58,151 non-Hispanic Black participants. The researchers first estimated the likelihood of participants’ genetic height based on 3,290 genetic variants determined to affect genetic height in a recent European-ancestry genome-wide meta-analysis. Then they compared these estimates with participants’ actual height in the VA medical record, adjusting for age, sex, and other genetic characteristics.

In doing so, the researchers found 345 clinical traits that were associated with the actual measured height in White participants plus another 17 clinical trials linked to actual measured height in Black participants. An overall 127 of these clinical traits were significantly associated with White participants’ genetically predicted height, and two of them were significantly associated with Black participants’ genetically predicted height.

In analyzing all these data together, the researchers were largely able to separate out those associations between genetically predicted height and certain health conditions from those associations between health conditions and a person’s actual measured height. They also determined that including body mass index as a covariate had little impact on the results. The researchers conducted the appropriate statistical correction to ensure the use of so many variables did not result in spurious statistical significance in some associations.

“Using genetic methods applied to the VA Million Veteran Program, we found evidence that adult height may impact over 100 clinical traits, including several conditions associated with poor outcomes and quality of life – peripheral neuropathy, lower extremity ulcers, and chronic venous insufficiency. We conclude that height may be an unrecognized nonmodifiable risk factor for several common conditions in adults.”

Height linked with health conditions

Genetically predicted height predicted a reduced risk of hyperlipidemia and hypertension independent of coronary heart disease, the analysis revealed. Genetically predicted height was also linked to an approximately 51% increased risk of atrial fibrillation in participants without coronary heart disease but, paradoxically, only a 39% increased risk in those with coronary heart disease, despite coronary heart disease being a risk factor for atrial fibrillation. Genetically predicted height was also associated with a greater risk of varicose veins in the legs and deep vein thrombosis.

Another novel association uncovered by the analysis was between women’s genetically predicted height and both asthma and nonspecific peripheral nerve disorders. “Whether these associations reflect differences by sex in disease pathophysiology related to height may warrant exploration in a sample with better balance between men and women,” the authors wrote. “In sum, our results suggest that an individual’s height may warrant consideration as a nonmodifiable predictor for several common conditions, particularly those affecting peripheral/distal extremities that are most physically impacted by tall stature.”

A substantial limitation of the study was its homogeneity of participants, who were 92% male with an average height of 176 cm and an average BMI of 30.1. The Black participants tended to be younger, with an average age of 58 compared with 64 years in the White participants, but the groups were otherwise similar in height and weight.* The database included data from Hispanic participants, but the researchers excluded these data because of the small sample size.

The smaller dataset for Black participants was a limitation as well as the fact that the genome-wide association study the researchers relied on came from a European population, which may not be as accurate in people with other ancestry, Dr. Wilson said. The bigger limitation, however, is what the findings’ clinical relevance is.

What does it all mean?

“Genetic height is in your genes – there is nothing to be done about it – so it is more of academic interest than clinical interest,” Dr. Wilson said. It’s not even clear whether incorporating a person’s height – actual or genetically predicted, if it could be easily determined for each person – into risk calculators. ”To know whether it would be beneficial to use height (or genetic height) as a risk factor, you’d need to examine each condition of interest, adjusting for all known risk factors, to see if height improved the prediction,” Dr. Wilson said. “I suspect for most conditions, the well-known risk factors would swamp height. For example, high genetic height might truly increase risk for neuropathy. But diabetes might increase the risk so much more that height is not particularly relevant.”

On the other hand, the fact that height in general has any potential influence at all on disease risk may inspire physicians to consider other risk factors in especially tall individuals.

”Physicians may find it interesting that we have some confirmation that height does increase the risk of certain conditions,” Dr. Wilson said. “While this is unlikely to dramatically change practice, they may be a bit more diligent in looking for other relevant risk factors for the diseases found in this study in their very tall patients.”

The research was funded by the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, the Boettcher Foundation’s Webb-Waring Biomedical Research Program, the National Institutes of Health, and a Linda Pechenik Montague Investigator award. One study coauthor is a full-time employee of Novartis Institutes of Biomedical Research. The other authors and Dr. Wilson had no disclosures.

*Correction, 6/29/22: An earlier version of this article misstated the average age of Black participants.

FROM PLOS GENETICS

CTO PCI success rates rising, with blip during COVID-19, registry shows

Technical and procedural success rates for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention (CTO PCI) have increased steadily over the past 6 years, with rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE) declining to the 2%-or-lower range in that time.

“CTO PCI technical and procedural success rates are high and continue to increase over time,” Spyridon Kostantinis, MD said in presenting updated results from the international PROGRESS-CTO registry at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions annual scientific sessions.

“The overall success rate increased from 81.6% in 2018 to 88.1% in 2021,” he added. The overall incidence of in-hospital MACE in that time was “an acceptable” 2.1% without significant changes over that period.

The analysis examined clinical, angiographic and procedural outcomes of 10,249 CTO PCIs performed on 10,019 patients from 63 centers in nine countries during 2016-2021. PROGRESS-CTO stands for Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention.

