User login

The long road to a PsA prevention trial

About one-third of all patients with psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition that comes with a host of vague symptoms and no definitive blood test for diagnosis. Prevention trials could help to identify higher-risk groups for PsA, with a goal to catch disease early and improve outcomes. The challenge is finding enough participants in a disease that lacks a clear clinical profile, then tracking them for long periods of time to generate any significant data.

Researchers have been taking several approaches to improve outcomes in PsA, Christopher Ritchlin, MD, MPH, chief of the allergy/immunology and rheumatology division at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “We are in the process of identifying biomarkers and imaging findings that characterize psoriasis patients at high risk to develop PsA.”

The next step would be to design an interventional trial to treat high-risk patients before they develop musculoskeletal inflammation, with a goal to delay onset, attenuate severity, or completely prevent arthritis. The issue now is “we don’t know which agents would be most effective in this prevention effort,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Biologics that target specific pathways significant in PsA pathogenesis are an appealing prospect. However, “it may be that alternative therapies such as methotrexate or ultraviolet A radiation therapy, for example, may help arrest the development of joint inflammation.”

Underdiagnosis impedes research

Several factors may undermine this important research.

For one, psoriasis patients are often unaware that they have PsA. “Many times they are diagnosed incorrectly by nonspecialists. As a consequence, they do not get access to appropriate medications,” said Lihi Eder, MD, PhD, staff rheumatologist and director of the psoriatic arthritis research program at the University of Toronto’s Women’s College Research Institute.

The condition also lacks a good diagnostic tool, Dr. Eder said. There’s no blood test that identifies this condition in the same manner as RA and lupus, for example. For these conditions, a general practitioner such as a family physician may conduct a blood test, and if positive, refer them to a rheumatologist. Such a system doesn’t exist for PsA. “Instead, nonspecialists are ordering tests and when they’re negative, they assume wrongly that these patients don’t have a rheumatic condition,” she explained.

Many clinicians aren’t that well versed in PsA, although dermatology has taken steps to become better educated. As a result, more dermatologists are referring patients to rheumatologists for PsA. Despite this small step forward, the heterogeneous clinical presentation of this condition makes diagnosis especially difficult. Unlike RA, which presents with inflammation in the joints, PsA can present as back or joint pain, “which makes our life as rheumatologists much more complex,” Dr. Eder said.

Defining a risk group

Most experts agree that the presence of psoriasis isn’t sufficient to conduct a prevention trial. Ideally, the goal of a prevention study would be to identify a critical subgroup of psoriasis patients at high risk of developing PsA.

However, this presents a challenging task, Dr. Eder said. Psoriasis is a risk factor for PsA, but most patients with psoriasis won’t actually develop it. Given that there’s an incidence rate of 2.7% a year, “you would need to recruit many hundreds of psoriasis patients and follow them for a long period of time until you have enough events.”

Moving forward with prevention studies calls for a better definition of the PsA risk group, according to Georg Schett, MD, chair of internal medicine in the department of internal medicine, rheumatology, and immunology at Friedrich‐Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany. “That’s very important, because you need to define such a group to make a prevention trial feasible. The whole benefit of such an approach is to catch the disease early, to say that psoriasis is a biomarker that’s linked to psoriatic arthritis.”

Indicators of risk other than psoriasis, such as pain, inflammation seen in ultrasound or MRI, and other specificities of psoriasis, could be used to define a population where interception can take place, Dr. Schett added. Although it’s not always clinically recognized, the combination of pain and structural lesions can be an indicator for developing PsA.

One prospective study he and his colleagues conducted in 114 psoriasis patients cited structural entheseal lesions and low cortical volumetric bone mineral density as risk factors in developing PsA. Keeping these factors in mind, Dr. Schett expects to see more studies in biointervention in these populations, “with the idea to prevent the onset of PsA and also decrease pain and subcutaneous inflammation.”

Researchers are currently working to identify those high-risk patients to include in an interventional trial, Dr. Ritchlin said.

That said, there’s been a great deal of “clinical trial angst” among investigators, Dr. Ritchlin noted. Outcomes in clinical trials for a wide range of biologic agents have not demonstrated significant advances in outcomes, compared with initial studies with anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) agents 20 years ago.

Combination biologics

One approach that’s generated some interest is the use of combination biologics medications. Sequential inhibition of cytokines such as interleukin-17A and TNF-alpha is of interest given their central contribution in joint inflammation and damage. “The challenge here of course is toxicity,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Trials that combined blockade of IL-1 and TNF-alpha in a RA trial years ago resulted in significant adverse events without improving outcomes.

Comparatively, a recent study in The Lancet Rheumatology reported success in using the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) to reduce PsA symptoms. Tested on patients in the FUTURE 2 trial, investigators demonstrated that secukinumab in 300- and 150-mg doses safely reduced PsA signs and symptoms over a period of 5 years. Secukinumab also outperformed the TNF-alpha inhibitor adalimumab in 853 PsA patients in the 52-week, randomized, head-to-head, phase 3b EXCEED study, which was recently reported in The Lancet. Articular outcomes were similar between the two therapies, yet the secukinumab group did markedly better in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores, compared with the adalimumab group.

Based on these findings, “I suspect that studies examining the efficacy of combination biologics for treatment of PsA will surface in the near future,” Dr. Ritchlin said.

Yet another approach encompasses the spirit of personalized medicine. Clinicians often treat PsA patients empirically because they lack biomarkers that indicate which drug may be most effective for an individual patient, Dr. Ritchlin said. However, the technologies for investigating specific cell subsets in both the blood and tissues have advanced greatly over the last decade. “I am confident that a more precision medicine–based approach to the diagnosis and treatment of PsA is on the near horizon.”

Diet as an intervention

Other research has looked at the strong link between metabolic abnormalities and psoriasis and PsA. Some diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, show promise in improving the metabolic profile of these patients, making it a candidate as a potential intervention to reduce PsA risk. Another strategy would be to focus on limiting calories and promoting weight reduction.

One study in the British Journal of Dermatology looked at the associations between PsA and smoking, alcohol, and body mass index, identifying obesity as an important risk factor. Analyzing more than 90,000 psoriasis cases from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink between 1998 and 2014, researchers identified 1,409 PsA diagnoses. Among this cohort, researchers found an association between PsA and increased body mass index and moderate drinking. This finding underscores the need to support weight-reduction programs to reduce risk, Dr. Eder and Alexis Ogdie, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in a related editorial.

While observational studies such as this one provide further guidance for interventional trials, confounders can affect results. “Patients who lost weight could have made a positive lifestyle change (e.g., a dietary change) that was associated with the decreased risk for PsA rather than weight loss specifically, or they could have lost weight for unhealthy reasons,” Dr. Eder and Dr. Ogdie explained. Future research could address whether weight loss or other interventional factors may reduce PsA progression.

To make this work, “we would need to select patients that would benefit from diet. Secondly, we’d need to identify what kind of diet would be good for preventing PsA. And we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder further elaborated.

As with any prevention trial, the challenge is to follow patients over a long period of time, making sure they comply with the restrictions of the prescribed diet, Dr. Eder noted. “I do think it’s a really exciting type of intervention because it’s something that people are very interested in. There’s little risk of side effects, and it’s not very expensive.”

