User login

Novel cardiac troponin protocol rapidly rules out MI

PARIS – An accelerated rule-out pathway, reliant upon a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin test upon presentation to the ED with suspected acute coronary syndrome, reduced length of stay and hospital admission rates without increasing cardiac events at 30 days or 1 year in a major Scottish study.

“We conclude that implementation of this early rule-out pathway is both effective and safe, and adoption of this pathway will have major benefits for patients and health care systems,” Nicholas L. Mills, MBChB, PhD, said in presenting the results of the HiSTORIC (High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin at Presentation to Rule Out Myocardial Infarction) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, in the Unites States, where more than 20 million people per year present to EDs with suspected ACS, the 3.3-hour reduction in length of stay achieved in the HiSTORIC trial by implementing the accelerated rule-out pathway would add up to a $3.6 billion annual savings in bed occupancy alone, according to Dr. Mills, who is chair of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The HiSTORIC pathway incorporates separate thresholds for risk stratification and diagnosis. This strategy is based on an accumulation of persuasive evidence that the major advantage of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing is to rule out MI, rather than to rule it in, Dr. Mills explained.

HiSTORIC was a 2-year, prospective, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, controlled trial including 31,492 consecutive patients with suspected ACS who presented to seven participating hospitals in Scotland. Patients were randomized, at the hospital level, to one of two management pathways. The control group got a standard guideline-recommended strategy involving high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I testing upon presentation and again 6-12 hours later, with MI being ruled out if the troponin levels were not above the 99th percentile.

In contrast, the novel early rule-out strategy worked as follows: If the patient presented with at least 2 hours of symptoms and the initial troponin I level was below 5 ng/L, then MI was ruled out and the patient was triaged straightaway for outpatient management. If the level was above the 99th percentile, the patient was admitted for serial testing to be done 6-12 hours after symptom onset. And for an intermediate test result – that is, a troponin level between 5 ng/L and the 99th percentile – patients remained in the ED for retesting 3 hours from the time of presentation, and were subsequently admitted only if their troponin level was rising.

Using the accelerated rule-out strategy, two-thirds of patients were quickly discharged from the ED on the basis of a troponin level below 5 ng/mL, and another 7% were ruled out for MI and discharged from the ED after a 3-hour stay on the basis of their second test.

The primary efficacy outcome was length of stay from initial presentation to the ED to discharge. The duration was 10.1 hours with the guideline-recommended pathway and 6.8 hours with the accelerated rule-out pathway, for a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 3.3-hour difference. Moreover, the proportion of patients discharged directly from the ED without hospital admission increased from 53% to 74%, a 57% jump.

The primary safety outcome was the rate of MI or cardiac death post discharge. The rates at 30 days and 1 year were 0.4% and 2.6%, respectively, in the standard-pathway group, compared with 0.3% and 1.8% with the early rule-out pathway. Those between-group differences favoring the accelerated rule-out pathway weren’t statistically significant, but they provided reassurance that the novel pathway was safe.

Of note, this was the first-ever randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an early rule-out pathway. Other rapid diagnostic pathways are largely based on observational experience and expert opinion, Dr. Mills said.

The assay utilized in the HiSTORIC trial was the Abbott Diagnostics Architect high sensitivity assay. The 5-ng/L threshold for early rule-out was chosen for the trial because an earlier study by Dr. Mills and coinvestigators showed that a level below that cutoff had a 99.6% negative predictive value for MI (Lancet. 2015 Dec 19;386[10012]:2481-8)

The early rule-out pathway was deliberately designed to be simple and pragmatic, according to the cardiologist. “One of the most remarkable observations in this trial was the adherence to the pathway. We prespecified three criteria to evaluate this and demonstrated adherence rates of 86%-92% for each of these criteria. This was despite the pathway being implemented in all consecutive patients at seven different hospitals and used by many hundreds of different clinicians.”

Discussant Hugo A. Katus, MD, called the HiSTORIC study “a really urgently needed and very well-conducted trial.”

“There were very consistently low MI and cardiac death rates at 30 days and 1 year. So this really works,” commented Dr. Katus, who is chief of internal medicine and director of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Heidelberg (Germany) University.

“Accelerated rule-out high-sensitivity cardiac troponin protocols are here to stay,” he declared.

However, Dr. Katus voiced a concern: “By early discharge as rule out, are other life-threatening conditions ignored?”

He raised this issue because of what he views as the substantial 1-year all-cause mortality and return-to-hospital rates of 5.8% and 39.2% in the standard-pathway group and 5.2% and 38.9% in the accelerated rule-out patients in HiSTORIC. An accelerated rule-out strategy should not prohibit a careful clinical work-up, he emphasized.

Dr. Mills discussed the results in a video interview.

The HiSTORIC trial was funded by the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Mills reported receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics and Siemens.

Simultaneous with Dr. Mills’ presentation of the HiSTORIC trial results at the ESC congress, an earlier study that formed the scientific basis for the investigators’ decision to employ distinct risk stratification and diagnostic thresholds for cardiac troponin testing was published online (Circulation. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042866). The actual HiSTORIC trial results will be published later.

Dr. Katus reported holding a patent for a cardiac troponin T test and serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk.

PARIS – An accelerated rule-out pathway, reliant upon a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin test upon presentation to the ED with suspected acute coronary syndrome, reduced length of stay and hospital admission rates without increasing cardiac events at 30 days or 1 year in a major Scottish study.

“We conclude that implementation of this early rule-out pathway is both effective and safe, and adoption of this pathway will have major benefits for patients and health care systems,” Nicholas L. Mills, MBChB, PhD, said in presenting the results of the HiSTORIC (High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin at Presentation to Rule Out Myocardial Infarction) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, in the Unites States, where more than 20 million people per year present to EDs with suspected ACS, the 3.3-hour reduction in length of stay achieved in the HiSTORIC trial by implementing the accelerated rule-out pathway would add up to a $3.6 billion annual savings in bed occupancy alone, according to Dr. Mills, who is chair of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The HiSTORIC pathway incorporates separate thresholds for risk stratification and diagnosis. This strategy is based on an accumulation of persuasive evidence that the major advantage of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing is to rule out MI, rather than to rule it in, Dr. Mills explained.

HiSTORIC was a 2-year, prospective, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, controlled trial including 31,492 consecutive patients with suspected ACS who presented to seven participating hospitals in Scotland. Patients were randomized, at the hospital level, to one of two management pathways. The control group got a standard guideline-recommended strategy involving high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I testing upon presentation and again 6-12 hours later, with MI being ruled out if the troponin levels were not above the 99th percentile.