The target CTOs were highly complex, he said, with an average J-CTO (multicenter CTO registry in Japan) score of 2.4 ± 1.3 and PROGRESS-CTO score of 1.3 ± 1. The most common CTO target vessel was the right coronary artery (53%), followed by the left anterior descending artery (26%) and the circumflex artery (19%).

The registry also tracked how characteristics of the CTO PCI procedures themselves changed over time. “The septal and the epicardial collaterals were the most common collaterals used for retrograde crossing, with a decreasing trend for epicardial collaterals over time,” said Dr. Kostantinis, a research fellow at the Minneapolis Heart Institute.

Septal collateral use varied between 64% and 69% of cases from 2016 to 2021, but the share of epicardial collaterals declined from 35% to 22% in that time.

“Over time, the range of antegrade wiring as the final successfully crossing strategy increased from 46% in 2016 to 61% in 2021, with a decrease in antegrade dissection and re-entry (ADR) and no change in the retrograde approach,” Dr. Kostantinis said. The percentage of procedures using ADR as the final crossing strategy declined from 18% in 2016 to 12% in 2021, with the rate of retrograde crossings peaking at 21% in 2016 but leveling off to 18% or 19% in the subsequent years.

“An increasing use in the efficiency of antegrade wiring may reflect an improvement in guidewire retrograde crossing as well as the increasing operator expertise,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

The study also found that contrast volume, air kerma radiation dose, fluoroscopy time, and procedure time declined steadily over time. “The potential explanations for these are using new x-ray systems as well as the use of intravascular imaging,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

In 2020, the rates of technical and procedural success, as well as the number of overall procedures, declined from 2019, while MACE rates ticked upward that year, probably because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Kostantinis said.

“It is true that we noticed a rise in MACE rate from 1.6% in 2019 to 2.7% in 2020, but in 2021 that decreased again to 1.7%,” he said in an interview. “Another potential explanation is the higher angiographic complexity of CTOs treated during that year (2020) that resulted in more adverse events.”

Previous results from the PROGRESS-CTO registry reported the difference in MACE between 2019 and 2020 was significant (P = .01). “So, yes, the difference between those 2 years is significant,” Dr. Kostantinis said. However, he noted, the overall trend was not significant, with a P value of .194.

The risk profile of CTO PCI has improved “slowly” over time, said Kirk N. Garratt, MD, but “it’s not yet were it needs to be.”

He added, “Undoubtedly we’ve learned that, without any question, one method for minimizing the risk is to concentrate these cases in the hands of those that do many of them.” As the number of procedures fell – an “embedded” pandemic impact –“I worry that it’s inevitable that complication rates will tick up a bit,” said Dr. Garratt, director of the Center for Heart and Vascular Health at Christiana Care in Newark, Del.

By the same token, he added, this situation with regard to CTOs “parallels what’s happening elsewhere in interventional medicine and medicine broadly; numbers are increasing and we’re busy again. In most domains we’re not as busy as we had been prepandemic, and time will allow us to catch up.”

PROGRESS-CTO has received funding from the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Foundation and the Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation Innovation Grant.

Dr. Kostantinis has no disclosures. Dr. Garratt is an advisory board member for Abbott.

Technical and procedural success rates for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention (CTO PCI) have increased steadily over the past 6 years, with rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE) declining to the 2%-or-lower range in that time.

“CTO PCI technical and procedural success rates are high and continue to increase over time,” Spyridon Kostantinis, MD said in presenting updated results from the international PROGRESS-CTO registry at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions annual scientific sessions.

“The overall success rate increased from 81.6% in 2018 to 88.1% in 2021,” he added. The overall incidence of in-hospital MACE in that time was “an acceptable” 2.1% without significant changes over that period.

The analysis examined clinical, angiographic and procedural outcomes of 10,249 CTO PCIs performed on 10,019 patients from 63 centers in nine countries during 2016-2021. PROGRESS-CTO stands for Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention.

The target CTOs were highly complex, he said, with an average J-CTO (multicenter CTO registry in Japan) score of 2.4 ± 1.3 and PROGRESS-CTO score of 1.3 ± 1. The most common CTO target vessel was the right coronary artery (53%), followed by the left anterior descending artery (26%) and the circumflex artery (19%).

The registry also tracked how characteristics of the CTO PCI procedures themselves changed over time. “The septal and the epicardial collaterals were the most common collaterals used for retrograde crossing, with a decreasing trend for epicardial collaterals over time,” said Dr. Kostantinis, a research fellow at the Minneapolis Heart Institute.

Septal collateral use varied between 64% and 69% of cases from 2016 to 2021, but the share of epicardial collaterals declined from 35% to 22% in that time.