In other research on weight-loss methods, an observational study from Denmark found that bariatric surgery, especially gastric bypass, reduced the risk of developing PsA. This suggests that weight reduction by itself is important, “although we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder said.

A risk model for PsA

Dr. Eder and colleagues have been working on an algorithm that will incorporate clinical information (for example, the presence of nail lesions and the severity of psoriasis) to provide an estimated risk of developing PsA over the next 5 years. Subsequently, this information could be used to identify high-risk psoriasis patients as candidates for a prevention trial.

Other groups are looking at laboratory or imaging biomarkers to help develop PsA prediction models, she said. “Once we have these tools, we can move to next steps of prevention trials. What kinds of interventions should we apply? Are we talking biologic medications or other lifestyle interventions like diet? We are still at the early stages. However, with an improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms and risk factors we are expected to see prevention trials for PsA in the future.”

About one-third of all patients with psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition that comes with a host of vague symptoms and no definitive blood test for diagnosis. Prevention trials could help to identify higher-risk groups for PsA, with a goal to catch disease early and improve outcomes. The challenge is finding enough participants in a disease that lacks a clear clinical profile, then tracking them for long periods of time to generate any significant data.

Researchers have been taking several approaches to improve outcomes in PsA, Christopher Ritchlin, MD, MPH, chief of the allergy/immunology and rheumatology division at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “We are in the process of identifying biomarkers and imaging findings that characterize psoriasis patients at high risk to develop PsA.”

The next step would be to design an interventional trial to treat high-risk patients before they develop musculoskeletal inflammation, with a goal to delay onset, attenuate severity, or completely prevent arthritis. The issue now is “we don’t know which agents would be most effective in this prevention effort,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Biologics that target specific pathways significant in PsA pathogenesis are an appealing prospect. However, “it may be that alternative therapies such as methotrexate or ultraviolet A radiation therapy, for example, may help arrest the development of joint inflammation.”

Underdiagnosis impedes research

Several factors may undermine this important research.

For one, psoriasis patients are often unaware that they have PsA. “Many times they are diagnosed incorrectly by nonspecialists. As a consequence, they do not get access to appropriate medications,” said Lihi Eder, MD, PhD, staff rheumatologist and director of the psoriatic arthritis research program at the University of Toronto’s Women’s College Research Institute.

The condition also lacks a good diagnostic tool, Dr. Eder said. There’s no blood test that identifies this condition in the same manner as RA and lupus, for example. For these conditions, a general practitioner such as a family physician may conduct a blood test, and if positive, refer them to a rheumatologist. Such a system doesn’t exist for PsA. “Instead, nonspecialists are ordering tests and when they’re negative, they assume wrongly that these patients don’t have a rheumatic condition,” she explained.

Many clinicians aren’t that well versed in PsA, although dermatology has taken steps to become better educated. As a result, more dermatologists are referring patients to rheumatologists for PsA. Despite this small step forward, the heterogeneous clinical presentation of this condition makes diagnosis especially difficult. Unlike RA, which presents with inflammation in the joints, PsA can present as back or joint pain, “which makes our life as rheumatologists much more complex,” Dr. Eder said.

Defining a risk group

Most experts agree that the presence of psoriasis isn’t sufficient to conduct a prevention trial. Ideally, the goal of a prevention study would be to identify a critical subgroup of psoriasis patients at high risk of developing PsA.

However, this presents a challenging task, Dr. Eder said. Psoriasis is a risk factor for PsA, but most patients with psoriasis won’t actually develop it. Given that there’s an incidence rate of 2.7% a year, “you would need to recruit many hundreds of psoriasis patients and follow them for a long period of time until you have enough events.”

Moving forward with prevention studies calls for a better definition of the PsA risk group, according to Georg Schett, MD, chair of internal medicine in the department of internal medicine, rheumatology, and immunology at Friedrich‐Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany. “That’s very important, because you need to define such a group to make a prevention trial feasible. The whole benefit of such an approach is to catch the disease early, to say that psoriasis is a biomarker that’s linked to psoriatic arthritis.”

Indicators of risk other than psoriasis, such as pain, inflammation seen in ultrasound or MRI, and other specificities of psoriasis, could be used to define a population where interception can take place, Dr. Schett added. Although it’s not always clinically recognized, the combination of pain and structural lesions can be an indicator for developing PsA.

One prospective study he and his colleagues conducted in 114 psoriasis patients cited structural entheseal lesions and low cortical volumetric bone mineral density as risk factors in developing PsA. Keeping these factors in mind, Dr. Schett expects to see more studies in biointervention in these populations, “with the idea to prevent the onset of PsA and also decrease pain and subcutaneous inflammation.”

Researchers are currently working to identify those high-risk patients to include in an interventional trial, Dr. Ritchlin said.

That said, there’s been a great deal of “clinical trial angst” among investigators, Dr. Ritchlin noted. Outcomes in clinical trials for a wide range of biologic agents have not demonstrated significant advances in outcomes, compared with initial studies with anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) agents 20 years ago.

Combination biologics

One approach that’s generated some interest is the use of combination biologics medications. Sequential inhibition of cytokines such as interleukin-17A and TNF-alpha is of interest given their central contribution in joint inflammation and damage. “The challenge here of course is toxicity,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Trials that combined blockade of IL-1 and TNF-alpha in a RA trial years ago resulted in significant adverse events without improving outcomes.

Comparatively, a recent study in The Lancet Rheumatology reported success in using the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) to reduce PsA symptoms. Tested on patients in the FUTURE 2 trial, investigators demonstrated that secukinumab in 300- and 150-mg doses safely reduced PsA signs and symptoms over a period of 5 years. Secukinumab also outperformed the TNF-alpha inhibitor adalimumab in 853 PsA patients in the 52-week, randomized, head-to-head, phase 3b EXCEED study, which was recently reported in The Lancet. Articular outcomes were similar between the two therapies, yet the secukinumab group did markedly better in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores, compared with the adalimumab group.

Based on these findings, “I suspect that studies examining the efficacy of combination biologics for treatment of PsA will surface in the near future,” Dr. Ritchlin said.

Yet another approach encompasses the spirit of personalized medicine. Clinicians often treat PsA patients empirically because they lack biomarkers that indicate which drug may be most effective for an individual patient, Dr. Ritchlin said. However, the technologies for investigating specific cell subsets in both the blood and tissues have advanced greatly over the last decade. “I am confident that a more precision medicine–based approach to the diagnosis and treatment of PsA is on the near horizon.”

Diet as an intervention

Other research has looked at the strong link between metabolic abnormalities and psoriasis and PsA. Some diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, show promise in improving the metabolic profile of these patients, making it a candidate as a potential intervention to reduce PsA risk. Another strategy would be to focus on limiting calories and promoting weight reduction.

One study in the British Journal of Dermatology looked at the associations between PsA and smoking, alcohol, and body mass index, identifying obesity as an important risk factor. Analyzing more than 90,000 psoriasis cases from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink between 1998 and 2014, researchers identified 1,409 PsA diagnoses. Among this cohort, researchers found an association between PsA and increased body mass index and moderate drinking. This finding underscores the need to support weight-reduction programs to reduce risk, Dr. Eder and Alexis Ogdie, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in a related editorial.