In contrast, the novel early rule-out strategy worked as follows: If the patient presented with at least 2 hours of symptoms and the initial troponin I level was below 5 ng/L, then MI was ruled out and the patient was triaged straightaway for outpatient management. If the level was above the 99th percentile, the patient was admitted for serial testing to be done 6-12 hours after symptom onset. And for an intermediate test result – that is, a troponin level between 5 ng/L and the 99th percentile – patients remained in the ED for retesting 3 hours from the time of presentation, and were subsequently admitted only if their troponin level was rising.

Using the accelerated rule-out strategy, two-thirds of patients were quickly discharged from the ED on the basis of a troponin level below 5 ng/mL, and another 7% were ruled out for MI and discharged from the ED after a 3-hour stay on the basis of their second test.

The primary efficacy outcome was length of stay from initial presentation to the ED to discharge. The duration was 10.1 hours with the guideline-recommended pathway and 6.8 hours with the accelerated rule-out pathway, for a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 3.3-hour difference. Moreover, the proportion of patients discharged directly from the ED without hospital admission increased from 53% to 74%, a 57% jump.

The primary safety outcome was the rate of MI or cardiac death post discharge. The rates at 30 days and 1 year were 0.4% and 2.6%, respectively, in the standard-pathway group, compared with 0.3% and 1.8% with the early rule-out pathway. Those between-group differences favoring the accelerated rule-out pathway weren’t statistically significant, but they provided reassurance that the novel pathway was safe.

Of note, this was the first-ever randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an early rule-out pathway. Other rapid diagnostic pathways are largely based on observational experience and expert opinion, Dr. Mills said.

The assay utilized in the HiSTORIC trial was the Abbott Diagnostics Architect high sensitivity assay. The 5-ng/L threshold for early rule-out was chosen for the trial because an earlier study by Dr. Mills and coinvestigators showed that a level below that cutoff had a 99.6% negative predictive value for MI (Lancet. 2015 Dec 19;386[10012]:2481-8)

The early rule-out pathway was deliberately designed to be simple and pragmatic, according to the cardiologist. “One of the most remarkable observations in this trial was the adherence to the pathway. We prespecified three criteria to evaluate this and demonstrated adherence rates of 86%-92% for each of these criteria. This was despite the pathway being implemented in all consecutive patients at seven different hospitals and used by many hundreds of different clinicians.”

Discussant Hugo A. Katus, MD, called the HiSTORIC study “a really urgently needed and very well-conducted trial.”

“There were very consistently low MI and cardiac death rates at 30 days and 1 year. So this really works,” commented Dr. Katus, who is chief of internal medicine and director of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Heidelberg (Germany) University.

“Accelerated rule-out high-sensitivity cardiac troponin protocols are here to stay,” he declared.

However, Dr. Katus voiced a concern: “By early discharge as rule out, are other life-threatening conditions ignored?”

He raised this issue because of what he views as the substantial 1-year all-cause mortality and return-to-hospital rates of 5.8% and 39.2% in the standard-pathway group and 5.2% and 38.9% in the accelerated rule-out patients in HiSTORIC. An accelerated rule-out strategy should not prohibit a careful clinical work-up, he emphasized.

Dr. Mills discussed the results in a video interview.

The HiSTORIC trial was funded by the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Mills reported receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics and Siemens.

Simultaneous with Dr. Mills’ presentation of the HiSTORIC trial results at the ESC congress, an earlier study that formed the scientific basis for the investigators’ decision to employ distinct risk stratification and diagnostic thresholds for cardiac troponin testing was published online (Circulation. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042866). The actual HiSTORIC trial results will be published later.

Dr. Katus reported holding a patent for a cardiac troponin T test and serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk.

PARIS – An accelerated rule-out pathway, reliant upon a single high-sensitivity cardiac troponin test upon presentation to the ED with suspected acute coronary syndrome, reduced length of stay and hospital admission rates without increasing cardiac events at 30 days or 1 year in a major Scottish study.

“We conclude that implementation of this early rule-out pathway is both effective and safe, and adoption of this pathway will have major benefits for patients and health care systems,” Nicholas L. Mills, MBChB, PhD, said in presenting the results of the HiSTORIC (High-Sensitivity Cardiac Troponin at Presentation to Rule Out Myocardial Infarction) trial at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, in the Unites States, where more than 20 million people per year present to EDs with suspected ACS, the 3.3-hour reduction in length of stay achieved in the HiSTORIC trial by implementing the accelerated rule-out pathway would add up to a $3.6 billion annual savings in bed occupancy alone, according to Dr. Mills, who is chair of cardiology at the University of Edinburgh.

The HiSTORIC pathway incorporates separate thresholds for risk stratification and diagnosis. This strategy is based on an accumulation of persuasive evidence that the major advantage of high-sensitivity cardiac troponin testing is to rule out MI, rather than to rule it in, Dr. Mills explained.

HiSTORIC was a 2-year, prospective, stepped-wedge, cluster-randomized, controlled trial including 31,492 consecutive patients with suspected ACS who presented to seven participating hospitals in Scotland. Patients were randomized, at the hospital level, to one of two management pathways. The control group got a standard guideline-recommended strategy involving high-sensitivity cardiac troponin I testing upon presentation and again 6-12 hours later, with MI being ruled out if the troponin levels were not above the 99th percentile.

In contrast, the novel early rule-out strategy worked as follows: If the patient presented with at least 2 hours of symptoms and the initial troponin I level was below 5 ng/L, then MI was ruled out and the patient was triaged straightaway for outpatient management. If the level was above the 99th percentile, the patient was admitted for serial testing to be done 6-12 hours after symptom onset. And for an intermediate test result – that is, a troponin level between 5 ng/L and the 99th percentile – patients remained in the ED for retesting 3 hours from the time of presentation, and were subsequently admitted only if their troponin level was rising.

Using the accelerated rule-out strategy, two-thirds of patients were quickly discharged from the ED on the basis of a troponin level below 5 ng/mL, and another 7% were ruled out for MI and discharged from the ED after a 3-hour stay on the basis of their second test.

The primary efficacy outcome was length of stay from initial presentation to the ED to discharge. The duration was 10.1 hours with the guideline-recommended pathway and 6.8 hours with the accelerated rule-out pathway, for a statistically significant and clinically meaningful 3.3-hour difference. Moreover, the proportion of patients discharged directly from the ED without hospital admission increased from 53% to 74%, a 57% jump.

The primary safety outcome was the rate of MI or cardiac death post discharge. The rates at 30 days and 1 year were 0.4% and 2.6%, respectively, in the standard-pathway group, compared with 0.3% and 1.8% with the early rule-out pathway. Those between-group differences favoring the accelerated rule-out pathway weren’t statistically significant, but they provided reassurance that the novel pathway was safe.