“Over time, the range of antegrade wiring as the final successfully crossing strategy increased from 46% in 2016 to 61% in 2021, with a decrease in antegrade dissection and re-entry (ADR) and no change in the retrograde approach,” Dr. Kostantinis said. The percentage of procedures using ADR as the final crossing strategy declined from 18% in 2016 to 12% in 2021, with the rate of retrograde crossings peaking at 21% in 2016 but leveling off to 18% or 19% in the subsequent years.

“An increasing use in the efficiency of antegrade wiring may reflect an improvement in guidewire retrograde crossing as well as the increasing operator expertise,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

The study also found that contrast volume, air kerma radiation dose, fluoroscopy time, and procedure time declined steadily over time. “The potential explanations for these are using new x-ray systems as well as the use of intravascular imaging,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

In 2020, the rates of technical and procedural success, as well as the number of overall procedures, declined from 2019, while MACE rates ticked upward that year, probably because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Kostantinis said.

“It is true that we noticed a rise in MACE rate from 1.6% in 2019 to 2.7% in 2020, but in 2021 that decreased again to 1.7%,” he said in an interview. “Another potential explanation is the higher angiographic complexity of CTOs treated during that year (2020) that resulted in more adverse events.”

Previous results from the PROGRESS-CTO registry reported the difference in MACE between 2019 and 2020 was significant (P = .01). “So, yes, the difference between those 2 years is significant,” Dr. Kostantinis said. However, he noted, the overall trend was not significant, with a P value of .194.

The risk profile of CTO PCI has improved “slowly” over time, said Kirk N. Garratt, MD, but “it’s not yet were it needs to be.”

He added, “Undoubtedly we’ve learned that, without any question, one method for minimizing the risk is to concentrate these cases in the hands of those that do many of them.” As the number of procedures fell – an “embedded” pandemic impact –“I worry that it’s inevitable that complication rates will tick up a bit,” said Dr. Garratt, director of the Center for Heart and Vascular Health at Christiana Care in Newark, Del.

By the same token, he added, this situation with regard to CTOs “parallels what’s happening elsewhere in interventional medicine and medicine broadly; numbers are increasing and we’re busy again. In most domains we’re not as busy as we had been prepandemic, and time will allow us to catch up.”

PROGRESS-CTO has received funding from the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Foundation and the Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation Innovation Grant.

Dr. Kostantinis has no disclosures. Dr. Garratt is an advisory board member for Abbott.

Technical and procedural success rates for chronic total occlusion percutaneous coronary intervention (CTO PCI) have increased steadily over the past 6 years, with rates of in-hospital major adverse cardiac events (MACE) declining to the 2%-or-lower range in that time.

“CTO PCI technical and procedural success rates are high and continue to increase over time,” Spyridon Kostantinis, MD said in presenting updated results from the international PROGRESS-CTO registry at the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography & Interventions annual scientific sessions.

“The overall success rate increased from 81.6% in 2018 to 88.1% in 2021,” he added. The overall incidence of in-hospital MACE in that time was “an acceptable” 2.1% without significant changes over that period.

The analysis examined clinical, angiographic and procedural outcomes of 10,249 CTO PCIs performed on 10,019 patients from 63 centers in nine countries during 2016-2021. PROGRESS-CTO stands for Prospective Global Registry for the Study of Chronic Total Occlusion Intervention.

The target CTOs were highly complex, he said, with an average J-CTO (multicenter CTO registry in Japan) score of 2.4 ± 1.3 and PROGRESS-CTO score of 1.3 ± 1. The most common CTO target vessel was the right coronary artery (53%), followed by the left anterior descending artery (26%) and the circumflex artery (19%).

The registry also tracked how characteristics of the CTO PCI procedures themselves changed over time. “The septal and the epicardial collaterals were the most common collaterals used for retrograde crossing, with a decreasing trend for epicardial collaterals over time,” said Dr. Kostantinis, a research fellow at the Minneapolis Heart Institute.

Septal collateral use varied between 64% and 69% of cases from 2016 to 2021, but the share of epicardial collaterals declined from 35% to 22% in that time.

“Over time, the range of antegrade wiring as the final successfully crossing strategy increased from 46% in 2016 to 61% in 2021, with a decrease in antegrade dissection and re-entry (ADR) and no change in the retrograde approach,” Dr. Kostantinis said. The percentage of procedures using ADR as the final crossing strategy declined from 18% in 2016 to 12% in 2021, with the rate of retrograde crossings peaking at 21% in 2016 but leveling off to 18% or 19% in the subsequent years.

“An increasing use in the efficiency of antegrade wiring may reflect an improvement in guidewire retrograde crossing as well as the increasing operator expertise,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

The study also found that contrast volume, air kerma radiation dose, fluoroscopy time, and procedure time declined steadily over time. “The potential explanations for these are using new x-ray systems as well as the use of intravascular imaging,” Dr. Kostantinis said.

In 2020, the rates of technical and procedural success, as well as the number of overall procedures, declined from 2019, while MACE rates ticked upward that year, probably because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. Kostantinis said.