While observational studies such as this one provide further guidance for interventional trials, confounders can affect results. “Patients who lost weight could have made a positive lifestyle change (e.g., a dietary change) that was associated with the decreased risk for PsA rather than weight loss specifically, or they could have lost weight for unhealthy reasons,” Dr. Eder and Dr. Ogdie explained. Future research could address whether weight loss or other interventional factors may reduce PsA progression.

To make this work, “we would need to select patients that would benefit from diet. Secondly, we’d need to identify what kind of diet would be good for preventing PsA. And we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder further elaborated.

As with any prevention trial, the challenge is to follow patients over a long period of time, making sure they comply with the restrictions of the prescribed diet, Dr. Eder noted. “I do think it’s a really exciting type of intervention because it’s something that people are very interested in. There’s little risk of side effects, and it’s not very expensive.”

In other research on weight-loss methods, an observational study from Denmark found that bariatric surgery, especially gastric bypass, reduced the risk of developing PsA. This suggests that weight reduction by itself is important, “although we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder said.

A risk model for PsA

Dr. Eder and colleagues have been working on an algorithm that will incorporate clinical information (for example, the presence of nail lesions and the severity of psoriasis) to provide an estimated risk of developing PsA over the next 5 years. Subsequently, this information could be used to identify high-risk psoriasis patients as candidates for a prevention trial.

Other groups are looking at laboratory or imaging biomarkers to help develop PsA prediction models, she said. “Once we have these tools, we can move to next steps of prevention trials. What kinds of interventions should we apply? Are we talking biologic medications or other lifestyle interventions like diet? We are still at the early stages. However, with an improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms and risk factors we are expected to see prevention trials for PsA in the future.”

About one-third of all patients with psoriasis will develop psoriatic arthritis (PsA), a condition that comes with a host of vague symptoms and no definitive blood test for diagnosis. Prevention trials could help to identify higher-risk groups for PsA, with a goal to catch disease early and improve outcomes. The challenge is finding enough participants in a disease that lacks a clear clinical profile, then tracking them for long periods of time to generate any significant data.

Researchers have been taking several approaches to improve outcomes in PsA, Christopher Ritchlin, MD, MPH, chief of the allergy/immunology and rheumatology division at the University of Rochester (N.Y.), said in an interview. “We are in the process of identifying biomarkers and imaging findings that characterize psoriasis patients at high risk to develop PsA.”

The next step would be to design an interventional trial to treat high-risk patients before they develop musculoskeletal inflammation, with a goal to delay onset, attenuate severity, or completely prevent arthritis. The issue now is “we don’t know which agents would be most effective in this prevention effort,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Biologics that target specific pathways significant in PsA pathogenesis are an appealing prospect. However, “it may be that alternative therapies such as methotrexate or ultraviolet A radiation therapy, for example, may help arrest the development of joint inflammation.”

Underdiagnosis impedes research

Several factors may undermine this important research.

For one, psoriasis patients are often unaware that they have PsA. “Many times they are diagnosed incorrectly by nonspecialists. As a consequence, they do not get access to appropriate medications,” said Lihi Eder, MD, PhD, staff rheumatologist and director of the psoriatic arthritis research program at the University of Toronto’s Women’s College Research Institute.

The condition also lacks a good diagnostic tool, Dr. Eder said. There’s no blood test that identifies this condition in the same manner as RA and lupus, for example. For these conditions, a general practitioner such as a family physician may conduct a blood test, and if positive, refer them to a rheumatologist. Such a system doesn’t exist for PsA. “Instead, nonspecialists are ordering tests and when they’re negative, they assume wrongly that these patients don’t have a rheumatic condition,” she explained.

Many clinicians aren’t that well versed in PsA, although dermatology has taken steps to become better educated. As a result, more dermatologists are referring patients to rheumatologists for PsA. Despite this small step forward, the heterogeneous clinical presentation of this condition makes diagnosis especially difficult. Unlike RA, which presents with inflammation in the joints, PsA can present as back or joint pain, “which makes our life as rheumatologists much more complex,” Dr. Eder said.

Defining a risk group

Most experts agree that the presence of psoriasis isn’t sufficient to conduct a prevention trial. Ideally, the goal of a prevention study would be to identify a critical subgroup of psoriasis patients at high risk of developing PsA.

However, this presents a challenging task, Dr. Eder said. Psoriasis is a risk factor for PsA, but most patients with psoriasis won’t actually develop it. Given that there’s an incidence rate of 2.7% a year, “you would need to recruit many hundreds of psoriasis patients and follow them for a long period of time until you have enough events.”

Moving forward with prevention studies calls for a better definition of the PsA risk group, according to Georg Schett, MD, chair of internal medicine in the department of internal medicine, rheumatology, and immunology at Friedrich‐Alexander University, Erlangen, Germany. “That’s very important, because you need to define such a group to make a prevention trial feasible. The whole benefit of such an approach is to catch the disease early, to say that psoriasis is a biomarker that’s linked to psoriatic arthritis.”

Indicators of risk other than psoriasis, such as pain, inflammation seen in ultrasound or MRI, and other specificities of psoriasis, could be used to define a population where interception can take place, Dr. Schett added. Although it’s not always clinically recognized, the combination of pain and structural lesions can be an indicator for developing PsA.

One prospective study he and his colleagues conducted in 114 psoriasis patients cited structural entheseal lesions and low cortical volumetric bone mineral density as risk factors in developing PsA. Keeping these factors in mind, Dr. Schett expects to see more studies in biointervention in these populations, “with the idea to prevent the onset of PsA and also decrease pain and subcutaneous inflammation.”

Researchers are currently working to identify those high-risk patients to include in an interventional trial, Dr. Ritchlin said.

That said, there’s been a great deal of “clinical trial angst” among investigators, Dr. Ritchlin noted. Outcomes in clinical trials for a wide range of biologic agents have not demonstrated significant advances in outcomes, compared with initial studies with anti–tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNF-alpha) agents 20 years ago.

Combination biologics

One approach that’s generated some interest is the use of combination biologics medications. Sequential inhibition of cytokines such as interleukin-17A and TNF-alpha is of interest given their central contribution in joint inflammation and damage. “The challenge here of course is toxicity,” Dr. Ritchlin said. Trials that combined blockade of IL-1 and TNF-alpha in a RA trial years ago resulted in significant adverse events without improving outcomes.

Comparatively, a recent study in The Lancet Rheumatology reported success in using the IL-17A inhibitor secukinumab (Cosentyx) to reduce PsA symptoms. Tested on patients in the FUTURE 2 trial, investigators demonstrated that secukinumab in 300- and 150-mg doses safely reduced PsA signs and symptoms over a period of 5 years. Secukinumab also outperformed the TNF-alpha inhibitor adalimumab in 853 PsA patients in the 52-week, randomized, head-to-head, phase 3b EXCEED study, which was recently reported in The Lancet. Articular outcomes were similar between the two therapies, yet the secukinumab group did markedly better in Psoriasis Area and Severity Index scores, compared with the adalimumab group.

Based on these findings, “I suspect that studies examining the efficacy of combination biologics for treatment of PsA will surface in the near future,” Dr. Ritchlin said.

Yet another approach encompasses the spirit of personalized medicine. Clinicians often treat PsA patients empirically because they lack biomarkers that indicate which drug may be most effective for an individual patient, Dr. Ritchlin said. However, the technologies for investigating specific cell subsets in both the blood and tissues have advanced greatly over the last decade. “I am confident that a more precision medicine–based approach to the diagnosis and treatment of PsA is on the near horizon.”