Of note, this was the first-ever randomized trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of an early rule-out pathway. Other rapid diagnostic pathways are largely based on observational experience and expert opinion, Dr. Mills said.

The assay utilized in the HiSTORIC trial was the Abbott Diagnostics Architect high sensitivity assay. The 5-ng/L threshold for early rule-out was chosen for the trial because an earlier study by Dr. Mills and coinvestigators showed that a level below that cutoff had a 99.6% negative predictive value for MI (Lancet. 2015 Dec 19;386[10012]:2481-8)

The early rule-out pathway was deliberately designed to be simple and pragmatic, according to the cardiologist. “One of the most remarkable observations in this trial was the adherence to the pathway. We prespecified three criteria to evaluate this and demonstrated adherence rates of 86%-92% for each of these criteria. This was despite the pathway being implemented in all consecutive patients at seven different hospitals and used by many hundreds of different clinicians.”

Discussant Hugo A. Katus, MD, called the HiSTORIC study “a really urgently needed and very well-conducted trial.”

“There were very consistently low MI and cardiac death rates at 30 days and 1 year. So this really works,” commented Dr. Katus, who is chief of internal medicine and director of the department of cardiovascular medicine at Heidelberg (Germany) University.

“Accelerated rule-out high-sensitivity cardiac troponin protocols are here to stay,” he declared.

However, Dr. Katus voiced a concern: “By early discharge as rule out, are other life-threatening conditions ignored?”

He raised this issue because of what he views as the substantial 1-year all-cause mortality and return-to-hospital rates of 5.8% and 39.2% in the standard-pathway group and 5.2% and 38.9% in the accelerated rule-out patients in HiSTORIC. An accelerated rule-out strategy should not prohibit a careful clinical work-up, he emphasized.

Dr. Mills discussed the results in a video interview.

The HiSTORIC trial was funded by the British Heart Foundation. Dr. Mills reported receiving research grants from Abbott Diagnostics and Siemens.

Simultaneous with Dr. Mills’ presentation of the HiSTORIC trial results at the ESC congress, an earlier study that formed the scientific basis for the investigators’ decision to employ distinct risk stratification and diagnostic thresholds for cardiac troponin testing was published online (Circulation. 2019 Sep 1. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.042866). The actual HiSTORIC trial results will be published later.

Dr. Katus reported holding a patent for a cardiac troponin T test and serving as a consultant to AstraZeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Novo Nordisk.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

Clinical Pharmacists Improve Patient Outcomes and Expand Access to Care

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

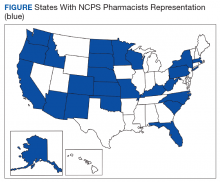

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

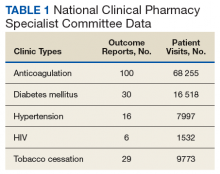

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

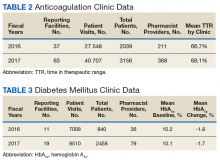

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.

DM management can be complex and time-intensive. NCPS data indicate pharmacist intervention resulted in a mean decrease in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 1.8% from a baseline of 10.2% (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 3 shows data from 30 reports with 16 518 patient visits for DM care.

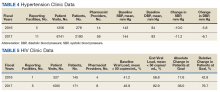

In addition to diet and exercise, medication management plays a vital role in managing hypertension. Patients managed by an NCPS-certified pharmacist experienced a mean decrease in blood pressure from 144/83 to 133/77, putting them in goal for both systolic and diastolic ranges (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 4 shows data from 16 reports and 7997 patient visits for treatment of hypertension.

HIV viral suppression is vital in order to best manage patients with HIV and reduce the risk of transmission. Pharmacistled clinics have shown a 32.9% absolute improvement in patients at goal (viral load < 50 copies/mL), from a mean baseline of 46.0% to a mean final assessment of 71.6% of patients at goal (combined by weighted average visits). Table 5 shows data from 6 reports covering 1532 patient encounters for management of HIV.

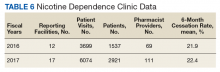

Nicotine dependence includes the use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and vaping products containing nicotine. NCPS-certified pharmacists have successfully helped patients improve their chance of quitting, with a 6-month quit rate of 22.2% (quit rate calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average by visits), which is higher than the national average of 9.4% as reported by the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. 5 Table 6 shows 29 reports covering 9773 patient visits for treatment of nicotine dependence.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the ability of advanced practice pharmacists in multiple locations within the federal sector to improve targeted clinical outcomes in patients with varying diseases. These results are strengthened by their varied origins as well as the improvements observed across the board. Limitations include the general lack of a comparable dataset, manual method of selfreporting by the individual facilities, and the relatively limited array of diseases reported. Although NCPS-certified pharmacists are currently providing care for patients with hepatitis C, asthma, seizure, pain and other diseases not reported here, there are insufficient data collected for FYs 2016 and 2017 to merit inclusion within this report.

Pharmacists are trusted, readily available medication experts. In a clinical role, NCPS-certified pharmacists have increased access to primary care services and demonstrated beneficial impact on important health outcomes as exhibited by the data reported above. Clinical pharmacy is a growing field, and NCPS has displayed continual growth in both the number of NCPS-certified pharmacists and the number of patient encounters performed by these providers. As more pharmacists in all settings collaborate with medical providers to offer high-quality clinical care, these providers will have more opportunity to delegate disease management. Continued reporting of clinical pharmacy outcomes is expected to increase confidence in pharmacists as primary care providers, increase utilization of pharmacy clinical services, and assist in easing the burden of primary care provider shortages across our nation.

Although these outcomes indicate demonstrable benefit in patient-centered outcomes, the need for ongoing assessment and continued improvement is not obviated. Future efforts may benefit from a comparison of alternative approaches to better facilitate the establishment of best practices. Alignment of clinical outcomes with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Electronic Clinical Quality Measures, where applicable, also may prove beneficial by automating the reporting process and thereby decreasing the burden of reporting as well as providing an avenue for standard comparison across multiple populations. Clinical pharmacy interventions have positive outcomes based on the NCPS model, and the NCPS Committee invites other clinical settings to report outcomes data with which to compare.

Conclusion

The NCPS Committee has documented positive outcomes of clinical pharmacy intervention and anticipates growth of the pharmacy profession as additional states and health systems recognize the capacity of the pharmacist to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care. Clinical pharmacists are prepared to address critical health care needs as the US continues to face a PCP shortage.2 The NCPS Committee challenges those participating in clinical pharmacy practice to report outcomes to amplify this body of evidence.