“It is true that we noticed a rise in MACE rate from 1.6% in 2019 to 2.7% in 2020, but in 2021 that decreased again to 1.7%,” he said in an interview. “Another potential explanation is the higher angiographic complexity of CTOs treated during that year (2020) that resulted in more adverse events.”

Previous results from the PROGRESS-CTO registry reported the difference in MACE between 2019 and 2020 was significant (P = .01). “So, yes, the difference between those 2 years is significant,” Dr. Kostantinis said. However, he noted, the overall trend was not significant, with a P value of .194.

The risk profile of CTO PCI has improved “slowly” over time, said Kirk N. Garratt, MD, but “it’s not yet were it needs to be.”

He added, “Undoubtedly we’ve learned that, without any question, one method for minimizing the risk is to concentrate these cases in the hands of those that do many of them.” As the number of procedures fell – an “embedded” pandemic impact –“I worry that it’s inevitable that complication rates will tick up a bit,” said Dr. Garratt, director of the Center for Heart and Vascular Health at Christiana Care in Newark, Del.

By the same token, he added, this situation with regard to CTOs “parallels what’s happening elsewhere in interventional medicine and medicine broadly; numbers are increasing and we’re busy again. In most domains we’re not as busy as we had been prepandemic, and time will allow us to catch up.”

PROGRESS-CTO has received funding from the Joseph F. and Mary M. Fleischhacker Foundation and the Abbott Northwestern Hospital Foundation Innovation Grant.

Dr. Kostantinis has no disclosures. Dr. Garratt is an advisory board member for Abbott.

FROM SCAI 2022

‘Sit less, move more’ to reduce stroke risk

in a population-based study of middle aged and older adults.

The study also found relatively short periods of moderate to vigorous exercise were associated with reduced stroke risk.

“Our results suggest there are a number of ways to reduce stroke risk simply by moving about,” said lead author Steven P. Hooker, PhD, San Diego State University. “This could be with short periods of moderate to vigorous activity each day, longer periods of light activity, or just sedentary for shorter periods of time. All these things can make a difference.”

Dr. Hooker explained that, while it has been found previously that moderate to vigorous exercise reduces stroke risk, this study gives more information on light-intensity activities and sedentary behavior and the risk of stroke.

“Our results suggest that you don’t have to be a chronic exerciser to reduce stroke risk. Replacing sedentary time with light-intensity activity will be beneficial. Just go for a short walk, get up from your desk and move around the house at regular intervals. That can help to reduce stroke risk,” Dr. Hooker said.

“Our message is basically to sit less and move more,” he added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study involved 7,607 U.S. individuals without a history of stroke, with oversampling from the southeastern “Stroke Belt,” who were participating in the REGARDS cohort study.

The participants wore an accelerometer to measure physical activity and sedentary behavior for 7 consecutive days. The mean age of the individuals was 63 years; 54% were female, 32% were Black.

Over a mean follow-up of 7.4 years, 286 incident stroke cases occurred.

Results showed that increased levels of physical activity were associated with reduced risk of stroke.

For moderate to vigorous activity, compared with participants in the lowest tertile, those in the highest tertile of total daily time in moderate to vigorous activity had a 43% lower risk of stroke.

In the current study, the amount of moderate to vigorous activity associated with a significant reduction in stroke risk was approximately 25 minutes per day (3 hours per week).

Dr. Hooker noted that moderate to vigorous activity included things such as brisk walking, jogging, bike riding, swimming, or playing tennis or soccer. “Doing such activities for just 25 minutes per day reduced risk of stroke by 43%. This is very doable. Just commuting to work by bicycle would cover you here,” he said.

In terms of light-intensity activity, individuals who did 4-5 hours of light activities each day had a 26% reduced risk for first stroke, compared with those doing less than 3 hours of such light activities.

Dr. Hooker explained that examples of light activity included household chores, such as vacuuming, washing dishes, or going for a gentle stroll. “These activities do not require heaving breathing, increased heart rate or breaking into a sweat. They are activities of daily living and relatively easy to engage in.”

But he pointed out that the 4-5 hours of light activity every day linked to a reduction in stroke risk may be more difficult to achieve than the 25 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity, saying: “You have to have some intentionality here.”

Long bouts of sedentary time are harmful

The study also showed that sedentary time was associated with a higher risk for stroke.

The authors noted that time spent in sedentary behavior is of interest because most adults spend most of their awake time being physically inactive.

They report that participants in the highest tertile of sedentary time (more than 13 hours/day) exhibited a 44% increase in risk of stroke, compared with those in the lowest tertile (less than 11 hours/day), and the association remained significant when adjusted for several covariates, including moderate to vigorous activity.

“Even when controlling for the amount of other physical activity, sedentary behavior is still highly associated with risk of stroke. So even if you are active, long bouts of sedentary behavior are harmful,” Dr. Hooker commented.

They also found that longer bouts of sedentary time (more than 17 minutes at a time) were associated with a 54% higher risk of stroke than shorter bouts (less than 8 minutes).