Diet as an intervention

Other research has looked at the strong link between metabolic abnormalities and psoriasis and PsA. Some diets, such as the Mediterranean diet, show promise in improving the metabolic profile of these patients, making it a candidate as a potential intervention to reduce PsA risk. Another strategy would be to focus on limiting calories and promoting weight reduction.

One study in the British Journal of Dermatology looked at the associations between PsA and smoking, alcohol, and body mass index, identifying obesity as an important risk factor. Analyzing more than 90,000 psoriasis cases from the U.K. Clinical Practice Research Datalink between 1998 and 2014, researchers identified 1,409 PsA diagnoses. Among this cohort, researchers found an association between PsA and increased body mass index and moderate drinking. This finding underscores the need to support weight-reduction programs to reduce risk, Dr. Eder and Alexis Ogdie, MD, of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, wrote in a related editorial.

While observational studies such as this one provide further guidance for interventional trials, confounders can affect results. “Patients who lost weight could have made a positive lifestyle change (e.g., a dietary change) that was associated with the decreased risk for PsA rather than weight loss specifically, or they could have lost weight for unhealthy reasons,” Dr. Eder and Dr. Ogdie explained. Future research could address whether weight loss or other interventional factors may reduce PsA progression.

To make this work, “we would need to select patients that would benefit from diet. Secondly, we’d need to identify what kind of diet would be good for preventing PsA. And we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder further elaborated.

As with any prevention trial, the challenge is to follow patients over a long period of time, making sure they comply with the restrictions of the prescribed diet, Dr. Eder noted. “I do think it’s a really exciting type of intervention because it’s something that people are very interested in. There’s little risk of side effects, and it’s not very expensive.”

In other research on weight-loss methods, an observational study from Denmark found that bariatric surgery, especially gastric bypass, reduced the risk of developing PsA. This suggests that weight reduction by itself is important, “although we don’t know that yet,” Dr. Eder said.

A risk model for PsA

Dr. Eder and colleagues have been working on an algorithm that will incorporate clinical information (for example, the presence of nail lesions and the severity of psoriasis) to provide an estimated risk of developing PsA over the next 5 years. Subsequently, this information could be used to identify high-risk psoriasis patients as candidates for a prevention trial.

Other groups are looking at laboratory or imaging biomarkers to help develop PsA prediction models, she said. “Once we have these tools, we can move to next steps of prevention trials. What kinds of interventions should we apply? Are we talking biologic medications or other lifestyle interventions like diet? We are still at the early stages. However, with an improved understanding of the underlying mechanisms and risk factors we are expected to see prevention trials for PsA in the future.”

Melanoma experts say ‘no’ to routine gene profile testing

“The currently published evidence is insufficient to establish that routine use of GEP testing provides additional clinical value for melanoma staging and prognostication beyond available clinicopathologic variables,” they argued.

Patients must be protected “from potentially inaccurate testing that may provide a false sense of security or perceived increased risk” that could lead to the wrong decisions, they said in a consensus statement from the United States’ national Melanoma Prevention Working Group. The statement was published on July 29 in JAMA Dermatology.

The GEP test for melanoma that is available in the United States – DecisionDx-Melanoma from Castle Biosciences – checks the expression levels of 31 genes reported to be associated with melanoma metastasis and recurrence. It uses quantitative reverse transcriptase and polymerase chain reaction on RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens.

The test stratifies patients as being at low, intermediate, or high risk. It is marketed as a guide to whether to perform sentinel lymph node biopsies (SLNB) on patients age 55 years or older with tumors less than 2 mm deep and to decide what levels of follow-up, imaging, and adjuvant treatment are appropriate for tumors at least 0.3 mm deep.

Medicare reimburses at $7,193 per test for SLNB-eligible patients.

However, this test is not endorsed by the American Academy of Dermatology or National Comprehensive Cancer Network outside of studies because the evidence of benefit is not strong enough, the consensus authors noted.

Even so, use of the test is growing, with up to 10% of cutaneous melanomas now being tested in the United States.

Company welcomes “further discussions”

“To date, thousands of clinicians – over 4,200 US clinicians in the last 12 months – have utilized our GEP test for cutaneous melanoma in their patients after reviewing our clinical data and determining that our test provides clinically actionable information that complements current melanoma staging,” said Castle Biosciences Vice President of Research and Development Bob Cook, PhD, when asked for comment.

Citing company-funded studies, he said that “the strength of the existing evidence in support of these claims has undergone rigorous evaluation to obtain Medicare reimbursement.”

“We believe that the application of the test to help guide [the] decision to pursue SLNB has the potential to realize significant cost savings by reducing unnecessary SLNB procedures, particularly in the T1 population.”

Asked for a reaction to the consensus statement, Dr. Cook said in an interview: “We recently launched two prospective studies with multiple centers nationwide that will involve thousands of patients and provide additional data relating our tests to patient outcomes. ... We welcome further discussions to promote collaborative efforts with centers that are part of the [Melanoma Prevention Working Group] to improve patient outcomes.”

Cart before the horse

Medicare, although it reimburses the test, has its doubts. Due to the “low strength of evidence,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in their local coverage determination that continued reimbursement depends on demonstration of 95% or greater distant-metastasis–free survival and melanoma-specific survival at 3 years “in patients directed to no SLNB by the test compared to standard of care, and ... evidence of higher SLNB positivity in patients selected for this procedure by the test compared to standard of care.”

The statement hints at the Achilles’ heel of GEP in melanoma – that is, the lack of evidence that test results improve outcomes. This was the main concern of the consensus statement; the cart is before the horse.

One of the consensus authors, David Polsky, MD, PhD, professor of dermatologic oncology at New York University, New York City, said that “most of the data for this test come from retrospectively collected patient groups.” The prospective studies have been generally small, with no comparator group. “While they have shown some promise in intermediate thickness melanoma, they have not yet demonstrated utility for thin, stage I melanomas.”

First, do no harm

A new meta-analysis of over 800 patients with cutaneous melanoma tested by DecisionDx-Melanoma, published in JAMA Dermatology alongside the consensus statement, shows how the tests perform.

Among patients with a recurrence, DecisionDx-Melanoma correctly classified 82% with stage II disease but only 29% with stage I disease as high risk. Among those without recurrence, the test correctly classified 90% of stage I patients but only 44% with stage II disease as low risk.

Similar results were seen with the melanoma GEP test available in Europe, MelaGenix (NeraCare GmbH). This test was developed from a panel that was narrowed to seven protective genes and one high-risk gene using a training cohort of 125 cutaneous melanomas.

“The prognostic ability of GEP tests ... appeared to be poor at correctly identifying recurrence in patients with stage I disease, suggesting limited potential for clinical utility in these patients,” commented the meta-analysis authors, led by Michael Marchetti, MD, an assistant professor of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City.

“Unknown are the harms associated with a false-positive result, which were 10-fold more frequent than true-positive results in patients with stage I disease,” they pointed out.

“Further research is needed to define the incremental improvement in risk predictions provided by the test beyond ... all other known clinicopathologic factors,” which include patient sex, age, tumor location and thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, microsatellites, and other factors proven to be linked to outcomes, they said.