Acknowledgments

NCPS-certified pharmacists provided the outcomes detailed in this report. For document review and edits: Federal Bureau of Prison Publication Review Workgroup; RADM Ty Bingham, USPHS; CAPT Cindy Gunderson, USPHS; CAPT Kevin Brooks, USPHS.

1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 2017.

2. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030, 2018 update. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 2018.

3. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www .accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and _health_system_outcomes.pdf. Updated December 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

4. Lip G, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. CHEST guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154(5):1121-1201.

5. Babb S, Marlarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464.

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.

DM management can be complex and time-intensive. NCPS data indicate pharmacist intervention resulted in a mean decrease in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 1.8% from a baseline of 10.2% (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 3 shows data from 30 reports with 16 518 patient visits for DM care.

In addition to diet and exercise, medication management plays a vital role in managing hypertension. Patients managed by an NCPS-certified pharmacist experienced a mean decrease in blood pressure from 144/83 to 133/77, putting them in goal for both systolic and diastolic ranges (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 4 shows data from 16 reports and 7997 patient visits for treatment of hypertension.

HIV viral suppression is vital in order to best manage patients with HIV and reduce the risk of transmission. Pharmacistled clinics have shown a 32.9% absolute improvement in patients at goal (viral load < 50 copies/mL), from a mean baseline of 46.0% to a mean final assessment of 71.6% of patients at goal (combined by weighted average visits). Table 5 shows data from 6 reports covering 1532 patient encounters for management of HIV.

Nicotine dependence includes the use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and vaping products containing nicotine. NCPS-certified pharmacists have successfully helped patients improve their chance of quitting, with a 6-month quit rate of 22.2% (quit rate calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average by visits), which is higher than the national average of 9.4% as reported by the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. 5 Table 6 shows 29 reports covering 9773 patient visits for treatment of nicotine dependence.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the ability of advanced practice pharmacists in multiple locations within the federal sector to improve targeted clinical outcomes in patients with varying diseases. These results are strengthened by their varied origins as well as the improvements observed across the board. Limitations include the general lack of a comparable dataset, manual method of selfreporting by the individual facilities, and the relatively limited array of diseases reported. Although NCPS-certified pharmacists are currently providing care for patients with hepatitis C, asthma, seizure, pain and other diseases not reported here, there are insufficient data collected for FYs 2016 and 2017 to merit inclusion within this report.

Pharmacists are trusted, readily available medication experts. In a clinical role, NCPS-certified pharmacists have increased access to primary care services and demonstrated beneficial impact on important health outcomes as exhibited by the data reported above. Clinical pharmacy is a growing field, and NCPS has displayed continual growth in both the number of NCPS-certified pharmacists and the number of patient encounters performed by these providers. As more pharmacists in all settings collaborate with medical providers to offer high-quality clinical care, these providers will have more opportunity to delegate disease management. Continued reporting of clinical pharmacy outcomes is expected to increase confidence in pharmacists as primary care providers, increase utilization of pharmacy clinical services, and assist in easing the burden of primary care provider shortages across our nation.

Although these outcomes indicate demonstrable benefit in patient-centered outcomes, the need for ongoing assessment and continued improvement is not obviated. Future efforts may benefit from a comparison of alternative approaches to better facilitate the establishment of best practices. Alignment of clinical outcomes with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Electronic Clinical Quality Measures, where applicable, also may prove beneficial by automating the reporting process and thereby decreasing the burden of reporting as well as providing an avenue for standard comparison across multiple populations. Clinical pharmacy interventions have positive outcomes based on the NCPS model, and the NCPS Committee invites other clinical settings to report outcomes data with which to compare.

Conclusion

The NCPS Committee has documented positive outcomes of clinical pharmacy intervention and anticipates growth of the pharmacy profession as additional states and health systems recognize the capacity of the pharmacist to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care. Clinical pharmacists are prepared to address critical health care needs as the US continues to face a PCP shortage.2 The NCPS Committee challenges those participating in clinical pharmacy practice to report outcomes to amplify this body of evidence.

Acknowledgments

NCPS-certified pharmacists provided the outcomes detailed in this report. For document review and edits: Federal Bureau of Prison Publication Review Workgroup; RADM Ty Bingham, USPHS; CAPT Cindy Gunderson, USPHS; CAPT Kevin Brooks, USPHS.

The US is in the midst of a chronic disease crisis. According to the latest published data available, 60% of Americans have at least 1 chronic condition, and 42% have ≥ 2 chronic conditions.1 Estimates by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) indicate a current shortfall of 13 800 primary care physicians and a projected escalation of that shortage to be between 14 800 and 49 300 physicians by the year 2030.2

The US Public Health Service (USPHS) has used pharmacists since 1930 to provide direct patient care to underserved and vulnerable populations. Clinical pharmacists currently serve in direct patient care roles within the Indian Health Service (IHS), Federal Bureau of Prisons (BOP), Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), and the United States Coast Guard (USCG) in many states (Figure). These pharmacists play a vital role in improving access to care and delivering quality care by managing acute and chronic diseases in collaborative practice settings and pharmacist-managed clinics.

It has previously been reported that in the face of physician shortages and growing demand for primary health care providers, pharmacists are well-equipped and motivated to meet this demand.3 A review of the previous 2 years of outcomes reported by clinical pharmacists certified through the USPHS National Clinical Pharmacy Specialist (NCPS) Committee are presented to demonstrate the impact of pharmacists in advancing the health of the populations they serve and to showcase a model for ameliorating the ongoing physician shortage.

Background

The USPHS NCPS Committee serves to promote uniform competency among clinical pharmacists by establishing national standards for protocols, collaborative practice agreements (CPAs), credentialing and privileging of pharmacists, and by collecting, reviewing, and publishing health care outcomes. The committee, whose constituents include pharmacist and physician subject matter experts from across USPHS agencies, reviews applications and protocols and certifies pharmacists (civilian and uniformed) to recognize an advanced scope of practice in managing various diseases and optimizing medication therapy. NCPScertified pharmacists manage a wide spectrum of diseases, including coagulopathy, asthma, diabetes mellitus (DM), hepatitis C, HIV, hypertension, pain, seizure disorders, and tobacco use disorders.

Clinical pharmacists practicing chronic disease management establish a clinical service in collaboration with 1 or more physicians, physician assistants, or nurse practitioners. In this collaborative practice, the health care practitioner(s) refer patients to be managed by a pharmacist for specific medical needs, such as anticoagulation management, or for holistic medication- focused care (eg, cardiovascular risk reduction, DM management, HIV, hepatitis, or mental health). The pharmacist may order and interpret laboratory tests, check vital signs, perform a limited physical examination, and gather other pertinent information from the patient and the medical record in order to provide the best possible care to the patient.