“This suggests that breaking up periods of sedentary behavior into shorter bouts would be beneficial,” Dr. Hooker said.

“If you are going to spend the evening on the couch watching television, try to stand up and walk around every few minutes. Same for if you are sitting at a computer all day – try having a standing workstation, or at least take regular breaks to walk around,” he added.

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute on Aging. Additional funding was provided by an unrestricted grant from the Coca-Cola Company. The authors report no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in a population-based study of middle aged and older adults.

The study also found relatively short periods of moderate to vigorous exercise were associated with reduced stroke risk.

“Our results suggest there are a number of ways to reduce stroke risk simply by moving about,” said lead author Steven P. Hooker, PhD, San Diego State University. “This could be with short periods of moderate to vigorous activity each day, longer periods of light activity, or just sedentary for shorter periods of time. All these things can make a difference.”

Dr. Hooker explained that, while it has been found previously that moderate to vigorous exercise reduces stroke risk, this study gives more information on light-intensity activities and sedentary behavior and the risk of stroke.

“Our results suggest that you don’t have to be a chronic exerciser to reduce stroke risk. Replacing sedentary time with light-intensity activity will be beneficial. Just go for a short walk, get up from your desk and move around the house at regular intervals. That can help to reduce stroke risk,” Dr. Hooker said.

“Our message is basically to sit less and move more,” he added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study involved 7,607 U.S. individuals without a history of stroke, with oversampling from the southeastern “Stroke Belt,” who were participating in the REGARDS cohort study.

The participants wore an accelerometer to measure physical activity and sedentary behavior for 7 consecutive days. The mean age of the individuals was 63 years; 54% were female, 32% were Black.

Over a mean follow-up of 7.4 years, 286 incident stroke cases occurred.

Results showed that increased levels of physical activity were associated with reduced risk of stroke.

For moderate to vigorous activity, compared with participants in the lowest tertile, those in the highest tertile of total daily time in moderate to vigorous activity had a 43% lower risk of stroke.

In the current study, the amount of moderate to vigorous activity associated with a significant reduction in stroke risk was approximately 25 minutes per day (3 hours per week).

Dr. Hooker noted that moderate to vigorous activity included things such as brisk walking, jogging, bike riding, swimming, or playing tennis or soccer. “Doing such activities for just 25 minutes per day reduced risk of stroke by 43%. This is very doable. Just commuting to work by bicycle would cover you here,” he said.

In terms of light-intensity activity, individuals who did 4-5 hours of light activities each day had a 26% reduced risk for first stroke, compared with those doing less than 3 hours of such light activities.

Dr. Hooker explained that examples of light activity included household chores, such as vacuuming, washing dishes, or going for a gentle stroll. “These activities do not require heaving breathing, increased heart rate or breaking into a sweat. They are activities of daily living and relatively easy to engage in.”

But he pointed out that the 4-5 hours of light activity every day linked to a reduction in stroke risk may be more difficult to achieve than the 25 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity, saying: “You have to have some intentionality here.”

Long bouts of sedentary time are harmful

The study also showed that sedentary time was associated with a higher risk for stroke.

The authors noted that time spent in sedentary behavior is of interest because most adults spend most of their awake time being physically inactive.

They report that participants in the highest tertile of sedentary time (more than 13 hours/day) exhibited a 44% increase in risk of stroke, compared with those in the lowest tertile (less than 11 hours/day), and the association remained significant when adjusted for several covariates, including moderate to vigorous activity.

“Even when controlling for the amount of other physical activity, sedentary behavior is still highly associated with risk of stroke. So even if you are active, long bouts of sedentary behavior are harmful,” Dr. Hooker commented.

They also found that longer bouts of sedentary time (more than 17 minutes at a time) were associated with a 54% higher risk of stroke than shorter bouts (less than 8 minutes).

“This suggests that breaking up periods of sedentary behavior into shorter bouts would be beneficial,” Dr. Hooker said.

“If you are going to spend the evening on the couch watching television, try to stand up and walk around every few minutes. Same for if you are sitting at a computer all day – try having a standing workstation, or at least take regular breaks to walk around,” he added.

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute on Aging. Additional funding was provided by an unrestricted grant from the Coca-Cola Company. The authors report no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

in a population-based study of middle aged and older adults.

The study also found relatively short periods of moderate to vigorous exercise were associated with reduced stroke risk.

“Our results suggest there are a number of ways to reduce stroke risk simply by moving about,” said lead author Steven P. Hooker, PhD, San Diego State University. “This could be with short periods of moderate to vigorous activity each day, longer periods of light activity, or just sedentary for shorter periods of time. All these things can make a difference.”

Dr. Hooker explained that, while it has been found previously that moderate to vigorous exercise reduces stroke risk, this study gives more information on light-intensity activities and sedentary behavior and the risk of stroke.

“Our results suggest that you don’t have to be a chronic exerciser to reduce stroke risk. Replacing sedentary time with light-intensity activity will be beneficial. Just go for a short walk, get up from your desk and move around the house at regular intervals. That can help to reduce stroke risk,” Dr. Hooker said.