Studies so far suggesting benefit have incorporated a few of those factors, but not all of them. For now, “it is not clear which patients should be tested or how to act on the results,” Dr. Marchetti and colleagues concluded.

Breast cancer standard of proof

Larger, prospective studies are needed to address whether GEP testing can replace SLNB to predict relapse “and [can identify] patients who could be spared surveillance imaging and/or benefit from adjuvant therapy,” wrote the consensus authors. Follow-up also needs to be long enough to detect delayed recurrence of thin melanomas, they added.

With more research, there is reason to hope that gene expression profiling will help in melanoma; it’s already standard of care in breast cancer, they pointed out.

On the hope front, one cohort study evaluated whether DecisionDx-Melanoma could identify patients at low risk for positive lymph nodes in T1/T2 disease who were eligible for biopsy. Only 1.6% of subjects who were aged 65 years or older and identified by the test as low risk had a positive node.

“This is a promising direction of investigation ... in a narrow, defined population,” noted authors led by Carrie Kovarik, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in an opinion piece last spring.

But still, until there’s “clear evidence that [DecisionDx-Melanoma] results affect patient outcomes, we should not use it to influence care decisions in patients with thin” melanomas. Dermatology “should expect the same standards” of proof as breast cancer, they wrote.

What to do right now?

Despite the marketing, “think twice before ordering GEP tests for” T1a melanomas is the message in an editorial that accompanies the consensus statement. The 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates are 99% and 98%, respectively. GEP tests are unlikely to change these estimates significantly. In fact, the new meta-analysis indicates “that there may be an approximately 12% misassignment rate in this population,” wrote editorialists Warren Chan, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston and Hensin Tsao, MD, PhD, director of the melanoma genetics program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“Even if you use GEP testing and discover a low-risk class assignment for a 2 mm thick melanoma, avoid the urge to bypass the sentinel lymph node discussion. ... Nodal sampling, for good reasons, remains part of all major guidelines and determines eligibility for adjuvant treatments. ... Many of us engaged in genomics research believe that accurate [melanoma] GEP will be developed in time, but better tools and greater tenacity are needed,” they wrote.

There was no industry funding for the consensus statement and meta-analysis. Authors on the consensus statement reported numerous ties to pharmaceutical and other companies, as listed in the paper.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“The currently published evidence is insufficient to establish that routine use of GEP testing provides additional clinical value for melanoma staging and prognostication beyond available clinicopathologic variables,” they argued.

Patients must be protected “from potentially inaccurate testing that may provide a false sense of security or perceived increased risk” that could lead to the wrong decisions, they said in a consensus statement from the United States’ national Melanoma Prevention Working Group. The statement was published on July 29 in JAMA Dermatology.

The GEP test for melanoma that is available in the United States – DecisionDx-Melanoma from Castle Biosciences – checks the expression levels of 31 genes reported to be associated with melanoma metastasis and recurrence. It uses quantitative reverse transcriptase and polymerase chain reaction on RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens.

The test stratifies patients as being at low, intermediate, or high risk. It is marketed as a guide to whether to perform sentinel lymph node biopsies (SLNB) on patients age 55 years or older with tumors less than 2 mm deep and to decide what levels of follow-up, imaging, and adjuvant treatment are appropriate for tumors at least 0.3 mm deep.

Medicare reimburses at $7,193 per test for SLNB-eligible patients.

However, this test is not endorsed by the American Academy of Dermatology or National Comprehensive Cancer Network outside of studies because the evidence of benefit is not strong enough, the consensus authors noted.

Even so, use of the test is growing, with up to 10% of cutaneous melanomas now being tested in the United States.

Company welcomes “further discussions”

“To date, thousands of clinicians – over 4,200 US clinicians in the last 12 months – have utilized our GEP test for cutaneous melanoma in their patients after reviewing our clinical data and determining that our test provides clinically actionable information that complements current melanoma staging,” said Castle Biosciences Vice President of Research and Development Bob Cook, PhD, when asked for comment.

Citing company-funded studies, he said that “the strength of the existing evidence in support of these claims has undergone rigorous evaluation to obtain Medicare reimbursement.”

“We believe that the application of the test to help guide [the] decision to pursue SLNB has the potential to realize significant cost savings by reducing unnecessary SLNB procedures, particularly in the T1 population.”

Asked for a reaction to the consensus statement, Dr. Cook said in an interview: “We recently launched two prospective studies with multiple centers nationwide that will involve thousands of patients and provide additional data relating our tests to patient outcomes. ... We welcome further discussions to promote collaborative efforts with centers that are part of the [Melanoma Prevention Working Group] to improve patient outcomes.”

Cart before the horse

Medicare, although it reimburses the test, has its doubts. Due to the “low strength of evidence,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in their local coverage determination that continued reimbursement depends on demonstration of 95% or greater distant-metastasis–free survival and melanoma-specific survival at 3 years “in patients directed to no SLNB by the test compared to standard of care, and ... evidence of higher SLNB positivity in patients selected for this procedure by the test compared to standard of care.”

The statement hints at the Achilles’ heel of GEP in melanoma – that is, the lack of evidence that test results improve outcomes. This was the main concern of the consensus statement; the cart is before the horse.

One of the consensus authors, David Polsky, MD, PhD, professor of dermatologic oncology at New York University, New York City, said that “most of the data for this test come from retrospectively collected patient groups.” The prospective studies have been generally small, with no comparator group. “While they have shown some promise in intermediate thickness melanoma, they have not yet demonstrated utility for thin, stage I melanomas.”

First, do no harm

A new meta-analysis of over 800 patients with cutaneous melanoma tested by DecisionDx-Melanoma, published in JAMA Dermatology alongside the consensus statement, shows how the tests perform.

Among patients with a recurrence, DecisionDx-Melanoma correctly classified 82% with stage II disease but only 29% with stage I disease as high risk. Among those without recurrence, the test correctly classified 90% of stage I patients but only 44% with stage II disease as low risk.

Similar results were seen with the melanoma GEP test available in Europe, MelaGenix (NeraCare GmbH). This test was developed from a panel that was narrowed to seven protective genes and one high-risk gene using a training cohort of 125 cutaneous melanomas.

“The prognostic ability of GEP tests ... appeared to be poor at correctly identifying recurrence in patients with stage I disease, suggesting limited potential for clinical utility in these patients,” commented the meta-analysis authors, led by Michael Marchetti, MD, an assistant professor of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City.

“Unknown are the harms associated with a false-positive result, which were 10-fold more frequent than true-positive results in patients with stage I disease,” they pointed out.

“Further research is needed to define the incremental improvement in risk predictions provided by the test beyond ... all other known clinicopathologic factors,” which include patient sex, age, tumor location and thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, microsatellites, and other factors proven to be linked to outcomes, they said.

Studies so far suggesting benefit have incorporated a few of those factors, but not all of them. For now, “it is not clear which patients should be tested or how to act on the results,” Dr. Marchetti and colleagues concluded.

Breast cancer standard of proof

Larger, prospective studies are needed to address whether GEP testing can replace SLNB to predict relapse “and [can identify] patients who could be spared surveillance imaging and/or benefit from adjuvant therapy,” wrote the consensus authors. Follow-up also needs to be long enough to detect delayed recurrence of thin melanomas, they added.

With more research, there is reason to hope that gene expression profiling will help in melanoma; it’s already standard of care in breast cancer, they pointed out.