Medications may be started, stopped, or adjusted, education is provided, and therapeutic lifestyle interventions may be recommended. The pharmacist-run clinic provides the patient more frequent interaction with a health care professional (pharmacist) and focused disease management. As a result, pharmacists increase access to care and allow the medical team to handle a larger panel of patients as the practitioner delegates specified diseases to the pharmacist- managed clinic(s). The number of NCPS-certified pharmacists grew 46% from 2012 (n = 230) to 2017 (n = 336), reflecting an evolution of pharmacists’ practice to better meet the need of patients across the nation.

Methods

The NCPS Committee requires NCPS pharmacists to report data annually from all patients referred for pharmacist management for specific diseases in which they have been certified. The data reflect the patient’s clinical outcome goal status at the time of referral as well as the same status at the end of the reporting period or on release from the pharmacist-run clinic. These data describe the impact prescribing pharmacists have on patients reaching clinical outcome goals acting as the team member specializing in the medication selection and dosing aspect of care.

These records were reviewed for the fiscal year (FY) periods of October 1, 2015 to September 30, 2016 (FY 2016) and October 1, 2016 to September 30, 2017 (FY 2017). A systematic review of submitted reports resulted in 181 reports that included all requested data points for the disease as published here for FYs 2016 and 2017. These include 66 reports from FY 2016 and 115 reports from FY 2017; they cover 76 BOP and IHS facilities located across 24 states. Table 1 shows the number of outcome reports collected from 104 075 patient visits in pharmacist-run clinics in FYs 2016 and 2017.

Results

The following tables represent the standardized outcomes collected by NCPS-certified pharmacists providing direct patient care. Patients on anticoagulants (eg, warfarin) require special monitoring and education for drug interactions and adverse effects. NCPS-certified pharmacists were able to achieve a mean patient time in therapeutic range (TTR) of 67.6% (regardless of indication) over the 2 years (calculated per each facility by Rosendaal method of linear interpolation then combined in a weighted average per visit). The TTR produced by NCPS-certified pharmacists are consistent with Chest Guidelines and Expert Panel Report suggesting that TTR should be between 65% and 70%.4 Table 2 shows data from 100 reports with 68 255 patient visits for anticoagulation management.

DM management can be complex and time-intensive. NCPS data indicate pharmacist intervention resulted in a mean decrease in hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) of 1.8% from a baseline of 10.2% (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 3 shows data from 30 reports with 16 518 patient visits for DM care.

In addition to diet and exercise, medication management plays a vital role in managing hypertension. Patients managed by an NCPS-certified pharmacist experienced a mean decrease in blood pressure from 144/83 to 133/77, putting them in goal for both systolic and diastolic ranges (decrease calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average per visit). Table 4 shows data from 16 reports and 7997 patient visits for treatment of hypertension.

HIV viral suppression is vital in order to best manage patients with HIV and reduce the risk of transmission. Pharmacistled clinics have shown a 32.9% absolute improvement in patients at goal (viral load < 50 copies/mL), from a mean baseline of 46.0% to a mean final assessment of 71.6% of patients at goal (combined by weighted average visits). Table 5 shows data from 6 reports covering 1532 patient encounters for management of HIV.

Nicotine dependence includes the use of cigarettes, cigars, pipe tobacco, chewing tobacco, and vaping products containing nicotine. NCPS-certified pharmacists have successfully helped patients improve their chance of quitting, with a 6-month quit rate of 22.2% (quit rate calculated per each facility then combined by weighted average by visits), which is higher than the national average of 9.4% as reported by the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention. 5 Table 6 shows 29 reports covering 9773 patient visits for treatment of nicotine dependence.

Discussion

These data demonstrate the ability of advanced practice pharmacists in multiple locations within the federal sector to improve targeted clinical outcomes in patients with varying diseases. These results are strengthened by their varied origins as well as the improvements observed across the board. Limitations include the general lack of a comparable dataset, manual method of selfreporting by the individual facilities, and the relatively limited array of diseases reported. Although NCPS-certified pharmacists are currently providing care for patients with hepatitis C, asthma, seizure, pain and other diseases not reported here, there are insufficient data collected for FYs 2016 and 2017 to merit inclusion within this report.

Pharmacists are trusted, readily available medication experts. In a clinical role, NCPS-certified pharmacists have increased access to primary care services and demonstrated beneficial impact on important health outcomes as exhibited by the data reported above. Clinical pharmacy is a growing field, and NCPS has displayed continual growth in both the number of NCPS-certified pharmacists and the number of patient encounters performed by these providers. As more pharmacists in all settings collaborate with medical providers to offer high-quality clinical care, these providers will have more opportunity to delegate disease management. Continued reporting of clinical pharmacy outcomes is expected to increase confidence in pharmacists as primary care providers, increase utilization of pharmacy clinical services, and assist in easing the burden of primary care provider shortages across our nation.

Although these outcomes indicate demonstrable benefit in patient-centered outcomes, the need for ongoing assessment and continued improvement is not obviated. Future efforts may benefit from a comparison of alternative approaches to better facilitate the establishment of best practices. Alignment of clinical outcomes with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Electronic Clinical Quality Measures, where applicable, also may prove beneficial by automating the reporting process and thereby decreasing the burden of reporting as well as providing an avenue for standard comparison across multiple populations. Clinical pharmacy interventions have positive outcomes based on the NCPS model, and the NCPS Committee invites other clinical settings to report outcomes data with which to compare.

Conclusion

The NCPS Committee has documented positive outcomes of clinical pharmacy intervention and anticipates growth of the pharmacy profession as additional states and health systems recognize the capacity of the pharmacist to provide high-quality, multidisciplinary patient care. Clinical pharmacists are prepared to address critical health care needs as the US continues to face a PCP shortage.2 The NCPS Committee challenges those participating in clinical pharmacy practice to report outcomes to amplify this body of evidence.

Acknowledgments

NCPS-certified pharmacists provided the outcomes detailed in this report. For document review and edits: Federal Bureau of Prison Publication Review Workgroup; RADM Ty Bingham, USPHS; CAPT Cindy Gunderson, USPHS; CAPT Kevin Brooks, USPHS.

1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 2017.

2. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030, 2018 update. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 2018.

3. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www .accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and _health_system_outcomes.pdf. Updated December 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

4. Lip G, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. CHEST guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154(5):1121-1201.

5. Babb S, Marlarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464.

1. Buttorff C, Ruder T, Bauman M. Multiple Chronic Conditions in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corp; 2017.

2. Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: projections from 2016 to 2030, 2018 update. Association of American Medical Colleges. March 2018.