“Our message is basically to sit less and move more,” he added.

The study was published online in JAMA Network Open.

The study involved 7,607 U.S. individuals without a history of stroke, with oversampling from the southeastern “Stroke Belt,” who were participating in the REGARDS cohort study.

The participants wore an accelerometer to measure physical activity and sedentary behavior for 7 consecutive days. The mean age of the individuals was 63 years; 54% were female, 32% were Black.

Over a mean follow-up of 7.4 years, 286 incident stroke cases occurred.

Results showed that increased levels of physical activity were associated with reduced risk of stroke.

For moderate to vigorous activity, compared with participants in the lowest tertile, those in the highest tertile of total daily time in moderate to vigorous activity had a 43% lower risk of stroke.

In the current study, the amount of moderate to vigorous activity associated with a significant reduction in stroke risk was approximately 25 minutes per day (3 hours per week).

Dr. Hooker noted that moderate to vigorous activity included things such as brisk walking, jogging, bike riding, swimming, or playing tennis or soccer. “Doing such activities for just 25 minutes per day reduced risk of stroke by 43%. This is very doable. Just commuting to work by bicycle would cover you here,” he said.

In terms of light-intensity activity, individuals who did 4-5 hours of light activities each day had a 26% reduced risk for first stroke, compared with those doing less than 3 hours of such light activities.

Dr. Hooker explained that examples of light activity included household chores, such as vacuuming, washing dishes, or going for a gentle stroll. “These activities do not require heaving breathing, increased heart rate or breaking into a sweat. They are activities of daily living and relatively easy to engage in.”

But he pointed out that the 4-5 hours of light activity every day linked to a reduction in stroke risk may be more difficult to achieve than the 25 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity, saying: “You have to have some intentionality here.”

Long bouts of sedentary time are harmful

The study also showed that sedentary time was associated with a higher risk for stroke.

The authors noted that time spent in sedentary behavior is of interest because most adults spend most of their awake time being physically inactive.

They report that participants in the highest tertile of sedentary time (more than 13 hours/day) exhibited a 44% increase in risk of stroke, compared with those in the lowest tertile (less than 11 hours/day), and the association remained significant when adjusted for several covariates, including moderate to vigorous activity.

“Even when controlling for the amount of other physical activity, sedentary behavior is still highly associated with risk of stroke. So even if you are active, long bouts of sedentary behavior are harmful,” Dr. Hooker commented.

They also found that longer bouts of sedentary time (more than 17 minutes at a time) were associated with a 54% higher risk of stroke than shorter bouts (less than 8 minutes).

“This suggests that breaking up periods of sedentary behavior into shorter bouts would be beneficial,” Dr. Hooker said.

“If you are going to spend the evening on the couch watching television, try to stand up and walk around every few minutes. Same for if you are sitting at a computer all day – try having a standing workstation, or at least take regular breaks to walk around,” he added.

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and the National Institute on Aging. Additional funding was provided by an unrestricted grant from the Coca-Cola Company. The authors report no disclosures.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

Antipsychotic tied to dose-related weight gain, higher cholesterol

new research suggests.