On the hope front, one cohort study evaluated whether DecisionDx-Melanoma could identify patients at low risk for positive lymph nodes in T1/T2 disease who were eligible for biopsy. Only 1.6% of subjects who were aged 65 years or older and identified by the test as low risk had a positive node.

“This is a promising direction of investigation ... in a narrow, defined population,” noted authors led by Carrie Kovarik, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in an opinion piece last spring.

But still, until there’s “clear evidence that [DecisionDx-Melanoma] results affect patient outcomes, we should not use it to influence care decisions in patients with thin” melanomas. Dermatology “should expect the same standards” of proof as breast cancer, they wrote.

What to do right now?

Despite the marketing, “think twice before ordering GEP tests for” T1a melanomas is the message in an editorial that accompanies the consensus statement. The 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates are 99% and 98%, respectively. GEP tests are unlikely to change these estimates significantly. In fact, the new meta-analysis indicates “that there may be an approximately 12% misassignment rate in this population,” wrote editorialists Warren Chan, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston and Hensin Tsao, MD, PhD, director of the melanoma genetics program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“Even if you use GEP testing and discover a low-risk class assignment for a 2 mm thick melanoma, avoid the urge to bypass the sentinel lymph node discussion. ... Nodal sampling, for good reasons, remains part of all major guidelines and determines eligibility for adjuvant treatments. ... Many of us engaged in genomics research believe that accurate [melanoma] GEP will be developed in time, but better tools and greater tenacity are needed,” they wrote.

There was no industry funding for the consensus statement and meta-analysis. Authors on the consensus statement reported numerous ties to pharmaceutical and other companies, as listed in the paper.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

“The currently published evidence is insufficient to establish that routine use of GEP testing provides additional clinical value for melanoma staging and prognostication beyond available clinicopathologic variables,” they argued.

Patients must be protected “from potentially inaccurate testing that may provide a false sense of security or perceived increased risk” that could lead to the wrong decisions, they said in a consensus statement from the United States’ national Melanoma Prevention Working Group. The statement was published on July 29 in JAMA Dermatology.

The GEP test for melanoma that is available in the United States – DecisionDx-Melanoma from Castle Biosciences – checks the expression levels of 31 genes reported to be associated with melanoma metastasis and recurrence. It uses quantitative reverse transcriptase and polymerase chain reaction on RNA from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded biopsy specimens.

The test stratifies patients as being at low, intermediate, or high risk. It is marketed as a guide to whether to perform sentinel lymph node biopsies (SLNB) on patients age 55 years or older with tumors less than 2 mm deep and to decide what levels of follow-up, imaging, and adjuvant treatment are appropriate for tumors at least 0.3 mm deep.

Medicare reimburses at $7,193 per test for SLNB-eligible patients.

However, this test is not endorsed by the American Academy of Dermatology or National Comprehensive Cancer Network outside of studies because the evidence of benefit is not strong enough, the consensus authors noted.

Even so, use of the test is growing, with up to 10% of cutaneous melanomas now being tested in the United States.

Company welcomes “further discussions”

“To date, thousands of clinicians – over 4,200 US clinicians in the last 12 months – have utilized our GEP test for cutaneous melanoma in their patients after reviewing our clinical data and determining that our test provides clinically actionable information that complements current melanoma staging,” said Castle Biosciences Vice President of Research and Development Bob Cook, PhD, when asked for comment.

Citing company-funded studies, he said that “the strength of the existing evidence in support of these claims has undergone rigorous evaluation to obtain Medicare reimbursement.”

“We believe that the application of the test to help guide [the] decision to pursue SLNB has the potential to realize significant cost savings by reducing unnecessary SLNB procedures, particularly in the T1 population.”

Asked for a reaction to the consensus statement, Dr. Cook said in an interview: “We recently launched two prospective studies with multiple centers nationwide that will involve thousands of patients and provide additional data relating our tests to patient outcomes. ... We welcome further discussions to promote collaborative efforts with centers that are part of the [Melanoma Prevention Working Group] to improve patient outcomes.”

Cart before the horse

Medicare, although it reimburses the test, has its doubts. Due to the “low strength of evidence,” the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services said in their local coverage determination that continued reimbursement depends on demonstration of 95% or greater distant-metastasis–free survival and melanoma-specific survival at 3 years “in patients directed to no SLNB by the test compared to standard of care, and ... evidence of higher SLNB positivity in patients selected for this procedure by the test compared to standard of care.”

The statement hints at the Achilles’ heel of GEP in melanoma – that is, the lack of evidence that test results improve outcomes. This was the main concern of the consensus statement; the cart is before the horse.

One of the consensus authors, David Polsky, MD, PhD, professor of dermatologic oncology at New York University, New York City, said that “most of the data for this test come from retrospectively collected patient groups.” The prospective studies have been generally small, with no comparator group. “While they have shown some promise in intermediate thickness melanoma, they have not yet demonstrated utility for thin, stage I melanomas.”

First, do no harm

A new meta-analysis of over 800 patients with cutaneous melanoma tested by DecisionDx-Melanoma, published in JAMA Dermatology alongside the consensus statement, shows how the tests perform.

Among patients with a recurrence, DecisionDx-Melanoma correctly classified 82% with stage II disease but only 29% with stage I disease as high risk. Among those without recurrence, the test correctly classified 90% of stage I patients but only 44% with stage II disease as low risk.

Similar results were seen with the melanoma GEP test available in Europe, MelaGenix (NeraCare GmbH). This test was developed from a panel that was narrowed to seven protective genes and one high-risk gene using a training cohort of 125 cutaneous melanomas.

“The prognostic ability of GEP tests ... appeared to be poor at correctly identifying recurrence in patients with stage I disease, suggesting limited potential for clinical utility in these patients,” commented the meta-analysis authors, led by Michael Marchetti, MD, an assistant professor of dermatology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City.

“Unknown are the harms associated with a false-positive result, which were 10-fold more frequent than true-positive results in patients with stage I disease,” they pointed out.

“Further research is needed to define the incremental improvement in risk predictions provided by the test beyond ... all other known clinicopathologic factors,” which include patient sex, age, tumor location and thickness, ulceration, mitotic rate, lymphovascular invasion, microsatellites, and other factors proven to be linked to outcomes, they said.

Studies so far suggesting benefit have incorporated a few of those factors, but not all of them. For now, “it is not clear which patients should be tested or how to act on the results,” Dr. Marchetti and colleagues concluded.

Breast cancer standard of proof

Larger, prospective studies are needed to address whether GEP testing can replace SLNB to predict relapse “and [can identify] patients who could be spared surveillance imaging and/or benefit from adjuvant therapy,” wrote the consensus authors. Follow-up also needs to be long enough to detect delayed recurrence of thin melanomas, they added.

With more research, there is reason to hope that gene expression profiling will help in melanoma; it’s already standard of care in breast cancer, they pointed out.

On the hope front, one cohort study evaluated whether DecisionDx-Melanoma could identify patients at low risk for positive lymph nodes in T1/T2 disease who were eligible for biopsy. Only 1.6% of subjects who were aged 65 years or older and identified by the test as low risk had a positive node.

“This is a promising direction of investigation ... in a narrow, defined population,” noted authors led by Carrie Kovarik, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, in an opinion piece last spring.