3. Giberson S, Yoder S, Lee MP. Improving patient and health system outcomes through advanced pharmacy practice. A report to the U.S. Surgeon General 2011. https://www .accp.com/docs/positions/misc/improving_patient_and _health_system_outcomes.pdf. Updated December 2011. Accessed September 11, 2019.

4. Lip G, Banerjee A, Boriani G, et al. Antithrombotic therapy for atrial fibrillation. CHEST guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest. 2018;154(5):1121-1201.

5. Babb S, Marlarcher A, Schauer G, Asman K, Jamal A. Quitting smoking among adults—United States, 2000-2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2017;65(52):1457-1464.

Smoking, inactivity most powerful post-MI lifestyle risk factors

PARIS – All lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk factors aren’t equal in power when it comes to secondary prevention after a first acute MI, according to a massive Swedish registry study.

Insufficient physical activity and current smoking were consistently the strongest risk factors for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and other key adverse outcomes in an analysis from the SWEDEHEART registry. The study included 65,002 patients discharged after a first MI and 325,010 age- and sex-matched controls with no prior MI followed for a median of 5.5 years and maximum of 12, Emil Hagstrom, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Strongest lifestyle risk factors

The study examined the long-term relative importance of control of six major lifestyle risk factors for secondary cardiovascular prevention: current smoking, insufficient physical activity, blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or more, obesity, a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, and an LDL cholesterol of 70 mg/dL or more. Notably, two risk factors that physicians often emphasize in working with their patients with known coronary heart disease – an elevated LDL cholesterol and obesity – barely moved the needle. Out of the six risk factors scrutinized, those two consistently showed the weakest association with long-term risk of adverse outcomes. Occupying the middle ground in terms of predictive strength were hypertension and elevated blood glucose, according to Dr. Hagstrom, a cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

Risk factor status was assessed 6-10 weeks post MI. Insufficient physical activity was defined as not engaging in at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise on at least 5 days per week. And when Dr. Hagstrom recalculated the risk of adverse outcomes using an LDL cholesterol threshold of 55 mg/dL rather than using 70 mg/dL, as recommended in new ESC secondary prevention guidelines released during the congress, the study results remained unchanged.

Cumulative effects

A key SWEDEHEART finding underscoring the importance of lifestyle in secondary prevention was that a linear stepwise relationship existed between the number of risk factors at target levels and the risk of all of the various adverse outcomes assessed, including stroke and heart failure hospitalization as well as all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and major bleeding.

Moreover, patients with none of the six risk factors outside of target when assessed after their MI had the same risks of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and stroke as the matched controls.

For example, in an analysis adjusted for comorbid cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and dementia, post-MI patients with zero risk factors had the same long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality as controls without a history of MI at baseline. With one risk factor not at target, a patient had a 41% increased risk compared with controls, a statistically significant difference. With two out-of-whack risk factors, the risk climbed to 102%. With three, 185%. With four risk factors not at target, the all-cause mortality risk jumped to 291%. And patients with more than four of the six risk factors not at target had a 409% greater risk of all-cause mortality than controls who had never had a heart attack.

When Dr. Hagstrom stratified subjects by age at baseline – up to 55, 56-64, 65-70, and 70-75 years – he discovered that, regardless of age, patients with zero risk factors had the same risk of all-cause mortality and other adverse outcomes as controls. However, when risk factors were present, younger patients consistently had a higher risk of all adverse outcomes than older patients with the same number of risk factors. When asked for an explanation of this phenomenon, Dr. Hagstrom noted that younger patients with multiple risk factors have a longer time to be exposed to and accumulate risk.

Follow-up of the study cohort will continue for years to come, the cardiologist promised.

At an ESC congress highlights session that closed out the meeting, Eva Prescott, MD, put the SWEDEHEART study at the top of her list of important developments in preventive cardiology arising from the congress.

“This is an excellent national registry I think we’re all envious of,” commented Dr. Prescott, a cardiologist at Copenhagen University. “The conclusion of this registry-based data, I think, is that lifestyle really remains at the core of prevention of cardiovascular events still today.”

The SWEDEHEART study analysis was funded free of commercial support. Dr. Hagstrom reported serving as a consultant to or receiving speakers’ fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

PARIS – All lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk factors aren’t equal in power when it comes to secondary prevention after a first acute MI, according to a massive Swedish registry study.

Insufficient physical activity and current smoking were consistently the strongest risk factors for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and other key adverse outcomes in an analysis from the SWEDEHEART registry. The study included 65,002 patients discharged after a first MI and 325,010 age- and sex-matched controls with no prior MI followed for a median of 5.5 years and maximum of 12, Emil Hagstrom, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Strongest lifestyle risk factors

The study examined the long-term relative importance of control of six major lifestyle risk factors for secondary cardiovascular prevention: current smoking, insufficient physical activity, blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or more, obesity, a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, and an LDL cholesterol of 70 mg/dL or more. Notably, two risk factors that physicians often emphasize in working with their patients with known coronary heart disease – an elevated LDL cholesterol and obesity – barely moved the needle. Out of the six risk factors scrutinized, those two consistently showed the weakest association with long-term risk of adverse outcomes. Occupying the middle ground in terms of predictive strength were hypertension and elevated blood glucose, according to Dr. Hagstrom, a cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

Risk factor status was assessed 6-10 weeks post MI. Insufficient physical activity was defined as not engaging in at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise on at least 5 days per week. And when Dr. Hagstrom recalculated the risk of adverse outcomes using an LDL cholesterol threshold of 55 mg/dL rather than using 70 mg/dL, as recommended in new ESC secondary prevention guidelines released during the congress, the study results remained unchanged.

Cumulative effects

A key SWEDEHEART finding underscoring the importance of lifestyle in secondary prevention was that a linear stepwise relationship existed between the number of risk factors at target levels and the risk of all of the various adverse outcomes assessed, including stroke and heart failure hospitalization as well as all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and major bleeding.

Moreover, patients with none of the six risk factors outside of target when assessed after their MI had the same risks of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and stroke as the matched controls.

For example, in an analysis adjusted for comorbid cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and dementia, post-MI patients with zero risk factors had the same long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality as controls without a history of MI at baseline. With one risk factor not at target, a patient had a 41% increased risk compared with controls, a statistically significant difference. With two out-of-whack risk factors, the risk climbed to 102%. With three, 185%. With four risk factors not at target, the all-cause mortality risk jumped to 291%. And patients with more than four of the six risk factors not at target had a 409% greater risk of all-cause mortality than controls who had never had a heart attack.