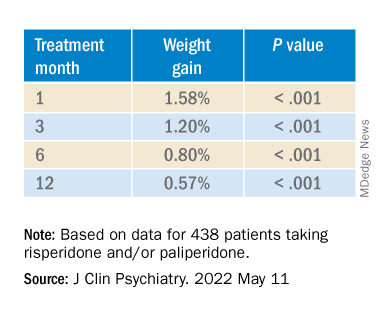

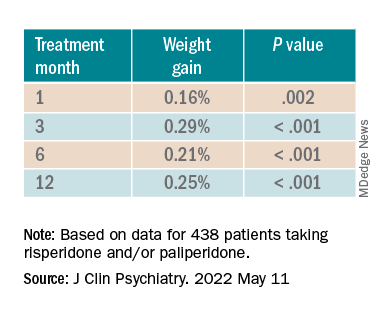

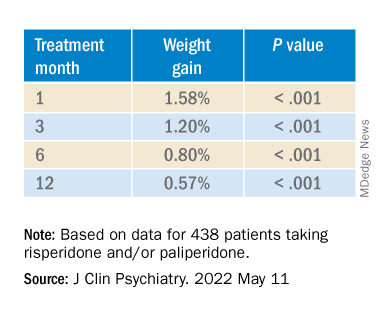

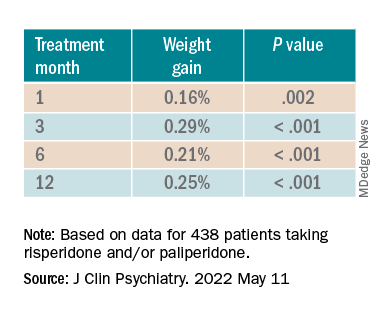

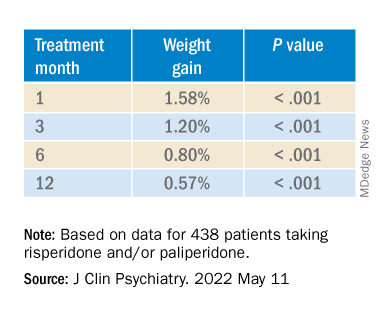

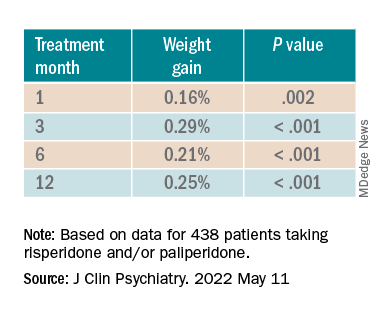

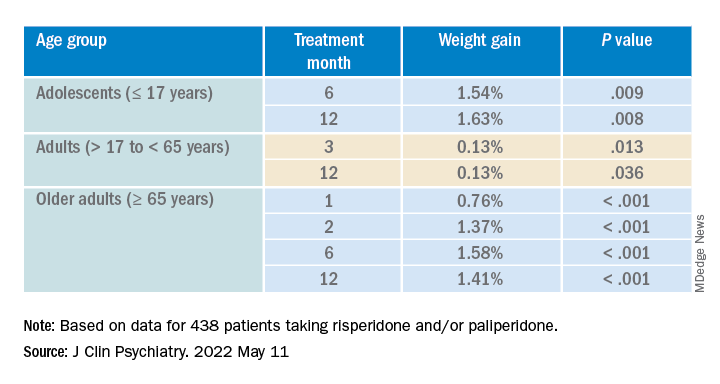

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

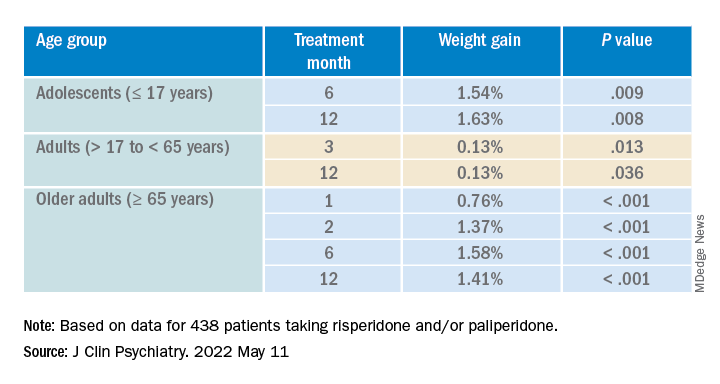

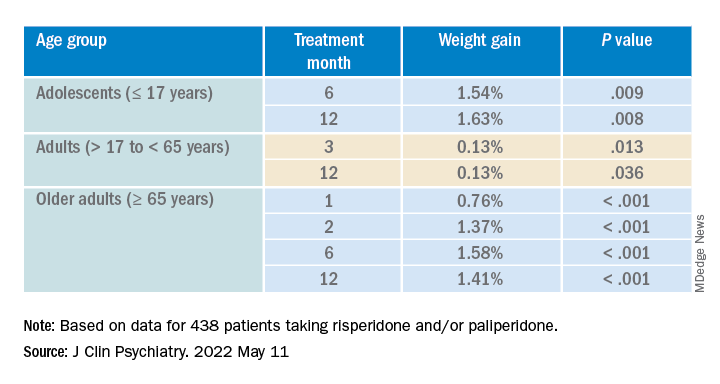

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”

It “leverages real-world data from a large patient registry to ask a long-unanswered question: Are weight and metabolic adverse effects proportional to dose? Big data approaches like these are very powerful, given the large number of participants that can be included,” said Dr. Nurmi, who was not involved with the research.

However, she cautioned, the “biggest drawback [is that] these data are by nature much more complex and prone to confounding effects.”

In this case, a “critical confounder” for the study was that the majority of individuals taking higher risperidone doses were also taking other drugs known to cause weight gain, whereas the majority of those on lower risperidone doses were not. “This difference may explain the dose relationship observed,” she said.

Because real-world, big data are “valuable but also messy, conclusions drawn from them must be interpreted with caution,” Dr. Nurmi said.

She added that it is generally wise to use the lowest effective dose possible.

“Clinicians should appreciate that even small doses of antipsychotics can cause big changes in weight. Risks and benefits of medications must be carefully considered in clinical practice,” Dr. Nurmi said.

The research was funded in part by the Swiss National Research Foundation. Piras reports no relevant financial relationships. The other investigators’ disclosures are listed in the original article. Dr. Nurmi reported no relevant financial relationships, but she is an unpaid member of the Tourette Association of America’s medical advisory board and of the Myriad Genetics scientific advisory board.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Investigators analyzed 1-year data for more than 400 patients who were taking risperidone and/or its metabolite paliperidone (Invega). Results showed increments of 1 mg of risperidone-equivalent doses were associated with an increase of 0.25% of weight within a year of follow-up.