But still, until there’s “clear evidence that [DecisionDx-Melanoma] results affect patient outcomes, we should not use it to influence care decisions in patients with thin” melanomas. Dermatology “should expect the same standards” of proof as breast cancer, they wrote.

What to do right now?

Despite the marketing, “think twice before ordering GEP tests for” T1a melanomas is the message in an editorial that accompanies the consensus statement. The 5- and 10-year melanoma-specific survival rates are 99% and 98%, respectively. GEP tests are unlikely to change these estimates significantly. In fact, the new meta-analysis indicates “that there may be an approximately 12% misassignment rate in this population,” wrote editorialists Warren Chan, of Baylor College of Medicine, Houston and Hensin Tsao, MD, PhD, director of the melanoma genetics program at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston.

“Even if you use GEP testing and discover a low-risk class assignment for a 2 mm thick melanoma, avoid the urge to bypass the sentinel lymph node discussion. ... Nodal sampling, for good reasons, remains part of all major guidelines and determines eligibility for adjuvant treatments. ... Many of us engaged in genomics research believe that accurate [melanoma] GEP will be developed in time, but better tools and greater tenacity are needed,” they wrote.

There was no industry funding for the consensus statement and meta-analysis. Authors on the consensus statement reported numerous ties to pharmaceutical and other companies, as listed in the paper.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA approves topical antiandrogen for acne

Clascoterone is a topical androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for treatment of acne vulgaris in patients aged 12 years and older, according to the labeling from manufacturer Cassiopea. Clascoterone, which will be marketed as Winlevi, targets the androgen hormones that contribute to acne by inhibiting serum production and inflammation, according to a company press release.

“Although clascoterone’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, laboratory studies suggest clascoterone competes with androgens, specifically dihydrotestosterone, for binding to the androgen receptors within the sebaceous gland and hair follicles,” according to the release.

Approval was based in part on a pair of phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 12-week, randomized trials including 1,440 patients aged 9 years and older with moderate to severe facial acne. The findings were published in April, in JAMA Dermatology .

Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of clascoterone or a control vehicle; treatment success was defined as having an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), as well as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline, and absolute change in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesion counts at week 12.

At 12 weeks, treatment success rates were 18.4% and 20.3% among those on clascoterone, compared with 9% and 6.5%, respectively, among controls. There were also significant reductions in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions from baseline at 12 weeks, compared with controls.

In the studies, treatment was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to safety in controls. Adverse events thought to be related to clascoterone in the studies (a total of 13) included application-site pain; erythema; oropharyngeal pain; hypersensitivity, dryness, or hypertrichosis at the application site; eye irritation; headache; and hair color changes. “Clascoterone targets androgen receptors at the site of application and is quickly metabolized to an inactive form, thus limiting systemic activity,” the authors of the study wrote.

Clascoterone is expected to be available in the United States in early 2021, according to the manufacturer.

Clascoterone is a topical androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for treatment of acne vulgaris in patients aged 12 years and older, according to the labeling from manufacturer Cassiopea. Clascoterone, which will be marketed as Winlevi, targets the androgen hormones that contribute to acne by inhibiting serum production and inflammation, according to a company press release.

“Although clascoterone’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, laboratory studies suggest clascoterone competes with androgens, specifically dihydrotestosterone, for binding to the androgen receptors within the sebaceous gland and hair follicles,” according to the release.

Approval was based in part on a pair of phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 12-week, randomized trials including 1,440 patients aged 9 years and older with moderate to severe facial acne. The findings were published in April, in JAMA Dermatology .

Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of clascoterone or a control vehicle; treatment success was defined as having an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), as well as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline, and absolute change in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesion counts at week 12.

At 12 weeks, treatment success rates were 18.4% and 20.3% among those on clascoterone, compared with 9% and 6.5%, respectively, among controls. There were also significant reductions in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions from baseline at 12 weeks, compared with controls.

In the studies, treatment was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to safety in controls. Adverse events thought to be related to clascoterone in the studies (a total of 13) included application-site pain; erythema; oropharyngeal pain; hypersensitivity, dryness, or hypertrichosis at the application site; eye irritation; headache; and hair color changes. “Clascoterone targets androgen receptors at the site of application and is quickly metabolized to an inactive form, thus limiting systemic activity,” the authors of the study wrote.

Clascoterone is expected to be available in the United States in early 2021, according to the manufacturer.

Clascoterone is a topical androgen receptor inhibitor indicated for treatment of acne vulgaris in patients aged 12 years and older, according to the labeling from manufacturer Cassiopea. Clascoterone, which will be marketed as Winlevi, targets the androgen hormones that contribute to acne by inhibiting serum production and inflammation, according to a company press release.

“Although clascoterone’s exact mechanism of action is unknown, laboratory studies suggest clascoterone competes with androgens, specifically dihydrotestosterone, for binding to the androgen receptors within the sebaceous gland and hair follicles,” according to the release.

Approval was based in part on a pair of phase 3, double-blind, vehicle-controlled, 12-week, randomized trials including 1,440 patients aged 9 years and older with moderate to severe facial acne. The findings were published in April, in JAMA Dermatology .

Participants were randomized to twice-daily application of clascoterone or a control vehicle; treatment success was defined as having an Investigator’s Global Assessment score of 0 (clear) or 1 (almost clear), as well as at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline, and absolute change in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesion counts at week 12.

At 12 weeks, treatment success rates were 18.4% and 20.3% among those on clascoterone, compared with 9% and 6.5%, respectively, among controls. There were also significant reductions in noninflammatory and inflammatory lesions from baseline at 12 weeks, compared with controls.

In the studies, treatment was well tolerated, with a safety profile similar to safety in controls. Adverse events thought to be related to clascoterone in the studies (a total of 13) included application-site pain; erythema; oropharyngeal pain; hypersensitivity, dryness, or hypertrichosis at the application site; eye irritation; headache; and hair color changes. “Clascoterone targets androgen receptors at the site of application and is quickly metabolized to an inactive form, thus limiting systemic activity,” the authors of the study wrote.

Clascoterone is expected to be available in the United States in early 2021, according to the manufacturer.

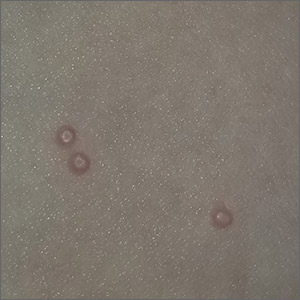

Bumps on the thighs

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

The photograph submitted for the telemedicine visit showed 2 classic umbilicated lesions and 1 dome-shaped papule consistent with molluscum contagiosum. Not all skin conditions can be diagnosed or treated via telehealth, but with a careful history, cooperative patients (and parents in this case), and photos taken on newer cell phones or digital cameras, many conditions can be diagnosed and managed appropriately.

Molluscum contagiosum is caused by the Molluscipox genus poxvirus and Is commonly seen in preschool and school-aged children. It can be passed through direct contact with infected individuals or spread by fomites. (In this case, the child may have picked up the virus by sharing a towel with an infected individual.)

The flesh-colored lesions are umbilicated or popular, and occur in clusters on the trunk, face, and extremities. Typically, the lesions will resolve spontaneously, but it may take several weeks to many months for resolution.