When Dr. Hagstrom stratified subjects by age at baseline – up to 55, 56-64, 65-70, and 70-75 years – he discovered that, regardless of age, patients with zero risk factors had the same risk of all-cause mortality and other adverse outcomes as controls. However, when risk factors were present, younger patients consistently had a higher risk of all adverse outcomes than older patients with the same number of risk factors. When asked for an explanation of this phenomenon, Dr. Hagstrom noted that younger patients with multiple risk factors have a longer time to be exposed to and accumulate risk.

Follow-up of the study cohort will continue for years to come, the cardiologist promised.

At an ESC congress highlights session that closed out the meeting, Eva Prescott, MD, put the SWEDEHEART study at the top of her list of important developments in preventive cardiology arising from the congress.

“This is an excellent national registry I think we’re all envious of,” commented Dr. Prescott, a cardiologist at Copenhagen University. “The conclusion of this registry-based data, I think, is that lifestyle really remains at the core of prevention of cardiovascular events still today.”

The SWEDEHEART study analysis was funded free of commercial support. Dr. Hagstrom reported serving as a consultant to or receiving speakers’ fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

PARIS – All lifestyle-related cardiovascular risk factors aren’t equal in power when it comes to secondary prevention after a first acute MI, according to a massive Swedish registry study.

Insufficient physical activity and current smoking were consistently the strongest risk factors for all-cause mortality, major adverse cardiovascular events, and other key adverse outcomes in an analysis from the SWEDEHEART registry. The study included 65,002 patients discharged after a first MI and 325,010 age- and sex-matched controls with no prior MI followed for a median of 5.5 years and maximum of 12, Emil Hagstrom, MD, PhD, reported at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Strongest lifestyle risk factors

The study examined the long-term relative importance of control of six major lifestyle risk factors for secondary cardiovascular prevention: current smoking, insufficient physical activity, blood pressure of 140/90 mm Hg or more, obesity, a fasting blood glucose of at least 126 mg/dL, and an LDL cholesterol of 70 mg/dL or more. Notably, two risk factors that physicians often emphasize in working with their patients with known coronary heart disease – an elevated LDL cholesterol and obesity – barely moved the needle. Out of the six risk factors scrutinized, those two consistently showed the weakest association with long-term risk of adverse outcomes. Occupying the middle ground in terms of predictive strength were hypertension and elevated blood glucose, according to Dr. Hagstrom, a cardiologist at Uppsala (Sweden) University.

Risk factor status was assessed 6-10 weeks post MI. Insufficient physical activity was defined as not engaging in at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity exercise on at least 5 days per week. And when Dr. Hagstrom recalculated the risk of adverse outcomes using an LDL cholesterol threshold of 55 mg/dL rather than using 70 mg/dL, as recommended in new ESC secondary prevention guidelines released during the congress, the study results remained unchanged.

Cumulative effects

A key SWEDEHEART finding underscoring the importance of lifestyle in secondary prevention was that a linear stepwise relationship existed between the number of risk factors at target levels and the risk of all of the various adverse outcomes assessed, including stroke and heart failure hospitalization as well as all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and major bleeding.

Moreover, patients with none of the six risk factors outside of target when assessed after their MI had the same risks of all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, and stroke as the matched controls.

For example, in an analysis adjusted for comorbid cancer, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and dementia, post-MI patients with zero risk factors had the same long-term risk of cardiovascular mortality as controls without a history of MI at baseline. With one risk factor not at target, a patient had a 41% increased risk compared with controls, a statistically significant difference. With two out-of-whack risk factors, the risk climbed to 102%. With three, 185%. With four risk factors not at target, the all-cause mortality risk jumped to 291%. And patients with more than four of the six risk factors not at target had a 409% greater risk of all-cause mortality than controls who had never had a heart attack.

When Dr. Hagstrom stratified subjects by age at baseline – up to 55, 56-64, 65-70, and 70-75 years – he discovered that, regardless of age, patients with zero risk factors had the same risk of all-cause mortality and other adverse outcomes as controls. However, when risk factors were present, younger patients consistently had a higher risk of all adverse outcomes than older patients with the same number of risk factors. When asked for an explanation of this phenomenon, Dr. Hagstrom noted that younger patients with multiple risk factors have a longer time to be exposed to and accumulate risk.

Follow-up of the study cohort will continue for years to come, the cardiologist promised.

At an ESC congress highlights session that closed out the meeting, Eva Prescott, MD, put the SWEDEHEART study at the top of her list of important developments in preventive cardiology arising from the congress.

“This is an excellent national registry I think we’re all envious of,” commented Dr. Prescott, a cardiologist at Copenhagen University. “The conclusion of this registry-based data, I think, is that lifestyle really remains at the core of prevention of cardiovascular events still today.”

The SWEDEHEART study analysis was funded free of commercial support. Dr. Hagstrom reported serving as a consultant to or receiving speakers’ fees from Amgen, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi.

REPORTING FROM THE ESC CONGRESS 2019

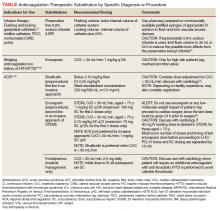

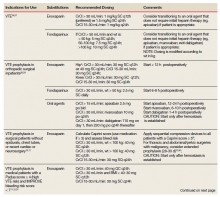

Heparin Drug Shortage Conservation Strategies

Heparin is the anticoagulant of choice when a rapid anticoagulant is indicated: Onset of action is immediate when administered IV as a bolus.1 The major anticoagulant effect of heparin is mediated by heparin/antithrombin (AT) interaction. Heparin/AT inactivates factor IIa (thrombin) and factors Xa, IXa, XIa, and XIIa. Heparin is approved for multiple indications, such as venous thromboembolism (VTE) treatment and prophylaxis of medical and surgical patients; stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation (AF); acute coronary syndrome (ACS); vascular and cardiac surgeries; and various interventional procedures (eg, diagnostic angiography and percutaneous coronary intervention [PCI]). It also is used as an anticoagulant in blood transfusions, extracorporeal circulation, and for maintaining patency of central vascular access devices (CVADs).

About 60% of the crude heparin used to manufacture heparin in the US originates in China, derived from porcine mucosa. African swine fever, a contagious virus with no cure, has eliminated about 25% to 35% of China’s pig population, or about 150 million pigs. In July 2019, members of the US House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce sent a letter to the US Food and Drug Administration asking for details on the potential impact of African swine fever on the supply of heparin.2

The US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) heath care system is currently experiencing a shortage of heparin vials and syringes. It is unclear when resolution of this shortage will occur as it could resolve within several weeks or as late as January 2020.3 Although vials and syringes are the current products that are affected, it is possible the shortage may eventually include IV heparin bags as well.