“Although our findings report a positive and statistically significant dose-dependence of weight gain and cholesterol, both total and LDL [cholesterol], the size of the predicted changes of metabolic effects is clinically nonrelevant,” lead author Marianna Piras, PharmD, Centre for Psychiatric Neuroscience, Lausanne (Switzerland) University Hospital, said in an interview.

“Therefore, dose lowering would not have a beneficial effect on attenuating weight gain or cholesterol increases and could lead to psychiatric decompensation,” said Ms. Piras, who is also a PhD candidate in the unit of pharmacogenetics and clinical psychopharmacology at the University of Lausanne.

However, she added that because dose increments could increase risk for significant weight gain in the first month of treatment – the dose can be increased typically in a range of 1-10 grams – and strong dose increments could contribute to metabolic worsening over time, “risperidone minimum effective doses should be preferred.”

The findings were published online in the Journal of Clinical Psychiatry.

‘Serious public health issue’

Compared with the general population, patients with mental illness present with a greater prevalence of metabolic disorders. In addition, several psychotropic medications, including antipsychotics, can induce metabolic alterations such as weight gain, the investigators noted.

Antipsychotic-induced metabolic adverse effects “constitute a serious public health issue” because they are risk factors for cardiovascular diseases such as obesity and/or dyslipidemia, “which have been associated with a 10-year reduced life expectancy in the psychiatric population,” Ms. Piras said.

“The dose-dependence of metabolic adverse effects is a debated subject that needs to be assessed for each psychotropic drug known to induce weight gain,” she added.

Several previous studies have examined whether there is a dose-related effect of antipsychotics on metabolic parameters, “with some results suggesting that [weight gain] seems to develop even when low off-label doses are prescribed,” Ms. Piras noted.

She and her colleagues had already studied dose-related metabolic effects of quetiapine (Seroquel) and olanzapine (Zyprexa).

Risperidone is an antipsychotic with a “medium to high metabolic risk profile,” the researchers note, and few studies have examined the impact of risperidone on metabolic parameters other than weight gain.

For the current analysis, they analyzed data from a longitudinal study that included 438 patients (mean age, 40.7 years; 50.7% men) who started treatment with risperidone and/or paliperidone between 2007 and 2018.

The participants had diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, bipolar disorder, depression, “other,” or “unknown.”

Clinical follow-up periods were up to a year, but were no shorter than 3 weeks. The investigators also assessed the data at different time intervals at 1, 3, 6, and 12 months “to appreciate the evolution of the metabolic parameters.”

In addition, they collected demographic and clinical information, such as comorbidities, and measured patients’ weight, height, waist circumference, blood pressure, plasma glucose, and lipids at baseline and at 1, 3, and 12 months and then annually. Weight, waist circumference, and BP were also assessed at 2 and 6 months.

Doses of paliperidone were converted into risperidone-equivalent doses.

Significant weight gain over time

The mean duration of follow-up for the participants, of whom 374 were being treated with risperidone and 64 with paliperidone, was 153 days. Close to half (48.2%) were taking other psychotropic medications known to be associated with some degree of metabolic risk.

Patients were divided into two cohorts based on their daily dose intake (DDI): less than 3 mg/day (n = 201) and at least 3 mg/day (n = 237).

In the overall cohort, a “significant effect of time on weight change was found for each time point,” the investigators reported.

When the researchers looked at the changes according to DDI, they found that each 1-mg dose increase was associated with incremental weight gain at each time point.

Patients who had 5% or greater weight gain in the first month continued to gain weight more than patients who did not reach that threshold, leading the researchers to call that early threshold a “strong predictor of important weight gain in the long term.” There was a weight gain of 6.68% at 3 months, of 7.36% at 6 months, and of 7.7% at 12 months.

After the patients were stratified by age, there were differences in the effect of DDI on various age groups at different time points.

Dose was shown to have a significant effect on weight gain for women at all four time points (P ≥ .001), but for men only at 3 months (P = .003).

For each additional 1-mg dose, there was a 0.05 mmol/L (1.93 mg/dL) increase in total cholesterol (P = .018) after 1 year and a 0.04 mmol/L (1.54 mg/dL) increase in LDL cholesterol (P = .011).

There were no significant effects of time or DDI on triglycerides, HDL cholesterol, glucose levels, and systolic BP, and there was a negative effect of DDI on diastolic BP (P = .001).

The findings “provide evidence for a small dose effect of risperidone” on weight gain and total and LDL cholesterol levels, the investigators note.

Ms. Piras added that because each antipsychotic differs in its metabolic risk profile, “further analyses on other antipsychotics are ongoing in our laboratory, so far confirming our findings.”

Small increases, big changes

Commenting on the study, Erika Nurmi, MD, PhD, associate professor in the department of psychiatry and biobehavioral sciences at the Semel Institute for Neuroscience, University of California, Los Angeles, said the study is “unique in the field.”