Given this lengthy time for spontaneous resolution, the risk of spreading to family members or other contacts, and the skin’s appearance, many patients choose to treat the lesions. Treatment options include curettage, cryosurgery, and laser. Available topical destructive agents include podophyllotoxin, trichloroacetic acid, benzoyl peroxide, potassium hydroxide, and cantharidin (which is from the blister beetle and often difficult to obtain). There also are naturopathic topical products and immune system modulators, including topical imiquimod. These treatments are commonly used, but are off-label for the treatment of molluscum contagiosum.

The family was counseled that there is debate about the effectiveness of imiquimod for molluscum contagiosum, but that some studies find it to be useful. In this case, the mother chose a prescription for imiquimod cream 5%, to be applied 3 times weekly at bedtime until the lesions resolved. (The cream can be used for up to 16 weeks.) The family was advised that erythema and irritation are expected adverse effects at the application site.

Photo and text courtesy of Daniel Stulberg, MD, FAAFP, Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of New Mexico School of Medicine, Albuquerque.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

Badavanis G, Pasmatzi E, Monastirli A, et al. Topical imiquimod is an effective and safe drug for molluscum contagiosum in children. Acta Dermatovenerol Croat. 2017;25:164-166.

Mapping melasma management

Melasma has such a high recurrence rate that, once the facial hyperpigmentation has been cleared, it’s best that treatment never entirely stops, Amit G. Pandya, MD, said at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

He recommended alternating between a less-intensive maintenance therapy regimen in the winter months and an acute care regimen in the sunnier summer months. But . And that is largely a matter of location.

Location, location, location

Melasma has a distinctive symmetric bilateral distribution: “Melasma likes the central area of the forehead, whereas the lateral areas of the forehead are more involved in lichen planus pigmentosus. Melanoma likes the area above the eyebrow or under the eyebrow. However, it does not go below the superior orbital rim or above the inferior orbital rim,”said Dr. Pandya, a dermatologist at the Palo Alto Medical Foundation in Sunnyvale, Calif., who is also on the faculty at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas.

Melasma is common on the bridge of the nose, but usually not along the nasolabial fold, where hyperpigmentation is much more likely to be due to seborrheic dermatitis or drug-induced hyperpigmentation. Melasma doesn’t affect the tip of the nose; that’s more likely a sign of sarcoidosis or drug-induced hyperpigmentation. Melasma is common on the zygomatic prominence, while acanthosis nigricans favors the concave area below the zygomatic prominence. And melasma stays above the mandible; pigmentation below the mandible is more suggestive of poikiloderma of Civatte. Lentigines are scattered broadly across sun-exposed areas of the face. They also tend to be less symmetrical than melasma, the dermatologist continued.

Acute treatment

Dr. Pandya’s acute treatment algorithm begins with topical 4% hydroquinone in patients who’ve never been on it before. A response to the drug, which blocks the tyrosine-to-melanin pathway, takes 4-6 weeks, with maximum effect not seen until 3-6 months or longer. Bluish-grey ochronosis is a rare side effect at the 4% concentration but becomes more common at higher concentrations or when the drug is used in combination therapy.

“Hydroquinone is a workhorse, the oldest and most effective depigmenting agent,” he said.

If the patient hasn’t responded positively by 3 months, Dr. Pandya moves on to daily use of the triple-drug combination of fluocinolone acetonide 0.01%/hydroquinone 4%/tretinoin 0.05% known as Tri-Luma, a kinder, gentler descendant of the 45-year-old Kligman-Willis compounded formula comprised of 0.1% dexamethasone, 5% hydroquinone, and 0.1% tretinoin.

If Tri-Luma also proves ineffective, Dr. Pandya turns to oral tranexamic acid. This is off-label therapy for the drug, a plasmin inhibitor, which is approved for the treatment of menorrhagia. But oral tranexamic acid is widely used for treatment of melasma in East Asia, and Dr. Pandya and others have evaluated it in placebo-controlled clinical trials. His conclusion is that oral tranexamic acid appears to be safe and effective for treatment of melasma.

“The drug is not approved for melasma, it’s approved for menorrhagia, so every doctor has to decide how much risk they want to take. The evidence suggests 500 mg per day is a good dose,” he said.

The collective clinical trials experience with oral tranexamic acid for melasma shows a side effect profile consisting of mild GI upset, headache, and myalgia. While increased thromboembolic risk is a theoretic concern, it hasn’t been an issue in the published studies, which typically exclude patients with a history of thromboembolic disease from enrollment. Patient satisfaction with the oral agent is high, according to Dr. Pandya.

In one randomized, open-label, 40-patient study, oral tranexamic acid plus a triple-combination cream featuring fluocinolone 0.01%, hydroquinone 2%, and tretinoin 0.05%, applied once a day, was significantly more effective and faster-acting than the topical therapy alone. At 8 weeks, the dual-therapy group averaged an 88% improvement in the Melasma Activity and Severity Index (MASI) scores, compared with 55% with the topical therapy alone (Indian J Dermatol. Sep-Oct 2015;60[5]:520).

Cysteamine 5% cream, which is available over the counter as Cyspera but is pricey, showed promising efficacy in a 40-patient, randomized, double-blind trial (J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 Mar;29[2]:182-9). Dr. Pandya said he’s looking forward to seeing further studies.

Chemical peels can be used, but multiple treatment sessions using a superficial peeling agent are required, and even then “the efficacy is usually not profound,” according to Dr. Pandya. Together with two colleagues he recently published a comprehensive systematic review of 113 published studies of all treatments for melasma in nearly 7,000 patients (Am J Clin Dermatol. 2020 Apr;21(2):173-225).

Newer lasers with various pulse lengths, fluences, wave lengths, and treatment frequency show “some promise,” but there have also been published reports of hypopigmentation and rebound hyperpigmentation. The optimal laser regimen remains elusive, he said.

Maintenance therapy

Dr. Pandya usually switches from hydroquinone to a different topical tyrosinase inhibitor for maintenance therapy, such as kojic acid, arbutin, or azelaic acid, all available OTC in many formulations. Alternatively, he might drop down to 2% hydroquinone for the winter months. Another option is triple-combination cream applied two or three times per week. A topical formulation of tranexamic acid is available, but studies of this agent in patients with melasma have yielded mixed results.

“I don’t think topical tranexamic acid is going to harm the patient, but I don’t think the efficacy is as good as with oral tranexamic acid,” he said.

Slap that melasma in irons

A comprehensive melasma management plan requires year-round frequent daily application of a broad spectrum sunscreen. And since it’s now evident that visible-wavelength light can worsen melasma through mechanisms similar to UVA and UVB, which are long recognized as the major drivers of the hyperpigmentation disorder, serious consideration should be given to the use of a tinted broad-spectrum sunscreen or makeup containing more than 3% iron oxide, which blocks visible light. In contrast, zinc oxide does not, Dr. Pandya noted.

In one influential study, aminolevulinic acid was applied on the arms of 20 patients; two sunscreens were applied on areas where the ALA was applied, and on one area, no sunscreen was applied. The minimal phototoxic dose of visible blue light was doubled with application of a broad-spectrum sunscreen containing titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, and 0.2% iron oxide, compared with no sunscreen, but increased 21-fold using a sunscreen containing titanium dioxide, zinc oxide, and 3.2% iron oxide (Dermatol Surg. 2008 Nov;34[11]:1469-76).