Since the foremost objective of VA health care providers is to provide timely access to medications for veterans, strategies to conserve unfractionated heparin (UfH) must be used since it is a first-line therapy where few evidence-based alternatives exist. Conservation strategies may include drug rationing, therapeutic substitution, and compounding of needed products using the limited stock available in the pharmacy.4 It is important that all staff are educated on facility strategies in order to be familiar with alternatives and limit the potential for near misses, adverse events, and provider frustration.

In shortage situations, the VA-Pharmacy Benefits Management (PBM) defers decisions regarding drug preservation, processes to shift to viable alternatives, and the best practice for safe transitions to local facilities and their subject matter experts.5 At the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, a 1A, tertiary, dual campus health care system, a pharmacy task force has formed to track drug shortages impacting the facility’s efficiencies and budgets. This group communicates with the Pharmacy and Therapeutics committee about potential risks to patient care and develops shortage briefs (following an SBAR [situation, background, assessment, recommendation] design) generally authored and championed by at least 1 clinical pharmacy specialist and supervising physicians who are field experts. Prior to dissemination, the SBAR undergoes a rapid peer-review process.

To date, VA PBM has not issued specific guidance on how pharmacists should proceed in case of a shortage. However, we recommend strategies that may be considered for implementation during a potential UfH shortage. For example, pharmacists can use therapeutic alternatives for which best available evidence suggests no disadvantage.4 The Table lists alternative agents according to indication and patient-specific considerations that may preclude use. Existing UfH products may also be used for drug compounding (eg, use current stock to provide an indicated aliquot) to meet the need of prioritized patients.4 In addition, we suggest prioritizing current UfH/heparinized saline for use for the following groups of patients4:

- Emergent/urgent cardiac surgery1,6;

- Hemodialysis patients1,7-9 for which the low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) dalteparin is deemed inappropriate or the patient is not monitored in the intensive care unit for regional citrate administration;

- VTE prophylaxis for patients with epidurals or chest tubes for which urgent invasive management may occur, recent cardiac or neurosurgery, or for patients with a creatine clearance < 15 mL/min or receiving hemodialysis10-12;

- Vascular surgery (eg, limb ischemia) and interventions (eg, carotid stenting, endarterectomy)13,14;

- Mesenteric ischemia (venous thrombosis) with a potential to proceed to laparotomy15;

- Critically ill patients with arterial lines for which normal saline is deemed inappropriate for line flushing16;

- Electrophysiology procedures (eg, AF ablation)17; and

- Contraindication to use of a long-acting alternative listed in the table or a medical necessity exists for using a rapidly reversible agent. Examples for this category include but are not limited to recent gastrointestinal bleeding, central nervous system lesion, and select neurologic diagnoses (eg, cerebral venous sinus thrombosis with hemorrhage, thrombus in vertebral basilar system or anterior circulation, intraparenchymal hemorrhage plus mechanical valve, medium to large cardioembolic stroke with intracardiac thrombus).

Conclusion

The UfH drug shortage represents a significant threat to public health and is a major challenge for US health care systems, including the Veterans Health Administration. Overreliance on a predominant source of crude heparin has affected multiple UfH manufacturers and products. Current alternatives to UfH include low-molecular-weight heparins, IV direct thrombin inhibitors, and SC fondaparinux, with selection supported by guidelines or evolving literature. However, the shortage has the potential to expand to other injectables, such as dalteparin and enoxaparin, and severely limit care for veterans. It is vital that clinicians rapidly address the current shortage by creating a plan to develop efficient and equitable access to UfH, continue to assess supply and update stakeholders, and select evidence-based alternatives while maintaining focus on efficacy and safety.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Ashley Yost, PharmD, for her coordination of the multidisciplinary task force assigned to efficiently manage the heparin drug shortage. This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System in Nashville, Tennessee.

1. Hirsh J, Warkentin TE, Shaughnessy SG, et al. Heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin mechanisms of action, pharmacokinetics, dosing, monitoring, efficacy, and safety. Chest. 2001;119(1):64S-94S.

2. Bipartisan E&C leaders request FDA briefing on threat to U.S. heparin supply [press release]. Washington, DC: House Committee on Energy and Commerce; July 30, 2019. https://energycommerce.house.gov/newsroom/press-releases/bipartisan-ec-leaders-request-fda-briefing-on-threat-to-us-heparin-supply. Accessed September 19, 2019.

3. American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Drug Shortages. Heparin injection. https://www.ashp.org/Drug-Shortages/Current-Shortages/Drug-Shortages-List?page=CurrentShortages. Accessed September 19, 2019.

4. Reed BN, Fox ER, Konig M, et al. The impact of drug shortages on patients with cardiovascular disease: causes, consequences, and a call to action. Am Heart J. 2016;175:130-141.

5. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, VISN Pharmacist Executives, The Center For Medication Safety. Heparin supply status: frequently asked questions. PBM-2018-02. https://www.pbm.va.gov/PBM/vacenterformedicationsafety/HeparinandSalineSyringeRecallDuetoContamination_NationalPBMPati.pdf. Published May 3, 2018. Accessed September 11, 2019.

6. Shore-Lesserson I, Baker RA, Ferraris VA, et al. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, and the American Society of ExtraCorporeal Technology: Clinical Practice Guidelines-anticoagulation during cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 2018;105(2):650-662.

7. Soroka S, Agharazii M, Donnelly S, et al. An adjustable dalteparin sodium dose regimen for the prevention of clotting in the extracorporeal circuit in hemodialysis: a clinical trial of safety and efficacy (the PARROT Study). Can J Kidney Health Dis. 2018;5:1-12.

8. Shantha GPS, Kumar AA, Sethi M, Khanna RC, Pancholy SB. Efficacy and safety of low molecular weight heparin compared to unfractionated heparin for chronic outpatient hemodialysis in end stage renal disease: systematic review and meta-analysis. Peer J. 2015;3:e835.

9. Kessler M, Moureau F, and Nguyen P. Anticoagulation in chronic hemodialysis: progress toward an optimal approach. Semin Dial. 2015;28(5):474-489.

10. Gould MK, Garcia DA, Wren SM, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonorthopedic surgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e227s-e277S.

11. Kaye AD, Brunk AJ, Kaye AJ, et al. Regional anesthesia in patients on anticoagulation therapies—evidence-based recommendations. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2019;23(9):67.

12. Kahn SR, Lim W, Dunn AS, et al. Prevention of VTE in nonsurgical patients: Antithrombotic Therapy and Prevention of Thrombosis, 9th ed: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines. Chest. 2012;141(2)(suppl):e195S-e226S.